Bridging the Microbial Gap: A Comprehensive Comparison of Cultured and Total Bacterial Diversity Through High-Throughput Sequencing

This article synthesizes current research on the critical disparity between cultured and total bacterial diversity revealed by high-throughput sequencing (HTS).

Bridging the Microbial Gap: A Comprehensive Comparison of Cultured and Total Bacterial Diversity Through High-Throughput Sequencing

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the critical disparity between cultured and total bacterial diversity revealed by high-throughput sequencing (HTS). Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational 'great plate count anomaly,' where standard techniques cultivate less than 1% of microbial diversity. It details methodological advances in both culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches, provides strategies for optimizing microbial cultivation, and validates findings through comparative analyses. The review underscores the necessity of integrating these methods to fully access the microbial dark matter, with significant implications for antibiotic discovery, microbiome research, and clinical diagnostics.

The Great Plate Count Anomaly: Unveiling the Uncultured Microbial Majority

The "great plate count anomaly," a concept underscoring the stark disparity between the number of microbial cells observed under a microscope and those that can form colonies on laboratory media, has long haunted microbiologists [1]. This disparity is often encapsulated in the "1% culturability paradigm," a rule-of-thumb stating that only about 1% of microbes from natural environments can be cultured under standard laboratory conditions. However, the precise definition and universal applicability of this paradigm are subjects of ongoing debate and refinement within the scientific community [2]. Advances in high-throughput sequencing (HTS) now provide the tools to quantify this gap with unprecedented precision. This guide objectively compares cultured and total bacterial diversity by synthesizing recent HTS-driven research, providing experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform the work of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Comparison of Cultured vs. Total Diversity

The following table summarizes findings from recent studies that have directly compared culture-dependent and culture-independent (HTS) diversity across various environments. The data demonstrates that the "1% paradigm" is a simplification, with actual culturability values varying significantly across ecosystems and experimental approaches.

Table 1: Measured Culturability Across Different Environments Using HTS

| Environment/Sample Type | Total Diversity (HTS-based) | Cultured Diversity | Measured Culturability | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Sediment (South China Sea) | Total OTUs from HTS dataset | OTUs recovered in culture collection | ~6% of total OTUs | Combination of six media cultured more taxa than any single medium. | [3] [4] |

| Wheat Rhizosphere (Arid Soils) | Total OTUs from metagenomic data | OTUs from modified cultivation strategies | 1.86% to 2.52% of total OTUs | Using gellan gums and separate sterilization of phosphate increased culturability vs. standard methods (<1%). | [5] |

| Raccoon Oral/Gut Microbiome | ASVs in original inoculum | ASVs cultivated in experiments | ~57% of original ASVs | Nearly 53% of ASVs in cultivation experiments were not in the original inoculum, suggesting complex dynamics. | [1] |

| Human Fecal Sample | Species identified by CIMS* | Species identified by CEMS | 18% overlap in species | 36.5% of species were identified only by CEMS, highlighting its unique capture of viable taxa. | [6] |

CIMS: Culture-Independent Metagenomic Sequencing | *CEMS: Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing*

Redefining the Paradigm: A Scientific Debate

The "1% paradigm" is not a single, monolithic concept. As argued by Martiny (2019), it can be interpreted in at least three distinct ways: (H1) 1% of cells in a community can be cultivated; (H2) 1% of taxa can be cultivated; or (H3) 1% of cells grow when plated on a standard agar medium [2]. The measured culturability gap is profoundly sensitive to which hypothesis is being tested and how a "taxon" is defined.

- Interpreting the Data: Studies like the one on marine sediment [3] that report ~6% culturability of OTUs are testing a version of H2. In contrast, the high (57%) recovery of ASVs from a mammalian microbiome [1] may reflect a different hypothesis or the focused nature of host-associated communities.

- The "Abundant Biosphere": A key insight is that the most abundant microbial lineages in an environment are often the ones with cultured representatives. The debate often centers on rare taxa and sequence variants, which can inflate total diversity estimates and make the culturability percentage appear smaller [2].

- The Prochlorococcus Example: The marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus illustrates this nuance. While there are ~10^27 cells in the ocean, only about 50 diverse isolates exist in culture. These isolates represent most subclades and have revealed core physiology, but genomics shows that key traits and specific genotypes are still missing from culture collections [2].

Experimental Protocols for Bridging the Gap

To accurately measure and overcome the diversity gap, researchers employ sophisticated experimental workflows that integrate both culture-dependent and culture-independent methods.

Key Methodology 1: Comparative Community Analysis

This protocol directly compares the community profile of an environmental sample (via HTS) with the profile of the microorganisms that grow on culture media.

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Collection & Processing: Collect environmental samples (e.g., sediment, soil, feces). For the marine sediment study [3], samples were stored at 4°C, and DNA was extracted directly for HTS.

- High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS):

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial kit (e.g., E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit) to extract total genomic DNA from the sample [3] [7].

- 16S rRNA Gene Amplification: Amplify variable regions (e.g., V3-V4 with primers 515F/806R) for bacterial diversity analysis [3]. For eukaryotic microbes, the 18S rRNA gene or ITS regions may be targeted [7].

- Sequencing: Perform sequencing on a platform such as Illumina HiSeq [3] [6].

- Culture-Dependent Isolation:

- Media Selection: Employ a diverse array of media to maximize taxonomic recovery. The marine sediment study used six different media, including nutrient-rich (e.g., Emerson agar, Zobell 2216E), low-nutrient (e.g., R2A), and defined media (e.g., CDM, MBM) [3] [4].

- Plating and Incubation: Serially dilute the sample, spread plate on the selected media, and incubate under conditions mimicking the natural environment (e.g., 16°C for marine samples) [3].

- Colony Picking and Identification: Pick colonies based on morphology, subculture to purity, and sequence the 16S rRNA gene using Sanger sequencing (primers 27F/1492R) for identification [3] [6].

- Data Analysis:

- Process HTS reads to cluster into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs).

- Compare the list of OTUs/ASVs from the HTS dataset with those identified from the cultured collection to calculate the percentage of cultured diversity.

Key Methodology 2: Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS)

This innovative approach sequences the entire community of microbes that grow on a culture plate, providing a deeper, non-targeted view of the culturable fraction without the bias of colony picking.

Detailed Protocol:

- High-Throughput Culturing: Plate samples on a wide variety of media (e.g., 12 media types, as in the human gut study [6]) and under different conditions (aerobic/anaerobic).

- Biomass Harvesting: After incubation, do not pick individual colonies. Instead, harvest all biomass from the surface of the agar plate using a cell scraper and a saline solution [6].

- Metagenomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Extract total DNA from the pooled biomass and perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing [6].

- Computational Analysis:

- Use tools like MetaPhlAn2 to profile the microbial community structure from the sequencing data.

- Compare the species list from CEMS with that from direct culture-independent metagenomic sequencing (CIMS) of the original sample to identify overlapping and unique species.

- Calculate Growth Rate Index (GRiD) values to predict the optimal medium for specific bacterial growth, guiding future isolation efforts [6].

Experimental Workflows for Measuring the Diversity Gap

Strategic Optimization of Culturing Efficiency

The diversity gap is not an immutable law but a reflection of methodological limitations. Several strategies have proven effective in increasing the recovery of microbes from diverse environments.

Table 2: Strategies for Enhancing Microbial Culturability

| Strategy | Approach | Experimental Evidence | Impact on Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Media Diversity & Composition | Using multiple media types, including low-nutrient and simulated natural environment media. | Using 6 media types isolated more taxa than any single medium; low-nutrient media were particularly effective [3] [4]. | Increases taxonomic breadth by supporting fastidious organisms with unique nutrient requirements. |

| Gelling Agent Substitution | Replacing agar with gellan gums (Gelrite, Phytagel) and separate sterilization of phosphate buffer. | Phytagel yielded highest CFU counts; separate sterilization reduced inhibitory H2O2 formation [5]. | Improves colony formation of H2O2-sensitive and agarase-producing bacteria, increasing CFU counts and diversity. |

| Chemical Simulation | Adding spent culture supernatant or specific growth factors from other microbes. | Spent culture medium from Ca. Bathyarchaeia enabled recovery of novel phyla like Planctomycetota [8]. | Accesses "unculturable" microbes by providing essential metabolites or signaling molecules not in standard media. |

| Inoculum Pre-Treatment | Using physical/chemical treatments (e.g., ethanol, heat) to select for specific sub-populations. | Ethanol treatment selects for spore-formers; antioxidants alleviate oxidative stress [1]. | Reduces competition from fast-growing weeds, allowing isolation of slow-growing or spore-forming taxa. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials critical for experiments designed to compare cultured and total bacterial diversity.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Diversity Gap Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | To extract high-quality genomic DNA from both direct environmental samples and cultured biomass for sequencing. | E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit [3], QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit [6]. |

| 16S rRNA PCR Primers | To amplify conserved microbial genes for taxonomic identification and HTS library preparation. | 515F/806R for HTS [3]; 27F/1492R for Sanger sequencing of isolates [3]. |

| Alternative Gelling Agents | To solidify media with reduced toxicity towards sensitive microorganisms compared to traditional agar. | Gellan gums, Gelrite, Phytagel [5]. |

| Specialized Growth Media | To provide nutrients and conditions that mimic natural environments and support a wider range of microbes. | Oligotrophic media (R2A, 1/10GAM) [3] [6]; Media with spent culture supernatant [8]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | To create an oxygen-free environment for the cultivation of anaerobic microbes, prevalent in gut and sediment samples. | Type B Vinyl Anaerobic Chamber (atmosphere of 95% N2, 5% H2) [6]. |

| PEG-3 oleamide | PEG-3 oleamide, CAS:26027-37-2, MF:C24H47NO4, MW:413.643 | Chemical Reagent |

| Desmethyldiazepam-d5 | Desmethyldiazepam-d5, CAS:65891-80-7, MF:C15H11ClN2O, MW:275.74 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The "1% culturability paradigm" remains a powerful conceptual tool for highlighting the vast unknown of the microbial world, but it is a fluid benchmark. As the data shows, measured culturability can range from under 2% to over 50%, depending on the environment, the definitions used, and, most importantly, the methodological sophistication employed. The integration of HTS with improved culture strategies—such as media diversification, gelling agent substitution, and culture-enriched metagenomics—is systematically illuminating the "microbial dark matter." For researchers in drug discovery, these advanced methods are not merely academic exercises; they are essential pipelines for accessing novel microorganisms, which represent an unparalleled source of unique bioactive compounds and metabolic pathways waiting to be discovered.

The Historical Reliance on Cultured Isolates and Its Limitations

For over a century, the isolation and cultivation of microorganisms on artificial laboratory media has formed the cornerstone of microbiology. This approach has enabled monumental discoveries in pathogenesis, biochemistry, and ecology. However, this traditional perspective has been fundamentally limited by a significant constraint: the overwhelming majority of microorganisms in most environments resist cultivation under standard laboratory conditions [9] [10]. This phenomenon, often called the "great plate count anomaly," has been recognized for decades, with early estimates suggesting that typically less than 1% of microorganisms observable in nature can be cultivated using standard techniques [9]. This limitation has profound implications for understanding true microbial diversity, physiology, and ecological function.

The advent of culture-independent molecular techniques, particularly high-throughput sequencing (HTS), has revolutionized our view of the microbial world. By allowing direct analysis of genetic material from environmental samples, HTS has revealed a staggering diversity of microbial life that had previously been overlooked [9]. This article provides a comparative guide, contextualized within broader thesis research on cultured versus total bacterial diversity, objectively examining the performance of traditional cultivation against modern HTS approaches. We summarize experimental data, detail methodologies, and visualize the workflows and relationships that define this fundamental dichotomy in microbial analysis.

Quantitative Comparison: Cultured vs. Total Bacterial Diversity

The disparity between the diversity captured by culture-based methods and the actual diversity revealed by HTS is quantifiable and striking. The following tables consolidate key experimental findings from diverse environments, highlighting the scope of this gap.

Table 1: Comparison of Microbial Diversity Captured by Different Methods Across Environments

| Environment | Total Diversity (HTS) | Cultured Diversity | Overlap | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Sediment (South China Sea) | 100% of OTUs (Baseline) | 6% of OTUs | Minimal | Combination of media cultured more taxa than any single medium. | [3] |

| Soil | Extremely diverse communities | ~1% of total cells | Very rare | Majority of clone sequences belong to novel clades without cultured representatives. | [10] |

| Human Gut (Culturomics) | 698 species (Metagenomics) | 340 species (Culturomics) | 51 species | A combination of both methods captured significantly more microbial diversity. | [6] |

| High Arctic Lake Sediment | N/A | 155 OTUs from 1,109 isolates | N/A | No single cultivation method was sufficient; multiple approaches were necessary. | [11] |

Table 2: Impact of Medium Composition on Cultivation Efficiency

| Medium Type | Nutrient Profile | Cultivation Efficiency | Isolation Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient-Rich (e.g., 2216E, EM) | High organic carbon/nitrogen | Low diversity, dominated by fast-growing generalists | Selective for specific taxa (e.g., Actinobacteria in marine sediment). | [3] |

| Low-Nutrient (e.g., R2A, MBM) | Dilute nutrients | Higher diversity | Supported growth of more oligotrophic species. | [3] |

| Single-Carbon/Nitrogen Source | Chemically defined | Low number of taxa | Quality of nitrogen strongly influenced types of bacteria isolated. | [3] |

| Combination of Multiple Media | Varied | Highest diversity | Essential for capturing a broader spectrum of cultivable organisms. | [3] [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Diversity Analysis

To objectively compare cultured and total bacterial diversity, researchers employ standardized protocols for both cultivation and molecular analysis. Below are the core methodological workflows cited in the comparative data.

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Sequencing of Total Bacterial Communities

This culture-independent protocol is used to establish the baseline "total" microbial diversity in a sample [3] [12].

- DNA Extraction: Total genomic DNA is directly extracted from the environmental sample (e.g., soil, sediment, feces) using specialized kits (e.g., E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit, ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit).

- PCR Amplification: The 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4) are amplified using universal barcoded primers (e.g., 515F/806R).

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Amplified products are purified, and libraries are prepared for sequencing on high-throughput platforms like the Illumina MiSeq or HiSeq systems.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequences are processed through pipelines (e.g., QIIME, USEARCH) to cluster into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) for taxonomic classification and diversity analysis.

Protocol 2: Multi-Medium Cultivation and Isolation

This culture-dependent protocol is designed to maximize the recovery of diverse bacterial isolates [3] [6] [11].

- Sample Preparation: The sample is homogenized in a sterile diluent (e.g., artificial seawater for marine samples, saline for gut samples) and serially diluted.

- Plating on Diverse Media: Dilutions are spread onto a variety of solid media types (e.g., nutrient-rich like Zobell 2216E, low-nutrient like R2A, and chemically defined media). The media are often prepared with environmental water (e.g., artificial seawater) to mimic natural conditions.

- Incubation: Plates are incubated under conditions reflecting the sample's origin (e.g., temperature, aerobic/anaerobic atmosphere) for periods ranging from days to weeks.

- Colony Picking and Identification: Colonies with distinct morphologies are purified by sub-culturing. Total DNA is extracted from pure cultures, and the 16S rRNA gene is amplified and sequenced using Sanger sequencing (primers 27F/1492R) for taxonomic identification.

Protocol 3: Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS)

A hybrid approach that leverages cultivation but uses HTS for detection, helping to bridge the gap between the two methods [6].

- High-Throughput Culturing: Environmental samples are cultured using numerous conditions (e.g., 12 different media, aerobic/anaerobic).

- Total Colony Harvesting: Instead of picking individual colonies, all biomass from the entire plate is collected by scraping and pooled for each condition.

- Metagenomic Sequencing: DNA is extracted from the pooled biomass and subjected to shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

- Strain-Level Analysis: Sequencing data is analyzed to determine phylogenetic diversity and can be used to calculate growth rate indices (GRiD) to predict optimal media for specific bacteria.

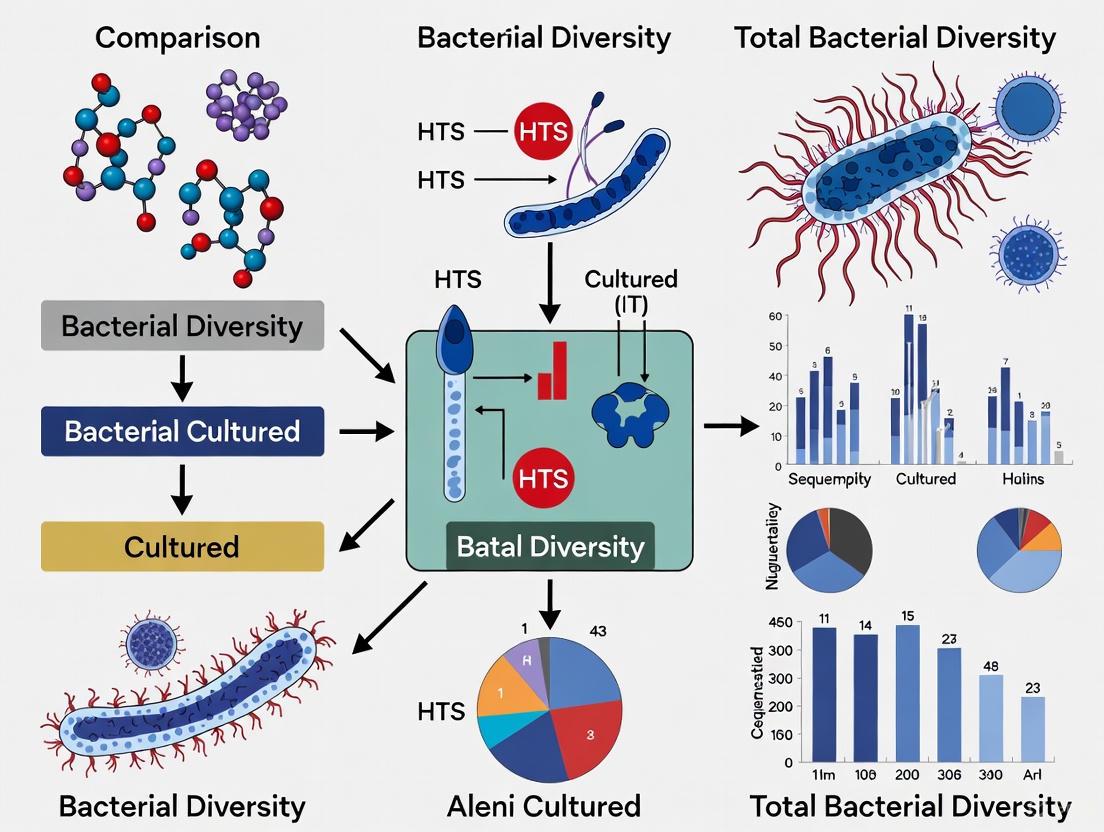

Visualizing the Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the logical and procedural relationships between traditional cultivation, modern sequencing, and the emerging solutions that bridge the two.

The Cultivation Gap and Its Solutions

High-Throughput Culturomics Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Successful comparative studies require specific reagents and tools for both cultivation and molecular analysis. The following table details essential solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cultured vs. Total Diversity Studies

| Category | Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Zobell 2216E, R2A Agar, mGAM | General-purpose and low-nutrient media for isolating diverse environmental bacteria. | Isolation of heterotrophic bacteria from marine sediments [3]. |

| Culture Media | Artificial Seawater (ASW) | Recreates ionic and osmotic conditions for marine and halophilic organisms. | Essential component for cultivating bacteria from marine samples [3]. |

| DNA Extraction | E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit, ZymoBIOMICS DNA Kit | Efficiently lyses tough microbial cells and purifies inhibitor-free DNA from complex samples. | Extraction of high-quality metagenomic DNA from soil and fecal samples for HTS [3] [13]. |

| PCR & Sequencing | 16S rRNA Primers (e.g., 27F/1492R, 515F/806R) | Amplify conserved bacterial gene for taxonomic identification and diversity profiling. | Sanger sequencing of isolates and Illumina-based HTS of communities [3] [13]. |

| Specialized Additives | Rumen Fluid, Sheep Blood | Provides complex growth factors, vitamins, and nutrients to support fastidious organisms. | Supplement in preincubation media for human gut microbiota studies [13]. |

| Automation & AI | CAMII Platform, Machine Learning Algorithms | Automates colony imaging, picking, and uses morphology to predict taxonomy and maximize diversity. | High-throughput generation of personalized gut microbiome biobanks [14]. |

| Sphaerobioside | Sphaerobioside | High-purity Sphaerobioside, a natural isoflavone diglycoside. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| delta-2-Cefodizime | delta-2-Cefodizime|CAS 120533-30-4 | delta-2-Cefodizime (CAS 120533-30-4) is a high-purity reference standard for pharmaceutical research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The historical reliance on cultured isolates, while foundational, provides a necessarily limited view of the microbial world. Quantitative data from diverse environments consistently shows that traditional methods capture only a small fraction of total diversity, often biased toward fast-growing generalists. HTS has irrevocably expanded our understanding, revealing a vast universe of uncultured microbial dark matter. The path forward does not lie in abandoning cultivation, but in integrating it with molecular tools. Advanced strategies—including automated culturomics, multi-medium and in situ cultivation, and leveraging microbial interactions—are actively bridging the gap. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolving toolkit promises more comprehensive biobanks, novel bioactive compound discovery, and a truly holistic understanding of microbial community function in health and disease.

High-Throughput Sequencing as a Lens into Microbial Dark Matter

High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) has fundamentally transformed our capacity to study microbial life, revealing that the vast majority of environmental and host-associated microorganisms cannot be cultivated using standard laboratory techniques—a challenge known as the "microbial dark matter" problem [15]. This guide objectively compares the performance of culture-independent HTS approaches with advanced culture-based techniques for characterizing bacterial diversity. The comparative analysis presented herein, supported by experimental data, demonstrates that while HTS provides a comprehensive census of microbial membership, emerging culturomics methods are essential for functional validation and strain-level resolution. The integration of both paradigms, facilitated by automation and machine learning, represents the most powerful strategy for unlocking the genetic and biochemical potential of unexplored microbiota for drug development and biotechnology.

The Microbial Dark Matter Challenge and the HTS Revolution

Microbial dark matter refers to the immense portion of the microbial world that remains uncultured and uncharacterized. Traditional cultivation approaches fail for an estimated >80% of microorganisms, leaving their genetic diversity, metabolic capabilities, and ecological roles largely unknown [15]. This gap severely limits the discovery of novel bioactive natural products, which are crucial for developing new antibiotics, anticancer agents, and other therapeutics in an era of escalating antimicrobial resistance [15].

High-Throughput Sequencing acts as a powerful lens into this dark matter. By enabling the direct analysis of genetic material from environmental samples, HTS bypasses cultivation requirements. The core applications include:

- 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing: Surveys the structure and membership of microbial communities at a fraction of the cost of whole-genome methods.

- Metagenomic Sequencing: Sequences all the genetic material in a sample, allowing for functional prediction and the discovery of novel biosynthetic gene clusters without the need for isolation [15].

- Single-Cell Genomics: Sequences the genome of an individual microbial cell, providing insights into the metabolic potential of uncultured taxa [15].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the primary pathways for using HTS to investigate microbial dark matter, integrating both culture-independent and culture-dependent paradigms.

Performance Comparison: HTS vs. Advanced Cultivation

The table below summarizes a direct comparison of the diversity captured by HTS and culture-based methods from the same environmental sample, based on a study of marine sediments [3].

Table 1: Recovered Diversity from Marine Sediments: HTS vs. Culture

| Feature | High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) | Culture-Based Methods (6 Media) | Combined Media Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant Taxa (Class Level) | Gammaproteobacteria [3] | Actinobacteria [3] | N/A |

| Percentage of Total OTUs Recovered | 100% (Reference Community) | ~6% [3] | Increased vs. single medium |

| Taxonomic Breadth | Comprehensive view of total community structure. | Limited, strong bias toward fast-growing taxa. | Broader than any single medium. |

| Key Finding | Reveals the true, complex community structure. | Recovers a phylogenetically distinct subset. | No single medium is sufficient; combinations are essential. |

The data reveals a profound disparity. While HTS described a community dominated by Gammaproteobacteria, cultivation efforts on six different media primarily isolated Actinobacteria, recovering only about 6% of the total operational taxonomic units (OTUs) detected by HTS [3]. This clearly demonstrates the severe taxonomic bias inherent in cultivation and underscores the role of HTS as a benchmark for true microbial diversity.

Beyond Census: Advanced Cultivation Bridges the Gap

While HTS provides a census, cultivation is still required for detailed functional and mechanistic studies. Innovative strategies are now being deployed to access microbial dark matter, moving beyond classical methods.

Table 2: Advanced Cultivation Strategies for Microbial Dark Matter

| Strategy | Methodology | Key Achievement |

|---|---|---|

| Co-culture & Microbial Interactions | Culturing microorganisms together to simulate natural symbiotic relationships [15]. | Enables growth of dependent species through cross-feeding and signaling. |

| In Situ Cultivation (Diffusion Chambers) | Placing inoculated chambers back into the native environment to allow chemical exchange [15]. | Accesses microorganisms requiring specific, unknown environmental cues. |

| Targeted Growth Factors | Supplementing media with specific nutrients like zincmethylphyrins or short-chain fatty acids [15]. | Fulfills unique metabolic requirements of fastidious uncultured microbes. |

| Automated High-Throughput Culturomics | Using robotics and machine learning to image, analyze, and pick thousands of colonies [14]. | Dramatically increases isolation throughput and diversity via morphology-based smart picking. |

A landmark study using an automated platform (CAMII) demonstrated the power of machine learning-guided isolation. By selecting colonies based on morphological distinctiveness, this "smart picking" strategy required only 85 colonies to obtain 30 unique species, compared to 410 colonies needed through random picking—a ~5x increase in efficiency [14]. This approach has been used to generate personalized gut microbiome biobanks of 26,997 isolates, representing over 80% of the abundant taxa present [14].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Diversity Studies

For researchers aiming to compare cultured versus total bacterial diversity, the following protocols provide a robust starting point.

Protocol A: HTS for Total Community Diversity

This protocol is adapted from studies analyzing microbial communities in marine sediments and food products [3] [16].

- Sample Collection & Preservation: Collect sample (e.g., sediment, stool, food) in sterile tubes. Immediately freeze at -80°C or use DNA stabilization solutions to preserve in situ microbial composition.

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial kit (e.g., E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit) optimized for hard-to-lyse microorganisms to extract total genomic DNA [3].

- 16S rRNA Gene Amplification: Amplify the hypervariable V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using barcoded universal primers (e.g., 515F/806R) to facilitate multiplexing [3].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Purify PCR products and perform HTS on an Illumina platform (e.g., HiSeq PE250) [3].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process sequences using a pipeline (e.g., QIIME 2, mothur) to quality-filter, cluster sequences into OTUs, and assign taxonomy against reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) [3] [16].

Protocol B: High-Throughput Culturing & Identification

This protocol leverages the insights from media comparison and robotic culturomics studies [3] [14].

- Media Selection & Preparation: Employ a panel of diverse media rather than a single type. This should include:

- Nutrient-Rich Media (e.g., Zobell 2216E, Emerson Agar) for general heterotrophs.

- Low-Nutrient Media (e.g., R2A, Mineral Basal Medium) to avoid overgrowth by fastidious species.

- Supplemented Media with specific growth factors (e.g., porphyrins, blood) or antibiotics to select for specific groups [15] [3] [17].

- Plating & Incubation: Serially dilute the sample and spread plate on the selected media. Incubate under conditions mimicking the sample's native environment (e.g., temperature, anaerobic atmosphere) for extended periods.

- Colony Picking & Identification:

- (Manual) Colony Picking: Pick colonies of varying morphologies and purify by repeated streaking.

- (Robotic) Automated Imaging & Picking: Use a system like CAMII to capture colony morphology and pick isolates based on maximum morphological diversity to maximize taxonomic recovery [14].

- Isolate Identification: Extract DNA from pure cultures and perform Sanger sequencing of the full-length 16S rRNA gene with primers 27F/1492R [3]. For strain-level resolution, perform Whole-Genome Sequencing.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the advanced CAMII platform, which synergizes high-throughput imaging, machine learning, and robotics to systematically link phenotypic and genotypic data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions

Successful research in this field relies on a combination of wet-lab reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from complex samples for HTS. | Kits optimized for soil (e.g., E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit) or stool are essential for lysis of tough cells [3]. |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Amplify taxonomically informative gene regions for community profiling. | Primers 515F/806R for V4 region (Illumina) [3]; 27F/1492R for full-length Sanger sequencing of isolates [3]. |

| Diverse Growth Media | Support the growth of a wide range of fastidious microorganisms. | Use a panel: 2216E (marine), R2A (low nutrient), mGAM (gut), HCB (anaerobes) [3] [14] [17]. |

| Growth Factor Supplements | Meet specific nutritional requirements of uncultured microbes. | Zincmethylphyrins, coproporphyrins, short-chain fatty acids [15]. |

| Bioinformatic Databases | Reference databases for taxonomic classification of HTS data. | SILVA, Greengenes, RDP [16]. |

| Automated Culturomics Platform (CAMII) | Integrates colony imaging, ML-driven picking, and genomics. | Enables phenotype-genotype linking and high-throughput isolation [14]. |

| Fenoterol Impurity A | Fenoterol Impurity A, CAS:391234-95-0, MF:C17H21NO4, MW:303.36 | Chemical Reagent |

| Arginine caprate | Arginine caprate, CAS:2485-55-4, MF:C16H34N4O4, MW:346.47 | Chemical Reagent |

The dichotomy between "culturability" and "total diversity" is being bridged by technological convergence. HTS remains the undisputed champion for mapping the full extent of microbial communities and discovering novel genes. However, advanced culturomics is experiencing a renaissance, proving that a large proportion of microbial dark matter can be cultured with the right strategies. The future lies in the intelligent integration of these approaches: using HTS as a guide to design targeted cultivation strategies and employing machine learning on combined phenotypic and genotypic data to systematically illuminate the functional biology of the microbial universe [15] [14]. This synergistic pipeline is paramount for harnessing microbial dark matter for the next generation of scientific breakthroughs in drug development and biotechnology.

Cultured vs Total Bacterial Diversity through HTS Research

The precise characterization of microbial diversity is fundamental to advancing our understanding of ecosystems, from the human gut to environmental habitats. For decades, the gold standard for microbial study was cultivation, yet it is now widely recognized that most microorganisms in natural environments resist traditional laboratory cultivation [3]. The advent of High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) technologies has revolutionized microbial ecology by enabling culture-independent profiling of entire communities, revealing a vast, previously unseen microbial world.

This guide objectively compares the performance of culture-dependent methods and HTS-based approaches for analyzing bacterial diversity. We focus on three critical environments—marine sediments, the human gut, and soil—synthesizing current research to provide a structured comparison of these methodologies' outputs, strengths, and limitations. The content is framed within the broader thesis that an integrated approach, leveraging both cultured and molecular data, is essential for a comprehensive understanding of microbial community structure, function, and application.

Key Concepts and Definitions

To ensure clarity, the following key terms are defined as they are used in this guide:

- Cultured Diversity: The subset of microorganisms from a sample that can be grown and isolated under specific laboratory conditions on artificial media [3] [18].

- Total (Meta) Diversity: The entire taxonomic breadth of microorganisms in a sample, as revealed primarily through culture-independent HTS of marker genes (e.g., 16S rRNA) or whole genomes [3] [19].

- Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS): A hybrid approach where a sample is first cultured under various conditions, and the total grown biomass is then subjected to metagenomic sequencing, bridging the gap between pure culture and direct sequencing [18].

- Culture-Independent Metagenomic Sequencing (CIMS): The direct sequencing of DNA extracted from an environmental sample without any prior cultivation step [18].

- High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS): Technologies that allow for the massive parallel sequencing of DNA, enabling the analysis of complex mixtures of microorganisms from environmental samples.

Quantitative Comparison of Diversity Recovery

The disparity between the diversity observed through cultivation and the total diversity revealed by HTS is a consistent finding across environments. The following tables summarize quantitative data from comparative studies.

| Environment | Cultured Diversity (Method) | Total Diversity (HTS Method) | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Sediment | 6% of OTUs (Multiple rich & defined media) | 100% (16S HTS) | Combination of media cultured more taxa than any single medium; nutrient-rich media supported fewer taxa. | [3] |

| Human Gut | 36.5% of species (CEMS) | 45.5% of species (CIMS) | Only 18% of species overlapped between CEMS and CIMS; each method captured unique species. | [18] |

| Human Gut | ~400 species (Historical cultivation) | 1,000 - 3,000+ species (Molecular methods) | Early cultural recovery was ~87% of microscopic counts, but HTS revealed far greater species-level diversity. | [19] |

| Soil (Organic) | Higher richness & unique elements (Amplicon Seq) | Baseline diversity (Amplicon Seq) | Organically managed soil showed 40 unique elements vs. 19 in chemically managed soil. | [20] |

Table 2: Impact of Medium Type on Cultured Diversity

The composition of growth media profoundly influences which bacteria are recovered, as demonstrated by studies systematically testing multiple media.

| Medium Type | Nutrient Description | Example Media | Performance & Isolated Taxa | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Nutrient | Mimics oligotrophic conditions | 1/10 GAM, Mineral Basal Medium (MBM) | Worked best for isolating a wider diversity of microbes from marine sediments. | [3] |

| Nutrient-Rich | High in organic carbon/nitrogen | Emerson Agar, Zobell 2216E | Supported growth of relatively few, fast-growing taxa from marine sediments. | [3] |

| Combined Media | Use of multiple media types | 12 different media (Rich, selective, oligotrophic) | Essential for maximizing the diversity of culturable gut microbes; no single medium was sufficient. | [18] |

| Selective Media | Contains inhibitors or specific substrates | MRS-L (for Lactobacillus), MAR (high salt) | Allows for targeted isolation of specific bacterial groups from complex gut communities. | [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To facilitate the replication and critical evaluation of these comparative studies, detailed methodologies from key papers are outlined below.

Protocol 1: Comparative Cultivation from Marine Sediments

This protocol is adapted from the study comparing six different media for isolating microbes from South China Sea sediments [3].

- 1. Sample Collection: Marine sediment samples are collected using a sterile corer, placed in sterile tubes, and transported at 4°C.

- 2. Media Preparation: Six media with varying nutrient composition are prepared:

- Nutrient-Rich: Emerson Agar (EM), Zobell 2216E.

- Moderate-Nutrient: R2A Agar, Modified Yeast Mannitol Agar (MCCM).

- Defined/Low-Nutrient: Modified Chemically Defined Medium (CDM), Mineral Basal Medium (MBM).

- All media are made with artificial seawater (ASW) and autoclaved.

- 3. Sample Processing & Cultivation: Sediment is suspended in sterile ASW and serially diluted. Dilutions are spread onto plates in triplicate and incubated at 16°C until colonies form.

- 4. Colony Picking & Identification: Colonies with distinct morphologies are purified. DNA is extracted from pure cultures, the 16S rRNA gene is amplified via PCR with primers 27F/1492R, and sequenced via Sanger sequencing for identification.

- 5. HTS Analysis (Culture-Independent Control): Total DNA is extracted directly from sediment. The 16S rRNA gene V4 region is amplified with primers 515F/806R and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq platform.

- 6. Data Analysis: Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) from both cultured isolates and HTS data are compared to determine the proportion of cultured diversity.

Protocol 2: Culture-Enriched vs. Culture-Independent Metagenomics

This protocol describes the hybrid CEMS approach used to study the human gut microbiome [18].

- 1. Sample Collection: A fresh fecal sample is collected and rapidly frozen.

- 2. High-Throughput Culturing:

- The sample is cultured on 12 different media types under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

- After incubation, this is followed by Experienced Colony Picking (ECP): researchers select colonies based on morphology for pure culture and Sanger sequencing.

- 3. Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS):

- All colonies from each culture plate are pooled together, creating a "culture-enriched" biomass.

- Total DNA is extracted from this pooled biomass.

- The DNA is subjected to shotgun metagenomic sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq platform.

- 4. Culture-Independent Metagenomic Sequencing (CIMS):

- Total DNA is extracted directly from the original fecal sample.

- This DNA is also subjected to shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

- 5. Bioinformatic & Statistical Analysis:

- Sequencing reads from CEMS and CIMS are quality-controlled and assigned to taxonomic units.

- The species lists from ECP, CEMS, and CIMS are compared using Venn diagrams and statistical tests to evaluate overlap and unique discoveries.

- Growth rates in different media can be inferred from metagenomic data.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of this comparative methodology.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The following table catalogues essential reagents, kits, and materials used in the featured experiments, providing a resource for experimental design.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from complex samples. | E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit [3], HiPure Soil DNA Kits [21], QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit [18]. |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Amplification of specific variable regions for bacterial community profiling via HTS. | 515F/806R (V4 region) [3], 338F/806R (V3-V4) [22], 341F/806R (V3-V4) [21]. |

| Commercial Culture Media | Providing standardized nutrient bases for the cultivation of diverse microbes. | Zobell 2216E (marine) [3], R2A Agar (environmental/oligotrophic) [3], GAM (Gut Microbiota) [18]. |

| PCR Enzyme Kits | Robust amplification of DNA templates for sequencing library preparation or isolate identification. | TransStart Fast Pfu DNA Polymerase [22]. |

| Sequencing Platforms | Performing high-throughput DNA sequencing. | Illumina HiSeq/MiSeq [3] [18] [22], PacBio Sequel (for long-read sequencing) [23]. |

| BAY-6035-R-isomer | BAY-6035-R-isomer, CAS:2283389-29-5, MF:C22H28N4O3, MW:396.49 | Chemical Reagent |

| Bis-PEG2-acid | Bis-PEG2-acid, CAS:51178-68-8, MF:C8H14O6, MW:206.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion and Interpretation of Findings

The collective data from these studies lead to several key conclusions:

- Substantial Diversity is Missed by Cultivation: Across all environments, traditional cultivation methods recover a minority of the total taxonomic diversity present. In marine sediments, only ~6% of OTUs were cultured [3], while in the human gut, a significant proportion of species are only detectable via CIMS [18].

- Media Composition is Critical: The "great plate count anomaly" is not solely due to an inability to culture but also to the use of inappropriate growth conditions. Low-nutrient media and combinations of diverse media types consistently recover a broader spectrum of bacteria than single, nutrient-rich media [3] [18].

- The Hybrid Approach is Powerful: The CEMS method demonstrates that many "uncultured" microbes are, in fact, culturable but are often missed by manual colony picking (ECP). CEMS effectively captures a larger fraction of the community that grows on the plates, providing a more robust link between culture and molecular data [18].

- Functional Insights: HTS allows for functional prediction of microbial communities. For example, in fermented bean curd, functional analysis showed pathways like chemoheterotrophy and fermentation were dominant, with regional variations [22]. Similarly, soil management practices alter microbial community function, with organic farming enriching for decomposers and nutrient cyclers [20].

The comparison between cultured and total bacterial diversity is not a matter of declaring one method superior to the other. Instead, the evidence clearly shows that culture-dependent and HTS-based methods are complementary. Cultivation provides live isolates for functional experimentation, taxonomic description, and biotechnological application [3]. In contrast, HTS delivers a comprehensive census of community structure and genetic potential [19] [18].

The future of microbial ecology lies in integrated strategies. Methods like CEMS that bridge the cultivation gap are essential. Furthermore, leveraging HTS data to design novel cultivation strategies—such as simulating the natural environment in the lab—will be key to unlocking the "microbial dark matter." For researchers in drug development and environmental science, this combined approach is paramount for discovering novel taxa, understanding ecosystem function, and harnessing microbial capabilities.

The comprehensive understanding of bacterial phylogeny and diversity has long been constrained by a fundamental limitation: the overwhelming majority of environmental bacteria resist cultivation under standard laboratory conditions. This discrepancy, often called the "great plate count anomaly," has historically skewed our perception of the bacterial tree of life, as phylogenetic understanding was based primarily on the tiny fraction of organisms that could be cultured [8]. The advent of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies has fundamentally altered this landscape by enabling researchers to bypass the culturing step entirely, sequencing genetic material directly from environmental samples. This paradigm shift has dramatically expanded the known scope of bacterial diversity, revealing a vast array of novel phylogenetic divisions that had previously eluded detection [24] [25]. This guide objectively compares the phylogenetic outcomes derived from traditional culture-dependent methods versus modern culture-independent HTS approaches, providing experimental data and methodologies that underscore a fundamental reorganization of our understanding of bacterial evolution and classification.

Comparative Analysis: Cultured vs. Total Bacterial Diversity

The following tables synthesize quantitative findings from key studies, directly comparing the phylogenetic diversity captured by culturing versus that revealed by HTS.

Table 1: Comparative Diversity in Marine Sediment Samples [3]

| Method | Dominant Taxa Identified | Proportion of Total Diversity Recovered | Key Phylogenetic Groups Missed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-Dependent | Actinobacteria | 6% of total OTUs | >90% of OTUs from the total community |

| Culture-Independent (HTS) | Gammaproteobacteria | 100% of detectable OTUs | - |

Table 2: Discovery of Novel Divisions in a Yellowstone Hot Spring [24]

| Method | Number of Bacterial Sequence Types/Clusters | Novel Division-Level Lineages Discovered | Affiliation with Known Bacterial Divisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-Independent (16S rRNA cloning) | 54 | 12 candidate divisions | 70% affiliated with 14 known divisions; 30% unaffiliated |

Table 3: Current Scope of Bacterial Phyla and Cultivation Status [8] [25]

| Category | Number of Phyla | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Formally Accepted Bacterial Phyla | 41 | Phyla with validated nomenclature and often cultured representatives. |

| Total Recognized Bacterial Phyla | ~89 | Includes formally accepted and other well-recognized phyla. |

| Phyla with No Cultured Representatives (Candidate Phyla) | ~72% of recognized phyla | Phylogenetic groups known only from environmental sequence data. |

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Diversity Studies

The revelation of novel bacterial divisions relies on specific experimental workflows that contrast traditional and modern techniques.

A. Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Sample Type: Marine sediment samples collected from the South China Sea.

- Storage: Samples transported in sterile tubes and stored at 4°C.

B. Culture-Dependent Isolation and Identification:

- Media: Employ a combination of six different media types (e.g., Emerson agar, Zobell 2216E, R2A agar) to maximize the diversity of cultured isolates. No single medium is sufficient.

- Inoculation: Serially dilute sediment supernatants and spread onto agar plates. Incubate at 16°C until colonies form.

- Identification: Pick colonies based on morphological differences and subculture to purity. Amplify the 16S rRNA gene from pure cultures using primers 27F and 1492R, followed by Sanger sequencing.

C. Culture-Independent Community Profiling (HTS):

- DNA Extraction: Directly extract total genomic DNA from the original sediment sample using a soil DNA extraction kit.

- 16S rRNA Gene Amplification: Amplify the V4-V5 region for HTS using barcoded primers 515F and 806R.

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq PE250 platform.

D. Data Analysis:

- Process HTS reads to cluster into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) at a 97% identity threshold.

- Compare the 16S rRNA gene sequences of cultured isolates against the HTS-derived OTUs to determine the proportion of cultured diversity.

A. Sample Collection:

- Sample Type: Sediment from Obsidian Pool (OP), a Yellowstone National Park hot spring.

B. DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Library Construction:

- Extract total environmental DNA directly from the OP sediment sample.

- Amplify 16S rRNA genes using PCR with universally conserved or Bacteria-specific primers.

- Clone the PCR products into a vector to create a library.

C. Sequence Type Identification:

- Identify unique sequence types among hundreds of clones using Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) analysis.

- Determine the 16S rRNA gene sequence for representative clones from each unique RFLP pattern.

D. Phylogenetic Analysis and Novelty Assessment:

- Compare the obtained 16S rRNA sequences to known sequences in databases.

- Define novel, division-level lineages (candidate divisions) as sequence clusters with ≤ 75% sequence identity to members of other bacterial phyla in their 16S rRNA genes [25].

Workflow Visualization: Contrasting Methodological Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and fundamental differences between the two primary methodological approaches for assessing bacterial diversity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents for Comparative Phylogenetic Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Protocol | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Diverse Culture Media | To maximize the phylogenetic range of cultured isolates by providing varied nutrient sources and conditions. | Emerson Agar, Zobell 2216E, R2A Agar, defined minimal media (e.g., MBM) [3]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit (Soil/Sediment) | To efficiently lyse diverse microbial cells and isolate high-purity, inhibitor-free environmental DNA for HTS. | E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit or equivalent [3]. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers | To amplify the phylogenetic marker gene from both isolates (Sanger) and community DNA (HTS). | Broad-range: 515F/806R (for HTS) [3]; 27F/1492R (for full-length from isolates) [3]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencing Platform | To generate millions of sequence reads from environmental DNA amplicons or metagenomic libraries. | Illumina HiSeq/MiSeq (short-read) [3] [26], Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION (long-read) [26]. |

| Taxonomic Classification Software | To assign sequence reads to taxonomic groups by comparing them to reference databases. | Kraken2, MetaPhlAn3, MEGAN-LR (specialized for long reads) [26]. |

| Reference Sequence Database | To provide a comprehensive set of known sequences for accurate taxonomic classification of HTS data. | SILVA, Greengenes, NCBI RefSeq. Databases must be curated and updated [26]. |

| DCAT Maleate | DCAT Maleate, CAS:57915-90-9, MF:C14H15Cl2NO4, MW:332.18 | Chemical Reagent |

| Hyprolose | Hyprolose (Hydroxypropyl Cellulose) |

The objective comparison of culture-dependent and culture-independent methods confirms a profound impact on phylogenetic understanding. Traditional culturing techniques recover a limited, and often biased, subset of bacterial diversity, predominantly capturing organisms within well-characterized phyla like Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria [3]. In stark contrast, HTS-based approaches have unveiled a vast "microbial dark matter," consisting of hundreds of candidate phyla without cultured representatives [24] [25]. This expansion of known diversity is not merely additive but is reshaping the very structure of the bacterial phylogenetic tree, revealing deeply branching novel divisions and forcing a re-evaluation of evolutionary relationships. For researchers and drug development professionals, this underscores the critical importance of integrating HTS methodologies to access the full genetic and metabolic potential of the bacterial world, much of which resides in these newly revealed divisions.

Methodological Arsenal: From Traditional Culturing to Modern Metagenomics

The comprehensive analysis of microbial communities is a cornerstone of modern microbiology, with significant implications for drug development, environmental science, and human health. This endeavor relies on two complementary approaches: culture-dependent techniques that isolate microorganisms on specific growth media, and culture-independent methods (primarily high-throughput sequencing, HTS) that reveal the total genetic diversity of a sample. A persistent challenge, often termed the "great plate count anomaly," has been the significant discrepancy between the number of microorganisms observed microscopically and those that can be propagated in the laboratory [27]. While this has sometimes led to the perception that cultivation is an outdated technique, contemporary research demonstrates that 35–65% of intestinal microorganisms detected by sequencing have cultivable representatives, challenging the oversimplified notion that only 1% of microbes can be cultured [27]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates culture-dependent methodologies against HTS approaches, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to optimize microbial isolation strategies within the framework of diversity studies.

Comparative Analysis of Cultured vs. Total Bacterial Diversity

Key Discrepancies and Complementarity

High-throughput sequencing provides a powerful, broad-spectrum view of microbial diversity but suffers from limitations in detecting rare populations and differentiating viable from non-viable cells. Conversely, culture-dependent methods enable the isolation of live isolates for functional validation but historically exhibit significant bias toward fast-growing organisms under laboratory conditions. The integration of both approaches reveals a more complete picture of microbial communities, as each method captures unique members of the ecosystem.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent Methods

| Metric | Culture-Dependent Methods | Culture-Independent (HTS) Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion of Community Recovered | ~6% of total OTUs from marine sediment [3] | 100% in theory, but limited by DNA extraction efficiency and primer bias [27] |

| Detection Sensitivity | Can detect bacteria present at <10³ cells per gram [27] | Detection threshold ~10ⶠmicrobial cells per gram for amplicon sequencing [27] |

| Dominant Taxa Identified | Marine sediments: Actinobacteria [3] | Marine sediments: Gammaproteobacteria [3] |

| Unique ASVs Captured | 322 (5.98%) exclusive ASVs in soil study [28] | 4,507 (83.7%) exclusive ASVs in soil study [28] |

| Overlap Between Methods | 234 (4.35%) shared ASVs in soil study [28] | 18% species overlap in human gut study [6] |

| Key Advantage | Provides live isolates for experimental validation and bioprospecting [27] | Captures the full breadth of diversity, including uncultured taxa [3] |

The data reveals that culture-dependent and independent methods are largely complementary. A study on industrial water samples found that the most abundant taxa in the original sample sometimes differed from those that proliferated in culture-dependent tests, highlighting the selection bias of growth media [29]. Similarly, research on the human gut found a surprisingly low overlap, with only 18% of species identified by both culture-enriched metagenomic sequencing (CEMS) and direct metagenomic sequencing (CIMS), while 36.5% of species were identified only by CEMS and 45.5% only by CIMS [6]. This underscores the necessity of a combined approach to minimize the omission of significant microbial populations.

Impact of Media Formulation on Diversity Recovery

The composition of growth media is a critical factor determining which microorganisms can be isolated. Nutrient-richness and the quality of nitrogen sources strongly influence the taxonomic profile of the resulting culture collection.

Table 2: Impact of Media Composition on Culturable Diversity from Marine Sediments [3]

| Medium Type | Key Components | Impact on Bacterial Isolation |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient-Rich (e.g., EM, 2216E) | High concentrations of peptone, yeast extract, beef extract | Supported the growth of relatively few bacterial taxa. |

| Single-Carbon/Nitrogen Source (e.g., CDM, MBM) | Defined single sources (e.g., sodium lactate, KNO₃) | Also supported the growth of relatively few taxa. |

| Low-Nutrient/Multiple-Source (e.g., R2A) | Multiple nutrients at low concentrations (yeast extract, peptone, casein, glucose, starch) | Part of the combination that cultured more taxa than any single medium. |

| Combination of Multiple Media | Various | Cultured significantly more taxa than any single medium used in isolation. |

Studies consistently show that no single medium is sufficient to capture the full cultivable diversity. The use of a Combinational Enhanced Cultivation Strategy (CECS), which employs multiple media formulations, has proven successful in isolating novel strains, such as a red-pigmented Sulfitobacter with bioactivity from seawater [30]. Furthermore, the physical cultivation method itself can introduce bias. The ichip (isolation chip) diffusion system, which allows microorganisms to grow in their natural environment while separated into individual chambers, has been shown to increase the richness and evenness of bacterial isolates from soil compared to conventional petri dish plating, which tends to over-represent fast-growing genera like Pseudomonas [31].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Diversity Studies

Standardized Workflow for Parallel Analysis

To objectively compare culture-dependent and culture-independent diversity, a standardized experimental workflow is essential. The following integrated protocol, synthesizing methods from multiple studies, ensures comparable results.

Figure 1: Integrated experimental workflow for the parallel comparison of culture-dependent and culture-independent microbial diversity.

Detailed Methodological Steps

1. Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Environmental Samples: For marine sediment or soil, collect samples using sterile tools and store in sterile containers at 4°C for short-term transport [3]. For rhizosphere studies, soil attached to plant roots is collected by washing roots in sterile saline buffer [28].

- Human Gut Samples: Fresh fecal samples are collected in airtight sterile tubes and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at -80°C [6].

- Homogenization and Dilution: Suspend a measured amount of sample (e.g., 5.0 g of sediment in 20 mL of sterilized artificial seawater [3] or 0.5 g of feces in 4.5 mL of distilled water [6]) and vortex thoroughly. Prepare tenfold serial dilutions in a sterile diluent such as 0.85% NaCl solution.

2. Culture-Dependent Isolation (Plating and Incubation):

- Media Selection: Plate from appropriate dilutions (e.g., 10â»âµ and 10â»â¶ for soil [28]) onto a diverse panel of media. The following table provides a list of essential research reagents.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Isolation

| Reagent/Medium | Function / Target Organisms | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| R2A Agar | Isolation of slow-growing and oligotrophic bacteria; general heterotrophs [3] [28]. | Used for isolating bacteria from marine sediment [3] and soil [28]. |

| TruePRAS Media | Cultivation of fastidious and strict anaerobic organisms; pre-reduced to prevent oxygen damage [32]. | Essential for cultivating anaerobic gut microbiota [32]. |

| Zobell 2216E | A standard, nutrient-rich medium for the isolation of marine heterotrophic bacteria [3]. | Used for isolating bacteria from marine environments [3]. |

| Actinomycetes Isolation Agar | Selective isolation of Actinomycetes from complex samples [28]. | Used in soil rhizosphere studies [28]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Provides an oxygen-free atmosphere (e.g., 95% Nâ‚‚, 5% Hâ‚‚) for cultivating anaerobic microbes [6]. | Used for cultivating gut microbiota [6]. |

| Isolation Chip (ichip) | In-situ cultivation device; reduces bias by allowing growth in a natural chemical environment [31]. | Increased culturable diversity from soil samples compared to plates [31]. |

- Incubation Conditions: Incubate plates in both aerobic and anaerobic atmospheres. Temperatures should reflect the sample's origin (e.g., 16°C for deep-sea samples [3], 37°C for human gut [6]). Extend incubation times to several days or weeks to recover slow-growing organisms.

- Colony Processing: After incubation, use one of two approaches:

- Experienced Colony Picking (ECP): Pick colonies of varying morphologies for purification and Sanger sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene [6].

- Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS): Harvest all biomass from the plate surface using a sterile scraper into a saline solution. Centrifuge and use the pellet for metagenomic DNA extraction [6]. This high-throughput approach avoids the bias of manual colony selection.

3. Culture-Independent Analysis (HTS):

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA directly from the original sample using specialized kits (e.g., QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit for feces [6], PowerSoil DNA Extraction Kit for soil [28]).

- 16S rRNA Gene Amplification and Sequencing: Amplify the V3-V4 or V4 hypervariable regions using primer pairs such as 515F/806R [3] [29] or 341F/785R [28]. Perform sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq or HiSeq platform.

- Bioinformatic Processing: Process raw sequences using pipelines like QIIME2 or DADA2 to quality-filter reads, denoise, and cluster into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) [30] [28]. Assign taxonomy using reference databases like SILVA.

Discussion and Best Practice Recommendations

The experimental data clearly demonstrates that a synergistic approach, leveraging both culture-dependent and independent methods, is paramount for a comprehensive understanding of microbial diversity. To maximize the yield and value of cultivation efforts, researchers should adopt the following strategies:

- Employ Medium Multiplicity: Never rely on a single medium. Use a combination of nutrient-rich, oligotrophic, selective, and defined media to mimic a wide range of physiological niches. Low-nutrient media like R2A are often superior for isolating a broader range of taxa from natural environments [3].

- Leverage High-Throughput Cultivation Techniques: To overcome the biases and low throughput of manual colony picking, adopt methods like CEMS [6] or microfluidic streak plates [31]. These approaches allow for the genomic characterization of nearly all cultured organisms, including those that would be overlooked visually.

- Mimic the Natural Environment: Utilize devices like the ichip [31] and consider supplementing media with signaling molecules or growth factors from the native habitat to cultivate the elusive "unculturable" majority.

- Utilize Sequencing Data to Guide Cultivation: Metagenomic data can predict functional potential and metabolic requirements of uncultured taxa. This information can be used to design bespoke media, a strategy increasingly used to target specific microbial dark matter.

In the context of comparing cultured versus total bacterial diversity, culture-dependent techniques remain an indispensable tool. While HTS provides the overarching blueprint of microbial community structure, cultivation validates the existence of live, functional organisms and provides the pure strains necessary for mechanistic studies, drug discovery, and biotechnological application. The future of microbial ecology lies not in choosing one method over the other, but in the intelligent integration of both, using HTS data to continuously refine and improve cultivation protocols. By adopting the combinational strategies, advanced protocols, and reagents outlined in this guide, researchers can significantly bridge the gap between the cultured and the uncultured, unlocking a deeper understanding of the microbial world.

High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) of the 16S rRNA gene has revolutionized microbial ecology by providing a culture-independent method to profile complex bacterial communities directly from their environments. This amplicon sequencing approach allows researchers to characterize the "total" diversity, including a vast number of uncultured microorganisms, and compare it directly with the "cultured" diversity obtained through traditional plate-based methods [33] [5]. While it is estimated that approximately 80% of bacteria detected with molecular tools are uncultured, making 16S metabarcoding a powerful tool for diversity surveys, culture-based approaches remain essential for studying the physiology, ecology, and genomic content of isolates [33] [34]. This guide objectively compares the performance of Illumina MiSeq, a dominant benchtop HTS platform, against alternative sequencing technologies and culture-based methods, providing supporting experimental data to inform researcher selection.

Technology Comparison: Illumina MiSeq vs. Other Sequencing Platforms

The selection of a sequencing platform significantly influences the resolution, accuracy, and depth of 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing results. Here we compare Illumina MiSeq with other common technologies.

Key Performance Metrics Across Platforms

Experimental data from comparative studies reveal distinct performance characteristics across major sequencing platforms, influencing their suitability for specific research goals.

Table 1: Performance comparison of sequencing platforms for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing.

| Platform | Typical Read Length | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Species-Level Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina MiSeq | 250-600 bp (paired-end) [35] [36] | High throughput, low per-base cost, low error rates [37] [38] | Short reads limit phylogenetic resolution for some regions [35] | ~47% of sequences classified [35] |

| Ion Torrent PGM | 400 bp [37] | Fast run times [37] | Higher error rates, premature truncation on homopolymers [37] | Varies; organism-specific biases reported [37] |

| PacBio HiFi | ~1,450 bp (full-length 16S) [35] | Full-length gene sequencing, high fidelity (Q27) [35] | Higher cost per sample, lower throughput | ~63% of sequences classified [35] |

| ONT MinION | ~1,400 bp (full-length 16S) [35] | Long reads, real-time sequencing, portable [35] [39] | Higher raw error rate, though improved with new chemistries [35] | ~76% of sequences classified [35] |

Experimental Data from Comparative Studies

A 2014 benchmark study directly compared Illumina MiSeq and Ion Torrent PGM for sequencing the V1-V2 region of the 16S rRNA gene. The study reported comparatively higher error rates with the Ion Torrent platform and identified a pattern of premature sequence truncation dependent on sequencing direction and target species, resulting in organism-specific biases [37]. In contrast, Illumina demonstrated more consistent performance across a mock community and human-derived specimens [37].

A 2025 study compared Illumina (V3-V4 region) with PacBio HiFi and ONT (both full-length 16S) for characterizing rabbit gut microbiota. While long-read platforms showed higher theoretical species-level resolution, a significant portion of classifications were labeled as "uncultured_bacterium," limiting practical insights. Furthermore, the relative abundances of major microbial families (e.g., Lachnospiraceae) differed substantially between platforms, with ONT reporting nearly double the abundance of Lachnospiraceae compared to Illumina [35].

16S Amplicon Sequencing vs. Culture-Dependent Methods

The integration of HTS and culture-based methods provides a more comprehensive understanding of microbial communities.

Methodological Comparison and Overlap

Table 2: Comparing culture-dependent and 16S amplicon sequencing approaches.

| Aspect | Culture-Dependent Methods | 16S Amplicon Sequencing (Illumina) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Growth on selective/non-selective media | PCR amplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA gene [38] |

| View of Diversity | Captures a cultivable subset ("culturable") [5] | Culture-independent profile of "total" diversity [33] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Can be high for isolated strains | Varies by region; species-level can be challenging [35] |

| Functional Insights | Enables physiological and genomic studies of isolates [34] | Inferred from taxonomy; no direct functional data |

| Key Limitation | Great Plate Count Anomaly (<1% cultured) [5] | Does not distinguish viable from non-viable cells |

The overlap between these methods is often small. One study on marine sediments found that only 6% of the total operational taxonomic units (OTUs) from the HTS dataset were recovered in the culture collection [3]. Similarly, a study on the wheat rhizosphere found that improved cultivation methods increased the recovery of bacteria to only 1.86% to 2.52% of the OTUs observed in metagenomic data, compared to less than 1% with standard protocols [5]. This highlights the vast uncultured diversity that HTS can access.

Synergistic Applications in Research

Culture-based methods can be strategically used to investigate rare members of the community detected by HTS. A study on river water samples demonstrated that 16S metabarcoding of culture-derived bacterial lawns could accurately detect rare environmental bacteria, such as those from the Pectobacterium genus, which were not abundant in the direct environmental HTS profile [33]. This shows that culturing can enrich for specific, sometimes rare, taxa, allowing for their detection and subsequent isolation.

Furthermore, the composition of the culture medium itself is a powerful selective factor. Research has shown that using a combination of media cultured more taxa than any single medium, with nutrient-rich media often supporting the growth of relatively few taxa compared to low-nutrient or multiple-carbon/nitrogen-source media [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for method selection, here are detailed protocols for key experiments cited.

Protocol 1: Standard Illumina MiSeq 16S Library Preparation (V3-V4 Region)

This protocol is adapted from the official Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation guide and demonstrated in multiple studies [35] [36].

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from samples (e.g., fecal, soil, water) using a commercial kit such as the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN).

- First-Stage PCR - Amplicon PCR:

- Primers: Amplify the V3-V4 hypervariable region using the primer pair:

- Reaction: Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix) [36].

- Cycling Conditions:

- Library Indexing: A second, limited-cycle PCR step is performed to attach dual indices and sequencing adapters using a kit such as the Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina) [35] [36].

- Library Pooling & Normalization: Purify the amplified libraries, quantify, and pool in equimolar ratios.

- Sequencing: Denature the pooled library and load onto the MiSeq system for 250-300 bp paired-end sequencing using a v2 or v3 reagent kit [36].

Protocol 2: Culturing and DNA Extraction from Bacterial Lawns for Metabarcoding

This protocol, derived from Giraud et al. (2020), allows for direct comparison of cultured and total bacterial communities from the same sample [33].

- Sample Inoculation: Spread plate a volume of the environmental sample (e.g., 100 µL of filtered river water suspension) onto the desired solid media (e.g., TSA 10%, R2A, or selective media).

- Incubation: Incubate plates at an appropriate temperature (e.g., 28°C) until a confluent bacterial lawn forms (typically 2-3 days).

- Lawn Harvesting: Add a known volume of sterile water (e.g., 2 mL) to the plate surface and gently scrape the bacterial lawn off using a sterile spreader.

- DNA Extraction from Lawn: Use an aliquot of the resulting suspension (e.g., 200 µL) for genomic DNA extraction with a standard kit (e.g., Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit) [33].

- Downstream Analysis: The extracted DNA is then used for 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing using the same primers and pipeline as the direct environmental sample, enabling a direct comparison.

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for comparing cultured and total bacterial diversity using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, as described in the experimental protocols.

Diagram Title: Integrated Workflow for Culture and HTS Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and culture comparisons relies on specific reagents and kits. The following table details essential solutions for the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and kits for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and culture work.

| Category | Product / Solution Example | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) [35] [36] | Efficiently extracts microbial genomic DNA from complex samples like soil and feces, critical for accurate HTS. |

| PCR Amplification | KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche) [35] [36] | High-fidelity polymerase for accurate amplification of the 16S rRNA gene with minimal errors. |

| Library Preparation | Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina) [35] [36] | Provides primers for indexing and adding flow cell adapters, enabling multiplexed sequencing on Illumina platforms. |

| Broad-Range Media | TSA 10% / R2A Agar [33] [3] | General-purpose, nutrient-reduced media for cultivating a wider diversity of heterotrophic bacteria from environmental samples. |

| Gelling Agents | Phytagel / Gelrite [5] | Agar alternatives that, when autoclaved separately from phosphate, reduce hydrogen peroxide formation and can improve culturability of recalcitrant bacteria. |

| Bioinformatics | QIIME 2 / DADA2 [35] [36] | Standardized pipelines for processing raw sequencing data, including denoising, chimera removal, and generating Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs). |

| KRH102140 | KRH102140, CAS:864769-01-7, MF:C25H24FNO, MW:373.4714 | Chemical Reagent |

| Lankanolide | Lankanolide|Research Use Only |

Illumina MiSeq 16S amplicon sequencing provides a robust, high-throughput, and cost-effective method for profiling total bacterial communities, uncovering diversity far beyond the reach of culture alone. However, platform choice and primer selection introduce specific biases, and taxonomic resolution at the species level can be limited. The most powerful insights into microbial ecology often come from a synergistic approach that leverages the broad, culture-independent view offered by HTS with the targeted, functional validation enabled by cultured isolates. This integrated strategy is pivotal for moving beyond cataloging diversity to understanding the functional roles of microbes in health, disease, and the environment.