Evaluating Commercial Kits for Unidentified Bacteria: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to evaluate and select commercial kits for identifying unknown bacterial isolates.

Evaluating Commercial Kits for Unidentified Bacteria: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to evaluate and select commercial kits for identifying unknown bacterial isolates. It explores the foundational principles of bacterial identification technologies, details methodological applications across diverse sample types, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for common challenges, and establishes rigorous protocols for kit validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing current methodologies and emerging trends, this guide aims to enhance diagnostic accuracy, streamline laboratory workflows, and inform strategic decisions in biomedical research and clinical development.

The Evolving Landscape of Bacterial Identification Technologies

The field of bacterial identification has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from traditional biochemistry techniques reliant on phenotypic characteristics to modern platforms that leverage molecular and computational technologies. This shift addresses critical limitations of classical methods, including slow turnaround times, subjective interpretation, and the inability to identify unculturable or rare species [1]. Traditional techniques, such as spectrophotometry and enzyme kinetics described by Michaelis and Menten over a century ago, established the fundamental principles of quantifying biochemical reactions but often lacked the sensitivity and specificity required for precise microbial characterization [2] [1]. The contemporary landscape now integrates these classical principles with high-throughput genomic tools, advanced biosensors, and artificial intelligence, creating a powerful synergy that enhances diagnostic precision and operational efficiency in research and clinical settings [3].

This transition is particularly crucial for evaluating commercial kits in unidentified bacteria research. Modern platforms must demonstrate not only superior analytical performance but also practical advantages in workflow integration, cost-effectiveness, and accessibility. The convergence of traditional biochemical knowledge with digital biomarker tracking through miniaturized, AI-assisted devices represents a new era in translational diagnostics, enabling real-time, data-driven decision-making at the point-of-care [3]. This review objectively compares the performance of traditional biochemical methods against emerging technological platforms, providing researchers with experimental frameworks and data-driven insights to guide their selection of appropriate identification strategies.

Historical Foundation: Traditional Biochemical Approaches

Core Principles and Methodologies

Traditional biochemical identification of bacteria fundamentally relies on detecting specific enzymatic activities or metabolic capabilities through observable phenotypic changes. The theoretical foundation rests upon classical enzymology, particularly the Michaelis-Menten model of enzyme kinetics developed in the early 20th century [2]. This model describes how enzyme-catalyzed reaction rates depend on substrate concentration, characterized by the Michaelis constant (KM) and maximum velocity (Vmax) parameters. These familiar arithmetic concepts from classical enzymology are derived from more fundamental networks of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) describing dynamical systems under mass action approximations [2].

The Briggs-Haldane formulation of Michaelis-Menten kinetics, which assumes the enzyme-substrate complex rapidly achieves a steady state rather than true equilibrium, provides the conceptual framework for many biochemical tests used in bacterial identification [2]. These tests typically involve inoculating bacterial samples into substrates containing specific biochemicals and observing color changes, gas production, or pH shifts that indicate metabolic activity. These methods focus on enzymatic reactions studied under controlled, well-mixed conditions similar to the in vitro approaches that defined early enzymology [2].

Experimental Protocols for Traditional Biochemistry

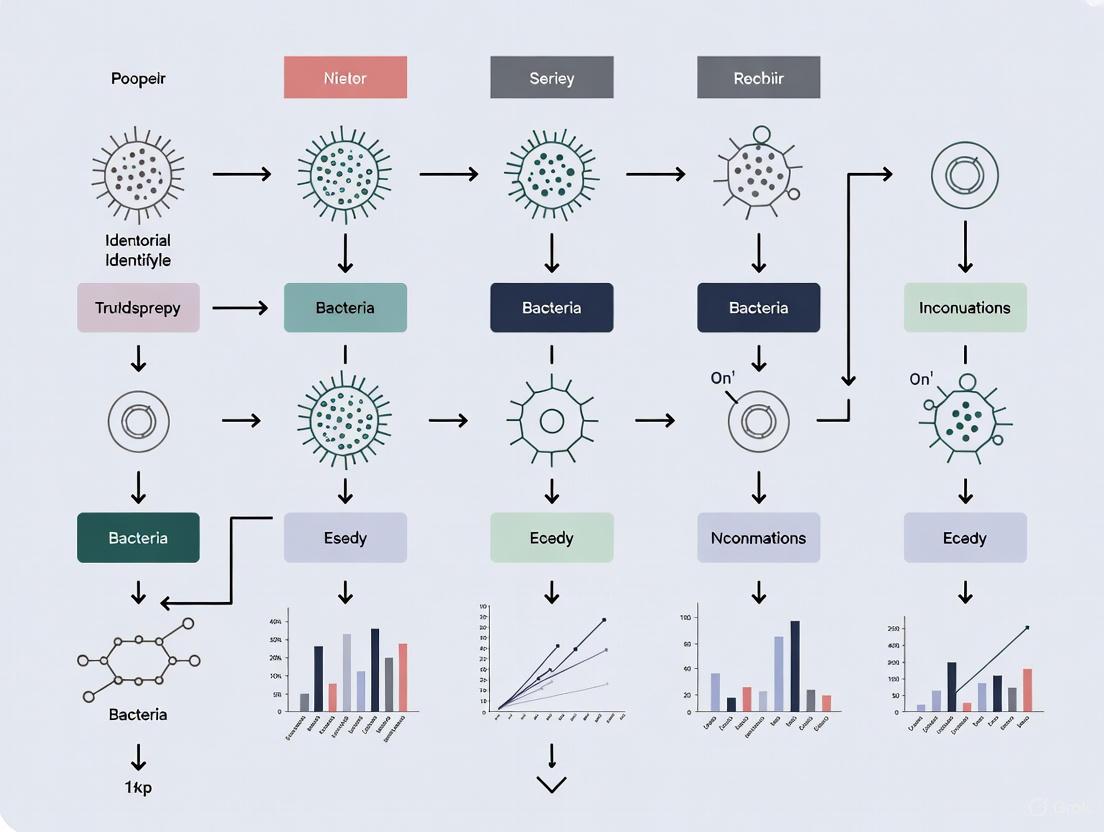

Standard protocols for traditional biochemical identification follow a consistent workflow, represented in the diagram below:

Diagram: Workflow for Traditional Biochemical Bacterial Identification

The specific methodology for a conventional biochemical test panel involves:

- Pure Culture Preparation: Isolate single bacterial colonies on non-selective media and confirm purity through Gram staining and microscopic examination.

- Test System Inoculation: Using sterile technique, prepare a standardized suspension of the bacterial isolate in saline (0.5 McFarland standard). Inoculate each well of a commercial biochemical test panel (e.g., API, VITEK) according to manufacturer specifications.

- Incubation: Seal the test panel and incubate under appropriate atmospheric conditions (aerobic, anaerobic, or microaerophilic) at 35±2°C for 18-48 hours, depending on the expected growth characteristics of the organism.

- Result Interpretation: Following incubation, record color changes in each cup resulting from pH shifts, substrate utilization, or metabolic byproducts. Some tests may require the addition of reagents to visualize specific reactions.

- Identification: Convert the pattern of positive and negative reactions to a numerical code and consult a taxonomic database to determine the most probable species identification, typically expressed with a confidence percentage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Traditional Methods

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Traditional Biochemical Identification

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Media | Suppresses unwanted flora while promoting growth of target bacteria | MacConkey Agar (gram-negative rods), Columbia CNA Agar (gram-positive cocci) |

| Carbohydrate Substrates | Tests fermentation capabilities | Glucose, Lactose, Sucrose in Phenol Red Broth |

| Amino Acid Decarboxylases | Detects amino acid metabolism | Lysine, Ornithine, Arginine decarboxylase tests |

| Enzyme Substrates | Identifies specific enzymatic activities | ONPG (β-galactosidase), Tryptophan (Indole production) |

| Oxidative-Fermentative Media | Differentiates metabolic pathways | Hugh-Leifson OF Basal Medium |

| Commercial Test Panels | Standardized multi-test systems | API 20E, VITEK 2 GN Card |

| KRCA-0008 | KRCA-0008, MF:C30H37ClN8O4, MW:609.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Hydroxypentadecane-4-one | 3-Hydroxypentadecane-4-one, MF:C15H30O2, MW:242.40 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Modern Platforms: Technological Advancements

Molecular and Mass Spectrometry Approaches

Modern platforms for bacterial identification have largely transitioned to molecular techniques that offer superior speed, specificity, and automation compared to traditional methods. Mass spectrometry (MS), particularly Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight (MALDI-TOF), has revolutionized clinical microbiology by enabling rapid identification based on unique protein profiles [1]. This technology generates a characteristic mass spectral fingerprint from bacterial ribosomal proteins, which is compared against an extensive database for identification.

Advanced molecular methods include:

- PCR and Sequencing: Amplification and analysis of conserved genomic regions (e.g., 16S rRNA gene) provides species-level identification, especially valuable for unculturable or fastidious organisms [4].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Whole-genome sequencing offers the highest resolution for strain typing and detecting virulence markers, though at higher cost and complexity [1].

- Lab-on-a-Chip (μTAS): Microfluidic platforms miniaturize laboratory processes, enabling portable, rapid testing with minimal sample volumes suitable for point-of-care applications [1].

These technologies demonstrate significant advantages in sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional methods. Mass spectrometry provides up to 1,000 times lower detection levels for some analytes compared to spectrophotometric methods, a critical advantage for early disease diagnosis [1].

Experimental Protocols for Modern Platforms

The workflow for modern bacterial identification using molecular methods follows a distinct pathway:

Diagram: Workflow for Modern Bacterial Identification Platforms

The specific methodology for PCR-based bacterial identification with contamination controls involves:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Using a laminar flow hood dedicated to PCR preparation, extract bacterial DNA from pure cultures or clinical samples using a commercial kit. Include extraction controls without sample to monitor reagent contamination.

- PCR Reaction Setup: Prepare reactions under aseptic technique using PCR-grade water and reagents. Include both positive control (bacterial DNA with known sequence) and negative control (no-template water) reactions for every assay run. Reaction components typically include: DNA template, PCR buffer, dNTP mix, forward and reverse primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene, DNA polymerase, and MgClâ‚‚ [4].

- Thermal Cycling: Amplify target sequences using standardized cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes [4].

- Amplicon Analysis: Separate PCR products by gel electrophoresis (1% agarose), visualize with SYBRsafe staining, and perform size selection of appropriate bands (approximately 500 bases for the V3-4 region of bacterial 16S rRNA) for sequencing [4].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Submit purified amplicons for Sanger sequencing. Trim sequence ends to remove unidentified bases, ensuring the first and last included base has a quality score ≥20. Query trimmed sequences against the NCBI GenBank database using megablast to identify the closest matches based on percent coverage and identity [4].

Critical Consideration: Contamination in Molecular Methods

A significant challenge in modern bacterial identification, particularly for low-biomass samples, is bacterial DNA contamination of laboratory reagents. Recent research examining nine different commercial PCR enzymes found contaminating bacterial DNA in seven of them, originating from a variety of species [4]. This contamination can lead to false-positive results and erroneous conclusions in microbiome studies. The implementation of rigorous negative controls is therefore essential, and this validation can be achieved using accessible methods like endpoint PCR and Sanger sequencing without requiring expensive high-throughput technologies [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Modern Platforms

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Modern Identification Platforms

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Kit |

| PCR Master Mixes | Optimized enzymes and buffers for amplification | Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase, Q5 High-Fidelity Master Mix |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Amplification of conserved bacterial regions | 27F/1492R for full-length 16S, V3-4 primers for Illumina |

| Mass Spectrometry Matrix | Energy-absorbing molecules for MALDI-TOF | α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA) |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Analysis of sequencing data | QIIME 2, MEGAN, SPeDE |

| Commercial ID Systems | Integrated identification platforms | Bruker MALDI Biotyper, bioMérieux VITEK MS |

| Lanopepden | Lanopepden, CAS:1152107-25-9, MF:C22H34FN7O4, MW:479.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lappaol F | Lappaol F, CAS:69394-17-8, MF:C40H42O12, MW:714.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Bacterial Identification Methods

| Parameter | Traditional Biochemistry | Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) | PCR & Sequencing | NGS Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Result | 24-48 hours | 10-30 minutes | 4-8 hours | 1-3 days |

| Sample Volume | Medium (1-5 mL) | Low (1 μL) | Low (50-200 μL) | Very Low (<50 μL) |

| Analytical Sensitivity | Moderate | High | Very High | Extremely High |

| Species Discrimination | Fair to Good | Excellent | Excellent | Superior (strain-level) |

| Capital Cost | Low | Medium-High | Medium | High |

| Cost per Test | Low | Low | Medium | High |

| Hands-on Time | High | Low | Medium | Medium-High |

| Database Dependence | Moderate | High | High | High |

| Automation Potential | Low | High | Medium | High |

Analytical Characteristics and Limitations

The performance data reveal distinct advantages and limitations for each methodological approach. Traditional biochemical methods offer cost-effectiveness and operational simplicity but demonstrate limited sensitivity and specificity compared to modern platforms [1]. These limitations become particularly problematic when identifying fastidious organisms or distinguishing between closely related species with similar biochemical profiles.

Mass spectrometry achieves significantly shorter turnaround times (10-30 minutes versus 24-48 hours) while maintaining high accuracy for most common pathogens [1]. However, this technology requires substantial capital investment and struggles with differentiating certain closely related species, such as Shigella and Escherichia coli.

Molecular methods provide the highest sensitivity and specificity, with PCR-based techniques detecting pathogens present in very low numbers that would be missed by traditional culture-based methods [4]. The comprehensive genomic analysis provided by NGS enables strain-level discrimination essential for outbreak investigations, though at higher cost and computational requirements [1].

A critical consideration for molecular methods is reagent contamination, as demonstrated by studies finding bacterial DNA in commercial PCR enzymes [4]. This contamination can significantly impact results in microbiome studies of low-biomass samples, necessitating appropriate negative controls and careful data interpretation.

The evolution from traditional biochemistry to modern platforms represents a paradigm shift in bacterial identification, moving from phenotypic characterization to genotypic analysis. While traditional methods established the fundamental principles of biochemical testing, contemporary technologies offer unprecedented speed, sensitivity, and discrimination capabilities. The optimal approach often involves a complementary strategy, using rapid mass spectrometry for routine identification while reserving molecular methods for complex cases requiring strain-level discrimination.

Future advancements will likely focus on integrating artificial intelligence with portable biosensing technologies to create increasingly automated and accessible diagnostic platforms [3]. These systems will leverage the growing availability of digital biomarkers through wearable devices and miniaturized analytical platforms, potentially enabling real-time monitoring of microbial populations. However, regardless of technological sophistication, proper validation and contamination controls remain essential, as even advanced molecular methods can be compromised by reagent contamination [4]. As the field continues to evolve, the successful integration of traditional biochemical knowledge with cutting-edge technologies will drive the next generation of identification platforms, enhancing both diagnostic precision and global accessibility.

The accurate identification of bacterial isolates is a cornerstone of microbiological research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development. As bacterial resistance and emerging pathogens present ongoing challenges, the reliability of identification methods directly impacts research outcomes and therapeutic strategies. This guide provides an objective comparison of the three core methodological pillars—biochemical, immunological, and molecular techniques—framed within a broader thesis on evaluating commercial kits for unidentified bacteria research. By presenting standardized experimental data and detailed protocols, this article serves as a reference for researchers and scientists in selecting the most appropriate identification pathway for their specific applications.

Bacterial identification methods are characterized by their fundamental principles, targeting different bacterial attributes: metabolic profiles, antigenic structures, and genetic sequences. The following table provides a high-level comparison of these core methodologies.

Table 1: Core Principles of Bacterial Identification Methods

| Feature | Biochemical Methods | Immunological Methods | Molecular Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Detection of metabolic enzymes and byproducts | Detection of specific antigen-antibody interactions | Detection of unique nucleic acid sequences |

| Target Analyte | Substrates, enzymes, metabolites (e.g., sugars, proteins) | Surface antigens (e.g., O, H, K antigens), toxins | DNA or RNA sequences (e.g., 16S rRNA, virulence genes) |

| Typical Timeframe | 24-48 hours | Minutes to hours | Several hours to 24 hours |

| Specificity | Moderate to High (species level) | Very High (serotype level) | Very High (strain level possible) |

| Sensitivity | Moderate (requires pure culture) | High | Very High (single copy detection) |

| Key Advantage | Cost-effective, provides functional data | Rapid, can be used for direct detection | High specificity and sensitivity, definitive |

| Primary Limitation | Slow, dependent on bacterial growth | Requires specific antibodies, cross-reactivity | Higher cost, technical expertise required |

The choice among these methods depends on the research question, required speed, specificity, and available resources. Immunological methods leverage the high specificity of antibody-antigen binding, often providing results rapidly, which is crucial in clinical and outbreak settings [5]. Molecular methods, such as PCR, offer high sensitivity and specificity by amplifying and detecting unique genetic markers, making them a powerful tool for identifying unculturable organisms or for genotyping [6]. Biochemical methods, while generally slower, provide valuable information on the metabolic capabilities of the bacterium, which can be functionally relevant.

Experimental Protocols for Core Identification Techniques

Protocol for Immunological Identification via Enzyme Immunoassay (ELISA)

The following workflow details the steps for identifying bacterial antigens using a direct ELISA protocol, a common format in commercial kits.

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Coating: Dilute the bacterial lysate or suspension in a suitable carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6). Add 100 µL of the solution to each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. Incubate the plate overnight at 4°C to allow antigens to adsorb to the well surface [6].

- Washing: Empty the contents of the wells and wash them three times with 300 µL of a phosphate-buffered saline solution containing a detergent (e.g., 0.05% Tween 20, PBS-T). This removes unbound proteins.

- Blocking: Add 200 µL of a blocking agent (e.g., 1-5% Bovine Serum Albumin or non-fat dry milk in PBS) to each well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature to cover any unsaturated binding sites on the plastic.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Remove the blocking solution and add 100 µL of the specific primary antibody (e.g., mouse anti-target bacteria monoclonal antibody) diluted in blocking buffer. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature [6].

- Washing: Wash the plate three times with PBS-T as before.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Add 100 µL of an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP)-linked anti-mouse immunoglobulin) diluted in blocking buffer. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature, protected from light [6].

- Washing: Perform a final wash step three times with PBS-T.

- Signal Detection: Prepare the enzyme substrate solution immediately before use. For HRP, Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) is a common substrate. Add 100 µL of the substrate solution to each well and incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes.

- Reaction Stopping and Reading: Stop the enzymatic reaction by adding 50 µL of a stop solution (e.g., 1M sulfuric acid for TMB). The color will change from blue to yellow. Immediately measure the absorbance of each well at 450 nm using a microplate reader. A signal significantly higher than the negative control indicates a positive identification.

Protocol for Molecular Identification via Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

The workflow below outlines the key steps for bacterial identification through conventional PCR and result analysis.

Detailed Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from a pure bacterial culture using a commercial kit. This typically involves enzymatic lysis (e.g., with lysozyme), chemical lysis (with detergents), and mechanical disruption (bead beating). The DNA is then purified from proteins and other contaminants, often through a silica membrane column, and eluted in water or TE buffer [6].

- PCR Reaction Setup: Prepare a PCR master mix on ice to include:

- Nuclease-free water

- PCR Buffer (with MgClâ‚‚)

- dNTPs (deoxynucleotide triphosphates)

- Forward and Reverse Primers (specific to a target gene like 16S rRNA or a virulence gene)

- Thermostable DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase) Aliquot the master mix into PCR tubes and add a small volume of the extracted template DNA.

- Thermal Cycling: Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run a program such as:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Amplification (30-40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: 50-65°C (primer-specific) for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of amplicon.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C ∞.

- Amplicon Analysis: Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis. Mix a portion of the PCR product with a loading dye and load it into a well of an agarose gel (1-2%) containing a DNA intercalating dye. Run the gel at a constant voltage alongside a DNA molecular weight ladder. Visualize the gel under UV light. The presence of a band at the expected size confirms the identification of the target bacterium [6].

Performance Data from Experimental Studies

Performance of Immunological and Molecular OT Diagnostics

A 2024 study on ocular toxoplasmosis (OT) provides a direct comparison of serological (immunological) and PCR-based (molecular) techniques, highlighting their relative sensitivities across different sample types. The data demonstrates the critical impact of the sample matrix on test performance [6].

Table 2: Comparison of Diagnostic Techniques for Ocular Toxoplasmosis

| Method | Sample Type | Target | Patient Group | Positivity Rate | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serology (IFAT/ELISA) | Serum | Anti-T. gondii IgG | Active OT (G1) | Highest Positivity | Effective for systemic confirmation [6] |

| Serology (ELISA) | Tear Fluid | Anti-T. gondii IgA | All Patients (G1-G3) | 9.2% | Less invasive alternative with potential [6] |

| Nested PCR | Blood | GRA7 gene | All Patients | 24.4% | Highest blood-based molecular target [6] |

| Nested PCR | Tear Fluid | B1 gene | All Patients | 15.0% | Highest tear-based molecular target [6] |

Evaluation of Rapid Antigen Tests

A 2022 study on COVID-19 rapid antigen tests (immunological) provides a clear framework for evaluating commercial kit performance against a molecular gold standard, underscoring the influence of viral load.

Table 3: Performance of Two Rapid Antigen Test Kits vs. rRT-PCR

| Test Kit | Sensitivity (Overall) | Specificity (Overall) | Sensitivity (Ct < 25) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SQ RAT | 77.1% (101/131) | 100% (215/215) | > 85% [5] |

| ND RAT | 89.3% (117/131) | 100% (215/215) | > 85% [5] |

Note: rRT-PCR = real-time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction; Ct = Cycle threshold, a proxy for viral load (lower Ct = higher viral load).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Bacterial Identification

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Antibodies | Bind to unique bacterial surface antigens for detection. | Primary capture/detection antibody in ELISA or Lateral Flow Assays [6]. |

| Oligonucleotide Primers | Short DNA sequences designed to bind and amplify unique bacterial genes. | Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene for species identification via PCR [6]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands from a template. | Essential component of PCR master mix for target gene amplification [6]. |

| Enzyme Substrates | Compounds converted by an enzyme (e.g., HRP) to produce a detectable signal. | TMB substrate for ELISA, producing a colorimetric change for quantification [6]. |

| Enrichment Broths | Culture media designed to support the growth of specific bacteria. | Selective enrichment of a pathogen from a complex sample prior to DNA extraction or immunoassay. |

| Agarose | Polysaccharide used to create a matrix for separating DNA fragments by size. | Gel electrophoresis to visualize and confirm the size of PCR amplicons [6]. |

| Laquinimod | Laquinimod, CAS:248281-84-7, MF:C19H17ClN2O3, MW:356.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Larazotide Acetate | Larazotide Acetate | Tight Junction Regulator | RUO | Larazotide acetate is a synthetic peptide for research into celiac disease and intestinal barrier function. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The comparative data and protocols presented here underscore a central tenet in modern bacteriology: no single method is universally superior. The optimal identification strategy often involves a complementary approach. Immunological tests like ELISA offer robust and rapid screening [5], while molecular techniques like (Nested) PCR provide definitive confirmation with high sensitivity, especially when using optimized genetic targets like GRA7 or B1 [6].

The choice of biological sample (e.g., serum vs. tear fluid) significantly impacts the performance of any method, highlighting the need for thorough validation [6]. For researchers evaluating commercial kits, critical assessment parameters must include sensitivity and specificity against a recognized gold standard, the time-to-result, cost, and the technical skill required. The prozone phenomenon, a rare artifact in immunological tests leading to false negatives, is a reminder that understanding the limitations and potential interferences of any chosen method is crucial for accurate interpretation of results [5]. Ultimately, a strategic combination of these core principles—biochemical, immunological, and molecular—forms the most powerful toolkit for the unambiguous identification of unknown bacteria in research and development.

The global market for bacterial identification tools and detection kits is experiencing a period of robust growth, propelled by the escalating challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), rising incidences of infectious diseases, and stringent safety regulations across healthcare and industrial sectors [7] [8] [9]. This market encompasses a diverse range of technologies, from traditional phenotypic methods to advanced molecular and genotypic systems, all aimed at providing rapid and accurate identification of bacterial pathogens [10]. Key players are actively engaged in innovation and strategic collaborations to enhance their product portfolios and geographic reach [11] [8]. The market is characterized by a distinct shift from conventional culture-based techniques toward rapid, automated, and high-throughput solutions such as MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, PCR, and next-generation sequencing (NGS), which offer significant reductions in turnaround time from days to hours [8] [10]. North America currently dominates the market landscape, but the Asia-Pacific region is poised to exhibit the highest growth rate in the coming years, driven by improving healthcare infrastructure and growing health awareness [8] [9] [10]. Future growth will be catalyzed by technological advancements, including the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning for data analysis, the development of portable point-of-care devices, and the increasing demand for at-home testing kits [7] [8] [12].

The bacterial identification market is a multi-billion dollar industry with strong growth projections through the next decade, though reported figures vary slightly depending on the specific market segment analyzed (e.g., broad bacteriological testing versus specific identification tools).

Table: Global Market Size and Growth Projections

| Market Segment | 2024/2025 Base Value | 2030/2032 Projected Value | CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Identification Market | USD 4.55 Billion (2025) | USD 10.01 Billion (2032) | 11.9% | [10] |

| Bacteriological Testing Market | USD 25.83 Billion (2025) | USD 37.26 Billion (2030) | 7.6% | [7] |

| Bacteria Detection Kits Market | ~USD 1.5 Billion (2024) | ~USD 2.9 Billion (2033) | ~8.5% | [13] |

This growth is primarily driven by several key factors:

- Rising Infectious Diseases and AMR: The increasing global burden of infectious diseases and the dire threat of antimicrobial resistance are creating an urgent need for rapid, accurate diagnostics. A report cited that drug-resistant infections could lead to over 39 million direct deaths worldwide in the next 25 years, highlighting the critical role of advanced diagnostics [8].

- Stringent Regulatory Requirements: Governments and regulatory bodies worldwide are enforcing stricter safety standards in the food and beverage, pharmaceutical, and water industries, mandating frequent and reliable microbiological testing [7] [9].

- Technological Advancements: Continuous innovation in molecular diagnostics, automation, and miniaturization is making rapid testing more accessible, cost-effective, and user-friendly, thereby expanding its adoption [8] [10].

Market Segmentation

The bacterial identification market can be segmented by technology, application, end-user, and product type, each with distinct growth dynamics and leading segments.

By Technology

The technology landscape is segmented into traditional and rapid methods, with rapid technologies increasingly dominating due to their speed and accuracy.

Table: Market Segmentation by Technology and Method

| Segmentation Basis | Key Segment | Leading Technology/System | Market Share / Reason for Dominance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology [8] | Molecular & Rapid Technologies | MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry | Dominated in 2024 due to high speed, low operational cost, and ease of integration into lab workflows [8]. |

| Technology [8] | Molecular & Rapid Technologies | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Expected fastest growth; can uncover mixed infections and detect unknown strains [8]. |

| Technology [10] | Molecular & Rapid Technologies | PCR | Held a 32.2% share in 2025; valued for high sensitivity, specificity, and broad applicability [10]. |

| Method [10] | Phenotypic Methods | Culture-based, Gram staining, Biochemical tests (e.g., API strips, VITEK) | Held a dominant 35.2% share in 2025; cost-effective, accessible, and used for validation [10]. |

By Application and End-User

Different industries utilize bacterial identification tools to meet specific needs, from clinical diagnostics to quality control.

Table: Key Application Areas and End-Users

| Application Area | Key Drivers and Uses | Growth Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Diagnostics [8] [9] | Rising patient volumes, need for infection management, and combating AMR. | The largest application segment, led by hospitals and clinics [8] [9]. |

| Food & Beverage Testing [7] [8] | Preventing contamination, complying with safety regulations, and extending product shelf-life. | Expected to be the fastest-growing application segment [8]. |

| Pharmaceutical & Cosmetics [7] | Ensuring microbial safety and quality control of products like biologics and personal care items. | Adoption of rapid testing is increasing for stringent microbial control [7]. |

| Environmental Monitoring [9] | Monitoring water, soil, and air for microbial contamination. | A growing application area for detection kits beyond healthcare [9]. |

By Product Type

The market is also divided by the type of product sold. The instruments segment (e.g., mass spectrometers, PCR systems) accounted for the largest share (45.2%) in 2025, driven by technological advancements and the need for diagnostic accuracy [10]. However, the consumables segment (e.g., reagents, assay kits) also held a dominant position due to their essential, recurring nature in daily lab operations [8]. The software & services segment is projected to grow the fastest as labs increasingly rely on digital platforms for data management and analysis [8].

Key Players and Competitive Landscape

The bacterial identification market features a mix of established multinational corporations and emerging specialized companies. Competition is intense, with players focusing on innovation, partnerships, and mergers and acquisitions to expand their market presence [11] [13].

Table: Key Market Players and Recent Strategic Developments

| Company | Representative Product/Service | Recent Strategic Developments |

|---|---|---|

| bioMérieux | VITEK systems for ID/AST | Received FDA clearance for VITEK COMPACT PRO in March 2025 [8] [10]. |

| Thermo Fisher Scientific | MicroSEQ PCR and Sequencing Kits | Offers kits and libraries for 16S rDNA and fungal identification [14]. |

| Charles River Laboratories | Accugenix NGS Services | Launched Accugenix Next-Generation Sequencing for bacterial and fungal ID in 2023 [8] [10]. |

| QIAGEN | Microbiome WGS SeqSets | Introduced a complete workflow for microbiome research in 2023 [8]. |

| Bruker Corporation | MALDI Biotyper systems | Unveiled advanced fungal and mycobacteria detection solutions in 2023 [10]. |

| Other Notable Players | Various detection kits and instruments | Minerva Biolabs, Charm Sciences, Creative Diagnostics, Sartorius AG [11] [9]. |

Growth Catalysts and Future Outlook

The market's future trajectory will be shaped by several powerful catalysts and emerging trends.

Primary Growth Catalysts

- Technological Advancements: The development of portable, automated, and rapid testing solutions is making advanced diagnostics accessible beyond central laboratories [7] [15]. For instance, AI-powered platforms can now identify bacterial species directly from clinical samples in as little as 5 hours, a process that traditionally took days [8].

- Rising Healthcare Investment: Governments, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, are investing heavily in upgrading healthcare infrastructure, which includes expanding laboratory capabilities and access to diagnostic tools [9] [10].

- Expanding Point-of-Care (POC) Testing: The trend towards decentralized testing is creating significant demand for portable, user-friendly bacteria detection kits that can deliver immediate results in clinics or remote locations [9].

Emerging Trends

- AI and Predictive Analytics: Integration of AI and machine learning is revolutionizing the market by enhancing the speed and accuracy of pathogen detection, predicting resistance patterns, and enabling real-time outbreak surveillance [7] [8].

- Multiplexing and Multi-Omics: There is a growing focus on developing tests that can detect multiple bacterial pathogens simultaneously (multiplexing) and on combining various testing modalities, such as genomics and metagenomics, for a more comprehensive analysis [7] [15].

- Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) and At-Home Testing: Growing consumer interest in personal health monitoring is fueling the development of at-home microbiome and bacteria testing kits, opening a new distribution channel for the market [12].

Experimental Data and Protocol Comparison

A critical function of commercial kits is the accurate identification of unknown bacterial isolates in a research setting. Below is a detailed comparison of two common genotypic methods.

Table: Comparison of Experimental Protocols for Bacterial ID

| Parameter | 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing (Sanger) [14] | MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry [8] |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Sequencing of the conserved 16S ribosomal RNA gene and comparison to a database. | Analysis of unique protein profiles (primarily ribosomal proteins) from whole cells. |

| Target Molecule | DNA (16S rRNA gene). | Proteins and peptides. |

| Workflow Duration | ~5 hours for sequencing reaction (plus culture time) [14]. | As little as 15 minutes to a few hours [8]. |

| Key Experimental Steps | 1. DNA extraction.2. PCR amplification of 16S gene.3. Purification of PCR product.4. Sequencing reaction.5. Capillary electrophoresis.6. Data analysis against library (e.g., MicroSEQ). | 1. Prepare a thin layer of bacterial colony on target plate.2. Overlay with matrix solution.3. Dry and insert into spectrometer.4. Irradiate with laser to ionize samples.5. Measure time-of-flight of ions.6. Compare resulting spectrum to reference database. |

| Discriminatory Power | Can often discriminate to the species level; full gene (1500 bp) provides higher resolution than partial (500 bp) [14]. | Excellent for species-level identification; may struggle with very closely related species [8]. |

| Throughput | Lower throughput (one to a few samples per run). | Very high throughput (hundreds of samples per run). |

Research Reagent Solutions for 16S rRNA Sequencing

For a typical 16S rRNA sequencing experiment, the following key reagents are required:

- Lysis Buffers and Enzymes: For mechanical or enzymatic breakdown of the bacterial cell wall to release genomic DNA.

- PCR Master Mix: A pre-mixed solution containing a thermostable DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgClâ‚‚, and reaction buffers optimized for amplifying the 16S rRNA gene [14].

- Specific Primers: Oligonucleotides designed to bind to the conserved regions of the 16S rRNA gene, allowing amplification of the variable regions used for identification [14].

- Purification Kits: For cleaning up the PCR product prior to sequencing to remove excess primers, dNTPs, and enzymes.

- BigDye Terminators or Similar: Fluorescently labeled dideoxynucleotides used in the Sanger sequencing reaction to terminate DNA strand elongation [14].

- Sequence Analysis Software & Database: Bioinformatics tools and curated libraries (e.g., MicroSEQ library with thousands of entries) to compare the obtained sequence for identification [14].

Visual Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for the two primary identification methods discussed, providing a clear visual comparison of their processes.

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Workflow

MALDI-TOF MS Identification Workflow

The rapid evolution of microbial identification technologies is fundamentally transforming the landscape of clinical and research microbiology. The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI), point-of-care (POC) testing, and multiplex assays represents a paradigm shift, offering unprecedented capabilities for identifying unknown bacterial pathogens and combating antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This guide provides an objective comparison of current commercial technologies, evaluating their performance, applications, and limitations within the context of unidentified bacteria research. As AMR continues to threaten global health—projected to claim millions of lives—these emerging tools offer promising avenues for accelerating diagnosis, streamlining therapeutic discovery, and improving patient outcomes [16]. We examine these technologies through the lens of experimental data, providing researchers with a practical framework for selecting appropriate methodologies for their specific investigative needs.

Technology Performance Comparison

The following tables provide a quantitative and qualitative comparison of the primary technology platforms used in modern bacterial identification and analysis.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Bacterial Identification Technology Platforms

| Technology Platform | Key Functionality | Example Commercial Kits/Systems | Typical Turnaround Time | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Driven Discovery Platforms | De novo design & screening of antimicrobial molecules; mines genomic data for novel peptides | Custom algorithms (e.g., from de la Fuente Lab, Stokes Lab) | Weeks (for in silico candidate identification) | Vastly expands searchable chemical space; can design "new-to-nature" antibiotics [16] | Candidates may be difficult to synthesize; requires extensive validation; quality dependent on training data [16] [17] |

| Multiplex Molecular POC Panels | Simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens & antibiotic resistance genes from clinical samples | BioFire FilmArray Panels (BCID, PN plus, ME) [18] [19] [20] | ~1 hour [18] [20] | Rapid results directly impact patient management; high overall agreement (>95%) with SOC [18] | Limited to pre-defined panel targets; may miss novel resistance mechanisms or pathogens not on the panel |

| Rapid Carbapenemase Detection Kits | Detection of genes encoding clinically relevant carbapenemases from bacterial isolates | Check-Direct CPE, eazyplex SuperBug, Xpert Carba-R [21] | < 4 hours | High reliability for major carbapenemase families (KPC, NDM, VIM, OXA-48); fit into local workflows [21] | Variable coverage of OXA-48-like variants and IMP subgroups; requires pure bacterial isolates [21] |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data of Multiplex POC Testing vs. Standard Methods

| Performance Metric | BioFire FilmArray (POC) | Standard of Care Microbiology Testing (SOCMT) | Notes & Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Percent Agreement | 95.8% | (Reference) | Compared to SOCMT for bloodstream, respiratory, and CNS infections in a PICU study (n=111 samples) [18] |

| Positive Percent Agreement (PPA) | 100% | (Reference) | All phenotypically confirmed resistant isolates had corresponding resistance genes detected by FilmArray [18] |

| Negative Percent Agreement (NPA) | 95.6% | (Reference) | Same PICU study context [18] |

| Turnaround Time (TAT) | 1 - 1.5 hours [18] [20] | 48 - 72 hours [18] | Statistically significant reduction (p ≤ 0.001), enabling faster clinical decision-making [18] |

| Pathogen Detection Yield (BAL samples) | 45 pathogens | 21 pathogens | FilmArray identified significantly more pathogens in broncho-alveolar lavage samples (p ≤ 0.0001) [18] |

| Time to Antiviral Treatment | 36 hours faster | (Reference) | Associated with POC testing in adults with respiratory tract infections [20] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Technology Evaluation

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of results when working with these advanced platforms, researchers must adhere to rigorously validated experimental protocols. The following sections detail the methodologies for key applications.

Protocol for Assessing AI-Generated Antimicrobial Candidates

This protocol outlines the workflow for validating AI-generated antibiotic candidates, from in silico design to in vitro testing [16].

- Step 1: Data Curation and Model Training. Assemble a rigorously curated training dataset. For instance, measure Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) for thousands of molecules across diverse bacterial strains, holding variables like temperature, pH, and media constant to ensure comparability. Use this data to train machine learning (ML) models, either for virtual screening or generative design [16].

- Step 2: Candidate Generation.

- For Mining Algorithms: Deploy ML models to parse genomic and proteomic databases (e.g., from ancient or modern organisms) to identify sequences with predicted antimicrobial properties [16].

- For Generative Models: Use generative AI models, constrained to synthetically feasible molecular "building blocks," to design novel antibiotic candidates. One such approach generated 46 billion new, tractable compounds [16].

- Step 3: In Vitro Synthesis and Testing. Chemically synthesize the top candidate molecules. Test their antibacterial efficacy against target pathogens (e.g., Acinetobacter baumannii) in vitro by determining MICs. Further evaluate promising candidates in animal infection models (e.g., mouse skin abscess or thigh infection models) [16].

- Step 4: Mechanism of Action Studies. Investigate the candidate's mechanism of action. For antimicrobial peptides, this may involve assays to determine if the compound kills bacteria by depolarizing the cytoplasmic membrane [16].

Protocol for Evaluating Multiplex POC Panels in a Clinical Setting

This methodology describes the evaluation of a multiplex PCR system, like the BioFire FilmArray, against standard culture in a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) [18].

- Step 1: Sample Collection and Study Design. Conduct a retrospective or quasi-randomized study. Collect matched samples (e.g., blood, broncho-alveolar lavage, cerebrospinal fluid) from patients with suspected infections. For a balanced design, assign patients to intervention (POC testing) and control (standard testing) arms on alternate days [18] [20].

- Step 2: Parallel Testing. Process each sample simultaneously with both methods:

- Standard of Care Microbiology Testing (SOCMT): Culture samples using appropriate media and automated systems (e.g., BACT/ALERT). Identify isolates using standard biochemical tests and perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing per CLSI guidelines [18].

- Multiplex POC Testing: According to manufacturer instructions, load the sample (e.g., 200 μL of respiratory sample or positive blood culture fluid) into the designated FilmArray pouch and run the test on the instrument [18].

- Step 3: Data Analysis. Calculate key performance metrics:

- Overall, Positive, and Negative Percent Agreement between the POC panel and SOCMT. -- Compare turnaround times (TAT) from sample collection to result availability using statistical tests like the chi-square test [18].

- Step 4: Impact Assessment. Analyze the impact of rapid results on antimicrobial stewardship, categorizing changes in therapy (e.g., stop, de-escalate, broaden spectrum, or start antivirals) [18].

Protocol for Testing Commercial Carbapenemase Detection Kits

This protocol evaluates the performance of molecular kits for detecting carbapenemase genes from cultured bacterial isolates [21].

- Step 1: Isolate Panel Preparation. Curate a well-characterized panel of bacterial isolates (e.g., 450 Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp.) with previously defined carbapenem resistance mechanisms (e.g., KPC, NDM, VIM, OXA-48-like, IMP) and a set of carbapenemase-negative controls [21].

- Step 2: Kit Testing. Test all isolates using the commercial kits (e.g., Check-Direct CPE, eazyplex SuperBug complete A, Xpert Carba-R) strictly following the manufacturers' protocols for pure bacterial isolates [21].

- Step 3: Resolve Discrepancies. Investigate any discordant results (commercial kit vs. in-house reference method) using an in-house PCR assay followed by amplicon sequencing to definitively identify the carbapenemase allele present [21].

- Step 4: Performance Calculation. For each kit, calculate sensitivity and specificity for detecting each major carbapenemase family. Pay particular attention to the detection of variant enzymes, such as OXA-181, which may not be covered by all kit versions [21].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

The integration of these technologies into research and clinical workflows can be visualized through the following diagrams, which outline the logical sequence of steps and functional relationships.

Figure 1: A comparison of traditional microbiology workflows against emerging pathways leveraging POC multiplex PCR and AI-driven discovery.

Figure 2: Functional relationships between core technologies and their primary applications in modern microbiology.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these emerging trends relies on a foundation of specific reagents, instruments, and computational tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Emerging Technology Applications

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BioFire FilmArray Panels | Syndromic multiplex PCR testing for pathogens and resistance genes directly from samples. | Panels available for Blood Culture ID (BCID), Pneumonia (PN plus), and Meningitis/Encephalitis (ME). Detects organisms and key resistance markers (e.g., mecA, vanA/B, CTX-M, KPC) [18] [19] [20]. |

| Xpert Carba-R Kit | Rapid detection of carbapenemase genes (KPC, NDM, VIM, IMP-1, OXA-48) from bacterial isolates. |

Useful for high-throughput screening of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; limited to predefined targets [21]. |

| Curated MIC & Genomic Datasets | Training data for AI/ML models to predict or design antimicrobial compounds. | Requires standardized, biologically relevant data with variables like pH and temperature controlled for model accuracy [16]. |

| Automated Synthesis Platforms | Physical generation of AI-designed molecular candidates for in vitro validation. | "Robots the size of a microwave" that synthesize molecules from code; essential for closing the AI-design-testing loop [16]. |

| Protein Language Models (pLMs) | AI systems that predict, generate, and optimize functional protein sequences for therapeutic design. | Trained on millions of natural sequences; a powerful tool with significant dual-use biosecurity risks that require safeguards [17]. |

| Larotrectinib Sulfate | Larotrectinib Sulfate, CAS:1223405-08-0, MF:C21H24F2N6O6S, MW:526.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lascufloxacin | Lascufloxacin, CAS:848416-07-9, MF:C21H24F3N3O4, MW:439.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of AI, point-of-care testing, and multiplex assays is unequivocally reshaping the identification and study of unknown bacteria. Performance data consistently demonstrates that multiplex POC panels offer a significant advantage in speed and diagnostic yield over standard culture, directly impacting antimicrobial stewardship [18] [20]. Meanwhile, AI is breaking decades-long stagnation in antibiotic discovery by exploring vast new chemical spaces [16]. However, each technology presents constraints; POC panels are limited to predefined targets, and AI's promise is contingent on high-quality data and overcoming synthesis challenges [16] [17]. The future of microbial research lies not in using these tools in isolation, but in developing integrated frameworks where rapid diagnostic data feeds into AI-driven discovery platforms, creating a virtuous cycle of innovation to address the pressing challenge of antimicrobial resistance.

Selecting the appropriate DNA manipulation technology is a critical first step in research involving unidentified bacteria. The choice between long-read sequencing, high-throughput automation, and targeted enrichment methods directly impacts the success of genome assembly, functional characterization, and phylogenetic placement. This guide objectively compares leading commercial kits and platforms using published experimental data to help researchers align technological capabilities with specific project requirements, from outbreak investigations to comprehensive microbiome studies.

Comparative Performance of DNA Sequencing and Extraction Technologies

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for different DNA sequencing and extraction technologies based on controlled laboratory evaluations:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Sequencing and Extraction Technologies

| Technology Category | Specific Kits/Platforms Evaluated | Key Performance Metrics | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Read Sequencing | ONT Q20+ chemistry with:• Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK114)• Rapid Barcoding Kit (SQK-RBK114)• DNA Extraction: Maxwell RSC vs. Monarch HMW [22] [23] | • ≥99% raw read accuracy [23]• Assembly length variation: 0.2-38 kb differences vs. reference [23]• Highest output: LSK114/Maxwell (10.65 Gb, 1.76M reads) [23]• Higher N50: NEB HMW DNA with either library kit [23] | • Bacterial outbreak investigations [22]• Complete genome closure [23]• Plasmid and repetitive region analysis [23] |

| High-Throughput Automated Systems | PANA HM9000 Automated System with manufacturer-matched kits [24] | • Concordance rate: 100% for EBV, HCMV, RSV [24]• Precision: CV <5% (intra- & inter-assay) [24]• LoD: 10 IU/mL for EBV/HCMV DNA [24]• Linearity: ∣r∣ ≥0.98 [24] | • Large-scale clinical pathogen screening [24]• Routine nucleic acid testing in clinical labs [24] |

| Targeted NGS with Host Depletion | Custom tNGS panel + novel filtration membrane [25] | • >98% host DNA reduction [25]• 6-8 fold increase in pathogen reads [25]• Covers >330 clinically relevant pathogens [25] | • Bloodstream infections with low pathogen abundance [25]• Samples with high host DNA background [25] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Evaluation of Long-Read Sequencing for Bacterial Genomes

This protocol is adapted from the single-laboratory evaluation of ONT Q20+ chemistry for bacterial outbreak investigations [22] [23].

Sample Preparation:

- Select well-characterized bacterial strains (e.g., Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli O157:H7) from a defined collection [23].

- Culture bacteria overnight using standard laboratory media appropriate for each strain.

DNA Extraction Methods (Compared):

- Maxwell RSC Cultured Cell DNA Kit: Automated system yielding high DNA concentration but more sheared fragments [23].

- Monarch High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA Extraction Kit: Manual protocol designed to preserve long DNA fragments [23].

Library Preparation Protocols (Compared):

- Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK114): More time-consuming and labor-intensive but produces higher sequencing output [23].

- Rapid Barcoding Sequencing Kit (SQK-RBK114): Faster workflow with fewer steps but generates lower sequencing output [23].

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Utilize ONT R10.4.1 flow cells with Q20+ chemistry [23].

- Perform basecalling and assembly using appropriate bioinformatics tools (e.g., Guppy, Flye).

- Compare assembly statistics: assembly length, contig number, N50, genome completeness, and percentage of ORFs recovered against reference genomes [23].

- Conduct in silico analyses for species identification, serotyping, virulence factors, and phylogenomic clustering [22].

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Validation of Automated High-Throughput Systems

This protocol follows the CLSI-based validation framework for automated nucleic acid detection systems [24].

Sample and Reference Material Sources:

- Use clinically characterized residual samples (e.g., plasma, oropharyngeal swabs) [24].

- Include WHO International Standards and National Reference Materials at defined concentrations [24].

Concordance Rate Assessment (CLSI EP12):

- Test positive and negative clinical samples in parallel on the automated system and a reference RT-qPCR platform [24].

- Calculate positive, negative, and overall concordance rates based on binary outcomes [24].

Accuracy and Linearity Evaluation (CLSI EP09/EP06):

- Dilute WHO standards to five concentration gradients in negative plasma matrix [24].

- Perform extractions and testing in triplicate for each concentration [24].

- Compare mean detected values to theoretical concentrations for accuracy [24].

- Assess linearity by calculating the correlation coefficient (∣r∣) across the dilution series [24].

Precision Testing (CLSI EP05):

- Conduct intra-assay (within-run) and inter-assay (between-run) precision studies [24].

- Report coefficients of variation (CV) for quantitative results [24].

Limit of Detection (LoD) Determination (CLSI EP17):

- Test dilutions of standardized materials at low concentrations [24].

- Establish the lowest concentration detectable in ≥95% of replicates [24].

Stress Testing for Operational Stability:

- Perform continuous operation at full capacity for 168 hours (7 days) [24].

- Monitor system status, error rates, and output quality throughout the testing period [24].

Protocol 3: Targeted NGS with Host DNA Depletion

This protocol implements a novel filtration and tNGS approach for enhanced pathogen detection [25].

Host Cell Depletion Using Specialized Filtration:

- Process blood samples through a human cell-specific filtration membrane.

- This membrane is engineered with surface charge properties to selectively capture nucleated cells, reducing host DNA background by over 98% [25].

Pathogen Concentration and Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Recover pathogens from the filtrate via centrifugation.

- Extract nucleic acids using standard commercial kits appropriate for the target pathogens (bacterial, viral, fungal).

Targeted Library Preparation:

- Utilize a multiplex tNGS panel covering over 330 clinically relevant pathogens [25].

- The panel employs probe hybridization or multiplex PCR amplification to enrich pathogen-specific sequences [25].

Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Perform sequencing on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Analyze data using a customized bioinformatics pipeline aligned with the tNGS panel targets.

- Compare results to conventional methods like blood culture and mNGS for validation [25].

Visualizing Technology Selection Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications in Bacterial Studies

| Reagent / Kit Name | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Monarch HMW DNA Extraction Kit [23] | Extracts high molecular weight DNA with minimal fragmentation | Optimal for long-read sequencing to traverse repetitive regions and improve genome assembly [23] |

| Maxwell RSC Cultured Cell DNA Kit [23] | Automated extraction yielding high concentration DNA | Suitable for rapid processing when maximum read output is prioritized over read length [23] |

| ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK114) [23] | Prepares libraries for nanopore sequencing with high output | Ideal for projects requiring complete bacterial genomes and high consensus accuracy [22] [23] |

| ONT Rapid Barcoding Kit (SQK-RBK114) [23] | Rapid library preparation with barcoding for multiplexing | Enables faster turnaround for multiple samples with moderate output requirements [23] |

| Custom tNGS Panels [25] | Enriches sequences from specific pathogens of interest | Focuses sequencing power on predefined targets in complex samples with high host background [25] |

| Host Depletion Filtration Membranes [25] | Selectively removes human cells from clinical samples | Critical for enhancing pathogen detection in blood samples and other host-rich matrices [25] |

| WHO International Standards [24] | Provides standardized reference materials for quantification | Essential for assay validation, accuracy assessment, and cross-platform comparison [24] |

| Lazertinib | Lazertinib, CAS:1903008-80-9, MF:C30H34N8O3, MW:554.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LCB 03-0110 | LCB 03-0110|Src/DDR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor |

The optimal foundation for unidentified bacteria research depends on a careful alignment of technological capabilities with project-specific goals. Long-read sequencing with Q20+ chemistry offers unparalleled potential for complete genome assembly and accurate strain typing in outbreak investigations. High-throughput automated systems provide exceptional reproducibility and efficiency for large-scale screening applications. Targeted NGS with integrated host depletion strategies enables sensitive detection in challenging sample matrices. By selecting kits and platforms based on the comprehensive performance data and validated protocols presented in this guide, researchers can establish a robust technological foundation capable of supporting their specific research objectives in bacterial characterization and discovery.

A Practical Workflow: From Sample to Identification

The reliability of any molecular analysis in bacterial research, from pathogen detection to whole-genome sequencing, is fundamentally dependent on the initial quality and quantity of the extracted DNA. The extraction method must efficiently lyse tough bacterial cell walls, particularly resilient Gram-positive species, while simultaneously inactivating nucleases and removing contaminants that can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions [26] [27]. For researchers working with unidentified bacteria, the challenge is magnified; without a priori knowledge of the sample's Gram stain or cell wall properties, the chosen protocol must be robust enough to handle a wide spectrum of bacterial matrices. Inadequate DNA yield, purity, or integrity can lead to failed sequencing runs, inaccurate pathogen detection, and ultimately, erroneous conclusions [28].

The landscape of DNA extraction methodologies ranges from simple, inexpensive in-house protocols to sophisticated, automated commercial kits. While commercial kits offer standardized, quality-controlled reagents, their cost can be prohibitive for large-scale eco-epidemiological studies [26]. Furthermore, the optimal extraction method can vary significantly depending on the specific downstream application, whether it is PCR, metagenomic analysis, or long-read sequencing [29] [28]. This guide provides a comparative evaluation of various DNA extraction methods, supported by experimental data, to empower researchers in selecting and optimizing the ideal protocol for their work with diverse and unidentified bacterial samples.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Extraction Methods and Kits

Performance Metrics Across Commercial Kits and Simple Protocols

To objectively compare the performance of different DNA isolation approaches, researchers typically assess several key parameters: DNA yield (concentration), purity (assessed by absorbance ratios), integrity (fragment size), and, most critically, suitability for downstream applications like qPCR and sequencing. The table below synthesizes experimental findings from multiple studies evaluating various kits and methods on different bacterial samples.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of DNA Extraction Methods for Bacterial Analysis

| Method / Kit Name | Key Principle / Lysis Method | Best For / Sample Type | Reported Performance & Downstream Application Success |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Hydrolysis [26] | Chemical lysis (Ammonium hydroxide); Can be performed on intact ticks | Cost-effective qPCR: Sub-optimally stored ticks; Large-scale studies | "As good as any other method" for qPCR detection of B. burgdorferi; Low purity (A260/280 ~1.44) but amplifiable. |

| ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep (ZM) [29] [30] | Bead-beating + Silica membrane columns | High Purity DNA: Gram-negative & Gram-positive bacteria; Microbial community standards | Highest purity (A260/230 ≥2.0); Good for Nanopore sequencing and accurate microbial community representation [30]. |

| Nanobind CBB Big DNA (NB) [30] | Magnetic disk for HMW DNA | Longest Read Lengths: Nanopore sequencing; Plasmid recovery | Yielded longest raw read N50 (>8,000 bp for some species); Superior for genome assembly [30]. |

| Fire Monkey HMW-DNA (FM) [30] | Spin-column with high g-force | Genome Assembly: Gram-negative bacteria; Pathogen WGS | Outperformed in genome assembly for Gram-negative bacteria [30]. |

| Quick-DNA HMW MagBead [28] | Magnetic beads for HMW DNA | Metagenomics: Complex mock communities; Fecal/spiked matrices | Best yield of pure HMW DNA; Accurate detection of most species in a complex mock community via Nanopore [28]. |

| NucleoSpin Soil (MNS) [27] | Bead-beating + Silica membrane; Lysozyme option | Ecosystem Microbiotas: Soil, rhizosphere, invertebrate, feces; High diversity samples | Highest alpha diversity estimates; Best contribution to overall sample diversity vs. computationally assembled reference communities [27]. |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue (QBT) [26] [27] | Silica membrane spin columns | Gram-Positive Bacteria: Efficient lysis of hard-to-lyse cells | Highest extraction efficiency for Gram-positive bacteria in a mock community [27]. |

The Impact of Lysis and Purification Technology

The core differentiators among extraction methods lie in their cell lysis and DNA purification strategies, each with distinct advantages and drawbacks for bacterial analysis.

Lysis Methods: Bead-beating is highly effective for mechanically disrupting tough cell walls, including Gram-positive bacteria, and is crucial for unbiased lysis in diverse microbial communities [28] [27]. However, it can cause DNA shearing, potentially compromising the recovery of high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA. Enzymatic lysis (e.g., with lysozyme) is a gentler alternative that helps preserve DNA integrity and has been specifically shown to improve the recovery of Gram-positive bacteria [27]. Chemical lysis using detergents or alkaline solutions, like ammonium hydroxide, is simple and low-cost but may result in lower purity DNA that requires careful evaluation for downstream applications [26].

Purification Methods: Silica spin columns are widely used and effective for purifying DNA from a range of contaminants. Magnetic beads offer scalability and are easier to automate, but they carry a risk of bead carryover, which can inhibit downstream enzymes in PCR and sequencing [31]. Phenol-chloroform extraction is a traditional method that can yield high-purity, HMW DNA but involves hazardous chemicals and is less suited for high-throughput or on-site applications [28] [32].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

To ensure the selected DNA extraction method is fit for purpose, researchers should conduct validation experiments using controls and metrics relevant to their specific goals.

Protocol 1: Evaluating Extraction Efficiency Using a Mock Community

Purpose: To assess the ability of a DNA extraction method to lyse different bacterial cells without bias and recover an accurate microbial profile [28] [27].

- Sample Preparation: Obtain a commercial microbial community standard (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard) with a defined composition of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Spike this standard into a sterile matrix that mimics your sample type (e.g., synthetic fecal matter) if needed.

- DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from multiple replicates of the mock community using the methods under evaluation (e.g., Kits A, B, and C).

- Downstream Analysis: Sequence the resulting DNA extracts using a standard platform (e.g., 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing or shotgun metagenomics).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate Relative Abundances: Determine the relative abundance of each bacterial taxon in the sequenced samples.

- Compare to Expected Ratio: Compare the observed ratio of Gram-negative to Gram-positive bacteria (or the abundance of specific species) to the known ratio in the original standard. A method that deviates significantly from the expected ratio indicates a bias in lysis efficiency [27].

- Assess Community Representation: Evaluate which method recovers the highest number of expected species and most closely matches the defined community structure.

Protocol 2: Assessing DNA Suitability for Long-Read Sequencing

Purpose: To determine if the extracted DNA is of sufficient quantity, purity, and integrity for successful Nanopore sequencing and genome assembly [29] [30].

- DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from a pure culture of a target pathogen or a complex sample using the kits being compared (e.g., HMW-specific kits vs. standard kits).

- Quality Control:

- Quantity and Purity: Measure DNA concentration using fluorometry (Qubit) for accuracy. Assess purity via spectrophotometry (NanoDrop) with A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios.

- Integrity: Analyze DNA fragment size distribution using gel electrophoresis (e.g., TapeStation) to confirm the presence of HMW DNA.

- Sequencing and Assembly: Perform Nanopore sequencing on a MinION or GridION flow cell. For a pure culture, aim for a target coverage (e.g., 50x).

- Performance Metrics:

- Sequencing Statistics: Calculate raw read length N50 (a measure where 50% of the assembled sequence is contained in reads of this length or longer). Longer N50 values are indicative of better HMW DNA.

- Assembly Metrics: Evaluate the completeness and contiguity of the final assembled genome. A higher quality assembly with fewer contigs and better plasmid recovery indicates a superior extraction method for this application [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful DNA extraction relies on a suite of key reagents, each performing a critical function in the workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Extraction

| Reagent / Solution | Function in DNA Extraction |

|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer (with detergents like SDS) | Disrupts lipid membranes and releases cellular contents. |

| Proteinase K | Digests and removes contaminating proteins and nucleases. |

| Lysozyme | Enzymatically degrades the peptidoglycan layer of bacterial cell walls, critical for Gram-positive species [27]. |

| RNase A | Degrades RNA to prevent it from co-purifying with DNA and affecting quantification. |

| Binding Buffer | Creates conditions for DNA to bind to silica matrices (columns or beads). |

| Wash Buffer | Removes salts, proteins, and other impurities while leaving DNA bound. |

| Elution Buffer | A low-salt buffer or water used to release purified DNA from the silica matrix. |

| LDC4297 | LDC4297, MF:C23H28N8O, MW:432.5 g/mol |

| Lefamulin Acetate | Lefamulin Acetate - BC-3781 CAS 1350636-82-6 |

A Workflow for Selecting a DNA Extraction Method

The following diagram summarizes the key decision points for selecting an optimal DNA extraction method based on research objectives, sample type, and technical constraints.

DNA Extraction Method Selection Workflow

No single DNA extraction method is universally superior for all bacterial research scenarios. The optimal choice is a careful balance between research objectives (e.g., diagnostic qPCR vs. complete genome assembly), sample type (e.g., pure culture vs. complex microbiome), and practical constraints (e.g., throughput, cost, and automation needs) [26] [30] [27]. For research on unidentified bacteria, where sample properties are a mystery, a method validated for broad applicability—such as one that efficiently lyses both Gram-positive and Gram-negative cells and yields DNA compatible with the intended downstream application—is paramount.

Looking forward, the field of DNA extraction continues to evolve. Trends for 2025 and beyond point toward increased automation, miniaturization, and tighter integration with sequencing platforms [33]. There is a growing emphasis on developing rapid, gentle protocols that maximize the recovery of ultra-long DNA fragments to fully leverage the power of third-generation sequencing technologies. Furthermore, the development of bead-free purification technologies aims to mitigate the risk of carryover inhibition in sensitive downstream reactions [31]. By understanding the principles and performance data outlined in this guide, researchers can make informed decisions that ensure their sample preparation process provides a solid foundation for reliable and impactful scientific discovery.

Automated systems for bacterial identification (ID) and antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) are cornerstone technologies in modern clinical and research microbiology. They address the critical need for rapid, accurate results to guide patient treatment and advance scientific research, particularly in the face of rising antimicrobial resistance. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of two major systems: the VITEK 2 (bioMérieux) and the MicroScan (Beckman Coulter) platforms. The evaluation is framed within the broader context of validating commercial kits for research involving unidentified bacteria, a process that demands rigorous assessment of a system's accuracy, database comprehensiveness, and operational workflow.

These systems have evolved from manual biochemical methods, offering increased automation, reduced turnaround times, and standardized interpretation. For researchers, selecting an appropriate system depends on multiple factors, including the diversity of bacterial species in their samples, required throughput, need for susceptibility data, and the operational constraints of the laboratory environment.

VITEK 2 System

The VITEK 2 is a fully automated system that performs bacterial ID and AST using compact, sealed test cards containing 64 microwells. The system utilizes Advanced Colorimetry and kinetic fluorescence measurements to monitor metabolic changes every 15 minutes, enabling rapid results [34] [35]. Its software includes an ADVANCED EXPERT SYSTEM (AES) that analyzes Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) patterns to detect resistance mechanisms and phenotypes, providing an additional layer of result validation [35].

MicroScan System

The MicroScan system offers both conventional overnight panels and rapid fluorescent panels for ID and AST. The panels evaluated here, such as the Dried Overnight Positive ID Type 3 (PID3) for Gram-positive organisms and Dried Overnight Negative ID Type 2 (NID2) for Gram-negative organisms, are designed for manual inoculation and visual or automated reading. A key feature for low-resource settings is the availability of a customized MSFNPID1 panel that consolidates Gram-negative and Gram-positive test wells on a single panel [36].

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize experimental data from independent studies evaluating the identification accuracy and susceptibility testing performance of both systems.

Table 1: Comparative Identification Accuracy for Gram-Positive Cocci

| Bacterial Species | VITEK 2 (% Correctly Identified) | MicroScan (% Correctly Identified) |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | 99% (99/100) [34] | Data not available in search |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 90% (45/50) [34] | Data not available in search |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 92.7% (51/55) [34] | Data not available in search |

| Enterococcus faecium | 71.4% (20/28) [34] | Data not available in search |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 96.9% (64/66) [34] | Data not available in search |

| Overall Gram-positive isolates | 91.4% (351/384) [34] | 85.9% (110/128) [36] |

Table 2: Comparative Identification Accuracy for Gram-Negative Rods

| Bacterial Group/Species | VITEK 2 (% Correctly Identified) | MicroScan (% Correctly Identified) |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 91.6% (citation:5] | Data not available in search |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 76% (19/25) [37] | Data not available in search |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 100% (27/27) [37] | Data not available in search |

| Overall Gram-negative isolates | Data not available in search | 94.6% (185/195) [36] |

Table 3: Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) Performance

| Performance Metric | VITEK 2 (for Gram-positive cocci) | MicroScan (Direct Inoculation from Blood Culture) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Categorical Agreement | 96% [34] | 92.7% (GPC), 99.5% (Enterobacteria) [38] |

| Very Major Errors | 0.82% [34] | 0.04% (GPC) [38] |

| Major Errors | 0.17% [34] | 0.7% (GPC) [38] |

| Minor Errors | 2.7% [34] | Data not available in search |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The experimental data cited in this guide were generated using standardized methodologies crucial for ensuring reproducible and comparable results. The following protocols detail the key procedures used in the evaluation studies.

Bacterial Strain Selection and Preparation

- Strain Collection: Studies used large collections of clinical isolates from hospitalized patients, ensuring relevance to real-world scenarios. For instance, one VITEK 2 evaluation used 384 clinical isolates of Gram-positive cocci, including Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Enterococcus spp., and Streptococcus species [34]. The MicroScan study utilized 367 clinical isolates from low-resource settings, encompassing a wide range of Gram-negative and Gram-positive pathogens [36].

- Storage and Subculturing: Isolates were typically stored at -70°C in broth-glycerol mixtures. Prior to testing, they were subcultured twice on appropriate solid media like Columbia agar with 5% sheep blood and grown overnight at 35°C to ensure purity and viability [34].