From Petri Dishes to Digital PCR: The Evolving Battlefield of Pathogen Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional culture-based methods and modern molecular techniques for pathogen discovery and diagnostics.

From Petri Dishes to Digital PCR: The Evolving Battlefield of Pathogen Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional culture-based methods and modern molecular techniques for pathogen discovery and diagnostics. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, practical applications, and performance validation of these technologies. The content synthesizes recent evidence to illustrate a paradigm shift in clinical microbiology, highlighting how molecular methods like mNGS and ddPCR offer superior speed, sensitivity, and the ability to detect uncultivable pathogens, while also addressing their challenges and the enduring role of culture for antibiotic susceptibility testing.

The Microbiological Bedrock: Understanding Culture-Based Methods and Their Limitations

For over two centuries, traditional microbial culture has served as the foundational pillar of clinical microbiology, providing the critical link between microbial presence and infectious disease [1]. Despite the rapid ascent of molecular diagnostic techniques, culture methods remain the uncontested reference standard for a wide range of pathogens, offering unparalleled benefits for phenotypic characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility testing [1] [2]. The basic principle of microbial culture is to provide a suitable environment—including nutrients, temperature, and atmosphere—that supports the growth and multiplication of microorganisms from a clinical sample, allowing for their visualization, identification, and further analysis [1].

This guide objectively examines the position of traditional culture methodologies within the modern diagnostic and research landscape, directly comparing its performance against nucleic acid amplification techniques and next-generation sequencing. We present quantitative data on detection sensitivity, turnaround time, and clinical utility to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a clear framework for selecting appropriate pathogen discovery pathways.

Core Principles and Workflow of Traditional Culture

The workflow of traditional microbial culture is a systematic, multi-stage process designed to isolate, purify, and identify pathogens from complex clinical specimens. The foundational concepts of this methodology were established by pioneers like Pasteur and Koch, who developed the initial criteria for linking specific microbes to diseases [1]. The process leverages the ability to grow microorganisms in controlled laboratory conditions, either on inanimate media like agar plates for bacteria and fungi, or in animate systems like cell cultures for viruses and obligate intracellular pathogens [1].

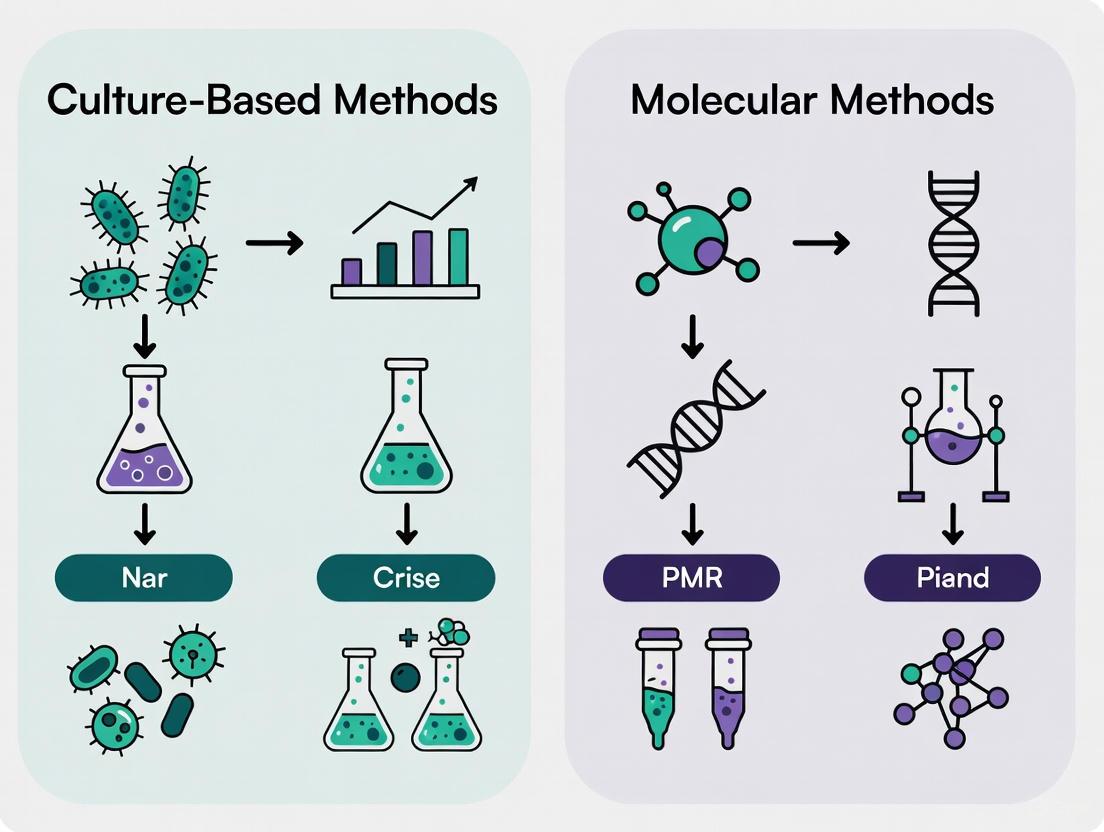

Graphical representation of the multi-stage traditional culture workflow, from specimen processing to final reporting.

Key Methodological Steps

- Specimen Processing and Inoculation: Clinical samples are applied to solid or liquid culture media using tools like sterile loops or automated instruments (e.g., WASP, PREVI Isola) [3]. Automated systems demonstrate high agreement with manual methods (94.4-100%) and can provide better isolation quality, particularly for polymicrobial specimens [3].

- Incubation and Colony Isolation: Inoculated media are incubated at controlled temperatures for hours to days. Microbial growth appears as visible colonies on solid media or turbidity in liquid broths, which are then isolated for pure culture [1].

- Identification and Characterization: Colony morphology, Gram staining, and biochemical profiling form the basis for taxonomic identification. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) has revolutionized this step by enabling rapid, sensitive identification based on protein mass fingerprints [4].

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST): Pure isolates are subjected to phenotypic AST using disk diffusion or broth microdilution to determine minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), which are crucial for guiding effective antimicrobial therapy [5] [2].

Performance Comparison: Culture Versus Molecular Methods

The diagnostic landscape for infectious diseases has been transformed by molecular techniques that offer rapid turnaround times. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent comparative studies across different infection types and patient populations.

Table 1: Comparative performance of traditional culture versus molecular diagnostic methods for pathogen detection.

| Infection Type / Setting | Methodology | Detection Rate | Turnaround Time | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Meningitis [6] | Microbial Culture | 3% (10/400) | 48-72 hours | Enables AST; Gold standard | Low sensitivity |

| Real-time PCR | 10% (38/400) | 2-5 hours | High sensitivity; Rapid | No phenotypic AST | |

| Community-Acquired Pneumonia (HIV+) [5] | Sputum Culture | <25% | 48-72 hours | Guides targeted therapy | Low diagnostic yield |

| FilmArray Pneumonia Panel | 83.2% | ~2 hours | Detects viruses & resistance genes | Cannot differentiate colonization from infection | |

| Bloodstream Infection [7] | Blood Culture | 13.1% (13/99) | 5-7 days | Comprehensive live pathogen recovery | Lengthy process |

| mNGS | 65.7% (65/99) | 24-48 hours | Broad, culture-independent detection | High cost; Complex interpretation |

Analysis of Comparative Data

The data reveal a consistent pattern across clinical syndromes: molecular methods demonstrate superior detection sensitivity and dramatically shorter turnaround times compared to traditional culture. In bacterial meningitis, PCR detected nearly four times as many cases as culture (10% vs. 3%) [6]. Similarly, in HIV-positive patients with pneumonia, a multiplex PCR panel identified a potential bacterial etiology in over 83% of cases, compared to <25% for sputum culture [5].

However, culture maintains its critical role in antimicrobial stewardship. As noted in a recent evaluation, "Traditional methods were noted for their precision in determining minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), crucial for guiding effective antimicrobial therapy" [2]. This phenotypic information is particularly vital in an era of rising multidrug-resistant organisms, where molecular detection of resistance genes does not always correlate with phenotypic resistance patterns.

Detailed Experimental Protocols in Comparative Studies

Objective: To compare pathogen detection consistency between metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) and blood culture in patients with suspected bloodstream infection.

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Blood samples for both tests were drawn on the same day from patients with fever (>38.5°C), chills, or antibiotic use >3 days.

- Blood Culture Protocol: Two sets of aerobic and anaerobic blood samples (5-10 mL each) were collected aseptically from different venipuncture sites. Cultures were incubated using the BACTECFX automated system for 5-7 days. Bacterial identification was performed using the VITEK MS system.

- mNGS Protocol: 6-8 mL of blood was collected and transported on dry ice. DNA was extracted using commercial kits (QIAamp DNA Micro Kit or QIAamp Microbiome DNA Kit). Libraries were prepared and sequenced on Illumina platforms (Nextseq 550 or NextSeq CN500). Bioinformatic analysis involved removing human sequences and aligning non-human reads to microbial databases.

- Positive Criteria: For mNGS, a microbe was reported positive if its coverage ranked in the top 10 of its kind AND was absent in negative controls, or if the RPMsample/RPMNTC ratio was >10.

Objective: To compare the diagnostic yield of the BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel with conventional culture in hospitalized HIV-positive patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

Methodology:

- Sample Type: Sputum samples from hospitalized patients with HIV.

- Culture Method: Standard sputum culture protocols were followed with incubation for 24-48 hours. Isolates were identified using standard microbiological techniques.

- Molecular Method: The BioFire FilmArray Pneumonia Panel was used according to manufacturer's instructions. This multiplex PCR system detects genes of >20 bacterial pathogens and several resistance genes in approximately 2 hours.

- Outcome Measures: Primary outcomes were detection rates for bacterial pathogens and resistance markers. Secondary outcomes included identification of viral pathogens and mixed infections.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful implementation of traditional culture methods requires specific reagents and instruments optimized for different specimen types and microbial targets.

Table 2: Key research reagents and instruments for traditional microbial culture workflows.

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Agar plates, Broth media | Support microbial growth | Various formulations (e.g., blood agar, MacConkey) for selectivity |

| Automated Inoculation Systems | WASP (Copan), PREVI Isola (bioMérieux) | Standardized specimen plating | Reduces variability; Improves isolation quality [3] |

| Automated Blood Culture Systems | BACTECFX (Becton, Dickinson) | Continuous monitoring of liquid cultures | Detects microbial growth through gas production |

| Identification Systems | VITEK MS (BioMérieux) | MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry | Rapid identification based on protein fingerprints [4] |

| High-Throughput Screening | MilliDrop AzurEvo | Microbial phenotyping in droplets | Enables study of micro-communities; Monitors growth parameters [8] |

The Integrated Future of Pathogen Discovery

The reign of traditional microbial culture as the sole gold standard is evolving toward a collaborative diagnostic model where culture and molecular methods function synergistically. While molecular techniques excel in rapid detection and identification, culture remains indispensable for phenotypic characterization, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and providing viable isolates for further research [1] [2].

Future advancements will likely focus on integrating these methodologies to leverage their complementary strengths. As noted in a recent perspective, "Revolutionary changes are on the way in clinical microbiology with the application of '-omic' techniques," including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic selection of methodology should be guided by the clinical or research question—opting for molecular speed when rapid identification is critical, while relying on culture's phenotypic capabilities when therapeutic guidance requires live isolates for comprehensive susceptibility testing.

The enduring reliance on cultivation-based methods in clinical microbiology presents a significant bottleneck for pathogen discovery and diagnostics. A substantial proportion of bacterial species, including fastidious organisms and those in a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, resist growth on standard laboratory media, leading to false-negative results and obscuring the true complexity of microbial infections. This guide objectively compares the performance of traditional culture techniques with modern molecular methods, leveraging experimental data to illustrate their respective capabilities in detecting and identifying pathogens. The analysis underscores a paradigm shift in clinical microbiology towards molecular techniques that circumvent the inherent constraints of culturability, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy and enabling more informed therapeutic interventions.

For over a century, the culture of microorganisms has been the cornerstone of clinical microbiology. However, the longstanding reliance on this method exists in stark contrast to the reality that the majority of the microbial world resists cultivation in the laboratory [9]. It is estimated that approximately 99% of environmental bacteria and around a third of oral bacteria remain uncultivated [10]. This "Great Plate Count anomaly," the discrepancy between microscopic cell counts and viable colony counts, highlights a fundamental limitation in our traditional approach to microbial diagnostics [10].

The challenges are twofold. First, fastidious organisms are those with complex and particular nutritional requirements, making them difficult to culture because it is difficult to accurately simulate their natural milieu in a culture medium [11]. Examples include Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Treponema pallidum [11]. Second, many bacteria, including major human pathogens, can enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state under stress [12]. In this state, cells are metabolically active and viable, but cannot form colonies on conventional media routinely used for their detection, posing a significant threat to public health, food safety, and infectious disease management [12] [13]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of culture and molecular methods for pathogen discovery, framing them within the broader thesis that molecular techniques are essential for illuminating the vast, uncultivated microbial dark matter.

Defining the Challenge: Fastidious and VBNC Pathogens

Fastidious Organisms

A fastidious organism is defined by its complex nutritional requirements, meaning it will only grow when specific nutrients are present in its culture medium [11]. In practical terms, a fastidious microorganism is one that is "difficult to culture, by any method yet tried" [11]. The significance of fastidiousness is that a negative culture result could be a false negative; the organism's absence from culture does not prove its absence from the patient sample [11]. Many zoonotic and vector-transmitted bacteria are strongly adapted to the infected host, hindering pathogen cultivation and identification. These include obligate intracellular pathogens like Anaplasma spp., Bartonella spp., and Rickettsia spp., which require the intracellular compartment of eukaryotic host cells to replicate [14].

The Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) State

The VBNC state is a unique survival strategy adopted by many bacteria in response to adverse environmental conditions, such as temperature fluctuations, nutrient deprivation, and exposure to biocides [12] [13]. In this state, bacteria maintain metabolic activity and viability but are unable to proliferate on standard laboratory media, leading to an underestimation of their population density [12]. Cells in the VBNC state are distinct from dead cells; they preserve cellular integrity, retain genomic DNA, and exhibit metabolic activity [15]. A critical feature of many VBNC pathogens is that they can retain their virulence and, upon encountering favorable conditions, can resuscitate back to a culturable, infectious state [12]. This has been demonstrated for pathogens like Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli O157:H7, making them a concealed threat in water and food systems [12] [13].

Methodological Comparison: Culture vs. Molecular Diagnostics

Classical Culture-Based Diagnostics

Culture-based methods rely on growing microorganisms on or in nutrient-rich media (agar plates, liquid broths) under controlled conditions. For some fastidious organisms, this requires specialized media, specific atmospheric conditions (e.g., elevated CO2), or even eukaryotic host cells [14]. The process typically involves the following steps, which can take several days to weeks for slow-growing organisms:

- Sample Inoculation: The clinical specimen is plated onto solid and/or inoculated into liquid media.

- Incubation: Media are incubated under conditions designed to support the growth of suspected pathogens.

- Colony Isolation and Purification: Visible colonies are subcultured to obtain pure isolates.

- Identification: Isolates are identified based on morphological, biochemical, and sometimes antigenic properties.

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST): The pure isolate is tested against antibiotics to guide therapy.

Table 1: Limitations of Culture-Based Methods for Pathogen Detection

| Limitation | Impact on Diagnostic Outcome |

|---|---|

| Inability to culture VBNC cells | False-negative results; underestimation of pathogen load and risk [12] [13]. |

| Unmet growth requirements of fastidious organisms | False-negative results; failure to identify the causative agent [14] [11]. |

| Long turnaround time (days to weeks) | Delays in targeted therapeutic intervention, especially critical for slow-growing bacteria [14]. |

| Prior antibiotic exposure | Suppression of bacterial growth, leading to false-negative cultures [16]. |

| Difficulty in polymicrobial community analysis | Overgrowth by fast-growing species can mask the presence of slow-growing or fastidious pathogens [17]. |

Molecular (Culture-Independent) Diagnostics

Molecular methods detect microorganisms by identifying their genetic material (DNA or RNA), bypassing the need for cultivation. These techniques have emerged as powerful alternatives that overcome the constraints of culturability.

- Broad-Range PCR and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing: This method uses polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers that target conserved regions of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene, amplifying the variable regions in between. The amplified product is then sequenced and compared to large databases for identification [9] [17]. This is particularly useful for identifying bacteria that are difficult to characterize biochemically.

- Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS): This is a comprehensive approach that involves sequencing all the nucleic acids in a sample. After bioinformatic analysis to filter out human sequences, the remaining sequences are aligned against microbial databases to identify pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites [7]. mNGS does not require prior knowledge of the potential pathogen.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): This method uses PCR to detect and simultaneously quantify a specific pathogen by targeting a unique gene sequence. It is rapid and highly sensitive [16] [13].

Table 2: Key Advantages of Molecular Methods for Pathogen Detection

| Advantage | Diagnostic Impact |

|---|---|

| Does not require viability or culturability | Detects VBNC cells, dead cells, and fastidious organisms [12] [17]. |

| High sensitivity and specificity | Can detect low-abundance pathogens and provides precise identification [17] [7]. |

| Rapid turnaround time (hours to a few days) | Enables faster clinical decision-making and antibiotic stewardship [16] [7]. |

| Comprehensive profiling of polymicrobial infections | Reveals the full complexity of microbial communities in chronic wounds or biofilms [17]. |

| Detection of non-bacterial pathogens | A single test (e.g., mNGS) can identify viruses, fungi, and parasites from one sample [7]. |

Comparative Experimental Data: A Quantitative Analysis

Multiple studies have directly compared the output of culture and molecular methods, providing quantitative evidence of the limitations of traditional culturing.

Detection in Chronic Wounds

A retrospective study of 168 chronic wound samples compared aerobic bacterial culture with 16S rDNA sequencing [17]. The results demonstrated a dramatic increase in microbial diversity detected by molecular methods.

Table 3: Culture vs. Molecular Identification in Chronic Wounds [17]

| Method | Number of Bacterial Taxa Identified | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Culture | 17 | The majority of bacteria found by culture were also identified by molecular testing. |

| 16S rDNA Sequencing | 338 | The majority of bacteria (over 300 taxa) identified molecularly were not recovered by culture. |

The study concluded that molecular testing revealed an order of magnitude greater number of bacterial species than culture, fundamentally changing the understanding of the microbiota in chronic wound infections [17].

Detection in Bloodstream Infections

A 2023 study of 99 patients with suspected bloodstream infection compared pathogen detection using mNGS and blood culture [7]. The findings further underscore the sensitivity gap between the two methods.

Table 4: mNGS vs. Blood Culture in Suspected Bloodstream Infections [7]

| Method | Positive Detection Rate | Concordance for Bacteria/Fungi |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Culture | 13.13% (13/99 patients) | 12.00% |

| Blood mNGS | 65.66% (65/99 patients) |

The detection rate for pathogenic microorganisms by mNGS was significantly higher than that by blood culture (P < 0.001). Notably, mNGS identified viruses in 22 patients, a class of pathogen that blood culture cannot detect. The very low concordance rate highlights that the two methods often provide different diagnostic information [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical reference, this section outlines the core methodologies cited in the comparative data.

This protocol is used for bacterial identification and community profiling in complex samples like chronic wound tissue.

DNA Extraction:

- Tissue samples are centrifuged and suspended in RLT buffer (Qiagen) with β-mercaptoethanol.

- Mechanical lysis is performed using a TissueLyser (Qiagen) with steel and glass beads.

- DNA is purified from the supernatant using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's tissue protocol.

- DNA is eluted in water and diluted to a standard concentration (e.g., 20 ng/μL).

16S rRNA Gene Amplification:

- Amplify the ~500 bp region of the 16S rRNA gene using modified universal bacterial primers (28F and 519R).

- Primer sets are modified with linker sequences and sample-specific barcodes to enable multiplexed sequencing on platforms like the FLX-Titanium (Roche).

- PCR is performed using a hot-start master mix (e.g., HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix Kit, QIAGEN) with 35 amplification cycles.

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Amplified products are pooled and subjected to pyrosequencing.

- Post-sequencing, raw data is processed to remove low-quality reads, adapter sequences, and primers.

- Filtered sequences are clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) based on sequence similarity.

- OTUs are classified by comparison to a curated 16S rRNA database (e.g., Greengenes, SILVA) to assign taxonomic identities.

This protocol is used for the untargeted detection of pathogens in blood samples.

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction:

- Collect 6-8 mL of blood in EDTA tubes.

- Extract cell-free DNA from plasma using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Micro Kit, QIAGEN).

- For comprehensive analysis, extract total DNA from blood samples using a dedicated microbiome DNA kit (e.g., QIAamp Microbiome DNA Kit).

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Construct DNA libraries using a kit designed for low-input or ultra-low input samples (e.g., QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit or Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit).

- Assess library quality using an instrument like the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer.

- Sequence the libraries on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina Nextseq 550 or CN500).

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Remove low-quality reads, adapter contamination, and duplicated reads.

- Align reads to the human reference genome (hg38 or hg19) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) and subtract them from subsequent analysis.

- The remaining non-host reads are aligned to comprehensive microbial genome databases (e.g., from NCBI).

- Establish positive detection criteria based on statistical thresholds, such as the ratio of reads per million (RPM) in the sample versus a negative control (RPMsample/RPMNTC > 10).

Visualization of Method Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between culture-based and molecular diagnostic pathways, highlighting the key reasons for their divergent outcomes.

Diagram 1: A comparative workflow of culture-based versus molecular pathogen detection pathways. The culture pathway is susceptible to several constraints that lead to false-negative results, whereas the molecular pathway bypasses the need for microbial growth.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and kits used in the molecular methods discussed, providing a resource for experimental design.

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Molecular Pathogen Detection

| Reagent / Kit | Function in Experimental Protocol | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Mini Kit / Micro Kit | Extraction of high-quality genomic DNA from various sample types, including tissues and body fluids. | DNA extraction from chronic wound tissue [17] and plasma [7]. |

| QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries from very low quantities of input DNA, critical for samples with low microbial biomass. | mNGS library prep from blood samples [7]. |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Rapid preparation of sequenced-ready libraries from genomic DNA using a tagmentation-based approach. | mNGS library preparation [7]. |

| HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix Kit | A pre-mixed solution for PCR, containing a hot-start DNA polymerase for high specificity and yield in amplification. | Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene from wound samples [17]. |

| Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) | A bioinformatics software tool for aligning sequencing reads to large reference genomes, such as the human genome. | Filtering out human host sequences in mNGS data analysis [7]. |

| Microbial Genome Databases (NCBI) | Curated public databases of microbial reference sequences used for taxonomic classification of sequencing reads. | Identification of pathogens from non-host mNGS or 16S sequencing reads [17] [7]. |

| 2,4-Dimethylphenyl 2-ethoxybenzoate | 2,4-Dimethylphenyl 2-Ethoxybenzoate | Research Compound | High-purity 2,4-Dimethylphenyl 2-Ethoxybenzoate for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. |

| 1-(3,4,5-Triethoxybenzoyl)pyrrolidine | 1-(3,4,5-Triethoxybenzoyl)pyrrolidine|High-Quality|RUO | 1-(3,4,5-Triethoxybenzoyl)pyrrolidine is a high-purity chemical building block for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The comparative data and experimental protocols presented in this guide objectively demonstrate the inherent constraints of culture-based methods, primarily their inability to detect VBNC cells and fastidious organisms. Molecular techniques like 16S rDNA sequencing and mNGS provide a more sensitive, comprehensive, and faster approach to pathogen discovery. They have fundamentally expanded our understanding of infectious diseases, revealing complex polymicrobial communities where culture once suggested simplicity or sterility. While culture remains important for obtaining isolates for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, the future of pathogen discovery and diagnostics is inextricably linked to the continued development and integration of these powerful molecular tools into clinical and research practice.

The Impact of Empirical Antibiotics on Culture Sensitivity and Diagnostic Delays

The initiation of empirical antibiotic therapy is a cornerstone of managing severe bacterial infections, particularly in critical care settings where delays in treatment are associated with significantly increased mortality [18] [19]. This life-saving intervention, however, presents a fundamental diagnostic dilemma: the very antibiotics administered to combat infections simultaneously compromise the sensitivity of gold-standard culture-based diagnostics and contribute substantially to treatment delays. This conflict creates a negative feedback loop that perpetuates broad-spectrum antibiotic use and complicates antimicrobial stewardship efforts.

Empirical therapy refers to the administration of antibiotics before a specific pathogen is identified, guided by clinical presentation and local resistance patterns [19]. While this approach is often necessary, it exerts selective pressure on microorganisms and can induce physiological changes that render them undetectable by conventional culture methods. The resulting diagnostic uncertainty frequently leads to prolonged empirical treatment, increased healthcare costs, and the acceleration of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [18] [20]. This review examines the impact of empirical antibiotics on diagnostic efficacy, compares traditional and novel pathogen discovery methodologies, and explores how technological innovations are reshaping the diagnostic landscape to overcome these challenges.

The Diagnostic Challenge of Empirical Antibiotic Therapy

Clinical Rationale and Consequences of Empirical Treatment

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines recommend initiating empiric antibiotic therapy within one hour for patients with a high likelihood of sepsis, reflecting the time-sensitive nature of severe infection management [19]. International cohort studies demonstrate that approximately 75% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients with hospital-associated bloodstream infections receive empiric antibiotic therapy, with combination therapy employed in roughly half of these cases [19]. The decision to use empiric combination therapy is influenced by several patient-specific and institutional factors, including:

- Immune deficiency (OR 1.35)

- High SOFA scores >11 (OR 1.77)

- Uncommon infection sources (OR 1.63)

- Local resistance patterns, particularly high rates of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (OR 2.46) [19]

While often clinically necessary, this approach creates significant diagnostic challenges. A study by Vincent et al. revealed that more than 70% of ICU patients receive antibiotics, yet only about half of these treatments target documented infections [18]. This discrepancy highlights the substantial proportion of unnecessary antimicrobial exposure that occurs due to diagnostic uncertainty, contributing directly to the AMR crisis.

Impact of Antibiotics on Culture-Based Diagnostics

Culture-based methods remain the reference standard for pathogen identification but possess critical limitations when patients have received prior antibiotic therapy. Table 1 summarizes the primary mechanisms through which empirical antibiotics reduce culture sensitivity and cause diagnostic delays.

Table 1: Impact Mechanisms of Empirical Antibiotics on Culture-Based Diagnostics

| Impact Mechanism | Effect on Culture Sensitivity | Consequence for Diagnostic Delays |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Microbial Viability | Induction of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) states; direct killing of susceptible organisms [18] [21] | False-negative results requiring repeat sampling; extended incubation periods |

| Delayed Time-to-Positivity | Sub-lethal antibiotic effects slow bacterial metabolism and replication [22] | Prolonged time to obtain actionable results (typically 48-72 hours) [18] |

| Altered Phenotypic Expression | Antibiotic pressure selects for resistant subpopulations not representative of original infection [20] | Inaccurate antimicrobial susceptibility profiles leading to inappropriate therapy |

| Masked Polymicrobial Infections | Suppression of susceptible species while resistant organisms proliferate [23] | Incomplete pathogen identification resulting in inadequate antimicrobial coverage |

The constraints of conventional techniques are particularly problematic in critical care settings, where the diagnostic window is narrow, and clinical deterioration can be rapid. Culture-based diagnostics typically require 48-72 hours or longer to yield actionable results, during which patients often receive prolonged, unnecessary broad-spectrum therapy [18]. This delay is especially consequential for infections caused by resistant organisms, where inadequate or delayed therapy is independently associated with higher mortality [18].

Comparative Analysis of Pathogen Detection Methods

Established Culture-Based Methodologies

Standard Protocols and Workflows

Conventional culture-based diagnosis typically begins with specimen inoculation onto selective and enriched media, followed by incubation for 24-48 hours to isolate pathogenic bacteria [20]. Automated biochemical testing systems then facilitate microbial identification, complemented by antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) using disk diffusion, broth microdilution, or gradient diffusion methods to guide therapeutic decisions [20]. The complete workflow from sample collection to AST results typically requires 48-72 hours, creating a critical therapeutic decision-making gap during the initial period of infection management.

The EUROBACT-2 international cohort study, which included data from 2406 adult patients across 328 ICUs in 52 countries, exemplifies the real-world application of these methods for diagnosing hospital-associated bloodstream infections [19]. In this context, blood culture serves as the fundamental diagnostic trigger, yet its utility is maximized only when followed by rapid and accurate identification and AST processes.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Culture-Based Diagnostics

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Enriched & Selective Media | Isolation of pathogenic bacteria from clinical specimens by providing nutrients and inhibiting non-target organisms [20] | Blood agar, MacConkey agar, Chromogenic media for specific pathogen selection |

| Automated Biochemical Test Panels | Microbial identification based on metabolic capabilities and enzymatic activities [20] | API strips, VITEK systems, MALDI-TOF target plates |

| Antimicrobial Disks & Gradient Strips | Determination of antimicrobial susceptibility profiles through diffusion-based methods [20] [22] | Kirby-Bauer disks, Etest strips for MIC determination |

| Broth Microdilution Panels | Quantitative assessment of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) in liquid culture [22] | CLSI-compliant panels for AST confirmation |

Modern Molecular Diagnostic Platforms

Technical Principles and Workflows

Molecular diagnostics have emerged as powerful alternatives to culture-based methods, particularly in the context of pre-exposure to empirical antibiotics. These platforms detect microbial nucleic acids or antigens rather than relying on viable organisms, thereby bypassing many limitations associated with antimicrobial pretreatment [18] [20].

Syndromic molecular panels represent one of the most significant advances, with platforms like the BioFire Blood Culture Identification (BCID) panel enabling simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens and resistance genes directly from positive blood cultures within hours [18]. Isothermal amplification techniques, such as loop-mediated amplification (LAMP), provide a cost-effective alternative to PCR-based methods, requiring less specialized equipment while maintaining high sensitivity [20].

Metagenomic sequencing represents the most comprehensive approach, allowing for culture-independent pathogen detection and resistance gene prediction. A recent study demonstrated a direct-from-blood-culture metagenomic sequencing method using Oxford Nanopore technology that achieved 97% sensitivity and 94% specificity for species identification, delivering results in just 3.5 hours—approximately one-third the time required by routine methods [23].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Diagnostics

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Protocol | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation and purification of pathogen DNA/RNA from clinical specimens while removing inhibitors [23] | Commercial kits for blood culture DNA extraction, automated extraction systems |

| Amplification Master Mixes | Provide optimized enzymes, buffers, and nucleotides for target-specific nucleic acid amplification [20] | PCR/LAMP reagents with integrated fluorescence detection |

| Hybridization Probes & Primers | Sequence-specific recognition of target pathogens or resistance genes through complementary binding [20] | TaqMan probes, molecular beacons, FISH probes |

| Sequence-Specific Reagents | Library preparation and barcoding for high-throughput sequencing applications [23] | Nanopore sequencing kits, Illumina library prep reagents |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the parallel pathways and critical decision points in traditional culture-based versus modern molecular diagnostic approaches:

Diagram 1: Comparative diagnostic workflows showing impact of empirical antibiotics.

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Quantitative Method Comparison

The performance disparities between culture-based and molecular diagnostic methods become particularly evident when analyzing key metrics across multiple studies. Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of these methodologies based on recent clinical evaluations.

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Methods for Pathogen Detection

| Methodology | Typical Turnaround Time | Sensitivity After Antibiotic Exposure | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture & AST | 48-72 hours [18] | Significantly reduced due to VBNC state induction [18] [21] | Gold standard; provides live isolates for further testing; quantitative results [20] | Long turnaround time; low sensitivity post-antibiotics; unable to detect uncultivable organisms [18] |

| Rapid Molecular Panels | 1.5-6 hours [18] | Minimal impact (detects nucleic acids) [18] [20] | Rapid results; high sensitivity/specificity; detects resistance genes directly [18] | Limited target spectrum; higher cost; may miss novel resistance mechanisms [20] |

| Metagenomic Sequencing | 3.5-24 hours [23] | Minimal impact (detects nucleic acids) [23] | Comprehensive pathogen detection; discovers novel organisms; predicts AMR from genetic markers [23] | High cost; complex data analysis; requires specialized expertise [23] |

| AI-Powered Diagnostics | Minutes to hours [24] | Minimal impact (analysis of direct signatures) [24] | Ultra-rapid analysis; pattern recognition; predictive analytics for resistance [24] | Early development stage; validation limited; infrastructure requirements [24] |

Impact on Clinical Outcomes

The diagnostic delays inherent to culture-based methods have demonstrable clinical consequences. Studies indicate that inadequate or delayed therapy in the presence of resistant pathogens is independently associated with higher mortality, particularly in bloodstream infections and ventilator-associated pneumonias [18]. Infections caused by resistant organisms are associated with increased morbidity, length of ICU stay, mechanical ventilation duration, and healthcare costs [18].

Conversely, rapid diagnostic technologies have demonstrated significant benefits. Metagenomic sequencing applied directly to blood cultures detected 18 additional infections—13 polymicrobial and 5 previously unidentifiable—compared to standard methods, while delivering findings 20 hours faster for antimicrobial resistance prediction [23]. For key pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, this approach achieved AMR prediction sensitivities of 100% and 91%, and specificities of 99% and 94%, respectively [23].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Novel Diagnostic Platforms

Artificial intelligence (AI) is poised to revolutionize bacterial diagnostics and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. AI-powered platforms can automate the analysis of complex datasets from various diagnostic modalities, including microscopy, mass spectrometry, and Raman spectroscopy, enabling faster and more accurate bacterial identification [24]. Machine learning algorithms, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and support vector machines (SVMs), have been successfully applied to tasks ranging from colony counting on agar plates to analyzing surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) data for antibiotic resistance detection [24].

Biosensor technologies represent another promising frontier, offering the potential for rapid, point-of-care pathogen detection. These systems transduce microbial signatures into measurable signals, with electrochemical, optical, and mass-sensitive biosensors showing particular promise for clinical application [24]. When integrated with AI for data interpretation, these platforms could enable real-time pathogen identification and resistance profiling at the bedside, fundamentally transforming infection management.

Advanced Therapeutic Discovery

The challenges of antimicrobial resistance have spurred innovation in therapeutic discovery, with deep learning approaches now enabling the mining of proteomic data for novel antibiotic candidates. The APEX (antibiotic peptide de-extinction) platform utilizes multitask deep learning to predict antimicrobial activity from peptide sequences, successfully identifying 37,176 sequences with predicted broad-spectrum activity from extinct organism proteomes [25]. Experimental validation confirmed the activity of 69 synthesized peptides, with several showing efficacy in mouse infection models [25].

These computational approaches are particularly valuable given the unique challenges of antibiotic discovery, including the restrictive penetration barrier that makes conventional screening of synthetic compound libraries largely impractical [26]. By leveraging AI to explore previously untapped sequence spaces, researchers can accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic candidates to address the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance.

The tension between empirical antibiotic therapy and diagnostic sensitivity represents a fundamental challenge in modern infectious disease management. While culture-based methods remain essential for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, their limitations in the context of pretreatment with empirical antibiotics are increasingly apparent. Molecular diagnostics, including syndromic panels and metagenomic sequencing, offer compelling advantages in speed and sensitivity, particularly for patients who have already received antimicrobial therapy.

The integration of these advanced diagnostic platforms into antimicrobial stewardship programs is crucial for optimizing therapy, improving patient outcomes, and combating the global rise of antimicrobial resistance. Future developments in AI-powered diagnostics and biosensor technologies promise to further bridge the gap between therapeutic intervention and pathogen identification, potentially enabling a new paradigm of precision infectious disease management. As these technologies mature and become more accessible, they offer the potential to resolve the critical conflict between immediate therapeutic needs and long-term diagnostic efficacy.

The cornerstone of microbiology, culture-based methods, has long provided the foundation for pathogen discovery. However, a paradigm shift is underway. It is now established that a vast majority of microbial life, often referred to as "microbial dark matter," resists cultivation under standard laboratory conditions [27] [28]. This review objectively compares the performance of traditional culture-based techniques with modern molecular methods for pathogen discovery. We synthesize experimental data demonstrating how molecular techniques reveal significantly greater microbial diversity, while culture-based methods remain vital for obtaining isolates for phenotypic studies. By integrating recent findings from clinical and environmental studies, this guide provides a framework for researchers to select appropriate methodologies, highlighting that an integrated approach offers the most comprehensive assessment of microbial communities.

The "great plate count anomaly" – the observation that typically less than 2% of environmental microorganisms form colonies on agar plates – highlights a fundamental limitation in traditional microbiology [29]. This is not merely a technical hurdle; it represents a critical gap in our understanding of life on Earth, particularly in the human microbiome where an estimated 40-50% of species lack a reference genome [28]. In clinical settings, this bottleneck has direct consequences for patient care, as standard diagnostic cultures may miss fastidious, slow-growing, or non-cultivatable pathogens, potentially leading to inadequate antimicrobial treatments, especially in polymicrobial infections where mortality risk increases by 2-3 folds compared to monomicrobial infections [30]. The emergence of sophisticated molecular techniques is now dismantling this barrier, enabling researchers to explore the immense diversity of uncultured microorganisms and their potential roles in health, disease, and biotechnology.

Methodological Comparison: Culture-Based vs. Molecular Approaches

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

The core distinction between these methodologies lies in their basic approach: culture-based methods rely on microbial growth and replication in artificial media, while molecular techniques detect microbial DNA or RNA directly from samples.

Culture-Based Methods require the selection of appropriate growth media and incubation conditions (e.g., aerobic, anaerobic, specific temperatures) to support the replication of microorganisms. The process involves sample inoculation, incubation, and subsequent analysis of grown colonies through morphological examination and biochemical tests. Advanced cultivation techniques for anaerobes, such as the roll-tube method and the use of anaerobic chambers with atmospheres of 95% nitrogen and 5% hydrogen, have improved recovery but remain technically challenging [29].

Molecular Methods bypass the need for cultivation by directly analyzing genetic material. Key approaches include:

- PCR-Based Techniques (Traditional PCR, qPCR, ddPCR): Amplify and detect specific target DNA sequences.

- Sequencing-Based Techniques: Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) sequences all DNA in a sample, enabling broad pathogen detection without prior knowledge of organisms present [7].

- Hybrid Methods: Culture-enriched metagenomic sequencing (CEMS) involves culturing samples on multiple media, pooling all grown colonies, and then performing metagenomic sequencing, thus combining growth enrichment with comprehensive genetic analysis [31].

The workflow differences are substantial, as illustrated below:

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Multiple studies have quantitatively compared the detection capabilities of culture-based and molecular methods across various sample types. The following table synthesizes key comparative findings:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Culture-Based vs. Molecular Methods in Pathogen Detection

| Study Context | Culture-Based Detection Rate | Molecular Method Detection Rate | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected Bloodstream Infection (n=99) | 13.13% (13/99 patients) | 65.66% (65/99 patients); mNGS | mNGS detected viruses in 22 patients; concordance for bacteria/fungi only 12% | [7] |

| Chronic Diabetic Foot Wounds (n=26) | 50% (13/26 wounds) | Significantly greater bacterial diversity (P<0.05); DGGE | Molecular methods detected Staphylococcus sp. in 11/13 putatively uninfected wounds | [32] |

| Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections (n=20) | 70% of samples | 90% of samples; Multiple molecular methods | Molecular methods frequently detected additional microorganisms | [16] |

| Human Gut Microbiome (n=1) | 36.5% of species (CEMS) | 45.5% of species (CIMS); Metagenomic sequencing | Only 18% species overlap between methods; both approaches essential | [31] |

| Global Human Gut Microbiome | Reference genomes for ~50% of phylogenetic diversity | 60,664 MAGs identified 2,058 novel species; 50% increase in diversity | Newly identified species accounted for 28% of abundance per individual | [28] |

The data consistently demonstrate molecular methods' superior sensitivity for detecting microbial diversity, though culture remains indispensable for isolating viable organisms.

Technical Protocols for Microbial Diversity Assessment

Culture-Enriched Metagenomic Sequencing (CEMS)

Sample Preparation and Cultivation:

- Fresh fecal sample (0.5 g) is homogenized in 4.5 g distilled water and serially diluted (10â»Â³ to 10â»â·) in 0.85% NaCl solution [31].

- Aliquot 200 µL of each dilution onto 12 different commercial or modified media types, including nutrient-rich media (LGAM, PYG), selective media (MAR with high salt), and oligotrophic media (1/10GAM) [31].

- Incubate duplicate sets anaerobically (95% N₂, 5% H₂) and aerobically at 37°C for 5-7 days [31].

Metagenomic Analysis:

- Harvest all colonies from each medium using a cell scraper with 0.85% NaCl solution [31].

- Extract DNA using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit following manufacturer's instructions [31].

- Perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing using Illumina HiSeq 2500, generating 100 bp paired-end reads [31].

- Process data through HUMANN2 pipeline using MetaPhlAn2 for microbial composition profiling [31].

PCR-Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis (DGGE)

DNA Extraction and Amplification:

- Extract DNA from clinical samples using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit [32].

- Amplify the V2-V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene using eubacterium-specific primers HDA1 (with GC clamp) and HDA2 [32].

- Thermal amplification program: 94°C for 4 minutes; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 56°C for 30s, 68°C for 60s; final elongation at 68°C for 7 minutes [32].

DGGE Analysis:

- Perform polyacrylamide electrophoresis with 30% and 60% denaturing concentrations using the DCode Universal Mutation Detection System [32].

- Analyze banding patterns to assess microbial diversity; excise and sequence distinctive bands for taxonomic identification [32].

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) for Bloodstream Infections

Sample Processing:

- Collect 6-8 mL of blood in sterile containers [7].

- Extract DNA using QIAamp DNA Micro Kit or QIAamp Microbiome DNA Kit [7].

- Construct libraries using QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit or Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit [7].

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequence on Illumina Nextseq platform (100-150 bp reads) [7].

- Remove adapter sequences, low-quality reads, and human host sequences by alignment to hg38/hg19 reference [7].

- Align remaining reads to microbial genome databases; positive detection criteria vary by microbe type but generally require RPMsample/RPMNTC ratio >10 [7].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful assessment of uncultured microbial diversity requires specific reagents and tools. The following table catalogizes key solutions and their applications:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Diversity Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, QIAamp DNA Micro Kit, QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit | High-quality DNA extraction from diverse sample types | [32] [31] [7] |

| PCR Reagents | HDA1/HDA2 primers, Red Taq DNA polymerase ready mix | Amplification of 16S rRNA gene regions for diversity analysis | [32] |

| Specialized Growth Media | LGAM, PYG, GAM, MRS-L, RG, 1/10GAM | Cultivation of diverse microbial communities under various nutritional conditions | [31] |

| Library Preparation Kits | QIAseq Ultralow Input Library Kit, Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries from low-input DNA samples | [7] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | HUMANN2, MetaPhlAn2, DIAMOND, IGGsearch | Taxonomic profiling, functional analysis, and quantification of microbial abundance | [31] [28] |

| Anaerobic System Components | Anaerobic chamber (95% Nâ‚‚, 5% Hâ‚‚), roll tubes, pre-reduced media | Cultivation of oxygen-sensitive anaerobic microorganisms | [29] |

Integrated Analysis and Future Directions

The experimental data consistently demonstrate that molecular methods detect a substantially greater proportion of microbial diversity than culture-based methods alone. In suspected bloodstream infections, mNGS demonstrated a 5-fold higher detection rate compared to blood culture (65.66% vs. 13.13%) [7]. In gut microbiome studies, culture-enriched metagenomic sequencing (CEMS) and direct culture-independent metagenomic sequencing (CIMS) showed limited overlap (18% of species), indicating these methods access different components of the microbial community [31].

The clinical implications are significant. Molecular methods can identify pathogens in cases where cultures remain negative, particularly after antibiotic administration [16]. Furthermore, they reveal the polymicrobial nature of many infections, which is crucial since polymicrobial bloodstream infections increase mortality risk by 2-3 folds compared to monomicrobial infections [30].

However, culture-based methods provide irreplaceable benefits: they yield live isolates for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, functional characterization, and detailed physiological studies [29]. The future of pathogen discovery lies in integrated approaches that leverage the strengths of both methodologies. Culturing the uncultured requires innovative strategies such as growth-curve-guided cultivation, which uses real-time monitoring to identify optimal isolation points for slow-growing organisms before they are outcompeted [29].

As molecular technologies continue to advance—with improvements in long-read sequencing, single-cell genomics, and bioinformatic analysis—our ability to explore the vast uncultured microbial diversity will expand exponentially, opening new frontiers for drug discovery, microbiome research, and clinical diagnostics.

The Molecular Toolkit: PCR, Sequencing, and CRISPR in Modern Pathogen Detection

The shift from traditional culture methods to molecular techniques represents a fundamental evolution in pathogen discovery research. While culture-based methods have long been the gold standard, they are often time-consuming, limited in sensitivity, and unable to detect unculturable organisms. The advent of quantitative PCR (qPCR) introduced a new era of speed and specificity, yet this method still relied on relative quantification against standard curves, introducing potential variability. The emergence of digital PCR (dPCR) and its droplet-based counterpart ddPCR now enables absolute quantification of nucleic acids without standard curves, offering unprecedented precision for applications ranging from viral load monitoring to rare mutation detection [33] [34] [35]. This technological revolution provides researchers with powerful tools to address the limitations of both conventional culture methods and earlier molecular techniques, particularly for challenging samples with low pathogen concentrations or significant inhibitor content.

Fundamental Principles: How dPCR Achieves Absolute Quantification

The Partitioning Principle of Digital PCR

Digital PCR operates on a fundamentally different principle than qPCR. Rather than monitoring amplification in real-time through cycle threshold (Ct) values, dPCR partitions a single PCR reaction into thousands to millions of individual reactions [36] [34]. This partitioning occurs through various mechanisms including water-oil emulsion droplets (ddPCR), fixed micro-wells (nanoplate dPCR), or microfluidic chips (cdPCR) [36]. Each partition ideally contains zero or one (or a few) target DNA molecules. After end-point PCR amplification, each partition is analyzed as either positive (containing the target sequence) or negative (not containing the target) [34]. The ratio of positive to total partitions, analyzed using Poisson statistics, allows for the absolute quantification of the target nucleic acid in the original sample without the need for standard curves [33] [34].

Key Technological Variations in dPCR Platforms

The dPCR landscape encompasses several partitioning technologies, each with distinct advantages:

- Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): Uses immiscible fluids to generate tens of thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets that serve as individual reaction chambers [36] [33]. This approach typically generates the highest number of partitions but involves multiple instruments and transfer steps.

- Nanoplate-based dPCR: Employs microfluidic digital PCR plates with predefined wells (e.g., 8,500-26,000 partitions) [36]. This integrated system combines partitioning, thermocycling, and imaging in a single instrument, offering a streamlined workflow similar to qPCR.

- Chip-based dPCR (cdPCR): Utilizes microfluidic chips with thousands of nanoliter reaction chambers [36]. This approach offers fast partitioning but may involve more complex fluidics.

- Crystal Digital PCR: A hybrid approach combining cdPCR's 2D array format with droplet partitions, creating monolayer arrays of monodisperse droplets [36].

Table 1: Comparison of Major dPCR Partitioning Methods

| Partitioning Method | Number of Partitions | Volume of Partitions | Key Principles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoplate | 8,500-26,000 | ~10 nL | Microfluidic digital PCR plate |

| Droplet generator | 10,000-1,000,000+ | 10-100 pL | Water-oil emulsion droplets |

| Microfluidic chambers | ~1,000,000 | ~10 nL | Pinning of oil interface to isolate chambers |

| Open arrays of microwells | ~100,000 | ~10 nL | Capillary action loading |

| CZL55 | CZL55, MF:C20H22N2O6, MW:386.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| FM19G11 | FM19G11, CAS:329932-55-0, MF:C23H17N3O8, MW:463.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Comparative Performance: dPCR vs. qPCR in Diagnostic Applications

Tuberculosis Diagnostics: Enhanced Detection of Paucibacillary Disease

A 2023 meta-analysis of 14 diagnostic accuracy studies compared ddPCR and qPCR for detecting pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis [35]. The analysis included 1,672 participants or biological samples and 975 tuberculosis events. While qPCR demonstrated higher sensitivity [0.66 (95% CI 0.60-0.71)] compared to ddPCR [0.56 (95% CI 0.53-0.58)], ddPCR showed superior discriminant capacity with a higher area under the ROC curve (0.97 for ddPCR vs. 0.94 for qPCR, p=0.002) [35]. This difference was particularly pronounced for extrapulmonary tuberculosis, where traditional methods often fail due to extremely low acid-fast bacilli concentrations [35]. The absolute quantification capability of ddPCR provides significant advantages for paucibacillary samples where accurate quantification at low target concentrations is critical for diagnosis and treatment monitoring.

Respiratory Virus Detection During the 2023-2024 Tripledemic

A 2025 study comparing dPCR and Real-Time RT-PCR for detecting influenza A, influenza B, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 during the 2023-2024 tripledemic demonstrated dPCR's superior quantification accuracy, particularly for samples with high viral loads [37]. The study analyzed 123 respiratory samples stratified by cycle threshold (Ct) values into high (Ct≤25), medium (Ct25.1-30), and low (Ct>30) viral load categories. dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, and for medium loads of RSV [37]. The technology showed greater consistency and precision than Real-Time RT-PCR, especially in quantifying intermediate viral levels, highlighting its potential for precise viral load monitoring in co-infection scenarios [37].

Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli Detection in Environmental Samples

Research on Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) detection in environmental samples demonstrated ddPCR's superior sensitivity for low-concentration targets [33]. While recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) detected <10 CFU/mL and qPCR quantified from 10³ to 10ⷠCFU/mL, ddPCR showed quantification from 1 to 10ⴠCFU/mL with high reproducibility [33]. This study also highlighted ddPCR's greater tolerance to inhibitors present in complex environmental matrices like dairy lagoon effluent and high-rate algae pond effluent. Unlike qPCR, which is highly dependent on amplification efficiency and can be significantly affected by inhibitors, ddPCR's endpoint measurement and partitioning approach reduce the impact of substances that would normally inhibit PCR amplification [33].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of qPCR and dPCR Across Applications

| Application | qPCR Performance | dPCR/ddPCR Performance | Key Advantage of dPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis Diagnosis | Sensitivity: 0.66, Specificity: 0.98 [35] | Sensitivity: 0.56, Specificity: 0.97, AUC: 0.97 [35] | Superior discriminant capacity (AUC), especially for extrapulmonary TB |

| Respiratory Virus Detection | Variable quantification based on standard curves [37] | Superior accuracy for high viral loads, greater consistency [37] | Absolute quantification without standard curves, precision at intermediate viral loads |

| STEC Detection in Environmental Samples | Quantification from 10³ to 10ⷠCFU/mL [33] | Quantification from 1 to 10ⴠCFU/mL, high reproducibility [33] | Enhanced sensitivity for low-concentration targets, better inhibitor tolerance |

| Gene Expression Analysis | Relative to reference genes [38] | Absolute quantification without reference genes [38] | No need for stable reference genes, direct comparison across experiments |

Technical Comparison: dPCR vs. ddPCR Platforms and Workflows

Workflow Efficiency and Practical Implementation

The choice between dPCR and ddPCR platforms involves significant practical considerations for laboratory workflow:

- dPCR (Nanoplate Systems): Offers integrated, automated workflows with complete processing in 2-3 hours [36] [39]. Systems like the QIAcuity provide "sample-in, results-out" processing in a single instrument, significantly reducing hands-on time and contamination risk [36] [39]. This streamlined approach is particularly valuable for quality control environments and regulated laboratories.

- ddPCR (Droplet Systems): Typically involves multiple instruments (droplet generator, thermocycler, droplet reader) and requires 6-8 hours for complete processing [36] [39]. The workflow includes multiple pipetting and transfer steps, increasing the risk of cross-contamination and requiring trained personnel [36]. However, ddPCR can generate a higher number of partitions (up to millions), potentially increasing sensitivity for rare targets [36].

Multiplexing Capability and Data Quality

Modern dPCR platforms offer enhanced multiplexing capabilities compared to earlier ddPCR systems. Nanoplate-based dPCR systems can detect up to 5-12 targets in a single reaction, allowing simultaneous measurement of multiple biomarkers [36] [39]. While newer ddPCR models have improved multiplexing capabilities (up to 12 targets), they traditionally have been more limited in this regard [39]. Data quality can also be affected by technical issues specific to each platform. ddPCR may suffer from "rain" droplets (intermediate fluorescence signals) caused by damaged droplets, non-specific amplification, or irregular droplet size, complicating threshold setting [36]. Nanoplate dPCR eliminates variability associated with droplet size and coalescence, potentially offering more robust and reproducible results [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions for dPCR

Successful implementation of dPCR technologies requires specific reagent systems optimized for partition-based amplification:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Digital PCR

| Reagent Type | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Primer-Probe Mixes | Target-specific amplification and detection | Commercial multiplex assays for respiratory viruses (Influenza A/B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2) [37] |

| dPCR Master Mixes | Optimized for partition-based amplification | Pre-mixed master mixes with digital PCR optimizers [36] |

| Partitioning Fluids | Create stable emulsion (ddPCR) or seal partitions | Immiscible oils for droplet stabilization [36] |

| Reference Assays | Quality control of sample processing | Internal positive controls for extraction and amplification [37] |

| Quantitative Standards | Assay validation and performance verification | Synthetic nucleic acids with known copy numbers [34] |

| Lixisenatide | Lixisenatide, CAS:320367-13-3, MF:C215H347N61O65S, MW:4858 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lipofermata | Lipofermata, MF:C15H10BrN3OS, MW:360.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The revolution from standard to digital PCR represents a significant advancement in quantification capabilities for pathogen discovery research. While qPCR remains suitable for many high-throughput screening applications, dPCR technologies provide superior precision for absolute quantification, particularly for low-abundance targets, complex matrices with inhibitors, and situations requiring exact copy number determination without reference standards [33] [35] [37]. The choice between dPCR platforms should be guided by specific application requirements: nanoplate-based systems offer streamlined workflows advantageous for quality control and regulated environments [36] [39], while droplet-based systems provide maximum partitioning density for detecting rare targets [36]. As these technologies continue to evolve with improved multiplexing capabilities, reduced costs, and enhanced automation, dPCR is poised to become an increasingly indispensable tool in the molecular pathology toolkit, bridging the gap between traditional molecular methods and the emerging era of precision pathogen quantification.

The field of pathogen discovery has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS). This hypothesis-free approach represents a fundamental departure from both traditional culture-based methods and targeted molecular diagnostics, enabling comprehensive detection of pathogens without prior knowledge of the causative agent [40]. While conventional microbiological testing (CMT) has long served as the cornerstone of infectious disease diagnosis, its limitations—including prolonged turnaround times, low sensitivity for fastidious organisms, and the requirement for specific growth conditions—have driven the development of more agnostic detection methods [41]. The ongoing comparison between culture and molecular methods for pathogen discovery now centers on how mNGS complements and enhances traditional approaches, particularly for difficult-to-diagnose infections where conventional methods often fail to identify causative pathogens [42].

mNGS operates on a simple yet powerful principle: by sequencing all nucleic acids in a clinical sample and computationally subtracting human sequences, it can detect any pathogen—bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic—present in the sample [40]. This unbiased nature makes it particularly valuable for diagnosing unusual infections, detecting emerging pathogens, and identifying co-infections that might be missed by targeted approaches [43]. As the technology has evolved from research settings to clinical applications, understanding its performance characteristics relative to established methods has become essential for researchers, clinical microbiologists, and infectious disease specialists seeking to implement this powerful tool in diagnostic and research pipelines.

Performance Comparison: mNGS Versus Conventional Diagnostic Methods

Comprehensive Diagnostic Performance Metrics

Extensive clinical studies across diverse infection types and sample matrices have demonstrated that mNGS consistently outperforms conventional methods in sensitivity while maintaining high specificity, though its performance varies depending on the clinical context and pathogen type.

Table 1: Overall Diagnostic Performance of mNGS Across Various Infection Types

| Infection Type | Reference Standard | mNGS Sensitivity | mNGS Specificity | Conventional Method Sensitivity | Conventional Method Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Nervous System Infections [44] | Clinical composite | 63.1% | 99.6% | 45.9% (CSF direct detection) | - |

| Spinal Infections [45] | Histopathology/IDSA criteria | 81% | 75% | 34% (Tissue Culture) | 93% |

| Pulmonary Infections [41] | Clinical composite | 78.89% (etiological diagnosis rate) | - | 20% (etiological diagnosis rate) | - |

| Bloodstream Infections [7] | Clinical composite | 65.66% (positivity rate) | - | 13.13% (positivity rate) | - |

The superior sensitivity of mNGS is particularly evident in challenging clinical scenarios. In a seven-year analysis of 4,828 cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples, mNGS demonstrated significantly higher sensitivity (63.1%) compared to indirect serologic testing (28.8%) and direct detection testing from both CSF (45.9%) and non-CSF samples (15.0%) [44]. Notably, 21.8% of infectious diagnoses would have been missed without mNGS testing, underscoring its unique value in detecting pathogens that evade conventional methods [44].

Pathogen-Specific Performance Variations

The diagnostic performance of mNGS varies considerably across pathogen types, reflecting differences in microbial burden, nucleic acid extraction efficiency, and background host DNA.

Table 2: Pathogen-Specific Detection by mNGS in CNS Infections (7-Year Study of 4,828 Samples) [44]

| Pathogen Category | Number Detected | Percentage of Total | Notable Pathogens Detected |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Viruses | 363 | 45.5% | Herpesviruses, Polyomaviruses |

| RNA Viruses | 211 | 26.4% | HIV, Arboviruses, Enteroviruses |

| Bacteria | 132 | 16.6% | Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Borrelia burgdorferi |

| Fungi | 68 | 8.5% | Coccidioides spp., Cryptococcus spp. |

| Parasites | 23 | 2.9% | Balamuthia mandrillaris |

For specific pathogens, mNGS shows exceptional capability. In tuberculosis detection, mNGS demonstrated 92.31% sensitivity compared to a composite reference standard, rivaling real-time PCR (90.38%) while maintaining perfect specificity (100%) [46]. The strong negative correlation between mNGS standardized microbial read numbers (SMRNs) and PCR cycle threshold values further validates its quantitative potential [46].

In immunocompromised populations, mNGS shows particular utility. For people living with HIV/AIDS with CNS disorders, mNGS achieved a positivity rate of 75% compared to 52.1% with conventional methods, with significantly improved detection of multiple pathogens (41.7% vs. 8.3%) [43]. This enhanced detection capability is crucial in populations susceptible to opportunistic infections and co-infections.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized mNGS Workflow

The mNGS workflow consists of multiple critical steps, each requiring optimization to ensure diagnostic accuracy while minimizing contamination and bias.

Standard mNGS Experimental Workflow

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Sample Processing and Nucleic Acid Extraction

The initial phase of mNGS testing requires meticulous sample handling to preserve nucleic acid integrity while maximizing pathogen recovery. For cerebrospinal fluid samples, typical protocols involve processing 600 μL of CSF mixed with enzymes and glass beads, followed by vigorous vortexing at 2,800-3,200 rpm for 30 minutes [47]. Total DNA extraction is then performed using commercial kits such as the TIANamp Micro DNA Kit, with careful attention to minimizing contamination [47] [48]. For bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, additional pretreatment steps may include sterilization at 65°C for 30 minutes and lysozyme treatment to break down bacterial cell walls [41].

The DNA extraction process follows manufacturer recommendations, with DNA concentration measured using fluorescent quantification methods like the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit [41]. This step is critical as insufficient input DNA can lead to failed libraries or inadequate sequencing depth, while excess host DNA can swamp pathogen signals.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library construction typically employs transposase-based fragmentation methods (Nextera XT, KAPA HyperPlus) that simultaneously fragment DNA and add sequencing adapters [41] [42]. Following end repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification, libraries undergo rigorous quality control using instruments such as the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer to assess fragment size distribution and concentration [48].

Sequencing is most commonly performed on Illumina platforms (NextSeq, MiSeq) using single-end or paired-end chemistry, with a target of 20 million reads per sample to ensure sufficient depth for detecting low-abundance pathogens [41] [42]. The BGISEQ platform is also widely used, particularly in Chinese clinical laboratories [48]. Each sequencing run includes negative controls (no-template water or buffer) to monitor for contamination introduced during library preparation or sequencing.

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

The bioinformatic workflow begins with quality control of raw sequencing data using tools like fastp to remove low-quality reads, adapter sequences, and short fragments (<35-50 bp) [46] [42]. Human sequence depletion is then performed by alignment to reference genomes (GRCh38/hg38) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner or other mapping tools [48] [7].

The remaining non-human reads are classified by alignment to comprehensive microbial databases containing bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasite genomes downloaded from NCBI or other public repositories [47] [48]. Positive detection thresholds vary by pathogen type but typically require reads to be significantly enriched over negative controls (RPMsample/RPMNTC ≥ 5-10) [42] [7]. For specific pathogens with low contamination risk like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, even a single unique read may be considered significant [48].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of mNGS in pathogen discovery requires carefully selected reagents, instruments, and computational resources. The following table details essential components of the mNGS workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for mNGS Pathogen Discovery

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Key Function | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | TIANamp Micro DNA Kit (Tiangen) [47] [48], QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen) [7] | Isolation of microbial nucleic acids from clinical samples | Efficiency varies by pathogen type; critical for robust detection |

| Library Preparation | KAPA HyperPlus Kit (Roche) [42], Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina) [7], PMseq kits (BGI) [41] | Fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification for sequencing | Impact library complexity and representation |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NextSeq/MiSeq [41] [42], BGISEQ-50/MGISEQ-2000 (MGI) [48] | High-throughput sequencing | Different throughput, read length, and error profiles |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Burrows-Wheeler Aligner, Trimmomatic, fastp [42] [7] | Quality control, host depletion, microbial alignment | Critical for sensitive, specific pathogen detection |

| Reference Databases | NCBI RefSeq, in-house curated databases [47] [48] | Taxonomic classification of sequencing reads | Comprehensiveness impacts range of detectable pathogens |

| Quality Control Reagents | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit, Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer kits [41] [7] | Assessment of nucleic acid and library quality | Essential for troubleshooting and process optimization |

| K-Ras-IN-2 | K-Ras-IN-2 | KRAS Antagonist Research Compound | K-Ras-IN-2 is a potent K-Ras antagonist for cancer research. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Acefylline | Acefylline, CAS:652-37-9, MF:C9H10N4O4, MW:238.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The selection of appropriate reagents and platforms depends on multiple factors, including sample type, target pathogens, and available infrastructure. For instance, the Illumina platform dominates clinical applications with more than 50% of studies using this technology [40], while BGISEQ platforms are widely implemented in Chinese clinical laboratories [41] [48]. Extraction efficiency varies considerably across pathogen types, with gram-positive bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi presenting particular challenges due to their robust cell walls [42].

Critical Analysis of Strengths and Limitations in Clinical Implementation

Key Advantages of mNGS in Pathogen Discovery

The unbiased nature of mNGS provides several distinct advantages over both culture and targeted molecular methods. Most significantly, mNGS enables detection of unexpected, rare, or novel pathogens without requiring prior suspicion [40] [44]. In a study of patients with severe infections, mNGS exhibited particular strength in identifying rare pathogens such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, and Legionella pneumophila that were undetectable by conventional methods [41]. This comprehensive detection capability is further enhanced by the ability to identify multiple pathogens in co-infections, which occurred in 27.1% of HIV patients with CNS disorders [43].