Nutrient Gradients and Bacterial Persistence: Mechanisms, Models, and Therapeutic Targeting in Biofilms

This article synthesizes current research on how nutrient gradients within biofilms drive the formation of antibiotic-tolerant persister cells, a major cause of chronic and recurrent infections.

Nutrient Gradients and Bacterial Persistence: Mechanisms, Models, and Therapeutic Targeting in Biofilms

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on how nutrient gradients within biofilms drive the formation of antibiotic-tolerant persister cells, a major cause of chronic and recurrent infections. It explores the foundational molecular mechanisms, including the stringent response and toxin-antitoxin systems, activated by nutrient limitation. The content details advanced methodological approaches, from experimental models to mathematical simulations, used to study these heterogeneous environments. Furthermore, it examines the challenges in eradicating persisters and evaluates emerging therapeutic strategies that target nutrient-driven persistence. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and combating biofilm-associated treatment failures.

The Biofilm Environment: How Nutrient Gradients Create Persister Cell Sanctuaries

Architectural and Physiological Heterogeneity in Biofilms

Biofilms are structured microbial communities embedded in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix, representing the predominant mode of bacterial life [1] [2]. Their architecture is not uniform but is characterized by profound spatial and physiological heterogeneity, which arises from the complex interplay between microbial metabolism and environmental gradients [3] [4]. This heterogeneity is a critical determinant of biofilm function, influencing everything from metabolic efficiency to resilience against antimicrobial agents.

Within the context of antimicrobial therapy failure, the relationship between nutrient gradients and the formation of antibiotic-tolerant persister cells is of paramount importance. As biofilms mature, the consumption of nutrients by cells in outer layers creates chemical gradients, leading to nutrient limitation in the biofilm interior [3] [4]. This spatial variation in resource availability drives the differentiation of subpopulations with distinct physiological states, including dormant persister cells that can survive antibiotic challenges and lead to chronic or recurrent infections [5] [6]. Understanding these dynamics is essential for developing effective strategies against biofilm-associated infections, particularly those involving medical implants where nutrient availability is often restricted.

Architectural Foundations of Biofilm Heterogeneity

Structural Composition and Matrix Architecture

The biofilm architecture is a complex, three-dimensional arrangement comprising microbial cells and a matrix of extracellular polymeric substances. The EPS matrix typically constitutes over 90% of the biofilm's dry mass, creating a cohesive environment that immobilizes cells and facilitates adhesion to surfaces [2]. This matrix is compositionally diverse, containing:

- Exopolysaccharides (e.g., alginate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in staphylococci) providing structural scaffolding [2]

- Extracellular DNA (eDNA) contributing to structural integrity and facilitating horizontal gene transfer [7]

- Proteins and enzymes functioning in nutrient acquisition and matrix remodeling [2]

- Lipids influencing hydrophobicity and barrier functions [7]

- Inorganic ions like calcium and magnesium that cross-link polymer networks [2]

The matrix is organized into two distinct layers: an outer loosely bound EPS (LB-EPS) layer with reduced adhesive capacity, and an inner tightly bound EPS (TB-EPS) layer where 97-98% of proteins are concentrated, creating a tightly packed environment around the cells [2].

Developmental Stages Establishing Heterogeneity

Biofilm formation progresses through defined developmental stages that establish the foundation for heterogeneity:

- Initial Reversible Attachment: Free-floating planktonic cells adhere to preconditioned surfaces through weak interactions (van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions) and microbial structures like pili [1].

- Irreversible Attachment: Cells begin producing EPS, facilitating strong attachment and initiating microcolony formation [1].

- Maturation: Development of complex three-dimensional structures with characteristic architectural features like the honeycomb pattern observed in Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms [8].

- Dispersion: Controlled release of cells from the biofilm to colonize new surfaces [1].

Table 1: Key Components of the Biofilm Extracellular Matrix

| Matrix Component | Primary Functions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Exopolysaccharides | Structural scaffolding, adhesion, protection | Alginate, Psl, Pel in P. aeruginosa; PIA in staphylococci [2] |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Structural cohesion, genetic exchange, immune activation | DNA from lysed cells [7] |

| Proteins & Enzymes | Structural integrity, nutrient processing, matrix degradation | Extracellular adhesion protein in S. aureus [9] |

| Lipids | Hydrophobicity, barrier function | Not specified in search results |

| Inorganic Ions | Polymer cross-linking, matrix stabilization | Calcium, magnesium ions [2] |

Gradient-Driven Physiological Heterogeneity

Resource Gradients and Metabolic Specialization

The three-dimensional architecture of biofilms impedes uniform diffusion of molecules, leading to the formation of physical and chemical gradients that serve as primary drivers of physiological heterogeneity [3] [4]. Oxygen, often the most critical gradient, typically decreases with depth from the biofilm surface, creating stratified microenvironments with distinct redox potentials [3]. This oxygenation gradient establishes a fundamental trend in microbial physiology, favoring aerobic metabolisms near the surface and anaerobic pathways in the interior regions.

These resource gradients promote metabolic differentiation and division-of-labor within the biofilm community [3]. For instance, in Escherichia coli biofilms, cells in the anoxic lower layers ferment glucose and produce acetate, which then diffuses upward to be consumed by aerobic cells in the oxic zone [3]. This cross-feeding optimizes resource utilization and enhances the overall fitness of the community. Similar metabolic cooperation occurs in oral biofilms, where early colonizers like Streptococcus spp. consume oxygen, creating anaerobic niches that support later colonizers including periodontal pathogens [7].

Metal Ion Gradients and Their Physiological Impact

Metal availability represents another crucial dimension of gradient-induced heterogeneity, significantly influencing biofilm development and function [9]. Bacteria have evolved sophisticated regulatory systems to maintain metal homeostasis, including metal-responsive transcriptional regulators like Fur (iron), Zur (zinc), and Mur (manganese) [9]. The host employs nutritional immunity, sequestering essential metals to limit bacterial growth, which in turn triggers adaptive responses in biofilms.

Table 2: Metal-Mediated Regulation of Biofilm Formation

| Metal | Regulatory System | Observed Effect on Biofilms | Example Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron (Fe) | Fur (Ferric Uptake Regulator) | Iron limitation induces biofilm formation through increased secretion of adhesion proteins (Eap, Emp) [9] | Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa [9] |

| Zinc (Zn) | Zur (Zinc Uptake Regulator) | Zinc-regulated biofilm formation [9] | Bacillus anthracis [9] |

| Manganese (Mn) | Mur (Manganese Uptake Regulator) | Manganese uptake regulates quorum sensing and biofilm formation [9] | Burkholderia cenocepacia, Enterococcus faecalis [9] |

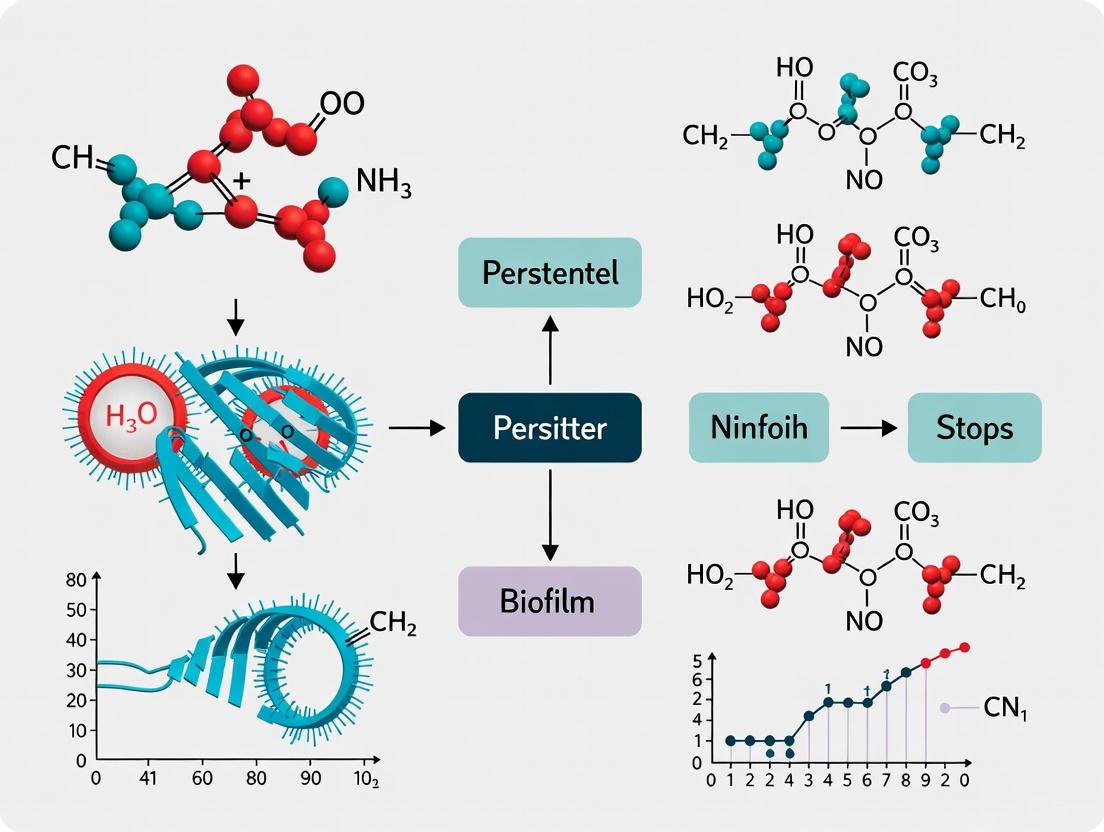

The following diagram illustrates how nutrient and metal gradients create heterogeneous microenvironments that drive physiological adaptations and persister cell formation within biofilms:

Mechanisms Linking Nutrient Gradients to Persister Formation

Physiological Basis of Persister Cells

Persisters represent a small subpopulation of bacterial cells that exhibit high tolerance to lethal doses of antibiotics without undergoing genetic resistance mutations [5]. This tolerance is non-heritable and reversible, distinguishing it from conventional antibiotic resistance. When antibiotic treatment ceases, persisters can resuscitate and regenerate a population with susceptibility profiles identical to the original one [5]. Biofilms are particularly effective at generating persisters, with frequencies 10 to 1000 times higher than observed in planktonic cultures [5].

The formation of persisters is closely linked to reduced metabolic activity and dormancy states. Since most antibiotics target active cellular processes like cell wall synthesis, protein production, and DNA replication, slowing or halting these processes provides a protective effect [5] [4]. In biofilms, nutrient gradients naturally create heterogeneous metabolic conditions, with cells in nutrient-deprived regions transitioning toward dormancy and consequently developing increased antibiotic tolerance [5] [6].

Molecular Mechanisms of Persistence

Multiple molecular mechanisms contribute to persister formation in response to nutrient gradients:

- Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Modules: These systems consist of stable toxins and unstable antitoxins. Under stress conditions, antitoxins are degraded, freeing toxins to inhibit essential processes like DNA replication and protein translation, inducing dormancy [5].

- Stringent Response: Nutrient limitation triggers (p)ppGpp signaling, which reprograms cellular metabolism away from growth and toward maintenance, promoting persistence [5].

- Stress Response Systems: DNA damage (SOS response) and oxidative stress responses activate protective mechanisms that can contribute to antibiotic tolerance [5].

- Efflux Pumps: Enhanced drug efflux activity can reduce intracellular antibiotic concentrations, though this mechanism is more associated with resistance than tolerance [5].

- Quorum Sensing: Cell-to-cell communication systems regulate collective behaviors and can influence persister formation through population-dependent signaling [5].

The following diagram illustrates the molecular pathways through which nutrient limitation triggers persister cell formation:

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Biofilm Heterogeneity

Advanced Imaging Techniques

Understanding biofilm heterogeneity requires methodologies capable of resolving structural and physiological variations across multiple spatial scales:

- Large Area Automated Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): This technique enables high-resolution imaging over millimeter-scale areas, capturing spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology during early biofilm formation. Automated scanning with machine learning-assisted image stitching allows visualization of features like flagellar coordination and honeycomb patterning in Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms [8].

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM): Provides three-dimensional imaging of biofilm architecture while preserving native structure. When combined with fluorescent staining, it reveals different microbial species occupying distinct ecological niches and the spatial organization of metabolic activity [7].

- Microfluidics with Single-Cell Microscopy: Custom microfluidic devices enable precise control of nutrient fluctuations while monitoring individual cell growth. This approach revealed that E. coli exhibits a distinct "fluctuation-adapted" physiology that enhances growth under rapid nutrient changes compared to predictions from steady-state models [10].

Molecular and Analytical Approaches

- Metabolic Flux Analysis: Using techniques like 13C metabolic flux analysis, researchers can track nutrient utilization pathways in different biofilm regions, revealing cross-feeding interactions such as acetate production in anaerobic zones and consumption in aerobic regions [3].

- Transcriptomics and Proteomics: These methods identify gene expression and protein production patterns across biofilm subpopulations, highlighting physiological adaptations to local microenvironments [4].

- Mathematical Modeling: Continuum models that couple nutrient transport with dynamics of proliferative bacteria, persisters, and EPS matrix components provide theoretical frameworks for understanding how nutrient availability controls the balance between active growth and dormancy [6].

Table 3: Methodologies for Analyzing Biofilm Heterogeneity

| Methodology | Key Applications | Technical Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Area Automated AFM | Nanoscale topography, cellular morphology, flagellar interactions [8] | High resolution under physiological conditions; nanomechanical property mapping [8] | Limited to surface features; requires specialized equipment and analysis [8] |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy | 3D architecture, spatial organization, species distribution [7] | Non-destructive optical sectioning; compatible with live-cell imaging and fluorescent probes [7] | Resolution limited by light diffraction; potential phototoxicity [7] |

| Microfluidics with Single-Cell Analysis | Growth dynamics under controlled nutrient fluctuations, physiological heterogeneity [10] | Precise environmental control; high-temporal resolution; single-cell data [10] | Technical complexity; potential surface effects on cell behavior [10] |

| Mathematical Modeling | Prediction of persister dynamics, nutrient gradient effects, treatment outcomes [6] | Integrates complex processes; enables hypothesis testing and prediction [6] | Requires parameterization and validation; simplifications may limit biological accuracy [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biofilm Heterogeneity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-Treated Glass Surfaces | Controlled hydrophobic surfaces for studying initial attachment dynamics [8] | Used in AFM studies of Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilm assembly [8] |

| Custom Microfluidic Devices | Precise control of nutrient fluctuations with single-cell imaging capability [10] | PDMS devices for E. coli growth under minute-scale nutrient oscillations [10] |

| Fluorescent Stains and Probes | Visualization of live/dead cells, metabolic activity, and specific matrix components | SYTO dyes for nucleic acids, FITC-conjugated lectins for polysaccharides [7] |

| Metal Chelators | Investigation of metal limitation effects on biofilm formation and physiology | Iron chelators inducing slime production in S. epidermidis [9] |

| Specific Nutrient Media | Creating defined nutritional environments and gradients | LB media at varying concentrations (0.1%-2%) for fluctuation experiments [10] |

| Atomic Force Microscopy Probes | High-resolution topographical imaging and nanomechanical measurements | Sharp silicon tips for visualizing bacterial flagella and EPS matrix [8] |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors | Interruption of cell-cell communication to study its role in heterogeneity | AHL analogs for blocking quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria [7] |

| MI-503 | MI-503, MF:C28H27F3N8S, MW:564.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mimopezil | Mimopezil, CAS:180694-97-7, MF:C23H23ClN2O3, MW:410.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Architectural and physiological heterogeneity in biofilms represents a fundamental survival strategy that emerges from the interaction between microbial communities and their spatially structured environments. The nutrient gradients that develop within biofilms directly drive the formation of metabolically diverse subpopulations, including antibiotic-tolerant persister cells that contribute to therapeutic failure and chronic infections. Understanding these relationships requires sophisticated methodological approaches that span from nanoscale imaging to computational modeling.

The implications of this heterogeneity extend significantly to clinical practice, particularly in the context of medical device-related infections where nutrient limitations are common. Traditional antibiotic therapies often fail because they primarily target metabolically active cells while overlooking the dormant persister populations that reside in nutrient-deprived regions of biofilms. Future therapeutic strategies may need to consider manipulating nutrient availability or targeting the molecular mechanisms that drive persistence to achieve more effective biofilm control. As research continues to unravel the complex relationships between gradient-driven heterogeneity and treatment outcomes, new opportunities will emerge for combating persistent biofilm-associated infections.

Spatial Gradients of Carbon, Oxygen, and Metabolites

In the structured environment of a microbial biofilm, the consumption of nutrients and oxygen by surface-layer cells creates chemical gradients that penetrate the depths of the community. These spatial gradients of carbon, oxygen, and metabolites are not merely a consequence of biofilm growth; they are fundamental organizers of microbial physiology and a critical driving force behind the formation of antibiotic-tolerant persister cells [3] [5]. This phenomenon presents a major challenge in treating chronic infections, as these dormant, tolerant cells are responsible for relapse and therapeutic failure [11] [5].

Understanding the mechanisms of gradient formation and their physiological consequences is essential for developing novel anti-biofilm strategies. This guide provides a technical overview of the principles, measurement methodologies, and implications of chemical gradients within biofilms, with a specific focus on their role in fostering bacterial persistence.

The Formation and Architecture of Biofilm Gradients

Fundamentals of Gradient Formation

Biofilms are structured as complex, three-dimensional communities encased in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. This matrix, composed of exopolysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular DNA, acts as a diffusion barrier, significantly hindering the free movement of molecules [3] [12]. The combination of this physical barrier and the collective metabolic activity of the microbial population establishes steep chemical gradients from the biofilm-fluid interface to the substratum.

- Oxygen Gradients: Oxygen, often the most rapidly consumed substrate, is typically depleted within the first few tens to hundreds of micrometers from the biofilm surface [3]. This creates distinct aerobic, microaerophilic, and anaerobic zones.

- Carbon and Nutrient Gradients: The availability of carbon sources and other nutrients decreases with depth, as they are consumed by cells in outer layers [3] [13].

- Metabolite Gradients: Waste products and metabolic by-products (e.g., organic acids, fermentation products) accumulate in the biofilm interior, creating additional environmental stresses [3].

The diagram below illustrates the structural and chemical heterogeneity within a mature biofilm.

Physiological Heterogeneity and Metabolic Stratification

Spatial gradients create a patchwork of microenvironments with distinct physiological states. This heterogeneity is a key survival strategy, allowing the biofilm community to utilize resources efficiently through a division-of-labor [3].

A classic example is metabolic cross-feeding in Escherichia coli biofilms. Cells in the anoxic lower layers ferment glucose and produce acetate. This acetate then diffuses upwards and serves as a carbon source for aerobic cells in the oxic zone of the biofilm [3]. This functional stratification optimizes energy production and biomass yield from the available substrates.

Quantitative Characterization of Gradients

The specific physical and chemical properties of a biofilm's environment directly influence the steepness and impact of these gradients. The table below summarizes key parameters and their quantitative effects.

Table 1: Key Parameters Influencing Biofilm Gradient Formation and Metabolic Activity

| Parameter | Impact on Gradients & Metabolism | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Surface Area | Non-linear impact on carbon metabolic rate; mass transfer limitations can cause activity to peak at a threshold (e.g., 5000-7500 m²/m³) and then decline [14]. | Study using carriers with different specific surface areas (1,900 - 12,500 m²/m³) incubated in lakes; metabolic activity measured via BIOLOG ECO microplates [14]. |

| Oxygen Concentration | Primary determinant of overall chemistry and microbial physiology; creates zones with distinct electron acceptors [3] [15]. | Metagenomic data from Baltic Sea sediments showed oxygen and salinity as the main drivers of functional gene composition [15]. |

| Carbon Source Transition | Diauxic shifts (e.g., glucose to acetate) stimulate persister formation via a ppGpp-dependent pathway [13]. | Colony biofilm assays on membranes; persisters enumerated after ofloxacin/ampicillin exposure pre- and post-glucose exhaustion [13]. |

| Carrier C:N Ratio | Correlates with diversity of nutrient transport and carbon metabolism genes in benthic environments [15]. | Large-scale spatial correlation of sediment C/N ratio with metagenomic functional profiles [15]. |

| Nutrient Limitation | Directly induces dormancy; also causes time-dependent growth arrest, indirectly increasing persistence [16]. | Individual-based modeling (IbM) simulating nutrient, oxygen, and time-dependent dormancy mechanisms [16]. |

Methodologies for Studying Gradients and Persistence

Investigating the relationship between spatial gradients and persister formation requires a combination of sophisticated techniques. The following workflow outlines an integrated experimental approach.

Experimental Protocols

Carbon Source Transition Assay in Colony Biofilms

This protocol is designed to directly test the effect of nutrient shifts on persister formation within a biofilm structure [13].

- Biofilm Growth: Grow E. coli colony biofilms on polyethersulfone (PES) membranes placed on M9 minimal agar plates containing a primary carbon source (e.g., 10-60 mM glucose).

- Monitor Growth: Aseptically remove membranes at intervals, vortex in PBS, and measure OD₆₀₀ to track growth. Exhaustion of the primary carbon source is indicated by a plateau in OD.

- Induce Transition: At specific time points before and after carbon source exhaustion, samples are taken for persister enumeration.

- Persister Measurement: Resuspend biofilm cells from membranes and expose to a high concentration of a fluoroquinolone (e.g., 10 μg/mL ofloxacin) or a β-lactam (e.g., 750 μg/mL ampicillin) for 5 hours.

- Enumeration: Serially dilute the antibiotic-treated suspension and spot on LB agar plates. Count colony-forming units (CFU) after incubation. Persisters are the cells that survive this antibiotic exposure.

Metabolic Activity Profiling via BIOLOG ECO Microplates

This method assesses the functional metabolic diversity of biofilms grown under different conditions, such as on carriers with varying specific surface areas [14].

- Biofilm Collection and Homogenization: Separate biofilm from its carrier via ultrasonic oscillation and suspend in sterile physiological saline (0.85% NaCl).

- Standardization: Dilute the biofilm suspension until the optical density at 590 nm (OD₅₉₀) reaches 0.05.

- Inoculation and Incubation: Transfer 150 μL of the standardized suspension into each well of a BIOLOG ECO microplate, which contains 31 different carbon sources and a control well. Incubate at 25°C in the dark for up to 7 days.

- Data Acquisition: Measure the OD₅₉₀ of each well every 12-24 hours using a microplate reader.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the Average Well Color Development (AWCD) for each plate:

AWCD = Σ(Ci - R) / n, whereCiis the absorbance of a sample well,Ris the absorbance of the control well, andnis the number of substrates (31). - Fit the AWCD over time to a logistic growth curve to model metabolic activity kinetics.

- Calculate diversity indices like the Shannon-Wiener index (H') to assess the community's metabolic versatility.

- Calculate the Average Well Color Development (AWCD) for each plate:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their applications in biofilm gradient and persister research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Biofilm Gradient Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| BIOLOG ECO Microplates | Community-level physiological profiling; measures carbon source utilization potential of a biofilm community [14]. | Contains 31 different carbon sources; tetrazolium dye color change indicates metabolic activity. |

| Polyethersulfone (PES) Membranes | Support surface for growing colony biofilms, allowing controlled nutrient delivery from underlying agar [13]. | 0.2 μm pore size, 25 mm diameter; inert and non-degradable. |

| M9 Minimal Salts Agar | Defined medium for biofilm growth, essential for conducting controlled carbon transition experiments [13]. | Allows precise control over carbon source type and concentration. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM) | Non-invasive, real-time 3D visualization of biofilm architecture, cell viability, and spatial organization using fluorescent tags [7] [12]. | Enables optical sectioning of live biofilms without disruption. |

| Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | Provides nanomechanical data (adhesion, elasticity) of biofilm surfaces and single cells [12]. | Can operate in liquid environments, providing physiologically relevant data. |

| Microfluidic Devices | Simulates dynamic fluid flow and nutrient conditions; allows high-resolution study of biofilm heterogeneity and antimicrobial penetration [16] [12]. | Enables precise environmental control and real-time imaging. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 / CRISPRi | Targeted gene editing (knockout) or interference (knockdown) to investigate function of specific genes in persistence (e.g., TA modules, ppGpp synthases) [11] [12]. | Provides precise molecular tools for mechanistic studies. |

| Minocycline hydrochloride | Minocycline Hydrochloride | High-purity Minocycline Hydrochloride for research. Explore its antibiotic and non-antibiotic mechanisms in biomedical studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Mirogabalin Besylate | Mirogabalin Besylate|High-Purity α2δ Ligand | Mirogabalin besylate is a novel, selective α2δ ligand for neuropathic pain research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Connecting Gradients to Persister Cell Formation

The heterogeneous microenvironments created by spatial gradients are a primary source of persister cells in biofilms. The following diagram synthesizes the major mechanisms linking these gradients to phenotypic tolerance.

Key Mechanistic Insights

- Nutrient Transitions as a Trigger: The shift from a preferred carbon source (like glucose) to a secondary one (like acetate) as it is depleted in the biofilm is a potent stimulus for persister formation. This diauxic transition activates the stringent response via the signaling molecule (p)ppGpp, which orchestrates a massive reprogramming of cellular metabolism towards a dormant, tolerant state [13].

- Dormancy and Active Tolerance: A prevailing hypothesis is that gradient-driven starvation pushes cells into a dormant state with drastically reduced growth and metabolic activity, rendering them insensitive to antibiotics that target active cellular processes [11] [5]. However, persistence is not synonymous with dormancy. Active mechanisms, such as efflux pumps and stress responses (e.g., oxidative stress response), also contribute to tolerance in biofilm subpopulations [5].

- The Role of Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Modules: Under stress conditions, degradation of labile antitoxins leads to the release of free toxins. These toxins can disrupt essential processes like translation and replication, thereby inducing a dormant state that is a hallmark of many persister cells [11] [5].

Spatial gradients of carbon, oxygen, and metabolites are non-genetic, self-organizing principles that generate phenotypic heterogeneity and antibiotic tolerance in biofilms. The deep, nutrient-limited, and anaerobic zones of a biofilm serve as reservoirs for dormant persister cells, which are largely responsible for the recalcitrance of chronic infections.

Future research and therapeutic development must move beyond traditional antimicrobials that target growing cells. Effective strategies will require a dual approach: first, disrupting the gradient structure itself, perhaps by enhancing diffusion or applying metabolic inhibitors that target multiple physiological states simultaneously; and second, directly eradicating the persister subpopulation by exploiting their unique physiology, such as their low metabolic state or specific stress pathways. A deep, quantitative understanding of biofilm gradients is therefore not just an academic pursuit but a critical pathway to overcoming one of the most significant challenges in modern infectious disease management.

The stringent response, a universal bacterial stress adaptation mechanism, is orchestrated by the signaling molecules guanosine tetraphosphate and pentaphosphate, collectively known as (p)ppGpp. This master regulator extensively rewires bacterial physiology by reprogramming transcriptional networks and cellular metabolic processes. Within structured biofilm communities, nutrient gradients create heterogeneous microenvironments that trigger (p)ppGpp accumulation, leading to bacterial growth arrest and promoting the formation of antibiotic-tolerant persister cells. This technical review examines the core molecular mechanisms of (p)ppGpp signaling, with particular emphasis on its role as a critical mediator connecting nutrient limitation to persister formation in biofilms—a key driver of chronic and recurrent infections. We synthesize current experimental evidence, quantitative relationships, and methodological approaches to provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for investigating this fundamental bacterial survival pathway.

The stringent response represents one of the most crucial global regulatory systems in bacteria, enabling rapid adaptation to environmental stresses, particularly nutrient limitation. Central to this response are the hyperphosphorylated guanosine nucleotides ppGpp (guanosine pentaphosphate) and pppGpp (guanosine tetraphosphate), collectively termed (p)ppGpp and historically known as "magic spot". These signaling molecules function as bacterial alarmones that coordinate cellular physiology by redirecting resources from proliferation to maintenance and survival [17].

In clinical contexts, (p)ppGpp signaling gains particular significance due to its direct involvement in bacterial pathogenesis, host invasion, and antibiotic tolerance [17]. The stringent response is activated not only during nutrient starvation but also in response to diverse environmental cues including oxygen variation, pH downshift, osmotic shock, temperature shift, and even light exposure in phototrophic bacteria [17]. This versatile signaling system enables bacterial pathogens to withstand antibiotic therapy and establish persistent infections, making it a compelling target for novel antimicrobial strategies.

Molecular Mechanisms of (p)ppGpp Synthesis and Regulation

Enzymatic Control of (p)ppGpp Homeostasis

Cellular (p)ppGpp levels are primarily regulated by enzymes belonging to the RelA/SpoT homolog (RSH) family, which are highly conserved across bacterial species [17]. These enzymes can be categorized based on their domain architecture and functional capabilities:

- Long RSH enzymes: Bifunctional proteins containing both synthetase and hydrolase domains. In Gamma-proteobacteria like Escherichia coli, this function is divided between RelA (primarily synthetase activity) and SpoT (weak synthetase but strong hydrolase activity) [17] [18].

- Short RSH enzymes: Monofunctional enzymes including small alarmone synthetases (SAS) and small alarmone hydrolases (SAH) that provide additional regulatory layers in certain bacterial species [17].

The regulation of (p)ppGpp synthesis is triggered by specific environmental stimuli. RelA is activated by uncharged tRNA molecules that accumulate during amino acid starvation, while SpoT responds to diverse stresses including fatty acid limitation, carbon starvation, and oxidative stress [17] [19].

Table 1: Enzymatic Regulators of (p)ppGpp Homeostasis Across Bacterial Species

| Enzyme | Organism Type | Primary Function | Activating Signals |

|---|---|---|---|

| RelA | Gamma-proteobacteria | (p)ppGpp synthesis | Uncharged tRNA (amino acid starvation) |

| SpoT | Gamma-proteobacteria | (p)ppGpp hydrolysis (primary); weak synthesis | Fatty acid limitation, carbon starvation, oxidative stress |

| Rel | Gram-positive bacteria, Mycobacteria | Bifunctional (synthesis and hydrolysis) | Multiple nutrient stresses |

| SAS (Small Alarmone Synthetases) | Various bacteria | (p)ppGpp synthesis | Specialized environmental cues |

| SAH (Small Alarmone Hydrolases) | Various bacteria | (p)ppGpp hydrolysis | Cellular (p)ppGpp concentration |

Molecular Effectors and Transcriptional Reprogramming

(p)ppGpp exerts its profound physiological effects through direct interactions with key cellular targets:

- RNA polymerase (RNAP): In Gammaproteobacteria, (p)ppGpp binds directly to the RNAP, often with its cofactor DksA, to differentially regulate transcription. This binding induces allosteric changes that inhibit stable RNA synthesis while activating amino acid biosynthesis and stress response genes [19] [18].

- Transcription factors: (p)ppGpp can modulate the activity of various transcription factors, including the GTP-sensing regulator CodY, thereby indirectly influencing gene expression [18].

- Metabolic enzymes: Direct inhibition of enzymes involved in nucleotide synthesis (e.g., DNA primase) and other central metabolic processes [17].

The diagram below illustrates the core (p)ppGpp signaling pathway and its physiological outcomes:

Quantitative Relationships in (p)ppGpp Signaling

Graded Nature of the Stringent Response

Recent research has revealed that the stringent response operates not as a binary on/off switch but as a graded system where (p)ppGpp accumulation and transcriptional responses are proportional to stress severity [19]. This continuum model explains how bacteria can fine-tune their adaptation to varying degrees of nutrient limitation.

Table 2: Dose-Dependent Effects of (p)ppGpp Accumulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14

| SHX Concentration | Stringent Response Level | (p)ppGpp Increase (Fold) | Growth Rate (Doublings/Hour) | Differentially Expressed Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 µM | Mild | 1.33x | 0.40 | 227 (~4% of genome) |

| 500 µM | Intermediate | 1.39x | 0.26 | 1,197 (~20% of genome) |

| 1000 µM | Acute | 1.48x | Severe perturbation | 1,508 (~25% of genome) |

The quantitative relationship between (p)ppGpp levels and growth rate follows a strong negative correlation (R² = 0.95), demonstrating the precision of this regulatory system [19]. Transcriptomic analysis reveals that increasing (p)ppGpp concentrations engage cellular processes in a layer-by-layer manner, with more severe stress conditions recruiting additional genes into the response network [19].

Phenotypic Outcomes of (p)ppGpp Signaling

The functional consequences of (p)ppGpp accumulation manifest differently across bacterial species and environmental contexts:

Table 3: Phenotypic Consequences of (p)ppGpp Signaling Across Bacterial Species

| Bacterial Species | Phenotypic Outcomes | Relationship to Persistence |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Inhibition of DNA replication; Multidrug tolerance in biofilms; Transient growth arrest | Direct role in persister formation during nutrient transitions [17] [13] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Dose-dependent motility suppression; Enhanced biofilm formation; Antibiotic tolerance | Promotes antimicrobial tolerance under biofilm conditions [19] |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | Copositive regulation with DksA for motility, antibiotic resistance, oxidative stress tolerance | Synergistic actions with other regulators in persistence [18] |

| Clavibacter michiganensis | Reduced ribosomal gene expression; Enhanced biofilm synthesis; Increased production of cell-wall degrading enzymes | Mediates virulence and survival in host environment [20] |

| Pseudomonas putida | Stimulation of biofilm dispersal under nutrient limitation | Coordinates exit from biofilm lifestyle [21] |

Methodologies for Investigating (p)ppGpp-Dependent Persister Formation

Experimental Induction of Stringent Response

Researchers have developed multiple approaches to induce and study (p)ppGpp-mediated persister formation:

Serine Hydroxamate (SHX) Treatment

- Principle: SHX is a serine analog that inhibits seryl-tRNA synthetase, causing accumulation of uncharged tRNA and activating RelA-dependent (p)ppGpp synthesis [19].

- Protocol:

- Grow P. aeruginosa PA14 cultures to exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ~0.2-0.4)

- Add SHX at concentrations ranging from 10-1000 µM to induce varying stringent response levels

- Incubate for 30 minutes at growth temperature

- Measure (p)ppGpp accumulation via thin-layer chromatography or HPLC

- Assess persister levels by antibiotic challenge assays

- Applications: Ideal for studying dose-dependent effects of (p)ppGpp on transcriptomics and persister formation [19].

Temperature-Sensitive valS Allele System

- Principle: Utilizing a temperature-sensitive valyl-tRNA synthetase (valSts) to controllably induce tRNA charging limitation and (p)ppGpp accumulation [22].

- Protocol:

- Grow E. coli MG1655valSts at permissive temperature (30°C)

- Shift to semi-permissive temperature (36.6-37°C) to partially inactivate ValS

- Monitor ppGpp levels over time (peaks at ~10 minutes post-shift)

- Assess persister frequency by antibiotic challenge at different time points

- Applications: Enables single-cell analysis of persister formation, survival, and resuscitation using live microscopy [22].

Carbon Source Transition Model

- Principle: Diauxic shifts between preferred and secondary carbon sources naturally induce (p)ppGpp accumulation and persister formation [13].

- Protocol:

- Grow E. coli colony biofilms on membranes placed on M9 minimal agar with primary carbon source

- Monitor growth until near-exhaustion of primary carbon source (FCOD₆₀₀ ~30)

- Verify carbon source depletion with glucose assay kits

- Measure persister levels before and after carbon source exhaustion

- Compare with relA/spoT mutants to confirm (p)ppGpp dependence

- Applications: Models nutrient gradient effects in biofilms; identifies persister formation pathways relevant to in vivo conditions [13].

The experimental workflow for studying nutrient transition-induced persistence is illustrated below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Investigating (p)ppGpp-Dependent Persister Formation

| Reagent/Condition | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Serine Hydroxamate (SHX) | Chemical inducer of amino acid starvation | Dose-dependent induction of stringent response [19] |

| valSts (temperature-sensitive valS) | Genetic system for controlled tRNA charging limitation | Single-cell analysis of persister formation dynamics [22] |

| Colony biofilm system with PES membranes | Controlled nutrient delivery and transition studies | Modeling nutrient gradient effects in biofilms [13] |

| relA/spoT deletion mutants | Genetic dissection of (p)ppGpp synthesis pathways | Determining pathway specificity in persister formation [17] [13] |

| RpoS-mCherry fusion | Fluorescent reporter for (p)ppGpp activation | Single-cell tracking of stringent response activation [22] |

| QUEEN-7µ ATP sensor | FRET-based ATP concentration measurement | Correlating metabolic state with persistence [22] |

| TA promoter-YFPunstable fusions | Reporter for toxin-antitoxin system activation | Monitoring stochastic TA activation in single cells [22] |

| HPLC / TLC methods | Quantitative (p)ppGpp measurement | Precise quantification of alarmone levels [19] |

| Mivebresib | Mivebresib, CAS:1445993-26-9, MF:C22H19F2N3O4S, MW:459.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Setileuton tosylate | Setileuton tosylate, CAS:1137737-87-1, MF:C29H25F4N3O7S, MW:635.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

(p)ppGpp in Biofilm Persistence and Therapeutic Implications

Nutrient Gradients and Heterogeneous Persister Formation

Within biofilms, nutrient availability follows spatial gradients that create heterogeneous microenvironments. Cells in nutrient-depleted regions experience stress conditions that trigger (p)ppGpp accumulation, leading to heterogeneous persister formation throughout the biofilm structure [17] [6]. Mathematical modeling confirms that nutrient limitation produces a high and sustained proportion of persister cells even when overall biomass is reduced, whereas nutrient-rich conditions support reversion to proliferative growth [6].

The (p)ppGpp-mediated persister formation in biofilms involves coordinated regulation of multiple cellular processes:

- Metabolic reprogramming: Downregulation of energy-intensive processes including ribosome biogenesis, nucleotide synthesis, and oxidative phosphorylation [19]

- Toxin-antitoxin system modulation: Activation of specific TA modules that promote dormancy in subpopulations of cells [17] [23]

- Cell envelope modifications: Changes in membrane permeability and transport systems that reduce antibiotic uptake [17]

- DNA supercoiling regulation: Inhibition of DNA gyrase leading to reduced DNA replication and transcription [17]

Interplay with Other Persistence Mechanisms

(p)ppGpp does not function in isolation but interacts with multiple cellular pathways to regulate persistence. Research in E. coli has revealed complex genetic interactions between (p)ppGpp and 15 known persister genes, which can be categorized into five relationship types: dependent, positive reinforcement, antagonistic, epistasis, and irrelevant [23]. These interactions are further modulated by bacterial culture age, antibiotic class, and cell concentration, highlighting the contextual nature of persistence mechanisms.

Notably, the relationship between (p)ppGpp and persistence is not always straightforward. Single-cell studies have demonstrated that while high population-level (p)ppGpp correlates with increased persister frequencies, there is no direct correlation between (p)ppGpp levels and antibiotic tolerance at the single-cell level, emphasizing the importance of stochasticity in persister formation [22].

Therapeutic Perspectives and Targeting Strategies

The central role of (p)ppGpp in bacterial persistence makes it an attractive target for novel therapeutic interventions. Several strategic approaches have emerged:

- Direct (p)ppGpp synthesis inhibitors: Small molecules that target RelA/SpoT enzymes to prevent alarmone accumulation during stress [17]

- Stringent response disruptors: Compounds that interfere with (p)ppGpp-RNAP interactions or downstream signaling events [17]

- Combination therapies: Anti-persister agents that target (p)ppGpp-mediated pathways alongside conventional antibiotics [11]

- Nutrient modulation approaches: Strategies that manipulate environmental conditions to prevent persistent state induction [6]

Recent evidence suggests that targeting (p)ppGpp signaling may enhance the efficacy of conventional antibiotics against biofilm-associated infections, potentially addressing the clinical challenge of chronic and recurrent infections [17] [11]. As our understanding of the nuanced role of (p)ppGpp in bacterial pathogenesis continues to evolve, so too will opportunities for therapeutic intervention in persistent infections.

The Role of Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Modules in Stress-Induced Dormancy

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are genetic elements ubiquitous in bacteria and archaea, functioning as sophisticated stress-responsive survival circuits. This review delves into the molecular mechanisms of type II TA modules, emphasizing their critical role in inducing bacterial dormancy and antibiotic tolerance, particularly within the nutrient-graded environments of biofilms. Within biofilms, heterogenous nutrient distribution creates micro-niches that actively trigger TA systems, leading to a dormant, persister subpopulation responsible for chronic infections and therapeutic failures. We synthesize current understanding of TA system operation, present quantitative data on their distribution and function, and provide detailed methodologies for their study. The focus on biofilm nutrient gradients provides a critical context for understanding persister formation, offering insights for developing novel anti-persister therapeutic strategies.

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are genetic modules composed of a stable toxin protein and a labile antitoxin (a protein or RNA) that neutralizes the toxin under normal growth conditions [24]. Under stress conditions, such as nutrient limitation, antibiotic exposure, or oxidative stress, the antitoxin is rapidly degraded, freeing the toxin to act on its cellular target and induce a state of growth arrest and dormancy [5]. This physiological state is characterized by a drastic reduction in metabolism, protecting the bacterial cell from stressors that typically target active cellular processes.

This stress-induced dormancy is intrinsically linked to the formation of bacterial persisters—a small subpopulation of genetically susceptible cells that exhibit multidrug tolerance without acquired resistance [11] [25]. Persisters are phenotypically variant, non-growing, or slow-growing cells that can survive high doses of antibiotics and regrow once the antibiotic pressure is removed, leading to recurrent and chronic infections [11] [5]. The ability of TA systems to orchestrate this reversible dormancy positions them as a cornerstone of bacterial persistence, especially in structured environments like biofilms where stress gradients are common.

Classification and Molecular Mechanisms of Type II TA Systems

Among the various types of TA systems, type II is the most well-characterized class. These systems are defined by proteinaceous toxins and antitoxins that form a stable complex. Under normal conditions, the antitoxin binds to and neutralizes the toxin. Environmental stressors trigger the degradation of the antitoxin by specific proteases, unleashing the toxin to act on its target [24].

The table below summarizes the primary functional targets and roles of key type II TA systems implicated in bacterial persistence.

Table 1: Key Type II Toxin-Antitoxin Systems and Their Functions

| TA System | Toxin Target & Mechanism | Primary Role in Persistence | Representative Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| VapBC | Ribonuclease activity; inhibits protein synthesis [26] | Dormancy induction, stress response, biofilm formation [24] [26] | Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis [26] |

| MazEF | Ribonuclease activity; cleaves cellular mRNA [24] | Dormancy induction, programmed cell death [24] | E. coli, M. tuberculosis [24] |

| RelBE | Ribonuclease activity; inhibits protein translation [24] | Dormancy induction, stringent response [24] | E. coli, numerous pathogens [24] |

| HigBA | Ribonuclease activity [24] | Dormancy induction, biofilm formation [24] | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, E. coli |

| ParDE | DNA gyrase poison; inhibits DNA replication [24] | Dormancy induction, plasmid maintenance [24] | E. coli, P. aeruginosa |

| CcdAB | DNA gyrase poison; inhibits DNA replication [24] | DNA repair, dormancy induction [24] | E. coli |

| DarTG | ADP-ribosyltransferase; modifies DNA [24] | DNA repair pathways [24] | E. coli |

The molecular interplay within a type II TA system can be visualized as a regulatory circuit that responds to external stress. The following diagram illustrates the core pathway of stress-induced dormancy via a type II TA module.

TA Systems, Nutrient Gradients, and Persister Formation in Biofilms

The biofilm microenvironment is characterized by chemical and nutrient gradients that arise from the consumption of nutrients and oxygen by cells in the outer layers and the limited diffusion of these molecules through the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix [5]. This creates a heterogeneous structure with distinct micro-niches: nutrient-replete, fast-growing cells at the biofilm periphery, and nutrient-deprived, slow-growing or non-growing cells in the interior core.

This physiological heterogeneity is a primary driver of persister formation within biofilms. Bacteria residing in the nutrient-limited interior experience starvation stress, which serves as a key environmental trigger for the activation of TA systems [5]. The subsequent induction of dormancy in these subpopulations renders them highly tolerant to antibiotics. It is estimated that biofilms can contain 10 to 1000 times more persisters than their planktonic counterparts, explaining the recalcitrance of biofilm-associated infections to antimicrobial treatment [5].

The connection between nutrient gradients, TA system activation, and the resulting population heterogeneity is summarized in the following workflow.

Quantitative Analysis of TA Systems in Pathogens

The abundance and conservation of TA systems vary across bacterial pathogens, reflecting their adaptation to different environmental niches and stress challenges. The table below compiles quantitative data on the distribution of type II TA families in several clinically relevant bacteria, highlighting their potential role in persistence and virulence.

Table 2: Quantitative Distribution of Type II TA Systems in Bacterial Pathogens

| Bacterial Species | VapBC Count | MazEF Count | RelBE Count | Other Key Systems | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | ~50 subfamilies [26] | ~10 types [26] | ~3 types [26] | ParDE, DarTG | [26] |

| Escherichia coli | Present [24] | Present (e.g., MazF) [24] | Present (e.g., RelE) [24] | HigBA, YafQ-DinJ | [24] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Present (e.g., VapC) [24] | Present | Present | HigBA, ParDE | [24] [11] |

| Methanocaldococcus jannaschii | Present (VapB-VapC) [24] | - | - | - | [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating TA Systems

Studying TA systems requires a multidisciplinary approach combining molecular biology, microbiology, and biochemical techniques. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments used to characterize TA system function and their role in persistence.

Protocol: Assessing Persister Levels via Antibiotic Kill Curves

Purpose: To quantify the fraction of antibiotic-tolerant persister cells in a bacterial population, such as one derived from a biofilm [11].

Methodology:

- Culture Preparation: Grow the bacterial strain to the desired phase (e.g., stationary phase, or disaggregate a mature biofilm). For biofilms, grow them in a suitable model (e.g., Calgary biofilm device, flow cell) for 3-5 days.

- Antibiotic Exposure: Expose the bacterial population to a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., 100x MIC of a fluoroquinolone or an aminoglycoside). Ensure the antibiotic concentration is sufficient to kill all growing cells.

- Viability Counting: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0h, 3h, 6h, 24h), remove aliquots, serially dilute them, and plate them on antibiotic-free agar plates.

- Data Analysis: Count the colony-forming units (CFU) after incubation. A biphasic kill curve—a rapid initial drop in viability followed by a plateau—indicates the presence of a persister subpopulation. The CFU count at the plateau represents the persister frequency.

Protocol: Molecular Docking of TA Complexes

Purpose: To predict and analyze the binding interactions and stability between toxin and antitoxin proteins, which can reveal the functional impact of mutations [26].

Methodology:

- Protein Structure Preparation: Obtain 3D structures of the toxin and antitoxin proteins from experimental data (e.g., PDB) or generate homology models using tools like AlphaFold.

- Molecular Docking: Use a docking program such as HADDOCK 2.4 (High Ambiguity Driven biomolecular DOCKing) to model the TA complex.

- Define active and passive residues based on known interaction sites or mutagenesis data.

- HADDOCK will generate an ensemble of possible complex structures.

- Analysis of Docking Results: Analyze the generated models using key parameters:

- HADDOCK Score: A combined energy score where more negative values indicate stronger binding affinity.

- RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation): Measures the structural deviation of the complex; lower values indicate a more stable complex.

- Van der Waals Energy & Electrostatic Energy: Contributions from different intermolecular forces.

- Buried Surface Area (BSA): The surface area hidden upon complex formation; larger BSA often correlates with stronger binding.

- Validation: Compare docking results between wild-type and mutant proteins (e.g., M. tuberculosis vs. M. bovis VapC3) to infer the functional consequences of sequence variations [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents, tools, and their applications for researching TA systems and persistence.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TA System and Persister Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| HADDOCK 2.4 Software | Biomolecular docking to model protein-protein interactions [26] | Predicting binding stability of VapB-VapC complex in M. tuberculosis [26] |

| AlphaFold | Protein structure prediction from amino acid sequence [26] | Generating 3D models of toxin proteins for docking studies [26] |

| UCSF ChimeraX | Molecular visualization and analysis [26] | Visualizing and comparing structural models of TA complexes [26] |

| pNDM-220 Vector | Plasmid for controlled gene expression [11] | Overexpressing VapC toxin to induce growth arrest in E. coli [11] |

| Calgary Biofilm Device | High-throughput cultivation of biofilms [5] | Generating standardized biofilm samples for antibiotic tolerance assays [5] |

| Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics | Inducers of DNA damage and SOS response [25] | Selecting for and studying persisters in biofilm populations [25] |

| MK2-IN-1 hydrochloride | MK2-IN-1 hydrochloride, MF:C27H26Cl2N4O2, MW:509.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ibrexafungerp | Ibrexafungerp | Ibrexafungerp is a first-in-class triterpenoid antifungal for research. It inhibits glucan synthase. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Toxin-antitoxin systems are master regulators of bacterial stress response, directly linking environmental cues like nutrient scarcity in biofilms to the phenotypic switch into a dormant, persistent state. The structured heterogeneity of biofilms provides an ideal environment for the stochastic and triggered activation of these modules, creating a reservoir of antibiotic-tolerant cells that drive chronic and relapsing infections. A deep understanding of the specific TA systems activated by biofilm nutrient gradients, their molecular targets, and their regulatory networks is paramount. Future research must leverage the experimental frameworks and tools outlined here to dissect these pathways, with the ultimate goal of identifying and developing novel therapeutic agents that can effectively eradicate persister cells and resolve stubborn biofilm infections.

Metabolic Transitions and Diauxic Shifts as Persister Triggers

Bacterial persisters, a subpopulation of cells capable of surviving antibiotic treatment without genetic mutation, pose a significant challenge in treating chronic and biofilm-associated infections. This technical guide explores the central role of metabolic transitions, specifically diauxic shifts, as critical environmental triggers for persister cell formation. Within the context of biofilm biology, nutrient gradients create heterogeneous microenvironments that promote a bet-hedging strategy where subpopulations enter a dormant, persistent state. We detail the molecular mechanisms underpinning this phenomenon, summarize key quantitative findings, provide experimental methodologies for studying nutrient-induced persistence, and visualize the core signaling pathways. This resource aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge and technical protocols necessary to advance therapeutic strategies against persistent infections.

Bacterial persisters are genetically susceptible, slow-growing or non-growing phenotypic variants that survive exposure to bactericidal antibiotics and can regrow once the stress is removed [11]. These cells are now recognized as a major contributor to chronic and recurrent infections, including those associated with medical implants and cystic fibrosis [27] [11]. While persisters can form stochastically, a significant body of evidence demonstrates that environmental cues, particularly nutrient availability and metabolic shifts, are potent inducers of this transient, high-tolerance state [13].

In structured environments like biofilms, bacteria encounter steep nutrient gradients. Cells at the periphery consume preferred nutrients, leaving less favorable substrates for cells in the interior [13]. This heterogeneity is a hallmark of the biofilm lifestyle and creates ideal conditions for persister formation. The transition from one carbon source to another, known as a diauxic shift, has been specifically identified as a metabolic stressor that stimulates a persister formation pathway in Escherichia coli biofilms [13]. Understanding these nutrient-dependent mechanisms is therefore crucial for the development of more effective treatments for persistent biofilm infections, framing the core thesis that nutrient gradients are a fundamental environmental driver of persister formation.

Molecular Mechanisms Linking Metabolic Shifts to Persistence

The bacterial response to nutrient transitions is a highly coordinated process involving key signaling molecules and genetic regulators that ultimately lead to growth arrest and antibiotic tolerance.

The Central Role of ppGpp and the Stringent Response

The alarmone guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) serves as a central mediator of bacterial persistence in response to nutrient stress [28] [13]. During nutrient limitation or carbon source transitions, ppGpp is synthesized by RelA and SpoT. This alarmone dramatically reprograms cellular metabolism by binding to RNA polymerase and activating stress response sigma factors like RpoS, leading to the downregulation of energy-intensive processes such as DNA replication, protein synthesis, and cell division [28]. This reallocation of resources induces a state of dormancy or reduced metabolic activity, which is the hallmark of persister cells. Data from both planktonic and biofilm studies confirm that ppGpp is indispensable for persister formation in response to diauxic shifts [13].

Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems and Growth Arrest

Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) systems are tightly linked to persistence and are often activated downstream of the ppGpp-mediated stringent response [28]. These systems typically consist of a stable toxin that disrupts an essential cellular process (e.g., translation) and a labile antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin. Under stress conditions, proteases like Lon are activated, leading to the degradation of the antitoxin and freeing the toxin to act. Key TA systems implicated in persistence include:

- MqsR/MqsA: The MqsR toxin cleaves mRNA at a 5'-GCU site, effectively shutting down translation and inducing dormancy [28].

- TisB/IstR-1: The TisB toxin decreases the proton motive force and ATP levels, rendering the cell dormant and tolerant to multiple antibiotic classes [28].

While overexpression of many toxins increases persistence, deletion of specific TA pairs, such as mqsRA and tisAB-istR, has been shown to reduce persister numbers, confirming their functional role [28].

Nutrient Transitions as a Specific Trigger

Research has demonstrated that the exhaustion of a primary carbon source (e.g., glucose) and the subsequent transition to a secondary carbon source is a potent stimulus for persister formation in E. coli biofilms [13]. This diauxic transition activates a pathway dependent on ppGpp and specific nucleoid-associated proteins (NAPs) like FIS and HU. The proposed mechanistic cascade is as follows: nutrient transition → ppGpp accumulation → activation of NAPs → expression/activation of toxin components from TA systems → growth arrest and persistence. This pathway highlights how a common metabolic event in structured communities can directly lead to the formation of antibiotic-tolerant cells.

The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathway from nutrient transition to persister cell formation.

Quantitative Data on Nutrient-Induced Persistence

Experimental data quantifying persister formation in response to metabolic stresses is critical for understanding the phenomenon. The following table consolidates key quantitative findings from investigations into diauxic shifts and carbon source transitions.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Persister Formation Induced by Metabolic Transitions

| Organism | Metabolic Transition / Condition | Key Genetic Factors | Effect on Persistence (Fold Change) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Diauxic carbon shift in biofilms | Wild-type | Significant increase post-glucose exhaustion | [13] |

| E. coli | Diauxic carbon shift in biofilms | ΔrelA (ppGpp synthase) | Elimination of transition-induced persistence | [13] |

| E. coli | Diauxic carbon shift in biofilms | Δfis, Δhu (NAPs) | Decreased persistence | [13] |

| E. coli | Overproduction of RelE toxin | N/A | Up to 10,000-fold increase | [28] |

| E. coli | Isolation of dormant cells via FACS | — | 20-fold greater persistence to ofloxacin | [28] |

The data underscore that diauxic shifts are a potent trigger for persistence, a process heavily dependent on the ppGpp pathway and its downstream effectors. The dramatic increase in persistence upon toxin overproduction further supports the involvement of TA systems, which are often regulated by these central metabolic signals.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Metabolic Persistence

To study persister formation in the context of nutrient transitions, robust and reproducible experimental methodologies are required. Below is a detailed protocol for assessing persister levels in response to a diauxic shift in E. coli biofilms, based on established methods [13].

Biofilm Growth and Carbon Transition Assay

Key Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: E. coli MG1655 (wild-type and relevant mutants, e.g., ΔrelA).

- Growth Media: M9 minimal salts medium, supplemented with a primary carbon source (e.g., 15-60 mM glucose).

- Solid Support: Polyethersulfone (PES) membranes (0.2 µm pore size, 25 mm diameter).

- Agar Plates: M9 minimal agar plates containing the desired carbon source(s).

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow an overnight culture of the target strain in M9 media with a low concentration of glucose (e.g., 10 mM).

- Biofilm Initiation: Dilute the overnight culture to an OD600 of 0.01 in fresh M9 media with 15 mM carbon content. Inoculate 100 µL aliquots onto sterile PES membranes placed on M9 minimal agar plates containing a higher concentration of glucose (e.g., 60 mM).

- Growth Monitoring: Incubate plates at 37°C. Periodically aseptically remove membranes, vortex in PBS, and measure OD600 to monitor growth. Growth is reported as Fold Change in OD600 (FCOD600).

- Inducing Diauxic Shift: Persister measurements are taken at two critical points:

- Before glucose exhaustion: At FCOD600 ~6.

- After glucose exhaustion: At FCOD600 ~30. Glucose exhaustion can be confirmed using a commercial glucose assay kit.

- Persister Measurement:

- Harvest biofilm cells from membranes at the specified time points.

- Treat the cell suspension with a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., 10 µg/mL ofloxacin or 750 µg/mL ampicillin) for 5 hours. The antibiotic concentration must be on the second, concentration-independent phase of the kill curve.

- After antibiotic exposure, serially dilute the cells, spot onto drug-free LB agar plates, and incubate overnight to enumerate Colony Forming Units (CFUs).

- The number of CFUs remaining after 5 hours of antibiotic exposure represents the persister cell count.

The experimental workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents for executing the described experiments, along with their critical functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Nutrient-Dependent Persistence

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| PES Membranes | Provides a solid, non-invasive surface for growing colony biofilms. | Pall Corporation, 0.2 µm pore size, 25 mm diameter. |

| M9 Minimal Salts | Defined minimal medium base for precise control of nutrient availability. | Allows specific supplementation with carbon sources. |

| Carbon Sources (Glucose, etc.) | To create controlled nutrient environments and induce diauxic shifts. | Use high-purity grades for consistent results. |

| Amplex Red Glucose Assay Kit | Quantitatively measure glucose concentration in the biofilm environment. | Critical for confirming the point of carbon source exhaustion. |

| Bactericidal Antibiotics (Ofloxacin, Ampicillin) | To kill non-persister cells and selectively enumerate the persister population. | Concentration must be optimized to be on the second phase of the kill curve. |

| Flow Cytometer | Analyze and sort bacterial subpopulations based on metabolic activity (e.g., using GFP reporters). | Can be used with ribosomal promoters to isolate dormant cells [28]. |

Discussion and Therapeutic Implications

The direct link between metabolic transitions and bacterial persistence provides a framework for understanding why chronic infections are so difficult to eradicate. Biofilms, with their inherent nutrient gradients, are factories for generating persister cells through the ppGpp-dependent pathway detailed above [13] [6]. This mechanistic understanding opens up new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Rather than relying solely on traditional antibiotics that target active cellular processes, novel strategies are being explored. These include:

- Preventing Persister Formation: Targeting the ppGpp signaling pathway or TA systems to block the entry into dormancy [27].

- Eradicating Dormant Persisters: Using compounds that disrupt membrane integrity or corrupt essential processes in a metabolism-independent manner, such as membrane-targeting agents or compounds that activate uncontrolled protein degradation (e.g., ADEP4) [27].

- Synergistic Approaches: Combining metabolic modulators that force persister cells to resuscitate with conventional antibiotics to enhance killing [27].

In conclusion, metabolic transitions and diauxic shifts are not merely physiological events but are pivotal ecological triggers for the persister state within biofilms. Future research focusing on disrupting these specific metabolic signaling pathways holds great promise for developing more effective treatments against recalcitrant biofilm infections.

From Bench to Model: Techniques for Quantifying Nutrient-Linked Persistence

The study of biofilms in structured, colony-type systems is fundamental to understanding microbial physiology in environments that mirror natural and clinical settings. A core principle governing these communities is the formation of physical and chemical gradients, which arise from metabolic activity and diffusion limitations within the aggregated biomass [3]. These gradients are not merely a consequence of growth; they actively shape the physiological heterogeneity of the population, influencing everything from primary metabolism to the emergence of transiently tolerant sub-populations known as persisters [3] [29]. The interplay between gradient formation and physiology has far-reaching consequences for human health, particularly in the context of chronic infections and antibiotic treatment failure [3] [30]. This guide details the experimental systems that enable researchers to dissect these complex relationships, with a specific focus on methodologies that control nutrient delivery to probe the mechanisms of persister formation.

Key Experimental Methodologies for Colony Biofilms

A range of techniques has been developed to cultivate and analyze colony biofilms, allowing for precise control over the environment and detailed observation of community structure and function. The following table summarizes the primary systems in use.

Table 1: Overview of Key Colony Biofilm Experimental Systems

| Experimental System | Core Principle | Key Readouts & Applications | Notable Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane-Based Colony Biofilms [29] | Cells grown on a porous membrane atop solid agar, allowing nutrient diffusion from below. | Persister assays, gene expression analysis, metabolic studies. | Simplicity and reliability; ideal for studying nutrient transitions from a primary to a secondary carbon source [29]. |

| Microfluidic Devices [30] | Traps for growing microcolonies with continuous media flow from one side, creating controlled nutrient gradients. | Real-time imaging of growth and gene expression, response to dynamic antibiotic regimens. | Enables high-resolution, spatiotemporal analysis of gradient-driven phenomena in a biofilm-like environment [30]. |

| Pipe Loop Samplers [31] | Closed-loop flow-through systems with removable material coupons to simulate plumbing or industrial piping. | Biomass quantification, disinfectant efficacy testing, material biofilm growth potential. | Directly applicable to industrial and public health settings (e.g., drinking water distribution systems) [31]. |

| Macro-Colony Imaging (Mesoscopy) [32] | Use of specialized optics (e.g., Mesolens) to image large, intact colonies at high resolution. | Visualization of internal colony architecture, such as intra-colony channels for nutrient transport. | Reveals emergent structural features of mature colonies without destructive processing [32]. |

Detailed Protocol: Membrane-Based Colony Biofilm for Nutrient Transition Studies

This protocol, adapted from Amato & Brynildsen (2014), is specifically designed to investigate how nutrient shifts stimulate persister formation [29].

- Preparation of Inoculum:

- Grow the bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli MG1655) overnight for 16 hours in a defined minimal medium (e.g., M9) with a primary carbon source (e.g., 10 mM glucose).

- Biofilm Establishment:

- Dilute the overnight culture into fresh M9 medium containing a limiting concentration of the primary carbon source (e.g., 2.5-15 mM glucose) to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.01.

- Inoculate 100 µL aliquots onto sterile, polyethersulfone (PES) membranes (0.2 µm pore size, 25 mm diameter) positioned on M9 minimal agar plates.

- The agar should contain a high concentration (e.g., 60 mM) of the secondary carbon source to be studied (e.g., fumarate) or no carbon as a control.

- Growth and Monitoring:

- Incubate the plates at 37°C.

- Monitor growth by aseptically removing membranes at intervals, vortexing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 minute to dislodge cells, and measuring the OD₆₀₀ of the suspension.

- Inducing Nutrient Transition and Sampling Persisters:

- The primary carbon source (glucose) in the inoculum is exhausted after a predictable number of doublings, forcing a transition to the secondary source in the agar.

- Sample persisters at two critical time points: 1) prior to glucose exhaustion (e.g., FCOD₆₀₀ = 6), and 2) after glucose exhaustion and the transition is underway (e.g., FCOD₆₀₀ = 30) [29].

- For persister assays, dislodge cells from the membrane, treat with a high concentration of antibiotic (e.g., ofloxacin) for a set period, wash, and plate on solid media to count surviving colony-forming units (CFUs).

Detailed Protocol: Microfluidic Device for Spatial Gradient Analysis

This system allows for real-time observation of gradient formation and its consequences [30].

- Device Fabrication and Preparation:

- Fabricate a microfluidic device containing deep (e.g., 170 µm) traps for cell growth, connected to nutrient supply channels.

- Inoculation and Growth:

- Load a bacterial strain, potentially carrying fluorescent reporters for genes of interest (e.g., tetracycline resistance operon), into the device traps.

- Continuously perfuse the supply channels with fresh growth medium. Nutrients diffuse into the trap, creating a gradient from the open edge to the interior.

- Real-Time Imaging and Analysis:

- Use time-lapse microscopy to monitor colony development.

- Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) can be applied to time-lapse images to calculate cell movement and growth rates throughout the colony [30].

- Fluorescence signals reveal the spatial pattern of gene expression in response to the nutrient gradient or to subsequent challenges, such as the introduction of antibiotics via the supply channels.

Quantitative Assessment of Biofilms

The quantitative evaluation of biofilm mass, viability, and metabolic activity is crucial. Different methods offer distinct advantages and are suited to different research questions.

Table 2: Quantitative Methodologies for Biofilm Analysis

| Methodology | What It Measures | Typical Data Output | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| XTT Reduction Assay [33] | Metabolic activity of cells within the biofilm matrix via tetrazolium salt reduction. | Colorimetric readout (Absorbance at 490nm). | Accurate measure of cellular viability and vitality; more reproducible for Vibrionaceae than CV staining [33]. |

| Colony Forming Units (CFU) [33] [31] | Number of culturable/culturable bacteria. | CFU per unit area or volume. | Measures viability but is labor-intensive; does not account for viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells [31]. |

| Crystal Violet (CV) Staining [33] | Total adhered biomass (cells and matrix). | Colorimetric readout (Absorbance at 562nm). | Semi-quantitative; cannot differentiate between live and dead cells. |

| Flow Cytometry (FCM) [31] | Total bacterial cell count using fluorescent nucleic acid stains (e.g., Syto 9). | Cell count per unit area or volume. | Provides rapid, automated total cell counting; does not distinguish viability without specific stains. |

| Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy (CSLM) [31] | 3D architecture, biomass, and spatial distribution of live/dead cells. | Biomass volume, thickness, roughness. | Allows in situ analysis of biofilm structure; requires specialized equipment and expertise. |

| Dry Cell Mass [33] | Total dry weight of the biofilm. | Mass (e.g., µg). | Direct measurement but is low-throughput and requires large amounts of biofilm. |

Connecting Nutrient Gradients to Persister Formation: A Pathway Analysis

Nutrient transitions, particularly diauxic shifts, have been identified as a direct stimulus for persister formation in biofilms [29]. The pathway involves key regulators that sense and respond to metabolic stress.

Diagram 1: Nutrient stress to persister formation pathway.

The pathway outlined in the diagram can be broken down as follows:

- Stimulus: A carbon source transition, such as the exhaustion of a preferred sugar like glucose, acts as a nutrient stress signal [29].

- Central Mediator: This stress activates the RelA enzyme, leading to a rapid accumulation of the alarmone ppGpp [29]. This molecule is a central mediator of the stringent response and has been strongly implicated in bacterial persistence across multiple studies.

- Effectors: Elevated ppGpp levels lead to changes in the expression and activity of Nucleoid-Associated Proteins (NAPs), such as FIS and HU [29]. These proteins play a critical role in orchestrating large-scale changes in gene expression and chromosome organization.

- Phenotype: The action of these NAPs promotes the entry of a sub-population of cells into the persister state, a slow-growing or dormant phenotype characterized by multi-drug tolerance [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in this field relies on a suite of specific reagents, strains, and tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm and Persister Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PES Membranes | Support for colony biofilm growth; allows diffusion of nutrients from underlying agar. | 0.2 µm pore size, 25 mm diameter; sterile [29]. |

| Defined Minimal Media (M9) | Provides controlled environment for studying specific nutrient effects. | Can be supplemented with defined carbon sources (e.g., glucose, fumarate) at varying concentrations [29]. |