Probing the Nanoscale: Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy with AFM to Decipher Biofilm Adhesins

This article explores the transformative role of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)-based single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) in quantifying the nanoscale forces governing biofilm adhesion.

Probing the Nanoscale: Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy with AFM to Decipher Biofilm Adhesins

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)-based single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) in quantifying the nanoscale forces governing biofilm adhesion. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we detail how SMFS and single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) unravel the strength, specificity, and dynamics of microbial adhesins. The content covers foundational principles, advanced methodologies like FluidFM, and troubleshooting for quantitative force measurement. It further validates AFM's application in profiling genetic mutants, evaluating anti-fouling coatings, and comparing its capabilities against other biophysical techniques, providing a comprehensive resource for developing novel anti-adhesion strategies.

The Nanomechanical World of Biofilms: How Force Governs Microbial Adhesion

Basic Principles of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a powerful scanning probe technique that generates high-resolution, three-dimensional topography maps of sample surfaces. Invented in 1986 by Binnig, Quate, and Gerber, AFM operates by measuring the interaction forces between a sharp probe and the sample surface [1] [2]. A key advantage of AFM over other microscopy techniques is its ability to image samples under physiological conditions (in air or liquid) without requiring destructive preparation methods such as drying, metal coating, or freezing [3] [2].

The core components of a conventional AFM system include [1] [3]:

- Probe: A microfabricated sharp tip (typically silicon or silicon nitride with a 1-50 nm apical radius) attached to the end of a flexible cantilever.

- Piezoelectric Scanner: Moves the sample or probe with high precision in three dimensions (X, Y, and Z).

- Optical Lever Detection System: A laser beam focused on the back of the cantilever reflects into a position-sensitive photodiode to detect cantilever deflection.

- Feedback Controller: Maintains constant imaging parameters by adjusting scanner position based on detected deflection.

AFM operates in two primary modes. In static mode (contact mode), the tip remains in continuous contact with the sample surface, measuring repulsive forces through cantilever deflection [1]. In dynamic mode (tapping or intermittent contact mode), the cantilever oscillates near its resonant frequency, and changes in oscillation amplitude, frequency, or phase due to tip-sample interactions are monitored, reducing lateral forces and sample damage [3] [2]. AFM can detect forces as small as 7-10 pN and achieve lateral resolution of 0.5-1 nm and axial resolution of 0.1-0.2 nm [3].

Fundamentals of Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS)

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS) is a specialized AFM modality that investigates the mechanical properties, unfolding pathways, and interaction forces of individual molecules [4] [5]. In SMFS, the AFM tip is functionalized with specific molecules, brought into contact with a surface-bound partner, and then retracted while measuring the force required to rupture the bond or extend the molecule [4] [6].

The fundamental measurement in SMFS is the force-distance curve, which records cantilever deflection versus vertical piezo displacement [6]. As the tip retracts, characteristic peaks in the force curve reveal discrete molecular events such as bond rupture or domain unfolding. The cantilever behaves as a spring obeying Hooke's law (F = k·Δx), where force (F) is calculated from the predetermined spring constant (k) of the cantilever and its measured deflection (Δx) [1] [3].

SMFS enables reconstruction of energy landscapes and understanding of molecular biomechanics by tilting the underlying energy landscape through applied force [5]. This accelerates conformational changes and allows observation of transient states that are biologically relevant but difficult to capture otherwise. SMFS has illuminated mechanisms in diverse biological systems including muscle proteins, hearing mechanisms, blood coagulation, cell adhesion, and extracellular matrix components [5].

Quantitative Parameters in AFM-SMFS

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters Measurable by AFM-SMFS

| Parameter | Description | Typical Range/Values | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rupture Force | Force required to break an intermolecular bond or unfold a protein domain | Varies from pN to nN scale [7] | Reveals binding strength and mechanical stability of molecular complexes [4] |

| Young's Modulus | Measure of material stiffness or resistance to elastic deformation | GigaPascals for amyloid fibrils [1] | Indicates mechanical properties of cells and tissues; changes in pathology [3] |

| Adhesion Forces | Attractive forces between tip and sample during retraction | pN to μN range [8] | Quantifies cell-cell and cell-surface interactions in biofilm formation [7] |

| Unfolding Length | Protein elongation upon mechanical unfolding | ~24 nm for C3 domain of cardiac myosin-binding protein [9] | Provides insights into protein folding pathways and domain organization [5] |

| Loading Rate | Rate of force application during bond rupture | 40 pN/s used in protein unfolding studies [9] | Affects measured rupture forces; reveals energy landscape parameters [4] |

Table 2: AFM-SMFS Operational Characteristics and Limitations

| Characteristic | Specifications | Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|

| Force Sensitivity | As low as 7-10 pN [3] | Enables detection of individual molecular interactions |

| Spatial Resolution | Lateral: 0.5-1 nm; Axial: 0.1-0.2 nm [3] | Permits visualization of single molecules and atomic-scale features |

| Calibration Uncertainty | Typically up to 25% for spring constant [9] | Limits absolute force accuracy; concurrent methods improve relative measurements [9] |

| Imaging Environment | Air, liquid, or vacuum [3] [2] | Enables study of biological samples in physiological conditions |

| Scanning Speed | Traditional AFM: slow; High-speed AFM: video rates [3] | HS-AFM allows real-time observation of biomolecular processes |

Experimental Protocols for SMFS on Biofilm Adhesins

Sample Preparation and Immobilization

Proper sample immobilization is critical for successful SMFS experiments. For bacterial cells and adhesins, the following protocol is recommended:

Substrate Selection: Use freshly cleaved mica or glass substrates for their atomically flat surfaces [8]. Functionalize with 0.1% poly-L-lysine (PLL) or 0.01% polyethyleneimine (PEI) to enhance cell adhesion [8].

Cell Immobilization:

- Grow bacterial cultures to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5-0.8)

- Centrifuge at 5,000 × g for 5 minutes and resuspend in appropriate buffer

- Apply 50-100 μL bacterial suspension to functionalized substrate

- Incubate for 30-60 minutes at room temperature to allow attachment

- Gently rinse with buffer to remove non-adherent cells [7] [8]

Alternative Entrapment Method: For weakly adhering cells, use mechanical entrapment in porous polycarbonate filters with 0.4-3 μm pore size or soft 0.5-2% agarose gels [8].

Cantilever Functionalization

Specific interaction measurements require functionalization of AFM tips with molecules of interest:

Tip Cleaning: Expose cantilevers to UV-ozone for 30 minutes or oxygen plasma for 5-10 minutes [5].

Surface Activation: Incubate tips with 1-10 mM reactive linkers such as NHS-PEG-biotin or NHS-PEG-maleimide for 1 hour at room temperature [5].

Ligand Attachment:

Quality Control: Verify functionalization by testing specific binding against control surfaces before main experiments [4].

Force Spectroscopy Measurements

Instrument Setup:

Data Collection:

- Acquire force curves (1,000-10,000 per sample) at multiple locations

- Vary loading rates (100-100,000 pN/s) to probe energy landscape [4]

- Include control measurements with blocked tips or irrelevant ligands

Specificity Controls:

- Perform competition experiments with free ligands

- Use adhesin-deficient mutant strains as negative controls

- Test tip functionalization with blocking antibodies [7]

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Force Curve Analysis

Processing Steps:

- Convert deflection and position data to force-distance curves [6]

- Correct baseline and offset

- Identify specific adhesion events and rupture forces

Single-Molecule Validation:

Bond Parameter Extraction:

Statistical Analysis

Distribution Analysis:

- Plot histograms of rupture forces and unfolding lengths

- Fit with Gaussian or other appropriate distributions

- Compare populations using statistical tests (t-test, ANOVA)

Energy Landscape Reconstruction:

- Combine data from multiple loading rates

- Apply Jarzynski equality or Crooks fluctuation theorem for equilibrium information from non-equilibrium measurements [5]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AFM-SMFS Biofilm Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Substrates | Freshly cleaved mica, Glass coverslips, HOPG [1] [8] | Provide atomically flat surfaces for sample immobilization |

| Immobilization Agents | Poly-L-lysine (PLL), Polyethyleneimine (PEI), Polydopamine [8] | Enhance adhesion of bacterial cells to substrates |

| Cantilever Types | Silicon nitride tips, Sharpened pyramidal tips, Colloidal probes [1] [8] | Physical probe for surface interaction and force measurement |

| Functionalization Chemistry | NHS-PEG linkers, Maleimide-PEG, Biotin-avidin systems [5] | Covalently attach specific ligands to AFM tips |

| Biological Ligands | Recombinant adhesins, Specific antibodies, Lectins [7] [5] | Enable specific interaction measurements with target molecules |

| Buffer Systems | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Tris-HCl, HEPES [3] | Maintain physiological conditions during liquid imaging |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

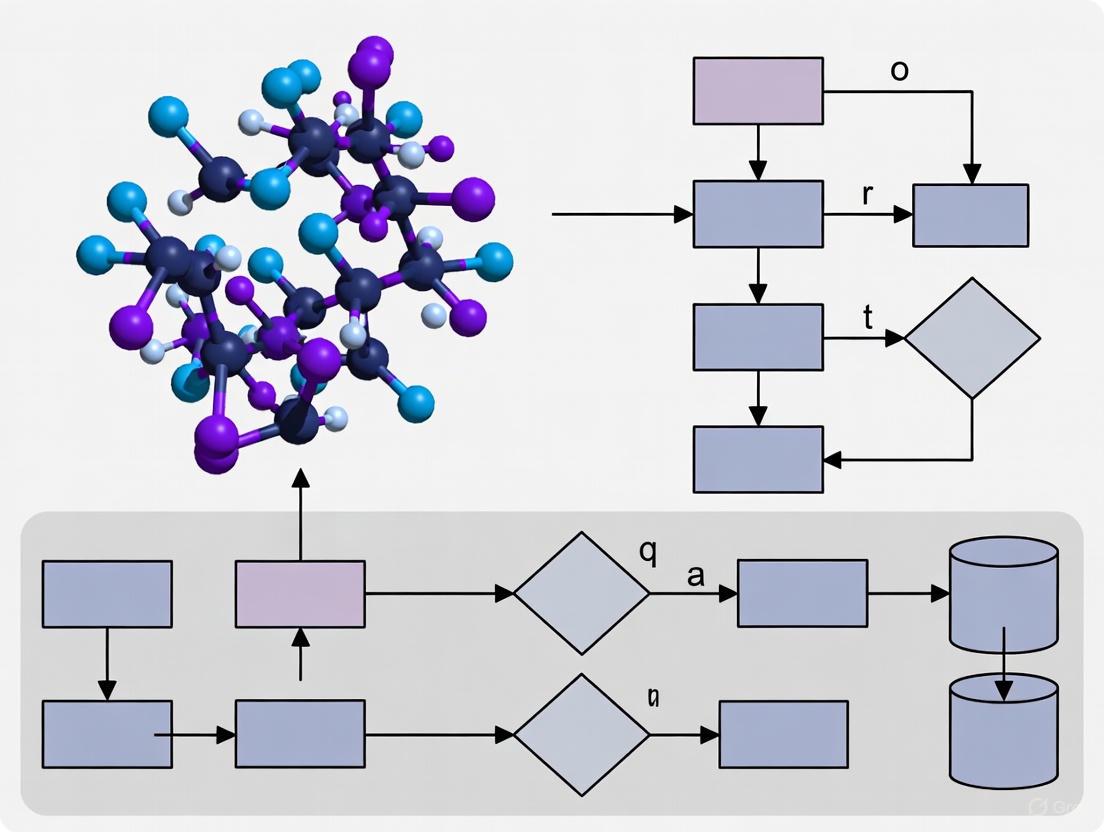

AFM-SMFS Experimental Workflow

Adhesin Mechanoresponse Pathway

The Critical Role of Adhesins in Biofilm Initiation and Pathogenesis

Biofilms are structured microbial communities anchored to biotic or abiotic surfaces and encased in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. The initial and most critical step in biofilm formation is bacterial surface adhesion, a process primarily mediated by a class of specialized bacterial surface proteins and appendages known as adhesins [10]. These molecular structures enable planktonic bacteria to transition from a free-floating state to a surface-associated lifestyle, initiating a cascade of events that leads to biofilm maturation and, in pathogenic contexts, disease pathogenesis.

The transition from reversible to irreversible attachment represents a committed step in biofilm development, setting the stage for microcolony formation, EPS production, and eventual maturation of complex, three-dimensional biofilm structures [11]. Within the context of infectious diseases, biofilms pose a significant clinical challenge as their structural integrity and physiological state confer enhanced tolerance to antimicrobial agents and evasion of host immune defenses [10]. Understanding the precise mechanisms by which adhesins function at the molecular and nanoscale levels is therefore paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies to disrupt biofilm-associated infections.

Molecular Diversity and Functions of Key Adhesins

Bacteria employ a diverse arsenal of adhesins to facilitate surface attachment, with different species expressing distinct yet functionally analogous structures. The table below summarizes major adhesin types and their roles in biofilm initiation for key bacterial pathogens.

Table 1: Major Bacterial Adhesins and Their Roles in Biofilm Initiation

| Bacterial Species | Adhesin Type | Molecular Function | Role in Biofilm Initiation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli [12] | Type 1 Fimbriae (T1F) | Mannose-sensitive adhesion | Initial docking to surfaces, cell-cell aggregation |

| Curli Fimbriae | Surface protein binding, cell aggregation | Microcolony formation, strengthens biofilm architecture | |

| Antigen 43 (Ag43) | Autotransporter protein, cell-to-cell adhesion | Autoaggregation, promotes microcolony formation | |

| Staphylococcus spp. [13] | Polysaccharide Intercellular Adhesin (PIA) / Poly-β(1,6)-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) | Exopolysaccharide production | Critical for cell-cell adhesion and biofilm matrix integrity |

| General Gram-positive [14] | MSCRAMMs (Microbial Surface Components Recognizing Adhesive Matrix Molecules) | Host extracellular matrix protein binding | Mediates attachment to host tissues and implanted devices |

The functional expression of these adhesins is highly regulated and influenced by environmental conditions. For instance, in E. coli, the expression of curli fimbriae and cellulose is positively correlated with robust biofilm formation, while type 1 fimbriae and autotransporter proteins like Ag43 further contribute to the persistence of these organisms in the environment [12]. The exopolysaccharide PIA/PNAG, produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis and E. coli, is biochemically indistinguishable between the species and plays a conserved role in providing structural integrity to the biofilm matrix and protecting against host immune responses [13].

Quantitative Analysis of Adhesin-Mediated Forces

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) based single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) has revolutionized the quantitative study of adhesin function by allowing researchers to measure the piconewton-scale forces involved in bacterial adhesion at the single-cell and single-molecule level [15]. This technique functionalizes the AFM tip with a specific molecule (e.g., an antibody, ligand, or even a single bacterial cell) and measures the interaction forces with a surface or receptor.

Table 2: AFM-Based Force Spectroscopy Measurements of Bacterial Adhesion

| Bacterial System / Material | Measured Parameter | Reported Value | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. mutans on various biomaterials [16] | Maximum Adhesion Force | Varied by surface | Early attachment to 12 different biomaterial types |

| E. coli on 58S Bioactive Glass [14] | Adhesion Force | ~6 nN | Initial (1 sec) contact; attributed to more adhesive nanodomains |

| S. aureus on 58S Bioactive Glass [14] | Adhesion Force | ~3 nN | Initial (1 sec) contact |

| Gram-positive Adhesin-Ligand [14] | Binding Strength | ~0.05 to ~2 nN | Single-molecule interaction range |

| Oral Bacteria-Biomaterial [16] | Adhesion Energy | Quantified | Work of adhesion during AFM retraction |

| Oral Bacteria-Biomaterial [16] | Rupture Length | Quantified | Length scale of bond disruption events |

AFM studies have revealed that adhesion is not a static event but a dynamic process. The bond strength between a bacterium and a surface increases with contact time according to the function F(t) = F0 + (F∞ - F0) exp(-t/τk), where F(t) is the adhesion force at time t, F0 is the initial adhesion force, F∞ is the force after bond strengthening, and τk is a characteristic time constant [14]. This transition from reversible to irreversible adhesion is characterized in force-distance curves by an increase in the number of minor rupture peaks, indicating the formation of multiple specific molecular bonds [14].

Experimental Protocol: AFM Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy for Quantifying Bacterial Adhesion

Principle: This protocol measures the adhesion forces between a single bacterial cell and a substrate of interest by immobilizing a living bacterial cell onto an AFM cantilever and performing force-distance curves against the target surface [15] [14].

Materials:

- Atomic Force Microscope

- Tipless, gold-coated cantilevers (e.g., NP-O, Bruker)

- Bacterial culture in mid-log phase

- Target substrate (e.g., biomaterial, coated surface)

- Polyethyleneimine (PEI) or similar cell-friendly glue

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or appropriate physiological buffer

Procedure:

- Cantilever Functionalization: Clean tipless cantilevers using UV-ozone treatment for 15-20 minutes.

- Cell Probe Preparation: Apply a minute amount of PEI glue to the end of the cantilever using a microinjection system under a microscope. Carefully approach a single bacterial cell from the cultured population with the glued cantilever, making brief contact to attach the cell. Retract the cantilever and allow the glue to cure fully.

- AFM Mounting and Calibration: Mount the cell-functionalized cantilever into the AFM holder. Submerge both the probe and the target substrate in a liquid cell filled with buffer. Calibrate the cantilever's spring constant using the thermal tuning method.

- Force-Distance Curve Acquisition: Position the cell probe above the substrate. Program the AFM to collect multiple force-distance curves (e.g., 256-1024) over a grid on the substrate surface. Typical parameters include: approach/retract speed of 0.5-1 µm/s, applied force trigger of 0.5-2 nN, and contact times ranging from 0.1 to 1 second to study bond maturation.

- Data Analysis: Use dedicated software to analyze the retraction portion of the force curves. Key parameters to extract include:

- Adhesion Force: The maximum force recorded during retraction (minimum of the curve).

- Adhesion Energy (Work of Detachment): The area under the retraction curve.

- Rupture Events: The number and length of unbinding events observed as peaks in the retraction curve.

Signaling Pathways Regulating Adhesin Expression and Biofilm Development

The decision to transition from a planktonic to a biofilm lifestyle is governed by sophisticated, integrated surface sensing networks and cell-cell communication systems. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathway in P. aeruginosa that links surface sensing to biofilm inhibition via adhesin regulation.

Figure 1: QS-Mediated Autolubrication Pathway. This pathway, identified through microtopographical screening, shows how specific surface topographies can activate a quorum sensing system that leads to the production of anti-adhesive biosurfactants, thereby preventing biofilm formation [11].

This pathway highlights a counter-intuitive mechanism where specific surface topographies activate the Rhl QS system, leading to the production of rhamnolipids that act as an "autolubricant," preventing irreversible bacterial attachment [11]. This finding was confirmed through genetic studies where deletion of rhlI, rhlR, or rhlA genes restored biofilm formation on anti-attachment topographies, and genetic complementation or exogenous addition of the signaling molecule C4-HSL reinstated the biofilm-resistant phenotype [11].

Therapeutic Targeting of Adhesins

The critical role of adhesins in the initial stages of biofilm formation makes them attractive targets for novel anti-biofilm strategies. One promising approach is the use of antibodies to target and disrupt key structural components of the biofilm matrix.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Anti-Adhesin Antibody Efficacy in Biofilm Inhibition

Principle: This protocol evaluates the ability of antibodies raised against specific adhesin molecules (e.g., PIA/PNAG) to inhibit biofilm formation and promote opsonophagocytic killing of bacteria [13].

Materials:

- Target bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli ATCC 25922, S. epidermidis)

- Purified adhesin antigen (e.g., PIA/PNAG)

- Experimental animals (e.g., mouse model) for antibody generation

- Polystyrene microtiter plates

- Crystal violet stain (1%)

- Acetic acid (30%)

- Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) or other suitable growth media

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Fresh human blood or isolated neutrophils for opsonophagocytosis assay

Procedure: Part A: Antibody Generation and Purification

- Antigen Preparation: Extract and purify the target adhesin polysaccharide (e.g., PIA from S. epidermidis) using established mechanical and chemical methods, confirming its structure via FTIR or NMR [13].

- Immunization: Immunize mice with the purified antigen according to a standard schedule (e.g., primary immunization followed by boosts). Collect serum from immunized and control (non-immunized) groups.

Part B: In Vitro Biofilm Inhibition Assay

- Biofilm Growth: Adjust the optical density (OD600) of a bacterial culture to 0.7. Dilute the culture 1:200 in a biofilm-promoting medium (e.g., BHI broth with 1% glucose). Add 200 µL of this suspension to the wells of a polystyrene microtiter plate. Include test wells containing a pre-determined dilution of the immune serum (e.g., 10% v/v) [13].

- Incubation and Staining: Incubate the plate statically for 24 hours at 37°C. Carefully remove planktonic cells and wash each well three times with PBS. Fix the adherent cells and stain with 150 µL of 1% crystal violet for 15-20 minutes.

- Quantification: Wash off excess stain, solubilize the crystal violet bound to the biofilm in 160 µL of 30% acetic acid, and measure the absorbance of the solution spectrophotometrically at 595 nm. Compare the absorbance values between immune serum-treated and control groups.

Part C: Opsonophagocytosis Assay

- Opsonization: Mix bacteria with the immune serum and a complement source. Incubate to allow antibody binding (opsonization).

- Phagocytosis: Add fresh human neutrophils or whole blood to the opsonized bacteria and incubate under rotation to facilitate phagocytosis.

- Viability Assessment: Plate serial dilutions of the mixture onto agar plates after incubation to determine bacterial viability. Calculate the percentage of bacterial killing in the immune serum group compared to controls, where a lethality of ~40% has been reported for anti-PIA antibodies against E. coli [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials essential for conducting research on adhesins and biofilm pathogenesis using the techniques described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Adhesin and Biofilm Research

| Reagent / Material | Specifications / Example | Primary Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Cantilevers | Tipless, gold-coated (e.g., NP-O, Bruker); V-shaped for force spectroscopy | Bacterial cell probe preparation for Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS) [14] |

| Cell Adhesive | Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | Immobilizing live bacterial cells onto AFM cantilevers for SCFS [14] |

| Biofilm Growth Media | Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) + 1% D-Glucose (BHIGlc) | Enhancing polysaccharide production for robust in vitro biofilm formation in microtiter assays [13] |

| Biofilm Staining Reagent | Crystal Violet (1% aqueous solution) | Semi-quantitative staining of adherent bacterial biomass in microtiter plate assays [13] |

| Purified Adhesin Antigens | e.g., PIA/PNAG polysaccharide from S. epidermidis | Immunization for functional antibody production and surface coating for binding studies [13] |

| Anti-Adhesin Antibodies | Polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies (e.g., anti-PIA/PNAG) | Functional blockade of adhesion, biofilm disruption, and opsonophagocytosis assays [13] |

| Ophiopogonin D' | Ophiopogonin D|High-Purity Reference Standard | |

| Fenbendazole-d3 | Fenbendazole-d3, CAS:1228182-47-5, MF:C15H13N3O2S, MW:302.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool for quantifying the key mechanical properties of bacterial biofilms and their constituent adhesins at the single-molecule level. By functionalizing AFM probes with specific molecules or even single bacterial cells, researchers can directly measure adhesion forces, binding kinetics, and surface stiffness that govern biofilm initiation, structure, and resilience [17]. These measurements provide critical insights into the fundamental mechanisms underlying microbial attachment to abiotic surfaces and host tissues—the crucial first step in biofilm-associated infections and biofouling [17] [18]. The ability to probe these properties under physiological conditions makes AFM particularly valuable for research aimed at developing novel anti-biofilm strategies, as it preserves the native state of biological interactions [19].

This protocol details the application of AFM force spectroscopy techniques to characterize the mechanical properties of biofilm adhesins, providing standardized methodologies for data acquisition and analysis. The approaches described enable the absolute quantitation of parameters essential for understanding biofilm mechanics and developing targeted therapeutic interventions.

Quantified Mechanical Properties of Biofilms and Adhesins

The mechanical properties of biofilms and their molecular components vary significantly across bacterial species, growth conditions, and environmental factors. The tables below summarize key quantitative measurements obtained through AFM force spectroscopy.

Table 1: Single-Cell and Single-Molecule Adhesion Forces

| Measurement Type | Specimen | Adhesion Force | Experimental Conditions | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Adhesion | E. coli to goethite | -3.0 ± 0.4 nN | In water, after 4s contact | [20] |

| Single-Cell Adhesion | Chromatium okenii to soft surfaces | 0.21 ± 0.10 nN to 2.42 ± 1.16 nN | Substrate stiffness: 20-120 kPa | [21] |

| Single-Molecule Binding | Gram-negative type I, IV pili | ~250 pN | Characteristic constant force plateaus | [17] |

| Single-Molecule Binding | Gram-positive pilus subunits | >500 pN | Covalent subunit bonds | [17] |

| Single-Molecule Binding | Staphylococcal adhesins (Cna, SpsL, SdrG) | ~1-2 nN | "Dock, lock, and latch" mechanism | [17] |

Table 2: Biofilm Viscoelastic and Material Properties

| Property | Biofilm System | Value | Measurement Technique | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesive Pressure | P. aeruginosa PAO1 (early biofilm) | 34 ± 15 Pa | Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) | [19] |

| Adhesive Pressure | P. aeruginosa PAO1 (mature biofilm) | 19 ± 7 Pa | Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) | [19] |

| Adhesive Pressure | P. aeruginosa wapR mutant (early biofilm) | 332 ± 47 Pa | Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) | [19] |

| Young's Modulus | S. epidermidis (Native EPS) | Baseline Value | AFM nanoindentation | [22] |

| Young's Modulus | S. epidermidis (EPS-modified) | Significant change (p<0.05) | AFM after EPS modifier treatment | [22] |

Experimental Protocols for AFM Force Spectroscopy

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS)

Objective: To quantify the specific binding forces and kinetics of individual adhesin-ligand interactions.

Procedure:

- Probe Functionalization: A sharp AFM tip (e.g., Si₃N₄) is chemically functionalized with a purified target ligand (e.g., host extracellular matrix protein such as fibrinogen or collagen). This is typically achieved via PEG-linkers to allow for flexible, specific binding [17].

- Sample Preparation: Bacterial cells (or purified adhesins immobilized on a solid substrate) are deposited on a freshly cleaved mica or glass surface and gently rinsed with an appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS) to remove unattached cells [17] [20].

- Force-Distance Curve Acquisition: The functionalized tip is brought into contact with the bacterial surface at a defined contact force (typically 100-500 pN) and contact time (0.1-1 s) before retraction. This cycle is repeated hundreds to thousands of times at different locations on the cell surface.

- Data Analysis: Force-distance curves are analyzed for specific unbinding events. A force histogram is constructed from the rupture events, with the most probable unbinding force corresponding to the single-molecule adhesion strength. Binding kinetics (on- and off-rates) can be extracted from dynamic force spectroscopy measurements performed at different retraction speeds [17].

Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS)

Objective: To measure the total adhesion force between a single living bacterial cell and a substrate.

Procedure:

- Cell Probe Preparation: A tipless AFM cantilever is functionalized with a bio-compatible adhesive (e.g., polydopamine or a thin layer of UV-curable glue). A single bacterial cell, harvested from the mid-exponential growth phase and washed, is then attached to the cantilever [17] [21].

- Substrate Preparation: The target substrate (e.g., coated glass, biomaterial surface, or host tissue mimic) is mounted in the AFM liquid cell and immersed in buffer.

- Adhesion Mapping: The cell-probe is approached to the substrate with a set contact force and time to simulate initial attachment. Upon retraction, the force-distance curve is recorded, and the maximum adhesion force (the minimum force in the retraction curve) is measured.

- Quantitative Analysis: The adhesion force is calculated by multiplying the cantilever deflection by its spring constant. Statistics are gathered from multiple measurements on different cells and locations [21] [20]. This method can also be adapted to study cell-cell adhesion [17].

Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) for Intact Biofilms

Objective: To simultaneously quantify the adhesive and viscoelastic properties of an intact biofilm over a defined, reproducible contact area [19].

Procedure:

- Probe Preparation: A glass microbead (e.g., 50 µm diameter) is attached to a tipless AFM cantilever to create a spherical probe with a known geometry.

- Biofilm Coating: The microbead probe is coated with a layer of biofilm by bringing it into gentle contact with a mature biofilm and then retracting it, transferring a consistent amount of biofilm material to the bead.

- Standardized Force Measurement: The biofilm-coated bead is approached onto a clean glass substrate in liquid with a defined loading force, contact time, and retraction speed. The force-distance curve during retraction provides the adhesive pressure (adhesion force divided by contact area).

- Viscoelasticity Measurement: During the force cycle, a constant load is held for a defined period (creep test). The resulting indentation vs. time data is fitted to a viscoelastic model (e.g., Voigt Standard Linear Solid model) to extract elastic moduli and viscosity [19].

Nanoindentation for Stiffness Mapping

Objective: To map the local mechanical stiffness (Young's modulus) of a biofilm surface at the micro- to nanoscale.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Biofilms are grown directly on a solid substrate (e.g., glass coverslip) suitable for AFM imaging. They are measured in their native hydrated state in an appropriate fluid [22].

- Force Volume Imaging: The AFM tip performs an array of force-distance curves over the biofilm surface. At each point, the approach curve is analyzed using a contact mechanics model (e.g., Hertz, Sneddon, or JKR model) to calculate the local Young's modulus from the indentation depth versus applied force.

- Data Processing: A spatial stiffness map is generated, correlating topography with mechanical properties. This allows researchers to identify heterogeneity in the biofilm matrix, such as stiff cell bodies versus softer extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) regions [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for AFM Biofilm Mechanics

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Tipless Cantilevers | Base for creating cell- or bead-probes for SCFS and MBFS. | Material: Silicon; Spring Constant: 0.01-0.08 N/m; Resonance Frequency: ~10 kHz [19]. |

| Functionalized Sharp Tips | For high-resolution SMFS and topography imaging. | Material: Si₃N₄; Tip Radius: <20 nm; PEG-linked ligands for specific binding [17]. |

| Glass Microbeads | Provides defined geometry for quantifiable contact area in MBFS. | Diameter: 50 µm; Attached to tipless cantilevers with epoxy [19]. |

| EPS Modifier Agents | To dissect the role of specific EPS components in biofilm mechanics. | Proteinase K (degrades proteins), DNase I (degrades eDNA), Periodic Acid (oxidizes polysaccharides), Ca²âº/Mg²⺠(cross-links EPS) [22]. |

| Bio-Immobilization Substrates | Provides a flat, clean surface for immobilizing cells or biofilms. | Freshly cleaved Mica, Plasma-cleaned Glass, or PFOTS-treated glass for hydrophobic surfaces [23] [20]. |

| Maxadilan | Maxadilan, CAS:135374-80-0, MF:C291H465N85O95S6, MW:6867 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Eupaglehnin C | Eupaglehnin C|476630-49-6|Sesquiterpenoid Inhibitor | High-purity Eupaglehnin C (CAS 476630-49-6), a sesquiterpenoid for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or personal use. |

Workflow and Data Analysis Diagrams

Concluding Remarks

The AFM force spectroscopy protocols detailed herein provide a robust framework for quantitatively characterizing the mechanical properties of biofilm adhesins. The integration of SMFS, SCFS, MBFS, and nanoindentation offers a comprehensive toolkit for dissecting the molecular and cellular-scale forces that underpin biofilm adhesion, cohesion, and resistance. The quantitative data generated through these standardized methods are invaluable for validating theoretical models, screening anti-biofilm agents that target mechanical integrity, and informing the design of anti-fouling surfaces. As the field advances, the integration of machine learning for automated data analysis and large-area scanning will further enhance the throughput and predictive power of these techniques, solidifying AFM's role as an indispensable tool in biofilm research and therapeutic development [23] [24].

Bacterial Pili and Fimbriae as Force-Bearing Nanosprings

In the realm of bacterial pathogenesis, adhesion is a critical first step. Bacterial pili and fimbriae are hair-like appendages that function not merely as static tethers but as dynamic, force-bearing nanosprings. These structures are engineered to undergo significant, often superelastic, conformational changes in response to mechanical stress, enabling sustained bacterial attachment under fluid shear forces. Within the context of single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) research on biofilm adhesins, understanding the biomechanical properties of these nanosprings is paramount. This Application Note details the quantitative biophysics of these structures and provides standardized protocols for their investigation, providing researchers with the tools to probe the molecular mechanisms of bacterial adhesion.

Structural Mechanisms of Force Reception and Dissipation

The nanospring functionality of pili is not a generic property but is precisely engineered through distinct structural solutions that govern their response to mechanical force. High-resolution structural studies, particularly cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), have elucidated three primary mechanical stabilization strategies within pilus assemblies [25].

- Layer-to-Layer (LL) Interactions: These relatively weak, non-covalent interactions occur between pilin subunits on adjacent turns of the helical filament. They are the first to break under low external forces, facilitating the initial unwinding of the pilus helix and providing the first stage of extension [26] [25].

- N-terminal Staple: Found in pili like CS20 and P pili, this structural motif involves the first several N-terminal amino acids of a pilin subunit reaching to form stabilizing contacts with subunits several positions away in the filament (e.g., the n+4 subunit). This "stapling" significantly reinforces the quaternary structure and increases the force required for unwinding [25].

- Extended Loop Interactions: Loops projecting from the core β-sheet of one subunit interact with adjacent subunits (e.g., n+1, n+2). The length and composition of these loops vary between pilus types, directly influencing the stability and biophysical properties of the filament [25].

The combination of these solutions allows pili to be "optimized to withstand harsh motion without breaking," which is essential for pathogens to maintain attachment in turbulent environments like the urinary tract or intestine [26] [25]. The Table 1 below summarizes the key structural and functional differences among major pilus types from enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC).

Table 1: Comparative Biophysical and Structural Properties of Bacterial Pili

| Pilus Type (Pathovar) | Pilin Subunit | Pilus Class | Average Unwinding Force (pN) | Key Structural Stabilization Features | Major Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA/I (ETEC) | CfaB | 5 | ~7.5 [26] | Layer-to-layer interactions, N-terminal extension to n+4 subunit [25] | Sustained adhesion in the gastrointestinal tract [25] |

| CS17 (ETEC) | CsbA | 5 | Data pending (Structurally similar to CFA/I) [25] | Similar to CFA/I; specific force data limited [25] | Sustained adhesion in the gastrointestinal tract [25] |

| CS20 (ETEC) | CsnA | 1 | Data pending | Extended loops, N-terminal "staple" [25] | Sustained adhesion in the gastrointestinal tract [25] |

| Type 1 (UPEC) | FimA | 1 | Displays catch-bond behavior [27] | Hooked conformation of FimH adhesin at tip [27] | Shear-enhanced binding to bladder epithelium via FimH-mannose catch bond [27] |

| P Pilus (UPEC) | PapA | 1 | ~25-30 [25] | N-terminal "staple" motif [25] | Adhesion to kidney epithelium [25] |

The interplay of these structural features results in a common biomechanical response: the ability to unwind and rewind. When a tensile force is applied, the helical pilus filament reversibly unwinds, increasing its length by up to six-fold without breaking the backbone of the polymer. This unwinding, governed by the sequential breaking of the weaker layer-to-layer and loop interactions, serves as a critical shock-absorbing mechanism, modulating the force experienced by the adhesin at the tip and facilitating persistent attachment [25].

Diagram 1: The mechanical cycle of a pilus under force, from unwinding to rewinding.

Quantitative Biomechanics of Pilus Unwinding

The response of pili to mechanical force can be quantified to understand their role in adhesion. SMFS and optical tweezers have been instrumental in revealing that the unwinding force is a direct function of the cumulative strength of subunit-subunit interactions, rather than genetic sequence similarity [25]. Different pilus types are optimized for their specific environmental niches, with unwinding forces varying significantly.

For example, CFA/I pili from ETEC require a remarkably low force of approximately 7.5 pN to unwind, which is attributed to weak layer-to-layer interactions between subunits on adjacent turns of the helix [26]. In contrast, P pili from UPEC, which are stabilized by an N-terminal staple, require a much higher unwinding force, typically in the range of 25-30 pN [25]. This higher force reflects the need for stronger attachment in the dynamic environment of the urinary tract.

A key feature of the adhesive tips of many pili, such as the FimH protein of type 1 pili, is the catch bond mechanism. Unlike typical bonds that weaken under force, catch bonds become stronger. In FimH, tensile force causes a separation between its lectin domain (Ld) and pilin domain (Pd), triggering an allosteric shift in the Ld from a low-affinity to a high-affinity state for mannose. This results in a force-dependent decrease in the dissociation rate (off-rate) between approximately 30 and 80 pN, mechanically reinforcing adhesion under shear stress [27]. The Table 2 below summarizes key quantitative parameters for different pili.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Biomechanical Parameters of Pili

| Pilus Type | Typical Unwinding Force (pN) | Extension Ratio (Unwound/Original) | Key Biomechanical Feature | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA/I | ~7.5 [26] | Up to 6-fold [25] | Easy to unwind, hard to linearize; superelasticity [26] | Force-Measuring Optical Tweezers (FMOT) [26] |

| P Pilus | ~25-30 [25] | Up to 6-fold [25] | High unwinding force due to N-terminal staple [25] | Optical Tweezers, Steered MD [25] |

| Type 1 FimH | N/A (Adhesin) | N/A (Adhesin) | Catch bond with decreased off-rate at 30-80 pN [27] | Single Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS) [27] |

| General Fimbria | Varies by type | Can stretch to several times original length [28] | "Catch-bond" mechanism at adhesin tip [28] | AFM, Optical Tweezers [28] |

Experimental Protocols for SMFS of Pili and Biofilm Adhesins

Probing the nanomechanical properties of pili requires precise methodologies. The following protocols outline standardized procedures for using AFM-based SMFS and functionalized bead assays to quantify adhesion forces and dynamics.

Protocol: Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy of Pilus-Mediated Adhesion

Objective: To measure the specific unbinding forces and kinetics of pilus-adhesin interactions with host receptors at the single-molecule level.

Materials:

- Atomic Force Microscope (e.g., Bruker MultiMode or JPK NanoWizard)

- AFM cantilevers (e.g., MLCT-BIO from Bruker, nominal spring constant 0.01-0.1 N/m)

- Bacterial strain expressing the pilus of interest

- Target substrate (e.g., mannosylated BSA for Type 1 pili, specific glycans for other pili)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

Method:

- Functionalization:

- Chemically immobilize intact bacteria or purified pili/fimbrial tips onto a freshly cleaned, APTES-coated glass slide or directly onto the AFM substrate. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature or 30 minutes at 37°C in a humid chamber [27].

- Alternatively, for specific receptor studies, functionalize the AFM cantilever tip with the relevant ligand (e.g., mannosylated BSA) using standard cross-linker chemistry (e.g., PEG-linker) [7].

Force Spectroscopy Measurement:

- Submerge the functionalized substrate and cantilever in a liquid cell filled with PBS.

- Approach the surface with the cantilever at a controlled velocity (e.g., 0.5-1 µm/s).

- Upon contact, apply a controlled contact force (100-500 pN) for a dwell time (0.1-1 s) to allow bond formation.

- Retract the cantilever at a constant velocity (0.5-1 µm/s) or a range of loading rates to probe kinetic properties.

Data Acquisition & Analysis:

- Record at least 500-1000 force-distance curves from random locations on the sample surface.

- Analyze the resulting curves using the instrument's software or custom scripts (e.g., in Igor Pro or MATLAB) to identify adhesion events.

- Extract the rupture force and rupture length for each adhesion event.

- Plot a force histogram; a peak at a characteristic force (e.g., ~50-200 pN for single FimH-mannose bonds under various loading rates) indicates a specific interaction [27].

- For catch bond analysis, perform experiments at different retraction speeds or under constant force to measure force-dependent lifetime [27].

Protocol: Functionalized Bead Assay for Shear-Dependent Adhesion

Objective: To confirm the shear-enhanced binding phenotype of pili using a macroscopic flow chamber assay with purified fimbrial tips.

Materials:

- Purified fimbrial tip complexes (e.g., containing FimH, FimG, FimF) [27]

- Fluorescent or plain latex beads (e.g., 1-10 µm diameter)

- Flow chamber system (e.g., µ-Slide I from ibidi)

- Mannosylated-BSA coating solution

- Peristaltic pump or syringe pump

Method:

- Surface Preparation: Coat the flow chamber with mannosylated-BSA (50-100 µg/mL) for 1-2 hours at 37°C, then block with 1% BSA for 1 hour to prevent non-specific binding.

- Bead Functionalization: Covalently couple purified fimbrial tip complexes to latex beads according to the manufacturer's protocol (e.g., using carbodiimide chemistry).

- Flow Assay:

- Introduce a suspension of functionalized beads into the flow chamber.

- Allow beads to settle onto the coated surface under zero or very low flow (shear stress ~0.01 Pa) for 5-10 minutes.

- Initiate flow, gradually increasing the shear stress (e.g., to 0.1 Pa).

- Monitor and image the number of firmly adherent beads at each shear stress interval using microscopy.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the number of adherent beads per field of view. A significant increase (e.g., >20-fold) in adherent beads at a higher shear stress (0.1 Pa) compared to low shear (0.01 Pa) is indicative of shear-dependent, catch-bond mediated adhesion [27].

Diagram 2: A generalized workflow for Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful investigation into the biomechanics of pili requires a specific set of reagents and tools. The following table lists essential materials and their functions in SMFS and adhesion assays.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pilus Biomechanics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Fimbrial Tip Complexes | Isolated quaternary structures of adhesin and adapter proteins (e.g., FimH-FimG-FimF). | Used in functionalized bead assays to study shear-dependent adhesion without whole bacteria [27]. |

| Functionalizable AFM Cantilevers | Probes for SMFS; can be coated with specific ligands or used to probe immobilized cells. | MLCT-BIO probes for measuring specific unbinding forces between FimH and mannose [7] [27]. |

| PEG-based Crosslinkers | Heterobifunctional crosslinkers (e.g., NHS-PEG-Maleimide) for attaching ligands to AFM tips. | Creates a flexible tether between the AFM tip and a mannosylated ligand, enabling precise force measurements [7]. |

| Mannosylated BSA | A neoglycoprotein used as a surrogate receptor for Type 1 fimbriae (FimH). | Coating surfaces in flow chambers or AFM substrates to study FimH-mediated adhesion [27]. |

| Microfluidic Flow Chambers | Devices for applying controlled laminar flow and quantifiable shear stress to adherent cells/beads. | Quantifying shear-enhanced adhesion of bacteria or functionalized beads [27]. |

| APTES ((3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane) | A silane used to create a positively charged amine-functionalized surface on glass substrates. | Promotes strong electrostatic immobilization of negatively charged bacterial cells for AFM probing [7]. |

| Acantrifoic acid A | Acantrifoic acid A|C32H48O7|Natural Triterpenoid | Acantrifoic acid A is a high-purity natural triterpenoid for research use only (RUO). Explore its potential in anti-inflammatory and pharmacological studies. |

| Ecliptasaponin D | Ecliptasaponin D, CAS:206756-04-9, MF:C36H58O9, MW:634.851 | Chemical Reagent |

Concluding Remarks

The paradigm of bacterial pili and fimbriae as force-bearing nanosprings underscores a sophisticated biological adaptation where mechanical structure dictates function in pathogenesis. The combination of SMFS, AFM, and computational modeling has been instrumental in moving from a static, structural view of these appendages to a dynamic understanding of their shock-absorbing and force-sensing capabilities. The protocols and data summarized in this Application Note provide a framework for researchers to systematically investigate these properties. Future research leveraging these tools will continue to uncover the intricate relationship between the structural biology of adhesins and their biomechanical performance, paving the way for novel anti-adhesive therapeutic strategies that target these critical virulence factors.

The adhesion of cells, whether bacterial or human, is fundamentally governed by receptor-ligand interactions that are constantly subjected to mechanical forces in physiological environments. These forces profoundly influence bond kinetics and stability, leading to two distinct categories of binding behaviors: catch-bonds and slip-bonds. Slip-bonds represent the conventional behavior where bond lifetime decreases exponentially with increasing applied force, as the mechanical work lowers the energy barrier between bound and unbound states. In contrast, catch-bonds exhibit a counterintuitive response where lifetime initially increases with force before eventually decreasing, representing a sophisticated biological mechanism for regulating adhesion under shear stress [29] [30].

The discovery and characterization of these bond types have revolutionized our understanding of cellular adhesion mechanisms, particularly in the context of bacterial colonization and infection. While slip-bonds have been widely observed across biological systems, catch-bonds have more recently emerged as a specialized adaptation that enables pathogens to fine-tune their adhesion based on local mechanical conditions [29]. This mechanoresponsive behavior allows bacteria to bind loosely and spread under low flow conditions while resisting detachment and maintaining firm attachment under high shear stress, ultimately enhancing their ability to colonize host tissues and form biofilms under dynamic fluid environments.

Fundamental Principles and Molecular Mechanisms

Quantitative Bond Characterization

The fundamental difference between catch and slip bonds can be quantitatively described through their force-dependent lifetime profiles, which are governed by distinct energy landscapes.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Catch-Bonds and Slip-Bonds

| Characteristic | Catch-Bonds | Slip-Bonds |

|---|---|---|

| Force Response | Lifetime increases then decreases with force | Lifetime decreases exponentially with force |

| Functional Advantage | Enhanced adhesion under shear; flow-dependent regulation | Facilitates detachment under stress; reversible binding |

| Typical Lifetime Range | Can extend up to several seconds under optimal force | Shortens continuously from basal lifetime (milliseconds to seconds) |

| Shear-Enhanced Adhesion | Yes | No |

| Molecular Mechanism | Allosteric regulation; force-induced conformational change | Accelerated dissociation under load |

| Biological Examples | FimH-mannose (E. coli); SpsD-Fg (S. aureus); P-selectin-PSGL-1 | Many conventional receptor-ligand pairs |

Molecular Mechanisms of Catch-Bond Behavior

The molecular basis for catch-bond behavior involves sophisticated force-induced conformational changes that enhance binding affinity under mechanical stress. In the well-characterized FimH-mannose system of uropathogenic E. coli, the adhesin consists of a pilin domain that anchors it to bacterial fimbriae and a lectin domain that binds mannose residues on host epithelial cells. Under low force conditions, the lectin domain exists in a low-affinity state. However, when subjected to tensile force, an allosteric mechanism involving the twisting of β-sheets transitions the lectin domain to a high-affinity conformation, thereby strengthening adhesion under shear stress [29].

Similarly, in Gram-positive pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus, the SpsD protein binding to fibrinogen (Fg) demonstrates an unusual catch–slip transition with remarkably strong bond strength (rupture force of ~2 nN). This interaction exhibits a characteristic pattern where bond lifetime grows with increasing force until reaching a critical threshold, beyond which it transitions to slip-bond behavior [29]. This dual response provides a mechanical adaptation that allows bacteria to remain firmly attached under varying fluid shear conditions while permitting detachment and dissemination at exceptionally high shear forces.

Experimental Characterization Using Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy

Technical Approaches and Instrumentation

The identification and characterization of catch-bonds have been enabled primarily by single-molecule force spectroscopy techniques, particularly atomic force microscopy (AFM) and optical tweezers. These methods allow precise application and measurement of piconewton-scale forces on individual receptor-ligand pairs, providing direct observation of bond kinetics under mechanical stress [30] [31].

Table 2: Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy Techniques for Catch-Bond Studies

| Technique | Force Range | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | 10–10,000 pN | 0.5–1 nm | 1 ms | High-force pulling; interaction assays; cell-cell adhesion | High force resolution; ability to image | Large minimal force; potential nonspecific binding |

| Optical Tweezers | 0.1–100 pN | 0.1–2 nm | 0.1 ms | 3D manipulation; tethered assays; molecular motors | Low noise and drift; high spatial and temporal resolution | Photodamage; sample heating |

| Magnetic Tweezers | 0.01–100 pN | 5–10 nm | 0.1–0.01 s | Tethered assays; DNA topology; force clamping | Stable force clamping; parallel measurements | Lower spatial resolution; limited manipulation |

Advanced AFM Methodologies for Cell-Adhesion Studies

The application of AFM to study cell-cell adhesion requires specialized methodologies to address the challenges associated with long-distance unbinding events and substantial cell deformations. A technical approach employing extended pulling range (up to 100 μm in the z-direction) using closed-loop, linearized piezo elements has been developed to quantify cell-cell adhesion forces without compromising imaging capabilities [32]. This system, when coupled with an inverted optical microscope equipped with a piezo-driven objective, enables simultaneous monitoring of cell morphology and force spectroscopy measurements, providing correlative data on structural changes and adhesion strength.

Critical parameters that must be controlled in AFM-based adhesion studies include contact conditions (constant force or position during determined time), pulling conditions (displacement and speed), and sufficient effective pulling range to ensure complete bond separation before system extension limits are reached [32]. These considerations are particularly important for studying bacterial adhesion, where multiple adhesins may engage simultaneously, and force-induced conformational changes can occur over extended distances.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AFM Force Spectroscopy for Bacterial Catch-Bond Characterization

This protocol details the procedure for quantifying catch-bond behavior in bacterial adhesins using single-molecule force spectroscopy with atomic force microscopy.

4.1.1 Sample Preparation

- Bacterial Probe Preparation: Immobilize bacterial cells or purified adhesins on AFM cantilevers using functionalized tips. For whole cells, use concanavalin A or similar non-inhibitory coatings to attach bacteria to tipless cantilevers. For purified adhesins, employ covalent coupling chemistry (e.g., PEG linkers) to attach proteins to sharpened tips.

- Substrate Functionalization: Prepare surfaces with relevant ligands (e.g., mannosylated surfaces for FimH studies, fibrinogen-coated surfaces for SpsD studies). Use freshly cleaved mica or gold surfaces functionalized with self-assembled monolayers presenting terminal groups for ligand immobilization.

- Control Surfaces: Include surfaces blocked with inert proteins (e.g., BSA) or lacking specific ligands to account for nonspecific interactions.

4.1.2 Force Measurement Configuration

- Cantilever Selection: Choose cantilevers with appropriate spring constants (typically 0.01-0.1 N/m for single-molecule measurements). Precisely calibrate each cantilever using thermal fluctuation methods prior to experiments.

- Buffer Conditions: Use physiologically relevant buffers (e.g., PBS or Tris buffer) with optional addition of divalent cations if required for adhesin function. Maintain temperature control at 37°C for physiological relevance.

- Approach/Retraction Parameters: Set approach velocity to 100-500 nm/s, contact force to 100-300 pN, and contact time to 0.1-1 second. Systematically vary retraction velocities from 100-10,000 nm/s to probe force-dependent kinetics.

4.1.3 Data Collection and Analysis

- Force Curve Acquisition: Collect a minimum of 1000-3000 force curves per condition to ensure statistical significance. Include adequate controls for specific binding (e.g., soluble inhibitors, adhesin-deficient mutants).

- Bond Lifetime Analysis: For observed unbinding events, plot bond lifetime against applied force to identify catch-bond characteristics (initial increase in lifetime with force followed by decrease).

- Catch-Bond Validation: Fit data to established models (e.g., two-state catch-slip model) to extract kinetic parameters. Verify specificity through inhibition controls and reproducibility across multiple biological replicates.

Protocol 2: Extended-Range AFM for Cell-Cell Adhesion Measurements

This protocol adapts AFM methodology for studying long-distance cell-unbinding events, particularly relevant for intact bacterial adhesion to eukaryotic cells.

4.2.1 Instrument Modification

- Piezo System Enhancement: Implement a sample stage with 100 μm z-range movement capability using closed-loop, linearized piezo elements to accommodate large cell deformations during detachment.

- Simultaneous Optical Monitoring: Integrate with an inverted optical microscope featuring piezo-driven objective for continuous visualization of cell morphology during force measurements.

- Environmental Control: Maintain temperature at 37°C and CO₂ at 5% (if using mammalian cells) throughout experiments using environmental chambers.

4.2.2 Cell Preparation and Mounting

- Bacterial Preparation: Culture bacterial strains under conditions that express target adhesins. Harvest during mid-log phase, wash, and resuspend in appropriate buffer.

- Eukaryotic Cell Monolayers: Culture adherent eukaryotic cells (e.g., HUVEC for endothelial studies) on appropriate substrates until 70-80% confluent.

- AFM Cantilever Functionalization: Functionalize tipless cantilevers with concanavalin A or poly-L-lysine to facilitate bacterial attachment. Attach single bacterial cells to cantilever apex using minimal contact force and time.

4.2.3 Adhesion Force Quantification

- Contact Parameters: Set contact force to 200-500 pN with contact times varying from 0.5-5 seconds to probe adhesion dynamics.

- Retraction Protocol: Use extended retraction distances (up to 50-100 μm) at constant velocities (0.5-2 μm/s) to ensure complete detachment.

- Adhesion Event Analysis: Identify specific unbinding events from force-distance curves. Quantify adhesion probability, rupture force, and work of adhesion. Classify unbinding events based on characteristic patterns (single vs. multiple ruptures).

Visualization of Catch-Bond Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

Catch-Bond Mechanism in Bacterial Adhesins

AFM Workflow for Catch-Bond Characterization

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Catch-Bond Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functionalized AFM Cantilevers | Bacterial cell or adhesin immobilization | Tipless cantilevers for whole cells; sharpened tips for single molecules | Spring constant calibration critical; appropriate surface chemistry for specific attachment |

| Ligand-Coated Substrates | Presentation of target receptors | Mannosylated surfaces for FimH; fibrinogen-coated surfaces for SpsD | Control over ligand density and orientation essential for single-molecule studies |

| Specific Inhibitors | Validation of binding specificity | Soluble mannose for FimH; monoclonal antibodies for specific epitopes | Use at multiple concentrations to demonstrate dose-dependent inhibition |

| Adhesin-Deficient Mutants | Specificity controls | FimH-negative E. coli; SpsD-negative S. aureus | Isogenic strains recommended to eliminate confounding genetic factors |

| PEG Linkers | Covalent attachment for single-molecule studies | Heterobifunctional PEG spacers | Appropriate length (typically 50-100 nm) to reduce surface interactions |

| Physiological Buffers | Maintain adhesin functionality and structure | PBS; Tris buffers with divalent cations as needed | Temperature and pH control critical for physiological relevance |

Biological Significance and Research Applications

Bacterial Pathogenesis and Virulence Strategies

Catch-bonds represent a sophisticated evolutionary adaptation that enhances bacterial virulence by enabling mechanical regulation of adhesion. For uropathogenic E. coli, the FimH-mannose catch-bond mechanism allows these pathogens to colonize the urinary tract despite high fluid shear forces, initiating infections that can lead to cystitis and pyelonephritis [29]. The catch-bond behavior ensures that bacteria remain loosely attached under low flow conditions, permitting surface exploration, while strengthening adhesion as shear stress increases, thereby resisting detachment and facilitating biofilm formation.

In staphylococcal infections, the SpsD-fibrinogen catch-bond with its exceptionally high rupture force (~2 nN) enables these pathogens to withstand extreme mechanical stress, contributing to their ability to form persistent infections on medical implants and host tissues [29]. The catch-slip transition in these systems provides a dual advantage: firm attachment under typical physiological shear stresses, with controlled detachment at extreme forces that may facilitate dissemination to new colonization sites. This mechanoresponsive adhesion represents a key virulence factor that enhances bacterial persistence in dynamic host environments.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The unique properties of catch-bonds present both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Conventional anti-adhesion approaches that target binding interfaces may be less effective against catch-bond mediated adhesion due to its force-enhanced stability. However, the allosteric nature of catch-bond mechanisms reveals potential targets for novel anti-infective strategies that lock adhesins in low-affinity states or prevent force-induced activation [29].

Future research directions include the development of catch-bond inhibitors that specifically target the allosteric regulation pathways, engineering of catch-bond mimetics for improved tissue adhesion in regenerative medicine applications, and exploitation of catch-slip transitions for designing drug delivery systems with shear-dependent release properties. The continued application of single-molecule force spectroscopy techniques, particularly with extended measurement capabilities and improved temporal resolution, will undoubtedly reveal new catch-bond systems and deepen our understanding of their role in host-pathogen interactions and microbial ecology.

From Single Molecules to Communities: AFM Methodologies for Biofilm Analysis

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS) for Probing Individual Adhesins

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS) has emerged as a powerful biophysical technique for quantifying the nanoscale forces that govern molecular interactions. Within the field of microbiology, SMFS provides unprecedented insights into the adhesion mechanisms of pathogenic bacteria, a critical first step in biofilm formation and infection development [33]. By applying controlled mechanical forces to single adhesin proteins, researchers can directly measure their binding strength, mechanical stability, and structural responses to stress. This application note details standardized protocols for investigating individual adhesins using AFM-based SMFS, with a specific focus on the mechanostable properties of bacterial adhesins such as Staphylococcus aureus bone sialoprotein-binding protein (Bbp) and Pseudomonas fluorescens large adhesin LapA [34] [35]. The quantitative data and methodologies presented herein serve as essential resources for researchers and drug development professionals working to develop novel anti-adhesion therapies.

Quantitative SMFS Data on Bacterial Adhesins

The exceptional mechanical strength of bacterial adhesins is a key factor in the resilience of biofilms. The following table summarizes single-molecule rupture forces for characterized adhesin-ligand complexes, demonstrating their remarkable mechanostability.

Table 1: Mechanostability of Bacterial Adhesin-Ligand Complexes

| Adhesin | Source Bacterium | Ligand/Target | Rupture Force (Most Probable) | Experimental Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Sialoprotein-Binding Protein (Bbp) | Staphylococcus aureus | Fibrinogen-α (Fgα) | > 2,000 pN (up to ~3,510 pN) | In silico SMFS, pulling velocity 2.5x10â»â´ nm/ps | [34] |

| Large Adhesin A (LapA) | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Anti-HA Antibody / Surface | 150 - 250 pN (WT, non-induced); 250 - 1,000 pN (LapA+ mutant) | SMFS with antibody-functionalized tips | [35] |

| SdrG | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Fibrinogen-β (Fgβ) | ~2,000 pN | In vitro SMFS | [34] |

The data reveal that certain adhesins, particularly Bbp, can withstand forces that surpass the strength of non-covalent biological complexes and even approach the realm of covalent bond strengths [34]. Furthermore, the adhesion strength is highly dependent on cellular regulation; for LapA, hyper-adherent phenotypes (LapA+ mutant) exhibit significantly higher rupture forces due to the accumulation of the adhesin on the cell surface [35].

Experimental Protocols

SMFS of Purified Adhesin-Ligand Complexes (In silico Protocol)

This protocol outlines the procedure for probing the mechanostability of an adhesin-ligand complex using steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations, as applied to the Bbp:Fgα complex [34].

- System Preparation:

- Obtain the atomic-resolution structure of the adhesin-ligand complex (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank).

- Solvate the complex in an explicit water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) and add ions to neutralize the system and achieve a physiological salt concentration.

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- Perform energy minimization using a steepest descent algorithm to remove any steric clashes.

- Carry out equilibration in two phases: first with positional restraints on the protein and ligand heavy atoms (NVT ensemble, 100 ps), followed by a second equilibration without restraints (NPT ensemble, 100 ps) to stabilize temperature and pressure.

- Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD):

- Anchoring: Fix the C-terminus of the adhesin (Bbp) by applying harmonic restraints to its Cα atoms.

- Pulling: Attach a virtual spring to the C-terminus of the ligand (Fgα). Pull the spring at a constant velocity (e.g., 2.5 × 10â»â´ nm/ps) away from the anchored adhesin.

- Replication: Perform a wide sampling of simulations (e.g., 160 replicas) to ensure statistical significance.

- Data Analysis:

- Record the force exerted on the pulling spring versus the extension of the system for each trajectory.

- Plot the data as a force-extension curve and identify the peak rupture force for each simulation.

- Construct a histogram of the rupture forces and fit it with the Bell-Evans model to determine the most probable rupture force at the given pulling velocity.

SMFS on Live Bacterial Cells

This protocol describes the use of functionalized AFM tips to probe individual adhesin molecules directly on the surface of live bacteria, as demonstrated for LapA on P. fluorescens [35].

- Sample and Probe Preparation:

- Bacterial Immobilization: Grow bacterial cells (e.g., WT and LapA+ mutant) under relevant conditions (e.g., in phosphate-rich medium to induce biofilm formation). Gently immobilize the cells on a porous polycarbonate membrane by filtration.

- AFM Tip Functionalization: a. Clean AFM cantilevers in an ozone/UV cleaner. b. Incubate the tips with a solution of aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) to create an amine-reactive surface. c. Activate the surface with a heterobifunctional crosslinker (e.g., GMBS). d. Immobilize the specific ligand (e.g., monoclonal anti-HA antibody for HA-tagged LapA) or the host protein (e.g., fibrinogen) onto the activated surface.

- Force Spectroscopy Mapping:

- Mount the functionalized AFM probe and the sample with immobilized bacteria in the liquid cell of the AFM.

- Approach the tip to the cell surface with a trigger force of ~250 pN to ensure gentle contact.

- Retract the tip at a constant velocity (e.g., 500-1000 nm/s). Record thousands of force-distance curves across multiple cells and from independent cultures.

- Data Analysis:

- Adhesion Frequency: Calculate the percentage of force curves that contain adhesion events.

- Rupture Force and Length: For curves with adhesion events, measure the magnitude of the rupture peaks and the elongation length. Plot histograms to analyze the distributions.

- Specificity Control: Perform blocking experiments by incubating the surface with free ligands or antibodies prior to measurement. Compare results with a non-adhesin expressing mutant (LapA-) to confirm the origin of the signals.

Visualization of SMFS Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and biophysical principles of the SMFS protocols described above.

SMFS on Live Bacterial Cells

In silico Steered Molecular Dynamics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful SMFS experiments require carefully selected reagents and materials. The following table lists key solutions for probing adhesins.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Adhesin SMFS

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application in SMFS | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized AFM Cantilevers | Serve as the force sensor; specific chemistry (e.g., antibody, ligand) on the tip enables probing of target adhesins. | Probing HA-tagged LapA adhesin with anti-HA antibody-coated tips [35]. |

| Polycarbonate Membranes | Provide a porous, mechanically stable substrate for immobilizing live bacterial cells without chemical fixation. | Immobilizing P. fluorescens for single-molecule and single-cell force spectroscopy [35]. |

| APTES (Aminopropyltriethoxysilane) | A silane coupling agent used to create an amine-functionalized surface on AFM tips for subsequent crosslinking. | First step in tip functionalization protocol for covalent antibody attachment [35]. |

| GMBS Crosslinker | A heterobifunctional crosslinker (N-γ-Maleimidobutyryloxy succinimide ester) that links amine-modified surfaces to thiol groups on proteins. | Covalently linking antibodies to APTES-functionalized AFM tips [35]. |

| Bell-Evans Model | A theoretical model used to analyze force spectroscopy data, relating the most probable rupture force to the loading rate. | Extracting the most probable rupture force and kinetic parameters from SMD simulation data [34] [36]. |

| Fibrinogen-α (Fgα) Peptide | The natural ligand for the Bbp adhesin; used as a binding target in both in silico and in vitro experiments. | Studying the dock, lock, and latch mechanism and mechanostability of S. aureus Bbp [34]. |

| Forsythoside E | Forsythoside E, MF:C20H30O12, MW:462.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Helicianeoide A | Helicianeoide A, MF:C32H38O19, MW:726.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS) for Whole-Cell Adhesion Measurements

Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS) is an atomic force microscopy (AFM)-based technique that enables precise quantification of cell adhesion forces at the single-cell level. Within the broader context of single-molecule force spectroscopy AFM biofilm adhesins research, SCFS provides a critical bridge between molecular-level interactions and whole-cell adhesive behavior. This technique allows researchers to quantitatively assess how microbial cells initiate surface attachment—the critical first step in biofilm formation that mediates bacterial persistence in medical, industrial, and environmental contexts [37] [23].

The fundamental principle of SCFS involves mechanically detaching a single living cell from a substrate while precisely measuring the forces involved, generating characteristic force-distance curves that reveal key adhesion parameters [38]. Recent technological advancements, particularly the development of robotic fluidic force microscopy (FluidFM), have transformed SCFS from a low-throughput technique (a few cells per day) to a high-throughput method capable of characterizing population distributions of adhesion parameters [38]. This capability is essential for understanding the inherent heterogeneity in biofilm formation and for evaluating novel antifouling strategies aimed at combating biofilm-associated infections and surface contamination [39].

Key Applications in Biofilm and Antimicrobial Research

SCFS provides unique insights into microbial adhesion mechanisms with particular relevance for biofilm and antifouling research:

- Antifouling Surface Evaluation: SCFS has demonstrated that both tripeptide-based (DOPA-Phe(4F)-Phe(4F)-OMe) and polymer-based (poly(ethylene glycol)) antifouling surfaces significantly reduce initial E. coli adhesion compared to glass surfaces, with bacteria employing different adhesion mechanisms depending on the surface chemistry [39].

- Adhesion Mechanism Elucidation: Using mutant E. coli strains deficient in specific surface appendages, SCFS has revealed that type-1 fimbriae and curli amyloid fibers mediate adhesion to different antifouling surfaces via separate mechanisms [39].

- Single-Cell Heterogeneity Assessment: SCFS measurements have uncovered significant variability in adhesion strength between individual bacterial cells, highlighting how population diversity affects biofilm formation initiation [39].

- Biofilm Assembly Studies: High-resolution AFM imaging of Pantoea sp. YR343 has revealed intricate structural details during early biofilm formation, including flagellar coordination and the emergence of honeycomb patterns, providing insights into surface attachment dynamics [23].

Quantitative Adhesion Parameters Measured by SCFS

SCFS experiments generate force-distance curves during cell detachment, from which key quantitative parameters are derived [38]:

Table 1: Key Adhesion Parameters Obtained from SCFS Force-Distance Curves

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Adhesion Force | Fmax | Highest force recorded during cell detachment | Reflects overall adhesion strength |

| Adhesion Energy | Emax | Total work required to detach the cell | Represents the energy dissipated during detachment |

| Detachment Distance | Dmax | Cantilever travel distance until Fmax | Indicates cell deformability and adhesion complex elasticity |

| Cell Contact Area | Acell | Projected area of cell-substrate contact | Relates to available area for adhesion complex formation |

| Spring Coefficient | k | Ratio of Fmax to Dmax | Represents cellular stiffness during detachment |

Population-level SCFS studies using high-throughput robotic FluidFM have revealed that single-cell adhesion parameters (Fmax, Emax, Dmax, and Acell) typically follow lognormal distributions rather than normal distributions, emphasizing the importance of measuring large cell populations to avoid misleading conclusions from small sample sizes [38].

Table 2: Representative SCFS Adhesion Measurements Across Cell Types and Conditions

| Cell Type | Substrate | Max Adhesion Force | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | RGD-coated glass | Significant increase vs. bare glass | Enhanced adhesion correlated with improved cell attachment in conventional assays | [40] |

| E. coli (wild type) | Glass | Baseline adhesion | Reference for antifouling surface comparison | [39] |

| E. coli (wild type) | Tripeptide antifouling | Significant reduction vs. glass | Effective prevention of initial bacterial adhesion | [39] |

| E. coli (wild type) | PEG polymer brush | Significant reduction vs. glass | Effective prevention of initial bacterial adhesion | [39] |

| HeLa Fucci Cells | Various stages of cell cycle | Log-normal distribution | Cell cycle-dependent adhesion with distinct mechanical properties | [38] |

Experimental Protocols for SCFS Measurements

Substrate Preparation and Functionalization

Protocol: RGD-Coated Surface Preparation for Enhanced Cell Adhesion Studies

Surface Activation:

- Clean borosilicate glass coverslips using oxygen plasma treatment or appropriate cleaning protocol

- Functionalize surfaces using activated vapor silanization (AVS) process to introduce reactive groups [40]

Peptide Decoration:

- Prepare RGD-containing peptide solution in appropriate buffer

- Immerse functionalized substrates in peptide solution

- Use EDC/NHS crosslinking chemistry to covalently attach peptides to activated surfaces [40]

- Rinse thoroughly with sterile buffer to remove unbound peptides

Quality Control:

- Verify peptide coating uniformity through control experiments

- Store functionalized substrates under appropriate conditions until use

Protocol: Antifouling Surface Preparation for Bacterial Adhesion Studies

Surface Selection:

- Prepare tripeptide DOPA-Phe(4F)-Phe(4F)-OMe surfaces using appropriate deposition methods

- Create poly(ethylene glycol) polymer-brush surfaces using established grafting protocols [39]

Surface Characterization: