Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy in Bacterial Adhesion: Protocols, Applications, and Future Directions for Antimicrobial Research

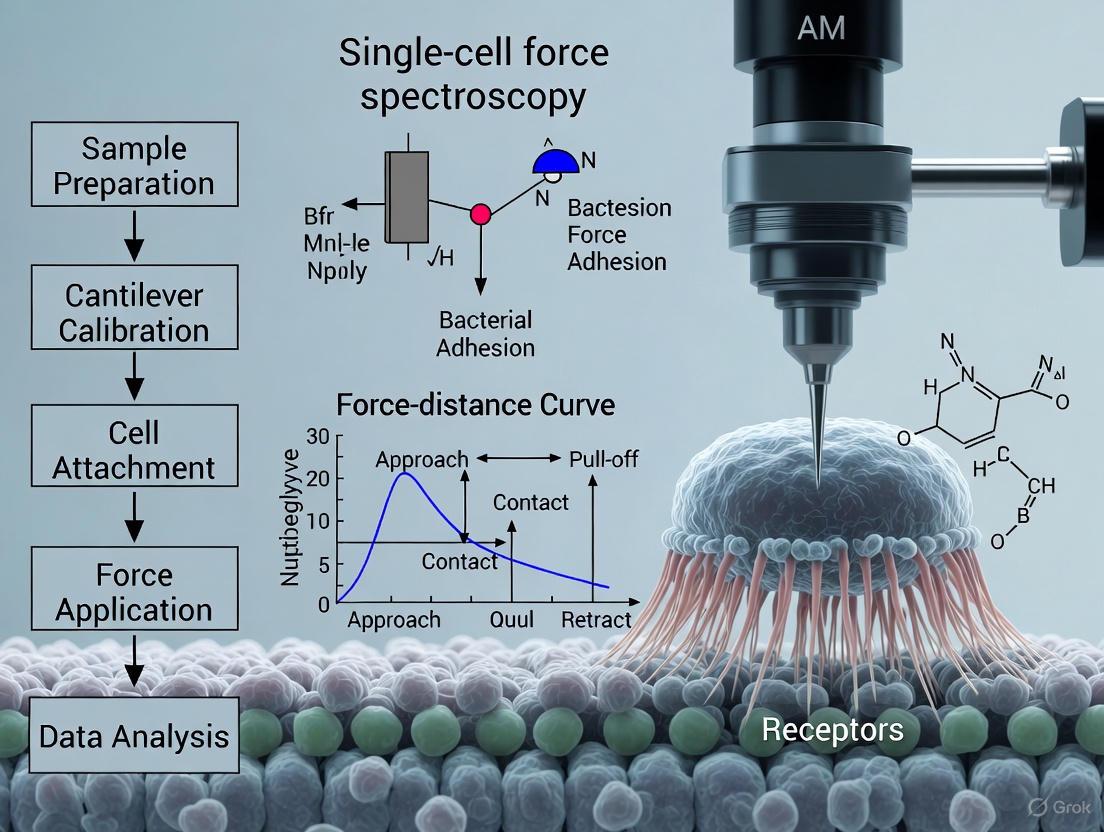

This comprehensive review explores single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) as a transformative biophysical technique for quantifying bacterial adhesion forces at the single-cell and single-molecule level.

Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy in Bacterial Adhesion: Protocols, Applications, and Future Directions for Antimicrobial Research

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) as a transformative biophysical technique for quantifying bacterial adhesion forces at the single-cell and single-molecule level. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article covers foundational principles of AFM-based force spectroscopy, detailed protocols for bacterial probe fabrication, and applications in studying pathogen-host interactions and probiotic mechanisms. It further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects for experimental optimization, validates SCFS against other biomechanical techniques, and highlights its pivotal role in developing novel anti-adhesive therapies and understanding antibiotic resistance from a biophysical perspective. The synthesis of current methodologies and findings provides an essential resource for advancing microbial mechanobiology and therapeutic discovery.

The Biophysical Foundation of Bacterial Adhesion: From Single Molecules to Cellular Interactions

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a powerful scanning probe microscopy technique that provides ultra-high resolution imaging and quantitative force measurements of surfaces under natural conditions, such as in air or liquid [1]. Its exceptional versatility has made it an indispensable tool in nanotechnology, materials science, and life sciences. A significant extension of AFM, known as force spectroscopy, enables the quantification of interaction forces at the nanoscale, from single molecules to entire living cells [2]. This technical guide details the core principles of AFM and force spectroscopy, with a specific focus on their application in single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) for bacterial adhesion research—a critical area for understanding biofilm formation, developing anti-fouling surfaces, and advancing antimicrobial strategies [3].

Fundamental Principles of Atomic Force Microscopy

Basic Operational Mechanism

The fundamental operation of an AFM involves scanning a sharp tip, mounted on a flexible cantilever, across a sample surface [4]. As the tip interacts with the surface, forces cause the cantilever to deflect. A laser beam focused on the back of the cantilever reflects onto a position-sensitive photodetector (PSPD), and nanoscale deflections alter the laser's path, allowing the PSPD to track these changes with high precision [1] [4]. By scanning the tip while maintaining a constant tip-sample interaction via a feedback loop, the AFM constructs a three-dimensional topographic map of the surface with sub-nanometer resolution [4].

Table 1: Key Components of an Atomic Force Microscope

| Component | Function |

|---|---|

| Cantilever & Tip | A flexible lever with a sharp probe that physically interacts with the sample surface. |

| Laser Diode | Emits a beam that reflects off the back of the cantilever. |

| Position-Sensitive Photodetector (PSPD) | Detects the position of the reflected laser beam, translating cantilever deflection into an electrical signal. |

| Piezoelectric Scanner | Precisely moves the tip or sample in three dimensions (x, y, z) with atomic-scale accuracy. |

| Feedback Controller | Maintains a constant interaction force by adjusting the scanner's z-position based on the PSPD signal. |

Primary Imaging Modes

AFM operates in several modes, each suited for different sample types and applications [1] [4].

- Contact Mode: The most basic mode, where the tip scans the surface in constant physical contact. The cantilever's deflection is maintained at a set value, and the Z-scanner's movement directly maps the topography [4]. While simple, this mode can exert high lateral forces, potentially damaging soft biological samples [1].

- Tapping Mode (Intermittent Contact Mode): The cantilever is oscillated at or near its resonant frequency, causing the tip to gently "tap" the surface during scanning [1]. This mode significantly reduces lateral forces compared to contact mode, making it ideal for imaging soft, fragile, or adhesive samples, including biological specimens [1].

- Non-Contact Mode: The cantilever oscillates close to the surface without making contact, sensing attractive van der Waals forces. While it minimizes sample damage, it offers lower resolution and is more challenging to operate in ambient air [1] [4].

Force Spectroscopy and Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS)

From Imaging to Force Measurement

Force spectroscopy transforms the AFM from a purely imaging instrument into a quantitative force probe. Instead of scanning, the tip is moved directly towards the sample until contact is made, and then retracted, while the interaction force is continuously recorded as a function of distance, producing a force-distance curve (FDC) [5]. Analyzing these curves reveals a wealth of information about nanomechanical properties, including adhesion, elasticity, and specific binding events [5] [4].

Principles of Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS)

SCFS is a specialized application of force spectroscopy designed to measure the adhesion forces of individual living microbial cells [2]. The core protocol involves immobilizing a single living cell on an AFM cantilever to create a cellular probe. This probe is then brought into contact with a substrate—another cell, a surface, or a protein—and retracted, allowing researchers to quantify the forces guiding microbial adhesion at the single-cell level [2]. This method has been instrumental for studying medically important microbes, including the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum and pathogens like Staphylococcus epidermidis and Candida albicans [2].

Experimental Protocols for Bacterial SCFS

This section outlines two detailed methodologies for preparing cell probes for SCFS experiments on bacteria.

Protocol 1: Single-Cell Immobilization via Electrostatic Interactions

This protocol describes a robust method for immobilizing bacteria as a monolayer on a polyethylenimine (PEI)-coated bead, which is then attached to the cantilever [3].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology [3]:

- Bead Coating: Transfer 10 μL of aminated silica beads into a solution of PEI in PBS. Shake the mixture horizontally at 150 rpm for 50 minutes. Sediment the beads and wash three times with PBS.

- Bacterial Immobilization: Incubate approximately 10 μL of the coated (PEI) beads in 1 mL of a concentrated bacterial suspension (e.g., E. coli at OD₆₀₀ = 5) for several minutes. Wash the complex three times with PBS by gentle inversion to remove non-adherent cells, forming an E. coli-PEI-bead complex.

- Quality Control: Use fluorescence microscopy (e.g., for GFP-tagged bacteria) to visualize the distribution of bacteria on the beads. Assess cell viability using a live/dead stain (e.g., propidium iodide). Only beads with a suitable monolayer of viable cells should be selected for experiments.

- Cantilever Functionalization: A tipless cantilever is assembled in the AFM, and its spring constant is calibrated. The apex of the cantilever is dipped into a thin layer of fast-curing epoxy glue for approximately 5 seconds.

- Bead Attachment: Under optical microscope observation, the glue-coated cantilever is moved towards a pre-selected E. coli-PEI-bead and contact is applied with a low force (e.g., 10 nN) for 30 seconds to attach the bead.

- Force Measurement: The cantilever with the attached cell probe is transferred to a chamber containing the substrate surface of interest. Force-distance curves are recorded using defined parameters (e.g., loading force of 10 nN, contact time of 10 s) across multiple randomly chosen areas.

Protocol 2: Direct Single-Bacterium Probing

An alternative method involves the precise handling and immobilization of a single bacterium directly onto a cantilever, often modified with a bio-compatible glue [2] [3]. This method requires a well-trained operator but can provide data from a single, well-defined cell.

Key Steps:

- Cantilever Modification: A tipless cantilever may be functionalized with a concave well or a chemical glue to facilitate single-cell capture.

- Cell Capture: The modified cantilever is carefully positioned over a single, isolated bacterium from a diluted sample and gently pressed against it to achieve immobilization.

- Validation: The successful and proper attachment of a single live cell is confirmed via microscopy.

- Measurement: The single-cell probe is used to perform force spectroscopy as described in Protocol 1.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Bacterial SCFS

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Aminated Silica Beads | Provides a solid, inert substrate for the initial electrostatic immobilization of bacterial cells via a PEI coating [3]. |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | A cationic polymer that coats the beads, creating a positive surface charge for the electrostatic attachment of generally negatively charged bacterial cells [3]. |

| Tipless Cantilever (e.g., PNP-TR-TL-Au) | The platform for the final cell probe; tipless design allows for the gluing of a bead-cell complex [3]. |

| UV-Curable Glue / Epoxy | Used for permanently attaching a silica bead or directly immobilizing a single bacterium to the cantilever [3]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Linker | A flexible, heterobifunctional crosslinker used to tether specific ligand molecules to the AFM tip for single-molecule force spectroscopy studies on membrane receptors [6]. |

Data Analysis in Force Spectroscopy

The primary data output of a force spectroscopy experiment is the force-distance curve (FDC). A standard FDC obtained during SCFS, illustrating the key events during a typical approach (red) and retraction (blue) cycle of a bacterial probe from a surface, is shown below.

Interpreting the Force-Distance Curve:

- Approach Curve (Red):

- (A→B) Non-contact region: The cantilever is free and undeflected.

- (B→C) Jump-to-contact: Attractive forces (e.g., van der Waals, electrostatic) can cause the tip to suddenly snap into contact with the surface.

- (C→D) Contact line: The cantilever deflects upwards as the sample pushes against it; the slope can provide information about the sample's stiffness [5].

- Retraction Curve (Blue):

- (D→E) Adhesion regime: As the cantilever pulls away, adhesion forces can cause it to bend downwards.

- (E) Adhesion Peak: The maximum negative force represents the adhesion or unbinding force required to separate the bacterial cell from the surface [2] [5]. This is a critical measurement in SCFS.

- (E→B) Rupture Event: The bond breaks, and the cantilever snaps back to its neutral position.

Analysis of hundreds of such curves allows for the statistical quantification of adhesion forces, binding probability, and the study of binding kinetics [2] [5] [7]. For single-molecule studies, the sawtooth pattern of force curves can reveal the sequential unfolding of protein domains [1].

Advanced Techniques: TREC-Guided Force Spectroscopy

A powerful advancement combines force spectroscopy with TREC (simultaneous Topography and RECognition imaging). In this technique, an AFM tip functionalized with a specific ligand is oscillated across a surface containing its receptors [6]. Topography and binding sites (recognition) are mapped simultaneously with nanometer resolution. Functional molecules are visually selected from the recognition image, and the AFM is switched to force spectroscopy mode to perform precise force measurements on the pre-identified target [6]. This guided approach overcomes the low-throughput nature of "blind" force mapping, especially when molecules of interest, such as membrane proteins, are sparsely reconstituted into a lipid bilayer [6].

Bacterial adhesion is the critical initial step in biofilm formation, infection, and colonization. For researchers employing single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS), understanding the interplay between specific and non-specific interactions is fundamental. These forces operate over different spatial scales and involve distinct molecular machineries. Specific interactions are characterized by precise, lock-and-key molecular recognition between adhesins and their target receptors, typically acting at short ranges (up to several nanometers) [8]. In contrast, non-specific interactions are mediated by the overall physicochemical properties of the cell surface—such as charge, hydrophobicity, and elasticity—and exert their influence over longer distances (several tens of nanometers) [8]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these mechanisms, focusing on insights gleaned from SCFS, to inform the work of scientists and drug development professionals.

Core Mechanisms of Bacterial Adhesion

The process of bacterial adhesion is governed by a combination of discrete physical forces and specific biochemical interactions. The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between these core mechanisms.

Non-Specific Interactions

Non-specific interactions are the first to come into play as a bacterium approaches a surface. They are the summed, collective effect of relatively weak pairwise interactions between all atoms in the adhering bacterium and the substratum [8].

- Lifshitz-Van der Waals Forces: These are attractive forces that originate from electromagnetic fluctuations and operate over distances of several tens of nanometers. They are always present between any two surfaces.

- Electrostatic (EL) Forces: Bacterial surfaces are generally negatively charged due to deprotonated carboxylates and phosphates in their cell wall [9]. When approaching a similarly charged surface, this creates a repulsive energy barrier that must be overcome for adhesion to occur. Attractive electrostatic forces can dominate if the surface is positively charged [8].

- Acid-Base Interactions: Also termed polar interactions, these are primarily linked to hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties. They are Lewis acid-base interactions that can be up to 10–100 times stronger than the combined EL and Lifshitz-Van der Waals forces, playing a decisive role in the final approach [10]. The hydrophobic effect is a major contributor to this interaction type.

The combined effect of these forces is often described by the Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (DLVO) theory and its extension, the XDLVO theory, which incorporates the critical acid-base component [10] [8]. The transition from reversible to irreversible adhesion is mediated by short-range forces and specific molecular binding [11].

Specific Interactions

Specific interactions are defined by stereochemical complementarity between bacterial adhesins and host or surface receptors. They are responsible for the irreversible locking of bacteria to a surface and are a key virulence factor for pathogens [8] [12].

- Mechanism: These interactions involve highly evolved bacterial surface structures, such as fimbriae, pili, and membrane-anchored proteins (e.g., MSCRAMMs in Gram-positive bacteria), binding to specific ligands like extracellular matrix proteins (fibronectin, collagen), host cell surface glycans, or complementary structures on other bacteria (coaggregation) [9] [13].

- Force Response: A remarkable feature of many specific adhesins is their mechanoresponsive behavior. Some, like the staphylococcal SdrG-fibrinogen complex, form extremely strong "dock, lock, and latch" bonds that can resist forces of 1-2 nN [13]. Others exhibit catch-bond behavior, where bond lifetime increases under applied force, allowing bacteria to resist hydrodynamic shear forces in environments like the gut [13] [14].

Quantitative Force Spectroscopy Data

Single-cell and single-molecule force spectroscopy (SCFS/SMFS) have been instrumental in quantifying the forces involved in bacterial adhesion. The table below summarizes key adhesion force measurements for various bacterial systems.

Table 1: Bacterial Adhesion Forces Measured by Force Spectroscopy

| Bacterial System / Interaction | Specific vs. Non-Specific | Measured Force | Experimental Conditions & Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus to fibrinogen (via SdrG) | Specific | ~1-2 nN | "Dock, lock, and latch" mechanism; extreme mechanical stability. | [13] |

| E. coli to 58S Bioactive Glass | Primarily Non-specific | ~6 nN | Initial transient adhesion (contact time <1s); attributed to more adhesive nanodomains. | [15] |

| S. aureus to 58S Bioactive Glass | Primarily Non-specific | ~3 nN | Initial transient adhesion (contact time <1s); weaker than E. coli under these conditions. | [15] |

| S. mutans with Antigen I/II to salivary pellicle | Specific | Median: -0.4 nN (pH 6.8) | Significant increase vs. non-specific control; wide force distribution indicates heterogeneity. | [8] |

| S. mutans without Antigen I/II to salivary pellicle | Non-specific | Median: -0.1 nN (pH 6.8) | Represents the baseline, non-specific interaction force. | [8] |

| R. champanellensis Dockerin:Cohesin (Doc:Coh) | Specific | ~500 pN (Mode A), ~200 pN (Mode B) | Dual binding modes with catch-bond behavior; role in gut adhesion under flow. | [14] |

| Coaggregation (e.g., Actinomyces & Streptococcus) | Specific | Mean: -3.0 to -4.0 nN | Significantly stronger than non-specific intergeneric aggregation forces. | [8] |

The data reveals that while specific interactions can generate extremely high forces (nN range), non-specific interactions provide a foundational adhesive force that is essential for initial contact. Furthermore, the distribution of forces is often wide and non-parametric, reflecting significant phenotypic heterogeneity within a clonal population [16] [8].

Methodologies for Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy

Core Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Techniques

AFM is a versatile platform for probing bacterial adhesion. The heart of the instrument is a nanoscale tip on a soft cantilever, whose deflection is monitored by a laser. Two primary methodologies are employed:

- Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS): A single live bacterial cell is chemically attached to the AFM cantilever. This cell is then approached into contact with a substrate (e.g., a protein-coated surface, another cell, or a biomaterial) and then retracted. The force-distance (F-D) curves obtained during retraction quantify the total adhesion force between the entire cell and the substrate, encompassing both specific and non-specific contributions [13] [12]. This method best mimics real-life adhesion conditions.

- Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS): The AFM tip is functionalized with a specific ligand (e.g., a host protein like fibronectin). The tip is then used to probe a surface onto which bacteria or their purified adhesins are immobilized. By analyzing individual rupture events in the F-D curves, the unbinding force and kinetics of a single receptor-ligand pair can be determined with high precision [13] [8].

Detailed SCFS Protocol for Probing Bacteria-Biomaterial Adhesion

The following workflow details a typical SCFS experiment designed to quantify the early-stage adhesion of bacteria to a biomaterial, such as bioactive glass [15].

Key Reagents and Parameters:

- Bacterial Strain: Late exponential phase cultures are typically used to ensure consistent surface properties [10] [15].

- Functionalization Agents: Poly-L-lysine (0.1% w/v) or polyethyleneimine (PEI) are commonly used as non-specific, cationic adhesives to firmly trap the negatively charged bacterial cell on the cantilever [13].

- Buffers: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at physiological pH (7.2-7.4) is standard. Buffer ionic strength is critical as it screens electrostatic non-specific interactions.

- AFM Parameters: A contact force of 200-500 pN is used to ensure gentle but consistent contact. Contact time is a critical variable, often set from milliseconds to seconds to study the dynamics of bond formation [15]. A retraction velocity of 0.5-1.0 µm/s is typical, though varying this parameter allows for the study of kinetic processes.

SMFS Protocol for Single-Molecule Recognition

To isolate specific molecular recognition forces, the protocol is modified:

- Tip Functionalization: The AFM tip is covalently coated with a specific ligand (e.g., fibrinogen) using heterobifunctional crosslinkers like PEG-NHS esters, which provide a flexible tether [14].

- Surface Preparation: Purified adhesins or whole bacteria are immobilized on a solid support (e.g., gelatin-coated glass or mica) [16] [8].

- Data Analysis: Thousands of F-D curves are collected. Specific unbinding events are identified by their characteristic rupture length (related to the PEG tether) and their specific blockade by free ligand in solution (competitive inhibition) [8] [14].

Advanced Concepts: Heterogeneity and Catch Bonds

Phenotypic Heterogeneity in Adhesion

SCFS has revealed that isogenic bacterial populations are not uniform. Individual cells can exhibit vastly different adhesive and mechanical properties. A key factor is the composition of the cell envelope. For instance, in E. coli, partial removal of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with EDTA homogenizes the outer membrane, rendering it smoother and significantly reducing cell-to-cell heterogeneity in adhesion forces and elasticity [16]. This demonstrates that the structural and chemical diversity of the outer membrane is a primary determinant of phenotypic heterogeneity, which has profound implications for a population's ability to adapt to varied environments and antimicrobial stressors [16].

Catch Bond Mechanisms

Catch bonds are counter-intuitive interactions whose lifetime increases with applied force up to a certain threshold, functioning as a mechanical band-pass filter. They are crucial for bacterial adhesion under shear stress, such as in the gut or urinary tract [13] [14].

Table 2: Molecular Mechanisms of Catch Bonds in Bacterial Adhesion

| Adhesin System | Bacterial Species | Proposed Molecular Mechanism | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| FimH | Escherichia coli | Force-induced conformational change from a low-affinity to a high-affinity state. | Mediates shear-enhanced adhesion to mannosylated surfaces in the urinary tract. |

| SdrG | Staphylococcus aureus | "Dock, lock, and latch" mechanism; force directs unbinding along a high-energy pathway. | Resists extreme physical stresses during infection. |

| Rc Doc:Coh | Ruminococcus champanellensis | Dual binding modes and mechanical allostery from an adjacent X-module domain. | Anchors bacterial cellulosome to cellulose fibers in the human gut under hydrodynamic flow. |

The Dockerin:Cohesin (Doc:Coh) complex from R. champanellensis provides a sophisticated example. This complex assembles in two discrete binding modes with different mechanical strengths (one breaking at ~500 pN, the other at ~200 pN). A neighboring X-module domain acts as a mechanical switch, allosterically inhibiting the low-force pathway at high loading rates. This results in a net catch bond behavior, where the probability of the strong binding mode increases with force, ensuring firm adhesion under high shear [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Bacterial Adhesion Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tipless AFM Cantilevers | The base for creating cell- or molecule-functionalized probes. | Typically made of silicon or silicon nitride; require functionalization before use. |

| Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) / PEI | Non-specific adhesives for immobilizing bacterial cells to cantilevers. | PLL is common; PEI provides stronger electrostatic attachment. |

| PEG-based Crosslinkers | For covalent, site-specific attachment of ligands to AFM tips in SMFS. | Provide a flexible tether to isolate single-molecule forces. |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA) | A chelating agent used to selectively remove Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from Gram-negative outer membranes. | Tool for studying the role of LPS in adhesion and mechanics [16]. |

| Bioactive Glass (58S Composition) | A biomaterial with known antimicrobial and bioactive properties. | Used as a substrate to study bacteria-biomaterial interactions and design anti-fouling surfaces [15]. |

| Recombinant Adhesins & Ligands | Purified proteins (e.g., Fibrinogen, Fibronectin, Coh, Doc) for SMFS and inhibition assays. | Essential for probing specific interactions and mapping binding pathways. |

| Oleonuezhenide | Oleonuezhenide, CAS:112693-21-7, MF:C48H64O27, MW:1073.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| IRF1-IN-1 | IRF1-IN-1, MF:C22H24N4O4S, MW:440.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Critical Role of Bacterial Adhesion in Infection and Biofilm Formation

Bacterial adhesion represents the critical first step in the establishment of chronic infections and the formation of biofilms, which are structured microbial communities responsible for significant healthcare challenges. This initial attachment determines the success of all subsequent stages of biofilm development, ultimately influencing infection outcomes and therapeutic efficacy. Single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) has emerged as a powerful biophysical technique that enables the quantitative investigation of adhesive interactions at the level of individual bacterial cells, providing unprecedented insights into the nanoscale forces governing these processes. Within the context of a broader thesis on SCFS of bacterial adhesion research, this technical guide examines the fundamental mechanisms, measurement methodologies, and implications of bacterial adhesion, offering a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to address biofilm-associated infections.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Bacterial Adhesion

The process of bacterial adhesion to surfaces involves a complex interplay of physicochemical forces and specific molecular interactions. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing strategies to control biofilm formation.

Physicochemical Interactions in Initial Attachment

Initial bacterial attachment is governed by nonspecific physicochemical interactions that occur before the formation of more specific molecular bonds. These interactions can be categorized as:

Long-range forces (>50 nm): These non-specific forces, including van der Waals and electrostatic interactions, are primarily responsible for transporting bacteria to the surface [15]. The Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (DLVO) theory is often applied to understand these interactions, which combine both attractive and repulsive components [17].

Short-range forces (<5 nm): These include chemical bonds such as hydrogen bonding, ionic, dipole, and hydrophobic interactions that come into play once the bacterium approaches the surface more closely [15]. The transition from long-range to short-range interactions marks the shift from reversible to irreversible adhesion.

Molecular Determinants of Specific Adhesion

Following initial attachment, specific molecular interactions mediate stronger, more stable adhesion through specialized bacterial surface components:

Gram-positive adhesins: These bacteria express "Microbial Surface Components Recognizing Adhesive Matrix Molecules" (MSCRAMMs) and pilus fibers formed by covalently bonded pilin units [15]. Staphylococcus aureus, a prominent gram-positive pathogen, utilizes fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPs) and other MSCRAMMs to bind to host matrix proteins that coat implant surfaces [18].

Gram-negative adhesins: These bacteria express fimbrial, non-fimbrial, and discrete polysaccharide adhesins [15]. Their outer membrane composition, particularly lipopolysaccharides (LPS), significantly influences stiffness and adhesion strength [15].

Influence of Surface Properties

Material surface characteristics profoundly impact bacterial adhesion through multiple physical parameters:

Surface charge: Most bacteria possess a net negative charge due to functional groups on their cell wall, typically leading to increased adhesion on positively charged surfaces [19]. However, some bacteria can overcome electrostatic repulsion through surface appendages like fimbriae, and lipopolysaccharides in gram-negative bacteria can facilitate adhesion to negatively charged surfaces [19].

Surface wettability, roughness, and stiffness: These properties collectively influence adhesion outcomes by affecting the thermodynamic compatibility between the bacterial cell and the substrate [19]. Recent research on hydro-softened chitosan demonstrated that reducing stiffness from 85 MPa to 1.8 MPa significantly enhanced bacterial adhesion, highlighting the importance of mechanical properties in adhesion processes [17].

Table 1: Influence of Surface Properties on Bacterial Adhesion

| Surface Property | Effect on Bacterial Adhesion | Underlying Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Charge | Generally increased adhesion to positively charged surfaces | Electrostatic attraction overcoming bacterial net negative charge [19] |

| Wettability | Variable effects depending on bacterial species and surface chemistry | Modulation of hydrophobic interactions and interfacial energy [19] |

| Roughness | Enhanced adhesion to moderately rough surfaces | Increased surface area and protection from shear forces [19] |

| Stiffness | Increased adhesion on softer substrates | Reduced energetic barrier for deformation and interface formation [17] |

| Topography | Can either enhance or inhibit adhesion depending on feature size | Physical confinement or guidance of bacterial cells [19] |

Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy: Methodologies and Protocols

Single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) represents a specialized application of atomic force microscopy (AFM) that enables the direct quantification of adhesion forces between individual bacterial cells and surfaces of interest. This section details the experimental protocols and methodological considerations for effective SCFS implementation.

Core SCFS Protocol

The standard protocol for microbial SCFS involves several critical steps that must be carefully optimized for reproducible results [2]:

Cantilever Functionalization: AFM cantilevers are prepared with appropriate chemistry to facilitate bacterial immobilization. Common approaches include coating with polydopamine or concanavalin A, which provide nonspecific adhesion sites while maintaining cell viability.

Single-Cell Immobilization: A single living bacterial cell is attached to the functionalized cantilever using micromanipulation under optical control. Proper immobilization ensures the cell maintains its native surface properties and physiological state throughout force measurements.

Force Curve Acquisition: The cellular probe is brought into contact with the substrate with controlled force and contact time, then retracted while recording the cantilever deflection. This process is repeated multiple times at different locations to gather statistically significant data.

Data Analysis: Force-distance curves are analyzed to extract quantitative parameters including adhesion force (maximum force required for detachment), work of adhesion (area under the retraction curve), and rupture events (discrete unbinding events indicating specific molecular interactions).

With proper training, researchers can typically master this complete protocol within approximately one week, enabling robust and reproducible measurements [2].

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Several technical factors must be carefully controlled to ensure reliable SCFS measurements:

Contact time: Systematic variation of contact time provides insights into bond maturation and the transition from reversible to irreversible adhesion. Studies have shown substantial bonding between bacteria and bioactive glass within the initial one second of contact, with multiple binding events observable at intervals as short as 250 ms [15].

Environmental conditions: Measurements should ideally be performed in physiologically relevant media, as solution chemistry significantly influences electrostatic interactions and molecular binding events.

Cantilever selection: Cantilever spring constant must be appropriately matched to the expected adhesion forces, with softer cantilevers (lower spring constants) providing higher force sensitivity for measuring weak interactions.

Temporal resolution: Recent advancements in cantilever design and detection systems have dramatically improved temporal resolution. Custom-modified cantilevers now enable measurements with approximately 1-μs resolution, allowing observation of previously inaccessible rapid transitions in adhesion processes [20].

Advanced SCFS Applications

Beyond basic adhesion force quantification, SCFS can be extended to more sophisticated investigations:

Bond lifetime studies: By applying constant force and measuring the time until detachment, researchers can probe the kinetic stability of bacterium-surface bonds.

Spatial mapping: Performing force measurements across a grid of points on a surface enables the creation of adhesion maps with nanoscale resolution.

Single-molecule force spectroscopy: Using tips functionalized with specific molecules rather than whole cells allows investigation of individual receptor-ligand interactions involved in bacterial adhesion.

Quantitative Adhesion Forces: Experimental Data

SCFS provides quantitative measurements of bacterial adhesion forces that offer fundamental insights into the interactions between pathogens and biomaterials. The following data represent key findings from recent investigations utilizing this technique.

Adhesion Force Magnitudes

Bacterial adhesion forces measured by SCFS typically fall within characteristic ranges that depend on the specific bacterial strain, surface properties, and environmental conditions:

Gram-positive bacteria: SCFS studies have revealed binding strengths in the range of approximately 0.05 to 2 nN for gram-positive adhesin-ligand interactions [15]. For Staphylococcus aureus adhering to 58S bioactive glass, mean adhesion forces of approximately 3 nN have been recorded [15].

Gram-negative bacteria: Gram-negative species often exhibit stronger adhesion forces compared to gram-positive bacteria. Escherichia coli demonstrated adhesion forces of approximately 6 nN to 58S bioactive glass, roughly double the force measured for S. aureus under identical conditions [15]. This difference may be attributed to the presence of more adhesive nano-domains distributed uniformly on the E. coli surface [15].

Comparative studies: Research comparing adhesion between stainless steel 316 and different bacterial types found higher adhesion for gram-negative bacteria (7.88-8.53 nN) compared to gram-positive bacteria (1.44 nN) over contact times of 0-60 seconds [15].

Table 2: Bacterial Adhesion Forces Measured by Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy

| Bacterial Species | Surface Material | Adhesion Force (mean) | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) | 58S Bioactive Glass | ~3 nN | Contact time: 0-1 s [15] |

| Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) | 58S Bioactive Glass | ~6 nN | Contact time: 0-1 s [15] |

| Gram-positive bacteria | Stainless Steel 316 | 1.44 ± 0.21 nN | Contact time: 0-60 s [15] |

| Gram-negative bacteria | Stainless Steel 316 | 7.88-8.53 nN | Contact time: 0-60 s [15] |

| Gram-positive adhesin-ligand interactions | Various | 0.05-2 nN | Multiple studies [15] |

Temporal Dynamics of Adhesion

The duration of contact between bacteria and surfaces significantly influences adhesion forces through bond maturation processes:

Rapid bond formation: Studies have detected substantial bonding between bacteria and bioactive glass within the first second of contact, with multiple binding events observable at intervals as brief as 250 milliseconds [15].

Force-time relationship: Adhesion forces increase exponentially with contact time before eventually plateauing according to the function: F(t) = F0 + (F∞ - F0)exp(-t/τk), where F(t) is adhesion force at time t, F0 is initial adhesion force before bond maturation, F∞ is adhesion force after bond strengthening, and τk is the characteristic time constant [15].

Transition to irreversible adhesion: Increased contact time promotes the transition from reversible to irreversible adhesion, characterized by an increase in the number of minor peaks observed in force-distance curves, indicating multiple simultaneous binding events [15].

Impact of Material Composition and Crystallinity

Surface composition and structure significantly influence bacterial adhesion forces:

Bioactive glass 58S: This composition (with high calcium content and absence of sodium) exhibits excellent bioactivity and antibacterial behavior, with amorphous BAG demonstrating greater bacterial inhibition compared to semi-crystalline glass-ceramics [15].

Hydro-softened materials: Reducing the stiffness of chitosan thin films from 85 MPa to 1.8 MPa through hydro-softening resulted in over 5-fold greater bacterial adhesion compared to unsoftened films, primarily through increased single-cell attachment rather than aggregated colonization [17].

From Initial Adhesion to Biofilm Formation

The transition from initial bacterial adhesion to mature biofilm represents a critical developmental sequence that determines the trajectory of infection and therapeutic challenges.

The Biofilm Lifecycle

Biofilm formation follows a defined progression through distinct developmental stages [21]:

Initial attachment: Planktonic cells adhere to surfaces through reversible physicochemical interactions. Recent evidence indicates that initial seeding often occurs through clumps of cells that represent aggregates formed in vivo or fragments dispersed from existing biofilms, rather than single cells [21].

Irreversible attachment: Following initial contact, bacteria commit to the surface through stronger, irreversible attachments mediated by molecular interactions such as adhesin-receptor binding.

Microcolony formation: Attached cells proliferate and aggregate into three-dimensional clusters, initiating intercellular communication and collective behavior.

Biofilm maturation: The developing biofilm architecture becomes more complex with the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that form a protective matrix. This matrix can comprise over 90% of the biofilm mass and consists of polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA, and other biopolymers [21].

Dispersion: Controlled detachment of cells or biofilm fragments enables colonization of new surfaces, completing the cycle and spreading the infection [21].

Antimicrobial Resistance in Biofilms

The biofilm microenvironment confers remarkable tolerance to antimicrobial agents through multiple interconnected mechanisms [21]:

Physical barrier function: The extracellular matrix acts as a protective barrier that can hinder antibiotic penetration into the biofilm structure. Some antibiotics form complexes with matrix components or are degraded by enzymes within the matrix, reducing effective concentrations at the bacterial cell surface [21].

Altered microbial physiology: Biofilm-embedded cells often exhibit reduced metabolic activity and growth rates, making them less susceptible to antibiotics that target active cellular processes.

Horizontal gene transfer: The close proximity of cells within biofilms facilitates efficient exchange of resistance genes, accelerating the development and spread of antimicrobial resistance [21].

Persister cells: Biofilms typically contain subpopulations of dormant persister cells that exhibit extreme tolerance to antimicrobial treatments and can reseed the infection after therapy cessation.

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

This section details critical experimental tools and methodologies employed in bacterial adhesion and biofilm research, providing a practical resource for investigators in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Bacterial Adhesion and Biofilm Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy | Atomic Force Microscopy with SCFS capability | Quantification of adhesion forces at single-cell level; bond kinetics; spatial mapping of adhesion [2] | Requires specialized instrumentation and expertise; contact time and environmental control critical [2] |

| Advanced Cantilevers | FIB-modified ultrashort cantilevers (L = 9 μm) | High-temporal resolution (1 μs) force measurements; protein folding studies [20] | Challenging detection on commercial AFMs; requires custom detection systems [20] |

| Bioactive Materials | 58S Bioactive Glass (60% SiOâ‚‚, 36% CaO, 4% Pâ‚‚Oâ‚…) | Antimicrobial surface research; bone regeneration studies; dental applications [15] | Amorphous form shows greater bacterial inhibition than crystalline [15] |

| Surface Modification | Hydro-softened chitosan thin films | Studying effect of substrate mechanics on bacterial adhesion; tunable stiffness platforms [17] | 5-fold adhesion increase on softened films (1.8 MPa vs. 85 MPa) [17] |

| Anti-adhesion Agents | Marine Glycomyces sediminimaris extracts (Diketopiperazines) | Dental plaque prevention; anti-adhesion studies without bactericidal effect [22] | 95.1% reduction in S. mutans adhesion; negligible hemolytic activity [22] |

| Analytical Techniques | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with image analysis | Quantitative adhesion assessment; morphological classification of adherent bacteria [17] | Requires careful sample preparation; enables single-cell vs. aggregate discrimination [17] |

| IRF1-IN-2 | IRF1-IN-2, MF:C18H20N2O4S, MW:360.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Urease-IN-6 | N-[2-(1H-Indol-3-yl)ethyl]-N'-(4-methoxyphenyl)thiourea | High-purity N-[2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl]-N'-(4-methoxyphenyl)thiourea for research use only (RUO). Explore its potential in pharmaceutical and biological applications. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Bacterial adhesion represents the critical determinative step in the establishment of biofilm-associated infections, serving as the foundational event upon which all subsequent pathogenic processes build. Single-cell force spectroscopy has revolutionized our understanding of this process by providing quantitative, nanoscale measurements of the forces governing bacterial attachment to surfaces. The integration of SCFS with complementary analytical approaches continues to reveal new insights into the molecular mechanisms, temporal dynamics, and material determinants of bacterial adhesion. As research in this field advances, the ongoing development of high-resolution techniques, combined with innovative anti-adhesion strategies targeting the initial attachment phase, holds significant promise for addressing the persistent challenge of biofilm-associated infections in clinical settings. The continued refinement of these methodologies will undoubtedly yield new opportunities for therapeutic intervention and biomaterial design in the ongoing effort to mitigate the substantial burden of biofilm-related diseases.

Single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) has emerged as a pivotal technique in bacterial adhesion research, enabling the quantitative assessment of interaction forces at the single-cell level. This guide explores the fundamental parameters—rupture forces, loading rates, and bond strength—that govern bacterial adhesion, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a technical framework for understanding these critical interactions. Within the broader context of bacterial adhesion research, SCFS offers unprecedented insights into the initial attachment phases of bacteria to both biotic and abiotic surfaces, a process fundamental to biofilm formation, infection, and environmental colonization [23]. The measurement and interpretation of these parameters are essential for developing novel antibacterial surfaces, anti-fouling coatings, and therapeutic interventions that target the earliest stages of bacterial colonization.

The adhesion of bacteria to surfaces is a complex, multi-stage process beginning with reversible attachment mediated by physicochemical forces, followed by irreversible adhesion and eventual biofilm formation [24]. SCFS, typically performed using atomic force microscopy (AFM), allows researchers to probe these initial interactions with high spatial and temporal resolution, providing data that bulk methods often obscure through averaging effects [16]. By quantifying the forces required to detach individual bacterial cells from substrates, researchers can elucidate the molecular mechanisms of adhesion, assess the efficacy of anti-adhesive surfaces, and understand how surface properties influence bacterial behavior—all critical considerations for pharmaceutical and medical device development.

Key Parameters in Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy

Rupture Forces

Rupture force, often referred to as adhesion force, represents the maximum force required to separate a bacterial cell from a substrate after contact. In SCFS experiments, this parameter is directly measured from the retraction curve of force-distance measurements as the minimum force value before complete detachment [23]. Rupture forces arise from the combined contributions of various interactions, including specific ligand-receptor bonds, nonspecific physicochemical interactions, and the mechanical properties of cellular appendages.

The magnitude of measured rupture forces provides insights into the nature and strength of bacterial adhesion. For example, studies of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) on Arabidopsis thaliana roots revealed adhesion forces following a lognormal distribution with geometric means varying by bacterial species and root zone [23]. Bacillus velezensis exhibited forces of 68.8 ×/÷ 2.0 pN in the cell division zone, 95.6 ×/÷ 2.4 pN in the elongation zone, and 102.3 ×/÷ 2.3 pN in the maturation zone, while Pseudomonas defensor showed different zone-dependent adhesion patterns [23]. These variations highlight how adhesion is influenced by both bacterial surface properties and substrate characteristics.

In studies of bacterial adhesion to biomaterials, significantly higher forces have been observed. Research on 58S bioactive glass demonstrated adhesion forces of approximately 3 nN for Staphylococcus aureus and 6 nN for Escherichia coli after just one second of contact time [15]. These substantial forces, measured in the nanonewton range, indicate strong initial bonding between bacteria and implant surfaces, which may contribute to the development of implant-related infections.

Loading Rates

The loading rate, defined as the rate at which force is applied during detachment, critically influences measured rupture forces in bond strength assessments. In SCFS, the loading rate is controlled by the retraction speed of the AFM cantilever and its spring constant. This parameter is particularly important because many biological bonds exhibit slip-bond behavior, where bond lifetime decreases with increasing force, or catch-bond behavior, where bond lifetime initially increases with force.

The relationship between loading rate and measured adhesion force provides insights into the energy landscape of receptor-ligand interactions. As loading rate increases, the force required to rupture bonds typically increases because the system has less time to dissociate spontaneously under thermal fluctuations. This dependence can reveal the presence of multiple energy barriers in the interaction pathway and provide estimates of bond dissociation rates and potential widths [15].

In bacterial adhesion studies, loading rates must be carefully controlled to enable meaningful comparisons between experiments. Standardized approach and retraction speeds allow researchers to mimic physiological conditions, such as the shear forces bacteria experience in fluid environments, thereby providing biologically relevant data on adhesion strength [24].

Bond Strength

Bond strength in bacterial SCFS encompasses both the adhesion force and the work of adhesion, which represents the total energy dissipated during the detachment process. This parameter is influenced by multiple factors, including the number of bonds formed, their individual strengths, and the mechanical properties of the interacting surfaces.

The strength of bacterial adhesion is not static but evolves over time through a process known as bond maturation. The temporal evolution of adhesion force follows the relationship: F(t) = F0 + (F∞ - F0)exp(-t/τk), where F0 is the initial adhesion force, F∞ is the force after bond strengthening, t is time, and τk is the characteristic time constant [15]. This equation describes the exponential increase in adhesion strength as contact time increases, eventually plateauing as bonds reach their maximum strength.

Bond strength in bacterial systems is governed by various molecular mechanisms, including the stretching of polymeric structures such as adhesins, polysaccharides, and other surface macromolecules. Force curves often exhibit characteristic patterns described by polymer elasticity models, particularly the worm-like chain (WLC) model, which quantifies the forced unfolding of these biomolecules [23].

Quantitative Data in Bacterial SCFS

Adhesion Force Measurements Across Bacterial Systems

Table 1: Measured Bacterial Adhesion Forces in Various Systems

| Bacterial Species | Substrate | Adhesion Force | Distribution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus velezensis | A. thaliana root division zone | 68.8 ×/÷ 2.0 pN | Lognormal | [23] |

| Bacillus velezensis | A. thaliana root elongation zone | 95.6 ×/÷ 2.4 pN | Lognormal | [23] |

| Bacillus velezensis | A. thaliana root maturation zone | 102.3 ×/÷ 2.3 pN | Lognormal | [23] |

| Escherichia coli | 58S Bioactive glass | ~6 nN | Not specified | [15] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 58S Bioactive glass | ~3 nN | Not specified | [15] |

| E. coli (untreated) | Gelatin-coated glass | 0.53 nN | Heterogeneous | [16] |

| E. coli (EDTA-treated) | Gelatin-coated glass | 0.28 nN | Reduced heterogeneity | [16] |

Temporal Evolution of Adhesion Forces

Table 2: Time-Dependent Adhesion Parameters in Bacterial Systems

| Parameter | Effect on Adhesion | Experimental Evidence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contact time (0-1s) | Rapid increase in adhesion force | Force increased from ~2 nN to ~6 nN for E. coli on bioactive glass | [15] |

| Bond maturation | Exponential strengthening | F(t) = F0 + (F∞ - F0)exp(-t/τk) | [15] |

| Initial adhesion phase | Linear increase in cell attachment | Linear adhesion rates for first 5-9 minutes under flow | [24] |

| Extended adhesion | Rate decrease due to surface coverage | 55% average reduction in adhesion rate after initial phase | [24] |

Experimental Protocols in Bacterial SCFS

Bacterial Immobilization for SCFS

The reliable immobilization of bacterial cells without altering their surface properties is crucial for reproducible SCFS measurements. The following protocol has been successfully used for studying PGPR adhesion to plant roots:

Cantilever Functionalization: Attach a colloidal probe to a tipless AFM cantilever and coat it with positively charged polyethyleneimine (PEI) to promote bacterial attachment [23].

Cell Attachment: Incubate the functionalized cantilever with a bacterial suspension of approximately 10^6 CFU/mL for 30 minutes, allowing a single bacterium to attach to the center of the colloidal probe [23].

Viability Confirmation: Verify bacterial viability and positioning using fluorescence microscopy after staining with appropriate viability markers [23].

Force Spectroscopy: Approach the immobilized bacterium toward the substrate of interest (e.g., root surface) using a controlled indentation force of 500 pN and a contact time of approximately 100 ms to mimic initial encounters during colonization [23].

This immobilization approach preserves bacterial viability and surface properties while providing sufficient stability for force measurements. The use of PEI coating creates a strong electrostatic attachment that withstands the forces applied during measurement without compromising cellular integrity.

Force Curve Acquisition and Analysis

The acquisition and interpretation of force-distance curves form the foundation of SCFS data collection:

Curve Collection: Record approach and retraction curves at multiple locations on the substrate surface (typically 100+ curves per condition) to account for spatial heterogeneity [23].

Curve Categorization: Classify retraction curves into two primary categories: (i) "with specific interaction" showing adhesive events, and (ii) "with noninteraction" showing flat curves or sharp peaks at distances <300 nm indicative of nonspecific interactions [23].

Adhesion Quantification: For curves showing specific interactions, quantify the adhesion force (rupture force), rupture length, and work of adhesion [23].

Polymer Elasticity Modeling: Fit force curves with the worm-like chain (WLC) model of polymer elasticity to analyze the forced unfolding of surface macromolecules [23].

Statistical Analysis: Account for the typically lognormal distribution of adhesion forces by performing logarithmic transformation before statistical testing to meet the assumptions of parametric tests [23].

This systematic approach to data collection and analysis ensures robust quantification of adhesion parameters and facilitates comparisons across different experimental conditions and bacterial systems.

LPS Removal to Assess Membrane Contributions

The role of outer membrane components in bacterial adhesion can be assessed through selective removal of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in Gram-negative bacteria:

Culture Preparation: Grow Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 in Luria-Bertani broth for 24 hours at 37°C with shaking at 150 rpm [16].

LPS Removal: Harvest cells by centrifugation at 2151 × g for 5 minutes, wash with Milli-Q water, then resuspend in 100 mM EDTA solution (pH 8.0) and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes with gentle shaking [16].

Post-treatment Processing: Recentrifuge under the same conditions, wash twice with Milli-Q water, and resuspend in 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for analysis [16].

Viability Assessment: Verify membrane integrity post-treatment through AFM imaging, confirming the absence of structural ruptures and presence of dividing cells [16].

This protocol partially removes LPS without compromising cell viability, allowing researchers to directly investigate the contribution of outer membrane structure to adhesion forces and cellular mechanics. Studies using this approach have demonstrated that LPS removal significantly reduces adhesion forces and cell-to-cell heterogeneity in E. coli populations [16].

Visualization of SCFS Workflow

This workflow illustrates the comprehensive process from sample preparation to parameter extraction in bacterial SCFS experiments. The visualization highlights how fundamental parameters are derived from specific phases of the force measurement process, particularly during the retraction phase where adhesion events are recorded as force-distance curves.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Bacterial SCFS

| Item | Specification/Example | Function in SCFS |

|---|---|---|

| AFM System | Atomic Force Microscope with fluid cell | Core instrumentation for force measurement |

| Cantilevers | Tipless cantilevers with colloidal probes | Bacterial immobilization and force sensing |

| Immobilization Reagent | Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | Positively charged polymer for cell attachment |

| Bacterial Strains | B. velezensis, P. defensor, E. coli, S. aureus | Model organisms for adhesion studies |

| Surface Materials | Plant roots, bioactive glass, polymer coatings | Substrates for adhesion measurement |

| Chemical Treatment | EDTA (100 mM, pH 8.0) | LPS removal for membrane studies |

| Imaging Validation | Fluorescence microscopy with viability stains | Confirmation of cell viability and position |

| Buffer Systems | Phosphate buffer (0.01 M, pH 7.0-7.4) | Physiological maintenance medium |

| Data Analysis Software | Worm-like chain (WLC) model fitting | Polymer elasticity analysis of force curves |

| AM-001 | AM-001, MF:C24H16FN3OS2, MW:445.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GSK461364 | GSK461364, CAS:929095-18-1, MF:C27H28F3N5O2S, MW:543.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The fundamental parameters of rupture forces, loading rates, and bond strength provide critical insights into the nanoscale interactions between bacteria and surfaces. Through standardized SCFS protocols and careful data interpretation, researchers can quantify these parameters to understand the biophysical mechanisms driving bacterial adhesion. This knowledge enables the rational design of anti-fouling surfaces, improved biomaterials, and novel therapeutic strategies that target the initial stages of bacterial colonization. As SCFS methodologies continue to evolve, their application in pharmaceutical and medical device development promises to yield increasingly sophisticated approaches to managing bacterial adhesion and biofilm-related challenges.

Advantages of SCFS Over Traditional Adhesion Assays

Single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) is an atomic force microscopy (AFM)-based technique that has emerged as a powerful tool for quantitatively measuring the biophysical forces involved in cell adhesion at the single-cell level. Unlike traditional adhesion assays that provide population-averaged data, SCFS enables researchers to probe the nanoscale interactions between an individual cell and a substrate with piconewton sensitivity [25]. This technical capability is particularly valuable in bacterial adhesion research, where phenotypic heterogeneity within clonal populations can significantly influence colonization and infection outcomes [16]. SCFS employs a single bacterial cell attached to a cantilever to directly quantify adhesion forces, cell elasticity, and the dynamics of bond formation and rupture, providing unprecedented insight into the fundamental mechanisms governing microbial attachment to surfaces [16] [26].

The application of SCFS represents a paradigm shift from traditional ensemble measurements, which often mask cell-to-cell variability, toward a more precise understanding of adhesion heterogeneity. This technical guide examines the specific advantages of SCFS over traditional adhesion assays within the context of bacterial adhesion research, detailing methodological approaches, key findings, and experimental considerations for implementing this cutting-edge technology.

Limitations of Traditional Adhesion Assays

Traditional bacterial adhesion assays, while useful for initial screening, suffer from several significant limitations that restrict their utility for mechanistic studies:

Population averaging effects: Conventional methods such as microbiology adhesion assays and centrifugation-based detachment provide data averaged across thousands to millions of cells, effectively masking the substantial cell-to-cell heterogeneity that exists within clonal populations [16]. This averaging obscures the presence of phenotypic subgroups with distinct adhesive properties that may be critical for understanding infection processes.

Limited quantitative resolution: Traditional approaches typically yield semi-quantitative or qualitative data (e.g., colony-forming unit counts, optical density measurements) rather than precise force measurements, making it difficult to correlate adhesion with specific biophysical properties [25] [26].

Inability to probe kinetic parameters: Standard adhesion assays cannot resolve the dynamics of bond formation and rupture or measure the nanomechanical properties of individual cells, which are increasingly recognized as important factors in bacterial pathogenesis and environmental adaptation [16] [25].

Poor temporal resolution: Most conventional methods capture adhesion at a single endpoint rather than monitoring the real-time evolution of adhesive interactions, missing critical information about the progression of attachment strength over time [25].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional Bacterial Adhesion Assays

| Limitation | Impact on Research | Example Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Population Averaging | Masks phenotypic heterogeneity; overlooks rare but important subpopulations | Microtiter plate assays, flow chamber assays |

| Qualitative Output | Provides relative rather than absolute measurements; difficult to compare between studies | Staining and counting, optical density measurements |

| Limited Mechanistic Insight | Cannot distinguish specific from non-specific interactions or measure single-bond kinetics | Centrifugation assays, washing and enumeration |

| Endpoint Measurements | Captures static snapshot rather than dynamic process | Colony-forming unit counts after adhesion |

| Bulk Property Measurement | Averages across cells and surface regions | Radiolabeling, spectrophotometric assays |

Methodological Advantages of SCFS

Quantitative Force Measurement at Single-Cell Resolution

SCFS provides direct quantitative measurement of adhesion forces at the fundamental scale of individual cells, typically with piconewton sensitivity and nanometer spatial resolution [25]. This precision enables researchers to:

- Measure absolute adhesion forces between a single bacterium and specific substrates, ranging from abiotic surfaces to host cells [26].

- Characterize the nanomechanical properties of individual cells, including elasticity and deformation, which influence adhesion mechanics [16].

- Map force distributions across cell surfaces to identify localized adhesion hotspots corresponding to specific surface structures or adhesins [16].

For example, in studies of Escherichia coli, SCFS has revealed how lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated heterogeneity influences adhesion at the single-cell level, with individual cells within a clonal population exhibiting markedly different adhesive phenotypes [16]. Similarly, SCFS analysis of Streptococcus pneumoniae has elucidated the distinct roles of capsule phenotype and surface proteins in adhesion to lung epithelial cells and collagen, demonstrating that adhesion is a multiphasic process with different force profiles at various contact times [26].

Analysis of Cell Heterogeneity

A fundamental advantage of SCFS is its ability to resolve phenotypic heterogeneity within genetically identical bacterial populations, which is inaccessible to traditional ensemble methods [16]. This capability has revealed:

- The existence of stiff and highly adherent subpopulations within clonal cultures that may have enhanced colonization potential [16].

- How outer membrane alterations, such as LPS removal by EDTA treatment, reduce cell-to-cell heterogeneity by homogenizing surface properties [16].

- Structural diversity in the cell envelope that correlates with variable adhesion strengths among individual cells [16].

This single-cell resolution is particularly valuable for identifying rare but functionally important subpopulations that may initiate infections or exhibit enhanced resistance to antimicrobial agents.

Dynamic Adhesion Process Monitoring

SCFS enables real-time monitoring of adhesion dynamics, capturing the temporal evolution of adhesive interactions that traditional endpoint assays cannot detect [25] [26]. This dynamic capability allows researchers to:

- Measure adhesion kinetics at biologically relevant timescales, from milliseconds to hours.

- Investigate the multiphasic nature of bacterial adhesion, where short-term and long-term adhesion mechanisms may differ significantly [26].

- Probe the mechanical adaptation of bacteria during surface attachment, including surface-induced changes in adhesive properties.

Research on Streptococcus pneumoniae using SCFS has demonstrated that adhesion profiles at short contact times (<5 seconds) can differ substantially from those at long contact times (~1 hour), suggesting distinct adhesive mechanisms operate at different stages of the adhesion process [26].

Controlled Microenvironment

The SCFS experimental setup provides precise environmental control that enables systematic investigation of factors influencing bacterial adhesion:

- Systematic variation of contact time and force to elucidate their effects on adhesion strength [26].

- Controlled physicochemical conditions including buffer composition, temperature, and flow dynamics.

- Specific surface functionalization to probe interactions with defined chemical groups or extracellular matrix components [27].

Studies utilizing amine plasma polymer (PP) surfaces have demonstrated how SCFS can detect fine differences in cell-adhesion to surfaces with varying chemical compositions, revealing that increased cell adhesion to amine-functionalized surfaces likely involves non-specific electrostatic interactions rather than solely receptor-mediated adhesion [27].

Comparative Experimental Data

Table 2: Quantitative SCFS Measurements in Bacterial Adhesion Studies

| Bacterial Species | Adhesion Force Range | Experimental Conditions | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) | Variable within population | Colloidal probe AFM; PBS buffer | EDTA treatment reduced adhesion force heterogeneity; eliminated highly adherent subpopulations | [16] |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | PspC-dependent forces | AFM with lung epithelial cells | PspC mutation reduced nonspecific and specific interactions; contributed to medium- and long-range interactions (>3000nm) | [26] |

| LF fibroblasts on amine PPs | Significantly increased vs. control | Single-cell force spectroscopy on functionalized surfaces | Amine plasma polymers dramatically increased adhesion force; difference detected between various amine PPs | [27] |

Table 3: Technical Comparison: SCFS vs. Traditional Adhesion Assays

| Parameter | SCFS | Traditional Adhesion Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Force Resolution | Piconewton (pN) | Not applicable (qualitative) |

| Spatial Resolution | Nanometer (nm) | Micrometer (µm) to millimeter (mm) |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond to hour timescales | Minute to hour timescales (endpoint) |

| Cell-to-Cell Variability | Directly measurable | Masked by population averaging |

| Single-Bond Kinetics | Accessible via rupture force analysis | Not accessible |

| Mechanical Properties | Elasticity, deformation measurable | Not measurable |

| Throughput | Low (typically <100 cells/experiment) | High (thousands to millions of cells) |

| Experimental Complexity | High (requires specialized expertise) | Low to moderate |

Detailed SCFS Methodology

Bacterial Immobilization for SCFS

Proper immobilization of bacterial cells is critical for reliable SCFS measurements. The following protocol has been successfully applied in bacterial adhesion studies:

- Cell preparation: Centrifuge bacterial culture at 2151 × g for 5 minutes at 24°C and wash cell pellets with Milli-Q water [16].

- Surface functionalization: Immobilize bacteria on gelatin-coated glass surfaces to ensure firm attachment during force measurements [16].

- Cell concentration adjustment: Adjust bacterial suspension to approximately 10ⶠCFU/ml before deposition on functionalized surfaces [16].

- Immobilization incubation: Deposit bacterial suspension on prepared surfaces and allow 30 minutes for attachment [16].

This immobilization approach preserves cell viability and maintains natural surface properties while providing sufficient adhesion to withstand measurement forces.

Force Measurement Protocol

Standard SCFS measurements involve the following steps:

- Cantilever functionalization: Depending on experimental goals, attach a single bacterial cell to a tipless cantilever using a bio-compatible adhesive, or use a colloidal probe to assess whole-cell interactions [16].

- Approach phase: Bring the cell-functionalized cantilever into contact with the substrate surface with controlled force (typically 0.5-2 nN) and duration.

- Retraction phase: Withdraw the cantilever from the surface while recording the deflection, which corresponds to adhesion forces as molecular bonds rupture.

- Data collection: Acquire multiple force-distance curves (typically 100-1000) across different locations on the cell surface or across multiple cells.

- Data analysis: Extract adhesion parameters including maximum adhesion force, work of adhesion (area under retraction curve), and rupture event length and frequency.

For studies investigating outer membrane contributions to adhesion, partial LPS removal can be achieved through EDTA treatment (100 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 37°C for 30 minutes with gentle shaking), which substantially alters bacterial cell surface properties and reduces heterogeneity [16].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential SCFS Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SCFS Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscope | Core measurement instrument | With fluid cell for measurements in physiological buffers |

| Tipless Cantilevers | Bacterial cell attachment | Functionalized with bio-compatible adhesive |

| Colloidal Probes | Whole-cell force measurements | Spherical particles attached to cantilevers for assessing overall cell adhesion |

| Gelatin-Coated Surfaces | Cell immobilization | Provides firm attachment while preserving viability [16] |

| EDTA Solution | LPS removal/modification | 100 mM, pH 8.0 for controlled outer membrane alteration [16] |

| Amine Plasma Polymers | Surface functionalization | Surfaces with different amine group densities for adhesion mechanism studies [27] |

| Phosphate Buffer | Physiological measurement conditions | 0.01 M, pH 7.0 for maintaining bacterial viability during measurements [16] |

| Aprotinin | Antilysin Research Grade|Antilysin (Aprotinin) | Research-grade Antilysin, a substance that counteracts lysins. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| TC14012 | TC14012, MF:C90H140N34O19S2, MW:2066.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Diagram 1: SCFS vs Traditional Assay Workflows

Diagram 2: Bacterial Adhesion Mechanisms Accessible via SCFS

Single-cell force spectroscopy represents a transformative methodology in bacterial adhesion research, offering significant advantages over traditional adhesion assays through its capacity for quantitative force measurement, resolution of cellular heterogeneity, dynamic process monitoring, and precise environmental control. While the technique requires specialized instrumentation and expertise, its ability to reveal fundamental biophysical mechanisms at the single-cell level makes it indispensable for advanced studies of bacterial pathogenesis, surface colonization, and antimicrobial development.

The integration of SCFS into broader research programs on bacterial adhesion provides a powerful approach to connect molecular-scale interactions with population-level behaviors, ultimately enabling more effective strategies to combat bacterial infections and biofilm-associated diseases. As technical developments continue to improve throughput and accessibility, SCFS is poised to become an increasingly central tool in the microbiologist's arsenal.

Practical Implementation: From Bacterial Probe Fabrication to Diverse Research Applications

Step-by-Step Protocol for Single Bacterial Probe Fabrication

In the field of bacterial biophysics, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has evolved into a standard device, yet its capability as a sophisticated quantitative force sensor is often underutilized [28]. The technique of single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) transforms the AFM into a unique tool for quantitative adhesion research in bacteriology by using "bacterial probes"—AFM cantilevers that have a single bacterium or a cluster of bacteria attached as the contact-forming object [28]. This in-depth technical guide provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for fabricating these bacterial probes, a critical methodology for investigating the biophysical interactions at the interface of microbial cells and surfaces.

The ability to measure adhesion forces at the single-cell level has profound implications for understanding bacterial pathogenesis, environmental adaptation, and responses to antimicrobials [16] [26]. This protocol is framed within the broader context of a thesis on single-cell force spectroscopy, emphasizing how this technique enables researchers to move beyond population-averaged data and uncover the significant phenotypic heterogeneity that exists even within clonal bacterial populations [16].

Theoretical Foundation of Bacterial Probe Spectroscopy

The Role of SCFS in Bacterial Adhesion Research

Bacterial adhesion is a critical step in pathogenesis, biofilm formation, and environmental survival. Traditional microbiology adhesion assays provide qualitative assessment of adhesion but lack the biophysical detail offered by SCFS [26]. SCFS allows for the accurate measurement of the biophysical details of adhesion, including the determination of adhesion forces, cell elasticity, and the dynamics of the adhesion process [16] [26].

Recent research has revealed that bacterial populations exhibit remarkable phenotypic heterogeneity, with subgroups of cells displaying different biophysical properties such as adhesion forces and cellular stiffness [16]. This diversity provides a selective advantage under environmental perturbation and increases population-level fitness [16]. SCFS is particularly valuable for detecting and quantifying this cell-to-cell variability, which is often masked in conventional averaged measurements [16].

Key Biophysical Properties Measured with Bacterial Probes

The fabrication and use of bacterial probes enable the investigation of several fundamental biophysical properties:

- Adhesion Forces: The attractive forces between the bacterial cell and a substrate, which can be specific (e.g., receptor-ligand interactions) or non-specific (e.g., electrostatic, van der Waals) [16].

- Cell Elasticity: A measure of cell deformation under mechanical loading, which provides information about the mechanical integrity of the cell envelope [16].

- Adhesion Dynamics: The evolution of adhesive interactions over time, which may represent a multiphasic process where adhesion profiles at short contact times (<5 seconds) can differ significantly from those at long contact times (~1 hour) [26].

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental workflow for single-cell force spectroscopy using fabricated bacterial probes:

Detailed Fabrication Protocol

Materials and Equipment

The following table details the essential materials required for the successful fabrication of single bacterial probes:

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Bacterial Probe Fabrication

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Cantilevers | Serves as the base for bacterial attachment; the force sensor | Typically tipless, with specific spring constants appropriate for biological samples [28] |

| Bacterial Culture | Provides the microbial cells for probe fabrication | Strain-dependent on research question; E. coli ATCC 25922 used in referenced study [16] |

| UV/Ozone Cleaner or Plasma Cleaner | Cleans and sterilizes cantilevers; enhances surface hydrophilicity | Creates a clean, reactive surface for subsequent chemical modification [28] |

| Polydopamine Coating Solution | Creates a versatile, bio-adhesive layer on the cantilever | Prepared by dissolving dopamine hydrochloride in Tris buffer (pH 8.5) [28] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Washing and suspension buffer for biological samples | 0.01 M, pH 7.4, isotonic to maintain bacterial viability [16] |

| Gelatin-Coated Glass Surfaces | For immobilizing bacteria during selection and verification | Provides a non-invasive, non-toxic substrate for temporary immobilization [16] |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Optional: For modifying outer membrane structure | 100 mM, pH 8.0; used to study LPS-mediated effects on adhesion [16] |

Step-by-Step Fabrication Procedure

The fabrication of reliable single bacterial probes requires meticulous attention to detail at each stage. The following workflow outlines the complete process from preparation to quality control:

Step 1: Cantilever Preparation

- Begin with tipless AFM cantilevers appropriate for force spectroscopy.

- Clean the cantilevers thoroughly using UV/ozone treatment or plasma cleaning for 10-15 minutes. This step removes organic contaminants and creates a hydrophilic surface essential for uniform coating application [28].

Step 2: Bio-adhesive Coating Application

- Prepare a fresh polydopamine coating solution by dissolving dopamine hydrochloride (2 mg/mL) in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5).