Stochastic vs. Triggered: Decoding the Dual Mechanisms of Bacterial Persister Cell Formation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the two primary paradigms in bacterial persister cell formation: stochastic, internal fluctuations and triggered, external stress-response pathways.

Stochastic vs. Triggered: Decoding the Dual Mechanisms of Bacterial Persister Cell Formation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the two primary paradigms in bacterial persister cell formation: stochastic, internal fluctuations and triggered, external stress-response pathways. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational concepts, current methodological approaches for studying these dormant cells, the significant challenges in eradicating them, and a comparative evaluation of the mechanisms. By integrating the latest research on (p)ppGpp signaling, toxin-antitoxin modules, and metabolic dormancy, this review aims to bridge mechanistic understanding with the development of novel therapeutic strategies to combat chronic and relapsing infections.

Defining the Dormant State: Core Principles of Stochastic and Triggered Persistence

Historical Context and Definition

Bacterial persisters are a subpopulation of genetically drug-susceptible, quiescent bacteria that survive exposure to high concentrations of antibiotics and other environmental stresses, only to resume growth once the stress is removed [1] [2]. The phenomenon was first identified in 1942 by Gladys Hobby, who observed that penicillin killed approximately 99% of bacteria, leaving 1% surviving [1]. In 1944, Joseph Bigger named these surviving cells "persisters" and suggested pulsed antibiotic therapy as a potential treatment strategy [1].

The critical distinction between persisters and other survival mechanisms lies in their non-heritable, phenotypic nature. The table below clarifies the key differences between bacterial persistence, antibiotic resistance, and tolerance.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Bacterial Survival Strategies

| Feature | Persister Cells | Antibiotic-Resistant Cells | Tolerant Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Basis | Non-heritable, phenotypic variant | Heritable (mutations or acquired genes) | Can be non-heritable or genotypic |

| Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | Unchanged | Increased | Unchanged |

| Mechanism | Dormancy (non-growing or slow-growing) | Prevents drug from binding to target | Population-wide slowing of death rate |

| Reversibility | Reversible upon antibiotic removal | Not reversible | Reversible |

| Population Heterogeneity | Small subpopulation | Entire population | Can be population-wide or a subpopulation |

Mechanisms of Persister Formation

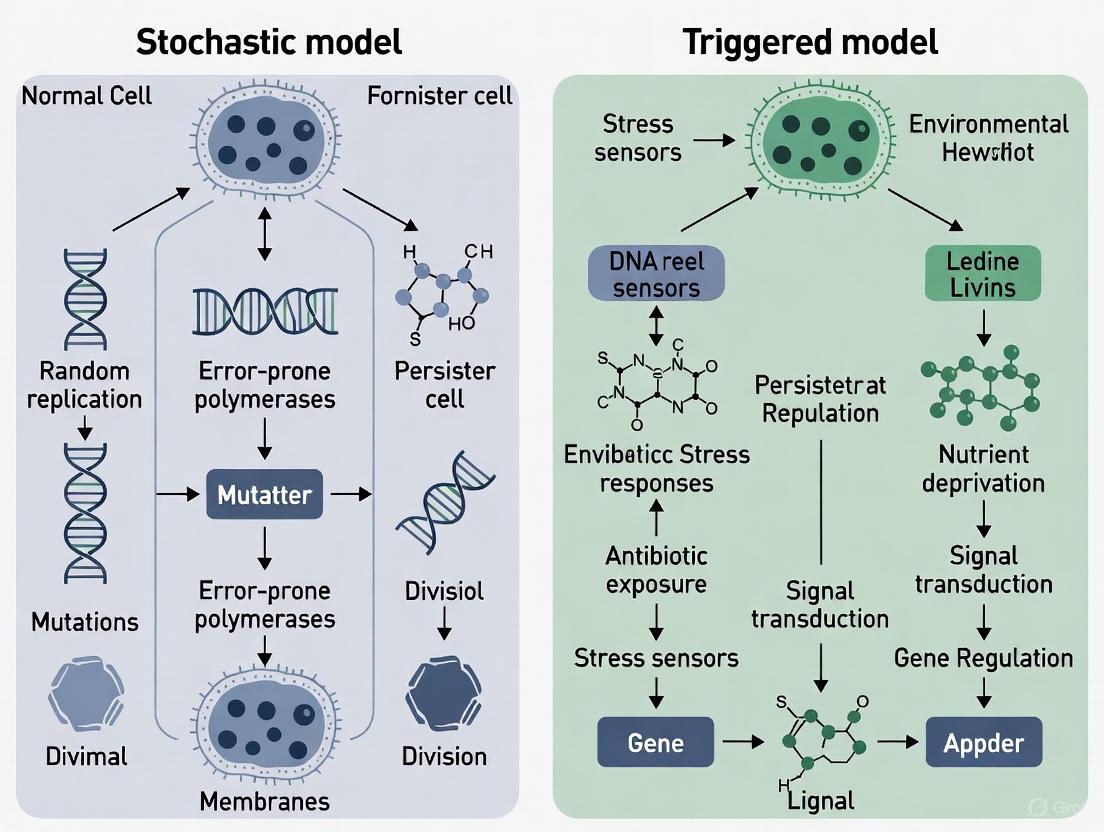

The formation of persister cells is a complex process governed by multiple mechanisms, which can be broadly categorized into stochastic (random) and triggered (induced) pathways.

Stochastic Formation

Stochastic formation implies that persister formation occurs randomly within a bacterial population, even in the absence of external stress. This is thought to be due to natural fluctuations in the expression of key regulatory genes and proteins [3]. Models suggest that low ATP levels can induce protein aggregation, favoring the stochastic formation of non- or slow-growing persister cells [3].

Triggered Formation

Triggered formation occurs in response to specific environmental stresses. Key inducers include:

- Antibiotic exposure: The primary trigger studied in clinical contexts [1].

- Host immune factors: Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) produced by macrophages during infection are major inducers of metabolic dormancy and antibiotic tolerance in intracellular pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis [4].

- Nutrient starvation and acidic pH: Common stressors encountered during infection [1].

- DNA damage: Can activate the SOS stress response, upregulating DNA repair functions and facilitating persister survival [2].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and environmental triggers involved in persister cell formation.

Detection and Isolation Methodologies

Accurately detecting and isolating persister cells is crucial for research. The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for generating and quantifying persisters in vitro.

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocol for Persister Isolation and Time-Kill Assay

| Step | Protocol Detail | Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Culture Preparation | Grow bacterial culture to mid-log or stationary phase. | To obtain a population with a baseline level of persisters. | Persister frequency is typically higher in stationary phase [2]. |

| 2. Antibiotic Challenge | Expose culture to a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., 100x MIC) for a defined period (e.g., 3-5 hours). | To kill the majority of growing, susceptible cells. | Use concentrations significantly above MIC to ensure complete killing of non-persisters. |

| 3. Drug Removal | Wash cells via centrifugation and resuspension in fresh, antibiotic-free medium. | To remove the antibiotic and allow for resuscitation. | Incomplete removal can inhibit subsequent outgrowth. |

| 4. Viability Quantification | Serially dilute and spot-plate on antibiotic-free agar plates. Count Colony Forming Units (CFUs). | To quantify the number of surviving persister cells. | Survivors are defined as persisters if they retain genetic susceptibility upon regrowth [1]. |

For studying intracellular persisters, more complex models are required. A 2025 study used a high-throughput screen with a bioluminescent MRSA strain (JE2-lux) to probe the metabolic activity of bacteria inside macrophages, identifying host-directed compounds that could sensitize intracellular persisters to antibiotics [4].

Clinical Significance and Therapeutic Strategies

Persister cells are a major culprit in the recalcitrance of chronic and biofilm-associated infections. They are clinically significant because they underlie treatment failure, infection relapse, and may serve as a reservoir for the development of full-blown antibiotic resistance [1] [2].

Table 3: Anti-Persister Therapeutic Strategies and Compounds

| Therapeutic Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Example Compounds/Agents | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Killing | Targets growth-independent structures like cell membranes or causes uncontrolled protein degradation. | XF-73, SA-558, Pyrazinamide (PZA), ADEP4 | Preclinical; PZA is in clinical use for TB [5]. |

| Preventing Formation | Inhibits pathways leading to dormancy, such as alarmone synthesis or quorum sensing. | CSE inhibitors, H2S scavengers, Quorum Sensing inhibitors (e.g., brominated furanones) | Mostly preclinical research [5]. |

| Resuscitation & Sensitization | Awakens persisters, making them susceptible to conventional antibiotics. | Host-directed adjuvant KL1, Membrane permeabilizers (e.g., SPR741) | KL1 identified in 2025 high-throughput screen [4] [5]. |

| Rational Drug Discovery | Uses tailored chemoinformatic models to find compounds with ideal properties for penetrating persisters. | Eravacycline, Minocycline derivatives | Proof-of-concept studies identifying new leads [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Bacterial Persisters

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Persistence (hip) Mutant Strains | Models with genetically elevated persister formation for consistent study. | E. coli HM22 (hipA7 allele) used in screening anti-persister compounds [6]. |

| Bioluminescent Reporter Strains | Probes real-time metabolic activity of bacteria, especially inside host cells. | MRSA JE2-lux used to screen for metabolic potentiators in macrophages [4]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Strains | Visualizes and isolates dormant subpopulations via microscopy or flow cytometry. | Inducible GFP reporters used to track S. aureus survival in mouse kidney cells [4]. |

| Membrane-Active Compounds | Increases permeability of persister cell envelopes to facilitate antibiotic uptake. | Polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN), synthetic retinoids used in combination therapies [5]. |

| XMD8-87 | XMD8-87, MF:C24H27N7O2, MW:445.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LY 3000328 | LY 3000328, CAS:1373215-15-6, MF:C25H29FN4O5, MW:484.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Bacterial persisters, born from a delicate interplay between stochastic intracellular events and environmentally triggered responses, represent a profound challenge in managing chronic infections. Their ability to survive antibiotic assault without genetic resistance directly contributes to relapsing and biofilm-associated diseases. Understanding the dual nature of their formation is fundamental to devising effective countermeasures. While significant progress has been made in detecting persisters and identifying potential therapeutic targets, the translation of anti-persister strategies into clinical practice remains a critical frontier. Future research leveraging high-throughput screening, host-directed therapies, and rational drug design holds the promise of finally overcoming the resilience of these dormant cells.

Stochastic phenotype switching describes the ability of an isogenic cell population to generate multiple distinct phenotypes in the absence of genetic differences. This phenomenon represents a fundamental bet-hedging strategy that enhances population survival in unpredictably fluctuating environments [7] [8]. In essence, by randomly distributing different phenotypic states across a population, organisms ensure that at least a subpopulation will survive a sudden environmental stress, such as antibiotic exposure, that would eliminate a uniformly specialized population [9].

This review examines the mechanisms and implications of stochastic switching models, with particular focus on their role in generating non-genetic heterogeneity in bacterial persister cells and therapy-tolerant cancer cells. We frame this discussion within the ongoing scientific exploration of stochastic versus triggered persister cell formation mechanisms. While cells can certainly switch phenotypes in direct response to environmental cues (triggered switching), evidence increasingly supports the existence of intrinsically stochastic switching that occurs prior to environmental challenges, providing a survival advantage when changes are sudden and lethal [7] [8] [10]. This distinction has profound implications for understanding treatment failure in infectious diseases and cancer, and for developing more effective therapeutic strategies.

Theoretical Foundations: From Evolutionary Concepts to Mathematical Frameworks

Bet-Hedging as an Evolutionary Strategy

Bet-hedging represents an evolutionary optimal strategy for populations facing unpredictable environmental fluctuations. The concept derives from economic theory, where it describes diversifying investments to reduce risk, but in biological systems, it manifests as phenotypic heterogeneity within clonal populations [8] [9]. This heterogeneity ensures that even if the majority phenotype perishes under sudden stress, a minor subpopulation possessing a different phenotype might survive and eventually repopulate.

Theoretical models indicate that the effectiveness of bet-hedging depends critically on the frequency and predictability of environmental changes [8]. When environmental fluctuations occur rapidly, a generalist phenotype adapted to average conditions typically prevails. Conversely, when environmental changes happen on an intermediate timescale, a bet-hedging strategy with bimorphic phenotype distribution becomes optimal. For very slow environmental fluctuations, specialized monomorphic phenotypes adapted to each specific environment tend to dominate [8].

Mathematical Modeling of Stochastic Switching

The dynamics of stochastic phenotype switching can be captured mathematically through several modeling approaches:

Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs) provide a powerful framework for describing systems evolving under inherent randomness. The canonical SDE form is:

[ dXt = f(Xt,t)dt + G(Xt,t)dWt ]

where (Xt) represents the state vector, (f(Xt,t)) defines the deterministic drift, (G(Xt,t)) is the diffusion coefficient matrix, and (Wt) is a Wiener process representing stochastic noise [11]. In biological contexts, SDEs can model how protein concentrations or other intracellular components fluctuate stochastically, potentially driving phenotype transitions.

Markov chain models offer another approach, treating phenotype switching as stochastic transitions between discrete states. These models are particularly useful for describing the random emergence of bacterial persisters or drug-tolerant cancer cells [12]. Recent advances have integrated non-genetic inheritance and cellular memory into these models, recognizing that daughter cells often inherit parental phenotypic states with probabilities that decay over time [12].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Frameworks for Stochastic Switching

| Model Type | Key Features | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Differential Equations | Continuous-time, noise-driven dynamics | Protein concentration fluctuations, gene expression noise |

| Markov Chain Models | Discrete states with transition probabilities | Bacterial persistence, cancer cell phenotype switching |

| Structured Population Models | PDEs tracking population distributions | Age-structured phenotype inheritance, tumor heterogeneity |

| Adaptive Dynamics | Evolutionary optimization of switching rates | Bet-hedging strategy evolution in fluctuating environments |

Experimental Evidence Across Biological Systems

Bacterial Persistence: A Paradigm of Stochastic Phenotype Switching

Bacterial persisters represent a non-growing or slow-growing subpopulation that survives antibiotic treatment despite genetic susceptibility to these drugs [1]. These cells were first identified by Gladys Hobby in 1942 and named by Joseph Bigger in 1944, who observed that penicillin killed most staphylococci but left a small subset surviving [1].

Seminal work by Balaban et al. established that E. coli populations contain multiple persister types [9]. Type I persisters emerge during stationary phase and exhibit complete growth arrest, while Type II persisters grow slowly but steadily during normal growth conditions and maintain this slow growth rate under antibiotic stress [9]. This phenotypic heterogeneity occurs without genetic differences, strongly supporting a stochastic switching mechanism.

Recent research has identified energy management as a key factor in persister formation. Studies demonstrate that bacterial cells with low ATP levels show increased survival under antibiotic treatment [13]. Single-cell analysis using an ATP reporter (iATPSnFr1.0) revealed that a subpopulation with reduced ATP before antibiotic exposure exhibits enhanced tolerance, suggesting that stochastic fluctuations in energy-generating enzymes drive persistence formation [13].

Table 2: Bacterial Persister Types and Characteristics

| Persister Type | Formation Trigger | Growth State | Metabolic Characteristics | Molecular Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Stationary phase transition | Non-growing | Metabolic dormancy | toxin-antitoxin modules (HipA), stringent response |

| Type II | Stochastic during growth | Slow-growing | Reduced ATP, impaired Krebs cycle | Stochastic fluctuations in energy-generating enzymes |

| Type III (VBNC) | Severe stress | Dormant | Very low metabolic activity | Protein degradation, RNA stability |

Stochastic Switching in Cancer: Drug-Tolerant Persisters

Cancer biology has revealed striking parallels to bacterial persistence in the form of drug-tolerant persisters (DTPs). These cells exhibit reversible resistance to targeted therapies and chemotherapeutic agents without possessing genetic resistance mutations [7].

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), treatment with EGFR inhibitors at concentrations 100-fold higher than the IC₅₀ value led to the isolation of DTPs that regained drug sensitivity when propagated in drug-free media [7]. Similarly, melanoma tumors resistant to BRAF inhibition upregulated EGFR in a reversible manner, with drug holidays restoring treatment sensitivity [7]. Single-cell transcriptomics has revealed that these transitions often involve shifts from drug-naïve "melanocytic" states to drug-resistant "mesenchymal-like" states driven by underlying signaling network dynamics rather than selection of pre-existing genetic mutants [7].

The cancer stem cell (CSC) model further illustrates stochastic phenotype switching, with dynamic interconversion between CSCs and non-CSCs maintaining phenotypic equilibrium within tumors [7]. This plasticity enables tumors to withstand therapeutic assaults and represents a significant clinical challenge for achieving durable remissions.

Methodologies: Experimental Protocols and Analytical Approaches

Isolation and Characterization of Bacterial Persisters

Protocol 1: Persister Isolation via Antibiotic Killing Curves

- Culture Preparation: Grow bacterial culture to mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5) in appropriate liquid medium.

- Antibiotic Exposure: Add ciprofloxacin (or other bactericidal antibiotic) at 10-100× MIC concentration.

- Incubation and Sampling: Incubate culture at 37°C with shaking. Remove samples at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours).

- Viability Assessment: Serially dilute samples and plate on drug-free agar plates. Count colony-forming units (CFUs) after 24-48 hours incubation.

- Data Analysis: Plot log CFU/mL versus time to generate biphasic killing curves. The initial steep decline represents killing of normal cells, while the subsequent plateau indicates persister survival [1].

Protocol 2: Single-Cell ATP Analysis Using Microfluidics

- Strain Engineering: Chromosomally integrate ratiometric ATP reporter iATPSnFr1.0 under constitutive promoter.

- Microfluidics Setup: Load stationary-phase culture into mother machine microfluidic device.

- Media Flow: Flow fresh medium for 1 hour to revive cells, then switch to medium containing ampicillin.

- Time-Lapse Microscopy: Image cells every 15-30 minutes for 5+ hours using dual excitation (405 nm and 488 nm).

- ATP Quantification: Calculate 488â‚‘â‚“/405â‚‘â‚“ emission ratio for each cell. Correlate pre-treatment ATP levels with survival outcomes [13].

Monitoring Phenotype Switching in Cancer Cells

Protocol 3: Drug-Tolerant Persister Isolation in Cancer Models

- Cell Culture: Maintain NSCLC cell lines (e.g., PC9) expressing fluorescent viability reporters.

- Drug Treatment: Expose to high concentrations of EGFR inhibitors (e.g., erlotinib at 1-10 µM) for 72 hours.

- Persister Enrichment: Wash away dead cells and continue culture in drug-free medium for recovery.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Sort viable cells based on fluorescence markers. Confirm DTP phenotype by re-challenging with original drug.

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Profile transcriptomes of parental cells, DTPs, and recovered populations to identify transitional states [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Studying Stochastic Switching

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Key Features | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| iATPSnFr1.0 Reporter | Ratiometric ATP sensing | Dual excitation (405/488 nm), self-normalizing | Single-cell ATP monitoring in microfluidics [13] |

| Mother Machine Microfluidics | Single-cell culture and imaging | High-temporal resolution, controlled environment | Long-term tracking of phenotype switching [13] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Population separation based on protein levels | High-throughput, multi-parameter analysis | Isolation of dim/bright subpopulations [13] |

| Toxin-Antitoxin Mutants (hipA7) | Persistence gene manipulation | Gain-of-function mutations | Study of Type I persister mechanisms [9] |

| Krebs Cycle Enzyme Reporters (GltA, Icd, SucA) | Monitoring metabolic heterogeneity | mVenus translational fusions | Correlation of metabolic state with persistence [13] |

| MDI-2268 | MDI-2268|PAI-1 Inhibitor|Research Compound | MDI-2268 is a potent PAI-1 inhibitor with antithrombotic properties. This product is for Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. | Bench Chemicals |

| BET bromodomain inhibitor | BET Bromodomain Inhibitor for Epigenetic Research | Explore high-purity BET bromodomain inhibitors for cancer, inflammation, and epigenetic research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

Signaling Networks and Molecular Mechanisms

The molecular basis of stochastic phenotype switching involves complex regulatory networks that exhibit bistability and stochastic noise. In bacteria, toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules have been strongly implicated in persistence formation. The HipA toxin, part of the HipBA TA system, phosphorylates glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, inhibiting translation and inducing dormancy [1]. Stochastic fluctuations in HipA levels can trigger transition to the persistent state.

Metabolic regulation represents another key mechanism. Studies demonstrate that isocitrate dehydrogenase (Icd) mutants in E. coli produce more persisters and have lower ATP levels, directly linking Krebs cycle activity to persistence formation [13]. Cells with diminished expression of Krebs cycle enzymes show enriched survival under antibiotic challenge.

In cancer cells, phenotype switching between drug-sensitive and drug-tolerant states often involves chromatin remodeling and epigenetic regulation. For example, in NSCLC, chromatin modifications that alter gene expression patterns can create transiently resistant subpopulations without genetic mutations [7]. These epigenetic states can be stable through cell divisions but remain reversible.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Understanding stochastic switching mechanisms has profound implications for combating chronic infections and therapy-resistant cancers. Traditional antibiotic and anticancer therapies often fail because they primarily target rapidly dividing cells, leaving persister populations intact and enabling disease recurrence [7] [1].

Novel therapeutic approaches aim to target persister cells specifically or prevent their formation. For bacterial infections, this includes developing compounds that disrupt TA modules, metabolic pathways essential for persistence, or membrane integrity of dormant cells [1]. In cancer, strategies focus on combination therapies that simultaneously target both proliferating cells and drug-tolerant persisters, or epigenetic modulators that lock cells in drug-sensitive states [7] [12].

Evolutionarily-informed treatment schedules represent another promising approach. Mathematical modeling suggests that adaptive therapy—modulating drug pressure based on tumor burden—can suppress the expansion of drug-tolerant subpopulations by maintaining competitive suppression from drug-sensitive cells [12]. This approach has shown promise in both experimental cancer models and clinical trials.

Future research directions include:

- Single-cell multi-omics to comprehensively characterize the molecular features of persister cells across different biological systems.

- High-throughput screening for novel anti-persister compounds with specific activity against dormant cell populations.

- Clinical translation of evolutionary principles into treatment schedules that manage rather than eliminate persistent cell populations.

- Quantitative modeling integrating stochastic switching dynamics with pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters to optimize treatment timing and dosing.

The continued investigation of stochastic switching models and their role in bet-hedging strategies remains essential for addressing some of the most challenging problems in modern medicine, particularly the crisis of therapeutic resistance in infectious diseases and cancer.

Bacterial persistence represents a significant challenge in clinical settings, underlying chronic infections, treatment failures, and relapsing diseases. Unlike antibiotic resistance, which involves genetic mutations that permit growth in the presence of drugs, persistence describes a phenotypically dormant state in which susceptible bacterial cells survive antibiotic exposure without genetic alteration [1] [5]. These dormant persister cells can resuscitate after antibiotic removal, leading to recurrent infections. The formation of persister cells occurs through two primary mechanisms: stochastic persistence, which arises spontaneously in a subset of cells through non-deterministic processes, and triggered persistence, induced by environmental stressors [14] [15]. This whitepaper examines the principal environmental triggers of bacterial persistence—antibiotic stress, nutrient starvation, and host immune factors—within the broader context of stochastic versus triggered formation mechanisms. Understanding these pathways is critical for developing novel therapeutic strategies against persistent infections.

Distinguishing Bacterial Persistence: Definitions and Key Concepts

Table 1: Key Definitions and Distinctions in Bacterial Survival Strategies

| Term | Definition | Key Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Persistence | A phenomenon where a susceptible bacterial subpopulation survives antibiotic exposure by entering a transient, dormant state. | Reversible, non-genetic, phenotypic heterogeneity within clonal population; biphasic killing curve. | [14] [1] |

| Antibiotic Resistance | The inherited ability of bacteria to grow at high antibiotic concentrations, typically measured by elevated MIC. | Genetic basis (mutations or gene acquisition); stable inheritance; allows growth under antibiotic pressure. | [16] |

| Antibiotic Tolerance | The ability of the entire bacterial population to survive antibiotic treatment for extended periods, often due to slow growth. | Population-wide survival; delayed killing; often induced by environmental conditions like starvation. | [1] [17] |

| Stochastic Persistence | Persister formation that occurs spontaneously at low frequency in homogeneous, unstressed cultures. | Probabilistic single-cell switching; pre-existing heterogeneity; not induced by external triggers. | [14] [15] |

| Triggered Persistence | Persister formation induced by environmental stressors such as antibiotics, nutrient limitation, or immune factors. | Response to external signals; often higher frequency than stochastic persistence; potentially preventable. | [14] [4] |

The distinction between persistence, resistance, and tolerance has important clinical implications. While resistance mechanisms are readily identifiable through standard microbiological assays like minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing, persistence is difficult to measure and often missed in clinical diagnostics, potentially leading to unexplained treatment failures [16]. Persister cells exhibit metabolic heterogeneity, ranging from complete growth arrest to slow growth, and exist along a continuum from "shallow" to "deep" persistence states [1]. The relative contribution of stochastic versus triggered mechanisms to persister formation varies depending on bacterial species, growth conditions, and the specific environmental stressors encountered.

Molecular Mechanisms of Persister Formation

Core Signaling Pathways and Networks

The molecular machinery governing persister formation involves interconnected networks that sense environmental stress and modulate bacterial metabolism toward dormancy. Key systems include toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules, stringent response pathways, and secondary messenger systems.

Figure 1: Molecular Pathways of Triggered Persister Formation. Environmental triggers activate cellular sensors that initiate signaling cascades leading to growth arrest and antibiotic tolerance. Key pathways include HipA-mediated stringent response, (p)ppGpp-polyphosphate signaling, and toxin-antitoxin system activation. PPX = exopolyphosphatase; ROS/RNS = reactive oxygen/nitrogen species.

The stringent response serves as a master regulator connecting various environmental stresses to persistence. Through the signaling nucleotides (p)ppGpp, bacteria can modulate cellular physiology in response to nutrient limitation and other stressors [18]. The HipA toxin exemplifies this integration: when activated by antibiotic stress, HipA phosphorylates glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (GltX), leading to accumulation of uncharged tRNAGlu that activates RelA and (p)ppGpp synthesis [18]. Elevated (p)ppGpp inhibits exopolyphosphatase (PPX), causing polyphosphate accumulation that activates Lon protease to degrade antitoxins, thereby freeing TA-encoded toxins such as mRNA-degrading nucleases that inhibit translation and induce dormancy [18].

Stochastic Switching Mechanisms

Stochastic persister formation occurs through probabilistic switching in individual cells without requiring external triggers. Single-cell studies of E. coli have revealed that in exponentially growing populations, most persisters against ampicillin and ciprofloxacin were actually growing before antibiotic treatment, displaying heterogeneous survival dynamics including continuous growth with L-form-like morphologies, responsive growth arrest, or post-exposure filamentation [15]. This demonstrates that growth arrest is not mandatory for persistence against all antibiotics. The stochastic variation in (p)ppGpp levels represents a key mechanism driving spontaneous persistence, as fluctuations in this global regulator can trigger TA system activation through the polyphosphate-Lon protease pathway [18].

Major Environmental Triggers of Persistence

Antibiotic Stress

Antibiotics themselves can induce persistence by activating stress response pathways. For example, sublethal antibiotic exposure triggers the SOS response and TA system activation through pathways involving (p)ppGpp [14] [18]. In Acinetobacter baumannii, exposure to imipenem or ciprofloxacin induces persistence through specific TA systems including AbkA/AbkB and HigBA [14]. Antibiotic-induced persistence demonstrates a paradoxical feedback loop wherein the therapeutic agent intended to eliminate bacteria instead promotes the formation of treatment-refractory subpopulations.

Nutrient Starvation

Nutrient limitation represents a potent trigger for persistence by activating the stringent response and shifting metabolism toward dormancy. However, the protective effect of nutrient deprivation exhibits important distinctions between phenotypic tolerance and genuine persistence. Stationary-phase cultures and nutrient-starved E. coli display complete survival when treated with antibiotics including ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, kanamycin, and mitomycin C—behavior characteristic of tolerance rather than persistence [17]. This protection is readily reversible; adding nutrients to stationary-phase cultures before ciprofloxacin treatment restores antibiotic killing to 0.001% survival [17]. In contrast, high-persistence mutants (e.g., hipA7 and metG2) maintain high survival (∼10%) even after nutrient restoration, indicating a genetically programmed persistent state distinct from phenotypic tolerance [17].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Nutrient Deprivation Effects on Bacterial Survival

| Condition | Survival After Antibiotic Treatment | Response to Nutrient Restoration | Classification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential Phase (nutrient replete) | 0.0001% ( extensive killing) | Not applicable | Sensitive population | [17] |

| Stationary Phase (nutrient depleted) | 10-100% ( complete survival) | Extensive killing (0.001% survival) | Phenotypic tolerance | [17] |

| hipA7 mutant (stationary phase) | 10% ( high survival) | Maintains high survival (∼10%) | Genetic persistence | [17] |

| Starvation in saline | High survival | Killing upon nutrient addition | Phenotypic tolerance | [17] |

Host Immune Factors

The host intracellular environment represents a significant niche for antibiotic-tolerant persisters. Professional phagocytes like macrophages provide physical protection and induce metabolic dormancy through multiple mechanisms. Host-produced reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) have been strongly implicated in inducing antibiotic tolerance in pathogens including S. aureus, M. tuberculosis, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and Salmonella enterica Typhimurium [4]. Additional intracellular stressors such as phagosome acidification and nutrient deprivation further contribute to tolerance induction [4]. This host-induced tolerance has dominant effects; clinical S. aureus isolates showing 200-fold differences in persister frequency in vitro produced similarly high tolerance levels (26-51% survival) after macrophage internalization [4].

A novel screening approach identified KL1, a host-directed compound that increases intracellular bacterial metabolic activity and sensitizes persisters to antibiotics without causing cytotoxicity or bacterial outgrowth [4]. KL1 modulates host immune response genes and suppresses ROS production in macrophages, alleviating a key inducer of antibiotic tolerance [4]. This approach demonstrates that targeting host pathways controlling bacterial dormancy represents a promising strategy against persistent infections.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Persister Detection and Quantification Methods

Table 3: Methodologies for Studying Persister Cells

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Level Assays | Time-kill curves, Replica Plating Tolerance Isolation System (REPTIS), Tolerance Disk (TD) assay | Quantification of persister frequencies; antibiotic susceptibility profiling | Population averages; misses single-cell heterogeneity [16] [1] |

| Single-Cell Analysis | Microfluidics with membrane-covered microchamber arrays (MCMA), growth reporters, ScanLag | Tracking individual cell histories before/during/after antibiotic exposure; heterogeneity analysis | Reveals rare events; technically challenging; low-throughput [14] [15] |

| Genetic/ Molecular Screens | Mutant libraries, -omics techniques (transcriptomics, proteomics), mathematical modeling | Identifying genes and pathways involved in persister formation | Comprehensive mechanism identification; complex data interpretation [14] [1] |

| Metabolic Activity Probes | Lux-based bioluminescent reporters, ATP assays, ROS detection | Monitoring bacterial metabolic state and energy status | Functional readout of dormancy; may not correlate directly with viability [4] [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Microfluidic Single-Cell Analysis of Persister Dynamics [15]

- Device Fabrication: Create a microfluidic device with a membrane-covered microchamber array (MCMA) featuring 0.8-µm deep microchambers etched on a glass coverslip.

- Cell Loading: Enclose E. coli cells in microchambers by covering with a cellulose semipermeable membrane via biotin-streptavidin bonding.

- Medium Control: Establish controlled medium flow above the membrane to flexibly manipulate environmental conditions around cells.

- Antibiotic Treatment: Introduce antibiotics at lethal concentrations (e.g., 200 µg/mL ampicillin [12.5×MIC] or 1 µg/mL ciprofloxacin [32×MIC]) through the medium flow.

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Monitor individual cell growth, division, and survival dynamics before, during, and after antibiotic exposure using phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy.

- Data Analysis: Track cell lineages and classify survival behaviors based on pre-exposure growth status and post-exposure responses.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening for Intracellular Persister Sensitizers [4]

- Reporter Strain Preparation: Utilize bioluminescent MRSA strain JE2-lux, where lux activity correlates with metabolic activity (ATP levels, NAD(P)H, FMNH2).

- Macrophage Infection: Infect bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) with JE2-lux and eliminate extracellular bacteria with gentamicin-containing media.

- Compound Screening: Dispense infected macrophages into 384-well plates containing test compounds from a drug-like library (>4,700 compounds).

- Dual-Parameter Detection: Measure bacterial bioluminescence (metabolic activity) and host viability after 4-hour incubation.

- Hit Validation: Identify compounds that increase bioluminescence >1.5-fold without cytotoxicity, then test their ability to enhance antibiotic killing of intracellular persisters.

- Mechanistic Studies: Employ transcriptomic analysis and ROS detection assays to elucidate compound mechanisms of action.

Protocol 3: Distinguishing Persistence from Phenotypic Tolerance via Nutrient Restoration [17]

- Culture Preparation: Grow wild-type and high-persistence mutant (e.g., hipA7) E. coli to stationary phase in rich medium.

- Antibiotic Challenge: Treat stationary-phase cultures with ciprofloxacin at 20×MIC for 3-5 hours.

- Nutrient Restoration: Dilute cultures 20-fold into fresh, pre-warmed medium containing the same antibiotic concentration.

- Viability Assessment: Sample cultures at intervals during antibiotic exposure, wash to remove antibiotics, and plate on drug-free agar to quantify surviving colony-forming units (CFUs).

- Data Interpretation: Classify based on survival patterns: persistent populations maintain high survival after nutrient addition, while phenotypically tolerant populations show extensive killing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Persistence Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | E. coli MG1655 (wild-type), E. coli hipA7 (high-persister mutant), MRSA JE2-lux (bioreporter) | Model organisms for persistence mechanisms; lux reporter enables metabolic activity monitoring | Fundamental persistence studies [18] [4] [15] |

| Microfluidic Systems | Membrane-covered microchamber arrays (MCMA) | Single-cell analysis of persister dynamics under controlled environmental conditions | Tracking individual cell histories [15] |

| Metabolic Reporters | Lux-based bioluminescence, ATP assays, ROS-sensitive dyes (e.g., H2DCFDA) | Probing bacterial metabolic state and oxidative stress responses | Assessing dormancy depth and resuscitation [4] [17] |

| TA System Modulators | Inducible toxin expression vectors, antitoxin overexpression plasmids | Dissecting specific TA module contributions to persistence | Mechanistic studies of persistence pathways [14] [18] |

| Host Cell Systems | Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs), human primary neutrophils | Modeling intracellular persistence in host environments | Studying host-induced tolerance [4] |

| Stringent Response Agents | RelA mutants, (p)ppGpp analogs, PPX inhibitors | Manipulating stringent response pathways to probe persistence connections | Investigating stress signaling to dormancy [18] |

| Pkm2-IN-1 | Pkm2-IN-1, MF:C18H19NO2S2, MW:345.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Hdac8-IN-1 | Hdac8-IN-1, MF:C22H19NO3, MW:345.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The distinction between stochastic and triggered persistence has profound implications for antimicrobial therapy development. While stochastic persistence might be addressed through combination therapies that increase the killing cascade effectiveness, triggered persistence offers potential intervention points to prevent persister formation by disrupting environmental sensing or response pathways.

Table 5: Anti-Persister Therapeutic Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Examples | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane-Targeting Agents | Disrupt bacterial membranes independently of metabolic state | XF-73, SA-558, thymol triphenylphosphine conjugates | Preclinical development [5] |

| Metabolic Resuscitation | Reactivate dormant persisters to sensitize them to conventional antibiotics | KL1 (host-directed adjuvant) | Preclinical validation in animal models [4] |

| TA System Disruption | Interfere with toxin-antitoxin modules that maintain persistence | Peptide inhibitors of TA interaction | Early research stage [14] |

| Stringent Response Modulation | Inhibit (p)ppGpp synthesis or signaling | RelA inhibitors, alarmone analogs | Target identification and validation [18] |

| Combination Therapies | Target multiple vulnerabilities simultaneously | Aminoglycoside-polymyxin combinations against Gram-negative persisters | In vitro validation [17] |

| Host-Directed Therapies | Modulate host pathways that induce bacterial dormancy | ROS suppression agents, immune modulators | Early experimental stage [4] |

Current research highlights several promising approaches. The combination of aminoglycosides with polymyxins effectively kills E. coli persisters by synergistic membrane disruption, working through ROS-independent mechanisms that bypass the antioxidant defenses of dormant cells [17]. Host-directed adjuvants like KL1 represent another innovative approach, modulating the host environment to reduce ROS production and resuscitate intracellular bacteria for enhanced antibiotic killing [4]. Additionally, membrane-active compounds such as XF-73 and SA-558 directly target the structural integrity of persister cells, overcoming the limitations of conventional antibiotics that require metabolic activity [5].

Environmental triggers—antibiotic stress, nutrient starvation, and host immune factors—play pivotal roles in bacterial persistence by activating specific molecular pathways that induce dormancy and antibiotic tolerance. The interplay between stochastic and triggered persistence mechanisms underscores the complexity of this phenomenon and the challenges it poses for therapeutic intervention. While stochastic persistence may represent an inevitable bet-hedging strategy in bacterial populations, triggered persistence offers potential intervention points for preventing persister formation by modulating environmental signals or blocking their transduction. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise molecular connections between environmental sensing and persistence effectors, developing standardized methodologies for distinguishing persistence from tolerance in clinical isolates, and translating mechanistic insights into novel therapeutic strategies that target both stochastic and triggered persistence pathways. The integration of single-cell analysis, host-pathogen models, and innovative screening approaches will be essential for advancing our understanding and combating this clinically significant bacterial survival strategy.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the key molecular players in bacterial persistence, focusing on the stringent response and toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems. Within the context of the ongoing debate between stochastic and triggered persistence mechanisms, we synthesize current research on how (p)ppGpp signaling and TA system activation contribute to bacterial survival under stress. The review integrates quantitative data on transcriptional regulation, detailed experimental methodologies for studying persistence, and visual representations of core signaling pathways. Additionally, we provide a comprehensive toolkit of research reagents to facilitate further investigation into these fundamental bacterial survival mechanisms, aiming to support therapeutic development against persistent bacterial infections.

Bacterial persisters represent a non-growing or slow-growing subpopulation of genetically susceptible cells that survive antibiotic treatment and other environmental stresses, contributing significantly to chronic and relapsing infections [1]. The formation of these persister cells is explained by two non-mutually exclusive conceptual frameworks: stochastic formation and triggered induction [13] [1]. The stochastic model posits that persisters arise randomly in bacterial populations through inherent noise in gene expression and biochemical processes, resulting in phenotypic heterogeneity even in uniform environments. In contrast, the triggered induction model suggests that specific environmental stresses actively signal and promote the transition to a persistent state through dedicated molecular pathways.

At the heart of this scientific discourse lie two key molecular systems: the stringent response with its central alarmone (p)ppGpp, and diverse toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems. These systems represent fascinating intersections of stochastic and triggered mechanisms, as they can be activated by specific environmental cues yet also exhibit stochastic activation patterns. This review comprehensively examines the molecular mechanisms, interactions, and experimental evidence surrounding these systems, providing researchers with the technical foundation needed to advance our understanding of bacterial persistence and develop novel therapeutic interventions.

The Stringent Response: (p)ppGpp as Master Regulator

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The stringent response is a universal bacterial stress adaptation system mediated by the alarmones guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) and guanosine pentaphosphate (pppGpp), collectively known as (p)ppGpp [19] [20]. These nucleotides function as master regulators that extensively rewire cellular physiology in response to nutrient deprivation and other stresses, modulating the expression of up to one-third of all bacterial genes [21] [20]. The synthesis and hydrolysis of (p)ppGpp are primarily governed by enzymes of the RelA/SpoT Homologue (RSH) superfamily [19].

In Escherichia coli and other Gammaproteobacteria, RelA is a ribosome-associated (p)ppGpp synthetase that becomes activated by direct binding to ribosomes harboring deacylated tRNA in the A-site – a clear signal of amino acid starvation [19]. This activation mechanism represents a classic triggered response pathway. Structural studies using cryo-EM have revealed that RelA adopts an open conformation on the ribosome that facilitates (p)ppGpp synthesis [19]. In contrast, SpoT is a bifunctional enzyme capable of both synthesizing and hydrolyzing (p)ppGpp, responding to a broader range of stresses including fatty acid limitation, iron restriction, and other environmental challenges [19] [20].

Table 1: Enzymes Involved in (p)ppGpp Metabolism and Their Regulation

| Enzyme | Primary Function | Activation Signals | Cellular Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| RelA | (p)ppGpp synthesis | Deacylated tRNA in ribosomal A-site (amino acid starvation) | RNA polymerase, transcriptional machinery |

| SpoT | (p)ppGpp synthesis AND hydrolysis | Fatty acid limitation, iron restriction, multiple stresses | Multiple targets including RNA polymerase |

| Small Alarmone Synthetases (SAS) | (p)ppGpp synthesis | Various stresses in species-specific manners | Species-specific targets |

Once synthesized, (p)ppGpp exerts profound effects on cellular physiology through multiple mechanisms. Its primary target in Gammaproteobacteria is RNA polymerase, where it acts in concert with the cofactor DksA to dramatically alter transcriptional patterns [21]. This interaction promotes the expression of biosynthetic genes while repressing transcription of ribosomal RNA and transfer RNA genes, effectively redirecting cellular resources from growth to maintenance and survival [19] [20]. Additionally, (p)ppGpp directly binds to and modulates the activity of numerous metabolic enzymes involved in nucleotide synthesis, ribosome biogenesis, and lipid metabolism [19].

Figure 1: The Stringent Response Signaling Pathway. Environmental stresses activate RelA and SpoT enzymes, leading to (p)ppGpp accumulation that binds RNA polymerase with DksA to drive transcriptional reprogramming and cellular adaptation toward a persistent state.

Quantitative Aspects of (p)ppGpp Signaling

Recent research has revealed that the stringent response operates not as a simple binary switch but as a graded system where (p)ppGpp accumulation is proportional to stress severity. A 2025 study on Pseudomonas aeruginosa demonstrated that treatment with increasing concentrations of serine hydroxamate (SHX) – a serine analog that induces amino acid starvation – resulted in dose-dependent (p)ppGpp accumulation and corresponding growth inhibition [21]. The IC₅₀ for SHX-mediated growth inhibition was determined to be 128 ± 24 µM, with (p)ppGpp levels increasing 1.33-fold, 1.39-fold, and 1.48-fold under mild, intermediate, and acute stringent response conditions, respectively [21].

This graded (p)ppGpp response produces correspondingly graded transcriptional changes. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that mild stringent response conditions affected just 4% of the genome (227 differentially expressed genes), while intermediate and acute conditions affected 20% (1,197 genes) and 25% (1,508 genes) of the genome, respectively [21]. The regulatory pattern follows a "layer-by-layer" principle, where increasing stress severity engages progressively more cellular pathways in the transcriptional response.

Table 2: Graded Transcriptional Response to (p)ppGpp Levels in P. aeruginosa

| Stringent Response Level | SHX Concentration | (p)ppGpp Increase (fold) | Differentially Expressed Genes | Key Affected Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | 100 µM | 1.33× | 227 (4% of genome) | Initial metabolic adjustments, motility suppression |

| Intermediate | 500 µM | 1.39× | 1,197 (20% of genome) | Growth and metabolism reduction, biofilm promotion |

| Acute | 1000 µM | 1.48× | 1,508 (25% of genome) | Virgene repression, ribosome biogenesis downregulation, strong biofilm induction |

The functional consequences of this graded response include progressive impairment of motility, promotion of biofilm formation, and development of antimicrobial tolerance [21]. At higher (p)ppGpp levels, biofilm-related genes are upregulated at the expense of virulence factors, promoting the formation of condensed biofilms with enhanced tolerance properties [21].

Toxin-Antitoxin Systems: Multifaceted Genetic Elements

Classification and Molecular Mechanisms

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are genetic modules composed of a stable toxin protein that inhibits bacterial growth and a labile antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin [22] [23]. These systems are classified into six types (I-VI) based on the nature of the antitoxin and its mechanism of action [22] [23].

Type I systems feature a protein toxin whose translation is inhibited by an antisense RNA antitoxin that binds complementarily to the toxin mRNA. The toxins are typically small, hydrophobic proteins that form pores in bacterial membranes, disrupting membrane potential and ATP synthesis [22] [23]. Well-characterized examples include hok/sok and tisB/istR, with the latter being induced during the SOS response to DNA damage [22].

Type II systems represent the most extensively studied class, comprising a protein toxin neutralized by a protein antitoxin that forms a stable complex with the toxin [22] [23]. The toxins employ diverse mechanisms including mRNA cleavage (MazF, RelE), DNA gyrase inhibition (CcdB), translation inhibition through distinct mechanisms (VapC, HipA), and cell wall synthesis disruption (PezT) [22] [23]. These systems typically autoregulate their own transcription through TA complex binding to promoter regions.

Type III systems consist of a protein toxin neutralized directly by an RNA antitoxin that binds and inhibits the toxin protein [22]. The toxIN system from Erwinia carotovora was the first identified example of this type.

Types IV-VI represent more recently discovered mechanisms. Type IV systems feature antitoxins that prevent toxin binding to cellular targets rather than directly binding the toxin itself. Type V systems contain antitoxins that are RNAases specifically cleaving toxin mRNAs. Type VI systems have antitoxins that promote degradation of the toxin protein [22].

Figure 2: Toxin-Antitoxin System Regulation. Environmental stress triggers antitoxin degradation and increased TA transcription. However, recent evidence suggests antitoxin in complex with toxin is protected from degradation, challenging the traditional view of stress-induced toxin activation.

Biological Functions and Controversies

TA systems were originally discovered as plasmid stabilization elements through "post-segregational killing" - a process where plasmid-free daughter cells are eliminated due to persistent toxin activity after antitoxin degradation [22] [23]. Chromosomal TA systems have been proposed to serve various functions including stress management, phage defense through abortive infection, and persister formation [22].

However, the functional roles of chromosomal TA systems remain controversial and actively debated. While early studies suggested that TA systems were key players in stress response and persister formation, recent research has challenged these paradigms [24]. A comprehensive 2020 study demonstrated that although diverse stresses (amino acid starvation, translation inhibition, oxidative stress, heat shock) induce substantial transcriptional activation of TA systems (often exceeding 10-50 fold increases in mRNA levels), this transcriptional induction does not necessarily lead to toxin liberation or activity [24].

The mechanistic insight underlying this discrepancy involves differential stability of antitoxin pools. Free antitoxin is rapidly degraded by proteases like Lon and ClpP during stress, but antitoxin in complex with toxin is protected from proteolysis, preventing significant toxin release [24]. This protection mechanism maintains toxin inhibition despite dramatic increases in TA transcription. Supporting this model, a strain of E. coli lacking 10 chromosomal TA systems (Δ10TA) showed no growth advantage following exposure to multiple stresses compared to wild-type strains [24].

Integration and Interplay in Persister Formation

Molecular Convergence on Persistence

The stringent response and TA systems represent complementary and potentially interconnected mechanisms in bacterial persistence. While early models proposed a hierarchical relationship with (p)ppGpp activating TA systems through stimulation of Lon protease-mediated antitoxin degradation [19], recent evidence challenges this linear pathway [24]. Instead, both systems appear to converge on similar cellular outcomes through parallel mechanisms.

Both systems implement a growth-to-survival transition by inhibiting energy-intensive processes. The stringent response achieves this through transcriptional reprogramming that downregulates ribosome biogenesis, DNA replication, and flagellar assembly while upregulating stress response and amino acid biosynthesis genes [21]. TA systems directly target central cellular processes including translation (MazF, RelE, VapC), DNA replication (CcdB), and cell wall synthesis (PezT) [22] [23].

A key point of integration involves metabolic regulation. The stringent response directly modulates metabolic enzymes and pathways, while recent research has demonstrated that stochastic fluctuations in energy-generating enzymes themselves can drive persister formation [13]. Cells with lower levels of Krebs cycle enzymes (isocitrate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase) show enhanced survival against ciprofloxacin, and direct measurement of ATP levels using ratiometric sensors revealed that subpopulations with low ATP are enriched in persisters [13].

Resolving Stochastic versus Triggered Mechanisms

The interplay between the stringent response and TA systems provides a framework for reconciling stochastic and triggered persistence mechanisms. The graded nature of the (p)ppGpp response [21] allows for proportional cellular adaptation to stress severity, representing a triggered mechanism. However, heterogeneity in (p)ppGpp accumulation or response thresholds within isogenic populations could introduce stochastic elements.

For TA systems, the balance appears shifted toward stochasticity. While TA transcription is strongly induced by stress [24], the protection of TA complexes from degradation [24] means that stochastic fluctuations in TA expression or complex formation in subpopulations may be more significant for persistence than stress-induced activation. This model is consistent with the "low energy" hypothesis of persister formation, where stochastic heterogeneity in energy-generating components creates subpopulations with low ATP that are intrinsically tolerant to antibiotics [13].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Stringent Response and TA Systems in Persistence

| Feature | Stringent Response | Toxin-Antitoxin Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Primary signaling molecule | (p)ppGpp | Protein toxins (various types) |

| Activation mechanism | Triggered by nutrient limitation and other stresses | Both stochastic expression and stress-induced transcription |

| Major molecular targets | RNA polymerase, metabolic enzymes, replication initiation | mRNA (type II RNases), DNA gyrase, cell wall synthesis, translation |

| Temporal response | Rapid (minutes) | Varies by system |

| Evidence for persistence role | Strong and consistent across studies | Controversial, with recent challenges |

| Therapeutic targeting potential | High (central regulator) | Uncertain due to functional redundancy |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Key Protocols for Investigating Persistence Mechanisms

Inducing and Measuring the Stringent Response:

The stringent response can be experimentally induced using serine hydroxamate (SHX), a serine analog that inhibits seryl-tRNA synthetase and creates amino acid starvation conditions [21]. Standard protocol involves adding SHX at concentrations ranging from 10-1000 µM to exponentially growing cultures, with higher concentrations producing more severe stringent response activation [21]. The (p)ppGpp levels can be quantified using thin-layer chromatography or high-performance liquid chromatography to separate and measure nucleotide pools [21]. For transcriptional analysis, RNA sequencing reveals the comprehensive transcriptomic changes associated with different levels of stringent response activation.

Single-Cell ATP Measurement:

To investigate the relationship between energy status and persistence, the iATPSnFr1.0 ratiometric ATP sensor can be employed [13]. This reporter incorporates a circularly permuted superfolder GFP and an ATP-binding subunit from Bacillus PS3 F0F1 ATP synthase. It is excited at two wavelengths (405 nm and 488 nm) with emission at 515 nm, and the ratio between signals (488ex/405ex) provides a self-normalized measure of ATP concentration that is independent of reporter expression levels [13]. This sensor can be expressed from the chromosome under a constitutive promoter for continuous monitoring.

Microfluidics and Time-Lapse Microscopy:

Mother machine microfluidic devices enable tracking of individual bacterial lineages under controlled conditions [13]. These devices contain growth trenches orthogonal to a media channel, with bacteria at the dead ends of trenches ("mother cells") serving as progenitors for linearly growing populations. This setup allows for continuous observation of growth, division, and survival of thousands of individual cells before, during, and after antibiotic exposure when combined with time-lapse microscopy [13].

TA System Transcriptional Analysis:

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) can monitor TA system transcription under various stress conditions [24]. Stresses including amino acid starvation (SHX), translation inhibition (chloramphenicol), DNA synthesis inhibition (trimethoprim), oxidative stress (hydrogen peroxide), and heat shock effectively induce TA transcription. For population heterogeneity assessment, promoter-yfp fusions can determine whether transcriptional responses occur uniformly or in subpopulations [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Persistence Mechanisms

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Serine Hydroxamate (SHX) | Induces amino acid starvation and stringent response | Dose-dependent effects (10-1000 µM); IC₅₀ ~128 µM in P. aeruginosa |

| iATPSnFr1.0 ATP sensor | Ratiometric measurement of ATP at single-cell level | Dual excitation (405/488 nm), emission at 515 nm; self-normalizing via ratio |

| Mother machine microfluidic devices | Single-cell tracking under controlled conditions | Enables observation of thousands of individual lineages; compatible with time-lapse microscopy |

| Δ10TA E. coli strain | Testing TA system functions in stress response | Lacks 10 chromosomal type II TA systems; must verify absence of ϕ80 prophage contaminants |

| QUEEN series ATP sensors | Alternative ATP measurement tools | Lower fluorescence in some bacterial systems; potential toxicity at high expression |

| Promoter-yfp fusions | Monitoring transcriptional dynamics in single cells | Enables assessment of population heterogeneity in stress responses |

| K-Ras(G12C) inhibitor 12 | K-Ras(G12C) inhibitor 12, MF:C15H17ClIN3O3, MW:449.67 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ALK inhibitor 2 | ALK inhibitor 2, CAS:761438-38-4, MF:C23H28ClN7O3S, MW:518.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The intricate interplay between the stringent response and TA systems represents a complex regulatory network that influences bacterial persistence through both stochastic and triggered mechanisms. The graded nature of the (p)ppGpp response enables precise adaptation to stress severity, while the stochastic activation of TA systems and heterogeneity in energy metabolism contribute to phenotypic variation in isogenic populations.

Future research should focus on quantifying the relative contributions of these systems to persistence across different bacterial species and stress conditions. The development of improved dynamic reporters for both (p)ppGpp levels and TA system activity in single cells will be crucial for understanding the temporal dynamics of persistence formation. Additionally, exploring the potential crosstalk between these systems and other regulatory networks, such as those controlling metabolism and epigenetic modifications, may reveal novel layers of regulation.

From a therapeutic perspective, targeting the stringent response represents a promising approach for combating persistent infections, given its central role in coordinating stress adaptation. However, the conservation of (p)ppGpp signaling across bacteria and its connection to essential physiological processes present challenges for specific inhibition. TA systems offer more targeted opportunities but face challenges due to functional redundancy and questions about their precise roles in persistence. As our understanding of these key molecular players continues to evolve, so too will our ability to develop innovative strategies against persistent bacterial infections.

Drug tolerance, a reversible non-genetic capacity of bacterial cells to survive antibiotic treatment, represents a significant challenge in managing persistent infections. Unlike genetic resistance, tolerance is a phenotypic state characterized by reduced metabolic activity and growth arrest, allowing pathogens to withstand lethal antibiotic concentrations. This whitepaper examines the central role of ATP depletion and metabolic dormancy as fundamental hallmarks of the drug-tolerant persister phenotype. Within the context of ongoing scientific debate, we analyze evidence supporting both stochastic and triggered formation mechanisms of persister cells. Through synthesis of current research findings, experimental protocols, and emerging therapeutic strategies, this review provides a technical framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to overcome the limitations of conventional antibiotics against dormant bacterial populations.

Bacterial persisters represent a growth-arrested subpopulation of cells that exhibit extraordinary tolerance to antibiotics without undergoing genetic mutations [5] [25]. These phenotypic variants can survive antibiotic concentrations that kill the majority of their genetically identical counterparts and possess the capacity to resume growth once antibiotic pressure is removed, potentially leading to relapsing infections [26] [27]. This phenomenon differs fundamentally from antibiotic resistance, which is heritable and involves genetic changes that increase the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [28]. In contrast, drug tolerance does not alter the MIC but extends the time required to kill a bacterial population, characterized by an increased minimum duration for killing (MDK99) [28].

The clinical importance of persister cells is profound, as they contribute significantly to recalcitrant infections that are difficult to eradicate. Persisters play established roles in chronic lung infections in cystic fibrosis patients, medical device-associated infections, and Lyme disease [5] [25]. Their presence in bacterial populations provides a reservoir from which antibiotic-resistant mutants may emerge over time, compounding the global antimicrobial resistance crisis [25]. Understanding the metabolic underpinnings of drug tolerance, particularly the roles of ATP depletion and growth arrest, is therefore critical for developing novel therapeutic interventions against persistent infections.

Core Metabolic Mechanisms of Drug Tolerance

Energy Depletion and ATP Reduction

A fundamental metabolic hallmark of persister cells is a significantly reduced ATP pool, which creates a state of metabolic quiescence incompatible with antibiotic-mediated killing. Direct measurements using ratiometric ATP sensors such as iATPSnFr1.0 have demonstrated that bacterial subpopulations with low intracellular ATP levels exhibit enhanced survival under antibiotic pressure [13]. This correlation was established through microfluidics time-lapse microscopy experiments tracking single-cell ATP levels and survival outcomes, providing robust evidence for the low-energy mechanism of persister formation.

The connection between impaired energy metabolism and persistence is further supported by genetic studies. Escherichia coli mutants lacking isocitrate dehydrogenase (icd), which catalyzes the rate-limiting step of the Krebs cycle, displayed lower ATP levels and increased persistence to ciprofloxacin compared to wild-type strains [13]. Similarly, mutants in sucB (α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase) and ubiF (involved in ubiquinone biosynthesis) demonstrated deficient energy production and altered persister formation [26] [27]. These findings collectively indicate that disruptions in core energy-generating pathways promote a drug-tolerant state through ATP depletion.

Metabolic Slowdown and Growth Arrest

Antibiotics typically target active cellular processes such as cell wall synthesis, DNA replication, and protein translation, making rapidly dividing cells particularly vulnerable [28] [5]. Persister cells evade these mechanisms through coordinated metabolic slowdown, reducing or suspending the processes targeted by conventional antibiotics. This programmed dormancy represents a successful survival strategy against antimicrobial agents whose efficacy depends on metabolic activity [28].

This metabolic reprogramming involves reduced tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle activity and a shift toward lipid anabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [28]. The subsequent thickening of the mycobacterial cell wall further reduces drug penetration, creating a physical barrier that complements metabolic dormancy. Similar observations of metabolic downshifting have been reported in Staphylococcus aureus persisters, which maintain active but reconfigured metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, TCA cycle, and pentose phosphate pathway, albeit at reduced levels [26].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Features of Drug-Tolerant Persister Cells

| Metabolic Feature | Functional Consequence | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced ATP levels | Decreased energy availability for cellular processes | Single-cell ATP measurements using iATPSnFr1.0 reporter [13] |

| Impaired Krebs cycle activity | Limited ATP production through oxidative phosphorylation | icd mutants with increased persistence [13] |

| Metabolic slowdown | Reduced activity of antibiotic targets | Transcriptional downregulation of metabolic genes [26] [27] |

| Metabolic shifting | Alternative pathway utilization for homeostasis | Shift from TCA cycle to lipid anabolism in M. tuberculosis [28] |

| Proton motive force disruption | Collapse of membrane energetics | Thioridazine sensitivity studies [29] |

Regulatory Systems Controlling Metabolic Dormancy

The transition to a metabolically dormant state is orchestrated by sophisticated regulatory networks that sense environmental stress and implement survival programs. The stringent response, mediated by the alarmone ppGpp, serves as a master regulator of persistence under nutrient limitation [26] [27]. ppGpp accumulation triggers comprehensive transcriptional reprogramming that redirects cellular resources from growth to maintenance, promoting antibiotic tolerance across multiple bacterial species.

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems represent another key regulatory module in persister formation. These genetic elements encode a stable toxin that disrupts essential cellular processes and a labile antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin [28] [26]. Under stress conditions, activation of TA systems through antitoxin degradation or impaired synthesis leads to toxins such as HipA phosphorylating glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, which inhibits translation and mimics nutrient starvation, thereby inducing persistence [26] [13]. Additional toxins including TisB and HokB form membrane channels that dissipate the proton motive force, further reducing ATP levels and promoting dormancy [13].

In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, WhiB transcription factors and sigma factors function as critical stress regulators that coordinate the response to antibiotic pressure [28]. WhiB7 activation upon drug exposure upregulates drug efflux pumps and readjusts cellular processes to compensate for metabolic disruptions, while sigma factors SigB, SigE, and SigF modulate transcription to favor survival under stress.

Stochastic Versus Triggered Persister Formation Mechanisms

The origin of persister cells within isogenic bacterial populations remains a subject of intense investigation, with evidence supporting both stochastic and environmentally triggered formation mechanisms.

Stochastic Formation Model

The stochastic formation model posits that persisters arise spontaneously in growing populations due to random fluctuations in gene expression or protein abundance, without requiring external triggers. Support for this model comes from single-cell studies demonstrating that fluctuations in the expression of energy-generating enzymes precede persister formation [13]. When populations were sorted based on expression levels of Krebs cycle enzymes (GltA, Icd, SucA), subpopulations with low abundance of these proteins showed significantly higher survival rates under antibiotic treatment.

This model is further supported by the observed heterogeneity in ATP levels within bacterial populations, where cells with naturally low ATP before antibiotic exposure are more likely to survive treatment [13]. The stochastic variation in metabolic components creates a pre-existing reservoir of potential persister cells that become selected under antibiotic pressure, rather than being induced by the stress itself.

Triggered Formation Model

In contrast, the triggered formation model suggests that persisters form in direct response to environmental cues or stresses. Numerous studies have demonstrated that various stressors can induce persistence as an adaptive response. These inducing factors include:

- Nutrient limitation: Starvation for amino acids, carbon sources, or other nutrients dramatically increases persister frequency [26] [27]

- Antibiotic exposure: Sublethal antibiotic concentrations can activate stress responses that promote persistence to subsequent lethal doses [28]

- Other environmental stresses: pH change, oxidative stress, and immune system components can trigger persister formation [5]

These triggers often activate the stringent response and TA systems, initiating a programmed transition to dormancy [26]. The identification of specific signaling molecules that modulate persistence, including quorum sensing peptides and metabolic byproducts, provides additional support for regulated, inducible formation mechanisms [5] [25].

Integrated Perspective

The stochastic and triggered models are not mutually exclusive, and current evidence suggests both mechanisms likely operate simultaneously or sequentially in bacterial populations. Random fluctuations in metabolic proteins may establish a baseline persister level, while environmental stressors can amplify this subpopulation through induced dormancy programs. This integrated perspective acknowledges the complex interplay between intrinsic heterogeneity and responsive regulation in bacterial survival strategies.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Stochastic vs. Triggered Persister Formation

| Aspect | Stochastic Model | Triggered Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary driver | Random fluctuations in gene expression and protein abundance | Environmental stressors and signaling molecules |

| Key evidence | Single-cell heterogeneity in Krebs cycle enzymes and ATP before antibiotic exposure [13] | Increased persister levels following nutrient limitation or sublethal antibiotic exposure [28] [27] |

| Timeframe | Pre-existing before antibiotic challenge | Induced during or before antibiotic challenge |

| Regulatory systems | Natural variation in metabolic components | Stringent response, TA systems, sigma factors [28] [26] |

| Therapeutic implications | Targeting variable subpopulations; preventing formation | Intercepting stress signaling; blocking induction |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Single-CATP Level Monitoring

Cutting-edge approaches for monitoring persister metabolism employ ratiometric ATP biosensors such as iATPSnFr1.0, which enable real-time tracking of ATP dynamics in individual cells [13]. This reporter system utilizes a circularly permuted superfolder GFP coupled to an ATP-binding domain from Bacillus PS3 F0F1 ATP synthase, producing distinct fluorescence signals at two excitation wavelengths (405 nm and 488 nm) with emission at 515 nm.

Protocol for single-cell ATP monitoring:

- Clone iATPSnFr1.0 under a constitutive promoter into the chromosome of target bacteria

- Grow cultures to desired growth phase and load into microfluidics devices (e.g., mother machine)

- Acquire time-lapse images using dual-excitation microscopy (405 nm and 488 nm)

- Calculate 488ex/405ex ratio for individual cells to determine ATP concentrations

- Track cell survival and division events following antibiotic exposure

- Correlate pre-treatment ATP levels with survival outcomes

This methodology enabled the demonstration that E. coli cells with low ATP before ampicillin treatment had significantly higher survival rates, providing direct evidence for the energy depletion mechanism of persistence [13].

Metabolic Flux Analysis

Isotopolog profiling using 13C-labeled substrates represents another powerful technique for investigating persister metabolism [26]. This approach enables mapping of relative metabolic pathway activities by tracking the incorporation of labeled carbon atoms into metabolic intermediates.

Protocol for 13C-isotopolog profiling of persisters:

- Grow bacterial cultures to stationary phase to enrich for persisters

- Challenge with bactericidal antibiotics (e.g., daptomycin) at appropriate concentrations

- Feed 13C-labeled carbohydrates (e.g., glucose, pyruvate) to surviving persisters

- Extract intracellular metabolites at specific time points

- Analyze labeling patterns in amino acids and other metabolites via GC-MS or LC-MS

- Reconstruct relative metabolic flux through glycolysis, TCA cycle, and pentose phosphate pathway based on isotopolog distributions

Application of this technique to S. aureus persisters revealed active amino acid anabolism and continued operation of central metabolic pathways, albeit at altered levels compared to normal cells [26].

Genetic Approaches

Genetic screens have identified numerous metabolic genes that influence persister formation when disrupted [27]. These include:

- Transposon mutagenesis screens for persistence mutants

- Construction of chromosomal fluorescent protein fusions to monitor enzyme expression

- Targeted gene knockouts in metabolic pathways (e.g., icd, sucB, glpD)

- Reporter systems for stress response pathways (ppGpp, TA systems)

Visualization of Metabolic Pathways in Persister Formation

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and metabolic transitions involved in persister formation and drug tolerance.

Metabolic Regulation of Bacterial Persistence

Experimental Workflow for Persister Metabolism Analysis

Therapeutic Implications and Research Directions

Anti-Persister Therapeutic Strategies

The unique metabolic features of persister cells present opportunities for targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at eradicating these treatment-recalcitrant subpopulations.