Targeting Metabolic Heterogeneity in Persister Cells: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Breakthroughs

Persister cells, a dormant subpopulation in both bacterial and cancer contexts, exhibit profound metabolic heterogeneity, which is a key driver of antibiotic and chemotherapy treatment failure.

Targeting Metabolic Heterogeneity in Persister Cells: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Breakthroughs

Abstract

Persister cells, a dormant subpopulation in both bacterial and cancer contexts, exhibit profound metabolic heterogeneity, which is a key driver of antibiotic and chemotherapy treatment failure. This article synthesizes the latest research on the non-genetic mechanisms underlying this metabolic diversity, exploring its origins in stochastic gene expression, epigenetic reprogramming, and dynamic feedback loops. We critically evaluate advanced single-cell technologies for profiling persister metabolism and systematically review emerging therapeutic strategies designed to exploit these metabolic vulnerabilities. By integrating foundational concepts with methodological advances and translational applications, this review provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to overcome the challenge of treatment relapse in chronic infections and cancer.

Unraveling the Origins and Molecular Drivers of Metabolic Heterogeneity

FAQ: Understanding Persister Cells

What exactly are persister cells? Persister cells are a subpopulation of cells within an isogenic culture that enter a temporary, non-growing, or slow-growing dormant state, enabling them to survive exposure to high doses of drugs or other environmental stresses without possessing heritable genetic resistance. Upon removal of the stress, these cells can resuscitate and regenerate a susceptible population [1] [2].

How do persister cells differ from resistant cells? The key difference lies in the mechanism of survival. Resistant cells have genetic mutations that allow them to grow in the presence of a drug, and this resistance is heritable. Persister cells, in contrast, are genetically identical to their susceptible siblings and survive through non-genetic, phenotypic mechanisms like dormancy; their tolerance is not passed on to the next generation of cells once they resume growth [3] [2].

Why are persister cells a critical problem in both infectious disease and oncology? In bacterial infections, persisters are a major cause of chronic and relapsing infections (e.g., tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis-related infections) and are implicated in the development of genetic antibiotic resistance [3] [2]. In cancer, drug-tolerant persister (DTP) cells contribute to tumor relapse and the emergence of acquired resistance to targeted therapies and chemotherapies, representing a significant barrier to a cure [1].

What is the role of metabolic heterogeneity in persister cells? Even within an isoclonal population, individual cells can exhibit significant variation in their metabolic states. This metabolic heterogeneity is a fundamental driver of persistence. It acts as a "bet-hedging" strategy, ensuring that a subset of cells with a specific, slow-metabolizing phenotype will survive a sudden environmental stress, such as antibiotic or anti-cancer drug exposure [4].

How can I experimentally isolate and study persister cells? A standard method is to treat a mid-log phase bacterial culture with a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., a fluoroquinolone or an aminoglycoside) for several hours. The surviving cells, which are typically 0.001% to 1% of the total population, are considered persisters. These can be quantified by plating for colony-forming units (CFUs) after drug exposure [2]. For cancer DTPs, cells are exposed to targeted or chemotherapeutic agents, and the surviving, often dormant, subpopulation is analyzed [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Issue: Low or Inconsistent Persister Cell Yields

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inconsistent growth phase of the starter culture.

- Solution: Always use cultures grown to the same optical density (e.g., mid-log phase) and ensure highly reproducible growth conditions, including media, temperature, and shaking speed [2].

- Cause: Inadequate drug concentration or exposure time.

- Solution: Perform a kill curve experiment to establish the minimum drug concentration and exposure time that kills >99.9% of the population. Use a freshly prepared, high-quality drug solution [2].

- Cause: Environmental stressors inducing unintended persistence.

- Solution: Avoid temperature fluctuations, nutrient shifts, or oxygen limitation immediately before and during the persister assay.

Issue: High Variability in Results Between Replicates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Stochastic nature of persister formation.

- Solution: Increase the number of biological replicates (n ≥ 6 is often recommended) to account for the inherent randomness of the phenotype [4].

- Cause: Clumping of cells leading to uneven drug exposure.

- Solution: Vortex and/or briefly sonicate the culture before treatment to ensure a single-cell suspension. Take multiple samples for CFU plating during the dilution steps.

- Cause: Contamination.

- Solution: Maintain strict aseptic technique and regularly check for microbial contamination.

Key Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms

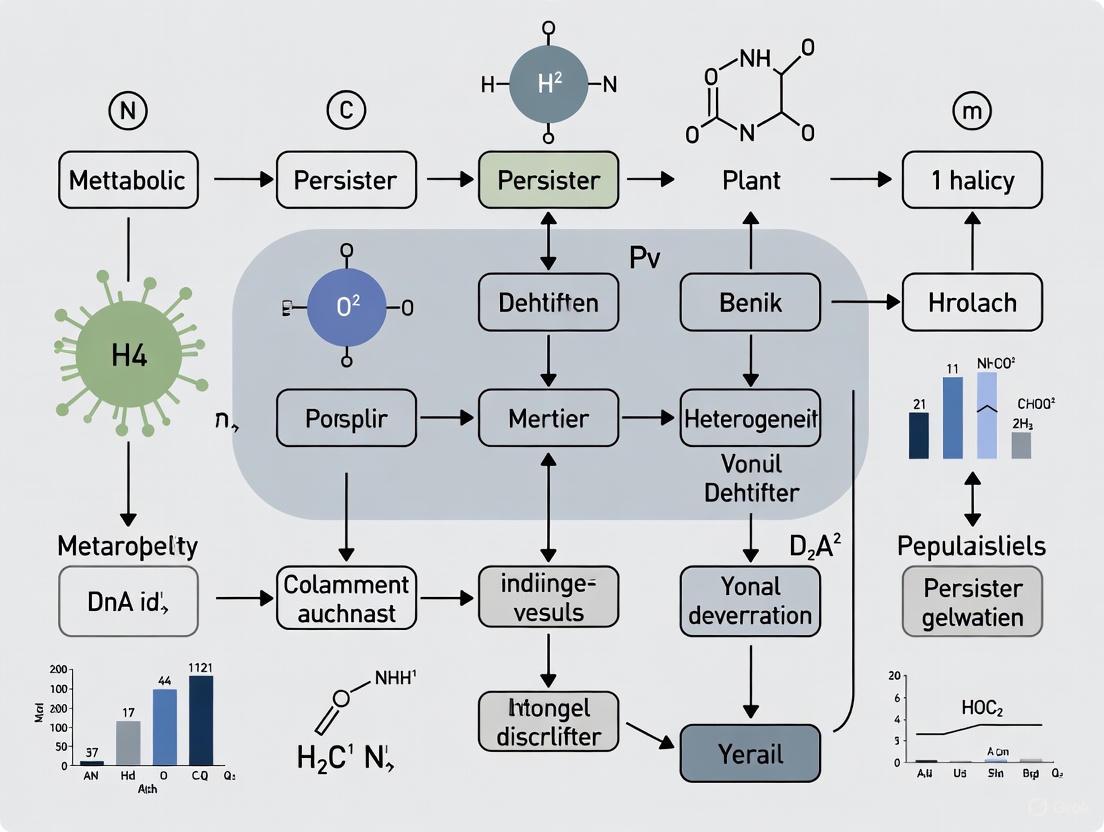

The following diagram illustrates the core pathways and regulatory interactions involved in the formation and survival of bacterial persister cells, integrating mechanisms like toxin-antitoxin systems, stringent response, and metabolic shutdown.

Experimental Protocols for Persister Research

Protocol 1: Isolation of Bacterial Persisters via Antibiotic Killing

Principle: A high dose of a bactericidal antibiotic is used to kill the vast majority of growing cells, leaving behind the non-growing, tolerant persister population for downstream analysis [2].

Procedure:

- Grow culture: Inoculate bacteria in appropriate liquid medium (e.g., LB) and incubate with shaking until mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ~0.5).

- Treat with antibiotic: Add a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., 100x MIC of ciprofloxacin or 100 µg/mL of ampicillin). Continue incubation.

- Sample and quantify: At specific time points (e.g., 0, 2, 5, 24 hours), remove aliquots of the culture.

- Wash and plate: Wash the samples 2-3 times with sterile PBS or saline to remove the antibiotic. Perform serial dilutions and plate on drug-free agar plates.

- Count colonies: After overnight incubation, count the colonies to determine the number of viable persister cells (CFU/mL).

Key Reagents:

- Liquid growth medium

- Bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., Ciprofloxacin, Ampicillin)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Drug-free solid agar plates

Protocol 2: Profiling Metabolic Heterogeneity Using Genetically Encoded Biosensors

Principle: Fluorescent biosensors allow real-time tracking of metabolite levels (e.g., ATP, NADH) in single cells, revealing the metabolic heterogeneity that underpins persister formation [4].

Procedure:

- Engineer biosensor strain: Transform bacteria with a plasmid expressing a FRET-based or transcription factor-based biosensor for a metabolite of interest (e.g., ATP).

- Prepare sample: Grow the sensor strain to mid-log phase and mount a small volume on an agarose pad for live-cell microscopy.

- Image acquisition: Use a fluorescence microscope with appropriate filters and settings to capture images of the bacterial population at high resolution.

- Image analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, CellProfiler) to quantify the fluorescence intensity of the biosensor in individual cells.

- Data interpretation: Plot the distribution of fluorescence intensities across the population. A broad or multimodal distribution indicates significant metabolic heterogeneity.

Key Reagents:

- Genetically encoded metabolite biosensor plasmids

- Selective antibiotics for plasmid maintenance

- Agarose

- Live-cell imaging compatible growth medium

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Persister Cell Research

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bactericidal Antibiotics (Ciprofloxacin, Ampicillin) | Kill growing cells to isolate the non-growing persister subpopulation. | Primary isolation of persisters from bacterial cultures [2]. |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors (e.g., for ATP, NADH) | Enable real-time, single-cell measurement of metabolite levels and dynamics. | Quantifying metabolic heterogeneity and identifying low-metabolism subpopulations [4]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Isolate subpopulations of cells based on specific fluorescence signals (e.g., from biosensors or dye staining). | Sorting and collecting metabolically high vs. low cells for downstream 'omics' analysis or culture [4]. |

| Metabolic Dyes (e.g., CTC for respiration, SYTOX for viability) | Probe the metabolic activity and membrane integrity of cells at a single-cell level. | Distinguishing between dormant, active, and dead cells in a population. |

| ClpP Activators (e.g., ADEP4) | Activate the ClpP protease, leading to uncontrolled protein degradation. | Directly killing persister cells by degrading essential proteins in a growth-independent manner [3]. |

| Membrane-Targeting Compounds (e.g., XF-73, SA-558) | Directly disrupt bacterial cell membrane integrity, causing cell lysis. | Eradicating persisters by targeting a structure that is essential regardless of growth state [3]. |

Bacterial persisters are a subpopulation of cells that exhibit multidrug tolerance, enabling them to survive antibiotic treatment without genetic resistance mutations [2] [5]. These cells are not inherently resistant but exist in a transient, phenotypically distinct state characterized by reduced metabolic activity and growth arrest [6] [7]. The core metabolic features of persisters—quiescence, stress signaling, and energy shifts—represent a significant challenge in treating persistent and biofilm-associated infections [2]. Understanding this metabolic heterogeneity is crucial for developing therapeutic strategies that can effectively target these recalcitrant cells.

Persisters demonstrate remarkable phenotypic heterogeneity, including metabolic diversity, variation in persistence levels, and differences in colony sizes [2]. This heterogeneity exists on a continuum, with some persisters exhibiting "deep" persistence (strong persistence ability) while others demonstrate "shallow" persistence (weak persistence ability) [2]. The metabolic state of persister cells is not fixed but changes dynamically with environmental conditions, creating a complex landscape for researchers to navigate [2]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to address the specific challenges faced by investigators studying metabolic heterogeneity in persister cell populations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Persister Metabolism

FAQ 1: What fundamentally distinguishes persister cells from resistant bacteria at the metabolic level?

Persister cells are characterized by phenotypic tolerance without genetic resistance, while resistant bacteria possess genetic mutations that allow growth in the presence of antibiotics [5]. The key distinction lies in the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)—persisters exhibit an unchanged MIC but survive antibiotic treatment due to a higher minimum duration to kill 99% of the population (MDK99) [5]. Metabolically, persisters typically exist in a slow-growing or non-growing state with reduced metabolic activity, whereas resistant bacteria continue to grow and replicate normally in the presence of antibiotics [6]. When persister cells regrow without antibiotics, their progeny regain susceptibility identical to the parental population [5].

FAQ 2: How does metabolic quiescence enable antibiotic tolerance?

Most bactericidal antibiotics target active cellular processes such as cell wall synthesis, protein production, and DNA replication [6]. Metabolic quiescence allows persisters to avoid these targets through:

- Reduced proton motive force (PMF): Limits uptake of aminoglycoside antibiotics [6]

- Diminished metabolic activity: Decreases antibiotic target corruption [5]

- Downregulated energy production: Low ATP levels reduce activity of antibiotics whose lethality depends on energy metabolism [7] This dormant or slow-metabolizing state is reversible, allowing resumption of growth once antibiotic pressure is removed [2].

FAQ 3: What are the primary metabolic pathways involved in persister formation?

Multiple interconnected pathways regulate persister formation:

- Stringent response: Mediated by the alarmone (p)ppGpp in response to nutrient stress [8]

- Toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules: Act as effectors of ppGpp-induced persistence [8]

- Energy metabolism shifts: Alterations in TCA cycle, ATP production, and proton motive force [7]

- Central carbon metabolism regulation: Changes in glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway, and amino acid biosynthesis [4] [7] These pathways form a complex regulatory network that responds to both stochastic triggers and environmental cues [2] [8].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Persister Metabolism Studies

| Challenge | Potential Causes | Solutions | Supporting Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low persister yields | Insufficient stress induction; inadequate culture conditions; improper antibiotic selection | Extend stationary phase incubation; use biofilm models; optimize antibiotic concentration and treatment duration | Population killing curves; MIC/MDC determinations [5] |

| Inconsistent metabolic measurements | Persister heterogeneity; contamination with normal cells; unstable metabolic state | Implement robust persister isolation; use single-cell approaches; standardize recovery protocols | Microfluidics with membrane-covered microchamber arrays [9]; flow cytometry with sorting [4] |

| Difficulty characterizing metabolic fluxes | Low persister numbers; rapid metabolic changes during isolation; technical limitations | Employ 13C-isotopolog profiling; use genetically encoded biosensors; apply NanoSIMS | Isotopolog profiling [7]; FRET-based metabolite biosensors [4]; nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry [4] |

| Poor response to metabolite supplementation | Impermeable metabolites; incorrect concentration; incompatible with antibiotic mechanism | Test metabolite analogs with better permeability; optimize concentration ranges; match metabolites to antibiotic class | Phenotype microarrays [7]; fluorescent dye-based reductase assays [7] |

| Inadequate separation of persisters | Incomplete killing of non-persisters; antibiotic concentration too low; treatment duration insufficient | Use lytic antibiotics for selection; employ unstable GFP variants; implement fluorescence-activated cell sorting | Unstable GFP-based separation [7]; antibiotic selection protocols [2] |

Advanced Protocol: Single-Cell Analysis of Persister Metabolism Using Microfluidics

Background: Traditional bulk measurements mask the metabolic heterogeneity of persister populations. This protocol utilizes microfluidic devices to track metabolic states of individual persister cells before, during, and after antibiotic treatment [9].

Materials:

- Microfluidic device with membrane-covered microchamber array (MCMA)

- E. coli MG1655 or other target strain

- Antibiotics: ampicillin (200 µg/mL) and ciprofloxacin (1 µg/mL)

- Fluorescence microscopy system with environmental control

- Genetically encoded metabolite biosensors (as needed)

Procedure:

- Device Preparation: Fabricate MCMA with 0.8-µm deep microchambers on glass coverslips [9]

- Cell Loading: Introduce exponential or stationary phase bacterial cells into microchambers

- Medium Control: Establish controlled medium flow above membrane for rapid exchange (within 5 minutes)

- Antibiotic Treatment: Expose cells to lethal antibiotic concentrations (e.g., 12.5×MIC ampicillin or 32×MIC ciprofloxacin)

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Monitor individual cells throughout treatment and recovery phases

- Data Analysis: Track growth history, morphological changes, and resuscitation dynamics of surviving persisters

Expected Results: Recent studies using this approach revealed that most persisters from exponentially growing populations were actively growing before antibiotic treatment, showing heterogeneous survival dynamics including continuous growth with L-form-like morphologies, responsive growth arrest, or post-exposure filamentation [9].

Troubleshooting Tip: For improved cell viability during extended imaging, ensure proper nutrient exchange through the semipermeable membrane and maintain appropriate temperature and humidity control throughout the experiment.

Key Signaling Pathways in Persister Metabolism

The Central Role of ppGpp in Persister Metabolism

The following diagram illustrates the ppGpp-mediated stringent response pathway, a central regulator of metabolic shifts in persister formation:

Diagram 1: ppGpp-Mediated Stringent Response in Persister Formation (76 characters)

The (p)ppGpp-mediated stringent response serves as a master regulator connecting nutrient stress to persister formation [8]. This pathway is activated by various metabolic stresses including glucose starvation and amino acid depletion, leading to increased ppGpp production through RelA activation [7]. Elevated ppGpp levels trigger multiple downstream effects:

- TA system activation: ppGpp induces toxin-antitoxin modules such as HipA, which phosphorylates glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (GltX), inhibiting tRNA loading and further amplifying the stringent response [7]

- Metabolic reprogramming: Direct inhibition of DNA gyrase and RNA polymerase reduces biosynthetic activities [7]

- Energy metabolism shift: Downregulation of TCA cycle and ATP-generating pathways conserves energy [7]

In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, nutrient limitation activates a ppGpp-dependent mechanism directing cells to a state of increased antibiotic tolerance [7]. Similarly, in Staphylococcus aureus, permanent ppGpp synthesis leads to growth inhibition and facilitates persistent infections [7].

Metabolic Activation Strategies for Anti-Persister Interventions

The "wake and kill" strategy aims to reverse metabolic dormancy to resensitize persisters to conventional antibiotics:

Diagram 2: Metabolic Activation Strategy to Eradicate Persisters (67 characters)

This approach leverages the correlation between bacterial metabolic rate and efficacy of bactericidal antibiotics [6]. Key metabolites can stimulate and disrupt metabolic dormancy mechanisms:

- Sugar metabolites: Mannitol restores proton motive force and enhances aminoglycoside uptake [6]

- Central carbon metabolites: Pyruvate promotes gentamicin uptake against antibiotic-resistant Vibrio alginolyticus [6]

- Amino acids: L-valine promotes phagocytosis to kill multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens [6]

- Nucleotides: Exogenous adenosine and/or guanosine enhances tetracycline sensitivity [6]

Research Reagent Solutions for Persister Metabolism Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Persister Metabolism Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Biosensors | FRET-based sensors; Transcription factor-based reporters; RNA aptamer systems | Real-time monitoring of metabolite dynamics in single cells | Couple metabolite concentrations to fluorescent outputs for quantification [4] |

| Isotopic Tracers | 13C-labeled glucose; 15N-labeled ammonium | Metabolic flux analysis in persister populations | Enable isotopolog profiling to determine pathway activities [7] |

| Metabolic Modulators | Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP); Metabolites (mannitol, pyruvate) | Manipulate energy states and test "wake and kill" strategies | Modulate proton motive force and metabolic activity [6] [7] |

| Microfluidic Systems | Membrane-covered microchamber arrays (MCMA); Single-cell cultivation devices | Single-cell analysis of persister formation and resuscitation | Enable tracking of individual cell histories before and after antibiotic exposure [9] |

| Separation Tools | Unstable GFP variants; Fluorescence-activated cell sorting | Isolation of persister subpopulations from heterogeneous cultures | Enable separation of persisters from non-persisters for targeted analysis [7] |

Quantitative Analysis of Persister Metabolic Features

Table 3: Metabolic Parameters in Different Persister Subpopulations

| Metabolic Parameter | Type I Persisters | Type II Persisters | Growing Persisters | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate | Non-growing | Slow-growing (0.001-0.01 hâ»Â¹) | Variable, but detectable division | Single-cell tracking; Time-lapse microscopy [2] [9] |

| ATP Levels | Severely reduced (~5% of normal) | Moderately reduced (~20% of normal) | Near normal with fluctuations | Luciferase-based assays; Fluorescent biosensors [7] |

| Proton Motive Force | Significantly diminished | Partially reduced | Variable, can be restored | Membrane potential-sensitive dyes; FRET reporters [6] |

| Antibiotic Survival Rate | High (up to 1% of population) | Moderate (0.1-0.001% of population) | Lower but significant (0.01-0.0001%) | Killing curves with 12.5×MIC ampicillin or 32×MIC ciprofloxacin [9] |

| Resuscitation Time | Longer lag phase (hours to days) | Shorter lag phase (minutes to hours) | Minimal lag phase (immediate growth) | Microfluidic monitoring after antibiotic removal [9] |

The data presented in Table 3 highlights the continuum of metabolic states in persister populations, from deeply dormant Type I persisters to the recently characterized growing persisters observed in single-cell studies [2] [9]. This heterogeneity underscores the importance of using multiple complementary approaches to fully capture the metabolic diversity of persister cells.

The core metabolic features of bacterial persisters—quiescence, stress signaling, and energy shifts—represent a complex adaptive response that enables survival under antibiotic pressure. Understanding these features at both population and single-cell levels is crucial for developing effective strategies against persistent infections. The experimental approaches and troubleshooting guidance provided here address key challenges in persister metabolism research, from isolation and characterization to targeted intervention.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Developing more sensitive tools for real-time metabolic monitoring in single persister cells

- Elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms linking metabolic states to antibiotic tolerance

- Translating metabolic activation strategies into clinically viable treatments

- Exploring interspecies differences in persister metabolism across clinically relevant pathogens

As research in this field advances, the integration of single-cell technologies with metabolic analysis will continue to reveal the intricate heterogeneity of persister populations, ultimately guiding the development of novel therapeutic approaches that can overcome antibiotic tolerance.

Within clonal microbial populations, even isogenic cells grown in identical environments display significant phenotypic variation. This heterogeneity, driven by the inherent stochasticity of biochemical reactions, presents a substantial challenge in combating persistent infections. Molecular noise—random fluctuations in gene expression—and metabolic heterogeneity—cell-to-cell variations in metabolite levels and fluxes—are critical underlying factors. Research into bacterial persisters, which are dormant, drug-tolerant cells responsible for chronic and relapse infections, is particularly affected by this variability [2]. The stochastic nature of gene expression means that even carefully controlled experiments generate data with substantial cell-to-cell variation, complicating interpretation and requiring specialized troubleshooting approaches. This technical support center addresses the specific experimental challenges and frequently asked questions that arise when investigating these phenomena.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Technical Challenges

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between intrinsic and extrinsic noise in gene expression?

- Intrinsic noise originates from the random, inherent fluctuations in the biochemical processes of transcription and translation of a specific gene. These fluctuations cause independent variation in the expression of two identical genes within the same cell [10] [11].

- Extrinsic noise stems from global, cell-wide fluctuations in factors such as the concentrations of RNA polymerases, ribosomes, or metabolic resources. These variations affect the expression of all genes in a cell in a correlated manner [10] [11].

Q2: How does stochastic gene expression contribute to metabolic heterogeneity in bacterial persisters?

Gene expression is a fundamentally stochastic process characterized by transcriptional bursting, where mRNA molecules are produced in random, pulse-like events [10] [12]. This noise propagates into metabolism because variations in the expression of metabolic enzymes cause cell-to-cell differences in metabolic fluxes and metabolite levels [4] [13]. In persister cells, this can lead to subpopulations with distinct metabolic states, such as metabolic quiescence or slow growth, enabling survival under antibiotic stress [2]. This metabolic heterogeneity is now recognized as a key mechanism underlying bacterial persistence and biofilm-related treatment failures [4] [2].

Q3: My single-cell RNA sequencing data shows a high number of zero-expression values ("dropouts") for a gene of interest. Is this a technical failure?

Not necessarily. While some zero counts are technical artifacts, a significant portion often reflects true biological silence due to transcriptional bursting [12]. Genes transition stochastically between active transcriptional states and inactive, silent states. A zero count in a viable cell can indicate it was captured during a silent phase. This natural variability can be leveraged analytically, as in the single-cell Stochastic Gene Silencing (scSGS) method, which compares active and silent cell subpopulations to infer gene function without genetic perturbation [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Experimental Noise Quantification

This guide addresses common issues when quantifying gene expression noise using dual-fluorescent reporter systems [11].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No correlation in control | Global cellular factors (extrinsic noise) are overwhelming the signal. | Verify cell health and growth conditions; ensure reporters are genomically integrated at identical loci to minimize copy number variation. |

| Excessive independent variation | High intrinsic noise or poor experimental calibration. | Check promoter strength; use a stronger promoter to increase expression levels and potentially reduce the coefficient of variation. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio | Fluorescent proteins are maturing slowly or are unstable. | Use faster-folding fluorescent protein variants (e.g., sfGFP); include proper controls to account for protein half-life. |

| Unexpected bimodality | The promoter may be in a bistable network or the population contains multiple cell states. | Analyze the population for cell cycle stage or other physiological heterogeneity; consider using time-lapse microscopy to track single cells over time. |

Troubleshooting Metabolic Heterogeneity Measurements

This guide assists with challenges in assessing cell-to-cell metabolic variation, relevant to studying persister cell subpopulations [4] [13].

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uninterpretable biosensor data | The biosensor kinetics are too slow for the metabolic dynamics, or the sensor is saturated. | Characterize biosensor response time in vivo; use ratiometric FRET-based biosensors for more quantitative measurements [4]. |

| High background in metabolite detection | Non-specific signal or autofluorescence interfering with measurement. | Include control strains lacking the biosensor; use mass spectrometry-based techniques (e.g., NanoSIMS) for specific, label-free metabolite quantification [4]. |

| Metabolite distributions are always unimodal | The assay may not be sensitive enough to detect rare metabolic subpopulations. | Increase the number of cells analyzed; use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to pre-enrich for rare cells based on a marker before metabolic analysis. |

| Inability to link metabolic state to persistence | Lack of a direct readout connecting a metabolic flux to persister cell viability. | Employ combination assays: sort cells based on a metabolic biosensor (e.g., for ATP) and then subject the sorted populations to antibiotic challenge to quantify persister frequency [4] [2]. |

Key Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Quantifying Intrinsic and Extrinsic Noise with a Dual-Reporter System

This protocol quantifies noise using two fluorescent proteins under identical promoters [10] [11].

- Step 1: Strain Construction. Genomically integrate two expression cassettes into the cell. Each cassette must use an identical promoter to drive the expression of two different fluorescent proteins (e.g., CFP and YFP). Ensure the integration sites are genomically neutral and equidistant from the origin of replication to control for gene copy number effects.

- Step 2: Cultivation and Flow Cytometry. Grow the strain under the defined experimental conditions to mid-exponential phase. Analyze a minimum of 10,000 individual cells using a flow cytometer equipped with lasers and filters appropriate for CFP and YFP.

- Step 3: Data Analysis. For each cell

i, you will have a fluorescence intensity for CFP (C_i) and YFP (Y_i).- Calculate the total noise for a protein (e.g., CFP):

η²_total = ⟨C²⟩ / ⟨C⟩² - 1, where⟨⟩denotes the population mean. - Calculate the extrinsic noise (

η²_ext) from the correlation between CFP and YFP across the population:η_ext ≈ cov(C, Y) / (⟨C⟩⟨Y⟩). - Calculate the intrinsic noise (

η²_int) from the uncorrelated variation:η_int ≈ η²_total - η²_ext.

- Calculate the total noise for a protein (e.g., CFP):

Quantitative Foundations of Heterogeneity

The table below summarizes key quantitative relationships identified in research on stochastic gene expression and metabolic heterogeneity.

| Parameter or Relationship | Quantitative Value or Correlation | Experimental System | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noise vs. Expression Variation | Significant correlation (Predictive model, SVR, achieved high fidelity) [14] | S. cerevisiae | Population-level expression variation can serve as a proxy for single-cell stochastic noise. |

| Promoter Type and Noise | TATA-box containing genes show higher and more predictable noise levels [14] | S. cerevisiae | Specific promoter architectures are major determinants of stochastic gene expression. |

| Metabolic Gene Promoters | Controlled by noisier promoters compared to essential genes [4] | E. coli | Suggests evolutionary tuning to allow large metabolic heterogeneity for bet-hedging. |

| Protein Copy Number | ~10% of repressors and ~50% of activators have ≤10 copies per cell [11] | E. coli | Low abundance of key regulators ensures system-wide susceptibility to molecular noise. |

Essential Visualizations

Quantifying Gene Expression Noise

Origins of Metabolic Heterogeneity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent or Tool | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Dual-Fluorescent Reporter Plasmids | Quantifying intrinsic vs. extrinsic noise by expressing CFP and YFP from identical promoters [11]. | Ensure genomic integration at neutral, matched loci to avoid position effects. |

| Genetically Encoded Metabolite Biosensors | Dynamic, single-cell quantification of metabolite levels (e.g., FRET-based sensors, transcription factor-based reporters) [4]. | Validate sensor response time and dynamic range in your specific model organism and condition. |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) Models | In silico prediction of gene expression noise levels based on population-level expression variation data [14]. | Requires a large compendium of gene expression data across many conditions for training. |

| Microfluidics & Time-Lapse Microscopy | Monitoring gene expression dynamics and metabolic heterogeneity in single cells over multiple generations [10]. | Essential for distinguishing between deep and shallow persister states based on duration of dormancy [2]. |

| scSGS Computational Framework | Leveraging transcriptional bursting patterns in scRNA-seq data to infer gene function without knockout [12]. | Identifies "SGS-responsive genes" by comparing cells in active vs. silenced transcriptional states for a target gene. |

| cl-387785 | cl-387785, CAS:253310-44-0, MF:C18H13BrN4O, MW:381.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Paritaprevir | Paritaprevir, CAS:1221573-85-8, MF:C40H43N7O7S, MW:765.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of Epigenetic Reprogramming and Transcriptional Plasticity in Cancer DTPs

What are Drug-Tolerant Persister (DTP) cells and why are they a problem in cancer therapy?

Drug-Tolerant Persister (DTP) cells are a rare subpopulation of cancer cells that survive standard-of-care therapies not through stable genetic resistance, but via reversible, non-genetic adaptations [15]. Acting as clinically occult reservoirs, DTP cells persist after treatment, seeding relapse long after the visible tumour has regressed [15]. This phenomenon is a major obstacle to achieving durable cancer remission.

The concept was inspired by bacterial persisters first described by Bigger and later identified in cancer by Sharma et al. in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) models treated with EGFR inhibitors [15]. DTPs exhibit a spectrum of adaptive traits including epigenetic reprogramming, transcriptional memory, translational remodelling, metabolic shifts, and therapy-induced mutagenesis across diverse tumour types and treatments [15].

How do DTPs differ from other resistant cell types?

Unlike genetically resistant clones or cancer stem cells (CSCs), DTPs are characterized by their transient, reversible nature and emergence from genetically identical cell populations under therapeutic pressure [15]. Table 1 compares DTPs with other cell states.

Table 1: Characteristic Comparison of DTPs and Related Cell States

| Characteristic | DTPs | Genetically Resistant Cells | Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) | Senescent Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Fraction | Rare subset | Subset (context-dependent) | Subset (context-dependent) | Variable (often large fractions) |

| Growth State | Slow-cycling or quiescent | Proliferating | Self-renewing | Quiescent |

| Treatment Requirement | Induced by lethal treatment | No | No | Context-dependent |

| Genetic Dependency | No | Yes | Partial | Partial |

| Reversibility | Yes, upon drug removal | No | Yes | Irreversible |

| Primary Mechanism | Non-genetic adaptation | Genetic mutations | Stemness programs | Stress-induced arrest |

Molecular Mechanisms & Troubleshooting

What epigenetic mechanisms drive DTP formation and maintenance?

Epigenetic reprogramming serves as a key mechanism enabling cancer cells to acquire stem-like characteristics and drive therapeutic resistance [16]. This involves dynamic alterations to histone modifications and chromatin architecture in response to environmental stimuli like drug exposure [16].

The "writer-reader-eraser" framework governs histone modification dynamics [17] [18]:

- Writers (e.g., HATs, HMTs) add chemical groups to histones

- Erasers (e.g., HDACs, KDMs) remove these modifications

- Readers (e.g., proteins with bromodomains, chromodomains) interpret these marks

In DTPs, this equilibrium is disrupted, creating transcriptionally permissive chromatin regions at genes associated with stemness while silencing differentiation genes [16].

Table 2: Key Epigenetic Regulators Implicated in DTP States

| Epigenetic Regulator | Type | Function in DTPs | Therapeutic Targeting |

|---|---|---|---|

| EZH2 | Writer (HMT) | Represses differentiation genes via H3K27me3 | Tazemetostat (EPZ-6438) [17] |

| BRD4 | Reader | Binds acetylated histones at super-enhancers | BET inhibitors (RO6870810) [17] [19] |

| HDACs | Erasers | Remove acetyl groups, promoting chromatin compaction | HDAC inhibitors [17] |

| DNMTs | Writers | DNA methylation silencing of tumor suppressors | DNMT inhibitors [18] |

| KDM family | Erasers | Demethylate histones, altering gene expression | KDM inhibitors in development [18] |

What experimental approaches can detect and characterize DTP epigenetic states?

Protocol 1: Profiling DTP Epigenetic Landscapes

Materials Required:

- Drug-tolerant cells from appropriate cancer model

- HDAC or BET inhibitors as positive controls

- Antibodies for ChIP (H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K27me3)

- Single-cell RNA-sequencing reagents

- ATAC-sequencing reagents

Methodology:

- DTP Generation: Treat cancer cells with relevant targeted therapy (e.g., EGFR inhibitors for NSCLC, BRAF inhibitors for melanoma) for 7-14 days at clinically relevant concentrations [15].

- Epigenetic Profiling:

- Perform ChIP-seq for activation (H3K27ac, H3K4me3) and repression (H3K27me3) marks

- Conduct ATAC-seq to map chromatin accessibility

- Implement single-cell RNA-seq to resolve heterogeneity

- Data Analysis: Identify differentially accessible regions and super-enhancers driving DTP identity [19].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Low DTP yield: Optimize drug concentration and treatment duration; use viability dyes to isolate persistent cells

- High background in ChIP: Include appropriate negative control regions and validate antibody specificity

- Poor single-cell sequencing data: Check cell viability before loading (>90% recommended)

Diagram 1: Epigenetic Regulation of DTP State. Therapy-induced signals rewire the epigenetic landscape through writer, eraser, and reader proteins, creating permissive chromatin at stemness genes and repressive chromatin at differentiation loci.

Metabolic Heterogeneity & Analysis

How does metabolic heterogeneity influence DTP epigenetics?

Metabolic reprogramming is an evolutionarily conserved strategy for cells facing stress [20]. Cancer cells rewire their metabolism to support energy production and biosynthetic precursors, which directly influences the epigenetic landscape through metabolite availability [20].

Key metabolic-epigenetic connections:

- ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling: Energy status directly affects chromatin modifier activity

- Metabolites as cofactors: α-KG, SAM, Acetyl-CoA, and NAD+ levels regulate epigenetic enzyme function

- Oxidative stress: Impacts epigenetic regulation through redox-sensitive transcription factors

Protocol 2: Assessing Metabolic Heterogeneity in DTP Populations

Materials Required:

- Seahorse XF Analyzer and consumables

- Metabolic modulators (oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone, 2-DG)

- Stable isotope tracers (^13C-glucose, ^15N-glutamine)

- LC-MS equipment for metabolomics

- Fluorescent glucose and nutrient sensors

Methodology:

- Metabolic Flux Analysis:

- Use Seahorse XF Analyzer to measure OCR (oxidative phosphorylation) and ECAR (glycolysis)

- Calculate metabolic phenotypes using basal and stressed conditions

- Stable Isotope Tracing:

- Feed DTPs with ^13C-glucose or ^15N-glutamine

- Track isotope incorporation into TCA intermediates and epigenetic cofactors (acetyl-CoA, SAM)

- Single-Cell Metabolic Profiling:

- Use fluorescent reporters for glucose uptake, mitochondrial membrane potential

- Correlate with epigenetic markers via imaging

Table 3: Metabolic Parameters in DTPs vs. Treatment-Naive Cells

| Metabolic Parameter | DTP Cells | Treatment-Naive Cells | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolytic Rate | Variable (context-dependent) | Typically high | Seahorse ECAR, ^13C-glucose tracing |

| Oxidative Phosphorylation | Often elevated | Variable | Seahorse OCR, mitochondrial staining |

| ATP Levels | Maintained despite stress | High | Luminescent assays, biosensors |

| Acetyl-CoA Production | Reprogrammed | Growth-associated | LC-MS, enzymatic assays |

| SAM Availability | Altered | Normal | Mass spectrometry |

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Inconsistent flux measurements: Normalize to cell number; ensure consistent pretreatment conditions

- Poor isotope incorporation: Optimize tracer concentration and duration

- Metabolite instability: Use rapid quenching methods and maintain cold chain

Diagram 2: Metabolic-Epigenetic Crosstalk in DTPs. Core metabolic pathways generate essential cofactors and energy that directly regulate epigenetic modifications, creating a feedback loop that maintains the DTP state.

Technical Challenges & Solutions

How can we overcome transcriptional heterogeneity in DTP studies?

DTP populations exhibit significant heterogeneity, with multiple phenotypic states coexisting within the same tumor [15]. For instance, single-cell RNA sequencing has shown that DTPs with mesenchymal-like and luminal-like transcriptional states can coexist within breast cancers [15].

Solutions:

- Single-cell multi-omics: Combine scRNA-seq with scATAC-seq to link transcriptional states with chromatin accessibility

- Lineage tracing: Use DNA barcoding to track clonal fates after treatment

- Spatial transcriptomics: Map DTP niches within tumor architectures

What are common pitfalls in DTP experimental models?

Most DTP studies rely heavily on in vitro or ex vivo models, limiting their physiological relevance [15]. Recent efforts have begun to explore minimal residual disease in vivo, including through patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), but these models often lack immune components and don't capture broader systemic influences [15].

Improved Model Systems:

- Patient-derived organoids (PDOs): Maintain tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment cues

- Immunocompetent models: Include relevant immune populations

- 3D culture systems: Better mimic tissue architecture and nutrient gradients

Therapeutic Strategies & Reagents

What therapeutic approaches target DTP epigenetic vulnerabilities?

Combination therapies that target both bulk tumor cells and DTP populations show the most promise. The reversibility of epigenetic modifications makes them particularly attractive drug targets [17] [18].

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Targeting DTP Epigenetic Mechanisms

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epi-drug Inhibitors | Tazemetostat (EZH2i), RO6870810 (BETi), Vorinostat (HDACi) | Target specific epigenetic regulators | Use combination approaches to prevent adaptation |

| MET Inhibitors | TGF-β pathway inhibitors, RTK inhibitors | Reverse EMT plasticity | Context-dependent effects |

| Metabolic Modulators | OXPHOS inhibitors, glycolysis inhibitors | Target DTP energy metabolism | Monitor compensatory pathways |

| PROTAC Degraders | BET-PROTACs, HDAC-PROTACs | Selective protein degradation | Optimize dosing schedules |

| Differentiation Agents | Retinoids, epigenetic primers | Force DTPs out of quiescence | Sequential therapy timing |

Protocol 3: Epi-drug Combination Screening

Materials Required:

- DTP-enriched cell populations

- Epigenetic drug library (HDACi, BETi, EZH2i, DNMTi)

- Viability and apoptosis assays

- Senescence biomarkers (SA-β-gal, γH2AX)

- Drug efflux pump inhibitors

Methodology:

- Primary Screening: Test single agents and combinations in DTP-enriched cultures

- Mechanistic Validation: Assess target engagement (western, qPCR), chromatin changes (ChIP)

- Functional Outcomes: Measure colony formation, tumorsphere formation, drug withdrawal recovery

- In Vivo Validation: Use PDX models with biomarker readouts

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Rapid resistance to single agents: Implement rational combinations from outset

- Poor in vivo efficacy: Consider pharmacokinetic issues, optimize dosing schedule

- Toxicity concerns: Explore intermittent dosing or lower doses in combinations

Future Directions & Advanced Applications

How can AI and multi-omics advance DTP targeting?

The convergence of high-throughput omics technologies and Artificial Intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing drug repositioning strategies, offering new precision tools to identify histone-targeted therapies for solid tumors [17]. AI-driven multi-omics integration is reshaping therapeutic opportunities by uncovering novel drug–target–patient associations with unprecedented accuracy [17].

Emerging Approaches:

- Computational drug repurposing: Leverage known safety profiles of existing drugs for new epigenetic applications

- Patient stratification biomarkers: Identify epigenetic signatures predictive of DTP formation

- Dynamic epigenetic monitoring: Track minimal residual disease through liquid biopsies

What are the key unanswered questions in DTP biology?

Critical research gaps include:

- How do DTPs relate to other cancer cell states (CSCs, senescent cells)?

- What mechanisms govern DTP emergence, persistence, and reactivation?

- How do organ-specific macroenvironments shape DTP behaviors?

- Can we develop reliable biomarkers for clinical detection and monitoring?

The integration of AI, multi-omics, and targeting of chromatin remodelers may herald a transformative shift in cancer management, bridging the gap between biological insights and therapeutic innovation to address the challenge of DTP-driven treatment resistance and relapse.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary molecular mechanisms that contribute to metabolic heterogeneity in bacterial persister populations? Metabolic heterogeneity in persister populations is driven by several key mechanisms:

- Stochastic Gene Expression: Noise in the expression of metabolic enzymes and global regulators leads to cell-to-cell variation in metabolic states, even in isogenic populations [21] [4].

- Alarmone (p)ppGpp Signaling: This central stress response alarmone triggers a global reprogramming of transcription, downregulating proliferative processes like ribosome synthesis and upregulating stress survival pathways, which can vary between cells [22] [21] [23].

- Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Module Activation: Under stress, labile antitoxins are degraded, allowing stable toxins to inhibit essential processes like translation and replication, inducing a dormant, persistent state [24].

- Asymmetric Partitioning: During cell division, cellular components like protein aggregates or transcription factors can be asymmetrically distributed, leading to immediate metabolic differences in daughter cells [4].

Q2: How do ppGpp signaling mechanisms differ between major bacterial classes like Proteobacteria and Firmicutes? The molecular mechanisms of ppGpp signaling are unexpectedly diverse [22]:

- In Proteobacteria (e.g., E. coli): ppGpp directly binds to two sites on RNA polymerase (RNAP), often in concert with the transcription factor DksA, to allosterically regulate hundreds of genes [22].

- In Firmicutes (e.g., Bacillus subtilis): ppGpp indirectly regulates transcription by binding to and inhibiting enzymes involved in GTP synthesis and salvage. This repression of cellular GTP levels indirectly inhibits transcription from promoters that use GTP for initiation, such as those for rRNA [22].

Q3: What is the functional relationship between (p)ppGpp and Toxin-Antitoxin systems in persister formation? (p)ppGpp and TA systems are interconnected components of the stress response network that promote persistence.

- Stringent Response Activation: Nutrient starvation and other stresses trigger a sharp increase in (p)ppGpp levels, initiating the stringent response [22] [21].

- TA System Regulation: The (p)ppGpp-mediated stress signal can lead to the activation of specific TA modules. For instance, in some Firmicutes, ppGpp directly allosterically regulates the transcription repressor PurR, which controls purine biosynthesis genes [22]. Furthermore, the stringent response leads to a general shutdown of translation and a reduction in ATP levels, which can prevent the synthesis of labile antitoxins and promote their degradation, thereby freeing toxins to induce growth arrest and persistence [21] [24].

Q4: Beyond persister formation, what other physiological roles do TA systems play in bacterial pathogens? TA systems are multifunctional and contribute significantly to bacterial pathogenesis through several roles [24]:

- Biofilm Formation: Chromosomally encoded TA modules are involved in the development and maintenance of biofilms, which protect bacteria from antibiotics and host immune responses [24].

- Anti-Phage Defense: Through abortive infection, some TA systems are activated in phage-infected cells, leading to altruistic cell death before the phage can replicate, thus protecting the bacterial population [24].

- Stabilization of Genetic Elements: Plasmid-encoded TA systems function as "addiction modules" via post-segregational killing, ensuring the plasmid is inherited by daughter cells [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low or Inconsistent Persister Cell Frequencies in Stationary-Phase Cultures

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent culture conditions | Monitor growth phase precisely using optical density (OD). Ensure consistent media, temperature, and shaking speed across experiments. | Standardize the inoculum, growth medium, and flask volume-to-medium ratio. Harvest cultures at the same specific OD for stationary-phase studies. |

| Inadequate stress induction | Quantify (p)ppGpp levels directly via mass spectrometry or use a fluorescent reporter to confirm stringent response activation [21]. | Use a defined starvation medium (e.g., for carbon, phosphate, or amino acids) to ensure robust and reproducible (p)ppGpp production. |

| Genetic drift or contamination | Streak for single colonies and re-validate genotype, especially for strains with mutations in stress response pathways (e.g., relA, spoT, dksA, rpoS). |

Use fresh colony inoculum from a frozen stock and perform periodic whole-genome sequencing to check for suppressor mutations. |

Issue: Failure to Detect TA System Toxin Activity or Protein Expression

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable antitoxin counteraction | Co-express the toxin and antitoxin genes from an inducible system. Use Western blotting with specific antibodies to check for toxin and antitoxin protein stability. | Use a tightly regulated, titratable expression system (e.g., arabinose- or rhamnose-inducible) for the toxin gene alone. Induce for short durations to prevent complete growth inhibition. |

| Insufficient stress for TA activation | Measure mRNA levels of the TA operon under different stress conditions (e.g., antibiotic treatment, nutrient starvation) using RT-qPCR. | Apply a defined stressor known to activate the specific TA system. For some systems, this may require adding an antibiotic that induces the SOS response or carbon starvation. |

| Toxin target specificity | Review literature on the toxin's known molecular target (e.g., mRNA, tRNA, ribosomes, DNA gyrase) [24]. | Use a specific biochemical assay to detect the toxin's activity. For example, for an mRNA interferase toxin, detect mRNA cleavage fragments. |

Key Data Tables

Table 1: ppGpp-Mediated Transcription Regulatory Mechanisms Across Bacterial Species

| Bacterial Species / Group | Mechanism of Action | Key Effector Molecules | Primary Transcriptional Outcome | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (Proteobacteria) | Direct binding to RNA Polymerase | ppGpp, DksA, RNAP | Represses ~750 genes (e.g., rRNA, tRNA); Activates amino acid biosynthetic genes [22] | RNA-seq with ppGpp-binding site RNAP mutants [22] |

| Bacillus subtilis (Firmicutes) | Indirect regulation via GTP pool control | ppGpp, GTP biosynthesis enzymes (e.g., Gmk, HprT) | Represses rRNA promoters dependent on GTP for initiation [22] | Measurement of GTP levels and rRNA expression in ppGpp^0^ mutants [22] |

| Francisella tularensis | Direct modulation of a transcription activator | ppGpp, MglA, SspA | Activates virulence gene expression [22] | Characterization of tripartite transcription factor complex binding to RNAP [22] |

| Firmicutes | Allosteric regulation of a transcription repressor | ppGpp, PurR | Derepression of purine biosynthesis genes [22] | Biochemical assays showing ppGpp binding to PurR [22] |

Table 2: Classification and Functions of Major Toxin-Antitoxin System Types

| TA Type | Antitoxin Nature | Mechanism of Antitoxin Action | Toxin Target / Mechanism | Physiological Role(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Antisense RNA | Binds toxin mRNA, inhibiting translation [24] | Membrane integrity / pore formation [24] | Plasmid maintenance, persistence [24] |

| II | Protein | Binds and neutralizes toxin protein [24] | Translation (mRNA cleavage), DNA replication, Cell wall synthesis [24] | Persistence, biofilm formation, phage defense [24] |

| III | RNA | Binds and neutralizes toxin protein directly [24] | Translation inhibition [24] | Persistence, phage defense [24] |

| IV | Protein | Protects the toxin's target [24] | Cytoskeleton assembly (FtsZ) [24] | Persistence [24] |

| V | Protein | Cleaves toxin mRNA [25] | Membrane integrity [25] | Not specified in sources |

| VI | Protein | Tags toxin for proteolytic degradation [24] | Not specified in sources | Not specified in sources |

| VII | RNA | Possibly cleaves toxin mRNA [24] | tRNA acceptor stem inhibition [25] | Not specified in sources |

| VIII | Protein | OligoAMPylation of HEPN RNase [25] | tRNA pyrophosphorylation [25] | Growth control via alarmone signaling [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Measuring (p)ppGpp Levels in Bacterial Cultures Using Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC)

Objective: To quantitatively assess the intracellular levels of the alarmones ppGpp and pppGpp in response to stress, providing a direct readout of stringent response activation.

Principle: Bacterial cells are metabolically labeled with radioactive ^32^P-orthophosphate. Upon induction of stress, nucleotides are extracted and separated via polyethyleneimine (PEI)-cellulose TLC. The (p)ppGpp spots are visualized and quantified using a phosphorimager.

Materials:

- Strains: Wild-type and relevant mutant (e.g.,

relAorrelA spoT) bacterial strains. - Media: MOPS-based defined medium.

- Radioactive Isotope: ^32^P-orthophosphate.

- Stress Inducer: A defined amino acid analog (e.g., serine hydroxamate) or antibiotic.

- Extraction Solution: 2M formic acid, kept on ice.

- TLC Plate: PEI-cellulose F plastic-backed plates.

- Chromatography Solvent: 1.5 M KH~2~PO~4~, pH 3.6.

- Equipment: Phosphorimager or X-ray film.

Procedure:

- Grow and Label: Grow bacterial cultures to mid-exponential phase (OD~600~ ~0.4) in MOPS medium. Add ^32^P-orthophosphate (e.g., 50 μCi/mL) and incubate for at least one generation.

- Induce Stress: Split the culture. To one half, add the stress inducer (e.g., 500 μg/mL serine hydroxamate). The other half serves as an uninduced control.

- Quench and Extract: At specific time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30 minutes post-induction), take 100 μL aliquots and transfer to microcentrifuge tubes containing 50 μL of ice-cold 2M formic acid. Incubate on ice for 30 minutes. Centrifuge at high speed for 5 minutes.

- Spot and Separate: Spot 2-5 μL of the supernatant onto a PEI-cellulose TLC plate. Air dry completely. Develop the TLC plate in the 1.5 M KH~2~PO~4~ solvent until the solvent front is near the top.

- Visualize and Quantify: Air dry the plate. Expose it to a phosphorimager screen overnight. Identify (p)ppGpp spots by comparing their migration to known standards (ATP typically runs near the front, while ppGpp and pppGpp migrate slower). Quantify the spot intensities and normalize to the GTP spot for each sample.

Troubleshooting:

- High Background: Ensure the TLC plate is completely dry before development. Use fresh chromatography solvent.

- No Signal: Confirm the activity of the ^32^P-orthophosphate. Verify that the stressor effectively induces the stringent response in your strain.

Protocol: Evaluating Toxin-Induced Persistence via Ectopic Expression

Objective: To determine the direct contribution of a specific TA system toxin to antibiotic persistence by quantifying the increase in persister cells upon toxin overexpression.

Principle: The toxin gene is cloned under a tightly regulated, inducible promoter. Induction of toxin expression halts the growth of most cells, inducing a dormant state. The culture is then treated with a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic. Only dormant, toxin-induced persisters will survive. After antibiotic removal and toxin repression, the surviving cells can resume growth.

Materials:

- Plasmids: pBAD-TOX (toxin gene under arabinose control), pBAD-Empty (control vector).

- Strains: An E. coli strain with the appropriate genetic background.

- Media: LB broth and LB agar plates.

- Inducers/Repressors: 20% L-Arabinose (inducer), 20% D-Glucose (repressor).

- Antibiotics: A bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., 100 μg/mL ampicillin or 10 μg/mL ofloxacin).

Procedure:

- Transform and Grow: Transform the pBAD-TOX and pBAD-Empty plasmids into the target strain. Grow overnight cultures from single colonies in LB with the appropriate antibiotic.

- Induce Toxin Expression: Dilute overnight cultures 1:1000 into fresh LB with antibiotic. Grow to mid-exponential phase (OD~600~ ~0.4). Split each culture into two. To one subculture, add arabinose (0.2%) to induce toxin expression. To the other, add glucose (0.2%) to keep the toxin repressed. Incubate for 1-2 hours.

- Apply Antibiotic Stress: Take a sample from each subculture, serially dilute it, and plate on LB-glucose plates to determine the total viable count (TVC) before antibiotic addition. To the remaining culture, add the bactericidal antibiotic. Incubate for 3-5 hours.

- Quantify Persisters: After antibiotic treatment, pellet the cells, wash twice with fresh LB to remove the antibiotic, and resuspend in LB-glucose to repress further toxin expression. Serially dilute and plate on LB-glucose plates to determine the number of surviving cells (persisters).

- Calculate Persister Frequency: Persister frequency = (TVC after antibiotic treatment / TVC before antibiotic treatment).

Troubleshooting:

- No Colonies After Induction: The toxin may be too potent. Titrate the inducer concentration (e.g., use 0.02%, 0.002% arabinose) or reduce the induction time.

- High Persistence in Control: Ensure the control plasmid does not contain a toxin gene. Use a fresh, high-concentration antibiotic stock to ensure killing of non-persister cells.

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

ppGpp Signaling Network

Toxin-Antitoxin System Regulation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying ppGpp, TA Systems, and Persister Metabolism

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serine Hydroxamate | Metabolic Inhibitor | Induces amino acid starvation, leading to RelA-dependent (p)ppGpp synthesis. Useful for synchronized stringent response induction. | Concentration and duration of treatment must be optimized to avoid complete growth arrest. |

| pBAD/araC Expression System | Genetic Tool | Tightly regulated, titratable system for controlled overexpression of toxin genes or other stress-related proteins. | Use glucose for full repression. Titrate arabinose concentration to find a sub-lethal level for persistence studies. |

| Fluorescent (p)ppGpp Reporters | Biosensor | Allows single-cell, real-time monitoring of (p)ppGpp dynamics in live cells using flow cytometry or microscopy. | Reveals population heterogeneity in stress response activation [21]. |

| ^32^P-Orthophosphate | Radioactive Tracer | Metabolic labeling for direct detection and quantification of (p)ppGpp and other nucleotides via TLC. | Requires facilities for radioactive work. Provides the most direct measurement of alarmone levels. |

| Lon Protease Mutant Strains | Bacterial Strain | Used to study TA systems where the antitoxin is degraded by the Lon protease. Stabilizes the antitoxin, preventing toxin activation. | Helps confirm the role of specific protease pathways in TA module regulation. |

| ATP-based Cell Viability Assays | Metabolic Assay | Measures cellular ATP levels as a proxy for metabolic activity and viability, crucial for identifying dormant persister cells [21]. | More rapid than CFU plating but correlates with metabolic state rather than direct cultivability. |

| Fluorescent Protein Fusions (GFP/mCherry) | Reporter | Tags proteins of interest (e.g., antitoxins) or promoters to monitor expression localization and dynamics at single-cell level. | Enables visualization of heterogeneity and subcellular localization in real-time. |

| BI-9627 | BI-9627, MF:C16H19F3N4O2, MW:356.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| AS601245 | AS601245, CAS:861411-83-8, MF:C20H16N6S, MW:372.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Conceptual Foundations: Understanding Metabolic Multimodality

What is metabolic multimodality and why is it important in persister cell research?

Metabolic multimodality refers to the phenomenon where bacterial populations exhibit multiple distinct metabolic phenotypes despite genetic identity. In persister cell research, this is crucial because persister cells form a multi-drug tolerant subpopulation within an isogenic bacterial culture that can survive antibiotic treatment. These cells are genetically susceptible but temporarily reside in a slow- or non-growing state, and their formation is strongly influenced by metabolic state transitions. Metabolic multimodality enables bacterial populations to employ bet-hedging strategies, where some cells maintain active metabolism while others enter dormant states, ensuring population survival under fluctuating stress conditions like antibiotic exposure [7] [2].

How do unimodal and bimodal distributions relate to metabolic heterogeneity?

Unimodal distributions represent a continuum of protein levels or metabolic activity across a population, where cells have similar phenotypes with variations about the mean levels. In contrast, bimodal distributions feature two distinct subpopulations with different phenotypic states optimized for different environments. In bacterial persistence, populations often display bimodality, maintaining a small subpopulation of dormant cells in addition to normally growing cells. This bimodality can be advantageous in environments with distinct stress levels, allowing populations to maintain diversity without imposing high metabolic costs on all cells [26].

What key metabolic pathways are involved in persister cell formation?

Several core metabolic pathways and regulators play essential roles in persister formation:

- Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems: These systems comprise a toxin that blocks essential cellular functions and an antitoxin that counteracts the toxin. They act as key regulators of persister formation, often activated by nutrient limitation and stress [7].

- Stringent Response and ppGpp: The alarmone ppGpp is a central mediator of the stringent response to nutrient starvation. It influences persister levels by activating TA systems and other regulatory factors, leading to metabolic downshift and growth arrest [7].

- Energy Metabolism: Enzymes involved in ubiquinone biosynthesis and the TCA cycle contribute to intracellular ATP pools, and their perturbation affects persister levels. Interestingly, both inhibition and enhancement of ATP synthesis have been shown to influence persister formation in different contexts [7].

- Central Carbon Metabolism: Studies using 13C-isotopolog profiling have demonstrated active glycolysis, TCA cycle, and pentose phosphate pathway in Staphylococcus aureus persisters challenged with antibiotics, indicating these pathways remain active but potentially redirected in some persister types [7].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Pathways in Persister Formation

| Metabolic Pathway/Component | Role in Persister Formation | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems | Induces growth arrest and dormancy in response to stress | Gene knockout studies show decreased persister levels [7] |

| Stringent Response (ppGpp) | Mediates response to nutrient starvation; activates TA systems | ppGpp overexpression increases antibiotic tolerance [7] |

| TCA Cycle & Energy Production | Generates ATP; modulates persistence through energy status | Mutants in sucB (TCA cycle) show altered persistence [7] |

| Proton Motive Force (PMF) | Maintains membrane potential for energy production | PMF disruption by TisB increases persister levels [7] |

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

How can I effectively isolate and study persister cell metabolism?

A major challenge in persister research is the natural heterogeneity of bacterial populations and the fact that antibiotics used to isolate persisters alter their naïve metabolic state. Furthermore, persisters typically represent only a small subpopulation, making it difficult to distinguish their metabolism from non-persisters [7].

Solution: Implement specialized isolation and analysis techniques:

- Use lytic antibiotics or unstable GFP-variants to separate persister and non-persister cells before metabolic analysis [7].

- Apply 13C-isotopolog profiling to track metabolic fluxes in persister populations. This technique involves feeding 13C-labeled substrates and analyzing labeling patterns in metabolic intermediates to deduce relative pathway activities without measuring absolute metabolite concentrations [7].

- Utilize phenotype microarrays combined with fluorescent dyes to assay reductase activity as a proxy for overall metabolic activity [7].

Why does my population show unimodal instead of bimodal distributions in stress response?

The emergence of bimodal versus unimodal distributions depends on environmental conditions. Bimodality is typically favored in environments that alternate between two distinct stress levels (e.g., low and high stress), while unimodality becomes more beneficial when there is noise in the environment or multiple intermediate stress conditions [26].

Solution:

- Carefully control environmental parameters to create well-defined alternating conditions if bimodality is desired.

- If studying natural environments where unimodality predominates, focus on characterizing the breadth and shape of the unimodal distribution, as a broader distribution can still enhance population survival in fluctuating conditions [26].

- Consider that unimodal distributions may be a more straightforward bet-hedging strategy for surviving in realistic, noisy environments with multiple stress levels [26].

How can I integrate multi-omics data to understand metabolic heterogeneity?

The volume and heterogeneity of multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) can be challenging to synthesize into actionable insights [27].

Solution: Implement an integrated systems biology approach:

- Use Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) as a framework for integrating multi-omic data. GSMMs provide a mechanistic foundation that bridges genotype and phenotype by incorporating prior biological knowledge [28].

- Apply multimodal machine learning to analyze combined omics datasets. Machine learning can deconstruct biological complexity and extract relevant patterns from heterogeneous data [27] [28].

- Employ tools like the Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) that leverage machine learning to provide predictive models and recommendations for future experiments based on multi-omics data [27].

What methods can characterize metabolic states in persister subpopulations?

Solution: Deploy single-cell or population-level methodologies:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals cellular heterogeneity and relationships between tumor microenvironment and drug resistance in persistent cell populations [29].

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) generates metabolic fluxes based on growth rate maximization assumptions, which can serve as a foundation for predicting proteomics and metabolomics data [27].

- Class Activation Maps (CAMs) technology visualizes features in pathological samples associated with specific metabolic or immune states, helping correlate spatial organization with functional states [29].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol: 13C-Isotopolog Profiling for Persister Metabolic Flux Analysis

Purpose: To identify active metabolic pathways in persister cells by tracing labeled carbon atoms through metabolic networks [7].

Reagents and Equipment:

- 13C-labeled carbon source (e.g., 13C-glucose)

- Appropriate antibiotic for persister selection

- Quenching solution (cold methanol)

- Metabolite extraction buffers

- Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) or LC-MS system

- Data analysis software for isotopolog distribution

Procedure:

- Grow bacterial culture to desired growth phase (stationary phase cultures typically have higher persister levels).

- Challenge culture with appropriate antibiotic to kill non-persisters.

- Harvest persister cells by centrifugation and washing.

- Resuspend persisters in medium containing 13C-labeled carbon source.

- Incubate for specific time intervals to allow metabolite incorporation.

- Quench metabolism rapidly with cold methanol.

- Extract intracellular metabolites.

- Analyze metabolite extracts using GC-MS or LC-MS.

- Determine isotopolog distributions (mass distributions due to 13C incorporation).

- Map isotopolog patterns to metabolic pathway activities.

Expected Results: Stationary phase S. aureus persisters challenged with daptomycin showed active biosynthesis of amino acids with labeling patterns indicating active glycolysis, TCA cycle, and pentose phosphate pathway [7].

Protocol: Flux Balance Analysis with Multi-omics Integration

Purpose: To predict metabolic fluxes and generate biologically plausible multi-omics data for testing algorithms and computational tools [27].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iJO1366 for E. coli)

- COBRApy toolbox or similar constraint-based modeling software

- Omics Mock Generator (OMG) library for synthetic data generation

- Computing environment (Python/Jupyter notebooks)

Procedure:

- Formulate the FBA optimization problem to maximize biomass production:

- Maximize Vbiomass

- Subject to: Σj Sij Vj = 0 (mass balance)

- lbj ≤ Vj ≤ ub_j (flux constraints)

- Set exchange reaction constraints based on experimental conditions.

- Solve the linear programming problem to obtain flux distributions.

- Generate time series data by running batch simulations:

- For each time point, run FBA

- Update extracellular metabolite concentrations based on exchange fluxes

- Continue until carbon source is exhausted

- Derive proteomics data assuming protein expression is linearly related to fluxes.

- Generate metabolomics data assuming metabolite concentrations are proportional to sum of absolute incoming and outgoing fluxes.

Expected Results: The OMG library produces synthetic multi-omics data including fluxes, proteomics, and metabolomics that are biologically plausible though computationally generated, useful for testing analysis pipelines [27].

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Networks

Figure 1: Metabolic Signaling in Persister Formation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Multimodality Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-labeled substrates | Tracing metabolic fluxes through pathways | Isotopolog profiling to identify active pathways in persisters [7] |

| COBRApy toolbox | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis of metabolic networks | Flux Balance Analysis for predicting metabolic fluxes [27] |

| Omics Mock Generator (OMG) | Generates synthetic multi-omics data based on metabolic models | Testing algorithms and computational tools without expensive experimental data [27] |

| Automated Recommendation Tool (ART) | Machine learning library for predictive biology | Recommending next strain designs based on multi-omics data [27] |

| Experiment Data Depot (EDD) | Open source repository for experimental data and metadata | Storing and managing multi-omics experimental data [27] |

| Class Activation Maps (CAMs) | Visualizing features in images that drive AI decisions | Identifying pathological features associated with metabolic states [29] |

Advanced Tools and Techniques for Profiling and Targeting Metabolic States

In the study of bacterial infections, a significant challenge lies in understanding and eradicating persister cells—a subpopulation of genetically susceptible bacteria that enter a transient, slow-growing or dormant state to survive antibiotic treatment [2] [7]. These cells are a primary cause of chronic and recurrent infections, as they exhibit phenotypic heterogeneity, meaning individual cells within a clonal population can exist in diverse metabolic states even under identical environmental conditions [4] [30]. This metabolic heterogeneity is now recognized as a fundamental bet-hedging strategy, ensuring that some cells survive unforeseen stresses, and poses a major obstacle for effective therapeutic interventions [4] [2].

Addressing this challenge requires advanced analytical techniques capable of probing metabolism at the single-cell level. This technical support center focuses on three pivotal methodologies: fluorescent biosensors for real-time monitoring of metabolites and pathways in live cells; Nanoscale Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (NanoSIMS) for mapping isotopic enrichment with ultra-high spatial resolution; and isotopolog profiling for tracing metabolic fluxes within central carbon metabolism. The following sections provide detailed troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions to empower researchers in deploying these powerful tools to dissect the metabolic enigma of persister cells.

Core Analytical Techniques: Principles and Workflows

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three primary single-cell metabolic analytics techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Single-Cell Metabolic Analytical Techniques

| Technique | Key Principle | Spatial Resolution | Metabolic Information | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Biosensors | Couples metabolite concentration to a fluorescent output [4] | Diffraction-limited (~200 nm) | Real-time dynamics of specific metabolites (e.g., ATP, c-di-GMP) [30] | Compatible with live-cell imaging and high-throughput flow cytometry [4] [30] | Requires genetic manipulation; limited to a few analytes simultaneously [4] |

| NanoSIMS | Sputters sample surface with primary ions to generate secondary ions for mass spectrometry [31] | ~50 nm [32] [33] | Elemental and isotopic composition (e.g., 13C/12C, 15N/14N) [34] [32] | Ultra-high spatial resolution; can be combined with stable isotope labeling and other microscopy techniques [34] [31] | Requires high vacuum, chemical fixation; measures atoms, not intact molecules [34] |

| Isotopolog Profiling | Tracks incorporation of 13C from labeled nutrients (e.g., glucose) into metabolic intermediates [7] | Bulk population or, recently, single-cells via coupling to NanoSIMS | Relative fluxes through metabolic pathways (e.g., glycolysis, TCA cycle) [7] | Provides quantitative flux data for entire metabolic networks [7] | Traditionally a bulk technique; single-cell version requires complex sample preparation and analysis [34] |

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams outline the general workflows for key experiments and the central signaling pathways involved in persistence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

General Experimental Design

Q: My persister population is extremely rare. How can I ensure I am analyzing true persisters and not just resistant mutants?