The Physiological Basis of the Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) State: Mechanisms, Detection, and Clinical Implications

This article comprehensively reviews the physiological basis for the induction of the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, a dormant survival strategy employed by bacteria under stress.

The Physiological Basis of the Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) State: Mechanisms, Detection, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the physiological basis for the induction of the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, a dormant survival strategy employed by bacteria under stress. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the molecular triggers and cellular mechanisms driving this state, critiques current and emerging detection methodologies, addresses key challenges in differentiation from similar states, and validates advanced techniques for accurate identification. Understanding the VBNC state is critical for overcoming its role in chronic infections, antimicrobial treatment failures, and diagnostic limitations, thereby informing the development of novel therapeutic and diagnostic strategies.

Unveiling the VBNC State: Core Concepts and Physiological Triggers

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state represents a fundamental survival strategy adopted by numerous bacterial species to endure stressful environmental conditions. This physiological state is defined by two critical characteristics: the loss of culturability on conventional laboratory media typically used for growth, coupled with the maintenance of viability and metabolic activity [1] [2]. In this dormant condition, bacteria cannot proliferate on standard culture media, rendering them undetectable by routine plate counting methods, yet they remain alive with an intact membrane, undamaged genetic material, and continued metabolic function [1]. This phenomenon poses significant challenges across multiple fields, including public health, food safety, and clinical microbiology, as VBNC cells retain their pathogenic potential and can resuscitate when conditions become favorable [1] [2] [3].

The VBNC state differs conceptually from other dormant states such as bacterial persistence. While both represent survival strategies, current research suggests that VBNC cells and persisters may form part of a dormancy continuum, where active cells under stress transition into persisters, which may further develop into VBNC state cells [2]. This distinction is crucial for researchers investigating bacterial survival mechanisms and developing interventions against persistent infections. The study of the VBNC state has gained increasing attention in recent years due to its implications for antimicrobial resistance, diagnostic accuracy, and therapeutic efficacy, necessitating a standardized framework for its investigation and characterization [2].

Core Definition and Diagnostic Criteria for the VBNC State

Essential Diagnostic Criteria

The accurate identification of bacteria in the VBNC state requires the demonstration of three essential criteria, combining both negative and positive indicators of the state:

- Loss of Culturability: The inability to form colonies on conventional culture media appropriate for the bacterial species under investigation, despite the retention of viability. This is demonstrated by no growth on standard agar plates after extended incubation periods [4].

- Membrane Integrity: Maintenance of an intact cell membrane, typically verified through viability staining techniques. The combination of nucleic acid stains SYTO-9 and propidium iodide (PI) is commonly employed, where SYTO-9 penetrates all bacteria with intact membranes (green fluorescence), while PI penetrates only bacteria with damaged membranes (red fluorescence) [1] [3].

- Metabolic Activity: Evidence of ongoing, albeit reduced, metabolic processes. This can be demonstrated through various methods, including:

- Direct Viable Count (DVC): Microscopic counting after treatment with nutrients and DNA gyrase inhibitors [1].

- CTC Reduction: The reduction of 5-cyano-2,3-di-(p-tolyl) tetrazolium chloride to formazan, indicating electron transport activity [1].

- ATP Production: Detection of adenosine triphosphate via luciferase assays [1].

- rRNA Retention: Preservation of ribosomal RNA, detectable through molecular methods [5].

Differentiating VBNC from Dead Cells and Persisters

A critical aspect of VBNC research involves distinguishing truly VBNC cells from dead cells or other dormant states. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics that differentiate these states.

Table 1: Differentiation between VBNC, Dead, and Persister Cells

| Characteristic | VBNC Cells | Dead Cells | Persister Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culturability | Non-culturable | Non-culturable | Culturable (after resuscitation) |

| Membrane Integrity | Intact | Compromised | Intact |

| Metabolic Activity | Reduced but detectable | Absent | Greatly reduced |

| Gene Expression | Altered profile | None | Dormancy-specific |

| Resuscitation | Possible under favorable conditions | Not possible | Possible upon antibiotic removal |

| Detection Methods | DVC, PMA-PCR, FCM | PI staining | Culture after antibiotic removal |

Detection Methodologies: From Conventional to Advanced Approaches

Established Detection Methods

The gold standard techniques for VBNC detection have evolved significantly since the initial description of the phenomenon. Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the primary methods currently employed in VBNC research, along with their principles, applications, and limitations.

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of VBNC Detection Methodologies

| Method Category | Specific Method | Principle | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopy-Based | Direct Viable Count (DVC) | Cell elongation in response to nutrients with nalidixic acid | Environmental samples, diverse bacterial species | Labor-intensive, requires expertise [1] |

| Live/Dead Staining (SYTO-9/PI) | Membrane integrity assessment | Pure cultures, biofilm studies | Cannot detect metabolic activity alone [1] | |

| CTC-DAPI Staining | Metabolic activity detection via tetrazolium reduction | Environmental microbiology | Variable reduction rates between species [1] | |

| Molecular Biology | PMA/EMA-qPCR | Selective DNA amplification from membrane-intact cells | Food safety, clinical diagnostics | Optimization required for different species [4] [6] |

| PMA-ddPCR | Absolute quantification without standard curves | Pathogen quantification in complex samples | Higher cost, specialized equipment [4] [7] | |

| RT-qPCR | Detection of gene expression as viability marker | Virulence potential assessment | RNA instability, requires careful handling [1] | |

| Advanced Techniques | ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy | Biomolecular fingerprinting through IR absorption | Mechanism studies, biomarker identification | Specialized equipment, data interpretation complexity [1] |

| Hyperspectral Microscopy | Spatial and spectral profiling with AI classification | Rapid detection, automated classification | High cost, developing methodology [8] | |

| Flow Cytometry | Multi-parameter cell analysis at single-cell level | Probiotic research, heterogeneous populations | Instrument standardization challenges [5] |

Emerging and Advanced Detection Technologies

Recent technological advances have introduced several powerful methods for VBNC detection that offer improved accuracy, sensitivity, and throughput:

PMA-ddPCR (Propidium Monoazide-droplet digital PCR): This method enables absolute quantification of VBNC cells without requiring external standard curves. The technique involves treating samples with PMA, which penetrates only membrane-compromised (dead) cells and intercalates with DNA, preventing its amplification. The sample is then partitioned into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets, with PCR amplification occurring in each droplet independently. This approach provides high precision for quantifying viable cells, even at low concentrations in complex matrices like fecal samples [4] [7]. Optimal PMA concentrations typically range between 5-200 μM, with incubation times of 5-30 minutes in the dark before light activation [4].

ATR-FTIR (Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared) Spectroscopy: This technique detects biomolecular changes in VBNC cells by measuring infrared absorption patterns that create a biochemical "fingerprint." Studies on E. coli W3110 in the VBNC state have revealed significant spectral differences, particularly showing increased RNA levels (notably at the 995 cmâ»Â¹ band) while protein and nucleic acid amounts decreased. The 995 cmâ»Â¹ RNA band has been identified as a consistent marker across multiple stress conditions, suggesting its potential as a robust biomarker for VBNC detection [1].

AI-Enabled Hyperspectral Microscopy Imaging: This innovative approach combines spatial and spectral data with deep learning algorithms for VBNC classification. In studies with E. coli K-12, this method achieved 97.1% accuracy in distinguishing VBNC cells from normal cells by using pseudo-RGB images generated from three characteristic spectral wavelengths, significantly outperforming traditional RGB image analysis (83.3% accuracy) [8].

Standardized Induction Protocols for VBNC State Research

Experimentally Validated Induction Conditions

The induction of the VBNC state varies significantly across bacterial species and depends on the specific stressor applied. Table 3 provides a comprehensive summary of optimized induction conditions for various bacterial species based on current research.

Table 3: Standardized VBNC Induction Conditions for Model Organisms

| Bacterial Species | Induction Stressor | Optimal Conditions | Time to VBNC | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Low-level chlorination | 0.5 mg/L chlorine, 6h exposure [3] | 6 hours | Live/Dead staining, plate count [3] |

| Temperature stress | 4°C in artificial seawater [1] | Days to weeks | Fluorescence microscopy, plate count [1] | |

| Antibiotic stress | Erythromycin exposure [1] | Species-dependent | ATR-FTIR, plate count [1] | |

| Heavy metal stress | Copper exposure [1] | Species-dependent | ATR-FTIR, plate count [1] | |

| K. pneumoniae | Low temperature | 4°C in artificial seawater [4] | ~50 days | PMA-ddPCR, plate count [4] |

| V. parahaemolyticus | High salt | High salt concentration [9] | Variable | Fatty acid analysis, membrane potential [9] |

| Surfactant + salt | 0.5-1.0% Lutensol A03 + 0.2M ammonium carbonate [6] | 1 hour | vqPCR, plate count [6] | |

| L. monocytogenes | Oxidative stress | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ (12,000 ppm) [10] | 10 minutes | Live/Dead staining, plate count [10] |

| Chlorine stress | Sodium hypochlorite (37.5 ppm), 20°C, 10min [10] | 10 minutes | Live/Dead staining, plate count [10] | |

| Acid stress | Potassium sorbate (pH 2.0) [10] | 30 minutes | Live/Dead staining, plate count [10] | |

| Probiotics (LAB) | Cold storage | 0-4°C in beer [5] | 6 months | Catalase supplementation, plate count [5] |

| Oxidative stress | Beer storage without catalase [5] | Months | Flow cytometry, catalase rescue [5] |

Protocol for VBNC Induction Using Low-Level Chlorination inE. coli

Based on established research methodologies, the following standardized protocol can be employed for inducing the VBNC state in E. coli using low-level chlorination:

- Culture Preparation: Grow E. coli to mid-logarithmic phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5-0.6) in appropriate liquid medium such as LB broth at 37°C with shaking.

- Cell Harvesting and Washing: Centrifuge culture at 5,000 × g for 10 minutes, discard supernatant, and resuspend pellet in sterile physiological saline or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Repeat washing step twice to remove residual organic matter.

- Chlorine Solution Preparation: Prepare a stock sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution and standardize concentration iodometrically. Dilute to working concentration in sterile, chlorine-demand-free water.

- Chlorine Exposure: Expose bacterial suspension (approximately 10⸠CFU/mL) to 0.5 mg/L chlorine at room temperature (20-25°C) for 6 hours. Maintain constant mixing during exposure.

- Chlorine Neutralization: After exposure, neutralize residual chlorine immediately with sodium thiosulfate (final concentration 0.1-0.5 mM).

- VBNC Confirmation: Verify induction success using:

- Plate Counts: Spread samples on non-selective agar before and after neutralization. No colonies should appear after 48h incubation.

- Live/Dead Staining: Use SYTO-9 and propidium iodide according to manufacturer instructions. VBNC cells should display green fluorescence (intact membranes).

- Metabolic Activity Assay: Perform CTC staining or ATP detection to confirm metabolic activity.

- Resuscitation Testing: Attempt resuscitation by inoculating neutralized samples into rich nutrient broth (e.g., LB) and monitoring for culturability recovery over 24-48 hours [3].

Molecular Characterization of the VBNC State

Genetic and Biomolecular Alterations

The transition to the VBNC state involves significant changes in gene expression and biomolecular composition, which serve as important markers for researchers:

- Transcriptional Reprogramming: Transcriptomic analyses of VBNC E. coli induced by low-level chlorination revealed upregulation of 16 genes, including those encoding fimbrial-like adhesin protein, putative periplasmic pilin chaperone, transcriptional regulators, antibiotic resistance genes, and stress-induced genes. Notably, three genes encoding toxic proteins (ygeG, ibsD, shoB) were significantly upregulated, indicating that VBNC cells may retain pathogenic potential [3].

- Biomolecular Profile Changes: ATR-FTIR spectroscopy studies have demonstrated consistent alterations in VBNC cells across different bacterial species, with a characteristic increase in RNA content (particularly noticeable at the 995 cmâ»Â¹ band) accompanied by decreases in protein and nucleic acid amounts [1].

- Cell Wall and Membrane Modifications: VBNC cells exhibit structural changes including increased peptidoglycan synthesis and cross-linking, alterations in outer membrane protein profiles (such as increased OmpW in E. coli), and changes in fatty acid composition, particularly increases in unsaturated fatty acids and shifts toward fatty acids with fewer carbon atoms [2] [3].

- Virulence Factor Retention: Numerous studies have confirmed that VBNC cells maintain expression of virulence genes, enabling them to retain pathogenic potential despite their non-culturable status. For example, Vibrio cholerae in the VBNC state upregulates genes associated with regulatory functions, cellular processes, energy metabolism, transport, and virulence [2].

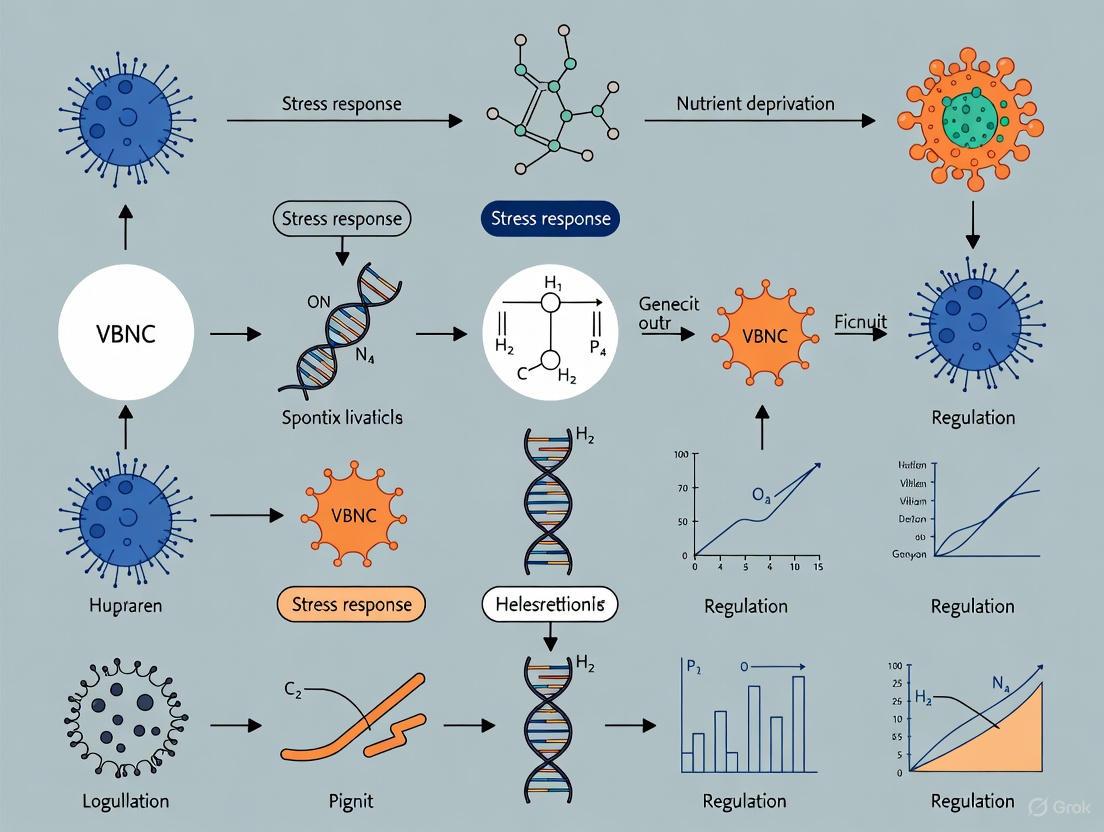

Visualization of VBNC State Transition and Detection

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for VBNC state induction, detection, and characterization, integrating the key methodologies discussed in this framework:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table compiles essential reagents and materials required for VBNC state research, based on methodologies cited in current literature:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for VBNC Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Examples | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | Selective DNA intercalation in membrane-compromised cells | PMA-qPCR, PMA-ddPCR for viable cell detection | Optimize concentration (5-200 μM) and incubation time [4] |

| SYTO-9/Propidium Iodide | Dual staining for membrane integrity assessment | Live/Dead staining, fluorescence microscopy | Green (live) vs red (dead) fluorescence differentiation [1] |

| CTC (5-cyano-2,3-di-(p-tolyl) tetrazolium chloride) | Metabolic activity indicator via electron transport system | CTC-DAPI staining for metabolic activity | Forms fluorescent formazan upon reduction [1] |

| Catalase | Oxidative stress relief by breaking down Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Resuscitation of VBNC LAB from beer | Use at 1000 IU/mL in recovery media [5] |

| Sodium Thiosulfate | Chlorine neutralization in disinfection studies | Chlorine stress induction protocols | Critical for stopping chlorine action at precise time points [3] |

| Nalidixic Acid | DNA gyrase inhibitor for cell elongation prevention | Direct Viable Count (DVC) method | Allows nutrient response without cell division [1] |

| Chlorine Compounds | VBNC induction through oxidative stress | Sodium hypochlorite, calcium hypochlorite | Standardize concentration; use chlorine-demand-free water [10] |

| Artificial Seawater (ASW) | Simulation of natural aquatic environments | VBNC induction in marine bacteria | 40 g/L sea salt, 0.22-μm filter sterilization [4] |

| 2-Hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone | 2-Hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone, CAS:2474-72-8, MF:C6H4O3, MW:124.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2,4,5-Trichlorophenetole | 2,4,5-Trichlorophenetole, CAS:6851-44-1, MF:C8H7Cl3O, MW:225.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

This standardized framework establishes essential protocols and methodologies for VBNC state research, providing researchers with validated tools for induction, detection, and characterization of this complex physiological state. The integration of classical microbiological approaches with advanced molecular techniques and innovative technologies like AI-enabled hyperspectral imaging represents the future of VBNC research, offering more accurate, reliable, and standardized approaches to studying this challenging bacterial survival strategy.

As research in this field continues to evolve, several areas require further development: standardized reference materials for method validation, interlaboratory proficiency testing, and the establishment of method-specific acceptance criteria. By adopting this framework, researchers can contribute to a more unified understanding of the VBNC state, ultimately leading to improved detection and control strategies for dormant bacterial pathogens across clinical, industrial, and environmental settings.

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state represents a sophisticated survival strategy adopted by numerous bacterial species when confronted with adverse environmental conditions. In this state, bacteria lose the ability to form colonies on routine culture media while maintaining metabolic activity and viability, presenting significant challenges for public health, food safety, and clinical diagnostics. This comprehensive review synthesizes current understanding of the key physiological inducers that trigger the VBNC state, examining mechanisms from molecular to systems levels. We characterize the diverse environmental stressors—including nutrient starvation, temperature shifts, chemical disinfectants, and osmotic challenges—that initiate this programmed dormancy response. The molecular underpinnings of VBNC induction are explored through recent transcriptomic and mechanistic studies, revealing conserved pathways across bacterial species. Additionally, we detail advanced methodological frameworks for detecting and quantifying VBNC cells, highlighting both limitations and innovations in current technologies. This analysis aims to provide researchers with a foundational resource for investigating VBNC physiology and developing novel approaches to address the challenges posed by this elusive bacterial state.

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state was first identified in 1982 in Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae [11] and has since been recognized as a widespread survival strategy among diverse bacterial species. When entering the VBNC state, bacteria undergo a programmed physiological transformation that renders them incapable of proliferation on standard laboratory media while maintaining metabolic activity, membrane integrity, and potential pathogenicity [11] [12]. This state allows bacteria to withstand potentially lethal environmental insults, including those imposed by antimicrobial treatments, making the VBNC state a significant concern in clinical medicine, food safety, and public health.

To date, more than 100 bacterial species have been demonstrated to enter the VBNC state, including significant human pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Helicobacter pylori, Legionella pneumophila, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella typhimurium, Vibrio cholerae, Yersinia pestis, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis [11]. The ability to assume a VBNC state appears to be phylogenetically widespread, occurring in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria alike, though with important differences in induction mechanisms and responsiveness to specific environmental signals [13].

Within the broader context of VBNC research, understanding the physiological inducers that trigger this state is paramount. These inducers represent specific environmental cues or stress conditions that activate the genetic and metabolic reprogramming necessary for transition into the VBNC state. Elucidating these triggers and their mechanisms of action provides critical insights into bacterial survival strategies while informing more effective approaches for microbial control and detection across diverse settings.

Major Inducer Categories and Their Mechanisms

Bacteria enter the VBNC state through exposure to diverse environmental stressors that can be broadly categorized into physical, chemical, and biological inducers. The following sections provide a comprehensive analysis of these inducer categories, their physiological effects, and their prevalence across bacterial species.

Physical Stressors

Physical stressors encompass changes in environmental conditions that directly impact cellular structures and metabolic processes.

Temperature stress represents one of the most thoroughly characterized inducers of the VBNC state. Both low and high temperature extremes can trigger the transition, though low temperatures are particularly effective. E. coli O157:H7 enters the VBNC state when exposed to both refrigeration temperatures (+4°C) and freezing conditions (-20°C) [11]. Similarly, V. vulnificus rapidly transitions to the VBNC state in artificial seawater at low temperatures [11]. The mechanisms underlying cold-induced VBNC formation involve reduced enzymatic activity, membrane fluidity changes, and altered gene expression patterns that collectively promote metabolic downregulation.

UV radiation represents another significant physical inducer of the VBNC state. Exposure to UV light causes DNA damage and oxidative stress, triggering cellular responses that can lead to VBNC transition rather than cell death [11]. Bacteria employ various DNA repair mechanisms initially, but prolonged or intense UV exposure often shifts the response toward dormancy as a survival strategy. Sunlight exposure has been demonstrated to induce the VBNC state in environmental bacteria, with specific wavelengths within the UV spectrum being particularly effective [11].

Additional physical inducers include aerosolization [11], drying [11], and pressure changes [11], though these have been less extensively characterized than temperature and radiation effects.

Chemical Stressors

Chemical stressors comprise a diverse array of compounds and solutions that disrupt cellular homeostasis, ultimately triggering the VBNC state.

Oxidizing disinfectants, particularly chlorine, represent well-documented inducers of the VBNC state in water systems and food processing environments. Low-dose chlorination (0.5 mg/L) effectively induces VBNC state in E. coli while enhancing bacterial tolerance to multiple antibiotics [12]. Chlorine exposure causes oxidative damage to cellular components and increases membrane permeability, as demonstrated by flow cytometry analysis showing that 98.44% of VBNC E. coli cells exhibited enhanced membrane permeability after chlorine treatment [12]. Transcriptomic analyses reveal that chlorine-induced VBNC cells upregulate genes related to fimbrial-like adhesin proteins, periplasmic pilin chaperones, transcriptional regulators, antibiotic resistance genes, and stress-induced genes [12].

Heavy metals such as copper, mercury, and cadmium can induce the VBNC state at sublethal concentrations [11]. These metals generate oxidative stress and disrupt essential enzymatic functions, prompting bacteria to enter protective dormancy. The induction typically occurs over extended exposure periods, with concentration-dependent effects on the rate and extent of VBNC transition.

Household cleaners and surfactants have recently been identified as potent inducers of the VBNC state, particularly when combined with inorganic salts. A comprehensive screening of 630 surfactant/salt combinations demonstrated that non-ionic surfactants can induce VBNC state in L. monocytogenes, E. coli, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, S. aureus, and toxin-producing enteropathogenic E. coli [13]. The effectiveness correlated with surfactant hydrophobicity, as measured by the hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB), with Gram-positive bacteria showing greater susceptibility to VBNC induction than Gram-negative species [13].

Food preservatives and organic pollutants also serve as chemical inducers of the VBNC state [11]. These compounds typically disrupt membrane integrity or interfere with specific metabolic pathways, initiating the transition to dormancy.

Biological Stressors

Biological stressors encompass nutrient-based challenges and competition-related signals that promote VBNC transition.

Nutrient starvation represents perhaps the most fundamental biological inducer of the VBNC state. Multiple bacterial species, including E. coli [11], Shigella dysenteriae [11], V. parahaemolyticus [11], Aeromonas hydrophila [11], and Klebsiella pneumoniae [11], enter the VBNC state under starvation conditions. Carbon source limitation appears particularly effective in triggering this transition, though combined nutrient deficiencies often produce more rapid induction. Starvation triggers comprehensive metabolic restructuring, with downregulation of biosynthetic pathways and energy conservation becoming prioritized.

Osmotic stress, induced by both high and low salinity environments, can initiate VBNC transition [11]. Osmotic imbalances cause water flux across cell membranes, potentially leading to plasmolysis or cell rupture unless compensatory mechanisms are activated. For some bacteria, entry into the VBNC state represents an adaptive response to extreme osmotic conditions, particularly when changes occur rapidly.

pH extremes both acidic and alkaline conditions can induce the VBNC state [11]. S. aureus cells treated with citric acid under low-temperature conditions entered the VBNC state within 18 days [11]. pH stress affects cellular enzyme activity and membrane stability, triggering protective responses that can include transition to the VBNC state.

Table 1: Major Inducers of the VBNC State and Their Characteristics

| Inducer Category | Specific Examples | Representative Affected Species | Typical Exposure Conditions | Primary Cellular Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Stressors | Low temperature (+4°C to -20°C) | E. coli, V. vulnificus | Days to weeks | Membrane fluidity, enzyme activity |

| UV radiation | Multiple species | Minutes to hours | DNA integrity, oxidative stress | |

| Thermosonication | Multiple species | Minutes | Membrane integrity, protein denaturation | |

| Chemical Stressors | Chlorine (0.5 mg/L) | E. coli, L. monocytogenes | Minutes to hours | Membrane permeability, oxidative damage |

| Heavy metals (Cu, Hg, Cd) | Multiple species | Hours to days | Enzyme function, oxidative stress | |

| Surfactant+salt combinations | L. monocytogenes, S. aureus | 5 minutes to 1 hour | Membrane integrity, efflux pumps | |

| Organic pollutants | Multiple species | Hours to days | Metabolic pathways, membrane integrity | |

| Biological Stressors | Nutrient starvation | E. coli, K. pneumoniae | Days to weeks | Metabolic regulation, energy conservation |

| Osmotic stress | Multiple species | Hours to days | Membrane stability, water balance | |

| pH extremes | S. aureus, E. coli | Hours to days | Enzyme activity, membrane stability |

Experimental Models and Methodological Approaches

Studying the VBNC state requires specialized methodological approaches that overcome the fundamental limitation of non-culturability on standard media. This section details established protocols for inducing, detecting, and analyzing the VBNC state in laboratory settings.

Induction Protocols

Chlorine-Induced VBNC State in E. coli

To induce VBNC state using chlorine treatment [12]:

- Grow E. coli cultures to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5) in appropriate medium.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (2,500 × g, 5 min) and resuspend in sterile water or minimal medium.

- Add sodium hypochlorite to achieve final concentration of 0.5 mg/L free chlorine.

- Incubate for 6 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Confirm VBNC state by assessing culturability on standard media (absence of growth) while verifying membrane integrity and metabolic activity (see detection methods below).

- Quench residual chlorine with 0.3 M sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate before further analysis.

Surfactant/Salt-Induced VBNC State in Multiple Pathogens

For rapid VBNC induction using surfactant/salt combinations [13]:

- Prepare bacterial cultures to approximately 10^9 CFU/mL in appropriate growth medium.

- Centrifuge cultures and resuspend in solutions containing combinations of non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Lutensol XP30) and inorganic salts (e.g., MgClâ‚‚).

- Exposure times can vary from 5 minutes to 1 hour at room temperature.

- Remove combinational stress by washing and resuspending in fresh growth medium.

- Assess VBNC state through multiple viability assays (see below).

Starvation-Induced VBNC State

For nutrient starvation induction [11]:

- Grow bacteria to stationary phase in nutrient-rich medium.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and wash with sterile saline or buffer.

- Resuspend in minimal medium without carbon sources or in natural oligotrophic environments like artificial seawater or tap water.

- Incubate for extended periods (days to weeks) at appropriate temperatures.

- Monitor transition to VBNC state regularly using viability assays.

Detection and Validation Methods

Direct Viable Count (DVC)

The DVC method represents one of the earliest approaches for detecting VBNC cells [11]:

- Incubate samples with nutrients (e.g., yeast extract) and DNA synthesis inhibitors (e.g., nalidixic acid, aztreonam, or ciprofloxacin).

- Stain with acridine orange and examine by fluorescence microscopy.

- Viable cells enlarge due to metabolic activity without dividing, appearing as elongated fluorescent cells, while dead cells remain small.

- This method distinguishes living cells but cannot differentiate between culturable and VBNC states alone.

Membrane Integrity Assays

The LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit is widely used [11] [13]:

- Combine SYTO 9 and propidium iodide (PI) stains according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Incubate bacterial suspensions with stain mixture for 15-30 minutes in the dark.

- Examine by fluorescence microscopy or analyze by flow cytometry.

- Cells with intact membranes fluoresce green (SYTO 9), while those with compromised membranes fluoresce red (PI).

- VBNC cells typically show green fluorescence, indicating membrane integrity.

Metabolic Activity Assays

5-Cyano-2,3-Ditolyl Tetrazolium Chloride (CTC) reduction assay [11]:

- Add CTC to samples to final concentration of 2-5 mM.

- Incubate for 1-4 hours in the dark.

- Examine by epifluorescence microscopy with green excitation.

- Metabolically active cells reduce CTC to red-fluorescent formazan deposits.

ATP measurement [13]:

- Extract ATP from bacterial samples using appropriate reagents.

- Measure ATP content using luciferin-luciferase bioluminescence assays.

- Compare ATP levels with positive and negative controls.

Viability Quantitative PCR (v-qPCR)

v-qPCR combined with photoactive dyes enables molecular detection of VBNC cells [14]:

- Treat samples with EMA (10 μM) and PMAxx (75 μM).

- Incubate at 40°C for 40 minutes followed by 15-minute light exposure using a photoactivation device.

- Extract DNA according to standard protocols.

- Perform qPCR with species-specific primers and probes.

- The dyes penetrate only cells with compromised membranes, binding to DNA and inhibiting PCR amplification, thus selectively detecting intact cells.

Flow Cytometry

Multiparameter flow cytometry provides high-throughput analysis [14]:

- Stain bacterial suspensions with appropriate fluorescent dyes (e.g., SYTO 9/PI combination).

- Analyze using flow cytometer with appropriate laser and filter settings.

- Establish gates based on positive and negative controls.

- VBNC cells typically show intact membrane characteristics with reduced metabolic markers compared to culturable cells.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for VBNC State Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in VBNC Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Stains | SYTO 9/PI (LIVE/DEAD BacLight) | Membrane integrity assessment | Must be combined with culturability assays to distinguish VBNC |

| CTC, INT | Metabolic activity measurement | Can detect electron transport system activity in VBNC cells | |

| EMA, PMA, PMAxx | Selective DNA amplification inhibition in dead cells | Critical for v-qPCR; requires optimization for different bacterial species and matrices | |

| Induction Agents | Sodium hypochlorite | Chemical inducer of VBNC state | 0.5 mg/L concentration effective for E. coli [12] |

| Non-ionic surfactants (Lutensol series) | VBNC induction when combined with salts | Effectiveness correlates with HLB value [13] | |

| Inorganic salts (MgClâ‚‚, carbonates) | Enhancement of surfactant activity | Specific salt effects vary between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria | |

| Molecular Assay Components | Luciferin-luciferase | ATP measurement | Sensitivity allows detection of low metabolic activity in VBNC cells |

| Species-specific primers/probes | Detection and quantification in v-qPCR | Enables specific identification of VBNC pathogens in complex samples | |

| Culture Media | Nutrient-deficient media | Starvation-induced VBNC state | Artificial seawater, tap water, or minimal media without carbon sources |

Molecular Mechanisms and Systems-Level Adaptations

The transition to the VBNC state involves complex molecular reprogramming that varies according to the inducing stimulus and bacterial species. Recent transcriptomic and mechanistic studies have revealed both conserved and specialized pathways activated during VBNC induction.

Transcriptional Reprogramming

Global gene expression analyses provide insights into the systematic changes underlying VBNC formation. RNA-seq analysis of VBNC E. coli induced by low-level chlorination revealed significant upregulation of 16 genes, including those encoding toxic proteins (ygeG, ibsD, shoB), indicating that VBNC cells may maintain pathogenic potential [12]. These cells also showed altered expression of genes related to fimbrial-like adhesin proteins, periplasmic pilin chaperones, transcriptional regulators, antibiotic resistance genes, and stress response elements [12].

In Bacillus subtilis, transcriptome analysis of VBNC cells induced by osmotic stress and kanamycin treatment revealed 334 upregulated and 514 downregulated genes compared to untreated cells [15]. Notably, VBNC cells strongly upregulated genes involved in proline uptake and catabolism, suggesting a putative role of proline as a nutrient source in VBNC cells [15]. Additionally, VBNC B. subtilis showed significant upregulation of the ICEBs1 conjugative element genes, typically induced by DNA damage and SOS response, indicating antibiotic-induced oxidative stress [15].

The queuosine biosynthesis pathway, particularly the queC-queD-queE-queF operon, was also upregulated in VBNC B. subtilis [15]. Queuosine modification of tRNAs helps minimize translation errors, potentially conferring kanamycin-tolerant phenotypes by reducing protein misfolding.

Metabolic Restructuring

VBNC cells undergo substantial metabolic reprogramming to conserve energy and maintain essential functions during dormancy. Central carbohydrate metabolic pathways are typically altered to optimize energy production under nutrient-limited conditions [12]. ATP levels are maintained, though at reduced levels compared to growing cells, supporting continued metabolic activity despite non-culturability [15].

The upregulation of proline catabolic genes in VBNC B. subtilis suggests alternative nutrient utilization strategies in the dormant state [15]. This metabolic flexibility may contribute to the remarkable persistence of VBNC cells under adverse conditions.

Stress Response Activation

Canonical stress response pathways feature prominently in VBNC induction and maintenance. Oxidative stress responses are particularly significant, as many VBNC inducers (including chlorine, antibiotics, and heavy metals) generate reactive oxygen species [11] [15]. Genes encoding detoxification enzymes and redox homeostasis proteins are commonly upregulated in VBNC cells.

The SOS response to DNA damage is another conserved element in VBNC induction, evidenced by upregulation of ICEBs1 elements in B. subtilis [15] and DNA repair systems in other species. This response may represent both a reaction to inducing stresses and a programmed aspect of the VBNC transition.

Diagram 1: Integrated Pathway of VBNC State Induction. This diagram illustrates the sequential progression from environmental stressors through cellular effects and molecular responses to the establishment of the VBNC state.

Research Implications and Future Directions

The ubiquitous nature of VBNC inducers across environmental, industrial, and clinical settings necessitates continued research into this persistent physiological state. Several critical areas demand focused investigation to address fundamental questions and practical challenges.

Detection and Diagnostic Challenges

Current growth-based detection methods routinely fail to identify VBNC pathogens, creating significant gaps in microbial risk assessment [13] [14]. This limitation is particularly problematic in clinical settings, where VBNC pathogens may contribute to persistent or recurrent infections that evade standard diagnostic approaches. Similarly, in food safety systems, the inability to detect VBNC cells compromises the effectiveness of microbial monitoring programs [11] [14].

Advanced detection technologies that combine molecular methods with viability indicators offer promising alternatives. The optimized v-qPCR protocol combining EMA and PMAxx provides reliable detection of VBNC Listeria monocytogenes in process wash water from fresh-cut produce facilities [14]. Similar approaches require validation across diverse bacterial species and sample matrices to establish standardized detection frameworks.

Flow cytometry, while powerful for laboratory studies, shows limitations in complex environmental samples due to interference from particulate matter and other matrix effects [14]. Method refinement for specific applications remains an ongoing research priority.

Therapeutic and Public Health Considerations

The enhanced antibiotic tolerance of VBNC cells presents serious clinical challenges [12] [15]. VBNC E. coli induced by low-level chlorination exhibits significantly increased tolerance to multiple antibiotics, including ampicillin and ofloxacin at concentrations far exceeding typical minimum inhibitory concentrations [12]. This tolerance likely contributes to treatment failures and persistent infections.

The maintained virulence potential of VBNC cells further complicates risk assessment. Transcriptomic analyses confirm that VBNC pathogens continue to express toxin genes and virulence factors [12] [13]. Some VBNC pathogens, including enteropathogenic E. coli and L. pneumophilia, maintain pathogenicity even without resuscitation, potentially through toxin production or other virulence mechanisms [13].

These findings necessitate reconsideration of sterilization and disinfection protocols across healthcare, food production, and water treatment facilities. Standard approaches that fail to account for VBNC induction may inadvertently select for dormant, persistent bacterial populations with enhanced resistance characteristics.

Future Research Priorities

Several critical knowledge gaps require attention in VBNC research:

- Resuscitation Mechanisms: The signals and processes that trigger VBNC cells to return to cultivability remain poorly understood across most bacterial species. Elucidating these mechanisms is essential for predicting and controlling resuscitation events.

- Evolutionary Ecology: The role of the VBNC state in bacterial evolution and ecology warrants further investigation, particularly regarding its contribution to antibiotic resistance development and persistence in environmental reservoirs.

- Therapeutic Interventions: Strategies specifically targeting VBNC cells, either through prevention of VBNC induction, direct killing of VBNC cells, or blockade of resuscitation, represent promising therapeutic avenues.

- Standardization: Development of standardized methodologies for VBNC induction, detection, and quantification across research laboratories would significantly enhance data comparability and research progress.

The transition to the VBNC state represents a complex physiological adaptation to environmental stress, with induction occurring through diverse physical, chemical, and biological triggers. From nutrient starvation to antimicrobial stress, these inducers activate conserved molecular pathways that reprogram bacterial physiology toward a dormant yet viable state. The significant challenges posed by VBNC cells in clinical, industrial, and environmental contexts underscore the importance of continued research into their induction mechanisms, detection methods, and control strategies. As methodological advances enable more sophisticated investigation of this elusive bacterial state, new opportunities emerge for addressing the persistent public health challenges associated with VBNC pathogens.

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state is a unique survival strategy adopted by many bacteria in response to adverse environmental conditions [16]. In this state, bacteria maintain viability and metabolic activity but lose the ability to form colonies on conventional culture media routinely used for their detection [17] [16]. This phenomenon has profound implications across multiple fields, including clinical microbiology, food safety, and public health, as VBNC pathogens can evade standard diagnostic methods while retaining pathogenic potential [18] [16].

Understanding the cellular and molecular transformations associated with the VBNC state is crucial for developing detection methods and control strategies. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the morphological and biochemical hallmarks of this physiological state, providing researchers with a comprehensive technical reference for investigating this bacterial survival mechanism.

Morphological Transformations in the VBNC State

Cellular Structure and Physical Characteristics

When bacteria transition to the VBNC state, they undergo significant morphological changes that enhance their survival under stressful conditions. A consistent observation across multiple species is a marked reduction in cell size. VBNC cells become significantly smaller and typically adopt a coccoid shape, as documented in diverse organisms including Vibrio cholerae, Helicobacter pylori, and various Shewanella species [16] [2]. This size reduction represents an adaptive strategy to minimize energy requirements and surface area exposed to environmental stressors.

The structural changes extend to cellular components, with notable alterations in membrane composition and rigidity. Studies on Vibrio vulnificus have demonstrated increased levels and structural modifications in unsaturated fatty acids during VBNC transition, including a significant shift toward fatty acids with fewer than 16 carbon atoms and elevated levels of octadecanoic and hexadecanoic acids [2]. Similarly, Enterococcus faecalis in the VBNC state exhibits higher levels of peptidoglycan crosslinking compared to cultivable cells, potentially contributing to enhanced structural integrity and resistance [2].

Table 1: Documented Morphological Changes in Selected Bacterial Species in the VBNC State

| Bacterial Species | Inducing Condition | Morphological Changes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vibrio cholerae | Incubation at 4°C for 60 days | Transformation to coccoid cells | [16] |

| Helicobacter pylori | 7 days of incubation | Transformation to coccoid form | [16] |

| Shewanella xiamenensis JL2 | Cu²⺠stress (0.25 mM) | Cell size reduction | [17] |

| Vibrio vulnificus | Low temperature | Increased unsaturated fatty acids; Shift to shorter chain fatty acids | [2] |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Stress conditions | Increased peptidoglycan crosslinking | [2] |

| Escherichia coli | Stress conditions | Increased OmpW levels | [2] |

Ultrastructural Adaptations

At the subcellular level, VBNC cells exhibit substantial reorganization of their internal architecture. Transmission electron microscopy studies have revealed cytoplasmic condensation and reduction of intracellular spaces, consistent with a transition to a metabolically downregulated state. These ultrastructural modifications contribute to the remarkable resilience of VBNC cells, allowing them to persist under conditions that would eliminate their culturable counterparts.

The cell envelope undergoes significant modification, with changes in both membrane fluidity and protein composition. In Escherichia coli, alterations in outer membrane protein (Omp) patterns have been observed, with OmpW showing a marked increase during the VBNC state [2]. These modifications likely contribute to enhanced barrier function and stress resistance while potentially affecting nutrient transport and environmental sensing capabilities.

Biochemical and Metabolic Reprogramming

Oxidative Stress Management

A defining feature of the VBNC state is the sophisticated biochemical reprogramming that enables survival under adverse conditions. A central mechanism driving VBNC formation is the synergistic effect of oxidative stress and stringent response [17]. When facing environmental challenges, bacteria activate comprehensive antioxidant defense systems involving enzymes such as AhpCF, SodA, and KatGB to counter reactive oxygen species (ROS) [17].

The stringent response triggers extensive transcriptional reprogramming, prioritizing survival over growth by repressing ribosomal biogenesis while enhancing transcription of stress-responsive genes [17]. This reallocation of cellular resources is fundamental to the VBNC transition. Research on Shewanella xiamenensis JL2 under Cu²⺠stress has revealed a previously uncharacterized antioxidant role of the ohr gene in VBNC cells, highlighting the complexity of oxidative stress management in this state [17].

Figure 1: Oxidative Stress and Stringent Response in VBNC Induction. This diagram illustrates the coordinated signaling pathways that drive bacterial entry into the VBNC state in response to environmental stress.

Metabolic Pathway Alterations

VBNC cells undergo profound metabolic restructuring to conserve energy and maintain essential functions. Carbon metabolism exhibits particularly significant adaptations. While activation of the glyoxylate cycle (GC) has been reported as a conserved carbon utilization strategy in some VBNC cells [17], recent research on Shewanella xiamenensis JL2 reveals an alternative strategy under Cu²⺠stress. Instead of employing the GC pathway, these cells activate the methylcitrate cycle (MCC), demonstrating species-specific and stressor-dependent variations in metabolic adaptation [17].

Energy metabolism is markedly downregulated, with studies showing reduced intracellular ATP concentrations and decreased activity of key respiratory enzymes like succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in VBNC cells of Yersinia enterocolitica induced by lactic acid stress [19]. This metabolic depression aligns with the overall survival strategy of minimizing energy consumption while maintaining basal metabolic activity sufficient for cellular integrity.

Table 2: Key Metabolic Changes in the VBNC State

| Metabolic Parameter | Change in VBNC State | Functional Significance | Example Organism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Metabolism | Shift to alternative pathways (GC or MCC) | Bypass COâ‚‚-producing steps, conserve energy | Shewanella xiamenensis [17] |

| ATP Concentration | Marked decrease | Reduced energy metabolism | Yersinia enterocolitica [19] |

| Succinate Dehydrogenase Activity | Decreased | Reduced respiratory activity | Yersinia enterocolitica [19] |

| Respiratory Chain Components | Differential regulation of terminal oxidases | Optimization under stress | Shewanella xiamenensis [17] |

| Gluconeogenesis-related Proteins | Up-regulation | Maintenance of essential metabolites | Vibrio parahaemolyticus [16] |

Gene Expression and Protein Profile Modifications

The transition to the VBNC state involves extensive reprogramming of gene expression and protein synthesis. Proteomic analyses reveal downregulation of ribosomal proteins and translation factors, consistent with the growth arrest characteristic of this state [17]. In Shewanella xiamenensis JL2, genes encoding ribosomal proteins L1, L2, L4, L5, S1, S2, S7, S12, and S13 were significantly downregulated under Cu²⺠stress [17].

Conversely, stress response proteins show increased expression. Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the VBNC state upregulates proteins associated with transcription, translation, ATP synthase, gluconeogenesis-related metabolism, and antioxidants including homologs of peroxiredoxins and the AhpC/Tsa family [16]. Vibrio vulnificus similarly highly expresses glutathione S-transferase, enhancing its antioxidant capacity [16].

The protein profile of Helicobacter pylori in the VBNC state shows increased alkaline phosphatase but reduced urease, leucine arylamidase, and naphthol-AS-beta-1-phosphohydrolase [16]. These enzymatic changes reflect the metabolic reorientation necessary for persistence under nutrient limitation and other stressful conditions.

Experimental Methodologies for VBNC Research

Induction of the VBNC State

Establishing reliable protocols for inducing the VBNC state is fundamental to its study. Multiple induction methods have been successfully employed across different bacterial species, with the specific approach depending on the research objectives and bacterial strain under investigation.

Chemical induction represents one of the most common approaches. For example, in Shewanella xiamenensis JL2, the VBNC state can be induced using wastewater-relevant concentrations of Cu²⺠(0.0625-0.25 mM) [17]. The experimental protocol involves culturing the strain in LB broth or on LB agar plates, followed by exposure to the metal stressor while monitoring the loss of culturability over time [17]. Similarly, Yersinia enterocolitica can be induced into the VBNC state using lactic acid at concentrations of 1-4 mg/mL, with complete loss of culturability occurring within 10-60 minutes depending on concentration [19].

Antibiotic pressure combined with nutrient starvation provides another effective induction method. For staphylococcal strains, incubation in low-nutrient M9 medium with gentamycin at 4-16× MIC successfully induced the VBNC state within 8-19 days [18]. The protocol involves initial biofilm formation on filter paper membranes during 48h incubation on BHI agar plates supplemented with 1% glucose, followed by transfer to the induction medium [18].

Physical methods have also been established, particularly for foodborne pathogens. For Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio cholerae, treatment with a solution containing 0.5-1.0% Lutensol A03 and 0.2 M ammonium carbonate induced the VBNC state within approximately one hour [6]. This rapid induction protocol facilitates the generation of VBNC cells for method validation and downstream applications.

Detection and Confirmation Methods

Accurately detecting and confirming the VBNC state requires a combination of approaches that assess culturability, membrane integrity, and metabolic activity.

Culturability assessment forms the baseline measurement, typically performed by monitoring the disappearance of colony-forming units (CFUs) on standard culture media. This represents the defining characteristic of VBNC cells—their inability to grow on routine media despite maintaining viability [18] [19].

Membrane integrity assays provide crucial evidence of viability. The LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit is widely employed, utilizing a mixture of SYTO 9 and propidium iodide (PI) stains. SYTO 9 penetrates all bacteria, staining them green, while PI only penetrates bacteria with damaged membranes, staining them red and reducing green fluorescence [18]. This allows differentiation between viable cells (green fluorescence) and dead cells (red fluorescence), with VBNC cells typically showing green fluorescence despite non-culturability [18]. Fluorescence microscopy or spectrophotometric measurement of emitted fluorescence enables quantification.

Metabolic activity measurements offer additional confirmation of viability. The 5-cyano-2,3-xylyltetrazolium chloride (CTC) assay measures respiratory activity, where CTC is reduced to insoluble, fluorescent formazan crystals in respiring cells [17]. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) quantification using commercial assay kits provides another sensitive indicator of metabolic activity, with detectable ATP levels persisting in VBNC cells despite significant reduction compared to culturable cells [19].

Molecular detection methods have been developed to overcome limitations of culture-based approaches. Viability quantitative PCR (v-qPCR) combines DNA intercalating dyes like propidium monoazide (PMA) or ethidium monoazide (EMA) with PCR amplification [6] [14]. These dyes penetrate membrane-compromised cells and bind covalently to DNA upon photoactivation, preventing its amplification. This approach selectively amplifies DNA from viable cells (including VBNC) while excluding DNA from dead cells [6]. For complex matrices like process wash water, a combination of 10 μM EMA and 75 μM PMAxx incubated at 40°C for 40 minutes followed by a 15-minute light exposure has been shown to effectively inhibit qPCR amplification from dead cells while allowing detection of VBNC cells [14].

Figure 2: VBNC State Confirmation Workflow. This diagram outlines the logical process for confirming the VBNC state, requiring both loss of culturability and evidence of viability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for VBNC State Studies

| Reagent/Method | Specific Example | Function in VBNC Research | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Stains | LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit | Differentiates cells with intact (green) vs. damaged (red) membranes | [18] |

| Metabolic Activity Probes | 5-cyano-2,3-xylyltetrazolium chloride (CTC) | Measures respiratory activity via reduction to fluorescent formazan | [17] |

| ATP Assay Kits | Commercial ATP quantification kits | Measures metabolic activity via ATP concentration | [17] [19] |

| DNA Intercalating Dyes | PMA, PMAxx, EMA | Selectively inhibits PCR amplification from dead cells in v-qPCR | [6] [14] |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) assay kits | Measures activity of key metabolic enzymes | [17] [19] |

| ROS Detection Kits | Commercial ROS assay kits | Quantifies reactive oxygen species levels | [17] |

| Antioxidant Assay Kits | SOD, POD, CAT assay kits | Measures antioxidant enzyme activities | [17] |

| 3-fluoro-2-methyl-1H-indole | 3-Fluoro-2-methyl-1H-indole|High-Quality Research Chemical | 3-Fluoro-2-methyl-1H-indole for research use only (RUO). Explore its applications in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 3-Indolizinecarboxamide | 3-Indolizinecarboxamide|CAS 22320-27-0|Supplier | High-purity 3-Indolizinecarboxamide (CAS 22320-27-0) for pharmaceutical and chemical research. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The morphological and biochemical transformations characterizing the VBNC state have significant implications for multiple research domains. In clinical microbiology, the inability to culture VBNC pathogens using conventional methods complicates diagnosis and treatment, potentially leading to false-negative results and unresolved infections [18] [16]. In food safety, VBNC pathogens pose an undetected hazard, as they may resuscitate during food storage or after consumption, regaining virulence and causing disease [19].

Future research priorities include developing more reliable detection methods that can be standardized across different bacterial species and matrices. Additionally, elucidating the precise molecular triggers for resuscitation remains a critical challenge, with potential applications in controlling persistent infections and improving food safety. The discovery of resuscitation-promoting factors (Rpf) in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms represents a promising avenue for understanding the molecular mechanisms governing the exit from the VBNC state [16].

Understanding the cellular and molecular hallmarks of the VBNC state provides researchers with essential knowledge for investigating this survival mechanism across different bacterial species and environments. The experimental methodologies outlined here offer a foundation for standardized approaches to inducing, detecting, and characterizing this physiologically distinct state, facilitating more comprehensive studies of its significance in both natural and clinical settings.

In response to environmental stress, numerous bacterial species can enter reversible states of metabolic dormancy, a survival strategy that poses significant challenges in clinical medicine and industrial microbiology. Within this context, three distinct dormant forms—Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) cells, persister cells, and spores—represent a spectrum of survival strategies with unique physiological and molecular characteristics [20] [21]. The study of these states is crucial for understanding bacterial pathogenesis, antibiotic treatment failure, and microbial ecology.

The VBNC state represents a survival mechanism wherein bacteria lose their ability to grow on conventional culture media yet maintain metabolic activity and can resuscitate under favorable conditions [20] [1]. This state is characterized by the loss of culturability, maintenance of viability, and resuscitation capacity, allowing cells to withstand a wide range of moderate to long-term stress conditions commonly found in environmental, food industry, and occasional clinical settings [20]. The molecular mechanisms underlying the VBNC state remain perplexing yet represent a critical adaptation to suboptimal conditions.

Persister cells, in contrast, are growth-arrested subpopulations that exhibit transient, non-heritable antibiotic tolerance without genetic modification [22] [23]. These phenotypic variants can survive lethal environments and revert to wild-type physiology after stress removal, playing a key role in antibiotic therapy failure and chronic, recurrent infections [22]. Unlike resistant bacteria that rely on mutations, persisters represent a bet-hedging strategy that maintains population heterogeneity in fluctuating environments.

Bacterial spores, particularly in Bacillus and Clostridium species, represent the most highly differentiated dormant state, characterized by metabolic dormancy and extreme resistance to environmental stresses [24] [25]. Spore formation involves a complex developmental process resulting in a specialized cellular structure that can remain dormant for years yet rapidly return to vegetative growth through germination when nutrients become available [24].

This review examines the physiological basis for VBNC state induction research by systematically differentiating these three dormancy states through their defining characteristics, molecular mechanisms, detection methodologies, and resuscitation behaviors.

Defining Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

The differentiation between VBNC cells, persister cells, and spores requires understanding of their distinct physiological states, formation triggers, and functional capabilities. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these dormancy states:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Dormancy States

| Characteristic | VBNC Cells | Persister Cells | Spores |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culturability | Non-culturable on standard media [20] | Culturable after stress removal [22] | Culturable after germination [24] |

| Metabolic Activity | Low but detectable [20] [1] | Reduced/arrested [22] | Undetectable/minimal [24] |

| Formation Triggers | Moderate, long-term stress (starvation, temperature, salinity) [20] [1] | Stochastic switch or acute stress (antibiotics) [22] [21] | Nutrient depletion [24] [25] |

| Resuscitation | Requires specific conditions/time [20] [21] | Rapid after stress removal [22] | Nutrient-induced germination [24] |

| Genetic Basis | Stress-induced program [1] | Non-genetic, phenotypic [22] | Developmental program [24] |

| Structural Changes | Morphological changes (rod to coccoid) [1] | Minimal structural changes [22] | Highly specialized structures [24] |

| Antibiotic Tolerance | High tolerance [21] | High tolerance [22] | Extreme resistance [24] |

| Clinical Significance | Recurrent infections, undetectable by culture [20] [21] | Chronic infections, treatment failure [22] [26] | Disease initiation (anthrax, C. difficile) [24] |

The Dormancy Continuum Hypothesis

Emerging evidence suggests that these dormancy states may not be entirely discrete but exist along a physiological continuum [21]. The "dormancy continuum hypothesis" proposes that VBNC cells and persisters share similar molecular mechanisms but occupy different positions along a spectrum of metabolic activity and resuscitability [21]. Toxin-antitoxin systems (TAS), classically implicated in persister formation, have also been shown to induce the VBNC state, suggesting overlapping regulatory mechanisms [21]. In this model, persisters may represent a transitional state that can progress to the VBNC condition under prolonged stress exposure.

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

VBNC State Induction and Maintenance

The transition to the VBNC state involves complex molecular reprogramming in response to environmental stressors. In Escherichia coli, induction into the VBNC state under various stress conditions (temperature, metal, antibiotic) results in significant biomolecular alterations, including increased RNA levels and decreased protein and nucleic acid concentrations compared to culturable cells [1]. The 995 cmâ»Â¹ RNA band identified via ATR-FTIR spectroscopy has been proposed as a consistent biomarker across different stress conditions, suggesting fundamental reorganization of transcriptional machinery during VBNC entry [1].

Cells in the VBNC state exhibit increased peptidoglycan synthesis and cross-linking, contributing to their enhanced resistance to physical and chemical factors compared to their culturable counterparts [1]. This structural reinforcement, combined with reduced metabolic activity, allows VBNC cells to withstand environmental insults that would kill vegetative cells. The molecular regulation of VBNC state induction involves stress response pathways that coordinate the systematic shutdown of growth processes while maintaining essential functions for survival.

Persister Cell Formation Mechanisms

Persister cells can form through either stochastic triggering during normal growth or induction by environmental stresses such as antibiotic exposure, nutrient limitation, or oxidative stress [22] [21]. In Bacillus subtilis, different stress conditions generate varying numbers of persister cells and spores, indicating that persister formation is influenced by the specific nature of the stress encountered [22].

At the molecular level, persister formation frequently involves toxin-antitoxin systems where free toxin molecules inhibit essential cellular processes such as translation, leading to growth arrest [21]. This dormancy provides tolerance to antibiotics that target active cellular processes. Research demonstrates that persister cells coexist with VBNC cells in stressed populations, with human serum inducing the formation of both cell types through TAS regulation [21].

Sporulation and Germination Pathways

Bacterial sporulation represents the most complex and highly regulated dormancy pathway, involving cascades of genetic regulation and structural transformation [24] [25]. In Bacillus subtilis, sporulation timing is controlled by variable activation of the master regulator Spo0A through the sporulation phosphorelay, creating heterogeneity in spore formation within populations [25].

Spore revival involves a two-stage process: germination, triggered by nutrient germinants binding to specific germinant receptors (GRs), and outgrowth, where the spore reactivates biosynthetic processes and resumes vegetative growth [24]. Research has revealed that sporulation and spore revival are linked by a phenotypic memory whereby molecules carried over from the vegetative cell influence the spore's future revival capacity [25]. Alanine dehydrogenase has been identified as a key molecular determinant of this memory, coupling a spore's revival capacity to the gene expression history of its progenitors [25].

Table 2: Key Molecular Components in Bacterial Dormancy States

| Dormancy State | Molecular Components | Function |

|---|---|---|

| VBNC State | Increased RNA (995 cmâ»Â¹ band) [1] | Potential biomarker for VBNC detection |

| Modified peptidoglycan [1] | Enhanced structural resistance | |

| Stress response proteins [20] | Facilitation of survival under stress | |

| Persister Cells | Toxin-antitoxin systems [21] | Growth inhibition via translation disruption |

| Metabolic regulators [22] | Control of cellular dormancy depth | |

| Spores | Germinant receptors (GRs) [24] | Nutrient sensing and germination trigger |

| SpoVA channel [24] | DPA release during germination | |

| Cortex-lytic enzymes (CLEs) [24] | Cortex degradation during germination | |

| Alanine dehydrogenase [25] | Supports outgrowth via alanine metabolism |

Signaling Pathway Integration

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways and regulatory relationships governing entry into and exit from each dormancy state:

Diagram 1: Molecular pathways regulating bacterial dormancy states and resuscitation processes

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Differentiation via Flow Cytometry and Fluorescent Staining

Advanced detection methods are essential for differentiating between dormancy states due to their non-culturable characteristics. Flow cytometry combined with fluorescent staining provides a powerful approach for identifying and isolating these subpopulations [22] [27].

A validated protocol for differentiating and isolating persister cells from VBNC cells involves double staining with 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate (5(6)-CFDA) and propidium iodide (PI) [22]. 5(6)-CFDA is a membrane-permeable fluorogenic substrate that is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases to produce green fluorescence, indicating metabolic activity. PI is a membrane-impermeant dye that stains nucleic acids of membrane-compromised cells red. This combination allows identification of three populations: 5(6)-CFDA+/PI- (metabolically active intact cells, including persisters), 5(6)-CFDA-/PI+ (dead cells), and 5(6)-CFDA-/PI- (dormant cells with low metabolic activity, including VBNC cells) [22].

For Bacillus subtilis persister isolation, the following protocol has been established:

- Grow B. subtilis strain PS832 to mid-exponential phase

- Treat with 100× MIC of antimicrobial compounds (e.g., 12.5 μg/mL vancomycin, 6.25 μg/mL enrofloxacin) for 3 hours

- Wash cells to remove antibiotics

- Stain with 5(6)-CFDA and PI mixture

- Analyze and sort using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

- Collect 5(6)-CFDA+/PI- population as likely persisters [22]

The metabolic activity of sorted cells can be further confirmed through regrowth experiments in fresh media, where persisters resume growth while VBNC cells remain non-culturable [22].

A sophisticated approach for monitoring persister resuscitation employs fluorescent protein dilution combined with ampicillin-mediated cell lysing [27]. This methodology enables real-time tracking of persister wake-up at single-cell resolution:

- Engineer E. coli strains with chromosomally integrated IPTG-inducible mCherry expression cassette

- Induce mCherry expression during overnight growth

- Treat mid-exponential-phase cells with ampicillin for 3 hours to lyse growing cells

- Wash to remove antibiotic and IPTG

- Transfer to fresh media and monitor mCherry dilution via flow cytometry

- Identify resuscitating cells by decreasing fluorescence intensity (indicating protein dilution through cell division) [27]

This technique revealed that ampicillin persisters resuscitate within 1 hour after transfer to fresh media, with doubling times identical to normal cells (approximately 23 minutes) [27]. Cells maintaining high fluorescence without division represent VBNC populations, allowing simultaneous quantification of persisters, VBNC cells, and dead cells in antibiotic-treated cultures.

Research Reagent Solutions for Dormancy Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bacterial Dormancy Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Viability Stains | BacLight Live/Dead Kit (SYTO9/PI) [21] | Membrane integrity assessment |

| 5(6)-CFDA [22] | Metabolic activity indicator | |

| CTC [20] | Respiratory activity detection | |

| Molecular Probes | PMA dyes [1] | Selective DNA labeling (viable cells) |

| DAPI [1] | Total cell counting | |

| Expression Systems | IPTG-inducible mCherry [27] | Cell division tracking via protein dilution |

| Induction Agents | L-alanine [24] [25] | Spore germination trigger |

| Arsenate [27] | Metabolic inhibitor for persistence studies | |

| Antimicrobial Peptides | SAAP-148 [22] [23] | Persister eradication via membrane disruption |

| TC-19 [22] [23] | Membrane permeability and fluidity alteration |

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Dormancy Assessment

The following diagram outlines an integrated experimental approach for identifying and characterizing different bacterial dormancy states:

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental workflow for identification and characterization of bacterial dormancy states

Research Implications and Future Directions

The differentiation between VBNC cells, persister cells, and spores has profound implications for clinical microbiology, pharmaceutical development, and food safety. Understanding the distinct physiological bases of these dormancy states enables more targeted approaches to combat persistent infections and microbial contamination.

In clinical settings, the inability to detect VBNC cells through conventional culture methods leads to underestimation of pathogenic presence and contributes to recurrent infections [20] [21]. Research demonstrates that VBNC cells maintain virulence potential and can resuscitate in vivo, causing disease recurrence after antibiotic treatment [21]. Similarly, persister cells play a well-established role in chronic infections such as tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis-associated infections, and biofilm-related device infections [22] [26]. The development of therapeutic agents that target dormancy mechanisms rather than just actively growing cells represents a promising frontier in antimicrobial drug development.

The food industry faces significant challenges from all three dormancy states, particularly since conventional processing methods may fail to eliminate dormant forms [26]. Bacterial spores present in ingredients can germinate after processing, while VBNC and persister cells of pathogens like Salmonella, Escherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes can evade detection and subsequently resuscitate, causing foodborne illness [26]. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have shown promise against persister cells and vegetative cells but demonstrate limited efficacy against spores, highlighting the need for multiple intervention strategies [22] [23] [26].

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise molecular triggers and regulatory networks governing transitions between dormancy states, developing rapid detection methods that can differentiate these states in clinical and industrial samples, and designing combination therapies that target multiple dormancy mechanisms simultaneously. The emerging understanding of the "dormancy continuum" suggests that therapeutic approaches may need to address the dynamic nature of bacterial physiology across this spectrum rather than targeting discrete states in isolation [21].

As research methodologies advance, particularly in single-cell analysis and omics technologies, our understanding of these sophisticated bacterial survival strategies will continue to deepen, potentially revealing new vulnerabilities that can be exploited to overcome the significant challenges posed by bacterial dormancy in medicine and industry.

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are genetic modules ubiquitously found in prokaryotic genomes, composed of a stable toxin that inhibits cell growth and a labile antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin [28]. Recent research has illuminated their significant role in bacterial stress response mechanisms, including the formation of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells—a dormant state in which bacteria fail to grow on standard laboratory media but retain metabolic activity and the potential to resuscitate [29] [30]. The VBNC state presents substantial challenges for clinical diagnostics, food safety, and public health, as pathogens in this state evade conventional detection methods while maintaining virulence [29]. This whitepaper examines the physiological mechanisms through which TA systems regulate entry into the VBNC state, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals investigating bacterial persistence and novel therapeutic strategies.

TA System Classification and Molecular Mechanisms

TA systems are classified into eight types (I-VIII) based on the nature and neutralizing mechanism of the antitoxin [28]. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each type:

Table 1: Classification of Toxin-Antitoxin Systems

| Type | Toxin Nature | Antitoxin Nature | Mechanism of Antitoxin Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Protein | Anti-sense RNA | Inhibits toxin mRNA translation [28] |

| II | Protein | Protein | Binds and directly inhibits toxin protein [28] [31] |

| III | Protein | RNA | Binds and inhibits protein toxin [28] |

| IV | Protein | Protein | Prevents toxin from binding its cellular target [28] |

| V | Protein | Protein (RNase) | Degrades toxin mRNA specifically [28] |

| VI | Protein | Protein | Stimulates degradation of toxin protein [28] |

| VII | Protein | Protein (Enzyme) | Oxidizes a cysteine residue to inactivate toxin [28] |

| VIII | RNA (sRNA) | RNA | Inactivates toxin RNA via anti-sense binding [28] |

Among these, Type II systems are the most abundant and well-characterized. In these systems, the toxin is a protein that targets essential cellular processes, including translation (through modifications of mRNA, tRNA, or rRNA), replication (via adenylylation of DNA gyrase), and ATP production (by damaging cell membranes) [28]. The antitoxin, also a protein, binds the toxin to form a transcriptionally autoregulated complex [31]. Under stress conditions, proteolytic degradation of the labile antitoxin leads to toxin activation and subsequent growth arrest [28] [32].

The VBNC State: A Distinct Stress Response

The VBNC state is a unique survival strategy adopted by a wide range of bacteria in response to adverse environmental conditions. It is defined by three primary characteristics: loss of culturability on media normally supportive of growth, maintenance of metabolic activity, and the capacity to resuscitate under appropriate conditions [30]. It is crucial to differentiate the VBNC state from other non-growing states:

Table 2: Differentiating Bacterial Dormancy States

| Feature | VBNC State | Persister Cells | Dormant Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culturability | Lost (CFU=0) | Retained (but nongrowing) | Lost or significantly reduced |

| Metabolic Activity | Measurably active | Reduced | Below detection limit |

| Induction | Moderate, long-term stresses (e.g., starvation, low temp) [30] | Specific stresses, often antibiotics [30] | Severe or prolonged stress |