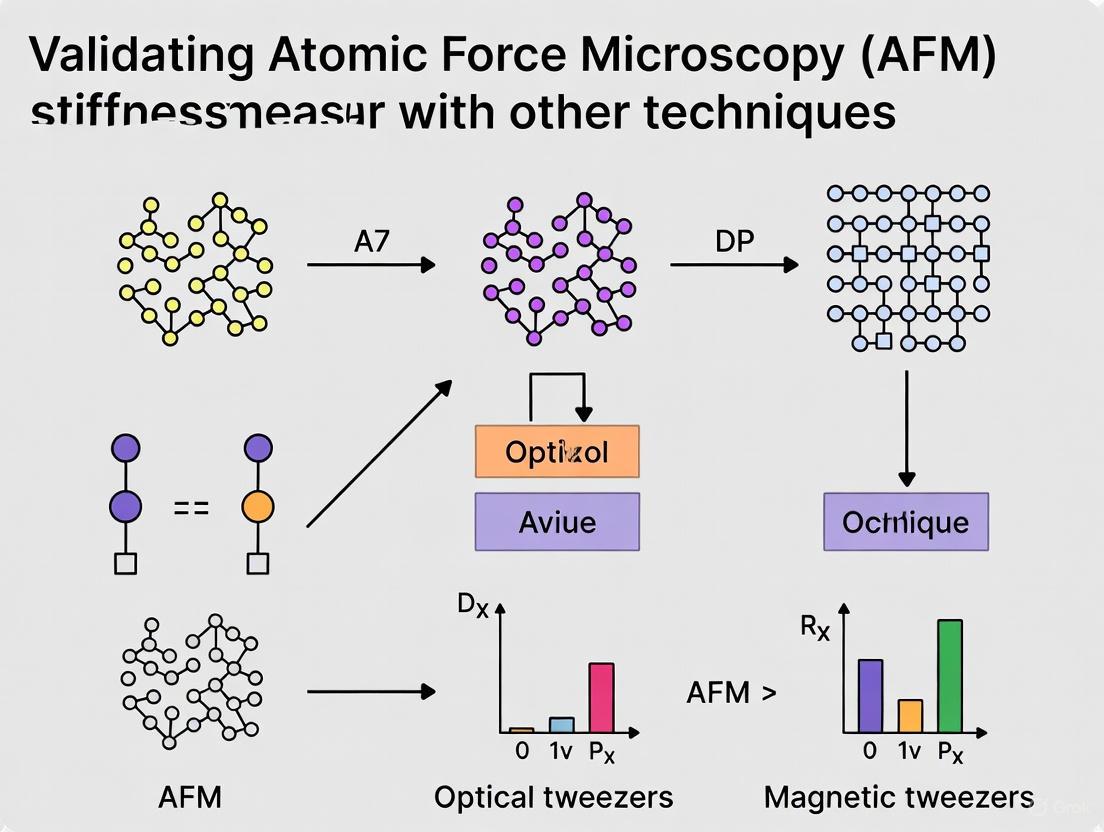

Validating AFM Stiffness Measurements: A Multimodal Framework for Robust Biomaterial and Cell Mechanobiology (2025)

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is the dominant technique for nanomechanical characterization in biomedicine, yet validating its measurements is paramount for reliability in research and drug development.

Validating AFM Stiffness Measurements: A Multimodal Framework for Robust Biomaterial and Cell Mechanobiology (2025)

Abstract

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is the dominant technique for nanomechanical characterization in biomedicine, yet validating its measurements is paramount for reliability in research and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of AFM stiffness data, covering foundational principles, advanced methodological applications, troubleshooting of common artifacts, and rigorous cross-validation with complementary techniques. We explore the integration of computational models, machine learning, and novel experimental pipelines to enhance accuracy, discuss current challenges, and outline future directions for establishing AFM as a validated tool in clinical translation.

The Fundamental Principles and Critical Need for Validation in AFM Nanomechanics

AFM as the Dominant Tool in Nanomechanical Property Mapping

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has firmly established itself as the dominant technique for characterizing mechanical properties at the nanoscale, revolutionizing fields from materials science to mechanobiology [1] [2]. This preeminence stems from AFM's unique capability to transform the interaction force between a sharp tip and a sample surface into quantitative maps of mechanical properties with exceptional spatial resolution [1]. Unlike ensemble techniques that provide average properties, AFM enables spatially-resolved mechanical property mapping at the nanoscale, revealing heterogeneity in materials and biological samples that was previously inaccessible [1] [2]. The AFM functions fundamentally as a mechanical microscope, measuring forces with sufficient sensitivity to quantify properties including elastic modulus, viscoelasticity, and adhesion in diverse environments from ambient air to physiological liquids [1] [2]. This article objectively compares AFM's performance against alternative nanomechanical characterization techniques, examining experimental data and methodologies that validate its dominance in the field.

Comparative Analysis of Nanoscale Mechanical Characterization Techniques

While several techniques enable nanoscale investigation, they differ significantly in their fundamental principles, capabilities, and limitations. The table below provides a systematic comparison of AFM against the primary electron microscopy-based alternatives for mechanical property assessment.

Table 1: Technique Comparison for Nanoscale Mechanical Property Mapping

| Criterion | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanical Data | Direct force measurement via tip-sample interaction; quantitative modulus, adhesion, and viscoelasticity maps [1] | Indirect inference from morphology; qualitative mechanical assessment [3] | Indirect inference from internal structure and defects; qualitative mechanical assessment [3] |

| Lateral Resolution | <1 - 10 nm [3] | 1-10 nm [3] | Atomic-scale, 0.1-0.2 nm (for structure) [3] |

| Vertical Resolution | Sub-nanometer [3] | No quantitative vertical contrast [3] | No vertical contrast (2D projection) [3] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; preserves native state [3] | Moderate (conductive coating often required) [3] | Extensive (ultra-thin sectioning required) [3] |

| Environmental Flexibility | High (air, vacuum, liquids, controlled atmospheres) [3] | Moderate (high vacuum typical; ESEM allows lower vacuum) [3] | Low (high vacuum required; cryo-TEM for frozen samples) [3] |

| Data Acquisition Throughput | Lower (detailed analysis of small areas) [3] | Higher (fast imaging over larger areas) [3] | Lower (time-consuming imaging and processing) [3] |

The comparative data reveals a clear technical rationale for AFM's dominance in direct mechanical property measurement: it provides quantitative mechanical data with high spatial resolution under physiologically relevant conditions, a combination unmatched by electron microscopy techniques [3]. While SEM and TEM excel at providing high-resolution structural and morphological information, they offer only indirect, qualitative inferences about mechanical properties and require environments that can alter or damage soft, hydrated samples [3].

Core AFM Methodologies for Nanomechanical Mapping

AFM-based nanomechanical property mapping, or simply nanomechanical mapping, involves sequentially measuring a mechanical property at each point on a sample surface to generate a spatial map [1] [2]. The techniques can be broadly classified into three categories based on their operational principles.

Force Volume Mode

This mode is based on acquiring a force-distance curve (FDC) in each pixel of the image [1] [2]. The tip-sample distance is modulated (using triangular or sinusoidal waveforms), and the cantilever's deflection is recorded as a function of this distance. The approach and retraction sections of the curve provide information on properties like elasticity and viscoelasticity, the latter indicated by hysteresis in the curve [1]. These raw force curves are then transformed into quantitative maps of mechanical parameters by fitting them to an appropriate contact mechanics model, such as the Hertz or Sneddon models [1] [4].

Nano-Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (Nano-DMA)

In this nanorheology approach, the tip is first brought into contact with the sample at a set predefined force. Then, a small oscillatory signal is applied to the cantilever or the sample stage while the tip remains in contact [1] [2]. The viscoelastic properties of the material are encoded in the time lag between the tip's indentation and the resulting force response [1]. This method, inspired by macroscopic Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA), allows for the extraction of storage and loss moduli at specific frequencies [2].

Parametric Modes

These methods involve driving the cantilever at its resonant frequency while in contact with the sample. Mechanical properties are parameterized from the observables of the tip's oscillation—such as amplitude, phase shift, or frequency—without directly acquiring a full force-distance curve at each point [1] [2]. Techniques like bimodal AFM, contact resonance AFM, and multi-harmonic AFM fall into this category. They can offer higher imaging speeds but may require more complex numerical methods to relate the observables to mechanical properties [1].

Experimental Workflow for Quantitative AFM Stiffness Measurement

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for obtaining quantitative stiffness measurements via AFM force spectroscopy, highlighting critical steps for validation.

Critical Experimental Considerations and Corrections

Adherence to robust experimental protocols is paramount for validating AFM stiffness measurements. Key considerations include:

Probe Selection and Calibration: The choice of cantilever (with appropriate spring constant and tip geometry) and its accurate calibration are foundational, as the measured force is derived from the cantilever's deflection and its known spring constant [1].

Model Selection and Fitting: The repulsive portion of the force-distance curve is fit with a contact mechanics model (e.g., Sneddon-Hertz) to extract the Young's Modulus [4]. The model must match the tip geometry (e.g., spherical, conical).

Accounting for Sample Topography (Tilt Correction): Traditional models assume perpendicular indentation on a planar surface. For non-planar samples, this introduces significant error. A 2024 study demonstrated that incorporating local tilt angles into the Hertz-Sneddon model via correction coefficients is essential for accurate measurements on inclined surfaces, a common scenario with soft materials and biological cells [4].

Accounting for Finite Thickness (Bottom Effect Correction): For thin samples like cells, the underlying stiff substrate makes the sample appear stiffer than it is—the bottom stiffness effect [5]. Using a semi-infinite model causes the apparent modulus to artificially increase with indentation force. A 2025 study provided direct experimental evidence that applying a finite-thickness correction model yields a force-independent, true modulus value, while models ignoring this effect produce artifacts [5].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of AFM nanomechanical experiments requires specific materials and tools. The following table details key components of a typical research setup.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AFM Nanomechanics

| Item | Function / Description | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Cantilevers | Silicon or silicon nitride probes with defined tip geometry and spring constant; the primary force transducer [3]. | Choice depends on application: soft levers (low k) for biological cells; stiffer levers for polymers; sharp tips for high resolution [3] [5]. |

| Calibration Samples | Reference samples with known, uniform mechanical properties (e.g., polyacrylamide gels). | Used to validate the accuracy of the entire measurement and data processing protocol [4]. |

| Liquid Cell | Enables AFM operation in fluid environments, essential for biological samples [3]. | Maintains hydration; allows study in near-physiological conditions or controlled chemical environments [3]. |

| Contact Mechanics Models | Mathematical frameworks (e.g., Hertz, Sneddon, Power-Law Rheology) used to convert force-distance data into mechanical properties [1] [4] [5]. | Model must be matched to tip geometry; advanced models correct for effects like finite sample thickness and viscoelasticity [4] [5]. |

| Bottom-Effect Correction Model | A finite-thickness model that accounts for the influence of a rigid substrate on measurements of thin samples [5]. | Crucial for obtaining accurate moduli from cells and other thin films; prevents overestimation of stiffness [5]. |

AFM's status as the dominant tool for nanomechanical property mapping is well-justified by its direct force measurement capability, exceptional resolution, and operational versatility across environments. The validation of its measurements, however, hinges on rigorous experimental protocols. As evidenced by recent research, key factors include the move toward high-speed mapping modes, the critical application of correction models for tilt and substrate effects, and the emerging use of machine learning to bridge simulation and experiment [1] [6] [4]. For researchers in mechanobiology and drug development, this demonstrates that while AFM provides unparalleled insights into cellular and material mechanics, ensuring data accuracy requires careful attention to sample-specific geometries and properties.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has become the dominant technique for characterizing the nanomechanical properties of soft materials, including live cells and synthetic polymers [5] [1]. However, the accuracy of these measurements is fundamentally challenged by physical artifacts, among which the bottom stiffness effect represents a critical and often-overlooked source of error. This effect causes soft, finite-thickness samples to appear stiffer than they truly are due to the influence of the underlying rigid substrate [5]. For decades, this phenomenon was primarily a theoretical concern, but recent experimental evidence has confirmed its significant impact on mechanobiological studies [5] [7]. This guide objectively compares the performance of conventional semi-infinite models against finite-thickness correction models, providing researchers with validated experimental protocols and data to enhance measurement accuracy in drug development and basic research.

Theoretical Background: From Semi-Infinite Assumptions to Finite-Thickness Corrections

Conventional Contact Mechanics Models

Traditional AFM nanomechanical analysis predominantly relies on Sneddon-Hertzian contact mechanics, which models the sample as an elastic half-space with infinite thickness [4]. These models assume that the force applied by the AFM tip depends solely on the material's mechanical properties, indentation depth, and tip geometry [5]. The fundamental relationship for a conical indenter, for instance, is expressed as:

$$F = \frac{2}{\pi} \cdot \frac{E}{1-\nu^{2}} \cdot \delta^{2} \cdot \text{tan}(\alpha)$$

where (F) is the applied force, (E) is the Young's modulus, (\nu) is Poisson's ratio, (\delta) is indentation depth, and (\alpha) is the cone's half-angle [4].

The Finite-Thickness Correction Framework

Finite-thickness or "bottom-effect" correction models incorporate an additional critical parameter: the sample height ((h)) [5]. These models account for the physical reality that compressive stress from the tip propagates through the sample, reflects at the rigid substrate interface, and amplifies the measured force. For a paraboloid tip, the force is calculated as a series expansion dependent on height:

[F \approx \sum{j} \alphaj \cdot E0 \cdot \frac{t0^\gamma}{(1-\gamma)} \cdot \frac{d}{dt} \int0^t \frac{I^{bj}(s)}{(t-s)^\gamma} ds]

with coefficients (\alphaj) and (\betaj) converging to semi-infinite model values only as (h \rightarrow \infty) [5].

Table 1: Theoretical Comparison of AFM Contact Mechanics Models

| Model Feature | Semi-Infinite Models | Finite-Thickness Models |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Assumption | Sample is an infinite half-space | Sample has finite height above substrate |

| Key Input Parameters | Modulus, Poisson's ratio, tip geometry, indentation | All semi-infinite parameters plus sample height |

| Stress Field Consideration | Ignores substrate boundary effects | Accounts for stress reflection at substrate interface |

| Theoretical Accuracy for Thin Samples | Low - significant overestimation of modulus | High - provides true material properties |

| Experimental Validation | Extensive but potentially flawed for cells | Recently confirmed experimentally [5] |

Experimental Evidence: Quantifying the Bottom Stiffness Effect

Direct Experimental Demonstration

A landmark 2025 study designed a controlled experiment to isolate and quantify the bottom stiffness effect using HeLa cells cultured on standard Petri dishes [5]. The experimental protocol involved:

- Cell Preparation: HeLa cells cultured under standard conditions on glass Petri dishes (~100 GPa stiffness)

- AFM Setup: Spherical tips (R = 5 μm) operating in force-distance curve mode

- Measurement Protocol: Multiple force-distance curves acquired at different locations (cytoplasm and nucleus) while varying maximum applied force

- Height Measurement: Combined confocal microscopy and AFM topography for accurate cell height quantification

- Data Analysis: Parallel fitting with semi-infinite and finite-thickness power-law rheology models

Comparative Quantitative Results

The experimental results provide definitive evidence of the bottom stiffness effect and its impact on mechanical property determination:

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Model Performance on HeLa Cells [5]

| Experimental Condition | Semi-Infinite Model Result | Finite-Thickness Model Result | Artifact Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Applied Force (Cytoplasm) | Apparent modulus: ~1.2 kPa | True modulus: ~0.8 kPa | +50% overestimation |

| High Applied Force (Cytoplasm) | Apparent modulus: ~2.1 kPa (increases with force) | True modulus: ~0.8 kPa (constant with force) | +162% overestimation |

| Nuclear Region | Apparent modulus increases with force | True modulus remains constant | Force-dependent artifact |

| Fluidity Coefficient (γ) | Remains constant with force | Remains constant with force | No significant effect |

The critical finding was that the semi-infinite model produced an apparent modulus that increased with applied force, a clear artifact since material properties should be force-independent [5]. This artifact was eliminated when using the finite-thickness model, which yielded a constant modulus regardless of indentation force.

Additional Substrate-Related Artifacts

Beyond the bottom stiffness effect, other substrate-related artifacts can compromise AFM measurements:

- Surface Inclination Artifacts: Non-planar sample surfaces violate the perpendicular indentation assumption of Hertz models, requiring geometrical corrections [4]

- Electrostatic Artifacts: In Magnetic Force Microscopy (MFM), electrostatic interactions can distort mechanical measurements unless compensated with Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) [8]

- Optical Interference Artifacts: Reflections from the substrate can create wave-like patterns in AFM images, mitigated through optimized beam alignment [8]

Methodological Protocols: Implementing Corrected Measurement Approaches

Protocol for Validated Bottom-Effect Correction

Based on the experimental evidence, researchers should implement the following protocol for accurate nanomechanical characterization:

Step 1: Sample Height Determination

- Use confocal microscopy or AFM topography to measure local cell height at each measurement point

- Account for natural height variations (2-3 μm at cytoplasm edges, 7-15 μm above nucleus) [5]

Step 2: AFM Tip Selection and Calibration

- Select spherical tips with well-characterized radius (R ≥ 1 μm most affected) [5]

- Precisely calibrate cantilever spring constant and sensitivity

Step 3: Force-Distance Curve Acquisition

- Acquire curves at multiple maximum force values (e.g., 0.5-5 nN range)

- Maintain approach/retraction velocity consistency

- Record sufficient data points for viscoelastic modeling

Step 4: Model Fitting with Height Correction

- Implement finite-thickness power-law rheology model [5]

- Use height values as direct input to correction model

- Fit both elastic (E₀) and viscoelastic (γ) parameters simultaneously

Step 5: Validation and Quality Control

- Verify that calculated modulus remains constant across force ranges

- Compare nuclear vs. cytoplasmic regions with appropriate height inputs

- Reject measurements showing force-dependent modulus in corrected model

Advanced Nanomechanical Mapping Techniques

For comprehensive characterization, consider these advanced AFM modes:

- Force Volume Mapping: Acquires force-distance curves at each pixel for spatial property mapping [1]

- Nano-Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (nDMA): Measures viscoelastic properties across frequency ranges (0.1-5000 Hz) [9]

- Bimodal AFM: Simultaneously excites multiple cantilever eigenmodes for high-speed viscoelastic mapping [1] [9]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for AFM Mechanobiology Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Function | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Substrates | Glass Petri dishes, poly(HEMA), collagen I, PDMS | Stiffness (0.5 kPa - 100 GPa) significantly impacts bottom effect [5] [9] |

| AFM Cantilevers | Spherical tips (R = 1-5 μm), conical tips | Larger radii more susceptible to bottom effect [5] |

| Calibration Standards | Reference samples of known modulus | Essential for cantilever calibration and method validation |

| Height Measurement Tools | Confocal microscopy, AFM topography | Critical for accurate finite-thickness correction [5] |

| Analysis Software | Custom finite-thickness model implementation | Semi-infinite models insufficient for thin samples [5] |

| Environmental Control | Liquid cells, temperature regulation | Maintain physiological conditions for live cells |

| BMS-191095 | BMS-191095: Selective mitoKATPChannel Activator | |

| 1-Oleoyl-sn-glycerol | 1-Oleoyl-sn-glycerol, CAS:129784-87-8, MF:C₂₁H₄₀O₄, MW:356.54 | Chemical Reagent |

The experimental evidence definitively establishes that the bottom stiffness effect is not merely a theoretical concern but a significant source of artifact in AFM-based mechanobiology. The comparison between conventional and finite-thickness models demonstrates that uncorrected measurements can overestimate cell modulus by 50-160% or more, with errors increasing at higher indentation forces [5]. For the drug development community, these artifacts potentially compromise the validity of mechano-pharmacological studies and biomarker identification.

Moving forward, researchers should:

- Systematically implement finite-thickness corrections for all cell mechanics studies

- Report sample height measurements alongside mechanical properties

- Validate results by testing modulus independence from applied force

- Consider advanced AFM modes like PT-AFM nDMA for comprehensive viscoelastic characterization [9]

The integration of these validated protocols will enhance measurement accuracy and enable more reliable correlations between nanomechanical properties and biological function in health and disease.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has established itself as the dominant technique for characterizing nanomechanical properties across diverse fields, including materials science, cell biology, and drug development [5] [2]. Conventional AFM analysis predominantly relies on contact mechanics models, such as Hertzian mechanics, which assume the sample behaves as a semi-infinite half-space [10]. This assumption implies that the compressive stress from the indenting tip dissipates infinitely within the material, unaffected by underlying substrates or finite geometric boundaries. However, this foundational premise is routinely violated in real-world applications, particularly in biological systems and thin polymer films.

The bottom stiffness effect describes the phenomenon where the finite thickness of a sample and the rigidity of its underlying substrate significantly alter force measurements during AFM indentation [5]. When an AFM tip indents a thin, soft sample on a rigid substrate, the compressive stress propagates through the sample until it reaches the substrate interface. The stress then reflects back toward the tip, resulting in an increased measured force and consequently an overestimation of the sample's elastic modulus [5] [11]. For mammalian cells, which typically exhibit Young's moduli in the 0.5–10 kPa range and heights of just 2–15 μm, this effect can introduce substantial errors, potentially compromising the validity of mechanobiological conclusions [5]. This article systematically compares the theoretical frameworks, experimental evidence, and correction methodologies addressing finite thickness effects, providing researchers with a validated toolkit for obtaining quantitatively accurate nanomechanical data.

Theoretical Frameworks: From Hertzian Foundations to Finite-Thickness Corrections

The evolution of contact mechanics models for AFM reveals a progressive refinement from simple scenarios to those accounting for complex sample geometries.

The Hertzian Baseline and Its Limitations

The Hertz model provides the foundational relationship between applied force ((F)), indentation depth ((\delta)), and the reduced Young's modulus ((E^)) for a spherical indenter of radius (R): [ F = \frac{4}{3} E^ R^{1/2} \delta^{3/2} ] where (E^* = E/(1-\nu^2)) and (\nu) is the Poisson's ratio [11]. This model, along with its conical and flat-punch counterparts, assumes the sample is isotropic, linear-elastic, and most critically, of infinite thickness [10]. The model's failure in thin samples arises because the measured total displacement ((\delta)) is the sum of the local indentation at the tip-sample contact ((\deltaI)) and the compression at the sample-substrate interface ((\deltaC)): (\delta = \deltaI + \deltaC) [11]. Standard Hertzian analysis attributes the entire displacement to (\delta_I), thereby overestimating the material's stiffness.

Finite-Thickness and Bottom-Effect Correction Models

To address these limitations, several analytical models incorporating finite thickness ((H)) have been developed. These models introduce a correction function, (f(\delta, H)), that modifies the Hertzian equation [10]: [ F = F_{\text{inf.thickness}} \cdot f(\delta, H) ] The functional form of (f(\delta, H)) depends on the indenter geometry and the sample's adhesion to the substrate. The underlying principle is that the correction must account for the ratio of the contact radius ((r)) to the sample height ((H)). As this ratio increases, the substrate's stiffening effect becomes more pronounced.

Table 1: Summary of Finite-Thickness Correction Models for Different Indenter Geometries

| Indenter Geometry | Model Formulation | Key Parameters | Applicable Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paraboloid/Spherical [5] [10] | ( F = \frac{16}{9} E^* R^{1/2} \delta^{3/2} \left(1 + c'1 \frac{R^{1/2}\delta^{1/2}}{H} + c'2 \frac{R\delta}{H^2} + \cdots \right) ) | (c'1, c'2, ...) are substrate-dependent coefficients. For bonded samples: (c'1=1.133, c'2=1.283) [10]. | Small indentations, (\delta \ll R); Bonded or non-adherent samples. |

| Conical [10] | ( F = \frac{8}{3\pi} E^* \tan(\theta) \delta^2 \left(1 + c1 \frac{\delta}{H} + c2 \frac{\delta^2}{H^2} + \cdots \right) ) | Half-angle (\theta). For bonded samples (v=0.5): (c1=0.721\tan(\theta), c2=0.650\tan^2(\theta)) [10]. | Pyramidal AFM tips approximated as cones. |

| Power-Law Rheology [5] | ( F(t) = \sum{j} \alphaj \int{0}^{t} \dot{\delta}(\tau) E{\alpha, \alpha} \left[ -\gamma (t-\tau)^{\alpha} \right] / (t-\tau)^{1-\beta_j} d\tau ) | Scaling modulus (E0), fluidity coefficient (\gamma), coefficients (\alphaj, \beta_j) dependent on (H) [5]. | Viscoelastic materials like cells; accounts for time-dependent response. |

The Double-Contact Model and Finite Element Analysis

The double-contact model offers a physically intuitive framework, explicitly separating the tip-sample contact from the sample-substrate contact [11]. It models the soft sample as being compressed between two rigid surfaces: the AFM tip and the substrate. Finite Element Modelling (FEM) serves as a powerful computational tool to validate these analytical models and simulate scenarios where analytical solutions are intractable, such as complex surface topographies or heterogeneous materials [11]. FEM studies confirm that neglecting sample deformation leads to inaccurate topography measurements and elastic modulus values, with nanoparticles appearing larger or smaller than their true dimensions depending on the imaging force [11].

Figure 1: Conceptual workflow comparing models for AFM indentation. Traditional Hertzian analysis leads to errors, while finite-thickness models and FEM simulations enable accurate property determination.

Experimental Evidence and Protocol for Validation

Theoretical predictions of the bottom-effect have existed for years, but direct experimental validation in biological systems has been challenging. A key 2025 study on live cells finally provided conclusive evidence [5].

Key Experimental Workflow

The following protocol, adapted from Moura et al. (2025), outlines the steps for validating and correcting for the bottom stiffness effect in cellular AFM [5].

Objective: To quantitatively isolate the influence of the substrate's stiffness on AFM force curves and determine the true mechanical properties of a thin, soft sample.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Line: HeLa cells or other adherent cell type.

- AFM System: Equipped with a liquid cell for physiological conditions.

- Cantilevers: Spherical tipped cantilevers (e.g., ( R \approx 5 \mu m ) silica or polystyrene spheres).

- Culture Medium: Appropriate physiological buffer (e.g., DMEM with supplements).

- Confocal Microscope: For correlative cell height measurements (optional but recommended).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Culture cells on a rigid substrate (e.g., glass Petri dish) to a suitable confluency. Perform AFM measurements in physiological buffer at a controlled temperature.

- Cell Height Mapping: Acquire confocal microscopy Z-stacks or use AFM topography images in conjunction with a defined contact point to determine the local cell height ((H)) at each indentation point [5].

- Force-Distance Curve (FDC) Acquisition:

- Position the AFM tip over regions of interest (e.g., cytoplasm, nucleus).

- Acquire multiple FDCs at the same location while systematically varying the maximum applied force (e.g., from 0.5 to 5 nN).

- Ensure a sufficient sampling rate to capture the approach and retraction curves accurately.

- Data Fitting with Two Models:

- Semi-Infinite Model: Fit the approach segment of each FDC using a semi-infinite power-law rheology model. Extract the apparent scaling modulus ((E{0,apparent})).

- Finite-Thickness Model: Fit the same data using a bottom-effect correction model (e.g., power-law rheology with finite-thickness corrections from Table 1), using the measured local height ((H)) as an input. Extract the true scaling modulus ((E{0,true})).

- Validation Analysis:

- Plot the apparent modulus ((E{0,apparent})) and the true modulus ((E{0,true})) against the maximum indentation force.

- A hallmark of the bottom-effect is an increase in (E{0,apparent}) with increasing force for the semi-infinite model, as higher forces drive the stress field deeper into the sample, engaging the stiff substrate more.

- The corrected modulus ((E{0,true})) should remain constant and independent of the applied force, confirming the correction's validity [5].

Experimental Findings and Data Comparison

The experimental results from HeLa cells clearly demonstrate the artifact induced by the substrate. The study showed that when using a semi-infinite model, the apparent modulus could increase by a factor of two or more as the indentation force was raised. This trend was observed on both the cytoplasmic and nuclear regions. Crucially, this force-dependence vanished when the data was analyzed with the bottom-effect correction model, yielding a constant, intrinsic modulus value [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Outcomes from Finite-Thickness AFM Studies

| Study System | Experimental Approach | Key Finding | Impact of Correction |

|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa Cells [5] | FDCs with varying force on cytoplasm/nucleus; fit with semi-infinite vs. finite-thickness power-law model. | Apparent modulus increases with force without correction; becomes constant with correction. | Reveals intrinsic, force-independent cell stiffness; prevents overestimation. |

| Self-Assembled & Lipid Bilayers [5] | FDCs on bilayers of varying, controlled thickness (number of monolayers). | Force for a given indentation decreases as the number of layers (thickness) increases. | Directly validates theoretical prediction that force is thickness-dependent. |

| Oocytes (ZP & Cytoplasm) [12] | AFM indentation combined with a layered Finite Element Model. | Young's modulus of ZP: ~7 kPa; Cytoplasm: ~1.55 kPa. | Enables accurate simulation of oocyte deformation in micropipettes (<5.2% error). |

| Fibroblasts [10] | FDCs analyzed via a simplified method using the work of indentation and an average correction factor (g(c)). | Simplifies the complex fitting process for thin samples. | Makes finite-thickness corrections more accessible for routine lab use without complex fitting. |

Successful execution of validated AFM nanomechanical experiments requires specific materials and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Finite-Thickness AFM

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Spherical AFM Tips | Provides a well-defined, axisymmetric geometry for reliable contact mechanics models. | Silica or polystyrene colloids (( R = 1 - 5 \mu m)) glued to tipless cantilevers [5]. |

| Calibrated Cantilevers | Ensures accurate force measurement. Spring constant must be determined prior to experiment. | Contact-based thermal tune method is standard; rectangular or V-shaped levers [13]. |

| Functionalized Substrata | Controls cell adhesion and can be used to study the substrate stiffness effect in mechanobiology. | Glass or Petri dishes; polyacrylamide gels of tunable stiffness [5]. |

| AFM Software with Custom Fitting | Enables implementation of finite-thickness correction models beyond built-in Hertzian analysis. | Open-source software (e.g., AFMfit [14]) or custom scripts in MATLAB/Python. |

| Finite Element Analysis Software | For computational validation of experiments and modeling of complex sample geometries. | Commercial (e.g., Abaqus [11]) or open-source FEA packages. |

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for validating finite-thickness effects. The key validation step involves comparing the force-dependence of moduli obtained from semi-infinite and finite-thickness models.

The assumption of a semi-infinite half-space is a significant oversimplification for thin samples, systematically skewing AFM-based mechanical property measurements. The bottom stiffness effect is not a minor perturbation but a fundamental physical phenomenon that must be addressed for quantitative accuracy, particularly in cell mechanics and soft matter research [5] [11] [10].

The choice of correction strategy—be it an analytical bottom-effect model for homogeneous films [10], a power-law rheology framework for viscoelastic cells [5], or a full FEM simulation for complex geometries [11] [12]—depends on the sample system and the required precision. The experimental protocol of varying indentation force provides a straightforward internal validation for the effectiveness of the correction. As the field progresses, the integration of these corrections into standard analysis software and the development of simplified methods [10] will be crucial for bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical implementation, ensuring that AFM fulfills its potential as a tool for truly quantitative nanomechanical characterization.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has become a dominant technique for characterizing mechanical properties at the nanoscale, enabling stiffness measurements of biological samples from single molecules to living cells under near-physiological conditions [15] [2]. However, the translation of AFM measurements into reliable biomechanical data requires rigorous validation against established methods and reference standards. In biomedicine, where mechanical properties can serve as crucial indicators of cellular health, disease states, and therapeutic efficacy, establishing ground truth through comprehensive validation is not merely best practice—it is scientifically non-negotiable [12] [16].

The fundamental challenge in AFM biomechanics stems from the technique's inherent complexity: measurements depend on numerous factors including appropriate selection of AFM modes, proper calibration of cantilevers, careful sample preparation, and correct application of contact mechanics models [15] [4]. Without systematic validation, reported mechanical properties may reflect methodological artifacts rather than true biological characteristics, potentially leading to erroneous scientific conclusions and failed translational applications.

This guide objectively compares AFM stiffness measurement validation with complementary techniques, providing experimental data and protocols to establish robust mechanical characterization in biomedical research.

Comparative Analysis of Biomechanical Validation Techniques

AFM stiffness measurements do not operate in isolation; they must be contextualized within a broader experimental framework that includes reference materials, computational modeling, and orthogonal measurement techniques. The following comparison examines the landscape of validation methodologies available to biomedical researchers.

Table 1: Techniques for Validating AFM Stiffness Measurements in Biomedical Research

| Technique | Principle | Applications in Validation | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Material Calibration | Uses standards with certified mechanical properties | Calibrating AFM systems using materials with known Young's modulus [17] | Traceable to SI units, quantitative, commercially available | Limited biological relevance, may not match soft matter mechanics |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) | Computational simulation of indentation physics | Predicting force-indentation curves for model validation [4] [12] | Can model complex geometries and material behaviors, provides mechanistic insight | Computationally intensive, requires accurate material models |

| Stiffness Tomography | Segmented Hertz model fitting at different indentation depths | Detecting subsurface structures and validating homogeneity assumptions [16] | Provides 3D mechanical information, identifies depth-dependent properties | Increased computational complexity, model-dependent |

| Concurrent Force Spectroscopy | Comparative measurements within the same experiment [18] | Controlling for calibration errors in relative mechanical studies | Eliminates inter-experimental calibration variability, improves accuracy | Requires specialized sample preparation or instrumentation |

| Multiphysics Modeling | Integrated modeling of fluid-structure interactions [12] | Validating measurements in complex biological environments (e.g., cells in fluid) | Accounts for environmental factors, more physiologically relevant | High complexity, multiple fitting parameters |

| Correlative Microscopy | Combining AFM with SEM or other microscopy [19] | Correlating mechanical properties with structural features | Provides direct structure-function correlation, enhances interpretation | Instrumentationally complex, registration challenges |

Experimental Data: Quantitative Comparisons Across Techniques

Rigorous validation requires quantitative comparison of stiffness values obtained through AFM with those derived from independent methods. The following data, compiled from recent studies, highlights both the concordance and discrepancies that can emerge from multi-technique approaches.

Table 2: Experimental Stiffness Values Across Validation Methods in Biological Systems

| Biological Sample | AFM Measurement | Validation Method | Validated Value | Reported Discrepancy | Identified Source of Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine Oocyte Zona Pellucida | 6.8-7.2 kPa [12] | Finite Element Model of micropipette aspiration | 7.0 kPa [12] | ~5.2% deformation error | Model accounted for layered structure (ZP vs. cytoplasm) |

| Live Mammalian Cells | 0.5-20 kPa (highly variable) [2] | Stiffness Tomography with segmented Hertz fit [16] | Cortical actin network: ~150-180 nm depth [16] | Up to 300% local variation | Detection of subsurface structures invisible to surface AFM |

| Polyacrylamide Gels | Overestimation on tilted surfaces [4] | Tilt-corrected Hertz model | 10-25% correction factor dependent on tilt angle [4] | Angle-dependent: 15-40% overestimation | Traditional Hertz model assumes perpendicular indentation |

| C3 Domain Polyproteins | Inter-experimental variation: 19% [18] | Concurrent force spectroscopy | Reduction to 3.2% RSD [18] | 6-fold accuracy improvement | Elimination of calibration uncertainties between experiments |

| Polystyrene Nanoparticles | Height: <5% tip-induced error [19] | SEM correlation of same particles | Lateral dimensions require tip-deconvolution [19] | Lateral: 10-25% broadening | Tip convolution effects minimized in height measurements |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol: Stiffness Tomography for Subsurface Validation

Stiffness tomography enables researchers to detect subsurface structures and validate the homogeneity assumption inherent in many AFM mechanical models [16].

Sample Preparation:

- Culture cells on sterile, glass-bottom Petri dishes compatible with inverted microscopy

- For actin disruption studies: prepare 10 μM cytochalasin B solution in DMSO; dilute in culture medium for 5 μM final concentration

- Use triangular silicon nitride cantilevers with nominal spring constant of 0.06 N/m and tip radius of 20 nm

AFM Acquisition Parameters:

- Operate AFM in force-volume mode with acquisition rate of 7 Hz

- Set scan size to 2×2 μm with 32×32 (1024) force-distance curves

- Sample each force-distance curve with 256 points

- Maintain consistent loading rate across all measurements

- Record reference curves on stiff substrate (e.g., bare dish) for subtraction

Data Processing Workflow:

- Subtract reference force-distance curve from sample curves to obtain force-indentation (FI) data

- Segment each FI curve into equal-depth intervals (typically 10 nm segments)

- Apply Hertz contact model to each segment independently:

- For conical tips: $F = \frac{2}{\pi} \cdot \frac{E}{1-\nu^2} \cdot \delta^2 \cdot \tan(\alpha)$

- Where E is Young's modulus, ν is Poisson's ratio, δ is indentation, and α is half-opening angle

- Construct 3D stiffness matrix from segmental Young's moduli

- Generate depth-resolved stiffness maps with color-coded Young's modulus values

Validation Metrics:

- Compare stiffness profiles before/after cytoskeletal disruption

- Identify depth-dependent stiffness transitions indicating subsurface features

- Correlate mechanical features with fluorescence microscopy when available

Protocol: Concurrent Force Spectroscopy for Calibration Validation

Concurrent atomic force spectroscopy addresses calibration uncertainties by comparing samples within the same experiment, eliminating inter-experimental variability [18].

Sample Patterning for Concurrent Measurements:

- Chemically functionalize AFM substrate with patterned regions for different samples

- Use microcontact printing or microfluidics to create adjacent sample regions

- For protein studies: employ HaloTag or sortase-mediated labeling for specific attachment

- Verify pattern quality and specificity using fluorescence microscopy

Concurrent AFM Acquisition:

- Select cantilever appropriate for expected force range (typically 0.06-0.6 N/m)

- Calibrate spring constant using thermal tuning method before measurements

- Program AFM to acquire force curves from adjacent patterned regions in interleaved sequence

- Maintain consistent loading rate (e.g., 40 pN/s for protein unfolding studies)

- Acquire minimum of 100-200 force curves per sample condition for statistical power

Orthogonal Fingerprinting Analysis:

- For single-molecule studies: identify specific unfolding patterns or contour lengths

- For cellular measurements: utilize distinct mechanical signatures (e.g., adhesion, creep)

- Compute mean unfolding forces or stiffness values for each condition within the same experiment:

- $\Delta \left\langle {F{\mathrm{u}}} \right\rangle = \left\langle {F{\mathrm{u}}} \right\rangle{\text{sample A}} - \left\langle {F{\mathrm{u}}} \right\rangle_{\text{sample B}}$

- Determine statistical significance using appropriate tests (e.g., t-test for normally distributed data)

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment:

- Compare inter-experimental vs. intra-experimental variability

- Calculate relative standard deviation (RSD) improvement factor

- Report calibration uncertainty (CU) contribution to total measurement error

Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Experiments

Successful validation requires specific reagents and materials designed for AFM biomechanics. The following table details essential solutions for implementing the validation protocols described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AFM Stiffness Validation

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Specific Function in Validation | Key Technical Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS-Series Calibration Standards | BudgetSensors [17] | Z-axis calibration reference | Step heights: 20nm, 100nm, 500nm with 2-3% height accuracy | Essential for initial system calibration before biological measurements |

| X-Y Cross Grating Replica | Ted Pella [17] | Lateral calibration standard | 2000 lines/mm, 500 nm pitch | Validates scanner accuracy in X and Y dimensions |

| Tip Characterization Specimen | BudgetSensors [17] | AFM tip condition monitoring | Cobalt particles (1-5nm height) for tip sharpness assessment | Critical for identifying tip wear that affects mechanical measurements |

| Cytoskeletal Disruption Agents | Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris | Specific perturbation of cellular mechanics | Cytochalasin B (5 μM final concentration) [16] | Positive control for stiffness tomography validation |

| Functionalization Reagents | Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Fisher | Sample attachment for concurrent measurements | Biotin-PEG-NHS, maleimide groups for specific coupling [18] | Enables patterned surfaces for concurrent force spectroscopy |

| HaloTag Ligands | Promega | Specific protein attachment for single-molecule studies | Covalent binding to HaloTag fusion proteins [18] | Provides specific attachment for protein mechanical studies |

Integrated Validation Workflow Diagram

The comprehensive validation of AFM stiffness measurements requires an integrated approach that combines multiple techniques throughout the experimental workflow. The following diagram illustrates how these methods interconnect to establish measurement credibility.

The establishment of ground truth in AFM stiffness measurements requires more than occasional validation—it demands a systematic, integrated approach that permeates every stage of experimental design and execution. As the data in this guide demonstrates, even seemingly minor factors such as sample tilt, tip condition, or calibration drift can significantly impact measured mechanical properties, potentially leading to biologically incorrect conclusions [4] [18].

Successful implementation of the validation frameworks described here enables researchers to transform AFM from a qualitative imaging tool into a quantitative biomechanical characterization platform. By adopting stiffness tomography, researchers can detect subsurface structures that would otherwise invalidate homogeneity assumptions [16]. Through concurrent force spectroscopy, laboratories can control for calibration uncertainties that plague comparative studies [18]. And by integrating finite element modeling with experimental measurements, scientists can bridge the gap between simplified contact models and complex biological reality [12].

In the evolving landscape of biomedical research, where mechanical properties increasingly serve as diagnostic and therapeutic indicators, the non-negotiable requirement for validation becomes both a scientific imperative and an ethical responsibility. The protocols, reagents, and comparative data presented in this guide provide a concrete pathway toward achieving this standard of excellence, ensuring that AFM-derived mechanical properties truly reflect biological reality rather than methodological artifact.

Advanced AFM Methodologies and Integrated Workflows for Robust Data Acquisition

Force-Volume Mapping and Nano-DMA for Spatially-Resolved Viscoelasticity

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has become the dominant technique for characterizing mechanical properties at the nanoscale, with particular significance for soft materials, polymers, and biological systems [1]. Among AFM-based techniques, Force-Volume mapping and nanoscale Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (nano-DMA) have emerged as powerful, complementary methods for spatially-resolved viscoelastic property mapping. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, focusing on their operational principles, performance characteristics, and experimental validation within the broader context of AFM stiffness measurement verification.

The accuracy of AFM nanomechanical measurements has advanced significantly through improved probe calibration, contact mechanics models, and correction factors for common artifacts [5] [4] [20]. These developments enable researchers to obtain quantitative property data that can be correlated with bulk characterization techniques, providing crucial validation of nanoscale measurements.

Technical Comparison: Operational Principles and Performance Characteristics

Force-Volume mapping and nano-DMA differ fundamentally in their acquisition strategies and the type of viscoelastic information they provide. The table below summarizes their key characteristics:

Table 1: Technical comparison between Force-Volume mapping and nano-DMA

| Characteristic | Force-Volume Mapping | AFM-based Nano-DMA |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Records complete force-distance curves at each pixel [1] | Applies oscillatory indentation at specific frequencies during force curve contact segment [1] [21] |

| Primary Mechanical Outputs | Young's modulus, adhesion, deformation [20] | Storage modulus (E'), loss modulus (E"), loss tangent (tan δ) [21] |

| Acquisition Speed | Slow to moderate (improved with FASTForce Volume) [20] | Very slow for frequency sweeps; moderate for single-frequency mapping [21] |

| Spatial Resolution | <10 nm demonstrated [22] | ~10 nm demonstrated [21] |

| Frequency Range | Limited by approach/retract cycle [1] | 0.1 - 100 Hz (rheologically relevant) [21] |

| Best Applications | High-resolution elasticity mapping, adhesive properties, heterogeneous materials [22] [23] | Quantitative viscoelastic spectroscopy, time-temperature superposition, polymer phases [21] |

| Key Limitations | Indirect viscoelasticity from hysteresis [1] | Slow acquisition, especially for full frequency spectra [21] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Force-Volume Mapping Protocol

Force-Volume mapping generates nanomechanical property maps by acquiring force-distance curves (FDCs) in each pixel of the sample surface [1]. The following workflow outlines a standardized protocol for reliable data acquisition:

Cantilever Selection and Calibration: Select probes with appropriate spring constants for the sample stiffness. Use pre-calibrated probes with controlled tip geometry (e.g., spherical tips with 30 nm radius) when possible [20]. Calibrate the deflection sensitivity via thermal tune or force curve on a rigid reference sample (e.g., sapphire) [20].

Sample Preparation: For soft biological tissues, cryosectioning (e.g., 16 μm thick sections) onto glass slides is effective. Wash away optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound with PBS and maintain hydration during measurements [23].

Data Acquisition Parameters: Define a measurement grid (e.g., 4×4 to 128×128 points). Set approach/retract velocity and maximum force to ensure reversible deformation without permanent sample damage [1] [23]. Utilize high-speed implementations (FASTForce Volume) for improved throughput—128×128 maps in ~3 minutes versus ~30 minutes conventionally [20].

Data Analysis and Model Fitting: Convert deflection versus Z-piezo position data to force versus indentation curves. Fit retraction curves with appropriate contact mechanics models (Hertz, DMT, JKR) to extract Young's modulus and adhesion [20]. Apply bottom-effect corrections for thin samples like cells to account for substrate stiffness artifacts [5].

Nano-DMA Experimental Protocol

AFM-based nano-DMA measures viscoelastic properties by applying a small oscillatory modulation to the tip while in contact with the sample and analyzing the mechanical response [1] [21]. The standardized protocol is as follows:

Probe and Sample Preparation: Similar to Force-Volume, but particular attention must be paid to using tips with well-defined geometry (e.g., spherical probes) for accurate contact area calculation [21]. Ensure sample is mechanically stable for long measurement times.

Initial Engagement and Preload: Approach the tip to a predefined setpoint force (1-20 nN) to establish a contact indentation, Iâ‚€ (typically 100-500 nm) [1]. Apply a force-hold segment to allow for material relaxation and mitigate creep before modulation begins [21].

Oscillatory Modulation: Apply a sinusoidal Z-piezo motion,

z(t) = Zâ‚sin(ωt + ψ), at a single frequency or a sequence of frequencies (0.1-100 Hz) [21]. The modulation force must be significantly smaller than the preload to ensure measurement occurs within the linear viscoelastic regime [21].Response Detection and Analysis: Measure the cantilever's oscillatory response,

d(t) = Dâ‚sin(ωt + φ). Calculate the complex dynamic stiffness, S, from the amplitude ratio (Dâ‚/Zâ‚) and phase shift (φ - ψ) [21]. Convert S to complex modulus (E* = E' + iE") using the appropriate contact mechanics model and contact radius [21].

Validation and Correlation with Complementary Techniques

A critical aspect of nanomechanical analysis is validating AFM-derived data against established bulk characterization methods and correcting for common measurement artifacts.

Correlation with Bulk DMA

AFM-nDMA provides excellent correlation with conventional dynamic mechanical analysis when proper measurement protocols are followed. A key study demonstrated this correlation on a tri-polymer blend:

Table 2: Comparison of AFM PeakForce QNM and DMA modulus values for a polymer blend

| Polymer Component | AFM (PeakForce QNM) Modulus (MPa) | Bulk DMA (Time-Temperature Superposed) (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene (PP) | 32 ± 5 | ~32 [20] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | 45 ± 7 | ~43 [20] |

| Polyethylene (PE) | 18 ± 3 | ~30 [20] |

The data shows excellent agreement for PP and PS, while the lower value for PE may be attributed to higher adhesion complicating the modeling or processing effects on the PE phase [20]. This validation is crucial for establishing confidence in nanomechanical measurements.

Essential Correction Factors for Accurate Measurements

Several correction factors must be applied to ensure quantitative accuracy in AFM stiffness measurements:

Bottom- Stiffness Effect: For thin samples like cells, the rigid substrate artificially increases apparent stiffness. Bottom-effect correction models must be applied, as demonstrated by measurements on HeLa cells where the apparent modulus increased with force without correction, but remained constant when proper finite-thickness models were used [5].

Sample Tilt Compensation: Inclined surfaces violate the assumption of perpendicular indentation in classical Hertz-Sneddon models. Incorporation of tilt-dependent correction factors significantly improves measurement accuracy on non-planar surfaces, as validated on tilted polyacrylamide gels [4].

Probe Geometry and Calibration: Pre-calibrated probes with controlled tip geometry (e.g., 30 nm radius spherical tips) eliminate significant variability in modulus calculations, enabling "out-of-the-box" quantitative measurements without reference samples [20].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and reagents required for implementing these techniques:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for Force-Volume and nano-DMA

| Item | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Probes | Nanomechanical transducers | Pre-calibrated spherical tips (e.g., 30 nm radius, 0.25-200 N/m spring constants); sharp tips for highest resolution [20] |

| Calibration Samples | System verification | Rigid reference (screened sapphire); polymer standards (PS, LDPE) with known modulus [20] |

| Cell Culture Substrates | Mechanobiology studies | Glass or plastic Petri dishes; tunable stiffness hydrogels [5] |

| Tissue Preservation Media | Biological sample preparation | Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound for cryosectioning [23] |

| Buffer Solutions | Physiological environment | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) for hydrated biological measurements [23] |

| Analysis Software | Data processing | Advanced fitting algorithms (DMT, JKR, power-law rheology); bottom-effect corrections [5] [20] |

Force-Volume mapping and nano-DMA provide complementary approaches for nanomechanical characterization, each with distinct advantages for specific applications. Force-Volume excels in high-resolution elasticity and adhesion mapping, while nano-DMA offers quantitative viscoelastic spectroscopy at rheologically relevant frequencies. Recent advances in probe technology, calibration protocols, and correction models have significantly improved the quantitative accuracy of both techniques, enabling direct correlation with bulk measurements. The continued development of standardized protocols and validation frameworks will further enhance the reliability and adoption of these powerful nanomechanical mapping techniques across materials science and biological research.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has become a cornerstone technique in mechanobiology, enabling the nanoscale characterization of mechanical properties crucial for understanding cellular functions, disease states, and tissue engineering. However, measuring the mechanical properties of intact, heterogeneous soft tissues presents significant challenges due to their complex composition and structural diversity. This guide examines the novel pipeline of AFM force mapping on tissue cryosections as a solution to these challenges, comparing its performance with alternative methodologies and providing validated experimental data to guide researcher selection.

AFM's dominance in soft matter and biological research stems from its exceptional spatial resolution, force sensitivity, and ability to operate under physiological conditions [4]. While extensively used for cultured cells, its application to native tissues has been limited, primarily because tissues contain a heterogeneous mix of cell types and extracellular matrix (ECM) components, making it difficult to locate specific regions of interest and interpret mechanical data [23]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the cryosection force mapping approach against alternative techniques, providing a framework for researchers to select the most appropriate method for their investigative needs.

Methodological Comparison: Addressing Heterogeneity in Soft Tissues

The fundamental challenge in soft tissue mechanobiology is capturing meaningful mechanical data from a spatially complex environment. Traditional approaches often fail to account for this heterogeneity, leading to potential mischaracterization. The table below compares the primary techniques available for measuring the mechanical properties of soft tissues.

Table 1: Comparison of Techniques for Soft Tissue Nanomechanics

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Throughput | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryosection AFM Force Mapping | Nanoscale (vertical <0.1 nm, lateral ~1 nm) [24] | Medium (16-256 points/map) [23] | Accesses specific anatomical regions; accounts for heterogeneity | Snap-freezing may alter native state | Mapping mechanical heterogeneity in complex tissues (e.g., optic nerve head) [23] |

| Nanoindentation | Micron-scale [25] | Low (requires extensive statistical analysis) [25] | Well-established for hard biomaterials | Small probed area is unrepresentative; limited by indenter size [25] | Homogeneous tissues or large, uniform regions |

| Microfluidics/Deformability Cytometry | Single-cell | Very High (thousands of cells/hour) [26] | Exceptional throughput for cell suspensions | Requires dissociated cells; loses tissue context [26] | Blood cells or dissociated cell suspensions |

| Elastography (e.g., MRE) | Millimeter-scale [27] | High (full organ scans) | Non-invasive; clinical application | Poor resolution for micro-scale features [27] | Clinical assessment of whole-organ stiffness (e.g., liver fibrosis) |

| Deep Learning Image Analysis | Single-cell | Very High [26] | Non-invasive; uses simple bright-field images | "Black box" model; requires AFM training data [26] | High-throughput screening when trained on reliable mechanical data |

The Cryosection Force Mapping Pipeline: A Detailed Protocol

The cryosection force mapping pipeline is designed to provide spatially resolved, robust mechanical data from specific tissue regions. The following workflow and detailed protocol are adapted from studies on rodent optic nerve head, trabecular meshwork, cornea, and sclera [23].

Sample Preparation and Mounting

- Tissue Harvest and Snap-Freezing: Euthanize the animal according to approved animal care protocols. Carefully enucleate the target organ (e.g., eyes for optic nerve head studies) and immediately embed them in an optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound. Snap-freeze the embedded tissue in 2-methylbutane cooled by liquid nitrogen. Store samples at -80°C [23].

- Cryosectioning: Using a cryostat (e.g., CryoStar NX70), prepare sagittal sections of a defined thickness (e.g., 16 µm) through the region of interest. This specific thickness is chosen to mitigate potential substrate effects from deep indentation while ensuring the section adheres to the slide. Mount sections on Superfrost Plus Gold slides and allow them to dry. Store slides at -80°C [23].

- AFM Preparation: Prior to AFM measurements, thaw the samples and submerge them in PBS for at least 10 minutes at 4°C to wash away the OCT compound. Perform all AFM measurements with the sample submerged in room-temperature PBS to maintain tissue hydration [23].

AFM Force Map Acquisition

- Probe Selection: Use a spherical borosilicate glass probe (e.g., 10 µm diameter) attached to a soft, V-shaped silicon nitride cantilever (nominal spring constant of 0.01 N/m). Spherical probes are preferred for their well-defined contact mechanics and reduced stress concentration, which is critical for soft samples [23].

- Calibration: Calibrate the cantilever's spring constant using the thermal noise method [23].

- Force Mapping: Program the AFM to acquire a raster-scan of force-distance curves over a defined area (e.g., a 40 x 40 µm area in a 4 x 4 or 16 x 16 grid). Each force curve consists of an approach and retraction cycle. The approach velocity should be optimized to balance hydrodynamic forces and data acquisition time (e.g., 2 µm/s) [23].

Data Processing and Analysis

- Contact Point and Curve Analysis: Determine the point of contact between the probe and the sample for each force-distance curve. Fit the indentation segment of the approach curve with an appropriate contact mechanics model.

- Outlier Exclusion and Data Transformation: Implement a data processing pipeline that includes the exclusion of outliers and log-normal transformation of the calculated Young's modulus values. This step increases the robustness of the estimates from heterogeneous tissue data [23].

Model Fitting - The Hertz Model: For soft, biological materials, the Hertz model is the most reliable choice [27]. The model calculates the effective Young's modulus (Eff) as follows:

(Eff = \frac{P \cdot 3/4}{\sqrt{R} \cdot h_t^{3/2}})

where P is the load at the peak of the fit, R is the tip radius, and h_t is the indentation depth [27]. A Poisson's ratio of 0.5 is typically assumed for perfectly incompressible materials.

Performance Data and Model Validation

The reliability of the cryosection AFM pipeline is demonstrated by its performance against alternative analysis models and its ability to generate consistent results across different tissue types.

Table 2: Reliability of Mechanical Models on Soft Biomaterials (Data from [27])

| Biological Sample | Hertz Model | JKR Model | Oliver & Pharr Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matrigen Hydrogels | ICC >0.8, COV <15% | ICC >0.8, COV <15% | ICC >0.8, COV <15% |

| Kidney | ICC >0.8, COV <15% | ICC <0.8, COV >15% | ICC <0.8, COV >15% |

| Liver | ICC >0.8, COV <15% | ICC <0.8, COV >15% | COV <15%, ICC inconsistent |

| Spleen | ICC >0.8, COV <15% | ICC >0.8, COV >15% | ICC <0.8, COV >15% |

| Uterus | ICC >0.8, COV <15% | ICC <0.8, COV >15% | ICC >0.8, COV >15% |

ICC: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient; COV: Within-Subject Coefficient of Variation

Validation studies on mouse and rat tissues confirm the pipeline's utility. The method has been successfully applied to the mouse glial lamina, a region consisting of astrocytes and retinal ganglion cell axons, revealing its heterogeneous mechanical landscape. Furthermore, the technique has been extended to other soft tissues, including the rat trabecular meshwork, cornea, and sclera, demonstrating its broad applicability [23].

Advanced Considerations and Pitfalls

Accounting for the Bottom Stiffness Effect

A critical consideration when performing AFM on thin samples is the bottom stiffness effect. This artifact occurs when the compressive stress from the AFM tip propagates through the cell or tissue section and is reflected by the underlying stiff substrate (e.g., glass slide), causing the sample to appear stiffer than it truly is [5]. The effect is parameterized by the ratio of the tip-cell contact area radius to the sample height [5].

Solution: For accurate results, especially with tips of large effective radius (R ≥ 1 µm) or on thin regions of a sample, finite-thickness (bottom-effect) correction models should be used instead of standard semi-infinite models [5]. Experimental evidence shows that using a semi-infinite model gives an apparent modulus that increases with applied force—an artifact that disappears when a finite-thickness model is applied [5].

Correcting for Surface Topography

Another common source of error is non-perpendicular indentation on inclined or curved sample surfaces, which violates a key assumption of the Hertz model [4].

Solution: New theoretical models incorporate correction coefficients into Hertz's model for cone-like and spherical probes to account for local tilt at the probe-sample interface. Finite element analysis and experiments on tilted polyacrylamide gels have validated this approach, highlighting the need for such corrections to ensure accurate AFM measurements on non-planar biological surfaces [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details the key materials and reagents required to implement the cryosection force mapping pipeline successfully.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Cryosection AFM

| Item | Specification/Example | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cryostat | ThermoFisher CryoStar NX70 | Produces thin, uniform tissue sections for analysis. |

| Microscope Slides | Superfrost Plus Gold (Fisher) | Provides superior adhesion for tissue sections during AFM. |

| AFM System | MFP-3D (Asylum Research) | Instrument for acquiring force-distance curves and topography. |

| Spherical AFM Probe | 10 µm diameter borosilicate (Novascan) | Defined geometry for reliable mechanical modeling; soft cantilever (0.01 N/m). |

| Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) Compound | Standard OCT (e.g., Tissue-Tek) | Embedding medium for snap-freezing and cryosectioning. |

| Buffer | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Maintains tissue hydration and ionic balance during AFM testing. |

| d-Lyxono-1,4-lactone | d-Lyxono-1,4-lactone, CAS:15384-34-6, MF:C₅H₈O₅, MW:148.11 | Chemical Reagent |

| Drimentine B | Drimentine B, CAS:204398-91-4, MF:C31H39N3O2, MW:485.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This comparison guide outlines a robust and validated pipeline for nanomechanical characterization of heterogeneous soft tissues via AFM force mapping on cryosections. When compared to alternative techniques, this method offers a unique balance of nanoscale resolution and the ability to target specific anatomical structures within complex tissues. Key performance data demonstrates that the Hertz model provides the most reliable analysis for soft, biological materials, and the integration of protocols for outlier handling and data transformation ensures robust results. By accounting for potential artifacts like the bottom stiffness effect and sample topography, researchers can leverage this pipeline to generate highly accurate mechanical property maps, advancing our understanding of tissue mechanobiology in health and disease.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has become a cornerstone technique in materials and biological sciences for measuring nanomechanical properties. However, a significant challenge in the field is validating that the stiffness values obtained are accurate and not influenced by measurement artifacts. This guide frames the combination of AFM with Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) within the broader research thesis of validating AFM stiffness measurements. While traditional AFM analysis often relies on models like Hertz or Sneddon that assume perpendicular indentation on a planar sample, real-world samples like cells and tissues frequently violate these assumptions, potentially compromising accuracy [4]. Correlative AFM-SIM microscopy addresses this validation challenge by providing simultaneous mechanical property measurement and high-resolution molecular localization, enabling researchers to distinguish true mechanical properties from measurement artifacts and understand their biological context.

Technology Comparison: AFM-SIM Versus Alternative Correlative Approaches

Various microscopy techniques have been integrated with AFM to provide correlative data. The table below compares AFM-SIM with other common AFM-based correlative microscopy platforms.

Table 1: Performance comparison of AFM-SIM with other correlative microscopy techniques

| Technique | Resolution (Optical) | Simultaneous Imaging | Sample Requirements | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFM-SIM | ~100-120 nm (2x diffraction limit) [28] | Yes [28] | Standard fluorophores; no special buffers [28] | Live-cell compatible, lower phototoxicity [28] | Moderate resolution improvement compared to other SR techniques [28] |

| AFM-STORM | ~20-30 nm [28] | Challenging (requires buffer exchange) [28] | Fluorophores with blinking behavior; special imaging buffer [28] | Excellent spatial resolution | Buffer can interfere with AFM cantilever operation [28] |

| AFM-STED | ~30-80 nm [28] | Possible with limitations [28] | Standard fluorophores | Good resolution with standard fluorophores | High-powered depletion laser can damage AFM cantilevers [28] |

| AFM-Confocal | ~200-250 nm (diffraction-limited) | Yes [28] | Standard fluorophores | Widely available, easy implementation | Diffraction-limited resolution |

| AFM-TIRFM | ~200-250 nm (diffraction-limited) [28] | Yes [28] | Requires proximity to interface | Excellent for cell-substrate interface studies | Limited to surface regions [28] |

AFM-SIM occupies a unique position in this technological landscape, offering a balanced compromise between resolution enhancement and practical experimental flexibility. Its capacity for simultaneous operation without specialized samples makes it particularly valuable for live-cell investigations where physiological conditions must be maintained.

Experimental Protocols: Implementing AFM-SIM for Stiffness Validation

System Configuration and Integration

The combined AFM-SIM platform detailed by researchers integrates an atomic force microscope (such as a JPK NanoWizard 3) mounted on an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti2-E) with a structured illumination microscope (Nikon N-SIM E) [28]. The critical integration points include:

- Optical Path: SIM illumination is provided by laser light (488/561/640 nm) coupled into a multimodal fiber, with a diffraction grating creating the structured pattern [28].

- Detection System: Fluorescence is collected through a high numerical aperture objective (e.g., CFI SR APO TIRF 100× Oil, N.A. 1.49) and recorded with a sCMOS camera [28].

- AFM Compatibility: The system uses extra long working distance condensers to accommodate the AFM hardware above the sample [28].

For upright configurations used with thick tissue samples, the system incorporates Upright SIM (USIM) with AFM, enabling correlated stiffness maps and molecular distributions in three-dimensional living tissues [29].

Detailed Workflow for Simultaneous AFM-SIM Imaging

The experimental workflow for correlated AFM-SIM measurements involves multiple precisely coordinated steps:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for correlated AFM-SIM imaging

Sample Preparation: Biological samples (cells or tissues) are prepared according to experimental requirements. For live tissue measurements, samples are maintained in ex vivo culture conditions [29]. Fluorescent labeling of target structures is essential for SIM imaging.

Cantilever Selection and Calibration: Appropriate AFM probes are selected based on sample properties:

System Alignment: The AFM laser is aligned on the cantilever, and the SIM illumination is calibrated to ensure optimal pattern projection without interfering with AFM operation [28].

Simultaneous Data Acquisition:

- AFM Imaging: Operated in Quantitative Imaging (QI) mode for simultaneous topography and nanomechanical mapping. Typical parameters include Z-velocity of 250 μm/s and maximum Z-length of 1.5 μm [28].

- SIM Acquisition: Capturing 15 raw images with different pattern orientations (5 phase shifts × 3 rotations) with exposure times around 700 ms per frame [28].

Image Processing and Correlation:

- SIM images are reconstructed using computational methods (e.g., NIS-Elements software) [28].

- Stiffness values from AFM are correlated with molecular distributions from SIM using spatial alignment algorithms.

Validation Experiments and Key Parameters

To validate AFM stiffness measurements using SIM correlation, several experimental approaches have been developed:

Table 2: Key experimental parameters for AFM-SIM stiffness validation studies

| Experimental Parameter | Cell Mechanics Study | Tomechanical Analysis | Bead Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFM Mode | Quantitative Imaging (QI) [28] | Force-volume mapping [29] | Force modulation [28] |

| Cantilever Type | qp-BioAC-CI-CB1 (0.3 N/m) [28] | Not specified | FM (2.8 N/m) [28] |

| SIM Resolution | ~120 nm [28] | ~100-120 nm [29] | ~120 nm [28] |

| Key Measurements | Elastic modulus correlated with membrane protein localization [28] | Spatial correlation of stiffness with collagen distribution [29] | System alignment verification [28] |

| Sample Type | Human bone osteosarcoma epithelial cells [28] | Mouse embryonic and adult skin [29] | Sub-resolution fluorescent beads [28] |

Technical Specifications and System Components

Successful implementation of AFM-SIM requires specific technical components optimized for correlated imaging:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and solutions for AFM-SIM experiments

| Component Category | Specific Product/Model | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| AFM System | JPK NanoWizard 3 [28] | Provides nanomechanical mapping capability |

| Inverted Microscope | Nikon Eclipse Ti2-E [28] | Platform for system integration |

| SIM Module | Nikon N-SIM E [28] | Enables super-resolution fluorescence imaging |

| Detection Camera | Hamamatsu Orca Flash4.0 sCMOS [28] | Captures SIM raw data |

| Objective Lens | CFI SR APO TIRF 100× Oil, N.A. 1.49 [28] | High-resolution fluorescence collection |

| AFM Cantilevers | qp-BioAC-CI-CB1 (cells), FM (beads) [28] | Measures force interactions with sample |

| Cell Line | EGFP-MCT1 expressing human cells [28] | Model system for method validation |

Research Applications and Validation Outcomes

Stiffness Validation in Cellular Systems

In studies using human bone osteosarcoma epithelial cells expressing EGFP-tagged MCT1 plasma membrane transporter, AFM-SIM enabled direct correlation between local stiffness variations and specific molecular markers. This approach helped validate that measured stiffness differences corresponded to genuine mechanical properties rather than topographic artifacts [28]. The simultaneous nature of the measurement ensured that mechanical and molecular data originated from identical sample regions and temporal conditions, significantly strengthening validation conclusions.

Tissue-Scale Mechanobiology

The USIM-AFM configuration has been applied to mouse embryonic and adult skin tissues, revealing highly heterogeneous mechanical patterns correlated with cellular and extracellular components. This approach validated that stiffness variations observed in AFM directly corresponded to specific tissue structures identified by SIM, including nucleated/enucleated epithelium, mesenchyme, and hair follicles [29]. Furthermore, quantitative analysis comparing live versus preserved tissues uncovered significant impacts of preservation processes on mechanical properties, highlighting the importance of live measurements for accurate stiffness validation [29].

Addressing AFM Measurement Artifacts

The correlation with SIM provides critical validation for AFM stiffness measurements by addressing common artifacts:

- Bottom Stiffness Effect: AFM indentation on thin samples like cells can be influenced by the underlying substrate stiffness, making cells appear stiffer than they truly are [5]. SIM imaging of cell height and organization helps identify measurements potentially compromised by this effect.

- Sample Tilt Artifacts: Inclined surfaces can lead to inaccurate stiffness measurements if uncorrected [4]. SIM topography provides independent validation of local surface orientation.

- Spatial Registration: Molecular localization via SIM ensures mechanical properties are correctly assigned to specific cellular or extracellular structures [29].