Visualizing Dynamic Biofilm Processes: How High-Speed AFM is Revolutionizing Microbiology and Drug Development

This article explores the transformative role of High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy (HS-AFM) in visualizing the dynamic processes of biofilm formation and behavior in real-time.

Visualizing Dynamic Biofilm Processes: How High-Speed AFM is Revolutionizing Microbiology and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy (HS-AFM) in visualizing the dynamic processes of biofilm formation and behavior in real-time. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of HS-AFM, detailing its capability to capture nanoscale structural and functional changes at sub-second resolution under physiological conditions. The content provides a methodological guide for application, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and offers a comparative analysis with other biomechanical characterization techniques. By synthesizing the latest research and technical advances, this article serves as a comprehensive resource for leveraging HS-AFM to develop novel anti-biofilm strategies and therapeutics.

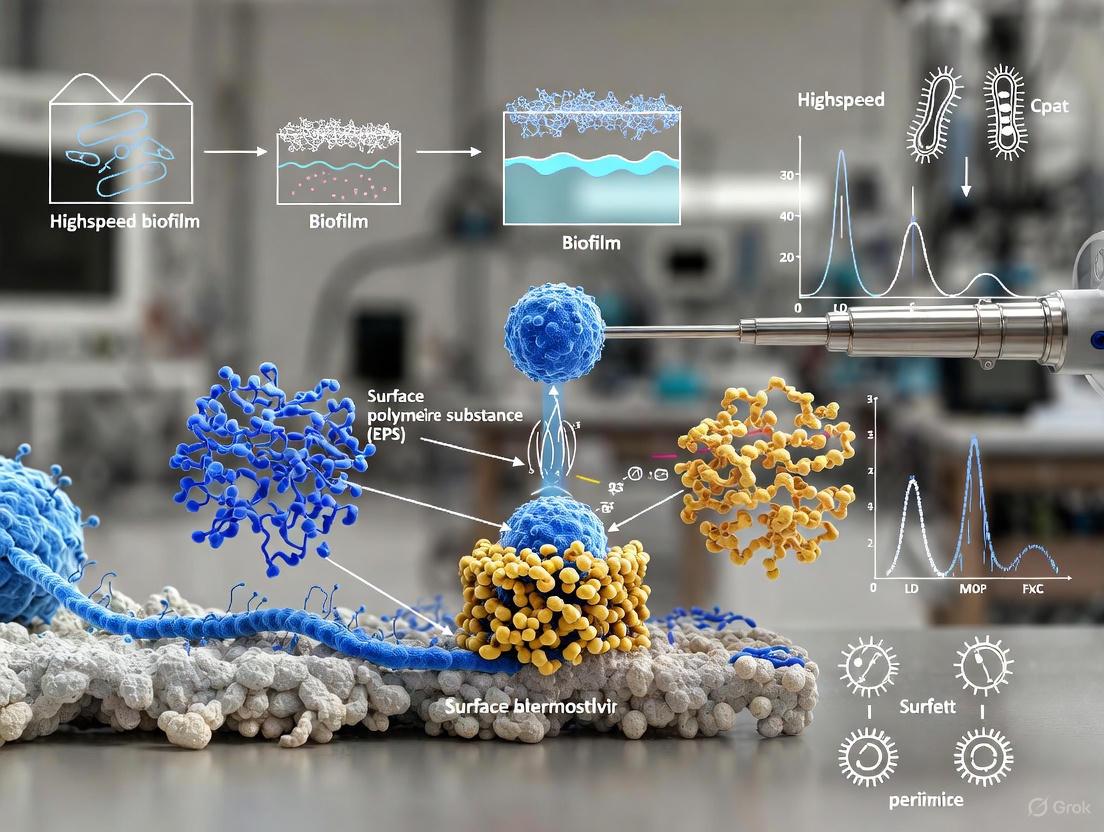

Unveiling the Biofilm Lifecycle: Foundational Principles of High-Speed AFM Imaging

Biofilms are complex, three-dimensional microbial communities encased in a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Their remarkable resilience and multifaceted functions stem from intricate microbial interactions, including enhanced substrate metabolism, energy conversion, cellular communication, and horizontal gene transfer [1]. However, this complexity also presents a significant research challenge: biofilms are inherently heterogeneous and dynamic, characterized by spatial and temporal variations in structure, composition, density, and metabolic activity [2]. These variations are influenced by microbial species, environmental conditions, surface properties, and microbial interactions, all of which contribute to biofilm stability and resilience [2].

Traditional imaging technologies face fundamental obstacles in capturing this dynamic complexity. Conventional methods, including Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM), and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), often involve labor-intensive data acquisition, complex analysis workflows, low reproducibility, and limited throughput [1]. More critically, these methods frequently fall short in capturing the intricate spatial and functional dynamics of living biofilms and can introduce artifacts that compromise result fidelity [1]. The core issue is a mismatch in timescales; the rapid, transient processes of biofilm formation occur much faster than the acquisition speed of conventional, high-resolution imaging tools.

Limitations of Conventional Biofilm Imaging Methods

The limitations of traditional imaging techniques become starkly apparent when applied to the study of dynamic biofilm processes. A comparative analysis of their shortcomings is presented in the table below.

Table 1: Limitations of Traditional Imaging Techniques for Dynamic Biofilm Studies

| Imaging Technique | Key Limitations for Dynamic Studies | Impact on Biofilm Data Fidelity |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Small imaging area (<100 µm); Slow scanning process; Labor-intensive operation; Limited capture of dynamic structural changes [2]. | Inability to link nanoscale features to macroscale organization; Misses rapid, transient events in biofilm development. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) | Labor-intensive data acquisition; Limited throughput; Potential for photodamage during long-term imaging [1]. | Incomplete representation of rapid 3D architectural changes; Altered biofilm physiology due to light exposure. |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Requires sample dehydration and metallic coating; Complex preparation causes sample distortion and Eps collapse [3]. | Provides only static snapshots of fixed samples; non-physiological conditions preclude live, dynamic monitoring. |

| Raman Spectroscopy (RS) | Fluorescence interference; Low reproducibility; Requires high laser power risking photodamage [1]. | Hinders reliable, repeated measurements of chemical dynamics within living biofilms. |

A primary technical hurdle for conventional AFM is its limited scan range, which restricts the ability to link critical smaller-scale features—such as individual cell morphology and nanomechanical properties—to the emergent functional architecture of the biofilm at the macroscale [2]. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of biofilms, with their intricate networks of pores, channels, and cell clusters often falling below the resolution of conventional technologies, results in an incomplete representation of true biofilm morphology [1]. These limitations collectively underscore that traditional methods are ill-suited for observing biofilm processes as they unfold in real-time.

High-Speed and Automated AFM: A Paradigm Shift for Dynamic Analysis

Recent technological advancements are overcoming these historical barriers. The development of large area automated AFM represents a transformative approach, enabling the capture of high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas, a significant leap from the traditional sub-100µm range [2]. This innovation directly addresses the scale mismatch, allowing researchers to correlate cellular-level events with community-level organization.

Automation is a critical component of this new paradigm. Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are now being integrated to automate the scanning process, including sample region selection, scanning optimization, and probe conditioning [2]. This AI-driven automation minimizes user intervention, allowing for continuous, multi-day experiments and overcoming the labor-intensive nature of traditional AFM operation [2]. The application of deep learning algorithms, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for image segmentation and generative adversarial networks for image reconstruction, effectively enhances resolution, reduces artifacts, and captures precise spatiotemporal biofilm architecture previously unattainable [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Capabilities of Advanced AFM Modalities for Biofilm Research

| AFM Modality | Key Quantitative Outputs | Application in Dynamic Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| High-Speed/Large-Area AFM | Cell count, confluency, cell shape/orientation over mm² areas [2]. | Tracking early bacterial adhesion patterns and cluster formation in real-time. |

| Force Spectroscopy | Adhesion forces (nN), elastic moduli (Young's modulus), turgor pressure [4]. | Mapping spatiotemporal variations in biofilm mechanical properties during treatment. |

| Tapping Mode in Liquid | Topographical height (nm), surface roughness (Rq), phase imaging for material contrast [4]. | In-situ, non-destructive 3D visualization of hydrated biofilm matrix development. |

These advanced AFM modalities facilitate a multiparametric investigation. Force spectroscopy allows for the measurement of interaction forces between biomolecules and nanomechanical properties like stiffness, which influence antimicrobial penetration and biofilm removal [3]. When combined with the ability to operate in liquid under physiological conditions, these new AFM platforms enable a non-invasive, quantitative, and comprehensive analysis of living biofilms, from initial attachment to mature community responses to environmental stresses.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm AFM

Successful high-speed AFM imaging of dynamic biofilms relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials for sample preparation and analysis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for High-Speed AFM Biofilm Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| PFOTS-treated Glass | Creates a hydrophobic surface to promote and study controlled bacterial adhesion for early attachment studies [2]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Stamps | Microfabricated stamps with specific pit dimensions (1.5–6 µm) for secure, organized mechanical immobilization of microbial cells [4]. |

| Poly-L-Lysine | A chemical immobilization agent that promotes electrostatic binding of cells to substrates like mica or glass [4]. |

| Osmium Tetroxide (OsOâ‚„) | A staining and fixation agent used in sample preparation protocols to preserve lipid structures and enhance SEM/AFM image quality [3]. |

| Ruthenium Red (RR) & Tannic Acid (TA) | Used in customized staining protocols to specifically stabilize and visualize the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix [3]. |

| Ionic Liquid (IL) Treatment | Applied to samples to enhance electrical conductivity, reducing charging artifacts in SEM and enabling higher-resolution imaging without metal coating [3]. |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | A gram-negative, motile model bacterium with peritrichous flagella, ideal for studying the role of appendages in early biofilm assembly [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: High-Speed AFM for Early Biofilm Assembly

Objective: To visualize and quantify the initial attachment and organization of bacterial cells on a surface using automated large-area AFM.

Materials:

- Bacterial strain (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343) [2].

- Growth medium appropriate for the selected strain.

- PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or PDMS immobilization stamps [2] [4].

- Atomic Force Microscope with large-area scanning capability and an appropriate liquid cell.

- Fluidic system for inoculation and rinsing.

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Prepare PFOTS-treated glass coverslips to create a standardized hydrophobic surface for bacterial attachment [2].

- Sample Inoculation: Place the prepared coverslip in a Petri dish and inoculate with bacterial cells suspended in a liquid growth medium.

- Controlled Incubation: Incubate the sample for a selected, short time period (e.g., ~30 minutes) to allow for initial cell attachment [2].

- Gentle Rinsing: Carefully remove the coverslip from the Petri dish and gently rinse with a buffer solution to remove non-adherent planktonic cells.

- AFM Mounting: Securely mount the rinsed sample in the AFM liquid cell, ensuring it is fully hydrated in buffer to maintain physiological conditions.

- Automated Large-Area Scanning:

- Program the AFM to automatically acquire multiple high-resolution images across a millimeter-scale area of interest.

- Utilize machine learning algorithms for optimal site selection and scanning parameter adjustment [2].

- Image Stitching and Analysis:

- Apply computational stitching algorithms to reconstruct a seamless, high-resolution map of the entire scanned area.

- Use machine learning-based image segmentation to automatically detect cells, classify features, and extract quantitative parameters (e.g., cell count, confluency, cell orientation, flagellar presence) [2].

Diagram 1: High-Speed AFM Workflow for Early Biofilm Assembly

The critical need for speed in biofilm imaging is unequivocally addressed by the advent of high-speed and automated AFM technologies. By overcoming the fundamental limitations of traditional imaging—specifically small scan areas, slow acquisition rates, and labor-intensive operation—these advanced methods unlock the potential to observe and quantify the dynamic processes of biofilm formation and adaptation in real-time. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is pivotal, transforming AFM from a manual, single-image tool into an automated, quantitative platform capable of millimeter-scale analysis.

The future of dynamic biofilm research lies in the continued integration of these high-speed imaging capabilities with other multimodal data streams. Combining the nanoscale topographical and mechanical data from AFM with the chemical information from techniques like Raman spectroscopy, all underpinned by AI-driven analysis, promises a holistic and systems-level understanding of biofilm biology. This powerful synergy will ultimately accelerate the development of targeted interventions to control problematic biofilms across medical, industrial, and environmental contexts.

High-speed atomic force microscopy (HS-AFM) has emerged as a transformative tool for directly observing dynamic biological processes at the nanoscale, including the assembly and remodeling of biofilms, in near-physiological conditions. Unlike conventional AFM, HS-AFM captures data at sub-second to second temporal resolution, enabling researchers to visualize molecular and cellular dynamics in real-time. This capability is particularly valuable for studying biofilm development, where structural changes occur over timescales ranging from milliseconds to hours. The performance of an HS-AFM system hinges on three critical components: miniaturized cantilevers that enable fast response times, high-speed scanners that facilitate rapid tip positioning, and sensitive detectors that accurately measure cantilever deflection. This application note details the core principles, specifications, and operational protocols for these components, with a specific focus on their application in dynamic biofilm research for drug development and antimicrobial strategy evaluation.

Core Component 1: Cantilevers

The cantilever is the primary force sensor in AFM and the most critical component for achieving high-speed imaging. Its physical properties directly determine the imaging speed, sensitivity, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

Traditional vs. Advanced Cantilever Designs

Conventional HS-AFM employs miniaturized beam-shaped cantilevers to achieve high resonant frequencies and low spring constants. However, further miniaturization of these beams faces a fundamental trade-off: as the cantilever becomes smaller to increase speed, the area available for laser reflection decreases, leading to a lower SNR [5].

A recent breakthrough, the seesaw cantilever, presents a paradigm shift in design. This architecture decouples the mechanical element (torsional hinges) from the laser-reflective element (a rigid board) [5]. The key advantages of this design are:

- Enhanced SNR: The reflective board can be optimized for laser reflection independent of the mechanical properties, leading to a superior signal-to-noise ratio [5].

- Independent Parameter Tuning: The stiffness is precisely tuned via the hinge dimensions (length, width, thickness), while the board size is optimized for optical detection and hydrodynamic drag [5].

- High Angular Sensitivity: The shortened distance between the tip and the hinges enhances sensitivity to tip-sample interactions [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional and Seesaw Cantilever Designs for HS-AFM

| Feature | Traditional Beam Cantilever | Seesaw Cantilever |

|---|---|---|

| Design Principle | Bending beam | Swinging board on torsional hinges |

| Key Limitation | Laser reflection area decreases with miniaturization, limiting SNR | More complex fabrication process |

| Laser Reflectivity | Coupled to beam dimensions; compromised in miniaturized versions | Decoupled; board can be optimized for high reflectivity |

| Stiffness Tuning | Adjusted via length, width, and thickness of the entire beam | Precisely tuned via the dimensions of the torsional hinges |

| Reported Performance | Soft and fast, but SNR is a limiting factor at extreme miniaturization | Surpasses best beam cantilevers in sensitivity; matches imaging performance [5] |

Cantilever Selection and Fabrication Protocol

Objective: To select and/or fabricate a high-speed cantilever suitable for imaging dynamic biofilm processes with high temporal and spatial resolution.

Materials:

- Cantilever Chips: Silicon or silicon nitride cantilevers. For seesaw prototypes, a larger silicon nitride cantilever body (e.g., 200 µm long, 30 µm wide, 0.4 µm thick) coated with 5 nm Ti and 40 nm Au can be used as a platform for fabrication [5].

- Fabrication System: Focused Ion Beam (FIB) milling system for prototyping seesaw cantilevers [5].

- Tip Growth System: Electron Beam Deposition (EBD) for growing high-aspect-ratio tips (~2.5 µm long) [5].

Procedure:

- Design Specification:

- Define target resonant frequency (typically > 1 MHz in liquid) and spring constant (typically 0.1-0.2 N/m for biological samples) based on imaging requirements.

- For seesaw cantilevers, determine the board dimensions (e.g., 5 µm x 10 µm or 5 µm x 5 µm) and hinge geometry (e.g., 1 µm long x 0.2 µm wide) to achieve desired mechanical properties [5].

FIB Milling Fabrication (for Seesaw Cantilevers) [5]:

- a. Initial Trench Milling: Use FIB to mill an inverted Î -shaped trench near the cantilever's supporting base.

- b. Second Trench Milling: Mill a second Π-shaped trench opposite the first, leaving a 1 µm x 1 µm gap that will form the torsional hinges.

- c. Material Removal: Mill lateral trenches toward the periphery of the silicon nitride plate, leaving a small bar for structural integrity.

- d. Final Release: Mill the remaining peripheral regions to release the top part, creating the free-standing seesaw cantilever.

Tip Integration:

- Using EBD, grow a sharp, high-aspect-ratio tip (~2.5 µm in length) at the distal periphery of the cantilever board. The tip should be placed centrally along the board's long axis [5].

Validation:

- Perform finite element analysis to simulate the oscillation behavior and resonant frequency.

- Characterize the final cantilever using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to verify dimensions and tip placement.

- Experimentally determine the resonant frequency and stiffness in the intended fluid environment.

Core Component 2: Scanners

High-speed scanners position the sample or the probe with nanometer precision at high velocities. Their performance is critical for minimizing image distortion and achieving high frame rates.

Scanner Technology and Nonlinear Compensation

Piezoelectric actuators (PEAs) are the standard for AFM scanners due to their high precision, fast response, and large actuation force [6]. However, their intrinsic nonlinear behaviors, primarily hysteresis and creep, pose significant challenges for accurate scanning, especially at high speeds. Hysteresis causes the scanner's displacement to depend on its previous motion, leading to distorted images [6].

Advanced control strategies are essential to mitigate these effects. While feedback control with position sensors is effective, it can be limited by sensor noise and actuator bandwidth. A promising alternative is model-based feedforward compensation, which uses a mathematical model to predict and cancel out the nonlinearities without requiring physical sensors [6].

Recent research demonstrates the efficacy of using a variant DenseNet-type neural network to model and compensate for PEA hysteresis. This approach uses skip connections to improve information flow, preventing the "vanishing gradient" problem in deep networks and achieving a remarkably low relative root-mean-square (RMS) error of less than 0.1% [6]. This method simplifies the modeling by using separate models for the scanner's forward and backward movements.

Table 2: Key Characteristics of a High-Speed Piezoelectric Scanner

| Parameter | Specification | Importance for HS-AFM |

|---|---|---|

| Scan Range (XY) | ~27 × 27 µm² | Determines the maximum imaging area per frame [6] |

| Resonant Frequency | As high as possible (e.g., >10 kHz) | Limits the maximum achievable scan speed |

| Hysteresis | Compensated to <0.1% RMS error | Critical for accurate spatial positioning and image fidelity [6] |

| Actuator Material | Lead Zirconate Titanate (PZT) Ceramic | Provides the piezoelectric effect for precise motion [6] |

| Control Strategy | DenseNet-type Neural Network Feedforward | Compensates for nonlinearities without position sensors, enabling high-speed operation [6] |

Protocol: Neural Network-Based Scanner Modeling

Objective: To create an accurate inverse hysteresis model of a piezoelectric scanner for high-precision, high-speed positioning.

Materials:

- Piezoelectric Scanner: A custom or commercial HS-AFM scanner with piezoelectric actuators (e.g., Thorlabs PK4FQP2 PEA) [6].

- High-Voltage Amplifier: Small signal bandwidth of >100 kHz.

- Displacement Sensor: Capacitive sensor (e.g., MicroSense 5504) with gauging module for measuring actual scanner displacement [6].

- Data Acquisition System: FPGA module (e.g., National Instruments PXI-7853R) for input/output control and data acquisition [6].

Procedure:

- Data Collection:

- Drive each axis of the XY scanner with triangular input signals of varying amplitudes (e.g., 25 V, 50 V, 75 V, 100 V).

- For each input trajectory, record the corresponding output displacement using the capacitive sensor. Collect a minimum of 1000 samples each for the forward and backward directions.

- Repeat the entire procedure multiple times (e.g., 20x) to reduce measurement error and ensure a robust dataset [6].

Model Construction:

- Implement a variant DenseNet-type neural network. Utilize skip connections to link non-adjacent layers, ensuring robust gradient flow during training.

- Construct two separate models: one dedicated to mapping the forward direction data and another for the backward direction.

Training and Validation:

- Split the collected data into training and testing sets (e.g., 80/20 split).

- Train the models to predict the input voltage required to achieve a desired displacement, effectively learning the inverse hysteresis.

- Validate model performance by comparing the scanner's actual displacement to the desired trajectory when the model is used for feedforward control. The target is to reduce the relative RMS error to below 0.1% [6].

Core Component 3: Detectors

The deflection detection system converts the minute motion of the cantilever into a measurable electrical signal. A high-bandwidth, low-noise detector is essential for resolving high-speed cantilever oscillations.

Optical Beam Deflection System

The optical beam deflection (OBD) system is the most widely used detection method. Its core components are a laser diode, a focusing lens, and a position-sensitive photodetector (PSPD) [7]. The principle of operation is as follows:

- A laser beam is focused onto the back of the cantilever.

- The reflected beam is directed onto a PSPD.

- Cantilever bending (deflection) or swinging (torsion) causes the position of the reflected laser spot on the PSPD to shift.

- The PSPD converts this positional change into a voltage signal proportional to the cantilever's motion [7].

The seesaw cantilever's design, with its large, rigid reflective board, provides a significant advantage in this system by offering a stable and optimized surface for laser reflection, thereby increasing the signal-to-noise ratio compared to miniaturized beam cantilevers [5].

Workflow: Integrated HS-AFM Imaging of Biofilm Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic interaction of the three core components during a typical HS-AFM experiment for biofilm imaging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for HS-AFM Biofilm Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride Cantilevers | Base material for fabricating durable, high-frequency cantilevers. | Bruker AFM probes; used as a platform for FIB milling of custom seesaw cantilevers [5] [7]. |

| Focused Ion Beam (FIB) System | Precision milling and prototyping of advanced cantilever designs (e.g., seesaw). | Critical for R&D of next-generation cantilevers with decoupled reflective/mechanical functions [5]. |

| High-Speed Piezoelectric Scanner | Provides rapid, precise sample or probe positioning for fast imaging. | XY scanners with resonant frequencies >10 kHz; often require neural network control for hysteresis compensation [6]. |

| Supported Lipid Bilayers (SLBs) | Mimic bacterial or host cell membranes for studying membrane protein dynamics within biofilms. | Composed of DOPC or E. coli lipids; protein mobility varies with lipid composition [8]. |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | A model gram-negative bacterium for studying early-stage biofilm assembly and structure. | Rod-shaped, motile bacterium; forms honeycomb-like patterns observable via HS-AFM [9]. |

| FluidFM Technology | Enables biofilm-scale force spectroscopy by immobilizing biofilm-coated beads on a cantilever. | Allows direct measurement of adhesion forces between mature biofilms and antifouling surfaces [10]. |

| Vanillin-Modified Membranes | Anti-biofouling surfaces for testing the efficacy of biofilm adhesion reduction strategies. | Vanillin acts as a quorum-sensing inhibitor; used to validate novel force spectroscopy methods [10]. |

| Lawsone methyl ether | Lawsone methyl ether, CAS:2348-82-5, MF:C11H8O3, MW:188.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BE-18591 | BE-18591, CAS:147138-01-0, MF:C22H35N3O, MW:357.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The advancement of High-Speed AFM as a tool for visualizing dynamic biofilm processes is directly linked to innovations in its core components. The development of novel cantilevers like the seesaw design overcomes fundamental SNR limitations, while advanced control algorithms such as DenseNet-type neural networks effectively linearize high-speed piezoelectric scanners. Together with sensitive optical detection systems, these components enable the capture of biofilm assembly and remodeling at unprecedented spatial and temporal resolutions. The protocols and materials detailed in this application note provide a foundation for researchers in drug development to implement and further refine HS-AFM techniques, ultimately contributing to the development of novel anti-biofilm strategies.

In the study of dynamic biofilm processes, understanding rapid initial attachment, cellular reorganization, and extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) deposition is crucial. These events occur on timescales of milliseconds to seconds, presenting a significant challenge for conventional imaging techniques. High-speed atomic force microscopy (HS-AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool capable of capturing these processes at sub-second resolution, providing unprecedented insight into biofilm development mechanics. This application note explores the fundamental physics enabling sub-second temporal resolution in HS-AFM, with specific emphasis on the high-speed feedback and tracking systems that make such imaging possible. The technical details presented herein are framed within the context of real-time biofilm research, providing practical methodologies for researchers investigating microbial community dynamics, antimicrobial efficacy, and biofilm-material interactions.

The Physics of High-Speed Feedback Systems

The achievement of sub-second resolution in HS-AFM is fundamentally governed by the feedback control system that maintains constant tip-sample interaction forces during high-speed scanning. The performance of this system is quantified by its feedback bandwidth (f_B), which represents the frequency at which the system can accurately track sample topography without significant phase lag. According to established HS-AFM principles, this bandwidth is mathematically expressed as:

fB = α / [8(τc + τa + τs + βτ_PID + δ)] [11]

Where the respective time constants correspond to different physical components of the system:

- Ï„c: Cantilever response time (Ï„c = Qc/(Ï€fc))

- Ï„_a: Deflection-to-amplitude converter response time

- Ï„s: Z-scanner response time (Ï„s = Qs/(Ï€fs))

- Ï„_PID: PID controller processing time

- δ: Sum of other minor time delays in the feedback loop

The correction factors α and β account for closed-loop operation and PID controller performance, respectively [11]. This equation demonstrates that achieving high feedback bandwidth requires minimizing each component's response time through specialized hardware and control strategies.

Key Instrumental Components for High-Speed Operation

Table 1: Critical HS-AFM Components and Their Performance Characteristics

| Component | Function | Performance Requirements | Impact on Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short cantilevers | Measures tip-sample forces | High resonant frequency (fc ≈ 1.2 MHz in water), low spring constant (kc ≈ 0.15 N/m) [11] | Directly determines τ_c; higher fc reduces response time |

| High-speed Z-scanner | Positions sample vertically | High resonant frequency (fs), low quality factor (Qs) [11] | Minimizes Ï„_s for rapid vertical adjustments |

| Optical beam deflection sensor | Detects cantilever motion | High bandwidth, low noise | Enables fast detection of minute cantilever deflections |

| Fast D-to-A converter | Processes amplitude signals | High processing speed (n) relative to cantilever frequency [11] | Reduces Ï„_a for quicker signal conversion |

| Dynamic PID controller | Regulates feedback parameters | Gain-scheduling capability, minimal processing delay [11] | Optimizes Ï„_PID for varying surface features |

The integration of these specialized components enables modern HS-AFM systems to achieve imaging rates of 10-55 frames per second or higher, with temporal resolution reaching 10 microseconds and spatial resolution at the sub-nanometer level [12]. This performance is essential for capturing rapid structural changes in developing biofilms, such as flagellar coordination during initial surface attachment and the dynamics of EPS matrix formation.

Experimental Protocols for Biofilm Imaging

Protocol: Real-Time Visualization of Early Biofilm Formation

Objective: To capture the initial attachment phase of bacterial cells to surfaces with sub-second temporal resolution.

Materials:

- Pantoea sp. YR343 (gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium with peritrichous flagella) [2]

- PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or silicon substrates [2]

- Appropriate liquid growth medium

- High-speed AFM system (e.g., Bruker NanoRacer) with small cantilevers (fc ≈ 1.2 MHz) [11] [12]

- Fluid cell for in-situ imaging

Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Treat glass coverslips with PFOTS to create a hydrophobic surface that promotes bacterial attachment while allowing for high-resolution AFM imaging [2].

- Sample Inoculation: Inoculate Petri dishes containing treated coverslips with Pantoea cells in liquid growth medium. Incubate for approximately 30 minutes to allow initial attachment.

- Sample Preparation: Gently rinse coverslips to remove unattached cells. For hydrated imaging, transfer immediately to AFM fluid cell. For higher resolution imaging of fixed structures, air-dry samples before imaging [2].

- HS-AFM Imaging:

- Mount sample in HS-AFM system equipped with appropriate small cantilevers

- Engage tapping mode in liquid with optimized free oscillation amplitude (Aâ‚€)

- Setpoint amplitude (A_s) should be approximately 90% of Aâ‚€ to minimize tip-sample forces while maintaining stability

- Implement gain-scheduling in PID controller to accommodate varying biofilm topography

- Acquire images at 10-50 frames per second depending on scan size

- Data Acquisition: Capture image sequences for 5-30 minutes to monitor initial attachment and microcolony formation events.

Expected Results: This protocol should yield high-resolution temporal sequences revealing individual bacterial cells (approximately 2 μm length × 1 μm diameter) with visible flagellar structures (20-50 nm height) interacting with the surface. Researchers should observe the distinctive honeycomb pattern formation that occurs during early biofilm development of Pantoea sp. YR343 [2].

Protocol: Line Scanning for Enhanced Temporal Resolution

Objective: To monitor rapid conformational changes in individual biofilm matrix components with millisecond resolution.

Materials:

- Mature biofilm samples (3-5 day old)

- HS-AFM system with line scanning capability

- Specialized cantilevers with high resonant frequencies (>1 MHz in liquid)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Grow biofilms to maturity on appropriate substrates (3-5 days). Gently rinse with buffer to remove loosely attached cells.

- Region Selection: Using conventional HS-AFM imaging, identify areas of interest exhibiting dynamic structural features.

- Line Scanning Configuration:

- Position AFM tip over a single line crossing the feature of interest

- Reduce scan size to a single line (X-scan only, Y-position fixed)

- Maximize scan rate to achieve temporal resolution of 10-100 milliseconds

- Adjust feedback parameters to maintain stable tracking at high speeds

- Data Acquisition: Collect line scan data continuously for 1-5 minutes to capture transient events.

- Data Reconstruction: Utilize localization algorithms (e.g., NanoLocz) to extract sub-diffraction limit spatial information from temporal line scan data [12].

Expected Results: Line scanning enables observation of rapid structural dynamics in EPS components and membrane proteins with millisecond temporal resolution, revealing previously inaccessible information about matrix remodeling and molecular interactions within biofilms.

Figure 1: HS-AFM Feedback Control System. The diagram illustrates the critical components and their time constants within the high-speed feedback loop that enables sub-second resolution imaging. Minimizing each time constant (Ï„) is essential for achieving high feedback bandwidth.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HS-AFM Biofilm Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-treated substrates | Hydrophobic surface for controlled bacterial attachment | (1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorooctyl)trichlorosilane treated glass or silicon | Promotes reproducible attachment while enabling high-resolution imaging [2] |

| Short cantilevers | High-speed force sensing | Length: 7 μm, Width: 2 μm, Thickness: 90 nm, Resonant frequency: ~1.2 MHz in water, Spring constant: ~0.15 N/m [11] | Essential for minimizing τ_c; commercially available from NanoAndMore, NanoWorld, RIBM |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | Model biofilm-forming bacterium | Gram-negative, rod-shaped (2 μm length, 1 μm diameter), peritrichous flagella, forms honeycomb patterns [2] | Isolated from poplar rhizosphere; excellent model for studying early biofilm assembly |

| PEDOT-PSS sensors | Electrochemical impedance monitoring | Electrodeposited poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly(styrenesulfonate) on Pt wire | Enables correlative impedance measurements during HS-AFM imaging [13] |

| NanoLocz software | Analysis of HS-AFM data | Automated leveling, particle detection, super-resolution algorithms [12] | Freely available tool for handling large HS-AFM datasets; enables localization AFM |

| Antcin B | Antcin B|3CLPro Inhibitor | Antcin B: SARS-CoV-2 3CLPro inhibitor for COVID-19 research. Also studies anticancer mechanisms. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| (-)-Hydroxycitric acid lactone | (-)-Hydroxycitric acid lactone, CAS:27750-10-3, MF:C6H8O8, MW:208.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Figure 2: HS-AFM Biofilm Imaging Workflow. The experimental pathway from substrate preparation to high-temporal resolution imaging, highlighting critical steps where attention to technical details ensures successful capture of dynamic biofilm processes.

Applications in Biofilm Research

The implementation of HS-AFM with sub-second resolution has revealed previously inaccessible phenomena in biofilm development. Research utilizing the protocols outlined above has demonstrated:

Flagellar Coordination During Attachment: HS-AFM imaging of Pantoea sp. YR343 has revealed that flagellar interactions between adjacent cells exhibit coordinated patterns that facilitate the formation of distinctive honeycomb structures during early biofilm development [2].

Single-Molecule Dynamics in EPS: The combination of high temporal and spatial resolution has enabled researchers to visualize the assembly and disassembly of individual EPS components, providing insights into matrix remodeling dynamics in response to environmental stimuli [14].

Antimicrobial Mechanism Visualization: HS-AFM has captured the real-time interaction between antimicrobial peptides and bacterial membrane structures within biofilms, revealing pore formation dynamics and cellular response mechanisms at sub-second timescales [12].

These applications demonstrate how the physics of high-speed feedback and tracking enables researchers to move beyond static snapshots to truly dynamic understanding of biofilm processes, with significant implications for developing novel anti-biofilm strategies and optimizing biofilm-based biotechnological applications.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has become an indispensable tool for studying dynamic biological processes, such as biofilm formation and development, at the nanoscale. Its unique capability to characterize topography, adhesion, and nanomechanical properties in real-time and under physiologically relevant conditions provides insights unobtainable with other techniques [15] [2]. For biofilm research, understanding these parameters is crucial as they influence bacterial adhesion, community stability, resilience, and response to environmental challenges [16]. This application note details the key observable parameters and provides standardized protocols for their quantitative measurement using high-speed AFM modalities, enabling researchers to capture the dynamic nature of soft biological systems.

Key Parameters and Their Significance in Biofilm Research

The following parameters form the cornerstone of nanomechanical characterization in biofilm systems. Their quantitative assessment allows researchers to link structural features to functional outcomes in biofilm development and resistance mechanisms.

- Topography: AFM provides high-resolution, three-dimensional maps of surface morphology. For biofilms, this enables the visualization of individual cells, their arrangement within the community, and the structure of the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) [2]. Topographical imaging has revealed features like the honeycomb pattern in early Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms and the intricate network of flagella and other appendages that facilitate surface attachment and cell-cell communication [2].

- Adhesion: Adhesion forces measured by AFM reflect the chemical and physical interactions between the AFM tip (which can be functionalized) and the sample surface. In biofilms, this parameter is critical for understanding initial bacterial attachment to surfaces, cell-cohesion within the biofilm matrix, and the efficacy of anti-fouling surfaces [17] [16]. Mapping adhesion forces helps identify heterogeneous domains within the EPS that contribute to biofilm integrity.

- Young's Modulus (Elasticity): This quantitative measure of a material's stiffness is derived from force-distance curves. Biofilms are viscoelastic, and their elastic modulus is a key indicator of their mechanical strength and structural integrity [18] [16]. Monitoring changes in Young's modulus can reveal how biofilms respond to mechanical stress, nutrient availability, or antimicrobial agents.

- Deformation: The degree to which a sample is indented by the AFM tip under a given load. Softer materials, like many biofilms, exhibit higher deformation. This parameter is crucial for ensuring accurate modulus calculations and for understanding the local compliance of the biofilm, which can influence nutrient diffusion and cell protection [17].

- Energy Dissipation: This parameter quantifies the viscous energy loss during a loading-unloading cycle, providing a direct measure of the sample's viscoelasticity [18] [17]. For biofilms, a high dissipation value indicates a more liquid-like, dissipative behavior, which is a hallmark of their ability to absorb stress and resist mechanical removal [16].

Table 1: Key Nanomechanical Parameters and Their Significance in Biofilm Research

| Parameter | Description | Significance in Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|

| Topography | 3D surface morphology and roughness | Reveals cellular arrangement, EPS structure, and biofilm architecture at the nanoscale [2]. |

| Adhesion Force | Maximum attractive force on tip retraction | Quantifies cell-surface and cell-cell interactions; predicts biofilm stability and adhesion strength [17]. |

| Young's Modulus | Quantitative measure of stiffness/elasticity | Indicates mechanical strength, structural integrity, and response to environmental challenges [18] [16]. |

| Deformation | Degree of sample indentation under load | Identifies local softness/compliance; crucial for accurate modulus calculation on soft samples [17]. |

| Energy Dissipation | Viscous energy loss during indentation | Measures viscoelasticity; predicts biofilm's ability to absorb energy and resist mechanical disruption [17] [16]. |

High-Speed AFM Modes for Real-Time Measurement

Conventional AFM modes can be too slow to capture dynamic processes. The following advanced modes significantly increase data acquisition rates, enabling real-time observation of biofilm development.

- PinPoint Nanomechanical Mode: This mode operates by stopping the XY scanner at each pixel and acquiring a high-speed force-distance curve. The decoupled motion of the Z scanner eliminates lateral shear forces, minimizing sample damage [17]. Its primary advantage is the simultaneous, real-time acquisition of topography, modulus, adhesion, deformation, and dissipation images with high signal-to-noise ratio. This makes it ideal for quantifying mechanical heterogeneity in static or slowly evolving biofilm structures.

- High-Speed AFM (HS-AFM): HS-AFM utilizes miniaturized cantilevers and high-frequency feedback systems to achieve video-rate imaging (sub-second frame acquisition) [8]. This is the preferred technique for directly visualizing dynamic events, such as the movement of individual membrane proteins, the growth of EPS fibrils, or the real-time interaction between bacterial cells within a developing biofilm [8].

- Bimodal AFM: This multifrequency technique excites and measures the cantilever's response at two eigenmodes (resonant frequencies) simultaneously. It provides enhanced material contrast beyond topography by sensitively mapping variations in nanomechanical properties [19]. By incorporating nonlinear response at harmonics and mixing frequencies, material discrimination can be improved almost threefold, allowing for exquisite differentiation of components within the complex biofilm matrix without sacrificing imaging speed [19].

Table 2: Comparison of High-Speed AFM Modes for Biofilm Characterization

| AFM Mode | Key Principle | Typical Resolution | Data Output | Best for Biofilm Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PinPoint Nanomechanical | Sequential high-speed force-distance curves [17] | Nanometer lateral, piconewton force | Quantitative maps of modulus, adhesion, deformation [17] | Quantifying static mechanical heterogeneity; correlating structure with function. |

| High-Speed AFM (HS-AFM) | Miniaturized cantilevers with fast feedback [8] | Molecular to cellular scale | Real-time video of topographical changes [8] | Imaging dynamic processes: protein diffusion, appendage movement, initial attachment. |

| Bimodal AFM | Dual-eigenmode excitation with nonlinear analysis [19] | Nanometer lateral, high material contrast | Topography and qualitative/quantitative property maps [19] | High-speed mapping of material components within the EPS with superior contrast. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation for Biofilm AFM

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reproducible nanomechanical data that reflects the native state of the biofilm [15].

1. Substrate Selection and Functionalization:

- Substrates: Use atomically flat substrates such as freshly cleaved mica, silicon wafers, or glass coverslips to minimize background roughness [15].

- Functionalization: To promote bacterial adhesion, treat the substrate. For example, coat mica with poly-lysine or glass with polyethyleneimide (PEI) to introduce a positive charge for electrostatic interaction with negatively charged cell surfaces [15].

2. Biofilm Growth and Harvesting:

- Culture Conditions: Grow biofilms under controlled, relevant conditions (e.g., flow cell, agar plate, or liquid culture) to the desired developmental stage.

- Inoculation: For time-course studies, inoculate the functionalized substrate with a bacterial suspension (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343) and incubate for specific periods (e.g., 30 minutes for initial attachment, 6-8 hours for microcolony formation) [2].

- Rinsing: Gently rinse the substrate with a appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS) to remove non-adherent planktonic cells. Avoid harsh rinsing that could disrupt delicate structures like flagella [2].

3. Mounting for AFM Imaging:

- Liquid vs. Air Imaging: For high-resolution imaging and faithful mechanical characterization, perform AFM in liquid using a fluid cell. This preserves the native hydration state and physiology of the biofilm [2] [16]. If imaging in air is necessary, a brief, careful air-drying step may be used, but this can alter nanomechanical properties and introduce artifacts.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Nanomechanical Mapping

This protocol outlines the steps for performing nanomechanical mapping on a biofilm sample using a mode like PinPoint.

1. Cantilever Selection and Calibration:

- Selection: Use soft cantilevers (spring constant 0.1 - 1 N/m) for soft biological samples like biofilms to ensure sufficient deformation without damaging the sample [17]. The tip geometry (e.g., spherical tip) can help avoid sample piercing.

- Calibration: Precisely calibrate the cantilever's spring constant (using thermal tune or Sader method) and the optical lever sensitivity on a hard, non-deformable reference sample (e.g., sapphire) before measurement [15] [17]. This is non-negotiable for quantitative modulus values.

2. Measurement Parameter Optimization:

- Setpoint Force: Use the lowest possible setpoint force that maintains stable tip-sample contact. High forces will cause excessive indentation and potentially damage the delicate biofilm structure [15].

- Approach/Retract Speed: Optimize the Z-scan rate. Too fast can cause hydrodynamic effects and miss true contact point; too slow limits throughput. For PinPoint modes, high speeds (e.g., 10x conventional force-volume) are achievable [17].

- Spatial Resolution: Set the pixel resolution (e.g., 256 x 256 or 512 x 512) based on the feature size and required field of view. Balance between resolution and total acquisition time to minimize drift.

3. Data Acquisition and Model Fitting:

- Acquisition: Acquire maps over regions of interest (e.g., a single cell, a cell cluster). Ensure the sample is thick enough (>10x the indentation depth) to prevent substrate effects [15].

- Model Selection: Fit the retraction portion of the force-distance curves with an appropriate contact mechanics model [17]:

- Hertz model: For non-adhesive elastic contact.

- DMT model: For adhesive elastic contact on stiffer samples.

- JKR model: For adhesive elastic contact on softer samples (most applicable for biofilms).

- Analysis: Use the instrument's software (e.g., SmartScan) or custom scripts (e.g., in Python) to automatically process all force-curves in a map and generate spatially correlated maps of Young's modulus, adhesion, and deformation [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm AFM

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Soft Cantilevers | Probes with low spring constant (0.1 - 1 N/m); essential for soft sample indentation without damage. | Nanomechanical mapping of live bacterial cells and soft EPS [17]. |

| Functionalized Substrates | Chemically modified surfaces (e.g., poly-lysine coated mica) to promote controlled bacterial adhesion. | Studying initial stages of bacterial attachment and biofilm formation [15] [2]. |

| Calibration Samples | Hard, non-deformable samples (e.g., sapphire) and grating samples for accurate probe calibration. | Calibrating cantilever sensitivity and verifying scanner accuracy for quantitative measurements [17]. |

| Liquid Cell | A sealed chamber that allows the AFM tip and sample to be immersed in buffer or growth medium. | Imaging biofilms in physiologically relevant liquid environments [2] [16]. |

| Biofilm Growth Media | Nutritional solutions tailored to the specific bacterial strain to support robust biofilm development. | Culturing mature, native-state biofilms for mechanical testing [2]. |

| O-Acetylcamptothecin | Camptothecin, Acetate|Research Grade Topoisomerase I Inhibitor | Camptothecin, acetate is a research compound for studying Topoisomerase I inhibition and cancer mechanisms. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Hinokinin | Hinokinin|Lignan|For Research Use Only |

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Guide for HS-AFM in Biofilm Research

Within the broader context of high-speed atomic force microscopy (AFM) research on dynamic biofilm processes, obtaining stable, high-resolution images presents a significant challenge. Biofilms are structurally complex, heterogeneous microbial communities encased in extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) [2] [20]. While AFM offers unparalleled nanoscale resolution for imaging live cells under physiological conditions, its application is critically dependent on effective sample preparation [21] [22]. The lateral forces exerted by the scanning AFM tip can easily displace weakly adhered cells, compromising image quality and biological relevance [23]. Therefore, the immobilization protocol is not merely a preliminary step but a cornerstone for successful experimentation, enabling researchers to investigate dynamic events such as initial attachment, cellular division, and response to antimicrobial agents without introducing artifacts that distort true biofilm physiology. This document details standardized protocols for immobilizing live biofilms, specifically tailored for high-speed AFM imaging.

Immobilization Method Selection and Comparison

Choosing an appropriate immobilization strategy is a trade-off between achieving mechanical stability and preserving native cell viability and function. The optimal method depends on the bacterial strain, the scientific questions being addressed, and the desired imaging conditions. The table below provides a comparative overview of three established approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Bacterial Immobilization Methods for AFM Imaging

| Method | Mechanism of Immobilization | Best Suited For | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gelatin-Coated Mica [22] | Electrostatic interaction between negatively charged bacteria and a positively charged gelatin film. | Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria; high-resolution imaging in liquid; force spectroscopy. | Minimally invasive; preserves cell viability and division; suitable for dynamic studies. | Efficiency depends on gelatin source (porcine recommended); susceptible to interference from growth media and salts. |

| Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) Coated Surfaces [21] | Cationic polymer binds negatively charged bacterial cells and surface. | Strains with low inherent adhesiveness; imaging in various ionic strength buffers. | Strong, reliable adhesion in both low and high ionic strength buffers. | Can compromise cell membrane integrity if not optimized; requires addition of divalent cations for viability. |

| Immobilization-Free [23] | Uses fast force-distance curve-based AFM mode (e.g., QI mode) to eliminate lateral forces. | Motile bacteria (e.g., gliding strains); studies where any surface chemistry is undesirable. | No chemical or mechanical stress from immobilization; ideal for observing native gliding motility. | Requires specialized AFM operation modes; not all commercial systems may be compatible. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Immobilization on Gelatin-Coated Mica

This protocol is a robust and widely applicable method for imaging a broad range of bacterial strains in liquid conditions [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

- Gelatin (Sigma G-6144 or G-2625): A porcine-derived protein that forms a positively charged coating on mica, facilitating electrostatic immobilization of cells [22].

- Freshly Cleaved Mica: An atomically flat, negatively charged substrate that provides an ideal surface for the gelatin coating and subsequent imaging [22].

- Divalent Cations (Mg²âº, Ca²âº): Often added to immobilization or imaging buffers to help stabilize bacterial cell membranes and enhance viability [21].

- Dilute Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or Sucrose Solution: Used as an imaging buffer. Low ionic strength is crucial for stable immobilization, and sucrose can be used to maintain osmotic balance for sensitive cells [22].

Procedure:

- Mica Preparation: Cut mica to fit the AFM sample disk (approximately 22 x 30 mm). Cleave the mica on both sides using adhesive tape to expose a fresh, smooth surface [22].

- Gelatin Solution Preparation: Add 0.5 grams of porcine gelatin to 100 mL of boiling distilled water. Gently swirl until the gelatin is completely dissolved. Cool the solution to 60-70 °C before use [22].

- Mica Coating: Submerge the cleaved mica square into the warmed gelatin solution and withdraw it quickly. Place the coated mica on edge on a paper towel to dry in ambient air. The coated mica can be stored and used for up to two weeks [22].

- Bacterial Sample Preparation: Pellet 1 mL of a bacterial culture (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5 - 1.0) by centrifugation. Wash the pellet in a filtered, low-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., deionized water or dilute PBS) to remove growth media and salts that can interfere with adhesion. Resuspend the pellet in 500 µL of the same buffer to create a turbid suspension [22].

- Cell Deposition: Apply 10-20 µL of the bacterial suspension to the gelatin-coated mica. Spread the droplet gently with a pipette tip without touching the surface. Allow the sample to incubate for 10 minutes [22].

- Rinsing: Gently rinse the mica surface with a stream of distilled water or imaging buffer to remove loosely bound cells. The success of immobilization can be tested by allowing the sample to dry; a cloudy area indicates successful cell adhesion. For live imaging, keep the sample hydrated [22].

- AFM Imaging: Mount the sample in the AFM liquid cell and image in a compatible liquid medium such as 0.005 M PBS or a sucrose solution. Use non-contact imaging modes (e.g., Tapping Mode) or contact mode with low spring constant cantilevers to minimize lateral forces [22].

Protocol 2: Immobilization on Poly-L-Lysine Surfaces

This method provides stronger adhesion, which is useful for less adherent strains, but requires careful optimization to maintain cell viability [21].

Procedure:

- Surface Coating: Prepare a 0.1% (w/v) aqueous solution of poly-L-lysine (PLL). Apply a few drops to a clean glass or mica substrate for 5-10 minutes. Remove the excess solution and allow the surface to air dry.

- Optimized Immobilization Buffer Preparation: Use a lower ionic strength buffer supplemented with divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⺠and Ca²⺠at ~1-5 mM) and glucose to mitigate the detrimental effects of PLL on membrane integrity [21].

- Bacterial Preparation and Deposition: Prepare a bacterial pellet as in Protocol 1, but resuspend in the optimized immobilization buffer. Apply the cell suspension to the PLL-coated surface and allow it to settle for a defined period (e.g., 10-30 minutes).

- Rinsing and Imaging: Gently rinse with the immobilization buffer to remove non-adherent cells. Proceed with AFM imaging in a compatible buffer. It is critical to monitor cell viability throughout the process using membrane integrity assays [21].

Workflow for Method Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway for selecting and applying the most appropriate immobilization protocol based on research objectives and bacterial characteristics.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The field of biofilm immobilization is evolving with AFM technology. For studying highly dynamic processes like the gliding motility of filamentous cyanobacteria, immobilization-free techniques are groundbreaking. These methods utilize advanced AFM modes that acquire fast force-distance curves at every pixel, drastically reducing lateral forces and eliminating the need for chemical or physical entrapment [23]. This allows for the in-situ determination of mechanical properties like Young's modulus and turgor pressure while observing native bacterial movement [23].

Furthermore, automation and machine learning (ML) are beginning to transform sample preparation and imaging. Automated large-area AFM systems can now perform high-resolution imaging over millimeter-scale areas, overcoming the limited scan range of traditional AFMs [2]. ML algorithms are crucial for stitching these images together and for the automated segmentation, detection, and classification of cells within complex biofilm architectures, enabling quantitative analysis of parameters like cell count, confluency, and orientation over large, representative areas [2]. These advancements, combined with robust immobilization protocols, are pushing the boundaries of high-speed AFM from single-cell observations to the study of entire biofilm community dynamics.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a powerful tool for high-resolution imaging of biological samples, including biofilms, under physiological conditions. However, conventional AFM is limited by a fundamental scale mismatch: its scan range is typically restricted to areas less than 100 micrometers, while biofilms and other complex microbial communities form heterogeneous structures spanning millimeters or more [2]. This limitation has historically obstructed a comprehensive understanding of how local cellular and sub-cellular interactions give rise to functional macroscale organization.

Automated large-area AFM represents a transformative solution to this problem. This approach integrates hardware automation, advanced image stitching algorithms, and machine learning to seamlessly combine hundreds or thousands of high-resolution scans into a single, coherent millimeter-scale image [2] [24]. For researchers investigating dynamic biofilm processes, this technology enables the correlation of nanoscale features—such as individual appendages and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)—with emergent community-scale patterns and heterogeneities that dictate biofilm function and resilience.

Key Technological Advancements

Core Hardware and Software Infrastructure

The implementation of automated large-area AFM rests on two foundational pillars: programmatic control of the AFM hardware and intelligent image reconstruction software.

- Automated Operation: Traditional AFM operation is labor-intensive and requires specialized operators, making large-scale surveys impractical. The development of sophisticated Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), such as the Python library provided by Nanosurf, enables full scripting control over the AFM [24]. This automation allows for pre-programmed raster scanning patterns over centimeter-scale areas with minimal user intervention, facilitating continuous, multi-day experiments [2].

- Seamless Image Stitching: Acquiring a large-area dataset generates hundreds of individual image tiles. A critical challenge is stitching these tiles together accurately despite minimal overlap, which maximizes acquisition speed. Advanced computational algorithms merge these tiles by identifying matching features along the edges, creating a seamless, high-resolution map of the entire scanned area [2].

The Role of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are integral to making large-area AFM efficient, quantitative, and autonomous. Their applications span the entire experimental workflow [2].

- Scanning Process Optimization: ML models can refine tip-sample interactions, correct for image distortions, and employ sparse scanning approaches to significantly reduce data acquisition time [2].

- Autonomous Operation: AI-driven systems can automate routine tasks such as probe conditioning and approach. In advanced setups, large language models have even been used for direct control of the AFM, enabling truly autonomous experimentation [2].

- Image Analysis and Quantification: The massive datasets generated by large-area AFM necessitate automated analysis. ML algorithms excel at segmenting images, detecting individual cells, and classifying morphological features without human bias. This allows for the efficient extraction of quantitative parameters such as cell count, confluency, shape, and orientation across the entire millimeter-scale map [2].

Table 1: Machine Learning Applications in Automated Large-Area AFM

| Application Area | Specific Function | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition | Optimizes scanning site selection & tip conditioning [2] | Reduces human intervention, increases speed |

| Scanning Process | Corrects distortions, enables sparse scanning [2] | Enhances data quality and acquisition efficiency |

| Image Analysis | Automated cell detection, segmentation, and classification [2] | Enables quantitative analysis of massive datasets |

| Autonomous Control | Direct control via AI and language models [2] | Allows for continuous, multi-day experiments |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Large-Area AFM of Early-Stage Biofilm Formation

This protocol outlines the procedure for studying the initial attachment and organization of bacterial cells on a surface using automated large-area AFM, as applied to Pantoea sp. YR343 [2].

Materials and Reagents

- Bacterial Strain: Pantoea sp. YR343 (or other relevant strain) growing in a liquid growth medium [2].

- Substrate: Glass coverslips treated with (Heptadecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl)trichlorosilane (PFOTS) to create a hydrophobic surface [2].

- Equipment: Atomic Force Microscope equipped with a large-area scanner and automated stage. A cantilever suitable for tapping mode in air or liquid.

Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Place the PFOTS-treated glass coverslips in a petri dish.

- Inoculate the dish with the Pantoea sp. YR343 culture in liquid growth medium.

- Incubate for a designated initial attachment period (e.g., 30 minutes).

- At the selected time point, carefully remove a coverslip and gently rinse it with a buffer solution (e.g., deionized water) to remove any non-adherent cells.

- Air-dry the sample before imaging. While AFM can be performed in liquid, the cited study involved dried samples for high-resolution imaging of appendages [2].

AFM Setup and Large-Area Scan Configuration:

- Mount the prepared sample onto the AFM stage.

- Select a cantilever and engage it onto the surface in a representative area.

- Using the scripting interface (e.g., Python API), define the large-area scan parameters:

- Total Scan Area: Define the millimeter-scale region of interest (e.g., 1 mm x 1 mm).

- Individual Tile Size: Set the size of each high-resolution image (e.g., 50 µm x 50 µm).

- Tile Overlap: Specify a minimal overlap (e.g., 5-10%) between adjacent tiles to facilitate stitching.

Automated Data Acquisition:

- Initiate the automated scanning script. The system will sequentially acquire high-resolution AFM images for each predefined tile across the entire sample area.

- The process may run for several hours automatically, depending on the size of the area and the resolution of individual scans.

Post-Processing and Image Analysis:

- Image Stitching: Use the dedicated software algorithm to merge all individual image tiles into a single, large-area topographic map.

- Machine Learning Analysis: Apply trained ML models to the stitched image to automatically:

- Identify and segment individual bacterial cells.

- Classify cells based on morphology.

- Quantify parameters such as cell density, distribution, and orientation.

- Detect and analyze nanoscale features like flagella [2].

Expected Results

- The final stitched image will reveal the spatial organization of surface-attached cells over a millimeter-scale area.

- For Pantoea sp. YR343, analysis should uncover a preferred cellular orientation and the emergence of a distinctive honeycomb pattern in cell clusters after 6-8 hours of growth [2].

- High-resolution segments of the large-area map will allow for the visualization of flagella and other appendages, suggesting their role in coordinating biofilm assembly beyond initial attachment [2].

Protocol: Combinatorial Screening of Surface Modifications

This methodology leverages large-area AFM to conduct high-throughput analysis of how different surface properties influence bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation [2].

Materials and Reagents

- Gradient Surfaces: Silicon substrates with engineered surface property gradients (e.g., chemical composition, topography, or stiffness).

- Bacterial Strain: A relevant bacterial strain of interest.

Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Inoculate the gradient-structured surface with the bacterial culture.

- Incubate for a set time to allow for initial attachment.

- Rinse gently and air-dry, as described in Protocol 3.1.2.

AFM Imaging Across the Gradient:

- Mount the gradient sample.

- Program the automated AFM to perform a series of large-area scans at predefined intervals along the surface gradient.

- This generates multiple, large-area maps, each corresponding to a different set of surface properties.

Quantitative Comparison:

- For each large-area map, use ML-based analysis to calculate the bacterial density and morphological data.

- Correlate these quantitative metrics with the known surface properties at each location.

Expected Results

- This approach will identify specific surface modifications that significantly reduce bacterial density [2].

- The data provides a combinatorial understanding of how surface properties control adhesion, offering a powerful strategy for developing anti-biofilm surfaces.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Large-Area AFM Biofilm Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Substrates | Engineered surfaces to study adhesion; PFOTS creates a hydrophobic surface for attachment studies [2]. | PFOTS-treated glass [2] |

| Automated AFM Platform | AFM system with a large-range scanner and a scripting API for automated control. | Nanosurf platforms with Python API [24] |

| Image Stitching Software | Computational tool to merge hundreds of high-res AFM tiles into a seamless large-area map. | Custom algorithms with minimal feature matching [2] |

| Cell Detection ML Model | Machine learning algorithm for automated identification and segmentation of cells in large datasets. | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for image segmentation [2] |

| High-Resolution AFM Probes | Sharp cantilevers essential for resolving nanoscale features like flagella and pili. | Cantilevers for tapping mode in air or liquid |

| Paclobutrazol | Paclobutrazol, CAS:66346-05-2, MF:C15H20ClN3O, MW:293.79 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2',4'-Dihydroxyacetophenone | 2',4'-Dihydroxyacetophenone, CAS:5706-85-4, MF:C8H8O3, MW:152.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow and Data Interpretation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of automated large-area AFM, from sample preparation to quantitative insight.

Automated large-area AFM represents a paradigm shift in high-speed AFM imaging for dynamic biofilm research. By overcoming the critical spatial limitation of conventional AFM, this technology directly links nanoscale structural and functional properties to the emergent macroscale organization of biofilms. The integration of full hardware automation with machine learning for both image reconstruction and quantitative analysis transforms AFM from a manual, single-spot characterization tool into a powerful, high-throughput platform for surveying biological complexity across its inherent length scales. This capability is crucial for advancing our understanding of biofilm development, heterogeneity, and response to environmental stresses, ultimately accelerating the development of effective anti-biofilm strategies in therapeutic and industrial contexts.

The following tables summarize key quantitative parameters from high-speed Atomic Force Microscopy (HS-AFM) studies on biofilm formation, focusing on the early attachment and structural development of Pantoea sp. YR343.

Table 1: HS-AFM Imaging Parameters for Biofilm Analysis

| Parameter | Specification | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging Area | Up to millimeter-scale | Enables statistical analysis by capturing numerous cells and clusters in a single scan [2]. |

| Spatial Resolution | Nanoscale (sub-50 nm for flagella) | Resolves fine features like flagella (~20-50 nm height) and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) [2]. |

| Z-axis Resolution | ~0.10 nm (with 12-bit capture) | Provides high vertical sensitivity for detailed topographical mapping [25]. |

| Digital Resolution | 12-bit (4096 values) or higher | Preserves data integrity and prevents information loss during processing and export [25]. |

| Scan Pattern | Zig-zag raster (typical) | Standard method for data acquisition; overscan regions (~30%) are often used in high-speed modes [25]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Morphological Data from Early Pantoea sp. YR343 Biofilm Development

| Biofilm Stage | Key Observations | Quantitative Measurements | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Attachment (~30 min) | Single, dispersed cells with visible flagella and pili [2]. | Cell length: ~2 µm; Diameter: ~1 µm; Surface area: ~2 µm² [2]. | Reveals the first point of surface contact and the role of appendages [2]. |

| Microcolony Formation (6-8 hours) | Cell clusters forming a distinctive "honeycomb" pattern with characteristic gaps [2]. | Flagella observed bridging gaps between cells, extending tens of micrometers [2]. | Suggests flagellar coordination is crucial beyond initial attachment, aiding in cluster organization [2]. |

| Spatial Heterogeneity | Automated large-area AFM maps reveal preferred cellular orientation and pattern formation [2]. | High-throughput analysis of cell count, confluency, shape, and orientation over millimeter areas [2]. | Links nanoscale cellular features to the functional macroscale organization of the emerging biofilm [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Sample Preparation for HS-AFM of Bacterial Initial Attachment

This protocol details the procedure for preparing bacterial samples on solid substrates to visualize the early stages of biofilm formation using HS-AFM [2].

Key Reagents & Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Pantoea sp. YR343 (or other relevant strain) [2].

- Substrate: Glass coverslips, treated with PFOTS ((Heptadecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl)trichlorosilane) or other functionalizing agents [2].

- Growth Medium: Appropriate liquid growth medium (e.g., Lysogeny Broth) [2].

- Equipment: Sterile Petri dishes, inoculation loops, pipettes, biosafety cabinet.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Place a PFOTS-treated glass coverslip into a sterile Petri dish. PFOTS treatment creates a hydrophobic surface that promotes specific bacterial attachment [2].

- Inoculation: Inoculate the Petri dish with Pantoea cells suspended in a liquid growth medium [2].

- Incubation: Allow the sample to incubate at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 28-30°C for Pantoea) for a selected time (e.g., 30 minutes for initial attachment studies) [2].

- Rinsing: At the designated time point, carefully remove the coverslip from the Petri dish and gently rinse it with a buffer solution (e.g., deionized water or PBS) to remove any non-adherent (planktonic) cells [2].

- Drying: Air-dry the coverslip at ambient temperature before mounting it on the AFM sample stage. Note: While AFM can be performed in liquids, this specific protocol involved drying to preserve nanoscale features like flagella for high-resolution imaging [2].

- Imaging: Mount the prepared sample on the AFM for large-area, high-resolution scanning.

Protocol: Automated Large-Area HS-AFM for Biofilm Structural Analysis

This protocol describes the operation of an automated large-area HS-AFM system to capture the spatial heterogeneity of a developing biofilm [2].

Key Reagents & Materials:

- Prepared bacterial sample on a substrate (from Protocol 2.1).

- AFM System: Equipped with a large-range scanner (capable of millimeter-scale travel).

- AFM Probes: Sharp silicon nitride or silicon tips appropriate for contact or tapping mode in air or liquid.

- Computer with automated AFM control and machine learning (ML) image analysis software.

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Calibrate the AFM's piezoelectric scanners in the X, Y, and Z axes using a standard calibration grating with known feature sizes and heights [25].

- Initial Scan Region Selection: Manually or using an ML-assisted overview scan, identify a representative region of interest on the sample surface to begin automated imaging [2].

- Automated Large-Area Scanning:

- Configure the software to automatically acquire multiple contiguous high-resolution AFM images (tiles) across a millimeter-sized area [2].

- Set imaging parameters (e.g., scan speed, resolution per tile, set-point) to optimize for biological samples, balancing speed and resolution to avoid sample damage.

- The system will sequentially scan and save each tile with minimal overlap to maximize acquisition speed [2].

- Image Stitching: Use integrated machine learning algorithms to seamlessly stitch the individual image tiles into a single, high-resolution, large-area map with minimal matching features [2].

- Data Processing:

- Perform initial leveling (plane/line fitting) using open-source software (e.g., Gwyddion) or custom scripts (e.g., TopoStats) to remove sample tilt and scan line noise [25].

- Apply non-destructive filters (e.g., Gaussian filter) if needed for noise reduction and enhanced visualization, ensuring quantitative measurements are performed on the raw, leveled data [25].

- Automated Image Analysis:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HS-AFM Biofilm Studies

| Item | Function/Application in HS-AFM Biofilm Research |

|---|---|

| PFOTS-Treated Substrates | Creates a defined hydrophobic surface chemistry to study the effects of surface properties on initial bacterial adhesion and subsequent biofilm architecture [2]. |

| Functionalized AFM Probes | Sharp tips (silicon nitride) are used for high-resolution topographical imaging. Tips can be functionalized with specific chemicals or biomolecules to measure interaction forces or map chemical properties [2]. |

| Open-Source Analysis Software (Gwyddion, TopoStats) | Provides standardized, and often automated, processing and analysis of AFM data, including leveling, particle analysis, and quantitative extraction of morphological and mechanical properties [25]. |

| Machine Learning Segmentation Tools | Integrated into the AFM data pipeline to automate the detection, counting, and classification of thousands of cells from large-area scans, enabling robust statistical analysis [2]. |

| Localization AFM (LAFM) Software | A post-acquisition image analysis method that uses spatial fluctuations in topographic features to achieve sub-nanometer resolution (~4 Ã…), revealing unprecedented structural details on protein surfaces within biofilms [25]. |

Workflow and Data Processing Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for automated large-area HS-AFM analysis of biofilms, from sample preparation to quantitative data output.

Diagram 2: Step-by-step data processing pipeline for HS-AFM images, emphasizing the preservation of digital resolution and quantitative integrity.

Integrating Machine Learning for Automated Cell Detection, Classification, and Data Analysis

Application Notes