Absolute Quantification in Low-Biomass Samples: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Challenges, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

Accurate absolute quantification of microbial load in low-biomass samples—such as those from skin, respiratory tract, blood, and tumors—is critical for meaningful biological conclusions in biomedical research and drug development.

Absolute Quantification in Low-Biomass Samples: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Challenges, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Accurate absolute quantification of microbial load in low-biomass samples—such as those from skin, respiratory tract, blood, and tumors—is critical for meaningful biological conclusions in biomedical research and drug development. This article provides a foundational understanding of the unique challenges in low-biomass environments, including relic DNA bias, contamination, and host DNA misclassification. It details current methodological approaches like shotgun metagenomics with relic-DNA depletion, flow cytometry, and optimized nucleic acid extraction protocols. The content further offers troubleshooting strategies and guidelines for contamination prevention and data decontamination. Finally, it presents a comparative analysis of validation techniques and computational tools, synthesizing best practices to ensure data reliability and reproducibility in clinical and research settings.

Navigating the Low-Biomass Landscape: Core Challenges and the Critical Need for Absolute Quantification

Low-biomass samples are environments or tissues that contain minimal amounts of microbial life, often approaching the detection limits of standard molecular biology techniques [1]. These samples present unique challenges for microbiome research because the target microbial signal can be easily overwhelmed by contaminating DNA from various sources, including sampling equipment, laboratory reagents, and researchers themselves [1] [2]. The inherent low concentration of target microbial DNA means that even minute amounts of contamination can disproportionately influence results and lead to spurious conclusions about the microbial community composition.

The range of low-biomass environments is remarkably diverse, spanning both host-associated and free-living systems. In human tissues, low-biomass environments include the skin, respiratory tract, placenta, breast milk, fetal tissues, and blood [1] [3] [2]. Beyond human hosts, challenging environments include the atmosphere, hyper-arid soils, treated drinking water, the deep subsurface, ice cores, plant seeds, and certain animal guts [1]. Some environments, such as the human placenta and some polyextreme environments, have been reported to lack detectable resident microorganisms altogether, making contamination control paramount for accurate characterization [1]. The common thread connecting these diverse environments is that they all require specialized methodologies to distinguish true biological signals from technical artifacts.

Defining Characteristics and Challenges

Key Characteristics of Low-Biomass Samples

Low-biomass samples share several defining characteristics that differentiate them from high-biomass environments like gut microbiota or soil. The most obvious feature is the low absolute abundance of microbial cells, which directly translates to minimal microbial DNA yield [4]. This scarcity means that the target DNA "signal" is often dwarfed by the contaminant "noise" introduced during sampling and processing [1]. Another critical characteristic is the frequent presence of inhibitors that can interfere with downstream molecular analyses, such as host DNA in tissue samples or environmental inhibitors in water and soil samples [4]. The proportional nature of sequence-based datasets further complicates analysis, as even small amounts of contaminating DNA can dramatically skew perceived microbial community structure [1].

The challenge of "relic DNA" – DNA from dead or non-viable microorganisms – is particularly pronounced in low-biomass environments. A recent study of the skin microbiome found that up to 90% of microbial DNA could be relic DNA rather than from living communities, significantly biasing understanding of the actual living population [3]. This distinction is crucial for clinical applications where viability may impact disease progression or treatment efficacy. Furthermore, low-biomass samples often exhibit high variability between technical replicates due to stochastic effects at low template concentrations, requiring greater replication and stringent controls to ensure reproducible results [2].

Quantitative and Qualitative Challenges

| Challenge Category | Specific Issue | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Contamination | DNA from reagents, kits, personnel | False positives; skewed community structure [1] [2] |

| Technical Variation | Stochastic PCR amplification | Inconsistent community profiles between replicates [5] |

| Host/Inhibitor Interference | High host-to-microbe DNA ratio; co-purified inhibitors | Reduced sequencing depth for microbial targets [4] |

| Relic DNA | DNA from non-viable organisms | Misrepresentation of living microbial community [3] |

| Cross-contamination | Well-to-well leakage during PCR | Transfer of signal between samples [1] |

| Detection Limit Challenges | Limited microbial template | Inability to detect rare taxa; reduced statistical power [4] [5] |

Absolute Quantification Methods for Low-Biomass Research

Method Comparison and Selection Criteria

Accurate quantification in low-biomass research requires specialized approaches that address the unique challenges of minimal microbial material. Traditional relative abundance measurements provided by standard sequencing protocols are often insufficient because they can mask important biological changes in total microbial load. Absolute quantification methods provide crucial complementary data by measuring the actual abundance of specific targets, enabling more meaningful comparisons between samples and conditions.

The selection of an appropriate quantification method depends on multiple factors, including the sample type, required sensitivity, and specific research questions. Flow cytometry has demonstrated particular utility for low-biomass applications because it can rapidly distinguish and quantitate live and dead bacteria in a mixed population with minimal interference from nanoparticles or other potential inhibitors [6]. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains widely used due to its sensitivity and specificity, but it requires careful calibration and can be impaired by matrix-associated inhibitors [7]. Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) has emerged as a robust alternative, offering absolute quantification without standard curves and reduced susceptibility to inhibition effects [7].

Comparative Performance of Quantification Methods

| Method | Detection Limit | Viability Assessment | Inhibition Resistance | Throughput | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry | ~10³ cells/mL | Yes (with viability staining) | High [6] | High | Rapid enumeration of live/dead cells; nanoparticle-containing samples [6] |

| Droplet Digital PCR | ~1-10 gene copies | No | High [7] | Medium | Absolute quantification without standards; inhibitor-rich samples [7] |

| Quantitative PCR | ~10-100 gene copies | No | Low-Medium [7] | High | Target-specific quantification; high-throughput screening [7] |

| 16S rRNA qPCR | ~100 fg DNA [5] | No | Medium | High | Total bacterial load assessment; screening prior to sequencing [4] [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Low-Biomass Research

Sample Collection and Preservation

Proper sample collection is the most critical step in low-biomass research, as errors introduced at this stage cannot be remedied later. For human tissue sampling, such as respiratory tract specimens, the use of personal protective equipment including gloves, masks, and clean suits is essential to minimize contamination from researchers [1] [8]. All sampling equipment and collection vessels should be pre-treated by autoclaving or UV-C light sterilization and remain sealed until the moment of sample collection [1]. For surface sampling, innovative devices like the Squeegee-Aspirator for Large Sampling Area (SALSA) can improve recovery efficiency compared to traditional swabs by combining squeegee action and aspiration of liquid from surfaces into a collection tube, completely bypassing the problem of cell and DNA adsorption to swab fibers [9].

The choice of preservation method depends on sample type and downstream applications. For fish gill microbiomes (a model for other low-biomass mucous membranes), surfactant-based washes with agents like Tween 20 have proven effective for maximizing microbial recovery while minimizing host material collection [4]. Immediate freezing on dry ice and storage at -80°C is standard practice, with some samples benefiting from preservation solutions like DNA/RNA shield [5]. The dilution solvent used for mock communities and controls significantly influences results, with elution buffer providing more accurate representations of theoretical microbial community profiles compared to Milli-Q water or DNA/RNA shield [5].

DNA Extraction and Contamination Control

Effective DNA extraction from low-biomass samples requires maximizing microbial DNA yield while minimizing co-extraction of inhibitors. Mechanical disruption through bead beating with zirconium beads has demonstrated effectiveness for difficult-to-lyse samples, but must be balanced against potential DNA shearing [5]. For samples with high host contamination, such as fish gills or human tissues, pre-extraction methods to reduce host DNA include differential lysis approaches that exploit the weaker structure of host cell membranes compared to bacterial cell walls [4]. However, these methods may introduce bias toward Gram-positive bacteria and require careful optimization [4].

Contamination control requires a multi-pronged approach throughout the entire workflow. Laboratory reagents should be checked for DNA contamination, and DNA-free, single-use materials should be employed whenever possible [1]. The inclusion of multiple negative controls is essential, including extraction blanks (containing only lysis buffer), no-template PCR controls, and sampling controls such as empty collection vessels or swabs exposed to the air in the sampling environment [1] [5]. Decontamination of work surfaces and equipment with 80% ethanol followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., sodium hypochlorite) helps remove both viable organisms and trace DNA [1]. Ultra-clean dedicated workspaces with UV irradiation provide additional protection against contamination [1].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library preparation for low-biomass samples requires careful optimization to maintain representative amplification while minimizing technical artifacts. For 16S rRNA gene sequencing, amplification with 30 PCR cycles has been shown to provide robust representation without excessive amplification bias for respiratory samples [5]. Purification of amplicon pools by two consecutive AMPure XP steps provides superior results compared to gel electrophoresis purification [5]. For shotgun metagenomics, modifications to commercial nanopore rapid PCR barcoding kits may be necessary to achieve successful amplification with ultra-low inputs (<10 pg/sample), sometimes requiring the addition of carrier DNA [9].

Quantitative approaches before sequencing can significantly improve data quality. Quantification of 16S rRNA gene copies via qPCR facilitates not only the screening of samples prior to costly library construction but also the production of equicopy libraries based on 16S rRNA gene copies rather than equal volume loading, which has been shown to significantly increase captured bacterial diversity [4]. Sample titration experiments have demonstrated that a significant drop in sequencing reads occurs below 1e6 16S rRNA gene copies, establishing a practical threshold for successful library preparation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SALSA Sampler | Surface sample collection via squeegee-aspiration | Higher recovery efficiency (~60%) vs. swabs (~10%); bypasses adsorption issues [9] |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Standards | Positive controls for extraction and sequencing | Dilute in elution buffer (not water/DNA shield) for accurate community profiles [5] |

| DNA Decontamination Solutions | Remove contaminating DNA from surfaces and equipment | Sodium hypochlorite (bleach), UV-C, hydrogen peroxide, or commercial DNA removal solutions [1] |

| Surfactant Washes (Tween 20) | Maximize microbial recovery from surfaces | 0.1% concentration optimal for fish gills; higher concentrations cause host cell lysis [4] |

| Bead Beating Matrix | Mechanical cell lysis for DNA extraction | Zirconium beads (0.1 mm) effective for difficult-to-lyse samples [5] |

| AMPure XP Beads | PCR purification and size selection | Two consecutive cleanups recommended for low-biomass amplicons [5] |

| InnovaPrep CP Concentrator | Sample concentration for low-abundance targets | Hollow fiber concentration; elution volumes as low as 150 µL [9] |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | Viability assessment | Distinguishes intact (live) from compromised (dead) cells; reduces relic DNA signal [3] [4] |

The accurate characterization of low-biomass samples requires integrated methodological approaches that address contamination, quantification, and viability challenges at every experimental stage. While no single technique provides a complete solution, the combination of careful contamination control, absolute quantification methods, and appropriate data normalization enables robust characterization of these challenging environments. As methodological refinements continue to emerge, particularly in areas of single-cell analysis and improved viability assessment, our understanding of true microbial community structure in low-biomass environments will continue to advance, with significant implications for clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and fundamental microbial ecology.

The Pervasive Problem of Relic DNA and Its Impact on Microbial Load Interpretation

In the study of low-biomass microbial environments—such as certain human tissues, atmospheric samples, and hyper-arid soils—the interpretation of sequencing data is critically compromised by a pervasive yet often overlooked problem: relic DNA. This remnant DNA from dead cells can constitute the majority of sequenced genetic material in a sample, profoundly skewing our understanding of the actual living microbial community. For researchers and drug development professionals, this bias presents a substantial challenge in accurately characterizing microbiomes and their associations with health and disease. The following analysis compares methods to overcome this limitation, focusing on their experimental protocols, performance in quantifying viable microbiota, and applicability to low-biomass research contexts.

What is Relic DNA and Why Does It Matter?

Relic DNA refers to extracellular DNA or DNA released from dead microbial cells that persists in the environment. Unlike DNA from intact, living cells, relic DNA does not represent the metabolically active or functionally relevant population but can still be amplified and sequenced alongside DNA from viable organisms.

The problem is particularly acute in low-biomass samples like skin, where a recent 2025 study demonstrated that up to 90% of the microbial DNA sequenced can be relic DNA [3]. This significant bias distorts the true composition of the living microbiome, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about microbial diversity, taxon abundance, and community dynamics. When relic DNA is not accounted for, researchers are effectively analyzing a combined signal of both current and past microbial inhabitants rather than the actual living population interacting with the host or environment [3] [10].

The compositional nature of standard sequencing data—where results are expressed as relative abundances rather than absolute counts—further compounds this problem. In such data, an apparent increase in one taxon's relative abundance must be compensated by a decrease in others, regardless of actual changes in absolute abundance [11] [12]. This limitation becomes critical when studying conditions that alter total microbial load, as relic DNA can create the illusion of taxonomic shifts that merely reflect changes in overall cellularity rather than genuine compositional changes [13] [14].

Comparative Analysis of Absolute Quantification Methods

The table below summarizes the core methodologies developed to address relic DNA bias and enable absolute quantification in microbiome studies.

| Method Category | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Suitable for Low-Biomass Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMA Treatment with Metagenomics [3] [10] | Uses propidium monoazide (PMA) dye to cross-link and exclude relic DNA from amplification prior to shotgun sequencing. | Discriminates between live and dead cells; provides species-level resolution; compatible with absolute quantification via flow cytometry. | Requires optimization of PMA concentration and light exposure; may not penetrate all complex matrices equally. | Excellent, specifically validated for low-biomass skin samples. |

| Microbial Load Prediction via Machine Learning [13] [14] | Applies machine learning models to predict microbial load (cells/gram) from standard relative abundance data. | No additional experiments required; applicable to existing datasets; high-throughput and cost-effective. | Predictive rather than direct measurement; model performance depends on training data quality and representativeness. | Good, but may be less accurate for under-represented sample types in training data. |

| Flow Cytometry with Sequencing [10] [11] [12] | Directly counts microbial cells via flow cytometry, then integrates counts with sequencing data for absolute abundance. | Direct, quantitative measure of total microbial load; agnostic to nucleotide sequence. | Requires specialized equipment; additional experimental step; challenging for very low biomass. | Good, though sensitivity limits may apply to extremely low biomass. |

| Reference Frames & Ratio Analysis [12] | Computes log-ratios of taxa to cancel out the microbial load bias inherent in compositional data. | No need for microbial load quantification; re-analysis of existing data possible; circumvents compositionality. | Does not provide absolute abundances; identifies relative shifts rather than absolute changes. | Moderate, provides robust relative comparisons but not quantitative counts. |

Experimental Protocols for Relic-DNA Depletion

PMA Treatment Protocol for Skin Microbiome Samples

Based on the 2025 skin microbiome study, the following protocol details the integration of relic-DNA depletion with shotgun metagenomics [3] [10]:

- Sample Collection: Standardize the sampling area using plastic patterns. Swab defined skin sites with two sterile PBS-soaked plastic swabs simultaneously for 30 seconds. Break swab heads into Eppendorf tubes containing buffer solution.

- Sample Pre-processing: Vortex samples for 2 minutes at maximum speed. Filter the solution through a 5-µm filter to remove human cells and plastic debris. Pool replicates from the same swab site.

- PMA Treatment: Add 4 µL of 100-µM PMA (Biotium, cat. no. 40013) to 400 µL of bacterial extract (1-µM PMA final). Incubate in the dark at room temperature for 5 minutes. Place samples horizontally on ice 20 cm from a 488 nm light source for 25 minutes to activate PMA. Vortex gently every 5 minutes during light exposure to ensure even distribution.

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Proceed with standard DNA extraction protocols optimized for low biomass. Perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing with sufficient coverage to account for potential DNA loss from PMA treatment.

- Absolute Quantification: Analyze parallel aliquots of both PMA-treated and untreated samples via flow cytometry with SYBR Green staining and fluorescent counting beads for absolute bacterial quantification [10].

Machine Learning Workflow for Microbial Load Prediction

For researchers analyzing existing datasets where direct quantification wasn't performed, this computational approach provides an alternative [13] [14]:

- Data Preparation: Compile a large-scale metagenomic dataset with both relative abundance profiles and experimentally measured microbial loads (cells per gram) for model training. The original study used data from over 3,700 individuals.

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., gradient boosting, random forest) to predict microbial load from relative taxonomic abundance patterns. The model learns to recognize compositional signatures associated with high and low microbial density.

- Model Validation: Test the trained model on a separate hold-out dataset with known microbial loads to assess prediction accuracy.

- Application to Target Datasets: Apply the validated model to larger datasets (e.g., >27,000 individuals across 159 studies) where microbial load has not been experimentally measured. Use predicted loads to adjust association analyses between microbial features and clinical outcomes.

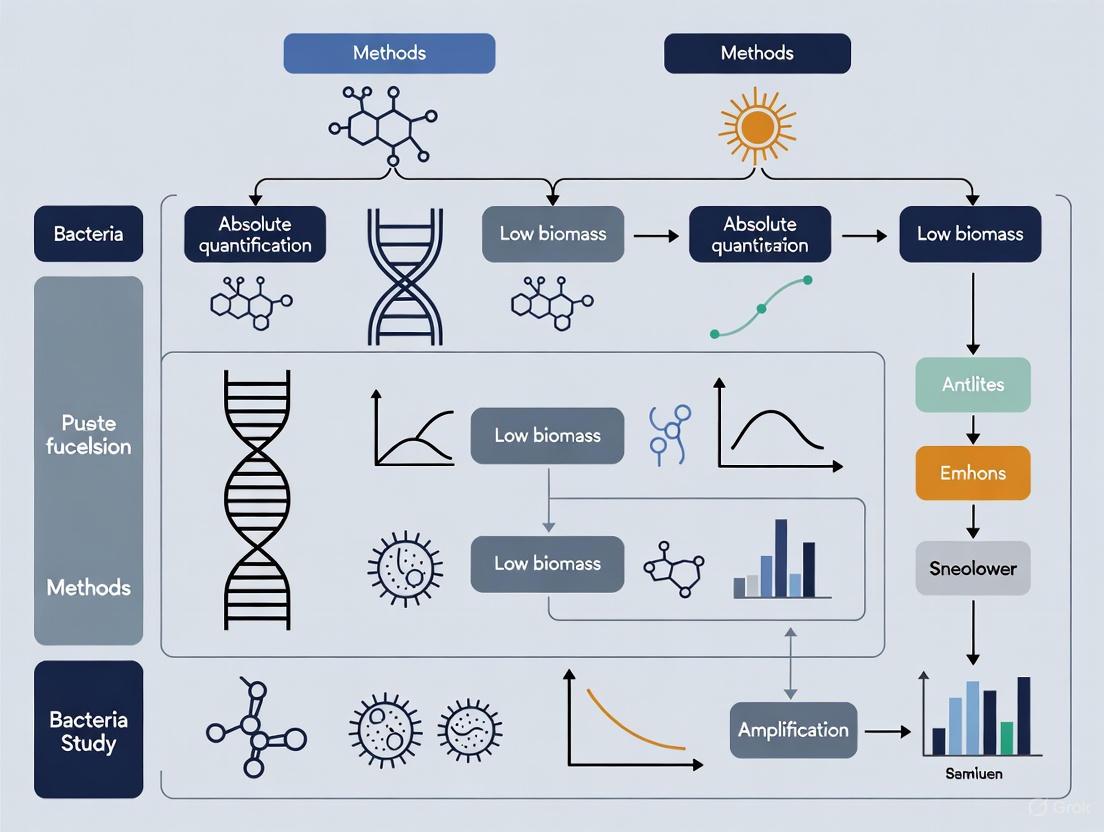

Visualizing the PMA-Based Relic DNA Depletion Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for discriminating between live and dead microbial cells using PMA treatment:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) [10] | Selective cross-linking of DNA from dead cells with compromised membranes. | Membrane impermeability critical; requires optimization of concentration and activation light exposure. |

| SYBR Green I Nucleic Acid Stain [10] [15] | Fluorescent DNA staining for flow cytometric cell counting. | Distinguishes DNA from background; used with counting beads for absolute quantification. |

| Fluorescent Counting Beads [10] | Internal standard for absolute cell quantification in flow cytometry. | Enables conversion of cell counts to concentration values (cells/volume). |

| DNA-free Swabs & Collection Tubes [1] | Minimize contamination during sample collection from low-biomass environments. | Essential for avoiding false positives; should be pre-treated to remove contaminating DNA. |

| 5-µm Filters [10] | Removal of human cells and debris from microbial samples. | Improves sequencing efficiency for microbial DNA; reduces host contamination. |

| Universal 16S rRNA Primers [12] | Target amplification for community profiling when using amplicon sequencing. | Potential primer bias affects microbial composition; less resolution than shotgun metagenomics. |

The challenge of relic DNA represents a fundamental methodological hurdle in low-biomass microbiome research, with recent studies revealing that it can dominate the genetic signal in certain environments. The methods compared herein—from experimental approaches like PMA treatment coupled with flow cytometry to computational solutions like machine learning prediction of microbial load—offer complementary pathways to overcome this limitation. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate method depends on specific research questions, sample types, and available resources. Experimental approaches provide direct, quantitative measurements of viable cells but require additional laboratory work, while computational methods offer scalability and re-analysis potential for existing datasets. As the field progresses, the integration of these absolute quantification methods will be essential for generating biologically meaningful insights into microbiome function and its role in health and disease.

The Unseen Adversary: Contamination in Low-Biomass Research

In low-biomass microbiome studies, where microbial DNA signals are faint, even minimal contamination can drastically distort results, leading to false discoveries and erroneous conclusions [1]. Contaminants originate from a myriad of sources, including laboratory reagents, sampling equipment, personnel, and the laboratory environment itself [1] [16]. The proportional nature of sequence-based datasets means that in samples with very little target DNA, the contaminant 'noise' can easily overwhelm the true biological 'signal' [1]. This challenge is particularly acute in research areas such as the human upper respiratory tract, blood, fetal tissues, and certain environmental samples like treated drinking water and hyper-arid soils [1] [8] [16]. A recent study confirmed that the background contamination patterns in DNA extraction reagents vary significantly not only between different commercial brands but also between different manufacturing lots of the same brand, underscoring a pervasive and variable problem [16].

Reagent Contamination ("Kitome")

Laboratory reagents and DNA extraction kits are well-documented sources of contaminating microbial DNA, forming a distinct background "kitome" [16].

- Evidence: A 2025 study profiling four commercial DNA extraction reagent brands (denoted M, Q, R, and Z) found that 13 different viral families were detectable as contaminants in laboratory blanks, with Parvoviridae being the most frequent [17] [16]. Furthermore, distinct profiles of bacterial contaminants were identified across different brands and, importantly, showed significant variation between different lots of the same brand [16].

- Impact: These reagent-derived contaminants can create false virus-host associations in metagenomic sequencing (mNGS) data, potentially misleading infectious disease research, zoonotic surveillance, and public health responses [17].

- Mitigation:

- Batch-Specific Profiling: Researchers should demand comprehensive background microbiota data from manufacturers for each reagent lot [16].

- Use of Blanks: Inclusion of extraction blanks (samples where water is used as input) in every sequencing run is non-negotiable. These blanks are essential for identifying the reagent-derived contaminant profile [1] [16].

- Computational Decontamination: Tools like Decontam, SourceTracker, and microDecon can statistically identify and remove contaminant sequences from datasets, typically using the prevalence-in-blanks or frequency-versus-concentration methods [16].

Cross-Contamination During Liquid Handling

The transfer of material between samples during laboratory processing is a critical point of failure.

- Sources: This includes pipette-to-sample contamination (from a contaminated pipette or aerosol), sample-to-pipette contamination (where liquid or aerosols enter the pipette cone), and sample-to-sample carry-over when the same tip is reused [18].

- Impact: Cross-contamination can lead to false-positive results and spurious correlations, directly compromising data integrity [1] [18].

- Mitigation:

- Automated Liquid Handling: Introducing enclosed, automated liquid handling systems significantly reduces human error and aerosol-based cross-contamination [19]. Many such systems are equipped with HEPA filters and UV light for decontamination.

- Proper Pipetting Technique: Always use filter tips to prevent aerosol and pipette contamination, and change the tip after pipetting each sample without exception [18].

- Maintain Pipettes: Clean pipettes regularly and ensure they are kept in a vertical position during use to prevent liquid from running into the pipette body [18].

Environmental and Human-Borne Contamination

Contamination can be introduced during sample collection and handling from the environment or the researchers themselves.

- Sources: Human operators are a major source, shedding skin cells, hair, and generating aerosol droplets through breathing [1]. The air in laboratories and sampling environments can also carry microbial contaminants [1] [20].

- Impact: For low-biomass samples like fetal meconium or upper respiratory tract swabs, human and environmental contaminants can make the sample's microbiome indistinguishable from negative controls, invalidating key findings [1].

- Mitigation:

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wearing gloves, lab coats, masks, and hairnets is essential. Gloves should be changed frequently, especially when moving between samples [1] [19].

- Sterile Workspace: Using laminar flow hoods with HEPA filters creates a sterile air environment for sample manipulation, preventing airborne contaminants from settling on samples [19].

- Decontamination of Equipment: Sampling equipment and surfaces should be decontaminated with ethanol (to kill microbes) followed by a DNA-degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) to remove residual DNA [1].

Table 1: Key Contamination Sources and Control Measures

| Contamination Source | Specific Examples | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Reagents | Silica membranes in DNA kits, molecular grade water [17] [16] | Use extraction blanks; employ computational decontamination (Decontam); request lot-specific contaminant profiles from manufacturers [16] |

| Laboratory Pipetting | Aerosols, contaminated pipette cones, carry-over between samples [18] | Use filter tips; change tips after every sample; employ automated liquid handlers; clean pipettes regularly [19] [18] |

| Human Operator | Skin cells, hair, respiratory aerosols [1] | Wear full PPE (gloves, mask, lab coat); change gloves between samples; use cleanroom suits for ultra-sensitive work [1] [19] |

| Sampling Equipment & Environment | Collection tubes, swabs, air exposure [1] [16] | Use single-use, DNA-free equipment; decontaminate with ethanol and bleach; use laminar flow hoods; collect environmental controls (air, swab) [1] |

Absolute Quantification: A Path to More Resilient Data

A fundamental limitation of traditional relative quantification metagenomics is its compositional nature, where the abundance of one taxon affects the perceived abundance of all others. This makes data from low-biomass samples, which are heavily influenced by contaminating sequences, particularly difficult to interpret accurately [21]. Absolute quantification methods, which measure the exact number of microbial cells or gene copies per unit of sample, offer a more robust framework.

- Spike-In Internal Standards: Known quantities of non-native cells (e.g., Imtechella halotolerans and Allobacillus halotolerans from ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control) or synthetic DNA sequences are added to the sample prior to DNA extraction [22] [16]. By tracking the recovery rate of these spikes through sequencing, researchers can back-calculate the absolute abundance of native taxa in the sample, providing a buffer against the distorting effects of contamination [22].

- Viability Staining with PMAxx: To distinguish between intact, viable cells and non-viable cells or free DNA (which can be contaminants), samples can be treated with PMAxx dye prior to DNA extraction. This dye penetrates membrane-compromised cells and, upon light exposure, cross-links their DNA, preventing its amplification. When combined with spike-ins and sequencing, this allows for the absolute quantification of viable bacteria, offering a clearer picture of the living community of interest [22].

A 2025 study comparing relative and absolute quantitative sequencing for analyzing gut microbiota demonstrated that absolute quantification provided a more accurate representation of the true microbial community and the modulatory effects of drugs, which were often misinterpreted by relative abundance data alone [21].

The Researcher's Toolkit for Contamination Control

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Reliable Low-Biomass Research

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Decontamination Solution | Degrades contaminating DNA on surfaces and equipment. Essential for creating a DNA-free workspace [1]. | Decontaminating sampling tools and work surfaces before and between sample processing. |

| HEPA-Filtered Laminar Flow Hood | Provides a sterile workspace by continuously flowing HEPA-filtered air, preventing airborne contaminants from settling on samples [19]. | All open-tube sample manipulations, PCR setup, and reagent preparation. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Reduces human error and cross-contamination via automated, enclosed pipetting. Many models include UV and HEPA filtration [19]. | High-throughput transfer of samples and reagents during DNA extraction and library preparation. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control | Provides a known quantity of microbial cells for use as an internal standard to enable absolute quantification [16]. | Added to a sample aliquot prior to DNA extraction to calculate absolute microbial abundances. |

| PMAxx Dye | A viability dye that selectively inhibits PCR amplification of DNA from membrane-damaged (non-viable) cells and free DNA [22]. | Treating samples to focus analysis on intact, viable cells and reduce signal from contaminating free DNA. |

| Filter Pipette Tips | Have an internal barrier to prevent aerosols and liquids from contaminating the pipette shaft, thereby protecting samples and the pipette [18]. | Used for all pipetting steps, especially when handling high-concentration DNA samples or PCR products. |

| Extraction Kits with Documented Low Biomass | Kits specifically designed or validated for low-biomass samples, ideally with provided contaminant profiles for each lot [16]. | DNA extraction from low-biomass samples like blood, swabs, or sterile water. |

Experimental Protocol: A Contamination-Aware Workflow for Low-Biomass Samples

The following integrated protocol is compiled from recent methodologies designed for low-biomass analysis [1] [8] [22].

1. Pre-Sampling Preparation:

- Decontaminate: Treat all sampling equipment (forceps, tubes, etc.) with 80% ethanol followed by a DNA-degrading solution (e.g., 0.5-1% sodium hypochlorite) and expose to UV-C light if possible [1].

- Prepare Controls: Label tubes for the following controls: (1) Extraction blank (molecular-grade water), (2) Sampling control (e.g., an empty collection vessel or a swab exposed to the air during sampling), and (3) Positive control (e.g., a mock community or a spike-in control) [1] [16].

2. Sample Collection:

- Use PPE: Wear gloves, mask, and a lab coat. Change gloves between samples if handling multiple specimens [1] [19].

- Minimize Exposure: Collect the sample with minimal handling and exposure to the environment. Immediately place it in a pre-sterilized container [1].

3. Laboratory Processing:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- In a laminar flow hood, add PMAxx dye (if viability assessment is needed) to the sample, incubate in the dark, and then photo-activate with light according to the manufacturer's protocol [22].

- Spike-In Addition: Add a known quantity of spike-in control (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS Spike-in Control) to the sample and to the dedicated positive control tube [22] [16].

- Process all samples and controls (extraction blank, sampling control, positive control) through the same DNA extraction protocol simultaneously [16].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing:

4. Data Analysis:

- Bioinformatic Processing: Process raw sequencing reads through a standard pipeline (quality filtering, denoising, OTU/ASV picking, taxonomy assignment).

- Contaminant Identification: Apply a tool like Decontam (using the "prevalence" method) to identify taxa that are significantly more abundant in the extraction and sampling controls than in the true samples, and remove them from the dataset [16].

- Absolute Quantification: Using the known input amount and the sequencing recovery rate of the spike-in control, calculate the absolute abundance of each native taxon in the original sample [22].

Diagram 1: A contamination-aware workflow for low-biomass microbiome studies integrates stringent wet-lab practices and specific controls with robust bioinformatic cleaning to yield reliable data.

Contamination is an ever-present challenge in low-biomass research, but it is not an insurmountable one. A multi-layered defense strategy is paramount. This involves acknowledging the inherent "kitome" of reagents, rigorously implementing negative and positive controls at every stage, adopting automated and careful manual techniques to prevent cross-contamination, and moving beyond relative abundance to absolute quantification where possible. By integrating these practices—from sample collection to computational analysis—researchers can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of their findings, ensuring that the signals they detect are genuine reflections of the microbiome and not merely artifacts of the laboratory process.

In the analysis of low-biomass samples, the reliance on relative abundance data generated from high-throughput sequencing presents significant interpretative challenges. The compositional nature of this data means that an apparent increase in one taxon's abundance may simply reflect a decrease in others, potentially leading to high false-positive rates in differential abundance analyses and spurious correlations [23]. This review objectively compares absolute quantification methods that provide non-negotiable solutions to these limitations, enabling true cross-sample comparability and more reliable biological insights for researchers and drug development professionals.

Relative abundance measurements, derived from normalizing sequencing data to account for technical variations, create a closed system where all measurements are interdependent. This fundamental constraint means that an increase in one taxon's relative abundance necessarily causes a corresponding decrease in others [24] [23]. In low-biomass environments—such as fish gills, sputum, or other mucus-rich samples—this limitation is particularly problematic as minor contaminants or technical artifacts can disproportionately skew the entire microbial profile [4]. The conversion to absolute quantification represents a paradigm shift that moves beyond these constraints to provide measurements that are independent, comparable across studies, and reflective of true biological reality.

Comparative Performance of Absolute Quantification Methods

Table 1: Absolute Quantification Methods for Low-Biomass Samples

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Sensitivity | Key Applications | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Partitions sample into thousands of reactions for absolute counting without standards [25] [26] | Medium | High (superior for medium-high viral loads) [26] | Viral load quantification, rare allele detection [25] [26] | Higher cost, limited automation [26] |

| Spike-in Internal Standards | Adds known quantities of exogenous cells/DNA to enable absolute calculation [24] | High | High (depends on spike-in recovery) | Gut microbiome studies, complex environmental samples [24] [23] | Requires appropriate standard selection [23] |

| Flow Cytometry (FCM) | Direct cell counting using light scattering/fluorescence [23] | High (up to 35,000 events/sec) [27] | Medium (interference from debris) [23] | Water microbiology, immunophenotyping [27] [23] | Challenging with aggregated cells [23] |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Quantifies using standard curves [25] | High | Medium (affected by inhibitors) [26] | Gene expression, pathogen detection [25] | Requires accurate standards, efficiency validation [25] |

| Microscopic Counting | Direct visual enumeration of stained cells [23] | Low | Medium | General microbial enumeration [23] | Operator-dependent, limited throughput [23] |

Technical Performance in Low-Biomass Contexts

Recent comparative studies demonstrate that dPCR exhibits superior accuracy and consistency compared to real-time RT-PCR, particularly for medium-to-high viral loads. In respiratory virus detection, dPCR showed enhanced performance for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, along with medium loads of RSV [26]. This precision is attributed to dPCR's partitioning mechanism which reduces the impact of inhibitors common in complex matrices like respiratory samples [25] [26].

Spike-in methods have shown remarkable versatility across sample types. In gut microbiome research, marine-sourced bacterial DNA spike-ins (Pseudoalteromonas sp. APC 3896 and Planococcus sp. APC 3900) enabled accurate absolute quantification in mother-infant paired samples, revealing that mothers exhibited higher total bacterial loads than infants by approximately half a log, while Bifidobacterium abundance was comparable between groups [24].

Experimental Protocols for Key Absolute Quantification Methods

Digital PCR Workflow for Viral Quantification

Protocol: Respiratory Virus Absolute Quantification Using QIAcuity dPCR [26]

- RNA Extraction: Perform nucleic acid extraction using KingFisher Flex system with MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit.

- Assay Preparation: Prepare dPCR reactions using optimized primer-probe mixes specific for target viruses (Influenza A, Influenza B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2) and internal control in multiplex format.

- Partitioning and Amplification: Load samples into nanowell plates (approximately 26,000 partitions) and perform endpoint PCR.

- Signal Detection and Analysis: Detect fluorescent signals using QIAcuity Suite software v.0.1, which calculates absolute copy number per target based on Poisson statistics.

- Quality Control: Include negative controls and validate partitioning efficiency.

Application Note: This protocol demonstrated significantly improved consistency and precision compared to real-time RT-PCR, particularly in quantifying intermediate viral levels, though it requires higher initial instrumentation investment [26].

Spike-in Internal Standard Method for Microbiome Studies

Protocol: Marine-Sourced Bacterial DNA Spike-in for Absolute Microbiome Quantification [24]

- Spike-in Selection and Preparation: Select phylogenetically distant marine bacteria (Pseudoalteromonas sp. APC 3896 and Planococcus sp. APC 3900) not found in mammalian gut microbiomes. Culture in Difco 2216 marine broth at 30°C for 24 hours.

- DNA Extraction and Quantification: Extract genomic DNA and quantify using Qubit 1X dsDNA High Sensitivity assay. Calculate copy numbers using the formula: number of copies = (amount of DNA ng × 6.022 × 10²³) / (length of dsDNA amplicon × 660 g/mole × 1 × 10⁹ ng/g).

- Sample Processing: Add known quantities of spike-in DNA to sample DNA prior to extraction or library preparation.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Perform standard 16S rRNA gene sequencing (V3-V4 regions) with appropriate controls.

- Absolute Abundance Calculation: Calculate absolute abundance of endogenous taxa using the formula: Absolute abundance = (Relative abundance of target × Spike-in DNA added) / Relative abundance of spike-in.

Application Note: This method produced results consistent with qPCR and total DNA quantification while enabling scalable, high-throughput absolute quantification without altering alpha diversity measures [24].

Optimized Sampling and DNA Extraction for Low-Biomass Samples

Protocol: Gill Microbiome Sampling for Maximum Bacterial Diversity [4]

- Sample Collection: Employ filter swab method rather than whole tissue collection to minimize host DNA contamination.

- Inhibitor Reduction: Use surfactant washes (Tween 20 at 0.1% concentration) to reduce inhibitor content while minimizing host cell lysis.

- DNA Extraction and Quantification: Extract DNA using kits validated for low-biomass samples. Quantify both host DNA and bacterial 16S rRNA genes via qPCR to assess sample quality.

- Library Normalization: Create equicopy libraries based on 16S rRNA gene copies rather than standard DNA concentration measurements.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing and analyze with appropriate bioinformatic pipelines.

Application Note: This optimized approach significantly increased captured bacterial diversity compared to traditional methods, providing greater information on the true structure of microbial communities in challenging low-biomass environments [4].

Visualizing Absolute Quantification Workflows

Diagram 1: Spike-in Workflow for Absolute Quantification illustrates the critical pathway for converting relative data to absolute values using internal standards, highlighting the divergence from compositionally constrained analyses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Absolute Quantification Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Marine Bacterial DNA Spike-ins (Pseudoalteromonas sp., Planococcus sp.) [24] | Exogenous internal standards for absolute quantification | Evolutionarily distant from gut microbes; easily distinguishable in sequencing data |

| Digital PCR Reagents (QIAcuity, Bio-Rad ddPCR) [26] | Absolute quantification without standard curves | Superior for medium-high viral loads; resistant to inhibitors |

| Viability Stains (SYTO 9, propidium iodide) [24] [23] | Distinguish live/dead cells in flow cytometry | Used in LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability and Counting Kit |

| Low-Binding Plastics (tubes, tips) [25] | Minimize DNA loss in low-biomass samples | Critical for accurate digital PCR and spike-in methods |

| Bead Beating Matrix (zirconia/silica beads) [24] | Mechanical cell lysis for DNA extraction | Essential for efficient DNA extraction from tough microbial cells |

| DNA Quantification Kits (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) [24] | Accurate DNA concentration measurement | Fluorometry preferred over spectrophotometry for low-concentration samples |

The evidence unequivocally demonstrates that absolute quantification is indispensable for robust experimental design in low-biomass research. While relative abundance data can provide a preliminary view of microbial communities, their compositional nature fundamentally limits biological interpretation and cross-study comparison. The methods detailed herein—particularly spike-in facilitated absolute quantification and digital PCR—provide viable, increasingly accessible pathways to overcome these limitations. As the field moves toward more rigorous analytical standards, the adoption of absolute quantification methods will be non-negotiable for researchers seeking to make reliable, reproducible conclusions about microbial dynamics in challenging sample types.

The accurate measurement of biological targets is a foundational pillar of biomedical research, directly influencing the reliability of diagnostic, therapeutic, and developmental outcomes. This is particularly critical in the study of low-biomass samples, where the target signal is minimal and the risk of contamination or measurement error is high. In such contexts, traditional relative quantification methods often yield misleading data, as the relative abundance of a substance can remain stable even when its absolute concentration changes dramatically [21]. Absolute quantification methods, which measure the exact number or concentration of a target molecule, cell, or pathogen, are therefore essential for deriving biologically meaningful conclusions.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of key applications, experimental protocols, and technological advancements across three pivotal biomedical fields: respiratory health, oncology, and infectious disease. The central thesis underscores that the move toward absolute quantitative techniques is revolutionizing research and clinical practice by providing more accurate, reproducible, and actionable data, especially in challenging sample types like low-biomass microbiomes, rare cancer cells, and low-titer pathogens.

Infectious Disease: Vaccine Development and Pathogen Detection

The field of infectious disease research, particularly vaccine development and pathogen characterization, relies heavily on precise quantification to track immune responses and identify causative agents.

Comparative Analysis of Vaccine Technology Platforms

The global vaccine research and development (R&D) landscape comprises 919 candidates as of 2025, targeting a wide range of infectious diseases [28]. The distribution of these candidates across different technology platforms and development phases provides insight into prevailing trends and methodological preferences.

Table 1: Global Infectious Disease Vaccine R&D Landscape (as of March 2025)

| Category | Subcategory | Number of Candidates | Percentage/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top Targeted Diseases | COVID-19 | 245 | 27% of total candidates |

| Influenza | 118 | 13% of total candidates | |

| HIV | 68 | 7% of total candidates | |

| Technology Platform | Nucleic Acid Vaccines (mRNA/DNA) | 231 | 25% of total candidates |

| Recombinant Protein Vaccines | 125 | 14% of total candidates | |

| Viral Vector Vaccines | 73 | 8% of total candidates | |

| Development Phase | Pre-Phase II (IND + Phase I) | >50% | Includes IND (8%) and Phase I (38%) |

| Phase II | 144 | ~15% of total | |

| Phase III | 137 | ~15% of total |

Geographically, vaccine development is concentrated in a few key countries. China leads with 313 candidates, followed by the United States with 276 candidates and the United Kingdom with 63 candidates [28]. The technological focus also varies by region; the U.S., France, and South Korea primarily develop mRNA vaccines, China focuses on recombinant protein vaccines, and the UK specializes in viral vector vaccines [28].

Key Experimental Protocol: Absolute Quantitative Metagenomic Sequencing

To accurately characterize low-biomass microbiomes (e.g., in the respiratory tract, blood, or other sterile sites), absolute quantitative metagenomic sequencing is superior to relative methods.

- Objective: To quantify the absolute abundance of all microbial taxa in a sample, rather than their abundance relative to each other.

- Methodology: Researchers spiked the sample with a known quantity of internal standard cells or synthetic DNA sequences (spike-ins) prior to DNA extraction [21]. Following DNA extraction, full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed using primers 27F and 1492R on a PacBio Sequel II platform. The resulting sequence data was processed to create an OTU table. The absolute abundance of each native bacterial taxon was calculated based on the ratio of its read count to the read count of the known spike-in standards.

- Comparative Data: In a study of drug effects on gut microbiota in ulcerative colitis, absolute quantification revealed that the regulatory effects of berberine (BBR) and sodium butyrate (SB) were opposite to what was suggested by relative quantitative analysis in some key bacterial genera [21]. This demonstrates that relative abundance measurements can lead to spurious correlations and incorrect conclusions about drug mechanisms.

Low-Biomass Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Low-Biomass Infectious Disease Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| DNA Decontamination Solutions | Sodium hypochlorite (bleach), hydrogen peroxide, or commercial DNA removal solutions are used to eliminate contaminating DNA from sampling equipment and work surfaces [1]. |

| Ultra-Clean Plasticware/Glassware | Pre-treated by autoclaving or UV-C light sterilization to ensure sterility before sample collection [1]. |

| Internal Standard Spikes | Known quantities of non-native cells or synthetic DNA added to samples prior to DNA extraction to enable absolute quantification during sequencing [21]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Gloves, goggles, coveralls, and masks are used to limit the introduction of contaminating human cells or DNA into low-biomass samples [1]. |

| Nucleic Acid Degrading Solutions | Used after ethanol decontamination to remove traces of DNA from equipment, ensuring that sterility equates to being DNA-free [1]. |

Workflow Diagram: Contamination Control in Low-Biomass Studies

Oncology: Innovations in Cancer Therapy and Diagnostics

The oncology field is being reshaped by precision medicine, where absolute quantification of genetic alterations, immune cell populations, and protein biomarkers is paramount for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection.

Comparative Analysis of Leading Oncology Modalities

Several innovative therapy modalities are demonstrating significant clinical success in 2025, each with distinct mechanisms and applications.

Table 3: Key Oncology Therapy Modalities and Innovations in 2025

| Therapy Modality | Mechanism of Action | Key Examples & Approvals (2025) | Performance Data & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bispecific Antibodies | Binds simultaneously to a tumor antigen (e.g., HER2, CEA) and an immune cell activator (e.g., CD3 on T-cells), recruiting immune cells to kill cancer cells [29]. | Tarlatamab (SCLC), JANX007 (Prostate), Ivonescimab (NSCLC) [29]. | Ivonescimab (VEGF-PD-1) "decisively" beat Keytruda in 1st-line NSCLC. JANX007 showed 100% PSA50 rate in prostate cancer [29]. |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) | Monoclonal antibody linked to a cytotoxic drug. The antibody delivers the drug directly to cancer cells by binding to a specific surface protein [30]. | Emrelis (NSCLC), Datroway (NSCLC, Breast), Enhertu (Breast) [30]. | Targets tumors expressing specific proteins (e.g., HER2, TROP2), selectively destroying cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue [30]. |

| Cell Therapies (CAR-T, TCR) | Engineers patient's own T-cells to express receptors (CAR or TCR) that recognize specific cancer cell targets, enabling a potent, targeted immune response [30]. | Tecelra (first FDA-approved TCR therapy for metastatic synovial sarcoma) [30]. | Primarily used for hematologic malignancies; ongoing trials for solid tumors. Demonstrates potential for durable remissions [30]. |

| Synthetic Lethality | Exploits context where mutations in two genes together result in cell death, but mutation in either alone does not. Drugs target the "synthetic lethal" partner of a cancer gene mutation [29]. | PARP inhibitors, IDEAYA's IDE705 (Pol Theta inhibitor), IDE275 (Werner helicase inhibitor) [29]. | IDEAYA's darovasertib + crizotinib showed 45% ORR in metastatic uveal melanoma. Targets HRD and MSI-high solid tumors [29]. |

Key Experimental Protocol: AI-Driven Genomic Analysis for Precision Oncology

Artificial intelligence is enhancing the quantification and interpretation of complex genomic data to guide treatment.

- Objective: To precisely identify actionable genomic targets, such as Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD), from standard biopsy slides.

- Methodology: The deep-learning tool DeepHRD was trained on whole-slide images (WSIs) of tumor biopsies that were annotated with HRD status from traditional genomic tests [30]. The AI model learns to recognize visual patterns and features in the tissue morphology that are characteristic of HRD-positive cancers. Once trained, the model can analyze new, unlabeled WSIs to predict HRD status with high accuracy.

- Comparative Data: DeepHRD was reported to be up to three times more accurate in detecting HRD-positive cancers compared to current genomic tests. Furthermore, it has a negligible failure rate, a significant improvement over the 20-30% failure rate of standard genomic tests [30]. This allows more patients to be accurately identified for treatments like PARP inhibitors.

Signaling Pathway Diagram: Bispecific T-Cell Engager Mechanism

Respiratory Health: Devices for Management and Monitoring

The respiratory care devices market is experiencing robust growth, driven by the rising prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases and technological innovation, particularly in devices suitable for home and low-resource settings [31] [32] [33].

Comparative Analysis of Respiratory Care Devices

The market is segmented into therapeutic, monitoring, and diagnostic devices, each serving a critical function in managing conditions like COPD, asthma, and sleep apnea.

Table 4: Respiratory Care Devices Market and Product Analysis

| Device Category | Key Product Types | Market Share & Growth Drivers | Performance & Technological Trends |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Devices | Ventilators, CPAP/BiPAP machines, Nebulizers, Oxygen Concentrators [31] [32]. | Held 45.33% of 2024 sales. Growth driven by rising elective surgeries and chronic disease programs [33]. | Embedding of AI-driven adaptive pressure algorithms to improve comfort and adherence. Miniaturization and portability for home use [33]. |

| Monitoring & Diagnostic Devices | Spirometers, Pulse Oximeters, Peak Flow Meters, Capnographs [33]. | Fastest-growing branch (8.53% CAGR). Catalyzed by population screening and home sleep-test kits [33]. | AI analysis of flow-volume loops for early obstruction detection. Convergence with telemedicine (e.g., wearable oximeters like OxiWear) [33]. |

| By Disease Indication | COPD, Sleep Apnea, Asthma, Infectious Diseases [32]. | COPD segment held 42.25% revenue (2024). Sleep Apnea therapies show strongest momentum (8.93% CAGR) [33]. | COPD: Demand for nebulizers and oxygen therapy. Sleep Apnea: Focus on patient comfort with fabric masks and quiet machines [33]. |

| By End User | Hospitals, Home Care Settings [32]. | Hospitals controlled 48.42% of 2024 demand. Home care is fastest-growing (9.12% CAGR) [33]. | Home care: Portable concentrators (<2.5 kg), wearable monitors, and remote-device-management portals [33]. |

Key Experimental Protocol: Validation of a Portable Respiratory Device

The shift toward home-based care necessitates rigorous testing of portable devices against clinical gold standards.

- Objective: To validate the accuracy and reliability of a new portable oxygen concentrator or ventilator for home use.

- Methodology: A cross-over trial design is often employed. Patients with a defined respiratory condition (e.g., COPD) are randomized to use either the portable device or a standard hospital-grade device for a set period, followed by a washout period and then switching to the other device [33]. Key parameters measured include:

- Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂): Continuously monitored via pulse oximetry.

- Tidal Volume and Respiratory Rate: For ventilators.

- Patient Comfort and Adherence: Using questionnaires and device usage logs.

- Clinical Outcomes: Exacerbation rates, need for hospitalization.

- Comparative Data: Researchers have responded to the high cost of traditional devices by developing modular systems that combine oxygen generation and ventilation at a lower cost. A 2025 cross-over trial validated such a portable solution as effective for acute-lung-injury care, demonstrating non-inferiority to standard equipment in maintaining SpO₂ and other physiological parameters [33].

Research Reagent Solutions for Respiratory Health

Table 5: Key Materials for Respiratory Health Research and Care

| Research Reagent / Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Flow Nasal Cannula Systems | Deliver high flows of humidified and heated air/oxygen, improving patient comfort and gas exchange in respiratory failure [32]. |

| Cloud-Linked Oximeters | Wearable or fingertip devices (e.g., OxiWear, Masimo MightySat) that monitor blood oxygen saturation (SpO₂) and pulse rate, transmitting data to clinician dashboards [33]. |

| Bluetooth-Enabled Nebulizers | Deliver liquid medication as a mist for inhalation; connected devices can track dose delivery and timing to monitor patient adherence [33]. |

| AI-Powered CPAP Algorithms | Software that adapts air pressure throughout the night based on real-time detection of breathing patterns, reducing mask leak discomfort [33]. |

| Modular Oxygen Generation Systems | Lower-cost, portable systems designed for use in resource-constrained settings, combining oxygen generation and ventilation functions [33]. |

The consistent theme across respiratory health, oncology, and infectious disease research is the indispensable value of absolute quantification and precise measurement. Whether it is quantifying bacterial load in a low-biomass microbiome, determining the exact abundance of a predictive biomarker in a tumor, or validating the output of a life-sustaining respiratory device, moving beyond relative data is critical for accuracy.

The future of biomedicine will be shaped by technologies that enhance this precision, including AI-driven diagnostic tools, next-generation sequencing with spike-in controls, and connected medical devices that provide real-world, quantitative data. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting and advocating for these absolute quantification methods is not merely a technical improvement—it is a fundamental requirement for generating reliable, translatable scientific results that can truly advance human health.

A Methodologist's Toolkit: Techniques for Precise Quantification in Low-Biomass Contexts

The accurate characterization of microbial communities is fundamental to advancing research in human health, environmental science, and drug development. However, the persistence of relic DNA—genetic material from dead or membrane-compromised cells—poses a significant challenge, particularly in low-biomass environments like skin, drinking water, and certain clinical samples. This extracellular DNA can constitute up to 90% of the total microbial DNA in some samples, profoundly skewing microbial community analyses and leading to inaccurate biological interpretations [3] [10].

Relic-DNA depletion techniques have emerged as critical methodological innovations to overcome this bias, enabling researchers to distinguish between the historical microbial footprint and the currently living community. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the primary relic-DNA depletion methodologies, their experimental protocols, performance data, and applications to empower researchers in selecting the optimal approach for their specific low-biomass research contexts.

Comparison of Major Relic-DNA Depletion Techniques

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three principal relic-DNA depletion methods used in contemporary research.

| Technique | Mechanism of Action | Best For | Key Advantages | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMA/PMAxx | Binds to and cross-links relic DNA upon light activation; cross-linked DNA is not amplified [10]. | Skin microbiome [3], saliva [34], beach water [35]. | Effectively discriminates live/dead cells; compatible with shotgun metagenomics and absolute quantification [3] [35]. | May have variable efficiency in complex, high-density communities like gut microbiota [34]. |

| Benzonase-based Approach (BDA) | Enzymatically degrades unprotected, extracellular DNA into short fragments prior to cell lysis [36]. | Skin microbiome samples, especially those with high host DNA contamination [36]. | Simultaneously depletes both microbial relic DNA and host DNA; does not require light activation step [36]. | Less effective if relic DNA is partially protected within cell debris; not selective for microbial DNA. |

| Osmotic Lysis + PMAxx (lyPMAxx) | Combines gentle osmotic lysis of human cells with subsequent PMAxx treatment of microbial relic DNA [34]. | Complex human samples (e.g., saliva, feces) requiring host DNA depletion [34]. | Highly effective for host DNA depletion (>95%); improves viable signal in complex matrices [34]. | Additional steps may increase processing time; optimization needed for different sample types. |

Performance and Experimental Data

The efficacy of relic-DNA depletion is quantifiable through its impact on microbial load assessment, community composition, and diversity metrics. The following table consolidates key experimental findings from recent studies.

| Study & Sample Type | Technique Used | Key Quantitative Finding | Impact on Community Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Skin Microbiome [3] | PMA + Shotgun Metagenomics | Up to 90% of total microbial DNA was identified as relic DNA. | Reduced intra-individual sample similarity; revealed different patterns of taxa abundance compared to total DNA sequencing. |

| Beach Water Quality [35] | PMA + Nanopore Sequencing | Achieved high agreement with culture-based counts for viable E. coli and Vibrio spp. | Enabled accurate absolute quantification of viable pathogens for improved risk assessment. |

| Skin Mock Community [36] | Benzonase (BDA) | Reduced reads from heat-killed bacteria from ~18% to <1% and depleted >99.99% of free bacterial DNA. | Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) showed distinct clustering, indicating removal of dead cell bias. |

| Human Saliva & Feces [34] | lyPMAxx + Metagenomic Sequencing | Eliminated >95% of host and heat-killed microbial DNA. | Significantly changed relative abundances of specific phyla (e.g., Firmicutes decreased in feces). |

| Antarctic Soils & Rocks [37] | Extracellular DNA Depletion | Extracellular DNA inflated diversity metrics and obscured correlations with environmental parameters. | Depletion increased the number of significant correlations between physicochemical variables and community composition. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: PMA Treatment for Shotgun Metagenomics of Skin Swabs

This protocol, adapted from Thiruppathy et al., integrates relic-DNA depletion with absolute quantification via flow cytometry [3] [10].

- Sample Collection: Swab defined skin areas using sterile swabs soaked in 1× PBS. Standardize the sampling area and duration (e.g., 30 seconds). Break off swab heads into tubes containing buffer.

- Initial Processing: Vortex samples thoroughly to dislodge cells. Filter the solution through a 5-µm filter to remove human cells and large debris.

- PMA Treatment:

- Add PMA stock solution to the sample to a final concentration of 1 µM.

- Incubate in the dark at room temperature for 5 minutes to allow dye intercalation.

- Place samples horizontally on ice, 20 cm from a 488 nm light source, for 25 minutes to photo-activate the PMA. Vortex gently every 5 minutes to ensure even exposure.

- After cross-linking, store samples at -80°C until DNA extraction.

- Parallel Absolute Quantification: Analyze an aliquot of both PMA-treated and untreated samples using flow cytometry with SYBR Green staining to determine live and total bacterial loads, respectively [3] [10].

Protocol 2: Benzonase-based DNA Extraction (BDA) for Skin Microbiome

This protocol, as described by Bjerre et al., focuses on pre-digesting unprotected DNA before microbial lysis [36].

- Sample Preparation: Resuspend skin swabs or mock community samples in an appropriate buffer.

- Benzonase Digestion: Add Benzonase nuclease to the sample and incubate to degrade all DNA not protected by an intact cell membrane.

- Enzyme Inactivation: Stop the reaction, often by adding EDTA or by proceeding to the lysis step of a commercial DNA extraction kit.

- Microbial Lysis and DNA Extraction: Continue with standard mechanical and/or enzymatic lysis protocols to break open intact microbial cells and extract the protected DNA. The QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit has been successfully used in this context [36].

- Downstream Application: Proceed with 16S rRNA gene amplicon or shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key decision points in the two primary protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents and their critical functions in relic-DNA depletion protocols.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Relic-DNA Depletion |

|---|---|

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | Membrane-impermeable dye that selectively cross-links relic DNA upon photo-activation, preventing its amplification [10] [35]. |

| PMAxx | An advanced, more efficient derivative of PMA, offering improved penetration and DNA cross-linking in complex samples [34]. |

| Benzonase Nuclease | Endonuclease that digests all unprotected DNA (both host and microbial relic DNA) into short oligonucleotides prior to cell lysis [36]. |

| SYBR Green I / Propidium Iodide (PI) | Fluorescent stains used in flow cytometry to quantify total (SYBR) and intact/membrane-compromised (SYBR+PI) bacterial cells for absolute quantification [3] [38]. |

| Cellular Spike-ins | Known quantities of foreign cells (e.g., Pseudomonas veronii) added to a sample to enable absolute quantification of microbial abundances from sequencing data [35]. |

| Bead Beating System | Mechanical lysis method using beads (e.g., stainless steel or silica) to robustly break open resilient microbial cell walls for DNA extraction [39]. |

The selection of an appropriate relic-DNA depletion technique is paramount for generating accurate and biologically relevant data in low-biomass microbiome research. PMA-based methods offer a robust solution for general viable microbial profiling and are highly compatible with absolute quantification workflows. In contrast, Benzonase-based approaches provide a powerful alternative for samples plagued by high levels of host DNA contamination. The emerging lyPMAxx protocol demonstrates superior performance for complex human samples requiring simultaneous host and relic-DNA depletion.

Researchers must consider their specific sample type, the dominant sources of DNA bias (microbial relic DNA, host DNA, or both), and the required downstream analyses (relative vs. absolute quantification) when choosing a methodology. As the field moves beyond compositional profiling, integrating these depletion techniques with absolute quantification methods will set a new standard for precision in microbial ecology and translational research.

Integrating Shotgun Metagenomics with Absolute Abundance Determination

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing has revolutionized the study of microbial communities by enabling comprehensive characterization of taxonomic composition and functional potential directly from environmental samples. However, a fundamental limitation of standard metagenomic sequencing is that it generates relative abundance data, where the proportion of each microbial taxon is expressed relative to other taxa in the sample rather than as an absolute cell count or concentration. This compositional nature of sequencing data means that information about the absolute microbial abundance is lost during sequencing, making it difficult to distinguish whether observed changes in relative abundance represent true expansion of a taxon or merely relative shifts due to depletion of other community members [40].

The challenge of absolute quantification becomes particularly critical in low-biomass environments such as certain human tissues (respiratory tract, fetal tissues), cleanrooms, hospital operating rooms, and ultra-clean manufacturing facilities, where contaminating DNA can disproportionately impact results and lead to spurious findings [9] [1]. Without absolute quantification, researchers cannot determine whether an increase in a taxon's relative abundance represents actual microbial growth or simply a relative shift caused by the decrease of other community members [41].

This guide comprehensively compares current methodologies for integrating absolute abundance determination with shotgun metagenomics, with particular emphasis on applications in low-biomass research contexts where accurate quantification is most challenging yet most critical.

Core Methodologies for Absolute Abundance Determination

Digital PCR (dPCR) and Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Anchoring

Digital PCR (dPCR) provides an ultrasensitive method for absolute quantification of microbial loads by partitioning PCR reactions into thousands of nanoliter-scale droplets or wells and counting positive amplification events. This approach enables direct enumeration of 16S ribosomal RNA gene copies without requiring standard curves, offering high precision especially in low-biomass samples where quantification is most challenging [41].

The dPCR anchoring workflow begins with efficient DNA extraction validated across different sample types and microbial loads. Researchers then perform universal 16S rRNA gene amplification using dPCR with carefully optimized primers to minimize amplification biases. The absolute abundance measurements obtained through dPCR are subsequently used to transform relative abundances from metagenomic sequencing into absolute values, typically expressed as copies per gram of sample or per extraction [41].

A recent study demonstrated that dPCR exhibits approximately 2x accuracy in DNA extraction efficiency across diverse tissue types including cecum contents, stool, and small intestine mucosa when total 16S rRNA gene input exceeds 8.3×10^4 copies. This translates to a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 4.2×10^5 16S rRNA gene copies per gram for stool/cecum contents and 1×10^7 copies per gram for mucosal samples [41].

Spike-in Standards

Spike-in standards involve adding known quantities of exogenous DNA from organisms not present in the sample before DNA extraction and library preparation. These standards serve as internal calibrators throughout the workflow, enabling conversion of relative sequencing abundances to absolute values based on the known relationship between spike-in input and sequenced output [42] [41].

The spike-in method requires careful selection of non-biological background sequences or DNA from organisms absent from the target ecosystem. The accuracy of this approach depends on efficient and equitable DNA extraction of both spike-in and native microbial DNA, as well as similar behavior during library preparation and sequencing. Recent implementations have demonstrated successful absolute quantification across samples with varying microbial loads, though performance can be compromised when spike-in DNA behaves differently than native DNA in extraction or amplification [41].

Machine Learning Prediction Models

Machine learning approaches offer a computational alternative to experimental absolute quantification by predicting microbial loads based on sample characteristics. Recent research has demonstrated that DNA concentration shows a strong positive correlation (Spearman's rho = 0.92) with absolute prokaryotic abundance as measured by ddPCR [40].

This correlation enables training of regression models, with random forest implementations achieving Spearman correlations of 0.89-0.91 between predicted and measured absolute abundances when using DNA concentration alone or in combination with additional features such as host read fraction and prokaryotic alpha diversity [40]. These models show exceptional prediction accuracy on external validation cohorts, suggesting potential for broad application where direct absolute quantification is impractical.

Flow Cytometry and Total DNA Quantification

Flow cytometry provides a direct cell counting approach that can anchor metagenomic data to absolute scales. This method requires dissociating samples into single bacterial cells followed by staining and enumeration using calibrated flow cytometers. While flow cytometry avoids amplification biases associated with PCR-based methods, it requires complex sample preparation and has not been fully validated with complex, host-rich samples such as gut mucosa [41].

Total DNA quantification represents another anchoring approach that converts relative abundances to absolute values based on total DNA concentration measurements. This method is limited to samples containing primarily microbial DNA, as substantial host DNA contamination skews quantification [41].

Table 1: Comparison of Absolute Quantification Methods for Metagenomics

| Method | Mechanism | Detection Limit | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dPCR/qPCR Anchoring | Quantification of 16S rRNA gene copies | 4.2×10^5 copies/g (stool); 1×10^7 copies/g (mucosa) [41] | High sensitivity, applicable to diverse sample types | PCR amplification biases, requires optimization |

| Spike-in Standards | Exogenous DNA added pre-extraction | Varies with spike-in level and background | Controls for technical variation throughout workflow | Potential differential extraction/amplification |

| Machine Learning Prediction | Correlation of DNA concentration with microbial load | Depends on training data quality [40] | No additional wet-lab experiments required | Limited by model training data and feature availability |

| Flow Cytometry | Direct cell counting | ~10^4 cells/mL [40] | Direct cell counting, no amplification biases | Complex sample preparation, host-rich samples challenging |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Digital PCR Anchoring Protocol

The dPCR anchoring method provides a robust framework for absolute quantification across diverse sample types, from high-biomass stool to low-biomass mucosal samples [41].

Sample Processing and DNA Extraction:

- Begin with standardized sample processing to minimize variance from differing stool amounts used for DNA extraction [40]

- Extract DNA using columns with defined capacity (e.g., 20-μg columns), determining maximum sample input through preliminary DNA quantification

- For low-biomass mucosal samples, limit input mass to prevent column saturation with host DNA (e.g., 8 mg mucosa)

- Include negative control extractions to identify contamination sources

Digital PCR Quantification:

- Perform dPCR with universal primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene

- Use microfluidic dPCR systems to partition reactions into thousands of nanoliter droplets