Advanced Strategies to Enhance Culture-Based Viability PCR Sensitivity for Accurate Pathogen Detection

Culture-based viability PCR represents a significant methodological advancement that bridges the gap between traditional culture methods and molecular detection.

Advanced Strategies to Enhance Culture-Based Viability PCR Sensitivity for Accurate Pathogen Detection

Abstract

Culture-based viability PCR represents a significant methodological advancement that bridges the gap between traditional culture methods and molecular detection. This technique combines short-term broth enrichment with quantitative PCR to differentiate viable from non-viable pathogens, addressing critical limitations in environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics. Recent research demonstrates its superior sensitivity compared to conventional culture methods and improved specificity over standard qPCR alone. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement, optimize, and validate this powerful methodology across diverse applications and pathogen types, with particular emphasis on protocol optimization strategies to maximize detection sensitivity while minimizing false-positive results.

The Science Behind Culture-Based Viability PCR: Principles and Limitations of Current Detection Methods

The accurate and timely detection of pathogens is a cornerstone of effective clinical diagnostics and microbiological research. For decades, culture-based methods have been the gold standard, providing vital information on viable organisms and antimicrobial susceptibility. The advent of quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) introduced a new era of speed and sensitivity. However, both techniques possess significant, inherent limitations that can create critical gaps in diagnosis and research, particularly for slow-growing, fastidious, or non-viable organisms. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate these challenges, with a focus on advancing the sensitivity and reliability of culture-based viability PCR.

Comparative Analysis of Detection Methods

The table below summarizes the core limitations of culture and standard qPCR, which contribute to the critical detection gap.

| Method | Key Limitations | Impact on Sensitivity/Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Culture-Based | Long turnaround time (24 hours to several weeks) [1] [2] | Fails to detect viable but non-culturable (VBNC) bacteria, or those affected by prior antibiotic treatment [3] [4] |

| Low sensitivity for heterogeneous or low-abundance pathogens [3] | High false-negative rates; up to 20% culture-negative in periprosthetic joint infections [3] | |

| Requires viable, cultivable organisms [2] | Cannot detect viruses or pathogens that cannot be grown in vitro [1] | |

| Standard qPCR | Cannot distinguish between live and dead cells [5] | High false-positive risk from detecting non-viable pathogen DNA [5] |

| Susceptible to PCR inhibitors in sample matrices [6] [7] | Can lead to false negatives or inaccurate quantification [6] | |

| Requires pre-defined targets; no isolate for further tests [1] [2] | Provides no antimicrobial susceptibility profile (AST) [2] |

Troubleshooting Culture-Based Methods

Q1: How can I improve the detection of heterogeneously distributed or aggregated bacteria in tissue samples?

The Problem: Bacterial aggregates, often found in biofilm-associated infections like periprosthetic joint infections (PJIs) or osteomyelitis, are not uniformly distributed in tissue. This heterogeneity dramatically reduces the probability of a biopsy sample containing a detectable number of bacteria [3].

Solutions and Strategies:

- Increase Sample Number: Below a critical aggregation size, obtaining five tissue specimens significantly increases the probability of detection [3]. This principle is embedded in some diagnostic guidelines, where 2/5 positive tissue samples is a confirmatory criterion for infection [3].

- Homogenize Tissue Specimens: Mechanical homogenization of the entire tissue specimen increases the surface area for analysis and can help disperse bacterial aggregates, making the bacteria more accessible for detection [3].

- Mathematical Modeling for Sampling Strategy: Research indicates that the probability of detection is influenced by bacterial load, aggregate size, and sample volume. When bacterial aggregation is high, simply increasing the number of specimens provides limited benefit. In such cases, methods like homogenization that address the aggregation itself are more effective [3].

Q2: What can I do when culture results are negative despite strong clinical evidence of infection?

The Problem: Culture-negative infections can occur due to prior antibiotic administration, the presence of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) bacteria, or slow-growing, fastidious organisms [4] [8].

Solutions and Strategies:

- Extend Incubation Time: For certain fastidious pathogens, incubating cultures for at least 14 days is recommended instead of the standard 48-72 hours [3].

- Use a Combination of Culture and Molecular Methods: Integrate culture-independent methods to confirm an infection.

- PCR or mNGS: These methods can detect pathogen DNA even when cultures are negative. A study on kidney transplant patients showed that metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) had a significantly higher positive detection rate in organ preservation fluids (47.5% vs 24.8%) and wound drainage fluids (27.0% vs 2.1%) compared to conventional culture [8].

- Histopathological Examination: Can confirm the presence of inflammation and microorganisms in tissue [3].

Troubleshooting Standard qPCR

Q3: How can I overcome the inability of standard qPCR to distinguish between live and dead cells?

The Problem: Standard qPCR detects DNA from both viable and non-viable cells, which can lead to false positives and overestimation of the infectious burden, especially after pathogen inactivation [5].

Solution: Implement Culture-Based Viability PCR This novel method combines the sensitivity of qPCR with the ability to confirm viability through a short incubation step [5].

Experimental Protocol for Culture-Based Viability PCR [5]:

- Sample Split: Divide the processed sample homogenate into three paths.

- T0 (Initial Load): Add a portion of the homogenate to growth broth, immediately extract DNA, and perform species-specific qPCR. This gives the baseline signal.

- T1 (Post-Incubation): Add another portion to growth broth and incubate under species-specific conditions (e.g., 24-48 hours at 37°C).

- Growth Negative Control (GNC): Treat a portion with a sterilizing agent (e.g., sodium hypochlorite) to kill any cells, then wash and add to growth broth. This control identifies false-positive signals from persistent environmental DNA.

- Post-Incubation Analysis: After incubation, extract DNA from the T1 and GNC samples and perform qPCR.

- Viability Determination: A sample is considered viable if:

- It is detected at T0, and the Ct value decreases by at least 1.0 at T1 compared to the GNC, indicating growth; or

- It is undetected at T0 but detected at T1 and undetected in the GNC.

This workflow harnesses the sensitivity of qPCR while confirming cell viability through proliferation. One study found that this method detected viable Staphylococcus aureus in 73% of environmental samples that were positive by qPCR, whereas traditional culture detected no viable cells in those same samples [5].

Q4: What are the common causes of high Ct values, low yield, or non-specific amplification in qPCR?

The Problem: qPCR assays can suffer from inefficiencies that lead to unreliable data.

Solutions and Strategies:

- High Ct Values/Low Yield:

- Cause: Often due to poor nucleic acid quality, inefficient cDNA synthesis (for RT-qPCR), suboptimal primer design, or the presence of PCR inhibitors [7].

- Fix: Ensure high-quality RNA/DNA extraction and purification. Optimize cDNA synthesis conditions. Redesign primers using specialized software to ensure appropriate length, GC content, and melting temperature (Tm) [7]. Use automation for precise pipetting to ensure consistent template concentrations [7].

- Non-Specific Amplification:

- General qPCR Failures: The MIQE 2.0 guidelines provide a critical framework for ensuring qPCR rigor and reproducibility. Common failures include using unvalidated reference genes, assuming rather than measuring assay efficiency, and poor sample handling [6]. Adherence to these guidelines is essential for generating trustworthy data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q5: In which clinical scenarios does PCR clearly outperform culture?

PCR demonstrates superior performance in several key scenarios [4] [10] [2]:

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): In sputum samples from COPD patients, qPCR showed significantly higher positivity rates for key pathogens like Haemophilus influenzae (up to 47.1% vs 23.6% with culture) and Moraxella catarrhalis (up to 19.0% vs 6.0%) [4].

- Complicated Urinary Tract Infections (cUTIs): A randomized controlled trial found that PCR-guided treatment for cUTI resulted in significantly better clinical outcomes (88.1% vs 78.1%) and a much faster mean turnaround time (49.7 hours vs 104.4 hours) compared to culture-guided treatment [10].

- When Patients Have Received Prior Antibiotics: PCR can detect pathogen DNA even when the bacteria have been rendered non-viable by antimicrobial therapy, a situation where culture often fails [4].

- Detection of Atypical or Non-Culturable Pathogens: mNGS and PCR can identify viruses, fastidious bacteria, and atypical pathogens like Mycobacterium and Clostridium tetani that are missed by routine culture [8].

Q6: When is culture still an indispensable method?

Despite the advantages of molecular methods, culture remains critical when:

- Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) is required: Culture is the only method that provides a live isolate for phenotypic AST, which is essential for guiding targeted antibiotic therapy [2].

- Broad-spectrum detection is needed: For unknown pathogens, culture does not require pre-selected targets, unlike specific PCR panels [2].

- Public health surveillance requires isolate biobanking: Isolates are needed for further characterization, typing, and epidemiological studies [2].

Q7: What emerging technologies are helping to bridge the detection gap?

- Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS): This culture-independent method allows for the comprehensive detection of all nucleic acids in a sample (bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites). It is highly valuable for diagnosing infections with atypical presentations or from difficult-to-culture pathogens [8].

- Automated Liquid Handling Systems: Automation significantly improves the accuracy and reproducibility of qPCR workflows by reducing pipetting errors and cross-contamination risks, leading to more consistent Ct values [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Neutralizing Buffer | Inactivates disinfectants in environmental samples (e.g., from swabs), preserving viable cells for culture-based viability PCR [5]. | Essential for accurate environmental monitoring in healthcare settings. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Digests mucus in sputum samples, improving DNA extraction efficiency and pathogen release for both culture and PCR [4]. | Critical for processing viscous respiratory samples. |

| SYBR Green / TaqMan Probes | Fluorescent chemistries for real-time detection of amplified DNA in qPCR [5] [1]. | SYBR Green is cost-effective; TaqMan probes offer higher specificity through an additional hybridization step. |

| Hot-Start PCR Kits | Reduce non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by keeping the polymerase inactive until the first high-temperature denaturation step [9]. | Improves assay specificity and sensitivity, especially for low-abundance targets. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extractors | Standardize and streamline the DNA/RNA extraction process, increasing throughput and reducing human error and contamination [7]. | Key for reproducibility in high-volume laboratories. |

In the context of culture-based viability PCR, broth enrichment serves as a critical pre-amplification step that significantly increases the detection of viable pathogens. This process involves incubating a sample in a nutrient-rich, often selective, broth before DNA extraction and PCR analysis. By providing optimal conditions for viable cells to multiply, enrichment directly addresses key limitations of molecular methods, namely the inability to distinguish live from dead cells and the presence of inhibitory substances [5] [11]. This guide explores the fundamental principles behind this enhancement and provides troubleshooting support for researchers aiming to optimize this sensitive detection method.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is broth enrichment necessary before PCR if the PCR itself is highly sensitive? While PCR can detect minute amounts of DNA, this sensitivity is a double-edged sword. It cannot distinguish between DNA from live, dead, or even free-floating DNA fragments. Broth enrichment ensures that a positive signal is generated primarily from viable organisms capable of replication, thereby confirming viability [5] [11]. Furthermore, enrichment dilutes PCR inhibitors that may be co-extracted from the sample matrix, reducing false-negative results [12].

2. How does selective enrichment broth suppress background flora without harming target pathogens? Selective enrichment broths are formulated with specific nutrients that favor the growth of target pathogens while incorporating agents—such as antibiotics, dyes, or salts—that inhibit the growth of common non-target microorganisms. For example, SEL broth is designed to allow the concurrent growth of Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Listeria monocytogenes while suppressing competing flora [13]. The key is selecting inhibitory agents and concentrations that minimally impact the recovery and growth of the target, even if it is sub-lethally injured [14].

3. What are common signs that my enrichment process is failing? Enrichment failure can manifest in several ways during downstream analysis:

- Consistent False-Negatives by PCR: The target pathogen is known to be present (e.g., via an alternative method), but PCR fails to detect it. This can indicate that the broth was unable to resuscitate and propagate injured cells or that inhibitors were not sufficiently diluted [14] [12].

- Poor Growth in Post-Enrichment Culture: Even if PCR is positive, failure to culture the organism from the enriched broth may suggest that the enrichment conditions are too harsh, killing the target or preventing its growth to detectable levels on solid media [5].

- High Background Flora in Cultures: Excessive growth of non-target organisms on non-selective agar plates after enrichment indicates that the selectivity of the broth is insufficient for the sample type being tested [13].

4. My PCR results after enrichment are inconsistent. What could be the cause? Inconsistent results often point to issues with the sample or the enrichment broth itself:

- Injured Target Cells: If a sample contains cells sub-lethally injured by stress (e.g., cold, acid, chlorine), they may not recover uniformly in the enrichment broth, leading to variable detection [14] [12].

- Inhibitors Not Fully Diluted: Some complex sample matrices, like egg yolk or kimchi, contain potent PCR inhibitors that may not be fully neutralized or diluted in a single enrichment step, requiring a two-step enrichment process for reliable detection [12].

- Broth Selectivity: The selective agents in the broth might partially suppress the target pathogen, especially if the inoculum size is small, leading to stochastic growth and detection failures [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Detection Sensitivity After Enrichment

This issue arises when the number of target organisms after enrichment remains below the detection limit of the PCR assay.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Poor resuscitation of injured cells | Use a non-selective or mildly selective pre-enrichment for 2-6 hours before transferring to a selective enrichment broth. This two-step process aids the repair of sub-lethally injured cells [12]. | A study on detecting Salmonella in liquid egg products found that a one-step enrichment in a selective medium failed to resuscitate heat-injured cells, while a two-step process with BPW succeeded [12]. |

| Insufficient enrichment time | Extend the enrichment time. A 16-24 hour enrichment is standard, but some targets or sample types may require optimization of this duration [15]. | In MRSA detection, a 16-hour enrichment in a selective broth was sufficient to increase the detection of positive samples by 35% compared to direct plating [15]. |

| Inappropriate broth formulation | Select an enrichment broth validated for your specific target and sample matrix. Consider factors like the presence of selective agents and the nutritional composition [14]. | A comparison of broths for detecting E. coli O157:H7 in kimchi found that FDA broth with ACV supplements inhibited chlorine-injured cells, while ISO and KFC broths with novobiocin allowed recovery [14]. |

Problem: PCR Inhibition After Enrichment

In this scenario, the target pathogen grows in the broth, but components from the broth or sample co-extract with DNA and inhibit the PCR reaction.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Carryover of enrichment broth components | Dilute the extracted DNA template or use a DNA purification kit designed to remove common inhibitors like humic acids, salts, and polysaccharides. | PCR troubleshooting guides recommend re-purifying or precipitating DNA to remove residual salts or inhibitors that can affect the DNA polymerase [16]. |

| High concentration of background flora | Optimize the selectivity of the enrichment broth. If using a non-selective broth, switch to a selective one to reduce the overall microbial load and complexity of co-extracted DNA. | SEL broth, a multiplex selective enrichment broth, was shown to inhibit greater numbers of non-target organisms than a universal preenrichment broth (UPB), improving detection efficiency [13]. |

| Sample-specific inhibitors | Incorporate a two-step enrichment protocol. The first step revives the cells, and the second step in a fresh medium further propagates them while drastically diluting the original inhibitors [12]. | For liquid egg yolk, a one-step enrichment in BPW was ineffective at removing PCR inhibitors. A second enrichment in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth overcame this issue and achieved 100% detection accuracy [12]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Culture-Based Viability PCR for Environmental Sampling

This protocol, adapted from recent research, is designed to detect and confirm the viability of specific pathogens from environmental surfaces [5] [17].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Foam sponges premoistened in neutralizing buffer | To collect samples from large or irregular surfaces without degrading the target pathogens. |

| Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB) | A general-purpose, nutritious growth medium used to support the proliferation of a wide range of bacteria, including E. coli and S. aureus. |

| Sodium hypochlorite (Bleach) solution (8.25%) | Serves as a growth negative control by lethally sterilizing an aliquot of the sample, ensuring that subsequent DNA detection is due to viable organisms. |

| Species-Specific Primers & SYBR Green Master Mix | For the quantitative PCR (qPCR) step. SYBR Green intercalates into double-stranded DNA, allowing for quantification of the amplified product in real-time [11]. |

| Stomacher apparatus | Provides a gentle yet effective mechanical method to release microorganisms from the sample sponge into a homogeneous liquid suspension (homogenate). |

Methodology:

- Sample Collection & Processing: Collect samples from the environment (e.g., hospital bed footboards) using a premoistened neutralizing sponge. Process the sponge using a stomacher to create a 5 mL homogenate [5].

- Sample Splitting: Aseptically split the homogenate into three paths:

- T0 (Immediate Analysis): Combine 500 µL of homogenate with 4.5 mL of TSB. Immediately perform DNA extraction and qPCR.

- T1 (Post-Enrichment): Combine 500 µL of homogenate with 4.5 mL of TSB. Incubate under species-specific conditions (e.g., 24h at 37°C for E. coli).

- GNC (Growth Negative Control): Treat 500 µL of homogenate with 4.5 mL of sodium hypochlorite to kill all cells. After neutralization and washing, resuspend in TSB and incubate alongside T1 [5].

- Post-Enrichment Analysis: After incubation, extract DNA from the T1 and GNC samples and perform qPCR.

- Viability Assessment: A sample is considered viable if:

Protocol 2: Two-Step Enrichment for Detection in Inhibitory Matrices

This protocol is optimized for challenging samples like liquid egg products, where inherent components can inhibit PCR [12].

Methodology:

- First Enrichment (Resuscitation): Inoculate 25 g of sample into 225 mL of Buffered Peptone Water (BPW). Incubate at 37°C for 3-5 hours. This lower-stress environment helps resuscitate injured Salmonella cells without the pressure of selective agents.

- Second Enrichment (Amplification & Dilution): Transfer a small aliquot (e.g., 0.1-1 mL) of the pre-enriched BPW culture into 10 mL of Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth. Incubate at 37°C for an additional 9-11 hours (total enrichment time of ~14 hours). This step further multiplies the target pathogen and dilutes out PCR inhibitors present in the original sample matrix.

- DNA Extraction and Detection: Extract DNA from the second enrichment broth and proceed with your chosen PCR detection method (e.g., the BAX system or other qPCR assays) [12].

Workflow and Data Visualization

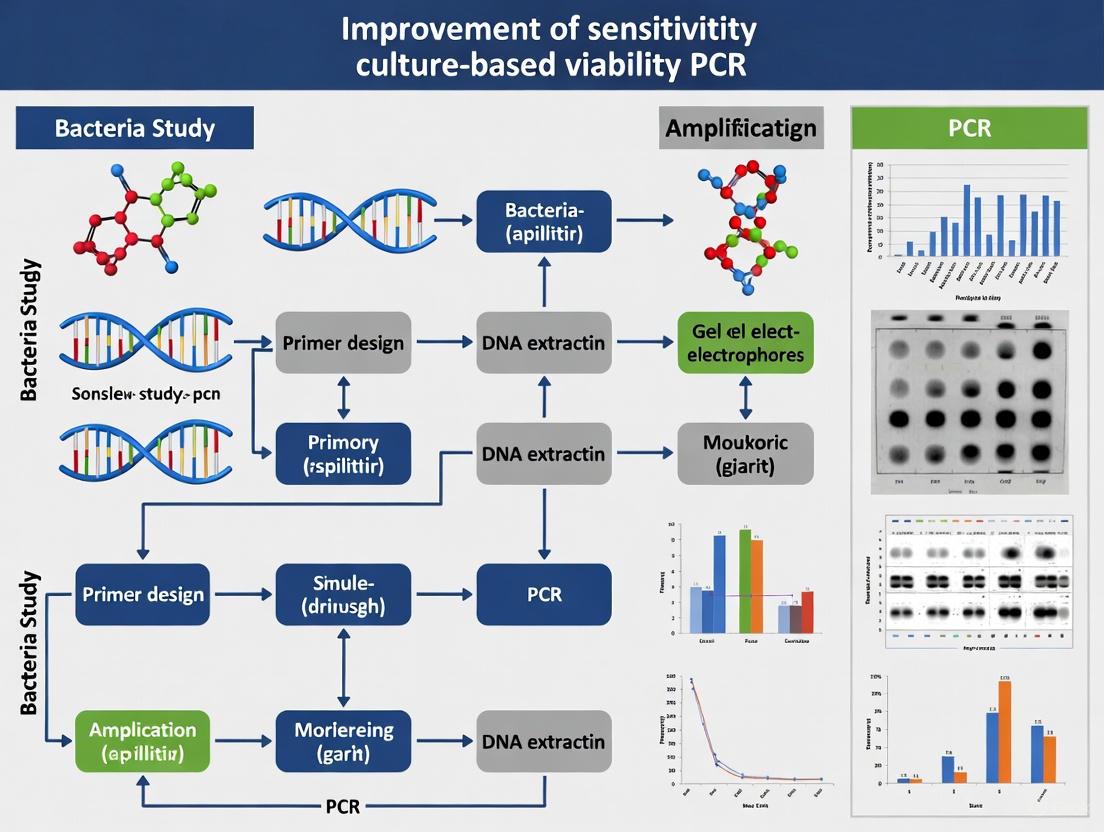

Broth Enrichment Workflow for Viability PCR

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a culture-based viability PCR experiment, highlighting the role of broth enrichment in confirming the presence of live pathogens.

Quantitative Impact of Broth Enrichment

The table below summarizes quantitative data from key studies, demonstrating how broth enrichment enhances detection sensitivity compared to direct molecular or culture methods.

Table: Impact of Broth Enrichment on Pathogen Detection Sensitivity

| Pathogen | Sample Type | Detection Method | Key Finding: Enrichment vs. Direct Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | Clinical samples | Broth enrichment + qPCR vs. selective plating | Increased number of MRSA-positive samples by 35% (from 49 to 66) | [15] |

| S. aureus | Hospital surfaces | Culture-based viability PCR vs. traditional culture | Detected viable cells in 73% of qPCR-positive samples vs. 0% by direct culture* | [5] |

| E. coli O157:H7 | Kimchi | Enrichment in ISO broth vs. FDA broth | Supported recovery of chlorine-injured cells; FDA broth showed inhibition or no growth | [14] |

| Salmonella Enteritidis | Liquid egg yolk | Two-step enrichment + BAX vs. one-step | Achieved 100% diagnostic accuracy; one-step enrichment yielded unstable results | [12] |

Note: In the same study, 19% of S. aureus samples were culturable *after broth enrichment (T1), highlighting how enrichment enables later culture detection [5].

FAQs: Addressing Common Questions on Culture-Based Viability PCR

What is culture-based viability PCR and how does it improve upon traditional methods? Culture-based viability PCR is a two-step method that combines a short incubation in a growth broth with subsequent quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis. It first enriches viable (living) microorganisms in a sample by incubating them in a culture medium. DNA is extracted and analyzed via qPCR both before and after this incubation. An increase in DNA after incubation indicates the presence of viable organisms that were able to replicate. This method outperforms traditional culture plates, which can be slow and have a high detection threshold, and standard qPCR, which cannot distinguish between live and dead cells because it detects all DNA present [5] [17] [18].

What are the primary causes of no amplification or low yield in viability PCR, and how can I resolve them? A lack of PCR product can stem from several issues related to the template DNA, reaction components, or cycling conditions [19] [16].

- Template DNA: Confirm the DNA template's quantity is sufficient and its quality is high, without contaminants like phenol or salts that can inhibit the polymerase enzyme. Solutions include repurifying the DNA, using polymerases known for high tolerance to inhibitors, and ensuring no reaction components were omitted [19] [16] [20].

- Reaction Components: Verify that primers are designed correctly and are at an adequate concentration. Optimize the concentration of magnesium ions (Mg2+), which is critical for polymerase activity. Using a hot-start DNA polymerase can prevent non-specific amplification and improve yield [19] [16].

- Thermal Cycling Conditions: Ensure the annealing temperature is optimal for your primer set (typically 3–5°C below the primer Tm). Check that the number of cycles and the extension time are sufficient for the target amplicon [16] [20].

Why am I seeing non-specific PCR products or primer-dimer formations? Non-specific amplification occurs when primers bind to unintended regions of the DNA template, often due to low reaction stringency [19] [16].

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Raise the temperature stepwise by 1–2°C increments to enhance specificity [16].

- Optimize Reagent Concentrations: High concentrations of primers, DNA template, or Mg2+ can promote non-specific binding. Use optimized concentrations, and consider using hot-start polymerases that are inactive until the high-temperature denaturation step [19] [16].

- Review Primer Design: Ensure primers are specific to the target and do not have complementary sequences to each other, which can lead to primer-dimer formation. Software tools can help design specific primers [19] [16].

My gel shows smeared bands. What does this indicate and how can I fix it? Smeared bands can result from degraded DNA template, non-specific products, or contaminants [19].

- Check DNA Integrity: Evaluate the quality of your input DNA by gel electrophoresis. Degraded DNA will appear as a smear and should be re-isolated [16].

- Optimize PCR Conditions: Increase the annealing temperature to reduce non-specific binding. Ensure the extension time is appropriate for the length of your target amplicon [19] [16].

- Address Contamination: Smearing can be caused by accumulated amplifiable DNA contaminants in the lab environment. Using a new set of primers with different sequences can often resolve this issue. Implementing strict physical separation between pre- and post-PCR workspaces is a key preventive measure [19].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Problems and Solutions in Viability PCR

Troubleshooting Low or No Amplification

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Poor DNA template quality or integrity | Re-purify template DNA to remove inhibitors (phenol, salts). Minimize shearing during isolation. Assess DNA integrity via gel electrophoresis [19] [16]. |

| Insufficient DNA template quantity | Increase the amount of input DNA. If the target copy number is very low, increase the number of PCR cycles (up to 40) [16]. |

| Incorrect primer concentration or design | Optimize primer concentration (typical range 0.1–1 µM). Redesign primers to ensure specificity and correct binding to the target [16] [20]. |

| Suboptimal Mg2+ concentration | Perform a series of test reactions with varying Mg2+ concentrations to determine the optimal level for your specific reaction [19] [16]. |

| Suboptimal annealing temperature | Use a gradient thermal cycler to determine the ideal annealing temperature. Increase the temperature if non-specific products are seen, or decrease it if yield is low [16] [20]. |

| Insufficient enzyme activity | Confirm the DNA polymerase is within its expiration date and has not been degraded by multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Increase the amount of polymerase if inhibitors are suspected [16] [20]. |

Troubleshooting Non-Specific Products and Primer-Dimers

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Annealing temperature is too low | Increase the annealing temperature incrementally by 1–2°C. The optimal temperature is usually 3–5°C below the lowest primer Tm [16]. |

| Excess primers, template, or enzyme | Optimize concentrations of all reaction components. High primer concentrations specifically promote primer-dimer formation [19] [16]. |

| Poor primer design | Avoid primers with complementary sequences, especially at the 3' ends. Use software tools to design specific primers and check for secondary structures [19] [16]. |

| Non-hot-start DNA polymerase | Switch to a hot-start DNA polymerase to prevent enzyme activity during reaction setup at lower temperatures, which can cause primer-dimer and non-specific synthesis [19] [16]. |

| Excessive cycle number | Reduce the number of PCR cycles to minimize the accumulation of non-specific products in later cycles [16]. |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies from Cited Studies

Protocol: Culture-Based Viability PCR for Healthcare Pathogens

This detailed protocol is adapted from a study detecting viable pathogens on hospital surfaces [5] [17].

1. Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collection: Sample environmental surfaces (e.g., bed footboards) using foam sponges pre-moistened with a neutralizing buffer.

- Homogenization: Process samples using a stomacher method to create a 5 mL homogenate.

2. Sample Split and Pre-Treatment: The sponge homogenate is divided into three separate paths:

- T0 Sample: 500 µL of homogenate is added to 4.5 mL of Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB). DNA is extracted immediately from 500 µL of this mixture for a baseline (T0) qPCR analysis.

- T1 Sample: 500 µL of homogenate is added to 4.5 mL of TSB for incubation.

- Growth Negative Control (GNC): 500 µL of homogenate is added to 4.5 mL of 8.25% sodium hypochlorite (bleach) to kill all cells. It is left at room temperature for 10 minutes, centrifuged, washed twice with PBS, and then resuspended in 5 mL of TSB.

3. Incubation:

- Incubate T1 and GNC samples under species-specific conditions.

- For E. coli and S. aureus: 24 hours at 37°C, aerobically.

- For C. difficile: 48 hours at 37°C, anaerobically.

4. Post-Incubation Analysis:

- After incubation, transfer 500 µL from both T1 and GNC samples for DNA extraction and qPCR analysis (T1 qPCR).

- In parallel, culture 200 µL from all paths (T0, T1, GNC) on TSA agar to compare with culture-based results.

5. Criteria for Viability: A sample is considered viable for a target species if it meets any of the following conditions:

- It is detected at T0, and the qPCR cycle threshold (CT) value decreases by at least 1.0 at T1 compared to the GNC.

- It is undetected at T0 but is detected at T1, and is undetected in the GNC.

- It grows on standard culture agar [5].

Quantitative Data from Healthcare Environment Study

The following table summarizes key quantitative results from the prospective analysis of patient room samples, demonstrating the performance of culture-based viability PCR [5] [17].

| Pathogen | Samples with Detectable DNA (T0 or T1) | Samples with Viable Cells (via Viability PCR) | Samples with Viable Cells (via Culture) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (N=26) | 24 (92%) | 3 (13%) | 0 (0%) |

| S. aureus (N=26) | 11 (42%) | 8 (73%) | 5 (19%) |

| C. difficile (N=26) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Viability PCR

The following table lists key reagents and their critical functions in setting up and performing culture-based viability PCR experiments.

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB) | A general-purpose liquid growth medium used to enrich viable bacterial cells from the sample during incubation [5]. |

| Species-Specific Broth | In some protocols, specialized broths are used to optimize the growth of particular target organisms, such as C. difficile [17]. |

| Neutralizing Buffer | Used to pre-moisten sampling sponges; neutralizes residual disinfectants on surfaces to prevent them from killing microbes during sample collection [5]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) or PMAxx | Viability dyes used in some v-PCR approaches. They penetrate only dead cells with compromised membranes and bind DNA, preventing its amplification in subsequent PCR, thus ensuring only DNA from live cells is detected [18] [21]. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | A fluorescent dye used in qPCR that intercalates into double-stranded DNA, allowing for the quantification of amplified DNA in real-time [5]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | A modified enzyme that is inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup, which improves specificity and yield [19] [16]. |

| Sodium Hypochlorite | Used in the growth negative control (GNC) to kill microorganisms, providing a baseline to confirm that DNA detection after incubation is due to growth and not persistent DNA from dead cells [5]. |

Workflow and Troubleshooting Diagrams

Culture-Based Viability PCR Workflow

Systematic Troubleshooting for Low PCR Yield

The accurate detection of viable microbial cells is a cornerstone of public health, food safety, and pharmaceutical development. Traditional culture methods, while reliable, are often time-consuming and fail to detect viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) offers speed and sensitivity but cannot differentiate between live cells, dead cells, and free DNA, leading to overestimation of viable populations. Viability PCR (vPCR) and culture-based viability PCR have emerged as powerful techniques that bridge this gap, combining molecular speed with viability assessment. This technical support guide addresses the key challenges and solutions in establishing clear, reliable criteria for live cell identification using these advanced PCR methodologies, providing essential troubleshooting and protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Concepts: vPCR and Culture-Based Viability PCR

Viability PCR (vPCR)

Principle: vPCR uses photoactive DNA-intercalating dyes, such as propidium monoazide (PMA), to selectively suppress DNA amplification from dead cells [22] [23]. PMA enters only cells with compromised membranes (considered dead), intercalates into DNA, and forms covalent bonds upon light exposure, rendering the DNA unamplifiable. DNA from viable cells with intact membranes remains accessible for PCR amplification [22].

Key Limitation: The method relies solely on membrane integrity. It cannot detect viability after treatments that do not damage membranes (e.g., UV disinfection) but can detect VBNC cells [22].

Culture-Based Viability PCR

Principle: This method combines the sensitivity of species-specific quantitative PCR (qPCR) with the viability assessment of culture enrichment [5]. A sample is tested via qPCR at time zero (T0) and again after a period of incubation in growth media (T1). A significant decrease in the quantification cycle (CT) value at T1 indicates the presence of viable cells that have proliferated during incubation [5].

Advantage: It provides a functional assessment of viability based on the ability to proliferate, overcoming limitations of membrane-integrity assays.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary cause of false-positive results in vPCR, and how can it be minimized? False positives are primarily caused by incomplete suppression of DNA signals from a high background of dead cells [22]. Optimization strategies include using a double PMA treatment with a low dye concentration and ensuring proper light exposure by changing reaction tubes between the final dark incubation and light activation step to prevent shadowing effects [22] [24].

2. My vPCR shows no amplification. What are the first steps in troubleshooting? Begin by verifying your template DNA quality and concentration [19] [25]. Then, confirm that all PCR reagents were added correctly and have not degraded [25] [26]. Ensure that the photoactivation step for PMA was performed correctly with a functioning light source, as improperly inactivated PMA can inhibit PCR [22].

3. How does culture-based viability PCR confirm viability, and what defines a positive result? Viability is confirmed by demonstrating growth through a significant increase in target DNA. A sample is considered viable if [5]:

- It is detected at T0, and the CT value decreases by at least 1.0 at T1 compared to a growth-negative control.

- It is undetected at T0 but detected at T1, and the growth-negative control is negative.

4. I am getting non-specific bands or primer-dimer formations in my viability PCR. How can I resolve this? This is often due to suboptimal primer annealing [19] [26]. Solutions include:

- Increasing the annealing temperature in increments of 1-2°C.

- Using a hot-start polymerase to prevent non-specific amplification during reaction setup [19] [26].

- Redesigning primers to avoid self-complementarity and secondary structures [19].

- Lowering primer concentrations [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common vPCR and PCR Issues

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No or Low Amplification | Inhibitors present in sample (e.g., from food matrix) [19] | Purify template DNA; use additives like BSA [19]. |

| Suboptimal PCR conditions [25] [26] | Optimize Mg2+ concentration; use a gradient cycler to optimize annealing temperature [26]. | |

| Degraded or low-concentration template [25] | Re-prepare template DNA; increase number of PCR cycles [25]. | |

| Non-Specific Products / Primer-Dimer | Annealing temperature too low [19] [26] | Increase annealing temperature incrementally [26]. |

| Primer concentration too high [19] | Lower primer concentration within 0.05–1 µM range [26]. | |

| Non-specific priming during setup [26] | Use a hot-start DNA polymerase [19] [26]. | |

| Incomplete Suppression of Dead Cell Signal | High dead cell background [22] | Implement a double PMA treatment protocol [22] [24]. |

| Improper PMA photoactivation [22] | Change tube type between incubation and light exposure; ensure even light distribution [22]. | |

| Smeared Bands on Gel | Non-specific products from contaminated reagents [19] | Use fresh reagents; designate pre- and post-PCR work areas; consider new primer sequences [19]. |

| Excessive cycling or extension times [19] | Reduce cycle number or extension time [19]. |

Interpreting Signal Dynamics for Viability Criteria

| Method | Signal Indicative of Viable Cells | Signal Indicative of Non-Viable Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Viability PCR (vPCR) | Strong PCR signal in PMA-treated sample (DNA from membrane-intact cells is amplified). | PCR signal is suppressed in PMA-treated sample (DNA from membrane-compromised cells is blocked) [22]. |

| Culture-Based Viability PCR | CT value at T1 (after incubation) is significantly lower (e.g., decrease ≥1.0) than CT at T0 [5]. | CT value shows no significant change or increases between T0 and T1 [5]. |

| Standard qPCR | Cannot distinguish viability. Signal indicates presence of target DNA, regardless of its source (live, dead, or free DNA) [22] [5]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Optimized vPCR Protocol forStaphylococcus aureusin Food Matrices

This protocol, adapted from Dinh Thanh et al. (2025), successfully suppressed DNA from up to 5.0 × 10^7 dead cells in a 200 µl reaction [22] [24].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- PMA dye (e.g., PMAxx)

- Staphylococcus aureus strains

- Food matrices (e.g., ground spices, milk powder, meat)

- Buffered Peptone Water

- DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents

- Light-emitting device (PMA-Lite LED or equivalent)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Artificially contaminate food samples with a low number of viable cells and a high number of heat-inactivated cells [24].

- PMA Treatment:

- Add PMA to the sample to a final concentration of 10–50 µM.

- Incubate in the dark for 10–30 minutes with occasional mixing.

- Perform a tube change to a transparent, flat-bottom tube.

- Expose the sample to bright light for 15–30 minutes for photoactivation.

- Optional: Repeat the PMA treatment cycle (double PMA) for challenging matrices [22].

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from the PMA-treated sample using a commercial kit.

- PCR Amplification: Perform qPCR or standard PCR with species-specific primers. The absence of amplification from the heat-killed control indicates successful dead-cell suppression [22].

Culture-Based Viability PCR Protocol for Healthcare Pathogens

This protocol, used for detecting viable E. coli, S. aureus, and C. difficile on hospital surfaces, outperformed traditional culture methods [5].

Procedure:

- Sample Collection & Homogenization: Sample surfaces with sponges pre-moistened in neutralizing buffer. Process via stomacher to create a homogenate [5].

- Time-Zero (T0) Analysis:

- Add 500 µL of homogenate to 4.5 mL of Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB).

- From this mixture, take a 500 µL aliquot for immediate DNA extraction and qPCR analysis (T0 CT value).

- Incubation (T1):

- Add another 500 µL of the original homogenate to 4.5 mL of TSB.

- Incubate under species-specific conditions (e.g., 24-48 hours at 37°C).

- Growth-Negative Control (GNC):

- Treat a 500 µL homogenate aliquot with sodium hypochlorite to kill cells, wash, and then add to TSB. Incubate alongside T1 samples.

- Post-Incubation Analysis:

- After incubation, take 500 µL from both T1 and GNC samples for DNA extraction and qPCR (T1 CT value).

- Viability Assessment:

- Apply the criteria outlined in the FAQ section to interpret results (e.g., a CT decrease of ≥1.0 in T1 compared to GNC confirms viability) [5].

Workflow Diagrams

vPCR Workflow for Viability Assessment

Culture-Based Viability PCR Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Viability Assessment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | DNA-intercalating dye that selectively enters dead cells with compromised membranes; upon photoactivation, it covalently binds DNA and inhibits PCR amplification [22] [23]. | Concentration and incubation conditions are critical; requires optimization for different sample matrices [22]. |

| Growth Media (e.g., TSB, BVFH) | Supports the proliferation of viable cells during incubation in culture-based viability PCR, enabling detection of growth through increased DNA signal [5] [27]. | Must be tailored to the specific microorganism (e.g., BVFH for Francisella tularensis) [27]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until high temperatures are reached during PCR initialization [19] [26]. | Essential for improving the specificity and sensitivity of the final PCR readout. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., BSA, DMSO) | Helps overcome PCR inhibition caused by compounds co-extracted from complex sample matrices (e.g., spices, humic acid) [19] [27]. | BSA can bind inhibitors; DMSO improves amplification efficiency for GC-rich templates [19] [25]. |

Implementing Culture-Based Viability PCR: Step-by-Step Protocols for Diverse Pathogens and Matrices

Culture-based viability PCR (vPCR) represents a significant advancement in pathogen detection for clinical and food safety diagnostics. This method bridges the gap between traditional culture-based techniques, which confirm viability but are slow, and quantitative PCR (qPCR), which is rapid but cannot distinguish between live and dead cells [5]. The core principle involves comparing qPCR results before and after incubation in growth media to determine whether detected organisms can proliferate, thereby combining molecular sensitivity with viability assessment [5]. The sensitivity and accuracy of this technique are profoundly influenced by sample processing and enrichment strategies, particularly the selection of enrichment broth and optimization of incubation conditions. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help researchers optimize these critical parameters within their viability PCR workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental principle behind culture-based viability PCR? Culture-based viability PCR detects viable pathogens by harnessing the sensitivity of PCR while incorporating a viability assessment. The process involves running a species-specific qPCR assay on a sample both immediately (T0) and after a period of incubation (T1) in a nutrient broth. A sample is considered viable if the cycle threshold (CT) value decreases significantly after incubation, indicating microbial growth and DNA amplification, or if the target is undetected at T0 but detected at T1 [5]. This approach outperforms traditional culture methods in detection sensitivity while providing the viability information that standard qPCR lacks [5].

2. Why is broth enrichment critical before PCR in this assay? Broth enrichment is a crucial step because it allows viable but potentially stressed or low-abundance cells to proliferate. This incubation period amplifies the target DNA to detectable levels, dramatically increasing the assay's sensitivity. Research shows that broth enrichment can enable the detection of pathogens via culture methods at T1 that were completely undetectable by direct culture at T0 [5]. Furthermore, for the viability PCR result to be valid, a growth negative control (GNC), often treated with a sterilizing agent like sodium hypochlorite, must be included to confirm that signals are due to viable growth and not persistent DNA [5].

3. How do sample matrices interfere with viability PCR results? The sample matrix can significantly impact the performance of viability PCR assays. Complex matrices, especially those with high organic content or particulate matter, can interfere with the assay in two primary ways: they can shield dead cells from viability dyes, leading to false-positive signals, and they can inhibit the PCR reaction itself, causing false negatives [24] [28]. For instance, studies on spiked stool samples have shown that samples with more solid matter (semi-solid stools) removed less dead-cell DNA and detected less live-cell DNA compared to samples with less solid matter (liquid stools) [28]. The consistency and concentration of the sample suspension are therefore critical factors to optimize.

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common Issues and Solutions in Culture-Based Viability PCR

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| False Positive Signals | Incomplete suppression of DNA from dead cells; High load of non-viable organisms [24]. | Optimize viability dye (e.g., PMA/PMAxx) concentration and incubation; Implement a double dye treatment protocol; Include a rigorous growth negative control (GNC) [5] [24]. |

| Low Sensitivity / False Negatives | PCR inhibition from sample matrix; Suboptimal broth composition or incubation conditions; Insufficient incubation time [24] [28]. | Dilute sample to reduce inhibitors; Use DNA polymerases with high processivity and inhibitor tolerance; Validate and optimize broth type, temperature, and atmosphere for the target organism [16] [24]. |

| Poor Bacterial Growth in Broth | Incorrect incubation temperature or atmosphere; Inappropriate broth selection; Overly aggressive sample processing damaging cells. | Confirm species-specific incubation conditions (e.g., 37°C, aerobic/anaerobic); Use general-purpose enrichment broths like Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB); Ensure gentle sample processing methods [5] [29]. |

| Inconsistent qPCR Results | Suboptimal DNA extraction; PCR inhibitors carried over from broth or sample; Inconsistent thermal cycling [16]. | Re-purify DNA to remove inhibitors like salts or organics; Optimize denaturation time/temperature for complex templates; Validate primer specificity and annealing temperature [16] [30]. |

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Culture-Based Viability PCR for Environmental Samples

This protocol, adapted from a study on healthcare surface monitoring, is designed for detecting viable bacterial pathogens like E. coli, S. aureus, and C. difficile [5].

- Sample Collection: Collect surface samples using foam sponges pre-moistened with a neutralizing buffer.

- Sample Processing: Process samples via a stomacher method to create a homogenate.

- Sample Splitting: Divide the homogenate into three paths:

- T0: Combine with Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB), then immediately perform DNA extraction and qPCR.

- T1: Combine with TSB and incubate under species-specific conditions (e.g., 24-48 hours at 37°C, aerobic or anaerobic).

- GNC (Growth Negative Control): Treat with sodium hypochlorite to kill cells, then wash and resuspend in TSB before incubation.

- Post-Incubation Analysis: After incubation, perform DNA extraction and qPCR on T1 and GNC samples.

- Viability Assessment: A sample is viable if: a) detected at T0 and the CT value decreases by ≥1.0 at T1 compared to GNC, b) undetected at T0 but detected at T1 and undetected in GNC, or c) growth is confirmed by parallel culturing on agar plates [5].

Protocol 2: Enhanced Viability PCR with PMAxx for Complex Matrices

This optimized protocol for S. aureus detection in food focuses on eliminating false positives from dead cells and can be adapted for other complex samples [24].

- Sample Preparation: Create a homogenate of the food or clinical sample.

- First PMAxx Treatment: Add PMAxx dye to the sample and incubate in the dark to allow dye penetration into dead cells.

- Tube Change: Transfer the sample to a new, clear reaction tube. This critical step prevents dead cell debris from adhering to tube walls and avoiding light exposure.

- Photoactivation: Expose the sample to bright visible light to cross-link the dye with DNA from dead cells, preventing its amplification.

- Second PMAxx Treatment: Perform a second, low-concentration treatment of PMAxx with another dark incubation and photoactivation cycle to ensure complete dead-cell DNA suppression.

- DNA Extraction & qPCR: Proceed with DNA extraction and quantitative PCR. The optimized protocol can completely suppress DNA signals from up to 5.0 × 10^7 dead cells in a pure culture [24].

Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Viability PCR

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB) | General-purpose liquid enrichment medium for bacterial growth. | Used for incubating samples between T0 and T1 qPCR assays to support proliferation of viable cells [5]. |

| Viability Dyes (PMA, PMAxx) | Photoactive DNA-intercalating dye that penetrates dead cells with compromised membranes. | Covalently binds to DNA upon light exposure, suppressing its amplification in PCR. Critical for differentiating viable and dead cells [24] [28]. |

| Neutralizing Buffer | Used in sampling to neutralize disinfectants or other inhibitory agents from surfaces. | Prevents carry-over of antimicrobial agents that could inhibit growth during broth enrichment [5]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR that remains inactive until a high-temperature activation step. | Increases specificity by preventing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation at low temperatures [16]. |

| Species-Specific Primers | Short DNA sequences designed to bind to and amplify unique target pathogen DNA. | Essential for the specificity of the qPCR assay. Must be validated for the target organism [5]. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | A fluorescent dye that binds to double-stranded DNA for real-time PCR detection. | Allows for real-time monitoring of DNA amplification during qPCR [5]. |

Culture-based viability PCR (vPCR) is an advanced method that combines the sensitivity of molecular detection with the ability to confirm cell viability, which is crucial for accurate risk assessment in pharmaceutical, diagnostic, and food safety industries. This technique involves taking samples at critical time points—before (T0) and after (T1) a incubation period in growth media—and using species-specific qPCR to determine if detected organisms can proliferate [5]. A fundamental challenge, however, is that the diverse cellular structures of different bacteria require tailored experimental approaches to achieve accurate and sensitive results.

This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and protocols to address the specific needs of Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria, and bacterial spore-formers when using culture-based vPCR.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: Why do my viability PCR results show high background signal from dead cells?

This is a common issue where DNA from dead cells with compromised membranes is amplified, leading to overestimation of viable counts.

- Primary Cause: The viability dye (e.g., PMA) failed to penetrate and sufficiently suppress DNA amplification from dead cells.

- Solutions:

- For Gram-positive bacteria: Increase the dye concentration or incubation time. Their thick peptidoglycan layer is a major barrier to dye entry [24].

- Implement a double dye treatment: A second round of dye application and photoactivation can significantly improve suppression of dead cell signals, especially in samples with a high proportion of dead cells [24].

- Optimize the photoactivation step: Ensure the light source is bright enough and the exposure time is sufficient to fully activate the dye. Changing reaction tubes between the final dark incubation and light exposure step can minimize light scattering and improve efficacy [24].

- Review sample matrix effects: Components in food, environmental, or pharmaceutical samples can inhibit dye function. You may need to dilute the sample or add a wash step [24].

Q2: My protocol works for E. coli but fails for S. aureus. What should I adapt?

This indicates that species-specific adaptations are required, particularly due to differences in cell wall structure.

- Primary Cause: Gram-positive bacteria like S. aureus have a thick, multi-layered peptidoglycan cell wall that hinders the penetration of viability dyes like PMA, unlike the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria [24].

- Solutions:

- Adjust viability dye protocol: For Gram-positives, consider a higher PMA concentration or longer incubation. For Gram-negatives, a standard concentration is often sufficient, but excess dye can reduce signal from live cells.

- Extend incubation times: The growth (T1) incubation period may need to be longer for slower-growing or more fastidious species. For example, while E. coli and S. aureus might be incubated for 24 hours, spore-formers like C. difficile require 48 hours of anaerobic incubation [5].

- Verify growth media and conditions: Ensure the culture broth (e.g., Trypticase Soy Broth) and atmosphere (aerobic vs. anaerobic) are optimal for your target organism [5] [31].

Q3: How can I detect viable spore-formers, which are often dormant?

Detecting bacterial spores requires a protocol that triggers germination, as the spore coat is highly impermeable.

- Primary Cause: Spores are dormant structures with extreme resistance. Standard viability dyes and lysis methods cannot penetrate the protective spore coat, and the DNA inside is not amplified until the spore germinates into a vegetative cell [5].

- Solutions:

- Use an extended enrichment step: The T1 incubation in growth media must be long enough to allow spores to germinate and outgrow. For C. difficile, this requires 48 hours of anaerobic incubation [5].

- Apply viability dyes after enrichment: The dye should be added after the T1 incubation, as it will only penetrate the membranes of spores that have germinated or dead vegetative cells, preventing false positives from free DNA or dormant spores.

Experimental Protocols for Different Bacterial Types

The following workflows and reagent kits are designed to address the structural and physiological differences between bacterial types.

Workflow for Gram-Negative Bacteria (e.g., E. coli)

Gram-negative bacteria have an outer membrane that is more permeable to small molecules, making them relatively straightforward for vPCR.

Workflow for Gram-Positive Bacteria (e.g., S. aureus)

The thick peptidoglycan layer of Gram-positive bacteria necessitates a more aggressive dye treatment step.

Workflow for Spore-Formers (e.g., C. difficile)

Spore-formers require an extended incubation period under specific conditions to trigger germination.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential reagents and their optimized use for different bacterial types in culture-based vPCR.

| Reagent/Kit | Function in Protocol | Species-Specific Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | Viability dye; penetrates dead cells with compromised membranes, binding DNA upon light exposure to prevent PCR amplification [24]. | Gram-negative: Standard concentration (e.g., 25 µM). Gram-positive: Use higher concentration (e.g., 50 µM) or extend incubation time to overcome peptidoglycan barrier [24]. |

| Growth Broth (e.g., TSB) | Enrichment medium to support the proliferation of viable cells during the T1 incubation step [5]. | General: Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB) is versatile. Fastidious species: May require enriched media with blood, serum, or specific supplements [31]. |

| DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5, OneTaq) | Enzyme for PCR amplification during qPCR steps. Critical for sensitivity and specificity [32]. | GC-rich genomes: Use polymerases like Q5 with GC enhancers. Complex samples: Polymerases with high processivity tolerate inhibitors from sample matrices [16]. |

| Species-Specific Primers | Oligonucleotides that bind to unique genetic sequences of the target bacterium for specific detection via qPCR [5]. | All species: Must be designed and validated for the specific target organism. Verify sequence specificity and optimize concentration (typically 0.1–1 µM) [32] [16]. |

Data Presentation: Comparative Performance

The following data, adapted from a clinical study, demonstrates how culture-based vPCR outperforms traditional culture methods and standard qPCR in detecting viable pathogens.

Table 1: Comparison of Pathogen Detection Methods in Clinical Environmental Samples [5]

| Method | Target Species | Detected at T0/T1 | Determined Viable | Statistically Significant vs. Culture? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-based vPCR | E. coli (N=26) | 24 (92%) | 3 (13%) | Yes (P < 0.01) |

| Traditional Culture | E. coli (N=26) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | (Baseline) |

| Culture-based vPCR | S. aureus (N=26) | 11 (42%) | 8 (73%) | Yes (P < 0.01) |

| Traditional Culture | S. aureus (N=26) | 0 (0%) | 5 (19%)* | (Baseline) |

| Culture-based vPCR | C. difficile (N=26) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) | Not Applicable |

| Traditional Culture | C. difficile (N=26) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | (Baseline) |

Note: *These 5 samples were only detected by culture after broth enrichment (T1), and all were also correctly identified as viable by the vPCR method [5].

For researchers in drug development and microbiology, accurately distinguishing live pathogens from dead ones is critical for assessing environmental contamination and therapeutic efficacy. While quantitative PCR (qPCR) offers a fast and sensitive method for detecting pathogens, a significant limitation is its inability to differentiate between viable and non-viable cells, as it amplifies DNA from both sources. This can lead to an overestimation of live bacteria and potentially false-positive results [5] [33]. Culture-based viability PCR and dye-based methods like PMA treatment have emerged as powerful techniques that combine the sensitivity of qPCR with the ability to assess cell viability, thereby improving the specificity of your research outcomes [5] [33].

Core Methodologies and Workflows

Culture-Based Viability PCR

This method involves using species-specific qPCR before and after a broth enrichment incubation step to determine if detected organisms can proliferate. The decrease in quantification cycle (Cq) values after incubation indicates the presence of viable, multiplying cells [5] [17].

Experimental Protocol [5] [17]:

- Sample Collection: Collect environmental samples (e.g., with foam sponges premoistened in neutralizing buffer) and process them into a homogenate.

- Initial (T0) qPCR: Add a portion of the homogenate (e.g., 500 µL) to a growth broth. Immediately subject part of this mixture to DNA extraction and species-specific qPCR to establish a baseline Cq value.

- Broth Enrichment: Add another portion of the homogenate to growth broth and incubate under species-specific conditions (e.g., 24-48 hours at 37°C).

- Growth Negative Control (GNC): Treat a separate portion of the homogenate with sodium hypochlorite to destroy viable cells, then wash and resuspend in growth broth. This control helps account for non-viable DNA.

- Post-Incubation (T1) qPCR: After incubation, perform DNA extraction and qPCR on both the enriched sample (T1) and the GNC.

- Viability Interpretation: A sample is considered viable if:

- It is detected at T0, and the Cq value at T1 decreases by at least 1.0 compared to the GNC, or

- It is undetected at T0 but detected at T1 and undetected in the GNC.

The diagram below illustrates this workflow:

Propidium Monoazide (PMA) Viability qPCR

PMA is a DNA-intercalating dye that penetrates only membrane-compromised (dead) cells. Upon photoactivation, the dye covalently binds to DNA, inhibiting its amplification in subsequent qPCR. This selectively eliminates signals from dead cells [33].

Experimental Protocol [33]:

- Sample Treatment: Add PMA to the sample (e.g., biofilm or bacterial suspension).

- Photoactivation: Expose the sample to bright light. This step cross-links PMA to the DNA within dead cells.

- DNA Extraction: Perform standard DNA extraction. The cross-linked DNA from dead cells is either removed or not amplified.

- qPCR: Perform qPCR. The signal predominantly represents DNA from viable cells with intact membranes.

The diagram below illustrates the mechanism of PMA-qPCR:

Troubleshooting Guides

DNA Extraction and Purification FAQs

Q1: My DNA yield is low from plant tissues. What method should I use? The CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) extraction method is highly recommended for plant tissues. It effectively removes common interfering compounds like polysaccharides and polyphenols. The protocol can be further optimized by adjusting salt concentrations to differentially precipitate polysaccharides, and may be combined with a phenol/chloroform or solid-phase cleanup step to remove proteins [34].

Q2: I need high-quality plasmid DNA for cloning. What is the best purification method? Anion-exchange chromatography is a widely used method for plasmid DNA purification. It leverages the negative charge of DNA to bind it to a positively charged resin, effectively separating plasmid DNA from impurities like RNA and proteins. This method yields high-quality, pure DNA suitable for sensitive downstream applications like cloning and sequencing [34].

Q3: What is the fastest DNA extraction method for high-throughput workflows? Magnetic bead-based purification is a modern, efficient method ideal for high-throughput applications. The process involves binding DNA to functionalized magnetic beads, which are then separated using a magnetic field. This method is easily automated, provides high DNA purity with minimal contamination, and eliminates the need for centrifugation [34].

qPCR Setup and Plastic Consumables Troubleshooting

Q4: I am observing low or no amplification in my qPCR. What could be wrong?

- PCR Inhibitors: Dilute your template DNA to dilute away potential PCR inhibitors [35].

- Suboptimal Plastic Consumables: Ensure your PCR tubes/plates have uniform, thin walls for optimal thermal conductivity, especially for fast qPCR protocols. Verify they are compatible with your thermal cycler's block [36].

- Reagent or Template Issues: Confirm that reagents have not expired and are stored correctly. Check the quality and concentration of your DNA or RNA template [37].

Q5: My no-template control (NTC) shows amplification. How do I fix this?

- Contamination: Clean your work area and pipettes with 70% ethanol or 10% bleach. Replace all stocks and reagents. Consider using a master mix containing UDG (uracil-DNA glycosylase) to eliminate carryover contamination from previous PCR products [37].

- Splash Contamination: Be cautious when pipetting template to prevent splashing into adjacent wells. Place NTC wells away from sample wells on the plate [35].

- Primer-Dimer: Redesign primers with a Tm around 60°C. Include a dissociation curve at the end of cycling to check for primer-dimer formation, which typically shows a peak at a lower temperature than your specific amplicon [37].

Q6: I have high well-to-well variation in my qPCR data. What should I check?

- Improper Sealing: Ensure the qPCR plate is properly sealed with an optically clear film to prevent evaporation, which can cause significant variation. Press the film firmly along all edges and around well rims [36].

- Pipetting Errors: Ensure proper pipetting technique and mix reagents thoroughly before dispensing. Centrifuge the plate before running to eliminate bubbles that can interfere with fluorescence reading [37].

- Plate Selection: For qPCR, select plates with white wells instead of clear wells. White wells reduce signal crosstalk between adjacent wells, improving well-to-well consistency [36].

Viability-Specific Method Troubleshooting

Q7: My PMA treatment failed to completely suppress the signal from dead cells. Why?

- PMA Uptake Efficiency: PMA uptake can be less efficient in some cell types or if the dead cell population is very high. Optimize the PMA concentration and incubation time for your specific sample matrix [33].

- Photoactivation Step: Ensure even and sufficient photoactivation of the sample. Incomplete light exposure will fail to cross-link PMA to all dead cell DNA [33].

- PCR Target: Target single-copy genes and design longer amplicons. This increases the likelihood that the target sequence in dead cells is successfully modified by PMA, thereby inhibiting amplification [33].

Q8: After sodium hypochlorite disinfection, PMA-qPCR still shows some signal. Does this mean the disinfectant failed? Not necessarily. Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) can directly affect DNA and inhibit subsequent PCR amplification, even in samples without PMA. In such cases, the signal detected by PMA-qPCR may not originate from intact, viable cells but from PCR inhibition or other artifacts. It is crucial to include appropriate controls to interpret these results correctly [33].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Viability PCR Research

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Prolidium Monoazide (PMA) | DNA-intercalating dye that selectively suppresses amplification from dead cells [33]. | Optimize concentration for specific sample type. Requires photoactivation step. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Fluorescent dye for detecting double-stranded DNA PCR products [5] [33]. | Requires a dissociation curve analysis to verify amplicon specificity. |

| TaqMan Probe Master Mix | Enzyme and buffer system for probe-based qPCR detection [33]. | Offers higher specificity than SYBR Green; requires design of a target-specific probe. |

| DNase I | Enzyme that degrades DNA [37]. | Treat RNA samples to remove genomic DNA contamination before reverse transcription. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease [34]. | Used in lysis buffers to digest proteins and nucleases during DNA extraction. |

| Silica-column Kits | For solid-phase DNA purification via bind-wash-elute mechanism [34]. | Provide fast, high-quality DNA; ideal for routine molecular applications. |

| Magnetic Bead Kits | For automated, high-throughput nucleic acid purification [34]. | Enable scalable processing without centrifugation. |

| UDG (Uracil-DNA Glycosylase) | Enzyme that prevents PCR carryover contamination [37]. | Incorporated into some master mixes to degrade uracil-containing prior amplicons. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Viability Assessment Methods from Cited Studies

| Study/Method | Target | Key Finding | Quantitative Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture-Based Viability PCR [5] | S. aureus | Detected more viable pathogens than traditional culture. | 73% (8/11) viable via qPCR vs. 0% (0/11) via culture alone. |

| Culture-Based Viability PCR [5] | E. coli | Detected viable cells missed by culture. | 13% (3/24) viable via qPCR vs. 0% (0/24) via culture alone. |

| PMA-qPCR on Biofilm [33] | Multi-species oral biofilm | PMA reduced PCR counts after chlorhexidine treatment. | 1 to 1.6 log10 reduction in PCR counts, bringing them closer to CFU counts. |

| PMA-qPCR [33] | F. nucleatum | PMA-qPCR can detect more bacteria than culture. | After disinfection, PMA-qPCR detected significantly more F. nucleatum than culture methods. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the essential controls for a viability PCR (vPCR) experiment? Essential controls for a vPCR experiment include live cell samples, heat-killed cell samples, and a no-template control (NTC). The live cell sample confirms that the procedure can detect the target, while the heat-killed cell sample verifies that the viability dye (e.g., PMAxx) is effectively suppressing the DNA signal from dead cells. The NTC checks for contamination in your reagents [38].

Q2: How many biological replicates are recommended for vPCR experiments? It is recommended to use a minimum of 5 biological replicates for vPCR experiments. This practice increases the statistical power and reliability of your results, making the data more robust [38].

Q3: My vPCR assay shows high false-positive signals from dead cells. How can I improve this? High false-positive signals often indicate that the viability dye treatment is not optimal. You can try increasing the concentration of the viability dye (e.g., PMAxx) or extending the dark incubation time before photoactivation. Furthermore, incorporating a eukaryotic cell lysis step can reduce interference from complex sample matrices like blood, improving dye efficiency [38].

Q4: Why is there no amplification or low yield in my PCR? Low or no product yield can be due to several factors: reagents may have been omitted or are compromised, the primer design might be inefficient, the template DNA could be of poor quality or concentration, or the annealing temperature may be incorrect. Check that all reaction components are fresh and present, and verify your primer sequences and thermal cycler program [20].

Q5: What does non-specific amplification in my qPCR results indicate? Non-specific amplification, such as multiple peaks in a melt curve, is frequently caused by primer-dimers, non-specific primer binding, or suboptimal salt conditions. Solutions include increasing the annealing temperature, optimizing magnesium salt concentration, using a hot-start polymerase, or redesigning the primers for greater specificity [20] [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Viability PCR (vPCR) Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient dead-cell signal suppression | Viability dye (PMA/PMAxx) concentration too low or incubation time too short. | Increase dye concentration (e.g., to 25 µM or higher) or extend dark incubation time [38]. |

| Complex sample matrix (e.g., blood, stool) interfering with dye binding. | Add a eukaryotic cell lysis step prior to dye treatment to reduce background interference [38]. | |

| High variation between replicates | Inconsistent sample preparation or low number of replicates. | Standardize the sample processing protocol and use at least 5 biological replicates [38]. |

| Poor live-cell detection | High concentration of stool matter or other PCR inhibitors. | Use a lower concentration of the sample (e.g., 5% stool suspension) to minimize inhibition [28]. |

| False positives in No-Template Control (NTC) | Contaminated reagents. | Use fresh, aliquoted reagents and work in a dedicated, clean pre-PCR area [20]. |

Guide 2: General qPCR Troubleshooting

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No amplification | Omitted reagents, incorrect program, poor template quality. | Verify all reaction components, check the thermal cycler program, and re-assess template quality/purity [20]. |

| Non-specific amplification (multiple bands) | Annealing temperature too low, excessive primer concentration. | Perform a temperature gradient to optimize annealing; titrate primer concentration (0.05-1 µM) [20]. |

| Poor amplification efficiency | PCR inhibitors, suboptimal primer design, limiting reagents. | Purify the template DNA, check primer design for specificity, and ensure fresh reaction mixes [39]. |

| Amplification in NTC | Contaminated primers, probes, or water. | Prepare fresh reagent aliquots and use ultrapure, sterile water [20] [39]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol 1: Optimized vPCR Workflow for Bacterial Detection in Blood

This protocol is adapted from research on detecting E. coli in whole blood [38].

- Spike and Lyse: Spike 1 mL of commercial blood with the bacterial sample. Add 3 mL of commercial red blood cell (RBC) lysis solution. Mix and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes.

- Deplete Host DNA: Centrifuge to pellet cells. Resuspend the pellet in 200 µL PBS, then add 1 mL of Host DNA Depletion Solution. Incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes.

- Pelleting and PMA Treatment: Collect bacterial cells by centrifugation. Resuspend the pellet in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth. Add PMA or PMAxx dye to a final concentration of 25 µM. Incubate in the dark with rotation for 15 minutes.

- Photoactivation: Expose the sample to light for 20 minutes using a dedicated PMA lite device to activate the dye.

- DNA Extraction and qPCR: Extract DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit). Perform qPCR with target-specific primers.

Protocol 2: vPCR for Detection in Stool Samples

This protocol is adapted from a study on detecting Salmonella in diarrheal stools [28].

- Prepare Stool Suspension: Create a 5% stool suspension in an appropriate buffer. Higher stool concentrations can inhibit the assay and increase background.

- Spike and Treat: Spike the stool suspension with the target bacteria. Add PMAxx dye (testing concentrations between 100-200 µM) and incubate in the dark (10-30 minutes).

- Photoactivation: Expose the sample to light to activate PMAxx.

- DNA Extraction and qPCR: Proceed with standard DNA extraction and qPCR protocols.

Quantitative Data from vPCR Studies

Table 1: Performance Metrics of an Optimized vPCR Assay for E. coli in Blood [38]

| Parameter | Sample Type (in Blood) | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit of Detection (LOD) | Live cells only | 10² CFU/mL |

| Live + Heat-killed cells | 10² CFU/mL | |

| Linear Range of Quantification | Live cells only | 10² to 10⁸ CFU/mL (R² = 0.997) |

| Live + Heat-killed cells | 10³ to 10⁸ CFU/mL (R² = 0.998) | |

| Bias vs. Plate Count (Log₁₀ CFU/mL) | Live cells only | +1.85 |

| Live + Heat-killed cells | +1.98 |

Table 2: Effect of Stool Concentration on vPCR Assay Performance [28]

| Stool Consistency | Stool Concentration | Effect on HK-cell DNA Removal | Effect on Live-cell DNA Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Stool | 5%, 10%, 20% | Similar efficiency across concentrations | Similar efficiency across concentrations |

| Semi-Solid Stool | 5% | Good removal (Higher Ct value) | Good detection (Lower Ct value) |

| 20% | Poor removal (Lower Ct value) | Reduced detection (Higher Ct value) |

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Viability PCR Workflow

vPCR Experimental Controls

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Viability PCR Research

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Viability Dye (PMA/PMAxx) | Penetrates membrane-compromised (dead) cells and binds DNA, preventing its amplification during PCR. | PMAxx is a next-generation dye with improved performance [38] [28]. |

| Eukaryotic Lysis Buffer | Lyses red blood cells and other host cells in a sample, reducing background and improving dye efficiency. | A critical step for complex samples like whole blood [38]. |