AFM Cantilever Functionalization for Biofilm Receptor Studies: Protocols, Applications, and Advanced Techniques

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on functionalizing Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) cantilevers to study specific receptor interactions within bacterial biofilms.

AFM Cantilever Functionalization for Biofilm Receptor Studies: Protocols, Applications, and Advanced Techniques

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on functionalizing Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) cantilevers to study specific receptor interactions within bacterial biofilms. It covers foundational principles, from the role of AFM in quantifying nanoscale adhesion forces to the selection of functionalization chemistry. Detailed, step-by-step protocols for common techniques like chemical vapor deposition and probe preparation are included. The guide also addresses frequent troubleshooting challenges and outlines rigorous methods for validating functionalized probes. By enabling precise measurement of biofilm adhesion mechanics and receptor-ligand binding events, these advanced AFM techniques are pivotal for developing novel anti-biofilm strategies and therapeutics.

Principles and Purpose: Why Functionalize AFM Cantilevers for Biofilm Research?

The Critical Role of AFM in Quantifying Biofilm Adhesion and Mechanics

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has established itself as a cornerstone technique in biofilm research, providing unprecedented capability to quantify the adhesion forces and mechanical properties of microbial communities at the nanoscale. Unlike conventional microscopy techniques, AFM operates by scanning a sharp probe across a sample surface to feel topographical features and measure interaction forces at resolutions down to a billionth of a meter [1]. This unique capability allows researchers to investigate bacterial biofilms—resilient microbial communities that grow on surfaces and cause infections, clog pipes, damage equipment, and disrupt ecosystems [1]. The technique's compatibility with diverse environments, including liquid conditions that preserve the native state of biological samples, makes it particularly valuable for studying hydrated biofilm structures [2] [3].

A significant recent advancement in the field is the development of automated large-area AFM platforms, which have overcome the traditional limitation of AFM's narrow field of view. As noted by researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, "In biofilm research, we've often been able to see the trees, but not the forest... Using the AFM, we could examine individual bacterial cells in detail but not how they organize and interact as communities" [1]. This new approach connects detailed observations at the level of individual bacterial components with broader views that cover millimeter-scale areas, providing an unprecedented view of biofilm organization [1] [4]. Furthermore, the integration of machine learning with AFM has revolutionized data analysis, enabling automated processing of thousands of individual cells to generate detailed maps of cellular properties across extensive surface areas [1] [4].

Quantifying Biofilm Adhesion Forces

Fundamental Principles of Adhesion Force Measurement

AFM quantifies biofilm adhesion forces through force-distance curve measurements, where a cantilever with a sharp tip is approached toward and retracted from the sample surface while monitoring cantilever deflection [3] [5]. According to Hooke's law (F = k × d), the adhesion force is calculated from the cantilever's spring constant (k) and its vertical deflection (d) [5]. These measurements capture both specific interactions (e.g., receptor-ligand binding) and non-specific interactions (e.g., van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions) that govern bacterial attachment to surfaces [6] [7].

Advanced AFM techniques such as Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS) and Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS) have emerged as powerful tools for probing adhesion mechanisms at different scales. SCFS involves attaching a single bacterial cell to the AFM cantilever to measure its interaction with substrates or other cells, typically revealing forces in the nanonewton range [6] [8]. SMFS focuses on individual molecular interactions, such as receptor-ligand binding, with force sensitivities reaching the piconewton level [6] [5].

Experimental Data on Bacterial Adhesion

Table 1: Quantified Adhesion Forces of Bacterial Species on Various Surfaces

| Bacterial Species | Surface Type | Average Adhesion Force | Experimental Conditions | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Titanium (hydrophilic) | Increased with time | SCFS in liquid medium | [7] |

| Streptococcus sanguinis | Titanium (Ra < 1 µm) | Increased with time | SCFS in liquid medium | [7] |

| Escherichia coli (wild-type) | Glass | Variable within population | Colloidal probe FSCS | [8] |

| Escherichia coli (LPS-removed) | Glass | Substantially diminished | Colloidal probe FSCS, EDTA-treated | [8] |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | PFOTS-treated glass | Flagella-mediated attachment | Large-area AFM imaging | [4] |

Recent research has revealed that bacterial populations exhibit significant heterogeneity in adhesion properties at the single-cell level. A 2025 study on Escherichia coli demonstrated that partial removal of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) by EDTA treatment substantially altered the bacterial cell surface, "diminishing both adhesion forces and cell elasticity" and markedly reducing cell-to-cell heterogeneity [8]. This finding highlights the essential role of LPS in modulating bacterial surface interactions and underscores the value of single-cell analysis techniques like AFM.

The temporal dynamics of bacterial adhesion have also been investigated through AFM studies. Research on Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus sanguinis adhesion to titanium surfaces demonstrated that adhesion strength increases with time, with hydrophilicity favoring the formation of hydrogen bonds between bacteria and substrate [7]. This time-dependent strengthening of adhesion underscores the importance of early intervention strategies for biofilm prevention.

Probing Biofilm Mechanical Properties

Nanomechanical Characterization Techniques

AFM enables comprehensive characterization of the nanomechanical properties of biofilms through force spectroscopy and nanoindentation experiments. By analyzing the cantilever's deflection during indentation, researchers can extract key mechanical parameters including stiffness (Young's modulus), viscoelasticity, and turgor pressure [3] [5]. These properties are crucial for understanding biofilm stability, resistance to mechanical disruption, and adaptation to environmental stresses.

The mechanical integrity of bacterial cells is determined by both the peptidoglycan layer and the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria [8]. AFM studies have revealed that "chemical or genetic alterations to the outer membrane markedly enhance cell envelope deformation under mechanical loading" [8], highlighting the importance of membrane components in maintaining cellular mechanical properties.

Mechanical Property Data Across Bacterial Species

Table 2: Measured Mechanical Properties of Bacterial Cells and Biofilms

| Bacterial Species/Structure | Mechanical Property | Measurement Technique | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (wild-type) | Cell elasticity | Colloidal probe FSCS | High cell-to-cell heterogeneity | [8] |

| Escherichia coli (LPS-removed) | Cell elasticity | Colloidal probe FSCS | Reduced heterogeneity and stiffness | [8] |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilm | Structural organization | Large-area AFM | Honeycomb-like cellular patterns | [4] |

| Resistant bacterial strains | Cell wall stiffness | AFM nanoindentation | Generally higher stiffness and thickness | [5] |

| Biofilm matrix | Viscoelastic properties | AFM force spectroscopy | Determines structural stability | [5] |

The connection between mechanical properties and biofilm function has been elucidated through AFM studies. Research has demonstrated that bacteria with varied biophysical properties, such as rigidity and adhesion, can efficiently colonize diverse surfaces, enhancing population-level fitness [8]. Furthermore, specific mechanical characteristics have been linked to antimicrobial resistance, as "resistant bacterial strains in general elicit greater stiffness and thickness" in their cell walls, which can deter intracellular traffic of antimicrobial molecules [5].

Large-area AFM imaging has revealed intriguing organizational patterns in biofilms that likely influence their mechanical robustness. Studies of Pantoea sp. YR343 have shown that "bacteria align in honeycomb-like patterns, interconnected by flagella," which researchers hypothesize may "play a part in strengthening biofilm cohesion and adaptability" [1] [4]. These structural insights provide new targets for disrupting biofilm integrity.

Application Notes: Protocol for AFM-Based Analysis of Biofilm Adhesion

Cantilever Functionalization and Probe Preparation

Objective: To functionalize AFM cantilevers for consistent quantification of biofilm adhesion forces. Materials:

- Silicon or silicon nitride AFM cantilevers (spring constant: 0.01-0.1 N/m for single-cell work)

- Poly-L-lysine (PLL), polydopamine, or polyethyleneimine solutions for bacterial immobilization

- Bacterial culture in appropriate growth medium

- Glutaraldehyde (2.5%) for chemical fixation (optional)

- Gelatin-coated glass surfaces for sample immobilization

Procedure:

- Cantilever Cleaning: Expose cantilevers to oxygen plasma for 2-5 minutes or ultraviolet ozone treatment for 20 minutes to remove organic contaminants.

Surface Functionalization: Immerse cantilevers in poly-L-lysine solution (0.1% w/v) for 30 minutes at room temperature to create a positively charged surface for bacterial attachment. Alternatively, use polydopamine coating for improved biocompatibility [7].

Bacterial Immobilization: Incubate functionalized cantilevers with bacterial suspension (10⁶ CFU/mL) for 30 minutes in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Gently rinse to remove loosely attached cells [8] [7].

Sample Preparation: Immobilize biofilm samples or coated substrates on gelatin-coated glass surfaces. Gelatin coating provides optimal attachment while maintaining bacterial viability [8].

Validation: Verify bacterial attachment and viability through fluorescence microscopy with live/dead staining if necessary [7].

Large-Area AFM Imaging of Biofilm Organization

Objective: To characterize spatial organization and structural features of biofilms across multiple scales. Materials:

- Automated large-area AFM system with motorized stage

- Bacterial biofilms grown on relevant substrates

- Appropriate liquid cell for physiological imaging conditions

Procedure:

- Sample Mounting: Secure the biofilm substrate to the AFM sample stage using compatible mounting tools.

Liquid Environment Setup: If imaging under physiological conditions, assemble liquid cell and inject appropriate buffer solution to fully immerse the sample.

Automated Imaging Setup: Program the automated large-area AFM to capture multiple adjacent scan regions with minimal overlap (typically 5-10%) [4].

Image Acquisition: Perform tapping-mode AFM in liquid to minimize sample disturbance. Use the following parameters:

Data Processing: Apply machine learning-based image stitching algorithms to create seamless large-area reconstructions. Implement automated cell detection and classification to analyze spatial distribution and cellular morphology [1] [4].

Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy for Adhesion Quantification

Objective: To measure adhesion forces between individual bacterial cells and substrates. Materials:

- AFM with single-cell force spectroscopy capability

- Functionalized cantilevers with immobilized single cells

- Target substrates of interest

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Calibrate the cantilever spring constant using thermal tuning or reference cantilever methods.

Force Curve Acquisition:

- Approach the cell-functionalized cantilever toward the substrate at 0.5-1 μm/s

- Maintain contact for 0-10 seconds to allow bond formation

- Retract the cantilever at the same speed while recording deflection [7]

Data Collection: Collect a minimum of 100-200 force curves across different sample locations to account for heterogeneity.

Data Analysis:

- Identify adhesion force (Fmax) from the maximum rupture force during retraction

- Calculate adhesion energy from the area under the retraction curve

- Detect specific binding events through characteristic "jumps" in the force curve [5]

Statistical Analysis: Perform population-level analysis to identify subpopulations with distinct adhesive properties and calculate heterogeneity indices [8].

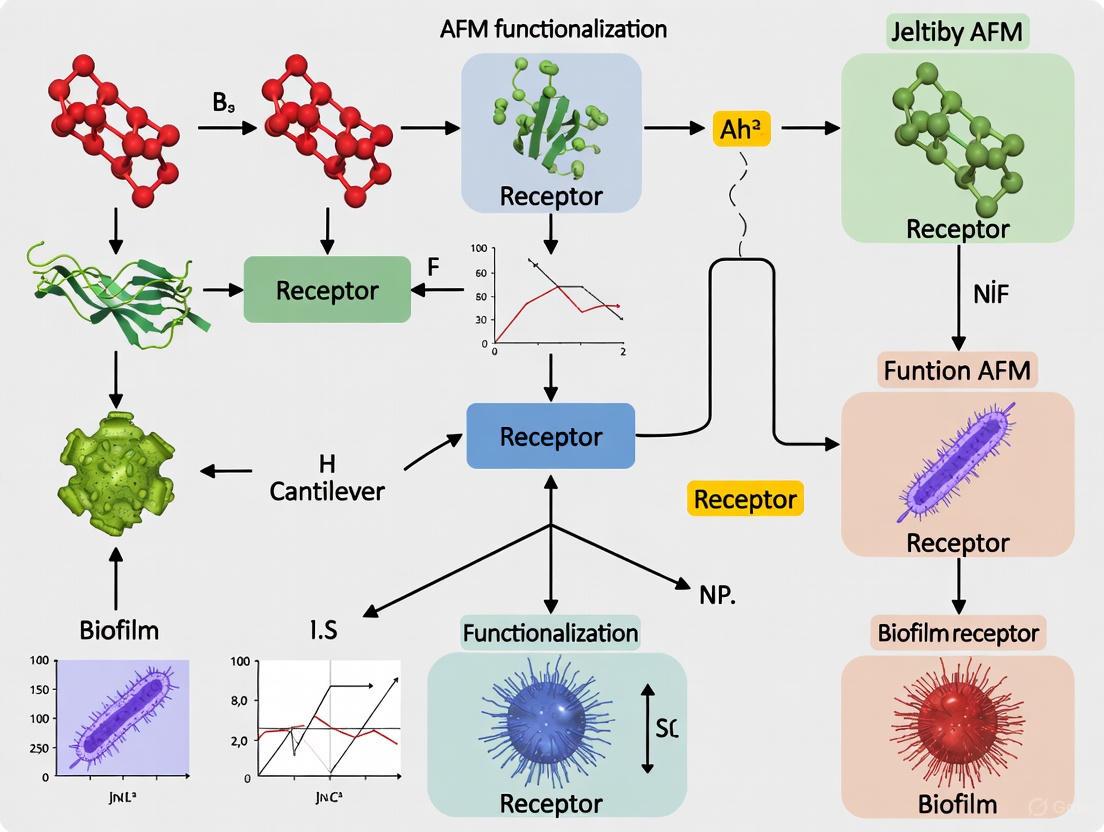

SCFS Experimental Workflow: Diagram illustrating the key steps in single-cell force spectroscopy experiments, from cantilever functionalization to data analysis.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Correlative Imaging and Multi-modal Approaches

The integration of AFM with complementary microscopy techniques represents a powerful trend in biofilm research. Correlative systems that combine AFM with fluorescence microscopy and spectral imaging enable researchers to link nanoscale topographical information with chemical composition and molecular specificity [9]. As noted in recent commentary, "By integrating AFM with fluorescence microscopy and spectral imaging, researchers can uncover multidimensional insights into both biological and material systems" [9]. This holistic approach allows for the identification of specific molecular components within the complex architecture of biofilms while simultaneously characterizing their mechanical properties.

AI and Machine Learning Integration

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are transforming AFM-based biofilm analysis in four key areas: sample region selection, scanning process optimization, data analysis, and virtual AFM simulation [4]. Machine learning algorithms have enabled automated analysis of large-area AFM datasets, allowing researchers to "extract meaningful quantitative data from these massive datasets" [1]. For instance, one recent study "automatically analyzed more than 19,000 individual cells to generate detailed maps of cell properties across extensive surface areas" [1], a task that would be prohibitively time-consuming through manual analysis. The growing adoption of AI in AFM is expected to continue accelerating, with the development of open-source tools and data sharing initiatives further advancing the field [9].

High-Throughput Screening for Anti-biofilm Strategies

AFM-based mechanical and adhesion measurements are increasingly being applied to screen surface modifications and antimicrobial treatments for their ability to disrupt biofilm formation. Research on engineered surfaces with nanoscale ridges has revealed that "specific patterns could disrupt normal biofilm formation, offering potential strategies for designing antifouling surfaces that resist bacterial buildup" [1]. Similarly, studies on titanium implant surfaces have demonstrated that "treatment with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and laser-induced periodic surface structure (LIPSS) increased the roughness and hydrophilicity of the Ti substrate and consequently reduced the bacterial adhesion strength" [7]. These applications highlight the translational potential of AFM-guided biofilm research for developing practical solutions in medical device and implant design.

AFM Biofilm Analysis Ecosystem: Diagram showing the relationship between core AFM capabilities, advanced applications, and future development directions in biofilm research.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AFM-Based Biofilm Adhesion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride Cantilevers | Force sensing and imaging | Spring constant 0.01-0.5 N/m for biological samples; colloidal probes for whole-cell measurements | [8] [5] |

| Poly-L-lysine (PLL) | Sample immobilization | 0.1% w/v solution for electrostatic immobilization of cells on substrates | [8] [7] |

| Polydopamine | Bio-inspired adhesion | Biocompatible coating for improved cell attachment to cantilevers | [5] [7] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Chemical fixation | 2.5% solution for structural preservation; may affect mechanical properties | [5] |

| Gelatin-coated Surfaces | Sample substrate | Provides optimal attachment while maintaining bacterial viability for imaging | [8] |

| PFOTS-treated Glass | Hydrophobic substrate | Used to study bacterial attachment mechanisms on low-energy surfaces | [4] |

| EDTA Solution | LPS removal agent | 100 mM, pH 8.0 for selective removal of lipopolysaccharides from Gram-negative bacteria | [8] |

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has evolved from a topographical imaging tool into a versatile platform for investigating specific molecular interactions in biological systems. By functionalizing AFM cantilevers with specific molecules, researchers can probe receptor-ligand dynamics with unprecedented precision, directly measuring binding forces and interaction kinetics at the single-molecule level. This capability is particularly valuable for studying biofilm-forming microorganisms, where understanding the nanomechanical properties and adhesive forces of resistant strains is crucial for addressing the global challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Resistant bacterial strains exhibit distinct surface characteristics, including increased cell wall rigidity and enhanced adhesiveness, which enable them to form densely packed biofilms—a key factor in their pathogenicity and treatment resistance [5].

The fundamental principle underlying functionalized AFM probes is the conversion of molecular recognition events into measurable mechanical signals. When a cantilever functionalized with a specific ligand interacts with its complementary receptor on a sample surface, the binding event causes cantilever deflection that can be quantified through force-distance curves. This approach, known as single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS), provides quantitative data on binding forces, adhesion energies, and interaction dynamics under physiologically relevant conditions, including liquid environments where biological processes naturally occur [2] [5].

Principles of Probe Functionalization and Force Spectroscopy

Cantilever Functionalization Strategies

The specificity of AFM-based receptor-ligand studies depends entirely on the proper functionalization of cantilever tips. Effective functionalization requires careful consideration of surface chemistry, orientation control, and maintaining biological activity. Common strategies include:

- Chemical Modification: Silanization with aminosilanes or thiol-based chemistry on gold-coated tips provides reactive groups for subsequent biomolecule attachment. This approach creates a stable foundation for ligand immobilization while minimizing nonspecific interactions [5].

- Biomolecule Attachment: Proteins, peptides, or other ligands can be covalently linked to activated cantilever surfaces using crosslinkers like glutaraldehyde or through spontaneously forming polydopamine adhesive layers. The biocompatible polymer polydopamine has proven particularly effective for immobilizing biomolecules while preserving their functionality [5].

- Orientation Control: For protein-based ligands, site-specific conjugation methods help ensure proper orientation toward target receptors, maximizing binding efficiency and data quality. This is especially important for studying high-affinity interactions where orientation affects accessibility.

Successful functionalization must balance ligand density to enable detectable binding signals while avoiding overcrowding that could cause steric hindrance or multivalent interactions that complicate data interpretation at the single-molecule level.

Force-Distance Curve Analysis

The primary measurement in functionalized AFM studies is the force-distance curve, which records the interaction forces between the functionalized tip and sample surface as they approach, contact, and separate. Key parameters extracted from these curves include:

- Adhesion Force: The maximum force required to separate the tip from the sample, corresponding to the strength of receptor-ligand bonds.

- Unbinding Work: The total work done during detachment, calculated as the area under the retraction curve.

- Interaction Specificity: Demonstrated through blocking experiments where free ligand in solution competitively inhibits adhesion events.

Advanced SMFS techniques can probe the mechanical properties of individual molecular complexes, revealing "jumps" in the retraction curve corresponding to the sequential breaking of individual bonds, and "tethers" representing complete detachment events [5]. These detailed mechanical signatures provide insights into the energy landscapes and structural organization of molecular interactions.

Application Notes: Investigating Biofilm Receptors

Technical Requirements for Biofilm Studies

Studying biofilm systems presents unique technical challenges that require specific adaptations of AFM methodology:

- Liquid Environment Compatibility: Biofilms must be maintained in hydrated, physiologically relevant conditions throughout imaging and force measurements. AFM instruments equipped with fluid cells enable operation in buffer solutions that preserve biofilm viability and native structure [2] [5].

- Controlled Loading Forces: To prevent damage to delicate biological samples, cantilevers with low spring constants (typically 0.01-0.5 N/m) are essential for maintaining loading forces below 1 nN, minimizing sample deformation while obtaining reliable measurements [5] [10].

- Specialized Cantilevers: Silicon or silicon nitride cantilevers with sharp tips (radius < 50 nm) provide the necessary spatial resolution for discriminating individual receptors on cell surfaces. Reflective gold coatings enable precise optical detection of cantilever deflection [2].

Representative Experimental Data

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from recent AFM studies investigating microbial systems using functionalized probes:

Table 1: Representative AFM Force Spectroscopy Data from Microbial Studies

| Study System | Functionalization | Measured Adhesion Force | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Fibrinogen ligand | Catch-bond behavior with force-dependent strengthening | 150-300 pN single-bond forces; 1.5 nN for multivalent interactions | [5] |

| Bacterial scaffoldin cohesin modules | Cohesin-dockerin interaction | ~300 pN unfolding forces | Calcium stabilization dramatically increases mechanical stability | [10] |

| Polymer dot substrate | Unmodified conductive tip | 180-330 mV surface potential differences | Sideband KPFM provides superior electrical resolution for heterogeneous samples | [11] |

The data demonstrate the force range typically encountered in biological systems, from single receptor-ligand bonds measuring hundreds of piconewtons to multivalent interactions reaching several nanonewtons. These measurements provide fundamental insights into the mechanical stability of molecular complexes and their response to physical stress.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cantilever Functionalization for Receptor Studies

This protocol describes the functionalization of AFM cantilevers with specific ligands for studying receptor-binding interactions, particularly applicable to biofilm research.

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for Cantilever Functionalization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride Cantilevers | Force sensing platform | Spring constant: 0.01-0.5 N/m; Tip radius: < 50 nm | [5] [10] |

| Ethanol (70-100%) | Surface cleaning and hydration | Molecular biology grade | [5] |

| Polydopamine Solution | Bio-adhesive coating | 2 mg/mL dopamine hydrochloride in Tris buffer (pH 8.5) | [5] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Washing and dilution | 1X concentration, pH 7.4 | [5] |

| Target Ligand/Protein | Recognition element | >90% purity, concentration specific to application | [12] [5] |

| Glutaraldehyde (optional) | Crosslinking | 2.5% solution in PBS for amine-amine coupling | [5] |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Cantilever Cleaning: Place cantilevers in a glass container and immerse in 70% ethanol for 15 minutes. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

Polydopamine Coating: Incubate cantilevers in freshly prepared polydopamine solution (2 mg/mL in 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.5) for 45-60 minutes with gentle agitation. This forms a uniform adhesive layer for ligand attachment.

Ligand Immobilization: Transfer cantilevers to a solution containing the target ligand (typically 50-100 µg/mL in PBS). Incubate for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C for optimal surface density.

Quenching and Storage: Rinse functionalized cantilevers with PBS to remove unbound ligand. Block any remaining reactive sites with 1 M ethanolamine (for glutaraldehyde-activated surfaces) or 1% bovine serum albumin. Store in PBS at 4°C until use.

Quality Control: Before biological experiments, test functionalized cantilevers against control surfaces with known ligand density to verify binding activity and estimate functionalization density.

Protocol 2: Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy on Biofilms

This protocol describes the measurement of specific receptor-ligand interactions on biofilm surfaces using functionalized AFM cantilevers.

Sample Preparation:

Grow biofilms on appropriate substrates (e.g., glass coverslips, medical device materials) using standard microbiological culture conditions relevant to the research question.

Carefully transfer the biofilm substrate to the AFM fluid cell without allowing dehydration. Maintain in appropriate buffer solution throughout measurement.

Force Spectroscopy Measurements:

Mount the functionalized cantilever in the AFM holder and approach the biofilm surface slowly to minimize initial impact force.

Program the AFM to collect force-distance curves at multiple locations across the biofilm surface, with approach-retract cycles of 0.5-1 Hz and maximum loading force below 500 pN to avoid sample damage.

Collect a minimum of 1000 force curves per experimental condition to ensure statistical significance. Include control measurements using non-functionalized cantilevers to account for nonspecific adhesion.

For binding specificity validation, repeat measurements after adding soluble ligand (100-500 × KD) to the buffer solution to competitively inhibit binding.

Data Analysis:

Process force curves using appropriate software to extract adhesion force, rupture length, and unbinding work parameters.

Construct adhesion force histograms to identify quantized force peaks corresponding to single-molecule unbinding events.

Calculate binding probability by dividing the number of curves showing adhesion events by the total number of curves collected.

Advanced Functionalized Probe Methodologies

Simultaneous Topographical and Electrical Characterization

Advanced AFM modes enable correlative analysis of surface properties alongside molecular recognition events. Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) has emerged as a powerful technique for mapping surface potential distributions while performing topographical imaging, providing complementary electrical information about biological samples:

- Sideband KPFM: This advanced implementation measures the electrostatic force gradient rather than direct electrostatic force, providing enhanced spatial resolution and potential sensitivity compared to traditional amplitude modulation KPFM. Studies demonstrate that Sideband KPFM achieves approximately double the surface potential contrast on layered samples like highly-ordered pyrolytic graphite (70 mV vs. 35 mV for AM-KPFM) and clearer discrimination of nanoscale features [11].

- Application to Biofilms: KPFM can detect variations in surface charge distribution across heterogeneous biofilm structures, potentially correlating with regions of different metabolic activity or composition. When combined with functionalized probes, this enables simultaneous mapping of receptor distribution and electrochemical properties.

High-Speed AFM for Dynamic Process Visualization

Conventional AFM imaging speed limitations have historically restricted observation of dynamic biological processes. Recent developments in high-speed AFM (HS-AFM) have overcome this barrier:

- Technical Advances: HS-AFM systems utilize small cantilevers with high resonance frequencies, optimized controllers, and fast scanners to achieve temporal resolution sufficient for visualizing molecular dynamics in real time [2].

- Biological Applications: This capability enables direct observation of dynamic processes such as viral attachment to host cell receptors, protein conformational changes, and receptor diffusion in native membranes. When integrated with functionalized probes, HS-AFM can capture the spatial and temporal dynamics of receptor-ligand interactions under physiological conditions [2].

Technical Specifications and Research Tools

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AFM Biofilm Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cantilever Materials | Silicon nitride (Si₃N₄), Silicon (Si) | Base material providing mechanical properties for force sensing | [2] [5] |

| Surface Coatings | Gold (Au), Polydopamine, Poly-L-lysine | Enable biomolecule attachment and reduce nonspecific binding | [5] |

| Crosslinkers | Glutaraldehyde, BS³, SMCC | Covalent immobilization of ligands to cantilever surface | [5] |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Ethanolamine | Passivate unused reactive sites to minimize background adhesion | [5] |

| Imaging Buffers | PBS, HEPES, Tris-based buffers | Maintain physiological conditions during force measurements | [2] [5] |

| Specificity Controls | Soluble ligands, Receptor blockers | Verify binding specificity through competitive inhibition | [12] [5] |

Instrumentation and Measurement Parameters

Successful implementation of functionalized AFM studies requires careful optimization of instrumental parameters:

- Force Calibration: Accurate quantification of binding forces requires precise calibration of cantilever spring constants. Recent advances include traceable calibration methods using micro-electro-mechanical system (MEMS) actuators that provide SI-traceable force measurements with uncertainties below 8% [10].

- Environmental Control: Maintaining temperature stability and physiological conditions throughout measurements is essential for preserving biological activity. Advanced fluid cells enable buffer exchange during experiments for inhibitor addition or environmental modification.

- Resolution Considerations: The spatial resolution of binding site localization is primarily limited by tip radius (typically 5-50 nm for commercial tips) and functionalization layer thickness, while force resolution is determined by thermal noise levels in the cantilever (typically 10-50 pN under physiological conditions).

Functionalized AFM probes have transformed atomic force microscopy from a topographical imaging technique into a powerful platform for quantifying specific molecular interactions in biological systems. The methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with robust protocols for investigating receptor-ligand interactions in complex biofilm systems, with particular relevance to understanding antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. As technical capabilities continue to advance, including improvements in speed resolution, force sensitivity, and multimodal integration, functionalized AFM is poised to deliver increasingly profound insights into the nanoscale world of molecular recognition events. The quantitative data generated through these approaches not only furthers fundamental understanding of microbial systems but also provides critical information for developing novel therapeutic strategies against treatment-resistant pathogens.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has revolutionized our ability to study biological systems at the nanoscale, providing unprecedented insight into the structural and mechanical properties of bacterial biofilms. This application note details how functionalized AFM cantilevers can be employed to investigate the key molecular interactions that govern biofilm development, focusing specifically on receptors involved in quorum sensing (QS) and components of the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS). The formation of biofilms is a complex, hierarchical process wherein bacterial communities coordinate group behaviors through chemical communication systems, primarily QS, and become encased in a protective EPS matrix. Understanding the specific receptor-ligand interactions that drive these processes is crucial for developing novel anti-biofilm strategies. AFM-based force spectroscopy, enabled by advanced cantilever functionalization techniques, provides a powerful platform for quantifying these interactions with high sensitivity and under physiologically relevant conditions. This protocol outlines the methodologies for cantilever modification, sample preparation, and force measurement to study biofilm-related receptors and ligands, framing these techniques within the broader context of AFM cantilever functionalization for molecular recognition studies.

Key Receptors and Ligands in Biofilm Formation

Biofilm formation is regulated by a complex network of receptor-ligand interactions. The table below summarizes the primary receptors and their cognate ligands involved in bacterial quorum sensing and biofilm matrix assembly.

Table 1: Key Receptors and Ligands in Bacterial Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Formation

| Receptor | Cognate Ligand(s) | Bacterial Species Examples | Primary Function in Biofilm | Reported Binding Affinity (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LuxR-type (LasR) | N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine Lactone (AHL) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa [13] [14] | Activates virulence factor and EPS gene transcription [13] | ≥ -4.5 [13] |

| AgrC | Autoinducing Peptide (AIP) | Staphylococcus aureus [13] | Two-component sensor kinase regulating virulence and biofilm dispersal [13] | ≥ -4.5 [13] |

| LuxP | Autoinducer-2 (AI-2) | Vibrio harveyi [13] | Interspecies communication; regulates biofilm formation [13] | Complex stable [13] |

| LuxN | Autoinducer-1 (AI-1) [HAI-1] | Vibrio harveyi [13] | Intraspecies communication; biofilm regulation [13] | ≥ -4.5 [13] |

| SdiA | AHLs | Escherichia coli [13] | Detects AIs from other species; influences biofilm formation [13] | ≥ -4.5 [13] |

| PlcR | PapR7 heptapeptide | Bacillus cereus [13] | Master virulence regulator activated by signaling peptide [13] | ≥ -4.5 [13] |

| RRNPP-type | Autoinducing Peptides (AIPs) | Gram-positive bacteria [13] | Regulate virulence and biofilm-related genes [13] | Information Missing |

| EPS Components | Various (Proteins, Polysaccharides, eDNA) | Various (e.g., Pantoea sp.) [4] | Structural integrity, adhesion, cohesion, and protection [15] [4] | Information Missing |

The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) is a critical ligand-rich component of the biofilm matrix, providing structural integrity and functionality. The EPS consists of a complex mixture of polymers, including polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (eDNA) [15]. While not classic receptors, various bacterial surface proteins and structures (e.g., flagella, pili) interact with EPS components during the attachment and maturation phases of biofilm development [4]. For instance, AFM studies on Pantoea sp. YR343 have visualized flagellar structures that interact with surfaces and other cells, facilitating the assembly of distinct honeycomb-like patterns in early biofilms [4].

Experimental Protocols

AFM Cantilever Functionalization for Molecular Recognition Studies

Principle: This protocol describes a robust method for functionalizing silicon nitride AFM cantilevers to immobilize biomolecules of interest via a stable, covalently bound Si-C interface. This technique minimizes the formation of polymeric aggregates and susceptibility to hydrolysis associated with traditional silane chemistry, creating a uniform substrate for molecular recognition force spectroscopy [16].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cantilever Functionalization

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride AFM Cantilevers | Base substrate for functionalization. | Commercially available sharp tips (e.g., MSNL-10 from Bruker) or tip-less cantilevers (e.g., NPO-10 for bead attachment) can be used [15]. |

| Hydrogen-termination Solution | Creates a reactive hydrogen-passivated surface on Si₃N₄. | Typically a dilute HF solution or HF vapor treatment. |

| Protected α-amino-ω-alkene | Forms a highly oriented monolayer via hydrosilylation; provides terminal amine for bioconjugation. | Example: N-α-Boc-1,8-diaminooctane or similar [16]. |

| Biomolecule of Interest | The ligand or receptor to be studied (e.g., lactose, AHL, EPS component). | To be conjugated to the functionalized surface. |

| UV Curing Resin | For attaching microspheres to tipless cantilevers if creating spherical probes. | e.g., Loctite UV resin [15]. |

| Borosilicate Microspheres | Creates a defined spherical tip geometry for improved contact and force measurement. | e.g., 10 µm spheres from Whitehouse Scientific [15]. |

Procedure:

- Cantilever Cleaning and Hydrogen Termination: Clean silicon nitride AFM cantilevers in a piranha solution (3:1 mixture of concentrated H₂SO₄ and 30% H₂O₂) for 30 minutes. Caution: Piranha solution is highly corrosive and must be handled with extreme care. Rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water and ethanol. Subsequently, treat the cantilevers with a 2% HF solution to create a hydrogen-terminated silicon nitride surface. Rinse again with copious amounts of ethanol and dry under a stream of nitrogen gas [16].

- Formation of Monolayer via Hydrosilylation: Immerse the hydrogen-terminated cantilevers in a degassed, anhydrous solution of the protected α-amino-ω-alkene (e.g., 10 mM in mesitylene). React for 12-16 hours at a controlled temperature (e.g., 80°C) under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon) to facilitate the hydrosilylation reaction, forming a stable Si-C bond and a highly oriented monolayer [16].

- Deprotection: Remove the protecting group (e.g., Boc group) by treating the functionalized cantilevers with a mild acid, such as a 50% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) solution in dichloromethane, for 30 minutes. This step reveals a free amine group on the surface for subsequent bioconjugation [16].

- Biomolecule Immobilization: Conjugate the biomolecule of interest (e.g., a QS ligand like lactose or a purified EPS component) to the free amine on the monolayer using standard crosslinking chemistry. A common approach is to use a heterobifunctional crosslinker like SMCC, which reacts with surface amines via its NHS ester and with thiols on the biomolecule via its maleimide group. If the biomolecule lacks a native thiol, it can be engineered or modified to introduce one. Incubate the cantilevers in the biomolecule solution (typically 0.1-1 mg/mL in a suitable buffer) for 1-2 hours [16].

- Optional: Spherical Probe Creation (Alternative Method): For studies requiring a larger, defined contact area, tipless cantilevers (e.g., NPO-10) can be functionalized with borosilicate microspheres. Attach a 10 µm microsphere to the cantilever using a UV-curing resin. Cure the resin under UV light (λ = 400 nm) for 5 minutes. The glass sphere can then be chemically functionalized using silane chemistry (e.g., (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane, APTES) followed by the same bioconjugation steps described above [15].

Sample Preparation: Biofilm and Receptor Immobilization

Principle: To study receptor-ligand interactions, the counterpart molecule (e.g., a QS receptor protein) must be immobilized on a solid substrate while maintaining its native conformation and activity.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Use clean, flat substrates such as glass coverslips, silica wafers, or hydroxyapatite (HAP) discs. For biofilm studies, HAP is often used to mimic mineralized surfaces like teeth [15].

- Model Biofilm Formation (for EPS studies): Grow microcosm biofilms on the substrate. For example, inoculate HAP discs with pooled human saliva and incubate in nutrient-rich (e.g., 5% w/v sucrose) or nutrient-poor (e.g., 0.1% w/v sucrose) media at 37°C in 5% CO₂ for 3-5 days, replacing the growth media at 24-hour intervals [15].

- Protein Immobilization (for QS studies): Immobilize purified QS receptor proteins (e.g., LasR, LuxP) or whole bacterial cells onto the substrate. For proteins, use a similar amine-thiol crosslinking strategy on an APTES-functionalized surface. For bacterial cells, physical entrapment in a porous membrane or chemical fixation with poly-L-lysine can be used [17].

AFM Force Spectroscopy and Data Analysis

Principle: Molecular recognition forces are measured by monitoring the deflection of the functionalized cantilever as it approaches and retracts from the target surface.

Procedure:

- Instrument Setup: Perform measurements in a suitable liquid buffer (e.g., PBS) under physiological conditions (e.g., 37°C) using a commercial AFM system (e.g., JPK Nanowizard).

- Force Curve Acquisition: Align the functionalized cantilever above the area of interest on the sample surface. Approach and retract the cantilever at a constant velocity (typically 0.5-1 µm/s), recording hundreds to thousands of force-distance curves at different locations.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the retraction curves to identify specific unbinding events, characterized by non-linear rupture peaks. The unbinding force is the magnitude of these rupture events. The binding probability is calculated as the percentage of curves showing specific adhesion events. For a more detailed analysis, the bond kinetics can be assessed by performing experiments at different loading rates [16] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Category | Item | Specific Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Consumables | Silicon Nitride Cantilevers (sharp & tipless) | The core sensor for force measurement and imaging. |

| Borosilicate Microspheres (10 µm) | Creates a spherical probe for consistent surface contact [15]. | |

| Chemistry Reagents | Protected α-amino-ω-alkene | Forms a stable, oriented monolayer on Si₃N₄ via hydrosilylation [16]. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | An alternative for introducing amine groups on glass/silica surfaces. | |

| Heterobifunctional Crosslinker (e.g., SMCC) | Links surface amines to thiolated biomolecules. | |

| Biology Reagents | Biomolecules of Interest (Ligands/Receptors) | The key interactors being studied (e.g., AHLs, AIPs, EPS proteins). |

| Purified QS Receptor Proteins | Immobilized on substrate to study interaction with tip-bound ligands. | |

| Growth Media (e.g., BHI with Sucrose) | For cultivating robust in-vitro biofilms on substrates [15]. | |

| Lab Equipment | Atomic Force Microscope | Platform for conducting force spectroscopy and imaging. |

| UV Curing Chamber | For curing resin during spherical probe attachment [15]. |

Visualizing Pathways and Workflows

Quorum Sensing Signaling Pathways

AFM Force Spectroscopy Workflow

The integration of advanced AFM cantilever functionalization with force spectroscopy provides a powerful, quantitative method for probing the molecular interactions that underpin biofilm formation. The protocol outlined herein, centered on creating a stable Si-C bonded monolayer, enables researchers to reliably immobilize everything from small QS molecules like AHLs to complex EPS components. This approach allows for the direct measurement of unbinding forces and kinetics between key receptors and ligands, such as LasR-AHL or flagella-EPS interactions, under native conditions. The ability to map these interactions quantitatively, as summarized in the provided tables, offers deep insights into the fundamental mechanisms of biofilm assembly and stability. Furthermore, the experimental workflow and visualization tools detailed in this application note equip researchers with a standardized methodology to advance the study of biofilm recalcitrance and contribute to the development of novel anti-biofilm therapeutic agents.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has established itself as a powerful, multifunctional platform for the structural and functional characterization of biological systems at the nanoscale [18]. Its unique capability to operate in physiological liquid environments makes it particularly valuable for studying soft, dynamic biological samples, including microbial biofilms [5] [17]. A critical advancement in AFM technology is functionalization chemistry, which enables the modification of AFM cantilevers and tips with specific biomolecules or chemical groups, transforming the stylus into a nanoscopic analytical laboratory [18]. This functionalization is fundamental for studies targeting biofilm receptors, as it allows researchers to move beyond topographical imaging to directly probe specific interaction forces, receptor distributions, and binding kinetics on biofilm-forming microbial cells [5] [17]. Techniques such as single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) and affinity AFM (AF-AFM) rely on robust and reproducible cantilever functionalization to investigate the nanomechanical properties and receptor-ligand interactions that underpin biofilm formation and antimicrobial resistance [5] [19]. This document provides a detailed overview of the core chemistries—silane chemistry, cross-linkers, and bioconjugation—that enable these sophisticated experiments, framed within the context of biofilm receptor studies.

Core Functionalization Chemistries

The process of functionalizing an AFM cantilever for specific biofilm receptor studies typically involves a multi-step approach: surface cleaning and activation, application of a linker layer (often via silane chemistry), and finally, the immobilization of the biomolecule of interest (bioconjugation), frequently mediated by a cross-linker.

Silane Chemistry

Silane chemistry is one of the most prevalent methods for creating a functional interface on AFM cantilevers, which are commonly made of silicon (Si) or silicon nitride (Si₃N₄) [20]. Organosilane molecules act as a molecular bridge, covalently linking the inorganic cantilever surface to organic molecules or biomolecules.

The process begins with surface hydroxylation, where the native oxide layer on the cantilever surface is enriched with reactive hydroxyl (-OH) groups. These groups then undergo a condensation reaction with the alkoxy groups of the silane coupling agent [19]. A key challenge with conventional immersion silanization is ensuring reproducibility and avoiding the formation of polymeric aggregates, which can lead to inhomogeneous layers [16].

Table 1: Common Organosilanes for AFM Cantilever Functionalization

| Silane Name | Reactive Group | Functional Group After Deposition | Key Application in Biofilm Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| APTES [(3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane] | Triethoxy | Primary Amine (-NH₂) | Provides amino groups for subsequent cross-linking to carbohydrates, proteins, or antibodies targeting biofilm receptors [19]. |

| APDMES [(3-Aminopropyl)dimethylethoxysilane] | Monoethoxy | Primary Amine (-NH₂) | Creates a thinner, more controlled monolayer due to its single reactive site, reducing polymerization [16]. |

| PEG-silane | Triethoxy or Monoethoxy | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Used to create non-fouling, protein-resistant backgrounds or as a flexible, long-chain spacer to isolate receptor-ligand binding events [20]. |

To overcome the limitations of traditional methods, advanced techniques like Activated Vapour Silanization (AVS) have been developed. AVS provides a robust and reliable method for depositing functional thin films, even on complex geometries like AFM tips [19]. In one documented protocol, a 10-minute AVS deposition of APTES resulted in a thin film with an estimated thickness of approximately 70 nm, successfully introducing amine functional groups to the cantilever surface as confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [19].

An alternative to silane chemistry that forms an even more stable interface is hydrosilylation. This method forms a direct, hydrolysis-resistant Si-C bond between hydrogen-terminated silicon nitride and terminal alkenes. This approach facilitates the creation of stable, highly oriented monolayers that are uniform in epitope density and substrate orientation, which is highly desirable for quantitative force spectroscopy studies [16].

Cross-linkers

Once a functional layer (e.g., an amine-terminated silane) is established on the cantilever, cross-linkers are used to covalently attach the biomolecular probes (e.g., antibodies, lectins, or other receptor ligands). Cross-linkers are bifunctional or multifunctional reagents that react with specific chemical groups.

Table 2: Common Cross-linkers for Bioconjugation on AFM Cantilevers

| Cross-linker | Reactive Groups | Spacer Arm Length | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde | Aldehyde (-CHO) to Amine (-NH₂) | ~6.5 Å | Connects amine-functionalized cantilevers to amine groups on proteins. Often requires a reduction step (e.g., with sodium cyanoborohydride) to stabilize the Schiff base intermediate [20]. |

| Sulfo-SMCC [(N-ε-Maleimidocaproyloxy)succinimide ester] | NHS-ester to Maleimide | ~8.3 Å | A heterobifunctional cross-linker. The NHS-ester reacts with amine groups on the functionalized cantilever, while the maleimide group reacts with sulfhydryl groups (-SH) on the target biomolecule, enabling site-specific conjugation [20]. |

| EDC/NHS [1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide / N-Hydroxysuccinimide] | Carboxylate (-COOH) to Amine (-NH₂) | Zero-length | Mediates "zero-length" cross-linking by activating carboxyl groups to form amide bonds with primary amines. Commonly used to conjugate proteins or peptides to functionalized surfaces [19]. |

The choice of cross-linker and the use of a long-chain spacer (like PEG) are crucial. A long, flexible spacer helps to isolate the specific biomolecular forces being probed by minimizing unwanted, non-specific interactions between the AFM tip and the sample surface [20].

Bioconjugation

Bioconjugation is the final step, where the specific biorecognition element is immobilized onto the cross-linker-modified cantilever surface. The goal is to present the biomolecule in a functional orientation and with sufficient density to probe the target receptors on biofilms.

- Antibodies: These can be attached via amine groups (using EDC/NHS or glutaraldehyde) or via engineered sulfhydryl groups (using Sulfo-SMCC) for a more controlled orientation. Antibodies are used to map specific receptor proteins, such as quorum-sensing receptors like LasR on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms [19] [21].

- Lectin Proteins: Lectins like Galectin-3 can be immobilized to study interactions with carbohydrate residues present in the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) of biofilms [16].

- Whole Microbial Cells: For single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS), a single microbial cell can be attached to a tipless cantilever using a thin layer of a biocompatible adhesive like polydopamine or epoxy glue. This allows measurement of the adhesion forces between a probe cell and a biofilm surface [5] [17].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Activated Vapour Silanization (AVS) with APTES

This protocol, adapted from Daza et al. (2019), details the functionalization of silicon nitride (Si₃N₄) cantilevers with amine groups using AVS [19].

Principle: Vapour-phase deposition of APTES under controlled conditions ensures a uniform and reproducible amine-functionalized layer.

Materials:

- Silicon nitride AFM cantilevers

- Acetone (≥99.5%)

- Isopropanol (≥99.5%)

- (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES, ≥98%)

- Nitrogen gas stream

- AVS deposition chamber

Procedure:

- Cleaning: Gently rinse the AFM chips in a stream of acetone for 2 minutes, followed by a 2-minute rinse in a stream of isopropanol. Do not use ultrasonic baths, as they can damage the delicate cantilevers.

- Drying: Dry the chips under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

- AVS Deposition: Place the cleaned cantilevers in the AVS chamber. Introduce APTES vapour and allow the deposition to proceed for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Post-processing: Following deposition, cure the functionalized cantilevers at 70°C for 10 minutes to consolidate the silane layer.

- Validation: The success of functionalization can be verified by measuring the shift in the cantilever's resonance frequency to estimate film thickness (expected ~70 nm for 10 min deposition) and by XPS analysis to confirm the presence of surface amine groups [19].

Protocol 2: Hydrosilylation for Stable Monolayer Formation

This protocol, based on Kogler et al. (2012), describes a method to form a stable monolayer via Si-C bonding, suitable for single-molecule studies [16].

Principle: A protected α-amino-ω-alkene is grafted onto a hydrogen-terminated silicon nitride surface via hydrosilylation, creating a stable foundation for biomolecule attachment.

Materials:

- Silicon nitride AFM cantilevers

- Aqueous HF solution (e.g., 1%)

- Protected α-amino-ω-alkene (e.g., N-(9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl)-10-amino-dec-1-ene)

- Toluene (anhydrous)

- Schlenk line or glovebox for oxygen-free conditions

Procedure:

- Hydrogen Termination: Etch the native oxide layer on the cantilevers by immersing them in a 1% HF solution for 2 minutes to create a hydrogen-terminated silicon nitride (Si₃N₄-H) surface.

- Hydrosilylation Reaction: Transfer the cantilevers into an anhydrous toluene solution containing the protected α-amino-ω-alkene. Incubate at an elevated temperature (e.g., 60°C for 2-4 hours) under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon) to facilitate the hydrosilylation reaction.

- Washing: Thoroughly rinse the cantilevers with toluene and then ethanol to remove any physisorbed molecules.

- Deprotection: Remove the protecting group (e.g., Fmoc) using a solution of piperidine in DMF to reveal the primary amine group for subsequent bioconjugation.

- Bioconjugation: The amine-terminated monolayer can now be used with cross-linkers like EDC/NHS or glutaraldehyde to immobilize the desired biomolecule [16].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow integrating the core functionalization chemistries for preparing a biofunctionalized AFM cantilever.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for AFM Cantilever Functionalization

| Reagent / Material | Function | Specific Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride (Si₃N₄) Cantilevers | The substrate for functionalization; chosen for compatibility with biological liquids and functionalization chemistries. | OMLC-RC800PSA cantilevers (Olympus/Asylum Research) [19]. |

| APTES [(3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane] | An organosilane used to create an amine-terminated monolayer on the cantilever surface for further bioconjugation. | Used in Activated Vapour Silanization (AVS) to deposit a ~70 nm functional layer [19]. |

| Protected α-amino-ω-alkene | A molecule used in hydrosilylation to form a stable, highly oriented monolayer linked via a Si-C bond. | N-(9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl)-10-amino-dec-1-ene [16]. |

| EDC & NHS | A carbodiimide and ester cross-linking system used to activate carboxyl groups for conjugation with primary amines ("zero-length" cross-linker). | Conjugating amine-terminated cantilevers to carboxyl-containing biomolecules [19]. |

| Sulfo-SMCC | A heterobifunctional cross-linker that couples amine and sulfhydryl groups, allowing for controlled, site-specific attachment of biomolecules. | Conjugating an amine-functionalized cantilever to a thiolated antibody or protein [20]. |

| Polydopamine | A biocompatible polymer that forms a strong, adhesive coating on various surfaces, useful for immobilizing whole cells onto tipless cantilevers. | Preparing a bacterial probe for Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS) to measure cell-biofilm adhesion [5] [17]. |

Application in Biofilm Receptor Studies

Functionalized AFM cantilevers are instrumental in unraveling the mechanisms of biofilm formation and resistance. By coating tips with specific ligands, researchers can directly map and quantify the forces involved in the initial attachment of bacteria to surfaces, a critical first step in biofilm development [17]. Furthermore, affinity mapping can identify the distribution of key virulence regulators, such as the LasR quorum-sensing receptor in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a primary target for anti-biofilm drug development [21]. Force spectroscopy studies have revealed that antimicrobial-resistant bacterial strains often exhibit distinct nanomechanical properties, such as greater cell wall stiffness and increased adhesiveness, which are facilitated by altered surface receptor composition and can be directly probed with functionalized AFM [5]. The protocols outlined herein for silanization, cross-linking, and bioconjugation provide the foundational toolkit for preparing AFM cantilevers to conduct these critical investigations, ultimately contributing to the development of novel strategies to combat biofilm-associated infections.

Step-by-Step Protocols: Functionalization Techniques and Biofilm Force Spectroscopy

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool in biomedical and microbiological research, capable of not only high-resolution imaging but also precise force measurements under physiological conditions. Its application in studying biofilms—structured communities of microorganisms encased in an extracellular polymeric matrix—provides unique insights into their nanoscale mechanical properties and receptor-ligand interactions. The core sensing component of any AFM is its probe, consisting of a cantilever and tip, which directly interacts with the sample. Proper probe selection is therefore paramount, as it directly influences data quality, measurement accuracy, and ultimately, the biological conclusions drawn from the experiment. This application note provides a structured framework for selecting the optimal cantilever and tip geometry for AFM-based biofilm receptor studies, forming an essential component of a broader thesis on AFM cantilever functionalization.

AFM Cantilever Fundamentals

The AFM cantilever is a micro-fabricated beam that serves as a soft spring, deflecting in response to forces between the tip and the sample. Its mechanical properties dictate the sensitivity, stability, and suitability for specific experimental modes.

Key Cantilever Parameters

- Material: Cantilevers are most commonly made from silicon (Si) or silicon nitride (Si₃N₄). Silicon nitride cantilevers can be produced thinner and more flexible, while silicon often allows for sharper tips [22].

- Stiffness (Force Constant, k): This is a critical parameter that determines how much the cantilever will bend under a given force. "Soft" cantilevers (k < 0.1 N/m) are used for contact mode and force spectroscopy on delicate samples to minimize damage, while "stiff" cantilevers (k > 1 N/m) are preferred for dynamic modes in air [22].

- Resonance Frequency (f₀): The natural vibrational frequency of the cantilever. Cantilevers with high resonance frequencies are essential for tapping mode operations, as they allow gentle tapping and faster imaging speeds [22] [23].

- Geometry: The two primary shapes are rectangular (diving board) and triangular (V-shaped). Triangular levers are often considered more resistant to lateral torsional forces in contact mode [22].

Table 1: Fundamental Cantilever Parameters and Their Impact on Experiments

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Force Constant (k) | Stiffness of the cantilever spring | Softer cantilevers (low k) provide higher force sensitivity for imaging soft samples and adhesion measurements; stiffer cantilevers (high k) provide stability in dynamic modes and for indenting stiff materials. |

| Resonance Frequency (f₀) | Natural vibrational frequency of the lever | Higher frequencies enable faster scanning and are less susceptible to environmental vibrational noise. Essential for high-speed AFM and tapping mode. |

| Geometry | Shape of the cantilever (e.g., rectangular, triangular) | Affects the force constant and torsional rigidity. Triangular levers are less prone to twisting. |

| Material | Substance the cantilever is made from (e.g., Si, Si₃N₄) | Influences reflectivity (for laser alignment), electrical properties, and manufacturability of sharp tips. |

The Force-Distance Curve

The force-distance (F-d) curve is the fundamental measurement in force spectroscopy. In this mode, the cantilever is not scanned but lowered and raised at a single point on the sample surface [24]. The resulting curve contains a wealth of information:

- The approach curve reveals the sample's elastic properties and stiffness, often analyzed using models like the Hertz model to calculate Young's modulus [24] [25].

- The retraction curve provides quantitative data on adhesion forces between the tip and the sample, crucial for studying biofilm cohesion and receptor binding [24].

Cantilever and Tip Selection for Biofilm Studies

Biofilms are soft, viscoelastic, and often heterogenous, requiring specific probe characteristics to obtain meaningful data without damaging the sample.

Choosing the Cantilever

For most biofilm studies, including imaging and force spectroscopy, soft cantilevers are necessary to prevent sample deformation or disruption.

Table 2: Cantilever Selection Guide for Biofilm Applications

| Application | Recommended Force Constant (k) | Recommended Resonance Frequency (f₀) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topographical Imaging (Tapping Mode) | 0.1 - 5 N/m [17] | 10 - 150 kHz [22] | A medium stiffness provides stability while minimizing lateral forces that could displace weakly adhered cells. |

| Nanomechanical Mapping | 0.01 - 0.5 N/m [17] | 10 - 100 kHz | Low stiffness ensures high sensitivity to small variations in sample elasticity across the biofilm surface. |

| Single-Cell / Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy | 0.01 - 0.1 N/m [24] [17] | < 50 kHz | Very soft levers are essential to detect weak piconewton-scale interaction forces, such as ligand-receptor bonds. |

| Adhesion Force Measurements | 0.01 - 0.1 N/m [24] | < 50 kHz | Enables precise measurement of the "pull-off" force during retraction without overcoming the spring's own stiffness. |

Choosing the Tip Geometry

The tip geometry defines the contact area with the sample, directly influencing spatial resolution and the stress applied during indentation.

- Sharp Tips (Nominal radius: 2-20 nm): Ideal for high-resolution imaging to resolve topographical features of individual cells or matrix components [23]. However, the high local pressure can easily penetrate soft biofilm surfaces.

- Spherical Tips (Microbeads, radius: 0.5-5 µm): These tips are superior for quantitative force spectroscopy and adhesion studies [26]. The well-defined, larger contact area prevents sample piercing and allows for more straightforward application of contact mechanics models (e.g., Hertz model) to calculate elastic moduli and adhesive pressure [26]. This geometry is perfectly suited for probing the overall mechanical properties of a biofilm.

Probe Functionalization for Receptor Studies

A key technique in biofilm receptor studies is Affinity AFM (AF-AFM), which requires the tip to be functionalized with a specific biomolecule (e.g., an antibody, lectin, or adhesion protein) [19]. This creates a biosensor that can map and measure specific binding forces.

- Functionalization Methods: Common strategies involve silanization (e.g., using APTES to create an amine-terminated surface) or coating the tip with a thin gold layer to exploit gold-thiol chemistry for biomolecule attachment [19].

- Impact on Probe Choice: The functionalization process adds a layer to the tip, which can slightly blunt sharp tips and alter their mechanical properties. This makes spherical or otherwise robust tip geometries more suitable for functionalization. The choice of cantilever (typically a soft one for force sensitivity) remains the same.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Biofilm Adhesion Using a Functionalized Spherical Probe

This protocol describes a standardized method for quantifying the adhesion between a biofilm and a functionalized surface, adapted from microbead force spectroscopy (MBFS) [26].

1. Probe and Substrate Preparation:

- Cantilever: Select a tipless, soft cantilever (k ≈ 0.03 N/m) [26].

- Probe Functionalization: Attach a glass microbead (e.g., 50 µm diameter) to the end of the cantilever using a UV-curable epoxy.

- Biofilm Coating: Treat the bead-probe with a polycationic substance (e.g., poly-L-lysine). Incubate the probe in a concentrated bacterial suspension (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 2.0) for a defined period to allow a monolayer of cells to adhere, creating a "biofilm probe" [26].

- Substrate: Use a clean glass coverslip. For specific receptor studies, the substrate can be pre-coated with a protein of interest.

2. AFM Setup and Calibration:

- Mount the biofilm probe and substrate in the AFM liquid cell filled with an appropriate buffer.

- Calibrate the cantilever's sensitivity and spring constant using the thermal tune method [26].

3. Data Acquisition:

- Approach the biofilm probe to the substrate with a controlled velocity (e.g., 1 µm/s).

- Apply a defined loading force (e.g., 100-500 pN) and maintain contact for a set "dwell time" (e.g., 0.5-2 s) to allow bond formation.

- Retract the probe at the same velocity to obtain force-distance curves.

- Collect a minimum of 100-200 curves at different random locations on the substrate.

4. Data Analysis:

- Adhesive Pressure: Analyze the retraction curves. The adhesive pressure is calculated by dividing the average maximum pull-off force (F_ad) by the contact area (A) between the bead and substrate:

Adhesive Pressure = F_ad / A[26]. - Specific vs. Nonspecific Adhesion: To confirm the role of a specific receptor, repeat the experiment with a control where the receptor on the substrate is blocked with a free ligand or antibody.

Protocol 2: Nanomechanical Mapping of Biofilm Elasticity

This protocol outlines the procedure for creating a spatial map of the Young's modulus across a biofilm surface.

1. Sample and Probe Preparation:

- Biofilm Immobilization: Grow a biofilm on a suitable substrate (e.g., glass, polystyrene). Ensure robust immobilization, potentially using a porous membrane or a chemical adhesive like Cell-Tak to prevent detachment during scanning [24] [17].

- Probe Selection: Use a sharp, silicon nitride tip on a soft cantilever (k ≈ 0.1 N/m) to ensure both good spatial resolution and force sensitivity.

2. AFM Setup:

- Perform force calibration on a clean, hard area of the substrate (e.g., bare glass).

- Switch to the force mapping (or PeakForce QNM) mode.

3. Data Acquisition:

- Define a scan area (e.g., 10 x 10 µm) over the biofilm.

- Set parameters to obtain a high density of force-distance curves (e.g., 256 x 256 pixels) [17].

- The maximum loading force should be kept low (typically < 1 nN) to avoid plastic deformation of the sample.

4. Data Analysis:

- Young's Modulus Extraction: For each force curve, fit the contact portion of the approach curve with an appropriate contact mechanics model, most commonly the Hertz model [24] [17].

- The model relates applied force (F) to indentation (δ) and the sample's Young's modulus (E). For a pyramidal tip, the relationship is complex, but the software automatically processes all curves to generate a quantitative modulus map.

- Map Interpretation: Analyze the map to identify heterogeneities, correlating stiffer or softer regions with underlying cellular structures or matrix components.

Visualization of Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical decision-making process for probe selection and the experimental workflow for functionalization and measurement.

Diagram 1: A decision tree for selecting the appropriate AFM probe based on the primary experimental objective for biofilm studies.

Diagram 2: A standardized workflow for conducting quantitative biofilm adhesion measurements using a spherical probe (MBFS).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for AFM Biofilm Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Soft Contact Mode Cantilevers | High-resolution imaging of soft biological samples in liquid. | Silicon Nitride (Si₃N₄) cantilevers (e.g., MLCT-Bio from Bruker) with k ~ 0.01-0.1 N/m. |

| Sharp Tapping Mode Cantilevers | Topographical imaging with minimal lateral force. | Silicon cantilevers (e.g., RTESPA-300 from Bruker) with k ~ 20-80 N/m and f₀ ~ 200-400 kHz. |

| Tipless Cantilevers | Platform for attaching custom probes like microbeads for force spectroscopy. | Used as a base for creating spherical or functionalized probes [26]. |

| Functionalization Kit (Silanization) | Creating amine-terminated surfaces on Si/Si₃N₄ for biomolecule attachment. | Includes APTES (aminopropyltriethoxysilane) and solvents for activated vapour silanization (AVS) [19]. |

| Poly-L-Lysine Solution | Coating surfaces or probes to promote adhesion of bacterial cells. | A common method for immobilizing negatively charged bacterial cells on surfaces [24]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Stamps | Micro-patterned stamps for the gentle and effective mechanical immobilization of microbial cells. | Prevents cell damage and lateral drift during measurement [24] [17]. |

| Microbeads (Glass, Polystyrene) | Creating spherical probes for quantitative adhesion and nanomechanical testing. | Beads with a diameter of 1-50 µm can be glued to tipless cantilevers [26]. |

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) for Hydrophobic Functionalization

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) has emerged as a crucial technology in surface engineering, offering a precise technique for applying thin films with customized properties [27]. This Application Note provides a detailed protocol for utilizing CVD to impart stable hydrophobic functionalization onto Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) cantilevers. The primary application context is the study of biofilm receptor interactions, where controlled surface properties are essential for generating reliable, reproducible single-cell and single-molecule force spectroscopy data. CVD-functionalized cantilevers enable direct measurement of hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions in biological systems, which are fundamental to interpreting phenomena in biophysics and microbiology [28]. The following sections outline the materials, step-by-step procedures, and data analysis methods required to successfully implement this technique.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for CVD-based hydrophobic functionalization.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specifications / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Cantilevers | Force sensing probe | Tipless silicon nitride (e.g., MLCT-O10, Bruker) [28] |

| Hydrophobic Precursor | CVD active monomer | 1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorooctyltrimethoxysilane (FOTS) [28] |

| Silica/PS Particles | Colloidal probe tip | Silica (mean diameter 9.98 ± 0.31 μm) or Polystyrene (PS, 3 ± 0.01 μm) [28] |

| UV/Ozone Cleaner | Surface activation | For pre-treatment of cantilevers and substrates (1-hour treatment) [28] |

| CVD Chamber | Controlled deposition environment | Desiccator chamber with vacuum pump (e.g., Laboport N96) [28] |

| Epoxy Glue | Particle attachment | For immobilizing single particles to cantilevers [29] |

| Oxygen Plasma System | Substrate activation | For cleaning and generating reactive surface groups on coverslips [28] |

Protocol and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for AFM cantilever hydrophobic functionalization via CVD, from preparation to quality control.

Cantilever and Substrate Preparation

- Surface Activation: Begin by treating the AFM cantilevers in a UV/ozone cleaner for 1 hour. This critical step removes organic contaminants and activates the surface by generating hydroxyl groups, which is essential for strong covalent bonding with the silane-based precursor [28].

- Colloidal Probe Attachment: For tipless cantilevers, attach a single silica or polystyrene particle to the end of the cantilever using a small amount of epoxy glue. This can be performed under a microscope for precision. The glued cantilevers should then be cured under UV light for 1 hour to secure the bond [28] [29].

- Secondary Cleaning: Subject the particle-functionalized cantilevers to an additional 1-hour UV/ozone treatment. This ensures the surface of the attached particle is perfectly clean and activated for the subsequent functionalization step. UV/ozone-cleaned, silica-functionalized cantilevers can be reserved as unmodified control probes [28].

Hydrophobic Functionalization via CVD

- CVD Chamber Setup: Place the functionalized cantilevers in a desiccator chamber (the CVD chamber). Position an open vessel containing 3 mL of the hydrophobic precursor, FOTS, next to the cantilevers [28].

- Deposition Process: Evacuate the chamber using a vacuum pump (e.g., Laboport N96) and then seal it. Maintain the sealed chamber at a constant temperature of 295.15 K (approximately 22°C) for 19 hours [28].

- Mechanism: During this period, the FOTS precursor vaporizes, and its reactive monomers adsorb onto the activated cantilever and particle surfaces. A condensation reaction occurs between the methoxysilane groups of FOTS and the surface hydroxyl groups, forming a stable, covalently bonded fluorocarbon monolayer that confers hydrophobicity [28].

Characterization and Validation

- Contact Angle Measurement: Characterize the success of the functionalization using the sessile drop method. A successful FOTS coating will yield a high water contact angle, typically exceeding 90°, indicating a hydrophobic surface. Compare this to the hydrophilic character of an unmodified silica control [28].

- Imaging and Potential Analysis: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to verify the integrity and placement of the colloidal particle on the cantilever [28]. Electrophoretic light scattering can be employed to determine the zeta potential of the functionalized particles, confirming a change in surface charge consistent with fluorocarbon coverage [28].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Expected Experimental Outcomes

Table 2: Expected quantitative outcomes for hydrophobic functionalization and force spectroscopy.

| Parameter | Unmodified Silica Surface (Control) | FOTS-Modified Surface (Experimental) | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Contact Angle | Low (< 30°) [28] | High (> 90°) [28] | Sessile Drop Method |

| Surface Zeta Potential | Highly negative in water [28] | Less negative or neutral [28] | Electrophoretic Light Scattering |

| Dominant AFM Force | Electrostatic repulsion, Hydration forces [28] | Hydrophobic attraction [28] | AFM Force-Distance Curves |

| Typical Jump-in Distance | Short or non-existent | Long-range (tens of nanometers) [28] | AFM Force-Distance Curves |

Data Analysis and Force Curve Interpretation

- Data Processing: Process force-distance curves using specialized software (e.g., JPK Data Processing) to convert raw piezo displacement and cantilever deflection data into force-versus-separation curves. The contact point (zero separation) must be accurately identified, which for hydrophobic surfaces is typically defined at the end of the characteristic "jump-in" event caused by attractive forces [28].

- Model Fitting: Fit the processed force data with an extended DLVO (Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek) model. The standard DLVO theory accounts for Electric Double Layer (EDL) repulsion and van der Waals (vdW) attraction. For hydrophobic surfaces, an additional exponential term for hydrophobic attraction must be included to accurately model the observed long-range interaction [28]. The total interaction energy can be described as:

- ( F{Total} = F{EDL} + F{vdW} + F{Hydrophobic} )

Where the hydrophobic component is often modeled as ( F_{Hydrophobic} = -C \cdot e^{-D / \lambda} ), with

Cbeing a constant related to the interfacial tension andλthe decay length.

- ( F{Total} = F{EDL} + F{vdW} + F{Hydrophobic} )

Where the hydrophobic component is often modeled as ( F_{Hydrophobic} = -C \cdot e^{-D / \lambda} ), with

Application in Biofilm Receptor Studies