AFM Nanomechanics in Biofilm Research: Decoding the Role of Capsular Polysaccharides

This article explores the pivotal role of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) nanomechanics in elucidating the structure-function relationship of capsular polysaccharides within bacterial biofilms.

AFM Nanomechanics in Biofilm Research: Decoding the Role of Capsular Polysaccharides

Abstract

This article explores the pivotal role of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) nanomechanics in elucidating the structure-function relationship of capsular polysaccharides within bacterial biofilms. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge with cutting-edge methodologies. The content covers the biomechanical principles of capsule-mediated adhesion, advanced AFM techniques for in situ analysis, strategies to overcome analytical challenges, and validation through comparative studies with other antibiofilm polysaccharides. By integrating the latest research, this review provides a comprehensive framework for leveraging AFM insights to develop novel anti-biofilm strategies, directly addressing the pressing challenge of antimicrobial resistance.

Capsular Polysaccharides and Biofilm Architecture: A Biomechanical Foundation

Bacterial biofilms represent a structured microbial community embedded within a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. This complex matrix determines the physicochemical properties of biofilms and provides critical protection against environmental stresses, including antibiotics. Recent advances in atomic force microscopy (AFM) nanomechanics have enabled unprecedented high-resolution analysis of EPS components, particularly capsular polysaccharides, revealing new insights into their structural organization and functional properties. This technical guide examines biofilm architecture through the lens of AFM methodologies, providing researchers with foundational knowledge and experimental protocols for investigating the nanomechanical properties of EPS constituents in biofilm research.

The EPS Matrix: Composition and Functional Architecture

The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix establishes the functional and structural integrity of biofilms, constituting 50% to 90% of the total organic matter [1]. This matrix provides compositional support and protection for microbial communities in harsh environments [1]. Contrary to historical understanding, the EPS is a complex, dynamic assemblage of multiple biopolymer classes beyond polysaccharides.

Core Components of the EPS Matrix

The biofilm matrix is composed of several key macromolecular components, each contributing distinct functional properties:

Polysaccharides: Often heteropolymers containing neutral and charged sugar residues with organic/inorganic substituents [2]. Common examples include alginate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms, polysaccharide intercellular adhesion (PIA) in staphylococci, and cellulose in various environmental biofilms [3] [4].

Proteins: Including structural proteins that stabilize biofilm architecture and extracellular enzymes that facilitate nutrient acquisition and matrix remodeling [2]. Enzymes such as dispersin B, proteases, and DNases enable biofilm reorganization and dispersal [2].

Extracellular DNA (e-DNA): Provides structural integrity and facilitates genetic exchange [3]. In P. aeruginosa biofilms, e-DNA forms distinct grid-like structures and functions as an intercellular connector [3].

Lipids and Biosurfactants: Influence surface properties including wettability and charge, affecting bacterial adhesion and motility [2].

Membrane Vesicles: Act as "parcels" containing enzymes and nucleic acids, transported through the EPS matrix to participate in nutrient acquisition, gene exchange, and biological warfare [3].

Functional Classification of EPS Components

Table 1: Functional Classification of Major EPS Components Based on Neu and Lawrence's System [3]

| Function | EPS Component | Role in Biofilm |

|---|---|---|

| Constructive | Neutral polysaccharides, Amyloids | Structural framework and stability |

| Sorptive | Charged/hydrophobic polysaccharides | Ion exchange, sorption of dissolved substances |

| Active | Extracellular enzymes | Polymer degradation, nutrient acquisition |

| Surface-active | Amphiphilic compounds, Membrane vesicles | Interface interactions, export from cells |

| Informative | Lectins, Nucleic acids | Specificity recognition, genetic information |

| Redox active | Bacterial refractory polymers | Electron donor/acceptor functions |

| Nutritive | Various polymers | Source of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus |

AFM Methodologies for EPS Nanomechanical Characterization

Atomic force microscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating the structural and mechanical properties of biofilms at nanoscale resolution. Recent technological advances have addressed traditional limitations in imaging area and automation, enabling more comprehensive analysis of biofilm architecture.

Advanced AFM Imaging Techniques

Large Area Automated AFM: Traditional AFM imaging is limited to areas <100 μm, restricting analysis of heterogeneous biofilm structures. Recent developments combine automated large-area AFM with machine learning to capture high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas [5]. This approach enables visualization of spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology during early biofilm formation previously obscured by technical limitations [5].

Multiparametric PeakForce Tapping (PFT-AFM): This advanced mode enables high-resolution imaging of live bacteria under physiological conditions while simultaneously mapping nanomechanical properties [6]. The technique provides tight control over applied force (typically 1-6 nN), minimizing sample damage while allowing quantitative measurement of elastic modulus through Derjaguin-Muller-Toporov (DMT) models [6].

Experimental Protocol: AFM Analysis of Biofilm Mechanical Properties

Sample Preparation:

- Grow biofilms on appropriate substrates (e.g., PFOTS-treated glass coverslips) for selected time periods [5].

- Gently rinse to remove unattached cells while preserving EPS structure.

- For live cell imaging, immobilize bacteria in porous polycarbonate membranes to maintain physiological conditions [6].

AFM Imaging Parameters:

- Scanning Force: 1-6 nN peak force, optimized for EPS penetration while minimizing cellular damage [6].

- Scan Rate: 0.5-1.0 Hz, depending on required resolution and area.

- Resolution: 512 × 512 pixels for cellular-level analysis; higher resolutions (1024 × 1024) for subcellular features.

- Environment: Liquid phase for live cells; ambient conditions for fixed samples.

Data Analysis:

- Image Stitching: Apply machine learning algorithms to combine multiple high-resolution scans into seamless millimeter-scale images [5].

- Mechanical Mapping: Calculate elastic modulus (E) from force-distance curves using appropriate contact-mechanical models (DMT recommended) [6].

- Morphometric Analysis: Quantify cell dimensions, orientation, and spatial distribution using automated segmentation algorithms [5].

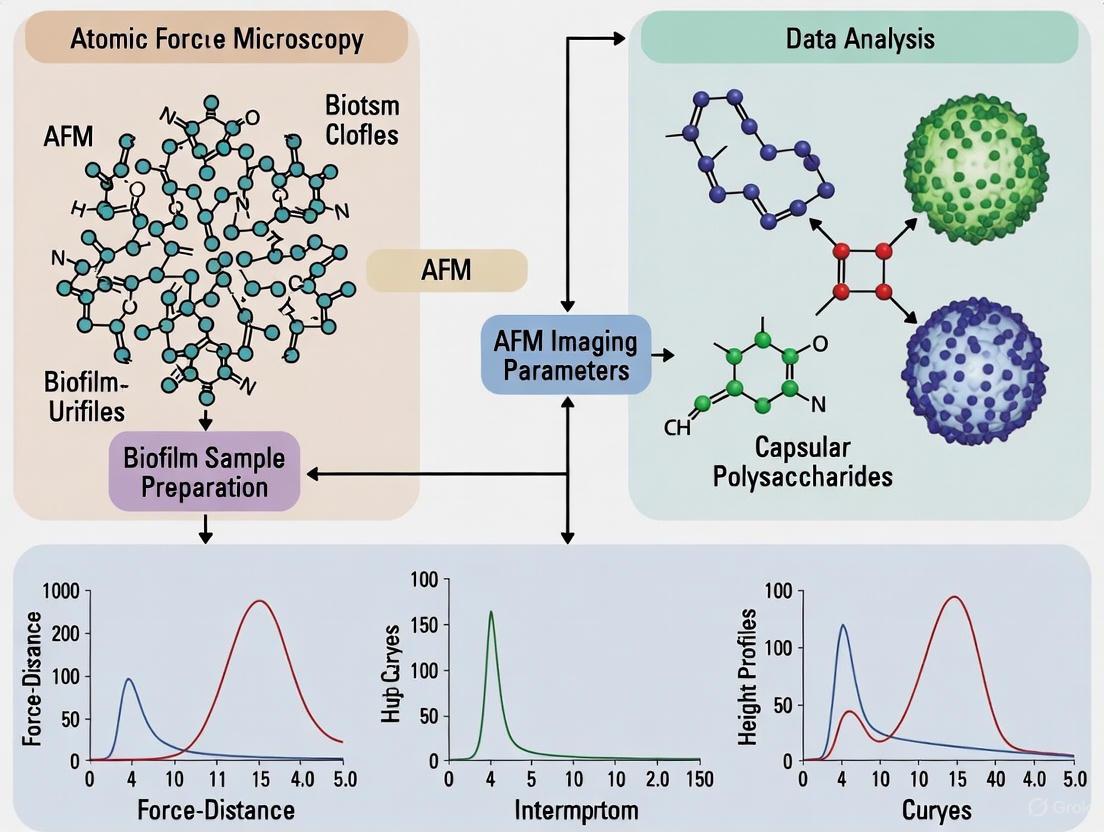

Figure 1: AFM Nanomechanics Workflow for Biofilm EPS Characterization. This diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational pipeline for analyzing the mechanical properties of EPS matrix components using advanced AFM methodologies.

Nanomechanical Properties of Capsular Polysaccharides

Capsular polysaccharides represent a critical EPS component with significant implications for biofilm mechanical properties and antibiotic resistance. AFM nanomechanics has revealed fundamental structure-function relationships in these biopolymers.

Structural Diversity of Bacterial Polysaccharides

Table 2: Common Bacterial Exopolysaccharides and Their Properties [4] [1]

| Polysaccharide | Producing Bacteria | Chemical Characteristics | Biofilm Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | Pseudomonas spp., Azotobacter vinelandii | Polyanionic | Cell association, protection |

| Polysaccharide Intercellular Adhesion (PIA) | Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis | Polycationic, β-1-6-linked N-acetylglucosamine | Cellular aggregation, adhesion |

| Cellulose | Acetobacter xylinum, Various bacteria | Neutral | Structural integrity, attachment |

| Pel | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Neutral, composition unknown | Aggregation, pellicle formation |

| Xanthan | Xanthomonas campestris | Anionic heteropolymer | Structural stability |

| Hyaluronic acid | Streptococcus equi | Linear glycosaminoglycan | Adhesion, immune evasion |

Structure-Function Relationships in Antibiofilm Polysaccharides

Recent research has identified specific capsular polysaccharides with non-biocidal antibiofilm activity. Screening of 31 purified capsular polysaccharides revealed that active compounds share distinctive biophysical properties [7]:

- High Intrinsic Viscosity: Active polysaccharides demonstrate intrinsic viscosity >7 dl/g, significantly higher than inactive compounds [7].

- Molecular Weight Dependence: Size integrity is critical for antibiofilm activity; minor fragmentation of G2cps polysaccharide (average MW 800 kDa) resulted in complete loss of function [7].

- Electrokinetic Signature: Active macromolecules display distinct electrophoretic mobility under applied electric fields, characterized by high density of electrostatic charges and permeability to fluid flow [7].

Experimental Protocol: Screening Antibiofilm Polysaccharides

Polysaccharide Characterization:

- Purification: Isolate capsular polysaccharides from bacterial cultures using standard extraction protocols.

- Structural Analysis: Employ High-Performance Anion-Exchange Chromatography with Pulsed Amperometric Detection (HPAEC-PAD) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for composition analysis [7].

- Molecular Weight Determination: Utilize High Performance Size-Exclusion Chromatography coupled to Static Light Scattering (HPSEC-LS) to determine average molecular weight [7].

Biofilm Inhibition Assay:

- Static Microtiter Plate Assay: Incubate test bacteria with polysaccharides (typical concentration: 100 μg/mL) in 96-well plates [7].

- Crystal Violet Staining: Quantify biofilm biomass after appropriate incubation period.

- Dynamic Validation: Confirm results using continuous flow biofilm microfermentors under shear stress conditions [7].

- Viability Assessment: Perform colony counting to verify non-biocidal activity.

Research Reagent Solutions for EPS Characterization

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for EPS and Biofilm Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Substrates | PFOTS-treated glass, Polycarbonate membranes | Controlled surface attachment and AFM immobilization |

| Polysaccharide Standards | Vi polysaccharide, G2cps, PnPS3 | Positive controls for antibiofilm activity assays |

| Analytical Standards | Monosaccharide references, Molecular weight markers | Chromatographic calibration and structural validation |

| Enzymatic Tools | Dispersin B, Proteases, DNases | Selective EPS component degradation for functional studies |

| Staining Agents | Crystal violet, Fluorescent lectins | Biofilm visualization and quantification |

| Chromatography Media | HPAEC-PAD columns, HPSEC matrices | Polysaccharide separation and characterization |

EPS Matrix Architecture Visualized Through AFM

High-resolution AFM has revealed unprecedented details of biofilm EPS architecture, providing insights into the structural organization of matrix components:

Nanoscale Network Organization

Imaging of Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms reveals a preferred cellular orientation with distinctive honeycomb patterning during early biofilm development [5]. AFM visualizes flagellar structures (20-50 nm in height) extending tens of micrometers across surfaces, forming bridging connections between cells [5].

In live Group B Streptococcus, multiparametric AFM reveals a net-like peptidoglycan architecture that stretches and stiffens in response to turgor pressure [6]. This network comprises parallel-oriented glycan strands that undergo structural rearrangement under osmotic stress, demonstrating the dynamic nature of matrix organization [6].

Matrix Architecture and Mechanical Response

Figure 2: EPS Matrix Response to Environmental Stimuli. This diagram illustrates the relationship between environmental cues, structural reorganization of EPS components, and resulting changes in mechanical properties that determine biofilm function.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The nanomechanical understanding of EPS components has significant implications for developing novel anti-biofilm strategies. Rather than traditional biocidal approaches, emerging interventions target the structural integrity of the EPS matrix:

- Matrix Disruption Therapies: Enzymatic degradation of key EPS components (e.g., DNases, dispersin B) can enhance antibiotic penetration [2].

- Non-biocidal Antiadhesion Agents: High molecular weight capsular polysaccharides with specific electrokinetic properties can prevent initial bacterial attachment without inducing resistance [7].

- Surface Engineering: Materials modified with antibiofilm polysaccharides can resist colonization in medical device applications [7] [2].

The integration of AFM nanomechanics with biochemical analysis provides a powerful framework for understanding structure-function relationships in biofilm EPS matrices, offering new avenues for controlling biofilm-associated infections in clinical settings.

Biofilms are structured communities of microbial cells embedded in a self-produced extracellular matrix, which confers significant tolerance to antimicrobial agents and host immune responses [8]. The polysaccharide components of this matrix are critical determinants of biofilm architecture, mechanics, and virulence. This whitepaper examines four key polysaccharides—PNAG, alginate, Psl, and Pel—within the context of atomic force microscopy (AFM) nanomechanics research. We provide a comprehensive technical analysis of their structural properties, functional roles, and biomechanical characteristics, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to drug development professionals seeking to disrupt pathogenic biofilms.

The biofilm matrix represents a critical interface between bacterial cells and their environment, strengthening the community structure while retaining mechanical plasticity [8]. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), particularly polysaccharides, typically constitute up to 85% of the biofilm volume and create heterogeneous local microenvironments that promote bacterial persistence [8]. The World Health Organization has classified antibiotic-resistant infections among its top 10 research priorities, with biofilm-related complications contributing significantly to the estimated 7 million annual deaths from antimicrobial resistance [8]. The ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) frequently employ biofilm formation as a key resistance mechanism, enabling them to evade conventional antibiotic treatments [8]. Within this context, understanding the nanomechanical properties of matrix polysaccharides through techniques like AFM provides crucial insights for developing novel anti-biofilm strategies.

Polysaccharide Profiles: Structure, Function, and Nanomechanics

Comprehensive Polysaccharide Characteristics

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key biofilm polysaccharides

| Polysaccharide | Primary Organisms | Chemical Structure | Function in Biofilm | AFM Nanomechanical Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (mucoid variants) | Acetylated copolymer of β-1,4-linked L-guluronic and D-mannuronic acids [9] | Protection from host defenses (scavenges reactive oxygen species), antibiotic resistance, structural integrity [9] | Overproduction creates highly structured, sticky biofilms; architectural changes increase resistance to antimicrobials [10] [9] |

| Psl | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (nonmucoid strains) | Mannose- and galactose-rich polysaccharide [9] | Initial surface attachment, structural scaffold, cell-cell interactions, biofilm architecture maintenance [9] | Serves as receptor for biofilm-tropic bacteriophages [11]; helical surface pattern on individual bacteria [11] |

| Pel | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Positively charged, partially deacetylated α-1,4-linked N-acetylgalactosamine polymer [12] | Cell-to-cell interactions, cationic matrix component, binds eDNA, aminoglycoside antibiotic protection [12] | Glycoside hydrolase processing alters biofilm biomechanics; exists in cell-associated (HMW) and secreted (LMW) forms with distinct mechanical properties [12] |

| PNAG | Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and other species | β-1,6-linked N-acetylglucosamine polymer | Adhesion, structural integrity, immune evasion | AFM nanomechanics studies correlate abundance with surface parameters and viability [13] |

Pathophysiological Significance

The clinical implications of these polysaccharides are substantial. Alginate overproduction in P. aeruginosa is particularly associated with worsening clinical prognosis in cystic fibrosis patients, where mucoid variants emerge as the predominant lung pathogen [9]. Alginate appears to protect bacteria from the consequences of inflammation by scavenging free radicals released by activated macrophages and providing protection from phagocytic clearance [9]. Despite antibodies to alginate being found in chronically infected CF patients, these antibodies fail to mediate opsonic killing of P. aeruginosa [9].

Psl plays a critical role in the virulence of P. aeruginosa during infections. It interferes with complement deposition and neutrophil functions, including phagocytosis and ROS production [11]. Moreover, Psl enhances the intracellular survival of phagocytosed P. aeruginosa and improves bacterial survival in mouse models of lung and wound infection [11].

Pel contributes significantly to biofilm resilience through its unique cationic nature, which enables it to bind extracellular DNA (eDNA) and host-derived anionic polymers found in cystic fibrosis sputum, helping to form a structural core and reduce susceptibility to antibiotic and mucolytic treatments [12]. Recent research has demonstrated that glycoside hydrolase processing of the Pel polysaccharide significantly alters biofilm biomechanics and P. aeruginosa virulence in infection models [12].

AFM Nanomechanics in Biofilm Polysaccharide Research

Fundamental AFM Methodologies

Atomic force microscopy provides unparalleled capabilities for characterizing the nanomechanical properties of biofilm polysaccharides under near-physiological conditions. AFM operates by measuring the forces between a sharp tip (typically with radius of 1-20 nm) and the sample surface, with forces in the range of 10⁻¹¹ N to 10⁻⁷ N enabling ultra-sensitive measurements without excessive sample disruption [14]. Key operational modes for biofilm research include:

- Contact Mode: Provides high resolution but generates lateral forces that may be problematic for soft polysaccharide samples [14].

- Tapping Mode: The cantilever oscillates at its resonance frequency, briefly tapping the surface, which minimizes lateral forces and makes it ideal for soft, irregular biofilm samples [14].

- Non-contact Mode: The cantilever vibrates with smaller amplitude without touching the surface, exerting minimal force but offering less precise height measurements [14].

- Force Spectroscopy: Measures force-distance curves to determine interaction forces, adhesion properties, and elastic modulus (Young's modulus) of matrix components [14].

- Phase Imaging: Records the phase shift between the driven cantilever oscillation and its actual response, providing qualitative information about sample hardness, elasticity, and adhesion [14].

Experimental Workflow for Polysaccharide Characterization

The following diagram illustrates a typical AFM workflow for analyzing the nanomechanical properties of biofilm polysaccharides:

Representative Experimental Protocols

AFM Analysis of Alginate Overproduction Effects

Objective: To quantify the effect of alginate overproduction on the nanomechanical properties of P. aeruginosa biofilms [10].

Methodology:

- Cultivate wild-type and mucoid (rpoN mutant) P. aeruginosa strains to establish biofilms

- Use confocal laser scanning microscopy to confirm structural differences in biofilms

- Perform AFM measurements in tapping mode to minimize sample damage

- Collect force-distance curves at multiple locations (minimum 10 points per sample)

- Calculate adhesion forces from retraction curves

- Compare topographic features and stickiness between strains at attachment, establishment, and maturation stages

Key Findings: Biofilms formed by the alginate-overproducing rpoN mutant were significantly stickier during attachment and establishment stages compared to wild-type strains. This difference in stickiness was greatly reduced during the maturation stage, possibly due to cytosolic contents released from dead cells in wild-type biofilms [10].

Nanomechanical Assessment of Capsular Polysaccharides

Objective: To determine the relationship between capsular polysaccharide organization and biofilm formation using AFM nanomechanics [15].

Methodology:

- Prepare isogenic wild-type and capsular mutants of Klebsiella pneumoniae

- Perform in situ nanomechanical measurements using AFM force spectroscopy

- Conduct theoretical modeling of the mechanical data

- Correlate nanomechanical properties with static microtiter plate biofilm assays

- Analyze how type 3 fimbriae influence capsular organization and mechanics

Key Findings: The organization of the capsule significantly influences bacterial adhesion and subsequent biofilm formation. The presence of type 3 fimbriae affects capsular organization, demonstrating the interplay between different surface structures in determining nanomechanical properties relevant to biofilm development [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for polysaccharide and AFM studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscope | Equipped with tapping mode, force spectroscopy, and liquid cell capabilities | Nanomechanical characterization of biofilm matrix components under physiological conditions [14] |

| AFM Cantilevers | Si or Si₃N₄ tips with spring constants 0.1-5 N/m, tip radius 1-20 nm | Optimized for soft biological samples; smaller radii provide higher resolution [14] |

| Alginate Lyase | Enzyme specific for alginate degradation | Experimental degradation of alginate to study its functional contribution to biofilm resistance [9] |

| Crystal Violet | 0.1-1% aqueous solution | Standard biofilm biomass quantification through microtiter plate assays [12] |

| PelA Hydrolase Domain (PelAhPa) | Recombinant protein, residues 47-303 | Exogenous addition to disrupt Pel-dependent biofilms; study of Pel polysaccharide processing [12] |

| Conductive AFM Tips | Metal-coated cantilevers with controlled conductivity | Investigation of electrostatic properties of polysaccharides in KPFM mode [14] |

| Psl-Specific Bacteriophages | Clew-1 phage from Bruynoghevirus family | Tool for specifically targeting Psl-containing biofilms; studies of Psl distribution and function [11] |

Biosynthesis Pathways and Regulatory Networks

The biosynthesis of biofilm polysaccharides involves complex pathways with sophisticated regulation. The following diagram illustrates the key biosynthetic and regulatory elements for P. aeruginosa polysaccharides:

Emerging Research Applications and Therapeutic Approaches

Recent advances in understanding polysaccharide nanomechanics have enabled novel therapeutic approaches. One promising strategy involves exploiting the Psl polysaccharide as a receptor for biofilm-tropic bacteriophages. The Clew-1 bacteriophage specifically binds to Psl, enabling it to disrupt P. aeruginosa biofilms and replicate within biofilm bacteria despite inefficiently infecting planktonic cells [11]. This Psl-dependent phage demonstrates reduced bacterial burden in mouse models of P. aeruginosa keratitis, suggesting a targeted approach for biofilm-associated infections [11].

Another innovative approach involves using capsular polysaccharides with antibiofilm activity. Screening of 31 purified capsular polysaccharides revealed that active antibiofilm polymers share distinct biophysical and electrokinetic properties, including high intrinsic viscosity and specific charge characteristics [16]. These non-biocidal polysaccharides, such as Vi, MenA, and MenC, prevent bacterial adhesion without killing cells, potentially reducing selective pressure for resistance [16].

Glycoside hydrolase enzymes present another promising therapeutic avenue. Research has demonstrated that the glycoside hydrolase activity of PelA decreases adherent biofilm biomass and generates the low molecular weight secreted form of Pel exopolysaccharide, which in turn influences biofilm biomechanics and reduces P. aeruginosa virulence in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster infection models [12]. This suggests that engineered hydrolases could be developed to modulate biofilm properties and enhance susceptibility to conventional antibiotics.

The integration of AFM nanomechanics with biofilm research has provided unprecedented insights into the structure-function relationships of key polysaccharides. Alginate, Psl, Pel, and PNAG each contribute distinct mechanical and protective properties to the biofilm matrix, enabling bacterial communities to withstand environmental stresses, antimicrobial treatments, and host immune responses. The continuing refinement of AFM methodologies, combined with emerging therapeutic approaches that target these polysaccharides, holds significant promise for combating biofilm-associated infections. Future research should focus on correlating nanomechanical measurements with clinical outcomes to facilitate the translation of these findings into effective anti-biofilm strategies.

The Capsule as a Critical Virulence Determinant

The bacterial capsule is a dense, well-structured polymer layer that surrounds the cell envelope of many bacterial pathogens. Primarily composed of high molecular weight polysaccharides (capsular polysaccharides, or CPS), this layer forms a viscous, hydrated gel that constitutes the outermost interface between the pathogen and its host environment [17]. In Gram-negative bacteria, these polymers are often covalently anchored to lipids in the outer membrane, while in Gram-positive bacteria, they are typically attached to the peptidoglycan cell wall [18]. Historically, the capsule was first described as a "halo" around bacterial cells by Pasteur in 1881, with its carbohydrate nature elucidated by Avery in 1925 [17]. Far from being a mere structural component, the capsule is now recognized as a critical virulence factor that enables pathogens to evade host immune defenses, establish infections, and persist in hostile environments. Its role is particularly crucial in biofilm formation, where it contributes to initial adhesion, structural stability, and protection against antimicrobial agents. The following sections provide an in-depth examination of the capsule's biosynthesis, its multifaceted functions in virulence, and the advanced nanomechanical techniques used to study its properties, with a specific focus on insights gained from atomic force microscopy (AFM) in biofilm research.

Biosynthesis and Structural Diversity of Capsules

Biosynthetic Pathways

Bacteria synthesize their capsular polysaccharides through several distinct biochemical pathways, with the choice of pathway depending on the bacterial species and the specific capsule type. The most prevalent mechanisms are the Wzx/Wzy-dependent pathway, the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter-dependent pathway, and the synthase-dependent pathway [17].

The Wzx/Wzy-dependent pathway is employed by over 90% of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes and is fundamental to Group I and IV capsules in Gram-negative bacteria [17]. This mechanism involves the assembly of oligosaccharide repeat units on a lipid carrier (undecyl isoprene phosphate) on the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane. The Wzx "flippase" enzyme then translocates these units across the membrane, and the Wzy polymerase links them together to form the full-length polysaccharide chain [17]. In Klebsiella pneumoniae, a leading model organism for capsule studies, this process is initiated by WbaP, a galactose phosphotransferase that links galactose to the undecaprenyl phosphate lipid carrier [19]. Subsequent glycosyltransferases add further sugars, with the Wzx flippase moving the growing chain to the periplasm where Wzy polymerase extends it. The tyrosine kinase Wzc regulates chain length, and the outer membrane protein Wza exports the completed polysaccharide, which is then anchored to the cell surface by Wzi [19].

In contrast, the ABC transporter-dependent pathway involves complete polymerization of the polysaccharide chain in the cytoplasm before it is transported across the inner membrane by an ABC transporter complex [17]. While the Wzx/Wzy and ABC transporter mechanisms differ in their assembly sites, both utilize outer membrane proteins from the polysaccharide export family to transport the finished capsule across the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.

Less common is the synthase-dependent mechanism, utilized by S. pneumoniae serotypes 3 and 37, where a single enzyme complex is responsible for both polymerization and translocation of the capsule [17]. Some bacteria, notably Bacillus anthracis, produce capsules composed primarily of polypeptides (poly-D-glutamic acid) rather than polysaccharides, with biosynthesis involving the transfer of activated glutamate units to a membrane-bound polyglutamyl acceptor chain [17].

Capsular Serotypes and Virulence

Capsular types are distinguished by variations in monosaccharide composition, glycosidic linkage positions, stereochemistry (L or D configuration), and chemical modifications such as O-acetylation [17]. This structural diversity gives rise to numerous serotypes (or serovars), which are critical for classifying bacterial strains and understanding their pathogenic potential.

- Escherichia coli produces approximately 80 distinct capsule types, categorized into four groups (I-IV), including the polysialic acid (PSA)-containing K1 capsule and the heparosan-containing K5 capsule [17].

- Streptococcus pneumoniae has 93 identified capsular serotypes, with significant variation in their invasive potential. Serotypes 1, 4, 5, 8, 12F, 18C, and 19A are highly invasive, while 6A, 6B, 11A, and 23F are less aggressive [17].

- Klebsiella pneumoniae produces 77 recognized CPS serotypes, with the K2 serotype being particularly associated with bacteremia and hypervirulence [19].

The virulence of different serotypes is closely linked to their specific chemical structures. For instance, highly virulent K. pneumoniae K2 strains lack the mannose-α-2/3-mannose structure present in less virulent strains [17]. Furthermore, pathogens can undergo capsular switching through genetic recombination, altering their surface antigens to evade host immunity. For example, S. pneumoniae serotype 11E evolves from serotype 11A through mutations in the wcjE gene, enabling escape from ficolin-2-mediated phagocytosis during invasive disease [17]. This structural plasticity underscores the capsule's role in adaptive virulence and presents a challenge for both typing and therapeutic targeting. Advanced computational tools like Kaptive Web have been developed to rapidly type Klebsiella K and O loci, facilitating the identification of capsule types associated with high virulence [17].

The Capsule as a Virulence Factor

The capsule contributes to bacterial pathogenicity through multiple mechanisms, primarily by acting as a physical barrier that impedes host immune recognition and response. Its functions span from initial adhesion to survival within the host, making it indispensable for successful infection.

Immune Evasion and Serum Resistance

The capsule's most critical role is protecting bacteria from phagocytosis by host immune cells. The polysaccharide layer masks antigenic surface proteins, preventing recognition by phagocytic receptors [19]. This protective effect is clearly demonstrated in Klebsiella pneumoniae, where the capsule is essential for survival in human blood. Wild-type encapsulated K. pneumoniae can resist phagocytosis and complement-mediated killing, whereas non-encapsulated mutants (e.g., Kpn2146Δwza) are rapidly cleared in whole blood and plasma assays [19]. In vivo experiments using Galleria mellonella larvae infection models confirm the dramatically decreased virulence of capsule-deficient mutants [19].

A particularly effective immune evasion strategy involves the production of capsules that mimic host tissue molecules. Capsules composed of polysialic acid (PSA), hyaluronan (HA), heparosan, or chondroitin are structurally identical to mammalian glycans [18]. This molecular mimicry renders these capsules "self" antigens, preventing the host from mounting an effective antibody response. Pathogens bearing such non-immunogenic coatings, including E. coli K1 (PSA) and Group A Streptococcus (HA), can thus reside in host tissues for extended periods, reaching high population densities that enable disease progression [18].

Adhesion, Invasion, and Biofilm Formation

While the capsule was traditionally thought to inhibit adhesion by sterically blocking adhesins, research reveals a more nuanced relationship. The capsule plays a context-dependent role in bacterial interactions with host cells. In K. pneumoniae, for instance, encapsulated and non-encapsulated strains show similar adherence levels to A549 lung epithelial cells, but the non-encapsulated mutant exhibits moderately higher internalization, suggesting the capsule may limit invasion into certain cell types [19].

In biofilm formation, the capsule and other exopolysaccharides are fundamental components of the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix [20]. Biofilm development proceeds through defined stages: (1) reversible attachment, (2) irreversible attachment, (3) microcolony formation, (4) maturation, and (5) dispersion [21] [22]. The capsule contributes to multiple stages of this process. During initial attachment, the capsule can facilitate bacterial approach to surfaces through non-specific interactions. During irreversible attachment and maturation, the capsule provides structural integrity and stability to the biofilm architecture [15].

The capsule's organization and properties are influenced by other surface structures, particularly type 3 fimbriae, which can affect capsular organization and thereby modulate bacterial adhesion and biofilm development [15]. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a model organism for biofilm studies, exopolysaccharides like Psl, Pel, and alginate are crucial for surface attachment, structural stability, and resistance to environmental stresses [21]. The secondary messenger cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) is a central regulator of this process; high intracellular levels of c-di-GMP promote exopolysaccharide production and repress flagellar motility, facilitating the transition from planktonic to biofilm growth [21] [22].

Table 1: Key Virulence Functions of Bacterial Capsules

| Function | Mechanism | Example Pathogens |

|---|---|---|

| Phagocytosis Resistance | Masks surface antigens; prevents complement deposition and opsonization | Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae [19] |

| Molecular Mimicry | Composed of polysaccharides identical to host glycans (e.g., HA, PSA) | E. coli K1 (PSA), Group A Streptococcus (HA) [18] |

| Biofilm Formation | Contributes to EPS matrix; aids in adhesion and structural stability | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae [15] [20] |

| Environmental Adaptation | Acts as a hydrogel to protect against osmotic stress and desiccation | Klebsiella pneumoniae [23] |

| Antibiotic Resistance | Limits antimicrobial penetration through the biofilm matrix | ESKAPE pathogens (K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, etc.) [20] |

AFM Nanomechanics in Capsule and Biofilm Research

Atomic force microscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating the nanomechanical properties of bacterial capsules and their role in biofilm formation. Unlike traditional microscopic techniques, AFM allows for in situ quantitative measurements of living bacterial cells under physiological conditions, providing unprecedented insights into the biophysical behavior of the capsular layer.

Probing Capsular Mechanics and Organization

AFM-based force spectroscopy involves bringing a functionalized tip into contact with the bacterial surface and retracting it to obtain force-distance curves. These curves reveal information about the elasticity, adhesion, and topography of the capsule at the nanoscale.

Seminal AFM studies on Klebsiella pneumoniae have demonstrated that the polysaccharide capsule behaves as a responsive polymer hydrogel [23]. This hydrogel structure can undergo rapid, reversible collapse and recovery in response to changes in osmotic pressure, acting as an "ion sponge" that protects the cell from osmotic stress [23]. This adaptive property is crucial for survival in diverse host environments.

Furthermore, AFM has elucidated the relationship between capsule organization and biofilm formation. Theoretical modeling of AFM nanomechanical data shows that the spatial organization of the capsule significantly influences bacterial adhesion—the critical first step in biofilm development [15] [24]. The presence of surface appendages like type 3 fimbriae can alter capsular organization, thereby modulating the bacterium's adhesive properties and its potential to form biofilms [15].

Experimental Workflow for AFM Analysis

A typical AFM nanomechanics experiment targeting bacterial capsules involves the following key steps:

- Strain Selection and Mutant Generation: Isogenic mutants deficient in capsule synthesis (e.g., Δwza mutants lacking the exporter protein) or other related structures (e.g., fimbriae) are constructed for comparison with the wild-type strain [19] [15]. This allows for direct attribution of observed effects to the capsule.

- Sample Preparation: Bacterial cells are cultured under appropriate conditions to ensure capsule expression. Cells are then immobilized onto a solid substrate (e.g., a poly-L-lysine-coated glass slide or membrane filter) without chemical fixation to preserve native capsule structure and mechanical properties [15] [24].

- AFM Force Measurement: A cantilever with a defined tip (often silicon nitride) is used to probe the surface of immobilized cells in a liquid environment. Hundreds of force-distance curves are acquired across the surface of multiple individual bacteria to ensure statistical robustness [15] [23].

- Data Analysis: Force curves are analyzed to extract nanomechanical parameters, including:

- Young's Modulus: A measure of cellular stiffness, indicating the deformability of the capsule.

- Adhesion Force: The force required to separate the tip from the surface, reflecting the stickiness of the capsular layer.

- Turgor Pressure: The internal pressure of the cell, which can be inferred from the force curves [23].

- Correlation with Phenotypic Assays: AFM data is correlated with results from standard microbiological assays, such as static microtiter plate biofilm assays, to link nanomechanical properties with macroscopic phenotypic outcomes like biofilm formation capacity [15].

Diagram 1: AFM Nanomechanics Workflow for Capsule Study. This flowchart outlines the key experimental steps, from biological preparation to data interpretation, for investigating bacterial capsules using Atomic Force Microscopy.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments used to elucidate the role of the capsule in virulence and biofilm formation, serving as a practical guide for researchers.

Protocol 1: Generation of a Capsule-Deficient Mutant

The construction of an isogenic, capsule-deficient mutant is a fundamental step for comparative studies. The following protocol, adapted from a study on Klebsiella pneumoniae, targets the wza gene, which encodes a conserved outer membrane polysaccharide export protein [19].

- Primer Design: Design primers to amplify the target gene (wza) along with approximately 500 base pairs of its upstream and downstream flanking regions. This ensures homologous recombination.

- Cloning:

- Amplify the wza region with flanking sequences via PCR and ligate the product into a suitable cloning vector (e.g., pMiniT).

- Transform the construct into an E. coli host strain (e.g., 10β) and select for transformants.

- Subclone the insert into a suicide vector (e.g., pKOV) that cannot replicate in the target pathogen.

- Allelic Exchange:

- Perform an inverse PCR on the suicide vector to remove the wza coding sequence.

- Insert a selectable marker (e.g., a spectinomycin resistance gene, aad9) in place of the deleted wza gene.

- Transform the final suicide vector (pKOV-∆wza_specR) into the wild-type K. pneumoniae strain via conjugation or electroporation.

- Select for clones where a double-crossover event has replaced the wild-type wza allele with the mutant construct, resulting in a clean, non-polar deletion. Confirm the mutation via PCR and sequencing [19].

Protocol 2: AFM Nanomechanics of Bacterial Cells

This protocol details the procedure for measuring the nanomechanical properties of encapsulated bacteria [15] [24] [23].

Bacterial Culture and Immobilization:

- Grow the wild-type and isogenic capsule mutant strains to mid-log phase under conditions that promote capsule expression.

- Gently harvest cells by centrifugation to avoid damaging the capsule. Wash and resuspend in an appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS or a defined minimal medium).

- Immobilize cells by depositing a droplet of the bacterial suspension onto a poly-L-lysine-coated glass slide or a membrane filter for 15-30 minutes. Rinse carefully with buffer to remove non-adhered cells.

AFM Force Spectroscopy:

- Mount the sample on the AFM liquid cell and immerse in the same buffer.

- Use a sharp, non-functionalized silicon nitride cantilever with a known spring constant (calibrated prior to measurements).

- Approach the central surface of a single, well-isolated bacterial cell and collect force-distance curves using a trigger force of 250-500 pN to avoid damaging the cell.

- Collect a grid of at least 256 force curves (16x16) on each cell and measure a minimum of 10 different cells per strain.

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Use appropriate software (e.g., the AFM manufacturer's software, Igor Pro, or custom scripts) to analyze the force curves.

- Fit the extending part of the force curve with a suitable model (e.g., Hertzian, Sneddon, or Johnson-Kendall-Roberts models) to derive the Young's modulus, a measure of cell stiffness.

- Analyze the retraction curves to quantify adhesion forces and work of adhesion.

- Statistically compare the distributions of Young's modulus and adhesion force between wild-type and mutant strains to determine the mechanical contribution of the capsule.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Capsule and Biofilm Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Suicide Vector (e.g., pKOV) | Facilitates allelic exchange for generating knockout mutants | Construction of isogenic capsule-deficient mutant (∆wza) in K. pneumoniae [19] |

| Poly-L-Lysine Coated Substrates | Promotes electrostatic immobilization of bacterial cells for AFM | Securing live Klebsiella cells for nanomechanical measurements without chemical fixation [15] |

| Silicon Nitride AFM Cantilevers | Probes for nanomechanical force spectroscopy; can be functionalized | Measuring elasticity and adhesion of the bacterial capsule in liquid [15] [23] |

| c-di-GMP Assay Kits | Quantify intracellular cyclic di-GMP levels, a key regulator of EPS production | Linking second messenger signaling to capsule production and biofilm phenotype [21] |

| Specific Glycosidases / Depolymerases | Enzymatically digest specific capsule polysaccharides | Confirming capsule composition; studying dispersal of capsule-dependent biofilms [17] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Understanding the capsule's role in virulence and its nanomechanical properties opens promising avenues for novel anti-infective strategies. The primary therapeutic approaches include:

- Capsule-Targeting Vaccines: Vaccines based on purified capsular polysaccharides have been successful against pathogens like S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae type b (Hib) [17]. Conjugating CPS to carrier proteins converts the T-cell-independent immune response to a T-cell-dependent one, improving immunogenicity and long-lasting immunity, especially in children [18].

- Enzymatic Dispersal: Enzymes that degrade the capsule or biofilm matrix represent a powerful therapeutic approach. For example, dispersin B degrades PNAG (poly-N-acetylglucosamine), a biofilm polysaccharide produced by staphylococci and E. coli [20]. Similarly, bacteriophage-derived depolymerases that specifically cleave capsule polysaccharides can sensitize bacteria to antibiotic treatment and host immune clearance [17].

- Inhibition of Biosynthesis and Regulation: Small molecules that disrupt capsule biosynthesis pathways or inhibit regulatory systems (like the c-di-GMP signaling network) could prevent capsule production, rendering the pathogen susceptible to host defenses [21]. The Wzx/Wzy pathway is a particularly attractive target for such inhibitors.

- Nanotechnology-Based Delivery: Nanoparticles can be engineered to deliver antibiotics or biofilm-disrupting agents directly to the site of infection, potentially penetrating the capsular barrier more effectively than free drug molecules.

The application of AFM and other biophysical techniques continues to refine our understanding of the capsule as a dynamic, responsive structure. Future research will likely focus on mapping the spatial heterogeneity of capsules within biofilms and investigating the real-time structural changes during infection. This knowledge, integrated with genomics and immunology, will be crucial for designing the next generation of antimicrobial therapies that effectively neutralize this critical virulence determinant.

Diagram 2: Therapeutic Strategies Targeting the Capsule. This diagram illustrates how different therapeutic approaches (ellipses) interact with specific biological targets (boxes) associated with the bacterial capsule and its functions.

Linking Capsular Organization to Bacterial Adhesion and Aggregation

In the field of bacterial pathogenesis, the bacterial capsule—a surface-associated polymer—and its role in adhesion present a seeming paradox. While capsules are recognized virulence factors that can resist phagocytosis, their presence might intuitively be expected to hinder the initial adhesion to surfaces, a critical first step in biofilm formation and infection [25] [17]. This review delves into the resolution of this paradox, exploring how the specific structural organization of the capsule, rather than its mere presence or absence, dictates bacterial adhesion and aggregation behaviors. Framed within the context of atomic force microscopy (AFM) nanomechanics, this guide synthesizes current research to elucidate the biophysical mechanisms through which capsules modulate bacterial interactions with surfaces and other cells, ultimately influencing biofilm architecture and virulence.

Capsular Polysaccharides: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function

Diversity and Biosynthesis

Bacterial capsules are polymers, primarily consisting of high-molecular-weight polysaccharides, secreted at the periphery of the cell wall and enveloping the entire cell [17]. In Escherichia coli, approximately 80 distinct capsular polysaccharides (K antigens) have been identified, categorized into four major groups (I-IV) [25] [17]. These include structurally diverse polymers such as polysialic acid (K1), chondroitin (K4), and heparosan (K5) [17]. Three primary pathways for capsule synthesis are recognized: the Wzx/Wzy-dependent mechanism, the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter-dependent mechanism, and the synthase-dependent mechanism [17]. The Wzx/Wzy-dependent pathway, used by over 90% of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes, involves the formation of repeat units on a lipid carrier, which are then "flipped" across the membrane by the Wzx flippase and polymerized by Wzy [17].

Biological Roles in Virulence

The capsule is a quintessential virulence determinant. Its functions extend beyond adhesion modulation to include:

- Resistance to Phagocytosis: Capsules physically shield bacterial surface components from recognition by immune cells and can be anti-phagocytic [25] [17].

- Serum Resistance: Certain capsules, such as the K1 capsule in E. coli, confer resistance to the bactericidal action of human serum, enhancing survival in blood and tissues [25].

- Protection from Desiccation and Antimicrobials: The capsule provides a protective barrier against environmental stresses and some antimicrobial agents [25] [17].

Table 1: Primary Capsule Biosynthesis Pathways in Bacteria

| Pathway | Key Features | Representative Bacteria/Serotypes |

|---|---|---|

| Wzx/Wzy-dependent | Repeat units formed on lipid carrier; flipped by Wzx and polymerized by Wzy [17]. | >90% of S. pneumoniae serotypes [17]; E. coli Group I & IV [17]. |

| ABC Transporter-dependent | Polysaccharide chains polymerized in cytoplasm and transported by ABC transporters [17]. | E. coli Group II & III [17]. |

| Synthase-dependent | A single synthase enzyme initiates, polymerizes, and translocates the capsule [17]. | S. pneumoniae serotypes 3 & 37 [17]. |

The Adhesion-Aggregation Paradox: Steric Shielding vs. Facilitation

A central question in bacterial surface interactions is how a substantial capsular layer, which can extend 0.2 to 1.0 μm from the cell surface, affects the function of shorter bacterial adhesins, such as Antigen 43 (Ag43) and AIDA-I, which protrude only about 10 nm [25]. Research has demonstrated that the capsule can sterically shield these shorter adhesins, physically blocking their receptor-target recognition and thereby abolishing Ag43-mediated cell-to-cell aggregation [25]. This phenomenon is not restricted to E. coli but can occur in other Gram-negative bacteria [25].

However, this negative interference is not absolute. The organizational state of the capsule is critical. A compact or organized capsule may indeed block adhesion, while a disorganized or loosely bound capsule may allow adhesins to function. This organizational change can be influenced by other surface structures, such as type 3 fimbriae, which can rearrange the capsule, potentially creating microdomains where adhesins can effectively engage with their targets [15]. Furthermore, in some contexts, the capsule itself can act as an adhesive, facilitating a more generalized, weak interaction with surfaces that precedes the stronger, specific interactions mediated by adhesins [15].

AFM Nanomechanics: Probing Bacterial Surfaces and Adhesive Forces

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a high-resolution form of scanning probe microscopy that has become an indispensable tool for quantifying the nanomechanical properties of bacterial surfaces [26]. The technique operates by scanning a sharp tip on the end of a cantilever over the sample surface. As the tip interacts with the sample surface, attractive or repulsive forces cause cantilever deflection, which is measured by a laser reflected into photodiodes [26]. A scanner controls the probe height, and the variance in height is used to produce a three-dimensional topographical representation [26].

Key AFM Modologies in Biofilm Research

- Contact Mode: The tip maintains constant contact with the sample surface, providing constant force and fast scanning times, though it may deform soft samples [26].

- Tapping Mode: The cantilever is oscillated at its resonance frequency, and the tip gently "taps" the surface. This mode is gentler and provides higher lateral resolution for soft, adhesive samples like bacterial cells, minimizing sample damage [26].

- Noncontact Mode: The cantilever oscillates just above its resonance frequency without touching the sample, exerting minimal force. However, it typically offers lower resolution [26].

AFM's application in biofilm research allows for the in situ measurement of bacterial adhesion forces. By functionalizing the AFM tip with specific molecules (e.g., adhesins, host receptors) or using a single bacterial cell as a probe, researchers can directly quantify the nanomechanical forces governing capsule deformation, cell-surface adhesion, and cell-cell aggregation [15].

Figure 1: AFM Experimental Workflow for Bacterial Capsule Study. This diagram outlines the key steps in an AFM-based nanomechanics study, from mode selection to data analysis.

Quantitative AFM Findings on Capsular Organization and Adhesion

AFM nanomechanics studies have provided direct, quantitative evidence linking capsular organization to adhesion. A seminal study on Klebsiella pneumoniae compared wild-type strains with specific mutants using AFM and found that the organization of the capsule, influenced by the presence of type 3 fimbriae, directly affected bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation [15]. Theoretical modeling of the mechanical data from these experiments supported the conclusion that a structured capsule can hinder adhesion, while its reorganization can facilitate it [15].

The steric blocking effect has been quantitatively demonstrated for short adhesins like Antigen 43 (Ag43). In encapsulated E. coli strains, the presence of a capsule was shown to block Ag43-mediated aggregation, a function that was restored upon loss of the capsule [25]. This supports the model where the capsule acts as a physical barrier, preventing the close cell-to-cell contact (typically within 10-12 nm) required for short adhesins to engage in homophilic or heterophilic binding [25].

Table 2: Key Quantitative Findings from AFM and Related Studies on Capsular Function

| Bacterial System | Experimental Manipulation | Key Quantitative Finding | Impact on Adhesion/Aggregation |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli [25] | Presence vs. absence of capsule | Capsule blocks Ag43 function (≈10 nm protrusion) via steric shielding [25]. | Abolished cell-to-cell aggregation; reduced biofilm formation [25]. |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae [15] | Wild-type vs. fimbriae-deficient mutants | Fimbriae alter capsular organization, measured via AFM nanomechanics [15]. | Significant change in adhesion force; modulated biofilm formation [15]. |

| Various Gram-negative bacteria [25] | Heterologous expression of Ag43 | Ag43-mediated aggregation is a general phenomenon that is disrupted by capsule [25]. | Cell aggregation is consistently blocked in the presence of a capsule [25]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: AFM-Based Analysis of Bacterial Adhesion

The following protocol outlines the key steps for assessing the role of capsular organization in bacterial adhesion using AFM, synthesizing methodologies from cited studies.

Bacterial Strain Selection and Growth

- Strains: Utilize isogenic pairs of wild-type and mutant strains (e.g., capsule-deficient mutants, fimbriae-deficient mutants) [25] [15]. For example, E. coli strains with and without the K1 or K5 capsule operon [25].

- Growth Conditions: Grow bacteria in appropriate liquid media (e.g., Luria-Bertani broth) at 37°C to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5-0.8) to ensure consistent capsule expression [25]. The culture conditions should be meticulously controlled and reported, as capsule expression can be influenced by growth phase and medium composition.

Sample Preparation for AFM

- Immobilization: Gently immobilize bacterial cells onto a solid substrate to prevent detachment during scanning. This can be achieved by:

- Poly-L-lysine Coating: Deposit a drop of bacterial suspension onto a freshly cleaved mica surface pre-coated with 0.1% (w/v) poly-L-lysine for 10-15 minutes [26].

- Mild Chemical Fixation: Optionally, use a low concentration of glutaraldehyde (e.g., 0.5-1.0%) for a short duration (5-10 min) to stabilize the cells without significantly altering surface mechanics, though this may affect native protein function.

- Washing: Gently rinse the sample with a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) to remove non-adherent cells and media components. The sample should be kept hydrated at all times.

AFM Imaging and Force Spectroscopy

- Instrumentation: Use a commercial AFM system (e.g., Bruker Multimode) [27].

- Probes: Select sharp, cantilevers with a nominal spring constant of ~0.01-0.1 N/m for force spectroscopy on soft biological samples. The probe type and approximate resonant frequency (e.g., AppNano ACT probes, ~300 kHz) should be specified [27].

- Imaging Mode: Tapping mode is highly recommended for initial topographical imaging to minimize sample damage and obtain high-resolution images of the soft, hydrated bacterial surface [26].

- Force Measurement:

- Approach-Retract Cycles: Program the AFM to perform multiple force-distance curves (≥ 1000 per sample) on different locations of the cell surface.

- Adhesion Force Quantification: The retraction curve often shows a characteristic "pull-off" event, the magnitude of which corresponds to the unbinding force or adhesion force between the tip and the sample surface.

- Tip Functionalization (Optional): To measure specific interactions (e.g., adhesin-receptor binding), the AFM tip can be functionalized with relevant proteins or sugars using linkers like PEG-bis(N-succinimidyl succinate).

Data Analysis and Statistical Validation

- Adhesion Force and Probability: Calculate the average adhesion force and the adhesion probability (percentage of force curves showing adhesion events) from the collected force-distance curves.

- Statistical Testing: Perform appropriate statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test for comparing two groups) to determine if differences in adhesion forces between strains are significant. Data should be collected from a minimum of three independent biological replicates.

- Topographical Analysis: Use AFM image analysis software (e.g., Gwyddion) to determine surface roughness and capsule dimensions [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for AFM Studies of Bacterial Capsules

| Item Category | Specific Example(s) | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | Isogenic wild-type and mutant pairs (e.g., E. coli K-12 with flu (Ag43) mutation, E. coli 1177 (O1:K1) with fim mutation) [25]. | Enable direct comparison of the functional impact of specific genes (e.g., adhesins, capsule biosynthesis, fimbriae) on adhesion and aggregation [25]. |

| Molecular Cloning Plasmids | pKKJ128 (carries flu gene for Ag43 expression), pKT274 (carries K1 capsule gene operon) [25]. | Used for genetic manipulation to complement mutations or heterologously express capsule and adhesin genes in different bacterial backgrounds [25]. |

| AFM Probes | AppNano ACT probes (nominal frequency ~300 kHz) [27]. | The physical probe that interacts with the sample; its stiffness and sharpness determine resolution and force sensitivity. |

| AFM Substrates | Freshly cleaved mica [26]. | Provides an atomically flat, clean surface for immobilizing bacterial cells for high-resolution AFM imaging. |

| Immobilization Reagents | Poly-L-lysine solution (0.1% w/v) [26]. | Promotes electrostatic adhesion of bacterial cells to the mica substrate, preventing them from being displaced by the AFM tip. |

| Software for Analysis | Gwyddion, SPIP [27]. | Used for processing and analyzing AFM images, including measuring surface roughness, particle dimensions, and generating 3D renderings. |

Figure 2: Logical Relationship Between Capsular Organization and Biofilm Outcome. This diagram illustrates the causal pathway from factors influencing capsule organization to the ultimate impact on biofilm formation, as revealed by AFM studies.

Polysaccharides are fundamental components of biological systems, playing a critical role in determining the mechanical stability of structures ranging from bacterial biofilms to marine gels and synthetic lipid vesicles. Within the context of AFM nanomechanics studies on capsular polysaccharides in biofilm research, this review examines the specific biophysical mechanisms through which polysaccharides confer mechanical integrity. We integrate quantitative force spectroscopy data, detailed experimental protocols, and structural models to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical resource for understanding and investigating polysaccharide-mediated mechanical stabilization, highlighting how these principles can be leveraged for therapeutic intervention and biomaterial design.

The mechanical properties of biological assemblies are frequently dictated by polysaccharide components that provide structural integrity, mediate environmental interactions, and determine functional behavior. In biofilm research, understanding how capsular polysaccharides confer mechanical stability is paramount for developing strategies to combat biofilm-associated infections. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) nanomechanics has emerged as a powerful technique for quantifying these properties at the molecular and cellular levels, revealing intricate relationships between polysaccharide structure and mechanical function [15]. This technical guide synthesizes current understanding of the primary biophysical mechanisms involved, supported by quantitative data and standardized methodologies to enable reproducible research in this evolving field. The insights gained not only elucidate fundamental biological principles but also inform drug delivery system design by revealing how polymer functionalization modulates mechanical properties of synthetic vesicles [28].

Quantitative Data on Polysaccharide Mechanical Properties

The mechanical behavior of polysaccharides has been quantified through various experimental approaches, revealing distinct patterns that correspond to specific structural configurations and interaction modalities. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Mechanical Signatures of Polysaccharides in Various Systems

| System Studied | Experimental Technique | Mechanical Signature | Quantified Parameters | Structural Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marine-gel biopolymers [29] | AFM Force Spectroscopy | Force-extension curves with entropic elasticity followed by chair-to-boat transitions | N/A (qualitative patterns) | Individual polysaccharide fibrils undergoing conformational changes |

| Marine-gel biopolymers (Low cross-linking) [29] | AFM Force Spectroscopy | Sawtooth patterns | N/A (qualitative patterns) | Unraveling of polysaccharide entanglements under applied force |

| Marine-gel biopolymers (High cross-linking) [29] | AFM Force Spectroscopy | Force plateaus | N/A (qualitative patterns) | Unzipping and unwinding of helical bundles |

| Marine-gel biopolymers (3D network) [29] | AFM Force Spectroscopy | Force staircases of increasing height | N/A (qualitative patterns) | Hierarchical peeling of fibrils from junction zones |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms [15] | AFM Nanomechanics | Modified adhesion properties | N/A (qualitative study) | Capsular organization influenced by fimbriae presence |

Table 2: Impact of Chondroitin Sulfate Functionalization on Lipid Vesicle Mechanics

| Vesicle Type | Experimental Technique | Stiffness Metric | Control Value | Modified Value | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOPC GUVs [28] | Micropipette Aspiration | Stretching Modulus | Reference value | Reduced | Softening effect |

| DOPC GUVs [28] | Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) | Diffusion Coefficient | 2.32 ± 0.23 μm²/s | Decreased by >10% | Reduced membrane fluidity |

| Lipid Vesicles with PEG [28] | Micropipette Aspiration | Stretching Modulus | Reference value | Unchanged or increased | No reduction in stiffness |

Table 3: Polysaccharide Coating Density Calculations

| Parameter | Value | Method of Determination |

|---|---|---|

| Chol-CS saturation concentration [28] | 50 nM | Fluorescence intensity analysis of membrane-bound vs. free Chol-CS |

| Estimated membrane density [28] | 0.4 mol% | Calculation from confocal microscopy data |

| Intermolecular distance [28] | ~6.6 nm | Based on DOPC headgroup area (0.7 nm²) |

| Hydrodynamic radius of Chol-CS [28] | >6.6 nm | Dynamic light scattering (referenced in SI) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

AFM Force Spectroscopy for Polysaccharide Networks

Atomic force microscopy force spectroscopy experiments enable the quantification of intra- and intermolecular forces within polysaccharide networks [30]. The standard protocol involves:

Sample Preparation: Marine-gel biopolymers or purified polysaccharides are deposited on freshly cleaved mica substrates and allowed to adsorb for 15-60 minutes in appropriate buffer conditions [29].

Cantilever Selection and Calibration: Soft cantilevers with spring constants of 0.01-0.1 N/m are recommended for polysaccharide studies. The precise spring constant must be determined using thermal tuning methods or reference samples [30].

Force Curve Acquisition: The AFM tip is brought into contact with the sample surface and then retracted at constant velocity (typically 0.5-1 μm/s). Thousands of force-distance curves are collected at multiple locations to build statistical understanding [30] [29].

Data Analysis:

- Convert cantilever deflection to force using Hooke's law (F = -k×d, where k is the spring constant and d is deflection)

- Identify characteristic patterns in retraction curves: entropic elasticity, sawtooth patterns, force plateaus, or force staircases

- Fit polymer stretching models (e.g., Worm-like Chain or Freely Jointed Chain) to quantify persistence lengths and contour lengths

- Map specific mechanical signatures to structural features through correlation with known chemical composition [29]

Micropipette Aspiration for Vesicle Mechanics

The effect of polysaccharides on membrane mechanical properties can be quantified using micropipette aspiration:

GUV Formation: Giant unilamellar vesicles are formed via electroformation in sucrose solution (100-200 mOsm) using lipid compositions of interest [28].

Asymmetric Functionalization: Cholesterol-conjugated polysaccharides (e.g., Chol-CS) are added to pre-formed GUVs at concentrations up to 50 nM saturation point and incubated for 30-60 minutes to allow incorporation into the outer leaflet [28].

Aspiration Setup:

- Transfer GUVs to iso-osmotic glucose solution in observation chamber

- Use micropipettes with diameters of 5-10 μm

- Apply controlled suction pressure (ΔP) of approximately 1 Pa using precision pressure control system [28]

Stretching Modulus Calculation:

- Measure the change in projection length (ΔL) inside the pipette versus applied pressure

- Calculate the stretching modulus (K) using the formula: K = (ΔP × R₀²) / (ΔL × Rp) where R₀ is the initial vesicle radius and Rp is the pipette radius

- Compare functionalized versus control vesicles to quantify polysaccharide-induced softening [28]

AFM Nanomechanics of Bacterial Biofilms

To study the role of capsular polysaccharides in biofilm formation:

Bacterial Strain Preparation: Wild-type and isogenic mutants (e.g., fimbriae-deficient strains) of relevant pathogens such as Klebsiella pneumoniae are cultured under conditions that promote capsule expression [15].

Sample Immobilization: Bacterial cells are chemically immobilized on functionalized glass substrates using poly-L-lysine or specific antibodies to maintain viability while preventing movement during AFM imaging [15].

In Situ Nanomechanical Measurements:

- Perform force mapping over multiple bacterial cells (typically 16×16 or 32×32 grid patterns)

- Use colloidal probes or sharp tips depending on the specific property being measured

- Collect hundreds of force curves across the bacterial surface to capture heterogeneity [15]

Data Correlation: Correlate nanomechanical properties with biofilm formation assays (e.g., static microtiter plate assays) to establish structure-function relationships between capsular organization, adhesion forces, and biofilm formation capacity [15].

Visualization of Mechanical Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Polysaccharide Mechanical Response Pathways. This diagram illustrates the relationship between molecular mechanisms, observable mechanical signatures, and characterization techniques used in polysaccharide nanomechanics studies.

Diagram 2: AFM Force Spectroscopy Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the standardized protocol for AFM-based nanomechanical characterization of polysaccharides, from sample preparation through data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Polysaccharide Nanomechanics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFM Cantilevers | Force detection and application | Soft cantilevers (0.01-0.1 N/m) | Requires precise spring constant calibration via thermal tuning [30] |

| Functionalized Substrates | Sample immobilization | Freshly cleaved mica, poly-L-lysine coated glass | Surface chemistry affects polysaccharide adsorption and conformation [29] [15] |

| Cholesterol-Conjugated Polysaccharides | Membrane functionalization | Chol-CS (Chondroitin Sulfate) | Enables asymmetric incorporation into outer leaflet of lipid bilayers [28] |

| Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs) | Model membrane systems | DOPC (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) GUVs | Formed via electroformation; ideal for micropipette aspiration [28] |

| Fluorescent Labels | Visualization and tracking | FITC-labeled polysaccharides, lipid dyes | Enables confocal microscopy and FRAP measurements [28] |

| Microcapillary/Pipette Systems | Micropipette aspiration | Precision borosilicate glass capillaries | Requires precise pressure control systems for mechanical testing [28] |

The mechanical stability conferred by polysaccharides emerges from distinct biophysical mechanisms that can be quantitatively characterized using AFM nanomechanics and complementary biophysical techniques. Through entanglement networks, cross-linking junctions, helical bundle formations, and membrane interactions, polysaccharides generate identifiable mechanical signatures including sawtooth patterns, force plateaus, and force staircases. The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks presented herein provide researchers with standardized methodologies for investigating these phenomena, particularly in the context of biofilm formation and drug delivery system design. As research in this field advances, correlation of these nanomechanical properties with biological function will continue to reveal new opportunities for therapeutic intervention and biomaterial innovation.

Probing the Nanomechanical World: Advanced AFM Methodologies for Biofilm Analysis

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is arguably the most versatile and powerful microscopy technique for nanoscale analysis, capable of achieving atomic resolution with Ångström-level height accuracy [31]. Unlike optical or electron microscopy, AFM does not use lenses or beam irradiation, and thus does not suffer from limitations in spatial resolution due to diffraction and aberration [32]. This technical guide explores the core principles of AFM, specifically topographical imaging and force spectroscopy, framed within its application to nanomechanics studies of capsular polysaccharides in biofilm research—a field crucial for understanding bacterial pathogenesis and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Fundamental Operating Principles

Core Components and Sensing Mechanism

The fundamental operation of an AFM involves scanning a sample using a sharp tip (with a radius of curvature on the order of nanometers) mounted on a flexible cantilever [33] [32].

- Surface Sensing: As the tip approaches the sample surface, forces including attractive van der Waals and repulsive contact forces cause the cantilever to deflect. This delicate balance enables ultra-precise surface probing [31].

- Detection System: A laser beam reflects off the cantilever onto a position-sensitive photodetector (PSPD). Nanoscale deflections alter the laser's path, allowing the PSPD to track height variations and force interactions [31] [32].

- Imaging Mechanism: By scanning the tip across the sample while maintaining constant tip-sample interaction via a feedback loop, the AFM constructs a 3D topographic map with real-time quantitative data on properties such as adhesion and stiffness [31].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental components and workflow of an AFM system:

Primary Imaging Modes

AFM operates primarily in three modes, each with distinct advantages for different sample types, including delicate biological specimens like bacterial capsules [31] [33].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of AFM Imaging Modes

| Operating Mode | Tip-Sample Interaction | Optimal For | Resolution | Risk of Sample Damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Mode | Constant physical contact [31] | Hard, rigid samples [31] | High (atomic resolution possible) [32] | High [33] |

| Tapping Mode | Intermittent contact (oscillating tip) [31] [33] | Soft, fragile, adhesive samples [31] | High (prevents lateral forces) [31] | Low [31] |

| Non-Contact Mode | No contact (attractive forces sensed) [31] | High-resolution in various environments [31] | Moderate [31] | Very Low [31] |

Force Spectroscopy

Principles and Methodology

Force spectroscopy transforms the AFM from a topographic imager into a sophisticated nanomechanical probe, directly measuring interaction forces between the tip and sample [32]. This is achieved by acquiring force-distance curves, which record the cantilever deflection as a function of the piezoelectric actuator's vertical position [31].

The experimental protocol involves:

- Approach Curve: The tip approaches the sample until contact is established, with repulsive forces causing cantilever bending.

- Retraction Curve: The tip withdraws from the surface, often revealing adhesive interactions through a characteristic "pull-off" event [31].

Analysis of these curves provides quantitative data on mechanical properties including adhesion force, elastic modulus (Young's modulus), and sample deformation [31] [32].

Application to Biofilm and Polysaccharide Research

In biofilm research, force spectroscopy is instrumental for measuring the mechanical properties of bacterial surfaces and their constituent polysaccharides. A key study on Klebsiella pneumoniae used AFM to perform in situ nanomechanical measurements of wild-type and mutant strains, revealing how capsular organization influences bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation [15]. Furthermore, a 2023 study correlated the intrinsic viscosity and electrokinetic properties of various capsular polysaccharides with their antibiofilm activity, measurements made possible by AFM-based force spectroscopy [16].

Table 2: Key Mechanical Properties Measurable via AFM Force Spectroscopy

| Property | Description | Derived From | Significance in Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion Force | Force required to separate tip from sample [31] | Retraction curve "pull-off" event [31] | Quantifies bacterium-surface and bacterium-bacterium interactions [15] |

| Young's Modulus | Measure of sample stiffness/elasticity [32] | Slope of the approach curve in the contact region [31] | Reveals mechanical robustness of bacterial capsules and biofilm matrix [15] [16] |

| Deformation | Degree of sample indentation under load | Difference between piezo movement and tip deflection | Informs on capsule compliance and its role in surface attachment [15] |

Advanced Techniques and Recent Developments

Correlative Microscopy and New Instrumentation

The integration of AFM with other analytical techniques is a powerful trend. Correlative systems combine nanometre topographical information from AFM with optical and spectral chemical information from techniques like fluorescence microscopy, enabling the linking of properties at the nanoscale [34]. New instruments, such as Oxford Instruments Asylum Research's Cypher Vero with Quadrature Phase Differential Interferometry (QPDI) for more accurate tip displacement sensing, are pushing technological barriers, particularly for techniques like Piezoresponse Force Microscopy (PFM) [34].

AI and Data Analysis