Bacterial Foraging Optimization: Theory, Applications, and Advances for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) algorithms, a class of swarm intelligence techniques inspired by Escherichia coli foraging behavior.

Bacterial Foraging Optimization: Theory, Applications, and Advances for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) algorithms, a class of swarm intelligence techniques inspired by Escherichia coli foraging behavior. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore BFO's foundational principles, including its core processes of chemotaxis, swarming, reproduction, and elimination-dispersal. The content details methodological implementations and cutting-edge applications in bioinformatics and healthcare, such as multiple sequence alignment for Alzheimer's disease research and hyperparameter optimization in deep learning for mammogram analysis. We address prevalent challenges like parameter sensitivity and premature convergence, presenting modern solutions from adaptive and hybrid algorithms. Finally, the article offers a rigorous validation and comparative analysis against other established optimization techniques, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for leveraging BFO in complex biomedical optimization problems.

The Biological Blueprint: Understanding Bacterial Foraging Optimization

Swarm Intelligence (SI) is a subfield of Computational Intelligence that designs algorithms inspired by the collective, decentralized behavior of social organisms like ants, birds, and bacteria [1]. These algorithms are particularly effective for solving complex, nonlinear, and high-dimensional optimization problems that challenge traditional methods [2]. SI systems are characterized by their robustness, adaptability, and ability to find good solutions without centralized control.

Among the plethora of SI algorithms, the Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) algorithm holds a unique niche. Introduced by Passino in 2002, it mimics the foraging behavior of the Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacterium [3] [1]. Its core mechanisms simulate how bacteria navigate a chemical environment—moving towards nutrients and away from toxins. While other SI algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) are well-established, BFO offers a distinct approach to optimization, especially in dynamic and noisy environments [2] [4]. However, a critical review of the field notes that many newer bio-inspired algorithms, including some BFO variants, have faced criticism for being primarily metaphor-driven reformulations of existing methods rather than introducing fundamental new search principles [2].

Core Mechanics of the Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm

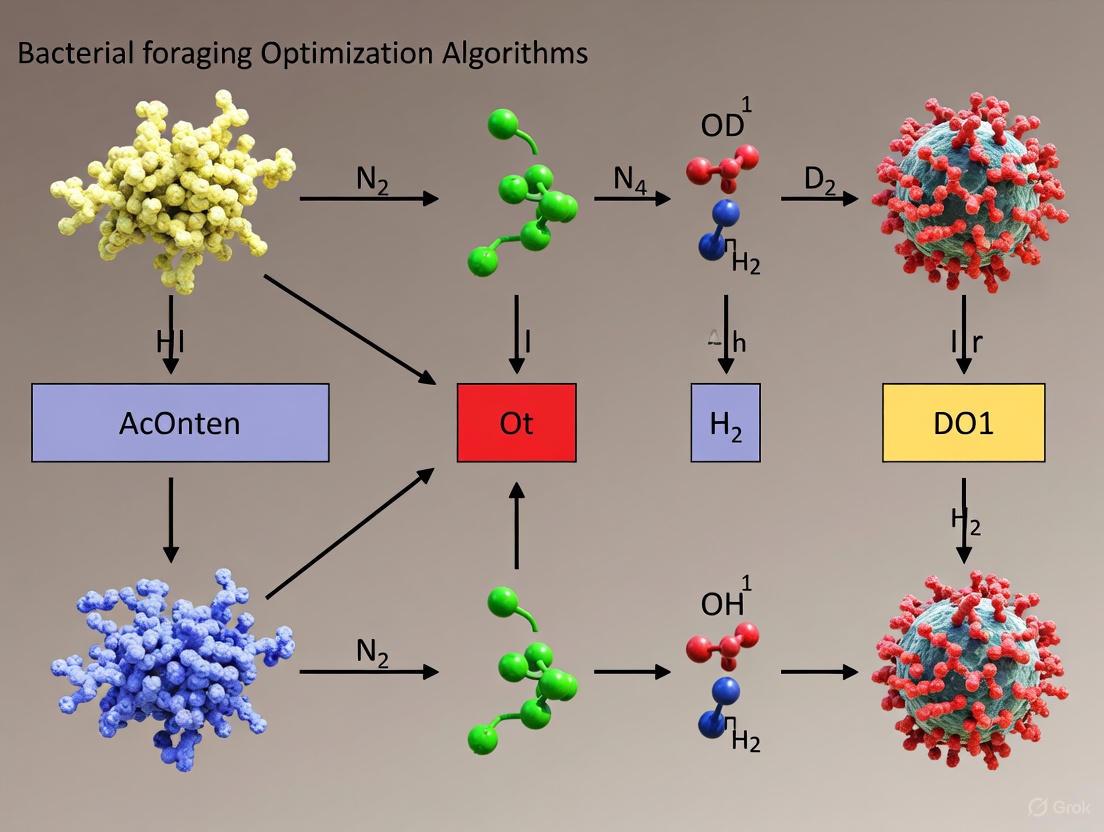

The BFO algorithm's strategy is built upon four principal mechanisms observed in real bacterial foraging: chemotaxis, swarming, reproduction, and elimination-dispersal [1] [4]. The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow and logical relationships between these processes.

The Four Primary Processes of BFO

Chemotaxis: This process simulates the movement of a bacterium through swimming and tumbling via flagella. A bacterium tumbles (changes direction randomly) and then swims in that direction for a number of steps. If it finds a richer nutrient concentration (a better fitness value), it continues swimming in that direction; otherwise, it tumbles again to find a new direction [1] [4]. The movement for bacterium i is mathematically represented as: ( \theta^i(j+1, k, l) = \theta^i(j, k, l) + C(i) \frac{\Delta(i)}{\sqrt{\Delta^T(i)\Delta(i)}} ) where ( \theta^i(j, k, l) ) is the position of bacterium i at chemotactic step j, reproduction step k, and elimination-dispersal step l. ( C(i) ) is the step size, and ( \Delta(i) ) is a random vector on [-1, 1] [3] [1].

Swarming: To model cooperative behavior, bacteria release attractants to signal other bacteria to swarm together. This is implemented by adding a cell-to-cell attraction and repulsion term to the fitness function, which helps the population converge towards promising regions while maintaining some diversity [3] [1] [4]. The additional cost function for swarming is: ( J{cc}(\theta, P(j,k,l)) = \sum{i=1}^{S} [ -d{attract} \exp(-w{attract} \sum{m=1}^{p} (\thetam - \thetam^i)^2) ] + \sum{i=1}^{S} [ h{repelent} \exp(-w{repelent} \sum{m=1}^{p} (\thetam - \theta_m^i)^2) ] ) where S is the total population, p is the number of parameters, and d, h, w are coefficients for attraction and repulsion [3].

Reproduction: After a set number of chemotactic steps, the health of each bacterium is evaluated (as the sum of fitness values over its lifetime). The least healthy half of the population dies, and the healthiest half each split into two identical bacteria in the same location, keeping the population size constant [1] [4].

Elimination-Dispersal: With a small probability, bacteria in a region can be eliminated and randomly dispersed to a new location in the search space. This event helps the algorithm avoid becoming trapped in local optima [1] [4].

Algorithm Parameters and Tuning

The performance of BFO is highly dependent on the careful selection of its parameters. The table below summarizes the key parameters and heuristics for their selection based on the problem complexity [1] [4].

Table 1: Key BFO Algorithm Parameters and Tuning Heuristics

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Selection Heuristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Size | S |

Total number of bacteria in the population. | Larger for complex problems; balance with computational cost. |

| Chemotactic Steps | N_c |

Number of chemotactic steps per reproduction loop. | Large enough for effective space exploration. |

| Swimming Length | N_s |

Maximum number of swims in a profitable direction. | Small to prevent moving too far from promising regions. |

| Reproduction Steps | N_re |

Number of reproduction cycles per elimination-dispersal. | Balance exploration and exploitation. |

| Elimination-Dispersal Events | N_ed |

Number of elimination-dispersal events. | Balance exploration and exploitation. |

| Elimination-Dispersal Probability | P_ed |

Probability of a bacterium being dispersed. | Typically a low value to prevent disrupting convergence. |

| Step Size | C(i) |

Step size for bacterium i during chemotaxis. | Can be adaptive, decreasing over time for finer tuning. |

Experimental Methodology and Benchmarking

To validate the performance of BFO and its variants, researchers employ a standard methodology involving benchmark functions and performance metrics. The following workflow outlines a typical experimental procedure for evaluating BFO.

Standard Benchmarking Protocol

A typical experiment to evaluate a BFO variant, such as the Hybrid Multi-Objective Optimized Bacterial Foraging Algorithm (HMOBFA), follows these steps [3]:

- Select Benchmark Functions: Choose a set of standard multi-objective test functions (e.g., ZDT, DTLZ series) with known properties and Pareto fronts.

- Configure Algorithm Parameters: Set the parameters for HMOBFA and other algorithms used for comparison (e.g., NSGA-II, MOPSO). Parameters for HMOBFA include the size of external and internal archives for the crossover-archive strategy and parameters for the life-cycle optimization strategy [3].

- Execute Multiple Independent Runs: Run each algorithm multiple times on each benchmark function to account for stochastic variations.

- Collect Performance Data: Record key performance metrics throughout the runs.

- Perform Statistical Analysis: Use statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to determine the significance of performance differences between algorithms [5] [3].

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Results

The performance of multi-objective optimizers like HMOBFA is evaluated using metrics that assess the quality of the obtained non-dominated solution set. Key metrics include convergence, diversity, and complexity [3].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Multi-Objective BFO Algorithms

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) | Measures the average distance from the true Pareto front to the obtained solution set. | A lower IGD indicates better convergence and diversity. |

| Hypervolume (HV) | Measures the volume of the objective space covered by the obtained non-dominated solutions. | A higher HV indicates a better and more diverse approximation of the Pareto front. |

| Spread | Evaluates the extent and uniformity of spread of the obtained solutions. | A lower spread value indicates a more uniform distribution of solutions. |

Experimental results from recent studies demonstrate the effectiveness of advanced BFO variants. For example, the HMOBFA algorithm was shown to achieve significant performance enhancement compared to classical multi-objective optimization methods like NSGA-II and MOPSO across several benchmark functions, handling many-objective problems with solid complexity, convergence, and diversity [3]. In another domain, a BFO-based approach for multiple sequence alignment (BFO-GA) was measured against other methods and achieved better statistical significance results on benchmark datasets [5].

For researchers implementing and experimenting with BFO algorithms, the following "toolkit" outlines essential computational resources and components.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for BFO Experimentation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in BFO Research |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Function Suites | Software Library | Provides standardized test problems (e.g., CEC, ZDT, DTLZ) to validate and compare algorithm performance fairly. |

| Multi-objective Performance Metrics | Software Library | Implements calculation of metrics like Hypervolume and IGD to quantitatively assess the quality of results. |

| Crossover-Archive Strategy | Algorithmic Component | Used in hybrids like HMOBFA; an external archive focuses on convergence, while an internal archive maintains diversity [3]. |

| Life-Cycle Optimization Strategy | Algorithmic Component | Allows individuals to switch states periodically to maintain population diversity and avoid redundant local searches [3]. |

| Statistical Testing Software | Tool/Framework | Enables the use of tests like the Wilcoxon Matched-Pair Signed-Rank test to determine the statistical significance of results [5]. |

Applications, Limitations, and Future Directions

Applications in Science and Engineering

BFO's robustness in noisy and dynamic environments makes it suitable for various applications. Key areas include [4]:

- Bioinformatics: BFO has been successfully hybridized with Genetic Algorithms (BFO-GA) for complex tasks like multiple sequence alignment of protein sequences, outperforming several well-known methods [5].

- Medical Imaging: The Bitterling Fish Optimization (BFO) algorithm, a namesake variant, has been applied to detect the optic disc in retinal images with high accuracy, demonstrating potential for automated diagnosis [6].

- Robotics: In swarm robotics, BFO principles are used for path planning, swarm coordination, and obstacle avoidance, enabling decentralized control and adaptive behavior [4].

Critical Limitations and Challenges

Despite its potential, BFO faces several challenges that researchers must consider [1] [4]:

- Parameter Sensitivity: Performance heavily depends on the proper tuning of many parameters (e.g.,

N_c,C(i),P_ed), which can be time-consuming and problem-specific. - Premature Convergence: Like many population-based algorithms, BFO can converge to local optima, particularly in complex, multi-modal fitness landscapes.

- Computational Complexity: The algorithm can be computationally expensive, especially for high-dimensional problems, due to the nested loops for its four processes.

Future Research Directions

The evolution of BFO is likely to focus on overcoming its current limitations [2] [4]:

- Development of Hybrid Algorithms: Combining BFO with other SI or evolutionary algorithms (e.g., PSO, GA) to leverage their complementary strengths and create more robust optimizers [5] [4].

- Adaptive Parameter Control: Designing BFO variants that dynamically adjust their own parameters during the search to reduce the burden of manual tuning and improve performance.

- Multi-objective Optimization: Extending BFO to more effectively handle problems with multiple conflicting objectives, which are common in real-world engineering and design [3].

The Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm (BFOA) represents a significant milestone in the field of bio-inspired computation, directly deriving its core mechanisms from the social foraging strategies of Escherichia coli bacteria. The algorithm computationally formalizes the chemotactic behavior of E. coli cells, which navigate chemical gradients in their environment to locate nutrients and avoid harmful substances [7]. This biological problem-solving capability has been translated into a powerful optimization framework that solves complex, non-gradient optimization problems across diverse domains from engineering to pharmaceutical research [8].

Inspired by the pioneering work of Brenner and others who first analyzed bacterial motility, BFOA mimics the group foraging behavior of E. coli bacteria present in the human intestine [7]. This social foraging behavior embodies a natural optimization process where bacteria seek to maximize energy acquisition per unit time spent foraging [9]. The algorithm's development has enabled researchers to address challenging optimization problems characterized by high dimensionality, non-linearity, and non-differentiability that traditional gradient-based methods struggle to solve efficiently.

Biological Foundations of E. coli Foraging

Experimental Analysis of E. coli Chemotaxis

The fundamental behaviors underlying BFOA originate from rigorous experimental studies of E. coli chemotaxis. When foraging in suboptimal environments, E. coli employs sophisticated predictive regulation strategies that extend beyond simple stimulus-response mechanisms [10]. Research has demonstrated that E. coli can use the appearance of one stimulus as a cue for the likely arrival of a subsequent one, indicating a form of associative anticipatory regulation [10].

Mathematical modeling of this behavior reveals that E. coli optimizes its foraging strategy by balancing the cost of mounting responses against the benefits gained from those responses. The fitness advantage of this predictive capability can be represented as:

[ F = \sum \left( \text{gain from response} - \text{cost of response} \right) ]

where the gain is linearly proportional to the response level at a given time point and is only realized when the target stimulus is present [10]. This biological optimization principle forms the foundational concept behind the computational algorithm.

Quantitative Behavioral Measurements

Experimental studies have quantified key parameters of E. coli foraging behavior that directly inform algorithm development:

Table 1: Experimentally Observed E. coli Foraging Parameters

| Behavioral Parameter | Experimental Measurement | BFOA Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Chemotactic step size | Variable based on nutrient gradient | Step size in parameter space |

| Reproduction rate | Proportional to nutrient accumulation | Population update frequency |

| Elimination-dispersal | Response to poor environments | Random restart mechanism |

| Predictive response delay | Optimal preparation period: 10-30 minutes | Memory incorporation in optimization |

The exploration-exploitation trade-off observed in E. coli foraging has been particularly influential in algorithm design. Studies show that microorganisms initially prioritize exploration of the environment before switching to more exploitatory strategies during subsequent encounters with resources [9]. This same principle is implemented in BFOA to balance global search with local optimization.

Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm: Technical Framework

Core Algorithmic Components

The BFOA formalizes E. coli foraging behavior through four interconnected processes:

Chemotaxis: This process mimics the swimming and tumbling behavior of E. coli through attractant and repellent chemicals. In computational terms, this represents the local search step where bacteria (potential solutions) move in the parameter space [7] [8].

Swarming: Social behavior is implemented through cell-to-cell signaling, creating attractive and repulsive forces that enable group-based optimization [7].

Reproduction: The healthiest bacteria (those finding the most nutrients) split into two identical copies, replacing the least healthy bacteria [7].

Elimination and Dispersal: Bacteria are randomly eliminated and dispersed to new locations with a small probability, preventing premature convergence [8].

Mathematical Formalization

The chemotactic step for bacterium i can be represented as:

[ \theta^{i}(j+1,k,l) = \theta^{i}(j,k,l) + C(i)\frac{\Delta(i)}{\sqrt{\Delta^{T}(i)\Delta(i)}} ]

Where:

- (\theta^{i}(j,k,l)) represents the position of bacterium i at chemotactic step j, reproduction step k, and elimination-dispersal event l

- (C(i)) is the step size

- (\Delta(i)) indicates a random direction vector for tumble behavior [8]

The objective function (J(\theta)) represents the combined effects of attractants and repellents in the environment, with each bacterium attempting to maximize this function during foraging [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Laboratory Analysis of E. coli Foraging Behavior

Protocol 1: Quantitative Assessment of Predictive Foraging

Culture Preparation: Grow E. coli cultures in controlled medium with specific carbon sources (e.g., glycerol as inferior carbon source) [10].

Conditioning Phase: Expose experimental group to metabolically inert artificial inducer (IPTG) to trigger pre-induction of metabolic pathways without energetic gain [10].

Environmental Shift: Add superior carbon source (lactose) to both conditioned and control cultures.

Fitness Measurement: Monitor population size changes in both conditioned and unconditioned cultures after environmental change [10].

Data Analysis: Calculate fitness advantage as population size ratio of conditioned over unconditioned culture after environmental change [10].

Protocol 2: Stress Autoprotection Phenotype Analysis

Baseline Conditions: Maintain E. coli cells at optimal growth temperature.

Conditioning Stimulus: Apply mild, non-lethal temperature elevation to experimental group.

Stress Challenge: Expose both conditioned and control populations to severe heat shock.

Viability Assessment: Measure survival rates across experimental conditions [10].

Computational Implementation of BFOA

Algorithm Implementation Protocol

Parameter Initialization:

- Define population size p, chemotactic steps N_c, swimming length N_s, reproduction steps N_re, elimination-dispersal events N_ed, and probability P_ed [8].

Algorithm Execution:

- For each elimination-dispersal event

- For each reproduction event

- For each chemotactic event

- For each bacterium, compute cost function value

- Apply tumble/swim behavior based on cost function improvement

- End chemotaxis loop

- For each chemotactic event

- Sort bacteria by health and reproduce healthiest half

- For each reproduction event

- End reproduction loop

- With probability P_ed, disperse bacteria to random locations

- End elimination-dispersal loop [8]

- For each elimination-dispersal event

Figure 1: BFOA Algorithm Workflow - The iterative optimization process inspired by E. coli foraging behavior.

BFOA in Pharmaceutical Research: Drug Diffusion Modeling

Hybrid Modeling for Drug Diffusion Prediction

Recent advances in pharmaceutical modeling have successfully integrated BFOA with machine learning techniques to predict drug diffusion in three-dimensional spaces. This approach addresses a critical challenge in drug delivery system design by accurately modeling molecular diffusion, the primary phenomenon controlling drug release rates [8].

Table 2: BFOA-Optimized Model Performance in Drug Diffusion Prediction

| Model Type | R² Score | RMSE | MAE | Optimization Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ε-SVR with BFOA | 0.99777 | 0.02145 | 0.01012 | BFO hyperparameter tuning |

| KRR with BFOA | 0.94296 | 0.08912 | 0.05678 | BFO hyperparameter tuning |

| MLR with BFOA | 0.71692 | 0.20334 | 0.14562 | BFO hyperparameter tuning |

| Standard SVR | 0.93452 | 0.09561 | 0.06234 | Grid search |

The implementation follows a systematic methodology:

Data Generation: Solve mass transfer equations via Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) in a 3D domain to compute concentration distribution [8].

Preprocessing: Remove outliers using isolation forest algorithm and normalize data using min-max scaler [8].

Model Optimization: Utilize BFOA for hyperparameter tuning of regression models including ε-Support Vector Regression (ε-SVR), Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR), and Multi Linear Regression (MLR) [8].

Performance Validation: Evaluate models using metrics including R² score, Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [8].

BFOA in Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

Beyond diffusion modeling, BFOA has been incorporated into hybrid approaches for drug-target interaction prediction. The algorithm's ability to efficiently navigate high-dimensional parameter spaces makes it particularly valuable for feature selection in complex biological datasets [11]. These implementations demonstrate how E. coli inspired optimization directly contributes to accelerating pharmaceutical development pipelines.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Experimental Materials for E. coli Foraging Behavior Research

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli Strains | Wild-type K-12 | Model organism for foraging behavior studies |

| Carbon Sources | Glycerol, Lactose | Inferior/superior nutrient sources for fitness assays |

| Artificial Inducers | IPTG | Metabolically inert pathway inducer for conditioning studies |

| Growth Media | M9 Minimal Medium | Controlled nutrient environment for behavioral assays |

| Temperature Control | Precision water baths | Application of thermal stress protocols |

| Detection Reagents | Metabolic activity assays | Quantification of bacterial response and fitness |

Signaling Pathways and Computational Relationships

The foraging behavior of E. coli that inspires BFOA involves complex signaling pathways that translate environmental cues into behavioral responses:

Figure 2: E. coli Chemotaxis Signaling Pathway - The biological pathway that inspires the BFOA computational framework.

The modeling of E. coli foraging behavior has established a robust bridge between biological observation and computational optimization, yielding the powerful Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm. The continued refinement of BFOA parameters based on experimental biological data promises to enhance the algorithm's performance across increasingly complex pharmaceutical applications, particularly in drug delivery system design and drug-target interaction prediction. As research advances our understanding of bacterial decision-making processes, further bio-inspired optimizations are expected to emerge, creating new opportunities for algorithmic innovation grounded in biological principles.

Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) algorithm, pioneered by Passino in 2002, represents a significant milestone in the domain of swarm intelligence by emulating the foraging behavior of Escherichia coli bacteria [12] [13]. This algorithm provides a robust framework for solving complex optimization problems across various fields, including drug development, medical diagnostics, and robotic systems [14] [15]. The core strength of BFO lies in its four principal mechanisms—chemotaxis, swarming, reproduction, and elimination-dispersal—which work in concert to balance exploration and exploitation in search spaces [1]. For researchers and scientists in computational biology and drug development, understanding these mechanisms is paramount for designing more efficient optimization processes for tasks such as hyperparameter tuning in deep learning models for disease detection [14] or optimizing task allocation in biomedical robotic systems [15]. This technical guide deconstructs these core components, providing a detailed analysis of their operational principles, mathematical formulations, and experimental implementations.

The Core Mechanisms of BFO

Chemotaxis: The Locomotion Engine

The chemotaxis process mimics the fundamental foraging behavior of E. coli bacteria, simulating their movement toward nutrient-rich areas and away from noxious substances through a combination of tumbling and swimming actions [1] [4]. This process forms the primary exploration mechanism of the BFO algorithm, enabling candidate solutions to navigate the search space efficiently.

During chemotaxis, each bacterium undergoes a series of movements characterized by two distinct operations: tumbling, which generates a random direction vector, and swimming, which propels the bacterium in a straight line along that direction [1]. The mathematical representation of this movement for the i-th bacterium is defined as:

[ \thetai^{j+1,k,l} = \thetai^{j,k,l} + C(i) \frac{\Delta(i)}{\sqrt{\Delta(i)^T \Delta(i)}} ]

Where:

- (\theta_i^{j,k,l}) represents the position of bacterium i at chemotactic step j, reproduction step k, and elimination-dispersal step l

- (C(i)) is the chemotactic step size for bacterium i

- (\Delta(i)) is a random vector with elements in the range [-1, 1] that determines the direction of movement after a tumble [1]

The critical parameter governing this process is the step size (C(i)), which directly influences the balance between exploration and exploitation. Research has demonstrated that fixed step sizes often lead to suboptimal performance [16]. Consequently, various adaptive strategies have been proposed, including linear-decreasing Lévy flight strategies that allow for more dynamic movement patterns [16] and segmentation approaches that adjust step sizes based on fitness rankings [17].

Table 1: Chemotaxis Step Size Adaptation Strategies

| Strategy | Mathematical Formulation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear-Decreasing Lévy Flight | (C'(i) = C{min} + \frac{iter{max} - iter{current}}{iter{max}} \times C(i)) where (C(i)) follows Lévy distribution [16] | Balances global exploration and local exploitation; prevents premature convergence | Increased computational complexity due to Lévy distribution calculations |

| Segmentation Strategy | Step size varies based on fitness ranking: largest for worst 20%, smallest for best 20%, medium for middle 60% [17] | Accelerates convergence by assigning larger steps to poorly performing bacteria | May overlook promising regions if segmentation thresholds are set improperly |

| Fitness-Adaptive | (C_{step} = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{J(i,j)}}) where (J(i,j)) is the fitness value [18] | Self-adaptive to search landscape; requires minimal parameter tuning | May overfit to current fitness landscape characteristics |

Swarming: The Collective Intelligence

Swarming introduces social cooperation into the optimization process, modeling the cell-to-cell signaling mechanisms observed in bacterial colonies where individuals release attractants and repellents to communicate [1]. This collective behavior enhances the algorithm's capability to locate global optima by enabling information sharing among the population members.

The mathematical formulation for the swarming effect incorporates both attraction and repulsion mechanisms. The combined cell-to-cell attraction and repelling effect is represented as:

[ J{cc}(\theta, P(j,k,l)) = \sum{i=1}^{S} \left[ -d{attract} \exp(-w{attract} \sum{m=1}^{p} (\thetam - \thetam^i)^2) \right] + \sum{i=1}^{S} \left[ h{repellent} \exp(-w{repellent} \sum{m=1}^{p} (\thetam - \theta_m^i)^2) \right] ]

Where:

- (S) is the total population size

- (p) is the dimension of the search space

- (d{attract}) and (w{attract}) are depth and width coefficients for attractant

- (h{repellent}) and (w{repellent}) are height and width coefficients for repellent [1]

This social component is particularly valuable in multi-modal optimization landscapes, where collaboration helps prevent individual bacteria from becoming trapped in poor local optima. The swarming mechanism has demonstrated significant improvements in optimization performance across various applications, including feature selection for classification problems [18] and training deep learning models for medical image analysis [14].

Reproduction: The Evolutionary Pressure

The reproduction mechanism introduces a selection pressure that mimics the evolutionary principle of "survival of the fittest" [1] [13]. Following a predetermined number of chemotactic steps ((N_c)), the algorithm evaluates the health of each bacterium, which is defined as the accumulated fitness over its chemotactic lifetime:

[ J{health}^i = \sum{j=1}^{N_c+1} J(i,j,k,l) ]

The population is then sorted according to health values in ascending order (for minimization problems). The least healthy bacteria (typically the worst-performing half) are eliminated, while the healthier bacteria (the best-performing half) asexually split into two identical copies that inherit the parent's position [1]. This reproduction process ensures that promising search regions explored by fitter individuals receive increased attention in subsequent iterations.

Stability analysis of the reproduction operator has revealed that under appropriate conditions, this mechanism contributes significantly to the rapid convergence of the bacterial population near optimal solutions [13]. However, researchers must carefully balance the reproduction frequency, as excessive reproduction can lead to premature convergence and loss of population diversity [1].

Elimination-Dispersal: The Diversity Mechanism

The elimination-dispersal event introduces periodic randomization into the search process, modeling real-world scenarios where bacterial populations in a region may face sudden environmental changes or be dispersed to new locations [1]. This operator plays a crucial role in maintaining population diversity and preventing premature convergence to local optima.

In the standard BFO algorithm, each bacterium faces a probability (P{ed}) of being eliminated and subsequently dispersed to a random location within the search space during each elimination-dispersal event [1]. This process occurs (N{ed}) times throughout the algorithm's execution. Research has shown that using a constant probability for all bacteria regardless of their fitness can negatively impact convergence speed, as high-performing individuals near optimal solutions might be unnecessarily dispersed [19].

To address this limitation, improved variants have introduced non-uniform probability distributions. The Poisson Distribution strategy represents one such enhancement, where bacteria are sorted by fitness and dispersal decisions are based on random numbers generated from a Poisson distribution [17]. The probability mass function for Poisson distribution is:

[ P(X=k) = \frac{\lambda^k}{k!} e^{-\lambda}, \quad k=0,1,2,\ldots ]

This approach ensures that poorer-performing bacteria have higher probabilities of dispersal while protecting most high-performing individuals from unnecessary randomization [17].

Table 2: Elimination-Dispersal Probability Strategies

| Strategy | Implementation | Impact on Performance | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Probability | Fixed (P_{ed}) for all bacteria regardless of fitness [1] | Simple to implement but may disperse promising solutions | Basic optimization problems with few local optima |

| Non-Uniform Linear | Probability decreases linearly with improving fitness ranking [19] | Improves convergence speed while maintaining diversity | Medium-complexity problems with moderate multimodality |

| Poisson Distribution | Dispersal based on random numbers from Poisson distribution [17] | Better protection of top-performing bacteria; enhanced convergence | Complex, high-dimensional optimization problems |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard BFO Implementation Protocol

Implementing the Bacterial Foraging Optimization algorithm requires careful configuration of multiple parameters across its nested loop structure. The following protocol outlines the standard implementation procedure:

Initialization Phase:

- Define the problem dimension (p) and search space boundaries

- Set population size (S) based on problem complexity (typically 50-100)

- Initialize bacteria positions randomly within the search space

- Configure algorithm parameters:

- Number of chemotactic steps (Nc): 50-100

- Swimming length (Ns): 4-10

- Number of reproduction steps (Nre): 4-10

- Number of elimination-dispersal events (Ned): 2-5

- Elimination-dispersal probability (P_ed): 0.05-0.2

- Chemotactic step size (C(i)): adaptive or fixed based on search space

Execution Phase:

- For each elimination-dispersal event (l = 1 to Ned):

- For each reproduction step (k = 1 to Nre):

- For each chemotactic step (j = 1 to Nc):

- For each bacterium (i = 1 to S):

- Compute fitness J(i,j,k,l)

- Tumble: Generate random vector Δ(i)

- Move: Update position using chemotaxis equation

- Compute new fitness J(i,j+1,k,l)

- Swim: Continue movement in same direction while fitness improves (up to Ns times)

- Update health accumulation: Jhealth^i = Jhealth^i + J(i,j,k,l)

- For each bacterium (i = 1 to S):

- For each chemotactic step (j = 1 to Nc):

- Reproduction: Sort bacteria by Jhealth, eliminate worst Sr = S/2, duplicate best S_r

- Reset health values for next reproduction cycle

- For each reproduction step (k = 1 to Nre):

- Elimination-Dispersal: For each bacterium, with probability P_ed, disperse to random location

- Check termination criteria (maximum iterations, fitness threshold, etc.) [1]

Advanced BFO Variants

Recent research has developed numerous enhanced BFO variants to address limitations in convergence speed and solution quality:

ACBFO (Adapting Chemotaxis Bacterial Foraging Optimization): This variant incorporates an adapting chemotaxis step updating strategy to increase search flexibility. The chemotaxis step is modified as:

[ C{step} = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{\alpha}{J(i,j)}}, \quad \alpha = (1 - i/S) \times (C{start} - C{end}) + C{end} ]

Additionally, ACBFO integrates a cooperative learning mechanism inspired by PSO: [ C = C{step} + c1 R1 (PBesti - Posi) + c2 R2 (Best - Posi) ] This hybrid approach enhances information sharing between bacteria, significantly improving performance on classification problems [18].

LPCBFO (BFO with Comprehensive Swarm Learning): This variant combines linear-decreasing Lévy flight strategies with comprehensive swarm learning. The Lévy flight step size is calculated as: [ C(i) = \frac{u}{|v|^{1/\beta}}, \quad u \sim N(0, \sigmau^2), \quad v \sim N(0,1) ] with σu defined as: [ \sigma_u = \left[ \frac{\Gamma(1+\beta) \sin(\pi \beta / 2)}{\Gamma((1+\beta)/2) \times \beta \times 2^{(\beta-1)/2}} \right]^{1/\beta} ] The algorithm further incorporates both cooperative learning with the global best bacterium and competitive learning through pairwise competition, significantly enhancing convergence accuracy [16].

PDBFO (BFO with Differential and Poisson Distribution Strategies): This approach integrates differential evolution operators with Poisson Distribution-based elimination-dispersal. After swimming operations, bacteria undergo differential mutation: [ Gi = Pi + F \cdot (R1 - R2) ] where F is an adaptive scaling factor: [ F = 2F0 \cdot e^{1 - \frac{Nc}{N_c + 1 - j}} ] For elimination-dispersal, the Poisson Distribution strategy selectively disperses bacteria based on fitness ranking, preserving high-performing individuals while maintaining population diversity [17].

Visualization of BFO Mechanisms

BFO Algorithm Workflow

Chemotaxis and Swarming Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for BFO Research

| Research Reagent | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fitness Function | Evaluates solution quality; guides optimization direction | Medical: Diagnostic accuracy in cancer detection models [14] |

| Parameter Configurator | Systematically tunes BFO parameters for optimal performance | Adaptive chemotaxis step size controllers [18] [16] |

| Population Initializer | Generates initial bacterial positions in search space | Random uniform distribution within defined bounds [1] |

| Termination Condition Checker | Determines when to stop algorithm execution | Maximum iterations, fitness threshold, or convergence stability [1] |

| Visualization Toolkit | Creates graphs and charts to analyze algorithm behavior | Convergence curves, population diversity plots, search space mapping [12] |

| Statistical Analysis Package | Compares algorithm performance across multiple runs | Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, ANOVA, performance profiling [18] [16] |

| Hybridization Framework | Integrates BFO with other optimization techniques | BFO-PSO hybrids for enhanced global search capability [16] [17] |

Applications in Scientific Research

Medical Diagnostics and Drug Development

BFO algorithms have demonstrated remarkable success in enhancing medical diagnostics, particularly in breast cancer detection using deep learning approaches. Research has shown that BFO-optimized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can significantly improve classification accuracy by automatically tuning hyperparameters such as filter size, number of filters, and hidden layer configurations [14]. In one comprehensive study, BFO-CNN achieved accuracy improvements of 7.62% for VGG19, 9.16% for InceptionV3, and 1.78% for a custom 20-layer CNN model when applied to mammogram analysis from the Digital Database for Screening Mammography (DDSM) [14].

The algorithm's capability to navigate complex, high-dimensional search spaces makes it particularly valuable for optimizing deep learning architectures in drug discovery applications, where it can efficiently identify optimal network configurations that would be infeasible to discover through manual tuning. Furthermore, BFO's robustness to noisy environments aligns well with medical data characteristics, enhancing its applicability to real-world clinical datasets [14].

Data Classification and Feature Selection

In the domain of data classification, enhanced BFO variants have shown superior performance for feature selection tasks. The ACBFO algorithm incorporates an adapting chemotaxis mechanism and feature subset updating strategy that efficiently reduces dimensionality while maintaining classification accuracy [18]. When tested on 12 benchmark datasets, ACBFO outperformed standard BFO, BFOLIW, and Binary PSO in classification accuracy, demonstrating its effectiveness for data preprocessing in scientific research [18].

The algorithm's wrapper-based approach combines the exploration capabilities of BFO with the evaluation power of classifiers like K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), creating a powerful tool for identifying relevant features in high-dimensional biological and chemical data. This application is particularly relevant for drug development professionals working with omics data or chemical compound libraries, where identifying the most predictive features can dramatically reduce computational requirements and improve model interpretability [18].

Healthcare Robotics and Automated Systems

BFO-based optimization has found significant applications in healthcare robotics, particularly in multiple-robot task allocation systems. The Bacterial Foraging Optimization Building Block Distribution (BFOBBD) algorithm dynamically allocates tasks to robots based on utility, interdependence, and computational efficiency [15]. In experimental evaluations, BFOBBD achieved a task allocation time of just 4.23 seconds, significantly outperforming FA-POWERSET-MART (20.19 seconds) and FA-QABC-MART (5.26 seconds) [15].

This capability is crucial for developing efficient robotic systems for drug screening, laboratory automation, and patient care, where multiple robots must coordinate to execute complex tasks. The BFO framework's ability to handle dynamic dependencies and heterogeneous robot capabilities makes it particularly suited for real-world healthcare applications where operational requirements frequently change [15].

The Bacterial Foraging Optimization algorithm, through its four core mechanisms of chemotaxis, swarming, reproduction, and elimination-dispersal, provides a robust framework for solving complex optimization problems in scientific research and drug development. The continuous evolution of BFO variants—incorporating adaptive step sizes, hybrid learning strategies, and intelligent dispersal mechanisms—has significantly enhanced the algorithm's performance across diverse applications from medical diagnostics to healthcare robotics. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these core mechanisms enables not only the effective application of existing BFO implementations but also the development of novel variants tailored to specific scientific challenges. As optimization requirements grow increasingly complex in pharmaceutical research and medical technology, the principles of bacterial foraging offer a biologically-inspired pathway to more efficient and effective computational solutions.

Key Parameters and Their Influence on Algorithm Behavior

Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm (BFOA) is a nature-inspired metaheuristic that mimics the foraging behavior of E. coli bacteria to solve complex optimization problems. Its robustness and adaptability have led to successful applications across various domains, including bioinformatics, healthcare robotics, and medical imaging [20] [15] [14]. The algorithm's performance is highly dependent on the precise configuration of its core parameters, which govern the processes of chemotaxis, swarming, reproduction, and elimination-dispersal [21]. This guide provides an in-depth analysis of these key parameters, their influence on algorithm behavior, and detailed experimental methodologies for researchers, with a particular focus on applications relevant to drug development and biomedical research.

Core BFOA Parameters and Their Technical Specifications

The behavior and performance of the BFOA are controlled by a set of core parameters that guide the search process. Understanding and tuning these parameters is critical for achieving optimal performance in specific applications, such as multiple sequence alignment for drug discovery or hyperparameter optimization in medical deep learning models.

Table 1: Core BFOA Parameters and Their Influence on Algorithm Behavior

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Technical Definition | Influence on Algorithm Behavior | Typical Value Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotaxis | Step Size | Distance a bacterium moves during a tumble or run [20]. | Larger values promote exploration but risk overshooting; smaller values favor local exploitation [14]. | Application-dependent; often set via experimentation. |

Number of Chemotactic Steps (Nc) |

Maximum iterations for chemotaxis in each reproduction loop [20]. | Higher values allow more thorough local search but increase computational cost [20]. | 10-100 (varies with problem complexity) [20]. | |

| Swarming | Attraction Depth (d_attr) |

Magnitude of attractive cell-to-cell signaling [20]. | Promotes swarm formation, accelerating convergence but potentially trapping bacteria in local optima [20]. | 0.1-0.5 (dimensionless) [20]. |

Attraction Width (w_attr) |

Spread of the attractive signal [20]. | Wider attraction encourages broader swarm formation [20]. | 0.1-0.5 (dimensionless) [20]. | |

Repulsion Height (h_repel) |

Magnitude of repulsive cell-to-cell signaling [20]. | Maintains population diversity, preventing premature convergence [20]. | 0.01-0.2 (dimensionless) [20]. | |

Repulsion Width (w_repel) |

Spread of the repulsive signal [20]. | Wider repulsion discourages overcrowding [20]. | 1-10 (dimensionless) [20]. | |

| Reproduction | Reproduction Steps (Nre) |

Number of reproduction cycles per generation [20]. | Higher values allow more fitness-based refinement but increase runtime [20]. | 4-10 [20]. |

| Elimination & Dispersal | Elimination Probability (Ped) |

Likelihood a bacterium is dispersed to a random location [20]. | Key for escaping local optima; high values can disrupt convergence [14]. | 0.05-0.25 [20] [14]. |

Number of Elimination Events (Ned) |

How often elimination-dispersal occurs [20]. | Increases non-linearity and exploration capability [20]. | 2-5 [20]. | |

| Population | Population Size (S) |

Number of bacteria in the population [20]. | Larger populations explore more space but increase computational cost per iteration [14]. | 20-100 [20]. |

The swarming behavior is mathematically modeled by a function that combines attractive and repulsive effects between bacteria. The total cell-to-cell attraction and repulsion effect for bacterium k is given by:

( J{cc}(\theta, P(j,k,l)) = \sum{i=1}^{S} \left[ -d{\text{attr}} \exp\left(-w{\text{attr}} \sum{m=1}^{p} (\thetam^k - \thetam^i)^2\right) + h{\text{repel}} \exp\left(-w{\text{repel}} \sum{m=1}^{p} (\thetam^k - \thetam^i)^2\right) \right] )

Where S is the population size, P is the number of parameters to be optimized, and θ represents the position of a bacterium [20]. This equation dictates how bacteria communicate and form groups, which is fundamental to guiding the population toward promising regions in the search space.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: BFOA for Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA)

Objective: To optimize the alignment of biological sequences (DNA, RNA, proteins) for phylogenetic analysis and protein structure prediction, which are foundational activities in drug development [20] [5].

Methodology:

- Initialization: A population of bacteria is initialized, where each bacterium represents a candidate multiple sequence alignment. Sequences are loaded from FASTA files using a dedicated reader class [20].

- Fitness Evaluation: The fitness of each alignment is evaluated using a scoring function. This often involves constructing a position weight matrix and calculating metrics like:

- Parallel Optimization: The core BFOA steps (chemotaxis, swarming, reproduction, elimination-dispersal) are executed. A parallel implementation using multiprocessing libraries is recommended to handle the computational intensity, where shared lists (

manager.list()) manage alignment scores and bacterium interactions [20]. - Termination: The algorithm runs for a predefined number of iterations or until convergence, outputting the optimal alignment matrix [20].

Key Parameters for MSA: The parameters d_attr, w_attr, h_repel, and w_repel are critical as they control the swarming behavior that helps refine the alignment by sharing information about promising regions in the search space [20].

Protocol 2: BFOA for Hyperparameter Optimization in Deep Learning

Objective: To automate the tuning of hyperparameters (e.g., filter size, number of filters, hidden layers) in Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for medical image analysis, such as breast cancer detection from mammograms [14].

Methodology:

- Problem Formulation: Each bacterium represents a vector of CNN hyperparameters.

- Fitness Evaluation: The fitness is the CNN's performance (e.g., classification accuracy on a validation set) after being trained with the hyperparameters encoded by the bacterium. The Digital Database for Screening Mammography (DDSM) is a commonly used dataset [14].

- Optimization Process: The BFOA searches the hyperparameter space. The elimination-dispersal probability (

Ped) is particularly important here to avoid premature convergence on suboptimal hyperparameter sets [14]. - Validation: The best-performing bacterium (hyperparameter set) is used to train a final model evaluated on a held-out test set.

Key Parameters for DL: Chemotaxis step size and number of steps (Nc) must be balanced to thoroughly explore the complex, high-dimensional search space of CNN architectures without prohibitive computational cost [14].

Protocol 3: BFOA for Dynamic Task Allocation in Healthcare Robotics

Objective: To optimally assign tasks to multiple heterogeneous robots in healthcare environments (Ambient Assisted Living), minimizing task allocation time and computational overhead [15].

Methodology:

- Modeling: A model is constructed with multiple tasks, multiple robots, and multiple resources. Each bacterium represents a potential task allocation scheme [15].

- Fitness Function: The objective is to minimize task allocation time while considering robot utility, task interdependence, and computational costs [15].

- Algorithm Execution: The BFOA's chemotaxis and reproduction steps refine the allocation. The improved algorithm (BFOBBD) incorporates probabilistic modeling and multivariate factorization for efficiency [15].

- Performance Metric: The key metric is total task allocation time, where BFOBBD has been shown to reduce time to 4.23 seconds, outperforming other methods [15].

Key Parameters for Robotics: The population size (S) and reproduction steps (Nre) should be configured to ensure a diverse set of allocation strategies are efficiently evaluated in a dynamic environment [15].

Visualizing Workflows and Parameter Interactions

Figure 1. High-level workflow of the Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm (BFOA), illustrating the sequence and iteration of its core processes.

Figure 2. Interaction network of key BFOA parameters and their primary influence on algorithm behavior, showing the trade-off between convergence, diversity, and search scope.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Computational Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools for BFOA Experimentation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in BFOA Research | Example Sources/Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Sequence Data | Dataset | Provides benchmark sequences for developing and testing MSA algorithms. | NCBI Database, BAliBASE, Prefab, SABmark, Oxbench [20] [5] |

| Medical Imaging Data | Dataset | Serves as input for training and validating deep learning models whose hyperparameters are optimized by BFOA. | DDSM (Digital Database for Screening Mammography), MIAS, INbreast [14] |

| Python with Multiprocessing | Software Library | Core platform for implementing parallel BFOA; essential for handling computational complexity. | multiprocessing, numpy libraries [20] |

| BLOSUM/PAM Matrices | Scoring Matrix | Provides log-odds scores for amino acid substitutions, used in the fitness function for biological sequence alignment. | BLOSUM62, BLOSUM80, PAM100, PAM200 [20] [5] |

| FASTA File Reader | Software Tool | Parses and loads genetic or protein sequences from FASTA files into the algorithm. | Custom class in Python [20] |

| MATLAB | Software Platform | Used for implementing BFOA in engineering applications such as resource allocation in communication networks. | MATLAB R2020a+ [22] |

Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) is a nature-inspired algorithm that mathematically models the foraging behavior of Escherichia coli bacteria to solve complex optimization problems. Proposed by Passino, it translates biological processes into a robust computational framework for navigating high-dimensional, multi-modal search spaces where traditional optimization methods often fail [16]. The algorithm operates on the principle that natural selection tends to eliminate animals with poor foraging strategies and favor those with successful strategies for locating, capturing, and consuming food [4].

In the context of complex optimization, BFO offers distinct advantages due to its inherent parallelism, multiple cooperative behaviors, and built-in mechanisms for escaping local optima. Unlike gradient-based methods or simpler evolutionary algorithms, BFO simultaneously employs several bio-inspired processes—chemotaxis, swarming, reproduction, and elimination-dispersal—to balance exploration of the search space with exploitation of promising regions [4] [3]. This multi-modal approach makes it particularly suitable for real-world optimization challenges in fields ranging drug discovery to robotics, where objective functions may be non-differentiable, noisy, or possess numerous local minima.

Core Biological Mechanisms and Their Mathematical Formulations

The BFO algorithm derives its problem-solving capabilities from four principal biological processes, each mapped to a specific mathematical operation for optimization purposes.

Chemotaxis: The Core Search Mechanism

Chemotaxis implements the biased random walk of bacteria as they navigate chemical gradients in their environment. This process combines "tumbling" (random directional changes) and "swimming" (persistent movement in favorable directions) to explore the solution space [4] [16].

The position update for a bacterium during chemotaxis is represented as:

Where:

θi(j,k,l)represents the position of bacteriumiat chemotaxis stepj, reproduction stepk, and elimination-dispersal steplC(i)is the step size for bacteriumiΔ(i)is a random vector on [-1, 1] that determines the direction of movement after a tumble [16]

This chemotactic process enables BFO to maintain a balance between exploration (through random tumbling) and exploitation (through continued swimming in nutrient-rich directions) [4].

Swarming: Collective Intelligence Through Social Cooperation

Swarming embodies the self-organized collective behavior of bacterial colonies, where individuals communicate via attractant and repellent signals to form structured patterns. This social component allows the population to leverage group intelligence rather than operating as independent searchers [4] [3].

The cell-to-cell signaling effect is mathematically modeled as:

Where:

d_attrandw_attrare the depth and width of the attractant signalh_repelandw_repelare the height and width of the repellent signalSis the total population sizepis the number of parameters to be optimized [3]

This swarming effect creates emergent behavior where bacteria attract each other to form groups but maintain minimal distance to prevent overcrowding, effectively enabling the population to collectively climb nutrient gradients [4].

Reproduction: Survival of the Fittest

Reproduction implements natural selection by eliminating the least healthy bacteria and allowing the healthiest to split into two identical copies. This selective pressure progressively improves the overall fitness of the population over successive generations [4] [16].

The health of a bacterium is calculated as:

Where:

J(i,j,k,l)is the cost at each chemotactic stepN_cis the number of chemotactic steps [16]

The reproduction process ensures that beneficial foraging strategies are preserved and amplified while poor strategies are eliminated from the population [4].

Elimination and Dispersal: Maintaining Population Diversity

Elimination-dispersal events periodically randomly relocate a subset of bacteria within the search space. This mechanism introduces stochasticity that helps the algorithm escape local optima and explore new regions that might contain better solutions [4] [16].

These events occur with a fixed probability P_ed, typically set to a low value (e.g., 0.25) to balance the introduction of new exploration points without disrupting productive search patterns [16]. This process is particularly valuable in dynamic environments or when dealing with highly multi-modal functions where getting trapped in local optima is a significant risk [3].

BFO Workflow and Algorithmic Process

The complete BFO algorithm integrates these four mechanisms into a cohesive optimization process. The flowchart below illustrates the hierarchical structure and sequence of operations.

Figure 1: BFO Algorithm Workflow illustrating the nested loops of chemotaxis, reproduction, and elimination-dispersal processes.

The algorithm progresses through hierarchically nested loops, with the innermost chemotaxis loop performing local searches, the reproduction loop improving population quality, and the outermost elimination-dispersal loop maintaining global diversity [4] [16]. This structure allows BFO to efficiently allocate computational resources across different aspects of the optimization process.

Comparative Performance Analysis

BFO's effectiveness stems from its unique combination of mechanisms, which provide distinct advantages over other optimization approaches in specific problem domains.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance comparison of BFO variants against other optimization algorithms across different applications

| Algorithm | Application Domain | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPCBFO [16] | High-dimensional function optimization (30 dimensions) | Convergence accuracy, Optimization capability | Superior to 5 other algorithms on 6 benchmark functions |

| BFO-CNN [14] | Breast cancer detection from mammography | Classification accuracy | Accuracy improvements of 7.62% (VGG19), 9.16% (InceptionV3), 1.78% (Custom CNN) |

| BFOBBD [15] | Multi-robot task allocation in healthcare | Task allocation time | 4.23 seconds vs. 20.19s (FA-POWERSET-MART) and 5.26s (FA-QABC-MART) |

| IBFO [23] | Emergency resource scheduling | Convergence accuracy, Speed | Improved convergence accuracy and faster speed vs. PSO and standard GA |

| HMOBFA [3] | Many-objective optimization (3+ objectives) | Diversity, Convergence, Complexity | Significant performance enhancement vs. classical multi-objective methods |

Advantages Over Other Swarm Intelligence Algorithms

BFO demonstrates distinct characteristics when compared to other popular swarm intelligence algorithms:

Versus Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): While PSO may converge faster in some scenarios, BFO typically exhibits superior performance in dynamic environments and multi-modal fitness landscapes due to its elimination-dispersal mechanism [4]. The BFO reproduction phase provides a stronger selection pressure than PSO's personal-best/global-best update rules.

Versus Genetic Algorithms (GA): BFO generally converges more rapidly than GA for continuous optimization problems, as its chemotaxis operator provides more efficient local searching compared to GA's mutation operator [23]. However, GA may maintain more diverse solutions through crossover operations.

Versus Ant Colony Optimization (ACO): BFO is better suited for continuous optimization problems, while ACO excels primarily in discrete optimization domains such as pathfinding and scheduling [4].

The key differentiator for BFO is its multiple coordinated mechanisms operating at different time scales, allowing it to maintain exploration-exploitation balance throughout the optimization process more effectively than algorithms with simpler update rules [16] [3].

Advanced BFO Variants and Hybrid Approaches

Standard BFO has limitations, including sensitivity to parameter settings and potential premature convergence. Researchers have developed numerous enhanced variants to address these challenges.

Adaptive BFO Algorithms

Adaptive BFO variants dynamically adjust algorithm parameters based on search progress:

Linear-decreasing Lévy flight strategy: Replaces fixed step sizes with a decreasing function based on Lévy distribution, balancing global exploration and local exploitation [16]. The step size updates as:

Where

C(i)follows Lévy distribution [16].Comprehensive swarm learning: Integrates cooperative communication with the global best individual and competitive learning mechanisms to improve convergence accuracy [16].

Multi-Objective and Hybrid Approaches

For complex problems with multiple conflicting objectives, specialized BFO variants have been developed:

Hybrid Multi-Objective BFO (HMOBFA): Combines crossover-archive strategy and life-cycle optimization to handle problems with three or more objectives [3]. This approach maintains separate external and internal archives focused on diversity and convergence respectively.

BFO-PSO hybrids: Leverage PSO's social learning mechanism while retaining BFO's chemotactic movements, enhancing global search capability [4] [16].

BFO-GA hybrids: Incorporate evolutionary operators like crossover and mutation to improve diversity maintenance while preserving BFO's local search strength [4].

Application Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Successful implementation of BFO for complex optimization requires careful attention to parameter tuning, constraint handling, and problem formulation.

Experimental Protocol for Biomedical Applications

The following protocol outlines the successful application of BFO to hyperparameter optimization in deep learning models for medical imaging, as demonstrated in breast cancer detection research [14]:

Problem Formulation:

- Define the optimization objective (e.g., maximize mammography classification accuracy)

- Identify tunable hyperparameters (filter sizes, number of filters, hidden layers)

- Establish constraints (computational budget, memory limitations)

BFO Parameter Initialization:

- Population size (S): Typically 50-100 bacteria

- Chemotactic steps (N_c): 50-100 iterations

- Reproduction steps (N_re): 10-25 generations

- Elimination-dispersal steps (N_ed): 5-15 events

- Swim length (N_s): 4-10 steps

- Step sizes (C): Adaptive or fixed based on problem scale

- Elimination probability (P_ed): 0.1-0.25

Fitness Evaluation:

- For CNN optimization: Train model with candidate hyperparameters

- Evaluate on validation set to compute accuracy

- Use cross-validation to prevent overfitting

Constraint Handling:

- Apply penalty functions for violated constraints

- Use feasibility rules for selection operations

- Implement boundary checks during position updates

Termination Criteria:

- Maximum computation time or function evaluations

- Convergence threshold (minimal improvement over successive generations)

- Target fitness value achievement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key computational components and their functions in BFO implementation

| Component | Function in BFO Algorithm | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Population Initialization | Generates initial bacterial positions in search space | Should cover diverse regions; random or Latin Hypercube sampling |

| Cost Function Evaluator | Computes fitness of each bacterium | Most computationally intensive; often requires parallelization |

| Chemotaxis Step Controller | Manages tumbling and swimming behaviors | Step size critically impacts exploration-exploitation balance |

| Swarming Effect Calculator | Computes cell-to-cell attractant/repellent effects | Parameters dattr, wattr, hrepel, wrepel influence swarm cohesion |

| Reproduction Operator | Eliminates least fit bacteria, splits healthiest | Maintains constant population size; implements elitism |

| Elimination-Dispersal Module | Randomly relocates subset of population | Probability P_ed controls exploration intensity |

| Convergence Monitor | Tracks algorithm progress and termination criteria | Multiple metrics: best fitness, population diversity, stagnation count |

Bacterial Foraging Optimization offers a theoretically grounded and empirically validated approach to complex optimization challenges. Its biological foundation provides a robust framework with multiple coordinated mechanisms that effectively balance exploration and exploitation across diverse problem domains. The algorithm's suitability for complex optimization stems from its inherent parallelism, social cooperation through swarming, quality refinement via reproduction, and diversity maintenance through elimination-dispersal events.

For researchers and drug development professionals, BFO presents particular advantages in handling noisy, non-differentiable objective functions common in biomedical applications, from hyperparameter optimization in deep learning models to drug discovery and protein sequence alignment [14] [24]. The continued development of adaptive and hybrid variants further enhances BFO's applicability to increasingly complex optimization challenges in scientific computing and pharmaceutical research.

As optimization problems in drug development grow in complexity and scale, BFO's bio-inspired approach offers a powerful paradigm for navigating high-dimensional search spaces where traditional methods encounter limitations. The algorithm's flexible architecture and proven performance across diverse applications position it as a valuable tool in the computational researcher's arsenal.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing BFO in Bioinformatics and Drug Discovery

Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) is a robust, nature-inspired algorithm that mimics the foraging behavior of Escherichia coli bacteria. Its significance lies in its ability to efficiently, adaptively, and robustly solve complex optimization problems, often outperforming other nature-inspired algorithms [20]. Within the broader context of bacterial foraging optimization algorithm research, this guide provides a structured framework for implementing BFO, detailing its core procedures and critical data structures. The BFO algorithm is particularly valuable for researchers and scientists tackling NP-complete problems in domains such as bioinformatics and drug development, including challenging tasks like multiple sequence alignment and protein structure prediction [20] [7]. This document serves as a foundational reference for implementing BFO in these computationally intensive fields.

Core BFO Algorithm: Processes and Pseudocode

The BFO algorithm is built upon four principal optimization steps that govern the behavior of the simulated bacterial population: Chemotaxis, Swarming, Reproduction, and Elimination & Dispersal [20] [16]. The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow and logical relationships between these core processes.

Detailed Process Breakdown and Pseudocode

The pseudocode below integrates the core processes, with a particular emphasis on the swarming behavior that enables cooperative search.

The swarming effect implemented in Line 7 is a critical differentiator of BFO, modeled by the function J_cc(θ^i, P) [20]. This function simulates cell-to-cell communication, where bacteria release attractants and repellents to form structured groups. The parameters d_attr and w_attr control the depth and width of the attractive signal, while h_repel and w_repel govern the repulsive effects, ensuring population diversity and preventing premature convergence.

Critical Data Structures

Efficient implementation of the BFO algorithm relies on well-designed data structures to represent the population and manage the algorithm's state.

Bacterial Population Representation

The entire population and its state can be managed using the following core structures:

Bacterium Object:

position: Afloat[]orList<Float>representing the bacterium's coordinates in the solution space.health: Afloatstoring the accumulated cost over a chemotactic lifetime (J_health^i).current_cost: Afloatstoring the cost at the current position, including swarming effects.

Population Management:

population: AList<Bacterium>containing all individuals in the current generation.parameters: Astructorclassholding algorithm parameters (S,Nc,Ns,Nre,Ned,Ped).swarming_coefficients: Astructcontaining the values ford_attr,w_attr,h_repel,w_repel.

Data Structures for Parallel BFO

For parallel implementations, as described in the multiple sequence alignment application [20], additional shared data structures are required:

shared_cost_table: A thread-safe structure (e.g., a synchronizedHashMap) storing evaluation results for quick lookup.task_queue: A queue for distributing chemotactic steps across multiple processors.shared_best_solution: An atomic reference or synchronized variable to track the global best solution across threads.

Experimental Parameters and Performance

Successful application of BFO requires careful parameter selection. The following tables summarize parameter settings and performance metrics from recent research, providing a benchmark for implementation.

Table 1: BFO Parameter Settings from Literature

| Parameter | Description | Typical Range / Value | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| S | Population Size | 50 - 100 | General Optimization [20] |

| Nc | Chemotaxis Steps | 50 - 100 | General Optimization [20] |

| Ns | Swim Length | 4 - 10 | General Optimization [20] |

| Nre | Reproduction Steps | 4 - 10 | General Optimization [20] |

| Ned | Elimination-Dispersal Events | 2 - 5 | General Optimization [20] |

| Ped | Elimination Probability | 0.1 - 0.25 | General Optimization [20] |

| C^i | Run Length | Linear-decreasing Lévy flight [16] | Function Optimization |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of BFO Variants

| Algorithm | Application Context | Performance Metrics | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard BFO | Multiple Sequence Alignment | Consistent efficiency in 30-run scheme [20] | Baseline performance |

| BFO with Gap Deletion | Multiple Sequence Alignment | Increased function evaluations, excessive time [20] | Specialized handling |

| LPCBFO | Benchmark Function Optimization | Superior to 5 other algorithms on 6 functions [16] | Linear-decreasing Lévy flight strategy |

| BFO-CNN | Breast Cancer Detection | Accuracy improvement of 1.78-9.16% over state-of-the-art [14] | Hyperparameter optimization for CNN |

| BFOBBD | Multi-Robot Task Allocation | Task allocation time: 4.23s [15] | Dynamic allocation in healthcare robotics |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

To ensure reproducible results, the following section outlines a standardized experimental protocol for implementing and testing BFO algorithms, drawing from methodologies successfully applied in recent research.

Implementation Setup for Multiple Sequence Alignment

For bioinformatics applications like Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA), the following setup is recommended based on published research [20]:

- Data Preparation: Collect homologous genetic or protein sequences from databases like NCBI. For convergence analysis, use standardized sets such as those related to Alzheimer's disease across various species.

- Algorithm Initialization: Implement the BFO class in Python 3.12+, importing necessary libraries (

multiprocessing,numpy,copy). Initialize the population of bacteria by loading genetic sequences into a list structure. - Fitness Evaluation: Implement a parallel BLOSUM-based evaluation method. Construct a list of every amino acid or DNA pair from each alignment matrix and perform logarithmic scoring to distinguish biologically plausible substitutions.

- Parallelization Strategy: Use the

Managerclass from themultiprocessinglibrary to create shared lists (manager.list()) that can be modified by multiple processes for:- Alignment scores (

blosumScore) - Attraction and repulsion forces (

tablaAtract,tablaRepel) - Fitness evaluations (

tablaFitness) - List of amino acid pairs (

granListaPares)

- Alignment scores (

- Execution and Analysis: Execute a 30-run scheme for statistical significance. Compare results using t-tests and Mann-Whitney tests focusing on fitness, execution time, and number of function evaluations.

Workflow for Protein Structure Prediction

For protein structure prediction using the hydrophobic-polar (HP) model on 3D FCC lattice [7]:

- Problem Formulation: Transform the protein sequence into a simplified representation where amino acids are classified as hydrophobic (H) or polar (P).

- Energy Model: Implement the HP energy model where the objective is to find the conformation with minimal energy, favoring contacts between H residues.

- Conformation Representation: Develop data structures to represent protein conformations on the FCC lattice, ensuring self-avoiding walks.

- BFO Adaptation: Modify the chemotaxis step to explore valid conformational changes. The cost function should calculate the energy based on H-H contacts.

- Validation: Compare obtained energy values with lower bound free energy (LB-FE) benchmarks and compute Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) against known structures.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for a BFO-based bioinformatics application, such as protein structure prediction or multiple sequence alignment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational tools and resources essential for implementing BFO in bioinformatics and drug development research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Sources / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Datasets | Provide homologous sequences for alignment convergence analysis | NCBI Database, Alzheimer's disease-related protein sets [20] |

| Mammogram Datasets | Benchmark for medical imaging applications of BFO | Digital Database for Screening Mammography (DDSM), MIAS, INbreast [14] |

| BLOSUM Matrices | Logarithmic odds scores for amino acid substitutions in MSA | BLOSUM series matrices for fitness evaluation [20] |

| HP Model Framework | Simplified protein folding simulation environment | 3D Face-Centered Cubic (FCC) Lattice implementation [7] |

| Parallel Computing Framework | Enable efficient multiprocessing for population evaluation | Python multiprocessing library, Manager class for shared lists [20] |

| BFO-Optimized CNN | Enhanced deep learning architecture for medical image analysis | Custom CNN with BFO-tuned hyperparameters (filter size, layer count) [14] |

Solving the Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Problem for Genomic and Protein Sequences

Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) is a fundamental pillar in bioinformatics, enabling the comparison and analysis of multiple biological sequences (DNA, RNA, or proteins) simultaneously to uncover critical information about their function, evolution, and molecular structure [20]. The process involves identifying homologous positions across sequences by inserting gaps (representing insertions or deletions) to maximize overall similarity [25]. The reliability of MSA results directly determines the credibility of downstream biological conclusions, influencing applications ranging from phylogenetic tree construction and conserved domain identification to drug target discovery [26].

The core challenge stems from MSA being an NP-hard problem, meaning finding the exact optimal alignment becomes computationally intractable as the number and length of sequences increase [26] [20]. This complexity arises because the number of possible alignments grows exponentially with sequence count and length, compounded by biological realities like sequence variability, experimental errors, and large-scale genomic rearrangements [26] [27]. Consequently, researchers must often rely on heuristic strategies that balance efficiency with accuracy.

The Computational Challenge of MSA and Conventional Approaches

The MSA problem can be formally described as follows: given a set of n sequences S = {s₁, s₂, ..., sₙ}, each with length lᵢ, the goal is to find an alignment matrix A of dimensions n × m (where m is the final alignment length) that maximizes the total similarity score across all sequences [20]. The most common scoring method is the Sum-of-Pairs (SP) score, which sums the alignment scores for every possible pair of sequences within the multiple alignment [20]. The computational complexity of this problem is O(lⁿ), where l is the average sequence length, confirming its NP-complete nature [20].

Classical Alignment Strategies

Traditional MSA methods can be broadly categorized into several algorithmic approaches:

Progressive Alignment: This widely used approach (employed by tools like CLUSTAL Omega, MUSCLE, and MAFFT) first performs global pairwise alignments of all sequences to construct a guide tree representing sequence relationships [25]. The algorithm then progressively aligns sequences according to the tree's branching order, starting with the most similar pairs [25]. While efficient, this "once a gap, always a gap" heuristic can propagate early alignment errors [26].

Iterative Methods: Algorithms like MUSCLE use iterative refinement to overcome limitations of progressive alignment. They begin with a suboptimal alignment and repeatedly modify it to improve the overall score, often achieving better accuracy at higher computational cost [25].