Chemical Force Microscopy: Probing Microbial Surface Properties for Drug Development and Biomedical Research

Chemical Force Microscopy (CFM) has emerged as a powerful technique in microbiological research, enabling the nanoscale mapping of chemical and physical properties of microbial surfaces under physiological conditions.

Chemical Force Microscopy: Probing Microbial Surface Properties for Drug Development and Biomedical Research

Abstract

Chemical Force Microscopy (CFM) has emerged as a powerful technique in microbiological research, enabling the nanoscale mapping of chemical and physical properties of microbial surfaces under physiological conditions. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of CFM, detailed methodologies for probing microbial cells, and advanced applications in antimicrobial resistance and biofilm studies. It further addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance data reproducibility and discusses the validation of CFM findings through complementary techniques. By integrating the latest research, this review highlights how CFM-derived insights into microbial surface heterogeneity, adhesion, and mechanics are informing the development of novel therapeutic strategies and diagnostic tools.

Understanding Chemical Force Microscopy: Principles and Microbial Surface Fundamentals

Core Principles of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Chemical Force Microscopy (CFM)

Fundamental Principles and Operating Modes

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Fundamentals

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a powerful microscopy technique for nanoscale analysis, capable of achieving atomic resolution with Ångström-level height accuracy [1]. AFM operates by scanning a sharp tip, mounted on a flexible cantilever, across a sample surface. The interaction forces between the tip and the sample cause the cantilever to bend, and this deflection is detected by a laser beam reflected off the cantilever onto a position-sensitive photodetector (PSPD) [1] [2]. A feedback loop maintains a constant tip-sample interaction during scanning, enabling the construction of a three-dimensional topographic map of the surface [1].

The key components of a typical AFM setup include [3] [4]:

- A sharp probe tip (with a radius of curvature on the order of nanometers)

- A flexible cantilever that acts as a spring

- A laser and a position-sensitive photodetector (PSPD) to measure cantilever deflection

- Piezoelectric elements that facilitate precise scanning movements

- An electronic feedback loop to maintain constant force or height

Primary AFM Operational Modes

AFM can operate in several distinct modes, each suited to different sample types and measurement requirements [1] [3]:

Contact Mode: In this fundamental mode, the cantilever scans while applying a constant force onto the sample surface. The cantilever bends as it passes over surface features, and the feedback loop moves the Z scanner to maintain constant cantilever deflection, thereby mapping the surface topography [1]. This mode is typically used for hard samples but may damage soft surfaces [3].

Tapping Mode (Dynamic Mode): The cantilever oscillates at or near its resonance frequency, "tapping" the surface during scanning [1] [2]. The oscillation amplitude changes as the tip interacts with surface features, and the feedback system maintains a constant amplitude. This mode reduces lateral forces and is gentler on soft samples, making it suitable for biological applications [2] [5].

Non-Contact Mode: The cantilever oscillates above the sample surface without making direct contact. Changes in oscillation amplitude or frequency due to long-range forces (e.g., van der Waals, electrostatic) are used to map the topography. This mode is ideal for imaging soft samples as it minimizes sample damage [1] [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary AFM Operational Modes

| Operating Mode | Tip-Sample Interaction | Forces Measured | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Mode | Continuous physical contact | Repulsive forces | Hard samples; high-speed imaging | Can damage soft samples and blunt tips |

| Tapping Mode | Intermittent contact | Both attractive and repulsive forces | Soft, fragile, adhesive samples; biological materials | Slower scan speeds; complex operation |

| Non-Contact Mode | No physical contact; close proximity | Attractive forces (van der Waals, electrostatic) | High-resolution imaging of soft materials | Lower resolution; sensitive to contaminants |

Chemical Force Microscopy (CFM) Principles

Chemical Force Microscopy is a specialized variation of AFM that uses chemically modified tips to characterize materials surfaces based on specific chemical interactions rather than just morphological features [6] [7]. In CFM, the AFM tip is functionalized with specific chemical groups (typically using gold-coated tips with attached thiols, where R represents the functional groups of interest) [6]. This functionalization enables the measurement of chemical interactions such as hydrogen bonding, acid-base interactions, and hydrophobic/hydrophilic forces [6] [7].

CFM provides the ability to determine the chemical nature of surfaces irrespective of their specific morphology and facilitates studies of basic chemical bonding enthalpy and surface energy [6]. The technique is limited by thermal vibrations within the cantilever, which limits force measurement resolution to approximately 1 pN, though this remains sufficient for probing weak molecular interactions (e.g., COOH/CH3 interactions are ~20 pN per pair) [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CFM Tip Functionalization Protocol

Objective: To covalently attach specific chemical functional groups to AFM tips for chemical force measurements.

Materials:

- AFM cantilevers (typically silicon or silicon nitride)

- Gold or chromium coating equipment (for evaporation)

- Functional thiols (e.g., alkane thiols with desired terminal groups: -CH3, -COOH, -NH2)

- Appropriate solvents (ethanol, toluene)

- UV-ozone cleaner or oxygen plasma cleaner

Procedure:

- Cantilever Cleaning: Clean cantilevers in an ultraviolet (UV) ozone cleaner or oxygen plasma for 10-30 minutes to remove organic contaminants [6].

- Metal Coating: Deposit a thin adhesion layer (chromium or titanium, ~5 nm) followed by a gold layer (30-50 nm) onto the cantilevers using thermal or electron beam evaporation [6].

- Self-Assembled Monolayer Formation: Incubate the gold-coated cantilevers in a 1-10 mM solution of the desired functionalized thiol in ethanol or toluene for 12-24 hours to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) [6].

- Rinsing and Drying: Rinse the functionalized tips thoroughly with the pure solvent to remove physically adsorbed thiols, then dry under a gentle stream of nitrogen [6].

- Validation: Confirm monolayer formation using contact angle measurements or surface characterization techniques before use.

Force-Distance Spectroscopy Protocol for Microbial Surface Characterization

Objective: To measure adhesion forces and mechanical properties of microbial surfaces at the nanoscale.

Materials:

- Functionalized AFM probes (for CFM) or standard probes (for topography)

- Bacterial cells cultured to appropriate growth phase

- Appropriate buffer solution (e.g., PBS or growth medium)

- AFM with liquid cell capability

- Temperature control system (if needed)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Immobilize microbial cells on a solid substrate. Methods include:

AFM Calibration:

Force Curve Acquisition:

- Approach the functionalized tip to the microbial surface at a controlled speed (typically 0.5-1 μm/s) [8] [5]

- Record the cantilever deflection versus piezoelectric displacement

- Retract the tip while continuing to record deflection

- Repeat measurements at multiple locations on the cell surface (typically 50-100 force curves per cell) [8]

Data Analysis:

- Convert deflection versus displacement curves to force-distance curves using Hooke's law (F = -k × d) [5]

- Measure adhesion forces from the retraction curve "pull-off" events [8]

- Fit approach curves with appropriate contact mechanics models (e.g., Hertz, Sneddon, Johnson-Kendall-Roberts) to extract mechanical properties like Young's modulus [8] [5]

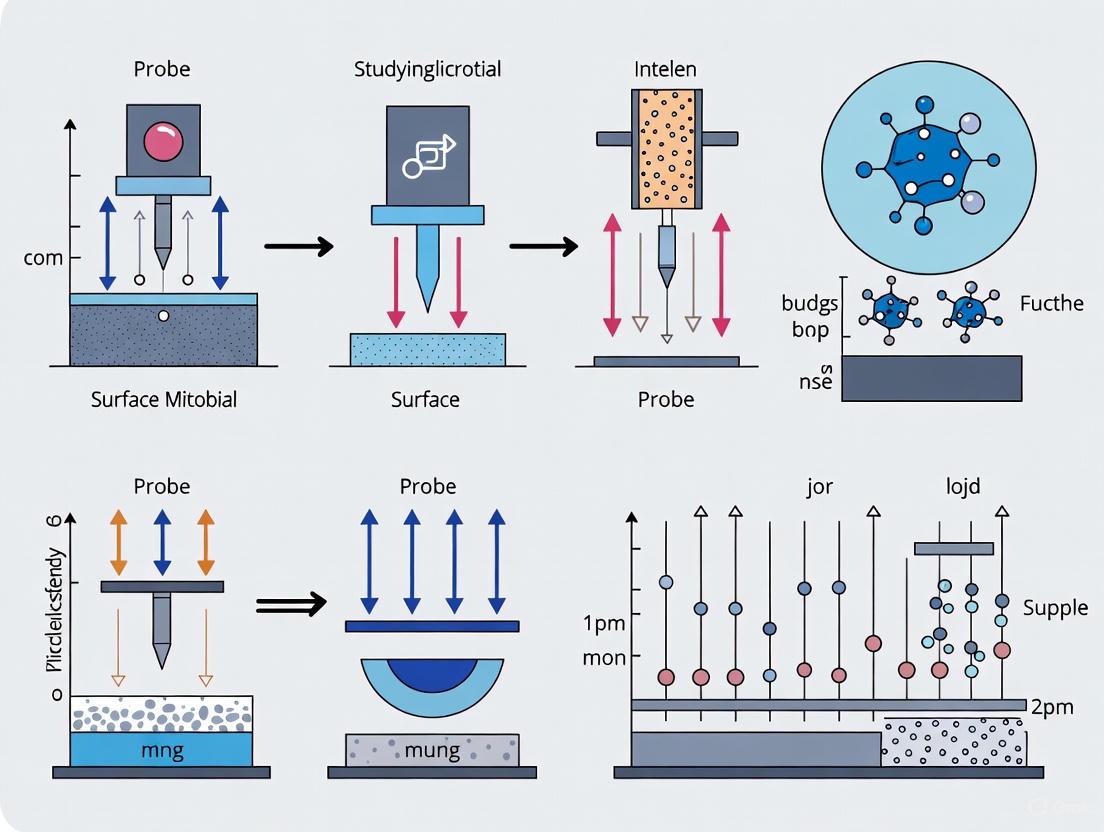

CFM Experimental Workflow for Microbial Surface Characterization

Frictional Force Mapping Protocol

Objective: To create spatial maps of chemical functionality across a sample surface.

Materials:

- Chemically functionalized AFM tips

- Patterned substrate with known chemical functionalities

- AFM with lateral force measurement capability

Procedure:

- Topography Imaging: First, image the sample topography in standard contact or tapping mode to identify regions of interest [6].

- Frictional Force Measurement: Scan the functionalized tip across the surface while monitoring torsional deflections (friction) of the cantilever [6].

- Load Dependence: Perform measurements at different applied loads to enhance contrast between different chemical functionalities [6].

- Data Interpretation: Analyze lateral force signals, where brighter areas in the friction image typically correspond to regions of stronger chemical interaction between the tip and surface functional groups [6].

Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AFM/CFM Microbial Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Thiols | Form self-assembled monolayers on gold-coated tips | CFM studies of hydrophobicity, specific molecular interactions | Choice of terminal group (-CH3, -COOH, -NH2) determines interaction specificity |

| Gold-Coated Cantilevers | Provide surface for thiol attachment | Standard substrate for CFM tip functionalization | Require chromium or titanium adhesion layer; typical thickness 30-50 nm |

| ITO-Coated Glass Substrates | Cell immobilization for liquid imaging | AFM of live microbial cells in physiological conditions | Hydrophobic properties facilitate cell adhesion without chemical fixation [9] |

| Porous Membranes | Mechanical cell entrapment | AFM of live cells without chemical modification | Polycarbonate filters with pore size smaller than cells [8] |

| Polyelectrolyte Coatings | Promote cell adhesion to substrates | Immobilization of microbial cells for AFM imaging | Coated surfaces improve cell adhesion while maintaining viability [8] |

| Appropriate Buffer Solutions | Maintain physiological conditions | Live-cell AFM under native conditions | PBS, growth media; consider osmolarity and ion composition |

Applications in Microbial Surface Research

Quantitative Analysis of Microbial Surface Properties

AFM and CFM provide quantitative data on various microbial surface properties, enabling detailed characterization of cellular structures and their functional implications.

Table 3: Quantitative Nanomechanical Properties of Microbial Systems Measured by AFM

| Microbial System | Young's Modulus (Stiffness) | Adhesion Forces | Measured Parameters | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodococcus wratislaviensis | Effective stiffness: 0.23 ± 0.05 N/m [9] | Not specified | Topography, nanomechanical properties | Liquid medium, no immobilization [9] |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | Not specified | Flagella interactions: ~20-50 nm height [10] | Cellular dimensions, flagellar structures | PFOTS-treated glass, dried samples [10] |

| Bacterial Nanotubes | Lower Young's modulus than cell body [9] | Not specified | Flexibility, intercellular connectivity | Liquid, living bacteria [9] |

| General Bacterial Cells | 0.1 - 2.5 MPa (varies by species and conditions) [5] | 0.1 - 10 nN (depending on tip chemistry) [8] | Elasticity, viscosity, adhesion | Buffer solutions, temperature control [5] |

Recent Advances and Applications

Nanotube Characterization: Recent studies using AFM in liquid have visualized bacterial nanotubes, revealing their lower Young's modulus compared to the main bacterial body, suggesting flexibility that facilitates intercellular communication and material transfer [9]. This application demonstrates AFM's capability to characterize previously unknown microbial structures under physiological conditions.

Biofilm Assembly Studies: Automated large-area AFM combined with machine learning has enabled the characterization of biofilm assembly over millimeter-scale areas, revealing spatial heterogeneity, cellular morphology, and the role of flagella in early biofilm formation [10]. This approach overcomes traditional AFM limitations of small scan areas and enables the correlation of nanoscale features with macroscale organization.

Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy: CFM has been applied to measure the unfolding forces of proteins on microbial surfaces, revealing details about internal protein structure and constituent interactions [6]. This approach provides fundamental insights into the structure-function relationships of cell surfaces at the single-molecule level.

Chemical Heterogeneity Mapping: CFM enables mapping of chemical group distributions across microbial surfaces with resolutions down to 10-20 nm, allowing researchers to correlate spatial organization of chemical functionalities with biological processes such as adhesion and host-pathogen interactions [7].

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool in microbiology for probing the nanoscale architecture and physicochemical properties of microbial cell surfaces under physiological conditions. Unlike electron microscopy techniques, which often require vacuum conditions and extensive sample preparation that can alter native structures, AFM enables the visualization of surface components on living cells in aqueous environments [11]. This capability provides unprecedented opportunities for researchers and drug development professionals to understand the structural and functional relationships of key microbial surface polymers—polysaccharides, peptidoglycan, and teichoic acids—which play crucial roles in cell shape maintenance, environmental interaction, antibiotic resistance, and pathogenesis [11] [12]. The application of AFM in microbial surface analysis spans both topographic imaging to resolve surface ultrastructure and force spectroscopy to quantify mechanical properties and molecular interactions, offering a comprehensive platform for investigating microbial surfaces at the single-molecule level [11].

Atomic Force Microscopy operates by scanning a sharp tip attached to a flexible cantilever across a sample surface while monitoring the tip-sample interactions. A laser beam reflected from the back of the cantilever onto a position-sensitive photodetector enables precise measurement of cantilever deflections, which correspond to surface topography and interaction forces [7] [12]. AFM can be operated in various modes, with contact mode and dynamic (tapping) mode being most common for biological imaging. Contact mode maintains constant cantilever deflection during scanning but may exert higher forces on delicate samples, while dynamic mode oscillates the cantilever near its resonance frequency, minimizing lateral forces and reducing sample damage [13].

Chemical Force Microscopy (CFM) represents a specialized AFM variant where the tip is chemically functionalized with specific molecular groups or biomolecules, enabling the detection of specific chemical interactions, mapping of functional group distribution, and measurement of binding forces at the single-molecule level [7]. This modification transforms the AFM tip into a sensor capable of probing specific ligand-receptor interactions, hydrophobic forces, or electrostatic interactions on microbial surfaces [7].

Table 1: Key AFM Operational Modes for Microbial Surface Analysis

| Mode | Principle | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Mode | Maintains constant cantilever deflection during scanning | High-resolution topography imaging of robust samples | Fast scanning speed; high resolution on hard samples | Potential sample deformation/damage from lateral forces |

| Dynamic (Tapping) Mode | Cantilever oscillates at or near resonance frequency | Imaging delicate surface structures on live cells | Minimal lateral forces; reduced sample damage | Slightly slower scanning speed than contact mode |

| Chemical Force Microscopy (CFM) | Uses chemically functionalized tips | Mapping chemical group distribution; specific molecular recognition | Enables chemical contrast; detects specific interactions | Requires tip functionalization expertise |

| Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS) | Measures force-distance curves at single points | Probing mechanical properties of single molecules; receptor-ligand binding | Quantifies interaction forces at pico-Newton resolution | Time-consuming for mapping large areas |

| Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS) | Uses a whole cell attached to the cantilever | Measuring cell adhesion forces to surfaces or other cells | Provides direct measurement of cellular adhesion | Cell immobilization on cantilever can be challenging |

Visualizing Polysaccharides

Structural Insights and Imaging Protocols

Microbial surface polysaccharides, including exopolysaccharides, capsular polysaccharides, and other glycopolymers, play critical roles in protection, adhesion, and biofilm formation. AFM enables direct visualization of these structures at the single-molecule level under "near-native" conditions, providing insights into their morphological features and molecular characteristics [13]. AFM imaging has revealed that polysaccharides can exhibit diverse nanostructures including linear chains, branched structures, helical assemblies, and complex networks [13]. For instance, AFM studies of the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG revealed a rough surface morphology decorated with nanoscale waves corresponding to extracellular polysaccharides, features that were significantly diminished in a mutant strain impaired in exopolysaccharide production [11].

The following workflow outlines the standard protocol for polysaccharide imaging via drop deposition:

Protocol 1: AFM Imaging of Isolated Polysaccharides

Sample Preparation:

Substrate Preparation and Deposition:

- Use freshly cleaved mica as substrate for most applications due to its atomically flat surface.

- Apply 10-20 µL of polysaccharide solution to mica surface and allow adsorption for 1-5 minutes.

- Remove excess liquid by gentle blotting and air-dry under mild conditions or under nitrogen gas flow [13].

AFM Imaging Parameters:

- Operate in dynamic (tapping) mode to minimize sample deformation.

- Use silicon cantilevers with spring constants of 0.5-5 N/m and resonant frequencies of 50-150 kHz.

- Optimize scan parameters (setpoint, gains) to maintain minimal imaging force (typically 250 pN to 1 nN) [13].

- Perform imaging in air or liquid depending on the required conditions, with liquid imaging preserving more native structures.

Quantitative Analysis of Polysaccharide Nanostructures

AFM enables not only qualitative assessment of polysaccharide morphology but also quantitative analysis of molecular dimensions. Height measurements from AFM topography are particularly reliable as they are less affected by tip-broadening effects compared to lateral dimensions [13]. These measurements have revealed structural details for various polysaccharides: curdlan triple helices show heights of 0.6-1.0 nm, xanthan exhibits heights of 0.7-1.5 nm, while carrageenan helix diameters range from 0.8-2.0 nm [13].

Table 2: AFM-Dimensional Parameters of Selected Microbial Polysaccharides

| Polysaccharide | Source | Height/Diameter (nm) | Observed Nanostructures | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curdlan | Bacteria (Agrobacterium) | 0.6-1.0 nm | Triple helices, network structures | Height consistent with triple helix model |

| Xanthan | Xanthomonas campestris | 0.7-1.5 nm | Single strands, branched networks | Side chains influence chain stiffness |

| Carrageenan | Red Seaweeds | 0.8-2.0 nm | Helical structures, aggregates | Molecular conformation affects gelation |

| Gellan | Sphingomonas elodea | 0.5-0.8 nm | Single & double helices | Double helices ~1.6 nm height |

| Bacterial Capsular Polysaccharides | Various Gram-negative bacteria | 1.0-2.5 nm | Capsular layers surrounding cells | Visualized on intact cells |

Probing Peptidoglycan Architecture

High-Resolution Imaging of Bacterial Cell Walls

Peptidoglycan is the fundamental structural constituent of the bacterial cell wall, providing mechanical strength and cell shape. Despite its essential functions, the three-dimensional organization of peptidoglycan has long been controversial, with competing models proposing either a layered, woven fabric or a scaffold-like structure [14]. AFM has provided crucial experimental evidence to address this controversy through high-resolution imaging of both isolated sacculi and living cells.

In Gram-positive bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis, AFM studies of isolated sacculi have revealed a regular architecture of approximately 50-nm-wide cables running parallel to the short axis of the cell, with cross-striations exhibiting ~25 nm periodicity along each cable [11]. These observations supported a coiled-coil model where glycan strands form peptidoglycan ropes that are helically arranged [11]. More recent studies have demonstrated that peptidoglycan architecture is not static but undergoes remodeling during growth. In Bacillus subtilis strain AS1.398, the side wall peptidoglycan transitions from an irregular architecture during exponential growth to an ordered cable-like architecture in stationary phase [15].

The protocol below details the preparation and imaging of peptidoglycan sacculi:

Protocol 2: Isolation and AFM Imaging of Peptidoglycan Sacculi

Cell Culture and Harvest:

- Grow bacterial cells to desired growth phase (mid-exponential, late exponential, or stationary phase) as peptidoglycan architecture changes during growth [15].

- Harvest cells by centrifugation at appropriate speed for the bacterial species.

Sacculi Purification:

- Resuspend cell pellets in deionized water and boil for 7 minutes to inactivate autolysins.

- Treat with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 5% w/v) to solubilize membranes and proteins.

- Incubate with DNase (0.5 mg/mL), RNase (0.5 mg/mL), and pronase (2 mg/mL) to remove nucleic acids and proteins.

- Remove secondary cell wall polymers by treatment with 48% hydrofluoric acid (HF) at 4°C for 24 hours [15].

- Wash purified sacculi thoroughly with MilliQ water (at least three times).

AFM Sample Preparation and Imaging:

- Dilute sacculi in MilliQ water and deposit onto freshly cleaved mica.

- Air-dry samples before imaging in ambient conditions, or image under liquid for more native structures.

- Use ScanAsyst or dynamic mode with silicon cantilevers (spring constant ~2.7 N/m) for high-resolution imaging [15].

Single-Molecule Recognition Imaging of Peptidoglycan

AFM single-molecule recognition imaging enables the specific localization of peptidoglycan components on living cells. This technique combines dynamic force microscopy with force spectroscopy using functionalized tips. For example, tips modified with vancomycin (which binds to D-Ala-D-Ala sites in peptidoglycan) or LysM domains (which bind to glycan strands) allow specific mapping of peptidoglycan distribution on living cells [11] [14].

In studies of Lactococcus lactis, wild-type cells displayed a smooth surface when imaged with conventional AFM, but mutant strains lacking cell wall exopolysaccharides revealed 25-nm-wide periodic bands running parallel to the short axis of the cell [14]. Recognition imaging using LysM-functionalized tips confirmed that these bands consisted of peptidoglycan, demonstrating that in wild-type cells, peptidoglycan is hidden by an outer layer of surface constituents [14]. This application of AFM has revealed species-specific variations in peptidoglycan architecture, providing evidence against a universal structural model [11].

Nanomechanical Properties of Peptidoglycan

Force spectroscopy measurements have quantified how modifications in peptidoglycan structure affect mechanical properties of the cell envelope. In Staphylococcus aureus, reduction of peptidoglycan crosslinking through deletion of penicillin-binding protein 4 (PBP4) resulted in decreased cell wall stiffness, demonstrating the correlation between crosslinking density and mechanical integrity [16]. This relationship has important implications for understanding antibiotic resistance mechanisms, as cell wall mechanical properties influence susceptibility to antimicrobial agents [17].

Table 3: AFM Applications in Peptidoglycan Research

| Application | Key Findings | Experimental Approach | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture Imaging | 25-50 nm wide cables running parallel to short cell axis in Bacillus; varies by growth phase | Isolated sacculi imaging on mica substrates | Revealed structural remodeling during growth; strain-specific differences |

| Live Cell Peptidoglycan Mapping | Hidden peptidoglycan in wild-type cells; exposed in polysaccharide-deficient mutants | Single-molecule recognition imaging with LysM or vancomycin tips | Demonstrated outer polysaccharide layer masks underlying peptidoglycan |

| Mechanical Properties | Reduced crosslinking decreases cell wall stiffness | Force spectroscopy on live cells; nanoindentation | Established link between chemical structure and mechanical function |

| Division Site Analysis | Distinct architecture at septa compared to side walls | High-resolution imaging of division sites | Insights into cell division process and new peptidoglycan insertion |

Analyzing Teichoic Acids

Distribution and Organization on Cell Surfaces

Teichoic acids are anionic polymers found in the cell walls of Gram-positive bacteria, playing important roles in cell elongation, division, and interaction with environment. While their biochemical composition has been characterized, their spatial organization and dynamics on the cell surface remain challenging to study. AFM has been combined with fluorescence microscopy to map the distribution of wall teichoic acids (WTAs) in Lactobacillus plantarum, revealing that these polymers are required for proper cell elongation and division [11].

The distribution of teichoic acids can be indirectly visualized by comparing wild-type and mutant strains. For instance, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of Lactococcus lactis wild-type and mutant strains lacking cell wall polysaccharides showed that the outermost surface of mutants was essentially composed of peptidoglycan with some lipids, while wild-type strains showed much higher polysaccharide content [14]. This approach, combined with AFM imaging, enables researchers to correlate surface composition with nanoscale topography.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for AFM-Based Microbial Surface Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Freshly Cleaved Mica | Atomically flat substrate for sample adsorption | Ideal for polysaccharide and sacculi imaging; provides clean background |

| Silicon Cantilevers | Sensing probe for surface topography | Spring constants 0.01-0.10 N/m for live cells; 0.5-5 N/m for isolated structures |

| Poly-L-Lysine | Cell immobilization on substrates | Promotes adhesion of negatively charged cells to surfaces; 0.1% solution |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Membrane solubilization in sacculi preparation | 5% w/v solution for removing membranes during peptidoglycan purification |

| HF (Hydrofluoric Acid) | Removal of secondary cell wall polymers | 48% v/v at 4°C for 24h; EXTREME CAUTION required due to high toxicity |

| Vancomycin-Functionalized Tips | Recognition of D-Ala-D-Ala sites in peptidoglycan | Single-molecule force spectroscopy of peptidoglycan distribution |

| LysM-Functionalized Tips | Recognition of N-acetylglucosamine in glycan strands | Mapping peptidoglycan organization on live cells |

| Lectin-Functionalized Tips | Recognition of specific sugar moieties | Identification and localization of polysaccharide types on cell surfaces |

AFM technologies provide powerful approaches for visualizing the nanoscale organization of microbial surface components under physiological conditions. The ability to image living cells at molecular resolution, combined with single-molecule force spectroscopy techniques, has transformed our understanding of polysaccharide architecture, peptidoglycan organization, and teichoic acid distribution. These structural insights are particularly valuable for drug development professionals investigating antibiotic resistance mechanisms, as the mechanical properties and organizational dynamics of microbial surface polymers directly influence susceptibility to antimicrobial agents. The protocols and applications detailed in these Application Notes provide a foundation for researchers to investigate the intricate architecture of microbial surfaces and its relationship to cellular function and pathogenicity.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has evolved from a topographical imaging tool into a versatile platform for investigating chemical and biological interactions at the single-molecule level. This transformation is largely enabled by chemical functionalization of AFM tips, which creates specific molecular interfaces for precise probing of microbial surfaces. For researchers investigating microbial surface properties, functionalized tips serve as biospecific sensors that can detect and localize individual target molecules on cell surfaces, measure binding forces, and map mechanical properties under physiological conditions [18] [8].

The fundamental principle involves tethering specific sensor molecules (e.g., antibodies, oligonucleotides, or small molecules) to the AFM tip apex, converting it into a molecular recognition device [18]. When these functionalized tips are brought into contact with microbial surfaces, they can probe specific interactions with piconewton sensitivity and nanometer spatial resolution, providing unprecedented insights into the structure-function relationships of microbial cell surfaces [8]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying antimicrobial resistance mechanisms, biofilm formation, and host-pathogen interactions, where molecular-scale events dictate macroscopic outcomes.

Key Functionalization Strategies

Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-Based Spacer Chemistry

The most established functionalization approach uses heterobifunctional PEG crosslinkers containing distinct reactive groups at each terminus. These crosslinkers typically feature a thiol group for gold-coated tip surfaces and an amine-reactive group (such as N-hydroxysuccinimide ester) for coupling to proteins [18] [19].

Table: PEG-Based Functionalization Components

| Component | Function | Typical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Gold-coated AFM tips | Provides surface for thiol bonding | 10-50 nm gold layer over 2-5 nm chromium adhesion layer |

| Alkanethiol-PEG-NHS crosslinker | Flexible tether with reactive ends | PEG length: 6-10 nm (approximately 24 ethylene oxide units) |

| Sensor molecules | Biological recognition elements | Antibodies, antigens, oligonucleotides, or small molecules |

The PEG spacer plays multiple critical roles: it provides molecular flexibility allowing the sensor molecule to freely orient and interact with its target; it separates the recognition event from the tip surface, reducing nonspecific interactions; and its known length (typically 6-10 nm) provides a characteristic rupture signature in force-distance curves that helps distinguish specific from nonspecific binding events [18] [19].

Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition (PECVD)

For creating uniformly functionalized tips with amine groups, PECVD of aminated precursors offers a rapid, reproducible alternative to liquid-phase methods. This approach deposits thin, uniform coatings of aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) through gas-phase deposition, creating a high density of amine functional groups on the tip and cantilever [20].

The PECVD process involves:

- Placing AFM probes in a vacuum chamber

- Introducing APTES vapor under controlled conditions

- Applying RF plasma power (typically 14 W) to initiate deposition

- Forming a stable, functional aminized layer in approximately 30 seconds

This method produces coatings approximately 5.2 nm thick with high amine group density, excellent stability under varying environmental conditions, and minimal impact on tip radius compared to gold coating methods [20]. The amine-functionalized tips can subsequently be used for coupling various biological molecules using standard conjugation chemistry.

DNA Tetrahedra Nanostructures

An innovative approach uses three-dimensional DNA nanostructures as molecular scaffolds for tip functionalization. DNA tetrahedra composed of four oligonucleotides forming a rigid, pyramidal structure offer several advantages: precisely controlled three-dimensional geometry, defined positioning of functional groups, and inherent biocompatibility [21].

The functionalization protocol involves:

- Designing tetrahedra with three thiol-modified vertices for gold surface attachment

- Incorporating a biotin or aptamer-modified vertex for molecular recognition

- Pre-assembling tetrahedra in solution before tip immobilization

- Attaching complete nanostructures to gold-coated tips via thiol-gold chemistry

This method enables "dip-and-measure" tip chemistry with sharply defined rupture length distributions and high success rates, particularly advantageous when working with DNA aptamers as sensing molecules [21].

Atomically Defined Tips for Fundamental Interactions

For ultrahigh vacuum applications probing fundamental chemical interactions, researchers have developed atomically defined tip terminations using single molecules or atoms. Common approaches include:

- CO-terminated tips: Provide exceptional resolution for organic molecules but exhibit significant flexibility that can cause imaging artifacts [22] [23]

- Xe-terminated tips: Offer chemical passivation but similar flexibility issues as CO tips [22]

- CuOx-tips: Feature covalent oxygen bonding to copper tips, providing higher rigidity and selectively increased chemical reactivity that prevents tip-bending artifacts while generating distinct chemical contrast [22]

These tip functionalizations have revealed site-specific chemical interactions on metal surfaces with picometer resolution, enabling quantification of weak chemical forces that govern molecular adsorption and surface reactions [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: PEG-Based Antibody Functionalization

This protocol describes the functionalization of AFM tips with antibodies for specific antigen recognition on microbial surfaces, adapted from established methodologies [18] [19].

Table: Reagents and Equipment

| Item | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| AFM probes | Silicon nitride, triangular cantilevers | Functionalization substrate |

| Cantilever spring constant | 0.01-0.1 N/m | Optimal for biological force measurements |

| Alkanethiol-PEG-NHS | MW ~3400 Da (24 ethylene oxide units) | Flexible heterobifunctional crosslinker |

| Ethanol | Absolute, high purity | Solvent for SAM formation |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | 10 mM, pH 7.4 | Coupling and washing buffer |

| Antibody solution | 0.1-0.5 mg/mL in PBS | Recognition element |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Tip cleaning and gold coating: Clean silicon nitride tips with oxygen plasma (5 min, 100 W) followed by thermal evaporation of 2 nm chromium adhesion layer and 15 nm gold layer under high vacuum.

Self-assembled monolayer formation: Incubate gold-coated tips in 1 mM alkanethiol-PEG-NHS solution in ethanol for 2 hours at room temperature protected from light.

Rinsing and drying: Rinse thoroughly with absolute ethanol to remove physically adsorbed molecules and blow dry under gentle nitrogen stream.

Antibody coupling: Incubate functionalized tips in 0.1-0.5 mg/mL antibody solution in PBS (pH 7.4) for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

Quenching and stabilization: Immerse tips in 1M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 10 minutes to quench unreacted NHS esters, then rinse with PBS.

Storage: Store functionalized tips in PBS at 4°C and use within 48 hours for optimal activity.

Quality Control: Validate functionalization by performing force-distance measurements on surfaces with known antigen distribution. Successful functionalization shows characteristic rupture events with lengths corresponding to PEG spacer extension (approximately 9-10 nm for PEG24) and specific force signatures [19].

Protocol: PECVD Amination of AFM Tips

This protocol describes gas-phase amination of AFM tips using PECVD for creating amine-functionalized surfaces [20].

Procedure:

Tip cleaning: Clean silicon or silicon nitride AFM probes with oxygen plasma (2 min, 50 W) to remove organic contaminants and activate the surface.

PECVD chamber preparation: Place tips in PECVD reactor chamber and evacuate to base pressure (<5×10⁻² mbar).

Precursor introduction: Introduce APTES vapor into the chamber using a controlled argon carrier gas flow.

Plasma deposition: Apply RF plasma power (14 W) for 30 seconds to deposit aminized coating.

Post-processing: Remove functionalized tips and characterize coating thickness by ellipsometry on reference silicon wafers processed simultaneously.

Validation: Confirm successful functionalization by chemical force titration in buffers of varying pH, monitoring adhesion forces characteristic of amine group ionization [20].

Applications in Microbial Surface Research

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy of Microbial Adhesins

Functionalized AFM tips enable quantification of ligand-receptor interactions on microbial surfaces with single-molecule resolution. In a typical experiment, tips functionalized with specific host receptors (e.g., fibronectin, laminin) are used to probe corresponding adhesins on microbial surfaces, revealing binding kinetics, strength, and spatial distribution [8].

Force-distance curves obtained from these measurements provide:

- Adhesion force: The force required to rupture single molecular complexes

- Rupture length: Characteristic distance corresponding to spacer molecule extension

- Unbinding work: Energy dissipated during the unbinding process

For microbial research, this approach has revealed how pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans display specific adhesins with nanoscale organization that contributes to host attachment and biofilm formation [8].

Mapping Nanomechanical Properties of Biofilms

Functionalized tips with controlled chemistry enable precise mapping of nanomechanical properties of microbial biofilms. By using tips functionalized with specific chemical groups (e.g., charged, hydrophobic, or hydrophilic), researchers can correlate spatial heterogeneity in chemical composition with mechanical behavior in developing biofilms [10] [24].

Advanced AFM modes including force volume, nano-DMA, and bimodal AFM provide viscoelastic parameter mapping (Young's modulus, adhesion, energy dissipation) that reveals how extracellular polymeric substances contribute to biofilm mechanical integrity and antibiotic resistance [24].

Recognition Imaging of Surface Antigens

Combining functionalization with advanced imaging modes enables molecular recognition imaging, which simultaneously maps topography and specific binding sites on microbial surfaces. This technique uses tips functionalized with antibodies or lectins to identify the distribution of specific antigens or carbohydrates on microbial cells [18] [8].

In practice, recognition imaging has revealed:

- Heterogeneous distribution of virulence factors on pathogenic bacteria

- Dynamic changes in surface composition during biofilm development

- Spatial organization of drug targets on fungal pathogens

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AFM Tip Functionalization

| Reagent/Category | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Gold-coated AFM probes | Substrate for thiol-based chemistry | Coating thickness affects tip radius; spring constant (0.01-0.5 N/m) should match application |

| Heterobifunctional PEG crosslinkers | Flexible spacers for biomolecule attachment | Length (2-20 nm) affects accessibility; endpoint chemistry must match biomolecule |

| DNA tetrahedra nanostructures | Molecular scaffolds for precise functionalization | Pre-assembled structures offer defined geometry; ideal for nucleic acid probes |

| Aminosilane compounds (e.g., APTES) | Primary amine introduction for subsequent coupling | Liquid-phase deposition can yield multilayers; PECVD offers better control |

| NHS-ester compounds | Amine-reactive chemistry for protein coupling | Hydrolyzes in aqueous solution; use fresh preparations |

| Maleimide compounds | Thiol-reactive chemistry for cysteine-containing proteins | Requires reducing conditions for free thiol maintenance |

| Biomolecular recognition elements | Target-specific probes (antibodies, aptamers, lectins) | Purification and activity preservation are critical; orientation affects function |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Force-Distance Curve Analysis

Interpreting force-distance curves is essential for distinguishing specific molecular interactions from nonspecific binding. The following dot script illustrates the key features analyzed:

Key analysis parameters:

- Specific binding: Shows characteristic rupture length corresponding to PEG spacer extension (typically 8-12 nm for PEG24) and quantifiable adhesion forces [19]

- Nonspecific binding: Lacks defined rupture length, often shows multiple irregular peaks, and typically exhibits higher adhesion forces [19]

- Multiple binding events: Display sequential rupture peaks suggesting simultaneous engagement of multiple molecular pairs

Statistical Analysis of Single-Molecule Interactions

Robust analysis requires collecting hundreds to thousands of force-distance curves from multiple experiments. Data should be filtered to exclude nonspecific interactions before constructing:

- Adhesion force histograms: Reveal most probable unbinding forces

- Rupture length distributions: Confirm specificity through spacer length correlation

- Force maps: Spatial distribution of binding events across microbial surfaces

Control experiments with blocked receptors, competitive inhibition, or irrelevant functionalizations are essential to verify specificity [19] [8].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Functionalization Issues

Table: Troubleshooting AFM Tip Functionalization

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No specific interactions | Low probe density, incorrect orientation, denatured probes | Optimize coupling density, use oriented coupling strategies, verify probe activity |

| High nonspecific adhesion | Incomplete SAM formation, exposed tip surface | Extend SAM formation time, include backfilling step with short-chain thiols |

| Inconsistent results | Tip contamination, probe degradation, unstable functionalization | Implement rigorous cleaning, use fresh reagents, verify storage conditions |

| Multiple binding events | Excessive probe density leading to multivalent interactions | Dilute coupling concentration, reduce incubation time |

Optimizing for Microbial Applications

When studying microbial surfaces, consider these specific optimizations:

- Spring constant calibration: Use thermal tuning method for accurate force quantification

- Physiological conditions: Maintain appropriate temperature, pH, and ion composition to preserve microbial viability

- Contact time optimization: Vary surface contact time (0.1-1.0 s) to probe binding kinetics

- Loading rate dependence: Vary retraction velocity (0.1-10 μm/s) to explore energy landscapes

Future Perspectives

Recent advances in AFM tip functionalization are creating new opportunities for microbial research. DNA-based nanostructures offer precisely defined geometry for multiplexed detection [21]. Plasma-based functionalization provides highly reproducible coatings for quantitative comparison across experiments [20]. Machine learning integration enables automated analysis of force spectroscopy data, revealing subtle patterns in molecular interactions across microbial populations [10].

These developments will enhance our understanding of fundamental microbial processes, including antimicrobial resistance mechanisms, biofilm maturation, and host-microbe interactions, ultimately contributing to new therapeutic strategies for managing microbial infections.

Force-distance (F-D) curves, obtained via atomic force microscopy (AFM), are a foundational tool in nanomechanics for quantifying the physical and adhesive properties of surfaces at the nanometer scale [25]. In chemical force microscopy of microbial surfaces, F-D spectroscopy enables researchers to probe the ultrastructure, mechanical behavior, and interaction forces of living cells under physiological conditions [26] [12]. This technique operates by measuring the force experienced by a sharp AFM probe as it approaches and retracts from a sample surface, generating a curve that contains a wealth of information about material properties such as elasticity, adhesion, and deformation [25]. The application of F-D curve analysis to microbes has revolutionized our understanding of cell surface layers [26], phenotypic heterogeneity [27], and biofilm assembly [10], providing critical insights for drug development, antimicrobial strategies, and biomedical research.

Basic Principles of Force-Distance Curve Analysis

The Force-Distance Curve

An F-D curve is recorded by monitoring the deflection of a cantilever as a probe approaches, contacts, and retracts from the sample surface while maintaining a constant XY position [25]. The raw data of cantilever deflection versus Z-scanner position is converted into a quantitative force-separation curve through calibration procedures, including determining the cantilever's spring constant [25]. The resulting curve features distinctive regions corresponding to different interaction regimes between the tip and sample:

- Non-contact region (A): The probe is far from the surface with no detectable interaction [25].

- Snap-in point (B): An attractive force gradient causes the probe to jump into contact with the surface [25].

- Contact region (C): Repulsive forces dominate as the probe indents the sample [25].

- Adhesion regime (D): During retraction, attractive forces cause cantilever deflection toward the surface [25].

- Pull-off point (E): The probe separates from the surface when the cantilever's restoring force exceeds the adhesion force [25].

Key Measurable Parameters

From F-D curves, researchers can extract several quantitative nanomechanical parameters:

- Young's modulus: Calculated from the slope of the force-indentation curve in the contact region using appropriate contact mechanics models [25] [28].

- Adhesion force: Measured as the maximum negative force in the retract curve, representing the force required to separate the tip from the sample [25].

- Adhesion energy: Determined by calculating the area between the retract curve and the baseline [25].

- Energy dissipation: Represented by the hysteresis between approach and retract curves, indicating energy loss through irreversible processes [25].

- Stiffness: The slope of the force-separation curve in the contact region [25].

Table 1: Key parameters obtained from force-distance curve analysis

| Parameter | Description | Extraction Method | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | Intrinsic material stiffness | Slope of force-indentation curve with contact models | Pa |

| Adhesion Force | Maximum force to separate surfaces | Minimum force value in retract curve | nN |

| Adhesion Energy | Work required for separation | Area under retract curve | aJ |

| Stiffness | Resistance to deformation | Slope of contact region | N/m |

| Energy Dissipation | Irreversible energy loss | Hysteresis area between approach/retract curves | aJ |

Experimental Protocols for Microbial Analysis

Microbial Cell Immobilization

Successful F-D analysis requires robust immobilization of live microbial cells without altering their surface properties. Multiple effective strategies have been developed:

- Gelatin coating: Gelatin-coated glass surfaces provide effective immobilization for various bacterial species. Cells are centrifuged, washed, resuspended, and deposited on gelatin-coated slides for 30 minutes before gentle rinsing [27].

- Physical entrapment: Porous polymer membranes (e.g., polycarbonate) with pore sizes smaller than the cells can physically trap microorganisms while allowing AFM probe access [12].

- Chemical fixation: Thin layers of polydopamine or poly-L-lysine on substrates promote strong cell adhesion through electrostatic interactions [12].

- Agarose embedding: Microbial cells can be partially embedded in a thin agarose gel, providing stability while maintaining physiological conditions [12].

Probe Selection and Functionalization

The choice of AFM probe significantly influences F-D measurements:

- Colloidal probes: For single-cell mechanical properties, 5μm diameter glass beads attached to tipless cantilevers provide well-defined geometry and minimize local surface heterogeneity effects [27] [29].

- Sharp tips: Standard sharp tips (2-50nm radius) are preferred for high-resolution mapping of specific surface features and single-molecule interactions [12] [25].

- Functionalized probes: Tips chemically modified with specific functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, amine) or biomolecules enable chemical force microscopy to map chemical group distribution and specific receptor-ligand interactions on microbial surfaces [25] [28].

Force Spectroscopy Acquisition Parameters

Optimal parameter selection ensures reliable and reproducible data:

- Force setpoint: Typically 0.5-1nN for living microbial cells to avoid damage [29].

- Approach/retract speed: 0.5-1μm/s to minimize hydrodynamic effects while capturing relevant interactions [29].

- Sampling rate: Sufficiently high to detect short-range interactions (often 2-10kHz) [25].

- Contact time: Brief (100-500ms) to minimize plastic deformation or molecular rearrangements [25].

- Spatial sampling: Grid patterns (e.g., 16×16 to 64×64 points) for force volume mapping over single cells or surface areas [25].

Diagram 1: Microbial force-distance analysis workflow

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Contact Mechanics Models

The extraction of quantitative mechanical properties from F-D curves requires fitting the contact region with appropriate mechanical models. The choice of model depends on sample properties, tip geometry, and dominant forces:

- Hertz model: Applied for purely elastic, non-adhesive contacts with various tip geometries [25] [28].

- Sneddon model: A generalization of Hertz model for different indenter shapes [28].

- Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) model: Suitable for highly adhesive contacts with large tip radii and high surface energies [25] [28].

- Derjaguin-Müller-Toporov (DMT) model: Appropriate for contacts with low adhesion and small tip radii [25] [28].

- Oliver-Pharr model: Commonly used for materials exhibiting plastic deformation [28].

Table 2: Contact mechanics models for F-D curve analysis

| Model | Applicable Conditions | Adhesion Consideration | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hertz | Elastic, non-adhesive | Negligible | Bacterial cell walls, intracellular components |

| Sneddon | Elastic, various indenters | Negligible | Fungal cells, yeast |

| JKR | High adhesion, large radius | Included | Microbial biofilms, adhesive mutants |

| DMT | Low adhesion, small radius | Included | Virus capsids, S-layers |

| Oliver-Pharr | Elastic-plastic | Optional | Dried microbes, surface layers |

Adhesion Event Analysis

The retraction portion of F-D curves reveals adhesive interactions through distinctive features:

- Single adhesion events: Sharp discontinuities indicating simultaneous rupture of multiple bonds [25].

- Multiple unbinding events: Sawtooth patterns with sequential rupture peaks characteristic of polymer unfolding or sequential bond breaking [25].

- Adhesion force distribution: Statistical analysis of multiple curves reveals heterogeneity in surface adhesion properties [27] [25].

For microbial systems, adhesion analysis has revealed that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structures significantly influence population heterogeneity. Partial removal of LPS from Escherichia coli surfaces via EDTA treatment reduces cell-to-cell variability in adhesion forces and elasticity, homogenizing population behavior [27].

Applications in Microbial Surface Characterization

Nanomechanical Properties of Microbial Cells

F-D curve analysis has revealed substantial diversity in mechanical properties across microbial species and conditions:

- Bacterial elasticity: Measurements of Gram-negative bacteria show that LPS composition significantly impacts cell stiffness, with modified strains exhibiting markedly different Young's modulus values [27].

- Fungal mechanical properties: AFM indentation of fungal cells reveals how cell wall composition determines rigidity and response to antifungal agents [26].

- Antibiotic effects: Time-dependent changes in mechanical properties following antibiotic exposure can indicate mechanism of action and resistance development [28].

- Phenotypic heterogeneity: Single-cell analysis reveals subpopulations with distinct mechanical properties within clonal cultures, with potential implications for virulence and environmental adaptation [27].

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy

AFM enables the measurement of specific molecular interactions on microbial surfaces through functionalized probes:

- Ligand-receptor binding: Tips modified with specific receptors can map their distribution and measure binding kinetics on living cells [25] [28].

- Protein unfolding: Force-induced unfolding of membrane proteins reveals structural stability and conformational changes [26] [25].

- Antibody-antigen interactions: Binding forces between therapeutic antibodies and surface antigens provide insights for drug development [28].

Diagram 2: Information and applications from microbial F-D curves

Chemical Force Microscopy

By modifying AFM tips with specific chemical functionalities, researchers can map the distribution of chemical groups on microbial surfaces:

- Hydrophobicity mapping: Tips with methyl groups reveal heterogeneous distribution of hydrophobic domains [28].

- Charge mapping: Carboxyl- and amine-modified probes electrostatic potential variations across cell surfaces [26] [28].

- Specific molecular recognition: Antibody-functionalized tips identify antigen localization on pathogens [25] [28].

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

High-Throughput and Large-Area AFM

Traditional AFM limitations in scan area are being addressed through automated large-area approaches that acquire high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas [10]. This advancement enables:

- Biofilm architecture analysis: Correlation of local nanomechanical properties with overall biofilm structure and organization [10].

- Rare cell identification: Detection of mechanical outliers in heterogeneous microbial populations [27] [10].

- Combinatorial surface studies: Assessment of bacterial adhesion and mechanics across surface chemistry gradients [10].

Integration with Machine Learning

Machine learning algorithms are transforming F-D curve analysis through:

- Automated curve classification: Rapid identification of curve types and artifacts in large datasets [10].

- Feature extraction: Unsupervised identification of relevant parameters from complex F-D signatures [10].

- Predictive modeling: Correlation of mechanical properties with biological states or treatment outcomes [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for microbial F-D analysis

| Item | Specifications | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cantilevers | Si₃N₄, k=0.01-0.5 N/m, colloidal probes (5μm) | Force sensing with minimal cell damage | Bacterial cell mechanics, adhesion mapping |

| Immobilization Substrates | Gelatin-coated glass, polycarbonate membranes, polydopamine | Secure cell fixation during measurement | Live cell imaging under physiological conditions |

| Calibration Standards | Certified reference samples (e.g., PDMS, glass) | Cantilever spring constant calibration | Quantitative modulus measurement |

| Functionalization Reagents | Dendrons, PEG linkers, specific antibodies | Tip modification for chemical force microscopy | Ligand-receptor binding studies |

| Cell Culture Media | LB broth, Schneider's medium, specific formulations | Maintain cell viability during experiments | Live cell measurements in liquid |

| Analysis Software | MountainsSPIP, JPK SPM software, MATLAB | F-D curve processing and model fitting | Data quantification and visualization |

Force-distance curve analysis provides an exceptionally powerful framework for quantifying the nanomechanical and adhesive properties of microbial surfaces at unprecedented resolution. The techniques and applications outlined in this protocol enable researchers to connect mechanical properties to biological function, offering insights into microbial pathogenesis, antibiotic mechanisms, and surface interactions. As automated large-area AFM and machine learning approaches continue to evolve [10], F-D spectroscopy is poised to reveal even greater complexity in microbial systems, accelerating discovery in drug development and biomedical research. The integration of nanomechanical characterization with molecular biology approaches will further enhance our understanding of how physical properties contribute to microbial life processes and adaptation.

The Critical Role of Physiological Conditions in Preserving Native Microbial States

The investigation of microbial surface properties is a cornerstone of research in drug development, microbiology, and biomedical engineering. The field of chemical force microscopy (CFM) has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose, enabling the nanoscale mapping of physical and chemical properties on live microbial cells. A paramount, yet often underappreciated, principle governing the success and biological relevance of these studies is the strict maintenance of physiological conditions throughout the experimental workflow. This application note details the critical protocols and methodologies for preserving the native state of microbial cells, from sample preparation through to CFM analysis. We provide a structured guide featuring quantitative data tables, detailed experimental procedures, essential reagent solutions, and visual workflows, all framed within the context of obtaining physiologically relevant data on microbial surface properties.

The microbial cell surface is the primary interface for environmental interaction, mediating critical processes such as host-pathogen recognition, biofilm formation, and response to antimicrobial agents [12]. Consequently, the surfaceome—the compendium of surface-exposed proteins, lipids, and polysaccharides—is highly dynamic and responsive to external stresses. Analyzing this surface under non-physiological conditions (e.g., air, vacuum, or improper buffers) can induce artifacts, including protein denaturation, loss of turgor pressure, and rearrangement of surface molecules, ultimately leading to erroneous data [30] [12].

Advanced techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and its application in CFM offer the unique capability to probe live cells under physiological liquids, providing topographical, nanomechanical, and chemical information with unprecedented resolution [10] [12]. The integrity of this data is inextricably linked to the preservation of the cell's native state from the moment of harvesting to the final measurement. The following sections outline the core principles, protocols, and tools to achieve this goal.

Core Principles for Preserving Native States

Adherence to several core principles is non-negotiable for meaningful CFM data:

- Liquid Environment: All imaging and force measurements must be performed in an appropriate aqueous buffer (e.g., PBS, MOPS) to maintain cell viability, membrane integrity, and protein function [12].

- Physiological Buffers and Temperature: The pH, ionic strength, and osmolarity of the buffer must match the microbe's natural habitat. The sample stage should be equipped with a temperature controller to maintain optimal growth temperature where necessary.

- Minimal Sample Processing: Avoid fixation, dehydration, or metallic coating, which are common in electron microscopy but irrevocably alter native surface properties [10].

- Stable Immobilization: A prerequisite for high-resolution AFM/CFM is the firm but non-destructive immobilization of live microbial cells to a solid substrate, preventing displacement by the scanning probe but not inhibiting normal physiological processes [12].

Experimental Protocols for Native-State Analysis

Protocol: Immobilization of Live Microbial Cells for CFM

Principle: Firmly attach live cells to a solid substrate without chemical fixation, preserving membrane fluidity and surface protein functionality.

Materials:

- Microorganisms: Liquid culture of target bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli) in mid-logarithmic phase.

- Substrate: Freshly cleaved mica or glass coverslip.

- Coating Solution: 0.1% w/v Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) or Gelatin.

- Buffers: Physiological buffer (e.g., 10mM PBS, 10mM HEPES, pH 7.4).

- Equipment: AFM with liquid cell, centrifugal tube, pipettes.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Coat a clean mica surface with 100 µL of 0.1% PLL solution for 30 minutes. Rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water to remove excess PLL and air-dry.

- Cell Harvesting: Grow bacteria to mid-log phase. Harvest cells by gentle centrifugation (2,000-4,000 x g for 5 min). Resuspend the pellet gently in 1 mL of physiological buffer to remove residual growth media.

- Cell Deposition: Apply 50-100 µL of the cell suspension onto the PLL-coated mica surface. Allow cells to settle and adhere for 15-30 minutes.

- Gentle Rinsing: Carefully rinse the surface with 2-3 mL of physiological buffer to remove loosely attached cells. Avoid forceful streaming.

- AFM/CFM Setup: Immediately mount the sample into the AFM liquid cell and submerge in the appropriate physiological buffer. Begin imaging or force spectroscopy within 30 minutes of preparation.

Protocol: Chemical Force Microscopy with Functionalized Tips

Principle: Use AFM tips chemically modified with specific functional groups (e.g., -CH3, -COOH, -NH2) or biomolecules to map chemical heterogeneity and receptor-ligand interactions on the native microbial surface.

Materials:

- AFM Probes: Silicon nitride cantilevers (spring constant: ~0.01-0.10 N/m).

- Functionalization Reagents: Silane or thiol chemistry kits for tip modification with desired functional groups or biomolecules (e.g., lectins, antibodies).

- Liquid Cell: Sealed AFM liquid cell.

Procedure:

- Tip Functionalization: Following established protocols, chemically modify the AFM tips with the desired functional group or biomolecule. Validate the modification by measuring adhesion forces on reference surfaces.

- System Calibration: Calibrate the cantilever's spring constant and the photodetector's sensitivity in liquid.

- Topographical Imaging: First, acquire a high-resolution topographical image of the cell surface in buffer using standard contact or tapping mode.

- Force Volume Mapping: On a selected region of interest, perform a force volume map. This involves recording force-distance curves at each pixel in a 2D grid.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the force curves to extract parameters such as adhesion force, rupture events, and elasticity (Young's modulus). Correlate these maps with the topographical image to link structure with chemical and mechanical properties.

Table 1: Summary of AFM Operational Parameters for Microbial Cell Analysis under Physiological Conditions

| Parameter | Typical Range | Significance for Native State Preservation |

|---|---|---|

| Scanning Medium | Liquid (Physiological Buffer) | Prevents dehydration, maintains membrane fluidity and protein function [12]. |

| Cantilever Spring Constant | 0.01 - 0.10 N/m | Minimizes applied force, preventing cell damage or indentation [12]. |

| Imaging Mode | Contact, Tapping (AC), or PeakForce Tapping | Tapping modes reduce lateral forces, minimizing cell displacement. |

| Applied Force | < 500 pN | Crucial for non-destructive imaging and accurate nanomechanical property measurement. |

| Lateral Resolution | < 1 nm (sub-nanometer achievable) | Resolves individual membrane proteins and fine structures like flagella [10]. |

| Vertical Resolution | ~0.1 nm | Allows tracking of dynamic surface changes in real-time. |

Table 2: Impact of Non-Physiological Conditions on Microbial Surface Properties

| Condition | Effect on Microbial Surface | Consequence for CFM Data |

|---|---|---|

| Air Drying | Collapse of surface structures, protein denaturation, loss of turgor pressure. | Overestimated stiffness, loss of chemical recognition, distorted topography [12]. |

| Chemical Fixation | Cross-linking of surface molecules, altered nanomechanics. | Artificially high Young's modulus, loss of dynamic information, potential masking of epitopes. |

| Non-physiological Buffer | Altered osmolarity can cause cell shrinkage or swelling; incorrect pH can denature proteins. | Changes in cell volume and morphology, unreliable adhesion and mechanical measurements. |

| Excessive Imaging Force | Physical damage to the cell wall and membrane. | Scratches in images, unrepresentative force curves, cell death. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Native-State Microbial CFM

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Poly-L-Lysine (PLL) | A cationic polymer used to coat substrates (mica/glass) to electrostatically immobilize negatively charged microbial cells [12]. |

| Porous Membrane Filters | Used in physical entrapment methods, where cells are trapped by a filter, allowing buffer exchange while keeping cells immobilized [12]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | A soft elastomer used to create microfluidic chips or microwells for cell immobilization and long-term live-cell studies under flow conditions. |

| Functionalized AFM Probes | Tips modified with specific chemical groups (-CH3, -COOH, -NH2) or biomolecules (antibodies, lectins) to perform CFM and map chemical properties or specific interactions. |

| Silane Coupling Agents | Chemicals (e.g., APTES) used to create a self-assembled monolayer on AFM tips and substrates, providing a reactive interface for further functionalization. |

Workflow Visualization

Probing the Microbial Surface: CFM Techniques and Applications in Drug Discovery

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS) for Receptor-Ligand Binding Affinity

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy (SMFS) with the Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) provides molecular-level insights into protein function by allowing researchers to reconstruct energy landscapes and understand functional mechanisms in biology [31]. This technique has greatly accelerated our understanding of force transduction, mechanical deformation, and mechanostability within receptor-ligand complexes by directly probing structural changes of macromolecules under the influence of mechanical force [31]. In the context of microbial surface properties research, SMFS enables the quantification of binding strengths and kinetics between receptors and ligands, revealing how mechanical forces modulate these interactions in physiologically relevant conditions.

The fundamental principle involves applying controlled mechanical forces to individual receptor-ligand complexes and measuring the resulting rupture forces and unfolding patterns. Conceptually, the application of mechanical force tilts the underlying free energy landscape of a biomolecule, forcing it to sample conformations along a specific reaction coordinate in an accelerated manner [31]. This allows researchers to observe conformational changes and reactions that might otherwise be too slow to observe experimentally, and to quantify discrete states of a molecule that may be transient in the absence of force but biologically relevant nonetheless.

Quantitative Data on Receptor-Ligand Interactions by SMFS

SMFS provides direct measurements of binding strengths and mechanical properties of receptor-ligand complexes. The tables below summarize key quantitative parameters obtained from recent SMFS studies on various biological systems.

Table 1: Experimentally Measured Rupture Forces and Binding Parameters

| Receptor-Ligand System | Rupture Force (pN) | Experimental Conditions | Binding Affinity/Dissociation Constant | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 RBD - Integrin αvβ6 | Exceeds ACE2-RBD binding force | Single-molecule force spectroscopy, cation-dependent | Strong binding, supports αvβ6 as alternative receptor | [32] |

| Gelsolin Domain 6 (G6) - Calcium ions | 23.9 ± 6.1 (calcium-free) to 41.0 ± 6.1 (calcium-bound) | AFM-SMFS with (GB1-G6)4 polyprotein, saturating [Ca²⁺] = 50 μM | Force-enhanced binding; Kd decreases exponentially with force | [33] |

| HA-β2-AR - Anti-HA antibody | 61.7 ± 18.9 (specific binding) | AFM with anti-HA-dendritip on living WTT-CHO cells | Specific binding >40 pN; 44% adhesive events in expressing cells vs 18% controls | [34] |

| Folate Receptor - Folate ligand | Multiple binding forces detected | Multiple molecule force spectroscopy (MMFS) with functionalized microsphere probe | Distribution varies by cell type and membrane region | [35] |

Table 2: SMFS Experimental Parameters and Analytical Outputs

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Parameters | Spontaneous unfolding rates (k₀), unfolding distance (Δxᵤ) | Reveals energy landscape, transition states, and mechanical stability |

| Thermodynamic Parameters | Dissociation constant (Kd), free energy changes (ΔG) | Quantifies binding affinity and its force dependence |

| Spatial Distribution | Receptor density, clustering patterns, membrane localization | Relates to signaling efficiency, cooperativity, and cellular response |

| Force Dependency | Rupture force distributions, loading rate dependence | Characterizes energy landscape topography and biological functionality |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SMFS with Engineered Polyproteins for Ligand Binding Studies

This protocol is adapted from studies on force-dependent calcium binding to gelsolin [33] and can be generalized for various receptor-ligand systems.

Materials and Reagents:

- Engineered polyprotein (e.g., (GB1-G6)₄ for calcium binding studies)

- Functionalized AFM cantilevers

- Appropriate buffer systems with controlled cation concentrations

- Purified receptor and ligand components

Procedure:

Polyprotein Engineering: Construct a polyprotein where the receptor domain of interest alternates with a mechanically stable fingerprint protein (e.g., GB1). This design allows unambiguous identification of receptor unfolding events within the force-extension curve [33].

Sample Immobilization: Sparsely adsorb the polyprotein onto a clean gold or mica surface to achieve a monolayer with isolated molecules.

Cantilever Functionalization: Use standard aldehyde-dendrimer chemistry to functionalize AFM cantilevers for specific pickup of polyproteins.

Force Spectroscopy Measurements:

- Approach the functionalized cantilever to the surface with a contact force of 0.5-1 nN and a contact time of 200-500 ms.

- Retract the cantilever at constant velocity (typically 100-1000 nm/s) while recording force-distance curves.

- Repeat for thousands of approach-retract cycles to acquire sufficient statistical data.

Ligand Concentration Studies: Perform measurements across a range of ligand concentrations (e.g., 0-50 μM Ca²⁺ for gelsolin studies) to obtain binding isotherms [33].

Data Collection Criteria: Include only force-extension curves showing the characteristic sawtooth pattern with the fingerprint protein's unfolding signature, ensuring single-molecule stretching events.

Protocol 2: SMFS on Living Cells for Receptor Mapping

This protocol enables direct measurement of receptor distribution and unfolding on living cell surfaces, adapted from GPCR architecture studies [34] and receptor distribution analysis [35].

Materials and Reagents:

- Adherent mammalian cells expressing target receptor with extracellular tag

- Anti-HA antibodies for receptor recognition (for HA-tagged receptors)

- Amino-modified silica microspheres (10 μm diameter)

- UV-curable adhesive

- Appropriate cell culture media and buffers

Procedure:

Probe Preparation:

- Attach amino-modified silica microsphere to AFM tip cantilever using UV-curable adhesive [35].

- Conjugate specific ligands (e.g., folate, EGF) or antibodies (e.g., anti-HA) to the microsphere via carboxyl-amine chemistry.

Cell Preparation:

- Culture adherent cells (e.g., WTT-CHO, HeLa, A549) expressing tagged receptors to appropriate confluence.

- Confirm receptor expression and function through ELISA and functional assays (e.g., cAMP production for β2-AR) [34].

SMFS Measurement on Cells:

- Approach the functionalized probe to the cell surface with maximal applied force of 0.5 nN and contact time of 200 ms.

- Retract at constant velocity while recording force-distance curves.

- Conduct serial approach-withdrawal cycles while scanning a 3 × 3 μm² area at the cell surface.

Specificity Controls: Include control cells lacking receptor expression to quantify non-specific adhesion (typically <20% of events) [34].

Spatial Mapping: Resolve the spatial arrangement of adhesive events (specific receptor unfoldings) and non-adhesive events across the scanned area.

Real-time Monitoring: For dynamic studies, introduce pharmacological regulators (e.g., hyaluronic acid with different disaccharide units) and monitor receptor distribution changes over time [35].

Data Analysis:

- Manually measure the distance between the contact point and the point of lowest force on each retraction curve.

- Apply mixed Gaussian distribution analysis using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for model selection.

- Correlate population means with theoretical lengths of receptor monomers and oligomers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for SMFS Binding Studies

| Category | Specific Item | Function and Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFM Components | Functionalizable cantilevers | Force sensing and application | Various spring constants (10-100 pN/nm) |

| Aldehyde-dendrimer chemistry | Tip functionalization for specific binding | Enables covalent antibody attachment [34] | |

| Protein Engineering | Fingerprint proteins | Internal control for identification | GB1 domain (unfolds at ~150 pN, ΔLc ~18 nm) [33] |

| Polyprotein constructs | Controlled mechanical loading | (GB1-Receptor)₄ design for unambiguous unfolding [33] | |

| Cell Culture | Tagged receptor constructs | Specific recognition and detection | HA-tagged β2-AR, mGlu3-R [34] |

| Cell lines with varied receptor expression | Comparative distribution studies | HeLa, A549, Vero cells [35] | |

| Ligand Binding | Silica microspheres | Multiple molecule force spectroscopy | 10 μm amino-modified spheres [35] |

| Specific ligands | Receptor targeting and binding studies | Folate, EGF, calcium ions [33] [35] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Force-Distance Curve Analysis

SMFS data appears as force-extension curves featuring characteristic sawtooth patterns for polyproteins or complex unfolding signatures for cellular receptors. Each unfolding event appears as a peak where the force drops abruptly, representing the rupture of a single receptor-ligand bond or protein domain unfolding.

Key Analytical Steps:

Worm-Like Chain (WLC) Fitting: Fit individual unfolding peaks using the WLC model of polymer elasticity to obtain contour length increments (ΔLc), which should match theoretical values for the unfolded domain [33].