Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Viability Methods: From Classic Culturability to Advanced Molecular Assays

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of bacterial viability assessment methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Viability Methods: From Classic Culturability to Advanced Molecular Assays

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of bacterial viability assessment methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles defining bacterial viability, including the established triumvirate of culturability, metabolic activity, and membrane integrity. The review details a wide array of methodological approaches, from traditional plating and dye-based assays to cutting-edge techniques like viability PCR, flow cytometry, and laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry. Practical guidance on troubleshooting common pitfalls and optimizing protocols for specific applications is provided. Finally, a rigorous validation and comparative analysis equips readers with the knowledge to select the most appropriate, accurate, and efficient method for their specific research or diagnostic context, from antimicrobial susceptibility testing to probiotic enumeration.

Defining Bacterial Viability: Beyond Culturability to Metabolic and Membrane Integrity

In microbiology and drug development, accurately determining whether a bacterial cell is viable is fundamental to assessing infectious risks, evaluating antibiotic efficacy, and ensuring product safety. The concept of viability is multifaceted, resting on three widely accepted pillars: culturability, metabolic activity, and membrane integrity [1] [2]. Each pillar probes a different aspect of cellular life, from the ability to reproduce to the maintenance of basic physiological functions and structural barriers. No single method provides a complete picture, as cells can exist in states such as the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, where they are metabolically active but cannot form colonies on standard media [1] [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the methods underpinning these three pillars, summarizing their principles, applications, and limitations to aid researchers in selecting the most fit-for-purpose assays.

The Three Pillars: Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

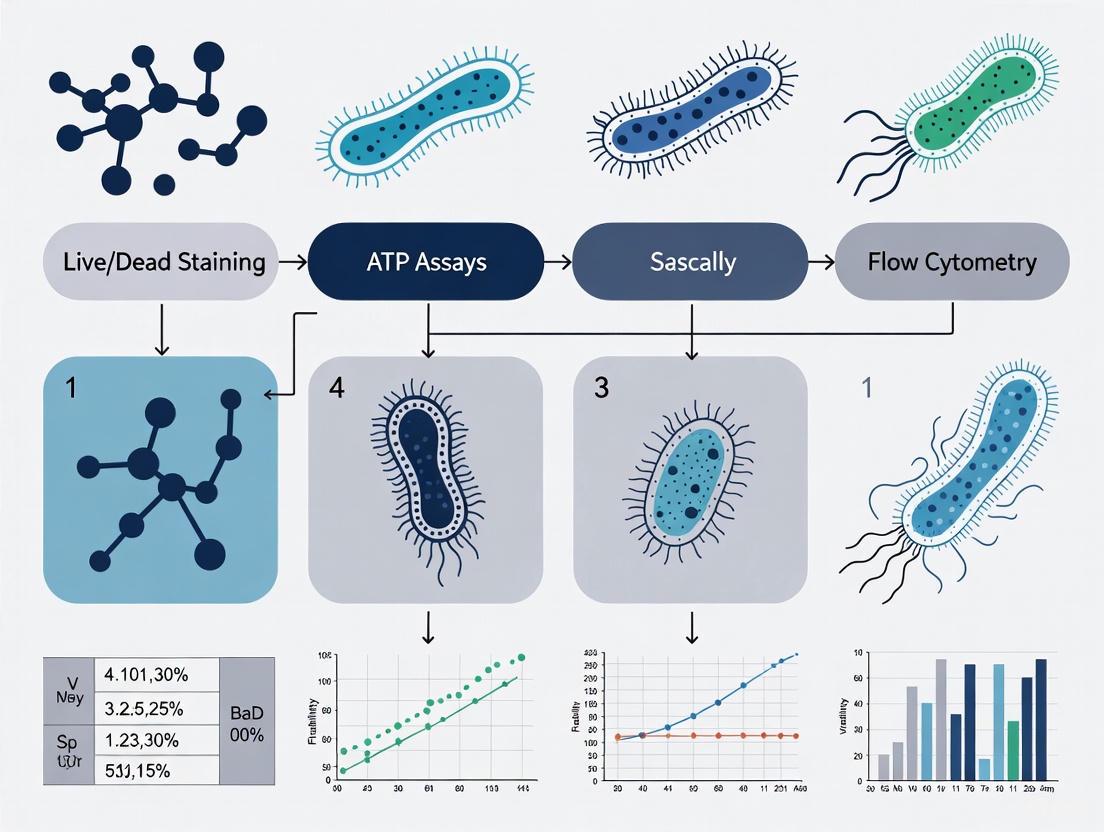

Viability assessment strategies are categorized based on which of the three core criteria they measure. The following table provides a high-level comparison of these foundational approaches.

Table 1: Core Principles and Characteristics of the Three Pillars of Viability Assessment

| Assessment Pillar | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culturability | Measures the ability of a single cell to grow and form a visible colony on solid media [1]. | Considered the historical "gold standard"; provides definitive proof of reproductive capacity [4] [5]. | Cannot detect VBNC cells, which are alive but do not divide on standard media [1] [2]. |

| Metabolic Activity | Probes the presence of ongoing biochemical processes, such as enzyme activity or substrate uptake [1] [6]. | Can detect VBNC cells that are still metabolically active [1]. | Dormant cells with silenced metabolism may give false-negative results; results can be sensitive to assay conditions (e.g., pH) [1] [6]. |

| Membrane Integrity | Assesses the physical intactness of the cell membrane, a key feature of living cells [1] [7]. | Directly measures a fundamental characteristic of life; can detect some viable cells that are non-culturable and metabolically dormant [1] [8]. | A temporarily compromised membrane may be repaired, and membrane integrity alone does not guarantee replicative capacity [7]. |

The relationship between these pillars and the cellular states they detect can be visualized as a series of nested subsets. The population with intact membranes is the broadest, encompassing all cells considered viable by this structural definition. Within this group exists a subset of cells with active metabolism, which, in turn, contains the subset of cells capable of replication on culture media [1].

Comparative Method Performance: Data and Protocols

A deeper understanding of these pillars requires examining the specific methods that operationalize them. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for representative assays from each category.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Representative Viability Assessment Methods

| Method (Pillar) | Dynamic Range (CFU/mL) | Time to Result | Key Measurand / Reagent | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate Culture (Culturability) [5] | 1 - 10^8 | 1 - 7 days | Growth on solid agar media | Low |

| Geometric Viability Assay - GVA (Culturability) [5] | 1 - 10^6 | ~1 day | Colony distribution in a pipette tip | High (≈1,200/day) |

| Flow Cytometry with Viability Dyes (Membrane Integrity) [9] | 10^4 - 10^7 | Minutes to hours | SYTOX Green, Propidium Iodide | Very High |

| Tetrazolium Salt Reduction (e.g., CTC, MTT) (Metabolic Activity) [6] | Varies | 1 - 4 hours | Tetrazolium salt → Formazan | Medium |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) Hydrolysis (Metabolic Activity) [1] | Varies | 30 mins - 2 hours | FDA → Fluorescein | Medium |

| Viability PCR (vPCR) (Membrane Integrity) [4] | Varies | 3 - 6 hours | DNA intercalating dyes (e.g., PMA) | Medium |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, below are detailed protocols for one innovative method from each pillar.

Protocol: Geometric Viability Assay (GVA) for Culturability

GVA is a high-throughput method that calculates viable counts based on the geometric distribution of colonies forming inside a pipette tip, effectively creating a dilution series in a single step [5].

- Sample Preparation: Mix the bacterial sample thoroughly with melted LB agarose (cooled to ≤55°C) to a final agarose concentration of 0.5%. Include triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) in the agarose to enhance colony contrast.

- Loading and Solidification: Aspirate the sample-agarose mixture into a standard pipette tip. Allow the agarose to solidify completely at room temperature.

- Incubation: Eject the solidified agarose tip into an empty, sterile tip rack. Incubate the entire rack overnight at the microbe's optimal growth temperature (e.g., 37°C for E. coli).

- Imaging and Analysis: Image the tip using a custom optical setup or a standard gel documentation system. Manually or automatically record the position of each colony along the tip's long axis (x-coordinate).

- Calculation: Compute the CFU concentration using the formula:

CFU/mL = N / ( V * ∫ PDF(x) dx )whereNis the number of colonies counted in a segment,Vis the volume of the tip, andPDF(x)is the probability density function(3x²/h³), withhbeing the total length of the tip [5].

Protocol: Flow Cytometry with SYTOX Green for Membrane Integrity

This protocol uses the nucleic acid stain SYTOX Green, which penetrates only cells with compromised membranes, providing a count of dead cells within a heterogeneous population [9].

- Stain Preparation: Prepare a working solution of SYTOX Green dye in an appropriate buffer (e.g., DMSO or water) as per manufacturer instructions.

- Staining: Mix the bacterial sample with the SYTOX Green solution to achieve the recommended final concentration (e.g., 1 µM). Incubate the mixture in the dark for 10-15 minutes at room temperature.

- Instrument Setup: Power on the flow cytometer and set up the instrument for microbial analysis. Create a plot of green fluorescence (e.g., FITC or GFP channel, ~530 nm) versus side scatter (SSC).

- Thresholding and Gating: Run an unstained control to set the background fluorescence and define a gate for the total population. Run the stained sample and establish a gate for the SYTOX Green-positive (dead) population based on a significant increase in green fluorescence.

- Acquisition and Analysis: Acquire events for all test samples at a stable flow rate. The viable cell count is determined as the difference between the total cell count and the SYTOX Green-positive count [9].

Protocol: Tetrazolium Salt Reduction (CTC) for Metabolic Activity

This assay measures the activity of the electron transport system by reducing a colorless tetrazolium salt (CTC) to a fluorescent, insoluble formazan precipitate inside metabolically active cells [6].

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of 5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride (CTC) in deionized water or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Filter-sterilize.

- Staining and Incubation: Add the CTC solution to the bacterial sample to a final concentration typically between 2-5 mM. Incubate in the dark for 60-90 minutes at the optimal growth temperature.

- Fixation (Optional): If necessary, fix the cells with a low concentration of formaldehyde (e.g., 1.5-4%) to preserve the signal.

- Microscopy or Extraction: Analyze the cells directly under an epifluorescence microscope (excitation ~450-490 nm, emission >600 nm) to count red-fluorescent cells. Alternatively, for quantification, extract the insoluble formazan with an organic solvent (e.g., ethanol or acetone) and measure the absorbance spectrophotometrically [6].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of viability assays depends on key reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Bacterial Viability Assessment

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Viability Pillar | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triphenyl Tetrazolium Chloride (TTC) | Incorporated into growth media; reduced by metabolically active cells to a red formazan, visualizing colonies [5]. | Culturability | Enhances contrast for automated colony counting in assays like GVA. |

| SYTOX Green | Membrane-impermeant nucleic acid stain that enters only dead cells with compromised membranes, producing green fluorescence [9]. | Membrane Integrity | Requires flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy for detection. |

| Tetrazolium Salts (e.g., CTC, XTT, MTT) | Act as electron acceptors; reduced by metabolically active cells to colored formazan products [6]. | Metabolic Activity | Some salts (e.g., CTC) can be toxic to certain bacteria; product solubility (soluble vs. insoluble) varies. |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | Cell-permeant esterase substrate; cleaved by intracellular enzymes to release fluorescent fluorescein in live cells [1]. | Metabolic Activity | Signal is highly sensitive to intracellular pH and can leak from cells. |

| Proliferation Dyes (e.g., WST-8) | Water-soluble tetrazolium salts reduced by cellular dehydrogenases to a water-soluble formazan, allowing colorimetric reading [4]. | Metabolic Activity | Suitable for high-throughput microplate assays. |

| Viability PCR Reagents (e.g., PMA dyes) | DNA intercalating dyes that selectively enter dead cells; upon photoactivation, they crosslink to DNA and inhibit its PCR amplification [4]. | Membrane Integrity | Allows PCR to target only intact (viable) cells; requires optimization of light exposure. |

The comparative analysis of culturability, metabolic activity, and membrane integrity reveals that no single pillar is universally superior. The choice of assay must be driven by the specific research question. For determining reproductive capacity, culturability-based methods like the classic plate count or the innovative GVA remain definitive. For rapid, high-throughput screening of cell status, particularly in complex samples like multi-species probiotics, flow cytometry-based membrane integrity assays are powerful. Metabolic activity assays offer a glimpse into the physiological state between replication and death, crucial for identifying VBNC populations. A comprehensive understanding of bacterial viability often necessitates a multi-faceted approach, leveraging the complementary strengths of these three fundamental pillars.

The Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) state represents a dormant survival strategy adopted by numerous bacterial species when facing environmental stress. First identified in 1982 and formally termed in 1985, this state is defined by a temporary loss of culturability on routine laboratory media while bacteria maintain viability, metabolic activity, and potential pathogenicity [10] [11]. VBNC cells cannot form visible colonies on standard agar plates, rendering them undetectable by conventional culture-based methods that form the cornerstone of microbiological testing in clinical, food safety, and public health laboratories worldwide [11] [12]. This fundamental detection gap creates a significant blind spot in public health protection, allowing pathogenic bacteria to evade surveillance systems and established control measures.

The public health implications of the VBNC state are profound and multifaceted. Numerous human pathogens can enter this dormant state, including Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Vibrio cholerae, Helicobacter pylori, and Klebsiella pneumoniae [11] [13] [14]. When in the VBNC state, these pathogens often exhibit enhanced resistance to antibiotics, disinfectants, and environmental stresses, complicating treatment and eradication efforts [10] [11]. Perhaps most concerning is their ability to resuscitate under favorable conditions, potentially leading to silent transmission, recurrent infections, and unexplained disease outbreaks that defy conventional epidemiological investigation [11] [15]. The systematic failure to detect VBNC pathogens consequently undermines the effectiveness of microbiological monitoring programs across healthcare, food production, and water safety sectors, creating unrecognized reservoirs of infectious agents that threaten public health.

Comparative Analysis of VBNC Detection Methods

The accurate identification of VBNC bacteria requires a paradigm shift from growth-based detection to methodologies that probe viability through alternative metrics. Current approaches focus on distinguishing viable cells (with intact membranes and metabolic activity) from both culturable and dead cells, creating a analytical challenge that no single method perfectly addresses. The optimal choice depends on required sensitivity, sample matrix, equipment availability, and whether qualitative detection or absolute quantification is needed.

Table 1: Comparison of Major VBNC Detection Methodologies

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Detection Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Reported Sensitivity/Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Viability Assays | PMA/dPCR combined (PMA-dPCR) | Inhibits DNA amplification from membrane-compromised cells; absolute quantification via microfluidic partitioning | Absolute quantification without standard curves; high sensitivity; resistant to PCR inhibitors | Requires optimization of PMA concentration; higher cost; specialized equipment | Absolute quantification of VBNC K. pneumoniae; 1.13-0.64 log10 reduction detection [14] |

| Molecular Viability Assays | PMAxx/EMA-qPCR combined | Dual dye approach improves exclusion of dead cells with intact membranes | Better dead cell exclusion than single dyes; applicable to complex matrices | Requires extensive validation for specific matrices; may overestimate VBNC cells | Effective detection in chlorine-treated process wash water [16] |

| Molecular Viability Assays | mRNA-based RT-qPCR | Detects labile mRNA transcripts indicating active metabolism | Direct evidence of metabolic activity; high specificity | mRNA instability requires rapid processing; technically challenging | Correlates with viability through essential gene expression (16S rDNA, rpoS) [17] |

| Cellular Viability Staining | Live/Dead staining with flow cytometry | Membrane integrity assessment using fluorescent dyes (SYTO9/PI) | Rapid results; visual confirmation; distinguishes intact/damaged membranes | Overestimation in complex matrices; equipment-dependent | Not suitable for complex wash water due to interference [16] |

| Cellular Viability Staining | ATP assays | Measures cellular ATP levels as indicator of metabolic activity | Direct metabolic measurement; rapid results | Does not distinguish VBNC from active cells; affected by extracellular ATP | High ATP in L. monocytogenes after one year in VBNC state [11] |

| Advanced Imaging | AI-enabled hyperspectral microscopy | Detects spectral signatures of VBNC cells using deep learning | Label-free; high specificity; visual validation | Specialized equipment; AI model training required | 97.1% accuracy for VBNC E. coli classification [18] |

Methodological Insights and Performance Gaps

The comparative analysis reveals a critical trade-off between methodological complexity and detection reliability. While culture-based methods remain the gold standard for detecting culturable pathogens, they completely fail to identify VBNC populations, creating a significant analytical gap [11] [12]. Molecular methods like PMA-PCR have emerged as the most practical compromise, offering reasonable sensitivity while accommodating the sample throughput needs of public health laboratories. However, even these advanced methods struggle with complete discrimination between VBNC and dead cells, particularly in complex matrices like food or environmental samples [16]. The emerging generation of technologies—particularly AI-enabled hyperspectral imaging and digital PCR—promises enhanced accuracy but requires specialized instrumentation currently unavailable in most routine laboratory settings [18] [14].

Experimental Protocols for VBNC Research

VBNC Induction and Validation Protocol

Research into the VBNC state requires standardized approaches for inducing, detecting, and quantifying this dormant population. The following integrated protocol synthesizes methodologies from multiple recent studies:

Induction Conditions:

- Starvation stress: Suspend bacteria in minimal media or artificial seawater (ASW) at 4°C for extended periods (days to weeks) [14]. For K. pneumoniae, incubation in ASW at 4°C for 50 days successfully induced the VBNC state [14].

- Chemical stressors: Expose to sublethal concentrations of disinfectants (e.g., 10 mg/L chlorine), household cleaners with non-ionic surfactants, or oxidative agents (0.01% hydrogen peroxide) [16] [18] [15]. Gram-positive bacteria like Listeria monocytogenes show particular susceptibility to VBNC induction by non-ionic surfactants combined with salts [15].

- Physical stresses: Apply temperature extremes, UV radiation, or high pressure treatments at sublethal intensities [11].

Confirmation of VBNC State:

- Culturability assessment: Plate on appropriate non-selective media; true VBNC states show no colony formation after prolonged incubation [14].

- Membrane integrity: Apply LIVE/DEAD BacLight staining (SYTO9/PI) - VBNC cells display green fluorescence indicating intact membranes [17] [15].

- Metabolic activity: Measure ATP production or use tetrazolium salts; VBNC cells maintain low but detectable metabolic activity [11] [15].

- Molecular confirmation: Use PMA-qPCR to verify presence of intact cells while ruling out culturable populations [16].

Viability PCR with PMAxx/EMA Treatment Protocol

The combination of viability dyes with quantitative PCR represents one of the most practical approaches for VBNC detection in complex matrices. The following optimized protocol from food safety research enables discrimination between VBNC and dead cells in process wash water [16]:

Reagent Preparation:

- Prepare stock solutions of PMAxx (1 mM) and EMA (1 mM) in distilled water

- Prepare phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for sample dilution

- Have sodium thiosulfate pentahydrate (0.3 M) available for chlorine neutralization if needed

Sample Processing:

- Concentrate bacterial cells from sample matrix by centrifugation (2,500 × g for 5 min)

- Resuspend pellet in PBS to desired concentration (approximately 10⁵ CFU/mL)

- Add PMAxx and EMA to final concentrations of 75 μM and 10 μM respectively

- Incubate in the dark at 40°C for 40 minutes with occasional mixing

- Place samples on ice and photoactivate for 15 minutes using a 650W halogen light source at 20cm distance

- Extract genomic DNA using commercial kits (e.g., Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit)

qPCR Analysis:

- Prepare reaction mix with appropriate primers and probe sets for target pathogen

- Use single-copy essential genes (rpoB, adhE) as targets for quantification

- Include no-dye controls to assess total bacterial DNA

- Include killed cell controls to validate dye penetration efficiency

- Run quantification cycle (Cq) comparison between dyed and non-dyed samples

Validation:

- The method should inhibit >99% of DNA amplification from dead cells

- Specificity should be confirmed using target pathogens in relevant food matrices

- The limit of detection typically ranges 10²-10³ gene copies/mL depending on the matrix

Research Reagent Solutions for VBNC Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for VBNC Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Dyes | PMA, PMAxx, EMA | Differentiation of membrane-intact cells in molecular assays | PMAxx shows improved dead cell exclusion vs. PMA; EMA may penetrate some viable cells [16] |

| Viability Dyes | LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit (SYTO9/PI) | Membrane integrity assessment via fluorescence microscopy/flow cytometry | Green fluorescence (SYTO9) indicates intact membranes; red fluorescence (PI) indicates compromised membranes [17] [15] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit | Isolation of amplifiable DNA from complex samples | Consistent yield crucial for molecular quantification; must remove PCR inhibitors [14] |

| PCR Reagents | Premix Ex Taq, specific primers/probes | Quantitative detection of viable pathogens | Target single-copy essential genes (rpoB, adhE, 16S rDNA) for accurate quantification [14] |

| Culture Media | Brain Heart Infusion (BHI), LB broth, ASW | Induction and resuscitation studies | Nutrient deprivation in ASW induces VBNC; rich media (BHI) may support resuscitation [14] [15] |

| Induction Agents | Hydrogen peroxide, peracetic acid, chlorine, surfactants | Controlled VBNC state induction | Sublethal concentrations critical; surfactants + salts particularly effective for Gram-positives [18] [15] |

Practical Implementation Considerations

The selection of appropriate reagents fundamentally influences the reliability of VBNC detection assays. Viability dyes require extensive validation for each bacterial species and matrix combination, as penetration efficiency varies significantly [16]. For molecular detection, targeting multiple single-copy genes (e.g., rpoB, adhE) provides more reliable quantification than single targets, reducing variability from potential gene copy number fluctuations [14]. When inducing VBNC states experimentally, combining multiple mild stresses often more closely mimics environmental conditions than single intense stressors, potentially yielding more physiologically relevant VBNC populations [15].

The VBNC state represents a significant challenge to conventional microbiological paradigms and public health protection systems. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that while no perfect detection method exists, integrated approaches combining viability dyes with molecular detection currently offer the most practical solution for identifying these elusive pathogens. The persistence of VBNC bacteria across clinical, food production, and environmental settings necessitates a fundamental re-evaluation of current microbiological monitoring programs that remain dependent on culture-based methods.

Future directions in VBNC research should focus on standardizing detection protocols across sectors, developing cost-effective rapid methods deployable in resource-limited settings, and elucidating the genetic mechanisms controlling entry into and resuscitation from the VBNC state. Particularly promising are technologies enabling single-cell analysis of VBNC populations, which could reveal heterogeneity within dormant communities and identify key resuscitation triggers. Additionally, epidemiological studies correlating VBNC detection with public health outcomes would strengthen the evidence base for incorporating these advanced detection methods into routine surveillance.

As our understanding of bacterial dormancy deepens, integrating VBNC detection into public health practice will be essential for addressing persistent challenges in infectious disease control, food safety assurance, and water quality monitoring. The methodological framework presented here provides a foundation for developing more comprehensive pathogen surveillance systems capable of detecting both active and dormant threats to public health.

Metabolic dormancy represents a fundamental survival strategy across biological kingdoms, from microorganisms to human cancer cells. This state of reduced metabolic activity allows cells to persist under unfavorable conditions, such as nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, or chemical stress, by entering a temporary period of quiescence [19]. In microbiology, most microorganisms in natural environments exist in dormant rather than growing states, challenging the growth-centric paradigm that has traditionally dominated the field [20]. Similarly, in oncology, dormant cancer cells can enter a resting phase (G0/G1 phase) that complicates treatment and increases the risk of cancer recurrence years or even decades after initial therapy [19] [21].

Understanding metabolic dormancy is crucial for multiple disciplines. For environmental and medical microbiologists, it explains how pathogens evade antimicrobial treatments and how microbial communities maintain ecosystem services during starvation. For cancer researchers, it reveals mechanisms behind therapeutic resistance and metastatic relapse. This comparative guide examines the principles, assessment methods, and experimental approaches for studying metabolic dormancy, providing researchers with the tools to investigate this complex phenomenon across biological systems.

Fundamental Principles of Metabolic Dormancy

Defining Characteristics and Types

Metabolic dormancy encompasses several distinct but related states characterized by reduced metabolic activity, reversible cell cycle arrest, and enhanced stress resistance. In microbiology, the viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state describes bacteria that remain metabolically active but cannot proliferate on standard laboratory media, often entering a dormant state when faced with unfavorable conditions like low temperatures, low-nutrient environments, and high antibiotic concentrations [1]. In cancer biology, tumor dormancy occurs when disseminated cancer cells enter cellular quiescence, remaining viable but non-proliferative for extended periods before potentially reactivating to cause disease recurrence [21].

Three main types of dormancy mechanisms have been identified across biological systems:

Cellular Dormancy: Individual cells enter a reversible quiescent phase (G0), ceasing proliferation while maintaining viability and basal metabolic activity [21]. This state is regulated by cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p21 and p27, which halt cell cycle progression [21].

Angiogenic Dormancy: Observed in small tumor clusters, this state results from insufficient blood supply that restricts growth beyond 1-2 mm in diameter due to lack of oxygen and nutrients [21].

Immunological Dormancy: The immune system recognizes and contains dormant cells but cannot completely eliminate them, creating an equilibrium that prevents expansion but permits survival [21].

Metabolic Adaptations in Dormancy

Dormant cells undergo significant metabolic reprogramming to survive under resource-limited conditions. Rather than simply downregulating metabolic processes, many organisms demonstrate surprising metabolic flexibility during dormancy. For example, obligate heterotrophs can scavenge inorganic energy sources during carbon starvation, and obligate aerobes may utilize fermentation as a last resort during hypoxia [20].

Table 1: Key Metabolic Adaptations in Dormant Cells

| Adaptation Type | Microorganisms | Cancer Cells | Plant Seeds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Source | Atmospheric trace gases (H₂) [20] | Enhanced autophagy [21] | Stored carbohydrates & lipids [22] |

| Metabolic Rate | Reduced but maintained [20] | Hypometabolism [21] | Drastically reduced [22] |

| Pathway Utilization | Broadened metabolic repertoire [20] | Alternative metabolic pathways [21] | Shifted respiratory pathways [22] |

| Primary Function | Maintenance energy [20] | Survival & stress resistance [19] | Embryo preservation [22] |

A remarkable example of metabolic flexibility comes from bacteria that can "live on air" by oxidizing atmospheric trace gases like hydrogen (H₂) during carbon starvation. This process is mediated by specialized high-affinity, oxygen-tolerant [NiFe]-hydrogenases that feed electrons from H₂ oxidation into the aerobic respiratory chain [20]. Similarly, dormant cancer cells exhibit metabolic adaptations that facilitate survival during periods of low metabolic activity, including enhanced autophagy to recycle cellular components and a switch to alternative metabolic pathways to conserve energy [21].

Comparative Analysis of Viability Assessment Methods

Three Criteria for Viability Assessment

Determining the viability of dormant cells presents significant challenges, as these cells often fail to grow under standard culture conditions despite maintaining metabolic activity. Three established criteria form the basis for viability assessment in dormant populations:

- Culturability: The ability to form colonies on appropriate solid media, requiring reproducibility, metabolic activity, and intact membranes [1].

- Metabolic Activity: Measurement of biochemical processes, including substrate uptake, enzyme activity, or respiration [1] [6].

- Membrane Integrity: The maintenance of an intact membrane, typically assessed by dye exclusion assays [1].

No single method can comprehensively assess all aspects of viability in dormant cells, necessitating a multi-faceted approach. The following sections compare the major methodological categories for viability assessment.

Method Comparisons and Performance Data

Table 2: Comparison of Viability Assessment Methods for Dormant Cells

| Method Category | Specific Assay | Detection Principle | Target Dormancy State | Time Required | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culturability-Based | Plate culture [1] [23] | Colony formation | Culturable cells only | 2-7 days | Cannot detect VBNC cells |

| Metabolic Activity-Based | Dehydrogenase activity (TTC/INT reduction) [23] [6] | Respiratory chain activity | Metabolically active cells | 1-4 hours | May miss deeply dormant cells |

| Metabolic Activity-Based | Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) hydrolysis [1] [6] | Esterase/lipase activity | Cells with active enzyme systems | 20-30 minutes | Sensitive to pH variations |

| Metabolic Activity-Based | Glucose uptake (2-NBDG) [1] | Substrate transport & metabolism | Cells with active transport | 1-2 hours | Not universal among bacteria |

| Membrane Integrity-Based | Live/Dead BacLight (SYTO9/PI) [1] [23] | Membrane permeability | Cells with intact membranes | 20-30 minutes | May misclassify VBNC cells as dead |

| Membrane Integrity-Based | Flow cytometry with vital dyes [23] | Multiple membrane parameters | Population heterogeneity | 1-2 hours | Requires specialized equipment |

Table 3: Experimental Performance Comparison Following Disinfection

| Viability Assessment Method | Sensitivity After Thermal Treatment | Sensitivity After Chemical Treatment | Correlation with Colony Forming Units (CFU) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live/Dead Staining | Lower [23] | Similar to dehydrogenase assay [23] | Linear relationship [23] |

| Dehydrogenase Activity Assay | Highest [23] | Similar to staining approach [23] | Similar to colony counts [23] |

| Direct Colony Enumeration | Reference method | Reference method | Gold standard |

The performance characteristics of viability assays vary significantly depending on the inactivation method and the specific dormancy state being investigated. After thermal treatment, the sensitivity of the staining approach was lower, while that of the dehydrogenase activity assay was the highest. After chemical treatment, the sensitivity of detection for both methods was similar [23]. This highlights the importance of selecting appropriate assessment methods based on the specific experimental context and the type of dormancy under investigation.

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Live/Dead Bacterial Cell Staining Protocol

The Live/Dead BacLight bacterial viability kit utilizes two nucleic acid stains with different membrane penetration properties: SYTO9 (green fluorescence, penetrates all cells) and propidium iodide (red fluorescence, penetrates only compromised membranes) [23].

Materials:

- SYTO9 green fluorescent nucleic acid stain

- Propidium iodide (PI)

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)

- 0.85% (w/v) NaCl solution

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Confocal scanning laser microscope or fluorescence microscope

Procedure:

- Prepare the staining solution by mixing SYTO9 and PI (100 μL each) and diluting 1:10 in 0.085% NaCl solution [23].

- Add 20 μL of the staining solution to 1 mL of cell suspension [23].

- Incubate in the dark at room temperature (25°C) for 20 minutes [23].

- Remove excess dye by centrifugation at 9,450 × g for 5 minutes and discard supernatant [23].

- Resuspend cell pellets in 0.85% NaCl solution [23].

- Within 1 hour, analyze by confocal laser scanning microscopy using appropriate filters (excitation 488 nm for SYTO9, 543 nm for PI) [23].

- Quantify live (green) and dead (red) cells using image analysis software such as ImageJ [23].

Technical Considerations: This method rapidly differentiates between cells with intact and compromised membranes, but may misclassify VBNC cells with intact membranes as dead if metabolic activity is not simultaneously assessed [1].

Dehydrogenase Activity Assay Protocol

Dehydrogenase activity (DHA) measures microbial respiratory activity through the reduction of tetrazolium salts to colored formazan compounds [23] [6].

Materials:

- 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) or INT

- D-(+)-Glucose solution (1% w/v)

- Methanol (HPLC grade, chilled to -20°C)

- Phosphate buffer (pH 7.0-7.5)

- Centrifuge tubes

- UV-Visible spectrophotometer

Procedure:

- Prepare TTC stock solution (2% w/v) in sterile deionized water and filter-sterilize [23].

- Centrifuge 200 μL of bacterial suspension at 9,450 × g for 5 minutes and discard supernatant [23].

- Resuspend cell pellet in 100 μL of 1% glucose solution to provide an organic substrate [23].

- Add 20 μL of TTC stock solution and mix thoroughly [23].

- Incubate in the dark at room temperature for 1 hour [23].

- Stop the reaction by adding 1 mL of chilled methanol (-20°C) [23].

- Centrifuge to remove cells and particulate matter [6].

- Measure absorbance of the supernatant at 489 nm using a spectrophotometer [23].

- Include cell-free samples as blank controls [23].

Technical Considerations: The rate of formazan formation is proportional to the number of actively respiring cells and their metabolic activity [6]. This assay is particularly sensitive for detecting low levels of metabolic activity in dormant cells, showing the highest sensitivity after thermal treatment of samples [23].

Diagram 1: Dehydrogenase Activity Assay Workflow. This diagram illustrates the step-by-step procedure for measuring dehydrogenase activity as an indicator of metabolic activity in dormant cells.

Molecular Regulation of Dormancy

Signaling Pathways Controlling Dormancy

The transition between active proliferation and dormancy is regulated by complex signaling networks that respond to environmental and cellular cues. In cancer cells, key pathways include:

ERK/p38 MAPK Balance: The ratio of extracellular signal-regulating kinases (ERK) to p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases determines cellular fate. While ERK phosphorylation promotes proliferation, p38 phosphorylation induces cellular dormancy. A lower ERK/p38 expression ratio serves as an indicator of the dormant state [19].

PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway: Frequently dysregulated in cancer, this pathway is often downregulated in dormancy, leading to decreased protein synthesis and cell cycle arrest. Inhibition of mTOR can induce a dormancy-like state in various cancer cell lines [19] [24].

TGF-β Signaling: This multifunctional cytokine can induce and maintain quiescence during dormancy. In the bone microenvironment, TGF-β2 cooperates with all-trans retinoic acid to promote cellular dormancy characterized by growth arrest and enhanced survival [19].

Bone Morphogenetic Proteins: BMP-7, secreted by bone stromal cells, induces dormancy in prostate cancer cells via the p38 pathway and upregulation of the metastasis suppressor gene NDRG1 [19].

Diagram 2: Signaling Pathways Regulating Cellular Dormancy. This diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways that control the transition to and maintenance of dormancy in response to environmental stressors.

Metabolic Strategies in Dormant Cells

Dormant cells employ diverse metabolic strategies to maintain viability under resource-limited conditions:

Energy Conservation: Dormant cancer cells exhibit reduced metabolic activity (hypometabolism), diminished nutrient intake, and decreased reproductive capacity [21]. This hypometabolic state allows them to survive for extended periods without dividing.

Metabolic Flexibility: Bacteria demonstrate the ability to broaden their metabolic repertoire during persistence. Obligate heterotrophs can scavenge inorganic energy sources during carbon starvation, while obligate aerobes may utilize fermentation as a last resort during hypoxia [20].

Atmospheric Trace Gas Utilization: Numerous aerobic bacteria from dominant soil phyla encode high-affinity hydrogenases that allow them to oxidize atmospheric hydrogen (H₂) during carbon starvation. This process provides maintenance energy during dormancy and is particularly important in extreme environments like Antarctic dry deserts [20].

Autophagy Enhancement: Dormant cells often enhance autophagy to degrade and recycle cellular components to fulfill energy requirements during nutrient deprivation [21].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Dormancy Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Dormancy Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Stains | SYTO9 & Propidium iodide (Live/Dead BacLight) [23] | Differentiates cells based on membrane integrity | Dual staining allows simultaneous detection of live/dead populations |

| Metabolic Probes | Tetrazolium salts (TTC, INT, XTT) [23] [6] | Measures respiratory chain activity via reduction to formazan | Different tetrazolium salts vary in toxicity and penetration ability |

| Enzyme Substrates | Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) [1] | Assesses esterase/lipase activity in viable cells | pH-sensitive; requires optimization for different cell types |

| Metabolic Tracers | 2-NBDG (fluorescent glucose analog) [1] | Measures glucose uptake and metabolism | Not universally transported by all bacterial species |

| Pathway Modulators | HDAC inhibitors [24] | Induces dormancy phenotype in cancer cells | Increases Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Receptor expression |

| Cytokine Assays | IL-6 & G-CSF measurement tools [21] | Detects protumor cytokines that reactivate dormant cells | Key for understanding microenvironmental triggers of reactivation |

Metabolic dormancy represents a complex survival strategy with significant implications across microbiology, oncology, and plant biology. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that accurate assessment of dormant states requires a multifaceted approach that considers culturability, metabolic activity, and membrane integrity. No single method can fully characterize dormant populations, necessitating carefully selected method combinations based on the specific research questions and biological system.

The experimental protocols and reagent toolkit provided here offer researchers practical resources for investigating metabolic dormancy in various contexts. As research in this field advances, emerging technologies such as single-cell multi-omics, spatial transcriptomics, and advanced biomimetic models promise to unravel the intricate mechanisms governing dormancy entry, maintenance, and reactivation [24]. Understanding these processes is crucial for developing novel therapeutic strategies against persistent bacterial infections and preventing cancer recurrence, ultimately improving patient outcomes across clinical contexts.

Evaluating bacterial viability is a fundamental practice in microbiology, crucial for public health risk assessment, food safety, and pharmaceutical development [25]. Currently, viability assessment relies on three widespread and accepted criteria: culturability, metabolic activity, and membrane integrity [25]. Each criterion probes a different aspect of cellular function, and while they often correlate, significant discordance can occur due to particular physiological states. The most well-known example of such discordance is the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, where bacteria are metabolically active and possess intact membranes but cannot form colonies on standard growth media [25]. This state, induced by stress, directly challenges the gold-standard plate count method. Furthermore, dormant cells may exhibit minimal metabolic activity, leading to underestimation of viability by methods relying on that criterion [25]. Understanding the principles, advantages, and limitations of each methodological approach is therefore essential for researchers to accurately interpret viability data and select the most appropriate assay for their specific experimental context.

Comparative Analysis of Viability Assessment Methods

The following table summarizes the core principles and key characteristics of the primary viability assessment methods based on the three accepted criteria.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Bacterial Viability Assessment Methods

| Method | Underlying Principle | Viability Criterion | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Time to Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate Culture [25] | Ability of a single cell to form a visible colony on solid media. | Culturability | - Considered the gold standard- Provides quantification- Can aid in identification | - Cannot detect VBNC cells- Time-consuming (2 days to 1 week)- Labor-intensive | 2 days - 1 week |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) Assay [25] | Hydrolysis of non-fluorescent FDA by intracellular enzymes to produce fluorescent fluorescein. | Metabolic Activity | - Can detect some VBNC cells- Passive dye uptake | - Signal sensitive to intracellular pH- Fluorescein can leak from cells | 1 - 4 hours |

| 2-NBDG Uptake [25] | Uptake and decomposition of fluorescent glucose analog (2-NBDG) via active glucose transport system. | Metabolic Activity | - Can detect metabolic activity in specific cells | - Not all bacteria consume 2-NBDG- Requires fluorescent detection equipment | 1 - 4 hours |

| Geometric Viability Assay (GVA) [5] | Calculation of viable cells based on distribution of micro-colonies growing in a cone-shaped tip. | Culturability | - High throughput (≈1,200/day)- Low waste- Dynamic range (1 to 10^6 cells) | - Requires custom imaging setup- Newer method, less established | 1 - 2 days |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) Staining [7] | Dye exclusion; PI enters only cells with compromised membranes and binds to DNA. | Membrane Integrity | - Clearly identifies dead cells- Simple and fast- Compatible with flow cytometry | - Can produce false positives due to transient membrane permeabilization | 30 minutes - 2 hours |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release [7] | Measurement of cytoplasmic enzyme LDH released into supernatant upon membrane damage. | Membrane Integrity | - Easy to perform in a plate reader- Suitable for high-throughput screening | - High background in some samples- Can leak from stressed but viable cells | 1 - 4 hours |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure replicability and reproducibility, which are critical challenges in viability screening [26], the following section outlines standardized protocols for key methodologies.

Protocol: Plate Culture (Drop CFU Assay)

The plate culture method is the traditional gold standard for assessing viability based on culturability [25].

- Sample Preparation: Serially dilute the bacterial sample in a suitable sterile buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) to achieve a countable range (typically 30-300 colonies per plate).

- Plating: Spread a known volume (e.g., 100 µL) of the diluted sample onto the surface of a nutrient-rich agar plate. Alternatively, use an automated spiral plater [25].

- Incubation: Invert the plates and incubate them at the optimal temperature for the specific bacterial strain for a prescribed time (often 24-48 hours).

- Enumeration: Count the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) manually or using an automated colony counter [25]. The viable concentration (CFU/mL) is calculated using the plate volume and dilution factor.

Protocol: Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) Assay

This protocol assesses metabolic activity via nonspecific esterase activity [25].

- Dye Preparation: Prepare an FDA stock solution in a suitable solvent (e.g., acetone or DMSO) and dilute to a working concentration in buffer.

- Staining: Mix the bacterial suspension with an equal volume of the FDA working solution.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture in the dark for a predetermined time (e.g., 15-60 minutes) at the growth temperature.

- Detection and Analysis: Measure the fluorescence intensity (excitation ~490 nm, emission ~525 nm) using a fluorometer, fluorescence microplate reader, or fluorescence microscope. The signal intensity correlates with the proportion of metabolically active cells.

Protocol: Geometric Viability Assay (GVA)

GVA is a high-throughput, low-waste method that quantifies culturability within a pipette tip [5].

- Embedding: Thoroughly mix the bacterial sample with melted, cooled (≤55°C) LB agarose containing a viability indicator like triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) to a final agarose concentration of 0.5%.

- Loading: Aspirate the cell-agarose mixture into a standard pipette tip.

- Solidification: Eject the tip into a rack and allow the agarose to solidify completely.

- Incubation: Incubate the entire rack of tips overnight at the bacterium's optimal growth temperature to allow micro-colony formation.

- Imaging and Analysis: Image the tips using a custom-built optical setup. The number of viable cells in the original sample is computed based on the distribution of colonies along the longitudinal axis of the tip using a derived probability function [5].

Protocol: Membrane Integrity Staining (Propidium Iodide)

This protocol distinguishes cells with compromised membranes [7].

- Staining Solution: Prepare a working solution of propidium iodide (PI) in buffer according to manufacturer recommendations.

- Staining: Add the PI solution to the bacterial pellet or suspension at an appropriate dilution.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture for 5-15 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- Washing (Optional): Centrifuge the sample and resuspend in fresh buffer to remove excess dye, if required by the detection method.

- Detection and Analysis: Analyze the sample using fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry. PI is excited at ~535 nm and emits at ~617 nm. Cells displaying fluorescence are considered non-viable.

Visualizing Methodological Discordance and Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationship between different viability criteria and the experimental workflow for a combined viability assay, highlighting potential sources of discordance.

Diagram 1: Logic of Viability Criteria Discordance. This diagram shows how applying different viability criteria to the same bacterial population can lead to discordant results, as each method interrogates a different cellular function. Specific physiological states like VBNC, dormancy, and death explain these discrepancies.

Diagram 2: Workflow for a Combined Viability Staining Assay. This workflow demonstrates how membrane integrity and metabolic activity stains can be used simultaneously on a single sample to differentiate between subpopulations of viable, dead, and dormant/VBNC cells, providing a more comprehensive viability profile.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Selecting the appropriate reagents is fundamental to obtaining reliable viability data. The following table lists key solutions and their critical functions in the protocols described above.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viability Assessment

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function in Viability Assessment | Key Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Agar Plates | Solid growth medium to support bacterial reproduction and colony formation for culturability assays. | Selection of appropriate nutrients and incubation conditions is species-specific. |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | Cell-permeant substrate for intracellular esterases; hydrolysis yields fluorescent fluorescein indicating metabolic activity. | Signal is pH-sensitive; high intracellular concentrations can lead to quenching [25]. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | Membrane-impermeant nucleic acid stain that only fluoresces upon binding to DNA in cells with compromised membranes. | May stain viable cells with transiently permeable membranes; requires careful incubation timing [7]. |

| 2-NBDG | Fluorescent D-glucose analog taken up by cells via glucose transporters; uptake indicates active metabolism. | Not universally transported by all bacterial species (e.g., not taken up by Vibrio mimicus, Bacillus cereus) [25]. |

| Resazurin Sodium Salt | Blue, non-fluorescent dye reduced to pink, fluorescent resorufin by metabolically active cells. | Can be used in plate-based assays; prolonged incubation can lead to non-fluorescent dihydroresorufin [26]. |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay Kit | Measures the activity of LDH enzyme released from the cytoplasm of cells with damaged membranes. | Can have high background in complex samples; may leak from stressed but viable cells [7]. |

| Triphenyl Tetrazolium Chloride (TTC) | Colorimetric indicator of metabolic activity; reduced to a red, insoluble formazan compound in viable cells. | Used in GVA and other solid-phase assays to enhance colony contrast [5]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Common solvent for stock solutions of hydrophobic dyes and compounds (e.g., FDA). | Cytotoxic at high concentrations (>1%); requires matched vehicle controls in dose-response experiments [26]. |

A Toolkit of Techniques: From Plate Counts to Metabolic Monitoring and Viability PCR

For over a century, the colony-forming unit (CFU) assay has served as the gold standard for quantifying viable bacteria in microbiology. This culture-based method, rooted in the pioneering work of Robert Koch in the 1880s, relies on a simple principle: a single viable microbial cell that can proliferate on a solid culture medium will give rise to a visible colony [27]. Despite its longstanding dominance in clinical, food, and environmental microbiology, modern science has increasingly revealed significant limitations of the CFU assay, particularly its inability to detect microorganisms that resist cultivation under standard laboratory conditions [27] [1]. This comparative analysis examines the technical foundations, limitations, and emerging alternatives to CFU-based methods, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate bacterial viability assessment strategies.

The CFU Assay: Methodology and Historical Context

Experimental Protocol: Standard CFU Assay

The traditional CFU assay follows a standardized protocol that requires careful execution to generate reproducible results:

Sample Preparation and Serial Dilution: The bacterial sample is typically subjected to serial log-fold dilutions in an appropriate buffer or growth medium to reduce cell density to a countable range [5]. This step is critical as insufficient dilution results in overcrowded plates, while excessive dilution may yield no colonies.

Plating and Incubation: An aliquot of each dilution (typically 100 µL) is spread evenly across the surface of an agar plate containing appropriate nutrients, or mixed with molten agar and poured as a pour plate [1]. The plates are then incubated at optimal temperatures for the target microorganisms for a specified period (usually 24-48 hours for most bacteria, longer for slow-growing species) [1].

Enumeration and Calculation: After incubation, discrete colonies are counted manually or using automated systems. The viable count is calculated using the formula: CFU/mL = (Number of colonies counted × Dilution factor) / Volume plated [28]. Only plates containing 30-300 colonies are considered statistically valid for enumeration [29].

Historical Development

The development of cultural microbiological methods spans several key historical milestones:

- 1860s-1870s: Louis Pasteur pioneered liquid culture techniques but struggled to obtain pure cultures [27].

- 1872: Transition to solid media began with Schroeter's use of potato slices and Brefeld's introduction of gelatin as a solidifying agent [27].

- 1881-1884: Robert Koch and his team standardized the use of nutrient agar in Petri dishes, creating the foundation of modern plating techniques [27] [1].

- 1898: Winterburg first documented the discrepancy between microscopic counts and CFU, noting what would later be termed the "great plate count anomaly" [27].

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Cultural Microbiology Methods

| Time Period | Key Innovator | Contribution | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1861 | Louis Pasteur | Liquid culture media | Enabled bulk cultivation of bacteria |

| 1872 | Schroeter & Brefeld | Solid media (potato, gelatin) | Initial isolation of pure cultures |

| 1878 | Joseph Lister | Serial dilution & enumeration | First quantitative bacterial counts |

| 1881-1884 | Robert Koch | Agar plates, Petri dishes | Standardized pure culture technique |

| 1898 | Winterburg | Documented CFU limitations | First recognition of "great plate count anomaly" |

Limitations of the CFU Paradigm

The "Great Plate Count Anomaly" and Culturalility Gap

The most significant limitation of CFU-based methods is the substantial discrepancy between microscopic counts and cultivable cells, a phenomenon recognized for over a century and termed the "great plate count anomaly" by Staley and Konopka in 1985 [27]. Multiple studies have quantified this gap:

- Environmental samples: Direct microscopic counts of soil bacteria exceed plate counts by factors of 10 to 1,000, with fluorescent staining revealing even greater disparities [27].

- Aquatic environments: Marine microbiology studies show direct microscopic methods detect 10 to 10,000 times more bacteria than cultural methods [27].

- Overall microbial diversity: rRNA gene sequence analysis reveals that cultivable microorganisms represent less than 1% of those observed by direct microscopic examination in most environments, dropping to 0.1-0.01% in oceanic microbiota [27].

Technical and Methodological Limitations

Beyond the fundamental culturalility gap, CFU assays face several technical challenges:

Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) State: Many bacteria enter a VBNC state when exposed to environmental stresses (low temperatures, low-nutrient environments, high antibiotic concentrations), maintaining metabolic activity while losing culturalility [1]. These cells remain pathogenic potential but escape detection by CFU assays [1].

Selective Culturalility: Standard media and conditions favor rapidly growing microorganisms while suppressing slow-growing species, creating a biased representation of microbial communities [27]. Factors including media composition, gelling agents, pouring temperature, and incubation conditions significantly influence recovery [27].

Time and Resource Intensity: Traditional CFU enumeration requires 2-3 days for isolation and up to 1 week for complete results, limiting utility in time-sensitive applications [1]. The process also consumes significant materials (plates, media, pipettes) and personnel time [30] [5].

Colony Heterogeneity: Within individual colonies, cells exist in different physiological states due to nutrient and oxygen gradients, with the youngest cells at the margins and oldest, potentially non-viable cells at the center [27].

Diagnostic Limitations in Clinical Settings

In clinical microbiology, particularly for urinary tract infections (UTIs), reliance on standard urine culture (SUC) presents specific challenges:

- Underreporting of Polymicrobial Infections: SUC typically reports only the predominant microbe, missing potentially important co-pathogens that may influence treatment outcomes [31].

- Dichotomous Diagnosis Paradigm: The binary approach to UTI diagnosis (infected/not infected) fails to account for microbiome complexities and often mismatches patient symptoms with culture results [31].

- Antibiotic Stewardship Issues: Slow culture results (2-3 days) prolong patient suffering while waiting for antibiotic sensitivity guidance, potentially leading to inappropriate empiric therapy [31].

Emerging Alternatives to CFU Assays

Molecular-Based Viability Assessment

Molecular techniques that differentiate between live and dead cells offer promising alternatives to culture-based methods:

PMA-qPCR: Propidium monoazide (PMA) selectively penetrates membrane-compromised (dead) cells and crosslinks DNA upon light exposure, preventing amplification. Subsequent qPCR thus targets only intact (viable) cells [32] [33]. This method has been validated for quantification of viable Campylobacter in meat rinses with performance statistically similar to or better than cultural methods [32] [33].

RNA-Based Detection: mRNA detection targets metabolically active cells, as RNA degrades rapidly after cell death. Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) provides indication of viability through metabolic activity [27].

Ribosomal RNA Sequencing: 16S rRNA gene analysis enables detection and identification of non-cultivable microorganisms, revolutionizing understanding of microbial diversity in environmental and human microbiome samples [27].

Metabolic and Cytochemical Assays

Viability assessments based on metabolic activity or membrane integrity bypass the need for cultivation:

Tetrazolium Salt Reduction: Colorless tetrazolium salts (e.g., CTC, INT, XTT) are reduced to colored formazan derivatives by metabolically active cells, providing a measure of respiratory activity [6]. This method correlates with metabolic activity but may be toxic to some bacteria and is not universally applicable across species [6].

Membrane Integrity Assays: Fluorescent dyes like propidium iodide (membrane-impermeant, enters dead cells) and SYTO 9 (membrane-permeant, stains all cells) allow differential counting of live/dead cells using fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry [1].

Enzyme Activity Probes: Fluorogenic substrates (e.g., fluorescein diacetate) are hydrolyzed by intracellular enzymes in viable cells, releasing detectable fluorescent products [1] [6].

Table 2: Comparison of Bacterial Viability Assessment Methods

| Method | Basis | Detection Limit | Time Required | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFU Assay | Culturalility | 1 CFU/sample | 1-7 days | Gold standard, simple, species identification | Misses VBNC, labor-intensive, slow |

| PMA-qPCR | Membrane integrity + DNA detection | 2.3 log10 cells/mL [32] | 3-6 hours | Rapid, specific, detects VBNC | Requires optimization, DNA may persist |

| Metabolic Probes | Enzyme activity | 10³-10⁴ cells/mL | 30 min - 4 hours | Rapid, measures activity | May not detect dormant cells |

| Flow Cytometry | Membrane integrity/ physiology | 10²-10³ cells/mL | 1-2 hours | Rapid, quantitative, multi-parameter | Equipment cost, requires expertise |

| Geometric Viability Assay | Culturalility in microformat | 1-10⁶ CFU [30] [5] | 24 hours | High-throughput, low waste | Limited to cultivable cells |

Novel Cultivation-Based Approaches

Innovative methods maintain the culturalility principle while addressing traditional limitations:

Geometric Viability Assay (GVA): This recently developed method embeds samples in agarose within pipette tips, using the geometry of the cone to create an inherent dilution series [30] [5]. The distribution of colonies along the tip's axis enables calculation of viable counts across 6 orders of magnitude while reducing time and consumables by over 10-fold compared to traditional CFU [5].

Fractal Dimension Analysis: An image analysis approach that quantifies colony distribution on plates using fractal geometry, providing automated counting that correlates excellently with manual counts (r = 0.995-0.998, p = 0.0001) while reducing subjectivity and time [29].

Microfluidic and Automated Systems: Microscale culture systems enable high-throughput cultivation and monitoring, while automated plate readers and spiral platers reduce manual labor in traditional CFU protocols [1].

Research Reagent Solutions for Viability Assessment

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bacterial Viability Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Applicable Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Media | LB Agar, CLED Agar, Blood Agar | Support growth and differentiation of bacteria | CFU, GVA |

| Viability Stains | Propidium monoazide (PMA), Tetrazolium salts (CTC, INT, XTT), Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) | Differentiate live/dead cells based on membrane integrity or metabolic activity | PMA-qPCR, Metabolic assays, Microscopy |

| Nucleic Acid Amplification | PCR primers, qPCR probes, Reverse transcriptase | Detect and quantify DNA/RNA from viable cells | PMA-qPCR, RNA-based detection |

| Microbiological Buffers | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Dilution buffers | Maintain osmotic balance and pH during sample processing | All methods |

| Image Analysis Software | ImageJⓇ with Fractal Box-Counter plugin | Automated colony counting and analysis | Fractal dimension analysis, Digital CFU |

Experimental Workflows: Traditional and Modern Approaches

Standard CFU Assay Workflow

Integrated Viability Assessment Strategy

The colony-forming unit assay remains a foundational tool in microbiology, providing unmatched simplicity and direct evidence of bacterial culturalility. However, its limitations—particularly the inability to detect VBNC states and the substantial "great plate count anomaly"—necessitate a paradigm shift in how we define and measure bacterial viability. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice of viability assessment method must align with specific experimental questions and acknowledge the complementary strengths of cultural, molecular, and metabolic approaches. No single method currently provides a complete picture of microbial viability, but integrated strategies that combine multiple approaches offer the most comprehensive solution. As alternative methods like PMA-qPCR and geometric viability assays continue to undergo validation and standardization, they promise to complement and potentially supplant aspects of traditional CFU-based assessment, enabling more accurate, rapid, and comprehensive understanding of microbial communities in health, disease, and environmental contexts.

Metabolic activity assays are indispensable tools in microbiology and cell biology, serving as vital proxies for assessing cell viability, proliferation, and overall physiological state. These assays measure biochemical processes within living cells as indicators of cellular activity and metabolism, often providing higher sensitivity for detecting early stress or damage than traditional membrane integrity assays [34]. Among the most widely used metabolic proxies are tetrazolium salts, resazurin, and fluorescein diacetate (FDA) hydrolysis, each operating on distinct biochemical principles while sharing the common goal of differentiating metabolically active from inactive cells [35]. Understanding the mechanisms, applications, and limitations of these assays is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on accurate viability assessment for screening compounds, evaluating toxicity, and monitoring cell health across diverse biological systems from pure cultures to complex environmental samples.

Biochemical Principles and Mechanisms

Tetrazolium Salts

Tetrazolium salts represent a large family of compounds that measure redox activity in metabolically active cells [35]. The assay principle involves the reduction of water-soluble, lightly colored tetrazolium salts into intensely colored, water-insoluble formazan products by various cellular reductases and dehydrogenases [36]. This reduction process is primarily associated with a functional and active electron transport system (ETS) and is linked to reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides (NADH, NADPH)-dependent oxidoreductases [35]. The colorless tetrazolium salts readily pass through bacterial cell membranes and are reduced intracellularly to different red to violet formazan derivatives [35]. The resulting formazan products are typically quantified after extraction with organic solvents using spectrophotometry [36].

Different tetrazolium salts vary in their chemical properties, reduction requirements, and formazan characteristics as shown in Table 1. Early salts like MTT and INT produce insoluble formazan crystals that require solubilization steps, while newer derivatives like XTT, MTS, and WST series compounds yield soluble formazans amenable to direct measurement [35]. The net positive charge on tetrazolium salts such as MTT and NBT facilitates their cellular uptake and interaction with negatively charged mitochondrial membranes [36].

Figure 1: Tetrazolium Salt Reduction Pathway. The biochemical pathway shows how colorless tetrazolium salts are reduced to colored formazan products through cellular electron transfer systems [35].

Resazurin (Alamar Blue)

The resazurin assay employs a cell-permeable redox indicator that functions as a metabolic activity marker [37]. Resazurin, a non-fluorescent blue dye, is converted to pink, highly fluorescent resorufin in the presence of metabolically active cells [37]. The reduction is primarily mediated by NADPH dehydrogenase, which transfers electrons from NADPH + H+ to resazurin [37]. This conversion can be detected through multiple methods: visual observation of color change from blue to pink, absorbance measurement (typically at 570/600 nm), or fluorimetry (excitation 530-570 nm, emission 580-590 nm) [37]. Unlike tetrazolium assays that often require cell lysis, the resazurin assay is non-destructive, allowing for continuous monitoring and additional parallel analyses on the same samples [37].

Figure 2: Resazurin Reduction Pathway. The metabolic conversion of non-fluorescent resazurin to fluorescent resorufin by cellular reductases [37].

Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) Hydrolysis

Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) hydrolysis operates on a different principle than the redox-based assays. FDA is a non-fluorescent, membrane-permeable compound that is hydrolyzed by intracellular esterases in viable cells to release fluorescein, a highly fluorescent product [35]. The process requires active hydrolase enzymes, which are functional only in cells with intact metabolic processes [35]. The generated fluorescein is retained in cells with intact plasma membranes, creating a strong correlation between fluorescence intensity and the number of viable cells [35]. Fluorescein accumulation can be quantified using fluorimetry with excitation at 485-500 nm and emission measurement at 520-530 nm [35]. This enzyme-based mechanism makes FDA hydrolysis particularly useful for assessing viability across diverse microorganisms, though the specificity depends on the presence and activity of appropriate esterase enzymes in the target cells [35].

Figure 3: FDA Hydrolysis Pathway. Enzymatic conversion of non-fluorescent FDA to fluorescent fluorescein by intracellular esterases [35].

Comparative Analysis of Metabolic Proxies

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Key Metabolic Activity Assays

| Parameter | Tetrazolium Salts (e.g., MTT) | Resazurin (Alamar Blue) | FDA Hydrolysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Principle | Reduction to formazan by cellular reductases/ETS [35] | Reduction to resorufin by NADPH dehydrogenase [37] | Hydrolysis by intracellular esterases [35] |

| Detection Methods | Absorbance after formazan solubilization [36] | Absorbance, fluorescence, or visual color change [37] | Fluorescence measurement [35] |

| Key Detection Wavelengths | 500-600 nm (depends on specific tetrazolium) [35] | Abs: 570/600 nm; Fluor: Ex 530-570/Em 580-590 nm [37] | Ex 485-500 nm/Em 520-530 nm [35] |

| Signal Output | Color development (violet to red) | Color change (blue to pink) and fluorescence development | Fluorescence development |

| Assay Format | End-point (formazan crystals require solubilization) | Kinetic or end-point, suitable for continuous monitoring [37] | Kinetic or end-point |

| Cell Permeability | Generally good for bacteria, varies for eukaryotes [35] | Excellent [37] | Good [35] |

| Toxicity to Cells | Can be toxic at high concentrations [35] | Generally non-toxic, reversible [37] | Generally non-toxic |

| Key Advantages | Wide application range, well-established | Non-destructive, multiple detection methods, real-time monitoring [37] | Direct enzyme activity measurement, sensitive |

| Key Limitations | Solubilization required for insoluble formazans, potential abiotic reduction [35] | Further reduction to non-fluorescent product [36] | pH-dependent fluorescence, enzyme specificity [35] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Tetrazolium Salt Assay Protocol

The tetrazolium reduction assay requires careful optimization of several parameters for accurate results [35]. A standardized protocol for MTT assay in bacterial cultures is outlined below:

Sample Preparation: Harvest cells and adjust to appropriate density (typically 10⁶-10⁸ cells/mL). Include a negative control with formaldehyde-fixed cells (1.5-4% final concentration) to account for abiotic reduction [35].

MTT Solution Preparation: Prepare MTT stock solution in PBS or saline at 5 mg/mL. Filter sterilize and protect from light [35].

Assay Procedure:

- Add MTT solution to samples to achieve final concentration of 0.2-1.0 mg/mL.

- Incubate in dark at optimal growth temperature for 30 minutes to 4 hours.

- Terminate reaction by adding formaldehyde (final concentration 1%) or solubilization solution [35].

Formazan Solubilization:

- Add equal volume of solubilization solution (e.g., DMSO, isopropanol, or acidic sodium dodecyl sulfate).

- Mix thoroughly until formazan crystals are completely dissolved.

- Centrifuge if necessary to remove cell debris [35].

Measurement and Analysis:

- Measure absorbance at 570 nm with reference wavelength at 630-690 nm.

- Calculate metabolic activity relative to negative control and standard curves [35].

Critical parameters requiring optimization include tetrazolium concentration (balancing enzyme saturation against dye toxicity), incubation time, pH, temperature, and potential interference from abiotic reductants present in samples [35].

Resazurin Assay Protocol

The resazurin assay provides a flexible approach for viability assessment with minimal procedural steps [37]:

Reagent Preparation: Prepare resazurin stock solution (0.15-0.5 mg/mL in PBS or culture medium). Filter sterilize and store protected from light [37].

Assay Setup:

- For bacterial cultures, adjust cell density to approximately 10⁵-10⁷ CFU/mL.

- Add resazurin solution to achieve final concentration of 10-50 μM (typically 10% v/v of stock).

- Mix gently and incubate under optimal growth conditions [37].

Kinetic Measurement:

- Monitor fluorescence development over time (15 minutes to 2 hours) using plate reader or fluorimeter.

- Optimal measurement occurs during linear phase of fluorescence increase.

- Alternatively, use end-point measurement after fixed incubation period [37].

Detection Methods:

- Fluorimetric: Excitation 530-570 nm, Emission 580-590 nm

- Colorimetric: Absorbance at 570 nm and 600 nm, calculate reduction ratio

- Visual: Color change from blue to pink indicates metabolic activity [37]

Validation studies demonstrate strong correlation between resazurin reduction and colony-forming units (CFU), with detection limits of approximately 5 log CFU/mL and maximum detection around 8-10 log CFU/mL [37]. The assay shows superior sensitivity compared to optical density measurements, particularly at lower cell densities [37].

FDA Hydrolysis Assay Protocol

The FDA hydrolysis assay protocol focuses on esterase activity as a viability marker [35]:

Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare FDA stock solution (1-5 mg/mL) in acetone or DMSO. Store at -20°C protected from light.

Assay Procedure:

- Add FDA stock to cell suspension to achieve final concentration of 5-50 μg/mL.

- Mix thoroughly and incubate in dark at optimal temperature (typically 20-37°C) for 15-60 minutes.

- Stop reaction by dilution in ice-cold buffer or adding stop solution.

Fluorescence Measurement:

- Measure fluorescence with excitation at 485-500 nm and emission at 520-530 nm.

- Include controls without cells and with heat-killed cells to account for background and non-enzymatic hydrolysis.

Data Interpretation:

- Calculate fluorescence intensity relative to controls.

- Generate standard curves relating fluorescence to cell numbers for quantitative assessment.

The assay is particularly useful for environmental samples and biofilm studies, though optimal FDA concentration and incubation time require empirical determination for different microorganisms [35].

Applications and Performance Data

Comparative Performance in Bacterial Inactivation Studies

Recent studies have directly compared these metabolic proxies in pharmacological and microbiological applications. In bacterial inactivation studies evaluating phage therapy efficacy, the resazurin assay demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional methods [37]. When monitoring Escherichia coli and Salmonella Typhimurium inactivation by bacteriophages, the resazurin assay provided results comparable to the standard colony-forming unit (CFU) method while offering significant advantages in speed and throughput [37]. The detection range for resazurin was established between 5-10 log CFU/mL, with maximum relative fluorescence units (RFU) detected at approximately 8-10 log CFU/mL [37]. Critically, the resazurin assay detected metabolic inhibition earlier than optical density measurements, making it particularly valuable for rapid screening of antimicrobial agents [37].

Environmental and Complex Sample Applications

In environmental microbiology, these metabolic proxies face additional challenges including sample heterogeneity and potential interference [35]. Tetrazolium salts have been widely applied in environmental studies, though careful interpretation is required as reduction depends on both microbial activity and community composition [35]. The FDA hydrolysis assay has proven valuable for assessing total microbial activity in soils, sediments, and biofilms, as esterase enzymes are widespread among diverse microorganisms [35]. However, all three methods share the fundamental limitation of measuring potential metabolic activity rather than direct growth or replication, necessitating complementary approaches for comprehensive microbial characterization [35].

Table 2: Application Suitability Across Research Fields

| Research Field | Recommended Assay | Rationale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial Screening | Resazurin | Non-destructive, real-time monitoring, high throughput compatibility [37] | Linear range 5-10 log CFU/mL; superior to OD measurements [37] |

| Environmental Microbiology | FDA Hydrolysis | Broad enzyme distribution across diverse microbes [35] | Requires pH control; activity varies with community composition [35] |

| Cell Proliferation & Cytotoxicity | Tetrazolium Salts (MTT, XTT) | Well-established, correlates with biomass [36] | Potential toxicity; solubilization required for insoluble formazans [35] |

| Biofilm Studies | Tetrazolium (CTC) or Resazurin | Can penetrate matrix; measure metabolic activity in situ [35] [37] | Diffusion limitations; may require extended incubation [35] |

| Anaerobic Cultures | Tetrazolium (INT) | Functions under anaerobic conditions [35] | Specialized tetrazolium salts required; may have different reduction pathways [35] |

Research Reagent Solutions