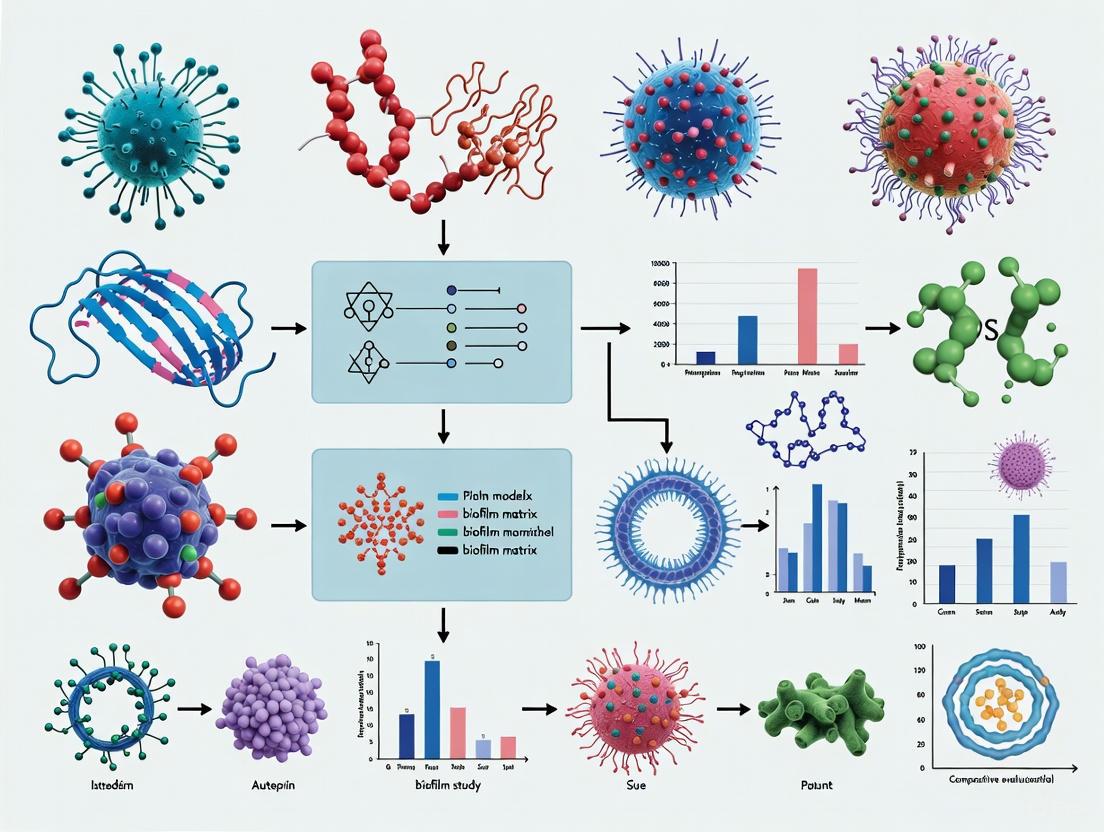

Comparative Evaluation of Biofilm Research Models: From Foundational Concepts to Translational Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparative evaluation of contemporary biofilm matrix research models, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Evaluation of Biofilm Research Models: From Foundational Concepts to Translational Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative evaluation of contemporary biofilm matrix research models, addressing the critical needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It systematically explores foundational biofilm architecture and formation mechanisms, examines diverse methodological approaches from simple phenotypic assays to complex computational models, troubleshoots common translational challenges in bridging laboratory findings with clinical and industrial applications, and validates methods through direct performance comparisons across recent studies. By synthesizing current evidence and emerging trends, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting appropriate biofilm models based on research objectives, ultimately aiming to enhance the predictive validity and translational impact of biofilm research across biomedical and clinical contexts.

Understanding Biofilm Matrix Architecture and Developmental Biology

Biofilms are structured communities of microbial cells enclosed in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix and adherent to either biotic or abiotic surfaces [1]. This matrix is not merely a physical scaffold; it is a dynamic, functional component of the biofilm that determines the immediate conditions of life for the embedded cells [2]. The EPS matrix accounts for over 90% of the biofilm dry mass, with microbial cells constituting less than 10% [3] [1]. This matrix provides critical protection against environmental stresses, including antimicrobial agents, pH fluctuations, and desiccation [4] [1].

The biofilm matrix is a complex assemblage of biopolymers, primarily consisting of exopolysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular DNA (eDNA), along with lipids, RNA, and other biomolecules [3] [5] [4]. The relative abundance and composition of these components vary significantly depending on the microbial species, environmental conditions, biofilm age, and growth substrate [3] [4]. This variable composition directly influences the structural integrity, mechanical stability, and functional properties of biofilms, making understanding the matrix crucial for both combating harmful biofilms and harnessing beneficial ones [3].

This review provides a comparative evaluation of the major biofilm matrix components, supported by experimental data from current research models. We objectively analyze the distinct roles of exopolysaccharides, proteins, and eDNA, present quantitative data on their contributions, and detail the methodological approaches used in their study.

Comparative Analysis of Major Matrix Components

The extracellular polymeric substance matrix forms the architectural foundation of biofilms. The composition and interactions between its primary components dictate the physico-chemical properties of the biofilm community. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these core constituents.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Biofilm Matrix Components

| Matrix Component | Primary Functions | Representative Examples | Experimental Disruption Methods | Impact on Mechanical Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exopolysaccharides | Structural scaffolding, cell-cell adhesion, water retention, protection from desiccation [4] [1] | PIA/PNAG (S. aureus, S. epidermidis), Alginate, Pel, Psl (P. aeruginosa), Cellulose [6] [1] | Periodic acid, Dispersin B [3] | Confers rigidity and structural integrity; degradation leads to biofilm collapse [3] |

| Proteins | Enzymatic activity, structural support, cell-surface adhesion, virulence [4] [1] | Extracellular enzymes, amyloid fibrils (curli), surface adhesins (MSCRAMMs) [6] [2] [1] | Proteinase K, Trypsin [3] | Enhances stability and adhesion; protease treatment reduces cohesion and adhesion [3] |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Structural integrity, cell-cell connectivity, cation chelation, genetic information exchange [5] [7] [2] | Genomic DNA (often fragmented), plasmid DNA [5] | DNase I [3] [5] [7] | Critical for cohesion and stability; DNase treatment disrupts biofilm architecture and reduces strength [3] [7] |

| Other Components | Cross-linking, matrix stabilization [3] | Divalent cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺), lipids, membrane vesicles [3] [2] | Chelating agents (e.g., EDTA) [3] | Strengthens matrix via ion bridging; chelation reduces mechanical stability [3] |

Exopolysaccharides: The Structural Framework

Exopolysaccharides are fundamental to the initial establishment and three-dimensional architecture of biofilms. They can be homopolysaccharides (like cellulose) or heteropolysaccharides (like alginate) and may carry positive or negative charges that influence their physical properties and interactions [1]. For instance, the poly-β(1-6)-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG/PIA) in Staphylococcus biofilms is polycationic and crucial for intercellular adhesion [6] [1]. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the polysaccharides Pel and Psl are essential for maintaining biofilm structure and cellular adhesion [1]. The experimental disruption of these components, using agents like Dispersin B which degrades PNAG, leads to significant biofilm dissolution, confirming their foundational role [3].

Proteins: Functional and Structural Multitaskers

Proteins within the EPS matrix serve diverse roles, from structural support to enzymatic activity. Structural proteins, such as the amyloid-like curli fibers in E. coli and other bacteria, significantly contribute to biofilm strength and stability [2]. Extracellular enzymes retained in the matrix act as an "external digestive system," breaking down complex polymers for nutrient acquisition [1]. Furthermore, surface proteins like microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) in S. aureus facilitate attachment to host tissues and abiotic surfaces [6]. Treatment with proteases such as proteinase K and trypsin has been demonstrated to weaken biofilm cohesive strength, underscoring the protein's role in matrix stability [3].

Extracellular DNA (eDNA): The Underestimated Scaffold

The critical role of eDNA in biofilm structure has been increasingly recognized. Initially considered a mere remnant of lysed cells, eDNA is now established as a crucial structural component [5] [2]. In P. aeruginosa and Clostridioides difficile biofilms, eDNA forms filamentous, grid-like networks that connect bacterial cells and provide architectural integrity [7] [2]. The source of eDNA is often genomic DNA released through cell lysis, though it can undergo fragmentation or other modifications that alter its functional properties compared to intracellular DNA [5]. The degradation of eDNA with DNase I is a highly effective method to disrupt biofilms, demonstrating its non-redundant structural role [3] [5] [7].

Quantitative Data on Component Effects on Biofilm Mechanics

The mechanical stability of biofilms, including properties such as cohesive strength and viscoelasticity, is directly determined by the composition of the EPS matrix. Research systematically applying EPS-targeting agents provides quantitative insights into the contribution of each component. The following table summarizes experimental data from a study that treated Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms with specific degrading agents and measured the resulting changes in cohesive strength [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of EPS-Modifying Agents on Biofilm Cohesive Strength

| Treatment Agent | Target EPS Component | Optimum Concentration | Reduction in Cohesive Strength | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Proteins | 100 mg/L | 65% | Significant loss of structural integrity; reduced adhesion and biofilm biomass |

| Trypsin | Proteins | 100 mg/L | 58% | Weakened biofilm mechanical stability and increased susceptibility to removal |

| DNase I | eDNA | 100 mg/L | 47% | Disruption of biofilm architecture and reduction in overall biofilm stability |

| Periodic Acid | Polysaccharides | 10 mg/L | 62% | Effective degradation of polysaccharide matrix, leading to biofilm dissolution |

| Dispersin B | Polysaccharides (PNAG) | 50 mg/L | 55% | Loss of intercellular adhesion and structural collapse |

| Sodium Metaperiodate | Polysaccharides | 100 mg/L | 70% | Most effective treatment; severe degradation of biofilm cohesive strength |

The data reveal that targeting polysaccharides, particularly with sodium metaperiodate, resulted in the most substantial reduction (up to 70%) in cohesive strength [3]. Protease treatments also caused significant weakening (58-65% reduction), highlighting the importance of proteinaceous elements in structural integrity. While DNase I treatment was effective, its comparatively lower impact suggests that in this model, eDNA may play a supplementary or synergistic role rather than a primary structural one [3]. Furthermore, the study noted that divalent cations (Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺) could enhance biofilm strength by forming ion bridges between anionic EPS components, an effect that can be reversed with chelating agents [3].

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Biofilm Research

The selection of an appropriate laboratory model is critical for studying biofilm formation, structure, and response to treatments. These models range from simple static systems to complex flow-based reactors, each with distinct advantages and limitations that influence their applicability to specific research questions.

Table 3: Comparison of Laboratory Models for Biofilm Studies

| Biofilm Model | Key Features | Experimental Outputs | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static Models (e.g., 96-well microtiter plates) | Biofilms grown under quiescent conditions without shear forces [3] [8] | Biofilm biomass (crystal violet staining), viability (CFU counting), composition analysis [8] | High-throughput, simple, quick, cost-effective [3] [8] | Does not mimic fluid shear forces in natural environments; limited imaging capabilities [3] |

| Flow-Cell Models (e.g., CDC Biofilm Reactor, Calgary Biofilm Device) | Biofilms grown under continuous flow, generating uniform shear stress [3] [8] | Biofilm architecture (CLSM), mechanical properties (AFM), chemical composition (FTIR) [3] | Reproduces key environmental parameters (shear stress); allows for real-time, non-destructive imaging; highly reproducible [3] [8] | More complex setup, requires larger volumes of media and reagents, less amenable to high-throughput screening [3] |

| Modern & Emerging Models | Incorporation of synthetic biology, additive manufacturing, and organoid cultures [8] | Simulation of host-pathogen interactions, testing on medically relevant substrates | Potential to more closely simulate real-life scenarios and complex microenvironments [8] | Often in development stages; can be low-throughput and require specialized expertise [8] |

The choice of model significantly influences experimental outcomes. For instance, well-plate biofilms are grown under quiescent conditions that do not accurately represent the shear forces present in many real-world environments like water pipes [3]. In contrast, the CDC biofilm reactor, used in the study generating the data in Table 2, creates a constant shear force that promotes the development of biofilms with a more relevant architecture and mechanical robustness [3]. The Calgary Biofilm Device (CBD) is another standardized platform that allows for high-throughput screening of antimicrobial susceptibility against biofilm populations [8].

Key Analytical Techniques

Advanced analytical techniques are employed to characterize the chemical, physical, and mechanical properties of biofilms:

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM): Enables non-invasive, three-dimensional imaging of live biofilms, often using fluorescent stains to visualize different EPS components and cellular distributions [3] [7].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Used to probe the nanoscale mechanical properties of biofilms, such as elasticity (modulus) and cohesive strength, by measuring force-deformation relationships [3].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Provides information on the chemical composition and functional groups present in the EPS matrix, allowing for the detection of changes induced by chemical treatments [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Matrix Analysis

Protocol 1: Assessing the Structural Role of eDNA Using DNase I

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the role of eDNA in Clostridioides difficile and Staphylococcus aureus biofilms [5] [7].

Objective: To evaluate the structural contribution of eDNA to biofilm integrity by enzymatic degradation. Materials:

- Mature biofilms (e.g., 48-72 hour cultures)

- DNase I solution (e.g., 100 mg/L in appropriate buffer [3])

- Suitable buffer control (without enzyme)

- Inactivation solution (e.g., EDTA)

- Crystal violet stain or viability assay reagents

- Confocal microscopy equipment with DNA-binding fluorescent dyes (e.g., SYTOX Green)

Methodology:

- Biofilm Growth: Grow biofilms to maturity using an appropriate model (e.g., flow-cell reactor or static plate) [3] [7].

- Treatment Application: Gently overlay the biofilm with DNase I solution. Incubate at the enzyme's optimal temperature (typically 37°C) for a predetermined time (e.g., 1-2 hours). Include a control treated with buffer only [7].

- Enzyme Inactivation: After incubation, remove the enzyme solution and add inactivation solution to stop the reaction.

- Analysis:

- Biomass Quantification: Quantify remaining biofilm biomass using crystal violet staining and elution, measuring absorbance at 570-600 nm [8] [7].

- Structural Analysis (CLSM): For biofilms grown on imaging-compatible surfaces, stain with a DNA-binding dye and a cell viability stain. Image using CLSM to visualize the disruption of the eDNA network and changes in biofilm architecture in 3D [7].

- Mechanical Testing (AFM): Use AFM in force spectroscopy mode to measure the cohesive strength or elastic modulus of treated versus untreated biofilms [3].

Protocol 2: Identifying eDNA-Binding Proteins via Southwestern Blotting

This protocol is based on a study that identified novel eDNA-binding lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus [6].

Objective: To discover and characterize bacterial proteins that interact with eDNA in the biofilm matrix. Materials:

- Biofilm cell lysates or extracellular protein extracts

- Nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane

- Herring sperm DNA or other source of DNA for blocking and probing

- Purified genomic DNA for probe preparation (can be labeled with digoxigenin or biotin)

- Standard Western blotting apparatus and reagents

- Antibodies for detection (e.g., anti-digoxigenin) or other detection system

- Mass spectrometry equipment for protein identification

Methodology:

- Protein Separation: Separate proteins from biofilm extracts by SDS-PAGE.

- Membrane Transfer: Transfer the separated proteins from the gel to a membrane.

- Renaturation: Incubate the membrane in a series of buffers with decreasing concentrations of denaturant (e.g., guanidine hydrochloride) to allow proteins to refold into their native conformation.

- Blocking: Block the membrane with a solution containing non-specific DNA (e.g., herring sperm DNA) and protein blockers (e.g., BSA) to prevent non-specific binding.

- Probing: Incubate the membrane with a labeled DNA probe (e.g., digoxigenin-labeled genomic DNA) to allow specific protein-DNA interactions to occur.

- Detection: Wash the membrane to remove unbound probe and detect bound DNA using appropriate methods (e.g., enzyme-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody and chemiluminescence).

- Identification: Excise the positive bands from a parallel, non-probed gel and identify the proteins using mass spectrometry [6].

Diagram 1: Southwestern Blotting Workflow for eDNA-Binding Protein Identification. This diagram outlines the key steps for identifying proteins that interact with extracellular DNA in the biofilm matrix, culminating in protein identification via mass spectrometry [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues essential reagents and materials used in the featured experiments for analyzing biofilm matrix composition, along with their specific functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Biofilm Matrix Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biofilm Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNase I | Enzymatic degradation of extracellular DNA (eDNA) [3] [5] | Disrupts eDNA scaffold to assess its structural role; reduces biofilm cohesion [3] [7] |

| Proteinase K & Trypsin | Protease enzymes that hydrolyze peptide bonds in proteins [3] | Targets proteinaceous components of EPS; weakens biofilm structural integrity and adhesion [3] |

| Periodic Acid & Dispersin B | Targets polysaccharide components of the EPS matrix [3] | Degrades exopolysaccharides like PNAG, leading to loss of structural stability [3] |

| Crystal Violet | Triphenylmethane dye that stains cells and polysaccharides [8] | Standard staining method for semi-quantitative assessment of total biofilm biomass [8] [7] |

| SYTOX Green/Other Nucleic Acid Stains | Fluorescent dyes that bind to nucleic acids [7] | Visualization of eDNA distribution and network structures within biofilms using CLSM [7] |

| Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | Instrument for nanoscale topographical imaging and mechanical property measurement [3] | Measures cohesive strength, elasticity, and adhesive forces of biofilms via micro-cantilever methods [3] |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM) | High-resolution 3D optical imaging [3] [7] | Non-destructive visualization of biofilm architecture, EPS component localization, and live/dead cell distribution [3] [7] |

| CDC Biofilm Reactor | Standardized system for growing biofilms under constant shear stress [3] | Produces uniform, reproducible biofilms that mimic natural and industrial conditions for testing [3] |

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Networks in Matrix Assembly

The production of EPS components is not constitutive; it is tightly regulated by complex sensory systems that respond to environmental cues. Key regulatory mechanisms include quorum sensing (QS), which senses cell population density, and the intracellular second messenger bis-(3'-5')-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP). The diagram below illustrates a generalized regulatory network influencing EPS production in a model bacterium like Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Diagram 2: Regulatory Network of Biofilm Matrix Production. This diagram shows how environmental signals integrate through systems like quorum sensing and c-di-GMP to regulate the expression of genes responsible for producing key matrix components, including exopolysaccharides, proteins, and eDNA [5] [6] [1]. The release of eDNA is often controlled by regulating autolysins (like AtlA in S. aureus) and nucleases (like Nuc) [5] [6].

The structural composition of the biofilm matrix, dominated by exopolysaccharides, proteins, and eDNA, is a primary determinant of the emergent properties of biofilm communities, including their profound resistance to antimicrobials and mechanical resilience. Quantitative studies demonstrate that targeted enzymatic disruption of any single component can significantly compromise biofilm integrity, with polysaccharide degradation often causing the most substantial loss of cohesive strength [3].

The choice of research model—from simple static plates to advanced flow-cell systems—critically influences the architecture and composition of the studied biofilms and, consequently, the experimental findings [3] [8]. A comprehensive understanding of the synergistic interactions between EPS components, their regulated production, and their spatial organization within the matrix is essential for developing effective strategies to control detrimental biofilms in industrial and clinical settings or to optimize beneficial biofilms in biotechnology and environmental applications. Future research leveraging modern models and omics technologies will continue to unravel the complexity of this dynamic "house of cells."

The five-stage biofilm lifecycle model provides a foundational framework for understanding the development and resilience of structured microbial communities. This guide offers a comparative evaluation of this model, detailing the regulatory mechanisms, physiological transitions, and experimental methodologies essential for biofilm research. We present consolidated quantitative data, standardized experimental protocols, and key reagent solutions to support the development of anti-biofilm strategies, aiming to equip researchers with the tools necessary to investigate and target these complex biological systems effectively.

The five-stage biofilm lifecycle model describes a sequential, highly regulated process through which free-swimming (planktonic) bacteria transition into structured, surface-associated communities, culminating in their active dispersal [9] [10]. This model, extensively studied in organisms like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, outlines a journey from initial surface contact to the formation of a mature, matrix-encased biofilm that exhibits dramatically increased tolerance to antimicrobials and host defenses [9] [11]. Understanding this cycle is critical, as biofilms are implicated in over 80% of microbial infections and represent a principal challenge in 21st-century healthcare due to their innate resistance to treatment [10] [12].

While the classic model provides a valuable heuristic tool, it is primarily based on in vitro studies under controlled conditions. Recent research has expanded this view, showing that biofilms can also exist as non-surface-attached aggregates in clinical settings, such as in the viscous airway mucus of cystic fibrosis patients [9]. Despite these variations, the aggregation of bacteria into a matrix-encased community remains the central hallmark, and the five-stage model continues to be a vital reference point for comparing biofilm physiology across diverse microenvironments [9].

Comparative Analysis of the Five-Stage Lifecycle

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, regulatory mechanisms, and phenotypic markers for each stage of the biofilm lifecycle. This data provides a basis for comparing bacterial behavior and resistance profiles at different developmental points.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of the Five Biofilm Lifecycle Stages

| Lifecycle Stage | Key Characteristics | Primary Regulatory Mechanisms/Structures | Phenotypic Markers & Experimental Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Reversible Attachment | • Weak, transient adhesion to preconditioned surfaces [13] [14]• Mediated by physical forces (van der Waals, electrostatic) [13]• Affected by surface properties (roughness promotes adhesion) [13] | • Flagella [10]• Pili (e.g., type IV pili) [10]• Cell surface adhesins [10] | • Cells can be easily removed by shear stress [14]• Observation of intermittent contact under flow cells [10] |

| 2. Irreversible Attachment | • Permanent adhesion cemented by bacterial secretions [13] [12]• Formation of a monolayer of cells [15]• Production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) begins [14] | • Secretion of EPS (polysaccharides, proteins, eDNA) [14]• Polymer bridging and depletion aggregation [9] | • Cells resist removal by shear forces [14]• Detection of initial EPS components (e.g., eDNA, polysaccharides) [14] |

| 3. Maturation I | • Clonal growth into microcolonies [9] [10]• Development of a 3D structure [14]• Initiation of cell-cell communication [14] | • Active microbial growth and division [9] [13]• Early quorum sensing signaling [15] | • Formation of distinct cellular clusters visible via microscopy [9]• Evidence of metabolic heterogeneity [9] |

| 4. Maturation II | • Complex, mushroom-shaped or pillar-like structures [9] [10]• Formation of fluid-filled channels [10]• High degree of metabolic and physiological heterogeneity [9] | • Established quorum sensing (e.g., AHLs in Gram-negative bacteria) [15]• C-di-GMP signaling promoting matrix production [15]• Nutrient and oxygen gradients within the biofilm [13] | • Biofilms exhibit 10-1000x increased antibiotic tolerance [10]• Presence of persister cells [10]• Distinct architectural features (e.g., channels, voids) [10] |

| 5. Dispersion | • Active, enzymatic liberation of single cells or small aggregates [10]• Return to planktonic lifestyle [14]• Facilitates colonization of new niches [10] | • Production of matrix-degrading enzymes (e.g., glycosidases, nucleases, proteases) [10]• Environmental cues (e.g., nutrient starvation, oxygen tension) [10]• Downregulation of adhesion factors [10] | • Observation of central voids and eroded biofilm structures [10]• Release of planktonic cells into the effluent [14] [10] |

Key Regulatory Pathways

The progression through the biofilm lifecycle is governed by complex regulatory networks. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways that control the transition between the planktonic state and the key stages of biofilm development.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Biofilm Research

A variety of in vitro models are employed to study biofilm formation and evaluate anti-biofilm strategies. The choice of model system significantly influences the structural characteristics and experimental outcomes of the biofilm under investigation.

Table 2: Comparison of Common In Vitro Biofilm Models

| Model Type | Description | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static Microtiter Plate assays | Biofilms form on the walls and bottoms of multi-well plates under non-flow conditions [9]. | • High-throughput screening of biofilm inhibitors [9]• Initial assessment of biofilm formation capacity [9] | • Simple, low-cost, and reproducible [9]• Requires minimal equipment [9] | • Does not simulate fluid shear forces [9]• Can yield unstructured, flat biofilms [9] |

| Flow Cell Systems | Biofilms grow under a continuous flow of medium on a coverslip, allowing real-time microscopy [9] [10]. | • Studying biofilm architecture and development dynamics [9] [10]• Investigating spatiotemporal gene expression [10] | • Generates complex 3D structures (e.g., mushrooms, pillars) [10]• Allows non-destructive, live imaging [10] | • Lower throughput [9]• More complex setup and operation [9] |

| Calgary Biofilm Device (CBD) | Uses a peg lid that fits into a microtiter plate; biofilms form on pegs under gentle agitation [9]. | • Determining antibiotic susceptibility (MBEC) [9]• Studying biofilms of diverse pathogens [9] | • Generates highly reproducible and uniform biofilms [9]• Medium-throughput for antimicrobial testing [9] | • Limited ability for real-time imaging [9] |

| Advanced 3D In Vitro Models | Co-cultures of relevant human cells (e.g., fibroblasts, keratinocytes) and bacteria on biomaterials to mimic tissue interfaces [16]. | • Investigating host-pathogen interactions in implant-associated infections [16]• Testing novel implant materials [16] | • Includes physiological cell-to-cell contacts [16]• Uses human cells, improving clinical relevance [16] | • Technically challenging and costly [16]• Not yet standardized or widely adopted [16] |

Standardized Protocol: Biofilm Formation and Analysis in a Flow Cell System

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to establish the classic five-stage model and is suitable for the detailed study of biofilm architecture and dispersal events [9] [10].

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow the bacterial strain of interest (e.g., P. aeruginosa PAO1) to mid-logarithmic phase in a suitable broth. Centrifuge and wash the cells, then resuspend in a defined, dilute medium to an optical density (OD600) of 0.05 - 0.1 [10].

- System Assembly and Sterilization: Assemble the flow cell system according to the manufacturer's instructions, typically involving a glass coverslip as the substratum. Sterilize the entire flow system, including tubing and medium reservoir, by pumping a sterilizing solution (e.g., 0.5% sodium hypochlorite) through it, followed by copious sterile water and finally the defined medium [9].

- Initial Attachment Phase: Stop the medium flow and carefully inject the prepared bacterial inoculum into the flow cell channel. Allow the cells to settle and attach to the surface for a period of 1-2 hours without flow [10].

- Biofilm Development: Re-initiate a continuous, low-shear flow of the defined medium (e.g., 0.2 mm/sec velocity). This washes away non-adhered cells and provides fresh nutrients for the development of the attached biofilm over 3-7 days [9] [10].

- Staining and Microscopy: At desired time points, introduce fluorescent stains into the flow system. Common stains include:

- SYTO dyes: For labeling nucleic acids and quantifying total biomass.

- Concanavalin A conjugated with a fluorophore (e.g., Tetramethylrhodamine): For specific staining of polysaccharides in the EPS matrix [9].

- Propidium Iodide: For identifying dead cells or extracellular DNA (eDNA).

- After staining, visualize the biofilm using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) to capture high-resolution Z-stacks of the 3D structure [10] [12].

- Image and Data Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with BiofilmQ or COMSTAT plugins) to quantify parameters such as biovolume (µm³/µm²), average thickness (µm), substratum coverage (%), and surface area to biovolume ratio from the CLSM Z-stacks [9].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and their specific functions in biofilm matrix research, providing a quick reference for experimental design.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Biofilm Research |

|---|---|

| SYTO 9 / SYTO 60 | Nucleic acid binding dyes for fluorescent labeling of live and dead bacterial cells within the biofilm, enabling quantification of total biomass via confocal microscopy [12]. |

| Concanavalin A (ConA) Tetramethylrhodamine | A lectin that specifically binds to α-mannopyranosyl and α-glucopyranosyl residues in polysaccharides; used to stain the polysaccharide component of the EPS matrix [9]. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | A red-fluorescent dye that is generally excluded by intact cell membranes. It is used to stain dead cells or, critically, to label extracellular DNA (eDNA), a major structural component of many biofilms [14]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease. Used in experimental protocols to enzymatically degrade protein components within the biofilm matrix, testing their structural importance and contributing to dispersal strategies [10]. |

| DNase I | An enzyme that degrades DNA. Applied to dissect the functional role of eDNA in biofilm integrity, adhesion, and resistance, often leading to biofilm disruption [14] [10]. |

| Dispersin B | A glycoside hydrolase produced by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans that specifically degrades poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG), a key polysaccharide in the matrix of staphylococci and other bacteria [10]. |

| Flow Cells with glass or PVC substrata | The foundational hardware for growing biofilms under defined shear stress, enabling the formation of architecturally complex structures and real-time, non-destructive imaging [9] [10]. |

The five-stage biofilm lifecycle model remains an indispensable framework for comparative research, providing a structured understanding of how bacterial communities develop and evade control measures. The experimental data and methodologies consolidated in this guide highlight the model's utility in deciphering the complex signaling and structural changes that characterize biofilm-mediated resistance. As the field moves toward more sophisticated 3D and organotypic models, the principles outlined by this lifecycle will continue to inform the development of targeted anti-biofilm therapies, such as those inducing dispersion or preventing initial attachment, ultimately aiming to overcome the significant challenge posed by chronic biofilm-associated infections.

The ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) represent a critical group of opportunistic bacteria renowned for their ability to evade antibiotic action, primarily through biofilm formation. These pathogens are responsible for the majority of nosocomial infections worldwide and are a primary focus of antimicrobial resistance research. Within this group, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus have emerged as preeminent model organisms for studying biofilm development, structure, and recalcitrance. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these key model organisms, detailing their unique biofilm matrices, regulatory mechanisms, and experimental applications to inform model selection for specific research objectives.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ESKAPE Pathogens in Biofilm Research

| Pathogen | Gram Stain | Primary Biofilm Matrix Components | Notable Biofilm Traits | Prevalence of Strong Biofilm Formers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Negative | Alginate, Psl, Pel polysaccharides, eDNA, proteins [17] | High intrinsic tolerance, metabolic stratification, strong in vitro models [18] [17] | Common [19] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Positive | PIA/PNAG, proteins, eDNA [20] | Strong adhesion, associated with medical device infections [20] | Common [19] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Negative | Capsular polysaccharides, cellulose [19] | Strong biofilm formation correlated with resistance [19] [21] | Very High [19] [21] |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Negative | Proteinaceous, pili [20] | Strong environmental persistence [19] [22] | Very High [19] [21] |

| Enterococcus faecium | Positive | Esp surface protein [20] | Often forms weaker biofilms [19] | Low [19] |

Table 2: Comparative Antimicrobial Resistance in Biofilm States

| Pathogen | Exemplary Resistance/Tolerance in Biofilms | Multi-Drug Resistance (MDR) Rate | Notable Resistance Mechanisms in Biofilms |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | Tolerance to tobramycin (bound by alginate); induced β-lactamase production [18] [17] | Relatively lower among Gram-negatives in the group [19] | Matrix-based antibiotic sequestration; metabolic dormancy; inducible adaptive colistin tolerance [18] [17] |

| S. aureus | Methicillin resistance (MRSA) via mecA gene [19] [21] | ~10% (Bangladesh study) [19] | Extracellular matrix barrier; persister cells [20] |

| K. pneumoniae | High resistance to carbapenems, cephalosporins; colistin resistance up to 42.9% [19] [21] | Prevalent [19] | Carbapenemase & Metallo-β-lactamase production; strong correlation between biofilm strength and resistance [19] [21] |

| A. baumannii | Elevated resistance to carbapenems, cephalosporins [19] [21] | Prevalent [19] | Carbapenemase production; environmental persistence on surfaces [19] [22] |

| E. faecium | Vancomycin resistance (vanB gene) [19] [21] | ~90% (Bangladesh study) [19] | Not specified in search results |

Model Organism Deep Dive:Pseudomonas aeruginosaandStaphylococcus aureus

1Pseudomonas aeruginosa: The Versatile Benchmark

P. aeruginosa serves as a cornerstone model in biofilm research due to its exceptionally well-characterized and versatile biofilm-forming capabilities. Its utility spans fundamental studies of biofilm development to applied research on chronic infections.

Biofilm Architecture and Matrix Composition: The biofilm matrix of P. aeruginosa is a complex and dynamic structure. Its composition is strain-dependent and can include the exopolysaccharides alginate, Psl, and Pel, which provide structural integrity and mediate surface attachment [17]. Beyond polysaccharides, the matrix incorporates various proteins (e.g., adhesins like CdrA, and amyloid fibers), extracellular DNA (eDNA), and even rhamnolipids, which are involved in structuring microcolonies [17]. This diverse matrix acts as a barrier that can bind to certain antibiotics, such as the aminoglycoside tobramycin, significantly reducing drug penetration and efficacy [18].

Regulatory Networks: The biofilm life cycle is tightly regulated by several key systems:

- c-di-GMP Signaling: High intracellular levels of this second messenger promote the production of matrix components and the transition to biofilm living, while low levels favor biofilm dispersal and a planktonic lifestyle [17].

- Quorum Sensing (QS): The interconnected Las, Rhl, and PQS QS systems coordinate gene expression in a cell-density-dependent manner, regulating the production of virulence factors and matrix components like eDNA and rhamnolipids [17].

- Two-Component Systems: Systems like GacA/GacS integrate environmental signals to regulate biofilm formation, often intersecting with c-di-GMP signaling pathways [17].

Distinctive Research Applications:

- Metabolic Gradients and Tolerance: P. aeruginosa biofilms exhibit a gradient of metabolic activity. Surface-located cells are metabolically active, while cells in the biofilm center enter a dormant state due to nutrient and oxygen limitations. This dormancy renders them highly tolerant to most conventional antibiotics [18]. This model is ideal for studying metabolite diffusion, hypoxia, and persister cell formation.

- Synergistic Antibiotic Therapy: Research using P. aeruginosa flow-cell models revealed that while ciprofloxacin kills the metabolically active surface cells and colistin kills the dormant center, a combination of both antibiotics is required to eradicate the entire biofilm structure [18]. This finding is critical for designing effective treatment strategies for chronic infections.

2Staphylococcus aureus: A Gram-Positive Paradigm

As a Gram-positive pathogen, S. aureus provides a critical counterpoint to P. aeruginosa, with distinct biofilm matrix composition and regulatory mechanisms.

Biofilm Architecture and Matrix Composition: The hallmark of the S. aureus biofilm matrix is the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA), also known as poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) [20]. PIA is crucial for cell-cell adhesion and biofilm accumulation. The matrix is also rich in proteins (e.g., biofilm-associated protein, Bap) and extracellular DNA (eDNA), which provide structural stability and resilience [20].

Research Applications and Polymicrobial Interactions:

- Medical Device-Associated Infections: S. aureus is a leading cause of biofilm-related infections on indwelling medical devices such as catheters and implants, making it a premier model for studying foreign body-associated biofilms [20].

- Polymicrobial Biofilm Dynamics: S. aureus is frequently co-isolated with P. aeruginosa in chronic wounds and cystic fibrosis lungs. Research into their interactions reveals a primarily antagonistic relationship in mixed biofilms. P. aeruginosa often outcompetes S. aureus by producing antimicrobial compounds like 2-n-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline-N-oxide (HQNO) and secreted proteases, leading to a significant reduction in S. aureus biofilm biomass [23]. This makes the pair an excellent model for studying interspecies competition and communication.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized protocols are essential for generating reproducible and comparable data in biofilm research. Below are detailed methodologies for key assays cited in the literature.

Microtiter Plate Biofilm Formation Assay

This is a cornerstone method for the quantitative assessment of biofilm formation capacity [19] [21].

Workflow:

- Inoculation: Dilute an overnight bacterial culture to a standardized optical density (e.g., 0.1 OD~600~). Dispense 200 µL aliquots into the wells of a sterile 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plate. Include negative control wells containing sterile growth medium only.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate under static conditions at the optimal growth temperature (e.g., 37°C for human pathogens) for 24-48 hours.

- Staining and Washing: Carefully remove the planktonic cells and growth medium by inverting and shaking the plate. Wash the adherent biofilms gently twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove loosely attached cells. Fix the biofilms with 99% methanol for 15 minutes, then air dry. Stain the fixed biofilms with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet solution for 15-20 minutes.

- Destaining and Quantification: Rinse the stained plate thoroughly under running tap water and air dry. Add 200 µL of 33% (v/v) glacial acetic acid or 95% ethanol to destain the wells and solubilize the crystal violet. Transfer the solubilized dye to a new microtiter plate and measure the optical density at 570 nm (OD~570~) using a microplate reader.

Figure 1: Microtiter Plate Biofilm Assay Workflow.

Assessment of Polymicrobial Biofilm Interactions

Studying multi-species biofilms requires methods to quantify and visualize interspecies dynamics [23].

Workflow for Competitive Biofilm Assays:

- Co-culture Setup: Prepare monocultures of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. For the polymicrobial assay, mix the two cultures in a 1:1 ratio in fresh medium and inoculate into the wells of a microtiter plate. Include control wells with each species alone.

- Biofilm Growth and Quantification: Incubate and process the plate as described in section 3.1. The total biofilm biomass in co-culture wells is quantified and compared to the biomass in monoculture wells to determine the net interactive effect (e.g., antagonism or synergy).

- Species-Specific Quantification (CFU Counting): After incubation, disrupt the biofilm by sonication or vigorous pipetting. Serially dilute the suspension and plate on both non-selective and selective agars (e.g., Mannitol Salt Agar for S. aureus and Cetrimide Agar for P. aeruginosa). Count the colony-forming units (CFUs) after incubation to determine the proportional contribution of each species to the total biofilm.

- Visualization via Microscopy: Grow biofilms on suitable surfaces (e.g., glass coverslips). For Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), fix samples with glutaraldehyde, dehydrate through an ethanol series, and critical-point dry before sputter-coating and imaging. For Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM), use live/dead stains or species-specific fluorescent tags (e.g., GFP/RFP) to visualize the 3D structure and spatial distribution of each species within the mixed biofilm.

Emerging Anti-Biofilm Therapeutic Strategies

The recalcitrance of biofilms to conventional antibiotics has spurred the development of novel therapeutic approaches, many of which have been pioneered using P. aeruginosa and S. aureus models.

Table 3: Emerging Anti-Biofilm Strategies and Their Mechanisms

| Therapeutic Strategy | Mode of Action | Model Pathogens for Proof-of-Concept |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticles (e.g., Silver, Gold) [20] [24] | Penetrate EPS matrix; disrupt cell membranes; generate reactive oxygen species (ROS); inhibit QS [20]. | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, A. baumannii [20] [24] |

| Bacteriophage Therapy | Lyse bacterial cells directly; produce depolymerase enzymes that degrade EPS matrix [18]. | P. aeruginosa [18] |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors (QSIs) | Block bacterial cell-to-cell communication, reducing virulence and biofilm formation without causing growth pressure [24]. | ESKAPE pathogens [24] |

| Probiotics & Their Metabolites | Competitive exclusion; production of organic acids, bacteriocins, and biosurfactants that inhibit pathogens or disrupt their biofilms [25]. | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae [25] |

| Enzymatic Matrix Disruption (e.g., DNase I) [24] | Degrade key structural components of the biofilm matrix (e.g., extracellular DNA) [24]. | P. aeruginosa, S. aureus [24] |

| Hyperbaric Oxygen | "Wake up" dormant cells in the biofilm center, making them susceptible to antibiotics [18]. | P. aeruginosa [18] |

| Combination Therapy (e.g., Colistin + Ciprofloxacin) | Target multiple bacterial subpopulations (dormant and active) simultaneously for synergistic killing [18]. | P. aeruginosa [18] |

Figure 2: Novel Anti-biofilm Strategies and Their Targets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Biofilm Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biofilm Research | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Microtiter Plates | Provides a standardized, high-throughput surface for biofilm growth and quantification [19] [21]. | Microtiter plate biofilm formation assay [19]. |

| Crystal Violet Stain | A basic dye that binds negatively to charged surface molecules and the biofilm matrix, enabling colorimetric quantification of total adhered biomass [23]. | Staining and quantifying total biofilm biomass [23]. |

| Selective Culture Media (e.g., Cetrimide Agar, MSA) | Allows for the selective growth and differentiation of specific bacterial species from a polymicrobial culture [23]. | Determining CFUs of individual species in mixed-species biofilms [23]. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM) | Enables non-destructive, high-resolution 3D imaging of biofilm architecture, often using fluorescent tags or stains [23]. | Visualizing the spatial structure and organization of live/dead cells in a biofilm [23]. |

| Cell-Free Conditioned Media (CFCM) | Contains metabolites, signaling molecules, and enzymes secreted by a bacterium; used to study interspecies interactions [23]. | Assessing the effect of P. aeruginosa secreted factors on S. aureus biofilm formation [23]. |

| Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Probiotics | Used as a biological tool to investigate competitive exclusion and production of anti-biofilm metabolites [25]. | Evaluating growth inhibition and disruption of pre-formed ESKAPE pathogen biofilms [25]. |

Quorum Sensing and Cell-Cell Communication in Biofilm Community Behavior

Quorum Sensing (QS) represents a fundamental form of bacterial communication that enables population-density-dependent coordination of gene expression, playing a pivotal role in biofilm development and functionality. This sophisticated chemical signaling system allows bacterial cells to collectively regulate behaviors that would be ineffective if performed individually, including the production of public goods, secretion of virulence factors, and formation of complex multicellular communities [26] [15]. Biofilms, which are structured microbial communities encased within a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), rely heavily on QS mechanisms to progress through developmental stages from initial attachment to maturation and eventual dispersal [27] [15]. The biofilm matrix provides structural integrity and environmental protection while creating an environment where local cell densities can reach sufficient levels to activate QS circuits, establishing a critical feedback loop that reinforces community behaviors and enhances survival under adverse conditions [28] [27].

The significance of QS in biofilm biology extends across medical, environmental, and industrial contexts. In clinical settings, QS-regulated biofilms contribute significantly to antimicrobial resistance in device-associated infections and chronic conditions such as cystic fibrosis pneumonia and diabetic foot ulcers [29] [27]. Pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) employ sophisticated QS networks to coordinate virulence factor production and enhance biofilm resilience, making these infections notoriously difficult to eradicate [29] [30]. Conversely, beneficial biofilms, such as those formed by vaginal Lactobacillus species or environmental communities used in wastewater treatment, utilize QS to maintain protective functions and ecosystem stability [31] [32]. Understanding the intricate relationship between QS and biofilm community behavior provides not only fundamental insights into microbial sociology but also unveils potential therapeutic targets for controlling harmful biofilms while preserving beneficial ones.

Comparative Analysis of Research Models in Biofilm Matrix Studies

Methodological Approaches for Investigating Biofilm Formation and Quantification

The study of biofilm development and QS requires specialized methodologies that capture both structural complexity and chemical signaling dynamics. Traditional techniques have provided foundational knowledge, while advanced technologies now enable unprecedented resolution and analytical depth. The crystal violet staining assay represents a cornerstone method for quantifying total biofilm biomass through colorimetric measurement of dye bound to cells and matrix components [27]. Though cost-effective and suitable for high-throughput screening, this approach cannot distinguish viable from non-viable cells and provides limited structural information [27]. Colony-forming unit (CFU) enumeration offers assessment of culturable bacteria but may underestimate true viability due to biofilm-associated metabolic dormancy [27]. The Congo red agar method serves as a qualitative screen for extracellular polysaccharide production, revealing matrix-producing strains through characteristic colony morphology, though it lacks quantitative precision [27].

Advanced imaging technologies have dramatically enhanced our capacity to characterize biofilm architecture and cellular organization. Confocal laser scanning microscopy provides three-dimensional visualization of hydrated biofilms when combined with fluorescent staining, though it may alter native biofilm properties [27]. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) offers high-resolution surface imaging but requires sample dehydration and metallic coating, potentially introducing structural artifacts [27] [33]. Most recently, large-area automated atomic force microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool capable of capturing nanoscale topological features over millimeter-scale areas, enabling visualization of individual cells, flagellar structures, and EPS components without extensive sample preparation [33]. This automated AFM approach, enhanced by machine learning algorithms for image stitching and analysis, has revealed previously obscured spatial heterogeneities and patterned cellular arrangements such as the honeycomb structures observed in Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms [33].

For QS investigation, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) enables sensitive detection and quantification of signaling molecules like acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) extracted from biofilm supernatants [32]. Transcriptomic analyses through RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) provide comprehensive profiles of gene expression changes during biofilm development, with recent computational advances such as Python-based scorecard tools helping researchers identify significant expression patterns across multiple experimental conditions [34]. These complementary methodologies collectively enable researchers to correlate structural biofilm development with the underlying QS regulatory networks that govern community behavior.

Comparison of Experimental Models for Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Research

Table 1: Comparative analysis of model systems for quorum sensing and biofilm research

| Model System | Key Characteristics | QS Systems Present | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen | Las, Rhl, Pqs, Iqs [30] | Medical biofilm research, antimicrobial testing [30] | Well-characterized hierarchical QS network, clinical relevance [30] | Complex regulation, adaptive mutations (e.g., lasR) [30] |

| Escherichia coli (UPEC) | Gram-negative uropathogen | AI-2, AI-3 [26] | Urinary tract infection studies, virulence factor analysis [29] | Genetic tractability, clinical importance in UTIs [29] | Strain variability, less specialized QS systems |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Gram-positive pathogen | AIP-based system [26] | Medical device infections, antibiotic resistance studies [34] | Peptide-based QS mechanism, high clinical prevalence | Different signaling mechanism from Gram-negative models |

| Lactobacillus species | Gram-positive commensal | Oligopeptide-based, potential AHL production [32] | Probiotic research, vaginal microbiome studies [32] | Beneficial biofilm model, host-microbe interactions | Limited AHL production in some species (e.g., L. gasseri) [32] |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | Gram-negative plant-associated | Not fully characterized | Biofilm architecture studies, plant-microbe interactions [33] | Distinctive honeycomb biofilm pattern, plant growth-promoting properties [33] | Less characterized QS systems |

Quantitative Comparison of Biofilm Formation and Quorum Sensing Molecules

Table 2: Experimental data comparison across different bacterial species and conditions

| Bacterial Species/Strain | Biofilm Formation Measurement | QS Molecule Detected | Experimental Conditions | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) [29] | 72.22% of isolates (n=180) formed biofilms vs. 16.66% commensal isolates | fimH gene (98.33% of isolates) | Clinical isolates from UTI patients; tissue culture plate method | Biofilm-forming UPEC showed 128-fold reduction in ciprofloxacin susceptibility compared to commensal strains |

| Commensal E. coli [29] | 16.66% formed biofilms | Not specified | Intestinal isolates from healthy individuals | Significantly lower biofilm formation compared to UPEC pathogens |

| Lactobacillus crispatus [32] | High quantity biofilm | AHLs detected | Microfermenter system, 48h growth, MRS broth | Produces AHL QS molecules alongside expected oligopeptide signals |

| Lactobacillus jensenii [32] | High quantity biofilm | AHLs detected | Microfermenter system, 48h growth, MRS broth | Similar AHL production to L. crispatus |

| Lactobacillus gasseri [32] | Lower quantity biofilm | No AHLs detected | Microfermenter system, 48h growth, MRS broth | Relies solely on oligopeptide-based QS without AHL production |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 [33] | Honeycomb pattern formation, cells ~2μm length, flagella 20-50nm height | Not characterized | PFOTS-treated glass surfaces, 6-8h incubation | Flagellar coordination observed in early attachment and biofilm assembly |

Quorum Sensing Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms

Molecular Foundations of Bacterial Communication Systems

Quorum sensing mechanisms vary significantly between bacterial groups but share common fundamental principles. In Gram-negative bacteria, QS typically employs acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) as signaling molecules, which diffuse across cell membranes and bind intracellular transcriptional regulators of the LuxR family when sufficient concentration thresholds are reached [26]. These AHL-receptor complexes then activate expression of target genes, including those for AHL synthesis, creating a positive feedback loop that results in density-dependent gene regulation [26]. The marine bacterium Aliivibrio fischeri provided the foundational model for this mechanism with its LuxI/LuxR system controlling bioluminescence, establishing the paradigm for AHL-based communication [26].

In contrast, Gram-positive bacteria typically utilize processed oligopeptides (autoinducing peptides, AIPs) as QS signals that are detected by membrane-associated two-component systems rather than intracellular receptors [26]. These systems involve sensor kinase proteins that autophosphorylate upon AIP binding, then transfer phosphate groups to response regulator proteins that modulate target gene expression [26]. Staphylococcus aureus employs such a system in its agr (accessory gene regulator) pathway, which coordinates virulence factor production and biofilm development [26]. Beyond these canonical systems, certain signaling molecules facilitate cross-species communication, most notably autoinducer-2 (AI-2) synthesized via the LuxS pathway, which is recognized as a universal signal for interspecies communication [26]. Additionally, Escherichia coli utilizes autoinducer-3 (AI-3) for interkingdom signaling, demonstrating the evolutionary sophistication of bacterial communication networks [26].

Integrated Quorum Sensing Network inPseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa possesses one of the most sophisticated and hierarchically organized QS networks, making it a paradigm for complex bacterial communication. The core circuitry consists of three interconnected systems (Las, Rhl, and Pqs) that operate in a coordinated cascade to regulate hundreds of genes involved in virulence, secondary metabolism, and biofilm development [30]. The Las system, positioned at the top of this hierarchy, utilizes N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C12-HSL) as its signal molecule, which binds to the transcriptional activator LasR to control expression of virulence factors and components of the Rhl system [30]. The Rhl system employs N-butyryl-L-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL) as its signal, with the C4-HSL-RhlR complex activating genes for rhamnolipid production, pyocyanin synthesis, and additional virulence factors [30].

The third major system, Pqs, utilizes 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolone (PQS) as its signal molecule, which binds to PqsR to activate genes involved in pyocyanin production and also influences the Rhl system [30]. More recently, a fourth system termed "integrated quorum sensing" (Iqs) has been identified, which connects the central Las system with phosphate stress response and downstream Pqs and Rhl systems [30]. The Iqs system produces 2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-thiazole-4-carbaldehyde (IQS) as its signaling molecule and appears to provide a backup communication channel when the primary Las system is compromised, as frequently occurs in clinical isolates from chronic infections [30]. This sophisticated, multi-layered regulatory architecture enables P. aeruginosa to maintain precise control over collective behaviors despite environmental fluctuations or selective pressures, contributing significantly to its success as an opportunistic pathogen.

Diagram Title: P. aeruginosa Integrated Quorum Sensing Network

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Microfermenter Biofilm Growth and AHL Extraction Protocol

The microfermenter system provides a controlled environment for studying biofilm development under conditions that more closely mimic natural habitats than static cultures. For Lactobacillus species biofilm analysis, the following protocol has been established [32]:

Biofilm Growth Phase:

- Preparation: Autoclave microfermenter components including glass spatula, connectors, and Tygon tubes. Prepare 200 mL of de Mann, Ragosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth and autoclave.

- Inoculation: Scrape frozen stock bacteria of Lactobacillus species (e.g., L. crispatus CIP 103603, L. jensenii CIP 69.17T, L. gasseri CIP 102991T) and inoculate into 5 mL MRS broth. Grow for 24 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Standardization: Centrifuge culture at 3,200 rpm for 15 minutes, discard supernatant, and resuspend pellet in fresh MRS broth. Adjust to optical density 0.02 (approximately 10⁴-10⁵ cells/mL).

- Assembly: Add 50 mL MRS media to sterile non-bubbling reactor, inoculate with 1 mL standardized culture, and insert sterile glass spatula. Incubate for 3 hours at room temperature.

- System Operation: Transfer reactor to heated water tank (37°C) and pressurize system with air (0.04 bar) to establish flow. Run microfermenter for 48 hours.

Biofilm Collection and AHL Extraction:

- Biofilm Harvesting: Remove glass spatula with attached biofilm and place in sterile measuring cylinder with 50 mL MRS broth. Vortex briefly to dislodge biofilm.

- Sample Processing: Centrifuge media from reactor at 3,200 rpm for 15 minutes at room temperature. Retain supernatant for AHL analysis.

- AHL Extraction: Combine 15 mL supernatant with equal volume ethyl acetate (99.5%) in glass test tube. Vortex for 10 seconds and allow phases to separate. Transfer organic phase to beaker and repeat extraction. Combine organic portions and evaporate overnight in fume hood.

- Sample Preparation: Resuspend residue in 1,000 μL acetonitrile and store at -20°C until GC-MS analysis.

GC-MS Analysis of AHLs:

- Utilize standards including C4-HL, C6-HL, C8-HL, C10-HL, and C12-HL for quantification.

- Employ appropriate GC-MS parameters for separation and detection of AHL compounds.

- Compare retention times and mass spectra of samples against standards to identify and quantify AHL production [32].

Tissue Culture Plate Method for Biofilm Quantification

The tissue culture plate (TCP) method represents the gold standard for phenotypic detection of biofilm formation and provides quantitative data on bacterial adherence capacity [29]:

Biofilm Growth and Fixation:

- Inoculate trypticase soy broth with 2% glucose using colonies from fresh agar plates. Incubate for 24 hours at 37°C under stationary conditions.

- Dilute broth culture 1:100 with fresh medium. Add 200 μL diluted culture to individual wells of sterile 96-well flat-bottomed tissue culture plate. Include control wells with medium only.

- Incubate plate for 24 hours at 37°C to allow biofilm formation.

- After incubation, gently remove contents by tapping plate. Wash wells four times with 200 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) to remove non-adherent planktonic bacteria.

Biofilm Staining and Quantification:

- Fix adherent biofilms with sodium acetate (2%) for 10 minutes.

- Stain with crystal violet (0.1% w/v) for 1 minute. Rinse excess stain with deionized water and air dry plates.

- Measure optical density of stained adherent bacteria using micro-ELISA auto reader at 570 nm wavelength (OD₅₇₀).

- Interpret results: OD values represent bacterial adherence index, with higher values indicating stronger biofilm formation capacity [29].

Classification Criteria:

- Establish cut-off values (ODc) based on negative control wells: OD ≤ ODc = non-biofilm producer, ODc < OD ≤ 2×ODc = weak biofilm producer, 2×ODc < OD ≤ 4×ODc = moderate biofilm producer, 4×ODc < OD = strong biofilm producer.

Large-Area Automated AFM for Biofilm Imaging

Advanced atomic force microscopy techniques enable nanoscale characterization of biofilm topography and cellular organization across millimeter-scale areas [33]:

Sample Preparation:

- Grow Pantoea sp. YR343 in appropriate liquid growth medium.

- Place PFOTS-treated glass coverslips in petri dish and inoculate with bacterial culture.

- At designated time points (e.g., 30 minutes, 6-8 hours), remove coverslips and gently rinse to remove unattached cells.

- Air dry samples before AFM imaging.

Automated AFM Imaging:

- Utilize large-area AFM system with automated scanning capabilities.

- Implement machine learning algorithms for optimal region selection and scanning parameter optimization.

- Acquire multiple high-resolution images across millimeter-scale areas with minimal overlap.

- Apply image stitching algorithms to create seamless composite images.

Data Analysis:

- Use machine learning-based segmentation for automated cell detection and classification.

- Extract parameters including cell count, confluency, cell shape, and orientation.

- Analyze spatial distribution patterns and identify distinctive organizational features such as honeycomb structures.

- Correlate topological features with functional properties and developmental stages [33].

Diagram Title: Comprehensive Biofilm Research Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for quorum sensing and biofilm studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Application/Function | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Media & Supplements | de Mann, Ragosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth | Lactobacillus culture and biofilm growth [32] | Used for vaginal Lactobacillus species biofilm studies [32] |

| Trypticase soy broth with 2% glucose | Enhanced biofilm formation in tissue culture plate method [29] | UPEC biofilm quantification studies [29] | |

| Congo red agar with supplements | Qualitative assessment of EPS production [27] | Differentiation of matrix-producing and non-producing strains [27] | |

| Staining & Detection Reagents | Crystal violet (0.1% w/v) | Total biofilm biomass staining [29] [27] | Standard method for biofilm quantification in TCP and tube methods [29] |

| Acyl-homoserine lactone standards (C4-HL to C12-HL) | GC-MS quantification of QS molecules [32] | Detection of AHL production in Lactobacillus species [32] | |

| Ethyl acetate (99.5%) | Organic solvent for AHL extraction [32] | Extraction of AHLs from biofilm supernatants prior to GC-MS [32] | |

| Surface Materials | PFOTS-treated glass coverslips | Hydrophobic surface for bacterial attachment studies [33] | Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilm assembly analysis via AFM [33] |

| Polystyrene tissue culture plates | Standard substrate for biofilm quantification [29] | High-throughput screening of biofilm formation capacity [29] | |

| Glass spatula for microfermenter | Biofilm substrate in flow systems [32] | Lactobacillus biofilm growth under controlled conditions [32] | |

| Specialized Equipment | Microfermenter system with flow control | Biofilm growth under physiologically relevant shear forces [32] | Simulation of natural environments for Lactobacillus biofilms [32] |

| Automated atomic force microscope | Nanoscale topological imaging of biofilm structure [33] | Visualization of individual cells, flagella, and EPS matrix [33] | |

| Gas chromatography-mass spectrometer | Sensitive detection and quantification of QS molecules [32] | Identification of AHL production in bacterial supernatants [32] |

The comparative analysis of research models and methodologies presented in this guide underscores the sophisticated interplay between quorum sensing systems and biofilm community behavior across diverse bacterial species. The experimental data reveals that pathogenic organisms like UPEC and P. aeruginosa deploy complex, often hierarchical QS networks to coordinate virulence and enhance biofilm resilience, while commensal species such as vaginal Lactobacillus utilize complementary signaling strategies to maintain protective biofilms [29] [30] [32]. The methodological advances in biofilm research, particularly the development of large-area automated AFM and sophisticated transcriptomic analysis tools, have enabled unprecedented resolution in characterizing both structural and regulatory dimensions of microbial communities [34] [33].

These insights carry significant implications for therapeutic development, suggesting that targeting quorum sensing mechanisms rather than bacterial viability may represent a promising strategy for combating biofilm-associated infections without promoting antibiotic resistance [28] [27]. The documented efficacy of natural quorum sensing inhibitors like curcumin against Vibrio species demonstrates the potential of this approach [28]. Furthermore, the emerging understanding of beneficial biofilms and their signaling mechanisms opens avenues for probiotic enhancement and microbiome engineering applications [32]. As research continues to unravel the complexities of bacterial communication, particularly through multi-scale modeling and single-cell analysis techniques, our capacity to manipulate biofilm communities for clinical, environmental, and industrial benefit will undoubtedly advance, potentially heralding a new era in microbial management strategies grounded in ecological principles rather than simply eradication.

Biofilms, structured communities of microorganisms encased in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), represent a significant challenge across medical, industrial, and environmental fields. Their formation is not a random process but a carefully orchestrated sequence influenced profoundly by environmental conditions. Understanding the comparative impact of surface properties, nutrient availability, and flow dynamics is crucial for developing effective biofilm control strategies. This guide provides a systematic comparison of how these factors govern biofilm development, architecture, and resilience, drawing upon recent experimental data and advanced research models. The assessment is framed within a broader thesis on evaluating biofilm matrix research models, providing researchers with actionable insights for experimental design and interpretation.

Comparative Analysis of Key Environmental Factors

Surface Properties: The Foundation for Colonization

Surface characteristics serve as the primary interface determining initial bacterial attachment and subsequent biofilm development. The physicochemical properties of a surface, including its hydrophobicity, roughness, and chemical composition, directly regulate the kinetics of microbial colonization [35].

Microplastic Case Study: Research on microplastics provides a compelling model for understanding surface-driven colonization. Their inherently hydrophobic surfaces rapidly adsorb dissolved organic matter from the environment, forming a conditioning film that facilitates the initial, reversible attachment of pioneer bacteria [35]. This process highlights a universal principle: surface hydrophobicity is a critical driver for the first stage of biofilm formation.

Medical Device Implications: Studies on reusable medical devices, particularly those made of stainless steel, underscore the practical implications of surface properties. The residual soil and surface imperfections on processed devices can create niches that shield initial colonizers, thereby compromising disinfection protocols and promoting resilient biofilm communities [36]. The material's surface finish directly influences the efficacy of standard cleaning regimens.

Nutrient Availability: The Architect of Biofilm Structure and Function

Nutrient abundance is a pivotal environmental factor that modulates biofilm formation, microbial synergy, and stress tolerance. The concentration of available nutrients dictates not only the biomass but also the structural integrity and defensive capabilities of the biofilm matrix.

Table 1: Comparative Impact of Nutrient Abundance on Biofilm Properties

| Biofilm Property | High Nutrient Conditions (e.g., TSB) | Low Nutrient Conditions (e.g., 1/10 TSB) | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Biomass | Significantly higher [37] | Reduced [37] | Polystyrene surfaces, multispecies |

| Exopolysaccharide (EPS) Content | Significantly higher [37] | Reduced [37] | Polystyrene surfaces, multispecies |

| Sanitizer Tolerance | Significantly higher survival [37] | Reduced tolerance [37] | Sodium hypochlorite challenge |

| Synergistic Interactions | Strong in multispecies consortia [37] | Weaker or conditional [37] | P. fluorescens, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes |

| Phenotypic Adaptation | - | Metabolic reprogramming, sporulation [38] | Bacillus cereus in dairy models |

The data in Table 1 reveals a consistent trend: nutrient-rich environments foster more robust and resilient biofilms. A key finding is the conditional synergy observed in multispecies biofilms; high nutrient availability promotes cooperative interactions, leading to significantly enhanced biomass, exopolysaccharide production, and sanitizer tolerance compared to single-species arrangements [37]. For instance, Listeria monocytogenes survival after sanitizer treatment jumped from 2.3 log CFU/cm² in a single-species biofilm to 5.3 log CFU/cm² in a multispecies consortium under high nutrients [37].

Under nutrient starvation, bacteria enact sophisticated survival strategies. Studies on Bacillus cereus in dairy-model systems demonstrate that nutrient limitation triggers a phenotypic shift, reducing planktonic growth but concurrently enhancing sporulation and biofilm formation as protective measures [38]. This adaptive response is coordinated by metabolic reprogramming, downregulating energy-intensive pathways like fatty acid biosynthesis while upregulating sporulation and stress response proteins [38].

Flow Conditions: The Mechanical Sculptor of Biofilms

Fluid flow imposes mechanical forces that profoundly influence biofilm morphology, internal structure, and ecological function. The hydrodynamic environment determines how biofilms expand, their physical properties, and their ability to colonize new areas.

Morphological Plasticity: Under fluid flow, biofilms can form not only surface-attached mats but also suspended filamentous structures known as streamers [39]. These streamers are tethered to surfaces and extend into the bulk flow, often causing catastrophic clogging in medical devices and industrial systems [39].

Stress-Hardening Behavior: Recent research has uncovered that biofilm streamers exhibit a unique stress-hardening behavior. Their differential elastic modulus and effective viscosity increase linearly with the external hydrodynamic stress applied to them [39]. This means that the higher the flow-induced stress, the stiffer and more viscous the biofilm becomes, enhancing its mechanical resilience. This behavior is conserved across various bacterial species and is primarily governed by the extracellular DNA (eDNA) in the matrix, which acts as a structural backbone [39]. Extracellular RNA (eRNA) further modulates this network by promoting the formation of complex eDNA structures [39].

Wrinkling Dynamics: The interplay of adhesion, friction, and nutrient availability under flow regulates the biofilm's wrinkling behavior—a buckling instability from internal compressive stresses [40]. Computational models predict that with constant nutrient supply and high friction, wrinkles initiate at the biofilm center where stresses are highest. In contrast, under low nutrients or low friction, nutrient depletion halts central growth, shifting wrinkle initiation to the nutrient-rich outer edge [40]. This transition has been experimentally validated in E. coli biofilms [40].

Table 2: Comparative Effects of Flow Conditions on Biofilm Streamers (P. aeruginosa PA14)

| Flow Condition (Laminar Regime) | Streamer Length (L) | Streamer Radius near Pillar (R) | Key Mechanical Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Flow Velocity | Longer [39] | Smaller [39] | Lower baseline stiffness |

| Higher Flow Velocity | Shorter [39] | Larger [39] | Stress-hardening; increased stiffness and viscosity [39] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Biofilm Research

Advancing biofilm research relies on the use of sophisticated models that accurately simulate the complex interplay of environmental factors.

Standardized Biofilm Reactor Models

For evaluating surface colonization and sanitizer efficacy under controlled flow and nutrient conditions, two standardized models are prominent:

- Drip Flow Reactor (DFR): This model is characterized by an initial batch phase for biofilm establishment, followed by a continuous flow phase for development. It is designed to simulate low-shear environments [36].

- CDC Biofilm Reactor (CDC-BR): This model utilizes a batch phase followed by a continuous phase under constant agitation, creating higher shear conditions compared to the DFR [36].

Comparative Experimental Workflow: A direct comparison of these models for growing Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on stainless steel coupons revealed critical differences. The CDC-BR produced biofilms with significantly higher cell densities, while the DFR generated biofilms with greater total organic carbon and protein content, indicating a denser extracellular matrix under low-shear conditions [36]. This highlights that the choice of reactor model directly influences the final architecture and composition of the test biofilm.

Advanced 3D In Vitro and Computational Models

To bridge the gap between simple 2D models and complex in vivo systems, the field is increasingly adopting advanced 3D models.

Organotypic 3D Models: These systems aim to closely mimic the in vivo situation by co-culturing relevant human cells (e.g., fibroblasts, keratinocytes, immune cells) with bacteria in the presence of implant materials [16]. For instance, dental implant models use fibroblasts and keratinocytes challenged with Gram-positive bacteria to study peri-implantitis [16]. These models allow for the investigation of multifaceted host-pathogen-implant interactions under physiologically relevant conditions.

Lattice-Network Computational Models: These models simulate biofilm morphogenesis by representing the biofilm as a two-dimensional elastic network interacting with a rigid substrate [40]. Growth is driven by local nutrient availability following Monod kinetics, and the model independently controls parameters like friction and adhesion. This allows researchers to disentangle the individual and combined contributions of physical forces and nutrient gradients to the wrinkling and delamination behavior of biofilms, offering insights that are challenging to obtain experimentally [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following toolkit compiles essential reagents and materials critical for investigating environmental factors in biofilm formation, as derived from the cited experimental studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biofilm Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biofilm Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|