Comparative Mechanisms of Bacterial Persister Formation: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms underlying bacterial persister cell formation across major pathogenic species.

Comparative Mechanisms of Bacterial Persister Formation: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms underlying bacterial persister cell formation across major pathogenic species. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge on shared and species-specific pathways, including toxin-antitoxin modules, the stringent response, and biofilm-mediated tolerance. It further explores advanced methodologies for persister research, current challenges in therapeutic development, and a comparative evaluation of persistence strategies in organisms such as Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Salmonella. The review concludes by outlining future directions for overcoming treatment failures in chronic and recurrent infections, aiming to bridge the gap between basic research and clinical application.

Defining the Dormant Threat: Core Concepts and Universal Pathways in Persister Formation

The relentless challenge of treating bacterial infections stems not only from the well-known phenomenon of antibiotic resistance but also from the more elusive concept of antibiotic persistence. While both enable bacterial survival under antimicrobial treatment, they represent fundamentally distinct survival strategies with critical implications for therapeutic outcomes and public health [1] [2]. Antibiotic resistance refers to heritable genetic changes that enable bacteria to grow in the presence of antibiotics, typically through mechanisms that prevent the drug from binding to its target or actively remove it from the cell [3]. In contrast, bacterial persistence describes a transient, non-heritable phenotypic state in which a small subpopulation of genetically susceptible cells enters a dormant or slow-growing state, thereby surviving antibiotic exposure without genetic alteration [4] [5].

This distinction is clinically paramount: resistant strains lead to treatment failure against which alternative antibiotics must be sought, while persister cells underlie chronic, relapsing infections that resume after treatment cessation, complicating conditions such as tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis, and biofilm-associated infections [1] [2]. Understanding the mechanistic differences between these phenomena is thus essential for developing effective therapeutic strategies to combat persistent infections.

Table 1: Fundamental Distinctions Between Antibiotic Resistance and Persistence

| Characteristic | Antibiotic Resistance | Antibiotic Persistence |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Basis | Heritable genetic mutations or acquired resistance genes [3] | Non-heritable, phenotypic variation without genetic change [4] |

| Population Effect | Entire population grows in antibiotic presence [4] | Small subpopulation (0.001-1%) survives but does not grow during treatment [5] [6] |

| MIC Change | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) increased [3] | MIC unchanged; population exhibits tolerance [1] |

| Reversibility | Stable and irreversible | Transient and reversible upon antibiotic removal [2] |

| Clinical Impact | Treatment failure requiring alternative drugs | Chronic, relapsing infections after treatment [1] |

Molecular Mechanisms: Contrasting Pathways to Survival

Genetic Foundations of Antibiotic Resistance

Antibiotic resistance emerges through specific genetic alterations that enable bacteria to neutralize, exclude, or modify antimicrobial agents. These mechanisms include: (1) * enzymatic inactivation* of antibiotics, such as β-lactamases that hydrolyze β-lactam antibiotics; (2) target modification that reduces antibiotic binding affinity; (3) reduced permeability of cellular envelopes through porin alterations; and (4) active efflux of antibiotics via membrane transporters [3] [7]. These resistance determinants can be acquired through horizontal gene transfer or emerge via selective pressure from mutations in chromosomal genes, resulting in stable, heritable resistance that enables growth under antibiotic pressure [7].

Phenotypic Basis of Bacterial Persistence

Persister cells survive antibiotic treatment not through genetic resistance mechanisms but via phenotypic switching to a dormant or slow-growing state [4]. This transition is mediated by diverse molecular mechanisms that include:

Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems: These genetic modules consist of a stable toxin that disrupts essential cellular processes (e.g., translation, DNA replication) and a labile antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin [4]. Under stress conditions, activation of toxins such as HipA, MqsR, and TisB induces a dormant state by inhibiting translation through mRNA cleavage or reducing ATP levels [4] [5]. For instance, MqsR cleaves mRNA at GCU sites, dramatically reducing cellular translation and inducing dormancy [4].

Stringent Response: Nutrient limitation and other stresses trigger the accumulation of the alarmone (p)ppGpp, which redirects cellular resources from growth to maintenance, promoting a persistent state [4].

Reduced Metabolism: Persisters exhibit downregulated metabolic activity, particularly in central carbon metabolism and energy production, which protects them from antibiotics that corrupt active cellular processes [1] [5].

These mechanisms collectively enable a small bacterial subpopulation to enter a transient, drug-tolerant state without genetic alteration, distinguishing persistence from genuine resistance.

Detection Methodologies: Experimental Approaches for Discrimination

Establishing Persistence: The Time-Kill Assay

The gold standard for detecting persister cells is the time-kill curve assay, which demonstrates the characteristic biphasic killing pattern where the majority of cells die rapidly while a small subpopulation survives prolonged antibiotic exposure [6].

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Distinguishing Resistance and Persistence

| Method | Protocol Overview | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|

| Time-Kill Curve Assay | Expose bacterial culture to bactericidal antibiotic; plate samples at intervals (1, 3, 5, 7, 20h) after washing away antibiotic; count CFUs [6] | Biphasic killing curve indicates persistence; subpopulation survives without regrowth during treatment [5] [6] |

| Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | Standard broth microdilution following EUCAST/CLSI guidelines [6] | Elevated MIC indicates resistance; unchanged MIC with survival in time-kill indicates persistence [1] |

| Population Analysis Profile (PAP) | Plate serial dilutions of culture on antibiotic gradient plates; enumerate colonies after 24-48h incubation | Resistant mutants grow at high concentrations; persisters show small subpopulation surviving across concentrations |

Detailed Protocol for Time-Kill Assy:

- Grow bacterial cultures to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.2-0.3) in appropriate broth [6].

- Add bactericidal antibiotic at high concentration (typically 10-100× MIC) [6].

- Incubate at 37°C with shaking.

- At predetermined timepoints (e.g., 1, 3, 5, 7, and 20 hours), remove aliquots and wash cells with sterile saline to remove antibiotic [6].

- Perform serial dilutions and plate on antibiotic-free agar.

- Count colonies after 24-48 hours incubation and plot log CFU/mL versus time.

- Include antibiotic-free control to monitor normal growth [6].

Distinguishing Genetic Resistance

To confirm whether survival stems from resistance or persistence, researchers must:

- Determine MIC values for surviving cells - persisters will exhibit unchanged MIC compared to original population [1].

- Subculture surviving cells in antibiotic-free medium, then re-challenge with the same antibiotic - persister descendants regain sensitivity while resistant mutants maintain resistance [4] [2].

- Perform genetic analysis to identify resistance mutations or genes in surviving populations [7].

Mechanistic Pathways of Persister Formation and Awakening

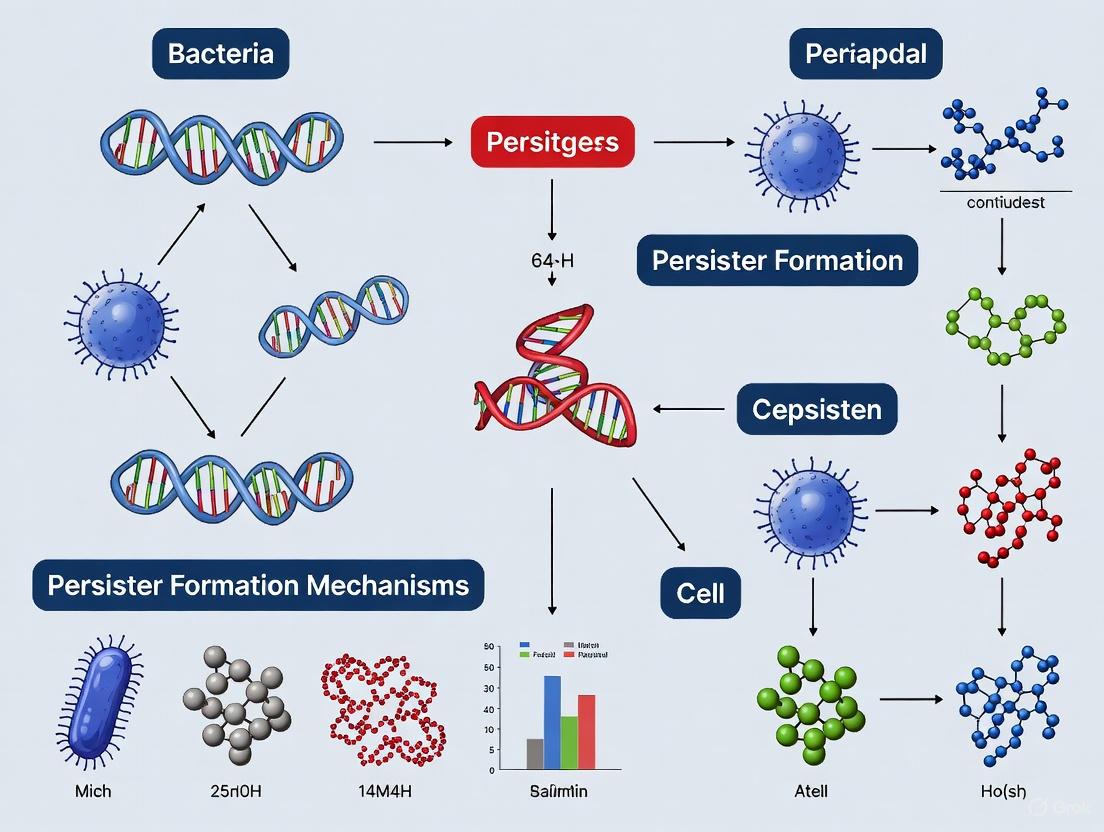

The formation and resuscitation of persister cells can be visualized as a dynamic cycle of entry into and exit from the persistent state. The following diagram illustrates the key regulatory pathways and environmental triggers that govern these transitions:

Diagram 1: Regulatory pathways of persister cell formation and awakening. Environmental stressors trigger persistence through toxin-antitoxin systems and (p)ppGpp signaling, leading to metabolic shutdown. Awakening occurs stochastically or in response to environmental signals.

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Studying Persistence and Resistance

| Reagent/Technique | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bactericidal Antibiotics | Ciprofloxacin (0.1 mg/mL), Gentamicin (0.1-0.4 mg/mL) [6] | Time-kill assays to distinguish persisters via biphasic killing curves [6] |

| Culture Media | Mueller-Hinton Agar/Broth, Luria-Bertani (LB) Broth [6] | Standardized antimicrobial susceptibility testing and bacterial cultivation |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | PCR primers for persistence genes (mazF, hipA, relE) [6] | Detection of toxin-antitoxin system genes associated with persistence |

| Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing | EUCAST/CLSI recommended discs and concentrations [6] | Determination of MIC values to distinguish resistance from persistence |

| DNA Sequencing Technologies | Whole-genome sequencing, long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio, Nanopore) [7] | Identification of genetic mutations conferring bona fide resistance |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | GFP reporters under ribosomal promoters [4] | Isolation of dormant cells based on reduced metabolic activity |

Interplay and Clinical Implications

While distinct phenomena, persistence and resistance interact in clinically significant ways. Persister cells can serve as a reservoir for resistance development by surviving antibiotic treatment and accumulating resistance mutations during transient growth phases [2]. This dynamic is particularly problematic in biofilm-associated infections, where persisters are enriched and protected within the biofilm structure [3] [2].

Therapeutic strategies must address both mechanisms simultaneously. Promising approaches include:

- Combination therapies that pair conventional antibiotics with compounds that disrupt persistence mechanisms [1].

- Anti-biofilm agents that enhance antibiotic penetration and target the protected niches where persisters reside [3] [2].

- Metabolic stimulation to "awaken" persisters before antibiotic administration, making them vulnerable to treatment [5].

Understanding the distinctions and interactions between phenotypic persistence and genetic resistance remains crucial for developing more effective treatments for persistent bacterial infections and addressing the ongoing antibiotic crisis.

Bacterial persisters are a subpopulation of genetically drug-susceptible, quiescent cells that survive exposure to lethal stresses, including antibiotics, and can regrow once the stress is removed [1] [8]. These cells are not antibiotic-resistant mutants but rather phenotypic variants that exhibit transient tolerance [8] [9]. Their presence is a significant clinical challenge, underlying chronic, relapsing infections such as tuberculosis, recurrent urinary tract infections, and biofilm-associated infections [1] [8]. The "Dormancy Spectrum" concept refers to the continuum of metabolic states that persisters can occupy, ranging from shallow to deep dormancy [1]. This guide objectively compares the classical types of persisters—Type I and Type II—and introduces the emerging concept of stress-induced, active tolerance mechanisms that some classifications refer to as Type III persisters.

Comparative Analysis of Persister Types

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the primary persister types, providing a clear, at-a-glance comparison for researchers.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Bacterial Persister Types

| Feature | Type I Persisters | Type II Persisters | Type III Persisters (Stress-Induced) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Inducer | External environmental triggers (e.g., stationary phase, carbon starvation) [1] [10] | Spontaneous, stochastic switching during active growth [1] [10] | Specific environmental stresses (e.g., DNA damage, oxidative stress) [5] |

| Formation Kinetics | Programmed, synchronized response to a signal [10] | Continuous, stochastic formation throughout growth [10] | Induced rapidly in response to a specific stressor [5] |

| Metabolic State | Non-growing or metabolically stagnant [1] | Slow-growing or metabolically attenuated [1] | Can exhibit targeted inactivation of cellular processes without global dormancy [5] |

| Key Molecular Mechanisms | Stringent response, (p)ppGpp accumulation, RpoS [4] | Stochastic variation in toxin-antitoxin (TA) system expression (e.g., HipA) [10] [4] | SOS response (e.g., TisB), membrane depolarization, active efflux pumps [5] [11] |

| Typical Proportion in Population | Can be a significant fraction (e.g., in stationary phase) [4] | A very small fraction (e.g., 1 in 10^5–10^6 in E. coli) [10] | Variable, depends on the nature and intensity of the stress [5] |

| Regrowth Kinetics | Synchronized, upon removal of the inducing signal [10] | Stochastic awakening [10] | Awakening can be stochastic or triggered by environmental cues [5] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The formation of persister cells is governed by a complex network of biochemical pathways. The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathways and their logical relationships for Type I, II, and III persister formation.

Diagram 1: Signaling Pathways in Persister Formation. This diagram maps the primary molecular pathways leading to the formation of Type I (induced by external triggers), Type II (stochastic), and Type III (stress-induced) persister cells. Key processes include the stringent response, toxin-antitoxin system imbalance, and specific stress responses like the SOS pathway.

Detailed Pathway Analysis

Type I Pathways: The stringent response is a master regulator of Type I persistence. Nutrient limitation leads to the rapid accumulation of the alarmone (p)ppGpp, which orchestrates a dramatic reprogramming of cellular metabolism [4]. This includes shutting down ribosome synthesis and activating the general stress response sigma factor RpoS, collectively pushing the cell into a dormant, tolerant state [4].

Type II Pathways: The formation of Type II persisters is largely driven by the stochastic overexpression of toxin proteins from chromosomal Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) systems. In a small subset of cells, random fluctuations in gene expression can lead to a temporary imbalance where a toxin (e.g., HipA, MqsR, RelE) overwhelms its cognate labile antitoxin [10] [4]. These toxins then inhibit vital processes like translation (e.g., MqsR cleaves mRNA) or ATP production, inducing a dormant state [4].

Type III Pathways: Emerging research highlights that dormancy is not always required for tolerance. Some cells survive through active, targeted mechanisms induced by stress [5]. For example, DNA damage from fluoroquinolone antibiotics activates the SOS response, which upregulates the type I TA toxin TisB [11]. TisB integrates into the membrane, disrupting the proton motive force (PMF) and causing ATP depletion. This directly protects the cell by reducing antibiotic uptake (e.g., of aminoglycosides) and corrupting the drug's target [5] [11].

Experimental Protocols for Persister Research

Protocol 1: Isolation and Quantification of Persisters

The gold standard for measuring persistence is the biphasic killing curve assay [8].

- Culture Preparation: Grow a bacterial culture to the desired growth phase (e.g., mid-logarithmic or stationary phase). For Type I persisters, an inoculum from stationary phase is often used [4].

- Antibiotic Challenge: Expose the culture to a lethal concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., 5-10x MIC of ampicillin or ciprofloxacin). Maintain the culture under growth conditions with aeration.

- Viable Count Enumeration:

- At time zero (immediately before antibiotic addition) and at regular intervals thereafter (e.g., 1h, 2h, 4h, 8h, 24h), remove aliquots from the culture.

- Wash the cells to remove the antibiotic by centrifugation and resuspension in fresh phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or medium.

- Serially dilute the samples and spot or plate them onto antibiotic-free LB agar plates.

- Incubate the plates for 16-48 hours until colonies appear.

- Data Analysis: Plot the number of colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter against time. The plot will show a rapid initial killing phase (death of normal cells) followed by a plateau or a much slower second killing phase (survival of persisters). The persister frequency is calculated as the CFU/mL at the plateau divided by the initial CFU/mL [8].

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Analysis of Type II Persisters

This protocol, based on Balaban et al. (2004), allows for the direct observation of stochastic persister formation and awakening [10].

- Microfluidic Setup: Use a microfluidic device designed to trap and continuously perfuse fresh medium over individual bacterial cells.

- Cell Loading and Monitoring: Load a dilute culture of bacteria into the device. Continuously flow fresh, rich medium through the device to encourage growth. Monitor cell division in real-time using time-lapse microscopy.

- Antibiotic Exposure and Identification: After a period of growth, switch the medium to one containing a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin). Continue perfusion and observation. Normal, growing cells will lyse. Cells that were non-growing or slow-growing at the time of antibiotic application will not lyse and are identified as persisters.

- Awakening Kinetics: After a defined period, switch back to antibiotic-free medium. Monitor the trapped, surviving persister cells to record the time at which they resume division ("awakening"). This demonstrates the stochastic and reversible nature of the Type II persister state [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key reagents and their applications in persister cell research, providing a practical resource for experimental design.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Persister Cell Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin / Ofloxacin | DNA-damaging antibiotics (fluoroquinolones) that induce the SOS response. | Used to study stress-induced (Type III) persistence and the role of the TisB toxin [11]. |

| Ampicillin | A bactericidal β-lactam antibiotic that inhibits cell wall synthesis. | Commonly used in biphasic killing assays to isolate and enumerate persisters, as it effectively kills growing cells [4]. |

| HipA7 Mutant Strain | A gain-of-function mutant in the HipA toxin of E. coli. | Serves as a high-persistence (Hip) model strain, producing ~1000x more Type II persisters than wild-type, useful for mechanistic studies [10]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | A technique to isolate cell subpopulations based on fluorescence. | Used with a GFP reporter under a ribosomal promoter to isolate dormant, non-fluorescent persister cells from a larger population for transcriptomic analysis [4]. |

| Lon Protease Mutant | A mutant deficient in the ATP-dependent protease Lon. | Used to study Type II TA systems, as Lon degrades labile protein antitoxins; its deletion reduces persistence by preventing toxin activation [4]. |

Understanding the distinctions and overlaps between Type I, II, and III persisters is critical for developing effective therapies against chronic infections. While Type I and II represent different routes to a dormant, multidrug-tolerant state, Type III mechanisms suggest that active cellular responses can also confer tolerance without global shutdown. Future research must focus on identifying the specific inducers and molecular effectors of these pathways during human infection. The redundancy in persister formation mechanisms poses a significant challenge, implying that combination therapies targeting multiple pathways simultaneously will be essential to eradicate these resilient cells. The experimental tools and comparative data provided in this guide offer a foundation for such advanced therapeutic development.

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules are small genetic operons ubiquitous in bacterial genomes, functioning as master regulators of bacterial persistence across diverse species [12]. These universal molecular triggers consist of a stable toxin protein that can inhibit essential cellular processes and a corresponding labile antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin's activity [12] [13]. Under normal growth conditions, antitoxins effectively counteract their cognate toxins; however, during environmental stress such as antibiotic exposure, nutrient limitation, or immune system attack, antitoxins are rapidly degraded, allowing toxins to induce a transient dormant state [12] [14]. This dormancy creates persister cells—metabolically inactive variants that survive lethal antibiotic treatment despite genetic susceptibility, contributing significantly to chronic and recurrent infections [1] [15].

The abundance and diversity of TA modules vary considerably across bacterial pathogens, with notable enrichment in persistent pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which carries 88 TA modules, compared to only 5 in the relatively fast-growing non-pathogen Mycobacterium smegmatis [12]. This correlation between TA module abundance and pathogenic persistence underscores their clinical importance as key regulators of bacterial survival strategies. This guide provides a systematic comparison of TA module functions, distributions, and experimental approaches across major bacterial species, offering researchers a comprehensive resource for investigating these universal molecular triggers of persistence.

TA Module Classification and Comparative Mechanisms

TA systems are currently classified into eight distinct types (I-VIII) based on the nature of the antitoxin and its mechanism of toxin neutralization [12] [16]. This classification reflects the remarkable diversity of molecular strategies bacteria employ to regulate persistence activation.

Table 1: Classification of Toxin-Antitoxin Systems and Their Mechanisms

| Type | Toxin Nature | Antitoxin Nature | Mechanism of Neutralization | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Protein | RNA (antisense) | Antitoxin RNA binds toxin mRNA, inhibiting translation [16] [13] | First discovered type; post-transcriptional regulation [14] |

| II | Protein | Protein | Antitoxin protein binds and inhibits toxin directly [12] [16] | Most extensively studied; transcriptional autoregulation [12] [17] |

| III | Protein | RNA | Antitoxin RNA binds toxin protein directly [16] | RNA-protein interaction; macromolecular complex formation [16] |

| IV | Protein | Protein | Antitoxin competes with toxin for target binding [16] | Substrate competition rather than direct toxin binding [16] |

| V | Protein | Protein | Antitoxin cleaves toxin mRNA [16] | Enzymatic RNA degradation as neutralization mechanism [16] |

| VI | Protein | Protein | Antitoxin mediates proteolytic degradation of toxin [16] | Promotes toxin destruction via proteolysis [16] |

| VII | Protein | Protein | Antitoxin enzymatically neutralizes toxin activity [16] | Recently described enzymatic neutralization mechanism [16] |

| VIII | RNA | RNA (antisense) | Antitoxin RNA binds toxin RNA directly [16] | RNA-RNA interaction; both components are RNAs [16] |

Type II TA systems represent the most extensively characterized and abundant class, particularly in pathogenic bacteria [16]. These systems feature protein antitoxins that typically contain two functional domains: a DNA-binding domain for transcriptional regulation and a toxin-binding domain that directly inhibits toxin activity through protein-protein interaction [12] [17]. The regulatory sophistication of type II systems is exemplified by "conditional cooperativity," where the toxin acts as a corepressor or derepressor depending on the cellular toxin:antitoxin ratio, creating a finely tuned responsive system [18].

Table 2: Distribution of Major Type II TA Families Across Bacterial Pathogens

| TA Family | Primary Toxin Target | Key Bacterial Species | Pathophysiological Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| VapBC | Translation (mRNA cleavage) [12] | M. tuberculosis (50 loci), P. aeruginosa [12] [16] | Major TA family; stress adaptation, persistence [12] |

| MazEF | Translation (mRNA cleavage) [12] | E. coli, M. tuberculosis (10 loci), S. aureus [12] [13] | Programmed cell death, stress response [12] |

| RelBE | Translation (ribosome-dependent mRNA cleavage) [12] | E. coli, V. cholerae [12] | Nutrient stress response, persistence [12] |

| HipBA | Translation (EF-Tu phosphorylation) [12] | E. coli (hipA7 mutants show 1000× higher persistence) [14] | High-persistence mutants, multidrug tolerance [14] |

| ParDE | DNA replication (gyrase inhibition) [12] | E. coli, various pathogens [12] | Plasmid maintenance, stress response [12] |

| CcdAB | DNA replication (gyrase inhibition) [12] | E. coli (F-plasmid) [12] | Plasmid stabilization, post-segregational killing [12] |

| HigBA | Translation [12] | P. aeruginosa, E. coli [16] | Biofilm formation, antibiotic tolerance [16] |

| Hha/TomB | Unknown | P. aeruginosa [16] | Recently identified in pan-genome analysis [16] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental operational principles shared across TA system types, highlighting how environmental stress triggers the activation of toxins and subsequent persistence formation:

Species-Specific TA Module Distribution and Functional Specialization

The distribution and abundance of TA modules vary dramatically across bacterial species, reflecting adaptation to specific environmental niches and pathogenic lifestyles. Pathogenic species typically harbor significantly more TA modules than their non-pathogenic relatives, suggesting an important role in virulence and host adaptation [12].

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

M. tuberculosis represents an extreme example of TA module enrichment, with 88 identified TA modules that contribute to its remarkable ability to establish persistent infections [12]. This abundance contrasts sharply with the relatively fast-growing Mycobacterium smegmatis, which possesses only 5 TA modules [12]. The M. tuberculosis TA arsenal includes 50 VapBC family systems and 10 MazEF family systems, providing multiple redundant pathways to enter dormancy during antibiotic treatment or immune system pressure [12]. This extensive TA network likely explains the pathogen's exceptional capacity for latent infection and treatment recalcitrance.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pan-genome analysis of P. aeruginosa has revealed a diverse TA repertoire that includes both well-characterized and novel systems [16]. Beyond established type II systems like ParAB, RelBE, HigBA, and MazEF, genomic mining has identified previously unreported TA modules in this species, including hok-sok, cptA-cptB, cbeA-cbtA, tomB-hha, and ryeA-sdsR [16]. Importantly, approximately 16% of antibiotic resistance genes in P. aeruginosa are located near TA modules, suggesting potential co-regulation or coordinated dissemination through mobile genetic elements [16]. This genetic architecture facilitates the development of multidrug-resistant persistent infections, particularly in clinical settings.

Escherichia coli

E. coli possesses more than ten well-characterized type II TA systems, including relE-relB, yoeB-yefM, hipA-hipB, and mqsR-mqsA, which have served as models for understanding TA regulation and function [17]. The hipBA system is particularly notable, as hipA7 mutants produce persisters at a frequency of 1% compared to 0.0001% in wild-type strains when exposed to ampicillin [14]. This 10,000-fold increase in persistence frequency demonstrates the critical role specific TA loci play in mediating antibiotic tolerance. Research in E. coli has also revealed that the simultaneous deficiency of five or more type II TA modules significantly reduces persister formation during exponential growth phase, indicating functional redundancy across multiple systems [14].

Other Bacterial Pathogens

TA modules have been identified and characterized in numerous other pathogens with varying persistence capabilities. Xenorhabdus nematophila, an entomopathogen, possesses 39 TA modules that facilitate survival in insects through the formation of non-replicating persisters [12]. Clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus show varied TA system distributions, though evidence suggests their role in persistence may differ from Gram-negative organisms [14]. Additionally, well-characterized TA systems exist in non-human pathogens including Agrobacterium tumefasciens, Erwinia amylovora, Xanthomonas species, and Acetobacter pasteurianus, indicating the universal conservation of these mechanisms across the bacterial kingdom [12].

Experimental Approaches for TA System Investigation

Genomic Mining and Bioinformatics Analysis

Advanced genomic approaches enable comprehensive identification of TA modules across bacterial species. As demonstrated in P. aeruginosa research, reassembling genomes from sequencing data (e.g., from NCBI SRA database) allows detection of abundant TA homologs [16]. Subsequent pan-genome analysis across thousands of isolates reveals TA diversity and distribution patterns. Bioinformatic tools like TADB2 provide curated TA sequences and annotations, though current databases show a strong bias toward type II systems due to research focus [16]. Essential reagents for these approaches include:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for TA System Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| TADB2 Database | Curated TA sequence database | Reference for identifying known TA modules and families [16] |

| BRET Assay Components | Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer | High-throughput screening of TA protein interactions [19] |

| Lon Protease | ATP-dependent protease | Studying antitoxin degradation in type II systems [14] |

| RNA-Seq | Transcriptome profiling | Monitoring TA gene expression dynamics [17] |

| Microfluidic Culture | Single-cell analysis | Observing persister formation and resuscitation [1] |

| Fluorescent Protein Fusions | Protein localization and interaction | Visualizing toxin-antitoxin dynamics in live cells [19] |

Molecular Interaction Methodologies

Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) provides a powerful high-throughput screening method for investigating TA protein interactions and identifying compounds that disrupt these interactions [19]. In this approach, the epsilon antitoxin gene is fused to luciferase (Luc-epsilon) and the zeta toxin gene to GFP (zeta-GFP), enabling quantification of interaction dynamics through energy transfer measurements [19]. Molecular dynamics studies can further predict critical residues involved in toxin-antitoxin interactions, such as Asp18 and/or Glu22 in the epsilon-zeta system, which can be validated through site-directed mutagenesis [19].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow for investigating TA systems, from identification to functional characterization:

Mathematical Modeling of TA Dynamics

Mathematical modeling provides valuable insights into TA system dynamics and their relationship to persistence. Ordinary differential equation (ODE) models can describe the core regulatory logic of type II TA systems, incorporating key features such as toxin and antitoxin production rates, complex formation, and toxin-induced growth modulation [17]. These models typically account for the fundamental characteristics of TA systems: toxin and antitoxin are expressed by neighboring genes; toxins are more stable than antitoxins; the TA complex inhibits its own production; and toxin presence inhibits cell growth [17].

Stochastic models that include conditional cooperativity demonstrate how rare, extreme stochastic spikes in free toxin levels can create persister cells, with spike amplitude determining persister state duration [18]. These models reveal that free toxin levels are primarily controlled through toxin sequestration in TA complexes of various stoichiometry rather than by gene regulation alone [18]. Parameterizing these models with experimental data from specific TA pairs allows quantitative comparison of system dynamics across different bacterial species and environmental conditions [17].

TA Modules as Therapeutic Targets

The central role of TA modules in bacterial persistence makes them attractive targets for novel antibacterial strategies [12] [19]. Proposed approaches include artificial activation of toxin activity through compounds that disrupt toxin-antitoxin interactions, acceleration of antitoxin degradation, repression of antitoxin transcription or translation, and delivery of recombinant toxin RNA/DNA [16] [19]. Successful proof-of-concept studies have demonstrated the feasibility of these approaches. For example, in the Streptococcus pyogenes pSM19035-encoded epsilon-zeta TA system, a compound that disrupts the epsilon-zeta interaction could serve as an effective antimicrobial agent by freeing the zeta toxin to induce growth arrest [19].

Additional strategies include activating Lon protease to degrade antitoxins more rapidly or using antisense oligonucleotides to target antitoxin RNAs in type I systems [16]. The relatively narrow phylogenetic distribution of some TA systems offers potential for species-specific antimicrobial development, potentially minimizing disruption to beneficial microbiota [16]. As mathematical models improve predictions of TA system dynamics across bacterial species, targeted therapeutic interventions can be designed to activate these universal molecular triggers specifically in pathogenic contexts, potentially overcoming the limitations of conventional antibiotics against persistent infections.

Bacterial persistence represents a significant challenge in treating chronic infections, as persister cells can survive antibiotic treatment without genetic resistance [1] [4]. These dormant bacterial subpopulations exhibit remarkable tolerance to antimicrobial agents through metabolic dormancy and phenotypic heterogeneity [1] [20]. Central to this survival mechanism is the stringent response, masterfully orchestrated by the guanosine nucleotides (p)ppGpp (guanosine pentaphosphate and tetraphosphate) [21] [22]. This review comprehensively examines the role of (p)ppGpp as the primary regulator of bacterial dormancy, comparing its function across bacterial species and contextualizing its influence within the broader framework of persistence mechanisms.

The stringent response constitutes an evolutionarily conserved adaptation to nutrient limitation and environmental stresses [23]. When activated, it triggers a profound transcriptional reprogramming that shifts cellular priorities from growth and proliferation to survival and maintenance [24]. This response is characterized by the rapid accumulation of (p)ppGpp, which serves as a master regulatory alarmone that coordinates bacterial physiology to enhance survival under adverse conditions [21] [25]. Understanding the precise mechanisms through which (p)ppGpp influences entry into dormancy provides critical insights for developing novel therapeutic strategies against persistent infections.

Molecular Mechanisms of (p)ppGpp Signaling

(p)ppGpp Synthesis and Hydrolysis

The metabolism of (p)ppGpp is governed by enzymes belonging to the RelA/SpoT homolog (RSH) family [21] [23]. In Escherichia coli, a model Gram-negative organism, this system comprises two principal enzymes: RelA, which functions primarily as a (p)ppGpp synthetase, and SpoT, a bifunctional enzyme possessing both synthetic and hydrolytic capabilities [23] [25]. These enzymes meticulously maintain cellular (p)ppGpp concentrations, ensuring appropriate responses to environmental cues.

RelA is ribosome-associated and becomes activated upon binding of uncharged tRNA to the ribosomal A-site during amino acid starvation [25]. This activation triggers the synthesis of (p)ppGpp from GTP/GDP and ATP [21]. In contrast, SpoT responds to diverse stress signals, including fatty acid starvation, carbon source limitation, and oxidative stress [21] [25]. The functional diversity of RSH enzymes across bacterial species significantly influences how different pathogens regulate their stringent responses [21].

Table: (p)ppGpp Metabolic Enzymes Across Bacterial Species

| Organism | Enzyme Type | Synthetic Function | Hydrolytic Function | Primary Activators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) | RelA | Primary synthetase | Non-functional | Amino acid starvation (uncharged tRNA) |

| SpoT | Weak synthetase | Primary hydrolase | Fatty acid starvation, carbon limitation | |

| Gram-positive bacteria | Rel | Bifunctional (both activities) | Bifunctional (both activities) | Multiple nutrient limitations |

| Various pathogens | SAS (Small Alarmone Synthetase) | Monofunctional synthetase | None | Stress-specific signals |

(p)ppGpp-Mediated Transcriptional Regulation

(p)ppGpp exerts its profound effects on bacterial physiology through sophisticated mechanisms of transcriptional control. In Gamma-proteobacteria including E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, (p)ppGpp binds directly to the RNA polymerase (RNAP), often with the cofactor DksA, to modify promoter specificity and stability [24] [25]. This interaction preferentially represses stable RNA transcription (rRNA and tRNA) while activating stress response genes [21] [24].

The regulatory influence of (p)ppGpp extends beyond RNAP interaction. In many Gram-positive bacteria, (p)ppGpp indirectly controls transcription by modulating cellular GTP pools [25]. High (p)ppGpp levels inhibit enzymes involved in GTP biosynthesis, thereby reducing GTP concentrations that in turn affect transcription factors like CodY that sense nutrient sufficiency [25]. This mechanism enables a coordinated shutdown of anabolic processes during nutrient limitation.

Recent findings in P. aeruginosa demonstrate that (p)ppGpp implements a graded transcriptional response proportional to stress severity rather than a simple binary switch [24]. Under mild stress conditions (100 μM SHX), approximately 4% of the genome shows differential expression, while acute stress (1000 μM SHX) reprograms up to 25% of all genes [24]. This layered response enables precise physiological adjustments matched to environmental challenges.

Diagram: The (p)ppGpp Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Bacterial Persistence. This diagram illustrates how various environmental stressors activate RSH enzymes, leading to (p)ppGpp accumulation and subsequent physiological changes that promote dormancy and antibiotic tolerance.

Comparative Analysis of (p)ppGpp Function Across Bacterial Species

Gram-negative Bacteria

In Escherichia coli, (p)ppGpp accumulation triggers a comprehensive physiological transformation that promotes survival under adverse conditions. The alarmone directly inhibits DNA primase, effectively halting DNA replication initiation [21]. Simultaneously, it represses rRNA and tRNA synthesis through direct interaction with RNA polymerase, reducing the protein synthesis capacity of the cell [21]. These coordinated actions induce a state of metabolic quiescence that underlies antibiotic tolerance [21] [4].

Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibits a graded response to (p)ppGpp accumulation that correlates with stress severity [24]. At low concentrations, (p)ppGpp primarily suppresses motility and pyocyanin production, promoting a transition to sessile lifestyle. Intermediate levels upregulate biofilm-related genes while downregulating virulence factors. High (p)ppGpp concentrations induce multidrug tolerance in biofilm populations through comprehensive transcriptional reprogramming affecting up to 25% of the genome [24]. This sophisticated layering of responses enables precise adaptation to environmental challenges.

In Salmonella enterica, (p)ppGpp is essential for intracellular survival within acidified vacuoles of macrophages [21]. (p)ppGpp-deficient mutants show severely impaired persistence in mouse infection models, highlighting the critical role of the stringent response in bacterial pathogenesis [21].

Gram-positive Bacteria

Gram-positive organisms typically possess a single bifunctional RSH enzyme (Rel) that combines both synthetic and hydrolytic activities [21] [22]. This architectural difference from the Gram-negative system may reflect alternative regulatory strategies for persistence formation. Additionally, Gram-positive bacteria frequently employ GTP pool modulation as a key regulatory mechanism, where (p)ppGpp inhibits GTP synthesis, thereby affecting cellular processes controlled by GTP-sensitive transcription factors [25].

Table: Comparative Analysis of (p)ppGpp-Mediated Persistence Mechanisms

| Mechanistic Feature | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | Gram-positive Bacteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSH Enzyme Architecture | Two enzymes: RelA (synthetase) and SpoT (bifunctional) | Similar to E. coli | Single bifunctional Rel enzyme |

| Primary Transcriptional Control | Direct RNAP binding with DksA | Direct RNAP binding with DksA | GTP pool modulation & CodY regulation |

| Metabolic Consequences | Inhibition of DNA primase; rRNA repression | Graded transcriptional response | Reduced GTP pools; ribosomal shutdown |

| Persistence Induction | Toxin-antitoxin activation; metabolic arrest | Biofilm-enhanced tolerance; motility suppression | Stress adaptation; sporulation in some species |

| Virulence Modulation | Host invasion capability | Quorum sensing integration; virulence factor regulation | Virulence gene expression control |

Interplay Between (p)ppGpp and Other Persistence Mechanisms

Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems

(p)ppGpp plays an integral role in the activation and regulation of toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules, which constitute another fundamental mechanism of bacterial persistence [21] [22]. These systems typically consist of a stable toxin that disrupts essential cellular processes and a labile antitoxin that counteracts the toxin's effects [4] [22]. Under stress conditions, (p)ppGpp signaling promotes the activation of TA systems through both direct and indirect mechanisms.

The HipAB system represents a well-characterized example of (p)ppGpp-TA system integration [22]. The HipA toxin functions as a protein kinase that phosphorylates and inhibits glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (GltX), resulting in uncharged tRNA accumulation that activates RelA-mediated (p)ppGpp synthesis [22]. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where TA system activation amplifies the stringent response, which in turn promotes further persistence induction.

Other TA systems, including MqsR/MqsA and TisB/IstR-1, are similarly interconnected with (p)ppGpp signaling [4]. The MqsR toxin functions as an mRNA interferase that cleaves cellular transcripts at GCU sites, effectively halting translation and inducing dormancy [4]. The TisB toxin dissipates the proton motive force and reduces ATP levels, creating a metabolically dormant state [4]. (p)ppGpp influences the expression and activity of these systems, creating a coordinated network of persistence mechanisms.

Biofilm Formation and Metabolic Adaptation

(p)ppGpp serves as a critical regulator of biofilm formation across multiple bacterial species [21] [24]. In both E. coli and P. aeruginosa, (p)ppGpp-deficient strains exhibit severely impaired biofilm development and enhanced antibiotic sensitivity [21]. The alarmone promotes biofilm formation through multiple pathways, including exopolysaccharide production, adhesion expression, and quorum sensing integration [24] [22].

Within biofilms, bacterial cells encounter gradients of nutrients and oxygen that create microenvironments with varying metabolic activity [20]. (p)ppGpp enables bacterial adaptation to these heterogeneous conditions by implementing a spatially coordinated stringent response [24]. Cells in nutrient-poor regions of biofilms exhibit elevated (p)ppGpp levels, resulting in reduced metabolic activity and enhanced antibiotic tolerance compared to their nutrient-replete counterparts [20].

The metabolic control exerted by (p)ppGpp extends to energy metabolism regulation. The alarmone modulates ATP production through effects on oxidative phosphorylation and carbon metabolism pathways [24] [20]. Reduced ATP levels contribute to persistence by promoting the formation of protein aggregates (aggresomes) that sequester essential enzymes for replication, transcription, and translation [22]. This aggregation mechanism establishes a self-reinforcing dormant state that can persist even after stress removal.

Experimental Approaches for Studying (p)ppGpp-Mediated Persistence

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Research on (p)ppGpp and bacterial persistence employs a diverse array of experimental approaches designed to quantify persistence levels, measure alarmone concentrations, and manipulate the stringent response. The following protocols represent standardized methodologies in the field.

Amino Acid Starvation Induction Using Serine Hydroxamate (SHX):

- Grow bacterial cultures to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.3-0.5) in appropriate medium [24]

- Add SHX at concentrations ranging from 100-1000 μM to induce mild to acute stringent response [24]

- Incubate for 30 minutes to allow (p)ppGpp accumulation

- Monitor growth inhibition and (p)ppGpp levels

- For transcriptomic studies, collect cells after 30 minutes of SHX treatment for RNA extraction and sequencing [24]

(p)ppGpp Quantification Method:

- Extract nucleotides from bacterial cultures using cold formic acid (0.5 M final concentration) [24]

- Separate nucleotides via polyethyleneimine-cellulose thin-layer chromatography

- Develop chromatography in 1.5 M KH2PO4 buffer (pH 3.6)

- Visualize and quantify (p)ppGpp spots using phosphorimaging or autoradiography

- Normalize (p)ppGpp levels to total guanine nucleotide pool (ppGpp + pppGpp + GTP) [24]

Persister Cell Isolation and Quantification:

- Grow cultures to desired growth phase (exponential or stationary)

- Treat with bactericidal antibiotics at 5-10× MIC for 3-5 hours

- Remove antibiotics by washing or dilution

- Plate on fresh medium to enumerate surviving colony-forming units (CFUs)

- Calculate persister frequency as (CFU after antibiotic treatment / total CFU before treatment) × 100 [1] [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagents for Studying (p)ppGpp-Mediated Persistence

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stringent Response Inducers | Serine Hydroxamate (SHX) | Induces amino acid starvation via seryl-tRNA synthetase inhibition [24] |

| L-1,4-Diaminobutyrate | Lysine starvation analog for stringent response induction | |

| Analytical Tools | Polyethyleneimine-cellulose TLC plates | Separation and quantification of (p)ppGpp nucleotides [24] |

| HPLC-MS systems | High-sensitivity detection and quantification of alarmones | |

| Genetic Tools | relA/spoT knockout strains | Study (p)ppGpp-deficient phenotypes [21] [23] |

| (p)ppGpp0 strains (ΔrelA ΔspoT) | Complete (p)ppGpp-null mutants for functional studies [21] | |

| SAS/SAH expression vectors | Investigate small alarmone synthetase/hydrolase functions [21] | |

| Detection Assays | RNAP binding assays | Measure (p)ppGpp-RNAP interactions using EMSA or SPR |

| Transcriptomic microarrays/RNA-seq | Comprehensive analysis of stringent response regulons [24] |

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for (p)ppGpp Research. This diagram outlines the key methodological steps for investigating the role of (p)ppGpp in bacterial persistence, from strain preparation through final analysis.

Therapeutic Implications and Future Perspectives

The central role of (p)ppGpp in bacterial persistence makes it an attractive therapeutic target for combating chronic and recurrent infections [21] [22]. Innovative treatment strategies focusing on (p)ppGpp inhibition or modulation represent promising approaches to enhance the efficacy of conventional antibiotics.

One strategic approach involves developing small molecule inhibitors that target (p)ppGpp synthesis or function [21]. Compounds that inhibit RelA/SpoT synthetase activity could prevent the induction of the stringent response, thereby reducing persister formation and sensitizing bacteria to antibiotic treatment [21] [20]. Alternatively, molecules that activate (p)ppGpp hydrolase activity could accelerate alarmone turnover, limiting its physiological effects [23].

Metabolite-based adjuvant therapy represents another promising strategy [20]. Specific metabolites, including mannitol, pyruvate, and certain amino acids, can reactivate metabolic processes in persistent cells, restoring their susceptibility to antibiotics [20]. For instance, mannitol has been shown to enhance aminoglycoside sensitivity in P. aeruginosa biofilms by restoring proton motive force and drug uptake [20]. Similarly, exogenous adenosine and guanosine can increase tetracycline sensitivity against persister cells [20].

A more comprehensive understanding of the graded response mechanism of (p)ppGpp signaling [24] opens possibilities for fine-tuned interventions that modulate rather than completely abolish the stringent response. Such approaches might avoid potential resistance development associated with complete pathway inhibition while still effectively reducing persistence rates.

As research advances, targeting (p)ppGpp-mediated persistence holds significant promise for addressing the ongoing challenge of antibiotic treatment failure in chronic infections. The integration of (p)ppGpp inhibitors with conventional antibiotics may provide a synergistic strategy to eradicate bacterial populations completely, preventing relapses and reducing the emergence of genetic resistance.

Bacterial persisters are a transient, non-growing, and phenotypically variant subpopulation within a genetically susceptible strain that exhibits remarkable tolerance to high doses of conventional antibiotics. These cells are not resistant mutants but can resume growth once antibiotic pressure ceases, leading to recurrent infections and therapeutic failure [26] [1]. Critically, the biofilm lifestyle provides an ideal sanctuary for the formation and protection of these persister cells. Biofilms are structured microbial communities encased in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix that adhere to biotic or abiotic surfaces [27]. This matrix creates a protected microenvironment where gradients of nutrients, oxygen, and metabolic waste products generate physiological heterogeneity, fostering the emergence and survival of persisters [26] [28]. The synergy between biofilms and persisters represents a major clinical challenge, underlying approximately 80% of chronic bacterial infections that are recalcitrant to standard antibiotic therapies [26] [29]. This review systematically compares the mechanisms by which biofilm structures and metabolic pathways collaboratively protect persister cells across major bacterial pathogens, providing a foundational analysis for antimicrobial development.

Comparative Architecture: Biofilm Structures Across Pathogens

The architectural complexity of biofilms varies significantly across bacterial species, influencing their capacity to harbor persisters. The protective EPS matrix composition differs notably between Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens, though all share common functional characteristics that contribute to persistence.

Table 1: Comparative Biofilm Matrix Components and Persister Protection Mechanisms in ESKAPE Pathogens

| Pathogen | Key Matrix Components | Structural Features | Primary Persister Protection Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Pel, Psl alginate, eDNA, proteins | Mushroom-shaped microcolonies (glucose) or flat structures (citrate) | Matrix barrier delaying antibiotic penetration; steep oxygen gradient creating anaerobic niches [28] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | PIA/PNAG, protein/eDNA, fibrin, amyloid fibers | Polysaccharide, protein-based, fibrin-dependent, or amyloid structures | Multiple biofilm archetypes adapt to environmental conditions; fibrin shield from immune recognition [28] [29] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Capsular polysaccharide, cellulose, poly-N-acetylglucosamine | Strong biofilm former with high matrix production | Enhanced biofilm formation correlates with carbapenem resistance; matrix impedes antibiotic diffusion [30] |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Extracellular polysaccharides, proteins, eDNA | Robust biofilm architecture on abiotic surfaces | High-level resistance to cephalosporins and carbapenems linked to biofilm capability [30] |

| Enterococcus faecium | Polysaccharides, proteins | Hospital-adapted biofilm formation on medical devices | High multi-drug resistance rates (90%) within biofilm populations [30] |

The biofilm lifecycle proceeds through defined stages—initial attachment, irreversible attachment, microcolony formation, maturation, and dispersion—each contributing differently to persister dynamics [28]. Initial attachment involves reversible adhesion to preconditioned surfaces through weak interactions like van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions [27]. During irreversible attachment, bacteria produce EPS that anchors them firmly to the surface and to each other. The maturation phase establishes the three-dimensional architecture with characteristic water channels that facilitate nutrient distribution and waste removal [27] [31]. Crucially, the biofilm interior develops chemical gradients of nutrients and oxygen that create heterogeneous microenvironments with varying metabolic activities [26]. This physiological heterogeneity is fundamental to persister development, as subpopulations in nutrient-deprived, oxygen-limited regions enter dormant or slow-growing states that are tolerant to antibiotics [26] [28].

Figure 1: The Biofilm Lifecycle and Persister Formation. Biofilms develop through a structured lifecycle that creates protective niches for persister cells, particularly in deep layers where nutrient and oxygen gradients induce dormancy.

Molecular Mechanisms of Persister Formation and Maintenance

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Regulation

Persister formation within biofilms is regulated by sophisticated molecular mechanisms that respond to environmental stresses and population dynamics. These mechanisms can be stochastic (arising spontaneously in a subset of cells) or triggered in response to environmental cues such as nutrient limitation, antibiotic exposure, or oxidative stress [26] [1].

Figure 2: Molecular Pathways Governing Persister Formation in Biofilms. Multiple interconnected signaling pathways respond to environmental stresses by inducing cellular changes that lead to the dormant, antibiotic-tolerant persister state.

The toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules represent a fundamental persistence mechanism, consisting of stable toxin proteins that inhibit essential cellular processes and unstable antitoxins that neutralize them [26]. Under stress conditions, antitoxins are degraded, freeing toxins to induce dormancy by targeting processes like DNA replication, protein translation, and cell wall synthesis [26]. The hipA toxin in Escherichia coli phosphorylates glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, inhibiting translation and leading to growth arrest, while the E. coli hokB toxin forms pores in the membrane, causing depolarization and ATP leakage that promotes persistence [32].

The stringent response, mediated by the alarmone (p)ppGpp, serves as a global regulator of bacterial persistence [32]. Under nutrient starvation, (p)ppGpp accumulates and reprograms cellular metabolism by downregulating ribosomal RNA and protein synthesis while upregulating stress response genes [32]. This response promotes dormancy and activates TA modules, creating a multi-layered defense mechanism. In P. aeruginosa, (p)ppGpp works with the GTPase Obg to activate transcription of the hokB toxin, linking nutrient sensing directly to persistence pathways [32].

Quorum sensing (QS) represents a population-density coordination system that significantly influences persister formation in biofilms [26] [33]. Bacteria release and detect signaling molecules called autoinducers that accumulate as cell density increases. At critical thresholds, these signals trigger collective behavioral changes, including enhanced biofilm formation and persistence mechanisms [29]. In P. aeruginosa, the LasI/LasR and RhlI/RhlR systems using N-acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) regulate pyocyanin production and biofilm maturation, while Staphylococcus aureus uses the Agr system with autoinducing peptides to control virulence and persistence [29]. QS inhibition has been shown to reduce persister formation, demonstrating its critical role in population-wide tolerance [34].

Metabolic Heterogeneity and Dormancy

The physiological heterogeneity within biofilms creates a spectrum of metabolic states, from actively growing to deeply dormant cells, which is fundamental to antibiotic tolerance [26] [28]. This metabolic stratification occurs along nutrient and oxygen gradients, with cells in the biofilm interior experiencing limited nutrient availability and hypoxia [26]. These conditions trigger metabolic reprogramming that reduces cellular activity, decreasing the efficacy of antibiotics that target active processes like cell wall synthesis, DNA replication, and protein translation [26] [1].

Energy metabolism plays a crucial role in persister formation, with fluctuations in Krebs cycle enzymes and ATP levels driving phenotypic variation [32]. Reduced intracellular ATP correlates with increased persistence, as many antibiotics require active cellular processes and energy-dependent uptake for efficacy [26]. Additionally, the accumulation of protein aggregates due to ATP depletion has been linked to deeper dormancy states, with the molecular chaperones DnaK and ClpB required for disaggregation and resuscitation [32].

Table 2: Experimental Evidence for Biofilm-Enhanced Persister Formation Across Bacterial Species

| Bacterial Species | Experimental Findings | Biofilm vs. Planktonic Persister Ratio | Key Identified Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Biofilms contain up to 1% persisters after antibiotic treatment | 10-1000× higher in biofilm | TA modules, (p)ppGpp signaling, reduced metabolic activity, efflux pumps [26] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | MRSA biofilms show high tolerance to vancomycin and rifampicin | ~100× higher in biofilm | Multiple biofilm archetypes, fibrin shield, protein/eDNA matrix [28] |

| Escherichia coli | Stationary-phase biofilms exhibit increased multidrug tolerance | 10-100× higher in biofilm | hipBA TA module, SOS response, oxidative stress protection [1] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Pyrazinamide specifically targets dormant persisters in granulomas | N/A (caseous lesions) | Acidic environment activates pyrazinoic acid production disrupting membrane energetics [1] [34] |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Strong biofilm formers show correlation with carbapenem resistance | Significant correlation (p<0.05) | EPS matrix barrier, enzymatic degradation of antibiotics [30] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying Biofilm Persisters

Standardized Protocols for Persister Isolation and Quantification

Research on biofilm persisters requires specialized methodologies that account for the structural and physiological complexity of these communities. The microtiter plate biofilm formation assay represents a fundamental approach for quantifying biofilm formation capability and isolating persisters [30]. In this protocol, bacteria are grown in 96-well plates under static conditions for 24-48 hours to allow biofilm development on the well walls. Following incubation, non-adherent cells are removed by gentle washing, and biofilms are treated with high concentrations of bactericidal antibiotics (e.g., 10-100× MIC) for 3-24 hours [30]. The surviving persister population is then quantified by disrupting the biofilm through sonication or scraping, followed by serial dilution and plating on nutrient agar for colony-forming unit enumeration [26] [30].

The chemostat model with continuous flow provides a more dynamic system for studying biofilm development and persister formation under controlled nutrient conditions [28]. This approach allows researchers to simulate the natural gradients that occur in biofilms while maintaining constant growth parameters. For more sophisticated spatial analysis, the Calgary Biofilm Device (MBEC assay) enables high-throughput testing of multiple antimicrobial conditions against biofilms grown on pegs [28]. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) with fluorescent viability stains (e.g., SYTO9/propidium iodide) provides direct visualization of the three-dimensional distribution of live, dead, and persister cells within the biofilm architecture, revealing localized niches where persisters accumulate [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biofilm Persister Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilm Growth Systems | 96-well microtiter plates, Calgary Biofilm Device (MBEC), flow cells | Standardized platforms for reproducible biofilm cultivation under static or dynamic conditions | Flow cells best mimic natural environments; microtiter plates allow high-throughput screening [30] [28] |

| Viability Stains | SYTO9/propidium iodide (LIVE/DEAD), CTC (5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride) | Differentiation of live, dead, and metabolically active cells in biofilms | LIVE/DEAD staining combined with CLSM enables 3D spatial mapping of persister niches [31] |

| Matrix Disruption Agents | DNase I, dispersin B, proteinase K, glycoside hydrolases | Enzymatic breakdown of specific EPS components to study matrix protection mechanisms | Used to investigate matrix contribution to antibiotic tolerance and persister survival [28] |

| Stress Inducers | Carbon starvation media, hydrogen peroxide, acidified media, sub-MIC antibiotics | Controlled induction of persistence pathways to study regulatory mechanisms | Enable synchronized persister formation for mechanistic studies [1] [34] |

| Specialized Antimicrobials | Pyrazinamide, ADEP4, colistin, membrane-targeting compounds | Agents with demonstrated activity against persister cells and dormant populations | Used as positive controls and to study persister killing mechanisms [34] |

Emerging Control Strategies and Therapeutic Approaches

The unique biology of biofilm-protected persisters necessitates innovative treatment approaches beyond conventional antibiotics. These strategies can be broadly categorized into those targeting persister cells directly and those preventing persister formation or reactivating dormant cells to sensitize them to traditional antibiotics.

Direct killing approaches focus on growth-independent cellular targets, particularly the cell membrane. Membrane-targeting agents like 2D-24, XF-70, XF-73, and SA-558 disrupt membrane integrity, causing depolarization, ATP leakage, and ultimately cell lysis independent of metabolic state [34]. Similarly, the anti-tuberculosis drug pyrazinamide (PZA) specifically targets dormant M. tuberculosis persisters by disrupting membrane energetics when activated to pyrazinoic acid in acidic environments [1] [34]. ADEP4 activates the ClpP protease, causing uncontrolled protein degradation in dormant cells, while silver nanoparticle-shelled nanodroplets (C-AgND) interact with negatively charged EPS components to reach and kill persisters within biofilms [34].

Indirect strategies aim to prevent persister formation or reactivate dormant cells. Quorum sensing inhibitors like benzamide-benzimidazole compounds and brominated furanones disrupt cell-to-cell communication, reducing persister formation without affecting growth [34]. Inhibitors of hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) biogenesis and nitric oxide (NO) donors act as metabolic disruptors that prevent entry into dormancy [34]. Membrane-potentiating compounds such as MB6, CD437, and polymyxin B nonapeptide increase membrane permeability, enhancing uptake of conventional antibiotics like gentamicin to achieve synergistic killing of persisters [34].

Novel delivery systems including red blood cell membrane-coated nanoparticles (Hb-Naf@RBCM NPs) and engineered phages show promise for targeted delivery of antimicrobials to biofilm environments, overcoming penetration barriers [34]. Combination therapies that integrate multiple approaches—such as matrix-degrading enzymes to enhance antibiotic penetration with membrane-active compounds to increase susceptibility—represent the most promising direction for eradicating biofilm-associated persister cells [32] [34].

The sanctuary provided by biofilms for persister cells represents a critical frontier in combating chronic and recurrent bacterial infections. The structural protection of the EPS matrix combined with metabolic heterogeneity creates specialized niches where dormant, antibiotic-tolerant subpopulations can evade treatment and reseed infections. While significant progress has been made in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying persistence, including TA modules, (p)ppGpp signaling, and quorum sensing, the redundancy of these pathways presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Future research should prioritize the development of standardized models that better recapitulate the complexity of in vivo biofilms, including multispecies communities and host-pathogen interactions. The integration of advanced techniques such as single-cell RNA sequencing with spatial mapping within biofilms will provide unprecedented resolution of persister heterogeneity and metabolic states. From a therapeutic perspective, combination approaches that simultaneously target structural biofilm components, persistence pathways, and reactivate dormant cells hold the greatest promise for overcoming the recalcitrance of biofilm-associated infections. As our understanding of the intricate relationship between biofilm structures and persistence mechanisms deepens, so too will our ability to develop effective strategies against these resilient bacterial sanctuaries.

Advanced Tools and Models: Deciphering Persistence from Single Cells to Host Environments

The study of bacterial persister cells—dormant, phenotypic variants that survive antibiotic treatment—is fundamentally a challenge of analyzing cellular heterogeneity. Traditional bulk-cell analysis methods mask the rare, transient events that lead to persistence, making single-cell technologies indispensable for this field. The convergence of microfluidic technologies for high-throughput, controlled single-cell manipulation and live-cell imaging for dynamic, real-time phenotypic observation is revolutionizing our understanding of persister formation mechanisms across bacterial species. This guide objectively compares the performance, capabilities, and experimental requirements of these pivotal technologies, providing researchers with the data needed to select the optimal approach for their investigations into bacterial persistence.

Technology Performance Comparison

Microfluidic Platforms for Single-Cell Analysis

Microfluidic systems create a customized microenvironment for precise cell manipulation with spatio-temporal control, making them powerful tools for isolating and studying rare bacterial persisters. [35] [36] These platforms leverage channels with dimensions of tens to hundreds of micrometers, comparable to cellular scales, enabling high-throughput spatial segregation of single cells. [37] [38]

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Cell Isolation Technologies for Persister Studies

| Technology | Throughput | Efficiency | Cell Viability | Key Advantage for Persistence Research | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limiting Dilution | Medium | Low (~37% max) | High [37] | Simplicity, low cost [37] | Statistical randomness, low throughput [37] |

| Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) | Low | High | Low (often requires fixation) [37] | In-situ isolation from complex samples [37] | Low throughput, compromises cell integrity [37] |

| Micromanipulation | Low | High | High [37] | Targeted isolation of specific cells [37] | Manual process limits throughput [37] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | High (up to 70,000 cells/sec) [37] | Medium | Low (shear force, laser damage) [37] | Rapid screening of fluorescently labeled cells [35] | Bulky, expensive, cannot process low cell counts [37] [35] |

| Microfluidic Platforms | High (thousands of cells) | Variable by design | High (gentle isolation) [37] | Precise microenvironment control, high-throughput temporal monitoring [35] [36] | Complex fabrication, requires specialized equipment [35] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Microfluidic Modalities for Single-Cell Analysis

| Microfluidic Type | Throughput | Temporal Resolution | Integration with Live Imaging | Best Application in Persistence Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microchamber/Chip-based | Medium-High | Minutes to hours | Excellent [37] | Long-term tracking of persister formation and resuscitation |

| Droplet-based | Very High (thousands) | Seconds to minutes | Moderate [38] | High-throughput screening of rare persister cells in populations |

| Active Microfluidics | Medium | High (real-time) | Excellent [35] | Dynamic response to antibiotic pulses at single-cell level |

Live-Cell Imaging Modalities for Dynamic Single-Cell Analysis

Live-cell imaging provides the essential temporal dimension to persister studies, enabling direct observation of phenotypic transitions that precede persistence formation.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Live-Cell Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Penetration Depth | Sensitivity | Temporal Resolution | Advantages for Persistence Studies | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Imaging | Poor [39] | 10⁻⁹-10⁻¹² mol/L [39] | Seconds-minutes [39] | No substrate required; wide range of fluorescent proteins [39] | Phototoxicity, photobleaching, autofluorescence [39] |

| Bioluminescence Imaging | Fair [39] | 10⁻¹⁵-10⁻¹⁷ mol/L [39] | Minutes [39] | High sensitivity, low background, no phototoxicity [39] | Requires substrate, lower spatial resolution [39] |

| Phase-Contrast/ Brightfield | Good (in vitro) | N/A | Seconds | Label-free, minimal cellular perturbation | Limited molecular specificity |

Experimental Protocols for Single-Cell Persistence Studies

Integrated Microfluidics with Live-Cell Imaging for Persister Formation Analysis

Objective: To track the formation and resuscitation of bacterial persister cells at single-cell resolution under controlled antibiotic exposure.

Protocol Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

Bacterial Strain Preparation:

- Engineer reporter strains with fluorescent protein expression under constitutive promoters (e.g., GFP, mCherry) or stress-responsive promoters (e.g., SOS response). For bioluminescence imaging, introduce luciferase genes (Fluc, Rluc, Gluc). [39]

- Culture bacteria to specific growth phases (exponential vs. stationary), as persistence frequency varies significantly. [1] [14]

Microfluidic Device Operation:

- For microchamber chips: Use hydrodynamic cell trapping or single-cell printing to gently isolate individual bacteria into microchambers. [37] Continuous media flow maintains nutrient supply and enables precise antibiotic introduction.

- For droplet microfluidics: Encapsulate single cells in picoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets. This creates isolated bioreactors enabling high-throughput parallel analysis while eliminating cross-contamination. [38]

- For active microfluidics: Utilize optical tweezers, dielectrophoresis, or acoustic waves to position and manipulate individual cells for long-term observation. [35]

Antibiotic Treatment and Imaging:

- Introduce bactericidal antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides) at clinically relevant concentrations via precisely controlled flow rates.

- Perform time-lapse imaging using automated microscopy systems. For fluorescence, capture images at intervals (e.g., every 10-30 minutes) to minimize photodamage. For bioluminescence, longer exposures may be necessary due to lower signal intensity. [39]

- Continue imaging for 24-72 hours to capture both killing and resuscitation phases.

Data Extraction and Analysis:

- Use single-cell tracking software to quantify key parameters: time to persistence formation, resuscitation kinetics, and morphological changes.

- Calculate persistence frequency as the percentage of cells surviving antibiotic treatment after 24-48 hours that subsequently resume growth.

- Correlate persistence events with pre-existing cellular features (e.g., growth rate, expression level of stress response reporters).

High-Throughput scRNA-seq of Bacterial Persisters

Objective: To identify transcriptional heterogeneity underlying persister formation using single-cell RNA sequencing.

Protocol Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

Persister Enrichment:

- Treat bacterial cultures with high concentrations of bactericidal antibiotics (e.g., 10-100× MIC of ampicillin or ofloxacin) for 3-5 hours. [14]

- Wash cells to remove antibiotics and collect surviving persister cells. Include appropriate controls (untreated cells).

Single-Cell Isolation and Library Preparation:

- Use commercial droplet microfluidics platforms (10× Chromium or BD Rhapsody) to partition individual cells into nanoliter droplets with barcoded beads. [38] [40]

- Perform cell lysis within droplets, capturing mRNA on barcoded beads.

- Reverse transcribe RNA to create cDNA libraries with cell-specific barcodes.

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Sequence libraries using high-throughput sequencing platforms (Illumina).

- Process data through established pipelines (Cell Ranger, Seurat) for quality control, normalization, and clustering.

- Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., SC3, PhenoGraph) to identify distinct transcriptional states. [41]

- Perform differential expression analysis to identify genes upregulated in persister subpopulations (e.g., toxin-antitoxin modules, stress response genes, metabolic regulators). [14]

Key Signaling Pathways in Bacterial Persistence

Bacterial persistence is regulated by interconnected molecular pathways that control metabolic dormancy and stress adaptation. Single-cell analysis has been instrumental in revealing heterogeneity in the activation of these pathways within isogenic populations.

Pathway Dynamics at Single-Cell Level:

Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems: Single-cell studies reveal bistable expression of TA modules (e.g., HipBA, MazEF), where stochastic toxin activation in a subset of cells induces dormancy. [14] Type II TA systems are most abundant, with toxins targeting essential cellular processes like translation and DNA replication. [14]

Stringent Response: Nutrient limitation triggers ppGpp accumulation, which reprograms cellular metabolism toward dormancy. Microfluidic studies show heterogeneous ppGpp levels within populations, correlating with persistence probability. [14]

SOS Response: Antibiotic-induced DNA damage activates the RecA-LexA pathway. Live-cell imaging of SOS reporters demonstrates variable induction timing and intensity among individual cells, influencing survival outcomes. [39] [14]

Biofilm Association: Bacterial persisters are highly enriched in biofilms, where extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) provide physical protection and create nutrient gradients that induce dormancy. [1] [2] Microfluidic biofilm models enable real-time observation of spatial organization and heterogeneity in metabolic activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Persistence Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Elastomeric polymer for microfluidic device fabrication; transparent, gas-permeable, biocompatible [37] [36] | Long-term bacterial culture on-chip; observation of persister resuscitation [37] |

| Fluorescent Reporter Plasmids | Visualize gene expression and protein localization in live cells (e.g., GFP, mCherry, tdTomato) [39] | SOS response reporters (recA::gfp); promoter activity of persistence genes (hipA::mCherry) [39] |

| Bioluminescence Reporter Systems | Monitor gene expression with high sensitivity and low background (e.g., Fluc, Rluc, Gluc) [39] | Stress response studies in deep tissue models; low-abundance gene expression in persisters [39] |

| Barcoded Beads (10× Chromium, BD Rhapsody) | Capture mRNA from single cells for sequencing; unique molecular identifiers | High-throughput scRNA-seq of persister subpopulations; transcriptional heterogeneity analysis [38] [40] |