Correcting AFM Artifacts in Heterogeneous Biofilm Samples: A Guide for Reliable Nanoscale Analysis

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provides unparalleled nanoscale resolution for studying biofilm structure, mechanics, and function.

Correcting AFM Artifacts in Heterogeneous Biofilm Samples: A Guide for Reliable Nanoscale Analysis

Abstract

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provides unparalleled nanoscale resolution for studying biofilm structure, mechanics, and function. However, the inherent heterogeneity and soft, complex nature of biofilms introduce significant artifacts that can compromise data integrity. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to identify, correct, and prevent common AFM artifacts in biofilm research. Covering foundational principles, advanced methodological corrections, practical troubleshooting, and validation strategies, it synthesizes current best practices with emerging AI-driven solutions. The goal is to empower scientists to obtain more reliable, reproducible data, thereby accelerating the development of effective biofilm-control strategies in biomedical and clinical contexts.

Understanding AFM Artifacts: Why Heterogeneous Biofilms Pose Unique Imaging Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common categories of AFM artifacts and their primary causes? AFM artifacts can be systematically categorized based on their origin. The primary sources are the probe tip, the piezoelectric scanner, the image processing steps, and the experimental process itself [1]. The table below summarizes these categories and their key characteristics for identification.

Table: Common AFM Artifact Categories and Identification

| Artifact Category | Common Causes | Key Visual Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Probe Artifacts [1] | Chipped tip, contaminated tip (e.g., sample debris), worn-out tip. | Repeated double features ("seeing double"), all features appear triangular or identical in size and shape, smearing of features [1]. |

| Scanner Artifacts [1] | Hysteresis, creep, non-linear piezoelectric response, poor calibration. | Image distortion, especially at the edges of the scan range; curved background; features appearing stretched or compressed [1]. |

| Image Processing Artifacts [1] | Over-aggressive line leveling, excessive filtering. | Bands across the image, unnatural smoothing, loss of fine detail, "noise nodules" from Fourier filtering [1]. |

| Process Artifacts [1] | Incorrect scanning parameters (speed, setpoint), sample contamination, external vibrations. | Features that appear or change when scanning direction is reversed, low-frequency waves, misshapen features, unusually high or low noise [1]. |

Q2: My AFM images of heterogeneous biofilms show "double" features. What is the likely cause and solution? The appearance of double or overlapping features is a classic symptom of a probe artifact, specifically a contaminated or damaged tip [1]. A contaminated tip can act as a "double tip," where both the primary tip and a piece of debris contact the sample, producing a ghost image superimposed on the real topography. To resolve this:

- Verify the artifact: Change the scan angle by 90 degrees. If the double features rotate with the scan direction, it confirms a tip issue.

- Clean the tip: Use an approved method (e.g., UV light, plasma cleaning) to remove contaminants.

- Replace the tip: If cleaning fails, the tip may be permanently damaged and must be replaced with a new, clean one [1].

Q3: I observe repeating wavy patterns in my images. Are these real sample features? Repeating, periodic waves in the background of an image are often process artifacts, not real topography. A common cause is optical interference from the AFM's laser beam [2]. This occurs when the laser reflected from the cantilever interferes with the beam reflected from the sample surface. To minimize this:

- Ensure the laser is correctly aligned and centered on the cantilever.

- Use an AFM system with a concentrated superluminescent diode (SLD) beam, which is designed to minimize such interference fringes [2].

- Check for external sources of vibration and acoustic noise.

Q4: How can I be sure my MFM signal from a biofilm is magnetic and not distorted by electrostatic forces? In Magnetic Force Microscopy (MFM), the long-range signal is a superposition of both magnetic and electrostatic forces, which can distort results [2]. This is critical for heterogeneous biofilms, which may have varying surface potentials. To isolate the true magnetic signal:

- Use a combined Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy-Magnetic Force Microscopy (KPFM-MFM) technique [2].

- This method performs real-time compensation of electrostatic interactions by applying a nullifying DC bias voltage during the second pass, leaving an artifact-free magnetic signal [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Optimizing Scanning Parameters

Optimizing scan parameters is the first line of defense against operator-induced process artifacts. The following workflow provides a systematic approach to tuning your AFM for the best image quality on delicate biofilm samples.

Table: Key AFM Scanning Parameters and Adjustment Guidelines

| Parameter | Function | Effect of Increasing | Recommended Adjustment for Biofilms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setpoint [1] | Defines tip-sample interaction force. | Less force, probe farther from sample. Reduces noise but may lose detail. | Start with a higher setpoint to avoid sample damage, then decrease slightly to improve detail. |

| Gain [1] | Determines control loop sensitivity. | Faster response to topography, but amplifies noise. | Increase until the system becomes unstable (chatters), then slightly decrease. |

| Scan Speed [1] | How quickly the probe rasters. | Faster scanning reduces time, but can cause smearing and loss of detail. | Use slower scan speeds for high-resolution images of soft, complex biofilm structures [1]. |

| Resolution [1] | Number of pixels in the image. | Higher resolution reveals more detail but drastically increases acquisition time. | Use a resolution (e.g., 512x512 or 1024x1024) that balances detail with acceptable scan time to minimize drift. |

Advanced Protocol: Isolating Magnetic Signals with KPFM-MFM

For researchers investigating the magnetic properties of biofilms-mineral interactions, standard MFM can be misleading. The following protocol details a method to correct for electrostatic artifacts.

Objective: To obtain an artifact-free magnetic force microscopy (MFM) signal from a heterogeneous sample by compensating for electrostatic interactions in real-time using Sideband KPFM [2].

Materials and Reagents: Table: Research Reagent Solutions for KPFM-MFM

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Non-Magnetic Sample Holder | Prevents magnetic signal interference from the holder itself [2]. |

| Cobalt Alloy Coated Tip (e.g., PPP-MFMR) | Provides sensitivity to both magnetic and electrostatic forces [2]. |

| AFM with Multiple Lock-in Amplifiers | Essential for simultaneous topography, KPFM, and MFM signal detection (e.g., Park FX40) [2]. |

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Mount the sample on a non-magnetic holder to exclude external magnetic interference [2].

- First Pass (Topography):

- Engage the tip in non-contact mode.

- Use the first lock-in amplifier exclusively for topography feedback to record the true surface profile [2].

- Second Pass (KPFM-MFM):

- Lift the tip to a constant height (e.g., 50-500 nm) above the previously recorded topography.

- Simultaneously perform the following:

- Sideband KPFM: Apply an AC voltage (ωAC) to the tip. Use the second and third lock-in amplifiers to detect the sidebands (ωAC+ω₀ and ωAC-ω₀) and calculate the contact potential difference (CPD). Apply a nullifying DC bias (VDC) to cancel the electrostatic force [2].

- MFM: Use the amplitude or phase shift from the first lock-in amplifier to detect the magnetic force, which is now isolated after electrostatic compensation [2].

The logical relationship and signal flow of this advanced technique are illustrated below.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a powerful tool for studying biofilms, providing high-resolution topographical images and quantitative maps of nanomechanical properties under physiological conditions without extensive sample preparation [3]. However, the inherent complexity of biofilms—characterized by their heterogeneous structure, the presence of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and varied cellular morphology—makes them particularly susceptible to imaging artifacts. These artifacts can distort data and lead to incorrect interpretations of biofilm architecture and properties. This guide provides researchers with practical troubleshooting advice to identify, mitigate, and correct common AFM artifacts in biofilm research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Common AFM Artifacts

FAQ: What are the most frequent AFM artifacts when imaging biofilms, and how can I fix them?

Q1: My biofilm images show strange, repeating patterns or features that look duplicated. What is the cause? This is a classic tip artifact [4] [5]. It occurs when the AFM tip is damaged, contaminated with debris from the biofilm, or is a "double tip" [5]. A contaminated or blunt tip will produce images where features appear larger than they are, trenches seem smaller, and irregular shapes repeat across the scan [4].

- Solution: Replace the AFM probe with a new, clean one. To minimize contamination, ensure your sample preparation protocols minimize loosely adhered material [4]. For biofilms, using conical tips instead of pyramidal ones can also help reduce artifact issues [4].

Q2: I am seeing repetitive horizontal lines across my entire image. What could be causing this? This is typically caused by electrical noise or laser interference [4].

- Solution:

- For Electrical Noise (50 Hz): This is often governed by the building's electrical circuits. You can try imaging during quieter periods (e.g., early mornings or late evenings) when electrical noise is reduced [4].

- For Laser Interference: This happens with reflective samples; laser light reflects off the sample and interferes with the signal. Using a probe with a reflective coating (e.g., gold or aluminium) on the cantilever can eliminate this problem [4].

Q3: I see streaks or oscillations in my images, especially on rough areas of the biofilm. Why? This is often due to environmental noise/vibration or surface contamination [4] [5]. Biofilms are often imaged in liquid, and vibrations from doors, traffic, or people can easily disrupt the scan. Furthermore, loose EPS or cells on the surface can be pushed by the tip, creating streaks.

- Solution: Ensure the AFM's anti-vibration table is functioning. Place a "STOP AFM in Progress" sign to alert others. Image during quiet hours or relocate the instrument to a quieter room [4]. For contamination, refine sample preparation to remove unattached cells and debris gently but thoroughly [3] [4].

Q4: My image is distorted, with features that seem stretched or skewed. This is likely caused by sample drift or a piezo scanner artifact known as piezo creep [5]. Sample drift can occur if the biofilm is not securely fixed. Piezo creep is an inherent property of the piezoelectric scanner material.

- Solution: Allow sufficient time for the AFM and sample to thermally equilibrate after loading. For scanner artifacts, most modern AFM software includes algorithms to correct for these distortions. Ensure your system's calibration is up to date.

Quantitative Data on Bacterial Adhesion Forces

AFM can quantify interaction forces at the nanoscale, which is crucial for understanding initial biofilm attachment. The table below summarizes typical adhesion forces measured on a single bacterium, highlighting how forces vary at different locations due to EPS accumulation.

Table 1: Quantified Adhesion Forces in Bacterial Systems Measured by AFM

| Measurement Location | Adhesion Force Range (nN) | Probable Cause |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Tip vs. Bacterial Cell Surface | -3.9 to -4.3 nN | Direct tip-cell surface interaction [6] |

| Periphery of Cell-Substratum Contact | -5.1 to -5.9 nN | Accumulation of EPS at the attachment point [6] |

| Cell-Cell Interface | -6.5 to -6.8 nN | Significant EPS bridging between adjacent cells [6] |

Advanced Method: Large-Area AFM and Machine Learning

A major challenge in biofilm research is the scale mismatch between AFM's small imaging area (typically <100 µm) and the millimeter-scale heterogeneity of biofilms [3]. An advanced solution is an automated large-area AFM approach, which captures high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: A Petri dish containing PFOTS-treated glass coverslips is inoculated with the bacterial strain (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343). At selected time points, a coverslip is removed, gently rinsed to remove unattached cells, and dried before imaging [3].

- Automated Scanning: The AFM is programmed to automatically collect multiple adjacent high-resolution images across a large area of the sample.

- Image Stitching: Machine learning (ML) algorithms stitch the individual images together into a seamless, high-resolution mosaic with minimal overlap for speed [3].

- Data Analysis: ML-based image segmentation and analysis tools automatically extract quantitative parameters such as cell count, confluency, cell shape, and orientation from the large-area dataset [3].

This methodology overcomes the limitation of small scan areas and provides a comprehensive view of spatial heterogeneity, revealing patterns like a honeycomb structure of surface-attached cells that were previously obscured [3].

Visual Guide to Troubleshooting AFM Artifacts in Biofilm Research

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for diagnosing and resolving the most common AFM artifacts encountered when imaging biofilms.

Diagram 1: AFM Artifact Troubleshooting Guide

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for AFM Biofilm Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for AFM Biofilm Experiments

| Item | Function in AFM Biofilm Research | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-treated Glass | Creates a hydrophobic surface to study specific bacterial attachment dynamics and early biofilm formation [3]. | Used to examine the organization of Pantoea sp. YR343, revealing a preferred cellular orientation [3]. |

| Freshly Cleaved Mica | Provides an atomically flat, clean substrate for depositing and immobilizing bacterial cells or particles for high-resolution imaging [6]. | Used as a substrate for imaging sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) to quantify adhesion forces [6]. |

| High Aspect Ratio (HAR) Conical Probes | Superior for accurately resolving steep-edged features and deep trenches in heterogeneous biofilm structures, minimizing tip-convolution artifacts [4]. | Recommended over pyramidal tips for imaging high aspect ratio features common in biofilms [4]. |

| Reflectively Coated Cantilevers | Metal coatings (e.g., gold, aluminium) prevent laser interference artifacts, which are common when scanning reflective surfaces or in liquid [4]. | Coating prevents interference from laser light reflecting off the sample or through a semi-transparent cantilever [4]. |

| Modified Postgate's Medium C | A specific growth medium used for cultivating sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) isolated from environments like marine sediments [6]. | Used to culture SRB for AFM studies on adhesion and biofilm formation on mica surfaces [6]. |

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provides high-resolution, three-dimensional topographical images of biofilms, which are complex microbial communities critical in medical, industrial, and environmental contexts. Unlike electron microscopy, AFM can image samples under physiological conditions with minimal preparation, enabling researchers to visualize native biofilm structures, including extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), flagella, and individual microbial cells. However, when imaging heterogeneous biofilm samples, several artifacts can compromise data accuracy. These include distortions from tip convolution, image deformation from scanner drift, and measurement errors from adhesion forces. Understanding, identifying, and correcting these artifacts is essential for obtaining reliable, high-quality data in biofilm research and drug development applications. This guide provides troubleshooting protocols to address these common challenges.

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

FAQ: Common AFM Artifacts and Solutions

Q1: Why do my biofilm images show repeated, irregular patterns or features that look duplicated? A: This is typically a tip artifact. A contaminated or broken probe tip interacts with the sample surface in a way that distorts the true topography. With a blunt tip, structures appear larger, and trenches appear smaller. This can obscure critical biofilm features like the width of bacterial flagella or the shape of pores in the EPS matrix [4].

- Solution: Replace the AFM probe with a new, sharp one. For consistent high-resolution imaging of biofilms, use probes with a high aspect ratio and a sharp apex. Ensure proper sample preparation to minimize loose debris that could contaminate the tip [4].

Q2: Why are my AFM images of a bacterial cluster distorted or stretched in one direction? A: This is characteristic of sample drift. The sample moves slowly in one direction during the scan, often due to thermal expansion as the instrument settles. This is particularly problematic in high-resolution techniques like AFM and makes it difficult to accurately measure cellular dimensions and distances between cells in a biofilm [7].

- Solution: Allow the system sufficient time to equilibrate thermally after loading the sample. Turn off external heat sources (e.g., lights) and ensure the sample is securely fixed. Scanning quickly can also help reduce the visible effects of drift [7].

Q3: Why am I having difficulty accurately imaging deep trenches or vertical structures in my multilayer biofilm? A: This is often due to the geometry of the AFM probe. Pyramidal or tetrahedral tips have side-walls that can make physical contact with steep-edged features before the tip apex reaches the bottom of a trench. Furthermore, low aspect ratio probes cannot physically reach into deep and narrow pores within the biofilm structure [4].

- Solution: Switch to a probe with a conical shape and a high aspect ratio (HAR). Conical tips trace steep edges more accurately, and HAR probes are specifically designed to resolve high, non-planar features common in complex biofilms [4].

Q4: Why do I see repetitive lines or streaks across my image? A: This is usually caused by external interference.

- Electrical noise from building circuits or other instruments appears as periodic lines at 50/60 Hz. You can identify it by comparing the noise frequency to your scan rate [4].

- Laser interference occurs when light reflects off a highly reflective sample or the cantilever itself, creating interfering signals at the photodetector [4].

- Environmental vibrations from doors, people, or traffic can also cause streaking [4].

- Solution: For electrical noise, try imaging during quieter periods (e.g., early morning). Use a probe with a reflective coating to minimize laser interference. Ensure the anti-vibration table is functional and place the AFM in a quiet location, using signs to alert others of sensitive work in progress [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Step-by-Step Protocols

Protocol 1: Correcting for Tip Convolution Artifacts

Tip convolution is a fundamental artifact where the finite size and shape of the AFM tip physically interacts with the sample, causing steep features to appear broader and shallower than they are. This is critical when imaging nanoscale features like flagella (~20-50 nm in height) [3] or pore spaces in the EPS.

- Step 1: Identify the Artifact. Look for features that seem unusually broadened or repeated across the image. Fine details may be lost or appear with unrealistic symmetry.

- Step 2: Characterize the Tip Geometry.

- Method A (Blind Estimation): Use a software algorithm (e.g., in Gwyddion) with your image data from a sample with sharp features to estimate the actual tip shape [8].

- Method B (Modeling): If the tip is new and clean, use the manufacturer's specifications (apex radius, slope) to create a tip model in your analysis software [8].

- Step 3: Reconstruct the Surface.

- Use a surface reconstruction (erosion) algorithm in your analysis software. This process mathematically "erodes" the scanned image with the known tip shape to produce a closer approximation of the true surface [8].

- Step 4: Generate a Certainty Map.

- After reconstruction, create a certainty map. This highlights areas of the image where the tip did not make single-point contact with the surface and where data is irreversibly lost, helping you assess the reliability of the corrected image [8].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Tip Convolution on Biofilm Features

| Biofilm Feature | Actual Size (approx.) | Apparent Size with Blunt Tip | Correction Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Flagella | 20-50 nm height [3] | Broader, may not be resolved | Tip reconstruction, sharper probes |

| EPS Fibrils | 10-100 nm diameter | Appear thicker | Tip reconstruction, certainty mapping |

| Pores in EPS Matrix | Variable, can be <100 nm | Appear narrower and shallower | Use of high-aspect-ratio probes [4] |

| Single Bacterial Cell | ~2 µm length, ~1 µm diam. [3] | Dimensions slightly enlarged | Surface reconstruction algorithm [8] |

Protocol 2: Mitigating Sample Drift in Long-Duration Biofilm Scans

Sample drift is a major concern for time-lapse studies of biofilm growth or for large-area scans that take a long time, as it distorts spatial relationships.

- Step 1: Recognition. Drift is confirmed when the same cluster of cells appears distorted and different when the slow scan direction is changed [7].

- Step 2: System Stabilization.

- Thermal Equilibrium: Load the sample and allow the AFM stage to sit for at least 30-60 minutes before starting a high-resolution or long-duration scan. This allows thermal equilibration to minimize drift from expansion/contraction.

- Secure Mounting: Ensure the biofilm substrate (e.g., a glass coverslip or pyrite coupon [9]) is firmly fixed to the sample stage using a reliable adhesive or clip.

- Environmental Control: Turn off nearby heat sources and maintain a stable room temperature.

- Step 3: Scanning Parameter Adjustment.

- Increase the scan speed to "outrun" the drift, though this must be balanced against maintaining image quality and minimizing tip forces. For large-area automated AFM, software with automated drift compensation may be available [3].

Table 2: Common Artifacts and Their Impact on Biofilm Analysis

| Artifact Type | Effect on Biofilm Image | Impact on Quantitative Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Tip Convolution | Loss of fine detail, broadening of nanofeatures, inaccurate trench profiles | Inaccurate measurement of flagellar diameter, EPS fiber size, and surface porosity [8] |

| Sample Drift | Stretching or compression of features in one direction, distorted cell clusters | Incorrect calculation of cell-to-cell distances, cluster size, and spatial distribution [7] |

| Adhesion Forces | Sudden jumps in height data, "ghost" features, difficulty maintaining setpoint | Inaccurate nanomechanical property mapping (e.g., adhesion, stiffness) [4] |

| Electrical Noise | Repetitive horizontal lines across the image | Reduced signal-to-noise ratio, obscuring subtle topographical changes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AFM Biofilm Experiments

| Item | Function in Biofilm AFM | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Aspect-Ratio (HAR) Probes | To accurately resolve deep trenches and vertical structures in 3D biofilm architectures. | Conical silicon or silicon nitride tips; superior to pyramidal tips for non-planar features [4]. |

| Sharp Probes (High Resolution) | For imaging nanoscale features like flagella, pili, and EPS fibers. | Probes with a low tip radius (<10 nm) are essential for high-resolution scans [3] [4]. |

| Chemically Functionalized Probes | To measure specific adhesion forces between the tip and biofilm components. | Tips coated with specific molecules (e.g., lectins for polysaccharide binding) can map interaction forces. |

| Opaque & Reflective Substrates | For combined AFM-Epifluorescence microscopy on non-transparent materials. | Pyrite coupons for bioleaching studies [9]; reflective coatings can reduce laser interference [4]. |

| Surface Treatment Reagents | To study the effect of surface properties on bacterial adhesion and biofilm assembly. | PFOTS-treated glass to create hydrophobic surfaces [3]. |

| Fluorescent Stains (e.g., DAPI) | For correlative microscopy; allows identification of cellular features in AFM topographs. | Stains bacterial DNA, enabling cell identification on opaque surfaces when combined with EFM [9]. |

Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

Detailed Methodology: Combined AFM and Epifluorescence Microscopy (EFM) for Biofilms on Opaque Surfaces

This protocol, adapted from a study on Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans biofilms on pyrite, is ideal for correlating topographic data with cell identity on opaque substrates common in biocorrosion and bioleaching research [9].

Sample Preparation:

- Substratum: Cut coupons (e.g., 10x10x1 mm) from an opaque material of interest (e.g., pyrite, metal alloy). Clean thoroughly (e.g., with HCl and acetone for pyrite) to remove contaminants [9].

- Biofilm Growth: Incubate sterile coupons in a bacterial suspension for the desired attachment and biofilm formation period (e.g., 4 days at 28°C) [9].

- Staining: After incubation, stain the biofilm with a fluorescent dye (e.g., 0.01% DAPI for 10 minutes) to label cellular components. The sample can be either kept hydrated or air-dried [9].

Instrumentation and Shuttling:

- Use a shuttle stage system that allows precise transfer of the sample between a separate AFM and an upright epifluorescence microscope.

- Fix the stained and dried sample to a glass slide and mount it on the shuttle stage.

Correlative Imaging:

- EFM Imaging: First, locate an area of interest and capture a fluorescence image using the EFM to identify the positions of bacterial cells.

- AFM Imaging: Transfer the shuttle stage to the AFM. Navigate to the exact same location (with an error of ~3-5 µm) using the predefined coordinates. Acquire high-resolution topographical images in air or liquid. Note that contact mode in liquid may deform or detach cells, while imaging in air is often more stable [9].

Data Correlation: Overlay the EFM and AFM images to correlate cell identity (from fluorescence) with high-resolution topography and mechanical properties (from AFM).

Combined AFM-EFM Workflow

Advanced Methods: Large-Area AFM and Machine Learning

Traditional AFM is limited to scan areas typically below 100x100 µm, making it difficult to link cellular-scale events to the larger functional architecture of biofilms [3]. Recent advancements have begun to overcome this limitation.

Automated Large-Area AFM with Machine Learning: A novel approach involves automating the AFM to capture and stitch together multiple high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas [3]. This process is aided by machine learning (ML) for several key tasks:

- Image Stitching: Seamlessly combines adjacent image tiles, even with minimal overlapping features.

- Cell Detection and Classification: Automatically identifies and categorizes individual cells within the vast dataset, extracting parameters like cell count, confluency, shape, and orientation [3].

- Application: This method has revealed a preferred cellular orientation and a distinctive honeycomb pattern in early-stage biofilms of Pantoea sp. YR343, features previously obscured by the limited field of view [3].

Resolving Scale Mismatch with AFM

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a powerful tool for characterizing the structural and mechanical properties of heterogeneous biofilms at the nanoscale. However, the inherent complexity of biofilms—with their varied cellular morphologies, extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and intricate surface topography—makes them particularly susceptible to imaging and measurement artifacts. These artifacts can significantly skew topographical data and nanomechanical properties, leading to erroneous biological interpretations. This technical support guide provides a systematic framework for identifying, troubleshooting, and correcting common AFM artifacts within the context of biofilm research, ensuring data integrity for critical applications in drug development and microbial science.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My biofilm images show repeated, "ghosted" features or irregular shapes that do not align with expected cellular structures. What is the cause and how can I fix it?

- Problem: Unexpected patterns in images, such as duplicated features or irregular shapes repeating across the scan [4].

- Primary Cause: Tip artifacts caused by a contaminated, damaged, or blunt AFM probe [4] [5]. A dirty or broken tip interacts with the sample in an unpredictable way, creating features that are not real.

- Solutions:

- Replace the Probe: The most straightforward solution is to use a new, sharp probe [4].

- Verify Probe Quality: Ensure you are using a probe appropriate for your sample. Contaminated probes can often be cleaned, but replacement is more reliable.

- Sample Preparation: Minimize loosely adhered material on your sample surface to reduce the chance of contamination transfer to the tip [4].

- Problem: Inaccurate profiling of vertical structures and deep trenches [4] [10].

- Primary Cause: Tip convolution effects [10] [5]. This occurs when the geometry and finite size of the AFM tip prevent it from reaching the bottom of narrow features, leading to a distorted image where features appear wider and trenches appear narrower [4].

- Solutions:

- Use High-Aspect-Ratio (HAR) Probes: HAR probes are designed to penetrate deep, narrow features more effectively, providing a more accurate topographic profile [4].

- Use Conical Tips: For features with high vertical relief, conical tips are superior to standard pyramidal or tetrahedral tips as they provide better access to steep-edged structures [4].

- Tip Deconvolution: Apply post-processing algorithms to mathematically correct for the known geometry of the tip [10].

FAQ 3: Repetitive horizontal lines or streaking appear across my images, obscuring the true biofilm topography.

- Problem: Repetitive lines or streaks in the fast-scan direction [4] [1].

- Primary Causes and Solutions:

- Electrical Noise: This often manifests as 50/60 Hz interference. To fix it, try changing the scan rate or identify times of day with lower electrical load on the building's circuits [4].

- Laser Interference: If the sample is highly reflective, laser light reflecting off the sample surface can interfere with the signal. Use a probe with a reflective coating on the cantilever to mitigate this [4].

- Environmental Vibration: Noise from building vibrations, doors, or traffic can cause streaking. Ensure the anti-vibration table is functional and consider imaging during quieter periods or relocating the instrument to a basement lab [4].

- Scanning Too Fast: If the scan speed is too high, the feedback loop cannot track the surface accurately, causing streaks. Reduce the scan rate to improve image quality [1].

FAQ 4: The measured Young's modulus of individual collagen fibrils or other nanofibers in my biofilm matrix shows an unacceptably wide range of values. What are the potential sources of error?

- Problem: High variability and inaccuracy in nanomechanical measurements of fibrous structures [10].

- Primary Causes:

- Invalid Elastic Half-Space Assumption: The standard Hertzian contact models used for calculating Young's modulus assume the sample is an infinitely thick, flat, elastic half-space. This assumption is invalid for nanofibers, where the radius is comparable to the tip radius [10].

- Tip Convolution in Radius Measurement: The accurate determination of the fibril's radius is critical for mechanics models. Tip convolution effects lead to an overestimation of the fibril's width, which directly propagates into an error in the calculated Young's modulus [10].

- Incorrect Contact Model: Using a model for a perfect conical or pyramidal indenter when the actual tip shape is different or poorly characterized introduces significant error [10].

- Solutions:

- Apply Correction Factors: Use adjusted equations from Hertzian mechanics that incorporate "correction factors" for the finite dimensions of the nanofiber [10].

- Accurate Tip Characterization: Precisely determine the shape and dimensions of the AFM tip through calibration samples to correctly model the contact area [10].

- Validate Radius Measurement: Use techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to independently verify the nanofiber radius, avoiding errors from AFM tip convolution [10].

The following tables summarize the common artifacts, their impact on quantitative data, and the corresponding solutions for biofilm research.

Table 1: Impact of Common Artifacts on Topographical and Mechanical Data

| Artifact Type | Effect on Topography | Effect on Nanomechanics | Common in Biofilm Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tip Convolution [10] | - Overestimation of feature width [10]- Underestimation of trench depth [4] | - Invalidates mechanical models [10]- Incorrect contact area calculation [10] | Bacterial cells [3], EPS fibrils [10], pore networks |

| Contaminated Tip [4] [5] | - "Double-tip" ghost images [5]- Strange, non-reproducible shapes [4] | - Unreliable force-distance curves- Spurious adhesion & stiffness values | All surfaces, especially with loose EPS [4] |

| Blunt Tip [4] | - Loss of high-resolution details- Features appear smeared and larger | - Overestimation of modulus (larger contact area)- Poor spatial resolution in property mapping | Flagella [3], surface proteins [3], fine EPS structures |

| Electrical/Environmental Noise [4] [1] | - Repetitive stripes/streaks in image- Increased background noise | - Noisy force spectroscopy data- Reduced accuracy in fitting models | All measurements, particularly high-resolution scans |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for AFM Biofilm Characterization

| Essential Material / Reagent | Function and Application | Considerations for Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Aspect-Ratio (HAR) Probes [4] | Provides accurate topography of deep, narrow features like EPS pores and bacterial cell junctions. | Superior for resolving the complex 3D architecture of heterogeneous biofilms. |

| Conical Tips [4] | Improves profiling of features with steep edges, such as bacterial clusters and biofilm aggregates. | Reduces tip convolution artifacts on complex biofilm surfaces. |

| Reflective Coated Cantilevers [4] | (e.g., Gold, Aluminum) Minimizes laser interference artifacts on reflective substrates. | Essential for imaging biofilms on abiotic surfaces like medical implants or silicon wafers. |

| PFOTS-treated Glass Surfaces [3] | Creates a defined hydrophobic surface to study initial bacterial attachment and biofilm assembly. | Useful for standardizing adhesion studies across experiments. |

Experimental Protocol: An Integrated Workflow for Artifact Correction in Biofilm AFM

This detailed protocol outlines a systematic approach for acquiring and verifying artifact-free AFM data from biofilm samples, integrating both operational and computational steps.

Step 1: Pre-Imaging Preparation and Probe Selection

- Sample Preparation: Gently rinse the biofilm to remove unattached cells and culture medium, but avoid dehydration if measuring under physiological conditions [3]. For biofilm studies on abiotic surfaces, treatments like PFOTS can standardize surface properties [3].

- Probe Selection: Choose a probe based on the biofilm's key features.

- For high-resolution imaging of flagella or fine EPS, use sharp tips (nominal radius < 10 nm) [3].

- For mapping the topography of complex, clustered biofilms, use High-Aspect-Ratio (HAR) or conical tips to minimize convolution [4] [10].

- For nanomechanical mapping, select a tip with a well-defined geometry (e.g., spherical colloidal probes) and a spring constant appropriate for the expected stiffness of the biofilm.

Step 2: Initial Setup and In-Run Optimization

- Scanner Calibration: Use a calibration grating with known dimensions to verify the accuracy of the scanner in X, Y, and Z axes. This corrects for scanner artifacts like hysteresis and creep [1].

- Laser Alignment: Carefully align the laser on the cantilever to prevent interference patterns caused by reflections from the sample surface [4] [1].

- Parameter Tuning:

- Start by increasing the gain to improve the feedback response [1].

- Then, decrease the setpoint to increase the tip-sample interaction for better tracking, but ensure the force is low enough to avoid sample damage [1].

- Use a slow scan speed to allow the tip to accurately track the heterogeneous and soft biofilm surface. Increase speed only if the image quality remains high [1].

Step 3: Post-Processing and Data Validation

- Tip Deconvolution: If the tip shape is well-characterized, apply deconvolution algorithms to the topographical data to correct for broadening effects, providing a more accurate representation of feature dimensions [10].

- Model Selection for Nanomechanics: For mechanical data on fibrous structures (e.g., collagen in EPS), do not use standard Hertz models. Apply corrected models that account for the cylindrical geometry of the fibril and the relative dimensions of the tip and sample [10].

- Data Cross-Validation: Correlate AFM data with other imaging modalities. For instance, use Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) to validate the overall biofilm architecture or SEM to verify the dimensions of specific features [3] [11].

Workflow Diagram: An AI-Enhanced Framework for Artifact Management

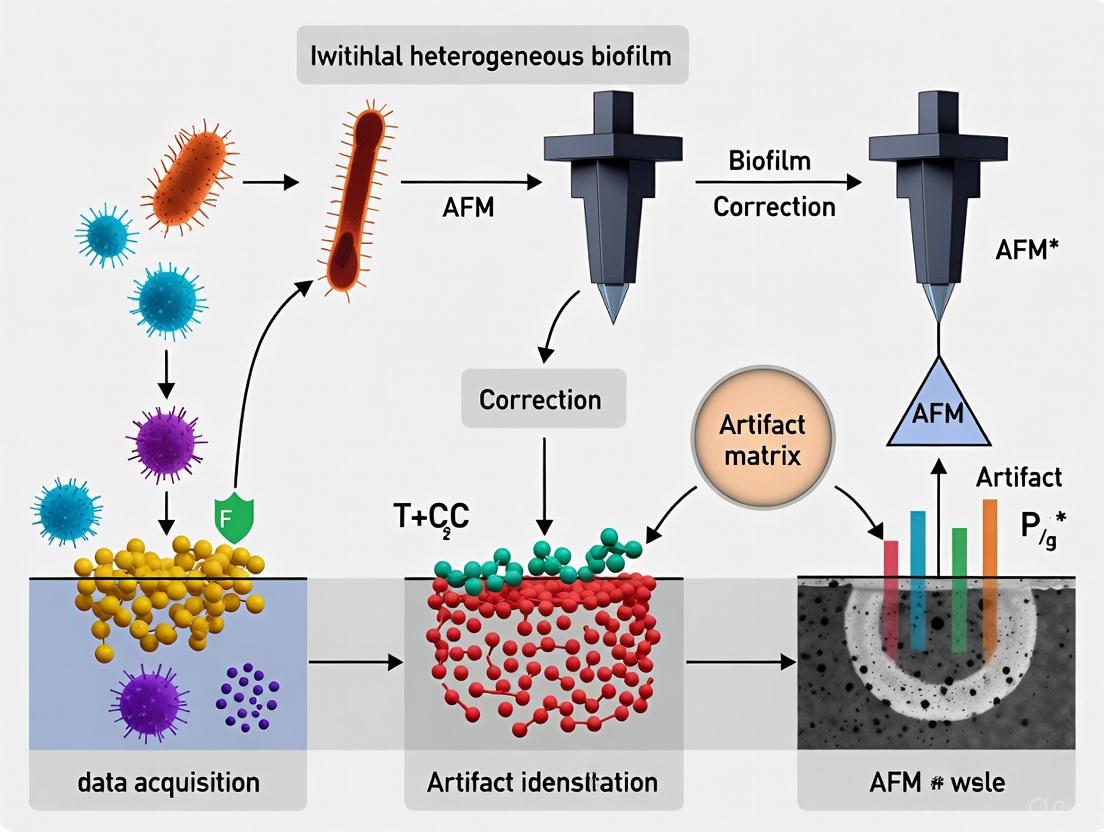

The following diagram illustrates a modern, integrated workflow that combines traditional AFM best practices with machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) approaches to proactively manage artifacts in biofilm research, as highlighted in recent literature [3] [11].

Diagram Title: Integrated AFM Workflow for Biofilm Artifact Management

This workflow highlights how traditional practices are augmented by AI. For example, automated large-area AFM combined with machine learning-based stitching allows for the creation of high-resolution millimeter-scale maps, revealing biofilm patterns like honeycomb structures previously obscured by small scan areas [3]. Furthermore, AI-powered segmentation can automatically detect cells, classify features, and identify regions likely affected by artifacts, guiding the researcher to areas requiring re-scanning or specific correction protocols [3] [11]. This integrated approach significantly enhances the throughput, reliability, and depth of AFM analysis in complex biofilm systems.

Advanced AFM Methodologies and Protocols for Artifact Minimization in Biofilms

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) generates nanoscale topographical and mechanical data by physically scanning a sharp probe across a sample surface. In the context of heterogeneous biofilm research, an inappropriate probe choice is a primary source of imaging artifacts and inaccurate nanomechanical data. Biofilms present a unique challenge due to their complex architecture, combining soft, adhesive extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) with intricate, high-aspect-ratio features like pores, channels, and cellular aggregates [12] [13]. This technical guide outlines evidence-based procedures for selecting optimal AFM probes to accurately characterize biofilm systems, thereby correcting common artifacts and ensuring data fidelity for researchers and drug development professionals.

Key Probe Parameters and Their Impact on Biofilm Imaging

The AFM probe is a complex tool whose components significantly influence data quality on heterogeneous soft materials [14] [13]. The following parameters are most critical for biofilm characterization.

Critical Probe Selection Parameters

- Force Constant: This defines the stiffness of the probe cantilever. For soft, adhesive samples like biofilms, a probe with a low to moderate force constant (typically 0.1 N/m to 5 N/m) is recommended [14]. A stiffer probe can damage soft samples, while a more flexible cantilever is sensitive enough to track the surface without excessive force. If the biofilm is particularly sticky, a slightly stiffer probe (e.g., towards the higher end of this range) can help the cantilever break away from adhesive interactions during oscillatory modes like tapping mode [14].

- Resonant Frequency: In dynamic (tapping) modes, the probe is oscillated near its resonant frequency. A higher resonant frequency (generally >300 kHz) is desirable because it allows the probe's tapping frequency to be far from the lower scanning frequency. This separation makes it easier to isolate the sample's topographical response and reduces the chance of feedback instability and associated artifacts [14].

- Tip Radius: The sharpness of the tip dictates the best achievable lateral resolution. A sharp tip radius (<10 nm) is necessary to resolve fine features such as individual flagella (which can be 20-50 nm in height) or pores within the EPS matrix [12] [14]. A tip radius larger than the feature of interest will result in broadening or complete obscuration of that feature.

- Tip Aspect Ratio and Shape: For biofilms with deep crevices or high-aspect-ratio features, a high-aspect-ratio tip (tall and skinny) is essential. Standard pyramidal tips cannot probe deep into indentations, leading to "shadowing" or "widening" artifacts. Specialized tip geometries (e.g., needle-like) are designed for this purpose [14].

- Tip Coating: Tips with hard, durable coatings (e.g., diamond-like carbon) can prolong probe lifetime when scanning rough or abrasive samples. However, coatings can increase the tip radius, so a balance must be struck between longevity and ultimate resolution [14].

Table 1: AFM Probe Parameter Guide for Biofilm Characterization

| Parameter | Recommendation for Biofilms | Rationale | Risk of Incorrect Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Constant | 0.1 - 5 N/m | Provides sufficient sensitivity for soft samples while overcoming adhesion. | Too stiff: sample damage; Too soft: poor tracking, stickiness |

| Resonant Frequency | >300 kHz | Isolates tapping frequency from scan frequency, improving stability. | Low frequency: increased artifacts, slower scan speeds |

| Tip Radius | <10 nm | Enables resolution of fine features (e.g., flagella, EPS fibers). | Large radius: poor resolution, feature broadening |

| Tip Aspect Ratio | High | Allows probing into deep, narrow surface features. | Low aspect ratio: shadowing, inaccurate depth measurement |

| Q Factor | High (for rectangular levers) | Increases sensitivity to small force variations. | Low Q: reduced signal-to-noise ratio |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Probe-Related Artifacts and Solutions

This section addresses specific issues users might encounter during AFM experiments on biofilm samples.

FAQ 1: My images of a bacterial cluster show a "double-tip" or "ghost" artifact. What is the cause and how can I fix it?

- Problem: A "double-tip" artifact, where features appear to be duplicated, indicates a damaged or contaminated probe tip.

- Solution:

- Inspect the tip: Use a high-resolution optical microscope or SEM if available to confirm tip integrity.

- Clean the sample and tip: Ensure your biofilm sample is free of loose debris. In some cases, tip cleaning procedures can remove contaminants.

- Replace the probe: If the tip is physically broken, replacement is the only solution. Handle probes with care using an ESD bracelet to prevent electrostatic discharge damage [14].

FAQ 2: When scanning a heterogeneous biofilm, my probe appears to "get stuck" in soft areas, distorting the image.

- Problem: This is a classic sign of excessive adhesion forces between the probe and the soft, adhesive biofilm matrix.

- Solution:

- Increase the cantilever stiffness: Switch to a probe with a higher force constant (e.g., 2-5 N/m) to provide enough restoring force to pull away from the sticky surface [14].

- Optimize scanning parameters: Reduce the scan size and/or increase the scan rate to spend less time in contact with the adhesive area.

- Use dynamic mode: If using a contact mode, switch to a dynamic (tapping) mode, which minimizes lateral forces and adhesion effects [13].

FAQ 3: I cannot resolve the fine, web-like structures (like flagella) between cells that I know are present.

- Problem: This is a resolution limitation, typically caused by a tip that is too blunt or has an inappropriate shape.

- Solution:

- Use a sharper tip: Select a probe with a guaranteed tip radius of <5 nm.

- Select a high-aspect-ratio tip: For features that extend from the surface, a tall, sharp tip is necessary to accurately trace them without convolution from the tip shank [14].

- Verify with a reference sample: Image a known sample with sharp features (e.g., a grating) to confirm your probe's effective sharpness.

FAQ 4: My force spectroscopy data on a biofilm shows an artificially high modulus near the cell-EPS boundary. Why?

- Problem: This is likely a substrate effect or convolution artifact. The probe's interaction volume includes both the soft EPS and the stiffer underlying cell or substrate, convoluting the measurement [15] [13].

- Solution:

- Use a colloidal probe: A spherical tip provides a well-defined contact geometry that is easier to model and less sensitive to sharp transitions.

- Apply advanced contact mechanics: Use models that account for multi-layer systems or finite sample thickness.

- Shallow indentation: Use very low indentation depths relative to the feature size to locally probe the soft material, though this requires high sensitivity [13].

Experimental Protocol: Correlating Probe Selection with Biofilm Feature Analysis

The following methodology, adapted from recent high-impact research, provides a workflow for selecting and applying AFM probes to characterize key features in a Pantoea sp. biofilm.

Title: Protocol for High-Resolution Topographical and Nanomechanical Mapping of Early-Stage Biofilms

Background: This protocol is designed to capture the spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology during the early stages of biofilm formation, which includes imaging delicate extracellular structures and measuring local mechanical properties [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Biofilm Sample: Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilm grown on PFOTS-treated glass coverslips for ~30 minutes to 8 hours [12].

- Imaging Buffer: Appropriate liquid growth medium to maintain physiological conditions.

- AFM Probes: See "Research Reagent Solutions" below.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Gently rinse the coverslip with buffer to remove unattached cells. If using liquid imaging, mount the sample in the fluid cell.

- Probe Selection: Based on the target feature, select the appropriate probe (see Table 2).

- AFM Calibration: Precisely calibrate the AFM's photodetector, cantilever sensitivity, and spring constant using a standardized method (e.g., thermal tune) on a clean, rigid surface (e.g., silicon wafer) [15].

- Coarse Approach: Carefully engage the probe onto the sample surface in a region with low feature density.

- Topographical Imaging: a. For large-area scans (millimeter-scale) to locate regions of interest, use a standard silicon nitride probe (e.g., SCANASYST-AIR) in tapping mode. b. For high-resolution imaging of cellular arrangements and flagella, switch to a sharp, high-resonant-frequency probe (e.g., RTESPA-300). Use tapping mode in liquid to minimize forces [12].

- Nanomechanical Mapping: a. Switch to a colloidal probe (e.g., CP-PNPL-BSG) for quantitative force mapping. b. Perform force-volume mapping or a high-speed spectral mode across the area of interest, ensuring indentation is limited to 10-15% of the sample thickness to minimize substrate effects [15] [13].

- Data Analysis: Use machine learning-based segmentation or standard analysis software (e.g., AFMech Suite) to stitch large-area images, detect cells, classify features, and extract mechanical properties from force curves [12] [15].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions - Essential AFM Probes for Biofilm Research

| Probe Type / Model | Key Specifications | Primary Function in Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sharp Tapping Mode Probe | High resonant frequency (>300 kHz), low force constant (~5 N/m), tip radius <10 nm | High-resolution imaging of bacterial cell walls, flagella, pili, and fine EPS fibers [12] [14]. |

| Colloidal Probe | Spherical tip (radius 0.5-5 µm), moderate force constant (~0.1 N/m) | Quantitative nanomechanical mapping (modulus, adhesion); minimizes indentation damage and simplifies contact mechanics on soft, adhesive EPS [15] [13]. |

| High-Aspect-Ratio Probe | Tip height >10 µm, tip radius <10 nm | Probing deep into pores, channels, and crevices within the biofilm 3D structure without artifact generation [14]. |

| Soft Static Lever | Very low force constant (0.01 - 0.5 N/m) | High-sensitivity force spectroscopy on extremely soft regions to measure weak adhesion forces and map ultralow elastic moduli [13]. |

Probe Selection Workflow Diagram

The following diagram visualizes the decision-making process for selecting the optimal AFM probe based on your experimental goal.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a powerful tool for studying the intricate architecture and mechanical properties of live biofilms at the nanoscale. However, the heterogeneous and viscoelastic nature of biofilms presents unique challenges, often leading to imaging artifacts that can distort biological interpretation. This technical support guide provides a focused comparison of the primary AFM imaging modes—Contact, Tapping, and PeakForce Tapping—for researchers aiming to minimize artifacts and obtain reliable data from live biofilm experiments.

AFM Imaging Modes: A Comparative Guide

The choice of AFM imaging mode is critical for successful live biofilm analysis. The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each mode.

Table 1: Comparison of AFM Imaging Modes for Live Biofilms

| Feature | Contact Mode | Tapping Mode | PeakForce Tapping Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Tip is in constant contact with the sample surface [16]. | Cantilever oscillates, tip intermittently contacts ("taps") the surface [16] [17]. | Controlled, periodic "tapping" where the tip engages the surface at a precise, low force [18]. |

| Tip-Sample Interaction | High; constant physical contact generates significant lateral (frictional) forces [16]. | Low; vertical oscillation minimizes lateral forces, reducing sample damage [16] [17]. | Very Low; direct control of the peak interaction force for each tap, virtually eliminating lateral forces [18]. |

| Typical Forces | 1-100 nN [16] | Lower than Contact Mode; controlled by amplitude damping. | Precisely controlled, typically at the pico- to nano-newton scale. |

| Optimal Cantilever Stiffness | Low (C ≤ 1 N/m) [16] | High (C ~ 40 N/m) [16] | Medium to High; optimized for force control. |

| Best For (Sample Type) | Hard, flat, and robust surfaces [16]. | Soft, adhesive, and loosely bound samples; excellent for heterogeneous biofilms [17]. | Very soft, delicate, and highly heterogeneous samples; ideal for live cells and hydrated biofilm matrices [18]. |

| Key Advantages | - Simple operation [16]- Enables certain electrical modes (C-AFM, TUNA) [16]- Measures lateral friction forces. | - Reduces sample damage and deformation [16] [17]- Suitable for rough and adhesive surfaces [16]- Enables Phase Imaging for material contrast [16] [17]. | - Superior force control for minimal sample disturbance [18]- Directly and quantitatively maps nanomechanical properties (e.g., adhesion, modulus) simultaneously with topography [18]. |

| Common Artifacts & Challenges | - Streaks, sample deformation, or complete removal of soft biofilm features [17]- High tip and sample wear [16]. | - Instability on very soft or adhesive regions if parameters are not optimized.- Phase images can be difficult to interpret quantitatively. | - Requires careful tuning of the peak force setpoint to balance image quality and sample protection. |

Diagram 1: A workflow for selecting the optimal AFM imaging mode for biofilm samples.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My Tapping Mode images of a live biofilm appear blurry and unstable. The cantilever oscillation often dies out completely. What could be the cause?

- Problem: This is a classic symptom of high adhesion between the AFM tip and the hydrated, sticky EPS matrix of the biofilm. The excessive adhesive forces dampen the cantilever's oscillation amplitude beyond the feedback loop's ability to recover.

- Solution:

- Verify Cantilever: Ensure you are using a stiff cantilever (e.g., ~40 N/m) as recommended for Tapping Mode to overcome adhesion [16].

- Optimize Setpoint: Gradually increase the amplitude setpoint to reduce the tip-sample interaction time and force. Be cautious not to set it too high, which can lead to loss of contact and noisy images.

- Consider PeakForce Tapping: Switch to PeakForce Tapping Mode, which is specifically designed to handle highly adhesive samples by directly controlling and limiting the maximum force applied during each tap, preventing the tip from getting stuck [18].

Q2: I am using Contact Mode, and my scans are consistently streaking in the fast-scan direction. Furthermore, the biofilm structure appears to be "smeared." What is happening?

- Problem: This indicates excessive lateral (shear) forces are deforming or even removing the soft biofilm material during scanning. The tip is physically dragging the biofilm components across the surface.

- Solution:

- Reduce Applied Force: Immediately lower the deflection setpoint to minimize the normal force, which in turn reduces lateral forces.

- Switch to a Dynamic Mode: Contact Mode is generally unsuitable for delicate biofilms. The definitive solution is to switch to a dynamic mode like Tapping Mode or PeakForce Tapping, which minimize lateral forces by using vertical oscillations [16] [17] [18].

- Check Immobilization: Ensure your biofilm is adequately immobilized on the substrate to withstand the minimal remaining forces from a gentler mode.

Q3: How can I quantitatively map the elasticity of a live biofilm simultaneously with its topography?

- Answer: PeakForce Tapping Mode is the ideal choice for this application. In this mode, a force-distance curve is captured at every pixel of the image. The system can fit these curves to mechanical models (e.g., Hertz model) to generate quantitative maps of elastic modulus (stiffness), adhesion, and dissipation alongside the topographical image [18]. While force spectroscopy can be performed in other modes, PeakForce Tapping integrates it directly into high-resolution imaging.

Q4: My phase image on a heterogeneous biofilm shows strong contrast, but I am unsure how to interpret it. Is the contrast related to material properties?

- Answer: Yes, phase contrast in Tapping Mode is sensitive to differences in the sample's mechanical and adhesive properties. However, it is a qualitative measure. A darker phase shift often indicates a more adhesive or dissipative (softer) region, while a brighter shift can indicate a more elastic (stiffer) region [17]. For quantitative data, you must use PeakForce Tapping-based mechanical mapping. When reporting, always note that phase imaging provides qualitative material contrast, not absolute values.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for AFM Biofilm Studies

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-treated Glass | Creates a hydrophobic surface to promote bacterial adhesion for early-stage biofilm studies [3]. | Provides a uniform, defined surface chemistry to study attachment dynamics. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Stamps | Microfabricated stamps with pores to physically trap and immobilize microbial cells for stable imaging in liquid [17]. | Crucial for preventing cells from being displaced by the scanning tip. Pore size must match the target cell diameter. |

| Poly-L-Lysine | A chemical immobilizer that creates a positively charged surface to enhance electrostatic attachment of (typically negatively charged) bacterial cells [17]. | A common and easy-to-use method, but can potentially alter surface physicochemical properties. |

| Silicon Nitride Cantilevers | The core sensing component of the AFM. Material and shape are chosen for biological compatibility and specific imaging modes [19]. | Rectangular or triangular shapes are common. Softer levers (< 1 N/m) are used for contact and force spectroscopy on soft samples, while stiffer levers (~40 N/m) are for Tapping Mode [16] [19]. |

| Spherical Tip Probes | Cantilevers with a microsphere attached to the end, used for force spectroscopy and nanoindentation [19]. | The defined geometry simplifies contact mechanics modeling for quantitative measurement of biofilm adhesion and viscoelasticity [20]. |

| Physiological Buffer (e.g., PBS) | Maintains biofilm hydration and native state during imaging in liquid. | Essential for live biofilm studies to prevent dehydration and preserve physiological function. |

Diagram 2: Key experimental workflow for AFM analysis of live biofilms, from preparation to analysis.

Leveraging Large-Area Automated AFM and Machine Learning for Seamless Stitching and Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My large-area stitched AFM image shows repetitive, unnatural patterns. What could be the cause? This is typically a tip artifact, often caused by a contaminated or broken AFM probe. A blunt or dirty tip can cause structures to appear larger than they are and fine details to be duplicated across the image [4].

- Solution:

- Replace the AFM probe: Use a new, sharp probe to see if the issue disappears [4].

- Regular inspection: Implement a protocol to regularly inspect and clean probes, especially when working with heterogeneous biofilm samples that can leave residue.

Q2: I am having difficulty accurately imaging the deep, porous structures of my biofilm. The trenches appear shallow and poorly resolved. This problem usually stems from using an AFM probe with an inappropriate shape or low aspect ratio. Standard pyramidal tips cannot reach the bottom of deep, narrow features [4].

- Solution:

- Switch to a high-aspect-ratio (HAR) conical probe: Conical tips are superior for resolving steep-edged features and deep trenches common in biofilm architecture [4].

Q3: After an automated tip approach, my image is blurry and lacks nanoscale detail, as if the tip isn't in proper contact. This indicates false feedback, where the system mistakenly believes the tip is in contact. Common causes are a thick surface contamination layer or electrostatic forces between the cantilever and sample [21].

- Solution:

- Adjust the setpoint: Increase the tip-sample interaction force. In vibrating (tapping) mode, decrease the setpoint value; in non-vibrating (contact) mode, increase it [21].

- Reduce electrostatic forces: Create a conductive path between the cantilever and sample, or use a stiffer cantilever to minimize the effect of surface charge [21].

- Improve sample preparation: Ensure protocols minimize loosely adhered material and contamination [4].

Q4: My large-area scan shows repetitive lines across the image, distorting the data. This is often due to electrical noise or laser interference [4].

- Solution:

- Identify the source: Check if the noise frequency is 50 Hz (or 60 Hz), which would indicate electrical noise from building circuits [4].

- Use reflective coatings: Employ probes with a reflective coating (e.g., gold or aluminium) to prevent laser light reflecting off the sample from interfering with the signal [4].

- Change scanning times: Image during quieter periods (e.g., early mornings) when electrical noise may be lower [4].

Q5: How can I ensure my machine learning model accurately identifies and classifies cells in a large-area AFM scan? Accuracy depends on high-quality training data and a robust model.

- Solution:

- Leverage transfer learning: Adapt a pre-trained model (like YOLOv3) for cell detection to low-quality images from an AFM stage camera, which requires limited new training data [22].

- Implement a closed-loop control: Use the ML model's output to directly control the AFM scanner trajectory, creating a feedback loop that ensures the probe navigates to the correct locations for verification and measurement [22].

Troubleshooting Guide for Common AFM Artifacts

The table below summarizes common issues, their causes, and solutions specifically for heterogeneous biofilm research.

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Tip Artifacts (e.g., duplicated features) [4] | Contaminated or broken AFM probe. | Replace with a new, sharp probe. |

| Poor Trench Resolution [4] | Low-aspect-ratio or pyramidal tip geometry. | Use a High-Aspect-Ratio (HAR) conical tip. |

| False Feedback (blurry images) [21] | Tip trapped in contamination layer or electrostatic forces. | Adjust setpoint; use stiffer lever; create conductive path. |

| Streaks & Blurred Lines [4] | Environmental vibrations or loose sample contamination. | Use anti-vibration table; ensure sample is securely prepared. |

| Repetitive Lines (Noise) [4] | Electrical noise (50/60 Hz) or laser interference. | Image during low-noise periods; use probes with reflective coating. |

Experimental Protocol: Automated Large-Area AFM for Biofilm Analysis

This protocol is adapted from the study on Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilm assembly [3].

1. Objective To capture high-resolution, millimeter-scale topographical images of early-stage biofilm formation, enabling the analysis of spatial heterogeneity, cellular orientation, and the role of appendages like flagella.

2. Materials and Reagents

- Bacterial Strain: Pantoea sp. YR343 (gram-negative, rod-shaped, motile with peritrichous flagella) and a flagella-deficient control strain [3].

- Growth Medium: Appropriate liquid growth medium [3].

- Substrate: PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or silicon substrates [3].

- Imaging Instrument: Atomic Force Microscope equipped with a large-area automated scanning stage.

3. Methodology

- Sample Preparation:

- Place PFOTS-treated glass coverslips in a petri dish.

- Inoculate the dish with Pantoea cells suspended in the liquid growth medium.

- Incubate for selected time points (e.g., 30 minutes for initial attachment; 6-8 hours for cluster formation).

- At each time point, remove a coverslip and gently rinse it with buffer to remove unattached cells.

- Air-dry the sample before AFM imaging [3].

- Automated Large-Area AFM Imaging:

- System Calibration: Ensure the AFM is properly calibrated.

- Region Selection: Define a millimeter-scale area for scanning.

- Automated Scanning: Initiate the automated routine to capture multiple high-resolution AFM images with minimal overlap across the defined area.

- Image Stitching: Use integrated machine learning algorithms to seamlessly stitch the individual images into a single, large-area map [3].

- Data Analysis:

- Cell Detection & Classification: Apply ML-based segmentation to automatically identify and classify individual cells [3].

- Morphometric Analysis: Extract quantitative parameters such as cell count, confluency, shape, and orientation from the stitched image [3].

- Appendage Mapping: Visually identify and map fine structures like flagella, noting their interactions and distribution [3].

4. Expected Results

- After ~30 minutes: Isolated rod-shaped cells (~2 µm long, ~1 µm diameter) with flagellar appendages (~20-50 nm in height) visible [3].

- After 6-8 hours: Formation of cell clusters with a distinctive honeycomb pattern and flagella bridging gaps between cells [3].

Workflow Diagram: Large-Area AFM with ML Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials used in the featured large-area AFM biofilm experiment [3].

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| PFOTS-treated Glass Coverslips | Provides a modified surface to study bacterial adhesion dynamics and the effect of surface properties on biofilm assembly. |

| Silicon Substrates | Used to create gradient-structured surfaces for combinatorial studies on how surface modifications influence bacterial attachment density. |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | A model gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium with peritrichous flagella, used to study the genetic regulation and structural organization of early-stage biofilms. |

| Flagella-deficient Mutant Strain | Serves as a control to confirm the identity of flagellar structures and their specific role in biofilm assembly beyond initial attachment. |

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) offers unparalleled capability for high-resolution, nanoscale imaging of biological samples under near-physiological conditions. For the study of heterogeneous biofilms, maintaining precise environmental control, particularly of hydration, is not merely beneficial—it is critical for preserving native structures. Traditional electron microscopy methods involve harsh chemical fixation, dehydration, and metal coating that irreversibly alter biofilm architecture [23]. In contrast, AFM enables researchers to image fully hydrated specimens, revealing authentic structural details of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), cellular morphologies, and intricate appendages like flagella that would otherwise be collapsed or distorted [3].

The challenge for researchers lies in overcoming the technical artifacts that arise when imaging these soft, dynamic, and heterogeneous materials in fluid. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guidance and FAQs to help researchers identify, understand, and correct common artifacts specific to biofilm imaging in hydrated environments, enabling more reliable data collection and interpretation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common AFM Artifacts in Hydrated Biofilm Imaging

Problem: Excessive Noise and Unstable Imaging in Fluid

- Observed Symptoms: Blurry images, high-frequency oscillations in trace/retrace mismatch, inability to maintain stable tip-sample interaction.

- Primary Causes:

- Environmental vibrations affecting the AFM system.

- Acoustic noise from the surroundings.

- Fluid cell turbulence or bubbles in the system.

- Brownian motion of loose material or the tip in liquid [24].

- Solutions:

- Verify Anti-Vibration Setup: Ensure the anti-vibration table is functioning correctly (e.g., check gas supply if applicable) [4].

- Minimize Acoustic Noise: Use an acoustic enclosure if available. Image during quieter times (e.g., early mornings) and use "STOP AFM in progress" signs to alert colleagues [4].

- Purge Fluid Cell: Carefully degas buffers before use and ensure the fluid cell is properly sealed and purged of all air bubbles.

- Optimize Imaging Parameters: Reduce scan size and speed to improve stability in challenging conditions. For highly mobile samples, a slight chemical fixation (e.g., 0.5% glutaraldehyde) may be necessary to stabilize structures for longer observations without complete denaturation [24].

Problem: Sample Drift or Movement During Scanning

- Observed Symptoms: Elongated or smeared features, images that shift between scan lines, inability to re-locate the same area.

- Primary Causes:

- Poor sample adhesion to the substrate.

- Insufficient fixation of the biofilm.

- Loose particles being pushed by the tip.

- Thermal drift from temperature fluctuations.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Substrate and Adhesion: Use freshly cleaved mica or treated glass surfaces (e.g., PFOTS-treated) to enhance cell attachment [3]. For powders or loose cells, resuspend in a clean solvent and deposit onto the substrate, followed by thorough drying to fix particles before hydrating for imaging [25].

- Secure Sample Mounting: Use a suitable adhesive to firmly secure the sample to the mounting stub.

- Allow Thermal Equilibrium: After introducing liquid into the cell, allow the system to equilibrate for at least 20-30 minutes to minimize thermal drift.

- Use Appropriate Imaging Mode: Switch from contact mode to a dynamic mode like TappingMode or PeakForce Tapping to minimize lateral forces that can displace loosely bound material [26] [4].

Problem: Loss of Resolution and Failure to Resolve Fine Structures

- Observed Symptoms: Inability to visualize expected fine details like flagella, EPS strands, or membrane proteins; images appear "soft" or blurred.

- Primary Causes:

- Blunt or contaminated AFM probe.

- Excessive imaging force compressing soft biofilm features.

- Biofilm surface too soft or viscoelastic.

- Insufficient resolution of the chosen probe.

- Solutions:

- Probe Selection: Use sharp, high-resolution probes designed for biological imaging. Conical tips are often superior to pyramidal ones for resolving fine features [4].

- Optimize Imaging Force: Carefully adjust the setpoint (in TappingMode) or PeakForce Setpoint to use the minimum possible force. A slight increase in force may sometimes clear away obscuring material to reveal underlying structures, as seen with hydrated collagen fibrils [24], but excessive force will damage the sample.

- Verify Probe Condition: Image a known, sharp test sample (e.g., a grating) to check for tip degradation or contamination. Replace the probe if artifacts are found [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it so difficult to image my unfixed, fully hydrated biofilm samples?

Hydrated biofilms are inherently soft, dynamic, and sensitive to the AFM tip's interaction forces. Unfixed specimens can begin to dissociate in buffer, becoming unstable within minutes [24]. Furthermore, turbulence and Brownian motion in liquid create significant noise [24]. A compromise is often necessary: very mild fixation (e.g., low-concentration glutaraldehyde) can stabilize the structure for the duration of the scan while preserving much of the native architecture.

Q2: What is the best AFM mode for imaging delicate biofilms in fluid without damaging them?

TappingMode (a dynamic, intermittent contact mode) and PeakForce Tapping are highly recommended. TappingMode significantly reduces lateral forces compared to contact mode, preventing sample damage and displacement [26]. PeakForce Tapping goes a step further by directly controlling and minimizing the maximum force applied to the sample at every pixel, enabling imaging with forces as low as ~10 pN, which is ideal for pristine imaging of soft biological materials [26].

Q3: My biofilm is heterogeneous over large areas, but AFM only scans small regions. How can I link cellular-scale details to the larger community structure?

This is a recognized limitation of conventional AFM. To address this, researchers are now developing automated large-area AFM approaches. These methods stitch together hundreds of high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas, aided by machine learning for seamless stitching and analysis. This provides a detailed view of spatial heterogeneity and organization previously obscured by the small scan sizes of traditional AFM [3].

Q4: How can I be sure that the filamentous structures I'm seeing are bacterial flagella and not imaging artifacts?

Artifact identification is crucial. To confirm structures like flagella:

- Correlate with genetics: Image a flagella-deficient mutant strain under identical conditions. The absence of the filamentous structures in the mutant strongly confirms their identity as flagella [3].

- Check dimensions: Measure the height (often ~20-50 nm) and length of the appendages. True flagella will have consistent dimensions and often originate from a cell pole or are peritrichous [3].

- Assess reproducibility: Ensure the structures are visible in multiple scans, on different cells, and with different probes to rule out a tip artifact.

Experimental Protocol: Imaging Hydrated Biofilm Ultrastructure

This protocol outlines the key steps for preparing and imaging biofilm samples in fluid to preserve native ultrastructure, based on methodologies adapted from successful AFM studies of hydrated biological specimens [3] [23] [24].

Sample Preparation Workflow

Critical Parameters for Hydrated Imaging

Table 1: Key Parameters for AFM Imaging of Hydrated Biofilms

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging Mode | TappingMode or PeakForce Tapping | Minimizes lateral and normal forces, preventing sample damage and displacement [26]. |

| Scan Size | Start small (1-5 µm) before scaling up | Ensures stability and allows for optimization of parameters on a manageable area. |

| Scan Rate | 0.5 - 1.5 Hz | Balances data acquisition speed with sufficient tracking of surface topography. |

| Setpoint/Peak Force | As low as possible while maintaining engagement | Preserves soft, native structures by minimizing applied force. |

| Buffer | Appropriate physiological buffer (e.g., PBS) | Maintains biofilm viability and native structure. Always degas before use. |

| Cantilever Spring Constant | 0.1 - 0.7 N/m (soft levers) | Suitable for interacting with soft biological samples without excessive indentation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Hydrated Biofilm AFM

| Item | Function & Importance | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Freshly Cleaved Mica | An atomically flat, negatively charged substrate ideal for adsorbing cells and biomolecules. | Provides a consistent, clean surface for initial attachment studies [25]. |

| Chemically Treated Coverslips | Modified surfaces to study specific biofilm-surface interactions. | PFOTS-treated glass used to study Pantoea sp. YR343 attachment and patterning [3]. |

| High-Resolution Probes | Conical or sharpened silicon nitride probes for resolving fine details. | Essential for visualizing flagella (~20-50 nm height) and other nanoscale features [3] [4]. |

| Physiological Buffers | To maintain native conditions and hydration during imaging. | PBS, Tris, or HEPES buffers; must be degassed to prevent bubble formation in the fluid cell. |

| Mild Fixatives | To stabilize ultra-soft structures for duration of scan without full denaturation. | Low-concentration glutaraldehyde (0.5%) used to stabilize hydrated rat tail tendon [24]. |

| Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) Compound | For cryo-preservation and cryo-sectioning of tissue-supported biofilms. | Preserves native biomolecular structures in tissue sections for subsequent AFM analysis [23]. |

Protocol for Cohesive Energy and Nanomechanical Mapping to Ensure Quantitative Accuracy

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provides powerful capabilities for quantifying the nanomechanical properties and cohesive strength of biofilms, which are critical for understanding their resilience and detachment behavior. However, achieving quantitative accuracy is challenging due to the inherent heterogeneity of biofilms, the complexity of tip-sample interactions, and various sources of artifacts. This guide provides standardized protocols and troubleshooting for accurate measurement of biofilm cohesive energy and nanomechanical properties, focusing on the PeakForce QNM (Quantitative Nanomechanical Mapping) mode and related techniques.

Table: Key AFM Modes for Biofilm Property Quantification

| AFM Mode | Measured Properties | Primary Application | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| PeakForce QNM | Elastic Modulus, Adhesion, Dissipation, Deformation [27] | High-resolution nanomechanical mapping | Medium-High [27] |

| Force Volume | Force-distance curves at each pixel [27] | Nanomechanical mapping | Low (Slow) [27] |

| Photothermal OFF-Resonance Tapping (PORT) | Nanomechanical properties [28] | High-speed nanomechanical mapping | High [28] |

| Contact Mode Friction | Frictional energy dissipation [29] | Biofilm cohesive energy measurement | Medium |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Biofilm Cohesive Energy via AFM Abrasion

This protocol, adapted from Ahimou et al. (2007), measures the cohesive energy of a moist biofilm by quantifying the volume removed and the frictional energy dissipated during controlled scanning [29].

Materials & Reagents:

- Biofilm Sample: Grown on a suitable substrate (e.g., polyolefin membrane) [29].