Correlative AFM-Confocal Microscopy: A Multimodal Framework for Biofilm Nanomechanics and 3D Architecture

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) for advanced biofilm analysis.

Correlative AFM-Confocal Microscopy: A Multimodal Framework for Biofilm Nanomechanics and 3D Architecture

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) for advanced biofilm analysis. It covers the foundational principles of AFM nanomechanics and CLSM imaging, detailed protocols for correlated methodology, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, and a comparative validation against traditional techniques. By synthesizing insights from recent technological advancements, including automated large-area AFM and AI-driven analysis, this resource aims to empower the development of precision-guided therapeutic interventions against persistent biofilm-associated infections.

Understanding the Synergy: Core Principles of AFM Nanomechanics and Confocal Biofilm Imaging

Biofilms are sophisticated microbial communities encased in a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), playing a critical role in up to 80% of persistent human infections [1] [2]. This structural complexity confers remarkable resilience against antimicrobial agents, with biofilm-embedded bacteria demonstrating up to 1,000-fold greater resistance compared to their planktonic counterparts [1]. The extracellular matrix functions as a formidable physical barrier, limiting antibiotic penetration while creating heterogeneous microenvironments that support metabolic dormancy and persister cell formation [1]. Understanding this intricate architecture is paramount for developing effective therapeutic strategies to combat biofilm-associated infections.

Advanced imaging technologies have revealed the spatial and chemical heterogeneity of biofilms, providing crucial insights into the structure-function relationships that underpin their recalcitrance. This guide examines how the correlation of atomic force microscopy (AFM) nanomechanics with confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) structural data is transforming our understanding of biofilm resilience, enabling researchers to identify vulnerabilities and test novel intervention strategies.

Comparative Analysis of Biofilm Imaging Technologies

Technical Specifications and Capabilities

Table 1: Comparison of Key Biofilm Imaging Techniques

| Technique | Resolution | Imaging Environment | Key Measurable Parameters | Major Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | 2 nm (in-plane) [3] | Ambient air, liquid, vacuum [3] | Nanomechanical properties (Young's modulus, adhesion), 3D topography, molecular interactions [3] [4] [5] | Operates in physiological conditions; quantitative mechanical mapping; minimal sample preparation [3] [6] | Small imaging area (<100 μm) [7]; slow scanning speed; limited to surface properties [7] [3] |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) | ~200 nm [3] | Liquid, physiological conditions [8] [2] | 3D architecture, biofilm biovolume, live/dead cell distribution, spatial organization [8] [2] | Non-destructive optical sectioning; real-time monitoring of hydrated biofilms; molecular specificity with fluorescence [8] [2] | Requires fluorescent labeling; limited resolution compared to AFM; no mechanical property data [3] [2] |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | 10 nm [3] | High vacuum (conventional) [3] | Surface topology, cellular arrangement, extracellular matrix features [1] [9] | High-resolution surface imaging; large field of view [9] | Extensive sample preparation (dehydration, coating) causes artifacts [7] [9]; no living samples |

| Environmental SEM (ESEM) | 10-100 nm (varies) | Hydrated conditions possible [9] | Surface features of hydrated specimens | Direct visualization of hydrated biofilms [9] | Lower resolution than conventional SEM [9] |

Application-Based Performance

Table 2: Application Performance of AFM and CLSM in Biofilm Research

| Research Application | AFM Performance | CLSM Performance | Complementary Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural-Mechanical Correlation | Directly measures stiffness (Young's modulus) and adhesion forces of biofilm matrix [6] | Visualizes architectural features (porosity, thickness, microcolony formation) [6] | Links mechanical properties to specific structural features; identifies regional heterogeneity |

| Antimicrobial Efficacy Testing | Quantifies nanomechanical changes in response to treatment (e.g., stiffness reduction) [5] | Tracks penetration of fluorescent antimicrobials and resulting cell viability [2] | Correlates mechanical degradation with biological activity loss |

| Single-Cell Analysis | Measures mechanical properties of individual cells (e.g., cancer cells are softer than healthy cells) [5] | Resolves subcellular localization of fluorescent reporters and molecular constituents [10] | Connects cellular mechanics to functional states and phenotypic responses |

| Dynamic Process Monitoring | High-speed AFM tracks surface assembly and detachment events [3] | Time-lapse imaging captures 3D architectural development and population dynamics [8] | Reveals how mechanical and structural evolution are interconnected over time |

Experimental Protocols for Correlative AFM-Confocal Microscopy

Integrated Workflow for Structural and Mechanical Analysis

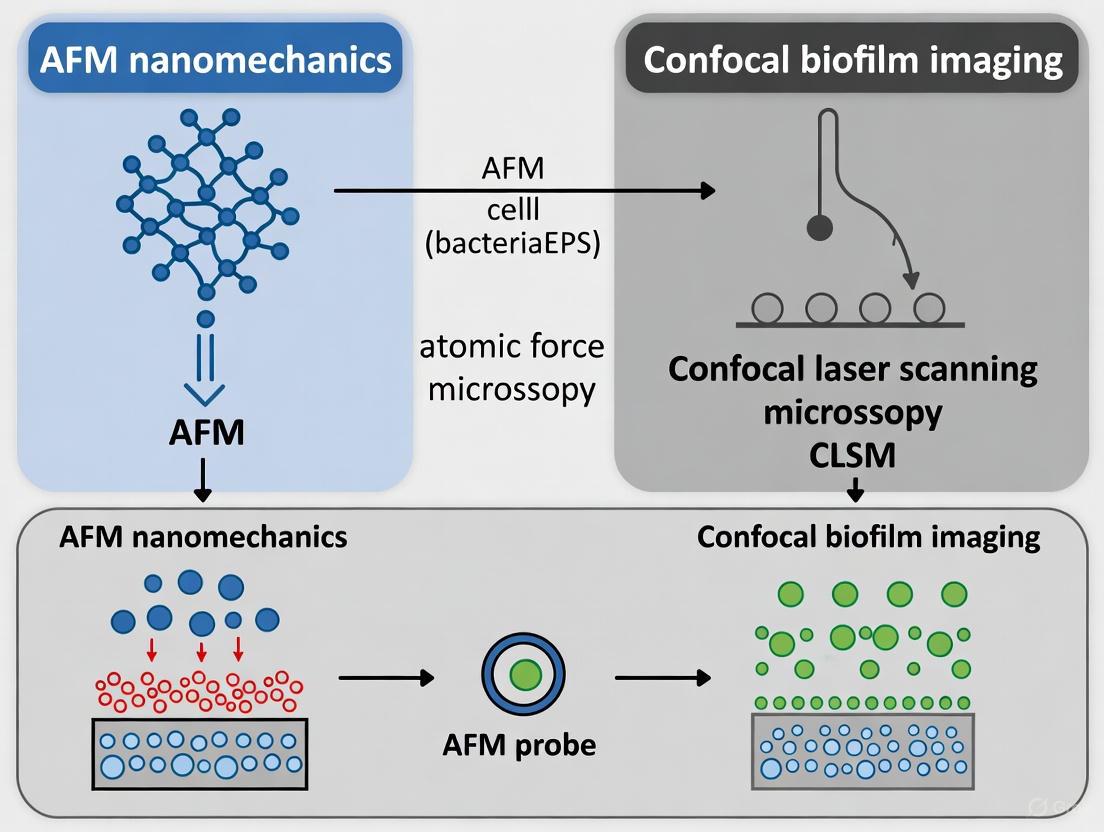

Diagram Title: Correlative AFM-Confocal Biofilm Analysis

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Sample Preparation Protocol

Biofilm Growth Conditions:

- Substrate Treatment: For bacterial adhesion studies, treat glass coverslips with PFOTS (perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) to create a hydrophobic surface that promotes biofilm formation [7].

- Inoculation and Culture: Inoculate surfaces with bacterial suspension (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343, Lactococcus lactis) in appropriate growth medium [7] [6]. For lab strains, use M17 broth with 0.5% glucose for Lactococcus lactis cultures [6].

- Incubation Parameters: Grow biofilms under static conditions at optimal growth temperature (e.g., 30°C for L. lactis, 37°C for human pathogens) for 24-48 hours to establish mature structures [6].

- Sample Stabilization: For AFM imaging in liquid, use dopamine-coated Petri dishes (4 mg/mL in PBS) to improve surface adhesion and maintain biofilm integrity during analysis [6].

Atomic Force Microscopy Protocol

Instrumentation and Calibration:

- Probe Selection: Use silicon or silicon nitride cantilevers with nominal spring constants of 0.01-0.1 N/m for soft biological samples [5] [6]. Calibrate each cantilever using thermal tuning method before measurement.

- Imaging Mode Selection: Employ force spectroscopy mode for nanomechanical mapping, collecting 2D arrays of force-distance curves (force volume technique) across the biofilm surface [5] [6].

- Measurement Parameters: Set approach/retract velocity between 0.5-2 μm/s with maximum indentation force of 0.5-2 nN to avoid sample damage while ensuring sufficient signal [6].

Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Elasticity Measurement: Apply Hertz contact mechanics model to approach force-distance curves to calculate Young's modulus [5]. For thin samples on hard substrates, use modified models (Chen, Tu, or Cappella models) [5].

- Adhesion Forces: Analyze retraction curves to quantify adhesion forces from unbinding events [5] [6]. Use Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) or Derjaguin-Müller-Toporov (DMT) models for adhesive contact mechanics [5].

- Spatial Mapping: Generate 2D elasticity and adhesion maps with corresponding topography to visualize mechanical heterogeneity [6].

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy Protocol

Staining Procedures:

- Viability Staining: Use LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kits with SYTO 9 and propidium iodide to distinguish live (green) from dead (red) cells within biofilms [2].

- Matrix Staining: Employ concanavalin A conjugated with Alexa Fluor dyes to label polysaccharide components of the EPS matrix [2].

- Specific Labeling: For engineered strains, utilize constitutive fluorescent protein expression (GFP, RFP) for species-specific identification in multi-species biofilms [8].

Imaging Parameters:

- Optical Configuration: Use 40x or 63x water-immersion objectives with numerical aperture >1.2 for optimal resolution in liquid samples [8].

- Z-stack Acquisition: Collect optical sections at 0.5-1 μm intervals through the entire biofilm thickness to reconstruct 3D architecture [8] [6].

- Multi-channel Detection: Configure separate detection channels for each fluorophore with appropriate emission filters to minimize cross-talk [8].

Image Analysis:

- Architectural Quantification: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, IMARIS) to calculate biovolume, porosity, surface area-to-volume ratio, and thickness [8] [6].

- Spatial Analysis: Implement spatial statistics to quantify clustering patterns and species distribution in multi-species biofilms [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Imaging

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Correlative AFM-Confocal Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Labels | SYTO 9/propidium iodide, Concanavalin A-Alexa Fluor, constitutive GFP/RFP [8] [2] | Visualize viability, EPS components, and specific bacterial strains | Optimize concentration to minimize staining artifacts; confirm specificity with controls |

| Surface Modifiers | PFOTS, dopamine hydrochloride [7] [6] | Promote controlled biofilm adhesion to substrates | PFOTS creates hydrophobic surfaces; dopamine enables polymerization for stable anchoring |

| Culture Media | M17 broth with glucose, Brain Heart Infusion (BHI), semi-defined biofilm-promoting medium [8] [6] | Support reproducible biofilm growth under controlled conditions | Include selective antibiotics (spectinomycin, erythromycin) for plasmid maintenance in engineered strains |

| AFM Consumables | Silicon nitride cantilevers, colloidal probes [5] [6] | Nanomechanical property measurement and single-cell force spectroscopy | Calibrate spring constants for each cantilever batch; functionalize with specific ligands for adhesion studies |

Data Interpretation: Connecting Structure to Mechanics

Case Study: Lactococcus lactis Biofilm Analysis

A seminal study demonstrates the power of correlative AFM-CLSM analysis in elucidating how surface proteins influence biofilm mechanical properties [6]. CLSM revealed that piliated L. lactis strains formed heterogeneous, aerial biofilms with complex architectures, while non-piliated isogenic strains developed compact, uniform biofilms [6]. Corresponding AFM nanomechanical mapping showed striking differences: non-piliated strains formed stiffer biofilms (Young's modulus: 4-100 kPa) compared to piliated variants (0.04-0.1 kPa) [6]. This inverse relationship between structural complexity and mechanical stiffness highlights how surface appendages enable the formation of more porous, compliant biofilms that may facilitate nutrient diffusion and resistance to mechanical disruption.

Case Study: Pantoea sp. YR343 Spatial Organization

Large-area automated AFM combined with machine learning analysis revealed previously unrecognized spatial patterns during early biofilm formation [7]. High-resolution imaging over millimeter-scale areas identified a preferred cellular orientation among surface-attached cells, forming distinctive honeycomb patterns [7]. Detailed mapping of flagella interactions demonstrated that these appendages coordinate not only initial attachment but also subsequent biofilm assembly through intercellular connections [7]. This study exemplifies how advanced AFM methodologies can uncover organizational principles across multiple scales, bridging nanoscale interactions to emergent community architecture.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Biofilm Imaging

The integration of artificial intelligence with biofilm imaging represents a paradigm shift in analysis capabilities [10]. Deep learning algorithms enable automated segmentation of complex biofilm architectures, resolution enhancement beyond optical limits, and multimodal data fusion from complementary techniques [10]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can precisely delineate biofilm boundaries in CLSM datasets, while generative adversarial networks reconstruct high-resolution structural information from lower-quality inputs [10]. These approaches facilitate high-throughput quantification of structural heterogeneity and dynamic processes that were previously intractable through manual analysis.

Large-Area AFM with Machine Learning

Traditional AFM has been limited by small imaging areas (<100 μm), restricting representativeness for heterogeneous biofilms [7]. Recent developments in automated large-area AFM address this limitation through coordinated sample positioning and automated image stitching, enabling high-resolution mapping over millimeter-scale areas [7]. When enhanced with machine learning algorithms for cell detection and classification, this approach captures spatial heterogeneity and rare architectural features that conventional methods routinely miss [7]. This technological advancement finally enables researchers to link nanoscale cellular interactions to the functional macroscale organization of biofilms.

Molecular Imaging Integration

Beyond structural and mechanical characterization, molecular imaging techniques provide complementary information about chemical composition and metabolic activity within biofilms [2]. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI), Raman spectroscopy, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) can spatially resolve the distribution of metabolites, quorum-sensing molecules, and antimicrobial compounds throughout the biofilm architecture [2]. The future of comprehensive biofilm analysis lies in multimodal correlation that simultaneously interrogates structural organization, mechanical properties, and molecular composition within the same biofilm sample.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has established itself as a dominant technique for characterizing mechanical properties at the nanoscale, transforming our understanding of material behavior in diverse fields from biology to materials science [11]. As a mechanical microscope, AFM operates by measuring the interaction force between a sharp probe and the sample surface, transducing this force into measurable cantilever deflection that can be converted back into quantitative force values [11]. This fundamental principle enables researchers to generate detailed nanomechanical maps—spatially resolved representations of mechanical parameters as a function of the tip's coordinates [11]. Unlike many other characterization techniques, AFM can perform these measurements under physiological conditions, making it particularly valuable for studying soft biological samples like living cells, bacteria, and biofilm matrices without extensive sample preparation that might alter their native properties [7] [12].

The application spectrum of AFM nanomechanical characterization is remarkably broad. In biological sciences, it has revealed that cancer cells exhibit different mechanical properties than healthy cells, opening avenues for prognostic applications [12]. In microbiology, AFM investigates how bacteria adapt to antibiotics, addressing the critical challenge of antimicrobial resistance [12]. Environmental scientists employ AFM to characterize micro- and nanoplastic particles in groundwater, analyzing their aggregation behavior and surface properties [13]. Recent technological advances have significantly enhanced AFM capabilities, with improvements in quantitative accuracy, spatial resolution, high-speed data acquisition, machine learning integration, and viscoelastic property mapping expanding the technique's utility across these diverse domains [11].

AFM Techniques for Nanomechanical Property Mapping

Classification of Nanomechanical Mapping Modes

AFM-based mechanical property measurements can be broadly categorized into two fundamental approaches: indentation and adhesion modes [11]. Indentation modes, the focus of this guide, involve applying a controlled deformation to the sample surface and analyzing the response to extract mechanical parameters. These methods can be further classified into three principal groups: force-distance curve-based methods, nanoscale rheology, and parametric methods [11]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and is suited to different sample types and research questions, with the choice of method depending on factors such as required spatial resolution, measurement speed, sample stiffness, and the specific mechanical properties of interest.

Table 1: Comparison of Major AFM Nanomechanical Mapping Techniques

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Primary Measured Parameters | Typical Acquisition Speed | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Force Volume | Records force-distance curves at each pixel by modulating tip-sample distance [11] | Elastic modulus, adhesion force, deformation [11] [12] | Slow to moderate (traditional); up to 0.4 fps with advanced actuation [11] | Heterogeneous materials, single cells, polymer blends |

| Nano-DMA (Nanoscale Rheology) | Applies oscillatory signals to tip in contact and measures viscoelastic response [11] | Storage/loss moduli, loss tangent, complex modulus [11] | Moderate to fast | Viscoelastic materials, live cell dynamics, polymers |

| Parametric Methods | Drives cantilever at resonance and monitors oscillation parameter changes [11] | Elastic modulus, dissipation, stiffness [11] | Very fast | High-resolution mapping, dynamic processes |

| Multifrequency AFM | Excites and detects multiple cantilever frequencies simultaneously [13] | Elastic modulus, surface potential, composition [13] | Fast | Complex materials, microplastics, biological systems |

Technical Principles and Methodologies

Force Volume Mode represents the foundational approach for nanomechanical mapping, acquiring complete force-distance curves (FDCs) at each pixel of the sample surface [11]. These curves are generated by modulating the tip-sample distance while recording cantilever deflection, typically using triangular or sinusoidal waveforms [11]. The approach and retraction sections of FDCs provide complementary information: while approach curves primarily inform about elastic properties, retraction curves reveal adhesive interactions and inelastic processes [11]. Hysteresis between approach and retraction cycles indicates energy dissipation mechanisms, characteristic of viscoelastic materials like living cells [11]. The mechanical properties are extracted by fitting these experimental curves to contact mechanics models, with the Hertz model being most common for elastic properties, and Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) or Derjaguin-Müller-Toporov (DMT) models applied for adhesive contacts [12].

Nano-DMA techniques, inspired by macroscopic dynamic mechanical analysis, characterize viscoelastic properties by applying small oscillatory indentations to the sample while monitoring the time lag between the applied force and resulting deformation [11]. In practice, the tip is first approached to a predefined setpoint force (typically 1-20 nN) to establish a reference indentation depth of 100-500 nm, after which an oscillatory signal (10-50 nm amplitude) is applied while maintaining contact [11]. The viscoelastic properties are encoded in the phase shift between the driving excitation and the mechanical response, allowing calculation of storage and loss moduli that describe the elastic and viscous components of material behavior, respectively [11]. This method is particularly valuable for studying time-dependent mechanical properties in polymers and biological samples.

Parametric Methods, including bimodal AFM and contact resonance AFM, operate by driving the cantilever at its resonant frequency and monitoring changes in oscillation parameters (amplitude, phase, frequency) induced by tip-sample interactions [11]. These changes are then correlated with mechanical properties through analytical expressions or calibration procedures [11]. The significant advantage of parametric methods lies in their rapid acquisition speed, as they avoid the need for complete force-distance curves at each pixel. This enables high-speed mapping of mechanical properties, making them suitable for studying dynamic processes and reducing the risk of sample damage or tip wear during prolonged contact.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Protocol for AFM Nanomechanical Characterization

Sample Preparation Requirements vary significantly depending on material type. For biological samples like biofilms, appropriate immobilization is crucial. Biofilms can be grown on AFM-compatible substrates such as glass coverslips, often treated with adhesion-promoting chemicals like PFOTS [7]. For protein samples, mica surfaces provide an atomically flat substrate; typical preparation involves adhering muscovite mica discs to support discs and air-drying before protein adsorption [14]. Maintaining physiological conditions is essential for living samples, requiring liquid imaging with appropriate buffers [7] [12].

Cantilever Selection and Calibration profoundly impact measurement accuracy. Soft cantilevers (spring constants 0.01-1 N/m) are preferred for biological samples to avoid excessive deformation or damage [12]. The precise determination of spring constant is typically performed using thermal tuning methods before measurements. Tip geometry must be considered when selecting contact mechanics models, with spherical tips often preferred for soft materials to minimize local stresses [12].

Measurement Parameters should be optimized for each sample type. For force volume mapping, maximum indentation force should be limited to prevent sample damage (typically 1-5 nN for cells and biofilms) [12]. Indentation depth should not exceed 10-20% of sample thickness to avoid substrate effects [12]. For nano-DMA measurements, oscillation amplitudes of 1-5 nm are typically used, with frequencies ranging from a few Hz to several hundred Hz depending on the specific viscoelastic relaxation processes under investigation [11].

Data Analysis Workflow begins with converting deflection vs. position data to force vs. separation curves. The contact point must be accurately identified, after which the indentation portion is fitted with appropriate contact mechanics models [12]. For heterogeneous samples, statistical analysis of parameter distributions across multiple locations and samples provides more meaningful characterization than single-point measurements.

Advanced Integrated Workflow for Correlated AFM-Confocal Biofilm Imaging

The integration of AFM nanomechanical data with confocal microscopy represents a powerful approach for comprehensive biofilm characterization, linking structural organization with mechanical properties.

Correlated Imaging Protocol begins with growing biofilms on optically transparent substrates suitable for both techniques. Initial confocal imaging identifies regions of interest based on architectural features while maintaining biofilm viability. Following confocal characterization, the same regions are located for AFM analysis without disturbing the sample. For mechanical mapping, force volume or nano-DMA modes are employed with appropriate parameters (soft cantilevers, minimal forces). Following AFM measurement, a second confocal scan verifies structural integrity and registers any changes.

Data Integration Challenges include coordinate system alignment between instruments and accounting for temporal evolution between sequential measurements. Recent advances address these limitations through specialized hardware that integrates both modalities and computational approaches using machine learning for image registration and data fusion [7] [10].

Large-Area AFM Implementation overcomes the traditional limitation of small scan sizes (<100 µm) that has restricted AFM's utility for studying millimeter-scale biofilm architectures [7]. Automated large-area AFM approaches systematically tile high-resolution images across extended regions, with machine learning algorithms seamlessly stitching adjacent scans and correcting for distortions [7]. This innovation enables investigation of spatial heterogeneity in mechanical properties across structurally complex biofilms, directly correlating local nanomechanical behavior with larger-scale organizational patterns observed in confocal microscopy [7].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for AFM Nanomechanical Characterization

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Specification Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Cantilevers | Force sensing and indentation | Spring constant: 0.01-1 N/m for soft materials; Tip geometry: spherical for homogeneous stress distribution [12] |

| Functionalized Tips | Specific molecular interactions | Chemical force microscopy: tips modified with specific functional groups or biomolecules [12] |

| Biofilm Substrates | Sample support and immobilization | PFOTS-treated glass coverslips; Freshly cleaved mica for protein immobilization [7] [14] |

| Imaging Buffers | Maintain physiological conditions | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or appropriate growth media for living samples [7] [12] |

| Calibration Standards | Instrument verification | Reference samples with known mechanical properties (e.g., poly dimethyl siloxane) [12] |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Techniques

Technique Capability Matrix

AFM nanomechanical characterization operates within a broader ecosystem of materials characterization techniques, each with distinct strengths and limitations. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) excels at non-invasive 3D structural imaging of hydrated biofilms with molecular specificity through fluorescent labeling but provides no direct mechanical information [7] [10]. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) offers superior surface topographic resolution but requires sample dehydration and coating, potentially altering native mechanical properties and preventing liquid imaging [7]. Raman spectroscopy provides detailed chemical composition data but lacks spatial resolution for fine structural features and offers no mechanical property data [7] [10].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of AFM vs. Alternative Characterization Techniques

| Technique | Spatial Resolution | Mechanical Property Data | Sample Requirements | Imaging Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFM | ~1 nm lateral; ~0.1 nm vertical [7] | Comprehensive: elasticity, adhesion, viscoelasticity [11] [12] | Minimal preparation; can be native state | Ambient, liquid, or controlled gas [7] [12] |

| Confocal Microscopy | ~200 nm lateral; ~500 nm axial [10] | None | Fluorescent labeling often required | Primarily liquid for biological samples |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | ~1 nm lateral [7] | None | Dehydration, conductive coating | High vacuum typically required [7] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | ~300-500 nm lateral [10] | Indirect inference only | Minimal for surface-enhanced approaches | Ambient or liquid possible |

AFM's unique capability to provide quantitative mechanical property data with high spatial resolution under physiological conditions represents its most significant advantage over alternative techniques. This enables researchers to establish direct structure-function relationships in native environments, particularly valuable for dynamic biological systems like biofilms [7] [12].

Performance Benchmarking in Biofilm Research

In the specific context of biofilm research, AFM demonstrates particular advantages for investigating early attachment events and surface interactions at the single-cell level. High-resolution AFM imaging has revealed intricate details of bacterial flagella and their coordination during surface attachment, showing flagellar structures measuring approximately 20-50 nm in height and extending tens of micrometers across surfaces [7]. These observations provide mechanical insights into initial biofilm formation that are inaccessible to optical techniques.

For investigating the structural role of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in biofilm mechanics, AFM has identified distinctive mechanical signatures associated with matrix components, enabling correlation of local composition with mechanical function [7]. When integrated with confocal microscopy through correlated imaging workflows, AFM mechanical data can be directly linked with spatial organization and compositional heterogeneity observed over larger areas, creating comprehensive models of biofilm behavior [7] [10].

The application of machine learning and artificial intelligence is transforming AFM capabilities in biofilm research, automating processes such as image segmentation, cell detection, and classification [7]. These advances enable high-throughput analysis of biofilm mechanical properties across statistically relevant areas, overcoming previous limitations from small sample sizes and operator-dependent variability [7] [10].

Applications in Biofilm Research and Beyond

Case Study: Nanomechanical Mapping of Bacterial Biofilms

Recent research employing large-area automated AFM has revealed remarkable spatial heterogeneity in the mechanical properties of developing biofilms. Studies of Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms demonstrated distinct organizational patterns during early formation, with cells orienting in specific directions to form characteristic honeycomb structures [7]. AFM nanomechanical mapping correlated these architectural arrangements with local variations in mechanical properties, providing insights into how structural organization influences biofilm integrity and function.

The detailed characterization of flagellar interactions through AFM imaging suggests that flagellar coordination plays a role in biofilm assembly beyond initial attachment [7]. These mechanostructural investigations at the single-cell level provide foundational knowledge for developing strategies to control biofilm formation in industrial and medical contexts.

Environmental and Biomedical Applications

In environmental science, AFM nanomechanical characterization has proven valuable for investigating micro- and nanoplastic (MNP) particles in groundwater systems [13]. Multifrequency AFM techniques distinguish pristine and aged MNPs through differences in elastic modulus while simultaneously providing detailed morphological and roughness data [13]. These investigations reveal that environmental MNPs form aggregates with surface roughness one to two orders of magnitude higher than laboratory-aged particles, suggesting significantly different adsorption capacities for environmental pollutants [13].

In biomedical applications, AFM has revealed that cancer cells exhibit different mechanical properties than their healthy counterparts, with malignant cells typically showing decreased stiffness [12]. Although more sophisticated investigations are required for reliable prognostic applications, these mechanical differences offer potential diagnostic avenues. Similarly, AFM investigations of bacterial response to antibiotics provide insights into mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance, while studies of virus capsids have correlated increased stiffness with reduced infectivity, informing new antiviral strategies [12].

The field of AFM nanomechanical characterization continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future development. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is enhancing data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation across multiple domains [11] [7] [10]. In biofilm research specifically, AI-driven approaches are enabling automated segmentation, classification, and analysis of complex structural and mechanical data, facilitating high-throughput investigation of biofilm heterogeneity and response to environmental perturbations [7] [10].

Advances in computational methods are bridging the resolution gap between AFM topographic imaging and atomic-scale structural models. Tools like AFMfit and NMFF-AFM employ flexible fitting procedures to deform atomic models to match multiple AFM observations, generating conformational ensembles that describe experimental data with atomistic precision [15] [16]. Similarly, the ProFusion framework enables 3D reconstruction of protein complex structures from multi-view AFM images using deep learning models trained on synthetic AFM data [14]. These approaches are extending AFM's utility from structural characterization to understanding dynamic molecular processes.

For correlated AFM-confocal studies of biofilms, future developments will likely focus on real-time integrated imaging systems that eliminate the temporal gap between measurements. Combined with machine learning algorithms for data fusion and analysis, these advances will enable comprehensive four-dimensional characterization of biofilm development, correlating structural, chemical, and mechanical evolution across spatial scales from single molecules to multicellular communities.

In conclusion, AFM nanomechanical characterization provides unique capabilities for investigating material properties across diverse research domains. Its particular strength lies in correlating mechanical behavior with structural features at the nanoscale under physiologically relevant conditions. When integrated with complementary techniques like confocal microscopy, AFM enables researchers to establish comprehensive structure-function relationships in complex biological systems, offering powerful insights for biomedical, environmental, and materials applications.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) is a high-resolution fluorescence imaging technique that has become a cornerstone tool in biomedical research for visualizing the three-dimensional architecture of biological samples and assessing cell viability. Its core principle lies in the use of spatial filtering to achieve optical sectioning, providing a significant advantage over conventional widefield fluorescence microscopy [17]. In CLSM, a laser of specific excitation wavelength is scanned across the specimen, and the emitted fluorescent signal is detected only from the plane currently in focus, with out-of-focus light excluded by a pinhole aperture placed in front of the detector [17]. This mechanism enables the acquisition of sharp images from a single focal plane within fluorescently labeled specimens.

The capability to reject out-of-focus light allows researchers to construct detailed three-dimensional images by sequentially scanning and stacking optical sections (z-stacks) at different depths [17]. This is particularly valuable for studying complex structures such as biofilms, tissue models, and cellular spheroids, where understanding the 3D organization is critical. Furthermore, the digital nature of CLSM images facilitates advanced image processing and quantitative analysis, making it an indispensable tool for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require precise morphological and viability data from within 3D microenvironments [17].

Figure 1: Optical sectioning in CLSM. A pinhole blocks out-of-focus light, collecting signal only from the focal plane.

Visualizing 3D Architecture and Quantifying Viability

Resolving Three-Dimensional Microenvironments

CLSM's optical sectioning capability enables the non-invasive exploration of 3D biological structures at high resolution. Under optimal conditions, CLSM can achieve a spatial resolution of approximately 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.8 micrometers (X, Y, Z), supporting detailed analyses of subcellular structures [17]. This has proven invaluable for characterizing the architecture of hepatocyte spheroids (HCS), which develop a multilayered structure with site-dependent cell viability, including highly viable cell layers, low active cell layers, and necrotic cores [18]. Similarly, in biofilm research, CLSM allows for in-depth analysis of the extracellular polymeric matrix without killing or damaging the biological structure, providing insights into biofilm composition, structure, and metabolism [19].

The technique has also been applied to study the distribution of fluorescent proteins (FPs) in coral tissues at the cellular level, revealing species-specific patterns. For instance, in Stylophora corals, green fluorescent proteins (GFPs) were concentrated in the intermesenterial muscle bands of the polyp, while cyan fluorescent proteins (CFPs) were located at the tips of the tentacles [20]. Such high-resolution visualization of pigment distribution helps elucidate photobiological adaptations and stress responses.

Quantitative Viability Assessment

A key application of CLSM is the quantitative assessment of cell viability within 3D structures. This is typically achieved using viability indicators and fluorescent stains that distinguish live from dead cells based on membrane integrity or metabolic activity [19]. For example, in hepatocyte spheroids, cell staining has been used as an indicator of cell viability as determined by the integrity of the cell wall membrane [18]. However, the large diameter and dense multilayered structure of thick specimens can result in uneven penetration of staining reagents, causing intrinsic fluorescence intensity errors in imaging and affecting the accurate measurement of cell viability at the center [18]. This limitation necessitates careful interpretation of viability data from deep within 3D samples.

CLSM has been benchmarked against other viability assessment methods. In a study quantifying site-dependent cell viability in hepatocyte spheroids, CLSM results were compared with those obtained from dynamic optical coherence tomography (D-OCT), a non-invasive, label-free method that detects cellular activity based on intrinsic motion patterns [18]. The study found that cells in C3A hepatocyte spheroids were active mainly in the range of 8 to 13 Hz when detected by D-OCT, and the D-OCT results showed a high degree of correspondence with CLSM data, validating both approaches for viability assessment [18].

Comparative Analysis: CLSM vs. Alternative Imaging Modalities

The selection of an appropriate imaging technique depends on the specific research requirements, including resolution needs, sample thickness, viability constraints, and the necessity for live or dynamic imaging. The table below provides a structured comparison of CLSM with other prominent bioimaging techniques.

Table 1: Technical comparison of CLSM with other bioimaging techniques

| Technique | Resolution | Imaging Depth | Viability Assessment | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSM | ~0.2 × 0.2 × 0.8 µm (X, Y, Z) [17] | ~100-150 µm [17] | Fluorescent viability stains (e.g., membrane integrity dyes) [19] [18] | Optical sectioning, 3D reconstruction, reduced out-of-focus blur [17] | Photobleaching, phototoxicity, limited depth [17] [21] |

| Multiphoton Microscopy | Similar to CLSM [17] | Up to 2-3 times deeper than CLSM [17] | Same fluorescent stains as CLSM | Deeper tissue penetration, reduced photobleaching outside focal plane [17] | Higher cost, complex laser systems [17] |

| Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy (LSFM) | Varies with objective NA | Several mm (with clearing) [21] | Same fluorescent stains as CLSM | Very low phototoxicity, fast volumetric imaging [21] | Lower resolution than CLSM, requires specialized sample mounting [21] |

| Dynamic Optical Coherence Tomography (D-OCT) | Axial: 1-10 µm, Lateral: 1-10 µm [18] | 1-3 mm [18] | Label-free, based on cellular motility frequencies [18] | Non-destructive, label-free, deep penetration [18] | No molecular specificity, indirect viability measure [18] |

| Widefield Fluorescence Microscopy | Diffraction-limited | Limited by scattering | Fluorescent viability stains | Simple, fast, cost-effective [1] | Out-of-focus blur, unsuitable for thick samples [17] [21] |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Nanometer scale | Surface imaging only | Not applicable for live cells | Ultra-high resolution surface details [1] | Requires fixation, no live imaging [17] |

Table 2: Performance comparison for specific research applications

| Application | CLSM Performance | Competitive Technique Performance | Key Differentiating Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilm Structure Analysis | High-resolution 3D visualization of matrix and bacterial colonies [19] | SEM: Higher surface resolution but no live imaging [1] | CLSM enables live imaging of hydrated biofilms; SEM provides superior surface detail but requires fixation [19] [1] |

| Cell Viability in 3D Spheroids | Quantitative with fluorescent stains; limited by dye penetration in dense spheroids [18] | D-OCT: Label-free viability assessment based on cellular motility [18] | D-OCT enables long-term non-invasive monitoring; CLSM provides molecular specificity but risks phototoxicity [18] |

| Deep Tissue Imaging | Limited to ~100-150 µm due to light scattering [17] | Multiphoton: 2-3 times deeper penetration than CLSM [17] | Multiphoton's near-infrared excitation scatters less, enabling deeper imaging in scattering tissues [17] |

| Long-term Live Cell Imaging | Phototoxicity limits duration [21] | LSFM: Significantly reduced phototoxicity [21] | LSFM illuminates only the detected plane, enabling longer studies with minimal damage [21] |

| Correlative Nanomechanics + Fluorescence | Compatible with AFM integration [22] | Super-resolution SIM + AFM: Higher optical resolution [22] | SR-SIM provides ~2x better resolution than CLSM but requires more complex reconstruction [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: Viability Assessment in 3D Spheroids

The following protocol details the methodology for evaluating cell viability in 3D hepatocyte spheroids using CLSM, as referenced in [18]:

- Spheroid Generation: Prepare hepatocyte spheroids using a liquid overlay technique on concave-bottomed culture wells with low adhesion. Inoculate C3A hepatocyte suspensions at concentrations of 10⁵ cells/ml with varying volumes (20-100 µl) to control spheroid size.

- Culture Conditions: Maintain spheroids in specialized culture medium at 37°C and 5% CO₂, replacing medium every 48 hours.

- Viability Staining: Apply appropriate fluorescent viability stains. Common approaches include:

- Membrane integrity dyes: Such as propidium iodide (dead cells) combined with calcein-AM (live cells).

- Metabolic indicators: That reflect cellular activity.

- CLSM Imaging:

- Use objectives with appropriate numerical aperture (e.g., 40×/0.60 or 63×/1.4 oil immersion).

- Set laser wavelength to match fluorophore excitation (e.g., 552 nm).

- Acquire z-stacks through entire spheroid with optimal step size (e.g., 1-5 µm).

- Maintain minimal laser power to reduce phototoxicity.

- Image Analysis:

- Reconstruct 3D volumes from z-stacks.

- Segment viable and necrotic regions based on fluorescence signals.

- Quantify viable cell volume ratio relative to total spheroid volume.

Protocol: CLSM and AFM Correlative Imaging

This protocol outlines the procedure for correlative CLSM and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) imaging, enabling simultaneous topological, nanomechanical, and fluorescence characterization [22]:

- Sample Preparation:

- Culture cells expressing fluorescently tagged proteins (e.g., EGFP-MCT1) on glass coverslips compatible with both techniques.

- Alternatively, prepare biofilm samples with appropriate fluorescent labeling of matrix components.

- Instrument Setup:

- Mount AFM on inverted CLSM microscope.

- Select cantilevers appropriate for biological samples (e.g., nominal resonance frequency of 90 kHz in air, spring constant of 0.3 Nm⁻¹).

- Align AFM laser spot on cantilever using CCD camera.

- Simultaneous Imaging:

- Engage AFM in force spectroscopy-based mode (e.g., Quantitative Imaging mode).

- Set Z-cantilever velocity and maximum Z-length (e.g., 250 µm/s at max Z-length of 1.5 µm).

- Acquire CLSM images simultaneously using appropriate laser wavelengths and detection settings.

- For fluorescence acquisition, use high-aperture objectives (e.g., 100× Oil, NA 1.49).

- Data Correlation:

- Overlay AFM topological/mechanical maps with CLSM fluorescence images.

- Correlate nanomechanical properties with fluorescence localization patterns.

Figure 2: Workflow for correlative CLSM and AFM imaging, combining fluorescence with nanomechanical data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for CLSM experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Viability Stains | Distinguish live/dead cells based on membrane integrity or metabolic activity | Viability assessment in 3D spheroids, biofilms [18] | Penetration efficiency in dense structures varies; potential phototoxicity |

| Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins (e.g., GFP, YFP) | Label specific proteins or cell types; reporter gene expression | Visualization of protein localization, gene expression patterns [17] [22] | Enables long-term studies without external staining; may require transfection/transduction |

| Immunofluorescence Labels | Target-specific staining of cellular components | Identification of specific cell types, extracellular matrix components [17] | Requires sample fixation; enables multiplexing with multiple antibodies |

| Refractive Index Matching Solutions | Reduce light scattering in thick samples | Deep tissue imaging, improved penetration in 3D samples [21] | May not be compatible with live cell imaging; ongoing development of biocompatible options |

| Specialized CLSM Objectives | High-resolution light collection | All CLSM applications | High numerical aperture (e.g., 1.4) objectives critical for optimal resolution [23] |

| Photostabilizing Reagents | Reduce photobleaching during extended imaging | Long-term time-lapse experiments | Enables longer imaging sessions but may have biological effects |

Integration with Atomic Force Microscopy for Correlative Nanomechanics

The integration of CLSM with Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) creates a powerful correlative imaging platform that combines nanomechanical characterization with biochemical specificity. This combination is particularly valuable for biofilm research, where understanding the relationship between mechanical properties and 3D structure is essential [4] [22]. AFM provides quantitative measurements of mechanical properties including stiffness and viscosity with sub-cellular sensitivity, while CLSM simultaneously maps the 3D distribution of fluorescently labeled components [4].

Technical implementations of combined CLSM-AFM platforms have demonstrated successful simultaneous operation, though careful system design is required to minimize interference [22]. For instance, the fluorescence excitation light must be controlled to prevent perturbation of the AFM cantilever operation [22]. Similarly, noise transfer from the optical microscope to the AFM must be mitigated to maintain measurement integrity. Despite these challenges, the correlative approach provides a mechanistic understanding of biological processes governing the unique functions of tissues and microbial communities [4].

This integrated methodology is particularly relevant for investigating how the extracellular polymeric matrix contributes to the mechanical stability of biofilms, or how cellular mechanical properties change during differentiation in 3D spheroids. The combination of AFM-based tissue mechanobiology with CLSM visualization enables researchers to correlate changes in mechanical properties with specific biochemical or structural alterations occurring during development, physiological adaptation, or disease progression [4].

Biofilms are complex, three-dimensional microbial communities embedded in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. This architecture is fundamental to their resilience against antimicrobial agents and host immune responses, posing significant challenges in medical and industrial contexts [24] [1]. Understanding the intricate structure-function relationships within biofilms requires imaging techniques that can capture both their detailed nanoscale surface properties and their broader 3D organization. While numerous microscopy methods are employed in biofilm research, Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) and Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) represent two powerful but fundamentally different approaches. Independently, each technique provides a valuable yet incomplete picture; AFM excels in surface topography and nanomechanics, whereas CLSM is unparalleled for 3D architectural visualization within hydrated, living samples. This guide objectively compares the performance of AFM and CLSM and demonstrates, through experimental data and protocols, why their correlative application is imperative for a holistic understanding of biofilm dynamics, mechanics, and response to external stimuli.

Technique Comparison: Strengths and Limitations

The following table summarizes the core capabilities of AFM and CLSM, highlighting their complementary nature.

Table 1: Core Capabilities of AFM and CLSM in Biofilm Research

| Feature | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Sub-nanometer vertical; molecular-scale lateral [7] [25] | Diffraction-limited (~200 nm lateral, ~500 nm axial) [26] |

| Key Outputs | 3D topography, nanomechanical properties (elasticity, adhesion), molecular interaction forces [24] [5] [25] | 3D architecture, biovolume, thickness, spatial distribution of labeled components [24] [27] |

| Sample Environment | Can operate in liquid under physiological conditions [28] [25] | Ideal for hydrated, living samples; requires immersion objective [29] [27] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; often requires immobilization but no staining [25] | Requires fluorescence labeling (e.g., dyes, tags) which may alter biofilm [24] |

| Primary Limitation | Small scan area (<150×150 µm); surface probe only; slow imaging; potential sample damage [7] [25] | Limited resolution; photobleaching; signal interference from intrinsic biofilm fluorescence [24] |

| Key Application | Quantifying adhesion forces, single-cell stiffness, EPS viscoelasticity [24] [5] | Visualizing live/dead cell stratification, EPS composition, and real-time structural dynamics [24] [27] |

The Synergy of Correlative AFM-CLSM

The limitations of each technique are directly addressed by the strengths of the other. AFM's small field of view makes it difficult to locate representative regions of interest within a heterogeneous biofilm and to contextualize nanoscale measurements within the broader biofilm architecture [7]. Conversely, while CLSM effectively maps the 3D structure, it lacks the resolution and capability to quantify the mechanical properties of the EPS matrix and individual cells, which are critical to biofilm stability and function [24] [28]. By combining them, researchers can pinpoint specific locations with CLSM and then use AFM to perform detailed topographical and nanomechanical analyses at those sites.

This synergy is powerfully illustrated in a 2018 study that combined Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), a meso-scale imaging technique, with AFM to investigate oral biofilms. The research revealed that increasing sucrose concentration decreased the biofilm's Young's modulus (a measure of stiffness) while increasing cantilever adhesion, changes linked to variations in EPS content visualized via OCT [28]. This study exemplifies the "correlative imperative"—the structural insights from imaging informed the interpretation of the mechanical data, creating a comprehensive structure-property relationship unattainable with either technique alone.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters Accessible via AFM and CLSM

| Parameter | Technique | Significance in Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus | AFM [28] [5] | Indicates biofilm stiffness; influences antimicrobial penetration and mechanical stability [24]. |

| Adhesion Forces | AFM [28] [25] | Quantifies cell-surface and cell-cell interactions, crucial for initial attachment and cohesion [24]. |

| Biovolume | CLSM [24] [27] | Measures total biomass, useful for assessing biofilm growth and treatment efficacy [27]. |

| Biofilm Thickness | CLSM [29] [27] | Determines the vertical dimension of the biofilm, related to nutrient gradients and metabolic activity. |

| Surface Roughness | AFM [30] | Influenced by microcolony formation; a parameter for quantitative morphological analysis [24]. |

| Substratum Coverage | CLSM [27] | Percentage of surface area covered by biofilm; indicates adhesion and spreading. |

Experimental Protocols for Correlative Imaging

Implementing a correlative AFM-CLSM workflow requires careful planning to maintain sample integrity between measurements. Below is a generalized protocol for a sequential analysis, where the same sample is first imaged with CLSM and then with AFM.

Correlative Workflow Protocol

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Immobilization

- Substrate: Use a thin, sterile glass coverslip or a specialized AFM dish as the growth substrate. The material must be compatible with high-resolution optics for CLSM and flat enough for stable AFM scanning.

- Biofilm Cultivation: Grow the biofilm on the substrate under controlled conditions relevant to your research question (e.g., flow or static culture) [29].

- Staining (for CLSM): After cultivation, gently rinse the biofilm with an appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS) to remove non-adherent cells. Apply fluorescent stains, such as SYTO 9 for total cells and propidium iodide for dead cells, or conjugated lectins for specific EPS components [24] [27]. Incubate in the dark, then rinse again to remove excess dye.

Step 2: Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

- Mounting: Place the stained, hydrated biofilm sample on the CLSM stage. Ensure it is fully submerged in buffer to prevent dehydration.

- Imaging: Use appropriate laser lines and emission filters for your chosen fluorophores. Acquire z-stacks through the entire biofilm thickness with a step size of 0.5-1.0 µm to reconstruct the 3D architecture.

- Data Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, IMARIS, or instrument-specific software) to calculate parameters like biovolume, thickness, and substratum coverage [27]. Crucially, note the X-Y-Z coordinates of specific regions of interest (ROIs), such as microcolony centers, water channels, or areas with varying fluorescence intensity.

Step 3: Atomic Force Microscopy

- Sample Transfer: Carefully transfer the sample from the CLSM stage to the AFM, keeping it hydrated throughout the process.

- Navigation: Use the optical microscope integrated with the AFM to navigate to the previously mapped ROIs using the recorded coordinates and distinctive morphological features.

- AFM Imaging & Force Spectroscopy:

- Topography Imaging: Perform contact or tapping mode scans in liquid to obtain high-resolution topographical images of the selected ROIs.

- Force Volume Imaging: Acquire 2D arrays of force-distance curves over the ROI. This generates simultaneous maps of topography and mechanical properties like Young's modulus and adhesion [28] [5].

- Probe Selection: Use sharp tips (nominal spring constant ~0.1 N/m) for high-resolution imaging and spherical tips (or colloidal probes, ~0.3-0.4 N/m) for more quantitative, reproducible nanomechanical mapping [28].

Diagram 1: Correlative AFM-CLSM experimental workflow for biofilm analysis.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Correlative AFM-CLSM Biofilm Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Glass Bottom Dishes/Petri Dishes | Sample Substrate | Provides a optically clear and flat surface essential for high-resolution CLSM and stable AFM scanning. |

| Fluorescent Stains (e.g., SYTO 9, Propidium Iodide, Conjugated Lectins) | Biomass and Component Labeling | Allows visualization of different biofilm components (live/dead cells, specific polysaccharides) in CLSM. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Buffer | Maintains physiological conditions (pH, osmolarity) during rinsing and imaging to preserve native biofilm structure. |

| AFM Cantilevers | Probing the Sample | The choice of tip (sharp vs. colloidal) determines the resolution and type of nanomechanical data acquired. |

| Calibration Grids (e.g., TGZ1-TGZ3) | AFM Instrument Calibration | Verifies the scanner's accuracy in X, Y, and Z dimensions, ensuring reliable and quantifiable measurements. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The correlative approach is being supercharged by technological advancements. A landmark 2025 study introduced an automated large-area AFM approach capable of scanning millimeter-scale areas, a significant leap from the traditional sub-150 µm range [7]. This method, aided by machine learning for image stitching and cell classification, revealed a preferred cellular orientation and a distinctive honeycomb pattern in Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms, features previously obscured by the limited field of view. When correlated with CLSM, such large-area AFM datasets can directly link nanoscale cellular arrangements and flagellar interactions observed by AFM to the overall community architecture visualized by CLSM.

Future directions point towards even deeper integration. Machine learning and AI are transforming AFM by automating routine tasks, optimizing scanning, and enhancing data analysis, making the correlation of large, information-rich datasets from both techniques more efficient [7]. Furthermore, the development of microfluidic flow cells that are compatible with both AFM and CLSM allows for the real-time observation of biofilm development, structural changes, and mechanical evolution under controlled hydrodynamic and chemical conditions [29]. This enables researchers to not only correlate structure and mechanics but also to observe the dynamic interplay between them in response to treatments, such as the introduction of antimicrobial agents or mechanical stress.

Diagram 2: How AFM and CLSM illuminate different mechanisms behind a common biofilm phenotype.

The evidence is clear: the combination of AFM and CLSM is not merely beneficial but imperative for advanced biofilm research. While AFM provides unparalleled insight into the nanomechanical and topographical properties that govern biofilm stability and adhesion, CLSM delivers an essential understanding of the three-dimensional spatial architecture and composition in a hydrated, near-native state. Their correlative application directly addresses the inherent limitations of each standalone technique, enabling researchers to build robust, quantitative structure-property relationships. As demonstrated by the latest research in large-area AFM and machine learning, the continued evolution of this correlative paradigm will be pivotal in unraveling the complex dynamics of biofilms and developing effective strategies to control them in medical, industrial, and environmental settings.

A Practical Workflow for Correlative AFM-Confocal Microscopy in Biofilm Analysis

Sample Preparation Strategies for Multimodal Imaging

The integration of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) with confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) represents a powerful multimodal platform for biofilm research, enabling the correlation of nanoscale structural and mechanical properties with biochemical composition and viability data in a biological context [31] [2]. The primary challenge in such correlative studies lies in designing sample preparation protocols that simultaneously satisfy the distinct and often conflicting requirements of each technique without compromising the biofilm's native state. AFM demands relatively clean, fixed, or dry samples for optimal nanomechanical mapping and high-resolution topographical imaging, typically requiring substrates that are flat, rigid, and conductive [7] [32]. In contrast, CLSM relies on optical transparency and frequently involves hydrated, fluorescently stained samples to visualize internal structures and biological activity in three dimensions [2] [33]. This article objectively compares sample preparation strategies for standalone and correlated imaging, providing a structured guide to help researchers navigate the methodological trade-offs. By presenting standardized protocols and quantitative data on their outcomes, we aim to facilitate robust experimental design for correlating AFM nanomechanics with confocal biofilm imaging.

Comparative Analysis of Imaging Techniques and Their Sample Requirements

A fundamental understanding of each technique's operating principles and limitations is a prerequisite for designing effective multimodal sample preparation. The following table summarizes the core requirements for AFM, CLSM, and their integrated application.

Table 1: Core Requirements for AFM, CLSM, and Multimodal Imaging

| Imaging Technique | Spatial Resolution | Key Outputs | Ideal Sample State | Critical Substrate Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | ~0.1 nm laterally, ~0.01 nm vertically [31] | 3D topography, nanomechanical properties (stiffness, adhesion, viscoelasticity) [32] | Clean, fixed, or dry; can be in liquid [7] | Flat, rigid, low roughness (e.g., glass, mica, silicon wafers) [7] |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) | ~200 nm laterally, ~500 nm axially [33] | 3D morphology, biochemical localization, cell viability (via live/dead staining) [2] | Hydrated, fluorescently stained (live or fixed) [33] | Optically transparent (e.g., glass coverslips) [33] |

| Correlative AFM-CLSM | Combines nanoscale (AFM) and sub-diffraction (CLSM) resolution | Links nanomechanics with biochemical identity and spatial distribution [31] [2] | Compromise: Fixed and stained, but may be hydrated or dry for sequential imaging | Must satisfy both techniques: optically transparent, flat, and rigid [31] |

Sample Preparation Workflows: A Comparative Guide

Sample preparation strategies can be broadly categorized by the final state of the biofilm, which directly dictates the type of information that can be obtained. The choice of protocol involves critical trade-offs between preserving native structure, maintaining biological activity, and achieving technical compatibility.

Table 2: Comparison of Sample Preparation Protocols for Biofilm Imaging

| Preparation Strategy | Key Steps (Simplified) | Compatibility | Impact on Data | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal Preparation (Native State) | 1. Grow biofilm on suitable substrate (e.g., glass).2. Gently rinse with buffer to remove planktonic cells.3. Image in liquid [7] [31]. | AFM (in liquid): HighCLSM (live): HighCorrelative: High | Preserves native structure & mechanics; allows dynamic studies. | Investigating live biofilm processes, real-time antibiotic effects [31]. |

| Chemical Fixation | 1. Grow and rinse biofilm.2. Fix with aldehyde (e.g., 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% PFA).3. Rinse with buffer [2]. | AFM: HighCLSM (fixed): HighCorrelative: High | Stabilizes structure; may alter nanomechanical properties. | Preserving spatial relationships for high-resolution structural correlation. |

| Chemical Fixation & Staining | 1. Fix biofilm.2. Permeabilize (if needed).3. Apply fluorescent stains (e.g., FISH, FITC-ConA).4. Rinse and mount [2] [33]. | AFM: Medium*CLSM: EssentialCorrelative: Essential | Enables biochemical specificity in CLSM; risk of sample contamination or topography alteration for AFM. | Linking nanomechanics with specific molecular components (e.g., EPS). |

| Dehydration & Drying | 1. Fix biofilm.2. Dehydrate with graded ethanol or acetone series.3. Critical point drying or air-drying [7]. | AFM: HighCLSM: Low/NoneCorrelative: Challenging | Causes significant structural collapse; not suitable for most CLSM. | High-resolution AFM topography where hydration is not a concern [7]. |

*AFM on stained samples is possible but requires caution to avoid contaminating the tip with fluorescent dyes.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Correlative AFM-CLSM

The following protocol is adapted from methodologies used in recent studies for investigating early bacterial attachment and biofilm formation, suitable for correlating nanomechanics with confocal data [7] [2].

Methodology: Sample Preparation for Fixed Correlative AFM-CLSM Imaging

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Substrate: PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or bare glass coverslips (#1.5 thickness, 25-35 mm diameter). The PFOTS treatment creates a hydrophobic surface that can modulate bacterial adhesion [7].

- Fixative Solution: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde.

- Staining Solution: PBS containing fluorescent stains (e.g., SYTO 9 for nucleic acids, FITC-labeled Concanavalin A for polysaccharides, propidium iodide for dead cells), with concentrations as per manufacturer's guidelines.

- Wash Buffer: Sterile physiological buffer (e.g., 10 mM PBS or 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4).

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Place a sterile glass coverslip in a petri dish or flow cell. For hydrophobic surfaces, treat with PFOTS or similar silane [7].

- Biofilm Growth: Inoculate with the bacterial strain of interest (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343) in an appropriate liquid growth medium. Incubate for the desired duration to form early-stage biofilms or microcolonies [7].

- Gentle Rinsing: Carefully remove the substrate from the growth medium and immerse it in wash buffer to remove non-adherent planktonic cells. Avoid high shear forces that could disrupt delicate surface attachments.

- Chemical Fixation: Immerse the sample in the glutaraldehyde fixative solution for a minimum of 1 hour at 4°C. This step cross-links and stabilizes the biofilm structure.

- Buffer Rinse: Rinse the fixed sample three times (5 minutes each) with wash buffer to remove excess fixative.

- Fluorescent Staining: Incubate the sample with the chosen staining solution in the dark for 15-30 minutes.

- Final Rinse: Rinse the sample gently with wash buffer to remove unbound stain.

- Mounting for Imaging: For sequential imaging, the sample can be air-dried for AFM first, then mounted for CLSM. For simultaneous imaging, keep the sample hydrated and mount in a liquid cell.

Experimental Workflow and Data Correlation Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway and key decision points for conducting a correlative AFM-CLSM study on biofilms, from sample preparation through data analysis.

The strategic preparation of biofilm samples is the most critical determinant of success in multimodal studies seeking to correlate AFM-derived nanomechanics with confocal microscopy imaging. No single protocol is universally superior; the choice must be guided by the specific research question, whether it demands the preservation of live dynamics or the stabilized, stained structure for compositional analysis. As the field advances, the integration of machine learning for image stitching and analysis [7], coupled with more sophisticated correlative workflows, will further minimize the compromises inherent in sample preparation. By objectively evaluating the trade-offs outlined in this guide, researchers can make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and biological relevance of their multimodal data, ultimately driving a deeper understanding of biofilm architecture and function.

The study of biofilms, complex microbial communities encased in extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), requires analytical methods that can capture both their three-dimensional architecture and their mechanical properties [7] [1]. While Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) excels at visualizing the spatial organization and biochemical characteristics of biofilms through optical sectioning and fluorescence, Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provides complementary nanoscale topographical imaging and quantitative mechanical property mapping [34] [35]. Individually, each technique offers valuable but incomplete insights; together, they enable researchers to correlate structural features with mechanical function. This guide examines the sequential integration of 3D CLSM mapping with AFM nanomechanics, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for studying biofilm organization, resilience, and response to therapeutic interventions.

The limitations of single-technique approaches become particularly evident when studying heterogeneous structures like biofilms. CLSM provides exceptional volumetric imaging of hydrated, living biofilms but lacks the resolution to visualize individual bacterial appendages or measure mechanical properties [1]. Conversely, AFM achieves nanometer-scale resolution and can quantify elastic modulus, adhesion, and viscoelastic properties, but typically examines small surface areas that may not represent broader biofilm architecture [7] [35]. The correlative approach bridges this scale gap, enabling researchers to identify regions of interest with CLSM and subsequently characterize their nanomechanical properties with AFM. This protocol is particularly valuable for investigating structure-function relationships in biofilms, which exhibit remarkable spatial heterogeneity in both composition and mechanical behavior [7] [1].

Technical Comparison of Imaging Modalities

Fundamental Principles and Capabilities

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) operates on the principle of optical sectioning, where a pinhole eliminates out-of-focus light, allowing high-resolution imaging at specific depths within a sample [34]. By collecting sequential z-plane images, CLSM reconstructs three-dimensional representations of biofilms, typically with a lateral resolution of approximately 200 nm and axial resolution of 500-700 nm. CLSM predominantly provides qualitative and spatial information about biofilm architecture, matrix distribution, and cellular organization through fluorescent labeling techniques [1] [34].

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) functions by scanning a sharp probe attached to a flexible cantilever across a sample surface while monitoring cantilever deflection [36]. AFM captures topographical images with atomic-scale resolution and simultaneously quantifies mechanical properties through force-distance curves [35] [36]. Unlike CLSM, AFM does not require fluorescent labeling or conductive coatings, enabling analysis under near-physiological conditions [36]. Advanced AFM modes like force volume, nano-DMA, and parametric methods generate spatially-resolved maps of mechanical properties including elastic modulus, adhesion, and viscoelasticity [35].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of CLSM and AFM

| Parameter | Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Lateral: ~200 nm, Axial: ~500-700 nm | Sub-nanometer (vertical), Nanometer (lateral) |

| Imaging Depth | Tens to hundreds of micrometers | Surface topology (nanometers) |

| Sample Environment | Physiological conditions possible | Physiological liquids, air, vacuum |

| Key Measurements | 3D architecture, fluorescence localization, viability | Topography, elastic modulus, adhesion, surface roughness |

| Sample Preparation | Fluorescent staining, minimal processing | Often minimal, no labeling required |

| Throughput | Relatively fast (minutes for 3D stack) | Slow (typically minutes to hours per image) |

| Live Cell Imaging | Excellent with appropriate environmental control | Possible but challenging due to scanning speed |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The complementary nature of CLSM and AFM becomes evident when examining their quantitative outputs. CLSM excels at measuring volumetric parameters such as biofilm thickness, biovolume, surface area-to-volume ratios, and spatial distribution of specific fluorescent markers [1]. AFM provides nanomechanical data including Young's modulus (typically 0.1-100 kPa for biological samples), adhesion forces (pN to nN range), and viscoelastic parameters [35] [36]. When applied sequentially, these techniques can establish correlations between biofilm localization patterns and their mechanical properties, offering insights into how structural organization influences function.

Table 2: Measurement Capabilities and Experimental Data Outputs

| Measurement Type | CLSM Capabilities | AFM Capabilities | Representative Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | ~200 nm lateral, ~500 nm axial | <1 nm vertical, <5 nm lateral | AFM resolves individual flagella (~20-50 nm height) [7] |

| Structural Imaging | 3D architecture, matrix distribution, microcolonies | Surface topography, cellular morphology, appendages | AFM visualizes honeycomb patterns in Pantoea sp. biofilms [7] |

| Mechanical Properties | Limited to indirect inferences | Direct quantification of elastic modulus, adhesion | Young's modulus maps with nanoscale resolution [35] [36] |

| Chemical Specificity | Excellent with fluorescent labeling | Limited without functionalized tips | CLSM localizes specific EPS components [1] |

| Environmental Flexibility | Physiological conditions, live cell imaging | Air, liquid, controlled atmospheres | AFM measures live cells under physiological conditions [36] |

| Throughput | Moderate to high (3D stacks in minutes) | Low (typically slow scanning) | Large-area automated AFM addresses throughput limitations [7] |

Sequential Imaging Protocol Workflow

Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

The successful integration of CLSM and AFM requires careful experimental planning to maintain sample compatibility between instruments. Biofilms should be grown on substrates suitable for both techniques, typically glass-bottom dishes or coverslips that accommodate high-resolution oil immersion objectives for CLSM and provide sufficiently smooth surfaces for AFM topography scanning [34]. For live cell imaging, environmental control must be maintained throughout the process to preserve biofilm viability and native structure.

The sample preparation protocol begins with culturing biofilms under relevant conditions. For the Conpokal method (combined confocal and AFM), researchers recommend turning on instrument power sources at least one hour before experiments to ensure thermal equilibration [34]. Biofilms are typically fixed in a solution such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or another clear liquid with low autofluorescence to prevent interference with fluorescence detection [34]. For bacterial samples like Streptococcus mutans, preparation involves inoculation in appropriate media overnight, followed by coating experimental dishes with poly-L-lysine solution to enhance surface adhesion approximately one hour before incubation completion [34].

Diagram 1: Sequential Imaging Workflow from CLSM to AFM. This workflow ensures correlative data collection from the same biofilm regions.

CLSM Imaging Protocol

The CLSM imaging phase begins with locating regions of interest within the biofilm sample. For structural assessment, collect z-stacks with appropriate step sizes (typically 0.5-1 μm) to resolve three-dimensional architecture. Optimize laser power, gain, and pinhole size to maximize signal-to-noise ratio while minimizing photobleaching and phototoxicity [34]. When imaging multiple fluorescence channels, sequential scanning prevents bleed-through between channels. For time-lapse experiments investigating biofilm dynamics, ensure environmental control throughout imaging.

CLSM settings must balance resolution requirements with sample viability. Higher numerical aperture objectives (60x or 100x oil immersion) provide superior resolution for detailed structural analysis but reduce working distance, potentially limiting thick biofilm imaging [1] [34]. The resolution advantage of CLSM over conventional light microscopy is particularly evident when imaging complex biofilm architectures, where its optical sectioning capability enables precise three-dimensional reconstruction of microbial communities and extracellular matrix components [1].

Region of Interest Transfer and AFM Integration

Following CLSM characterization, the transfer of specific regions of interest to the AFM represents a critical step in the correlative workflow. Maintain careful coordinate tracking of imaged areas, particularly when using motorized stages with positional encoding. For the Conpokal method that integrates both instruments, this transfer occurs within the same platform, eliminating registration challenges [34]. With separate instruments, fiduciary markers on substrates facilitate relocating the same areas.

Before AFM scanning, select appropriate cantilevers based on experimental requirements. Softer cantilevers (spring constants 0.01-0.1 N/m) are suitable for biological samples to minimize deformation, while stiffer cantilevers (0.5-1 N/m) provide better stability for topographic imaging [34] [35]. Calibrate each cantilever's spring constant and sensitivity using thermal tune or force curve methods on a rigid reference surface (e.g., clean glass or silicon) in the same medium used for biofilm imaging [34].

AFM Nanomechanical Mapping