CRISPR Against Biofilms: Precision Gene Editing to Decipher and Disrupt Resistance Mechanisms

This article comprehensively reviews the transformative role of CRISPR-Cas systems in biofilm research and therapeutic development.

CRISPR Against Biofilms: Precision Gene Editing to Decipher and Disrupt Resistance Mechanisms

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the transformative role of CRISPR-Cas systems in biofilm research and therapeutic development. It covers foundational mechanisms of biofilm-mediated resistance and explores how CRISPR-based tools are used to dissect essential gene functions. The article details advanced methodological applications, including CRISPRi/a for gene regulation and nanoparticle-enhanced delivery for biofilm eradication. It critically addresses key challenges such as off-target effects and delivery inefficiencies, while evaluating CRISPR's performance against conventional and emerging therapies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence and future directions for translating CRISPR precision into clinical biofilm interventions.

Understanding Biofilm Resistance and CRISPR's Mechanistic Foundation

The Global Challenge of Biofilm-Associated Infections and Antibiotic Resistance

Biofilm-associated infections represent a critical front in the global battle against antimicrobial resistance (AMR). These structured communities of microorganisms, embedded in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), are responsible for up to 80% of microbial infections and exhibit up to 1,000-fold greater tolerance to antibiotics compared to their planktonic counterparts [1] [2]. The protective EPS matrix limits antibiotic penetration, creates heterogeneous microenvironments, and harbors metabolically dormant persister cells, making conventional therapies largely ineffective [1].

The escalating crisis of antibiotic resistance, causing an estimated 700,000 deaths annually, underscores the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies [1] [3]. The World Health Organization has emphasized the critical threat of resistant pathogens like carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which account for 13-74% of S. aureus infections worldwide [3]. Within this challenging landscape, CRISPR-Cas systems have emerged as revolutionary tools for precision antimicrobial therapy, offering targeted approaches to disrupt biofilm formation and resensitize resistant pathogens to conventional antibiotics [1] [3] [4].

Global Impact of Biofilm-Associated Infections

Table 1: Economic and Clinical Burden of Biofilm-Associated Resistance

| Area of Impact | Specific Context | Quantitative Burden |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Impact | Global agrifood sector (annual) | ~$324 billion [4] |

| U.S. foodborne illnesses (annual) | $17.6 billion [4] | |

| Average recall direct expenses | ~$10 million [4] | |

| Healthcare Impact | Annual global AMR deaths | 700,000 [1] |

| U.S. antibiotic-resistant infections (annual) | 2.8 million [3] | |

| U.S. AMR annual deaths | >35,000 [3] | |

| Biofilm Resistance | Increased antibiotic tolerance | Up to 1,000-fold [1] |

| Percentage of microbial infections | 60-80% [2] |

Efficacy of CRISPR-Based Interventions Against Biofilms

Table 2: Documented Efficacy of CRISPR-Based Anti-Biofilm Strategies

| CRISPR Intervention Strategy | Pathogen/Model System | Efficacy Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Liposomal Cas9 Formulations | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (in vitro) | >90% reduction in biofilm biomass [1] |

| Gold Nanoparticle Carriers | Multiple bacterial species | 3.5-fold increase in editing efficiency [1] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 targeting MCR-1 | E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae | Restored susceptibility to carbapenems [3] |

| CRISPRi targeting c-di-GMP | P. fluorescens SBW25 | Significant reduction in biofilm mass & altered architecture [5] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 targeting virulence | Acinetobacter baumannii Δcas3 | Significant reduction in biofilm formation & virulence [6] |

CRISPR-Based Mechanistic Approaches to Biofilm Control

Targeting Essential Biofilm Regulatory Pathways

The CRISPR-Cas system can be programmed to disrupt key genetic networks that control biofilm development:

- Quorum Sensing Disruption: Targeting autoinducer synthase genes (e.g., lasI, rhlI in Pseudomonas) to disrupt cell-to-cell communication essential for biofilm maturation [4].

- Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) Inhibition: Knocking out polysaccharide synthesis genes (e.g., pel, psl in Pseudomonas, ica in Staphylococcus) to prevent matrix formation [1] [4].

- Cyclic di-GMP Signaling Modulation: Targeting diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and phosphodiesterases (PDEs) to manipulate intracellular c-di-GMP levels, a central secondary messenger that governs the transition from motile to sessile lifestyles [5].

- Virulence Factor Silencing: Disrupting genes encoding adhesins, toxins, and secretion systems to reduce pathogenicity [3] [6].

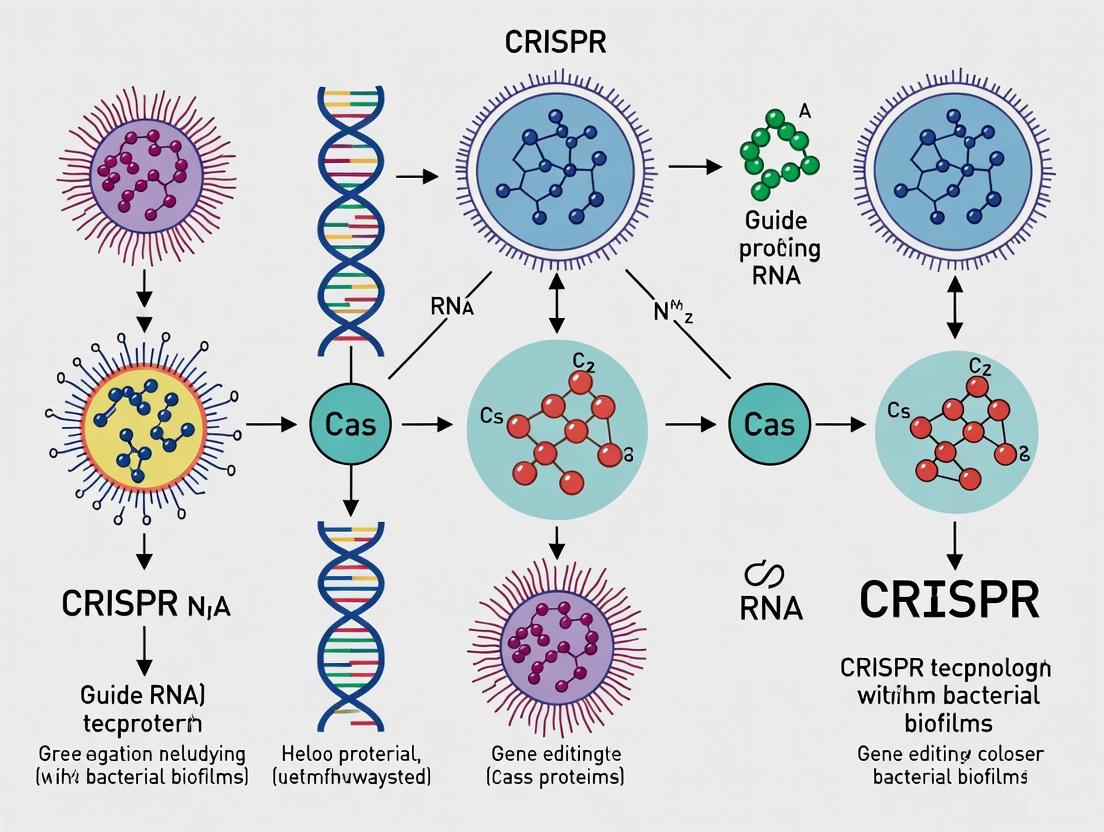

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of the CRISPR-Cas9 system and its application in targeting biofilm-related genes:

(CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism for Biofilm Gene Targeting)

Advanced CRISPR Toolbox for Biofilm Research

Beyond standard CRISPR-Cas9 knockout approaches, several specialized systems enable more precise biofilm manipulation:

- CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi): Utilizing catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressive domains for reversible gene silencing without permanent DNA damage [4] [5].

- CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa): Employing dCas9-activator fusions to enhance expression of biofilm-suppressing genes [4].

- Base and Prime Editing: Making precise single-nucleotide changes to study specific residues in biofilm regulatory proteins without creating double-strand breaks [3].

- Multiplexed Genome Engineering: Simultaneously targeting multiple biofilm-related genes using arrays of guide RNAs [7].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPRi-Mediated Biofilm Gene Silencing in Pseudomonas fluorescens

Application: This protocol enables reversible gene silencing to study essential biofilm genes without creating irreversible knockouts, adapted from [5].

Materials:

- Bacterial strains of interest

- Two compatible plasmids: dCas9 expression vector and gRNA expression vector

- anhydrotetracycline (aTc) for induction

- Biofilm culture vessels (e.g., 96-well plates, flow cells)

- Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) system

Procedure:

sgRNA Design: Design 20-nt guide sequences targeting the promoter or 5' coding region of your biofilm gene of interest. For transcription initiation blockade, target the -35 to +1 region relative to transcription start site.

Plasmid Construction:

- Clone sgRNA into expression plasmid with constitutive promoter

- Transform dCas9 and sgRNA plasmids sequentially into target strain

- Verify constructs by sequencing

Induction Conditions:

- Grow overnight cultures with appropriate antibiotics

- Dilute 1:100 in fresh medium with 0-200 ng/mL aTc inducer

- Incubate with shaking at optimal growth temperature

Biofilm Phenotyping:

- For quantitative assessment: Use 96-well plate crystal violet assay

- For structural analysis: Grow biofilms in flow cells for CLSM

- Image 24-72 hour biofilms using appropriate stains (SYTO9 for cells, dextran-conjugates for EPS)

Validation:

- Quantify mRNA reduction via RT-qPCR

- Confirm protein level reduction if antibodies available

- Correlate knockdown efficiency with biofilm phenotype strength

Troubleshooting:

- High basal dCas9 activity: Titrate aTc concentration downward

- Weak phenotype: Test multiple sgRNAs targeting different regions

- Structural defects: Use CLSM to characterize 3D architecture changes

Protocol 2: Nanoparticle-Mediated CRISPR Delivery for Biofilm Eradication

Application: Overcoming limited penetration of CRISPR components through dense biofilm matrices using nanoparticle carriers, adapted from [1].

Materials:

- Cas9 protein or expression plasmid

- sgRNA targeting biofilm-specific resistance genes

- Liposomal or gold nanoparticle formulations

- Mature biofilms grown in relevant model systems

- Appropriate antibiotics for synergy testing

Procedure:

Nanoparticle Formulation:

- For liposomal preparations: Mix Cas9-sgRNA RNP complexes with lipid mixtures using thin-film hydration or ethanol injection methods

- For gold nanoparticles: Conjugate RNP complexes via thiol chemistry

- Characterize size distribution (DLR or NTA) and encapsulation efficiency

Biofilm Treatment:

- Grow 24-72 hour mature biofilms in relevant medium

- Apply nanoparticle formulations at optimized concentrations

- Include controls: free CRISPR, nanoparticles alone, untreated

- Incubate for 4-24 hours depending on biofilm maturity

Efficacy Assessment:

- Quantify biofilm biomass via crystal violet staining

- Assess viability by colony forming units (CFU) counts

- Evaluate structural disruption by scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

- Test antibiotic resensitization by combining with sub-MIC antibiotics

Optimization:

- Test different nanoparticle surface modifications for enhanced penetration

- Optimize charge characteristics for EPS interaction

- Consider stimuli-responsive release (pH, enzyme-triggered)

Validation Metrics:

- ≥80% reduction in biofilm biomass compared to control

- 2-4 log reduction in viable counts

- 3.5-fold improvement in editing efficiency over non-carrier systems

- Restored antibiotic susceptibility demonstrated by reduced MIC values

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Based Biofilm Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | SpCas9, dCas9, Cas12a, Cas13 | DNA/RNA targeting for gene knockout, knockdown, or editing [7] |

| Delivery Systems | Liposomal nanoparticles, Gold nanoparticles, Bacteriophages | Enhanced delivery through biofilm matrix [1] [8] |

| Biofilm Assay Kits | Crystal violet, ATP bioluminescence, Live/Dead staining | Biofilm quantification and viability assessment [2] |

| Imaging Tools | Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM), Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | 3D structural analysis of biofilm architecture [2] [5] |

| Vector Systems | dCas9 expression plasmids, gRNA cloning vectors, Reporter constructs | CRISPR component expression and tracking [5] [9] |

Integrated Workflow for CRISPR-Based Biofilm Analysis

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental workflow for applying CRISPR technologies to study biofilm-related genes:

(Comprehensive Workflow for CRISPR-Biofilm Research)

The integration of CRISPR-based technologies with traditional antimicrobial approaches represents a paradigm shift in combating biofilm-associated infections. The precision offered by these systems enables targeted disruption of resistance mechanisms while potentially preserving the natural microbiome—a significant advantage over broad-spectrum antibiotics [1] [4]. Current research demonstrates remarkable efficacy, with liposomal Cas9 formulations achieving over 90% reduction in P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass and nanoparticle carriers enhancing editing efficiency 3.5-fold [1].

Future directions include the development of smart delivery systems with enhanced biofilm-penetrating capabilities, integration of CRISPR diagnostics for rapid pathogen detection, and combination therapies that leverage synergy between genetic editing and conventional antibiotics [4] [8]. The recent success of lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery in clinical trials for genetic diseases suggests potential translation pathways for biofilm-targeted CRISPR therapies [8]. However, challenges remain in optimizing delivery efficiency, minimizing off-target effects, and navigating regulatory pathways for these innovative approaches [1] [3] [4].

As the field advances, the convergence of CRISPR technologies with artificial intelligence for target prediction and nanoparticle engineering for precision delivery will likely yield increasingly sophisticated anti-biofilm strategies, potentially revolutionizing our approach to some of the most challenging infections in clinical practice.

Biofilm-associated infections represent a significant hurdle in modern medicine, contributing substantially to persistent chronic infections and the global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis. Biofilms are structured microbial communities embedded in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) that adheres to biological or inert surfaces [1] [10]. This architectural complexity confers remarkable resistance to conventional antibiotics, with biofilm-embedded bacteria exhibiting up to 1,000-fold greater tolerance compared to their planktonic counterparts [1]. The resilience of biofilms stems from an integrated multilayer defense system combining physical diffusion barriers, metabolic heterogeneity, and sophisticated cell-to-cell communication networks. Understanding this intricate architecture is paramount for developing advanced therapeutic strategies, including those leveraging CRISPR-based precision technologies [10].

Structural and Ultrastructural Organization of Biofilms

Biofilm formation follows a developmental cascade beginning with initial surface attachment and culminating in complex three-dimensional communities. The process initiates when planktonic bacteria reversibly attach to conditioned surfaces, followed by irreversible adhesion mediated by surface adhesins and pili [1] [10]. Attached cells then proliferate into microcolonies and begin synthesizing the extracellular matrix that defines the biofilm phenotype. The final maturation stage involves development of a complex architectural structure with characteristic water channels that facilitate nutrient distribution and waste removal [1]. The cycle completes with active dispersal of planktonic cells from the biofilm to colonize new niches [10].

The biofilm matrix is a composite material primarily consisting of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (eDNA) [10]. This matrix is not merely a passive scaffold but a dynamic functional component that provides structural stability, mediates adhesion to surfaces, and retains water to prevent desiccation [1]. At the ultrastructural level, biofilms display remarkable heterogeneity, with stratified organization into basal layers of densely packed cells firmly anchored to the substrate, and upper layers exhibiting more heterogeneous distribution of cells within the EPS matrix [1]. Advanced imaging techniques like confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) have revealed this architectural complexity, showing variations in bacterial density, matrix composition, and void spaces across the biofilm depth [1].

Diagram: Biofilm Developmental Cycle and Key Resistance Mechanisms

Physiological Barriers to Antimicrobial Penetration and Efficacy

The therapeutic recalcitrance of biofilms emerges from interconnected physiological mechanisms that collectively undermine antimicrobial efficacy:

Matrix-Imposed Diffusion Limitation: The anionic EPS matrix acts as a molecular sieve, physically restricting antibiotic penetration through charge-based interactions and molecular binding. This filtration effect creates concentration gradients that prevent adequate drug accumulation in the deeper biofilm layers [1] [10].

Metabolic Heterogeneity and Persister Cells: Biofilms develop microscale gradients of nutrients, oxygen, and metabolic waste products, resulting in heterogeneous metabolic activity throughout the structure. Subpopulations of bacteria, particularly in the deeper layers, enter a slow-growing or dormant state characterized by reduced metabolic activity. These persister cells are tolerant to conventional antibiotics that typically target active cellular processes, enabling biofilm regeneration after antibiotic pressure is removed [10].

Enhanced Horizontal Gene Transfer: The dense aggregation of bacterial cells within the EPS matrix facilitates efficient intercellular transfer of mobile genetic elements, including plasmids and transposons carrying antibiotic resistance genes. This proximity significantly accelerates the dissemination of resistance determinants throughout the microbial community [1] [10].

Adaptive Stress Responses: Biofilm-embedded bacteria exhibit upregulated expression of efflux pumps and other stress response systems that enhance their ability to expel or neutralize antimicrobial compounds. These adaptive responses are further modulated by cell-cell communication systems [1].

CRISPR-Based Approaches for Biofilm Functional Analysis

The emergence of CRISPR-Cas systems has revolutionized our ability to dissect the genetic determinants underlying biofilm formation and resistance. Both nuclease-active Cas9 for targeted gene knockout and catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) for gene modulation (CRISPRi/CRISPRa) enable precise functional genomics in diverse bacterial pathogens [4] [5].

CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) for Targeted Gene Silencing

CRISPRi employs dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressors to achieve reversible, tunable gene silencing without permanent genetic alteration. This approach is particularly valuable for studying essential genes and regulatory networks controlling biofilm development [4] [5].

Protocol: CRISPRi-Mediated Biofilm Gene Silencing in Pseudomonas fluorescens [5]

Step 1: CRISPRi Plasmid System Construction

- Utilize a two-plasmid system with compatible replication origins and selection markers.

- Plasmid 1: Expresses dCas9 under the control of an inducible promoter (e.g., PtetA induced by anhydrotetracycline, aTc).

- Plasmid 2: Constitutively expresses gene-specific guide RNA (gRNA) targeting the promoter or coding region of biofilm-related genes.

Step 2: gRNA Design and Validation

- Design gRNAs complementary to the non-template strand targeting regions within 50 base pairs downstream of the transcription start site for optimal repression.

- For genes involved in c-di-GMP signaling (e.g., GacA/S two-component system), design multiple gRNAs and validate silencing efficiency via qRT-PCR.

Step 3: Bacterial Transformation and Induction

- Introduce both plasmids into target bacterial strain via electroporation or conjugation.

- Culture transformants in medium containing appropriate antibiotics and induce dCas9 expression with aTc (e.g., 100 ng/mL).

Step 4: Phenotypic Assessment of Biofilm Formation

- Biomass Quantification: Perform crystal violet staining after 24-48 hours of biofilm growth. Measure solubilized dye absorbance at 570 nm.

- Architectural Analysis: Use confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) of live-dead stained biofilms to assess 3D structure and viability.

- Motility Assays: Evaluate swarming and swimming motility on semi-solid agar to assess impact on virulence-related behaviors.

Quantitative Data on CRISPR Efficacy Against Biofilm Formation

Table 1: Efficacy of CRISPR-Based Interventions Against Biofilm Formation

| Target Pathway | CRISPR System | Target Bacteria | Efficacy Metric | Quantitative Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quorum Sensing & EPS Production | CRISPRi (dCas9) | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Biofilm biomass reduction | >70% reduction compared to control | [5] |

| Antibiotic Resistance Genes | CRISPR-Cas9 | Escherichia coli | Re-sensitization to antibiotics | 3.5-fold increase in antibiotic efficacy | [1] |

| Biofilm Matrix Genes | Liposomal CRISPR-Cas9 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Biofilm biomass reduction | >90% reduction in vitro | [1] |

| c-di-GMP Regulatory Genes | CRISPRi (dCas9) | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Swarming motility inhibition | Significant impairment in swarm expansion | [5] |

CRISPR-Enhanced Nanoparticle Delivery Systems

A significant challenge in therapeutic CRISPR application is efficient delivery through the biofilm matrix. Nanoparticle (NP)-based carriers have emerged as promising vehicles that enhance stability, penetration, and targeted delivery of CRISPR components [1].

Step 1: Cas9-sgRNA Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Preparation

- Formulate RNP complexes by incubating purified Cas9 protein with synthetic sgRNA targeting essential biofilm genes (e.g., quorum sensing regulators, antibiotic resistance genes) at a 1:2 molar ratio for 15 minutes at room temperature.

Step 2: Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Encapsulation

- Prepare lipid mixture of ionizable cationic lipid, phospholipid, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid in ethanol at specific molar ratios.

- Mix aqueous RNP solution with lipid solution using microfluidic device to form uniform LNPs.

- Dialyze LNP formulation against PBS to remove ethanol and concentrate using centrifugal filters.

Step 3: Characterization and Quality Control

- Determine particle size and polydispersity index via dynamic light scattering (target diameter: 80-120 nm).

- Measure zeta potential to confirm surface charge.

- Quantify encapsulation efficiency using RiboGreen assay.

Step 4: Application and Efficacy Assessment

- Apply LNP-formulated RNP complexes to pre-established biofilms and quantify biomass reduction via crystal violet staining.

- Assess bacterial viability through colony-forming unit (CFU) counts and live-dead staining.

- Visualize biofilm structural integrity using scanning electron microscopy.

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Biofilm Studies

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Mediated Biofilm Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Systems | dCas9 for CRISPRi, Cas9 nuclease, Cas12a | Targeted gene knockout or transcriptional modulation in biofilm-forming bacteria | Catalytically dead dCas9 enables reversible gene silencing without DNA cleavage | [4] [5] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lipid nanoparticles, Gold nanoparticles, Bacteriophages | Enhance delivery of CRISPR components through protective biofilm matrix | Gold nanoparticles shown to increase editing efficiency by 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems | [1] |

| Biofilm Assay Kits | Crystal violet staining kits, Live-dead viability kits, EPS extraction kits | Quantify total biomass, assess viability distribution, analyze matrix composition | Crystal violet measures total biomass but cannot distinguish between live and dead cells | [11] |

| Molecular Tools | sgRNA synthesis kits, Plasmid vectors with inducible promoters, qRT-PCR reagents | Construct CRISPR systems and validate gene expression changes | Inducible promoters enable temporal control of CRISPR system activity | [5] |

| Imaging Reagents | CLSM-compatible stains, SEM preparation kits, Fluorescent protein reporters | Visualize 3D biofilm architecture and spatial gene expression patterns | CLSM enables non-destructive imaging of biofilm depth and structure | [1] [5] |

Diagram: CRISPR-Nanoparticle Synergy in Biofilm Eradication

The structural and physiological barriers posed by biofilm architecture represent a formidable challenge in clinical management of persistent infections. The integration of CRISPR-based technologies provides unprecedented precision in dissecting and targeting the genetic foundations of biofilm-mediated resistance. When combined with advanced delivery platforms like engineered nanoparticles, CRISPR systems can effectively penetrate the biofilm matrix and disrupt key resistance mechanisms. As these technologies continue to evolve, they hold exceptional promise for developing next-generation anti-biofilm strategies that transcend the limitations of conventional antibiotics, potentially revolutionizing the treatment of chronic infections in the post-antibiotic era.

CRISPR-Cas systems represent a remarkable evolutionary adaptation in prokaryotes, originating as adaptive immune mechanisms that protect bacteria and archaea from viral infections and other invasive genetic elements. These systems consist of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins that provide sequence-specific defense through a molecular memory of past infections [12]. The fundamental mechanism involves three distinct stages: adaptation, where new spacers are acquired from foreign DNA; expression, where CRISPR arrays are transcribed and processed into CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs); and interference, where crRNA-guided Cas complexes identify and cleave complementary nucleic acids [12]. This sophisticated immune system has been identified in approximately 40% of sequenced bacteria and over 80% of archaea, demonstrating its widespread biological significance [12].

The transformative potential of CRISPR-Cas systems was realized when researchers repurposed the Type II CRISPR-Cas9 system from Streptococcus into a programmable gene-editing tool, creating a two-component system comprising the Cas9 enzyme and a synthetic single-guide RNA [12]. This breakthrough initiated a new era in genetic engineering, enabling precise genome manipulation across diverse organisms and cell types. The subsequent discovery and adaptation of additional Cas enzymes, including Cas12 (Type V) for DNA editing and Cas13 (Type VI) for RNA targeting, further expanded the CRISPR toolkit beyond simple DNA cleavage [12]. This evolution from bacterial immunity to programmable gene editing has revolutionized biological research, therapeutic development, and biotechnology applications.

Application Notes: CRISPR-Based Biofilm Research

Quantitative Analysis of CRISPR Applications in Biofilm Disruption

Table 1: Efficacy of CRISPR-Based Approaches Against Bacterial Biofilms

| Application Approach | Target System | Reported Efficacy | Delivery Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 with nanoparticle delivery | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | >90% reduction in biofilm biomass [1] | Liposomal nanoparticles | Enhanced cellular uptake and controlled release within biofilm environments |

| CRISPR-Cas9 with gold nanoparticles | Various biofilm-forming bacteria | 3.5-fold increase in editing efficiency [1] | Gold nanoparticle carriers | Superior biofilm penetration and synergistic action with antibiotics |

| CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Effective gene silencing confirmed [5] | Plasmid-based dCas9 | Reliable phenotyping of complex traits including swarming motility and biofilm formation |

| CRISPR-based antimicrobials | Foodborne pathogens | ~3-log reduction of target pathogens [4] | Engineered phages or nanoparticles | Programmable, sequence-specific suppression of pathogens and resistance genes |

Key Signaling Pathways in Biofilm Formation

The development of bacterial biofilms is regulated through sophisticated signaling pathways that control the transition from motile to sessile lifestyles. Two primary regulatory systems govern this process: the GacA/S two-component system and cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) signaling networks [5]. The GacA/S system comprises a membrane-bound sensor histidine kinase (GacS) and its cognate response regulator (GacA) that coordinates genetic programs in response to environmental stimuli [5]. This system regulates approximately 700 genes involved in diverse functions including biofilm formation, oxidative stress response, and secondary metabolite production through the Gac/Rsm signaling cascade involving non-coding small regulatory RNAs RsmZ and RsmY [5].

Simultaneously, c-di-GMP serves as a near-universal intracellular signaling messenger that regulates bacterial motility, virulence, and the transition to biofilm formation [5]. Intracellular c-di-GMP levels are modulated through the balanced activities of diguanylate cyclases (DGCs), which synthesize c-di-GMP from GTP, and phosphodiesterases (PDEs), which break down c-di-GMP [5]. Elevated intracellular concentrations of c-di-GMP correlate with increased propensity for biofilm formation, influencing multiple stages of biofilm development from initial cell adhesion to matrix production and eventual dispersion [5].

Diagram 1: Signaling pathways regulating bacterial biofilm formation. The GacA/S two-component system and c-di-GMP signaling network integrate environmental cues to control biofilm development through regulation of EPS production and bacterial lifestyle transitions.

Advanced CRISPR Tools for Biofilm Research

The expanding CRISPR toolkit now includes several specialized technologies for biofilm research. CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) utilizes a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) to block transcription initiation or elongation without altering DNA sequence, enabling reversible gene silencing essential for studying essential biofilm genes [4] [5]. Conversely, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) employs modified dCas9 complexes to enhance gene transcription, facilitating gain-of-function studies [4]. More recently, CRISPR-based diagnostics platforms including SHERLOCK (Cas13-based) and DETECTR (Cas12-based) exploit collateral cleavage activity to achieve attomolar sensitivity for detecting biofilm-forming pathogens [4]. These tools provide unprecedented precision for dissecting biofilm regulatory networks and developing targeted interventions.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: CRISPRi-Mediated Gene Silencing in Pseudomonas fluorescens for Biofilm Analysis

Principle

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) enables targeted gene silencing without permanent genetic modifications through the action of a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) that sterically hinders transcription when directed to specific genomic locations by guide RNAs [5]. This protocol describes the application of CRISPRi to investigate genes controlling biofilm formation in P. fluorescens, a model organism for studying complex bacterial phenotypes including cell morphology, motility, and biofilm architecture [5].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPRi Biofilm Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi Plasmid System | dCas9 expression plasmid (PtetA promoter), gRNA expression plasmid [5] | Provides inducible dCas9 and target-specific gRNA | Use compatible plasmids with appropriate antibiotic resistance |

| Inducer | Anhydrotetracycline (aTc) [5] | Induces dCas9 expression from PtetA promoter | Dose-dependent response; optimize for each strain |

| Bacterial Strains | P. fluorescens SBW25, WH6, Pf0-1 [5] | Model organisms for biofilm research | Chromosomal reporter constructs recommended for validation |

| Imaging & Analysis | Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) [1] | High-resolution biofilm architecture analysis | Enables quantification of biomass, thickness, and EPS distribution |

| Delivery Vehicles | Liposomal nanoparticles, Gold nanoparticles [1] | Enhances CRISPR component delivery | Improves biofilm penetration and editing efficiency |

Procedure

Step 1: gRNA Design and Validation

- Design gRNAs targeting either the template (T) or non-template (NT) DNA strand of the promoter region or early coding sequence of target genes [5].

- For transcription initiation blockade: Design gRNAs complementary to regions within 50 bp downstream of the transcription start site [5].

- For transcription elongation blockade: Design gRNAs targeting sites overlapping the start of the open reading frame [5].

- Validate gRNA specificity using appropriate bioinformatics tools to minimize off-target effects.

Step 2: Plasmid Construction

- Clone the selected gRNA sequence into the gRNA expression plasmid under a constitutive promoter [5].

- Transform both dCas9 expression plasmid and gRNA plasmid into the target P. fluorescens strain using standard electroporation or chemical transformation methods [5].

- Select transformants using appropriate antibiotics and verify plasmid incorporation through colony PCR and sequencing.

Step 3: Induction of Gene Silencing

- Inoculate transformed bacteria in appropriate liquid medium and grow to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5).

- Add anhydrotetracycline (aTc) inducer to a final concentration of 100 ng/mL (optimize concentration based on experimental conditions) [5].

- Incubate for 6-24 hours to allow dCas9 expression and target gene silencing.

Step 4: Biofilm Formation Assay

- Transfer induced cultures to biofilm-compatible surfaces (e.g., glass coverslips, microtiter plates, flow cells).

- Allow biofilms to develop for 24-72 hours under conditions appropriate for the specific P. fluorescens strain being studied.

- For architectural analysis, use confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) to image biofilms at various time points [1].

Step 5: Phenotypic Analysis

- Quantify biofilm biomass using crystal violet staining or direct microscopic measurement.

- Analyze biofilm architecture using COMSTAT or similar software for CLSM image analysis.

- Assess related phenotypes including swarming motility, EPS production, and cellular morphology [5].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for CRISPRi-mediated analysis of biofilm formation. The protocol progresses from genetic construct preparation through bacterial transformation, induction of gene silencing, biofilm development, and quantitative phenotypic analysis.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

- Low silencing efficiency: Optimize aTc concentration (test range: 50-200 ng/mL); verify gRNA binding site accessibility; check dCas9 expression levels [5].

- Variable phenotypes between replicates: Standardize growth conditions; ensure consistent induction timing; use freshly prepared aTc stock solutions.

- Poor biofilm formation: Verify nutrient composition; optimize surface material; control environmental conditions (temperature, humidity).

- High basal silencing without inducer: Use lower-copy-number plasmids; include tighter regulatory elements; reduce basal dCas9 expression [5].

Protocol: Nanoparticle-Mediated CRISPR Delivery for Biofilm Eradication

Principle

Nanoparticles enhance the delivery of CRISPR components to bacterial cells within biofilms by improving cellular uptake, protecting genetic material from degradation, and facilitating penetration through the extracellular polymeric matrix [1]. This protocol describes the formulation of CRISPR-functionalized nanoparticles and their application for targeted biofilm disruption.

Procedure

Step 1: Nanoparticle Formulation

- For liposomal nanoparticles: Prepare lipid film using DOTAP, DOPE, and cholesterol in molar ratio 1:0.7:0.3 [1].

- Hydrate lipid film with CRISPR-Cas9 components (purified Cas9 protein and sgRNA complex or encoding plasmids) in appropriate buffer.

- Size reduction through extrusion or sonication to achieve particles of 100-200 nm diameter.

- For gold nanoparticles: Functionalize citrate-capped AuNPs (15-20 nm) with thiolated oligonucleotides and CRISPR complexes [1].

Step 2: Biofilm Treatment and Assessment

- Apply nanoparticle formulations to pre-established biofilms (24-48 hours old) at multiplicities of infection (MOI) optimized for the specific system.

- Incubate for 4-24 hours to allow penetration and editing.

- Assess biofilm reduction through biomass staining, viability counts, and microscopy.

- Quantify gene editing efficiency through PCR-based methods or sequencing.

CRISPR-Cas systems have undergone a remarkable transformation from fundamental bacterial immune mechanisms to versatile tools for precision biofilm research and intervention. The integration of CRISPR technologies with advanced delivery systems such as nanoparticles has created powerful platforms for dissecting the complex regulatory networks that control biofilm formation and for developing targeted approaches to combat biofilm-associated challenges [1] [4]. The ongoing discovery of novel Cas variants including CasΦ and CasX/Cas12f, coupled with precision editing technologies like base editing and prime editing, continues to expand the CRISPR toolbox for biofilm research [13].

Future developments in CRISPR-based biofilm control will likely focus on enhancing delivery efficiency through engineered nanoparticles with improved biofilm penetration capabilities, developing multiplexed approaches that simultaneously target multiple genetic pathways, and creating integrated systems that combine CRISPR-mediated gene editing with conventional antimicrobial strategies [1] [4]. Furthermore, the convergence of CRISPR technologies with artificial intelligence for predictive modeling of optimal gene targets and guide RNA designs represents a promising frontier for precision biofilm control [4]. As these technologies mature, they hold significant potential for addressing the persistent challenges posed by bacterial biofilms in clinical, industrial, and environmental settings.

Bacterial biofilms represent a significant challenge in clinical and industrial settings due to their inherent resistance to antimicrobial treatments and immune responses. The architecture and resilience of biofilms are governed by complex genetic networks that regulate key processes such as quorum sensing (QS), extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) production, and stress response [14]. The emergence of CRISPR technology has revolutionized functional genomics, providing researchers with precise tools to interrogate these biofilm-regulating genes. This Application Note details protocols for using CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) to investigate the genetic determinants of biofilm formation, offering methodologies for gene silencing, phenotypic analysis, and mechanistic studies. The guidance is framed within a broader research context focused on leveraging CRISPR-based approaches for antibacterial drug development and biofilm control strategies.

Key Genetic Determinants of Biofilm Formation

The transition from planktonic to sessile biofilm lifestyle is coordinated by specific genetic systems. Understanding these systems is crucial for designing targeted CRISPR-based studies.

Quorum Sensing (QS) Genes

Quorum sensing is a cell-density dependent communication system that coordinates collective behaviors, including biofilm formation. Key QS genes serve as prime targets for CRISPRi silencing studies.

- LuxR/LuxI-type systems: These acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL)-based systems are prevalent in Gram-negative bacteria. Silencing the synthase (e.g., lasI, rhlI) or receptor (e.g., lasR, rhlR) genes disrupts the production of signal molecules and the expression of virulence and biofilm genes [15].

- Accessory regulator genes: Genes such as gacA and gacS, which form a two-component system, regulate the QS cascade and control the expression of downstream biofilm-related operons. In Pseudomonas fluorescens, CRISPRi-mediated silencing of the gacA/S system produces clear swarming and biofilm phenotypes [5].

Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) Production Genes

The EPS matrix forms the structural backbone of the biofilm, providing mechanical stability and protection. Its production is regulated by complex genetic networks.

- Polysaccharide biosynthesis operons: These include genes for the synthesis of polysaccharides like alginate, cellulose, and Pel. For example, the PFLU1114 operon in P. fluorescens SBW25 has been shown to powerfully inhibit biofilm formation when disrupted [5].

- c-di-GMP regulatory network genes: The intracellular secondary messenger cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) is a central regulator of the motile-sessile switch. Genes encoding diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) with GGDEF domains (e.g., gcbA) synthesize c-di-GMP, promoting biofilm formation. Conversely, genes encoding phosphodiesterases (PDEs) with EAL or HD-GYP domains (e.g., bifA, dipA) degrade c-di-GMP, promoting dispersal [5]. CRISPRi silencing allows for the specific functional analysis of these numerous and often redundant enzymes.

Stress Response Genes

Biofilm environments create heterogeneous microenvironments with nutrient and oxygen gradients, necessitating robust stress response pathways.

- General stress response regulators: Genes like rpoS (encoding the sigma factor σ^S^) control the expression of a large regulon in response to starvation, oxidative, and osmotic stress, enhancing the survival of biofilm-embedded cells.

- Persister cell formation genes: Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems (e.g., hipA, relBE) are implicated in the formation of dormant, highly tolerant persister cells within biofilms. Targeting these genes with CRISPRi can help elucidate mechanisms of recalcitrance to antibiotic treatment.

Table 1: Key Biofilm-Regulating Gene Targets for CRISPR-Based Studies

| Gene Category | Example Genes | Function | Phenotype upon Silencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quorum Sensing | gacA, gacS, lasI, lasR | Two-component system; AHL synthase/receptor [5] [15] | Disrupted cell-cell signaling, reduced virulence factor production, impaired biofilm maturation |

| EPS Production | alg44, PFLU1114 operon | Alginate copolymerase; putative EPS biosynthesis [5] | Altered biofilm architecture, reduced biomass, increased susceptibility to antimicrobials |

| c-di-GMP Metabolism | DGCs (e.g., gcbA), PDEs (e.g., bifA, dipA) | Synthesis and degradation of c-di-GMP [5] | Altered motility, defective initial attachment, or impaired biofilm dispersion |

CRISPRi Experimental Protocol for Biofilm Gene Silencing

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing a CRISPRi system to study biofilm genes in a model bacterium like Pseudomonas fluorescens, based on the system adapted by [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for establishing the CRISPRi system.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPRi Biofilm Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Plasmid | Constitutively or inducibly expresses catalytically "dead" Cas9 (dCas9), which binds DNA without cutting it. | Plasmid with PtetA promoter driving dCas9 expression, origin of replication for Pseudomonas [5]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) Expression Plasmid | Constitutively expresses the target-specific gRNA. Contains a scaffold sequence that binds dCas9. | Compatible plasmid with constitutive promoter (e.g., P~J~23119), target-specific 20nt spacer sequence [5]. |

| Electrocompetent Cells | Bacterial cells prepared for transformation via electroporation. | P. fluorescens strain (e.g., SBW25, WH6, Pf0-1) made electrocompetent [5]. |

| Inducer Molecule | Chemical to induce dCas9 expression in inducible systems. | Anhydrotetracycline (aTc), used at optimized concentrations (e.g., 100 ng/mL) [5]. |

| Biofilm Growth Media | Culture medium supporting robust biofilm formation. | Standard Lysogeny Broth (LB) or specific minimal media; 96-well polystyrene plates for microtiter assays. |

Protocol Workflow

The following diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow for a CRISPRi biofilm study.

Step 1: gRNA Design and Plasmid Construction

- Target Selection: Identify the 20-nucleotide DNA sequence immediately 5' to a 5'-NGG-3' Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) within the promoter or coding region of your target gene. For maximal silencing, design gRNAs to target the non-template (NT) strand within the promoter or the early coding region to block transcription initiation or elongation, respectively [5].

- Plasmid Assembly: Synthesize and clone the spacer oligonucleotide into the BsaI site of the gRNA expression plasmid. Verify the sequence of the final construct by Sanger sequencing.

Step 2: Transformation

- Co-transform the verified gRNA plasmid and the dCas9 expression plasmid into electrocompetent P. fluorescens cells via electroporation.

- Plate the transformation mixture on selective media containing the appropriate antibiotics for both plasmids. Incubate at 28-30°C for 24-48 hours until colonies appear.

Step 3: Gene Silencing Induction

- Inoculate a single colony into liquid media with antibiotics and the inducer (e.g., 100 ng/mL aTc). Incubate with shaking for 16-24 hours.

- For biofilm assays, dilute the induced culture to an OD~600~ of ~0.05 in fresh media with inducer and antibiotics.

Step 4: Biofilm Phenotypic Assessment

Crystal Violet Biofilm Assay [5]:

- Transfer 150 µL of diluted culture to wells of a 96-well polystyrene plate. Include controls (non-targeting gRNA, no gRNA).

- Incubate statically for 24-48 hours at 30°C.

- Carefully remove planktonic cells and rinse the biofilm with water.

- Stain the adherent biofilm with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes.

- Rinse thoroughly and solubilize the bound dye with 30% acetic acid.

- Measure the absorbance at 550 nm to quantify total biofilm biomass.

Swarming Motility Assay:

- Prepare 0.3-0.5% agar plates containing appropriate media, antibiotics, and inducer.

- Spot 2-3 µL of induced culture in the center of the agar surface.

- Incubate the plates right-side up for 16-24 hours.

- Measure the diameter of the swarming colony to quantify motility, which is often inversely correlated with biofilm formation.

Step 5: Biofilm Architecture Imaging

- Grow biofilms on a suitable surface (e.g., glass coverslip) placed in a culture well.

- Stain the mature biofilm with fluorescent dyes (e.g., SYTO 9 for cells, Concanavalin A-Texas Red for polysaccharides).

- Image the biofilm using a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM). Acquire Z-stacks at multiple random locations.

- Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, COMSTAT) to quantify architectural parameters such as biomass volume, average thickness, and substratum coverage [5].

Step 6: Data Analysis and Validation

- Statistical Analysis: Perform triplicate biological repeats. Use Student's t-test or ANOVA to determine the statistical significance of phenotypic differences between the target-gRNA strain and control strains.

- Validation: Confirm gene knockdown efficiency by quantifying mRNA levels using reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR).

Signaling Pathway and Genetic Network Analysis

The genes regulating biofilm formation do not operate in isolation but are part of an integrated signaling network. The following diagram synthesizes the key interactions between the quorum sensing, c-di-GMP, and EPS production systems.

Quantitative Data and Expected Outcomes

Successful implementation of the CRISPRi protocol should yield quantifiable changes in biofilm phenotypes and gene expression. The table below summarizes expected outcomes based on published studies.

Table 3: Expected Quantitative Outcomes from CRISPRi Silencing of Biofilm Genes

| Target Gene/Pathway | Assay Type | Control Value | Expected Outcome with CRISPRi | Reported Efficiency/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gacA/S (QS) | Swarming Motility | Swarm diameter: ~20 mm | >50% reduction in diameter [5] | CRISPRi phenocopied gene inactivation mutants [5] |

| PFLU1114 operon (EPS) | Biofilm Biomass (Crystal Violet) | OD~550~: ~2.0 | >70% reduction in OD~550~ [5] | Potent inhibition of biofilm formation observed [5] |

| Multiple c-di-GMP genes | Biofilm Architecture (CLSM) | Biomass: ~25 µm³/µm² | Variable (Increase or decrease\nbased on target) [5] | ~1/3 of mutants show strong phenotypes across conditions [5] |

| General | Gene Expression (qPCR) | 100% mRNA expression | 50-90% knockdown of target mRNA [5] | Efficiency depends on gRNA target location (promoter vs. coding) [5] |

Bacterial biofilms are structured communities of microorganisms embedded in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix, which confers inherent resistance to conventional antimicrobial treatments [1]. The complex architecture of biofilms limits antibiotic penetration and creates heterogeneous microenvironments, leading to persistent infections that are challenging to eradicate [1]. Understanding the genetic pathways controlling biofilm formation and maintenance is therefore crucial for developing effective anti-biofilm strategies. CRISPR-based technologies have emerged as powerful discovery tools for functional genomics, enabling researchers to systematically interrogate genes involved in biofilm formation pathways with unprecedented precision and scalability.

Traditional gene inactivation methods are often labor-intensive, limiting systematic genetic surveys in many bacterial hosts [5]. The adaptation of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for biofilm research has revolutionized this field by enabling reversible, sequence-specific gene silencing without permanent genetic alterations [5]. This approach utilizes a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) protein that binds to target DNA sequences under the guidance of a specific single-guide RNA (sgRNA), sterically hindering transcription initiation or elongation [16]. The precision of CRISPRi allows researchers to dissect complex genetic networks governing biofilm development, including quorum sensing pathways, cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) signaling systems, and EPS production mechanisms [5] [16].

Key Signaling Pathways in Biofilm Formation

Quorum Sensing and Biofilm Regulation

Quorum sensing (QS) represents a cell-density dependent chemical signaling mechanism that bacteria utilize to coordinate collective behaviors including biofilm formation and pathogenesis [16]. The luxS gene, which encodes a synthase involved in the production of Autoinducer-2 (AI-2), plays a pivotal role in guiding the initial stages of biofilm formation across numerous bacterial species [16]. CRISPRi-mediated silencing of luxS has been demonstrated to significantly inhibit biofilm formation in E. coli, confirming its essential function in QS-mediated biofilm development [16].

Cyclic di-GMP Signaling Network

The near-universal bacterial second messenger c-di-GMP represents a key signaling system that regulates the transition between motile and sessile lifestyles [5]. Intracellular c-di-GMP levels are modulated through the balanced activities of diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) containing GGDEF domains that synthesize c-di-GMP, and phosphodiesterases (PDEs) containing EAL or HD-GYP domains that break down c-di-GMP [5]. Elevated intracellular concentrations of c-di-GMP typically correlate with enhanced biofilm formation through the regulation of EPS production, flagellar function, and cell adhesion mechanisms [5]. Bacterial genomes often encode numerous proteins with c-di-GMP-binding signatures, creating a complex regulatory network that controls various stages of biofilm development from initial attachment to maturation and dispersion [5].

Two-Component Systems

Two-component systems (TCS) serve as fundamental environmental sensing mechanisms that translate external stimuli into coordinated cellular responses through regulated genetic programs [5]. In Pseudomonas species, the GacA/S two-component system regulates approximately 700 genes involved in diverse biological functions including biofilm formation, oxidative stress response, and secondary metabolite production [5]. This system consists of a membrane-bound sensor histidine kinase (GacS) and its cognate response regulator (GacA), which collectively influence EPS production through the Gac/Rsm signaling cascade involving non-coding small regulatory RNAs RsmZ and RsmY [5].

The following diagram illustrates the core CRISPRi mechanism for interrogating these biofilm formation pathways:

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR-Based Biofilm Analysis

CRISPRi System Design and Implementation

The following protocol outlines the implementation of a CRISPRi system for interrogating biofilm-related genes in diverse bacterial species, adapted from established methodologies in Pseudomonas fluorescens and E. coli [5] [16].

Materials Required:

- pdCas9 plasmid (constitutively or inducibly expresses dCas9)

- pgRNA plasmid backbone for sgRNA expression

- Target bacterial strain(s)

- Appropriate antibiotics for selection

- Inducer molecules (e.g., anhydrotetracycline/aTc for Ptet systems)

- Primers for sgRNA template cloning

- Molecular biology reagents for cloning and transformation

Procedure:

sgRNA Design and Cloning:

- Identify 20-nucleotide target sequences adjacent to PAM (NGG for S. pyogenes Cas9) sites within promoter regions or early coding sequences of target biofilm genes

- Synthesize complementary oligonucleotides containing the target sequence with appropriate overhangs for cloning into the pgRNA backbone

- Clone annealed oligonucleotides into the BsaI restriction site of the pgRNA plasmid using Golden Gate assembly

- Transform ligation products into E. Top 10 competent cells and select on appropriate antibiotic plates

- Verify successful cloning by colony PCR and Sanger sequencing using specific primers flanking the insertion site

Dual Plasmid Transformation:

- Co-transform the verified pgRNA construct (carrying biofilm gene-specific sgRNA) and pdCas9 plasmid into the target bacterial strain

- Select transformants on plates containing both antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin 100 μg/mL and chloramphenicol 25 μg/mL)

- Verify dual plasmid maintenance by replica plating and colony PCR

Induction of CRISPRi System:

- Inoculate single colonies of the knockdown strain in liquid medium with appropriate antibiotics

- Grow cultures to exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.4-0.6)

- Induce dCas9 expression with 2 μM anhydrotetracycline (aTc) or other appropriate inducer

- Continue incubation for 3-4 hours to allow gene silencing before downstream assays

Quantitative Assessment of Biofilm Phenotypes

Crystal Violet Biofilm Assay:

- Grow CRISPRi knockdown strains in appropriate media with inducer for 24-48 hours in static conditions

- Remove planktonic cells and gently wash adhered cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Fix biofilms with methanol or ethanol for 15 minutes

- Stain with 0.1% crystal violet solution for 15-20 minutes

- Wash extensively to remove unbound dye

- Elute bound dye with 33% acetic acid or ethanol-acetone mixture (80:20)

- Measure absorbance at 570-600 nm to quantify biofilm biomass [6] [16]

Metabolic Activity Assay (XTT Reduction):

- Prepare XTT-menadione solution fresh: 1 mg/mL XTT with 4 μM menadione in PBS

- Add XTT solution to biofilms and incubate in dark for 2-3 hours at 37°C

- Measure supernatant absorbance at 490 nm to assess metabolic activity of biofilm cells [16]

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM):

- Grow biofilms on appropriate surfaces (e.g., glass coverslips, flow cells)

- Stain with SYTO9 green fluorescent nucleic acid stain (emission: 498 nm) for bacterial cells

- Counterstain extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) matrix with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated dextran (emission: 668 nm) or other EPS-specific probes

- Image using appropriate laser settings and filter configurations

- Acquire z-stacks at regular intervals (e.g., 1 μm) through the entire biofilm depth

- Reconstruct 3D architecture and quantify biomass, thickness, and spatial distribution using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, COMSTAT) [6]

Gene Expression Validation:

- Extract total RNA from CRISPRi strains using Trizol method

- Treat with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination

- Synthesize cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random hexamers

- Perform quantitative RT-PCR with gene-specific primers

- Normalize expression to housekeeping genes (e.g., rpoB, gyrA)

- Calculate fold-change using comparative Ct method (2-ΔΔCt) [16]

The experimental workflow for implementing CRISPRi-based biofilm analysis is systematically outlined below:

Quantitative Data from CRISPR-Based Biofilm Studies

Table 1: Efficacy of CRISPRi in Targeting Biofilm-Associated Genes Across Bacterial Species

| Target Gene | Bacterial Species | Gene Function | CRISPRi Efficiency | Biofilm Reduction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| luxS | E. coli AK-117 | Quorum sensing (AI-2 synthesis) | ~70% gene expression knockdown | ~60% biomass reduction | [16] |

| GacA/S | P. fluorescens SBW25 | Two-component system regulator | Strong downregulation | Significant alteration in biofilm architecture | [5] |

| PFLU1114 operon | P. fluorescens SBW25 | Biofilm inhibition mediator | Effective silencing | Potent inhibition of biofilm formation | [5] |

| Genes encoding DGCs/PDEs | P. fluorescens SBW25 | c-di-GMP metabolism | Successful repression | Altered biofilm mass and structure | [5] |

| cas3 (Type I-Fa) | A. baumannii ATCC19606 | CRISPR-Cas system component | Gene knockout | Significant reduction in biofilm formation | [6] |

Table 2: Advanced Nanoparticle-Mediated CRISPR Delivery Systems for Enhanced Biofilm Penetration

| Nanoparticle Type | CRISPR Payload | Target Bacterium | Editing Efficiency | Biofilm Reduction | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomal nanoparticles | Cas9/sgRNA complexes | P. aeruginosa | High efficiency | >90% biofilm biomass reduction in vitro | Enhanced cellular uptake, controlled release [1] |

| Gold nanoparticles | CRISPR-Cas9 components | P. aeruginosa | 3.5-fold increase compared to non-carrier systems | Significant biofilm disruption | Improved target specificity, intrinsic antibacterial properties [1] |

| Hybrid nanoparticle systems | Cas9/sgRNA + antibiotics | Multi-drug resistant pathogens | Enhanced editing efficiency | Superior biofilm disruption | Synergistic antibacterial effects, co-delivery capability [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Based Biofilm Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes | Commercial Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| pdCas9 plasmids | Expresses catalytically inactive Cas9 protein | Available with inducible (Ptet) or constitutive promoters; includes antibiotic resistance markers | Addgene (#44249) |

| pgRNA backbone | sgRNA expression vector | Contains scaffold sequence compatible with S. pyogenes dCas9; ampicillin resistance | Addgene (#44251) |

| dCas9 protein | CRISPRi effector molecule | Can be used directly in ribonucleoprotein complexes for transient silencing | Commercial protein suppliers |

| Anhydrotetracycline (aTc) | Inducer for Ptet promoter systems | Typical working concentration: 2-100 nM; water-soluble | Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Fisher |

| SYTO9 green fluorescent stain | Bacterial cell staining for CLSM | Excitation/Emission: 483/498 nm; penetrates intact cell membranes | Thermo Fisher, Bio-Rad |

| Alexa Fluor 647-dextran | EPS matrix staining for CLSM | Excitation/Emission: 647/668 nm; labels extracellular polysaccharides | Thermo Fisher |

| XTT sodium salt | Metabolic activity assay in biofilms | Used with electron-coupling agent menadione; measures cellular respiration | Sigma-Aldrich, Abcam |

| Crystal violet | Biofilm biomass quantification | Stains cells and matrix components; requires solubilization for quantification | Standard laboratory suppliers |

Discussion and Technical Considerations

The application of CRISPR-based technologies for interrogating biofilm formation pathways presents both unprecedented opportunities and technical challenges that researchers must address for successful experimental outcomes.

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced Efficiency

The efficiency of CRISPRi-mediated gene silencing in biofilm studies is influenced by multiple factors including sgRNA design, target accessibility, and bacterial strain characteristics. For optimal results, sgRNAs should be designed to target the non-template DNA strand in promoter regions or early coding sequences, as this approach has demonstrated superior repression efficiency [5]. The positioning of sgRNAs targeting transcription initiation sites (e.g., Pc4 and Pc5 in P. fluorescens) has been shown to produce more effective gene silencing compared to those targeting elongation regions [5]. Additionally, researchers should note that dCas9 may exhibit basal expression even in the absence of induction, which can be mitigated through careful control of induction parameters and the use of inducible promoter systems with low background activity [5].

Advanced Delivery Mechanisms for Biofilm Penetration

A significant challenge in CRISPR-based biofilm research involves efficient delivery of CRISPR components through the protective EPS matrix. Nanoparticle-based delivery systems have emerged as promising solutions to this limitation, offering enhanced penetration and targeted release within biofilm environments [1]. Liposomal Cas9 formulations have demonstrated remarkable efficacy, reducing P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro [1]. Similarly, gold nanoparticle carriers have shown a 3.5-fold increase in editing efficiency compared to non-carrier systems, while also exhibiting intrinsic antibacterial properties that synergize with CRISPR-mediated genetic disruption [1]. These advanced delivery platforms can be further engineered for co-delivery of antibiotics or antimicrobial peptides alongside CRISPR components, creating multifaceted approaches that attack bacterial biofilms through both genetic and traditional antimicrobial mechanisms [1].

Interpretation of Phenotypic Outcomes

When employing CRISPRi for functional genomics in biofilm pathways, researchers should implement appropriate controls and validation methods to accurately interpret phenotypic outcomes. The inclusion of non-targeting sgRNA controls is essential to distinguish sequence-specific effects from non-specific responses to the CRISPRi system itself [5]. Additionally, complementation strains can help verify that observed phenotypes directly result from targeted gene silencing rather than off-target effects [6]. For comprehensive pathway analysis, researchers should consider implementing multiplexed sgRNA approaches to simultaneously target multiple components of biofilm regulatory networks, enabling the dissection of complex genetic interactions and functional redundancies within these systems [5].

The integration of CRISPR-based functional genomics with advanced analytical techniques such as confocal laser scanning microscopy, RNA sequencing, and proteomic profiling provides a powerful framework for elucidating the complex genetic pathways that control biofilm formation and maintenance. This multidisciplinary approach offers unprecedented insights into bacterial community behaviors and opens new avenues for developing targeted anti-biofilm strategies with translational potential in clinical, industrial, and environmental settings.

CRISPR Toolbox: From Functional Screening to Precision Antimicrobials

CRISPR Knockout Libraries for Genome-Wide Biofilm Gene Screening

CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko) screening represents a powerful high-throughput approach for functional genomics, enabling the systematic identification of genes essential for biofilm formation and regulation. This technology leverages the CRISPR-Cas9 system to generate permanent, targeted knockouts across the entire genome, allowing researchers to investigate genotype-phenotype relationships on an unprecedented scale [17]. In biofilm research, this is particularly valuable for unraveling the complex genetic networks that control bacterial adhesion, matrix production, community structure, and antibiotic tolerance [1] [18].

Compared to traditional genetic screening methods like RNA interference (RNAi), CRISPRko screening offers significantly higher specificity, more efficient gene knockout, and lower off-target effects [17]. The permanent nature of CRISPR-induced gene knockouts enables studies of long-term biofilm development and stability, making it particularly suited for investigating chronic biofilm-associated infections and industrial biofilm applications [19] [1]. The technology has been successfully applied to diverse microbial species, including Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and various yeast species, providing insights into conserved and species-specific genetic determinants of biofilm formation [19] [18].

CRISPR Screening Approaches and Library Design

Types of CRISPR Screening Systems

CRISPRko is the most widely used approach for genome-wide knockout screens, utilizing the native Cas9 nuclease to create double-strand breaks that are repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), leading to frameshift mutations and gene knockouts [17]. However, modified CRISPR systems offer alternative screening strategies for biofilm research, each with distinct advantages as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Screening Approaches for Biofilm Research

| Screening Type | Working Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Biofilm Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRko (Knockout) | Generates irreversible gene knockouts via NHEJ, followed by phenotypic screening [17]. | Low noise; single-vector system possible; relatively easy to operate [17]. | Potential off-target effects; may produce heterozygous cells; certain genes may have low editing efficiency [17]. | Identifying essential adhesion genes, matrix producers, and regulatory pathways [18]. |

| CRISPRi (Interference) | Uses dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressors (e.g., KRAB) for reversible gene suppression [17]. | No genome breakage; can target regulatory regions and non-coding genes [17]. | Affected by chromatin accessibility; larger complex; requires stable dCas9 cell line [17]. | Studying essential genes whose knockout is lethal; investigating non-coding RNAs in biofilm regulation. |

| CRISPRa (Activation) | Uses dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators (e.g., VP64) for gene upregulation [17]. | No genome breakage; can activate silent gene clusters [17]. | Affected by chromatin accessibility; larger complex; requires stable dCas9 cell line [17]. | Identifying genes that suppress biofilm formation when overexpressed. |

Library Design and Selection

The design of the guide RNA (gRNA) library is a critical factor determining screen success. For genome-wide screens in bacteria, libraries typically include 4-6 gRNAs per gene to ensure effective perturbation and control for off-target effects [20]. The number of gRNAs required per gene depends on the desired screen coverage, with 250x coverage per gRNA being the gold standard for hit identification, though lower coverage may be sufficient for strong phenotypes [20].

Table 2: CRISPR Library Selection Based on Screening Goals

| Library Coverage | Description | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Library | Designs gRNAs for all coding genes of a species; large coverage [17]. | Unbiased discovery of novel biofilm genes; foundational research. |

| Sub-library/Focused Library | Combination of a specific class of genes (e.g., kinase family, signaling pathway, transcription factors) [17]. | Targeted studies; validating specific hypotheses; follow-up screens. |

| Custom Library | User-defined gene set based on prior omics data or specific interests. | Investigating specific pathways or gene families with known biofilm relevance. |

For biofilm research, focused libraries targeting specific gene families such as kinases, two-component systems, transcription factors, or known adhesion factors (e.g., icaADBC, fnbA, clfA) can provide deeper coverage with reduced screening workload [17] [18]. The choice between genome-wide and focused libraries depends on the research objectives, available resources, and prior knowledge of the microbial system under investigation.

Experimental Workflow for Biofilm CRISPR Screening

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for performing a CRISPR knockout screen to identify genes involved in biofilm formation:

Diagram Title: CRISPR Biofilm Screening Workflow

Library Delivery and Transduction

Efficient delivery of the CRISPR library to the target microbial cells is crucial for screen success. For bacterial systems, electroporation and conjugation are commonly used, while lentiviral transduction is preferred for eukaryotic microbes like yeast [17]. The library is typically delivered at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI < 0.3) to ensure most cells receive only a single gRNA, enabling clear genotype-phenotype associations [17]. Following transduction, cells are selected with appropriate antibiotics to eliminate untransduced cells, and a sample is collected as the "pre-selection" reference point for subsequent comparison.

For in vivo biofilm models, delivery optimization becomes more complex. Recent advances include engineered lentiviral vectors with specific tropisms, adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors coupled with transposon systems for stable integration, and nanoparticle-based delivery systems that can enhance editing efficiency up to 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems [1] [20].

Biofilm Phenotypic Assay and Selection

The core of the screen involves applying a selective pressure that enriches or depletes specific gRNAs based on their effect on biofilm formation. Both positive and negative selection strategies can be employed:

- Negative Selection: Cells are grown under biofilm-forming conditions, and gRNAs that disrupt genes essential for biofilm formation will be depleted from the population. This approach identifies genes required for biofilm development [17].

- Positive Selection: Cells that cannot form biofilms are selectively enriched, potentially identifying genes that suppress biofilm formation when knocked out [17].

Biofilm quantification can be performed using various methods, including crystal violet staining for total biomass, colony forming unit (CFU) counts for viable cells, or advanced imaging techniques like confocal microscopy coupled with quantitative image analysis tools such as BiofilmQ [2] [21]. BiofilmQ enables comprehensive 3D quantification of biofilm properties, including biovolume, thickness, surface area, and spatial distribution of fluorescent reporters, providing rich phenotypic data beyond simple biomass measurements [21].

Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

Following phenotypic selection, genomic DNA is extracted from both the selected population and the pre-selection reference, and the gRNA regions are amplified and sequenced using next-generation sequencing (NGS) [17]. The abundance of each gRNA in the selected versus reference population is compared to identify significantly enriched or depleted gRNAs.

Several bioinformatics tools are available for analysis, including MAGeCK, CERES, and CRISPRcleanR, which normalize read counts, calculate fold-changes, and perform statistical testing to identify significant hits [17]. Genes targeted by multiple significantly enriched or depleted gRNAs are considered high-confidence hits. For biofilm screens, hits are typically categorized into functional groups: adhesion factors, matrix producers, regulatory genes, metabolic enzymes, and unknown function genes.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Biofilm Screening

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPRko Library | Contains sgRNAs targeting genes of interest for knockout screening [17]. | Genome-wide (e.g., 4-6 sgRNAs/gene) or sub-library (e.g., kinase-focused); human, mouse, microbial species-specific. |

| Cas9 Expression System | Provides the Cas9 nuclease for genome editing [17]. | Constitutive or inducible expression; plasmid, viral, or stable cell line formats; species-specific codon optimization. |

| Delivery Vehicles | Facilitates introduction of CRISPR components into target cells [20]. | Lentiviral vectors (VSVG-pseudotyped), AAV vectors, lipid nanoparticles, electroporation systems. |

| Selection Antibiotics | Enriches for successfully transduced cells [17]. | Puromycin, blasticidin, gentamicin; concentration optimized for host cell type. |

| Biofilm Assay Kits | Enables quantification of biofilm formation [2] [18]. | Crystal violet staining kits, microtiter plate assays, metabolic activity assays (e.g., resazurin). |

| gRNA Amplification Primers | Allows amplification of gRNA regions for NGS library preparation [17]. | Universal primers compatible with library design; including sequencing adapters and barcodes. |

| Biofilm Imaging Tools | Enables spatial analysis of biofilm structure and composition [21]. | BiofilmQ software, fluorescent dyes (SYTO, propidium iodide), antibody labels for matrix components. |

Applications in Biofilm Gene Discovery

CRISPR knockout screening has identified numerous genes critical for biofilm formation across microbial species. In Staphylococcus aureus, screening has validated known adhesion genes (icaA, icaD, fnbA, clfA) and discovered novel regulators [18]. The technology enables systematic mapping of genetic networks controlling biofilm maturation, dispersion, and antibiotic tolerance.

In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, CRISPR screens have identified genes involved in quorum sensing, cyclic-di-GMP signaling, and matrix production as essential for biofilm formation [1]. Combining CRISPR screening with nanoparticle delivery has shown promise for targeted disruption of biofilm-related genes, with liposomal Cas9 formulations reducing P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro [1].

The applications extend to industrial and environmental biofilms, including engineering microbial strains for improved biofilm formation in bioremediation or bioproduction settings [19]. CRISPR screening can identify genetic targets for enhancing biofilm stability, substrate utilization, or product yield in industrial fermentation processes [19].

Protocol: Genome-Wide CRISPRko Screen for Biofilm-Defective Mutants

Library Amplification and Delivery

- Day 1: Transform the CRISPRko library plasmid into competent E. coli and plate on large-scale LB agar with appropriate antibiotic. Incubate overnight at 32°C.

- Day 2: Harvest the bacterial lawn and perform maxiprep plasmid isolation. Verify library representation by NGS if using a pre-made library.

- Day 3: For lentiviral production, transfect HEK293T cells with the library plasmid and packaging plasmids using PEI transfection reagent. For bacterial delivery, prepare electrocompetent target cells.

- Day 4: Harvest viral supernatant or perform electroporation. For lentiviral delivery, concentrate virus by PEG precipitation or ultracentrifugation.

- Day 5: Transduce target cells at MOI < 0.3 to ensure single gRNA integration. Add polybrene (8 μg/mL) for mammalian cells to enhance transduction.

Selection and Biofilm Assay

- Day 6: Begin antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin 2 μg/mL for mammalian cells) to eliminate untransduced cells. Continue selection for 3-7 days until >90% of control non-transduced cells are dead.

- Day 10: Harvest a reference sample (10^7 cells) for genomic DNA extraction as "pre-selection" timepoint.

- Day 11: Seed remaining cells in biofilm-forming conditions. For microtiter plate assays, seed 2×10^5 cells per well in 200 μL appropriate medium with 5-8 technical replicates. Incubate under static conditions for 24-48 hours to allow biofilm formation.

- Day 13: Quantify biofilm formation using crystal violet staining: (1) Aspirate medium; (2) Wash gently with PBS; (3) Fix with 200 μL 99% methanol for 15 minutes; (4) Air dry; (5) Stain with 200 μL 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes; (6) Wash thoroughly with water; (7) Elute bound dye with 200 μL 33% acetic acid; (8) Measure OD570 of eluent [2] [18].

- Alternative Methods: For viability-based assays, disrupt biofilms by sonication or enzymatic treatment, then perform serial dilution and CFU counting on agar plates [2].

gRNA Recovery and Sequencing

- Extract genomic DNA from both pre-selection reference and biofilm-selected populations using a maxiprep kit. Aim for >20 μg DNA per sample to ensure sufficient representation.

- Amplify gRNA regions in a two-step PCR process: (1) Primary PCR using library-specific primers; (2) Secondary PCR to add Illumina adapters and barcodes. Use high-fidelity polymerase and minimize PCR cycles (typically 12-16 cycles) to maintain representation.

- Purify PCR products using SPRI beads and quantify by fluorometry. Pool samples equimolarly and sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 50-100 reads per gRNA recommended).

Data Analysis and Hit Calling

- Process sequencing data through standard CRISPR screen analysis pipelines (e.g., MAGeCK):

- Demultiplex samples and count gRNA reads

- Normalize read counts using median ratio method

- Calculate log2 fold-change for each gRNA between selected and reference populations

- Perform robust rank aggregation (RRA) or similar statistical test to identify significantly depleted gRNAs

- Aggregate gRNA scores to gene-level scores

- Define hits as genes with FDR < 0.1 and log2 fold-change < -1 (for negative selection) or > 1 (for positive selection).

- Validate top hits using individual sgRNAs and orthogonal biofilm assays.

CRISPRi and CRISPRa for Reversible Gene Regulation Without DNA Cleavage