Eradicating the Persistent Threat: A Comprehensive Comparison of Modern Anti-Persister Cell Strategies

Persister cells, a dormant subpopulation of bacteria responsible for chronic infections and treatment relapse, represent a major challenge in antimicrobial therapy.

Eradicating the Persistent Threat: A Comprehensive Comparison of Modern Anti-Persister Cell Strategies

Abstract

Persister cells, a dormant subpopulation of bacteria responsible for chronic infections and treatment relapse, represent a major challenge in antimicrobial therapy. This article provides a systematic comparison of current and emerging persister cell elimination strategies for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational biology of persistence, details direct and indirect methodological approaches for eradication, analyzes troubleshooting and optimization for therapeutic development, and offers a critical validation of strategy efficacy across bacterial models. By synthesizing the latest research, this review aims to guide the selection and optimization of anti-persister therapies to combat recalcitrant infections.

Understanding the Enemy: The Biology of Bacterial Persistence and Its Clinical Impact

Persister cells represent a fascinating and clinically challenging survival strategy employed by bacterial and cancer cells. Unlike genetic resistance, which involves stable heritable mutations, persistence is a reversible, non-genetic phenotype that allows a small subpopulation of cells to withstand lethal doses of therapeutic agents [1] [2]. These dormant or slow-growing variants tolerate antibiotic or chemotherapeutic exposure not through specific resistance mechanisms, but primarily by arresting their metabolic activity, thereby rendering them insusceptible to drugs that target active cellular processes [2] [3]. First described in bacteria by Bigger in 1944 and later identified in cancer by Sharma et al. in 2010, persister cells across biological kingdoms share the remarkable ability to survive lethal treatments and regenerate the population once the stress is removed, causing relapse and chronic infections in bacterial contexts or cancer recurrence following therapy [1] [4].

The clinical significance of persister cells cannot be overstated. In bacteriology, they are implicated in recalcitrant chronic infections such as those occurring in cystic fibrosis patients, medical device-associated infections, and Lyme disease [2] [3]. Similarly, in oncology, drug-tolerant persister (DTP) cells act as clinically occult reservoirs that persist after treatment, seeding relapse long after the visible tumor has regressed [1]. Understanding the fundamental distinctions between phenotypic tolerance and genetic resistance is therefore crucial for developing more effective therapeutic strategies against both infectious diseases and cancer.

Table: Key Characteristics of Persister Cells Versus Genetic Resistance

| Feature | Persister Cells (Phenotypic Tolerance) | Genetic Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Basis | No genetic mutations; reversible phenotype | Stable genetic mutations or acquired resistance genes |

| Population Frequency | Small subpopulation (typically 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻³) | Entire population |

| Mechanism | Dormancy, metabolic arrest, epigenetic adaptation | Target modification, drug inactivation, efflux pumps |

| Reversibility | Transient and reversible | Stable and heritable |

| Detection Methods | Time-kill assays, microfluidic single-cell analysis | MIC determination, genetic testing |

Defining the Persister Phenotype: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

Fundamental Distinctions from Genetic Resistance

The persister phenotype operates through mechanisms fundamentally distinct from genetic resistance. While genetically resistant cells proliferate continuously in the presence of antimicrobials or chemotherapeutic agents, persister cells survive through metabolic quiescence and can resume normal growth once the treatment pressure is removed [5]. This phenotypic tolerance affects only a small fraction of the population (typically 0.0001% to 0.1%) that exists in a transient, non-growing state, whereas genetic resistance confers protection to the entire population [5] [6]. At the single-cell level, both phenomena may appear similar with growth-restricted cells escaping the action of therapeutics, but their population dynamics and underlying mechanisms differ significantly [5].

The distinction becomes particularly evident when considering therapeutic implications. Antibiotics like β-lactams that target cell wall synthesis are ineffective against dormant bacterial persisters, just as chemotherapeutic agents that target rapidly dividing cells fail to eliminate quiescent cancer DTPs [1] [7]. However, unlike genetically resistant cells that exhibit specific mechanisms such as enzymatic drug inactivation or target site modification, persisters simply bypass vulnerable processes through metabolic arrest, making them tolerant to multiple unrelated drugs simultaneously – a phenomenon termed multidrug tolerance without cross-resistance [6].

Molecular Mechanisms of Persistence

The formation of persister cells is regulated by sophisticated molecular mechanisms that induce dormancy. In bacterial systems, key players include:

Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Modules: These genetic elements produce a stable toxin and unstable antitoxin. Under stress conditions, the antitoxin degrades, allowing the toxin to inhibit essential cellular processes such as translation, replication, or ATP production, thereby inducing dormancy [8].

Stringent Response: Mediated by the alarmone (p)ppGpp, this global stress response redirects cellular resources away from growth and toward maintenance, promoting antibiotic tolerance [8].

Reduced ATP Production: Diminished cellular energy levels correlate strongly with antibiotic tolerance, as many antibiotics require active cellular processes or membrane potential for efficacy [8].

In cancer DTPs, parallel mechanisms include epigenetic reprogramming, translational remodeling, metabolic shifts, and therapy-induced mutagenesis [1]. Single-cell RNA sequencing has revealed that DTPs can coexist in multiple phenotypic states within the same tumor, exhibiting either mesenchymal-like or luminal-like transcriptional profiles in breast cancers, for instance [1]. This heterogeneity underscores the remarkable plasticity of the persister phenotype across biological systems.

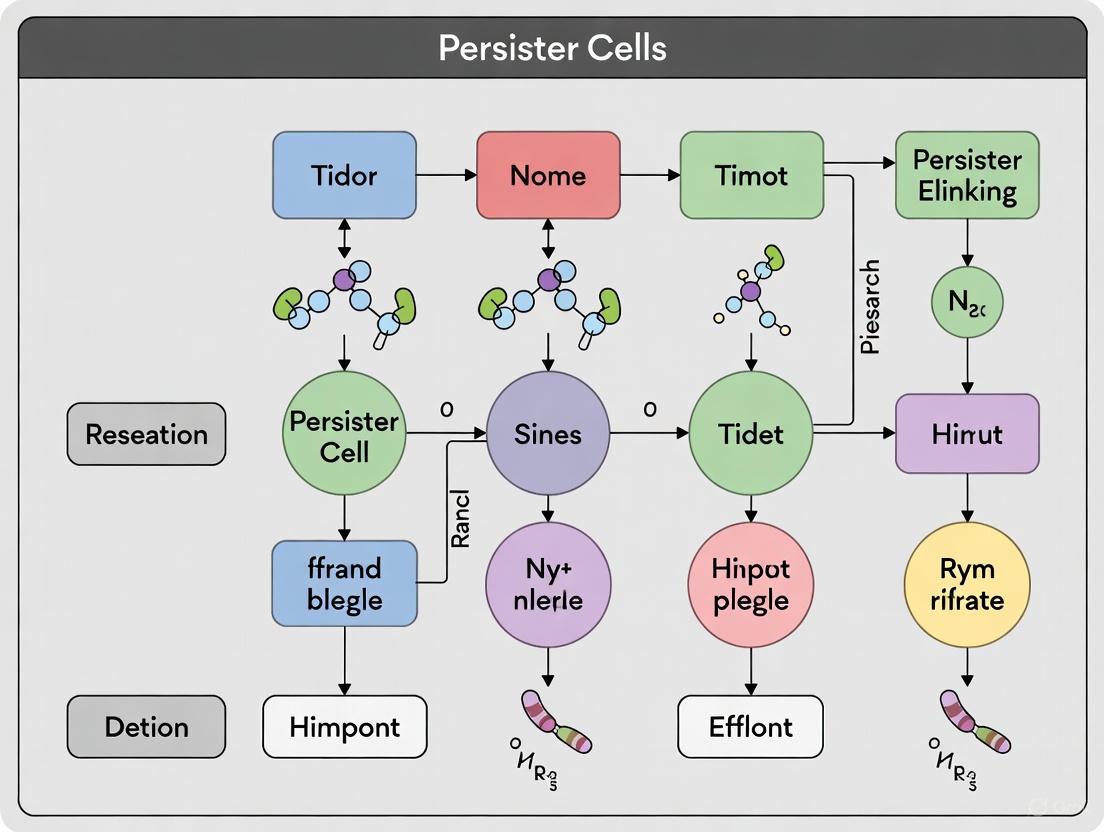

Diagram: Molecular Pathways to Persister Cell Formation. Multiple stress-responsive pathways converge to induce cellular dormancy, leading to multidrug tolerance.

Comparative Analysis: Persister Cells Versus Related Cell States

Bacterial Persisters Versus Other Dormant States

Persister cells occupy a specific niche within the spectrum of bacterial dormancy states, distinguished by their metabolic activity and revival capabilities. While often discussed alongside viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells and spores, persisters maintain distinct characteristics. VBNC cells exist in a deeper state of dormancy with significantly reduced metabolic activity and cannot grow on standard culture media without a specific recovery process, whereas persister cells maintain higher metabolic activity and can grow on agar, albeit at reduced rates [9]. Unlike spores, which represent a specialized, highly resistant dormant structure formed in response to nutrient limitation in specific genera like Bacillus and Clostridium, persisters are not morphologically distinct from their normal counterparts and can form spontaneously in virtually all bacterial populations [2].

The relationship between persistence and antibiotic tolerance is particularly nuanced. Antibiotic tolerance describes a situation where the entire bacterial population survives bactericidal treatment due to uniformly restrictive growth conditions, while persistence specifically refers to the survival of a small subpopulation under conditions that are permissive for growth for the majority of cells [5]. This distinction was elegantly demonstrated in Salmonella strains, where histidine auxotrophy in restrictive conditions led to population-wide tolerance, masking the presence of persister subpopulations that became apparent only when growth-permissive conditions were restored [5].

Cancer DTPs Versus Other Resilient Cell Populations

In oncology, drug-tolerant persister (DTP) cells share several features with other resilient cell states but remain functionally distinct. DTPs resemble dormant disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) in their ability to survive therapy and seed relapse, but differ in that DTCs are typically Ki67-negative and survive in niche-dependent states, while DTPs are exclusively induced by standard-of-care therapy and display heterogeneous phenotypes including both quiescent and slow-cycling cells [1]. The relationship between DTPs and cancer stem cells (CSCs) is particularly complex, with evidence suggesting overlap in some contexts but distinction in others. For instance, in colorectal cancer patient-derived organoids, chemotherapy-induced DTPs resemble slow-cycling CSCs, mediated by MEX3A-dependent deactivation of the WNT pathway through YAP1 [1].

Similarly, the relationship with senescent cells remains ambiguous. While DTPs share features with senescent cells including reversible arrest and metabolic reprogramming, they often lack consistent senescence markers like γH2AX or p16INK4a [1]. This ambiguity highlights the importance of precisely defining DTPs based on their operational characteristics – specifically, their survival of otherwise lethal drug exposure – rather than presumed mechanistic similarities with other cell states.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Resilient Cell States Across Biological Systems

| Cell State | Defining Characteristics | Formation Triggers | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Persisters | Non-growing, multidrug tolerant, reversible | Stress, stochastic switching | Chronic/recurrent infections |

| VBNC Cells | Deeper dormancy, non-culturable | Severe environmental stress | Undetected reservoirs |

| Cancer DTPs | Therapy-surviving, reversible, heterogeneous | SOC therapy, epigenetic plasticity | Tumor relapse, minimal residual disease |

| Cancer Stem Cells | Tumor-initiating, self-renewing | Developmental programs | Tumor initiation, recurrence |

| Senescent Cells | Irreversible growth arrest, SASP | DNA damage, telomere shortening | Aging, tissue repair, paradoxically cancer |

Experimental Approaches for Persister Cell Research

Methodologies for Isolation and Quantification

Studying persister cells presents unique methodological challenges due to their low frequency and transient nature. The gold standard for quantifying bacterial persisters is the time-kill assay, which exposes a bacterial population to a lethal antibiotic concentration and monitors survival over time, typically revealing biphasic killing kinetics where the first phase represents rapid killing of normal cells and the second slower phase reveals persister survival [6] [7]. For more detailed mechanistic insights, microfluidic devices enable single-cell analysis of persistence dynamics, allowing researchers to track the pre- and post-antibiotic exposure history of individual cells [4]. One such approach utilizes a membrane-covered microchamber array (MCMA) that encloses E. coli cells in 0.8-µm deep microchambers, enabling visualization of over one million individual cells and revealing that many persisters were actually growing before antibiotic treatment [4].

In cancer research, analogous approaches include lineage tracing through DNA barcoding combined with single-cell RNA sequencing to follow the fates of individual cancer cells after treatment [1]. Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) and xenografts (PDXs) provide more physiologically relevant models for studying cancer DTPs, though these often lack immune components and other systemic influences [1]. For both bacterial and cancer persisters, critical experimental considerations include the growth phase of the population (with stationary phase cultures typically yielding higher persister frequencies), the specific therapeutic agent used (as persistence is often drug-specific), and the duration of exposure [6] [7].

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Persister Cell Research. Multiple parallel approaches enable quantification and characterization of persister cells.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methodologies

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Persister Cell Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Devices (MCMA) | Single-cell confinement and imaging | Tracking E. coli persister histories pre/post antibiotic exposure [4] |

| DNA Barcoding | Lineage tracing at single-cell resolution | Mapping clonal fates of cancer cells after treatment [1] |

| Fluorescence Dilution (FD) | Monitoring growth status at single-cell level | Distinguishing growing vs. non-growing Salmonella in macrophages [5] |

| Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) | Physiologically relevant 3D culture models | Studying colorectal cancer DTPs and their resemblance to slow-cycling CSCs [1] |

| Membrane-Active Compounds | Disrupt membrane integrity to enhance antibiotic uptake | Anti-persister agents like XF-73, SA-558 against S. aureus [2] [3] |

| Metabolic Adjuvants | Reactivate persister metabolism | Mannitol, pyruvate to enhance aminoglycoside uptake [8] |

Quantitative Analysis of Persister Cell Dynamics

Survival Kinetics and Population Heterogeneity

Persister cell frequencies vary dramatically across species, growth conditions, and antibiotic classes. Comprehensive analysis of persistence across 36 bacterial species and 54 antibiotics revealed that the median percentage of surviving cells spans five orders of magnitude, from 7 × 10⁻⁴% in P. putida to 100% in E. faecium [7]. For species with substantial data points (≥20), the range was narrower but still varied from 0.01% in A. baumannii to approximately 5% in multidrug-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [7]. This extensive variation underscores the context-dependent nature of persistence and cautions against overgeneralization from model systems.

The drug-specificity of persistence is particularly remarkable. Even antibiotics with nearly identical mechanisms of action, such as ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid (both DNA gyrase inhibitors), can select for different persister subpopulations, suggesting that physiological changes beyond simple dormancy underlie persistence [6]. This contrasts with the multidrug tolerance often observed in laboratory E. coli mutants, highlighting the importance of studying persistence in diverse clinical and environmental isolates [6].

Mathematical Modeling of Persister Dynamics

Quantitative modeling of persister populations typically employs a two-state framework where cells switch stochastically between normal and persister states [6]. In this model, normal cells die at rate μ and switch to the persister state at rate α during antibiotic treatment, while persister cells do not die or grow but switch back to the normal state at rate β [6]. This mathematical formalism allows researchers to derive persister fractions that are independent of experimental idiosyncrasies, facilitating cross-study comparisons that are otherwise complicated by variations in antibiotic exposure times, growth states assessed, and methodology differences that have historically plagued the field [6].

Table: Bacterial Persistence Frequencies Across Species and Antibiotic Classes

| Bacterial Species | Antibiotic Class | Typical Persistence Frequency | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | β-lactams | 0.001% - 0.1% | Growth phase, medium richness |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Fluoroquinolones | 0.01% - 1% | Biofilm state, metabolic activity |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Aminoglycosides | 0.1% - 5% | Quorum sensing, stress response |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Multiple classes | 0.001% - 0.01% | Metabolic heterogeneity, granuloma environment |

| Salmonella enterica | β-lactams | 0.001% - 0.1% | Intracellular location, histidine availability |

The distinction between phenotypic tolerance in persister cells and genetic resistance has profound implications for therapeutic development. Traditional antibiotic discovery platforms that screen for compounds active against rapidly dividing bacteria have systematically overlooked anti-persister agents, creating a critical gap in our antimicrobial arsenal [2] [3]. Similarly, cancer drug development has historically prioritized agents that shrink bulk tumors rather than those that target the minimal residual disease maintained by DTPs [1]. Promising strategies emerging against bacterial persisters include membrane-active compounds that directly disrupt cell integrity independent of metabolic state, metabolite-antibiotic combinations that resuscitate persisters to render them susceptible, and prevention of persister formation through interference with quorum sensing or stress signaling pathways [2] [3] [8].

For cancer DTPs, analogous approaches include epigenetic modulators that prevent or reverse the adaptive reprogramming underlying drug tolerance, and therapeutic combinations that simultaneously target multiple co-existing DTP phenotypes [1]. In both fields, the field is moving toward more physiologically relevant model systems that better capture the complexity of host environments, and developing more sophisticated single-cell technologies to unravel the heterogeneity of persister populations. As research bridges these methodological gaps, targeting persister cells represents a promising frontier for overcoming therapeutic failure and preventing relapse across infectious disease and oncology.

Bacterial persisters are a subpopulation of cells that exhibit transient, non-heritable tolerance to high-dose antibiotic treatment without possessing genetic resistance mutations [2] [10]. These dormant cells were first identified by Joseph Bigger in 1944 during penicillin efficacy tests against Staphylococcus spp., where a small subset of cells survived despite being genetically susceptible to the antibiotic [11]. This phenomenon is now recognized as a major contributor to chronic and recurrent infections across clinical settings, including cystic fibrosis, medical device-associated infections, and urinary tract infections [2] [10]. Unlike resistant bacteria that possess stable genetic mutations enabling growth in antibiotic presence, persisters survive antibiotic exposure through a metabolically inactive or slow-growing state that prevents antibiotics from engaging their cellular targets [10]. When the antibiotic pressure is removed, these cells can resuscitate and repopulate, leading to infection relapse [12].

The study of persistence represents a particular challenge due to the transient nature of the phenotype and the low frequency of persister cells within bacterial populations, typically ranging from 0.001% to 1% [11]. This review systematically compares the primary molecular mechanisms driving persister formation, with particular focus on toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules and stochastic processes, while providing experimental methodologies for their investigation and contextualizing these findings within current drug development strategies aimed at eradicating persistent infections.

Classification and Characteristics of Persister Cells

Persister cells are broadly categorized based on their formation mechanisms and the growth phase in which they emerge. Understanding these classifications provides critical insights into the heterogeneous nature of bacterial persistence and informs targeted therapeutic strategies.

Table 1: Classification of Bacterial Persister Types

| Persister Type | Formation Trigger | Growth Phase | Key Characteristics | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Environmental stress cues (e.g., nutrient limitation) | Stationary phase | Preexisting non-growing cells; bet-hedging strategy | E. coli hipA7 mutants [11] |

| Type II | Stochastic fluctuations in gene expression | Throughout exponential phase | Slow-growing variants within actively dividing population | E. coli hipQ mutants [11] |

| Type III (Specialized) | Specific antibiotic-induced stress | Independent of growth phase | Antibiotic-specific persistence mechanisms; not necessarily slow-growing | Mycobacterium catalase-peroxidase low expressors [11] |

The "dormancy depth" hypothesis suggests these persister types exist along a spectrum of metabolic activity, with Type I persisters generally exhibiting the lowest metabolic rates and Type II maintaining some basal metabolism [10]. This continuum may extend to viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells, which represent an even more profoundly dormant state that often requires specific resuscitation signals to regain culturability [10] [11]. The classification system provides researchers with a framework for designing experiments that account for this heterogeneity in persister populations.

Molecular Mechanisms of Persister Formation

Toxin-Antitoxin Systems as Central Regulators

Toxin-antitoxin systems represent one of the most extensively studied mechanisms of persister formation. These genetic modules consist of a stable toxin protein that disrupts essential cellular processes and an unstable antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin under normal conditions [13] [10]. Under stress conditions, proteases such as Lon and ClpP preferentially degrade the labile antitoxin, freeing the toxin to exert its effects [10] [14]. This system allows bacteria to rapidly transition to a dormant state in response to environmental challenges.

TA systems are currently classified into eight types based on the nature of the antitoxin and its mechanism of toxin neutralization [13] [10]. Type I and II systems are the most prevalent and best characterized in the context of persistence:

Type I TA systems: Feature protein toxins whose translation is inhibited by antisense RNAs. Examples include TisB/istR and Hok/Sok in E. coli, where the TisB and Hok toxins integrate into the bacterial membrane, dissipating the proton motive force and reducing ATP levels [10].

Type II TA systems: Consist of both protein toxins and antitoxins that form stable complexes. The HipA/HipB system was the first chromosomal TA module linked to persistence, with HipA phosphorylating glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (GltX), leading to accumulation of uncharged tRNA and activation of the stringent response [10]. Another well-characterized system, MazF/MazE, is co-transcribed with relA (which activates the stress sigma factor ϬS) in Gram-negative bacteria and with sigB in Gram-positive bacteria, directly linking TA activity to general stress response pathways [13].

Table 2: Major Toxin-Antitoxin Systems in Bacterial Persistence

| TA System | Type | Toxin Mechanism | Role in Persistence | Regulatory Connections |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HipAB | II | HipA phosphorylates GltX, triggering stringent response | First chromosomal TA linked to persistence; hipA7 mutants increase persistence | Activates RelA, increasing (p)ppGpp [10] |

| MazEF | II | MazF is an endoribonuclease that cleaves mRNA | Nutrient starvation-induced persistence; among most widespread TA systems | Co-transcribed with relA (ϬS activation) and sigB (ϬB encoding) [13] |

| MqsRA | II | MqsR cleaves mRNA; MqsA regulates RpoS and CsgD | Biofilm-associated persistence; activates GhoT toxin | Represses rpoS and csgD, reducing biofilm formation [14] |

| TisB/istR | I | TisB disrupts membrane potential, reducing ATP | SOS response-induced persistence after DNA damage | Activated by DNA damage through LexA cleavage [10] |

| RelBE | II | RelE cleaves mRNA in ribosome-dependent manner | Nutritional stress-induced persistence | Activated by nutrient limitation [14] |

Beyond their role in persistence, TA systems function within broader physiological contexts, including phage inhibition through growth reduction, stabilization of genetic elements, and biofilm formation [14]. Recent evidence suggests TA systems may operate as part of an integrated nutrient-responsive cybernetic system (NRCS) that optimizes bacterial fitness by regulating population dynamics throughout the life cycle [13]. In this model, intracellular nutrient concentrations feedback to control growth, death, and growth/death arrest, with TA systems working in concert with alternative sigma factors ϬS and ϬB to efficiently transition between reproductive and survival states [13].

Stochastic Processes and Population Heterogeneity

Stochastic variation in gene expression represents a fundamental mechanism of persister formation independent of environmental cues. This phenomenon results from random fluctuations in cellular components that create distinct phenotypic states within genetically identical populations [11]. Type II persisters emerge spontaneously throughout all growth phases due to this natural heterogeneity, with varying subpopulations exhibiting differential expression of persistence-related genes.

Single-cell studies have revealed that stochastic expression of TA systems and other persistence-related genes creates a mixture of phenotypic states within bacterial populations [11]. This bet-hedging strategy ensures that a subpopulation is always prepared for sudden environmental challenges, enhancing overall population survival. Mathematical modeling of these stochastic processes has demonstrated biphasic killing curves in response to antibiotic treatment - an initial rapid decline of susceptible cells followed by a slower decline of the persistent subpopulation [10] [11].

Integrated Stress Response Pathways

Multiple signaling networks converge to regulate the entry into and exit from the persistent state:

Stringent Response: Nutrient limitation triggers RelA and SpoT to synthesize the alarmone (p)ppGpp, which dramatically reprograms cellular metabolism by downregulating energy-intensive processes and activating stress adaptation pathways [10]. (p)ppGpp directly influences persister formation through its effects on TA systems and cellular energetics.

SOS Response: DNA damage leads to LexA autocleavage, derepressing DNA repair genes and activating type I TA systems like TisB/istR that promote persistence [10] [11]. This pathway connects genotoxic stress to dormancy induction.

Quorum Sensing: Bacterial cell-cell communication via small signaling molecules influences persister formation density-dependently. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, quorum sensing signals like phenazine pyocyanin and N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone increase persister formation through oxidative stress and metabolic changes [2] [3].

The diagram below illustrates the integrated network of stress responses and TA systems regulating persister formation:

Experimental Approaches for Persister Research

Methodologies for Inducing and Quantifying Persisters

Research on persister cells requires specialized methodologies that account for their low abundance and transient phenotype. Standardized protocols have been developed to induce, isolate, and quantify persisters across different bacterial species and experimental conditions:

Antibiotic Killing Curves: The gold standard for persister quantification involves treating mid-log or stationary phase cultures with bactericidal antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides) at 5-10× MIC and monitoring viability over time through plating and colony counting [10]. The characteristic biphasic killing curve demonstrates rapid killing of regular cells followed by a subpopulation that dies significantly slower.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Using fluorescent dyes that differentiate metabolic activity (e.g., CFSE, propidium iodide), researchers can isolate and quantify subpopulations with reduced metabolic activity that correlate with persistence [10].

Microfluidics and Single-Cell Analysis: Advanced platforms enable real-time observation of individual cells before, during, and after antibiotic exposure, allowing researchers to correlate persistence with specific pre-exposure states and track resuscitation dynamics [10] [1].

Table 3: Experimental Models and Their Applications in Persistence Research

| Experimental Model | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro planktonic cultures | Simplified system; controlled conditions; reproducible persister induction | Initial characterization of persister formation mechanisms; antibiotic screening | May not reflect host-environment complexity |

| Biofilm models | Reflects natural bacterial growth state; includes extracellular matrix | Studying matrix protection and niche-specific persistence; disinfectant testing | Technical challenges in complete recovery for quantification |

| Macrophage infection models | Intracellular environment; includes host-pathogen interactions | Studying immune evasion and antibiotic penetration issues | Difficult to separate bacteria from host cells for quantification |

| Animal infection models | Includes full immune system and in vivo pharmacokinetics | Studying persistence in realistic therapeutic contexts; assessing combination therapies | Ethical considerations; high cost; complex data interpretation |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Investigating persister mechanisms requires specific reagents that target key pathways in dormancy formation. The following table details essential research tools for experimental studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Persister Cell Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Mechanism | Application in Persistence Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| TA System Inducers | Mitomycin C (SOS inducer); serine hydroxamate (stringent response inducer) | Activates stress response pathways leading to TA system activation | Studying upstream triggers of persistence; validating TA system function |

| Protease Inhibitors | Lon protease inhibitor; ClpP inhibitors (e.g., ADEP4) | Blocks antitoxin degradation; stabilizes antitoxin levels | Testing TA activation mechanisms; combination therapies against persisters |

| Metabolic Probes | CFSE; CTC; resazurin; SYTOX Green | Labels cells based on metabolic activity or membrane integrity | Differentiating and isolating persisters from susceptible population |

| - Stringent Response Modulators: (p)ppGpp analogs; RelA inhibitors | Alarms nucleotide signaling; modulates stringent response | Investigating connection between nutrient stress and persistence | |

| Membrane-Active Compounds | CCCP; Nigericin; synthetic retinoids (CD437, CD1530) | Disrupts proton motive force and membrane integrity | Studying energy depletion-induced persistence; enhancing antibiotic uptake |

| ROS-Generating Agents | Methyl viologen; H₂O₂; MPDA/FeOOH-GOx@CaP nanoparticles | Induces oxidative stress; directly damages cellular components | Investigating oxidative stress role in persistence; developing anti-persister strategies |

Comparative Analysis of Persister Formation Mechanisms

The multiple pathways to persistence represent distinct but interconnected strategies that bacteria employ to survive adverse conditions. Each mechanism offers particular advantages under specific environmental contexts:

Toxin-antitoxin systems provide a rapid, post-translational response to stress that enables immediate metabolic downshift without requiring new gene expression [13] [14]. This makes TA systems particularly effective against sudden stressors like antibiotic exposure or phage infection. The regulatory connectivity of TA systems with global stress networks (stringent response, sigma factors) allows for coordinated population-level adaptation [13].

In contrast, stochastic persistence represents a bet-hedging strategy that prepares a subpopulation for unforeseen challenges, ensuring that some cells are always in a protected state regardless of environmental signals [11]. This mechanism is particularly advantageous in fluctuating environments where stress events are unpredictable.

From an evolutionary perspective, the coexistence of multiple persistence mechanisms within bacterial populations reflects the fitness advantage of phenotypic heterogeneity. While TA-mediated persistence requires energy expenditure for toxin and antitoxin production, and stochastic persistence carries the opportunity cost of reduced growth in the persistent subpopulation, both strategies enhance population survival under lethal stress, providing a selective advantage that maintains these traits across generations [13] [11].

The mechanistic understanding of persister formation has advanced significantly from the initial observation of antibiotic-surviving subpopulations to the current molecular-level characterization of TA systems, stochastic processes, and integrated stress responses. The evidence clearly demonstrates that bacterial persistence is not a singular phenomenon but rather a spectrum of dormant states enabled by multiple complementary mechanisms.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the complex interactions between different persistence pathways and developing models that account for their synergistic effects. The application of single-cell technologies, advanced imaging, and multi-omics approaches will provide unprecedented resolution into the temporal dynamics of persister formation and resuscitation. From a therapeutic perspective, targeting key nodes in the persistence network - such as TA system activation, antitoxin degradation, or resuscitation signals - represents a promising approach for combating chronic and recurrent bacterial infections.

As our understanding of these dormant bacterial subpopulations continues to evolve, so too will strategies for their eradication, ultimately addressing a significant challenge in clinical management of bacterial diseases and industrial control of microbial contamination.

Bacterial persister cells represent a non-genetic, phenotypic variant of regular bacterial cells that exhibit a transient, high tolerance to antibiotic treatments by entering a dormant, metabolically inactive state [15] [2] [16]. Unlike resistant bacteria, which possess genetic mechanisms to grow in the presence of antibiotics, persisters do not grow during antibiotic exposure but can resume growth once the treatment ceases, leading to recurrent infections [17] [18]. This phenomenon is a significant contributor to the recalcitrance of chronic and biofilm-associated infections, posing a major challenge in clinical settings [15] [19]. It is estimated that over 65% of all microbial infections are associated with biofilms, which serve as reservoirs for these persistent cells [15] [20]. Their survival undermines conventional antibiotic therapies, which primarily target actively growing cells, making the development of specific anti-persister strategies a critical frontier in the fight against persistent infections [2] [3].

Molecular Mechanisms of Persister Formation and Survival

The formation and survival of persister cells are governed by a complex network of biochemical pathways that enable bacteria to survive lethal stress. Understanding these mechanisms is foundational to developing targeted elimination strategies.

Key Signaling Pathways in Persistence

The diagram below illustrates the core molecular pathways that regulate bacterial persistence.

Figure 1: Core molecular pathways regulating bacterial persistence. Environmental stressors trigger a stringent response, activating ppGpp, which induces toxin-antitoxin systems and ribosome hibernation, leading to cellular dormancy and antibiotic tolerance.

The formation of persister cells is primarily a stress response. Key pathways include:

- Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems: These genetic modules encode a stable toxin that disrupts essential cellular processes (e.g., translation via mRNA cleavage) and a labile antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin [16] [17]. Under stress, proteases like Lon degrade the antitoxin, freeing the toxin to induce a dormant state. The HipA toxin, for instance, inhibits translation by phosphorylating elongation factor Tu, while MqsR acts as an mRNA interferase [17].

- The Stringent Response and (p)ppGpp: Nutrient limitation and other stresses trigger the accumulation of the alarmone (p)ppGpp [16]. This molecule acts as a central regulator of persistence by modulating RNA polymerase and promoting the transcription of stress response genes, including those in TA systems [17].

- Ribosome Hibernation: (p)ppGpp also stimulates the production of factors like Ribosome Modulation Factor (RMF) and RaiA, which inactivate ribosomes by forming 100S dimers or stabilizing inactive 70S complexes, thereby halting protein synthesis [16].

The Biofilm Environment as a Persister Niche

Biofilms are structured communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. This environment is a hotspot for persister formation due to:

- Heterogeneous Microenvironments: Gradients of nutrients and oxygen within biofilms create zones of slow growth or metabolic arrest, naturally promoting dormancy [15] [19].

- Physical Protection: The EPS matrix, composed of polysaccharides, extracellular DNA, and proteins, acts as a physical barrier that impedes antibiotic penetration and protects bacteria from host immune responses [15] [19].

- Quorum Sensing (QS): Cell-to-cell communication via QS molecules can regulate persister formation. For example, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, QS signals like phenazine pyocyanin can increase persister levels by inducing oxidative stress [2] [3].

Comparative Analysis of Persister Cell Elimination Strategies

A range of strategies has been developed to target the unique challenge of persister cells. The table below provides a high-level comparison of these approaches.

Table 1: Overview of Major Strategic Approaches to Combat Bacterial Persisters

| Strategic Approach | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Killing | Targets growth-independent structures like cell membranes or enables uncontrolled protein degradation [2] [3]. | Independent of bacterial metabolic state; effective against deep dormancy [2]. | Potential for off-target toxicity against host mammalian membranes [2] [3]. |

| Indirect Killing (Re-sensitization) | Prevents persister formation or wakes dormant cells, making them susceptible to conventional antibiotics [2] [3]. | Can leverage existing antibiotics; may reduce selection for resistance [2] [12]. | May not affect all persister sub-populations; efficacy depends on successful reactivation [3]. |

| Nanomaterial-Based | Uses nano-scale agents for physical disruption, targeted drug delivery, or generating lethal reactive oxygen species (ROS) [12]. | Enhanced biofilm penetration; multiple mechanisms of action; customizable functionality [12]. | Complex manufacturing; potential long-term toxicity and translational barriers require further study [12]. |

Direct Killing Strategies

Direct killing strategies aim to destroy persister cells by targeting essential, growth-independent cellular structures. The following table summarizes experimental data for selected direct-killing agents.

Table 2: Experimental Data for Selected Direct-Killing Anti-Persister Agents

| Agent / Compound | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Experimental Model | Reported Efficacy | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XF-73 | Disrupts bacterial cell membrane; generates ROS upon light activation [2] [3]. | Staphylococcus aureus persisters (in vitro) [2]. | Effective against non-dividing and slow-growing cells [2]. | [2] [3] |

| ADEP4 | Activates ClpP protease, leading to uncontrolled ATP-independent protein degradation [2] [3]. | S. aureus and E. coli persisters (in vitro) [2]. | Renders cells unable to resuscitate; works synergistically with rifampicin to eradicate persisters [2]. | [2] [3] |

| Pyrazinamide (PZA) | Prodrug converted to pyrazinoic acid; disrupts membrane energetics and targets PanD protein [2] [18]. | Mycobacterium tuberculosis persisters (in vitro and in clinical use) [2] [18]. | Cornerstone of TB therapy due to unique activity against dormant bacilli [2] [18]. | [2] [3] [18] |

| Cationic Silver Nanoparticle Shelled Nanodroplets (C-AgND) | Interacts with negatively charged EPS; disrupts membranes and biofilms [2]. | S. aureus persisters within biofilms (in vitro) [2]. | Effective killing of persisters within biofilms [2]. | [2] [3] |

Experimental Protocol for Direct Killing Assay: A standard protocol for evaluating direct-killing agents involves:

- Persister Generation: A high-titer stationary-phase culture or biofilm of the target bacterium (e.g., S. aureus) is treated with a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic like ciprofloxacin (e.g., 10x MIC) for several hours to kill the actively growing population [17].

- Cell Washing and Confirmation: The surviving cells are washed to remove the first antibiotic and are plated on antibiotic-free media to confirm their persister status (viable but non-growing) [16].

- Treatment with Test Agent: The purified persister population is exposed to the candidate anti-persister compound (e.g., XF-73 at a range of concentrations) for a defined period.

- Viability Assessment: Serial dilutions are performed, and colonies are counted after plating to quantify the reduction in viable persister cells (CFU/mL) compared to an untreated persister control [2] [17].

Indirect Killing and Synergistic Strategies

This approach focuses on reversing the dormant state or preventing its establishment, thereby re-sensitizing persisters to conventional antibiotics.

Table 3: Experimental Data for Indirect and Synergistic Anti-Persister Strategies

| Strategy / Compound | Proposed Mechanism of Action | Experimental Model | Reported Efficacy / Synergy | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Reactivators (e.g., Mannitol, Serine) | Reactivates bacterial metabolism by stimulating central carbon metabolism or the electron transport chain [12]. | E. coli and S. aureus persisters (in vitro) [12]. | "Wake-and-kill"; re-sensitizes persisters to aminoglycoside antibiotics [12]. | [12] |

| Membrane Permeabilizers (e.g., MB6, PMBN) | Disrupts the integrity of the bacterial membrane, increasing uptake of co-administered antibiotics [2] [3]. | MRSA persisters (in vitro) [2]. | Cotreatment with gentamicin showed strong anti-persister activity [2]. | [2] [3] |

| H₂S Scavengers / CSE Inhibitors | Inhibits bacterial hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) biogenesis, which protects under stress [2] [3]. | S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, E. coli persisters (in vitro) [2]. | Reduces persister formation and potentiates killing by gentamicin [2]. | [2] [3] |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors (e.g., Brominated Furanones) | Inhibits cell-cell communication systems that regulate multicellular behaviors like biofilm and persister formation [2]. | P. aeruginosa (in vitro) [2]. | Reduces persister formation without affecting growth [2]. | [2] [3] |

Experimental Protocol for Synergy Assay (Checkboard):

- Persister Preparation: Persister cells are generated and purified as described in the direct-killing protocol.

- Checkerboard Setup: A range of concentrations of the conventional antibiotic (e.g., gentamicin, from 0 to 8x MIC) is combined with a range of concentrations of the sensitizing agent (e.g., a membrane permeabilizer like MB6) in a 96-well microtiter plate.

- Inoculation and Incubation: The purified persister suspension is added to each well.

- Analysis: After incubation, viability is assessed. The Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) index is calculated to determine if the interaction is synergistic (FIC ≤ 0.5) [2].

Emerging Nanomaterial-Based Strategies

Nanotechnology offers innovative tools to combat persisters, leveraging unique physicochemical properties for targeted action.

Table 4: Emerging Nanoagents for Targeting Bacterial Persisters

| Nanoagent | Composition | Mechanism of Action | Infection Model | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caff-AuNPs | Caffeine-functionalized Gold Nanoparticles | Disrupts mature biofilms and eradicates embedded dormant cells [12]. | In vitro, planktonic and biofilm-associated persisters [12]. | [12] |

| AuNC@CPP | Gold Nanoclusters with Cell-Penetrating Peptide | Induces membrane hyperpolarization by disrupting the proton gradient [12]. | Chronic suppurative otitis media (in vitro) [12]. | [12] |

| PS+(triEG-alt-octyl)PDA | Cationic Polymer on Polydopamine Nanoparticles | Photothermal-triggered release reactivates persisters via the electron transport chain and then disrupts membranes [12]. | In vitro, biofilm-associated persisters [12]. | [12] |

| MPDA/FeOOH-GOx@CaP | ROS-generating Hydrogel Microspheres | Glucose oxidase produces H₂O₂, converted to lethal hydroxyl radicals via Fenton-like reactions in the acidic biofilm microenvironment [12]. | Prosthetic joint infection model (in vitro) [12]. | [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Experimental Models

This section details essential reagents, compounds, and models used in persister research, providing a resource for designing experiments.

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Persister Cell Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane-Targeting Compounds | Directly lyse persister cells by disrupting cell envelope integrity, independent of metabolism [2] [3]. | XF-73, SA-558, synthetic retinoids (CD437, CD1530), thymol conjugates (TPP-Thy3) [2] [3]. |

| Metabolic Modulators | Reactivate dormant persisters ("wake") or inhibit their formation, re-sensitizing them to antibiotics [2] [12]. | Reactivators: Mannitol, serine. Inhibitors: Nitric oxide (NO), Cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) inhibitors, medium-chain fatty acids (e.g., lauric acid) [2] [3] [12]. |

| Synergistic Sensitizers | Used in combination with conventional antibiotics to enhance their uptake or efficacy against persisters [2] [3]. | Membrane permeabilizers (PMBN, SPR741), H₂S scavengers [2] [3]. |

| Engineered Nanomaterials | Act as delivery vehicles for antimicrobials or possess intrinsic anti-persister activity (e.g., ROS generation, physical disruption) [12]. | Gold nanoparticles (Caff-AuNPs, AuNC@CPP), ROS-generating microspheres (MPDA/FeOOH-GOx@CaP), polymer nanocomposites [12]. |

| Bacterial Strains & Models | Provide relevant experimental systems for studying persistence and testing interventions. | Laboratory Strains: E. coli K-12, P. aeruginosa PAO1, S. aureus USA300 [15] [17]. Clinical Isolates: High-persister (hip) mutants from cystic fibrosis (CF) patients [15] [20]. Biofilm Models: Static (microtiter plate), flow-cell systems, in vivo catheter models [19]. |

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for screening and evaluating potential anti-persister therapeutic agents.

Figure 2: Anti-persister therapeutic development workflow. The process progresses from simple in vitro screens to complex in vivo models, with parallel mechanism-of-action studies.

The eradication of bacterial persister cells is paramount for successfully treating chronic and biofilm-associated infections. While conventional antibiotics remain ineffective, research has yielded a diversified arsenal of strategies, from direct membrane-lysing agents and metabolic re-sensitizers to sophisticated nanotechnology-based solutions. The experimental data compiled in this guide demonstrates that no single strategy is a universal solution; each possesses distinct advantages and limitations. Future progress will likely depend on combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple vulnerabilities—for instance, using a nanomaterial to disrupt the biofilm and deliver a metabolic activator alongside a conventional antibiotic. Furthermore, bridging the gap between promising in vitro results and clinical success requires standardized models and a deeper understanding of persister physiology in host environments. The continued development and comparison of these innovative strategies, as outlined here, provide a clear path toward overcoming one of the most stubborn challenges in modern antimicrobial therapy.

Bacterial persistence represents a significant challenge in clinical medicine, contributing to chronic and relapsing infections. Persisters are a subpopulation of genetically susceptible cells that exhibit transient, high-level tolerance to antibiotic treatment without acquiring heritable resistance mutations [18] [10]. This phenomenon was first identified by Joseph Bigger in 1944 when he observed that penicillin failed to eradicate all Staphylococcus cells, leaving a small fraction of survivors he termed "persisters" [18] [11]. The classification of persisters into distinct types provides a crucial framework for understanding their formation mechanisms, metabolic diversity, and implications for treatment strategies. This review systematically compares Type I, II, and III persister cells, examining their characteristic features, molecular drivers, and the experimental approaches essential for their study and eradication.

Classification and Comparative Analysis of Persister Types

Persister cells are broadly categorized based on their formation mechanisms, triggers, and metabolic states. The established classification system recognizes three primary types, each with distinct characteristics and physiological profiles.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Persister Cell Types

| Feature | Type I (Triggered) | Type II (Stochastic) | Type III (Specialized) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Trigger | Environmental stress (e.g., starvation, stationary phase) [11] | Spontaneous, stochastic errors during replication [11] | Antibiotic-specific stress signals or spontaneous mechanisms [11] |

| Growth State Before Antibiotic Exposure | Non-growing or growth-arrested [11] | Slow-growing [11] | Often actively growing [21] [11] |

| Primary Metabolic State | Dormant, low metabolic activity | Reduced but continuous metabolism | Variable, can be metabolically active |

| Key Regulatory Factors | Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) modules, (p)ppGpp [11] | TA modules, (p)ppGpp, stochastic gene expression [22] [11] | Antibiotic-specific mechanisms (e.g., low enzyme levels for prodrug activation) [11] |

| Persistence in Biofilms | Common | Common | Yes, can be induced by stress signals [8] |

Table 2: Elimination Strategies and Vulnerabilities by Persister Type

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Effectiveness Against Persister Type |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Membrane Attack | Disrupts cell membrane integrity, causes lysis [2] [3] | Effective against all types (growth-independent) |

| Metabolite Reprogramming ("Wake and Kill") | Reactivates metabolism to sensitize cells to antibiotics [8] | Most effective against Type I and II |

| Inhibition of Persister Formation | Targets pathways like (p)ppGpp accumulation or H₂S biogenesis [2] [3] | Prevents formation of Type I and II |

| Synergy with Antibiotics | Membrane permeabilizers increase antibiotic uptake [2] [3] | Enhances killing of all types, particularly Type III |

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and regulatory networks that drive the formation and maintenance of the different persister types, integrating triggers like stress, stochastic events, and antibiotic-specific actions.

Molecular Mechanisms and Metabolic Underpinnings

The formation and survival of persister cells are governed by complex molecular networks that regulate bacterial metabolism and stress responses.

Core Regulatory Systems

Several interconnected systems are central to persister formation across types. The Stringent Response, mediated by the alarmone (p)ppGpp, acts as a master regulator during nutrient limitation. (p)ppGpp accumulates and drastically reprograms cellular metabolism, shutting down energy-intensive processes like ribosome synthesis and promoting a dormant state [22] [10] [8]. This response is crucial for the formation of Type I persisters and also plays a role in Type II persistence.

Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) systems are another key component. These genetic modules consist of a stable toxin that can disrupt essential cellular processes (e.g., protein translation, DNA replication) and a labile antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin. Under stress, proteases degrade the antitoxin, allowing the toxin to induce dormancy [10] [11]. For example, in E. coli, the HipA toxin phosphorylates a glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, inhibiting translation and triggering persistence via the stringent response [10]. The TisB toxin can form pores in the inner membrane, dissipating the proton motive force (PMF) and reducing ATP levels, leading to a dormant state [10].

Metabolic Basis of Tolerance and Reactivation

A defining feature of Type I and II persisters is a reduction in metabolic activity, which underlies their antibiotic tolerance. Conventional antibiotics primarily target active processes like cell wall synthesis, DNA replication, and protein synthesis. In dormant persisters, these targets are largely inactive, rendering the drugs ineffective [2] [3] [8].

This metabolic dormancy exists on a continuum. Studies using ¹³C-isotopolog profiling on stationary-phase Staphylococcus aureus challenged with daptomycin have revealed that persisters maintain a baseline level of metabolic activity, with active glycolysis, TCA cycle, and amino acid anabolism [23]. This residual metabolism is critical for maintaining cell integrity and the potential for "resuscitation."

The "Wake and Kill" strategy exploits this metabolic plasticity. Research shows that certain metabolites can reprogram persister metabolism, reversing tolerance. For instance, mannitol and fructose can restore the PMF, facilitating the uptake of aminoglycoside antibiotics and leading to effective killing [8]. Similarly, exogenous pyruvate promotes the uptake of gentamicin in Vibrio alginolyticus [8]. This approach is particularly promising for eradicating Type I and II persisters.

Advanced Research Methodologies and Tools

Studying persisters is challenging due to their low abundance and transient phenotype. Advanced methodologies are required for their isolation, characterization, and analysis.

Experimental Workflows

A standard protocol for studying persister recovery involves several key stages. The process begins with obtaining a pure bacterial culture and exposing it to a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic for a defined period. This is followed by the removal of the antibiotic, typically through washing or dilution. The subsequent recovery phase is monitored using spectrophotometry (OD₆₀₀) to track population regrowth and flow cytometry to analyze the physiological states of individual cells during resuscitation [24]. This single-cell approach is vital given the heterogeneity of persister populations.

Microfluidic devices, such as the Membrane-Covered Microchamber Array (MCMA), have revolutionized single-cell analysis. These devices allow researchers to trap and observe over one million individual cells, tracking their lineage and morphological changes before, during, and after antibiotic exposure [21]. This technology was instrumental in demonstrating that many persisters from exponential growth phases are actually growing cells before treatment, a hallmark of Type II and III persistence [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Relevance to Persister Research |

|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Devices (e.g., MCMA) | Single-cell confinement and long-term imaging [21] | Visualizing lineage histories and heterogeneous responses of Types I, II, and III persisters. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins (e.g., GFP, mCherry) | Tagging and visualizing specific proteins or promoter activities. | Monitoring stress response pathways (e.g., RpoS) and metabolic activity in real-time. |

| Flow Cytometry | Multi-parameter analysis of single cells in a liquid suspension. | Quantifying physiological states (e.g., membrane potential, respiratory activity) in a recovering persister population [24]. |

| Carbon-13 (¹³C) Labeled Metabolites | Tracing metabolic flux through biochemical pathways. | Profiling the active metabolism in persister cells (e.g., in S. aureus) [23]. |

| Lethal-dose Antibiotics (e.g., Amp, CPFX) | Selective killing of non-persister cells. | Isolating and enriching the persister subpopulation from a larger culture for downstream analysis [21]. |

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for isolating and analyzing persister cells, from initial culture to single-cell resolution.

The distinct characteristics of Type I, II, and III persisters necessitate tailored therapeutic approaches. A one-size-fits-all strategy is unlikely to succeed. For instance, Type I persisters, being deeply dormant, may be best targeted by direct-killing agents like membrane-disrupting compounds (e.g., synthetic cation transporters, antimicrobial peptides) or compounds that induce uncontrolled protein degradation (e.g., ADEP4) [2] [3]. In contrast, Type II and III persisters, which may retain some metabolic activity, could be vulnerable to "Wake and Kill" strategies that use metabolite adjuvants to re-sensitize them to conventional antibiotics [8].

Combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple persister types and active populations are the most promising path forward. For example, pairing an antibiotic with a membrane-permeabilizing agent can enhance drug uptake and kill a broader range of persisters [2] [3]. Furthermore, understanding the specific triggers and molecular pathways of each persister type opens the door to inhibitors that prevent their formation in the first place, such as quorum sensing inhibitors or molecules that reduce (p)ppGpp accumulation [2] [3].

In conclusion, the classification of persisters into Types I, II, and III provides an essential framework for understanding their metabolic diversity and complex biology. This refined understanding is pivotal for guiding the development of novel diagnostic tools and therapeutic regimens. Future research focusing on the precise metabolic vulnerabilities of each persister type, especially within the complex environment of biofilms and host tissues, will be critical for winning the battle against persistent bacterial infections.

The Anti-Persister Arsenal: From Direct Killing to Synergistic Approaches

Persister cells, which are dormant, non-dividing phenotypic variants found within bacterial populations and tumors, represent a major therapeutic challenge. Their low metabolic activity allows them to tolerate conventional treatments that target rapidly dividing cells or active growth processes. Direct killing strategies have emerged as a promising approach to eradicate these persistent cells by targeting fundamental, growth-state-independent cellular structures and processes. Unlike conventional antibiotics or chemotherapies, these strategies aim to disrupt essential cellular integrity or cause irreversible damage regardless of the target cell's metabolic state.

The most prominent direct killing approaches focus on two key areas: compromising the structural integrity of the cell membrane and disrupting essential cellular processes that remain active even in dormant cells. These strategies are particularly valuable because they do not require the target cells to be in an active growth phase, bypassing the primary mechanism of persister tolerance. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these direct killing methodologies, examining their mechanisms, experimental validation, and relative performance across different persister cell models.

Membrane-Targeting Strategies

Mechanisms of Membrane Disruption

The cell membrane serves as a fundamental barrier maintaining cellular integrity, making it an attractive target for direct killing approaches. Membrane-targeting agents exert their effects through several distinct mechanisms that compromise membrane function and structure:

Electrostatic Interaction and Disruption: Many membrane-targeting compounds exploit differences in membrane composition between target and host cells. Bacterial membranes contain abundant negatively charged phospholipids like phosphatidylglycerol (PG) and cardiolipin in their outer leaflets, while cancer cells expose phosphatidylserine (PS) and other anionic molecules externally. Cationic antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and synthetic membrane-targeting agents selectively interact with these negatively charged membranes through electrostatic attraction, leading to membrane disruption [25]. This interaction can cause depolarization, increased permeability, and eventual cell lysis.

Physical Membrane Perturbation: Beyond electrostatic interactions, many membrane-targeting agents incorporate hydrophobic regions that penetrate the lipid bilayer's interior. This penetration can lead to the formation of pores, membrane thinning, or complete dissolution of membrane integrity. The resulting loss of membrane potential and leakage of cellular contents proves rapidly lethal to both bacterial and cancer persister cells [25] [3].

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation: Some membrane-targeting approaches, including certain photosensitizers used in nanodynamic therapies, generate lethal levels of reactive oxygen species upon activation. These ROS oxidize membrane lipids and proteins, amplifying the initial membrane damage and leading to comprehensive cellular destruction [26].

Key Membrane-Targeting Agents and Their Efficacy

Table 1: Comparison of Membrane-Targeting Agents Against Persister Cells

| Agent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Target | Reported Efficacy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cationic Peptides & Mimetics | 2D-24, AM-0016, IMT-P8 | Bacterial membrane integrity | Effective against S. aureus and E. coli persisters [2] | Potential toxicity to mammalian cells |

| Small Molecule Membrane Disruptors | XF-70, XF-73, SA-558 | Bacterial membrane potential | Kills non-dividing S. aureus cells; SA-558 disrupts homeostasis [2] [3] | Limited spectrum for some compounds |

| Nanoparticle Systems | Hb-Naf@RBCM NPs, C-AgND | Multiple membrane components | Effective against S. aureus persisters in biofilms [2] [3] | Complex manufacturing and characterization |

| Anticancer Peptides | Various cationic peptides | Exposed PS on cancer cells | Induces cytoplasmic leakage and ROS in cancer cells [25] | Selectivity challenges based on membrane charge differences |

| Nanodynamic Therapy | Photosensitizer-loaded CNPs | General membrane integrity | ROS generation under external energy source [26] | Requires external activation energy |

The diversity of membrane-targeting approaches reflects the adaptability of this strategy across different persister cell types. For bacterial persisters, synthetic compounds like XF-70 and XF-73 have demonstrated particular efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus by disrupting membrane integrity even in slow-growing and non-dividing cells [2] [3]. Similarly, SA-558 functions as a synthetic cation transporter that disrupts bacterial homeostasis, ultimately leading to autolysis of persister cells [3].

In anticancer applications, membrane-targeting strategies leverage the differential composition of cancer cell membranes, particularly the external exposure of phosphatidylserine, which is typically confined to the inner leaflet in healthy cells [25]. This fundamental difference in membrane architecture enables selective targeting of cancer persisters while minimizing damage to normal cells.

Advanced nanoparticle systems represent a convergence of these approaches, combining membrane-targeting capabilities with enhanced delivery mechanisms. For instance, red blood cell membrane-coated nanoparticles (Hb-Naf@RBCM NPs) incorporating naftifine and oxygenated hemoglobin have demonstrated effective killing of S. aureus persisters, including those embedded in biofilms [2]. Similarly, cationic silver nanoparticle-shelled nanodroplets (C-AgND) interact with negatively charged components of the extracellular polymeric substance, enabling effective penetration and killing of persisters within biofilms [3].

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of membrane-targeting agents showing common pathways to cell disruption. The diagram illustrates how cationic agents exploit differences in membrane composition between bacterial and cancer cells, leading to various disruptive mechanisms and ultimately cell lysis.

Targeting Essential Cellular Processes

Disruption of Critical Enzymes and Protein Homeostasis

While membrane targeting represents a physical approach to persister eradication, complementary strategies focus on disrupting essential cellular processes that remain vulnerable even in dormant cells. These approaches target fundamental biochemical pathways and protein homeostasis mechanisms that persister cells must maintain to survive and eventually resuscitate:

Protein Degradation Pathway Activation: Certain direct killing agents hijack or activate cellular proteolytic machinery to cause uncontrolled protein degradation. ADEP4, a semi-synthetic acyldepsipeptide, represents a promising example that binds to the ClpP protease and induces conformational changes. This activation enables ATP-independent protein degradation, resulting in the breakdown of hundreds of intracellular proteins, including metabolic enzymes essential for persister wake-up and recovery [2] [3]. The destruction of these essential components renders persister cells incapable of resuming growth even after favorable conditions return.

Enzyme Targeting in Metabolic Pathways: Pyrazinamide, a frontline tuberculosis therapeutic, demonstrates effective targeting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persisters through a multi-faceted mechanism. Its active form, pyrazinoic acid, disrupts membrane energetics while also binding to PanD, an enzyme essential for coenzyme A biosynthesis. This binding triggers degradation of PanD by the ClpC1-ClpP complex, effectively disrupting multiple cellular processes simultaneously [3]. The multi-target nature of this approach reduces the likelihood of resistance development.

Interference with Death Pathway Signaling: Recent cancer research has revealed a paradoxical mechanism where surviving persister cells hijack enzymes typically associated with cell death to facilitate their regrowth. In models of melanoma, lung, and breast cancers, persister cells that survive initial treatment display chronic, low-level activation of DNA fragmentation factor B (DFFB), an enzyme normally involved in DNA fragmentation during apoptosis. At sublethal levels, this DFFB activation interferes with growth-suppressing signals like interferon signaling, enabling persister cell regrowth. Notably, removing DFFB keeps cancer persister cells dormant and prevents regrowth during drug treatment, identifying this non-essential enzyme in normal cells as a promising target for combination therapies [27].

Energy and Metabolic Pathway Disruption

Beyond direct enzyme targeting, disruption of cellular energy management and metabolic pathways presents another viable strategy for persister elimination:

Membrane Energetics Disruption: Several effective persister control agents operate by compromising bacterial membrane energetics and proton motive force (PMF). Compounds like pinaverium bromide (PB) disrupt PMF and generate reactive oxygen species, effectively undermining the delicate energy balance that persister cells maintain despite their dormant state [3]. Similarly, nitric oxide (NO) acts as a metabolic disruptor, interfering with energy production pathways essential for persister maintenance and eventual resuscitation [2].

Metabolic Cofactor Depletion: The targeted degradation of metabolic cofactors and essential small molecules represents another effective strategy. As demonstrated in the pyrazinamide/PanD mechanism, disrupting the biosynthesis of coenzyme A through PanD degradation effectively starves persister cells of essential metabolic cofactors, preventing their recovery and eventual proliferation [3].

Table 2: Agents Targeting Essential Cellular Processes in Persister Cells

| Agent Category | Specific Examples | Cellular Target | Mechanism of Action | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease Activators | ADEP4 | ClpP protease | Causes conformational change enabling ATP-independent protein degradation [2] [3] | Broad-spectrum antibacterial |

| Metabolic Disruptors | Pyrazinamide/Pyrazinoic acid | Membrane energetics & PanD enzyme | Disrupts membrane potential and triggers PanD degradation [3] | Mycobacterium tuberculosis persisters |

| Death Pathway Exploiters | DFFB inhibition | DNA fragmentation factor B | Blocks sublethal death signaling that promotes regrowth [27] | Melanoma, lung, and breast cancer persisters |

| Energy Pathway Disruptors | Pinaverium bromide (PB) | Proton motive force (PMF) | Disrupts PMF and generates ROS [3] | Bacterial persister control |

| Metabolic Modulators | Nitric oxide (NO) | Multiple metabolic enzymes | Acts as metabolic disruptor [2] | Reduces persister formation |

The strategic targeting of essential cellular processes offers the advantage of exploiting vulnerabilities that persister cells cannot easily circumvent through dormancy alone. Unlike conventional treatments that require active cellular processes, these approaches recognize that dormant cells must still maintain basic homeostasis and preserve the machinery necessary for eventual resuscitation.

Diagram 2: Strategies for targeting essential cellular processes in persister cells, showing three primary approaches and their outcomes.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Assays for Evaluating Direct Killing Efficacy

Robust experimental protocols are essential for accurately assessing the efficacy of direct killing strategies against persister cells. The following methodologies represent standardized approaches used across the field:

Persister Cell Isolation and Enrichment:

- High-Dose Antibiotic Selection: Bacterial persisters are typically isolated by treating mid-log phase cultures with high concentrations of bactericidal antibiotics (e.g., 10-100× MIC of fluoroquinolones or aminoglycosides) for 3-6 hours, followed by extensive washing to remove the antibiotics and dead cells [2] [3]. This approach enriches for the non-growing, tolerant persister subpopulation.

- Drug Selection in Cancer Models: Cancer persister cells are often generated by exposing sensitive cell lines to targeted therapies (e.g., EGFR inhibitors for NSCLC, BRAF inhibitors for melanoma) at clinically relevant concentrations for 7-14 days. The surviving population, typically representing 0.1-5% of the original culture, is characterized as drug-tolerant persisters [1].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): For more precise isolation, dye-based staining (e.g., membrane potential-sensitive dyes, efflux pump substrates) can be employed to distinguish and sort persister subpopulations based on their reduced metabolic activity [1].

Membrane Integrity and Viability Assessment:

- Membrane Permeability Assays: SYTOX Green and propidium iodide uptake are standard methods for evaluating membrane integrity. These fluorescent dyes are excluded from viable cells but penetrate and bind nucleic acids in membrane-compromised cells, providing quantitative assessment of membrane disruption [2] [25].

- CFU Enumeration: The gold standard for assessing bacterial persister killing involves determining colony-forming units (CFU) before and after treatment. True persister eradication is demonstrated by a ≥3-log reduction in viable counts after direct killing treatment [3].

- ATP Content Measurement: Cellular ATP levels, measured via luciferase-based assays, provide a sensitive indicator of metabolic activity and cell viability following treatment with membrane-targeting agents [1].

Time-Kill Kinetics Analysis: Comprehensive time-kill assays are essential for distinguishing between bactericidal/cytotoxic activity and true persister eradication. These experiments typically monitor viability over 24-72 hours, with effective direct killing agents demonstrating rapid, concentration-dependent reduction in viable counts without regrowth upon drug removal [2] [3].

Advanced Mechanistic Studies

Understanding the specific mechanisms of action for direct killing agents requires specialized experimental approaches:

- Membrane Depolarization Measurements: The fluorescent dye 3,3'-diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC₂(3)) is commonly used to monitor changes in membrane potential following treatment with membrane-targeting agents. Flow cytometric analysis of stained cells provides quantitative assessment of membrane depolarization [25].

- Reactive Oxygen Species Detection: Intracellular ROS generation can be quantified using fluorescent probes such as 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H₂DCFDA) or dihydroethidium (DHE). Increased fluorescence following treatment indicates ROS production, which often contributes to the lethal effects of membrane-targeting agents [26].

- Protein Degradation Monitoring: For agents like ADEP4 that activate proteolytic systems, western blot analysis of specific protein substrates (e.g., FabD, PanB) over time provides direct evidence of uncontrolled protein degradation [3].

- Electron Microscopy: Transmission and scanning electron microscopy offer visual evidence of membrane damage, including blebbing, pore formation, and complete membrane disintegration following treatment with membrane-targeting agents [25].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Efficacy Across Persister Cell Types

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Direct Killing Strategies Against Different Persister Cell Types

| Strategy Category | Bacterial Persisters | Cancer DTP Cells | Biofilm-Embedded Persisters | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane-Targeting Agents | Highly effective against Gram-positive pathogens; variable against Gram-negative [2] [3] | Moderate efficacy, dependent on membrane charge differences [25] | Good penetration and efficacy against biofilm populations [2] | Rapid killing; independence from metabolic state | Potential toxicity to host cells; variable spectrum |

| Protease Activators | Broad-spectrum activity against Gram-positive bacteria [3] | Limited direct evidence in cancer models | Reduced activity in biofilm environments | Novel mechanism; low resistance potential | Pharmacokinetic challenges; limited spectrum |

| Metabolic Disruptors | Species-specific (e.g., pyrazinamide for Mtb) [3] | Emerging evidence for cancer metabolic dependencies [1] | Variable efficacy based on biofilm metabolism | High selectivity for specific pathogens | Narrow spectrum; context-dependent efficacy |

| Nanoparticle Systems | Enhanced targeting and penetration [2] [3] | Promising for targeted delivery to cancer DTPs [28] [29] | Superior penetration and retention in biofilms [2] | Multifunctional platforms; enhanced targeting | Complex manufacturing; potential immunogenicity |

| Signaling Interference | Limited application in bacterial systems | Highly specific for cancer DTP pathways [27] | Not typically applied | High specificity for persistence mechanisms | Limited to specific cancer types with defined pathways |

The comparative analysis reveals that membrane-targeting strategies generally offer broader applicability across different persister cell types, while approaches targeting essential cellular processes tend to demonstrate more specific, context-dependent efficacy. For bacterial persisters, direct membrane disruption consistently shows robust activity, particularly against Gram-positive pathogens, with agents like XF-73 and SA-558 demonstrating potent killing against Staphylococcus aureus persisters [2] [3].

In anticancer applications, the recently discovered DFFB mechanism represents a paradigm shift in persister targeting, focusing not on direct killing but on preventing the regrowth of survived persister cells [27]. This approach highlights the importance of understanding the unique biology of cancer persisters, which may leverage sublethal activation of typically lethal pathways to facilitate their survival and recurrence.

Nanoparticle-based delivery systems enhance both membrane-targeting and essential process-disrupting strategies by improving drug delivery to persistent cell populations. Cancer cell membrane-coated nanoparticles (CCM-NPs), for instance, leverage homologous targeting to selectively accumulate in tumor tissues, while also preserving immune evasion proteins that prolong circulation time [28]. Similarly, red blood cell membrane-coated nanoparticles (RBCM) demonstrate extended circulation and enhanced tumor accumulation, improving the delivery of encapsulated therapeutic agents to persister cell populations [29].

Resistance Development and Safety Profiles

A critical consideration in evaluating direct killing strategies is their potential for resistance development and associated safety profiles:

Resistance Development: Membrane-targeting agents generally demonstrate lower resistance potential compared to conventional antibiotics, as the target (cell membrane) cannot be easily modified through single genetic mutations. However, bacteria can develop resistance through membrane composition alterations, efflux pump upregulation, and membrane repair mechanisms [25]. Strategies targeting essential cellular processes like ADEP4-activated protein degradation show particularly low resistance frequencies in laboratory studies, making them attractive for persistent infection treatment [3].