Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT): A Comprehensive Guide for Predictive Modeling in Medical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) for predictive modeling in medical and pharmaceutical research.

Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT): A Comprehensive Guide for Predictive Modeling in Medical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) for predictive modeling in medical and pharmaceutical research. It covers foundational concepts, explores major algorithm implementations like XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost, and details their application to biomedical data. The guide offers practical strategies for hyperparameter tuning and overcoming class imbalance, and presents evidence-based performance comparisons with traditional machine learning and deep learning methods. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource aims to equip practitioners with the knowledge to effectively leverage GBDT for tasks ranging from drug-target interaction prediction to molecular property modeling and medical diagnosis.

Understanding GBDT: Core Principles and Why It Excels with Biomedical Data

Ensemble methods represent a powerful paradigm in machine learning, designed to improve generalizability and robustness over a single estimator by combining the predictions of several base estimators [1]. The fundamental principle underpinning ensemble learning is the concept of a "wisdom of crowds" effect, where a collection of weak learners—models that perform only slightly better than random guessing—can be strategically combined to form a single, strong predictive model with superior performance characteristics. This approach has demonstrated remarkable success across diverse domains, particularly in handling complex, real-world data where individual models may capture only partial patterns or relationships.

Within the spectrum of ensemble techniques, Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) has emerged as a particularly influential algorithm, especially for tabular data problems common in scientific research [1]. GBDT generalizes the concept of boosting by allowing optimization of an arbitrary differentiable loss function, creating a powerful predictive model in the form of an ensemble of weak prediction models, typically decision trees [2]. The algorithm operates through a sequential training process where each new tree is fit to the residual errors of the previous ensemble, gradually reducing prediction error through this iterative refinement process. In drug discovery and development, where the success rate from phase I clinical trials to drug approvals remains critically low (approximately 6.2%), machine learning approaches like GBDT offer promising avenues for improving decision-making and reducing costly late-stage failures [3].

Theoretical Foundation of GBDT

Algorithmic Framework and Mathematical Formulation

The GBDT algorithm builds upon the concept of functional gradient descent, where the model is constructed sequentially by adding weak learners that point in the negative gradient direction of the loss function. The fundamental algorithm can be formalized as follows [2]:

Given a training set ( T = {(x1, y1), (x2, y2), \dots, (xN, yN)} ) where ( xi \in X \subseteq R^n ) and ( yi \in Y \subseteq R ), the goal is to find an approximation ( \hat{F}(x) ) that minimizes the expected value of a loss function ( L(y, F(x)) ):

[ \hat{F} = \arg\min{F} E{x,y}[L(y, F(x))] ]

The GBDT approach assumes a real-valued output and constructs an approximation ( \hat{F}(x) ) as a weighted sum of weak learners ( h_m(x) ) from a family ( \mathcal{H} ), typically decision trees:

[ \hat{F}(x) = \sum{m=1}^{M} \gammam h_m(x) + \text{const} ]

The model is built sequentially in stages for ( m \geq 1 ):

[ Fm(x) = F{m-1}(x) + \left( \arg\min{hm \in \mathcal{H}} \left[ \sum{i=1}^{n} L(yi, F{m-1}(xi) + hm(xi)) \right] \right)(x) ]

In practice, instead of directly finding the best function ( hm ), each ( hm ) is fit to the pseudo-residuals, which point in the negative gradient direction [2]:

[ Fm(x) = F{m-1}(x) - \gamma \sum{i=1}^{n} \nabla{F{m-1}} L(yi, F{m-1}(xi)) ]

where ( \gamma > 0 ) is a step size, typically determined via line search:

[ \gammam = \arg\min{\gamma} \sum{i=1}^{n} L\left(yi, F{m-1}(xi) - \gamma \nabla{F{m-1}} L(yi, F{m-1}(x_i)) \right) ]

The GBDT Workflow

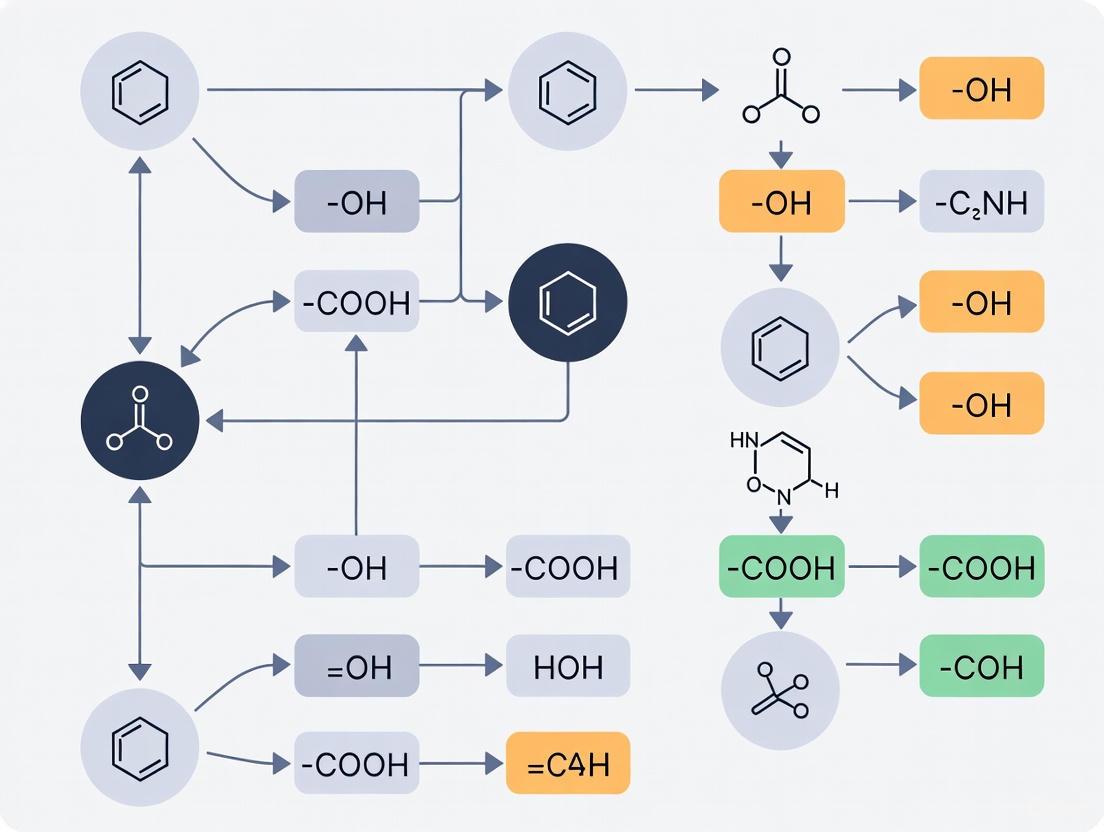

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow of the GBDT algorithm, showing how weak learners are iteratively added to minimize the residual errors of the ensemble:

GBDT Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Predictive Modeling for Drug Safety and Toxicity

GBDT has demonstrated significant utility in predicting drug safety profiles, a critical challenge in pharmaceutical development. Researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have developed multiple predictive machine learning models, including GBDT-based approaches, to identify chemical and structural drug features likely to cause toxic effects in humans [4]. These tools estimate how a drug may impact diverse outcomes of interest to drug developers, including general cellular health, pharmacokinetics, and heart and liver function.

For drug-induced cardiotoxicity (DICT) and drug-induced liver injury (DILI)—two major causes of post-market drug withdrawals—GBDT models have been trained on FDA-curated datasets to predict toxicity using chemical structure, physicochemical properties, and pharmacokinetic parameters as inputs [4]. The DICTrank Predictor represents the first predictive model of the FDA's DICT ranking list, while the DILIPredictor successfully differentiates toxicity between species, correctly predicting when compounds would be safe in humans even if toxic in animals.

Drug Response Prediction in Patient-Derived Models

GBDT algorithms have shown excellent performance in predicting drug responses in patient-derived cell culture models, facilitating personalized medicine approaches in oncology. In a recent study, researchers employed a random forest model (a related ensemble method) with 50 trees as part of a recommender system to predict drug sensitivities for patient-derived cell lines through analysis of historical profiles of cell lines derived from other patients [5]. The prototype demonstrated excellent performance, with high correlations between predicted and actual drug activities (Rpearson = 0.874, Rspearman = 0.883 for all drugs; Rpearson = 0.781, Rspearman = 0.791 for selective drugs).

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Drug Response Prediction Using Ensemble Methods [5]

| Metric | All Drugs | Selective Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| Rpearson | 0.874 ± 0.002 | 0.781 ± 0.003 |

| Rspearman | 0.883 ± 0.002 | 0.791 ± 0.003 |

| Top-10 Accuracy | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.2 |

| Top-20 Accuracy | 15.26 ± 0.3 | 10.5 ± 0.3 |

| Top-30 Accuracy | 22.65 ± 0.4 | 17.6 ± 0.4 |

| Hit Rate in Top-10 | 9.8 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.2 |

Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction

The GBDT+LR model, which combines Gradient-Boosting Decision Trees with Logistic Regression, has been successfully applied to cardiovascular disease prediction, demonstrating the versatility of GBDT-based approaches in healthcare applications [6]. This hybrid approach addresses the weak feature combination ability of LR in handling nonlinear data by using GBDT to automatically perform feature combination and screening, then feeding the newly generated discrete feature vector into the LR model.

In experimental comparisons using the UCI cardiovascular disease dataset, the GBDT+LR model outperformed other common disease classification algorithms across multiple evaluation metrics [6]. The model achieved an accuracy of 78.3%, compared to 71.5% for Random Forest, 69.3% for Support Vector Machine, 71.4% for Logistic Regression, and 72.4% for GBDT alone, demonstrating the advantage of the combined approach.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Cardiovascular Disease Prediction Models [6]

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Specificity | F1 Score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBDT+LR | 78.3% | 79.1% | 80.2% | 77.8% | 0.851 |

| GBDT | 72.4% | 73.2% | 74.1% | 71.9% | 0.798 |

| Random Forest | 71.5% | 72.8% | 73.5% | 70.8% | 0.789 |

| Logistic Regression | 71.4% | 70.9% | 72.1% | 70.5% | 0.781 |

| Support Vector Machine | 69.3% | 70.2% | 71.3% | 68.7% | 0.762 |

Implementation Protocols for GBDT in Predictive Modeling

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

The foundation of any successful GBDT implementation lies in rigorous data preprocessing. For biomedical applications, the following protocol is recommended:

Missing Value Handling: GBDT implementations like HistGradientBoosting in scikit-learn have built-in support for missing values (NaNs), which avoids the need for a separate imputer [1]. During training, the tree grower learns at each split point whether samples with missing values should go to the left or right child based on potential gain.

Categorical Feature Encoding: Native categorical feature support in GBDT algorithms often outperforms one-hot encoding [1]. To enable categorical support, a boolean mask can be passed to the categoricalfeatures parameter, indicating which feature is categorical. The cardinality of each categorical feature must be less than the maxbins parameter (typically 255).

Outlier Detection and Treatment: For clinical and biomedical data, use statistical methods like the double interquartile range (IQR) for outlier detection [6]. For each numerical attribute, calculate IQR as the difference between the 75th percentile (Q3) and 25th percentile (Q1). Data points exceeding Q1 - step × IQR or Q3 + step × IQR are considered outliers, where step controls detection strictness.

Model Training and Hyperparameter Optimization

The GBDT training process requires careful attention to hyperparameter selection to balance model complexity and generalization:

Table 3: Key Hyperparameters for GBDT Models and Their Impact on Performance

| Hyperparameter | Description | Recommended Setting | Impact on Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| n_estimators | Number of sequential trees to train | 100-500 | Higher values can lead to overfitting; requires early stopping |

| learning_rate | Shrinks the contribution of each tree | 0.01-0.1 | Lower values require more trees but often generalize better |

| max_depth | Maximum depth of individual trees | 3-8 | Controls complexity; shallower trees promote generalization |

| minsamplesleaf | Minimum samples required at leaf node | 5-20 | Higher values prevent overfitting to noise |

| max_bins | Number of bins used for histogram-based boosting | 255 | Lower values act as regularization |

| l2_regularization | Regularization term in the loss function | 0.1-1.0 | Prevents overfitting by penalizing large leaf values |

Model Validation and Interpretation

For robust model evaluation in biomedical contexts:

Stratified Cross-Validation: Implement stratified k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5 or k=10) to ensure representative distribution of classes across folds, particularly important for imbalanced biomedical datasets.

Multiple Metric Assessment: Beyond accuracy, evaluate models using domain-relevant metrics including precision, recall, F1-score, AUC-ROC, and AUC-PR [6]. For clinical applications, sensitivity and specificity provide critical insights into diagnostic capability.

Feature Importance Analysis: Leverage GBDT's inherent feature importance calculations (typically based on mean decrease in impurity or permutation importance) to identify biologically relevant predictors and validate model decisions against domain knowledge.

SHAP Value Interpretation: Apply SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to understand feature contributions to individual predictions, enhancing model transparency for clinical and regulatory applications [6].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GBDT Implementation

Table 4: Key Computational Tools and Libraries for GBDT Research

| Tool/Library | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn | Machine learning library | General-purpose GBDT implementation | User-friendly API, extensive documentation [1] |

| HistGradientBoosting | Histogram-based GBDT | Large datasets (>10,000 samples) | Faster training, native missing value support [1] |

| XGBoost | Optimized GBDT implementation | High-performance demanding applications | Handles high-dimensional sparse features well [7] |

| LightGBM | Gradient boosting framework | Large-scale data with categorical features | Faster training speed, lower memory usage [1] |

| SHAP | Model interpretation | Explainable AI for biomedical applications | Unpacks black-box model predictions [6] |

| CellProfiler | Image analysis software | Cellular feature extraction for drug discovery | Quantifies morphological features for model inputs [4] |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Deep learning frameworks | Neural network integration with GBDT | Enables complex hybrid modeling approaches [3] |

Gradient Boosting Decision Trees represent a powerful realization of the ensemble principle, transforming collections of weak learners into strong predictive models capable of addressing complex challenges in drug discovery and biomedical research. Through its sequential error-correction approach and flexibility in handling diverse data types, GBDT has demonstrated significant utility across multiple domains—from predicting drug toxicity and patient-specific treatment responses to assessing cardiovascular disease risk.

The continued refinement of GBDT algorithms, including histogram-based implementations for computational efficiency and native support for missing values and categorical features, further enhances their applicability to real-world biomedical problems where data imperfections are common. As the field advances, the integration of GBDT with interpretability frameworks like SHAP and its combination with other modeling approaches (e.g., GBDT+LR) will be crucial for building trust and facilitating adoption in clinical and regulatory contexts.

For researchers in drug development, GBDT offers a robust toolkit for tackling the pervasive challenge of attrition in the drug development pipeline, potentially contributing to more efficient target validation, compound optimization, and patient stratification strategies. By leveraging the ensemble principle to transform weak learners into strong predictors, GBDT continues to expand the boundaries of predictive capability in biomedical science.

Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) represent a powerful machine learning technique within the broader context of predictive model research for scientific applications, including drug development and medium prediction. As an ensemble method, GBDT creates a strong predictive model by combining multiple weak learners—typically shallow decision trees—in a sequential fashion where each new model focuses on correcting the errors made by its predecessors [8]. This iterative corrective learning framework enables GBDT to capture complex, non-linear relationships in data, making it particularly valuable for research datasets with intricate interaction effects [9]. The fundamental principle underlying GBDT is boosting, which involves iteratively adding trees that correct the residual errors of the current ensemble, thereby progressively improving prediction accuracy through a gradient descent optimization procedure [2] [10]. Unlike bagging methods like Random Forests that build trees independently and in parallel, GBDT constructs trees sequentially, with each tree learning from the mistakes of previous trees [8]. This sequential error-correction mechanism, framed within a functional gradient descent approach, allows GBDT to achieve state-of-the-art performance on diverse prediction tasks common in scientific research.

Mathematical Foundation of Sequential Learning

Core Algorithmic Framework

The GBDT framework seeks to approximate a function F*(x) that maps input features to output variables by minimizing the expected value of a differentiable loss function L(y, F(x)) [10]. The algorithm builds this approximation iteratively through an additive model of the form:

- Initialization: The algorithm begins with an initial base model, typically a constant value that minimizes the overall loss function. For regression with mean squared error loss, this is simply the mean of the target values: F₀(x) = mean(y) [11].

- Additive Expansion: The model is improved iteratively by adding new weak learners: Fm(x) = Fm-1(x) + ν · ρmhm(x), where hm(x) represents the new weak learner added at iteration m, ρm is its weight, and ν is the learning rate or shrinkage parameter that controls the contribution of each tree [10].

- Gradient Optimization: At each iteration m, the algorithm computes the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the current prediction Fm-1(x). These negative gradients, known as pseudo-residuals, are given by: rmi = - [∂L(yi, F(xi))/∂F(xi)] for i = 1,2,...,N [10].

For the commonly used mean squared error loss function L = ½(yi - F(xi))², the negative gradient simplifies to the ordinary residual: rmi = yi - Fm-1(xi) [11]. This special case demonstrates how GBDT generalizes the concept of residual fitting to accommodate arbitrary differentiable loss functions.

Key Mathematical Insights

The GBDT training process essentially performs gradient descent in function space [12]. Each new weak learner (decision tree) represents a step in the direction of the negative gradient of the loss function. The line search parameter ρm is determined by solving an optimization problem: ρm = argminρ Σi=1N L(yi, Fm-1(xi) + ρhm(xi)) [10]. This mathematical foundation provides GBDT with exceptional flexibility, as it can be adapted to various problem types (regression, classification, ranking) simply by changing the loss function, while maintaining the same core sequential learning procedure [2].

Step-by-Step Sequential Learning Mechanism

Initialization Phase

The GBDT sequential learning process begins with initialization of a simple base model:

- Base Model Construction: Initialize with a constant prediction that minimizes the overall loss function. For regression with mean squared error (MSE) loss, this is the mean of all target values: F₀(x) = ȳ [11]. This serves as the initial "blurry guess" before refinements [12].

- Initial Residual Calculation: Compute the difference between actual values and this initial prediction for all training samples. For MSE loss, these initial residuals are simply: residual₀ = yi - ȳ for all i [13].

Iterative Correction Process

The core sequential learning unfolds through repeated cycles of error measurement and correction:

- Residual Computation: At each iteration m, calculate the pseudo-residuals (negative gradients) of the loss function with respect to the current ensemble prediction Fm-1(x) [10]. For MSE loss, this remains: residualm = yi - Fm-1(xi) [13].

- Weak Learner Training: Train a new decision tree hm(x) to predict these pseudo-residuals from the input features [2]. The tree is typically constrained in size (e.g., limited depth of 3-8 nodes) to ensure it remains a weak learner [14].

- Leaf Node Calculation: For each terminal node (leaf) in the new tree, compute the optimal output value that minimizes the loss function for observations falling into that leaf. For MSE loss, this is typically the mean of the residuals in that leaf [11].

- Model Update: Update the ensemble by adding this new tree's predictions, scaled by the learning rate: Fm(x) = Fm-1(x) + ν · hm(x) [10]. The learning rate ν (typically between 0.01-0.1) controls each tree's contribution and prevents overfitting [14].

- Stopping Criteria Check: Repeat steps 1-4 until a predefined number of iterations is reached, or until validation performance stops improving (early stopping) [8].

Table 1: GBDT Sequential Learning Parameters and Their Roles

| Parameter | Typical Values | Impact on Sequential Learning | Research Application Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Trees | 100-1000 [14] | Controls model complexity; too few underfits, too many overfits [13] | Use early stopping with validation set to determine optimal number [8] |

| Learning Rate | 0.01-0.1 [14] | Scales contribution of each tree; smaller values require more trees but often yield better generalization [12] | Balance with number of trees; smaller learning rates with more trees often optimal [8] |

| Tree Depth | 3-8 [14] | Controls interaction capture; deeper trees capture more complex patterns but risk overfitting [8] | Start with depth of 3-6 for balanced performance [14] |

| Subsample Ratio | 0.5-1.0 | Fraction of data used for each tree; values <1.0 introduce randomness that reduces overfitting [15] | Useful for large datasets; improves diversity of sequential corrections [15] |

Visualizing the Sequential Learning Process

The sequential error correction mechanism of GBDT can be visualized through the following workflow:

GBDT Sequential Error Correction Workflow

The diagram illustrates the two-phase learning process of GBDT. The initialization phase establishes a baseline model, while the iterative correction phase repeatedly trains new trees on the errors of the current ensemble, with each iteration refining the model's predictions. The feedback loop demonstrates how information about previous errors guides subsequent learning steps, embodying the core sequential error-correction mechanism.

Experimental Protocols for GBDT Implementation

Basic GBDT Training Protocol

For researchers implementing GBDT for predictive modeling tasks:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize numerical features and encode categorical variables. GBDT can handle missing values through surrogate splits in trees [8].

- Parameter Initialization: Set initial parameters based on dataset size and complexity: learning rate (ν=0.1), number of trees (M=100), tree depth (3-6), and subsampling ratio (0.8-1.0) [14].

- Model Training Loop:

- Compute initial predictions F₀(x) as mean(y) for regression or log(odds) for classification

- For m = 1 to M:

- Compute pseudo-residuals: rmi = - [∂L(yi, F(xi))/∂F(xi)] for i = 1,...,N

- Train decision tree hm(x) of specified depth on {xi, rmi}

- Compute optimal leaf values γjm for each terminal node j: γjm = argminγ Σxi∈Rjm L(yi, Fm-1(xi) + γ)

- Update model: Fm(x) = Fm-1(x) + ν · Σj γjm · I(x ∈ Rjm)

- Validation Monitoring: Track performance on held-out validation set to implement early stopping [8].

Advanced Regularization Protocol

To prevent overfitting in GBDT models:

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Systematically search optimal combinations of learning rate, tree depth, and number of trees using cross-validation [13].

- Stochastic Gradient Boosting: Incorporate randomness by subsampling data (rows) and/or features (columns) for each tree [15].

- Regularization Constraints: Apply minimum samples per leaf, maximum features per split, and L1/L2 regularization to leaf values [8].

- Early Stopping Implementation: Monitor validation performance and stop training when no improvement is observed for a specified number of iterations [8].

Performance Analysis and Quantitative Comparisons

Empirical Performance Metrics

Table 2: GBDT Performance in Comparative Studies

| Application Domain | Comparison Models | Performance Outcome | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Image Segmentation [15] | Random Forests (RF) | 0.2-0.3 mm reduction in surface distance error over FreeSurfer; 0.1 mm over multi-atlas segmentation | GBDT significantly outperformed RF (p < 0.05) on all segmentation measures |

| Genomic Prediction [9] | GBLUP, BayesB, Elastic Net | Better prediction accuracy for 3/10 traits (BMD, cholesterol, glucose) with lower RMSE | GBDT excelled for traits with epistatic effects; linear models better for polygenic traits |

| General Predictive Modeling [10] | Single GBDT model | Statistically significant improvements using hybrid GBDT-clustering approach | Hybrid approach with K-means enhanced predictive power on regression datasets |

Implementation-Specific Performance

Research indicates that GBDT implementations with clustering enhancements can achieve statistically significant improvements over standard GBDT approaches according to Friedman and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests [10]. In medical image segmentation tasks, GBDT consistently outperformed Random Forest models trained on identical feature sets (p < 0.05 on all measures) [15]. For genomic prediction of complex traits in mice, GBDT showed superior performance for traits with evidence of epistatic effects, while linear models performed better for highly polygenic traits [9].

Research Applications and Case Studies

Biomedical Imaging Applications

In medical image analysis, GBDT has been successfully applied in a corrective learning framework to improve segmentation of subcortical structures (caudate nucleus, putamen, hippocampus) from MRI scans [15]. The implementation involved:

- Host Segmentation Methods: Using existing methods (FreeSurfer, multi-atlas) to generate initial segmentations

- Surface-Based Sampling: Constructing candidate locations around initial segmentation boundaries

- Feature Engineering: Extracting spatial coordinates, image intensities, gradient magnitudes, and texture features

- GBT Correction: Training GBDT models to predict the true boundary location from features, significantly reducing systematic errors of host methods

This approach achieved mean reduction in surface distance error of 0.2-0.3 mm for FreeSurfer and 0.1 mm for multi-atlas segmentation [15].

Genomic Prediction Applications

GBDT has demonstrated particular value in genomic prediction for traits with non-additive genetic architectures [9]. In diversity outbred mice populations, GBDT:

- Outperformed Linear Models for traits with epistatic effects (bone mineral density, cholesterol, glucose)

- Handled Feature Interactions automatically without explicit specification

- Provided Feature Importance rankings to identify relevant markers

- Achieved Competitive Performance despite decreased connectedness between reference and validation sets

Enhanced Hybrid Approaches

Recent research has combined GBDT with clustering techniques to further improve performance [10]:

- Cluster-Specific Modeling: Applying separate GBDT models to data partitions identified by K-means or Bisecting K-means clustering

- Feature Enhancement: Using cluster centroids and distances as additional input features

- Ensemble Aggregation: Combining predictions from multiple cluster-specific GBDT models

This hybrid approach has demonstrated statistically significant improvements over single GBDT models on multiple regression datasets [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for GBDT Research Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost [15] | Optimized GBDT implementation with regularization | Medical image segmentation; general predictive modeling |

| LightGBM [16] | Gradient boosting framework with leaf-wise tree growth | Large-scale data processing; efficient handling of categorical features |

| Scikit-learn GBDT [14] | Python implementation of gradient boosting | Prototyping and comparative studies; educational applications |

| CatBoost [10] | GBDT implementation with categorical feature handling | Datasets with numerous categorical variables |

| PySpark MLlib [10] | Distributed machine learning library | Large-scale datasets requiring distributed computing |

Within the field of machine learning applied to biomedical research, Gradient Boosted Decision Trees (GBDTs) have emerged as a state-of-the-art algorithm for modeling complex tabular data, such as that prevalent in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction [17] [18]. The robustness and predictive performance of GBDTs hinge on a core mathematical intuition that is sometimes overlooked: the profound connection between loss functions, gradients, and residuals. For researchers and scientists in drug development, a deep understanding of this relationship is not merely theoretical; it is fundamental to constructing, interpreting, and optimizing predictive models that can accelerate discovery. This document elucidates this critical intuition and provides practical protocols for its application in medium-prediction research, such as predicting biological activity or molecular properties.

Core Mathematical Foundations

At its heart, gradient boosting is an ensemble technique that builds a strong predictive model by sequentially combining multiple weak learners, typically decision trees. Each new tree is trained to correct the errors of the combined ensemble of all previous trees.

The Optimization in Function Space

The goal is to find an approximation, (\hat{F}(\mathbf{x})), that minimizes the expected value of a differentiable loss function, (L(y, F(\mathbf{x}))), where (y) is the true value and (F(\mathbf{x})) is the prediction [2]. The model is constructed in an additive manner:

[ Fm(\mathbf{x}) = F{m-1}(\mathbf{x}) + \rhom hm(\mathbf{x}) ]

Here, (F{m-1}(\mathbf{x})) is the current model, (hm(\mathbf{x})) is the new weak learner, and (\rho_m) is its weight [10].

Instead of traditional parameter optimization, gradient boosting performs gradient descent in function space. The algorithm identifies a new function (hm) that points in the negative gradient direction of the loss function for the current model, (F{m-1}).

The Pivotal Link: Residuals as (Negative) Gradients

The critical intuitive leap is recognizing that for a specific, commonly used loss function, the pseudo-residuals are precisely these gradients.

For a dataset with (n) examples, the pseudo-residual for the (i)-th instance at the (m)-th stage is calculated as the negative gradient of the loss function with respect to the current prediction (F{m-1}(\mathbf{x}i)) [2] [11]:

[ r{im} = -\left[\frac{\partial L(yi, F(\mathbf{x}i))}{\partial F(\mathbf{x}i)}\right]{F(\mathbf{x})=F{m-1}(\mathbf{x})} ]

When the loss function (L) is Mean Squared Error (MSE), defined as (L(y, F(\mathbf{x})) = \frac{1}{2}(y - F(\mathbf{x}))^2), the gradient becomes:

[ \frac{\partial L}{\partial F(\mathbf{x}i)} = -(yi - F{m-1}(\mathbf{x}i)) ]

Therefore, the pseudo-residual is:

[ r{im} = -(-(yi - F{m-1}(\mathbf{x}i))) = yi - F{m-1}(\mathbf{x}_i) ]

This is the classic residual—the difference between the observed value and the predicted value [11]. Thus, in the case of MSE loss, fitting a new tree (h_m) to the "residuals" is equivalent to fitting it to the negative gradients, which is the core of the gradient descent update. This is why the concept of "learning from mistakes" is so effective and intuitive in boosting.

Table 1: Relationship Between Loss Function, Gradient, and Residual

| Loss Function | Formula | Gradient ((\frac{\partial L}{\partial F})) | Pseudo-Residual ((-\frac{\partial L}{\partial F})) | Intuition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Squed Error (MSE) | (\frac{1}{2}(y - F(\mathbf{x}))^2) | (-(y - F(\mathbf{x}))) | (y - F(\mathbf{x})) | Directly predicts the error (residual) of the current model. |

| Absolute Error (MAE) | (|y - F(\mathbf{x})|) | (-\text{sign}(y - F(\mathbf{x}))) | (\text{sign}(y - F(\mathbf{x}))) | Predicts only the direction (-1, 0, +1) of the error. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of this core mathematical relationship within a single boosting iteration.

Experimental Protocols for GBDT in Drug Research

This section outlines a practical protocol for applying GBDT to a typical problem in drug development: classifying bioactive compounds.

Protocol: Building a Bioactivity Classifier with GBDT

1. Objective: To train a GBDT model that predicts a binary biological activity endpoint (e.g., active/inactive against a specific protein target) from molecular descriptor data.

2. Materials & Data Preparation:

- Dataset: A tabular dataset where rows represent unique chemical compounds and columns represent molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices) and a binary activity label.

- Software: Python with Scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM, or CatBoost libraries [17].

- Preprocessing: Split data into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets. Standardize or normalize continuous feature descriptors.

3. Experimental Workflow: The end-to-end process for training and evaluating a GBDT model for this task is summarized below.

4. Detailed Methodology:

- Step 3 - Initialization: The initial model (F_0(\mathbf{x})) is a constant value that minimizes the overall loss. For MSE loss, this is the mean of the target variable; for binary log loss, it is the log-odds [11].

- Step 4 - Iterative Boosting:

- 4a. Compute Pseudo-Residuals: For each instance (i) in the training set, calculate the pseudo-residual (r{im}) using the formula in Section 2.2, based on the chosen loss function.

- 4b. Train Weak Learner: Train a decision tree (hm(\mathbf{x})) of limited depth (e.g., 3-6) using the feature data (\mathbf{x}i) to predict the pseudo-residuals (r{im}).

- 4c. & 4d. Update Model: For each leaf in the new tree (h_m), calculate a weight (output value) that minimizes the loss for the instances in that leaf. The model is then updated by adding this new tree, scaled by a learning rate (\nu) (e.g., 0.1), to the current ensemble [2] [10]. This process is repeated for many iterations (M).

5. Evaluation: Evaluate the final ensemble model (F_M(\mathbf{x})) on the held-out test set using domain-relevant metrics like Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) for classification or Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for regression.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Essential Tools for GBDT-based Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerically encode chemical structure for the model. | Topological, electronic, and geometric descriptors generated by tools like RDKit [17]. |

| Bioactivity Data | Serves as the labeled target variable (y) for supervised learning. | IC₅₀, Ki, or binary active/inactive labels from experimental assays. |

| Gradient Boosting Libraries | Provide optimized implementations of the GBDT algorithm. | XGBoost (generally best predictive performance), LightGBM (fastest training), CatBoost (handles categorical features) [17]. |

| Hyperparameter Tuning | Optimize model performance and prevent overfitting. | Use techniques like grid search or Bayesian optimization to tune learning rate, tree depth, and number of trees [17]. |

| Loss Function | Define the objective the model optimizes for, shaping the gradient/residual. | Binary Log-Loss (classification), MSE (regression), or custom loss functions for specialized tasks. |

Advanced Applications and Current Research

The application of GBDT in biomedical research continues to evolve, demonstrating its versatility and power. Recent studies highlight its role in complex prediction tasks:

- Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction: GBDT models are successfully integrated into modern DTI prediction frameworks. For example, NASNet-DTI uses a graph neural network to extract features from drugs and targets, then employs a GBDT as the final predictor to classify interactions, demonstrating state-of-the-art accuracy [18].

- Handling Noisy Real-World Data: Research is actively addressing challenges like label noise in tabular bioactivity data. Studies show that GBDTs are susceptible to performance degradation from mislabeled data, prompting the development of specialized data cleansing and robust learning algorithms to mitigate these effects [19].

- Performance Enhancements: Novel hybrid approaches are being explored to boost GBDT performance further. One promising method combines GBT with K-means clustering, creating an ensemble of GBT models, each trained on a distinct data cluster. This approach has shown statistically significant improvements on regression datasets [10].

The mathematical intuition linking loss functions, gradients, and residuals is the cornerstone of the GBDT algorithm. Understanding that boosting sequentially corrects errors by following the negative gradient of a loss function provides a powerful framework for researchers. This knowledge empowers scientists in drug development to make informed decisions—from selecting an appropriate loss function for their specific problem to interpreting model behavior and diagnosing issues. As a leading technique for modeling tabular data, GBDT, when grounded in a solid mathematical understanding, represents an indispensable tool in the modern computational scientist's arsenal for accelerating drug discovery and development.

In the field of medium prediction research, particularly within drug development, selecting an optimal machine learning model is paramount for achieving accurate and reliable results. For the ubiquitous tabular data, which consists of rows representing samples and columns representing features, the Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) has emerged as a dominant algorithm, often outperforming more complex deep learning (DL) architectures [20]. This application note delineates the technical superiority of GBDT for tabular data, supported by quantitative comparisons and detailed experimental protocols, providing researchers and scientists with a framework for its effective application.

Performance Comparison: GBDT vs. Deep Learning

Extensive benchmarking across various domains, including medical diagnosis, demonstrates that GBDT algorithms consistently achieve state-of-the-art performance on tabular data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison on Medical Diagnosis Tabular Datasets [20]

| Model Category | Specific Models | Average Rank Across Benchmarks | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| GBDT Models | XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost | Highest | Superior accuracy, lower computational cost, easier optimization |

| Traditional ML | SVM, Logistic Regression, k-NN | Intermediate | Simplicity, interpretability |

| Deep Learning | TabNet, TabTransformer | Lower | Potential for automatic feature engineering |

A specific clinical study on predicting postoperative atelectasis further validates GBDT's predictive power, showing its performance is comparable to, and in some aspects better than, traditional statistical models.

Table 2: Clinical Predictive Performance (AUC) on Atelectasis Dataset [21]

| Model | Training Set AUC | Validation Set AUC |

|---|---|---|

| GBDT | 0.795 | 0.776 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.763 | 0.811 |

Furthermore, GBDT's robustness is evidenced by its successful integration into complex hybrid pipelines for tasks like drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction, where it serves as a powerful final predictor using features extracted by graph neural networks [18].

Core Advantages of GBDT for Tabular Data

The performance edge of GBDT is underpinned by several intrinsic advantages over deep learning models when handling typical tabular data characteristics [20] [22] [23].

- Handles Data Heterogeneity: Tabular data features are often heterogeneous (mixed data types), weakly correlated, and lack spatial or sequential relationships. Deep learning architectures like CNNs and RNNs, designed for homogeneous, highly correlated data (like images and text), struggle to leverage their inductive biases effectively in this context. GBDT, based on decision trees, naturally partitions this heterogeneous space [20] [22].

- Robustness and Efficiency: GBDT models are highly robust, requiring minimal data preprocessing. They can natively handle missing values and high-cardinality categorical data without extensive imputation or encoding [23]. They also have a smaller hyperparameter space, are faster to train, and require significantly less computational power than deep neural networks [20] [23].

- Interpretability: While not perfectly transparent, GBDT models offer better interpretability than deep learning "black boxes." Techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) can be applied efficiently to understand feature importance, which is critical in scientific and medical fields [23].

Experimental Protocols for GBDT Implementation

Protocol: Benchmarking GBDT vs. Deep Learning on Tabular Data

Objective: To empirically compare the performance of GBDT and DL models on a specific tabular dataset. Materials: A curated tabular dataset (e.g., from a medical diagnosis or drug affinity benchmark like KIBA or BindingDB) [20] [24].

- Data Preprocessing:

- For GBDT: Perform minimal preprocessing. Handle missing values using the model's built-in method (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) or simple imputation. Encode categorical variables using label encoding.

- For DL: Perform comprehensive preprocessing, including mean/median imputation for missing values and one-hot or embedding layers for categorical variables. Standardize or normalize numerical features.

- Model Training and Tuning:

- GBDT Models (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost): Utilize a randomized or grid search to tune key hyperparameters such as

learning_rate,n_estimators,max_depth, andsubsample. Use early stopping to prevent overfitting. - DL Models (TabNet, FT-Transformer): Tune hyperparameters like

learning_rate,layer_size, andnumber_of_layers. Employ techniques like dropout and batch normalization for regularization.

- GBDT Models (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost): Utilize a randomized or grid search to tune key hyperparameters such as

- Evaluation: Evaluate all models on a held-out test set using domain-appropriate metrics (e.g., AUC-ROC, Accuracy, F1-Score, MSE). Perform statistical significance testing on the results.

Protocol: Addressing Class Imbalance with GBDT

Objective: To improve GBDT performance on imbalanced datasets common in medical applications (e.g., rare disease detection) [25]. Materials: An imbalanced tabular dataset.

- Baseline Model: Train a GBDT model (LightGBM or XGBoost) using the standard cross-entropy loss function.

- Class-Balanced Loss Functions: Implement and test class-balanced loss functions within the GBDT framework:

- Weighted Cross-Entropy (WCE): Assigns higher weights to the minority class.

- Focal Loss: Down-weights the loss assigned to well-classified examples, focusing learning on hard negatives.

- Comparison: Compare the performance of the baseline model against models using WCE and Focal Loss based on metrics like F1-score and precision-recall AUC, which are more informative for imbalanced data [25].

Workflow Visualization: GBDT for Tabular Data

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for applying and evaluating GBDT models on tabular data, incorporating protocols from section 4.

GBDT Implementation and Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Implementation Tools for GBDT Research

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost [20] | Software Library | A highly optimized implementation of GBDT, known for its performance and scalability. |

| LightGBM [20] [25] | Software Library | A GBDT framework designed for efficiency and distributed training, supporting GPU learning. |

| CatBoost [20] [22] | Software Library | Excels at handling categorical features natively with minimal preprocessing. |

| SHAP [23] | Analysis Library | Explains the output of any machine learning model, providing critical model interpretability for GBDTs. |

| Class-Balanced Loss 4 GBDT [25] | Python Package | Implements class-balanced loss functions (e.g., WCE, Focal Loss) for GBDT to tackle imbalanced datasets. |

| Scikit-learn | Software Library | Provides essential utilities for data preprocessing, model evaluation, and hyperparameter tuning. |

Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) algorithms represent a powerful class of machine learning techniques that have demonstrated remarkable success in medical research. Their ability to handle the complex, heterogeneous data typical of healthcare domains while providing interpretable insights makes them particularly valuable for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Within medium prediction research frameworks, GBDT models excel at integrating diverse data types and identifying critical predictive features from high-dimensional clinical and omics datasets. This capability enables more accurate disease prediction, patient stratification, and biomarker discovery, significantly advancing precision medicine initiatives. This document outlines the specific advantages of GBDT methodologies through structured data presentation, experimental protocols, and visual workflows to facilitate their application in biomedical research contexts.

Quantitative Performance in Medical Research

GBDT algorithms have demonstrated superior performance across various medical domains, consistently outperforming traditional statistical methods and other machine learning approaches in prediction accuracy and robustness.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of GBDT Models vs. Traditional Methods in Cardiovascular Disease Prediction [6]

| Model | Accuracy (%) | Precision | Specificity | F1 Score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBDT+LR | 78.3 | 0.784 | 0.781 | 0.782 | 0.841 |

| GBDT | 72.4 | 0.725 | 0.723 | 0.724 | 0.795 |

| Logistic Regression | 71.4 | 0.715 | 0.714 | 0.714 | 0.763 |

| Random Forest | 71.5 | 0.716 | 0.715 | 0.715 | 0.770 |

| Support Vector Machine | 69.3 | 0.694 | 0.692 | 0.693 | 0.741 |

Table 2: GBDT Performance in Predicting Postoperative Atelecstasis in Destroyed Lung Patients [21]

| Evaluation Metric | GBDT Model (Training Set) | Logistic Model (Training Set) | GBDT Model (Validation Set) | Logistic Model (Validation Set) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 0.795 | 0.763 | 0.776 | 0.811 |

| Key Predictors | Operation Time (51.037) | Operation Duration (P=0.048) | Operation Time | Operation Duration |

| Intraoperative Blood Loss (38.657) | Sputum Obstruction (P=0.002) | Intraoperative Blood Loss | Sputum Obstruction | |

| Presence of Lung Function (9.126) | - | Presence of Lung Function | - | |

| Sputum Obstruction (1.180) | - | Sputum Obstruction | - |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GBDT+LR Model for Cardiovascular Disease Prediction

Objective: To implement a hybrid GBDT+LR model for predicting cardiovascular disease risk using clinical and demographic patient data [6].

Dataset: UCI Cardiovascular Disease dataset (~70,000 patients, 12 features including age, height, weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity) [6].

Preprocessing Steps:

- Missing Data Handling: Verify dataset completeness; no missing values reported in source data [6].

- Outlier Detection and Removal: Use interquartile range (IQR) method with visualization:

- Calculate Q1 (25th percentile) and Q3 (75th percentile) for each numerical attribute

- Compute IQR = Q3 - Q1

- Identify outliers outside [Q1 - step × IQR, Q3 + step × IQR] (default step=1.5)

- Remove records with physiological measurements outside clinically plausible ranges [6].

- Data Splitting: Randomly divide dataset into training (70%) and testing (30%) sets.

GBDT Feature Transformation:

- Train GBDT model (XGBoost, LightGBM, or CatBoost) on training data.

- Use GBDT to generate new feature combinations through decision paths.

- Transform original features into leaf indices of the trained GBDT trees.

- Encode these indices as binary features for LR input.

Model Training and Evaluation:

- Train Logistic Regression classifier on transformed features.

- Evaluate performance using accuracy, precision, specificity, F1 score, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), AUC, and Average Precision-Recall (AUPR).

- Compare against baseline models (LR, RF, SVM, GBDT alone) using identical train-test splits.

Implementation Considerations:

- Utilize Spark big data framework for distributed processing of large datasets [6].

- Implement front-end visualization using Vue+SpringBoot for clinical deployment [6].

Protocol 2: GBDT for Postoperative Complication Prediction

Objective: To develop a GBDT model for predicting postoperative atelectasis in patients with destroyed lungs using perioperative clinical factors [21].

Dataset: 170 patients with destroyed lungs (25 with atelectasis, 145 without) from Chest Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (2021-2023) [21].

Data Collection:

- Baseline Data: Gender, age, height, weight, smoking history, diabetes, hypertension, COPD, bronchiectasis, lung damage type, electrolyte abnormalities [21].

- Preoperative Indicators: Lung function, fasting blood glucose, white blood cell count, neutrophil count, platelet count, fibrinogen, CRP, hs-CRP [21].

- Intraoperative Indicators: Operation type, operation time, intraoperative blood loss [21].

- Postoperative Indicators: Pain score, hypoxemia, pleural effusion, sputum obstruction [21].

Statistical Analysis:

- Perform univariate analysis using appropriate tests (t-test, Wilcoxon rank sum, χ²) to identify significant predictors.

- Split data into training (n=119) and validation (n=51) sets using 7:3 ratio [21].

GBDT Model Development:

- Train GBDT model using training set with atelectasis as outcome variable.

- Tune hyperparameters (tree depth, learning rate, number of trees) via cross-validation.

- Calculate relative importance scores for all predictors to identify key risk factors.

- Compare performance against logistic regression model using AUC, calibration curves, and decision curve analysis.

Validation Approach:

- Evaluate model performance on independent validation set.

- Use Delong test to compare AUC differences between models statistically.

- Assess clinical utility through decision curve analysis across probability thresholds.

Visual Workflows and Signaling Pathways

GBDT Medical Research Workflow

GBDT Algorithm Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for GBDT Medical Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost Library | Optimized GBDT implementation providing high performance and scalability with regularization techniques to control overfitting [20] [26]. | import xgboost as xgb; model = xgb.XGBClassifier() |

| LightGBM Framework | Efficient GBDT implementation using leaf-wise tree growth and histogram-based splitting for faster training on large-scale medical datasets [20] [26]. | import lightgbm as lgb; model = lgb.LGBMClassifier() |

| CatBoost Algorithm | GBDT variant with native handling of categorical features through ordered boosting, eliminating need for extensive preprocessing [20] [26]. | from catboost import CatBoostClassifier; model = CatBoostClassifier() |

| Spark MLlib | Distributed machine learning framework for processing large-scale medical datasets across clustered systems [6]. | from pyspark.ml.classification import GBTClassifier |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Model interpretation tool for quantifying feature importance and understanding individual predictions from GBDT models [6]. | import shap; explainer = shap.TreeExplainer(model) |

| Scikit-learn Gradient Boosting | Reference implementation of GBDT with versatile hyperparameter tuning for both classification and regression tasks [16]. | from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingClassifier |

| Clinical Data Preprocessing Tools | Libraries for handling missing values, outlier detection, and feature scaling specific to medical data constraints [6] [21]. | Pandas, NumPy, Scikit-learn preprocessing modules |

Advantages in Handling Mixed Data Types

GBDT algorithms possess inherent capabilities to process the heterogeneous data types commonly encountered in medical research without requiring extensive preprocessing or feature engineering.

Native Handling of Categorical and Numerical Features

Medical datasets typically contain both categorical variables (e.g., gender, diagnosis codes, medication history) and continuous numerical measurements (e.g., laboratory values, vital signs, omics data). GBDT implementations, particularly CatBoost, are specifically designed to handle categorical features directly through innovative encoding approaches [20] [26]. This capability eliminates the need for one-hot encoding, which can dramatically increase dimensionality in datasets with high-cardinality categorical variables [26]. The algorithms automatically learn optimal split points for both data types during tree construction, effectively capturing complex interactions between different feature types that might be missed by traditional statistical methods.

Robustness to Data Sparsity and Weak Correlations

Unlike deep learning architectures that thrive on strongly correlated, homogeneous data (such as pixels in images or words in text), GBDT models excel with the sparse, weakly correlated features characteristic of tabular medical data [20]. The tree-based structure naturally handles missing values and zero-inflated distributions common in electronic health records and medical claims data. This robustness makes GBDT particularly suitable for healthcare applications where features may have heterogeneous distributions and complex, non-linear relationships with outcomes [20] [6].

Feature Insight Capabilities

Beyond prediction accuracy, GBDT models provide valuable interpretability features that facilitate scientific discovery and hypothesis generation in medical research.

Quantitative Feature Importance Rankings

GBDT algorithms generate quantitative measures of variable importance based on how frequently features are used for splitting across all trees in the ensemble, weighted by the improvement in the model's objective function resulting from each split [21]. This capability was demonstrated in the destroyed lung study, where operation time (importance score: 51.037), intraoperative blood loss (38.657), presence of lung function (9.126), and sputum obstruction (1.180) were quantitatively ranked as predictors of postoperative atelectasis [21]. Such rankings help researchers identify the most clinically relevant factors driving predictions, guiding further investigation into biological mechanisms and potential intervention points.

Automated Feature Combination and Interaction Detection

The GBDT+LR framework exemplifies how these models can automatically discover and leverage informative feature combinations [6]. By using GBDT as a feature preprocessor for logistic regression, the model generates new combinatorial features based on decision paths through multiple trees [6]. This approach captures complex interaction effects between clinical variables that might be missed in traditional regression models with manually specified interaction terms. The ability to automatically detect and utilize these patterns makes GBDT particularly valuable for exploring high-dimensional biomedical data where the relationships between predictors and outcomes are not fully understood.

GBDT algorithms offer substantial advantages for medical research, particularly in their native ability to handle mixed data types and provide meaningful feature insights. Through robust performance across diverse clinical prediction tasks and inherent interpretability features, these models facilitate both accurate prediction and scientific discovery. The experimental protocols and visual workflows presented herein provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing GBDT methodologies in various biomedical contexts. As medical data continues to grow in volume and complexity, GBDT approaches will play an increasingly vital role in translating heterogeneous healthcare data into actionable clinical insights and improved patient outcomes.

Implementing GBDT in Practice: Algorithms, Workflows, and Real-World Biomedical Use Cases

Gradient boosting decision trees (GBDTs) represent a powerful class of machine learning algorithms that have become indispensable in medium prediction research, particularly within scientific fields such as drug development and healthcare analytics. These ensemble methods sequentially combine weak learners, typically decision trees, to create a strong predictive model that corrects errors from previous iterations [27]. Among the various implementations, XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost have emerged as the three most prominent algorithms, each with distinct architectural advantages and performance characteristics.

The dominance of these algorithms in data science is well-documented; analyses of Kaggle competitions reveal that gradient boosting algorithms are used in over 80% of winning solutions for structured data problems [27]. This remarkable adoption stems from their ability to capture complex non-linear relationships while maintaining computational efficiency, making them particularly valuable for researchers dealing with diverse types of scientific data. As medium prediction research often involves heterogeneous data sources including clinical measurements, molecular structures, and experimental parameters, understanding the nuanced differences between these GBDT implementations becomes critical for building optimal predictive models.

Architectural Comparison and Performance Analysis

Core Algorithmic Differences

The fundamental differences between XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost originate from their distinct approaches to tree construction and feature handling, which directly impact their performance characteristics in research applications.

XGBoost employs a level-wise (depth-wise) tree growth strategy, building trees horizontally by splitting all nodes at a given level before proceeding to the next level. This approach creates balanced trees and helps prevent overfitting, but can be computationally expensive as it may create splits with low information gain [27]. XGBoost incorporates L1 and L2 regularization directly into its objective function, which penalizes model complexity and enhances generalization capability [28] [27]. The algorithm also efficiently handles missing values through a built-in routine that learns the optimal direction for missing data during training [28].

LightGBM utilizes a leaf-wise tree growth strategy that expands the tree vertically by identifying the leaf with the highest loss reduction and splitting it. This approach converges faster and can achieve lower loss, but may create deeper, unbalanced trees that are more prone to overfitting on small datasets [29] [27]. LightGBM introduces two key innovations: Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS), which retains instances with large gradients and randomly samples those with small gradients, and Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB), which bundles mutually exclusive features to reduce dimensionality [27]. These innovations make LightGBM exceptionally fast and memory-efficient.

CatBoost features symmetric (oblivious) trees where the same splitting criterion is applied across all nodes at the same level. This symmetric structure acts as a form of regularization and enables extremely fast prediction times [30]. CatBoost's most distinctive innovation is Ordered Boosting, a permutation-driven approach that processes data sequentially to prevent target leakage—a common issue when handling categorical features [31] [30]. This makes CatBoost particularly robust for datasets with significant categorical features.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of GBDT Algorithms

| Metric | XGBoost | LightGBM | CatBoost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Speed | Moderate | Very Fast (~25x faster than XGBoost) | Moderate to Fast |

| Inference Speed | Fast | Fast | Very Fast |

| Memory Usage | High | Low | Moderate |

| Handling Categorical Features | Requires preprocessing | Direct handling with less effectiveness | Superior native handling |

| Default Performance | Requires tuning | Good with defaults | Excellent with minimal tuning |

Recent research demonstrates the practical implications of these architectural differences. In a 2025 study comparing intrusion detection methods in wireless sensor networks, CatBoost optimized with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) achieved exceptional performance metrics with an R² value of 0.9998, MAE of 0.6298, and RMSE of 0.7758, outperforming XGBoost, LightGBM, and other benchmark algorithms [32]. The study highlighted CatBoost's advantage for applications requiring high-precision prediction with minimal error.

Inference speed benchmarks further illustrate CatBoost's advantages in production environments. Testing reveals CatBoost can complete inference tasks in approximately 1.8 seconds, compared to 71 seconds for XGBoost and 88 seconds for LightGBM—representing a 35-48x speed improvement [31]. This performance advantage is attributed to CatBoost's symmetric tree structure, which enables highly efficient CPU implementation and predictable execution paths [31] [30].

For large-scale applications, a diabetes prediction study utilizing data from 277,651 participants demonstrated LightGBM's superiority in handling massive datasets, achieving an AUC of 0.844 compared to logistic regression's 0.826 [33]. The study also highlighted LightGBM's better calibration, with an expected calibration error (ECE) of 0.0018 versus 0.0048 for logistic regression, confirming GBDT's reliability for clinical prediction models with large sample sizes.

Table 2: Algorithm Selection Guide for Research Applications

| Research Scenario | Recommended Algorithm | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Small to Medium Datasets | XGBoost | Regularization prevents overfitting; better performance on smaller data |

| Large-Scale Datasets | LightGBM | Superior speed and memory efficiency with massive data |

| Categorical-Rich Data | CatBoost | Native handling avoids preprocessing and prevents target leakage |

| Real-Time Prediction | CatBoost | Fastest inference speed due to symmetric trees |

| Resource-Constrained Environments | LightGBM | Lowest memory usage and high training speed |

| Minimal Tuning Required | CatBoost | Excellent out-of-the-box performance with default parameters |

Experimental Protocols for GBDT Implementation

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

Protocol 1: Data Preparation for GBDT Algorithms

Missing Value Handling:

- For XGBoost: The algorithm automatically handles missing values during training. Verify proper treatment using the

missingparameter. - For LightGBM: Preprocess missing values explicitly or use the

use_missing=falseparameter. - For CatBoost: No special handling required; native support for missing values.

- For XGBoost: The algorithm automatically handles missing values during training. Verify proper treatment using the

Categorical Feature Processing:

- XGBoost: Require one-hot encoding or label encoding prior to training.

- LightGBM: Specify categorical features using

categorical_featureparameter; algorithm handles encoding internally. - CatBoost: Declare categorical features with

cat_featuresparameter; Ordered Boosting automatically processes them without preprocessing.

Feature Scaling: Gradient boosting algorithms are generally insensitive to feature scaling, but normalization (0-1 range) can improve convergence for some implementations.

Training-Validation Split: For medium prediction research, allocate 70-80% for training and 20-30% for validation using stratified sampling for classification tasks to maintain class distribution.

Model Training and Hyperparameter Optimization

Protocol 2: Benchmarking GBDT Algorithms

This protocol, adapted from comparative analysis [28], provides a standardized framework for benchmarking GBDT algorithms on research datasets. For medium prediction tasks, researchers should modify hyperparameters based on dataset characteristics and research objectives.

Protocol 3: Advanced Hyperparameter Tuning for Research Applications

XGBoost Critical Parameters:

max_depth: Control tree complexity (typical range: 3-10)learning_rate: Shrink contribution of each tree (typical range: 0.01-0.3)subsample: Fraction of samples used for training (typical range: 0.7-1.0)colsample_bytree: Fraction of features used (typical range: 0.7-1.0)reg_alphaandreg_lambda: L1 and L2 regularization terms

LightGBM Critical Parameters:

num_leaves: Maximum number of leaves in one tree (typical range: 31-127)min_data_in_leaf: Prevent overfitting (typical range: 20-200)feature_fraction: Fraction of features used (typical range: 0.7-1.0)bagging_fraction: Fraction of data used (typical range: 0.7-1.0)

CatBoost Critical Parameters:

depth: Tree depth (typical range: 4-10)l2_leaf_reg: L2 regularization coefficient (typical range: 1-10)random_strength: For scoring splits (typical range: 0.1-10)bagging_temperature: Controls Bayesian bootstrap (typical range: 0-1)

For optimal results in medium prediction research, employ Bayesian optimization methods or evolution strategies as demonstrated in a 2025 study predicting heat capacity of liquid siloxanes, where GBDT optimized with Evolution Strategies (ES) achieved R² = 0.9199 on test data [34].

Visualization of GBDT Architectures

Tree Growth Strategies Comparison

GBDT Tree Growth Strategies compares the fundamental architectural differences between the three algorithms. XGBoost's level-wise approach builds balanced trees but may include less informative splits. LightGBM's leaf-wise strategy focuses computational resources on the most promising leaves, leading to faster convergence but potentially deeper trees. CatBoost's symmetric trees apply identical splitting conditions across entire levels, enabling efficient computation and serving as implicit regularization.

Research Application Workflow

GBDT Selection Workflow for Research provides a systematic decision framework for researchers selecting appropriate GBDT implementations based on dataset characteristics and research constraints. The workflow emphasizes the importance of categorical feature handling, dataset scale, and computational resources in algorithm selection, followed by a robust model development process.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for GBDT Implementation

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for GBDT Research

| Tool Name | Type | Research Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost Python Package | Library | General-purpose gradient boosting for structured data | import xgboost as xgbmodel = xgb.XGBClassifier() |

| LightGBM Python Package | Library | Large-scale data training with high efficiency | import lightgbm as lgbmodel = lgb.LGBMClassifier() |

| CatBoost Python Package | Library | Datasets with categorical features, minimal preprocessing | from catboost import CatBoostClassifiermodel = CatBoostClassifier(verbose=0) |

| Scikit-learn | Library | Data preprocessing, model evaluation, and comparison | from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_splitfrom sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score |

| Hyperopt | Library | Advanced hyperparameter optimization | Bayesian optimization for parameter tuning |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Library | Model interpretation and feature importance analysis | Integrated with CatBoost for model explanations |

The selection of an appropriate GBDT implementation for medium prediction research requires careful consideration of dataset characteristics, computational constraints, and research objectives. XGBoost remains a robust, general-purpose choice with strong regularization capabilities, particularly suitable for smaller datasets where extensive tuning is feasible. LightGBM offers unparalleled training speed and memory efficiency for large-scale research applications, making it ideal for massive datasets common in contemporary scientific research. CatBoost provides superior performance on categorical-rich data and excellent out-of-the-box performance with minimal hyperparameter tuning, valuable for rapid prototyping and applications requiring fast inference.

For the research community, these GBDT implementations represent powerful tools for advancing predictive modeling capabilities. Future developments will likely focus on enhanced interpretability features, integration with deep learning approaches, and specialized optimizations for domain-specific applications. By understanding the architectural foundations and performance characteristics of each algorithm, researchers can make informed decisions that optimize both predictive accuracy and computational efficiency in their scientific investigations.

Data Preparation and Feature Engineering for Medical Datasets

Within the broader context of gradient-boosting decision tree (GBDT) research for medical prediction, the critical importance of robust data preparation and feature engineering cannot be overstated. Medical datasets present unique challenges including heterogeneity, missing values, class imbalances, and complex nonlinear relationships between variables. GBDT algorithms excel at capturing intricate nonlinear patterns and feature interactions [6], making them particularly suited for medical prediction tasks. However, their performance is heavily dependent on proper data preprocessing and feature representation. This protocol outlines comprehensive methodologies for preparing medical data to optimize GBDT performance, with applications spanning cardiovascular disease prediction [6], Parkinson's disease detection [35], and other healthcare domains.

Data Preprocessing Protocols

Handling Missing Data and Outliers

Medical datasets frequently contain missing values and anomalies that can severely impact model performance. The following protocols address these challenges systematically:

Missing Data Assessment: Begin by quantifying missingness patterns across all features. For datasets with minimal missing values (e.g., the UCI cardiovascular dataset with no missing attributes [6]), imputation may be unnecessary. For datasets with significant missingness, employ techniques appropriate to data type: median/mode imputation for low missingness (<5%), multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) for moderate missingness (5-20%), or advanced methods like missForest for high missingness (>20%).

Outlier Detection and Treatment: For numerical attributes, visualize distributions using box plots and employ the interquartile range (IQR) method with adjustable step parameters [6]. Calculate IQR as the difference between the 75th (Q3) and 25th (Q1) percentiles. Classify values outside Q1 - step × IQR or Q3 + step × IQR as outliers. For medical variables with known physiological ranges (e.g., blood pressure), supplement statistical methods with clinical validity checks. Remove or winsorize outliers based on dataset size and clinical justification.

Data Scaling and Normalization

Different scaling techniques profoundly impact GBDT performance, particularly when combining features of varying magnitudes:

RobustScaler Implementation: For medical datasets with potential outliers, apply RobustScaler to center features around median and scale by IQR, reducing outlier influence [35]. This technique is particularly effective for laboratory values with skewed distributions.

Alternative Scaling Methods: Compare RobustScaler performance against Min-Max Scaler (scaling to specified range, typically [0,1]), Max Abs Scaler (scaling by maximum absolute value), and Z-score Standardization (mean-centering with unit variance) [35]. Select method based on feature distribution characteristics and GBDT performance.

Addressing Class Imbalance

Medical datasets frequently exhibit significant class imbalance, which can bias GBDT predictions. Implement the following resampling strategies prior to model training:

Oversampling Techniques: Apply Random Oversampling (ROS) to duplicate minority class instances, or Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to generate synthetic examples [35]. For more sophisticated oversampling, consider Borderline SMOTE (focusing on boundary examples) or ADASYN (adaptively generating samples based on density distribution).

Undersampling Techniques: Implement Random Undersampling (RUS) to reduce majority class instances, Cluster Centroid Undersampling to generate representative cluster centroids, or NearMiss algorithms (versions 1, 2, and 3) with varying selection strategies [35]. Evaluate the trade-off between information loss and class balance.

Hybrid Approaches: Combine multiple sampling techniques (e.g., ROS, SMOTE, and RUS) to achieve optimal class distribution [35]. The specific combination should be determined through cross-validation performance.

Feature Engineering Framework

Automated Feature Selection

GBDT models benefit from effective feature selection to reduce dimensionality and highlight predictive variables:

Tree-Based Importance: Utilize GBDT's inherent feature importance metrics (gain, cover, frequency) to identify and retain top-performing features. For the cardiovascular disease prediction task, critical features include age, blood pressure measurements, cholesterol levels, and behavioral factors [6].

SHAP Analysis: Implement SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to quantify feature contributions to predictions [35]. For Parkinson's disease detection using acoustic data, Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) consistently emerge as influential features through SHAP analysis [35].

Feature Combination with GBDT+LR

The GBDT+LR hybrid model leverages strengths of both algorithms for enhanced medical prediction:

GBDT Feature Transformation: Train GBDT model on original features, using its predicted results as new feature combinations instead of original inputs [6]. This approach automatically handles complex feature interactions that challenge traditional logistic regression.

LR Final Classification: Input the GBDT-transformed features into logistic regression model for final classification [6]. This combination has demonstrated superior performance in cardiovascular disease prediction compared to individual algorithms.

Experimental Protocols

Cardiovascular Disease Prediction Protocol

The following detailed methodology is adapted from successful cardiovascular disease prediction research [6]:

Table 1: Cardiovascular Disease Dataset Structure

| Feature Category | Specific Features | Data Type | Preprocessing Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Demographics | Age, Gender, Height, Weight | Numerical/Categorical | Outlier removal based on physiological ranges |

| Clinical Measurements | Systolic BP, Diastolic BP, Cholesterol, Glucose | Numerical | IQR outlier detection, clinical range validation |

| Behavioral Factors | Smoking, Alcohol intake, Physical activity | Categorical/Numerical | Encoding, normalization |

| Target Variable | Cardiovascular disease diagnosis | Binary | Class imbalance handling |

Data Acquisition: Source the UCI Cardiovascular Disease dataset containing approximately 70,000 instances with 11 risk factors and diagnosis label [6].

Data Preprocessing:

- Confirm no missing values exist across all attributes

- Apply IQR method (step=1.5) to detect outliers in numerical features

- Remove records with physiologically implausible values (e.g., negative diastolic blood pressure)

- Normalize numerical features using RobustScaler

Feature Engineering:

- Implement GBDT for automated feature combination

- Transform original features using GBDT output

- Prepare transformed features for LR input

Model Training & Evaluation:

- Partition data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

- Train GBDT+LR hybrid model alongside comparator models (LR, RF, SVM, GBDT)

- Evaluate using comprehensive metrics: accuracy, precision, specificity, F1, MCC, AUC, AUPR

Parkinson's Disease Detection Protocol

This protocol outlines PD detection using acoustic features across multiple datasets [35]:

Table 2: Parkinson's Disease Acoustic Datasets Comparison

| Dataset | Sample Size | PD/Healthy | Features | Best Performing Pipeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIU (Sakar) | 252 | 188/64 | 754 | RobustScaler + ROS/SMOTE/RUS + XGBoost |

| UEX (Carrón) | 60 | 30/30 | 34 | RobustScaler + Hybrid Sampling + AdaBoost |

| UCI (Little) | 31 | 23/8 | 23 | RobustScaler + Combination Sampling + Ensemble |

Data Acquisition: Obtain three PD speech datasets (MIU, UEX, UCI) containing sustained vowel phonations with extracted acoustic features [35].

Hybrid Preprocessing:

- Apply RobustScaler to normalize feature distributions across datasets

- Implement combination sampling (ROS, SMOTE, RUS) to address class imbalance

- Handle dataset heterogeneity through consistent feature representation

Ensemble Classification:

- Train multiple ensemble models (XGBoost, AdaBoost, GBDT, Random Forest)

- Optimize hyperparameters through cross-validation

- Select best-performing model based on accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score

Model Interpretation: