How Salmonella Typhimurium Hijacks Our Gut Cells

The Science Behind Bacterial Adhesion and Infection

Explore the ScienceIntroduction

Every year, salmonella infections cause approximately 1.35 million illnesses in the United States alone, with thousands of hospitalizations and hundreds of deaths. Behind these statistics lies an extraordinary biological drama that unfolds at the cellular level within our intestines—a story of bacterial invasion that begins with a critical first step: adherence. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, one of the most common causes of foodborne illness, employs remarkable nanoscale machinery to latch onto our gut cells, initiating a complex infection process 2 .

Did You Know?

As few as 1 colony forming unit per milliliter in 25g of ready-to-eat food can cause human disease 2 , making detection critically important.

The ability of Salmonella to adhere to intestinal enterocytes represents not just a fascinating subject of scientific inquiry but a crucial battlefield where the outcome of infection is determined. Understanding this process has implications for developing new therapeutic strategies, improving food safety, and combating antibiotic resistance.

The Battlefield: Understanding Bacterial Adhesion

Bacterial adhesion represents the critical initial step in microbial colonization and infection pathogenesis. For Salmonella Typhimurium, successful attachment to intestinal enterocytes is essential for establishing infection in the hostile environment of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Resist mechanical clearance from the intestinal tract

- Colonize specific regions of the intestine

- Deliver virulence factors directly to host cells

- Trigger internalization into enterocytes

Salmonella Typhimurium possesses a diverse array of surface adhesins—specialized structures that mediate attachment to host cells and surfaces. Research has revealed that this pathogen encodes information for up to 20 different adhesive structures, making its adhesome one of the most complex among pathogenic bacteria 9 .

These include fimbrial adhesins, non-fimbrial adhesins, flagella, and secreted adhesins, all tightly regulated in response to environmental conditions.

The Mechanics of Microbial Velcro: How Salmonella Sticks

Among Salmonella's adhesion tools, type 1 fimbriae (T1F) stand out as one of the most common and well-studied adhesive organelles. These hair-like structures extend from the bacterial surface, measuring approximately 7 nm in diameter and composed primarily of repeating FimA protein subunits 6 .

At the tip of each fimbria resides the FimH adhesin, a lectin-like protein that specifically recognizes and binds to mannose-containing glycoproteins on host cell surfaces.

While type 1 fimbriae play a crucial role in adhesion, Salmonella employs multiple redundant systems to ensure successful host attachment:

- Lpf fimbriae: Long polar fimbriae that contribute to intestinal colonization

- MisL: An autotransporter adhesin that binds fibronectin

- Flagella: Not only provide motility but also contribute to adhesion 4 8

Recent research has revealed that even post-translational modifications of bacterial surface structures can influence adhesion 8 .

A Closer Look: The Landmark 1987 Adhesion Experiment

Methodology: Tracing Bacterial Attachment

Our understanding of Salmonella adhesion owes much to a pivotal study published in 1987 that systematically examined the adherence of Salmonella Typhimurium to rat enterocytes 1 . The experimental approach was both elegant and insightful:

- Bacterial preparation: Researchers used radiolabeled bacteria to enable precise quantification

- Enterocyte isolation: Fresh enterocytes were isolated from rat small intestines

- Adhesion assays: Bacteria and enterocytes were combined under controlled conditions

- Inhibition tests: Various inhibitors were added to elucidate binding mechanisms

Revelations: Phases of Attachment and Invasion

The 1987 study revealed several fundamental aspects of Salmonella adhesion 1 :

- Biphasic adhesion kinetics: Adherence occurred in two distinct phases

- Fimbrial dominance: Type 1 fimbriated strains adhered in significantly higher numbers

- Mannose sensitivity: Adherence was inhibited by D-mannose and its derivative

- Metabolic dependence: The second phase required bacterial protein synthesis

Interpretation: What the Findings Meant

The biphasic nature of adhesion suggested a two-step mechanism for Salmonella infection: an initial reversible attachment mediated by fimbriae, followed by a strengthening phase that involved additional bacterial factors and led to host cell damage.

The finding that nonviable bacteria could adhere but not cause damage indicated that adhesion alone was insufficient for pathogenesis—subsequent steps requiring active bacterial metabolism were necessary.

| Experimental Condition | Adhesion Level | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Fimbriated strains | High | Demonstrated importance of type 1 fimbriae |

| Non-fimbriated strains | Low | Confirmed fimbriae as primary adhesion factor |

| Plus D-mannose | Inhibited | Showed mannose-sensitive binding mechanism |

| Plus chloramphenicol | Second phase inhibited | Revealed requirement for bacterial protein synthesis |

| Nonviable bacteria | Adhered but no damage | Showed adhesion doesn't require viability but damage does |

Table 1: Key Findings from the 1987 Adhesion Experiment 1

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Studying bacterial adhesion requires specialized reagents and techniques. Here are some of the key tools that have advanced our understanding of Salmonella-host interactions:

| Reagent/Technique | Function | Application in Adhesion Research |

|---|---|---|

| D-mannose | Competitive inhibitor | Blocks fimH-mediated adhesion, confirms mechanism |

| Methyl α-D-mannoside | Mannose analog | More stable inhibitor for prolonged experiments |

| Chloramphenicol | Protein synthesis inhibitor | Distinguishes between adhesion phases |

| Radiolabeling (³H-thymidine) | Bacterial tracking | Enables precise quantification of adhered bacteria |

| Tet-on expression system | Inducible gene expression | Allows controlled study of individual adhesins 9 |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Bacterial Adhesion

Recent technological advances have expanded this toolkit significantly:

- CRISPR interference: Gene silencing for specific adhesion genes

- Single-cell force spectroscopy: Measures binding forces

- Organoid models: 3D cell cultures for physiologically relevant models

- Microfluidics: Studies adhesion under physiological shear stress

Advanced imaging techniques including atomic force microscopy and transmission electron microscopy have provided stunning visualizations of fimbrial structures and their interaction with host surfaces.

These tools have confirmed the structural predictions from genetic studies and revealed the nanoscale architecture of adhesion complexes.

Beyond the Gut: Implications and Applications

Understanding Salmonella adhesion has direct implications for food safety practices and pathogen detection. Since as few as 1 colony forming unit per milliliter in 25g of ready-to-eat food can cause human disease 2 , sensitive detection methods are crucial for preventing outbreaks.

Traditional culture-based methods remain the "gold standard" but require 3-5 days to complete 5 . Rapid molecular methods including PCR-based assays and immunological techniques have reduced detection times to 48 hours or less.

The discovery of specific adhesion mechanisms has inspired new detection approaches such as mannose-based capture systems and antibodies against FimH incorporated into lateral flow devices.

The detailed understanding of Salmonella adhesion has opened new avenues for therapeutic intervention. Rather than killing bacteria outright—an approach that drives antibiotic resistance—anti-adhesion strategies aim to prevent the initial attachment that establishes infection.

Natural compounds including cinnamaldehyde (from cinnamon) have shown promise in inhibiting fimbrial expression 3 . Animal studies confirmed that cinnamaldehyde treatment reduces intestinal colonization and inflammatory responses.

Other innovative approaches include mannose derivatives, adhesin-specific antibodies, adhesion-based vaccines, and probiotic strategies.

Therapeutic Advantages

Anti-adhesion therapies offer potential advantages over traditional antibiotics, including reduced selection pressure for resistance and preservation of beneficial microbiota. As antibiotic resistance continues to threaten our arsenal of antimicrobial drugs, such alternative approaches become increasingly valuable.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Battle Against Infection

The adherence of Salmonella Typhimurium to enterocytes represents a fascinating example of co-evolutionary adaptation between pathogen and host. Through sophisticated adhesive structures like type 1 fimbriae and complex regulation of their expression, Salmonella has developed efficient strategies to colonize the hostile environment of the intestinal tract.

The landmark 1987 study 1 provided crucial insights into the biphasic nature of adhesion, revealing both the initial fimbriae-mediated attachment and the subsequent protein synthesis-dependent strengthening phase. These findings have informed decades of subsequent research and therapeutic development.

As we continue to unravel the complexities of bacterial adhesion, we gain not only fundamental knowledge about microbial pathogenesis but also practical insights for combating infection. From improved food safety detection to innovative anti-adhesion therapies, understanding how Salmonella sticks to our cells helps us develop better strategies to prevent and treat disease.

1.35 Million

Yearly salmonella infections in the US7 nm

Diameter of type 1 fimbriae20+

Different adhesive structures encoded3-5 Days

For traditional Salmonella detectionThe biphasic adhesion process shows how Salmonella first attaches then strengthens its bond with enterocytes, requiring protein synthesis for the second phase 1 .

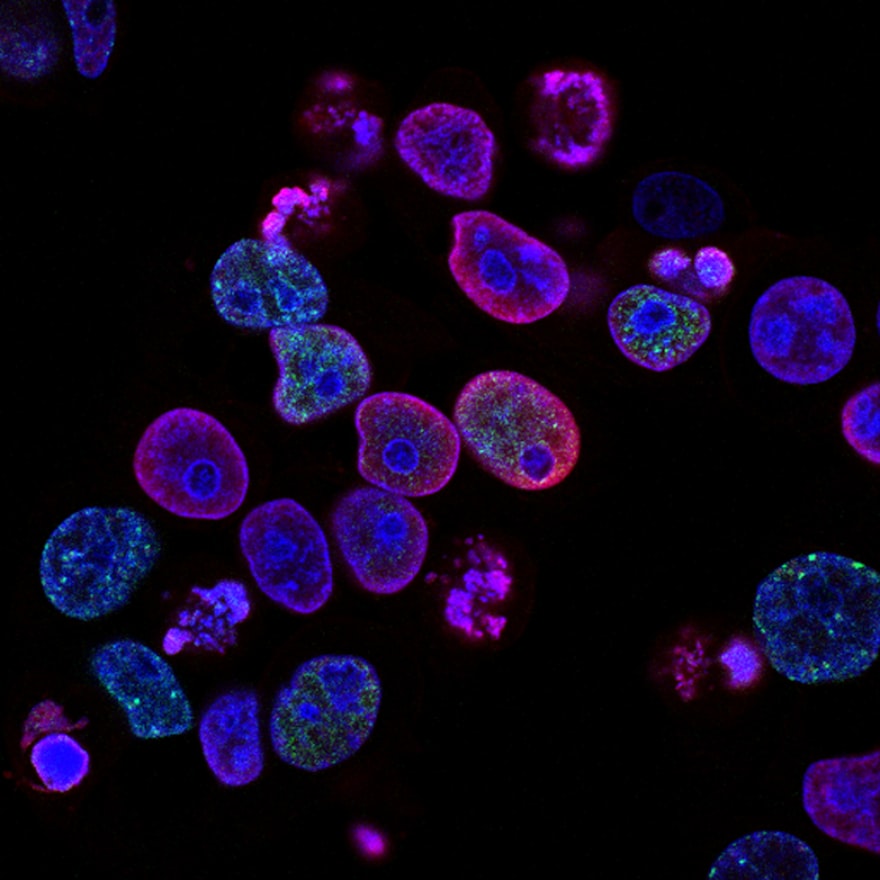

Salmonella bacteria (red) adhering to intestinal cells. Understanding this process is key to developing prevention strategies.