Machine Learning for AFM Biofilm Image Classification: From Fundamentals to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of machine learning (ML) for classifying atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of biofilms.

Machine Learning for AFM Biofilm Image Classification: From Fundamentals to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of machine learning (ML) for classifying atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of biofilms. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational synergy between AFM's high-resolution imaging and ML's analytical power. The content covers methodological approaches, including handling small datasets and leveraging large-area automated AFM, alongside troubleshooting common challenges like artifacts and statistical validation. It further examines the performance and generalizability of ML models across different bacterial species and laboratory conditions. By synthesizing recent advances, this review serves as a guide for implementing these techniques to accelerate biofilm research and the development of anti-fouling strategies and antimicrobial therapies.

The Synergy of AFM and Machine Learning in Biofilm Research

Why AFM is a Premier Technique for High-Resolution Biofilm Imaging

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has established itself as a premier technique for high-resolution biofilm imaging by providing unparalleled capabilities for characterizing the structural and mechanical properties of these complex microbial communities at the nanoscale. Unlike optical microscopy techniques that suffer from low resolution, or electron microscopy methods that require extensive sample preparation involving dehydration and metallic coatings that can distort native structures, AFM enables researchers to probe biofilms in their native, hydrated state with minimal sample preparation [1] [2]. This unique combination of capabilities has made AFM an indispensable tool for unraveling the nanoscale forces governing biofilm structure and behavior, providing critical insights for controlling microbial populations in both clinical and industrial environments [2].

The application of AFM in biofilm research has evolved significantly from early topographical imaging to a truly multiparametric platform that can interrogate all aspects of microbial systems [2]. Recent technological advancements, particularly in automation and machine learning integration, have transformed AFM from a tool limited to small-scale imaging of nanoscale features to a platform capable of capturing large-scale biological architecture while maintaining nanoscale resolution [1] [3]. This paradigm shift addresses the fundamental challenge in biofilm research of linking local subcellular and cellular scale changes to the evolution of larger functional architectures that determine biofilm stability, resilience, and resistance to external stressors [1].

Fundamental Principles and Advantages of AFM

Core Operating Principles

AFM operates by systematically scanning an extremely sharp tip (with a radius of curvature in the nanometer range) attached to a flexible cantilever across a sample surface. As the tip interacts with surface forces, cantilever deflections are monitored via a laser beam reflection system, generating detailed topographical images [2]. For soft biological samples like biofilms, tapping mode (also known as intermittent contact mode) is preferentially employed as it reduces friction and drag forces that could damage or distort delicate biofilm structures compared to contact mode imaging [2].

A significant advancement in AFM technology for biological applications is the development of frequency-modulation AFM (FM-AFM) with stiff qPlus sensors (k ≥ 1 kN/m), which enables imaging with minimal interaction forces (below 100 pN) to prevent damage to sensitive biological samples [4]. This approach maintains high quality factors (Q factors) even in liquid environments, with values up to 1000 achievable at minimal penetration depths, compared to the very low Q factors (1-30) typical of soft cantilevers completely immersed in liquid [4]. The ability to operate with small amplitudes (<100 pm) provides higher sensitivity to short-range forces that cannot be achieved with soft cantilevers due to the "jump-to-contact" problem [4].

Comparative Advantages for Biofilm Imaging

Table 1: Comparison of AFM with Other Biofilm Imaging Techniques

| Technique | Resolution | Sample Environment | Sample Preparation | Key Limitations for Biofilm Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Nanoscale (sub-cellular) | Native, hydrated conditions | Minimal; possible immobilization | Limited field of view (traditional AFM); requires surface attachment |

| Light Microscopy | ~200 nm | Hydrated conditions | Minimal; staining often required | Low resolution; limited penetration in thick biofilms [1] |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy | ~200 nm | Hydrated conditions | Fluorescent staining required | Resolution limit; staining may alter biofilm properties [1] |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Nanoscale | High vacuum | Dehydration, fixation, metallic coating | Sample distortion from preparation; not native conditions [1] |

Advanced AFM Methodologies for Biofilm Research

Large-Area Automated AFM Imaging

Traditional AFM has been constrained by a limited scan range (typically <100 μm), restricted by piezoelectric actuator constraints, making it difficult to capture the full spatial complexity of biofilms and raising questions about data representativeness [1]. This limitation has been successfully addressed through the development of large-area automated AFM approaches capable of capturing high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas with minimal user intervention [1] [3]. This transformative advancement enables researchers to connect detailed observations of individual bacterial cells with broader views across entire biofilm communities, effectively allowing visualization of both "the trees and the forest" in biofilm architecture [3].

The implementation of large-area AFM involves automated scanning processes with sophisticated image stitching algorithms that function effectively even with minimal matching features between individual images [1]. By limiting overlap between adjacent scans, researchers can maximize acquisition speed while still producing seamless, high-resolution images that comprehensively capture the spatial complexity of surface attachment and biofilm development [1]. This approach has revealed previously obscured spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology during early biofilm formation stages, including the discovery of a preferred cellular orientation among surface-attached Pantoea sp. YR343 cells forming a distinctive honeycomb pattern interconnected by flagellar structures [1].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Image Analysis

The integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) has dramatically advanced AFM capabilities in biofilm research by enabling automated processing and analysis of the massive datasets generated by large-area AFM imaging [1] [3]. ML applications in AFM span four key areas: sample region selection, scanning process optimization, data analysis, and virtual AFM simulation [1]. These technologies are particularly valuable for addressing the challenges of high-volume, information-rich data generated by large-area AFM, implementing automated image segmentation and analysis methods that extract critical parameters including cell count, confluency, cell shape, and orientation across extensive surface areas [1].

Specific ML implementations include convolution neural network models trained for shape recognition and classification, achieving F1 scores of 85 ± 5% in morphological categorization tasks [5] [6]. These models enable efficient analysis of complex morphological features that would be prohibitively time-consuming and subjective through manual categorization [5]. Furthermore, deep learning frameworks have been developed for automatic sample selection based on cell shape for AFM navigation during biomechanical mapping, achieving 60× speed-up in AFM navigation and significantly reducing the time required to locate specific cell shapes in large samples [7].

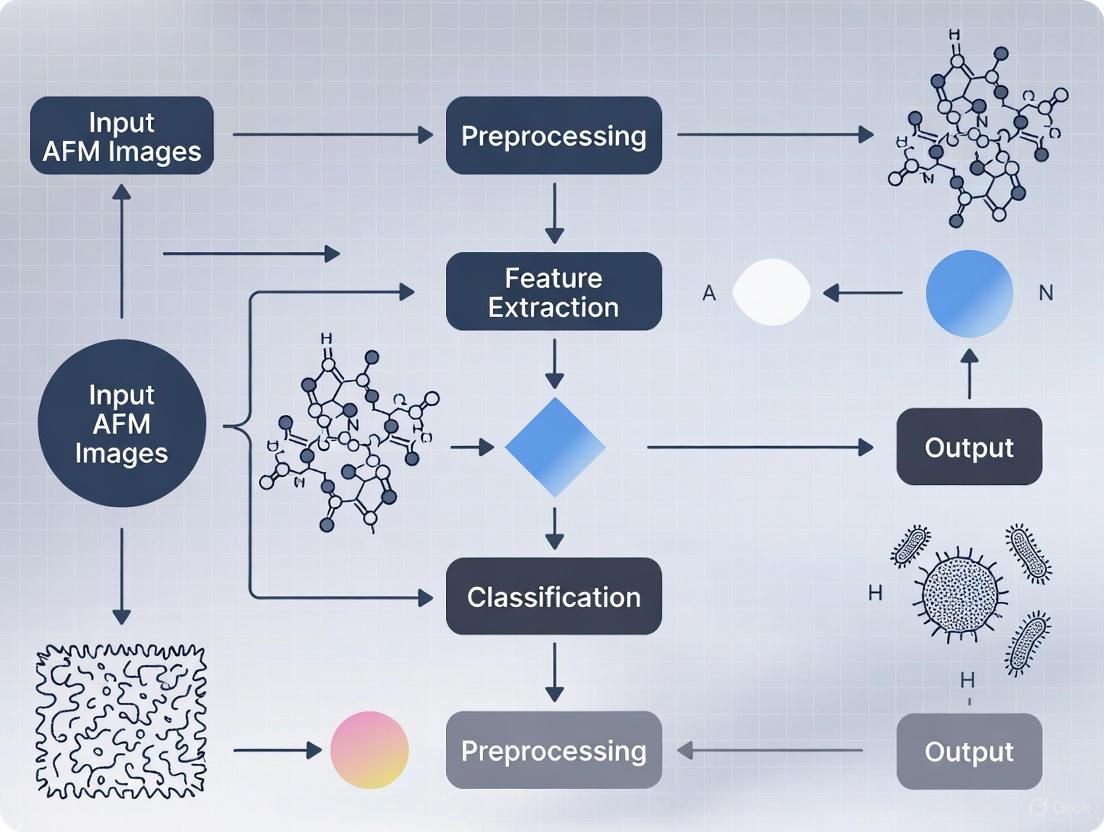

Figure 1: Machine learning workflow for AFM biofilm image analysis

Experimental Protocols for AFM Biofilm Imaging

Sample Preparation Methods

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful AFM imaging of biofilms while preserving their native structure. The following protocols have been validated for reliable biofilm characterization:

4.1.1 Substrate Selection and Functionalization

- Surface Treatment: Use PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or freshly cleaved mica to promote biofilm adhesion [1]. PFOTS (perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) creates a hydrophobic surface that facilitates bacterial attachment while providing a smooth baseline for imaging.

- Alternative Functionalizations: (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane or NiCl₂-coated mica can be used, though these may cause flattening of structures or round artefacts during direct air-drying [5].

- Combinatorial Approaches: Gradient-structured surfaces allow simultaneous study of how varying surface properties influence attachment dynamics and community structure [1].

4.1.2 Biofilm Immobilization Techniques

- Mechanical Immobilization: Utilize porous membranes or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps with customized microstructures (1.5-6 μm wide, 0.5 μm pitch, 1-4 μm depth) to physically trap microbial cells [2]. This approach offers secure immobilization capable of withstanding lateral forces during scanning.

- Chemical Immobilization: Apply poly-l-lysine, trimethoxysilyl-propyl-diethylenetriamine, or carboxyl group cross-linking to promote adhesion [2]. Optimization with divalent cations (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) and glucose may provide optimal attachment without significant reduction in viability [2].

- Liquid Cell Preparation: For hydrated imaging, use sample holders with integrated liquid baths (85 mm² area capacity) with up to 420 μl of appropriate biological solution [4]. Employ long tips (500-1000 μm) glued to the sensor's oscillating prong to allow partial submersion while maintaining sensor functionality.

4.1.3 Fixation and Dehydration for High-Resolution Imaging

- Optimal Preservation: Ethanol gradient dehydration followed by critical point drying best preserves native biofilm morphology [5].

- Alternative Method: Chemical dehydration with dimethoxypropane results in well-balanced shape distributions with lower aspect ratios [5].

- Fixation Importance: Chemical fixation plays a crucial role in both capturing and protecting biological structures on substrates, particularly for high-resolution imaging [5].

Imaging Parameters and Conditions

4.2.1 Instrument Configuration

- Sensor Selection: Employ stiff qPlus sensors (k ≥ 1 kN/m) for FM-AFM imaging in liquid environments, enabling small amplitude oscillation (<100 pm) and high sensitivity to short-range forces [4].

- Liquid Imaging: Maintain minimal penetration depth of the tip in liquid to preserve high Q factors (up to 1000 achievable) while ensuring sufficient immersion for biological relevance [4].

- Environmental Control: Conduct imaging at controlled temperature (typically 20-25°C) and humidity (40% recommended) to minimize evaporation effects during extended acquisitions [4].

4.2.2 Scanning Parameters

- Large-Area Imaging: Implement automated large-area AFM with limited overlap between adjacent scans (typically 5-10%) to maximize acquisition speed while maintaining image continuity [1].

- Resolution Settings: Configure pixel density to balance resolution and acquisition time; for overview scans, 512×512 pixels over 100×100 μm areas provides sufficient detail, while high-resolution cellular imaging may require 1024×1024 pixels over smaller regions [1].

- Force Control: Maintain minimal interaction forces (below 100 pN) to prevent damage to delicate biofilm structures, using frequency shift setpoints of -1 to -7 Hz in FM-AFM mode [4].

Figure 2: AFM biofilm imaging experimental workflow

Quantitative Analysis of Biofilm Properties

AFM enables comprehensive quantification of structural and mechanical properties essential for understanding biofilm function and response to interventions. The large-area automated approach combined with machine learning analysis facilitates statistically robust characterization across multiple scales.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters Accessible Through AFM Biofilm Imaging

| Parameter Category | Specific Measurable Parameters | Biological Significance | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Properties | Cellular dimensions (length: ~2 μm, diameter: ~1 μm for Pantoea sp. YR343) [1] | Growth state, cell division | Topographical imaging |

| Flagellar dimensions (height: 20-50 nm, length: tens of μm) [1] | Motility, surface attachment | High-resolution AFM | |

| Spatial distribution patterns (honeycomb organization) [1] | Community architecture, cell-cell interactions | Large-area mapping | |

| Mechanical Properties | Elastic modulus via nanoindentation | Biofilm stiffness, structural integrity | Force spectroscopy |

| Adhesion forces (cell-surface and cell-cell) | Attachment strength, cohesion | Force-distance measurements | |

| Turgor pressure of encapsulated cells | Cell viability, metabolic state | Hertz model analysis [2] | |

| Dynamic Processes | Surface coverage and confluency | Biofilm development stage | ML-based segmentation |

| Cellular orientation and alignment | Response to surface properties | Vector analysis | |

| Roughness and topography evolution | Structural complexity development | 3D surface analysis |

Research Reagent Solutions for AFM Biofilm Studies

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for AFM Biofilm Imaging

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS (Perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) | Surface treatment for glass substrates to promote bacterial adhesion | Creates hydrophobic surface; compatible with various bacterial species [1] |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane | Alternative surface functionalization for mica substrates | May cause flattening of biological structures [5] |

| NiCl₂ Coating | Mica functionalization for enhanced EV and bacterial capture | Prone to formation of round artefacts during direct air-drying [5] |

| Poly-L-Lysine | Chemical immobilization agent for microbial cells | Provides strong adhesion but may affect cell viability and nanomechanical properties [2] |

| Ethanol Gradient Series | Dehydration protocol for sample preservation | Critical for maintaining morphology; typically 30%-50%-70%-90%-100% series [5] |

| Critical Point Dryer | Sample drying equipment for morphology preservation | Superior to hexamethyldisilazane for retaining native structures [5] |

| PDMS Stamps | Mechanical immobilization with customized microstructures | Enables cell orientation control; dimensions customizable for target cells (1.5-6 μm wide, 0.5 μm pitch) [2] |

| Sapphire Tips | AFM probes for high-resolution imaging in liquid | Chemically inert, very hard; suitable for biological imaging [4] |

Case Study: Honeycomb Pattern Discovery in Pantoea sp. YR343

The power of large-area AFM combined with machine learning analysis is exemplified by the recent discovery of a unique honeycomb pattern in Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms [1]. This case study demonstrates how advanced AFM methodologies can reveal previously unrecognized structural organizations in microbial communities.

Experimental Implementation: Researchers employed large-area automated AFM to image Pantoea sp. YR343 on PFOTS-treated glass surfaces during early attachment stages (30 minutes to 8 hours post-inoculation) [1]. The automated system captured high-resolution images across millimeter-scale areas, with machine learning algorithms processing over 19,000 individual cells to quantify spatial organization patterns [1] [3].

Key Findings: Analysis revealed that surface-attached cells exhibited a preferred cellular orientation, self-organizing into a distinctive honeycomb pattern with precisely regulated gaps between cell clusters [1]. High-resolution imaging enabled visualization of flagellar structures bridging these gaps, suggesting that flagellar coordination plays a role in biofilm assembly beyond initial attachment [1]. The identification of these structures as flagella was confirmed using a flagella-deficient control strain, which showed no similar appendages under AFM [1].

Biological Significance: Though the complete biological role of these patterns requires further investigation, researchers hypothesize they likely contribute to biofilm cohesion and adaptability by creating an interconnected network that facilitates nutrient transport, communication, and structural stability [3]. This organizational pattern would have remained undetected using conventional AFM approaches limited to small imaging areas.

The integration of atomic force microscopy with machine learning represents a transformative advancement in biofilm research, enabling comprehensive structural and mechanical characterization of these complex microbial communities at scales relevant to their natural environments [1]. The development of large-area automated AFM has successfully addressed the longstanding limitation of traditional AFM - the inability to connect nanoscale cellular features with broader community organization patterns [1] [3].

Future developments in AFM technology for biofilm research will likely focus on enhancing real-time imaging capabilities under physiologically relevant conditions, further expanding the scale of automated imaging, and refining machine learning algorithms for predictive modeling of biofilm development and treatment responses [1]. These advancements will provide increasingly powerful tools to address the significant challenges posed by biofilms in clinical, industrial, and environmental contexts, particularly in an era of escalating antimicrobial resistance [8].

As AFM technologies continue to evolve alongside machine learning and artificial intelligence, researchers will gain unprecedented capabilities to decipher the structural principles governing biofilm resilience and develop targeted strategies for biofilm control in healthcare and industrial applications [1] [7]. The combination of high-resolution imaging, nanomechanical property mapping, and large-scale architectural analysis positions AFM as an indispensable platform for advancing our fundamental understanding of biofilm biology and developing effective interventions against biofilm-associated challenges.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a pivotal tool in biofilm research, capable of revealing structural and mechanical properties at the nanoscale. However, a significant challenge persists in linking these nanoscale observations to the functional macroscale organization of biofilms [1]. This application note addresses this scale-transition challenge through automated large-area AFM imaging coupled with machine learning (ML) classification, providing researchers with standardized protocols to bridge the resolution gap in microbial community analysis.

The inherent heterogeneity of biofilms—characterized by spatial and temporal variations in structure, composition, and density—necessitates advanced analytical approaches that can operate across multiple scales [1]. Traditional AFM methods, while providing critically important high-resolution insights, suffer from limited scan range and labor-intensive operation, restricting their ability to capture the full spatial complexity of biofilm architectures [1]. The integration of machine learning with expanded imaging capabilities now enables comprehensive characterization from cellular features to community-scale organization.

Quantitative Data Presentation

Performance Comparison: Human vs. Machine Learning Classification

Table 1: Classification accuracy for staphylococcal biofilm images

| Classification Method | Mean Accuracy | Recall | Off-by-One Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Researchers | 0.77 ± 0.18 | Not specified | Not specified |

| Machine Learning Algorithm | 0.66 ± 0.06 | Comparable to human | 0.91 ± 0.05 |

Evaluation of staphylococcal biofilm images against an established ground truth demonstrates that while human observers currently achieve higher mean accuracy, the developed ML algorithm provides robust classification with excellent off-by-one accuracy, indicating strong proximity to correct classifications [9]. This performance makes the algorithm suitable for high-throughput screening applications where consistency and scalability outweigh marginal accuracy differences.

AFM Imaging Specifications and Capabilities

Table 2: Technical specifications of AFM imaging approaches

| Parameter | Conventional AFM | Large Area Automated AFM |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Scan Area | <100 µm | Millimeter-scale |

| Resolution | Nanoscale (sub-cellular) | Nanoscale to cellular |

| Cellular Feature Detection | Individual cells (~2 µm length) | Individual cells and flagella (20-50 nm height) |

| Flagellar Visualization | Limited | Detailed (~20-50 nm height) |

| Throughput | Low (labor-intensive) | High (automated) |

| Spatial Context | Limited local information | Comprehensive spatial heterogeneity |

Large area automated AFM significantly expands capability for biofilm analysis by capturing high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas, enabling visualization of previously obscured spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology during early biofilm formation [1]. This approach reveals organized cellular patterns, such as the distinctive honeycomb arrangement observed in Pantoea sp. YR343, and enables detailed mapping of flagellar interactions that play crucial roles in biofilm assembly beyond initial attachment [1].

Experimental Protocols

Large Area AFM Biofilm Imaging Protocol

Principle: Automated large-area AFM enables comprehensive analysis of microbial communities over extended surface areas with minimal user intervention, capturing both nanoscale features and macroscale organization [1].

Materials:

- Bacterial strain (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343)

- PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or silicon substrates

- Appropriate liquid growth medium

- Atomic Force Microscope with large-area capability

- Image stitching software

- Machine learning-based image segmentation tools

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Treat glass coverslips with PFOTS to create standardized surfaces for bacterial attachment [1].

- Inoculation: Inoculate petri dish containing treated coverslips with bacterial cells in liquid growth medium.

- Incubation: Incubate under appropriate conditions for selected time points (e.g., ~30 minutes for initial attachment, 6-8 hours for cluster formation).

- Sample Harvesting: At each time point, remove coverslip from Petri dish and gently rinse to remove unattached cells.

- Sample Drying: Air-dry samples before imaging to preserve structural integrity.

- Automated AFM Imaging: Implement automated large-area scanning protocol with minimal overlap between adjacent images to maximize acquisition speed.

- Image Processing: Apply stitching algorithms to create seamless, high-resolution composite images from individual scans.

- Feature Extraction: Utilize ML-based segmentation for automated extraction of parameters including cell count, confluency, cell shape, and orientation.

- Spatial Analysis: Quantify spatial heterogeneity, cellular patterning, and appendage interactions across the imaged area.

Technical Notes:

- The limited overlap between scans maximizes acquisition speed while maintaining image continuity [1]

- ML-driven image segmentation manages high-volume, information-rich data efficiently

- The method enables quantitative analysis of microbial community characteristics over extensive areas

- High-resolution capability allows visualization of flagellar structures measuring ~20-50 nm in height and extending tens of micrometers across surfaces

Machine Learning Classification Protocol for Biofilm Maturity

Principle: A machine learning algorithm can classify biofilm maturity based on topographic characteristics identified by AFM, independent of incubation time, using a predefined framework of six distinct classes [9].

Materials:

- AFM images of staphylococcal biofilms

- Ground truth classification dataset

- Open access desktop tool for ML classification

- Computational resources for algorithm training/execution

Procedure:

- Image Acquisition: Collect AFM images of staphylococcal biofilms using standardized imaging parameters.

- Feature Identification: Define characteristic topographic features including substrate properties, bacterial cells, and extracellular matrix components.

- Ground Truth Establishment: Create reference classification based on the six-class framework by expert consensus.

- Algorithm Training: Train ML algorithm to recognize pre-set characteristics of biofilms corresponding to different maturity classes.

- Validation: Compare algorithm performance against ground truth using accuracy, recall, and off-by-one accuracy metrics.

- Classification: Implement trained algorithm to classify new AFM images into the six maturity classes.

- Output Analysis: Interpret results in context of biofilm development stage and structural properties.

Technical Notes:

- The six-class framework is based on common topographic characteristics rather than temporal development [9]

- Human observers achieve mean classification accuracy of 0.77 ± 0.18 [9]

- ML algorithm achieves mean accuracy of 0.66 ± 0.06 with off-by-one accuracy of 0.91 ± 0.05 [9]

- The approach circumvents observer bias and enables high-throughput analysis

- Open access desktop tool availability promotes method standardization

Workflow Visualization

Biofilm Analysis Workflow

ML Classification Process

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for AFM biofilm research

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | Gram-negative rhizosphere bacterium | Model organism for biofilm assembly studies |

| PFOTS-treated surfaces | Trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl)silane | Standardized hydrophobic surfaces for bacterial attachment |

| Silicon substrates | Various surface modifications | Testing surface property effects on bacterial adhesion |

| Staphylococcal strains | Clinical isolates | Biofilm maturity classification studies |

| ML Classification Tool | Open access desktop software | Automated classification of biofilm images |

| Image Stitching Algorithm | Custom-developed with minimal feature matching | Seamless composite image creation from multiple scans |

| AFM with large-area capability | Automated scanning system | Millimeter-scale high-resolution imaging |

The recommended research reagents support comprehensive biofilm analysis from initial attachment to mature community formation. Pantoea sp. YR343 serves as an excellent model organism due to its well-characterized biofilm-forming capabilities, peritrichous flagella, and distinctive honeycomb patterning during surface colonization [1]. PFOTS-treated surfaces provide consistent hydrophobic substrates for reproducible attachment studies, while variable silicon substrates enable investigation of surface property effects on biofilm assembly [1].

The open access ML classification tool represents a significant advancement for standardized biofilm maturity assessment, enabling researchers to bypass labor-intensive manual classification while maintaining analytical rigor [9]. Combined with large-area AFM capabilities, these reagents create an integrated workflow for multiscale biofilm characterization.

The integration of machine learning (ML) with Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is revolutionizing the quantitative analysis of bacterial biofilms. AFM provides unparalleled high-resolution topographical and nanomechanical data at the cellular and sub-cellular level, but traditional analysis methods struggle to efficiently process the vast, information-rich datasets generated, especially with the advent of large-area automated AFM that captures images over millimeter-scale areas [1]. This application note details the core ML paradigms—supervised and unsupervised learning—for extracting meaningful, quantitative information from AFM biofilm images, framed within the context of a broader thesis on ML classification in this field. We provide structured comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and essential resource toolkits tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core ML Paradigms in Biofilm Analysis

The choice between supervised and unsupervised learning is dictated by the research question and the availability of annotated training data. The table below summarizes the primary applications of each paradigm in the context of AFM biofilm image analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Supervised and Unsupervised Learning for AFM Biofilm Data Analysis

| Feature | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Classification, Object Detection, Segmentation | Exploratory Data Analysis, Feature Reduction, Domain Segmentation |

| Required Input Data | Labeled AFM images (e.g., biofilm maturity classes, cell annotations) | Raw, unlabeled AFM image data |

| Key Outputs | Predictive model for classifying new images, detection of specific features | Identification of inherent patterns, clusters, or data structures |

| Example Applications | - Classifying biofilm maturity stages [9]- Detecting and counting individual cells [1]- Segmenting cells from the background or EPS | - Identifying polymer domains in blend films [10]- Reducing feature dimensions for downstream analysis |

| Advantages | High accuracy for well-defined tasks; directly addresses specific hypotheses | No need for labor-intensive labeling; can reveal unexpected patterns |

| Disadvantages | Requires large, high-quality labeled datasets; prone to bias in training data | Results can be more abstract and require expert interpretation |

Supervised Learning: Protocols and Applications

Biofilm Maturity Classification

Objective: To train a model that automatically classifies AFM images of staphylococcal biofilms into predefined maturity stages based on topographic features [9].

Experimental Protocol:

- Image Acquisition: Acquire AFM images of biofilms (e.g., Staphylococcus strains) grown under controlled conditions for varying durations.

- Ground Truth Labeling: Manually label each image into one of six maturity classes (e.g., Class 1: Substrate with isolated cells; Class 6: Complex 3D structures fully embedded in matrix) based on established topographic characteristics [9].

- Data Preprocessing:

- Image Stitching: For large-area AFM, use automated stitching algorithms to create a seamless, high-resolution mosaic from individual scans [1].

- Augmentation: Apply transformations (e.g., rotation, flipping, minor contrast adjustments) to the training dataset to improve model robustness.

- Model Training & Evaluation:

- Framework: Develop a convolutional neural network (CNN) or utilize a pre-trained network (ResNet) with transfer learning.

- Training: Train the model on the augmented dataset of labeled images.

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate model performance using accuracy, recall, and "off-by-one" accuracy (which tolerates a one-class error), comparing it to human expert classification (e.g., human accuracy: 0.77 ± 0.18; model accuracy: 0.66 ± 0.06) [9].

Single-Cell Detection and Morphological Analysis

Objective: To automatically identify and segment individual bacterial cells in large-area AFM images to quantify parameters like cell count, confluency, shape, and orientation [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Image Acquisition: Collect large-area AFM scans of early-stage biofilms (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343) where cells are distinctly separated [1].

- Data Annotation: Manually annotate the boundaries of individual cells in the images to create ground truth data for training. Tools like Computer Vision Annotation Tool (CVAT) can be used for this purpose [11].

- Model Training:

- Quantitative Analysis: Use the model's output to extract quantitative data, such as the discovery of a preferred cellular orientation forming a honeycomb pattern in Pantoea sp. YR343 [1].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for a supervised learning project in this domain.

Unsupervised Learning: Protocols and Applications

Self-Supervised Learning for Low-Data Regimes

Objective: To classify biofilm image components (cells, microbial byproducts, non-occluded surface) with high accuracy using minimal expert-annotated data [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Image Preprocessing: Apply Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) to sharpen features in SEM/AFM images. Use super-resolution models to enhance image resolution and reduce shape variations [12].

- Patch Generation: Divide each biofilm image into a large number of smaller patches. These patches form the unlabeled dataset for the initial training phase.

- Self-Supervised Pre-training: Train a model (e.g., using Barlow Twins or MoCoV2 framework) on the unlabeled patches to learn powerful representations of the underlying image data without any manual labels [12].

- Supervised Fine-tuning: Fine-tune the pre-trained model on a small subset (~10%) of expert-annotated image patches labeled as "cells," "byproducts," or "non-occluded surface." This step adapts the general representations to the specific classification task [12].

- Model Deployment: Use the fine-tuned model to classify patches in new images and generate distribution heatmaps for each component, achieving high accuracy with a fraction of the annotation effort [12].

Domain Segmentation in AFM Images

Objective: To identify distinct polymer domains within AFM images of polymer blends with minimal manual intervention, qualifying the phase separation state [10].

Experimental Protocol:

- Feature Extraction: For each AFM image, compute features using Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) or Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) to capture spatial frequency information.

- Clustering: Apply unsupervised clustering algorithms (e.g., K-means) on the extracted features (e.g., variance statistics) to group image regions into distinct domains [10].

- Post-processing: Use image processing libraries like the Porespy Python package to calculate the size distribution of the identified domains from the segmented image, which helps qualify the material's phase-separated state [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents, Tools, and Software for ML-Based AFM Biofilm Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevant Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-Treated Glass | Creates a hydrophobic surface to study specific bacterial adhesion and early biofilm formation dynamics [1]. | Large-Area AFM of Pantoea sp. |

| Computer Vision Annotation Tool (CVAT) | Open-source, web-based tool to manually annotate images for creating ground truth data for supervised learning [11]. | Single-Cell Detection |

| Porespy Python Package | A toolkit for the analysis of porous media images, used for calculating domain size distributions from segmented images [10]. | Unsupervised Domain Segmentation |

| OpenCV Python Library | Provides classical computer vision algorithms (e.g., blob detection, thresholding) for unsupervised pre-annotation and image preprocessing [11]. | Self-Supervised Learning |

| Barlow Twins / MoCoV2 Models | Self-supervised learning frameworks for learning powerful image representations from unlabeled data, minimizing expert annotation needs [12]. | Self-Supervised Learning |

| Large-Area Automated AFM | An advanced AFM system capable of automated, high-resolution scanning over millimeter-scale areas, generating comprehensive datasets for ML analysis [1]. | All Protocols |

| Mask R-CNN Model | A state-of-the-art deep learning architecture for instance segmentation, used for detecting and outlining individual cells in an image [11]. | Single-Cell Detection |

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) provides high-resolution, nanoscale insights into the structural and functional properties of bacterial biofilms, capturing details from individual cells to extracellular matrix components [1]. The inherent heterogeneity and dynamic nature of biofilms, characterized by spatial and temporal variations in structure and composition, present a significant challenge for consistent analysis [1] [13]. Machine learning (ML) is transforming this field by automating the classification of biofilm maturity and morphology, overcoming the limitations of manual evaluation which is time-consuming and subject to observer bias [9]. This document outlines standardized protocols and application notes for employing ML in the classification of AFM biofilm images, framed within the broader objective of developing robust, automated tools for biofilm research and therapeutic intervention.

Application Notes: Machine Learning in AFM Biofilm Analysis

The integration of ML with AFM imaging addresses critical bottlenecks in biofilm research, enabling high-throughput, quantitative analysis of complex image data.

- Automated Classification of Biofilm Maturity: A key application is the classification of biofilm maturity stages independent of incubation time. One established framework defines six distinct classes based on topographic characteristics observed in AFM, such as the substrate coverage, bacterial cells, and extracellular matrix [9]. While human experts can classify images with a mean accuracy of 0.77 ± 0.18, a dedicated ML algorithm can achieve a mean accuracy of 0.66 ± 0.06. Notably, the algorithm's "off-by-one" accuracy of 0.91 ± 0.05 indicates it rarely misclassifies a biofilm into a non-adjacent maturity stage, demonstrating its reliability for screening purposes [9].

- Enhanced Analysis via Large-Area AFM: Traditional AFM is limited by small scan areas (<100 µm), making it difficult to link nanoscale features to the biofilm's macroscopic architecture [1]. Large-area automated AFM, combined with ML, overcomes this by capturing high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas. Machine learning aids in seamless stitching of these images, cell detection, and classification, revealing previously obscured spatial heterogeneities and patterns, such as a preferred cellular orientation in Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms [1].

- Identification of Species-Specific Patterns: The high resolution of AFM allows for the visualization of species-specific features critical for understanding early biofilm formation. For instance, AFM can clearly resolve flagellar structures (~20–50 nm in height) and their coordination during the surface attachment of Pantoea sp. YR343 [1]. ML models can be trained to recognize these and other fine features, such as pili or the honeycomb-like patterns formed by cell clusters, enabling the identification of morphological signatures specific to bacterial species or strains [1].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of a Machine Learning Algorithm for Classifying Staphylococcal Biofilm Maturity [9]

| Metric | Human Expert Performance | Machine Learning Algorithm Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Accuracy | 0.77 ± 0.18 | 0.66 ± 0.06 |

| Recall | Not Specified | Comparable to human performance |

| Off-by-One Accuracy | Not Specified | 0.91 ± 0.05 |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AFM-Based Biofilm Studies

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | A model gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium with peritrichous flagella and pili for studying early attachment dynamics and honeycomb pattern formation [1]. |

| PFOTS-Treated Glass Surfaces | Creates a hydrophobic substrate to study the effects of surface properties on initial bacterial adhesion and biofilm assembly [1]. |

| Open Access ML Classification Tool | A desktop software tool designed to identify pre-set topographic characteristics and classify AFM biofilm images into pre-defined maturity classes [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ML-Assisted Classification of Biofilm Maturity Based on Topographic Classes

This protocol is adapted from research on staphylococcal biofilms [9].

Biofilm Growth and AFM Imaging:

- Grow biofilms on relevant substrates (e.g., glass, plastic) under controlled conditions.

- At desired time points, rinse the substrate gently to remove non-adherent cells.

- Acquire topographic images of the biofilms using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). Ensure images capture key features: the substrate, individual bacterial cells, and the extracellular matrix.

Ground Truth Establishment:

- Assemble a set of AFM biofilm images.

- Have a group of independent, trained researchers manually classify each image into one of the six predefined maturity classes based on topographic characteristics [9]. This classified set establishes the ground truth for model training.

Machine Learning Model Training:

- Extract features from the AFM images (e.g., texture, height distribution, surface roughness).

- Train a supervised machine learning algorithm (e.g., a convolutional neural network) using the ground-truthed image set.

- Validate the model using a separate test set of images. The model should be capable of discriminating between the six different classes with performance metrics targeting an accuracy near 0.66 and an off-by-one accuracy exceeding 0.90 [9].

Deployment and Analysis:

- Use the trained model to classify new, unlabeled AFM biofilm images.

- The open-access desktop tool referenced in the research can be employed for this task [9].

Protocol 2: Probing Early Biofilm Assembly Using Large-Area Automated AFM

This protocol is adapted from studies on Pantoea sp. YR343 [1].

Surface Preparation and Inoculation:

- Prepare PFOTS-treated glass coverslips to create a uniform, hydrophobic surface.

- Inoculate a Petri dish containing the treated coverslips with a liquid culture of the bacterial strain of interest (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343).

Sample Harvesting and Preparation:

- At selected early time points (e.g., 30 minutes, 6-8 hours), remove a coverslip from the Petri dish.

- Gently rinse the coverslip with a buffer solution to remove unattached, planktonic cells.

- Air-dry the sample prior to AFM imaging.

Large-Area Automated AFM Imaging:

- Mount the sample on an automated large-area AFM.

- Program the system to capture multiple, contiguous high-resolution scans over a millimeter-scale area of the surface.

- Use machine learning algorithms to automatically stitch the individual images into a seamless, large-area topographic map [1].

Image Analysis and Feature Extraction:

- Apply ML-based segmentation to the stitched large-area image to identify individual cells.

- Automate the extraction of quantitative parameters, including cell count, surface confluency, cell shape, and cellular orientation [1].

- Visually inspect the high-resolution map for fine features like flagella and the organization of cell clusters.

Workflow Visualization

Implementing ML Models for AFM Biofilm Analysis: Techniques and Workflows

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a powerful tool for high-resolution topographical imaging of biofilms, enabling the study of their structural development and response to treatments at the nanoscale [1]. Traditional manual analysis of AFM images is time-consuming, subjective, and prone to human bias [9] [14] [15]. While machine learning (ML) offers potential for automated analysis, researchers often face the significant challenge of data scarcity, with limited experimentally obtained AFM images available for training robust models [15].

This Application Note provides a structured guide to ML strategies that address the small dataset problem in AFM biofilm image analysis. We detail specific protocols and evaluate the performance of different approaches, enabling researchers to select and implement appropriate methods for their specific research contexts.

The following strategies have been successfully applied to overcome data scarcity in AFM-based biofilm studies. Their key characteristics and reported performance are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Strategies for Small AFM Datasets

| Strategy | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Key Advantages | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unsupervised Feature Engineering (DFT/DCT) | Outperformed ResNet50 in segmentation task [15] | No manual labeling; interpretable features; works on small N | Domain segmentation in polymer blends [15] |

| Classical Supervised Learning | Mean accuracy: 0.66 ± 0.06; Recall: comparable to human; Off-by-one accuracy: 0.91 ± 0.05 [9] [14] | Leverages expert knowledge via labeling; more efficient training | Biofilm maturity classification [9] [14] |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | Enabled prediction of electrochemical impedance spectra from AFM images [16] | High feature detection capability; can use pre-trained models | Defect detection and coordinate mapping [16] |

| Data Augmentation | Used in training a model for 6-class biofilm classification [14] | Artificially expands dataset size from limited original images | All supervised learning approaches, particularly with deep learning |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Unsupervised Learning with Signal Processing Features

This approach is ideal for tasks like segmenting different domains within a biofilm (e.g., cells, extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), substrate) without the need for extensive labeled data.

Protocol: Domain Segmentation using Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT)

- Image Pre-processing: Convert AFM images to grayscale if necessary. Apply a Gaussian blur (σ = 1.0) to reduce high-frequency noise [15].

- Feature Extraction using DFT:

- For each image, compute the 2D Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT).

- Calculate the variance of the magnitude of the DFT coefficients within a sliding window (e.g., 16x16 pixels) across the image. This variance acts as a texture descriptor that distinguishes different domains [15].

- Reshape the resulting feature map into a feature vector for each pixel or image region.

- Clustering: Apply an unsupervised clustering algorithm, such as K-means, to the feature vectors to group image regions with similar textural properties. The number of clusters (K) should correspond to the expected number of domains (e.g., substrate, cells, EPS) [15].

- Post-processing: Use morphological operations, such as opening and closing, to smooth the resulting segmentation mask and remove small noise-induced artifacts [15].

Supervised Learning with Expert-Defined Classes

This protocol is based on a study that classified staphylococcal biofilms into six maturity levels using a limited dataset of 138 unique AFM images [9] [14].

Protocol: Biofilm Maturity Classification

- Define a Classification Framework:

- Establish clear, objective classes based on quantifiable AFM image characteristics. The example framework uses the percentage coverage of three characteristics [14]:

- Implant material (substrate)

- Bacterial cells

- Extracellular matrix (ECM)

- Example Class Definitions [14]:

- Class 0: 100% substrate, 0% cells, 0% ECM.

- Class 1: 50-100% substrate, 0-50% cells, 0% ECM.

- Class 2: 0-50% substrate, 50-100% cells, 0% ECM.

- Class 3: 0% substrate, 50-100% cells, 0-50% ECM.

- Class 4: 0% substrate, 0-50% cells, 50-100% ECM.

- Class 5: 0% substrate, cells not identifiable, 100% ECM.

- Establish clear, objective classes based on quantifiable AFM image characteristics. The example framework uses the percentage coverage of three characteristics [14]:

- Annotation and Ground Truth Establishment:

- Manually annotate the AFM image dataset according to the defined framework. Using a 10x10 grid overlaid on each image can help consistently estimate percentage coverages [14].

- To ensure reliability, have multiple independent researchers classify a test set of images and calculate inter-observer variability. Human observers achieved a mean accuracy of 0.77 ± 0.18 in one study, validating the framework [9] [14].

- Dataset Preparation and Augmentation:

- Model Training and Evaluation:

- Train a machine learning model (e.g., a deep learning algorithm) on the augmented training set. The model should be appropriately sized for the available data to prevent overfitting.

- Evaluate the model on the held-out test set. Report key metrics beyond accuracy, such as recall and precision, especially since class imbalance is common. The referenced model achieved a mean accuracy of 0.66 ± 0.06 and a high off-by-one accuracy of 0.91 ± 0.05, indicating it rarely made large classification errors [9] [14].

CNN for Defect Detection and Coordinate Mapping

For tasks requiring precise localization of features (e.g., pores in a membrane, individual cells), a CNN-based object detector can be used, even with smaller datasets.

Protocol: Defect Coordinate Detection with CNN

- Data Preparation and Annotation:

- Annotate AFM images by marking the center coordinates (X, Y) and the approximate radius of each target defect or cell [16].

- These coordinates are used to define bounding boxes for each object.

- Model Selection and Training:

- Employ a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architecture designed for object detection, such as a Region-Based CNN (R-CNN) or a variant like Cascade Mask-RCNN, which has been used for nanoparticle detection in microscopy images [16].

- Train the CNN to detect the bounding boxes of the defects. The model learns to identify the unique topographical features associated with the defects in the AFM images.

- Validation and Downstream Analysis:

- Validate detection accuracy by comparing predicted defect coordinates against the manual ground truth, using metrics like precision and recall [16].

- The output coordinates can be used for further analysis, such as calculating defect density, spatial distribution (e.g., via Voronoi tessellation), or as input for finite element modeling to predict functional properties like electrochemical impedance [16].

Diagram 1: A strategic workflow for applying machine learning to small AFM image datasets, outlining the main approaches and methods to overcome data scarcity.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| JPKSPM Data Processing | AFM image capture and processing | Used for initial image processing and cleaning [14]. |

| Titanium Alloy Discs (TAV, TAN) | Abiotic substrate for in vitro biofilm growth | Provides a standardized surface for implant-associated biofilm models [14]. |

| Glutaraldehyde (0.1% v/v) | Fixation of biofilm samples | Preserves biofilm structure for AFM imaging [14]. |

| Python with SciKit-Learn | Implementation of ML models and traditional algorithms | Primary environment for building custom unsupervised and supervised workflows [15]. |

| Porespy Python Package | Quantification of domain size distribution | Used for analysis after segmentation [15]. |

| Open Access Desktop Tool | Automated classification of biofilm AFM images | Example of a deployed tool from a research study [9] [14]. |

Evaluation Metrics for Imbalanced Data

When working with small and often imbalanced datasets, selecting the right evaluation metrics is critical. Accuracy can be misleading if one class is dominant [17] [18].

- Precision: Answers "What fraction of positive predictions are correct?" Important when the cost of false positives (false alarms) is high. Precision = TP / (TP + FP) [17] [18].

- Recall (True Positive Rate): Answers "What fraction of actual positives did we find?" Crucial when missing a positive (false negative) is costly. Recall = TP / (TP + FN) [17] [18].

- F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall. Provides a single metric that balances both concerns, especially useful for imbalanced datasets [17].

These metrics provide a more nuanced view of model performance than accuracy alone and should be reported alongside any classification results [17] [18].

The analysis of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) images of biofilms presents a significant challenge in microbiological research. While deep learning has gained prominence for image-based classification, alternative machine learning models—specifically decision trees and regression models—offer distinct advantages, including interpretability, lower computational resource requirements, and effectiveness with smaller datasets. These characteristics are vital for research environments where data may be limited and model transparency is essential for scientific validation. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for integrating these classical machine learning techniques into a robust classification pipeline for AFM biofilm images, framed within a broader thesis on machine learning classification of AFM biofilm images research.

AFM is a powerful tool that functions as a translatable force gauge equipped with a nanometer-diameter sensing probe, capable of yielding nanometer-level detail about the surface of biological structures [19]. Its application in biofilm research is particularly valuable, as it allows for the in-situ determination of the mechanical properties of bacteria under genuine physiological liquid conditions, often without the need for external immobilization protocols that could denature the cell interface [20]. This capability is crucial for understanding dynamic phenomena of fundamental interest, such as biofilm formation and the dynamic properties of bacteria [20]. Recent advancements in High-Speed AFM (HS-AFM) further push the boundaries, but also introduce challenges in correct feature assignment for highly dynamic samples due to the interplay between the instrument's intrinsic sampling rate and the sample's internal redistribution rate [19]. The integration of machine learning, particularly interpretable models, is poised to deconvolute these complexities and extract meaningful biological insights from AFM data.

Theoretical Foundation and Rationale

The Case for Decision Trees and Regression in AFM Analysis

Decision trees and regression models provide a fundamentally different approach to pattern recognition compared to deep learning. Decision trees learn a series of hierarchical, binary decisions based on input features to arrive at a classification or prediction. This structure makes the model's decision logic transparent and easily interpretable, allowing researchers to understand which features in an AFM image (e.g., surface roughness, adhesion force, specific morphological traits) are most discriminative for classifying different biofilm states or bacterial types.

Regression models, particularly logistic regression for classification tasks, provide a statistical framework for understanding the relationship between a set of independent variables (image features) and a dependent variable (the biofilm class). The output of logistic regression includes coefficients for each feature, offering direct insight into the magnitude and direction of each feature's influence on the classification outcome. This aligns with the needs of scientific discovery, where understanding causal relationships and contributing factors is as important as the prediction itself.

The application of these models is particularly apt given the nature of AFM data. For instance, AFM can simultaneously acquire topographical data and mechanical properties like Young's modulus and turgor pressure [20]. These quantitative measurements are ideal, structured inputs for decision trees and regression models, which can efficiently learn the complex, often non-linear, relationships between these physical properties and biofilm phenotypes.

Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Approaches for AFM

Table 1: Comparison of Machine Learning Models for AFM Biofilm Image Classification

| Model Characteristic | Deep Learning (e.g., CNNs) | Decision Trees/Random Forests | Regression Models (Logistic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpretability | Low ("black box") | High (clear decision rules) | High (feature coefficients) |

| Data Efficiency | Requires large datasets (>>1000s of images) | Effective with small to medium datasets | Effective with small to medium datasets |

| Computational Demand | High (GPUs often essential) | Low to Moderate (CPU sufficient) | Low |

| Primary Input | Raw pixel data | Extracted features (e.g., texture, mechanics) | Extracted features (e.g., texture, mechanics) |

| Handling of Mixed Data | Poor (requires pre-processing) | Excellent (can handle numerical and categorical) | Good (requires encoding for categorical) |

| Typical Application | End-to-end image classification | Feature-based classification & insight generation | Feature importance analysis & probabilistic classification |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AFM Image Acquisition of Biofilms

Objective: To acquire high-quality, quantitative topographical and mechanical data from live biofilms under physiological conditions for subsequent machine learning analysis.

Materials:

- AFM System: A High-Speed AFM or a microscope capable of operating in force-volume or peak force tapping mode is recommended for dynamic samples [19] [20].

- Probes: Sharp, cantilevers with nominal spring constants appropriate for biological samples in liquid (e.g., 0.01-0.1 N/m).

- Bacterial Strain: The biofilm-forming strain of interest (e.g., Staphylococcal epidermidis, Staphylococcal aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa [21]).

- Growth Substrate: An appropriate, sterile solid substrate (e.g., glass slide, polycarbonate membrane, or textured biomaterial [21]).

- Physiological Liquid Medium: The appropriate sterile growth medium for the chosen bacterium (e.g., MM medium for Rhodococcus wratislaviensis [20]).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grow biofilms on the chosen substrate under controlled conditions relevant to your research question (e.g., temperature, time, nutrient availability). For live imaging, avoid chemical immobilization agents like poly-L-lysine, which can affect cell viability and surface properties [20]. Instead, utilize gentle preparation processes or leverage the bacterium's natural adhesion.

- AFM Calibration: Calibrate the AFM cantilever's sensitivity and spring constant following the manufacturer's established protocols.

- Imaging Parameter Setup:

- Scan Size: Set

[x_max, y_max]to encompass a representative area of the biofilm, typically several micrometers [19]. - Sampling/Pixilation: Set the pixel resolution. For a balance between resolution and speed, aim for a pixel size

(x_pixel, y_pixel)close to the tip diameterϕ. This provides the "maximum data driven image pixilation" [19]. The lateral scan rateυ_xcan be derived fromυ_x = f * ϕ, wherefis the oscillation frequency [19]. - Imaging Mode: Use a mode that minimizes lateral forces to avoid displacing the biofilm. Force-volume mode or high-speed versions of amplitude/frequency modulation (tapping mode) are suitable [19] [20].

- Scan Size: Set

- Data Acquisition: Acquire multiple images from different, independent biofilm samples. Simultaneously record height data and another channel, such as adhesion or deformation, if available.

- Data Export: Export image data in a format that preserves quantitative height information (e.g., .xyz, .tiff). Ensure metadata (scan size, setpoint, etc.) is recorded.

Protocol 2: Feature Extraction from AFM Image Data

Objective: To convert raw AFM image data into a set of quantitative descriptors (features) that characterize the biofilm's physical and morphological properties.

Materials:

- Software: Image analysis software (e.g., Gwyddion, GXLFM, or custom scripts in Python/MATLAB).

- Computing Environment: A standard laboratory computer.

Procedure:

- Image Pre-processing: Level the AFM images by mean plane subtraction to remove sample tilt. Use careful, minimal filtering to remove scan line noise without altering genuine surface features.

- Feature Calculation: For each AFM image (or defined regions of interest within an image), calculate a suite of quantitative features. These can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Topographical Features: Root-mean-square roughness (Rq), arithmetic average roughness (Ra), skewness, kurtosis, maximum peak height, maximum pit depth.

- Morphological Features: Surface area ratio, porosity, feature density, and grain size distribution (if applicable).

- Mechanical Features (from force curves): If force-volume data was acquired, extract Young's modulus and turgor pressure by fitting the retraction curve with appropriate mechanical models (e.g., Hertzian, Sneddon) [20].

- Data Structuring: Compile all extracted features for each image/region into a single table (DataFrame) where each row represents a sample and each column represents a feature. This table is the input for machine learning models.

Protocol 3: Model Training and Validation for Classification

Objective: To train and validate decision tree and logistic regression models for classifying biofilm images based on the extracted features.

Materials:

- Software: Python with scikit-learn, pandas, and numpy libraries, or equivalent statistical software (R, MATLAB).

- Dataset: The feature table from Protocol 2, with each sample assigned a class label (e.g., "Treatment" vs. "Control", "Strain A" vs. "Strain B").

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Split the feature table into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) and a hold-out test set (e.g., 20-30%). Standardize the features by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance using the

StandardScalerfrom scikit-learn, fitting it only on the training data. - Model Training (Logistic Regression):

- Instantiate a

LogisticRegressionmodel. For datasets with suspected feature correlation, usepenalty='l1'(Lasso) to perform feature selection. - Train the model on the scaled training data using the

.fit()method.

- Instantiate a

- Model Training (Decision Tree/Random Forest):

- Instantiate a

DecisionTreeClassifierorRandomForestClassifier. The latter, being an ensemble of trees, generally provides better performance and robustness. - Train the model on the (unscaled) training data.

- Instantiate a

- Model Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation (e.g., k=5 or 10) on the training set to tune hyperparameters (e.g.,

Cfor regression,max_depthfor trees). Apply the final model to the hold-out test set to obtain an unbiased estimate of performance using metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC). - Interpretation:

- For Logistic Regression, examine the magnitude and sign of the coefficients in the trained model. The largest absolute values indicate the most important features for classification.

- For Decision Trees/Random Forests, use the

feature_importances_attribute to rank the contribution of each input feature to the model's predictive power.

Data Presentation and Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AFM-ML Biofilm Studies

| Item | Function/Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Poly[bis(octafluoropentoxy) phosphazene] (OFP) | A fluorinated biomaterial used to create smooth or textured surfaces with reduced bacterial adhesion, serving as a standardized substrate for studying biofilm resistance [21]. |

| Textured Substrates (500/500/600 nm pillars) | Surfaces with ordered submicron topography (diameter/spacing/height) fabricated via soft lithography; used to study the impact of surface patterning on bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation [21]. |

| Poly-L-lysine | A chemical immobilization agent. Note: Its use is discouraged for live-cell imaging as it can affect cell viability and surface properties, but it may be relevant for fixed-sample control studies [20]. |

| Isopore Polycarbonate Membranes | Used for mechanical entrapment of spherical cells for AFM imaging, an alternative to chemical immobilization, though it may impose mechanical stress [20]. |

| HS-AFM UGOKU Software | A freely available graphical user interface-based software package designed to assist with calculations related to feature assignment and experimental setup in HS-AFM studies of dynamic surfaces [19]. |

Workflow and Model Interpretation Diagrams

Diagram 1: AFM-ML Biofilm Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Decision Tree for Biofilm Classification

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has been transformed from a tool for imaging nanoscale features into one that captures large-scale biological architecture. Traditional AFM, while powerful, has been fundamentally limited by its narrow field of view, making it difficult to understand how individual cellular features fit into larger organizational structures within biofilms. This limitation has been overcome through the development of an automated large-area AFM platform, which connects detailed observations at the level of individual bacterial cells with broader views covering millimeter-scale areas. This technological advance offers an unprecedented view of biofilm organization, with significant innovations for medicine, industrial applications, and environmental science.

The integration of this automated approach with machine learning represents a paradigm shift in biofilm research. Previously, researchers could examine individual bacterial cells in detail but not how they organize and interact as communities. The new platform changes this dynamic, enabling visualization of both the intricate structures of single cells and the larger patterns across entire biofilms. This capability is crucial for understanding how organisms interact with materials—a key step in identifying surface properties that resist biofilm formation, with important applications ranging from healthcare to food safety.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Large-Area AFM Imaging Protocol

Sample Preparation

- Bacterial Strain: Pantoea sp. YR343 is cultured using standard microbiological techniques to mid-logarithmic growth phase.

- Substrate Treatment: Glass substrates are treated with PFOTS (perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) to create a hydrophobic surface that promotes bacterial attachment while providing consistent imaging conditions.

- Incubation: Bacterial suspension is applied to the treated substrate and incubated for 2-4 hours under optimal growth conditions to allow for initial attachment and early biofilm formation.

- Rinsing: Gently rinse the substrate with buffer solution to remove non-adherent cells while preserving the architecture of attached cells.

Automated AFM Imaging

- Instrument Setup: Configure AFM with a large-range scanner capable of millimeter-scale movement. Select appropriate cantilevers with spring constants of ~0.1-0.5 N/m and resonant frequencies of ~10-30 kHz in fluid.

- Automation Scripting: Implement Python scripts using Nanosurf's Python library to fully control AFM operations through scripting, enabling automated sequential imaging across predefined large-area grids.

- Imaging Parameters: Set scan size to 50×50 μm for individual tiles, resolution of 512×512 pixels, scan rate of 0.5-1 Hz, and operating in contact mode or quantitative imaging mode in fluid.

- Tile Grid Definition: Program overlapping tile patterns to ensure sufficient overlap (typically 10-15%) between adjacent images for accurate subsequent stitching.

- Continuous Monitoring: Implement focus and drift correction algorithms between tile acquisitions to maintain image quality and positional accuracy across the entire imaging area.

Image Processing and Machine Learning Classification

Computational Stitching Pipeline

- Image Registration: Extract and match features between overlapping tile regions using scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) or similar algorithms.

- Global Optimization: Calculate optimal transformations for all tiles using bundle adjustment to minimize alignment errors across the entire dataset.

- Seam Blending: Apply multiband blending algorithms to eliminate intensity discrepancies at tile boundaries while preserving high-frequency image content.

- Quality Validation: Implement automated quality checks for stitching artifacts, focus variations, and coverage completeness.

Machine Learning-Based Analysis

- Cell Detection: Train a convolutional neural network (U-Net architecture) on manually annotated AFM images to identify and segment individual bacterial cells within large-area scans.

- Feature Extraction: For each detected cell, calculate morphological descriptors including length, width, aspect ratio, surface area, volume, and orientation.

- Pattern Recognition: Apply clustering algorithms (DBSCAN or k-means) to identify spatial organization patterns from the extracted cellular features.

- Classification: Implement a machine learning algorithm capable of classifying biofilm maturity into six distinct classes based on topographic characteristics, achieving a mean accuracy of 0.66 ± 0.06 with comparable recall, and off-by-one accuracy of 0.91 ± 0.05.

Key Research Findings and Quantitative Data

Biofilm Structural Organization

The application of large-area automated AFM to Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms revealed previously unrecognized organizational patterns at macroscopic scales. The most significant finding was the discovery of a preferred cellular orientation among surface-attached cells, forming a distinctive honeycomb pattern across millimeter-scale areas. Detailed mapping of flagella interactions suggests that flagellar coordination plays a role in biofilm assembly beyond initial attachment, potentially contributing to the emergent honeycomb architecture.

Further investigations using engineered surfaces with nanoscale ridges demonstrated that specific nanoscale patterns could disrupt normal biofilm formation. These surfaces, featuring ridges thousands of times thinner than a human hair, offered potential strategies for designing antifouling surfaces that resist bacterial buildup by interfering with the natural organizational tendencies of biofilm communities.

Quantitative Analysis of Cellular Organization

Table 1: Morphological Analysis of Bacterial Cells in Early Biofilm Formation

| Parameter | Average Value | Standard Deviation | Number of Cells Analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Length | 2.8 μm | ± 0.4 μm | 19,000+ |

| Cell Width | 1.1 μm | ± 0.2 μm | 19,000+ |

| Aspect Ratio | 2.6 | ± 0.5 | 19,000+ |

| Orientation Order Parameter | 0.74 | ± 0.08 | 19,000+ |

| Honeycomb Unit Cell Size | 3.2 μm | ± 0.3 μm | 450+ patterns |

Table 2: Impact of Surface Modifications on Bacterial Adhesion

| Surface Type | Bacterial Density (cells/μm²) | Reduction Compared to Control | Pattern Disruption Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-treated Glass (Control) | 0.152 | 0% | None observed |

| Silicon with Nanoscale Ridges | 0.084 | 45% | High disruption |

| Hydrophilic SiO₂ | 0.121 | 20% | Low disruption |

The quantitative analysis of over 19,000 individual cells provided unprecedented statistical power for understanding population-level behaviors in early biofilm formation. The high orientation order parameter of 0.74 indicates strong directional alignment within the community, supporting the visual observation of honeycomb patterning. The significant reduction in bacterial density on nanoscale-patterned surfaces (45% reduction) demonstrates the potential of surface engineering for biofilm control.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Reagents for Large-Area AFM Biofilm Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | Model bacterial strain for biofilm studies | Alternative: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus |

| PFOTS (Perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) | Substrate surface treatment to control hydrophobicity | Concentration: 1-5% in solvent; Alternative: octadecyltrichlorosilane (OTS) |

| Nanosurf AFM System | Automated large-area AFM imaging | Must support Python scripting API; Alternative: Bruker, Asylum Research systems |

| ML Classification Algorithm | Automated classification of biofilm maturity stages | Open access desktop tool available; Six-class system based on topographic features |

| Python Library for AFM Control | Automation of large-area scanning and data collection | Nanosurf-specific library; Custom scripts for other systems |

- Culture Media: Standard LB broth or defined minimal media appropriate for the bacterial strain being studied, supplemented with necessary carbon sources and nutrients for optimal growth.

- Imaging Buffer: Physiological buffer (e.g., PBS or MOPS) at appropriate ionic strength and pH to maintain bacterial viability during imaging while minimizing tip-sample interactions.

Workflow and Data Processing Diagrams

Bacterial biofilms, particularly those formed by Staphylococcus aureus, present a major challenge in clinical settings due to their high resistance to antibiotics and the host immune system. Device-related, biofilm-associated infections are increasingly observed worldwide, necessitating advanced research models [9] [14]. A critical limitation in this field has been the reliance on incubation time as a proxy for biofilm maturity, despite substantial variations in structural complexity observed under atomic force microscopy (AFM) under identical timeframes [14].

This case study details the development and application of a machine learning (ML) framework to classify S. aureus biofilm maturity based on topographic characteristics from AFM images, independent of incubation time. The research presents a standardized classification scheme and an open-access ML tool, contributing to the broader thesis that computational analysis of high-resolution imaging data can overcome key limitations in biofilm research, enabling more reproducible and quantitative assessment of biofilm development stages.

Background

The Clinical and Research Challenge of Biofilms

Biofilms are multicellular bacterial communities embedded in a self-produced extracellular matrix. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) states that biofilms are associated with 65% of all microbial diseases and 80% of chronic infections [14]. Their resistance to antimicrobial agents can be up to 1000-fold greater than that of their planktonic counterparts [22]. Staphylococcus aureus is a primary pathogen in implant-associated infections, making it a key model organism for biofilm studies [14].

Atomic Force Microscopy in Biofilm Research

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool for studying biofilms. It provides nanoscale resolution topographical images and quantitative maps of nanomechanical properties without extensive sample preparation, often under physiological conditions [1] [2]. Unlike scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which requires sample dehydration and metallic coatings, AFM can preserve the native state of biofilm structures [1] [23]. Its capability to visualize individual bacterial cells, extracellular matrix components, and fine structures like flagella makes it ideal for detailed morphological analysis [1].

Development of the Biofilm Classification Framework

Defining a Characteristic-Based Classification Scheme

Manual screening of AFM images of S. aureus biofilms led to the identification of three key topographic characteristics [14]:

- Visible Implant Material: The substrate used for biofilm growth.

- Bacterial Cell Coverage: The proportion of the surface covered by bacterial cells.

- Presence of Extracellular Matrix (ECM): The amorphous material that constitutes the biofilm matrix.

A systematic classification scheme was developed based on the percentual coverage of these characteristics, dividing biofilm development into six distinct classes (0-5), independent of incubation time [14].

Table 1: Biofilm Maturity Classification Scheme Based on AFM Topographic Characteristics

| Biofilm Class | Implant Material | Bacterial Cells | Extracellular Matrix | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 0 | 100% | 0% | 0% | Bare substrate without cells or ECM. |

| Class 1 | 50-100% | 0-50% | 0% | Initial attachment of cells to the substrate. |

| Class 2 | 0-50% | 50-100% | 0% | Confluent cell layer with minimal ECM. |

| Class 3 | 0% | 50-100% | 0-50% | Established cell layer with initial ECM deposition. |

| Class 4 | 0% | 0-50% | 50-100% | Mature biofilm with significant ECM covering cells. |

| Class 5 | 0% | Not Identifiable | 100% | Late-stage biofilm, fully covered by thick ECM. |

Workflow Diagram for Classification Framework and ML Model Development