Metabolic Activity Dyes for Bacterial Viability Assessment: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of metabolic activity dyes for assessing bacterial viability, a critical technique for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Metabolic Activity Dyes for Bacterial Viability Assessment: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of metabolic activity dyes for assessing bacterial viability, a critical technique for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of how dyes like tetrazolium salts and fluorescein diacetate interact with bacterial metabolism. The content explores methodological applications across various bacterial species and experimental setups, including advanced techniques like single-cell analysis via dark-field microscopy. A dedicated section addresses common challenges, optimization strategies, and pitfalls in dye selection and protocol execution. Finally, the article validates these methods through comparative analysis with other viability criteria, such as culturability and membrane integrity, and discusses their power in detecting viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells.

The Science Behind the Stain: How Metabolic Dyes Interact with Bacterial Physiology

The accurate determination of bacterial viability is fundamental to public health microbiology, pharmaceutical development, and clinical diagnostics. For over a century, the gold standard for viability assessment has been bacterial culturability on solid media, which measures the ability of a single bacterial cell to reproduce and form a visible colony [1]. However, a significant limitation of this approach is its inability to detect viable but nonculturable (VBNC) bacteria, which are metabolically active cells that have entered a dormant state in response to environmental stresses such as low temperatures, nutrient deprivation, or high antibiotic concentrations [1]. These VBNC cells do not divide on conventional culture media but maintain metabolic activity and can potentially resuscitate under favorable conditions, posing a significant infectious risk that goes undetected by traditional methods.

To address this critical gap, assessment of metabolic activity has emerged as a powerful proxy for determining true bacterial viability. Metabolic activity serves as a direct indicator of cellular life processes, reflecting the functional state of enzymes, membrane transport systems, and energy generation pathways [2]. This Application Note details the theoretical foundation, practical protocols, and key applications of metabolic activity assays for comprehensive bacterial viability assessment, providing researchers with robust methodologies that complement and extend beyond traditional culturability approaches.

Theoretical Foundation: Metabolic Activity as a Viability Proxy

The Three Pillars of Viability Assessment

Current viability assessment strategies are built upon three accepted criteria, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

- Culturability: Based on reproductive capacity and colony formation. It provides definitive evidence of viability but fails to detect VBNC cells and requires extended time periods (24 hours to several weeks) [1].

- Metabolic Activity: Measures ongoing biochemical processes including substrate uptake, enzyme activity, and respiration. It successfully detects VBNC bacteria and can provide results within hours, but may not detect dormant cells with temporarily silenced metabolism [1].

- Membrane Integrity: Assesses the structural integrity of the cellular membrane, a fundamental characteristic of living cells. It can detect dormant cells but typically requires multiple processing steps and specialized instrumentation [1].

Metabolic activity assays are particularly valuable as they probe the functional biochemical processes essential for cellular maintenance and growth, providing a more immediate and comprehensive assessment of bacterial viability than culturability alone.

Key Metabolic Pathways as Viability Indicators

Several core metabolic processes serve as excellent indicators of bacterial viability, each measurable through specific assay technologies:

Redox Activity and Electron Transport System Function The bacterial electron transport system (ETS) is central to energy metabolism in viable cells. Tetrazolium salts and resazurin-based dyes serve as artificial electron acceptors that are reduced by active ETS components, particularly through the action of NADH- and NADPH-dependent oxidoreductases and dehydrogenases [2]. This reduction generates quantifiable colorimetric or fluorescent signals proportional to the number of metabolically active cells present [2].

Membrane Transport Function Viable bacteria with intact membrane transport systems actively take up and metabolize various substrates from their environment. The hydrolysis of fluorescein diacetate (FDA) by nonspecific intracellular enzymes (esterases, lipases, proteases) exemplifies this principle, where the nonpolar, nonfluorescent FDA molecule passively diffuses across intact membranes and is converted to fluorescent fluorescein that accumulates within viable cells [1].

Respiratory Activity Aerobic bacteria consume oxygen during respiration, creating measurable changes in dissolved oxygen concentration in their immediate environment. This oxygen consumption can be monitored using oxygen-sensitive fluorophores such as ruthenium tris (2,2'-diprydl) dichloride hexahydrate (RTDP), providing a direct real-time measure of metabolic activity [3].

Metabolic Activity Assay Protocols

Tetrazolium Salt Reduction Assays (MTT/XTT)

Principle Viable bacterial cells with active electron transport systems reduce yellow, water-soluble tetrazolium salts (MTT, XTT) to brightly colored, water-insoluble (MTT) or water-soluble (XTT) formazan products through the action of NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductases [2] [4]. The amount of formazan produced is proportional to the number of metabolically active cells.

Table 1: Tetrazolium Salt Comparison

| Property | MTT | XTT |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Name | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide | 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide |

| Formazan Product Solubility | Insoluble (requires solubilization step) | Soluble in aqueous media |

| Assay Type | End-point measurement | Continuous or end-point measurement |

| Detection Method | Colorimetric (570-590 nm) | Colorimetric (450-500 nm) |

| Typical Incubation Time | 2-4 hours | 1-4 hours |

MTT Assay Protocol [5]

Reagent Preparation:

- Prepare 5 mg/mL MTT solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Filter sterilize and store at -20°C for up to 6 months.

- Prepare MTT solvent: 4 mM HCl, 0.1% NP-40 in isopropanol.

Assay Procedure:

- For bacterial cultures, dispense 100 μL of sample into microplate wells.

- Add 10-20 μL of MTT solution to each well (final concentration 0.5-1 mg/mL).

- Incubate at 37°C for 3 hours protected from light.

- Add 150 μL of MTT solvent to dissolve formazan crystals.

- Wrap plate in foil and shake on orbital shaker for 15 minutes.

- Measure absorbance at 570-590 nm with reference wavelength of 630-650 nm.

Data Analysis:

- Subtract background absorbance from blank wells containing medium only.

- Generate standard curve with known bacterial concentrations.

- Calculate metabolic activity relative to controls.

Critical Considerations [2]

- Tetrazolium concentration must balance enzyme saturation with potential dye toxicity.

- Include formaldehyde-fixed controls (1.5-4% final concentration) to account for abiotic reduction.

- Optimize incubation time for specific bacterial species and growth conditions.

- Some bacterial strains may lack ability to reduce specific tetrazolium salts.

Resazurin Reduction Assays (AlamarBlue/PrestoBlue)

Principle Resazurin, a blue, non-fluorescent compound, is reduced to pink, highly fluorescent resorufin by metabolically active bacteria through both enzymatic and non-enzymatic processes involving the electron transport system [4]. The conversion rate is proportional to metabolic activity, allowing both endpoint and kinetic measurements.

Protocol [4]

Reagent Preparation:

- Use commercially available alamarBlue or PrestoBlue reagents.

- Equilibrate to room temperature before use.

Assay Procedure:

- Dispense 100 μL of bacterial suspension into microplate wells.

- Add 10% volume of alamarBlue reagent (10 μL per 100 μL sample).

- For PrestoBlue, add 10% volume and incubate for 10 minutes to 4 hours.

- Incubate at 37°C protected from light for 1-4 hours (alamarBlue) or 10 minutes (PrestoBlue HS).

- Measure fluorescence (Excitation 530-570 nm/Emission 580-620 nm) or absorbance (570 nm).

Data Interpretation:

- Increased fluorescence or color change from blue to pink indicates metabolic activity.

- Include positive (viable bacteria) and negative (sterile medium) controls.

- Generate standard curves for quantitative assessment.

Advantages and Limitations

- Advantages: Non-toxic, allows continuous monitoring, applicable to aerobic and anaerobic bacteria.

- Limitations: Potential interference with reducing agents, signal stability affected by pH and oxygen.

Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) Hydrolysis Assay

Principle Non-fluorescent FDA passively diffuses across bacterial membranes and is hydrolyzed by non-specific intracellular esterases to release fluorescent fluorescein, which accumulates in cells with intact membranes [1].

Protocol [1]

Reagent Preparation:

- Prepare FDA stock solution (1-10 mg/mL) in acetone or DMSO.

- Dilute in appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS) to working concentration (10-100 μg/mL).

Assay Procedure:

- Mix 100 μL bacterial suspension with equal volume FDA working solution.

- Incubate at 37°C for 15-60 minutes protected from light.

- Measure fluorescence (Excitation 485 nm/Emission 535 nm).

- Stop reaction with alkaline stop solution (e.g., 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate).

Data Analysis:

- Compare fluorescence to standard curve of known bacterial concentrations.

- Express results as relative fluorescence units or percentage of control.

Critical Considerations [1]

- pH sensitivity: acidic conditions promote fluorescein efflux, reducing signal.

- Potential quenching at high intracellular fluorescein concentrations.

- Enzyme activity varies with optimal pH for different bacterial species.

Oxygen Consumption Monitoring with RTDP

Principle Aerobic bacterial metabolism consumes dissolved oxygen, which quenches the fluorescence of oxygen-sensitive fluorophores like ruthenium tris (2,2'-diprydl) dichloride hexahydrate (RTDP) [3]. As oxygen decreases during bacterial growth, fluorescence increases proportionally.

Nanowell Monitoring Protocol [3]

Device Preparation:

- Fabricate nanowell arrays (typically 10-100 nL volume) using soft lithography.

- Treat surfaces to create hydrophilic wells with hydrophobic top surfaces.

Sample Preparation:

- Mix bacterial sample with selective growth medium and RTDP (final concentration 1-10 μM).

- Dispense mixture onto nanowell device.

- Spread sample with glass slide "squeegee" to compartmentalize into nanowells.

- Seal device with glass slide to prevent evaporation.

Monitoring and Analysis:

- Image wells using fluorescent microscope or microarray scanner.

- Monitor fluorescence intensity over time (typically 30-90 minutes).

- Calculate oxygen consumption rates from fluorescence changes.

- Determine detection time based on signal deviation from negative controls.

Advantages [3]

- Rapid detection (35-60 minutes for E. coli at 10⁴-10⁸ cells/mL)

- Minimal sample preparation required

- Compatible with drug effectiveness testing

- Suitable for resource-poor settings

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Metabolic Activity Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Mechanism | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrazolium Salts | MTT, XTT, INT, CTC | Reduced to formazan by active ETS; colorimetric detection | Bacterial viability, drug susceptibility testing |

| Resazurin-Based Dyes | alamarBlue, PrestoBlue | Reduced to fluorescent resorufin; fluorescent/colorimetric detection | High-throughput screening, continuous monitoring |

| Fluorogenic Substrates | Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA), 2-NBDG | Hydrolyzed by intracellular enzymes; fluorescence activation | Enzyme activity, substrate uptake studies |

| Oxygen-Sensitive Probes | Ruthenium complexes (RTDP) | Fluorescence quenching by oxygen; inverse correlation with metabolism | Respiratory activity, real-time monitoring |

| Viability Stains | Propidium iodide, SYTO 9 | Membrane integrity assessment; differential staining | Live/dead discrimination, flow cytometry |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | LDH Cytotoxicity Assay | Measure extracellular enzyme release; colorimetric/fluorometric | Cytotoxicity, membrane damage assessment |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis Methods

Standard Curve Generation

- Prepare serial dilutions of bacterial cultures with known concentrations (CFU/mL)

- Perform metabolic assay in parallel

- Plot signal intensity (absorbance, fluorescence) versus bacterial concentration

- Use linear regression to establish quantitative relationship

Metabolic Rate Calculations

- Determine time-dependent signal change (ΔSignal/ΔTime)

- Normalize to bacterial number or biomass

- Express as metabolic rate per cell or per unit biomass

Threshold Determination

- Establish statistically significant signal thresholds above negative controls

- Calculate limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ)

- Validate against reference methods (e.g., plate counts)

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Metabolic Activity Assays

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal Intensity | Low metabolic activity, incorrect dye concentration, suboptimal pH | Optimize dye concentration, check bacterial growth phase, verify pH conditions |

| High Background | Non-specific reduction, abiotic interference, contaminations | Include proper controls (fixed cells, medium alone), filter sterilize reagents |

| Inconsistent Results | Bacterial clumping, uneven dye distribution, temperature fluctuations | Standardize inoculation procedures, vortex samples, use temperature-controlled instrumentation |

| Poor Correlation with Culturability | VBNC populations, different physiological states, assay limitations | Combine multiple viability assays, optimize incubation conditions |

Applications in Research and Development

Drug Discovery and Development

Metabolic activity assays provide crucial information throughout the drug development pipeline:

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- Rapid determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC)

- Assessment of bactericidal versus bacteriostatic activity

- Evaluation of time-kill kinetics

Mechanism of Action Studies

- Identification of metabolic pathway inhibition

- Detection of bacterial persistence

- Evaluation of drug combinations

Environmental and Food Safety Monitoring

Rapid Pathogen Detection

- Screening of food and water samples for microbial contamination

- Assessment of disinfection efficacy

- Monitoring of microbial loads in manufacturing environments

VBNC Detection in Treated Samples

- Identification of viable pathogens after antibiotic treatment

- Evaluation of sterilization process effectiveness

- Assessment of microbial risk in processed products

Basic Research Applications

Physiological Studies

- Characterization of bacterial stress responses

- Investigation of metabolic adaptation mechanisms

- Study of population heterogeneity

Method Validation

- Comparison of novel detection methods with metabolic activity standards

- Evaluation of culture media formulations

- Optimization of growth conditions

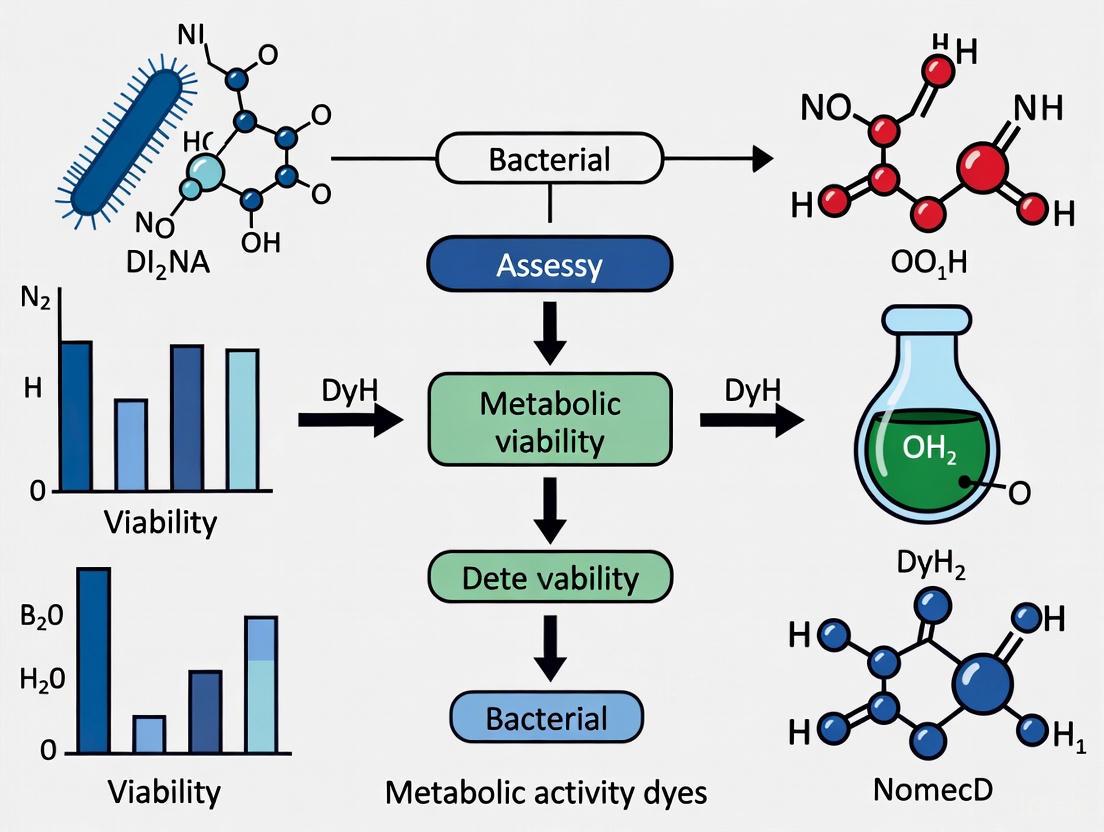

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for metabolic activity assessment, highlighting key procedural steps and the specific metabolic pathways targeted by different assay reagents.

Metabolic activity assays provide powerful, rapid alternatives to traditional culturability methods for comprehensive bacterial viability assessment. By targeting fundamental biochemical processes including electron transport, enzyme activity, and respiratory function, these approaches successfully detect viable but nonculturable bacteria that would otherwise escape identification. The protocols detailed in this Application Note—including tetrazolium reduction, resazurin conversion, FDA hydrolysis, and oxygen consumption monitoring—offer researchers robust methodologies adaptable to diverse experimental needs from basic research to drug discovery and environmental monitoring. When properly validated and interpreted in context with other viability parameters, metabolic activity assessment serves as an essential component of a multifaceted approach to determining true bacterial viability beyond the limitations of culturability alone.

Tetrazolium salts are water-soluble, colorless compounds that serve as vital indicators of cellular metabolic activity. Their reduction to intensely colored, insoluble formazan products is a cornerstone of viability testing in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. This redox reaction is primarily driven by reducing equivalents generated through cellular metabolic processes, such as those in the mitochondrial electron transport chain or from plasma membrane-associated enzymatic systems. In the context of bacterial viability assessment, the capacity of bacterial cells to reduce tetrazolium salts like 2,3,5-triphenyl-2H-tetrazolium chloride (TTC) provides a quantifiable measure of cell redox potential and metabolic health. The irreversible formation of formazan can be precisely quantified using spectrophotometry, offering researchers a reliable, colorimetric method for assessing bacterial population viability, drug susceptibility, and substrate utilization.

Fundamental Redox Chemistry and Reduction Pathways

The core principle of tetrazolium salt reduction involves a clearcut redox reaction where the tetrazolium cation (a colorless electron acceptor) gains electrons from cellular reducing systems and is converted into a formazan (a colored electron donor). This transformation involves the breaking of the tetrazolium ring and the formation of a formazan dye characterized by a chromophore that absorbs light at specific wavelengths.

The reduction potential of tetrazolium salts makes them favorable electron acceptors in biological systems. The net positive charge on many tetrazolium salts facilitates their cellular uptake due to the membrane potential, allowing for intracellular reduction. Research indicates that reduction can occur via multiple pathways:

- Intracellular Reduction: Lipophilic salts like MTT can penetrate the cytoplasmic membrane and are primarily reduced by mitochondrial dehydrogenases in the electron transport chain [6] [7].

- Plasma Membrane-Associated Reduction: Evidence suggests that a significant portion of reduction occurs via enzymatic systems or species located at the outer surface of plasma membranes. Studies with CTC on HepG2 cells indicate reduction can happen "in or at the outer surface of plasma membranes" [6].

- Electron Carrier-Dependent Reduction: Some tetrazolium salts, particularly hydrophilic variants like WST-8 and WST-1, require an intermediate electron acceptor to transduce the electron transfer essential for tetrazolium reduction. The presence of an electron carrier can significantly enhance the reduction rate [6] [7].

The following diagram illustrates the primary cellular reduction pathways for tetrazolium salts:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and materials used in tetrazolium-based viability assays, with a focus on the TTC assay for bacterial cells:

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Tetrazolium Salt Viability Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function in Assay | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| 2,3,5-Triphenyl-2H-tetrazolium chloride (TTC) | Water-soluble, colorless substrate that is reduced to formazan by cellular reducing equivalents. [8] | Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: T8877; 24 mM working concentration in sodium phosphate buffer. |

| 1,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium Formazan | Provides the colored reduction product used for preparing standard curves for quantification. [8] | Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: 93145. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Organic solvent used to dissolve the insoluble formazan product for spectrophotometric measurement. [8] | Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number: D5879; 99.5% purity. |

| Sodium Phosphate Buffer | Provides a stable physiological pH environment (pH 7.5) for the redox reaction during incubation. [8] | 50 mM concentration, pH 7.5. |

| TYR Broth Medium | Culture medium for growing bacterial inoculum, containing tryptone and yeast extract. [8] | 5 g/L tryptone, 3 g/L yeast extract, 6 mM CaCl₂. |

| MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) | A lipophilic tetrazolium salt that readily penetrates cell membranes and is reduced intracellularly. [9] [7] | Common in eukaryotic cell viability assays; reduced by mitochondrial dehydrogenases. |

| WST-8 (Sodium 4-[2-(2-methoxy-4-nitrophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)tetrazol-2-ium-5-yl]benzene-1,3-disulfonate) | A hydrophilic, membrane-impermeant tetrazolium salt used in assays for eukaryotic cells. Reduction occurs extracellularly, often requiring electron acceptors. [7] | Used in commercial cell counting kits; water-soluble formazan product. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: TTC Assay for Bacterial Cell Redox Potential

This protocol is adapted from a established method for evaluating the cell redox potential of Sinorhizobium meliloti and can be generalized for other bacterial cells with appropriate modifications. [8]

The complete experimental process for the TTC assay is summarized in the following workflow:

B. Step-by-Step Procedure

Growth of Bacterial Cells

- Inoculate pure bacterial culture (e.g., S. meliloti 1021) into 2.0 ml of TYR medium (or other appropriate medium) and incubate for 24 hours at 30°C on a rotary shaker (200 rpm). [8]

- Transfer aliquots (0.15 ml) of the culture into fresh medium (e.g., 15 ml) to standardize the optical density (OD₆₀₀ = 0.2). [8]

- Incubate until the cultures reach the exponential growth phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.7), which typically takes about 4 hours. [8]

Cell Harvesting and Preparation

- Split the culture: use 10 ml for biomass evaluation and 1.5 ml for the TTC reduction measurement. [8]

- For biomass evaluation: Centrifuge the 10 ml culture at 5,000 × g for 20 min at room temperature. Discard the supernatant, dry the pellet at 65°C for 4 hours, and weigh the resulting cell mass. [8]

- For the TTC assay: Centrifuge the 1.5 ml culture in a microcentrifuge tube at 8,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature. Discard the supernatant. [8]

- Wash the bacterial pellet with 1 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), centrifuge again (8,000 × g, 5 min), and discard the supernatant. [8]

TTC Incubation and Formazan Solubilization

- Thoroughly resuspend the cell pellet in 1 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 24 mM TTC. [8]

- Incubate the suspension at 30°C for 1 hour on a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. [8]

- After incubation, collect the cells by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 5 min and discard the supernatant. [8]

- Resuspend the cells in 1 ml of 99.5% DMSO (at room temperature) to completely dissolve the formed, insoluble formazan crystals. [8]

- Centrifuge the suspension at 13,000 × g for 1 minute to pellet cellular debris. Collect the colored supernatant for analysis. [8]

Spectrophotometric Quantification and Data Normalization

- Prepare a set of formazan standard solutions at known concentrations in DMSO (e.g., from 0.0075 mg/ml to 0.3 mg/ml). [8]

- Measure the absorbance of the standards and experimental samples at 510 nm using a spectrophotometer. Use 99.5% DMSO as a blank control. [8]

- Plot a calibration curve of the formazan standards (mg/ml) against their absorbance at 510 nm. [8]

- Determine the amount of formazan produced in the experimental samples by interpolating from this standard curve. [8]

- Normalize the formazan quantity to the cell biomass (g) corresponding to the 1.5 ml of bacterial culture used in the assay. The final result is expressed as mg formazan per g of cells. [8]

C. Anticipated Results and Data Presentation

The TTC assay typically yields quantitative data demonstrating a higher reduction rate in metabolically active cells. The table below provides an example of expected results.

Table 2: Example Quantitative Data from TTC Reduction Assay [8]

| Sample Type | OD 510 nm | Formazan (mg/ml) | mg Formazan / mg cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential Phase Cells - Replicate 1 | 0.19 | 0.046 | 0.057 |

| Exponential Phase Cells - Replicate 2 | 0.22 | 0.054 | 0.056 |

| Exponential Phase Cells - Replicate 3 | 0.22 | 0.061 | 0.067 |

| Stationary Phase Cells - Replicate 1 | 0.14 | 0.034 | 0.029 |

| Stationary Phase Cells - Replicate 2 | 0.14 | 0.033 | 0.029 |

| Stationary Phase Cells - Replicate 3 | 0.13 | 0.032 | 0.026 |

This data illustrates a core finding: cells from exponential-phase cultures possess an increased cell redox potential compared to those from stationary-phase cultures, generating a higher amount of reducing equivalents for TTC reduction. [8]

Critical Considerations for Robust Assay Performance

Assay Interferences: Be aware that certain materials can interfere with tetrazolium salt assays. For instance, bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) has been shown to cause significant interference with hydrophilic tetrazolium salts like WST-8, potentially leading to false negatives in viability measurements. [7] Lipophilic salts like MTT may not show such interference, highlighting the importance of assay selection based on the experimental system. [7]

Optimization and Controls: The MTT colorimetric assay, while rapid and convenient, can be influenced by various parameters that affect cellular metabolism and modify MTT-specific activity, potentially leading to inaccurate cell counts. [9] It is essential to optimize conditions such as cell density, nutrient availability in the culture medium, and concentrations and exposure times for the tetrazolium salt. [9] Always include proper controls to minimize confounding effects.

Metabolic Dependence: A fundamental limitation of enzymatic methods like tetrazolium reduction is their dependence on cell metabolism. The signal generated is not directly proportional to cell number under all conditions, as higher cell densities can provide a lower signal per cell than lower densities due to metabolic changes. [10] This can be contrasted with DNA quantification methods, which are independent of metabolic state. [10]

Within the field of bacterial viability assessment, the measurement of metabolic activity serves as a cornerstone for research in microbiology, drug discovery, and toxicology. Metabolic dyes are powerful tools that provide a window into cellular health by acting as indicators of key biochemical processes. These assays are predominantly based on the principle of using oxidoreductase enzymes and their associated cofactors (e.g., NADH, NADPH) as markers for metabolic activity [11]. In living cells, these molecules act as electron sources, enabling the biochemical reduction of specific, non-fluorescent or chromogenic dyes. This reduction reaction results in a measurable change, either a color shift (absorbance) or the emergence of fluorescence, which can be quantified using standard laboratory equipment [11]. This application note details the mechanisms, applications, and detailed protocols for five key metabolic dyes—MTT, XTT, FDA, FUN-1, and resazurin—framed within the critical context of bacterial viability research.

Dye Mechanisms and Properties

Metabolic dyes report on viability through different biochemical pathways. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each dye.

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Metabolic Dyes for Bacterial Viability Assessment

| Dye Name | Chemical Principle | Detection Method | Key Application in Bacteria | Signal Proportional to |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resazurin | Reduction to fluorescent resorufin [12] | Fluorescence (Ex/Em ~530-560/590 nm) or Absorbance (570 nm) [12] | Homogeneous, high-throughput viability screening; long-term kinetic monitoring [12] | Metabolic activity of viable cells [12] |

| MTT | Reduction to insoluble purple formazan crystals [5] | Absorbance (570 nm, with 630 nm reference) [5] | Endpoint measurement of dehydrogenase activity [5] | Metabolic activity (mitochondrial dehydrogenases in eukaryotes; general reductases in bacteria) [5] |

| XTT | Reduction to a water-soluble formazan product [5] | Absorbance (450 nm) | Reduction capacity of viable cells; ideal for high-throughput assays | Metabolic activity |

| FDA | Hydrolysis by esterases to fluorescent fluorescein | Fluorescence (Ex/Em ~490/520 nm) | Membrane integrity and enzymatic activity | Esterase activity and cell membrane integrity |

| FUN-1 | Conversion to orange-red cylindrical intravacuolar structures (CIVS) by metabolically active yeast/fungi [10] | Fluorescence microscopy (Ex/Em ~470/590 nm for CIVS) | Viability and metabolic activity assessment in yeast/fungi | Metabolic activity and vacuolar function |

The following diagram illustrates the general metabolic pathway and the specific conversion points for the different dyes.

Diagram 1: General metabolic reduction pathway for viability dyes.

Quantitative Data Comparison

Selecting the appropriate dye requires a clear understanding of performance metrics. The following table provides a comparative summary of sensitivity, linear range, and key considerations for each dye.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Practical Considerations of Metabolic Dyes

| Dye Name | Reported Sensitivity | Linear Range (Typical) | Assay Time (Typical) | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resazurin | As few as 80 cells (mammalian) [12] | 1-24 hours incubation [12] | 1-4 hours | Signal can decrease at high cell density due to over-reduction to non-fluorescent product [12]; non-toxic, allows kinetic monitoring [12] |

| MTT | Varies with cell type | 3-4 hours | 3-4 hours | Requires solubilization step; background can be caused by serum or phenol red [5] |

| XTT | Varies with cell type | 1-4 hours | 1-4 hours | Often requires an electron-coupling reagent; ready-to-use kits available |

| FDA | Varies with cell type | 10-60 minutes | 10-60 minutes | Signal depends on both esterase activity and membrane integrity; can be used for microscopy |

| FUN-1 | Varies with cell type | 30 minutes - 3 hours | 30 minutes - 3 hours | Specific for fungi/yeast; requires fluorescence microscopy for CIVS visualization |

Experimental Protocols

Resazurin Cell Viability Assay Protocol

The resazurin assay is a sensitive, homogeneous, and non-toxic method ideal for high-throughput screening and long-term kinetic monitoring of bacterial viability [12].

Key Materials:

- Resazurin solution: Ready-to-use, aqueous solution (e.g., Biotium Resazurin Cell Viability Assay Kit) [12].

- Cell cultures: Bacterial cultures in a suitable growth medium.

- Microplate reader: Capable of measuring fluorescence (Ex/Em 530-560/590 nm) or absorbance (570 nm).

Procedure:

- Preparation: Plate bacteria in a 96-well microplate at an optimal density in culture medium. Include a negative control well (medium only, no cells) for background subtraction. Incubate the plate under appropriate conditions until ready to assay.

- Dye Addition: Add a small volume of the ready-to-use resazurin solution directly to each well. The typical final concentration is 10% of the total well volume.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate under optimal growth conditions for 1-4 hours. The incubation time may require optimization for specific bacterial strains.

- Signal Measurement: After incubation, measure the signal.

- Data Analysis:

- Average the replicate readings for each sample.

- Subtract the average value of the negative control (background) from all test samples.

- The corrected fluorescence or absorbance value is proportional to the number of metabolically active cells.

MTT Assay Protocol for Bacterial Cells

The MTT assay measures the reduction of a yellow tetrazolium salt to purple formazan crystals by metabolic activity [5].

Key Materials:

- MTT solution: 5 mg/mL MTT in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Filter sterilize and store at -20°C [5].

- MTT solvent: 4 mM HCl, 0.1% NP-40 in isopropanol [5].

- Serum-free culture medium.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Plate bacteria in a 96-well plate as described in the resazurin protocol.

- Dye Addition: Carefully remove the culture media from each well. Add 50 µL of serum-free media and 50 µL of MTT solution into each well [5].

- Incubation: Incubate the plate at 37°C for 3 hours.

- Solubilization: After incubation, add 150 µL of MTT solvent into each well to dissolve the formed formazan crystals. Wrap the plate in foil and shake on an orbital shaker for 15 minutes to ensure complete dissolution [5].

- Signal Measurement: Read the absorbance at 590 nm. It is recommended to read the plate within 1 hour after adding the solvent [5].

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the average absorbance for each sample and subtract the background (media-only control).

- The corrected absorbance is proportional to the metabolic activity of the bacterial population.

The workflow for a typical endpoint viability assay, such as the MTT assay, is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Endpoint viability assay workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of metabolic dye assays relies on a set of core reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Metabolic Dye Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Resazurin Assay Kit | Ready-to-use solution for homogeneous viability testing [12] | Biotium Resazurin Cell Viability Assay Kit [12] |

| MTT Reagent | Tetrazolium salt for endpoint dehydrogenase activity measurement [5] | Prepare as 5 mg/mL solution in PBS; filter sterilize [5] |

| MTT Solubilization Solution | Dissolves water-insoluble formazan crystals for absorbance reading [5] | 4 mM HCl, 0.1% NP-40 in isopropanol [5] |

| Microplate Reader | Instrument for quantifying absorbance or fluorescence signals | Must have appropriate filters for fluorescence dyes (e.g., ~590 nm for resorufin) [12] |

| Cell Culture Plates | Vessel for growing cells and performing assays | 96-well plates are standard for high-throughput screening |

| Serum-Free Medium | Used during dye incubation to prevent background interference | Serum and phenol red can generate background signal [5] |

The strategic selection of metabolic dyes is fundamental to robust bacterial viability assessment. Resazurin offers exceptional flexibility for non-toxic, kinetic, and high-throughput studies. In contrast, MTT and XTT provide reliable endpoint measurements, with XTT offering a simplified workflow due to its water-soluble product. FDA is ideal for rapid enzymatic and membrane integrity checks, while FUN-1 provides unique insights into the metabolic state of yeast and fungi. Understanding the distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations of each dye, as detailed in this application note, empowers researchers to design more accurate, efficient, and informative experiments in drug development and microbial research.

Assessing bacterial viability is a cornerstone of microbiological research, impacting fields from drug development to environmental bioremediation. While traditional methods often rely on membrane integrity, there is a growing recognition that metabolic activity provides a more functional and often more sensitive measure of bacterial viability. Within this paradigm, the reduction of certain dyes linked to the electron transport system (ETS) serves as a powerful, direct indicator of cellular metabolic state. This application note details the critical biochemical connection between bacterial NADH, the ETS, and the reduction of viability probes, providing researchers with established and emerging methodologies to apply these principles in their investigative work.

The fundamental connection lies in the central role of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) in cellular catabolism. As bacteria break down carbon sources, they generate NADH, which carries high-energy electrons. These electrons are primarily fed into the ETS to generate the proton motive force necessary for ATP synthesis. The same reducing power can be harnessed by exogenous dyes that act as artificial electron acceptors. When a bacterial cell reduces a dye, it provides a direct, quantifiable signal of an active ETS and, by extension, cellular viability. The following diagram illustrates this core relationship and the experimental workflow for its application.

The Biochemical Foundation: NADH and the Electron Transport System

The electron transport system is a series of protein complexes embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotes or the plasma membrane of bacteria. Its primary function is to couple the transfer of electrons from donors like NADH to final acceptors like oxygen with the pumping of protons across the membrane, creating an electrochemical gradient [13] [14].

- The Role of NADH: NADH is a primary electron donor. It is generated during glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and other metabolic pathways. In the ETS, complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) accepts electrons from NADH, oxidizing it to NAD⁺. This electron transfer is coupled to the pumping of protons, contributing directly to the proton gradient [13].

- Linking ETS to Dye Reduction: The reduction of artificial dyes can occur through two primary mechanisms, both linked to the ETS. First, some dyes can be reduced directly by ETS components, effectively acting as alternative terminal electron acceptors instead of oxygen. Second, as evidenced in studies of azo dye degradation, the reduction is often catalyzed by flavin-dependent azoreductases that utilize NADH (or sometimes NADPH) as their primary electron donor [15] [16]. The constant regeneration of NAD⁺ from NADH via these reactions is critical for maintaining the flow of central metabolic pathways, directly linking dye reduction to the overall metabolic vigor of the cell.

Table 1: Key Components of the Bacterial Electron Transport System Relevant to Dye Reduction

| Component | Function in ETS | Role in Dye Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Complex I (NADH Dehydrogenase) | Oxidizes NADH to NAD⁺, transfers electrons to ubiquinone, pumps protons [13]. | Primary entry point for electrons from NADH; its activity directly influences the cellular NAD⁺/NADH ratio. |

| NADH/NAD⁺ Pool | The ratio represents the cellular redox state; a high NADH level indicates abundant reducing power [17]. | Serves as the immediate electron donor for many azoreductase enzymes that reduce dyes [15] [16]. |

| Ubiquinone (Coenzyme Q) | A mobile lipid-soluble carrier that shuttles electrons from Complex I and II to Complex III [13] [18]. | Can be involved in the reduction of lipid-soluble dyes within the membrane. |

| Azoreductase Enzymes | Not a standard ETS component, but a class of enzymes that often use NADH [15]. | Catalyzes the reductive cleavage of azo bonds (-N=N-) in dyes, using NADH as an electron source [15] [16]. |

Quantitative Data from Dye Reduction Studies

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research that demonstrates the link between bacterial metabolic activity, often facilitated by the ETS and NADH, and the degradation of various dyes.

Table 2: Quantitative Data on Bacterial Dye Reduction Linked to Metabolic Activity

| Dye / Probe | Bacterial System | Key Quantitative Finding | Implication for Viability Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sudan III & Orange II | Staphylococcus aureus | Metabolomics revealed Sudan III was metabolized to 4-(phenyldiazenyl) aniline (48% yield) and other products, indicating active intracellular reduction [15]. | Dye reduction is a specific metabolic activity that can be quantified to assess the metabolic state of viable cells. |

| Reactive Black 5 (RB5) | Bacterial Consortium DDMZ1 | Addition of fructose co-substrate increased decolorization efficiency from 77% (yeast extract only) to 98% within 48 hours [16]. | Availability of a preferred carbon source boosts central metabolism and NADH production, driving more rapid dye reduction. |

| Reactive Black 5 (RB5) | Bacterial Consortium DDMZ1 | ~90x more Orange II was detected in cell pellets from viable S. aureus vs. boiled cells, proving reduction is an active, primarily intracellular process [15]. | Confirms that dye reduction is a marker of viable, metabolically active cells with intact transport mechanisms, not passive adsorption. |

| LIVE/DEAD BacLight | General Bacteria | Cells with intact membranes (viable) fluoresce green (SYTO 9), while those with compromised membranes (dead) fluoresce red (Propidium Iodide) [19]. | While not an activity stain, this kit assesses membrane integrity, a prerequisite for maintaining the proton gradient and ETS function. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Metabolic Reduction of Azo Dyes by Staphylococcus aureus

This protocol is adapted from a metabolomics study investigating the reduction of azo dyes by S. aureus and its effect on the bacterial metabolome [15].

You will need:

- Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 (or other relevant strain)

- Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth

- Azo dye stock solution (e.g., Sudan III or Orange II, prepared in DMSO)

- Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, vehicle control)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or 0.85% NaCl wash buffer

- Centrifuge and fixed-angle rotor

- LC/MS system for metabolomic analysis (optional)

Procedure:

- Culture and Treatment:

- Inoculate S. aureus into BHI broth at a 1% (v/v) ratio and culture at 37°C.

- At the target growth phase, add the azo dye from the stock solution to the culture medium to a final concentration of 10 µg/mL. Include a vehicle control (DMSO alone) and a dead cell control (boiled culture incubated with dye).

- Incubate the cultures at 37°C for 18 hours without agitation.

Sample Harvesting:

- Determine bacterial count in the culture media using flow cytometry or plate counting.

- Harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Carefully remove the supernatant. The color of the supernatant can be an initial indicator of decolorization (dye reduction).

Metabolite Extraction (for LC/MS Analysis):

- Suspend the cell pellet in 200 µL of ice-cold water.

- Transfer 120 µL of the suspension to a new tube containing 450 µL of methanol and vortex vigorously.

- Incubate the lysate at 4°C for 15 minutes, then homogenize using a bead beater or similar homogenizer.

- Centrifuge the homogenate at 16,060 × g for 12 minutes at 4°C to precipitate proteins.

- Transfer the supernatant to a clean tube and evaporate to dryness using a SpeedVac concentrator.

- Reconstitute the dried metabolites in 200 µL of 95:5 water/acetonitrile for LC/MS analysis.

Data Analysis:

- Use LC/MS to identify and quantify dye metabolites (e.g., 4-aminobenzene sulfonic acid from Orange II) and changes in the endogenous bacterial metabolome.

- Compare the metabolite profiles of the treated samples to the vehicle and dead cell controls to distinguish specific metabolic effects from non-specific binding.

Protocol 2: Fluorescence Microscopy for Bacterial Viability Based on Membrane Integrity

This protocol utilizes the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit, which, while not a direct metabolic stain, is a widely used viability assay where membrane integrity is essential for maintaining the ETS [19].

You will need:

- LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit, for microscopy (L7012)

- Bacteria in late log-phase culture

- Nutrient broth

- 0.85% NaCl wash buffer (Note: Phosphate buffers may decrease staining efficiency)

- Fluorescence microscope with FITC and Texas Red filter sets

- Microcentrifuge, glass slides, and coverslips

Procedure:

- Culture and Preparation of Bacterial Suspensions:

- Grow a 25 mL bacterial culture to late log-phase in nutrient broth.

- Centrifuge the culture at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Remove the supernatant and resuspend the pellet in 2 mL of wash buffer.

- Perform a series of washes (dilute, incubate, centrifuge, resuspend) to ensure all growth medium is removed [19].

Staining Bacteria:

- Combine equal volumes of the SYTO 9 and propidium iodide stains from the kit in a microfuge tube.

- Add 3 µL of the mixed dye solution to each 1 mL of the bacterial suspension.

- Incubate the stained suspension at room temperature in the dark for 15 minutes.

Microscopy and Imaging:

- Pipette 5 µL of the stained bacterial suspension onto a clean glass slide and cover with a coverslip.

- Image the cells immediately using a fluorescence microscope.

- Use a standard FITC filter set (excitation/emission ~480/500 nm) to view live cells (green, SYTO 9 stain).

- Use a Texas Red filter set (excitation/emission ~490/635 nm) to view dead cells (red, propidium iodide stain) [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Dye-Based Metabolic Viability Assays

| Reagent / Kit | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|

| LIVE/DEAD BacLight Viability Kit | A two-color assay that distinguishes bacteria with intact vs. compromised cell membranes. It is a standard for quantifying bacterial viability in a population via fluorescence microscopy [19]. |

| Azo Dyes (e.g., Sudan III, Orange II) | Model compounds used to study the azoreductase activity of bacteria. Their reduction, often NADH-dependent, serves as a direct marker of metabolic activity and is studied in biodegradation and toxicity research [15]. |

| Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NADH) | The essential electron donor cofactor. It is used in in vitro enzyme assays to confirm the NADH-dependence of azoreductases and other dye-reducing enzymes [15] [16]. |

| Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) Broth | A nutrient-rich growth medium used to culture demanding bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus for metabolic studies and dye reduction experiments [15]. |

| Co-substrates (e.g., Fructose) | Simple sugars added to microbial systems to enhance central metabolic pathways, increase NADH production, and thereby boost the biodegradation of dyes via co-metabolism [16]. |

The reduction of specific dyes by bacteria is not a passive chemical event but an active biological process intrinsically tied to core metabolism. As detailed in this application note, the critical link flows from carbon source catabolism through the generation of NADH, and ultimately to the electron transport system, which can shunt its reducing power to reduce artificial dyes. This pathway provides researchers with a robust, measurable indicator of true metabolic viability. By applying the protocols and understanding the reagents outlined herein, scientists and drug development professionals can leverage this connection to advance their research in antimicrobial testing, probiotic development, environmental microbiology, and beyond.

The Viable but Non-Culturable (VBNC) state is a dormant condition in which bacterial cells are alive and metabolically active but cannot form colonies on standard laboratory media that would normally support their growth [20] [21]. This state represents a fundamental survival strategy employed by a wide range of bacteria when faced with environmental stressors, allowing them to persist in conditions that would otherwise be lethal [22]. The VBNC phenomenon was first described in 1982 and formally termed in 1984, with research continuously evolving to understand its mechanisms and implications [20].

For researchers in bacterial viability assessment and drug development, the VBNC state presents a significant challenge. Conventional culture-based methods, long considered the gold standard in microbiology, fail to detect these dormant cells, leading to false negatives in viability assessments and potentially compromising public health safety, therapeutic efficacy, and diagnostic accuracy [21] [23]. This application note examines the critical limitations posed by the VBNC state in bacterial viability assessment and details advanced methodological approaches to overcome these challenges in research and development settings.

Characteristics and Triggers of the VBNC State

Defining Features of VBNC Cells

Bacteria in the VBNC state undergo significant physiological transformations while maintaining viability. Key characteristics include:

- Low metabolic activity with minimal growth and division [20] [23]

- Maintained membrane integrity and cellular structure [20]

- Reduced cell size (dwarfing) and potential changes in cell shape [23]

- Continued gene expression and protein synthesis, albeit at reduced levels [24] [22]

- Retention of plasmids and virulence potential [24] [22]

- Modified cell envelope including increased peptidoglycan cross-linking and changes in outer membrane protein profiles [20]

Unlike dead cells, VBNC cells maintain their membrane potential and ATP levels, allowing for potential resuscitation when environmental conditions become favorable [22].

Environmental Triggers for VBNC Induction

Multiple stressors can induce the VBNC state, many of which are relevant to food processing, clinical treatment, and environmental conditions:

Table 1: Common Inducers of the VBNC State and Their Research Implications

| Inducer Category | Specific Examples | Research Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Stressors | Temperature extremes (high/low), UV radiation, white light exposure, high pressure, pasteurization | Common in food processing; may induce VBNC in potential contaminants [22] [25] |

| Nutrient Stress | Nutrient starvation, oligotrophic conditions | Relevant to bacterial persistence in water systems and medical devices [20] [22] |

| Chemical Stressors | Antibiotics, heavy metals, food preservatives, chlorination, osmotic stress | Antibiotic exposure particularly relevant for understanding treatment failures [20] [21] |

| Biological Stress | Host immune defenses, competition with other microorganisms | Important in chronic infections and pathogen persistence [21] |

Detection Challenges and Methodological Limitations

The Inadequacy of Conventional Culture Methods

Standard microbiological culture techniques are fundamentally unable to detect VBNC bacteria, creating significant limitations for research and diagnostic applications:

- False Negative Results: VBNC cells do not form colonies on culture media, leading to underestimation of viable bacterial populations [1] [21]

- Misleading Safety Assessments: Samples may be deemed free of pathogens despite containing viable, potentially infectious VBNC cells [21] [22]

- Incomplete Assessment of Antimicrobial Efficacy: Antimicrobial treatments may induce VBNC state rather than complete elimination, incorrectly suggesting successful eradication [20] [23]

The inability to detect VBNC cells using conventional methods poses particular risks in clinical diagnostics, food safety testing, and pharmaceutical quality control, where undetected viable pathogens can lead to infections, product recalls, or disease outbreaks [21] [25].

Distinguishing VBNC from Related Physiological States

The VBNC state is distinct from, though sometimes confused with, other non-growing bacterial states:

- Persister Cells: Both are dormant subpopulations, but persisters are typically cultivated with specialized methods and are thought to represent a different stage in the dormancy continuum [20] [26]

- Sublethally Injured Cells: These cells have damaged cellular components but can recover more readily under appropriate conditions [26]

- Dead Cells: Unlike dead cells, VBNC cells maintain membrane integrity and metabolic potential [1]

Recent research by Ayrapetyan et al. suggests that persister cells and VBNC cells may represent points along a dormancy continuum, with persisters potentially transitioning more efficiently into the VBNC state when exposed to stress [20].

Advanced Detection Methodologies

Molecular Detection Approaches

Molecular techniques offer powerful alternatives to culture-based methods for VBNC detection:

Table 2: Molecular Methods for VBNC Detection in Research Applications

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability PCR (vPCR) | Uses DNA-intercalating dyes (PMA, EMA) to penetrate compromised membranes of dead cells; blocks PCR amplification | Differentiates viable vs. dead cells; relatively high throughput | May not detect VBNC with very low metabolism; dye penetration must be optimized [27] [26] |

| Reverse Transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) | Detects messenger RNA (mRNA) with short half-life indicative of active metabolism | Strong indicator of metabolic activity; highly specific | RNA instability requires careful sample handling; may not detect deeply dormant cells [22] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Comprehensive detection of bacterial DNA without cultivation requirements | Detects unculturable organisms; identifies diverse communities | Higher cost; complex data analysis; may not differentiate viability state without complementary methods [23] |

Cellular Viability and Metabolic Assays

Methods targeting cellular activity provide direct evidence of viability beyond culturability:

- Flow Cytometry with Viability Staining: Techniques using fluorescent dyes such as the BacLight Live/Dead assay (SYTO 9 and propidium iodide) can differentiate cells with intact membranes (live/VBNC) from those with compromised membranes (dead) [1] [22]

- Metabolic Activity Probes: Dyes such as fluorescein diacetate (FDA) and 5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride (CTC) are converted by enzymatic activity to fluorescent products, indicating metabolic function [1] [22]

- ATP Bioluminescence: Measures ATP production as an indicator of metabolic activity; however, ATP levels may be extremely low in dormant VBNC cells [21]

- Resazurin-Based Assays: Methods like RAPiD (Resazurin-Amplified Picoarray Detection) use resazurin reduction to fluorescent resorufin to detect metabolically active microcolonies in microfluidic devices [28]

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents for VBNC Studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for VBNC Detection

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Membrane Integrity Dyes | Propidium Iodide (PI), EMA, PMA, SYTO 9, BacLight Live/Dead kit | Differentiate cells with intact vs. compromised membranes; viability assessment by flow cytometry or microscopy [1] [22] |

| Metabolic Activity Probes | CTC, INT, fluorescein diacetate (FDA), 2-NBDG, AlamarBlue, resazurin | Detect enzymatic activity or substrate uptake as indicators of metabolic function [1] [28] |

| Nucleic Acid Detection | PCR primers, reverse transcriptase, viability dyes (PMAxx), RNA extraction kits | Molecular detection and viability determination through DNA/RNA analysis [27] [22] |

| Enzymatic Assays | Glucose oxidase-peroxidase system, lactate dehydrogenase assays | Measure specific metabolic pathways or products; LldD lactate dehydrogenase implicated in VBNC regulation [1] [24] |

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive VBNC Detection Using Integrated Approach

Viability PCR with Propidium Monoazide (PMA) for VBNC Assessment

This protocol enables discrimination between viable (including VBNC) and dead bacterial cells by preventing PCR amplification from dead cells with compromised membranes.

Materials Required:

- PMA dye (Biotium, Inc.)

- DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents and target-specific primers

- Light source (LED or halogen lamp)

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 10 min) and resuspend in PBS to approximately 10⁶ CFU/mL.

- PMA Treatment: Add PMA to sample to a final concentration of 50 μM. Mix thoroughly and incubate in the dark for 10 minutes.

- Photoactivation: Place sample on ice and expose to high-intensity light source for 15 minutes with occasional mixing.

- DNA Extraction: Pellet cells (12,000 × g, 5 min) and extract DNA according to kit manufacturer's instructions.

- PCR Amplification: Perform PCR with species-specific primers using standard protocols.

- Analysis: Compare PCR results from PMA-treated samples with untreated controls. Significant reduction in amplification signal indicates presence of dead cells, while persistent signal suggests viable/VBNC cells.

Technical Notes:

- PMA concentration and light exposure may require optimization for different bacterial species

- Include controls: known viable cells, heat-killed cells, and no-template control

- Combine with quantitative PCR (qPCR) for enumeration capabilities

- For environmental samples, preliminary filtration may be necessary to concentrate cells

Resuscitation of VBNC cells provides definitive evidence of their viability and potential pathogenicity.

Approach 1: Temperature Upshift

- Induce VBNC state in Vibrio parahaemolyticus or similar organisms by incubation in microcosm water at 4°C for 4-5 weeks [24].

- Confirm non-culturability by plating on appropriate media.

- Resuscitate by temperature upshift to 25-37°C and monitor for culturability restoration over 2 weeks [24].

Approach 2: Nutrient Supplementation

- Supplement culture media with 10-20 mM lactate or pyruvate to enhance resuscitation potential [24].

- Use co-culture with other bacteria or eukaryotic cells to provide potential resuscitation factors.

- Apply spent culture media from growing cells to potentially provide resuscitation signals.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis in VBNC State

Research using proteomic approaches has identified key metabolic adaptations in VBNC cells. In Vibrio parahaemolyticus, lactate dehydrogenase (LldD) was significantly upregulated in VBNC subpopulations, and deletion of the lldD gene accelerated entry into the VBNC state [24]. This suggests that lactate metabolism may play a crucial role in regulating the VBNC state, potentially through energy maintenance or response to oxidative stress.

The following diagram illustrates the metabolic adaptations and detection pathways for VBNC cells:

VBNC Metabolic Pathways and Detection

Research Implications and Future Directions

The limitations posed by the VBNC state in bacterial viability assessment have significant implications across multiple research domains:

- Drug Development: Antimicrobial efficacy testing must account for VBNC induction rather than complete eradication, requiring modified assessment protocols [20] [23]

- Diagnostic Development: Clinical diagnostics must incorporate methods that detect VBNC pathogens to prevent false negatives in chronic infections [23]

- Food Safety: Testing protocols need to evolve beyond culture-based methods to detect VBNC foodborne pathogens [25] [26]

- Antibiotic Stewardship: Understanding VBNC formation may inform treatment strategies to prevent chronic and recurrent infections [23]

Future research directions should focus on developing standardized detection methods, elucidating genetic regulation of VBNC entry and exit, and identifying compounds that either prevent VBNC formation or selectively eradicate VBNC cells. The integration of advanced technologies including microfluidics, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence in analytical platforms shows particular promise for overcoming current limitations in VBNC detection and characterization [21] [28].

The VBNC state represents a significant challenge in bacterial viability assessment that cannot be addressed through conventional culture-based methodologies. Researchers must employ integrated approaches combining molecular, metabolic, and cellular techniques to accurately detect and characterize these dormant cells. As our understanding of the genetic and metabolic basis of the VBNC state improves, so too will our ability to develop targeted strategies to overcome the limitations it poses in clinical diagnostics, drug development, and public health protection. The methodologies and approaches detailed in this application note provide a foundation for robust VBNC detection in research settings, enabling more accurate assessment of bacterial viability and ultimately contributing to improved therapeutic outcomes and safety assurance.

A Practical Guide: Protocols and Applications for Metabolic Dyes in Modern Labs

Bacterial viability assessment is a cornerstone of public health microbiology, food safety, and drug development, providing critical data for infectious risk evaluation [1]. The definition of "viability" itself is complex and is primarily assessed through three established criteria: culturability, metabolic activity, and membrane integrity [1]. Each criterion has its strengths and limitations. While culturability on agar plates has been the gold standard for over a century, it fails to detect viable but nonculturable (VBNC) bacteria, a state induced by stressors like low temperatures, nutrient scarcity, or high antibiotic concentrations [1]. Metabolic activity assays can detect VBNC bacteria but may miss dormant cells with silenced metabolism. Membrane integrity assessments overcome this by directly probing cellular structure, but often require multiple steps and specialized equipment [1]. This guide provides a structured framework for selecting optimal dyes based on your specific bacterial species and research objectives, ensuring accurate and reliable viability data.

Dye Selection Strategy: Aligning Mechanism with Research Goals

Choosing the correct dye requires a clear understanding of what aspect of viability you need to measure. The following table summarizes the primary mechanisms of action and their appropriate applications.

Table 1: Strategic Selection of Viability Dyes Based on Mechanism and Research Goal

| Viability Criterion | Mechanism of Action | Primary Application | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Activity | Enzymatic conversion of non-fluorescent substrates into fluorescent products (e.g., by esterases, dehydrogenases) [1] [29] | Detection of metabolically active cells; identification of VBNC cells that maintain enzyme activity [1] | Can detect VBNC state; indicates functional activity | May miss dormant cells; signal depends on metabolic rate and can be pH-sensitive [1] [29] |

| Membrane Integrity | Differential penetration through intact vs. compromised cell membranes to bind intracellular components (e.g., DNA) [1] [30] | Clear distinction between live/dead populations; high selectivity for cells with broken membranes [30] | Unambiguous dead cell identification; works for dormant cells; often faster | May not detect viable cells with mildly compromised membranes; can be less effective on Gram-positive bacteria with traditional dyes [1] [30] |

Diagram 1: A strategic workflow for selecting dye classes based on primary research goals.

Comprehensive Dye Tables for Informed Selection

Metabolic Activity Dyes

Metabolic dyes assess cellular enzyme activity or respiration. They are crucial for identifying functional activity beyond mere structural integrity.

Table 2: Fluorescent Dyes for Assessing Bacterial Metabolic Activity

| Dye Name | Ex/Em (nm) | Mechanism | Example Bacterial Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | 490/517 [1] | Hydrolyzed by nonspecific esterases to fluorescent fluorescein [1] | General viability assessment in environmental and food samples | Passive uptake; signal sensitive to intracellular pH; fluorescein efflux can occur [1] |

| Calcein-AM | 494/517 [31] | Converted by intracellular esterases to green-fluorescent calcein [31] | Often used in LIVE/DEAD kits with DNA-binding dead cell stains [31] | Superior cell retention and less pH-sensitive than FDA [29] |

| 5-Cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride (CTC) | Red fluorescence [30] | Reduced by dehydrogenases to insoluble, fluorescent CTC-formazan [30] [29] | Measuring respiratory activity in activated sludge, water samples [29] | Can be toxic upon intracellular accumulation; staining efficiency can be low [29] |

| C12-Resazurin | 488/575 (Product) [31] | Reduced by metabolically active cells to fluorescent C12-Resorufin [31] | Discrimination of live, injured, and dead populations in flow cytometry [31] | Lipophilic form of resazurin; product is better retained in live cells [31] |

Membrane Integrity Dyes

These dyes are the most common choice for simple live/dead discrimination. They function based on the fundamental difference between intact and damaged cell membranes.

Table 3: Fluorescent Dyes for Assessing Bacterial Membrane Integrity

| Dye Name | Ex/Em (nm) | Mechanism | Bacterial Compatibility | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | 535/617 [31] | Enters cells with compromised membranes, binds DNA/RNA, emits red fluorescence [10] [31] | Gram-negative and Gram-positive (with permeabilization) | Standard dead cell stain; can bind RNA requiring RNase treatment; may underestimate viable adherent cells [10] |

| SYTO 9 | 480/500 [31] | Permeant green nucleic acid stain that labels all bacteria [31] | Gram-negative and Gram-positive | Used in combination with PI in LIVE/DEAD BacLight kits; PI reduces SYTO 9 fluorescence in dead cells [31] |

| SYTOX Green | 488/530 [31] | Impermeant green nucleic acid stain that labels dead cells with compromised membranes [31] | Gram-negative and Gram-positive | High DNA binding affinity; >500x fluorescence enhancement [31] |

| BactoView Dead Stains | Varies by color (e.g., 572/583, 653/671) [30] | DNA-binding dyes excluded from both Gram-positive and Gram-negative live cells [30] | Gram-negative and Gram-positive (optimized for both) | High dead-cell selectivity; minimal background in live cells; single 30-min step, no wash [30] |

Specialized Dyes for Bacterial Identification and Staining

Beyond viability, other dyes help characterize bacterial samples by identifying structural features or labeling entire populations.

Table 4: Specialized Dyes for Bacterial Identification and General Staining

| Dye Name | Ex/Em (nm) | Mechanism | Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGA CF Dye Conjugates | Varies by conjugate [30] | Binds to N-acetylglucosamine in peptidoglycan of Gram-positive cell walls [30] | One-step fluorescent Gram staining | Faster and simpler than traditional multi-step Gram stain; available in many colors [30] |

| BactoView Live Stains | e.g., 500/520 [30] | Cell-permeant, fluorogenic DNA-binding dyes | Staining all bacteria in a sample, regardless of viability or Gram status [30] | Labels live and dead, Gram-positive and Gram-negative cells; provides total bacterial count [30] |

| BactoSpore Stains | e.g., 488/536 [30] | Optimized for staining endospores and vegetative cells | Detection of bacterial endospores (e.g., in B. subtilis) [30] | Validated for microscopy and flow cytometry; specific for the challenge of endospore detection [30] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Two-Color Live/Dead Staining Based on Membrane Integrity

This protocol uses the well-established SYTO 9 and Propidium Iodide (PI) combination, as found in commercial LIVE/DEAD BacLight kits, for microscopy and flow cytometry [31].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- SYTO 9 nucleic acid stain: Cell-permeant green fluorescent stain that labels all bacteria.

- Propidium Iodide (PI): Cell-impermeant red fluorescent stain that labels only bacteria with compromised membranes.

- Filter-sterilized phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or appropriate buffer: To maintain osmotic balance and suspend cells.

- Ethanol (70%): For preparing a killed control population.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Harvest bacterial cells and wash twice in filter-sterilized buffer. Resuspend the pellet to a density of approximately 10⁶ to 10⁷ cells/mL. For a control, prepare a heat- or ethanol-killed sample of the same strain.

- Staining Solution Preparation: Prepare the staining solution by mixing SYTO 9 and PI in a predetermined optimal ratio (e.g., 1.5 µM SYTO 9 and 30 µM PI in buffer, or as per kit instructions). Protect from light.

- Staining Incubation: Combine 100 µL of the bacterial suspension with 100 µL of the staining solution in a microcentrifuge tube. Mix gently and incubate the mixture in the dark at room temperature for 15-30 minutes.

- Analysis:

- Fluorescence Microscopy: Place a 5-10 µL aliquot of the stained suspension on a microscope slide, apply a coverslip, and visualize immediately. Use FITC/GFP filter sets for SYTO 9 (green) and TRITC/DSRed filter sets for PI (red). Live bacteria will fluoresce green, and dead bacteria will fluoresce red.

- Flow Cytometry: After incubation, dilute the stained sample 1:10 in buffer and analyze on the flow cytometer. Use a 488 nm laser for excitation. Collect green fluorescence through a 530/30 nm bandpass filter (SYTO 9) and red fluorescence through a 610/20 nm bandpass filter (PI).

Diagram 2: Workflow for two-color live/dead staining using membrane integrity dyes.

Protocol B: Metabolic Activity Staining Using Esterase Activity

This protocol utilizes a fluorogenic esterase substrate, such as Calcein-AM, to identify viable cells based on their enzymatic activity [29] [31].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Calcein-AM stock solution: Typically 1 mM in anhydrous DMSO. Aliquot and store at -20°C, protected from light and moisture.

- Filter-sterilized phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or appropriate growth medium.

- Ethidium Homodimer-1 (EthD-1) stock solution (optional): For a counterstain to label dead cells. Often used in combination with Calcein-AM in commercial kits [31].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Harvest and wash bacterial cells as in Protocol A. Resuspend in buffer to a density of 10⁶ to 10⁷ cells/mL.

- Working Solution Preparation: Prepare a working solution of Calcein-AM in buffer at a final concentration of 0.1 - 1 µM from the stock solution. Use immediately. If performing a live/dead assay, include EthD-1 at a final concentration of 1 - 4 µM.

- Staining Incubation: Add an equal volume of the Calcein-AM working solution to the bacterial suspension. Mix gently and incubate in the dark at 37°C (or appropriate growth temperature) for 15-60 minutes.

- Analysis:

- Microscopy/Plate Reader: Analyze the cells without washing. Excite at ~494 nm and collect emission at ~517 nm for the green Calcein signal. If using EthD-1, excite at ~517 nm and collect emission at ~617 nm for the red dead cell signal.

- Flow Cytometry: Analyze directly or after a brief wash. Use a 488 nm laser and collect green fluorescence in the FITC/GFP channel.

The accurate assessment of bacterial viability hinges on selecting a dye whose mechanism of action is strategically aligned with the research question and the biological characteristics of the target bacterium. No single method is perfect; the choice between metabolic activity dyes and membrane integrity dyes represents a trade-off between detecting physiological function and identifying structural collapse. By leveraging the selection tables, decision workflows, and standardized protocols provided in this guide, researchers can make informed choices that enhance the reliability and interpretability of their data, ultimately driving progress in drug development, microbiology research, and public health safety.

Bacterial viability assessment is a cornerstone of public health microbiology, environmental monitoring, and drug discovery [1]. While traditional culture-based methods have been used for over a century, they fail to detect viable but non-culturable (VBNC) bacteria—dormant cells that remain metabolically active but cannot form colonies on standard media [1] [2]. Metabolic activity dyes address this limitation by serving as direct proxies for cellular physiological functions, providing a more comprehensive picture of bacterial viability [2] [32].

This protocol focuses on tetrazolium salts and fluorescein diacetate (FDA) as key indicators of bacterial metabolic activity. These assays are particularly valuable in drug development for high-throughput screening of antimicrobial agents and in environmental microbiology for detecting active bacteria in complex samples [2] [33]. The principle behind these methods is straightforward: metabolically active cells enzymatically reduce tetrazolium salts to colored formazan products or hydrolyze non-fluorescent FDA to fluorescent fluorescein, with signal intensity proportional to metabolic activity [1] [32].

Principle of Metabolic Activity Assays

Metabolic activity dyes function as biochemical reporters of cellular physiological status by targeting key enzymatic processes or membrane integrity. The fundamental principle involves the enzymatic conversion of a non-colored or non-fluorescent substrate into a detectable product exclusively by viable, metabolically active cells [1] [2].

Tetrazolium Salts: These compounds (XTT, MTT, CTC, etc.) are reduced by dehydrogenase enzymes associated with the bacterial electron transport system, generating colored formazan derivatives [32] [33]. The reduction process depends on NADH or NADPH generated through cellular metabolism, directly linking formazan production to metabolic activity [32].

Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA): This non-polar, non-fluorescent compound readily crosses intact bacterial membranes. Inside viable cells, non-specific intracellular esterases hydrolyze FDA to release fluorescein—a polar, green-fluorescent molecule that accumulates in cells with intact membranes [1].

The table below summarizes the characteristics of common metabolic activity dyes:

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Metabolic Activity Dyes for Bacterial Viability Assessment

| Dye Name | Class | Mechanism of Action | Detection Method | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XTT | Tetrazolium salt | Reduced to water-soluble orange formazan by dehydrogenase enzymes [33] | Colorimetry (Abs ~470 nm) [33] | High-throughput screening, bacterial activity on polymers [33] |

| MTT | Tetrazolium salt | Reduced to insoluble violet formazan crystals [33] | Colorimetry (after solubilization) [34] | Cytotoxicity testing, basic viability assessment [34] |

| CTC | Tetrazolium salt | Reduced to fluorescent, insoluble formazan [32] | Fluorescence microscopy | Detection of respiring bacteria in environmental samples [32] |

| FDA | Fluorogenic substrate | Hydrolyzed to green-fluorescent fluorescein by intracellular esterases [1] | Fluorometry, microscopy | Broad-spectrum metabolic activity assessment [1] [2] |

| 2-NBDG | Fluorescent glucose analog | Transported via glucose uptake systems and metabolized [1] | Fluorometry | Assessment of glucose metabolism in susceptible bacteria [1] |

Materials and Equipment

Reagent Setup

- Carbon Source: Prepare appropriate carbon sources depending on experimental goals. For polyurethane degradation studies, use water-based polyester polyurethane (e.g., ImpranilDLN) at 1 mg·mL⁻¹ [33]. For general metabolic studies, use sodium citrate (20 mM) or other relevant carbon sources [33].

- XTT Solution: Prepare fresh XTT (2,3-bis [2-methyloxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide) solution at 2 mg·mL⁻¹ in sterile basal mineral medium or phosphate-buffered saline [33]. Filter sterilize using a 0.22 μm filter and protect from light.

- FDA Stock Solution: Prepare fluorescein diacetate at 1 mg·mL⁻¹ in acetone or DMSO. Aliquot and store at -20°C protected from light [1].

- Basal Mineral Medium (BM): For 1 liter, combine: 0.8 g K₂HPO₄, 0.2 g KH₂PO₄, 0.3 g NH₄Cl, 0.19 g Na₂SO₄, 0.07 g CaCl₂, 0.005 g FeSO₄·7H₂O, 0.16 g MgCl₂, and 0.0002 g Na₂MoO₄ [33]. Adjust pH to 7.0-7.2 and autoclave.

Equipment

- Microplate Reader: Capable of measuring absorbance (470 nm for XTT) and/or fluorescence (excitation/emission ~490/520 nm for FDA/fluorescein) [33]. A temperature-controlled incubator with shaking function is ideal.

- Aseptic Workstation: Laminar flow hood for sterile procedures.

- Centrifuge: Capable of 13,000 × g for bacterial cell pelleting.

- Spectrophotometer: For measuring optical density of bacterial cultures at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀).