Microbial Biofilm Formation: From Initial Attachment to Mature Structure and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the multi-stage process of microbial biofilm formation, a critical factor in chronic infections and antimicrobial resistance.

Microbial Biofilm Formation: From Initial Attachment to Mature Structure and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the multi-stage process of microbial biofilm formation, a critical factor in chronic infections and antimicrobial resistance. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge on biofilm life cycles with advanced methodological approaches for study and disruption. The content explores the molecular mechanisms governing attachment, maturation, and dispersion; details cutting-edge analytical and computational models; evaluates challenges in biofilm eradication; and reviews innovative therapeutic strategies. By integrating foundational science with applied research, this review serves as a strategic resource for developing novel anti-biofilm interventions.

The Biofilm Lifecycle: Deconstructing the Stages of Microbial Community Development

Biofilms are complex, structured communities of microbial cells that are attached to a surface and embedded in a self-produced matrix of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) [1] [2]. This EPS matrix is a polymeric conglomeration typically composed of extracellular polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (eDNA) [3] [2] [4]. Biofilms represent a fundamental mode of growth for microorganisms and are characterized by a unique, coordinated community lifestyle that is physiologically distinct from free-floating (planktonic) cells [5] [4].

The defining characteristics of biofilms include their three-dimensional architecture, the presence of an EPS matrix, and the emergence of community-level properties such as enhanced resistance to antimicrobial agents and environmental stresses [6] [7]. Biofilms are ubiquitous in nature and can form on both biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living) surfaces, making them significant in diverse environments from natural ecosystems to industrial settings and healthcare facilities [1] [4].

Table: Key Components of the Biofilm Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) Matrix

| Component | Primary Functions | Clinical/Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Exopolysaccharides | Structural scaffold, adhesion, cohesion, water retention [1] [3] | Major barrier to antibiotic penetration [2] |

| Proteins | Structural support, enzymatic activities, adhesion [2] | Facilitate nutrient acquisition and matrix stability [2] |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Structural integrity, genetic information exchange [2] [4] | Contributes to antibiotic resistance spread; target for disruption (e.g., DNase) [2] |

| Lipids | Hydrophobicity, barrier functions [2] | Less characterized, but contributes to matrix complexity [2] |

Historical Context of Biofilm Research

The study of biofilms has undergone a significant evolution over the past several decades. The contemporary paradigm of biofilm microbiology began to take shape in the late 1970s, largely catalyzed by the observations of J. William Costerton, a Canadian microbiologist who played a pivotal role in changing the view that microorganisms exist primarily as individual planktonic cells [3]. Costerton's work emphasized that microbial aggregates, which he termed biofilms, represent a primary mode of bacterial growth in many environments [3].

Early biofilm research relied heavily on techniques such as microscopy and culturing to investigate the basic structure and composition of biofilms [1]. A significant milestone was reached in 2004 when biofilms were conceptually identified as the root cause of non-healing and long-term infections in the majority of chronic wounds [3]. This hypothesis was strengthened in 2008 by clinical evidence from James and colleagues, who demonstrated that 60% of chronic wounds contained biofilms [3]. Subsequent studies have further solidified this connection, with research in 2012 showing that more than 80% of surgical site infections (SSIs) involve biofilm development [3].

The field has progressively advanced with the integration of molecular biology techniques and sophisticated imaging technologies, such as Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy (CSLM) and advanced Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), allowing researchers to study the complex architecture and behavior of biofilms in unprecedented detail [1] [6] [5]. This historical progression from observational studies to mechanistic and molecular investigations has fundamentally transformed our understanding of microbial biology and pathogenesis.

Clinical Significance of Biofilms

Biofilms are implicated in a substantial proportion of human microbial infections, particularly those that are chronic and recurrent in nature [2] [8]. It is estimated that 65-80% of all microbial infections are associated with biofilm formation [2] [8]. The clinical significance of biofilms stems primarily from their inherent tolerance and resistance to conventional antimicrobial therapies and host immune defenses [2]. Microorganisms within a biofilm can be up to 1,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than their planktonic counterparts [2] [7]. This recalcitrance makes biofilm-associated infections notoriously difficult to treat and eradicate, leading to persistent infections, increased morbidity, and significant healthcare costs [3] [2].

Table: Clinical Impact of Biofilms in Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs)

| Clinical Context | Key Biofilm-Related Challenges | Prevalence & Economic Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic Wounds (e.g., Diabetic Foot Ulcers, Venous Leg Ulcers) | Delay healing, induce chronic inflammation, polymicrobial interactions [3] [2]. | ~80% of DFUs before amputation; U.S. cost >$50 billion annually for chronic wound management [3]. |

| Medical Device-Associated Infections (e.g., Catheters, Implants) | Formation on abiotic surfaces, source of recurrent bloodstream infections [2] [9]. | CAUTI is a common HAI; Biofilms contribute to ~65% of microbial infections [2] [9]. |

| Cystic Fibrosis Lung Infections | P. aeruginosa biofilms in lungs resist clearance and antibiotics [2] [5]. | Major cause of morbidity and mortality; resistance enabled by EPS matrix [2]. |

| Surgical Site Infections (SSIs) | Biofilms form on tissues or implanted medical devices [3]. | >80% of SSIs develop biofilms [3]. |

The economic burden of Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs), to which biofilms are a major contributor, is staggering. In the United States alone, HAIs account for over 88,000 fatalities annually, with an estimated economic burden of USD 4.5 billion [2]. The complex structure of the EPS matrix restricts the penetration of antimicrobial agents, while the heterogeneous microenvironment within biofilms leads to the presence of metabolically dormant "persister cells" that are highly tolerant to antibiotics [2]. Furthermore, the close proximity of cells within the biofilm facilitates horizontal gene transfer, accelerating the spread of antimicrobial resistance genes among bacterial populations [3] [2].

Mechanisms of Biofilm Formation

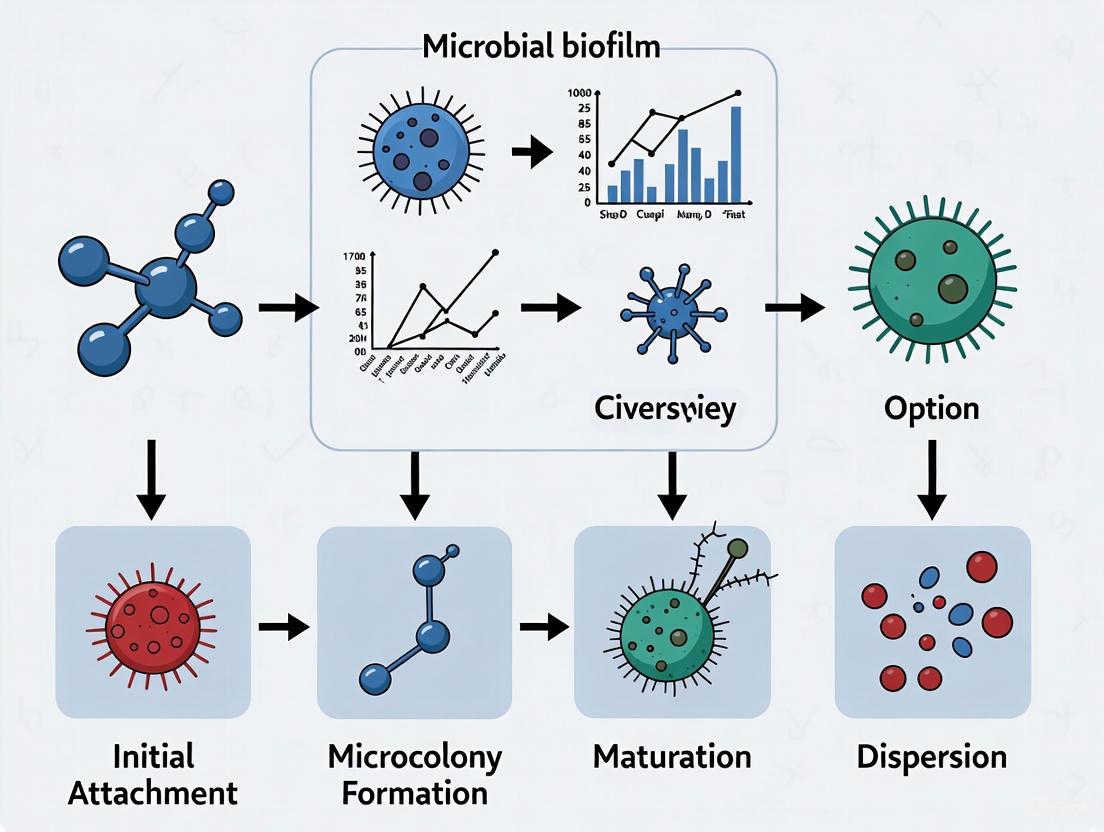

The development of a biofilm is a dynamic and cyclic process that occurs in several distinct, sequential stages [1] [3] [4]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted anti-biofilm strategies.

Diagram: The Five Key Stages of Biofilm Development. The process begins with the attachment of free-floating planktonic cells and progresses through irreversible attachment, microcolony formation, maturation of a three-dimensional structure, and active dispersal, which can seed new biofilm sites [1] [3] [4].

Initial Attachment: The first stage involves the reversible attachment of planktonic microorganisms to a surface, mediated by weak physical forces such as van der Waals forces and hydrophobic interactions [4]. This attachment can be influenced by environmental cues such as nutrient availability and surface properties [8].

Irreversible Attachment and EPS Production: Once attached, cells begin to produce EPS, leading to a firm, irreversible attachment. Adhesive structures such as pili and fimbriae play a critical role in this stabilization [4]. The cells start to form a monolayer and begin coordinated cell-to-cell communication [1].

Early Development and Microcolony Formation: The attached cells proliferate and form microcolonies, which are the foundational units of the mature biofilm. The production of EPS increases significantly, creating a protective microenvironment [3].

Maturation: The biofilm develops a complex, three-dimensional architecture characterized by tower-like structures and mushroom-shaped microcolonies interspersed with a network of water channels that facilitate the distribution of nutrients, oxygen, and signaling molecules, while also removing waste products [1] [5]. This stage is regulated by a density-dependent communication system known as Quorum Sensing (QS), which allows bacterial cells to coordinate gene expression based on population density [5] [7].

Dispersal: This final stage is an active process where individual cells or small clusters detach from the mature biofilm to colonize new surfaces [1] [4]. Dispersal can be triggered by various factors including nutrient depletion, oxygen limitation, and signaling molecules such as nitric oxide or cis-2-decenoic acid [4]. Enzymes that degrade the EPS matrix, such as dispersin B and deoxyribonuclease, facilitate this process [4].

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The study of biofilms requires specialized methodologies for quantification and visualization, as traditional microbiological techniques designed for planktonic cells are often inadequate [6] [9]. A combination of quantitative and qualitative methods is typically employed to fully characterize biofilm formation, structure, and composition.

Quantitative Biofilm Assessment Methods

Various direct and indirect methods are used to quantify biomass and viable cells within a biofilm [6].

Table: Common Quantitative Methods for Biofilm Analysis [6]

| Method | Principle | Key Applications & Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony Forming Units (CFU) | Viable cells are dislodged, serially diluted, plated on agar, and counted after incubation [6]. | Gold standard for enumerating viable cells; differentiates live from dead [6]. | Time-consuming (24-72 hrs); labor-intensive; susceptible to cell clumping errors [6]. |

| Crystal Violet (CV) Staining | A dye that binds to proteins and polysaccharides is used to stain total biofilm biomass, which is then solubilized and measured spectrophotometrically [6]. | High-throughput; measures total adhered biomass (live and dead); inexpensive [6]. | Does not distinguish between live and dead cells; can be influenced by EPS composition [6]. |

| ATP Bioluminescence | Measures ATP from metabolically active cells using a luciferin-luciferase reaction that produces light [6]. | Very rapid (minutes); highly sensitive; correlates with viable cell count [6]. | Signal can be affected by environmental conditions and sample matrix [6]. |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) | Measures mass change (ng/cm²) per unit area by detecting the change in oscillation frequency of a crystal upon biofilm attachment [6]. | Real-time, label-free monitoring of initial attachment and growth [6]. | Requires specialized equipment; measures total mass including non-cellular material [6]. |

A Standardized Protocol for Biofilm Extraction from Medical Devices

The following detailed protocol, optimized for urinary catheters but adaptable to other devices, combines vortexing and sonication to achieve consistent and reproducible extraction of biofilm bacteria for subsequent quantification [9].

Objective: To effectively dislodge and homogenize biofilm bacteria from the surface of an indwelling medical device for accurate quantification via CFU or other methods [9].

Materials:

- Sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Sonicating water bath (with calibrated power output)

- Vortex mixer

- Sterile containers

- Equipment for serial dilution and plating

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Biofilm Extraction. This standardized protocol using sequential vortexing and sonication steps ensures effective and reproducible recovery of biofilm bacteria from complex surfaces like catheters [9].

Procedure [9]:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Aseptically remove the medical device (e.g., catheter). Cut into segments of appropriate size (e.g., 1 cm) using sterile instruments.

- Initial Rinse: Gently dip or rinse each segment in 5 ml of sterile PBS to remove non-adherent planktonic cells. Remove residual liquid by gently tapping the segment on sterile absorbent paper.

- Initial Vortexing: Place each segment in a tube containing a known volume of fresh PBS. Vortex the tube for 30 seconds. This step helps to dislodge loosely attached biofilm layers.

- Sonication: Subject the tube to sonication in a sonic water bath for 5-10 minutes at a frequency of 40-45 kHz. This application of sound energy disrupts the strong bonds between the deeply embedded cells and the surface and helps break apart the EPS matrix. Note: Optimization of sonication time and power may be necessary for different materials and biofilm densities to balance yield against potential cell lysis.

- Final Vortexing: Remove the tube from the sonicator and vortex again for 30 seconds. This final vortexing step helps to break down the dislodged biofilm material into a more homogenous suspension of individual cells or small clusters, which is critical for accurate quantification.

- Quantification: The resulting homogenized suspension can now be used for downstream analyses, such as performing serial dilutions for CFU enumeration, ATP bioluminescence, or total protein assays [6] [9].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Reagents for Biofilm Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Violet Stain | Total biofilm biomass quantification [6]. | Staining 96-well plate biofilms for high-throughput screening of anti-biofilm compounds [6]. |

| SYTO9/Propidium Iodide (PI) | Fluorescent live/dead cell viability staining [6]. | Confocal microscopy analysis to visualize spatial distribution of live/dead cells within a biofilm's 3D structure [6]. |

| Dispersin B & DNase I | Enzymatic biofilm disruption agents targeting polysaccharide and eDNA matrix components [2] [4]. | Evaluating biofilm dispersal efficacy; potential adjunctive therapeutic agents [2] [4]. |

| Calcein-AM / TMA-DPH | Alternative fluorescent viability stain and biomass probe [10]. | Assessing biofilm viability and residual biomass after antibacterial treatment [10]. |

| N-acyl Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) | Key signaling molecules in Gram-negative bacterial Quorum Sensing [5]. | Studying QS inhibition as an anti-virulence strategy; elucidating biofilm regulation pathways [5] [7]. |

| CLED / CHROMagar | Specialized culture media that prevent swarming and allow preliminary species identification [9]. | Culturing and identifying uropathogens from polymicrobial biofilm samples, such as from catheters [9]. |

Within the meticulously coordinated process of microbial biofilm formation, the initial stage of reversible attachment is a critical determinant for subsequent community development. This phase represents a transient yet essential period where planktonic microorganisms first engage with a surface, a process mediated by weak physical forces and profoundly influenced by the surface's physicochemical properties [11]. Framed within the broader thesis of biofilm research, understanding this inaugural stage is paramount, as it presents a strategic window for intervention to prevent the establishment of resilient, antibiotic-resistant communities [10] [11]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the mechanisms governing reversible attachment, equipping researchers with the quantitative data and methodologies necessary to advance therapeutic and industrial applications in biofilm management.

Reversible attachment constitutes the first step in the multi-stage biofilm formation process, which progresses through attachment, microcolony formation, maturation, and dispersion [11]. During this initial phase, planktonic cells make initial contact with a surface but have not yet committed to a sessile lifestyle. The attachment is termed "reversible" because the cells can readily detach and return to their planktonic state, as the forces tethering them to the surface are weak and non-specific [12].

The primary forces responsible for this initial tethering are weak physicochemical interactions, including:

- Hydrophobic interactions

- Van der Waals forces

- Electrostatic interactions [12]

These forces collectively enable a provisional, low-affinity association between the microbial cell surface and the substrate. The success of this attachment is not solely dictated by microbial factors but is equally governed by surface preconditioning. This phenomenon involves the spontaneous formation of a conditioning film composed of organic molecules (e.g., proteins, polysaccharides) present in the surrounding environment, which effectively modifies the surface chemistry and topography before microbial arrival [11].

Concurrently, at the intracellular level, a crucial surface-sensing mechanism is activated. The Pil-Chp surface-sensing system detects contact with a surface and triggers an increase in the intracellular concentration of the key secondary messenger, bis-(3'-5')-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) [11]. This molecular switch promotes the transition from motility to adhesion by repressing flagella synthesis and stimulating the production of biofilm matrix components, thereby setting the stage for the transition to irreversible attachment [11].

Diagram: The molecular and physical progression from planktonic cells to irreversible attachment. The process initiates with weak forces and surface preconditioning, leading to surface sensing and increased c-di-GMP, which promotes irreversible attachment.

Quantitative Data and Surface Properties

The outcome of reversible attachment is highly dependent on the physicochemical properties of the surface. Research has demonstrated that parameters such as hydrophobicity, surface energy, and functional groups can dramatically alter attachment kinetics and microbial behavior.

Table 1: Impact of Surface Chemistry on Bacterial Attachment

| Surface Treatment | Chemical Character | Water Contact Angle (°) | Observed Biofilm Phenotype (Pantoea sp. YR343) | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFOTS | Hydrophobic | High (Not specified) | "Honeycomb" morphology | Robust biofilm propagation with logarithmic growth over time [13] |

| OTS | Hydrophobic | High (Not specified) | Conducive to biofilm formation | Used in vapor deposition for creating hydrophobic surfaces [13] |

| APTMS | Hydrophilic | Low (Not specified) | Minimal attachment | Pantoea sp. YR343 does not readily attach to hydrophilic surfaces [13] |

| MTMS | Hydrophilic | Low (Not specified) | Minimal attachment | Used in vapor deposition for creating hydrophilic surfaces [13] |

Table 2: Quantifiable Methodologies for Studying Reversible Attachment

| Methodology | Key Measurable Parameters | Technical Resolution / Throughput | Application in Reversible Attachment Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet Microfluidics with AI Analysis [14] | Biofilm/aggregate area; Growth dynamics | High-throughput (1000s of droplets); Enables single-droplet analysis | Tracks early attachment and aggregation in controlled microenvironments; Quantifies kinetic parameters |

| Functionalized Silanes with Quantitative Image Processing [13] | Surface coverage; Morphological evolution (e.g., honeycomb structure) | Medium throughput (10s of images/chip); Quantifies 2D propagation | Directly correlates surface chemistry with attachment efficiency and early biofilm morphology |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation (QCM-D) [13] | Absorbed mass; Viscoelastic properties | Sensitive to nanogram mass changes; Limited surface variety | Quantifies initial cell attachment and the role of appendages like flagella in real-time |

Experimental Protocols

To investigate the stage of reversible attachment, reproducible and controlled experimental protocols are essential. The following sections detail key methodologies for surface preparation and quantitative analysis.

Surface Functionalization via Silane Vapor Deposition

This protocol creates surfaces with defined chemical properties to study their effect on initial bacterial attachment [13].

Materials:

- Substrates: Silicon wafers with silicon dioxide coating (e.g., from Silicon Quest), diced into 20 mm x 20 mm squares.

- Silane Reagents:

- Trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl) silane (PFOTS) for hydrophobic surfaces.

- n-octadecyl(trimethoxy)silane (OTS) for hydrophobic surfaces.

- 3-aminopropyl trimethoxysilane (APTMS) for hydrophilic surfaces.

- Methoxytriethyleneoxypropyl-trimethoxysilane (MTMS) for hydrophilic surfaces.

- Equipment: Plasma cleaner (e.g., Harrick Plasma PDC-001), hot plate, enclosed glass dish.

Procedure:

- Surface Cleaning: Clean the silicon chips with filtered pressurized air (0.2 μm filter), followed by treatment in an air plasma cleaner for a minimum of 5 minutes.

- Vapor Deposition:

- For PFOTS: Place 20 μL per 80 cm² in an enclosed glass dish on a hot plate at 85°C for 4 hours.

- For APTMS: Place 40 μL per 80 cm² in an enclosed glass dish on a hot plate at 150°C for 2 hours.

- For OTS: Place 40 μL per 80 cm² in an enclosed glass dish on a hot plate at 150°C for 2 hours, followed by 2 hours with no heat.

- For MTMS: Place the sample in an enclosed glass dish for 4 hours at 65°C, followed by 1 hour at 115°C.

- Characterization: Validate surface properties by measuring the water contact angle using a goniometer (e.g., KRÜSS DSA 30). Perform measurements in triplicate with 1 μL droplets of distilled water.

Quantifying Early Attachment with Semi-Automated Image Analysis

This methodology quantifies bacterial attachment and early biofilm propagation on functionalized surfaces [13].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Fluorescently tagged strains (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343 expressing EGFP).

- Culture Media: Appropriate liquid medium (e.g., R2A for Pantoea).

- Equipment: Epifluorescence microscope (e.g., Olympus IX51) with FITC filter cube, image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, MATLAB, or Python with appropriate libraries).

Procedure:

- Sample Inoculation:

- Grow bacteria to stationary phase overnight in liquid medium.

- Dilute the culture 1:100 in fresh medium and grow to early exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.1).

- Place each functionalized substrate in a concave dish and add 3 mL of the bacterial culture.

- Incubate covered for specified time-points (e.g., 2, 4, 6, 8 hours).

- Sample Harvesting:

- Gently remove the substrate from the culture using tweezers, holding it by the corners.

- Rinse gently with 10 mL of DI water to remove loosely attached cells.

- Dry the sample using pressurized air blown through a 0.2 μm filter.

- Image Acquisition:

- Using an epifluorescence microscope, acquire a minimum of 10 images from random positions across each substrate.

- Ensure consistent microscope settings (exposure, gain) across all samples.

- Image Processing and Quantification:

- Develop or use a script in image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to perform the following:

- Apply background subtraction and thresholding to distinguish bacterial cells from the background.

- Use particle analysis functions to quantify parameters such as percent surface coverage, number of attached cells per unit area, and morphological descriptors (e.g., cluster size distribution).

- Develop or use a script in image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to perform the following:

Diagram: The experimental workflow for studying reversible attachment, from surface preparation to quantitative image analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Reversible Attachment Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Silanes (PFOTS, OTS, APTMS, MTMS) [13] | Modulate surface hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity to study surface property effects on attachment. | Creating defined hydrophobic/hydrophilic surfaces on silicon/silica substrates for controlled attachment assays. |

| HFE-7500 Perfluorinated Oil with Fluorosurf Surfactant [14] | Forms the continuous phase in droplet microfluidics; surfactant stabilizes droplets and prevents coalescence. | High-throughput generation of monodisperse microdroplets serving as isolated microenvironments for biofilm studies. |

| c-di-GMP Assay Kits (e.g., ELISA, LC-MS/MS) | Quantify intracellular c-di-GMP levels, a key secondary messenger regulating the motile-to-sessile switch. | Correlating c-di-GMP concentration with the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment in surface-sentient cells. |

| Fluorescent Protein Plasmids (e.g., pBBR1-MCS5 with EGFP) [13] | Genetically tag bacterial strains for visualization and quantification via fluorescence microscopy. | Enabling tracking of bacterial attachment dynamics on functionalized surfaces over time. |

| Dispersin B (Glycoside Hydrolase) [12] | Degrades poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) in the biofilm matrix; used as a probe for matrix function. | Testing the role of PNAG in stabilizing early microcolonies after initial attachment; an anti-biofilm agent. |

| Microfluidic Chips & Pressure Pumps (OB1, Elveflow) [14] | Generate, trap, and manipulate picoliter-to-nanoliter droplets for high-throughput, in-situ analysis. | Studying the kinetics of reversible attachment and early aggregation in thousands of isolated microhabitats in parallel. |

Within the established research framework mapping the stages of microbial biofilm formation, the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment represents a critical commitment point for surface-associated bacteria [15]. This second stage, Irreversible Attachment, is characterized by a fundamental shift from transient, physical adsorption to permanent molecular anchoring [16]. This shift is mediated by the active production of bacterial adhesins such as pili and fimbriae, and the initial secretion of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) [15]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise mechanisms governing this phase is paramount, as it represents a key therapeutic target for preventing the establishment of resilient, chronic biofilm-based infections [16].

Core Mechanisms of Irreversible Attachment

The transition to a permanent, surface-anchored existence involves a coordinated change in bacterial behavior, gene expression, and polymer production. The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms and their interrelationships during Stage 2.

Key Molecular Players and Genetic Regulation

The commitment to a biofilm lifestyle is underpinned by significant genetic reprogramming. Bacteria undergo a genetic shift, downregulating genes associated with motility and upregulating those responsible for the production of adhesins and EPS components [16]. The primary molecular effectors facilitating irreversible attachment include:

- Bacterial Adhesins: Hair-like appendages such as Type I and Type IV pili act as molecular grappling hooks, forming strong, specific interactions with the substrate surface [16]. Other surface structures, including lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in Gram-negative bacteria, also contribute to firm anchorage [15].

- Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS): The initial secretion of a matrix composed of exopolysaccharides, secreted proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (eDNA) creates a hydrated polymer network that physically enmeshes the cells and glues them to the surface [15] [16]. This matrix not only strengthens adhesion but also begins to form a protective barrier.

Quantitative Analysis of Irreversible Attachment

Quantifying the dynamics and properties of irreversible attachment is crucial for phenotyping bacterial strains and evaluating the efficacy of anti-biofilm strategies. The table below summarizes key parameters that can be measured experimentally.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for Analyzing Irreversible Attachment

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Measurement Technique | Typical Observation in Stage 2 | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion Strength | Cell Count Post-Wash | Microscopy with viability staining [17] | >80% retention of initially attached cells | Determines firmness of attachment; distinguishes from reversible phase. |

| Shear Force Resistance | Flow-cell systems with calibrated shear stress [18] | Stable adhesion under flow rates >0.5 dyn/cm² | Models biofilm resilience in physiological/industrial flow conditions. | |

| EPS Production | Polysaccharide/Protein Content | Colorimetric assays (e.g., phenol-sulfuric acid, Lowry) | Significant increase over planktonic cells & Stage 1 | Direct measure of matrix production initiation. |

| eDNA Quantification | Fluorescence staining (e.g., PicoGreen) & quantification [17] | Detectable signal in nascent matrix | Identifies a key structural and functional EPS component. | |

| Genetic Expression | Adhesin Gene (e.g., pilA) Expression | qRT-PCR or GFP transcriptional reporters [17] | Upregulation (e.g., 5-50 fold increase) | Links phenotypic attachment to genetic regulation. |

| Motility Gene (e.g., fliC) Expression | qRT-PCR | Downregulation (e.g., >10 fold decrease) | Marks the switch from motile to sessile lifestyle. | |

| Morphological | Microcolony Size & Distribution | 3D image analysis (e.g., BiofilmQ) [17] | Formation of small, structured clusters | Quantifies the transition from single cells to a community. |

Advanced image analysis software like BiofilmQ enables high-throughput, 3D quantification of these parameters directly within living biofilms, providing spatially resolved data on biofilm-internal properties [17]. The workflow for such an analysis is depicted below.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Stage 2

Protocol: Quantifying Irreversible Attachment Using Static Adhesion Assay and Image Analysis

This protocol is designed to quantitatively assess the strength and extent of irreversible attachment under controlled laboratory conditions.

1. Principle: This assay differentiates reversibly and irreversibly attached cells by subjecting surface-associated bacteria to a gentle washing step. Cells that remain attached are considered irreversibly adhered and are quantified.

2. Materials:

- Bacterial culture (late logarithmic phase)

- Appropriate growth medium

- Sterile, tissue-culture treated multi-well plates (e.g., 24-well or 96-well)

- Inverted phase-contrast or fluorescence microscope

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Fixative (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde) if endpoint assay is used.

- Fluorescent stains (e.g., SYTO 9 for total cells, propidium iodide for dead cells) if using fluorescence microscopy.

3. Procedure: 1. Inoculation: Dilute the bacterial culture to an appropriate optical density (e.g., OD600 = 0.1) in fresh medium. Add equal volumes of this suspension to the wells of the multi-well plate. Incubate the plate under optimal growth conditions for a defined period (e.g., 2-4 hours) to allow attachment. 2. Washing: Carefully aspirate the planktonic (non-attached) culture from the wells. Gently add pre-warmed PBS to each well without disturbing the adherent layer. Tilt the plate and carefully aspirate the PBS. Repeat this washing step twice. 3. Fixation (Optional): For endpoint analysis, add a fixative like 4% paraformaldehyde to the wells for 15-30 minutes. Aspirate the fixative and wash twice with PBS. 4. Staining (Optional): If using fluorescent stains, apply the stain according to the manufacturer's protocol. For a simple total cell count, a DNA stain like SYTO 9 is sufficient. 5. Microscopy and Image Acquisition: For each well, acquire multiple random images using a 20x or 40x objective. If using a flow-cell system for shear force resistance, set the pump to a defined flow rate and duration after the initial attachment phase before imaging [18]. 6. Image Analysis: * Software: Load acquired images into analysis software such as BiofilmQ [17], ImageJ, or commercial alternatives. * Segmentation: Use the software's thresholding tools (e.g., Otsu, Maximum Correlation Thresholding) to accurately distinguish bacterial cells from the background [17]. * Quantification: Analyze the segmented images to count the number of adhered cells per field of view. Calculate the average number of cells per mm². In tools like BiofilmQ, you can also quantify the biovolume (µm³) and the spatial distribution of the microcolonies.

4. Data Analysis: Compare the post-wash cell counts or biovolume between different bacterial strains, growth conditions, or treatment groups (e.g., with/ without anti-adhesion compounds). Statistical analysis (e.g., Student's t-test, ANOVA) should be performed to determine significance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Irreversible Attachment

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue-Culture Treated Plates | Provides a uniform, sterile surface for biofilm growth in static assays. | 24-well or 96-well polystyrene plates. |

| Flow-Cell Systems | Creates controlled hydrodynamic conditions to study adhesion under shear stress. | Small-scale flow cells with syringe or peristaltic pumps [18]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes | Staining for viability, total cells, and specific EPS components. | SYTO 9 (nucleic acids), Concanavalin A-Tetramethylrhodamine (polysaccharides), PicoGreen (eDNA). |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Quantifying gene expression changes during the reversible to irreversible transition. | Primers for adhesin (e.g., pilA) and EPS-related genes, reverse transcriptase, SYBR Green mix. |

| Transcriptional Reporters | Visualizing and quantifying promoter activity of target genes in real-time. | GFP, mCherry, or other fluorescent proteins fused to promoters of genes like psl or pel (EPS in Pseudomonas). |

| Image Analysis Software | High-throughput, 3D quantification of attachment and biofilm structure. | BiofilmQ [17], COMSTAT, Ilastik, ImageJ/FIJI. |

| Specific Antibodies | Detecting and localizing specific adhesin or EPS proteins. | Anti-Psl/Pel antibodies (Pseudomonas), Anti-RbmA antibodies (Vibrio cholerae) [17]. |

Stage 2, Irreversible Attachment, is a decisively commitment to the biofilm lifestyle, moving beyond transient physical forces to active, molecular-based permanence [15] [16]. The interplay of bacterial appendages and the nascent EPS matrix creates a robust foundation upon which the complex, 3D structure of a mature biofilm is built [19]. The quantitative methods and experimental frameworks detailed here provide researchers and drug developers with the tools to dissect this critical phase, offering actionable insights and specific molecular targets for innovative strategies aimed at biofilm prevention and eradication.

Microcolony formation represents a critical juncture in the biofilm life cycle, marking the transition from scattered, surface-attached cells to a structured, three-dimensional community. This stage, often designated as Stage 3 in the biofilm formation process, is characterized by bacterial aggregation and the initiation of a complex architecture that defines the mature biofilm [20] [21]. The shift from reversible to irreversible attachment triggers a rapid change in gene expression, driving the proliferating bacteria to form these initial, clustered aggregates known as microcolonies [22] [20]. This development is not merely a morphological change; it is a strategic survival adaptation. Life within a microcolony offers numerous advantages, including enhanced resistance to antimicrobial agents, protection from host immune responses and predation, and the facilitation of intercellular communication and genetic exchange [23] [24]. Understanding the mechanisms underpinning microcolony formation is therefore essential for developing strategies to combat persistent, biofilm-associated infections.

Structural and Compositional Foundations of the Microcolony

The architecture of a microcolony is fundamentally defined by the production of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS). This matrix acts as a scaffold, encasing the microbial cells and forming the foundational structure of the biofilm [25] [21]. The composition of the EPS is complex and dynamic, primarily consisting of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids (extracellular DNA, or eDNA), and lipids [22] [20] [21]. In the early stages of microcolony formation, eDNA plays a particularly critical role in stabilizing the initial aggregate, while polysaccharides and proteins become more dominant as the structure matures [21].

The EPS matrix is far from an inert scaffold. It confers critical physical and functional properties to the microcolony:

- Mechanical Stability: The dense, mesh-like structure of intertwined polysaccharide chains, often cross-linked by divalent cations (e.g., Ca²⁺ or Mg²⁺), provides significant mechanical strength, allowing the biofilm to withstand shear forces in fluid environments [20].

- Protective Barrier: The matrix serves as a biological barrier, impeding the penetration of antimicrobial agents and shielding internal cells from components of the host immune system [25] [26].

- Nutrient Reservoir: It acts as a resource-retaining system, trapping water, nutrients, and enzymes, thereby creating a unique microenvironment for the embedded cells [26].

The resulting structure is a highly viscoelastic, rubbery community that is predominantly composed of the EPS matrix, with microbial cells making up only about 10% of the total volume [20].

Table 1: Key Components of the Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) Matrix in Microcolonies

| Component | Primary Function | Significance in Microcolony Formation |

|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | Structural scaffolding; mechanical stability | Forms a dense, cross-linked mesh that provides the 3D architecture and rubber-like properties. |

| Proteins | Structural support; enzymatic activity | Provides structural integrity and facilitates metabolic processes within the biofilm niche. |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Cell-to-cell adhesion; structural integrity | Critical for initial stabilization of the aggregate in early microcolony development [21]. |

| Lipids & Nucleic Acids | Unknown/Multiple | Additional structural and potentially functional roles within the complex matrix. |

| Divalent Cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) | Ionic cross-linking | Strengthens the EPS matrix by forming bridges between anionic polymer chains [20]. |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling in Microcolony Development

Genetic Regulation and Metabolic Adaptations

The transition from attached cells to a microcolony is driven by significant shifts in gene expression and metabolic physiology. Cells within the microcolony experience steep gradients of oxygen and nutrients, leading to a heterogeneous environment where different metabolic states coexist [25] [27]. Research on Pseudomonas aeruginosa has revealed that microcolony formation is specifically associated with stressful, oxygen-limiting conditions [27]. In response, the bacteria activate anaerobic and fermentative pathways.

A key regulator identified in this process is the two-component system MifSR. The response regulator, MifR, is essential for microcolony formation; inactivation of mifR results in thin, unstructured biofilms lacking microcolonies, while its overexpression leads to hyper-microcolony formation [27]. This regulatory system is functionally linked to central carbon metabolism. Under the oxygen-limited conditions within a developing microcolony, pyruvate fermentation becomes a critical adaptive process. The enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LdhA), which converts pyruvate to lactate, is required for microcolony formation [27]. Experimentally, depleting pyruvate from growth medium impairs microcolony formation, whereas its supplementation significantly enhances it [27].

Cell-to-Cell Communication via Quorum Sensing

As cell density increases within the microcolony, bacteria begin to coordinate their behavior through a process called Quorum Sensing (QS). QS is a cell-cell communication system that relies on the production, detection, and response to small, diffusible signaling molecules called autoinducers [22] [24]. When the concentration of these molecules reaches a threshold (a "quorum"), it triggers a coordinated change in gene expression across the population. In the context of microcolony formation, QS regulates the production of virulence factors and EPS components, thereby facilitating the transition from a loose aggregate to a structured, functional community [22] [23]. This sophisticated communication system ensures that energy-intensive processes like EPS synthesis are only initiated once a sufficiently large population has been established.

The following diagram illustrates the core regulatory and metabolic pathway driving microcolony formation in P. aeruginosa, integrating the MifSR regulatory system with the critical metabolic shift to pyruvate fermentation.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Studying Microcolonies

In Vitro Models and Analytical Techniques

The study of microcolony formation relies on robust experimental models that allow for controlled observation and manipulation. Individual-Based Models (IBMs) are computational approaches that simulate how individual bacterial behaviors, such as movement, adhesion, and reproduction, give rise to the emergent pattern of microcolony formation [23] [28]. These models help link individual cell actions to group-level fitness outcomes, such as survival under stress [23].

In the laboratory, a variety of physical models are used:

- Flow Cell Systems: These devices allow for the continuous provision of fresh nutrients and the removal of waste products, enabling the real-time observation of biofilm development under conditions that mimic natural environments (e.g., flowing water) or physiological conditions (e.g., blood flow over a catheter) [25].

- Static Microtiter Plate Assays: A high-throughput workhorse for biofilm research, this model is used to screen for genetic mutants or chemical compounds that affect biofilm formation. Biofilm mass is typically quantified using crystal violet staining [27].

- Drip-Flow Reactors: These simulate low-shear, semi-batch conditions and are useful for growing biofilms that are thicker and more representative of certain natural settings [25].

Analytical techniques are critical for dissecting the structure and composition of microcolonies. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) is arguably the most powerful tool, as it allows for the non-invasive optical sectioning of live biofilms, generating high-resolution, three-dimensional images of the microcolony architecture [20]. These images can be analyzed to determine biovolume, thickness, and spatial distribution of cells and matrix components. For molecular and biochemical analysis, transcriptomics and proteomics are used to identify genes and proteins that are differentially expressed during microcolony formation, as demonstrated in the study of the MifR regulon [27].

A Representative Experimental Workflow

The following workflow, based on the seminal study of the MifR-pyruvate pathway, provides a template for investigating molecular mechanisms of microcolony formation [27]:

- Generate Genetic Mutants: Create targeted gene knockouts (e.g.,

mifR::Mar,ldhAmutant) and overexpression strains (e.g., strain carryingpMJT-mifRplasmid) in the wild-type background (e.g., P. aeruginosa PAO1 or PA14). - Cultivate Biofilms: Grow biofilms of wild-type and mutant strains in a controlled system like a flow cell or a static plate, using a defined or rich medium (e.g., with varying pyruvate concentrations).

- Visualize and Quantify Architecture: Use CLSM to capture 3D images of the biofilms. Quantify architectural parameters such as microcolony biovolume, average thickness, and substratum coverage using image analysis software (e.g., COMSTAT, ImageJ).

- Conduct Molecular Profiling: Perform transcriptomic (e.g., RNA-Seq) and/or proteomic analyses on harvested biofilm cells to identify global changes in gene or protein expression between wild-type and mutant strains.

- Functional Validation:

- Biochemical Assays: Measure relevant metabolites (e.g., pyruvate, lactate) and enzyme activities (e.g., LdhA activity, c-di-GMP levels).

- Genetic Complementation: Re-introduce the functional gene into the mutant strain (e.g.,

mifR::Mar/pMJT-mifR) and confirm restoration of the wild-type microcolony phenotype. - Nutrient Manipulation: Systematically add or remove key metabolites (e.g., pyruvate) from the growth medium to assess their direct impact on microcolony formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in the experimental investigation of microcolony formation, with a specific focus on the study of the P. aeruginosa MifR-pyruvate pathway [27].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Microcolony Formation

| Reagent / Material | Type | Primary Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| Defined/Growth Media | Culture Reagent | Supports biofilm growth; used to manipulate nutrient availability (e.g., pyruvate depletion/addition) [27]. |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 / PA14 | Bacterial Strain | Wild-type model organisms for studying biofilm formation and pathogenesis [27]. |

| mifR, mifS, ldhA Mutants | Genetic Tool | Isogenic mutant strains to determine the specific role of a gene in microcolony formation [27]. |

| Complementation Plasmid (pMJT-mifR) | Genetic Tool | Plasmid vector carrying the wild-type mifR gene used to restore function in a mutant, confirming gene-specificity of the phenotype [27]. |

| Flow Cell System | Physical Model | Provides a controlled hydrodynamic environment for real-time, in-situ observation of biofilm development [25]. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope | Analytical Instrument | Enables non-destructive, high-resolution 3D imaging of live microcolony architecture and matrix components [20]. |

| RNA Sequencing Kits | Molecular Biology Reagent | For global transcriptomic profiling to identify genes differentially expressed during microcolony development [27]. |

| Pyruvate | Metabolic Substrate | Key metabolite used to test the hypothesis that pyruvate fermentation is essential for microcolony formation [27]. |

| c-di-GMP Assay Kits | Biochemical Assay | To quantify intracellular levels of cyclic di-GMP, a central secondary messenger linking metabolism to biofilm formation [27]. |

Microcolony formation is a decisive phase in the establishment of a bacterial biofilm, representing a shift from a solitary to a collective lifestyle. This process is underpinned by the production of a protective EPS matrix, sophisticated genetic regulation via systems like MifSR, and a critical metabolic adaptation to hypoxia through pathways such as pyruvate fermentation [22] [27]. The resulting structure is not a homogeneous clump of cells, but a differentiated and heterogeneous community that is inherently more resistant to antimicrobials and environmental stresses [25] [23]. A deep understanding of the molecular mechanisms and environmental cues that drive microcolony development provides a solid foundation for the subsequent stage of biofilm maturation and unveils potential therapeutic targets. Disrupting the signaling pathways or metabolic processes essential for this developmental stage offers a promising strategy for preventing the formation of resilient, chronic biofilm infections.

Within the broader context of microbial biofilm formation research, the maturation stage represents a critical transitional phase where surface-attached microcolonies evolve into complex, three-dimensional communities. This stage, termed "Maturation II," is characterized by the development of a sophisticated architectural framework and the formation of functional water channels. This in-depth technical guide examines the structural and regulatory mechanisms that underpin this process, with a specific focus on Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a model organism. A deep understanding of this stage is paramount for the development of therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting biofilm-associated infections, which are notoriously resistant to conventional antibiotics [29] [30].

Structural Composition and Key Components

The maturation of a biofilm is marked by the significant production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), which form a scaffold-like matrix. This matrix accounts for 75-95% of the biofilm's total biomass, with microbial cells constituting only 5-25% [11] [29]. This self-produced environment is fundamental to the biofilm's physical stability, pathogenicity, and recalcitrance.

Core Constituents of the EPS Matrix

The EPS is a complex amalgam of biomolecules that determine the biofilm's mechanical and functional properties.

- Exopolysaccharides: These are the primary structural components of the matrix in many bacterial biofilms. In P. aeruginosa, three exopolysaccharides are of particular importance:

- Pel: A glucose-rich polysaccharide that provides critical cell-cell adhesion and structural integrity to the biofilm [29].

- Psl: A mannose-rich polysaccharide that plays a key role in initial surface attachment and in maintaining the three-dimensional structure of mature biofilms [29].

- Alginate: Often overproduced by mucoid strains, it is crucial for the stability of the biofilm and for protecting the embedded cells from host immune responses and antibiotics [29].

- Extracellular DNA (eDNA): eDNA is a major accelerant of early biofilm development and is integral to the stability of the mature structure. It interacts with Pel and Psl polysaccharides, and eDNA-deficient biofilms show markedly increased sensitivity to detergents [29].

- Proteins: The protein component includes secreted enzymes, cell surface adhesins, and protein subunits of cell appendages. A key adhesin is CdrA, which is regulated by c-di-GMP and helps to stabilize the biofilm structure by cross-linking with Pel and Psl exopolysaccharides [29].

Table 1: Key Exopolysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Maturation

| Polysaccharide | Composition | Primary Function in Maturation |

|---|---|---|

| Pel | Glucose-rich | Provides cell-cell adhesion and structural integrity |

| Psl | Mannose-rich | Maintains 3D architecture and surface attachment |

| Alginate | Acetylated polymannuronic/guluronic acid | Enhances stability and resistance to host defenses/antibiotics |

Architectural Features: Water Channels and Heterogeneity

A defining characteristic of a mature biofilm is its heterogeneous three-dimensional architecture. This structure is not a uniform monolayer but rather a constellation of towering "mushroom-shaped" or "column-like" microcolonies separated by a network of interstitial voids, known as water channels [11] [29].

These water channels are critical for the functionality of the biofilm, acting as a primitive circulatory system. They facilitate the passive diffusion of nutrients and oxygen into the deeper layers of the biofilm and allow for the efficient removal of metabolic waste products [11]. This creates a myriad of microenvironments within the biofilm, leading to metabolic and phenotypic heterogeneity among the constituent cells. This spatial organization is a key factor in the biofilm's enhanced tolerance to antimicrobial agents [30].

Molecular Regulation of Maturation

The transition from a microcolony to a complex 3D structure is tightly regulated by intracellular signaling molecules and sensory systems.

The Central Role of c-di-GMP

The secondary messenger bis-(3',5')-cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) is a master regulator of the switch from motile, planktonic lifestyles to sessile, biofilm-forming ones. A high intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP promotes biofilm formation by:

- Enhancing the production of exopolysaccharides (Pel, Psl, alginate) and adhesins like CdrA [29].

- Simultaneously repressing the expression of flagellar genes, thereby inhibiting motility and promoting irreversible attachment [29].

The cellular level of c-di-GMP is itself regulated by various signal transduction pathways. One key system is the Wsp chemosensory pathway, which is activated by the surface-sensing protein WspA. This pathway leads to the activation of the response regulator WspR, which in turn stimulates the production of c-di-GMP. Key receptors for c-di-GMP, such as FleQ and PelD, then drive the expression of exopolysaccharide operons, cementing the biofilm state [29].

Signaling Pathway and Regulatory Network

The diagram below illustrates the core regulatory network that drives the maturation of biofilm architecture.

Regulatory Network in Biofilm Maturation

Experimental Analysis of Maturation Architecture

The quantitative analysis of a mature biofilm's complex architecture requires specialized methodologies that go beyond traditional microbiological techniques like colony-forming unit (CFU) counts.

Key Experimental Protocol: Confocal Microscopy and Viability Staining

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) combined with fluorescent staining is the gold standard for visualizing and quantifying the 3D structure and viability of biofilms [31].

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Biofilms are grown on relevant substrates (e.g., plastic, glass, or biomaterial surfaces) under controlled conditions.

- Viability Staining: The biofilm is stained using a viability kit, most commonly the FilmTracer LIVE/DEAD Biofilm Viability Kit.

- SYTO 9: This green-fluorescent stain labels all bacteria, both live and dead, by penetrating intact cell membranes.

- Propidium Iodide: This red-fluorescent stain penetrates only bacteria with damaged membranes, labeling dead or dying cells.

- Critical Consideration: Propidium iodide can also bind to extracellular DNA (eDNA) present in the matrix, which can lead to false positives if not analyzed correctly. It is therefore essential to analyze the red and green channels separately during image processing [31].

- Image Acquisition: The stained biofilm is imaged using a CLSM, which collects high-resolution optical sections at various depths (z-stacks). These z-stacks are then used to reconstruct a 3D model of the biofilm.

- Image Analysis:

- Automated Analysis: To avoid user subjectivity and improve throughput, automated image analysis software is employed. Tools like BiofilmQ can quantify a wide range of parameters, including total biomass, biovolume, surface coverage, thickness, and spatial distribution of live/dead signals [32].

- Validation: The accuracy of automated methods is often validated by comparing results with traditional CFU counts and performing sensitivity/specificity analyses to ensure the algorithm correctly identifies bacterial pixels versus background [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Analyzing Biofilm Maturation

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| FilmTracer LIVE/DEAD Kit | Fluorescent staining for simultaneous assessment of biofilm viability and overall structure via CLSM. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM) | High-resolution 3D visualization and image acquisition of biofilm architecture. |

| BiofilmQ Software | Comprehensive, open-source image analysis software for quantifying architectural features and fluorescence from CLSM data. |

| SYTO 9 Stain | Green-fluorescent nucleic acid stain labeling all bacterial cells in a biofilm. |

| Propidium Iodide | Red-fluorescent stain labeling dead cells and extracellular DNA (eDNA) within the matrix. |

| 96-well Polystyrene Plates | Standard substrate for high-throughput biofilm cultivation and assessment. |

| Crystal Violet Stain | Basic dye for total biofilm biomass quantification via spectrophotometry. |

Implications for Drug Development

The unique properties of mature biofilms pose a significant challenge for drug development. The EPS matrix acts as a barrier, inhibiting antibiotic penetration, while the metabolic heterogeneity and presence of dormant persister cells within the structure contribute to multidrug tolerance [33] [30]. The current clinical approach often mirrors strategies from cancer treatment, involving aggressive physical debridement to remove the biofilm nidus, combined with local delivery of high-dose antimicrobials (e.g., antibiotic lock therapy) [30].

Future therapeutic strategies are focusing on targeting the maturation process itself. These prospective approaches include:

- Quorum Sensing Inhibitors: Disrupting the cell-to-cell communication that coordinates biofilm development.

- Matrix-Degrading Enzymes: Using enzymes such as DNases to degrade eDNA or glycosidases to target exopolysaccharides, thereby destabilizing the biofilm structure and making it more susceptible to antibiotics [29] [30].

- c-di-GMP Signaling Interference: Developing compounds that lower intracellular c-di-GMP levels to trigger biofilm dispersion [29].

Given the multifactorial nature of biofilm resistance, the most promising strategies are likely to be combinatorial therapies that simultaneously target the extracellular matrix, disrupt signaling, and potentiate the activity of conventional antimicrobials [30].

Dispersion represents the crucial final stage in the biofilm life cycle, during which sessile, matrix-encased biofilm cells actively separate from the biofilm community and transition to a planktonic mode of growth [34]. This actively regulated process serves as a dissemination mechanism, enabling bacteria to colonize new niches and initiate fresh biofilm development cycles [35] [36]. Unlike passive detachment caused by external shear forces, dispersion is a genetically programmed response to specific environmental and cellular cues [34] [36]. From a therapeutic perspective, induced dispersion is being investigated as a promising antibiofilm strategy because the transition from biofilm to planktonic state renders bacteria more susceptible to conventional antimicrobial agents and host immune responses [35] [34].

This technical guide examines the molecular mechanisms, regulatory systems, and experimental methodologies underlying the biofilm dispersion process, with particular emphasis on applications for research and therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Biofilm Dispersion

Matrix Degradation Enzymes

The liberation of cells from the biofilm structure requires controlled degradation of the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. Various bacteria produce specific enzymes that target structural components of the biofilm matrix [36].

Table 1: Matrix-Degrading Enzymes Involved in Biofilm Dispersion

| Enzyme | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Substrate | Producing Bacterium | Function in Dispersion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dispersin B | 42 | Poly-β(1,6)-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (PNAG) | Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | Hydrolyzes polysaccharide component of biofilm matrix [36] |

| Alginate Lyase | 43 | Alginate (polymer of mannuronic and guluronic acids) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Degrades alginates in P. aeruginosa biofilms [36] |

| Aureolysin | 33 | Unknown matrix proteins | Staphylococcus aureus | Protease that degrades proteinaceous matrix components [36] |

| Hyaluronidase | 117 | Hyaluronan | Streptococcus spp. | Breaks down hyaluronic acid in biofilm matrix [36] |

| Glycosidases & Deoxyribonucleases | Variable | Exopolysaccharides & eDNA | Various species | Target polysaccharide backbones and extracellular DNA networks [34] [11] |

Regulatory Pathways and Signaling Molecules

Dispersion is regulated by complex signaling networks that integrate environmental cues with intracellular second messenger systems.

Figure 1: Regulatory pathways controlling biofilm dispersion. The diagram illustrates how environmental cues and signaling molecules converge through the c-di-GMP regulatory network to activate the dispersion response.

The intracellular second messenger cyclic dimeric guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) serves as a central regulator of the transition between sessile and motile lifestyles in bacteria [37]. High intracellular c-di-GMP levels promote biofilm formation through increased matrix production, while low c-di-GMP levels induce dispersion [37]. This reduction in c-di-GMP is triggered when environmental signals such as nutrient limitation, oxygen availability, or accumulated waste products activate phosphodiesterases that degrade c-di-GMP [34].

Diffusible Signal Factors (DSF), particularly cis-2-decenoic acid, induce dispersion by binding to receptor proteins like RpfR, which stimulates c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase activity [37]. This decreases intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations, triggering downstream dispersion responses including production of matrix-degrading enzymes and activation of motility mechanisms [37].

Research Methodologies for Studying Dispersion

Experimental Models and Assay Systems

Table 2: Model Organisms for Dispersion Research

| Organism | Relevance | Key Dispersion Mechanisms | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Well-characterized model system for biofilm development | DSF-mediated c-di-GMP reduction, matrix enzyme production | Study of regulatory networks, therapeutic testing [34] [37] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Clinical relevance in medical device infections | Protease-mediated matrix degradation (e.g., aureolysin) | Antimicrobial susceptibility testing [36] |

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | Oral biofilm former | Dispersin B production | Enzyme-based dispersion studies [36] |

| Mixed cultures from MBR sludge | Environmental and industrial biofouling | Community-level responses to DSF signals | Biofouling control research [37] |

Quantitative Dispersion Assessment Methods

Optical Density-Based Assay

Protocol:

- Grow biofilms in standard microtiter plates or flow cells for 24-48 hours until mature.

- Treat with experimental dispersion-inducing compounds (e.g., CDA at 10-100 μM concentrations).

- Gently rinse to remove non-adherent cells.

- Measure optical density (OD₆₀₀) of the planktonic phase after induced dispersion.

- Compare treatment groups to untreated controls [37].

Data Interpretation: Increased OD in treatment groups indicates enhanced cell liberation from biofilms. This simple assay provides quantitative comparison of dispersion efficacy across different conditions [37].

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) with Image Analysis

Protocol:

- Grow biofilms on appropriate surfaces compatible with microscopy.

- Treat with test compounds and incubate for specified durations.

- Stain with appropriate fluorescent dyes (e.g., SYTO9 for live cells, ConA for polysaccharides).

- Capture z-stack images using CLSM at multiple random positions.

- Analyze using image analysis software (e.g., COMSTAT, ImageJ) to quantify structural parameters [37].

Quantitative Parameters:

- Total Biomass: Reduction indicates dispersion effectiveness.

- Mean Thickness: Thinner biofilms suggest active dispersion.

- Surface-to-Biovolume Ratio: Higher values correlate with more dispersed structures.

- Roughness Coefficient: Increased roughness may indicate irregular dispersion patterns [37].

Dispersion Index (DI)

The Dispersion Index integrates multiple CLSM-derived parameters into a single quantitative measure:

Calculation: DI = f(Biomass reduction, Thickness decrease, Structural complexity changes)

This integrated approach enables standardized comparison of dispersion effects across different experimental conditions and treatment modalities [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Dispersion Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispersion-Inducing Signals | cis-2-Decenoic acid (CDA), Nitric oxide donors | Experimental induction of dispersion response | Dose-dependent effects; typical range 1-100 μM [37] |

| Matrix Degrading Enzymes | Dispersin B, Alginate lyase, DNase I | Direct degradation of EPS components; positive controls | Useful for validating dispersion assays [36] |

| Fluorescent Stains | SYTO9, Propidium iodide, Calcein AM, TMA-DPH | Viability assessment and biomass quantification | Differential staining for live/dead cells; TMA-DPH for biomass [10] [37] |

| c-di-GMP Modulators | Phosphodiesterase activators, Guanylate cyclase inhibitors | Manipulation of intracellular c-di-GMP levels | Tools for mechanistic studies of regulation [37] |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors | Furanones, RNAIII-inhibiting peptides (RIP) | Interference with cell-cell communication | Study connection between QS and dispersion [10] |

| EPS Composition Analysis Kits | Phenol-sulfuric acid (polysaccharides), BCA/Lowry (proteins) | Quantitative assessment of matrix components | Monitor matrix changes during dispersion [37] |

Therapeutic Applications and Translational Potential

The strategic induction of biofilm dispersion creates a therapeutic window of opportunity when newly liberated planktonic cells exhibit transient susceptibility to antimicrobial agents [35] [34]. Several therapeutic approaches leveraging dispersion mechanisms are under investigation:

Enzyme-Based Dispersion Therapies: Localized application of matrix-degrading enzymes such as dispersin B or alginate lyase to disrupt biofilm integrity [36]. Clinical applications include combination therapy with conventional antibiotics for device-related infections [10].

Signal-Mediated Dispersion: Therapeutic application of DSF molecules like CDA to trigger endogenous dispersion mechanisms [37]. This approach demonstrated efficacy in membrane bioreactor systems, reducing biofouling and maintaining treatment efficiency [37].

Anti-biofilm Peptides: Novel peptides such as CRAMP-34 that induce dispersion by enhancing bacterial motility without directly killing cells, potentially reducing selective pressure for resistance [10].

Nanoparticle Delivery Systems: Engineered nanoparticles for targeted delivery of dispersion-inducing compounds to biofilm communities, improving therapeutic precision and reducing off-target effects [2].

Figure 2: Therapeutic strategy for biofilm control through induced dispersion. The workflow illustrates how triggering dispersion creates a vulnerable transitional state where conventional antimicrobials become effective against previously resistant biofilm cells.

Dispersion represents a critical, actively regulated developmental transition in the biofilm life cycle that enables bacterial dissemination and colonization of new environments. The molecular mechanisms underlying this process—particularly the central regulatory role of c-di-GMP signaling and matrix degradation pathways—provide promising targets for novel antibiofilm strategies. Advanced assessment methods, including CLSM analysis and the Dispersion Index, enable quantitative evaluation of dispersion responses in research settings. Therapeutic approaches that exploit dispersion mechanisms hold significant potential for improving outcomes in biofilm-associated infections, particularly when used in combination with conventional antimicrobials. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the complex regulatory networks controlling dispersion and to translate these findings into effective clinical interventions.

The transition from planktonic existence to structured, surface-attached biofilms represents a critical phase in the bacterial life cycle, governed by sophisticated molecular signaling systems. Among these, the second messenger cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) and quorum sensing (QS) mechanisms serve as master regulators that coordinate bacterial lifestyle switching, biofilm development, and virulence expression. This technical review examines the intricate interplay between these signaling pathways, highlighting their convergent roles in regulating biofilm initiation, maturation, and dispersal. Through comprehensive analysis of current research, we demonstrate how c-di-GMP and QS systems form integrated networks that allow bacterial communities to synchronize their behavior in response to population density and environmental cues. The mechanistic insights provided herein offer valuable perspectives for targeting biofilm-associated infections in clinical and industrial contexts.

Biofilm formation constitutes a developmental process encompassing distinct, sequential stages: initial attachment, microcolony formation, maturation, and active dispersal [38]. Each transition through these phenotypic stages is governed by precise regulatory checkpoints that ensure bacterial commitment to the biofilm lifestyle while maintaining capacity for dissemination [39]. The second messenger cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) has emerged as a central regulator driving the lifestyle switch between motile and sessile states, with elevated intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations promoting biofilm formation through exopolysaccharide production, adhesion expression, and motility inhibition [39] [38]. Concurrently, quorum sensing (QS) enables bacterial populations to coordinate group behaviors, including biofilm development, in response to critical threshold concentrations of secreted autoinducer signals [40]. Rather than operating in isolation, these systems form interconnected networks that process environmental and cellular information, creating a sophisticated regulatory circuit for biofilm morphogenesis. This review delineates the molecular mechanisms of c-di-GMP and QS signaling, their documented intersections in various bacterial species, and the experimental approaches driving their characterization.

Molecular Mechanisms of c-di-GMP Signaling

c-di-GMP Metabolism and Effector Systems

The intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP is dynamically regulated through the opposing activities of diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and phosphodiesterases (PDEs). DGCs, containing conserved GGDEF domains, synthesize c-di-GMP from two GTP molecules, while PDEs, featuring EAL or HD-GYP domains, degrade c-di-GMP to pGpG or GMP, respectively [39] [38]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a model organism for biofilm studies, exemplifies the complexity of this signaling network with one of the highest complements of these enzymes: 18 GGDEF domain proteins, 5 EAL domain proteins, 16 hybrid GGDEF-EAL proteins, and 3 HD-GYP domain proteins [39].

c-di-GMP exerts its physiological effects through interaction with diverse effector molecules including PilZ domain proteins, transcription factors, and riboswitches [39] [38]. Upon binding, c-di-GMP modulates their activity, thereby regulating cellular processes such as exopolysaccharide production, flagellar motility, and gene expression. In *P. aeruginosa, elevated c-di-GMP levels (75-110 pmol/mg in biofilms versus <30 pmol/mg in planktonic cells) transcriptionally activate matrix genes (pel, psl, cdrA) while repressing flagellar gene expression and function [39] [38].*

Table 1: Key Enzymes in c-di-GMP Metabolism and Their Functions

| Enzyme Type | Domain | Function | Example | Role in Biofilm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diguanylate Cyclase (DGC) | GGDEF | Synthesizes c-di-GMP from 2 GTP molecules | WspR (P. aeruginosa) | Activates exopolysaccharide production [39] |

| Phosphodiesterase (PDE) | EAL | Hydrolyzes c-di-GMP to linear pGpG | RocR (P. aeruginosa) | Promotes transition to motile lifestyle [39] |

| Phosphodiesterase (PDE) | HD-GYP | Hydrolyzes c-di-GMP to two GMP molecules | PA4108 (P. aeruginosa) | Regulates virulence and motility [39] |

c-di-GMP in Biofilm Development Stages

The role of c-di-GMP extends throughout the biofilm lifecycle, with non-uniform, hierarchical production occurring at specific developmental checkpoints rather than as a uniform cellular response [38]. Surface attachment triggers rapid c-di-GMP production through at least two established sensory systems in P. aeruginosa:

- The Wsp system: Surface contact sensed through membrane perturbation activates the WspA chemoreceptor, leading to phosphorylation of the WspR DGC and subsequent c-di-GMP production that induces Pel and Psl exopolysaccharide synthesis [38].

- The Pil-Chp system: Mechanical tension on type IV pili during surface attachment activates a signaling cascade through PilJ and ChpA, ultimately leading to cAMP-Vfr mediated production of PilY1, which stimulates c-di-GMP synthesis by the SadC DGC [38].

During biofilm maturation, elevated c-di-GMP levels promote matrix production and repress motility, cementing the sessile lifestyle. Finally, during dispersal, activated PDEs degrade c-di-GMP, facilitating the return to planktonic existence [41] [38].

Quorum Sensing Systems in Bacterial Communities

QS Signaling Molecules and Regulatory Networks

Quorum sensing enables bacterial populations to synchronize gene expression in response to cell density through the production, secretion, and detection of extracellular autoinducer molecules. In Gram-negative bacteria, the most prevalent QS signals are N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs), which vary in acyl chain length and substitution, determining system specificity [42] [40]. AHLs diffuse across cell membranes and, at sufficient concentrations, bind to and activate transcriptional regulators (LuxR-type proteins), which then modulate expression of target genes governing collective behaviors including bioluminescence, virulence factor production, and biofilm development [40].

Beyond AHLs, additional QS signals include autoinducer-2 (AI-2), a furanosyl borate diester utilized by both Gram-negative and Gram-positive species for interspecies communication, and the putrescine system recently identified in Dickeya oryzae [43] [44]. In Sinorhizobium fredii, QS mechanisms regulate crucial symbiotic functions including exopolysaccharide production, motility, and competitive nodulation in legume hosts [42].

QS in Biofilm Formation and Virulence

QS systems exert pleiotropic effects on biofilm architecture and functionality. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the LasI/LasR and RhlI/RhlR systems hierarchically regulate the production of virulence factors and biofilm matrix components [40]. Similarly, in Vibrio cholerae, QS synchronizes the expression of biofilm matrix proteins (RbmA, RbmC, Bap1) and exopolysaccharides (VPS) through the LuxO-HapR regulatory cascade [44]. QS-deficient mutants typically exhibit architecturally compromised biofilms with reduced biomass and enhanced susceptibility to antimicrobial agents, underscoring the critical role of population density signaling in biofilm robustness [40].

Integration of c-di-GMP and Quorum Sensing Signaling

Documented Mechanisms of Cross-Talk

Emerging evidence reveals extensive integration between c-di-GMP and QS pathways, forming sophisticated regulatory networks that fine-tune biofilm development in response to both intracellular and extracellular cues:

- Receptor-Mediated Interaction: In Dickeya oryzae, the c-di-GMP receptor YcgR directly interacts with and enhances the activity of SpeA, the rate-limiting enzyme in putrescine biosynthesis, thereby increasing intracellular putrescine levels. This interaction forms a regulatory loop wherein c-di-GMP molecules inhibit YcgR-mediated SpeA activation, collectively modulating bacterial motility [43].

- QS Regulation of c-di-GMP Metabolism: In Vibrio cholerae, quorum sensing activates expression of nspS-mbaA genes, increasing production of the NspS and MbaA proteins that mediate polyamine-dependent c-di-GMP biosynthesis. This QS-mediated regulation connects population density to environmental polyamine sensing, synergistically enhancing biofilm biomass and cell density [44].

- c-di-GMP Modulation of QS Signal Production: In Sinorhizobium meliloti, elevated c-di-GMP suppresses expression of the AHL synthase gene sinI and reduces AHL accumulation, demonstrating c-di-GMP-mediated repression of QS signaling [42].

Table 2: Documented Cross-Talk Mechanisms Between c-di-GMP and QS Systems

| Bacterial Species | Cross-Talk Mechanism | Biological Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dickeya oryzae | c-di-GMP receptor YcgR interacts with putrescine biosynthesis enzyme SpeA | Modulates bacterial motility and biofilm formation [43] | |

| Vibrio cholerae | QS activates nspS-mbaA expression, enhancing norspermidine-stimulated c-di-GMP production | Synergistic increase in biofilm biomass and density [44] | |

| Sinorhizobium meliloti | Elevated c-di-GMP suppresses AHL synthase gene sinI and AHL accumulation | Alters QS-mediated behaviors [42] | |

| Sinorhizobium fredii | c-di-GMP influences AHL production and regulates T6SS activity in strain-specific manner | Impacts symbiotic performance and competitive fitness [42] |