Molecular Mechanisms and Biotechnological Applications of Bacterial Acclimation to Organic Pollutant Stress

This article synthesizes current research on the sophisticated mechanisms bacteria employ to acclimate and thrive under organic pollutant stress.

Molecular Mechanisms and Biotechnological Applications of Bacterial Acclimation to Organic Pollutant Stress

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the sophisticated mechanisms bacteria employ to acclimate and thrive under organic pollutant stress. It explores the foundational molecular pathways, including signal perception, regulation networks, and enzymatic detoxification systems. Methodological approaches for isolating and characterizing pollutant-degrading strains are detailed, alongside troubleshooting for common bottlenecks in bioremediation applications. The content provides a comparative analysis of bacterial community responses to diverse pollutant classes, from hydrocarbons to surfactants, and validates these acclimation mechanisms through genomic and transcriptomic evidence. Aimed at researchers and biotechnology professionals, this review bridges fundamental microbial ecology with practical strategies for enhancing bioremediation and exploring derived biomedical applications.

Unveiling the Core: Molecular Sensing and Signaling Pathways in Bacterial Stress Acclimation

Signal perception and transduction represent the fundamental mechanisms through which bacteria sense and adapt to environmental stressors, including organic pollutants. This process initiates when bacteria detect external chemical cues, triggering intracellular signaling cascades that ultimately lead to specific cellular responses enabling survival and acclimation. Understanding these mechanisms provides crucial insights into microbial ecology and offers potential applications in bioremediation and drug development. Within the context of organic pollutant stress, bacterial acclimation involves complex regulatory networks that coordinate gene expression, metabolic shifts, and community-level interactions to mitigate toxicity and utilize pollutants as potential resources.

The increasing release of organic pollutants into environments through industrial and agricultural activities presents significant challenges to ecosystem health. Bacteria have evolved sophisticated systems to navigate these contaminated niches, with bacterial chemotaxis serving as a critical first step in this adaptive process [1]. This whitepaper examines the current understanding of how bacteria perceive organic pollutant stressors and transduce these signals to mount appropriate cellular responses, with particular emphasis on the molecular mechanisms underlying these processes and the experimental approaches used to investigate them.

Core Signaling Mechanisms in Bacterial Acclimation

Signal Perception: Chemotaxis and Chemoreceptors

Bacteria primarily perceive organic pollutants through transmembrane chemoreceptors that detect chemical gradients in their environment. This perception occurs via two principal mechanisms: metabolism-independent and metabolism-dependent chemotaxis [1].

In metabolism-independent chemotaxis, chemoreceptors known as methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) bind directly to environmental compounds without requiring metabolic transformation. These MCPs feature a periplasmic sensing domain that binds effector molecules and a cytoplasmic signaling domain that initiates signal transduction. For instance, in Escherichia coli, specific MCPs include Tar for aspartate, Tsr for serine, Trg for ribose and galactose, and Tap for peptides [1]. The naphthalene chemoreceptor NahY shows significant homology to these well-characterized MCPs, indicating a conserved mechanism for pollutant detection.

In contrast, metabolism-dependent chemotaxis requires metabolic processing of the chemical attractant. This mechanism is closely linked to cellular energy levels, where metabolizable substrates stimulate behavioral responses through receptors that detect changes in cellular energy status [1]. This form of taxis shares signaling pathways with other bacterial behavioral responses collectively known as energy taxis, including aerotaxis (response to oxygen gradients) and phototaxis (response to light). Aerotaxis is particularly relevant for organic pollutant degradation, as many oxygenases crucial for degradation pathways require molecular oxygen [1].

Intracellular Signal Transduction Pathways

Once environmental cues are perceived, the signal is transduced intracellularly through phosphorylation cascades that ultimately influence flagellar motor activity and gene expression. The well-characterized chemotaxis system of E. coli serves as a paradigm for understanding these processes [1].

The transduction mechanism involves a two-component regulatory system where chemoreceptor activation stimulates autophosphorylation of the histidine kinase CheA. CheA then transfers the phosphate group to the response regulator CheY, which undergoes conformational changes enabling interaction with the flagellar motor switch complex. This interaction switches flagellar rotation from clockwise to counterclockwise, reducing tumbling and promoting directional swimming toward favorable environments [1].

Beyond motility regulation, organic pollutant perception triggers transcriptional adaptations through various regulatory systems. These include sigma factor networks, two-component systems that modulate gene expression in response to specific pollutants, and global regulators that coordinate stress responses. These transcriptional changes enable bacteria to activate detoxification pathways, efflux systems, and metabolic routes for pollutant utilization.

Quantitative Data Synthesis of Bacterial Responses to Organic Pollutants

Research across multiple studies has quantified bacterial community and physiological responses to various organic pollutants, providing insights into acclimation dynamics. The following tables synthesize key quantitative findings from recent investigations.

Table 1: Bacterial Community Shifts in Response to Organic Pollutants

| Pollutant Type | Exposure Conditions | Key Microbial Changes | Functional Outcomes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various organic pollutants (thiamethoxam, tebuconazole, acetochlor, phenanthrene, trichlorobiphenyl) | Foliar exposure to Brassica rapa; rhizosphere analysis after 2 weeks | 19 bacterial genera consistently increased; Sphingomonas and Lysobacter showed highest average abundances | SynCom inoculation increased plant biomass and enhanced thiamethoxam degradation by 38.8% | [2] |

| High-oil food waste | Anaerobic digestion at 35°C with sludge acclimation over 30 days | Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Chloroflexi, and Proteobacteria dominant; Clostridium and Longilinea increased; Methanobacterium replaced Methanosaeta | 24.9% increase in methane yield with acclimated sludge | [3] |

| Pyrene and estrogens (E1, E2, E3, EE2) | Sediment bacterial communities from Pearl River Estuary; tolerance assays with 100 mg/L pyrene or 20 mg/L estrogens | 111 bacterial strains isolated mainly from Pseudomonadales, Vibrionales, and Rhodobacterales; distinct OTUs emerged under specific pollutants | Bacterial strains exhibited degradation capabilities and stress endurance | [4] |

| Long-term tomato monoculture | Soil analysis across different cropping durations (1-3, 5-7, >10 years) | Fungal abundance increased while bacterial richness decreased; shift from bacterial to fungal dominance in >10 years samples | Decreased metabolic activity and impaired carbon-nitrogen cycling | [5] |

Table 2: Quantitative Measurements of Microbial Community Responses

| Response Parameter | Experimental System | Measurement Technique | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhizosphere bacterial diversity | Brassica rapa with foliar organic pollutants | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing (3,469,952 sequences, 8,164 OTUs) | Significant increase in Shannon diversity index in pollutant-treated groups | [2] |

| Root exudate changes | Hydroponic plants with foliar organic pollutants | LC-QTOF/MS metabolomics | 239-259 metabolites significantly increased in root exudates across treatments | [2] |

| Methane yield improvement | Anaerobic digestion of high-oil food waste | Biogas analyzer (Geotech Biogas 5000) | 24.9% increase with acclimated sludge versus raw sludge | [3] |

| Community function influence | Sterilized plant litter decomposition with different microbial inocula | Meta-analysis of multiple studies | Microbial community composition effect on decomposition rivaled litter chemistry influence | [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Bacterial Acclimation

Tolerance Assays and Functional Strain Isolation

Investigating bacterial acclimation to organic pollutants requires well-established protocols for assessing tolerance, isolating functional strains, and characterizing community dynamics. The following methodology has been successfully employed in recent studies [4]:

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect environmental samples from polluted sites (e.g., subsurface sediments from estuaries)

- Measure in situ physiological parameters (temperature, salinity, pH)

- Store samples at 4°C during transport and process immediately upon laboratory arrival

Tolerance Assay Procedure:

- Inoculate 10 g of sediment into 100 mL of mineral salt medium (MSM) containing:

- 7.01 mM K₂HPO₄

- 2.94 mM KH₂PO₄

- 0.81 mM MgSO₄·7H₂O

- 0.18 mM CaCl₂

- 1.71 mM NaCl

- Add organic pollutants as environmental stressors:

- 100 mg/L pyrene (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon)

- 20 mg/L of various estrogens (E1, E2, E3, EE2)

- Incubate in a constant-temperature shaker at 25°C, 150 rpm

- At designated time points (1, 2, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30 days), serially dilute aliquots (100 μL) and spread onto MSM agar plates pre-treated with target pollutants

- Incubate plates at 25°C for 3 days and select colonies with different morphological features

- Streak isolates onto fresh MSM agar plates with pollutants for purification

- Culture purified strains in marine broth 2216E for cryopreservation and DNA extraction

Molecular Identification:

- Extract genomic DNA using commercial kits (e.g., Ultra-Clean microbial DNA isolation kit)

- Perform PCR amplification of 16S rRNA gene using universal primers 27F and 1492R

- Sequence amplified products and analyze using BLASTn against NCBI database

Microbial Community Analysis via High-Throughput Sequencing

Comprehensive understanding of bacterial acclimation requires characterization of community-level shifts using molecular techniques [3] [5]:

DNA Extraction and Amplification:

- Extract total microbial DNA using specialized kits (e.g., OMEGA Soil DNA Kit)

- Target specific gene regions for amplification:

- Bacterial communities: V3-V4 region of 16S rRNA gene using primers 338F/806R

- Archaeal communities: 16S rRNA gene using primers 344F/915R

- Fungal communities: ITS-V1 region using primers 1737F/2043R

- Perform PCR amplification with carefully optimized conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 98°C for 5 minutes

- 30 cycles of: 98°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, 72°C for 45s

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

Sequencing and Data Analysis:

- Verify amplification success via agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8%)

- Utilize Illumina sequencing platforms (MiSeq, NovaSeq6000)

- Process raw sequences through quality filtering, OTU clustering, and taxonomic assignment

- Conduct statistical analyses including diversity indices, differential abundance testing, and network reconstruction

Rhizosphere Recruitment Studies

For plant-associated bacterial communities, specialized protocols examine long-distance signaling effects on rhizosphere composition [2]:

Experimental Setup:

- Apply organic pollutants to plant leaves while protecting roots and soil from direct exposure

- Use control groups treated with solvent-only solutions (e.g., water with 0.1% polysorbate-80)

- Collect rhizosphere samples at designated time points (e.g., 2 weeks post-exposure)

Community Analysis:

- Extract DNA from rhizosphere soil

- Perform 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing

- Analyze data using PCoA, PERMANOVA, and LEfSe methods to identify significant community changes

- Isolate specific beneficial strains for functional validation

Functional Validation:

- Inoculate plants with isolated strains or synthetic communities (SynCom)

- Measure plant growth parameters and pollutant degradation rates

- Quantify pollutant concentrations using analytical techniques (e.g., LC-MS)

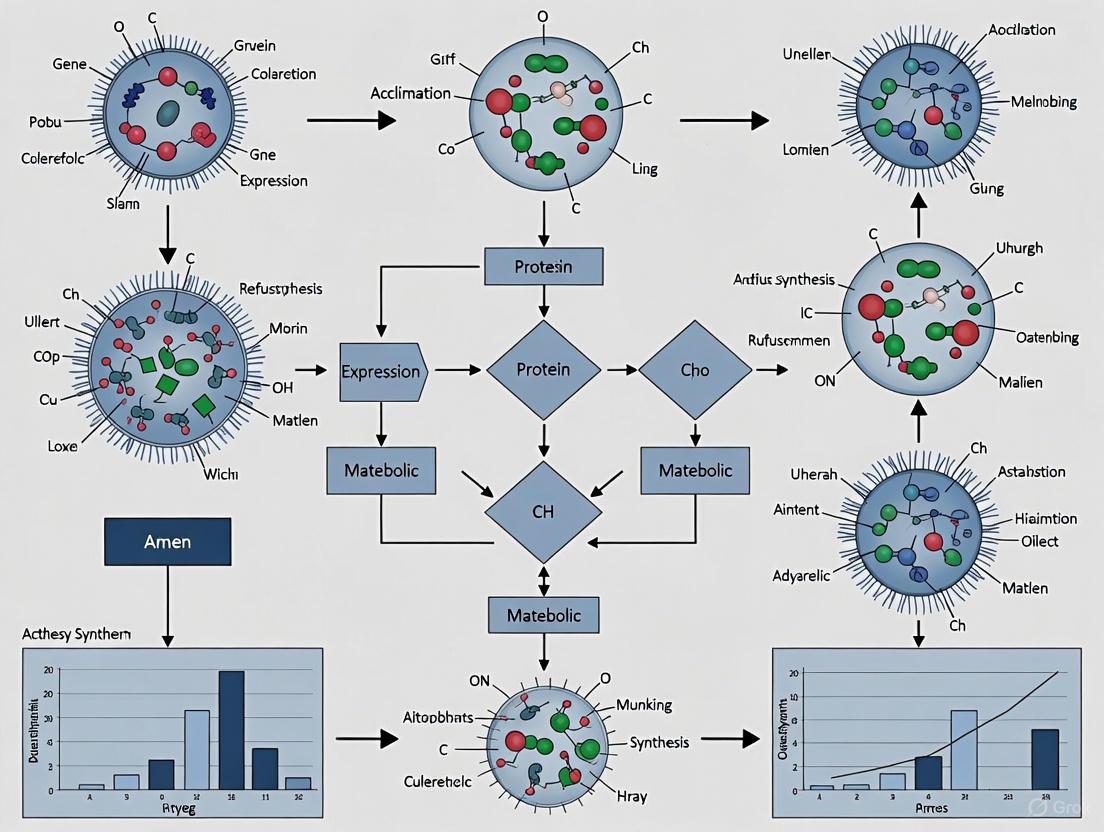

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Bacterial Chemotaxis Signaling Pathway

Experimental Workflow for Bacterial Acclimation Studies

Microbial Community Succession Under Pollutant Stress

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Bacterial Acclimation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Example | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral Salt Medium (MSM) | K₂HPO₄ (7.01 mM), KH₂PO₄ (2.94 mM), MgSO₄·7H₂O (0.81 mM), CaCl₂ (0.18 mM), NaCl (1.71 mM) | Provides essential nutrients while avoiding organic carbon sources that could interfere with pollutant studies | Tolerance assays for isolating pollutant-degrading bacteria [4] |

| Organic Pollutant Standards | Analytical grade pyrene, estrogens (E1, E2, E3, EE2), pesticides, petroleum hydrocarbons | Serve as controlled stress agents in exposure experiments | Preparing stock solutions for tolerance assays and degradation studies [4] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | OMEGA Soil DNA Kit, Ultra-Clean Microbial DNA Isolation Kit | Efficient extraction of high-quality DNA from complex environmental samples | Microbial community analysis via high-throughput sequencing [3] [5] [4] |

| PCR Primers | 16S rRNA gene: 27F/1492R, 338F/806R, 344F/915R; ITS: 1737F/2043R | Target-specific amplification of taxonomic marker genes | Bacterial and fungal community profiling [3] [5] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq, NovaSeq6000 | High-throughput sequencing of amplified gene regions | Microbial community structure and diversity assessment [3] [5] |

| Marine Broth 2216E | Standardized nutrient medium for marine bacteria | Cultivation and maintenance of isolated bacterial strains | Purification and growth of bacterial isolates from environmental samples [4] |

| Biogas Analyzer | Geotech Biogas 5000 | Quantification and composition analysis of biogas produced during anaerobic digestion | Monitoring methane production in anaerobic digestion studies [3] |

| Gas Chromatograph | Shimadzu GC-2014C with FID detector, AT-FFAP column | Separation and quantification of volatile fatty acids and organic compounds | Monitoring metabolic intermediates during pollutant degradation [3] |

Bacterial acclimation to organic pollutant stress involves sophisticated signal perception and transduction mechanisms that enable survival in contaminated environments. The integration of chemotaxis, community dynamics, and metabolic adaptation provides a robust framework for environmental persistence. Current research demonstrates that these acclimation processes are not merely incidental but represent active, coordinated responses at both cellular and community levels.

The experimental approaches outlined in this whitepaper provide researchers with robust methodologies for investigating these complex processes. As our understanding of bacterial signaling mechanisms deepens, new opportunities emerge for harnessing these natural acclimation processes in bioremediation applications and drug development targeting microbial responses to environmental stressors.

Bacterial survival in hostile environments, such as those contaminated by organic pollutants, depends on sophisticated regulatory networks that sense stress and mount an appropriate acclimation response. This whitepaper delves into three core components of bacterial regulatory biology: sigma factors, two-component systems (TCSs), and small RNAs (sRNAs). It explores their individual roles, synergistic interactions, and the resulting physiological adaptations, with a specific focus on mechanisms relevant to organic pollutant stress. The document also provides a detailed experimental methodology for investigating plant-bacterial interactions in this context and consolidates key research reagents to facilitate further scientific inquiry.

Bacteria constantly encounter fluctuating and often adverse conditions in their environments. In the context of environmental biotechnology, a significant challenge is the presence of organic pollutants, including pesticides, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and polychlorinated biphenyls. These compounds can impair microbial and plant growth, disrupting ecosystem health and bioremediation processes [7]. To acclimate, bacteria have evolved complex, multi-layered regulatory networks that allow for rapid perception of stress and precise reprogramming of gene expression. At the heart of these networks are three key players: sigma factors that redirect RNA polymerase to specific stress-response promoters; two-component systems (TCSs) that sense external stimuli via a membrane-bound histidine kinase and effect a response through a cytoplasmic response regulator; and small RNAs (sRNAs) that provide a swift, post-transcriptional layer of control. Understanding the interplay between these systems is crucial for harnessing bacterial capabilities for environmental acclimation, including the recruitment of beneficial rhizomicrobes by plants under stress [7].

Core Regulatory Elements and Their Synergistic Functions

Bacterial acclimation to stress is orchestrated by an interconnected network of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulators. The table below summarizes the primary functions of these key elements.

Table 1: Core Regulatory Elements in Bacterial Stress Acclimation

| Regulatory Element | Primary Function | Key Stressors | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sigma Factors | Direct RNA polymerase to specific gene promoters to initiate transcription. | Envelope stress, general stress, heat shock. | RpoE (σ^E^), RpoS (σ^S^), RpoH (σ^32^) [8]. |

| Two-Component Systems (TCSs) | Sense external stimuli via a histidine kinase and effect a response through a response regulator. | Acidity, osmotic pressure, metal ions, antibiotics [9] [10]. | ArsRS, CrdRS, PhoP/Q, Cpx, Rcs, CgtSR1 [9] [8] [10]. |

| Small RNAs (sRNAs) | Fine-tune gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding mRNAs or proteins. | Oxidative stress, envelope stress, nutrient deprivation [11] [8] [12]. | MicC, InvR, SgrS, RNAIII [11] [8]. |

These systems do not operate in isolation. A common regulatory paradigm involves TCSs or alternative sigma factors being activated by a specific stress signal, which in turn leads to the transcription of a regulon that includes specific sRNAs. These sRNAs then fine-tune the response by modulating the stability or translation of target mRNAs. For instance, the expression of many sRNAs is positively regulated by stress-responsive sigma factors like RpoE and RpoS, and by TCSs like PhoP/Q, Cpx, and Rcs [8]. This creates a robust, multi-tiered network enabling precise and adaptable control over bacterial physiology.

Bacterial Response to Organic Pollutant Stress: An Experimental Case Study

Plants can initiate a systemic signaling cascade to recruit beneficial rhizobacteria when their leaves are exposed to organic pollutants. The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow from leaf stress induction to downstream analysis of the plant-microbe response.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for studying plant-microbe signaling under foliar pollutant stress, based on [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following methodology is adapted from research on Brassica rapa and can be applied to investigate similar plant-microbe-pollutant interactions [7].

1. Experimental Setup and Stress Application:

- Plant Material: Use a model plant such as Brassica rapa. Grow plants under controlled greenhouse or growth chamber conditions.

- Pollutant Exposure: At a specified growth stage (e.g., 4-6 leaf stage), apply a range of organic pollutants (e.g., insecticide thiamethoxam, fungicide tebuconazole, herbicide acetochlor, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon phenanthrene) to the leaves via foliar spraying. A typical application involves dissolving pollutants in a solution containing 0.1% polysorbate-80 as a surfactant.

- Critical Control: Shield the soil and roots of the plants during spraying to prevent direct exposure to the pollutants. A control group should be treated with water containing 0.1% polysorbate-80 only.

- Sampling Timeline: Conduct rhizosphere and plant tissue sampling at multiple time points post-exposure (e.g., 2 weeks for community analysis).

2. Rhizosphere Microbiome Analysis:

- Sample Collection: Carefully collect root systems with adhering soil, which constitutes the rhizosphere compartment.

- DNA Extraction & Sequencing: Extract total genomic DNA from the rhizosphere samples. Perform 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing (e.g., targeting the V3-V4 hypervariable regions) on an Illumina MiSeq or HiSeq platform.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process raw sequences using QIIME 2 or Mothur to obtain Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs). Analyze alpha-diversity (e.g., Shannon index) and beta-diversity (e.g., Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) using PERMANOVA) to compare microbial community structure between treatment and control groups. Use statistical tools like LEfSe (Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size) to identify bacterial genera that are significantly enriched or depleted in response to foliar pollutant stress [7].

3. Analysis of Root Exudates:

- Hydroponic Cultivation: To eliminate interference from soil components and microbial metabolites, establish a parallel set of plants under hydroponic conditions.

- Exudate Collection: At a designated time post-stress (e.g., 48 hours), collect the root exudate solution. Filter the solution to remove root debris and microbial cells.

- Metabolomic Profiling: Analyze the composition of root exudates using Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (LC-QTOF/MS). Process the data with software like XCMS for peak picking, alignment, and annotation. Use multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., PCA, PERMANOVA) to identify metabolites that are significantly altered in pollutant-treated plants compared to controls [7].

4. Validation via Bacterial Isolation and Inoculation:

- Isolation of Beneficial Strains: Isalate bacterial strains (e.g., Sphingomonas sp. LSS1 and Lysobacter sp. LSS2) from the rhizosphere of pollutant-treated plants.

- Synthetic Community (SynCom) Construction: Create a defined synthetic microbial community by combining isolated beneficial strains.

- Re-inoculation Assay: Inoculate the roots of axenic or non-stressed plant seedlings with the individual strains or the SynCom (e.g., 1.0 mL of bacterial suspension with OD~600nm~ = 0.5). A control group should be treated with sterile water.

- Phenotypic Assessment: After a cultivation period (e.g., 20 days), measure plant biomass (fresh and dry weight). To assess pollutant degradation, foliar-spray re-inoculated plants with the pollutant and measure the residual concentration in plant tissues after a set period (e.g., 10 days) using techniques like HPLC-MS [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table compiles essential reagents and materials for studying the described regulatory networks and conducting related stress response experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Bacterial Stress Acclimation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Context |

|---|---|---|

| C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 | A non-pathogenic model organism for studying stress responses in actinomycetes, particularly TCS function [10]. | Used in gene deletion studies (e.g., ΔcgtS1, ΔcgtR1) to elucidate the role of TCS in antibiotic stress [10]. |

| LB & CGXII Media | Standard and defined minimal media for culturing model bacteria like C. glutamicum and E. coli under controlled conditions [10]. | CGXII minimal medium supplemented with 18 g/L glucose is used for growth studies and stress assays [10]. |

| Pollutant Stocks | Prepared solutions of organic pollutants to induce stress in experimental systems. | Thiamethoxam, tebuconazole, acetochlor, phenanthrene, trichlorobiphenyl, dissolved with 0.1% polysorbate-80 [7]. |

| Antibiotics for Selection | Selective pressure for maintaining plasmids and creating gene knockout mutants. | Kanamycin, chloramphenicol, ampicillin; specific concentrations vary by host organism [10]. |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Quantifying changes in gene expression of regulatory elements and their target genes. | Used to validate transcriptomic data, e.g., measuring expression of ncgl0887, ncgl1020, ncgl1445 in C. glutamicum [10]. |

| EMSA Reagents | Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay reagents to validate protein-DNA interactions. | Used to confirm direct binding of response regulators (e.g., CgtR1) to promoter regions of target genes [10]. |

The regulatory triad of sigma factors, two-component systems, and small RNAs constitutes a powerful and integrated network that equips bacteria to survive and thrive under the duress of organic pollutants. The detailed experimental paradigm of foliar-induced rhizobacterial recruitment demonstrates how complex signaling cascades, initiated by stress, can lead to tangible acclimation outcomes like pollutant degradation and plant growth promotion. A deep understanding of these networks, supported by the precise methodological and reagent toolkit outlined herein, provides a solid foundation for future research. This knowledge is pivotal for pioneering innovative biotechnological applications in bioremediation, sustainable agriculture, and the development of novel anti-infectives that target bacterial stress response pathways.

In the face of increasing environmental contamination, understanding biological enzymatic defense systems has become paramount for developing effective bioremediation strategies. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the sophisticated enzymatic machinery employed by bacteria and plants to detoxify and degrade major classes of organic pollutants. The content is framed within the broader context of bacterial acclimation mechanisms to organic pollutant stress, a critical area of research for addressing contemporary environmental challenges. For researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis offers both foundational knowledge and advanced experimental approaches for manipulating these natural defense systems to mitigate pollution effects and harness microbial capabilities for environmental restoration. The following sections detail specific enzymatic pathways, quantitative performance metrics, methodological protocols, and essential research tools that form the cornerstone of contemporary research in environmental biotechnology and microbial ecology.

Core Enzymatic Systems and Pathways

Phase I-III Metabolic Reactions in Plants

Plants employ a multi-phase detoxification system analogous to mammalian liver metabolism for processing organic pollutants. Phase I involves functionalization reactions, primarily catalyzed by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYPs), which introduce reactive or polar groups into xenobiotic molecules through oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis [13]. These enzymes, requiring NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) for electron transfer, activate inert pollutants for subsequent conjugation. For instance, CYP71A enzymes specifically metabolize chlorotoluron, while CYP72A isoforms hydroxylate the herbicide pelargonic acid [13].

Phase II conjugation involves transferases that link activated pollutants to endogenous hydrophilic molecules, enhancing their water-solubility and reducing toxicity. Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) conjugate the tripeptide glutathione (GSH, γ-Glu-Cys-Gly) to electrophilic centers of pesticides like atrazine and acetochlor [13]. Glycosyltransferases (GTs) attach sugar moieties to pollutants or their Phase I metabolites, while malonyl transferases further modify these glycosides. The affinity of specific pesticides for thiol conjugation depends on their molecular electrostatic potential; atrazine readily interacts with thiols due to the positive potential at its C2 atom (φ = 0.445), while acetochlor requires prior hydroxylation for efficient conjugation [13].

Phase III involves compartmentation and transport, where ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters allocate conjugated metabolites to vacuoles or apoplasts, effectively sequestering them away from active metabolic processes [13]. Research demonstrates that atrazine induces six ABC transporter genes in alfalfa, facilitating pollutant exclusion from cellular compartments.

Table 1: Key Plant Enzymes in Pollutant Detoxification

| Enzyme Class | Specific Examples | Reaction Type | Pollutant Substrates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases | CYP71A, CYP72A | Hydroxylation, Oxidation | Chlorotoluron, Pelargonic acid |

| Glutathione S-transferases | GmGSTU4 (soybean), Tau/GSTU class | Glutathione conjugation | Diphenyl ether, Chloroacetanilide herbicides |

| Glycosyltransferases | UGT73B3, UGT73B4 | Glucose conjugation | Hydroxylated pesticides |

| ABC Transporters | PGP1, MRP-type | ATP-driven transport | Atrazine, conjugated metabolites |

Bacterial Detoxification Enzymes

Bacteria employ specialized enzymatic systems for pollutant degradation, often transforming xenobiotics into carbon and energy sources. ACC deaminase is a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent enzyme that cleaves 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC), the immediate precursor of ethylene in plants, into α-ketobutyrate and ammonia [14]. This enzyme functions as a "stress modulator" in plant-microbe interactions, with a molecular mass of 105-112 kDa (trimeric form, ~36.5 kDa subunits) and optimal activity at pH 8.0-8.5 and 30°C [14]. The enzyme's Km values for ACC range from 1.5-17.4 mM, with a catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of approximately 690 M⁻¹S⁻¹ [14].

Organophosphate hydrolases degrade insecticidal compounds through hydrolysis, with microbial symbionts in insect guts contributing to sudden field control failures through rapid pesticide detoxification [15]. These enzymes can directly break down pesticides or modulate endogenous host detoxification pathways through reciprocal degradation of insecticidal and bactericidal compounds.

Bacterial oxido-reductases participate in diverse degradation pathways for complex organic pollutants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Through adaptive laboratory evolution, microbial strains can enhance their enzymatic capabilities for non-preferred substrate utilization and stress tolerance [16]. For instance, adaptation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in inhibitor-rich environments for 65 days resulted in an 80% higher ethanol yield compared to parental strains, with significantly enhanced furfural elimination capacity [16].

Table 2: Bacterial Enzymes in Pollutant Degradation

| Enzyme | Microbial Sources | Reaction | Biochemical Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACC deaminase | Pseudomonas sp., P. putida GR12-2 | Cleaves ACC to α-ketobutyrate + NH₃ | 105-112 kDa trimer, pH opt. 8.0-8.5, Km 1.5-17.4 mM |

| Organophosphate hydrolases | Insect gut symbionts | Hydrolysis of P-O, P-F, P-CN bonds | Metal-dependent, broad substrate range |

| Lignin-modifying enzymes | White-rot fungi, bacteria | Radical oxidation | Non-specific, extracellular |

| Reductive dehalogenases | Anaerobic bacteria | Reductive dehalogenation | Corrinoid-dependent, organohalide respiration |

ROS Signaling in Plant-Microbe Communication

Recent research has elucidated a sophisticated long-distance signaling mechanism wherein foliar exposure to organic pollutants triggers systemic acclimation through reactive oxygen species (ROS) waves. Leaves sensing organic pollutants generate ROS that propagate from leaves to roots via a Ca²⁺-RBOH-ROS signaling module [2]. This ROS wave stimulates two critical processes in roots: (1) increased carbon release into the rhizosphere through enhanced root cell membrane permeability, and (2) nitric oxide (NO)-mediated loosening of root cell walls, facilitating bacterial colonization [2]. This signaling cascade enriches beneficial bacterial genera like Sphingomonas and Lysobacter in the rhizosphere, which in turn promote plant growth and pollutant degradation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Rhizosphere Microbiota Recruitment Assay

This protocol characterizes the systemic response to foliar pollutant exposure and subsequent rhizosphere microbial recruitment [2].

Materials:

- Brassica rapa or similar model plant species

- Organic pollutants: thiamethoxam, tebuconazole, acetochlor, phenanthrene, trichlorobiphenyl

- Polysorbate-80 (0.1% v/v as surfactant control)

- Sterile hydroponic system or partitioned soil pots

- DNA extraction kit for soil/sediment

- 16S rRNA PCR primers (e.g., 515F/806R for V4 region)

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Plant Preparation: Germinate surface-sterilized seeds and grow plants for 14 days under controlled conditions.

- Foliar Application: Apply pollutant solutions (e.g., 100 μM in 0.1% polysorbate-80) to leaves only, using physical barriers to prevent soil contamination. Control plants receive surfactant solution only.

- Root Exudate Collection (Hydroponic): Transfer plants to sterile hydroponic systems 24h post-treatment. Collect root exudates after 48h for metabolomic analysis.

- Rhizosphere Sampling: At 14 days post-treatment, carefully harvest roots with tightly adhering soil. Separate rhizosphere soil by gentle shaking and brushing.

- Microbial Community Analysis: Extract total DNA from 0.25g rhizosphere soil using commercial kits. Amplify 16S rRNA gene regions and sequence on Illumina MiSeq or similar platform.

- Bioinformatic Processing: Process sequences using QIIME2 or Mothur pipelines. Cluster sequences into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity. Perform statistical analyses (PERMANOVA, LEFSe) to identify differentially abundant taxa.

Expected Results: Foliar pollutant exposure should significantly alter rhizosphere bacterial community composition (PERMANOVA, P < 0.05), increasing diversity (Shannon index) and specifically enriching beneficial genera like Sphingomonas and Lysobacter [2].

ACC Deaminase Activity Assay

This protocol quantifies ACC deaminase activity in bacterial isolates, a key trait for plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) [14].

Materials:

- Bacterial cultures grown in DF salts minimal medium

- ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid) substrate

- Tris-HCl buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.5)

- α-Ketobutyrate standards (0.1-1.0 mM)

- 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) reagent (0.2% in 2M HCl)

- NaOH (2M)

- Spectrophotometer

Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Grow bacterial isolates in DF salts minimal medium with (NH₄)₂SO₄ as nitrogen source. Harvest cells in late log phase by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min).

- Enzyme Induction: Wash cells and resuspend in DF salts medium with 3.0 mM ACC as sole N source. Incubate with shaking (120 rpm) at 30°C for 24h.

- Cell Lysate Preparation: Harvest cells by centrifugation, wash with 0.1M Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), and resuspend in the same buffer. Disrupt cells by sonication (3 × 20s bursts on ice) or lysozyme treatment.

- Reaction Setup: Mix 100μL cell lysate with 20μL of 0.5M ACC in Tris-HCl buffer. Incubate at 30°C for 30min.

- Product Measurement: Add 1mL DNPH reagent to the reaction mixture, incubate at 30°C for 15min. Add 1mL 2M NaOH, mix well, and measure absorbance at 540nm.

- Quantification: Generate standard curve with α-ketobutyrate (0.1-1.0 mM). Calculate ACC deaminase activity as μmol α-ketobutyrate produced mg⁻¹ protein h⁻¹.

Expected Results: ACC deaminase-positive strains (e.g., Pseudomonas putida GR12-2) typically show activities of 1-20 μmol α-ketobutyrate mg⁻¹ protein h⁻¹, varying with strain and growth conditions [14].

Pulsed Corona Discharge for Pollutant Degradation

This advanced oxidation process efficiently degrades pharmaceutical active compounds (PACs) and can be adapted for studying enzymatic degradation products [17].

Materials:

- Multiple needle-plane corona discharge reactor

- High-voltage pulsed power supply (10-30 kV, 50-200 Hz)

- Target pollutants (diclofenac, carbamazepine, ciprofloxacin)

- HPLC system with UV/fluorescence detection

- Toxicity assay kits (Microtox, Daphnia magna)

- Total Organic Carbon (TOC) analyzer

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare PAC solutions (1-10 mg/L) in Milli-Q water or natural water matrices.

- Plasma Treatment: Place 200mL solution in reactor chamber. Apply pulsed voltage (e.g., 20 kV, 100 Hz) with treatment times from 2-30min.

- Sampling: Collect aliquots at predetermined time intervals for analysis.

- Analytical Methods:

- Concentration Monitoring: Analyze parent compound degradation by HPLC.

- Mineralization: Measure TOC removal.

- Toxicity Assessment: Conduct acute toxicity tests before and after treatment.

- Parameter Optimization: Test effects of voltage (10-30 kV), frequency (50-200 Hz), pH (3-9), and water matrix components (alkalinity, NOM).

Expected Results: Complete degradation of 1 mg/L PACs within 4-8 min treatment, with mineralization yields of 0.3-0.5 g/kWh. Toxicity may initially increase due to transformation products before decreasing with extended treatment [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzymatic Defense Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pollutant Standards | Thiamethoxam, Phenanthrene, Diclofenac | Analytical quantification | Use certified reference materials for accurate calibration |

| Molecular Biology Kits | 16S rRNA amplification kits, Soil DNA extraction kits | Microbial community analysis | Select kits optimized for inhibitor-rich environmental samples |

| Enzyme Substrates | ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate), Glutathione | Enzyme activity assays | Prepare fresh solutions to prevent degradation |

| Analytical Standards | α-Ketobutyrate, GS-conjugates, Hydroxylated metabolites | Metabolite identification & quantification | Use stable isotope-labeled internal standards for precise quantification |

| Cell Culture Media | DF salts minimal medium, Luria-Bertani broth | Microbial cultivation | Use defined media for stress response studies |

| PCR Primers | 515F/806R (16S V4), GST-specific primers | Target gene amplification | Validate primer specificity for environmental samples |

| Chromatography Columns | C18 reverse-phase, HILIC | Metabolite separation | Use UPLC columns for improved resolution of complex mixtures |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Plant-Microbe ROS Signaling Pathway

Rhizosphere Recruitment Experimental Workflow

The enzymatic defense systems detailed in this technical guide represent nature's sophisticated toolkit for mitigating organic pollutant stress. From the well-characterized Phase I-III metabolic cascades in plants to the diverse degradation pathways in bacteria and the newly elucidated ROS-mediated plant-microbe communication systems, these biological mechanisms offer promising avenues for environmental restoration. The experimental methodologies and research reagents outlined provide practical resources for advancing this field. As research continues to unravel the complexity of these enzymatic systems, opportunities will emerge for engineering enhanced bioremediation strategies, developing precision bioindicators for ecosystem health, and harnessing synthetic microbial communities for targeted pollutant degradation. The integration of these natural defense systems into environmental management practices represents a sustainable path forward in addressing the challenges of environmental pollution.

Microbial consortia represent complex communities where different bacterial species interact to perform collective functions that are often unattainable by single strains. Within the context of bacterial acclimation mechanisms to organic pollutant stress, these consortia exhibit remarkable capabilities through co-acclimation and synergistic interactions. The strategic division of labor, cross-feeding relationships, and communication networks enable microbial consortia to degrade recalcitrant environmental pollutants efficiently, offering promising solutions for bioremediation challenges [18] [19].

The acclimation of microbial communities to environmental stressors involves complex physiological and genetic adaptations at the community level. When exposed to organic pollutants, microbial consortia undergo successional changes in community structure and functional specialization that enhance their collective degradation capacity [20]. This review examines the mechanisms underlying these community-level strategies, provides detailed experimental methodologies for studying consortium behavior, and presents quantitative data on degradation efficiencies achieved through coordinated microbial action.

Theoretical Foundations of Microbial Interactions

Ecological Interaction Models in Microbial Consortia

Microbial consortia exhibit various ecological interaction motifs that determine their functional stability and efficiency. These interactions can be systematically categorized based on the nature of the relationships between consortium members [19]:

- Mutualism: Both participating organisms benefit from the interaction, often through syntrophic relationships involving resource exchanges or cross-feeding

- Commensalism: One organism benefits while the other remains unaffected, commonly observed when one community member's metabolic activity modifies the environment to make it more favorable for others

- Predator-Prey: Dynamic relationships involving population control mechanisms that can stabilize community composition

- Competition: Strains compete for limited resources, which can be mitigated through programmed negative feedback mechanisms

These ecological interactions form the foundation for division of labor within consortia, where different microbial populations specialize in specific metabolic tasks that collectively contribute to the overall consortium function [21] [19]. This division of labor enables parallel processing of complex substrates, reduces metabolic burden on individual strains, and minimizes the accumulation of inhibitory intermediate products.

Conceptual Framework for Synergistic Interactions

Synergism in microbial consortia is quantitatively defined as a combined effect that exceeds the expected additive effect of individual components. In mathematical terms, for two strains A and B with individual degradation effects EA and EB, the synergistic effect EAB is observed when EAB > EA + EB [22] [23]. This superadditive effect allows microbial consortia to achieve pollutant degradation efficiencies that significantly surpass what would be predicted from the simple sum of individual strain capabilities [18].

The multiplicative model serves as a reference null model for assessing synergistic interactions, where the expected joint effect of independent stressors (or metabolic activities) follows the probability theory for independent events [23]. Significant deviations from this model indicate synergistic (greater than expected) or antagonistic (less than expected) interactions. Experimental designs for quantifying synergism must control for factors such as baseline mortality and stressor effect levels, as these significantly influence the detection of true synergistic interactions [23].

Mechanisms of Co-acclimation and Synergy

Metabolic Cooperation and Cross-Feeding

Microbial consortia employ sophisticated metabolic cooperation strategies to degrade complex organic pollutants. A key mechanism involves cross-feeding, where metabolic intermediates produced by one strain serve as substrates for other consortium members. This coordinated metabolic cascading prevents the accumulation of partially degraded products that could inhibit the degradation process [24].

Research on a sulfonamide-degrading consortium (ACJ) comprising Leucobacter sp. HA-1, Bacillus sp. HC-1, and Gordonia sp. HAEJ-1 revealed a sophisticated division of labor. In this system, Leucobacter sp. HA-1 initiated the breakdown of sulfonamide molecules, releasing heterocyclic structures and trihydroxybenzene (HHQ), which were subsequently degraded and utilized by Gordonia sp. HAEJ-1 for growth. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses indicated that genes related to nucleotide repair, ABC transporters, quorum sensing, the TCA cycle, and the cell cycle in strain HA-1 were upregulated during co-culture compared to monoculture conditions, demonstrating how cross-feeding activates growth and metabolic pathways in consortium members [24].

Signal-Mediated Coordination

Microbial consortia employ various communication mechanisms to coordinate their collective activities. These include:

- Quorum Sensing: Population-density dependent signaling using molecules such as acyl-homoserine lactones (in Gram-negative species) and small peptides (in Gram-positive species) [19]

- Metabolic Signaling: Exchange of metabolic intermediates that serve both as nutrients and signals between community members [21]

- Redox-Based Signaling: Long-distance reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling that triggers systemic responses across the consortium [2]

A fascinating example of signal-mediated coordination was documented in plants exposed to foliar organic pollutants, where a long-distance ROS wave traveled from leaves to roots via a Ca²⁺-RBOH-ROS signaling module. This signaling cascade stimulated carbon release into the rhizosphere and enriched beneficial bacterial genera (Sphingomonas and Lysobacter), demonstrating how host organisms can actively recruit and manage microbial consortia in response to stress [2].

Structural and Functional Adaptations

Microbial consortia develop structural adaptations that enhance their functionality under stress conditions. Spatial organization within biofilms creates microenvironments that facilitate metabolic complementarity, where oxygen gradients established by one community member create favorable conditions for anaerobic microbes in deeper layers [21]. This spatial structuring enables consortia to maintain metabolic processes that would be incompatible in a single homogeneous environment.

Consortia also exhibit functional redundancy and metabolic versatility that increase their resilience to environmental fluctuations. When exposed to hydrocarbons with different structures, bacterial communities showed dramatic structural reorganizations, with different taxonomic groups dominating depending on the hydrocarbon present. Despite these structural changes, the functional capacity for hydrocarbon degradation was maintained, demonstrating how consortia maintain functional stability while undergoing structural reorganization in response to environmental challenges [20].

Quantitative Analysis of Consortium Performance

Table 1: Pollutant Degradation Efficiencies by Microbial Consortia

| Pollutant Type | Consortium Composition | Degradation Efficiency | Time Frame | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrene | Mycobacterium spp. PO1/PO2, Novosphingobium pentaromativorans PY1, Ochrobactrum sp. PW1, Bacillus sp. FW1 | Significant enhancement compared to single strains | Not specified | [18] |

| Sulfonamides (SQX, SMZ, SMX) | Leucobacter sp. HA-1, Bacillus sp. HC-1, Gordonia sp. HAEJ-1 | Efficient degradation of multiple sulfonamides | 5 days | [24] |

| Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) | Hyphomicrobium sp. (46.7%) with unclassified microorganisms (53.0%) | 56.7% reduction | 20 days | [25] |

| Chlorpyrifos & Methyl Parathion | Acinetobacter sp., Pseudomonas putida, Bacillus sp., P. aeruginosa, Citrobacter freundii, etc. | 72% (methyl parathion) and 39% (chlorpyrifos) in mixture | 120 hours | [21] |

| Crude Oil Components | Specialized communities for different hydrocarbons | 66-99% for different components | 40 days | [20] |

Table 2: Synergistic Mechanisms in Microbial Consortia for Pollutant Degradation

| Mechanism Number | Mechanism Description | Key Microbial Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Synergistic metabolic degradation reducing intermediate accumulation | Pyrene-degrading consortium [18] |

| 2 | Biosurfactant production enhancing pollutant bioavailability | Bacillus sp. FW1 in pyrene degradation [18] |

| 3 | Self-regulation and adaptation during degradation | General consortium property [18] |

| 4 | Metabolic cross-feeding promoting strain growth | Sulfonamide-degrading consortium ACJ [24] |

| 5 | Crude enzyme production with high degradation activity | General consortium property [18] |

| 6 | Biochemical synergy enhancing bacterial activity | General consortium property [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Consortium Analysis

Consortium Enrichment and Isolation Protocol

The isolation and characterization of pollutant-degrading microbial consortia follows a systematic enrichment approach:

Sample Collection: Collect environmental samples from contaminated sites (e.g., activated sludge from wastewater treatment facilities, hydrocarbon-contaminated soils) [24] [25]

Selective Enrichment:

- Inoculate 2g of sample into Mineral Salt Medium (MSM) containing the target pollutant as the primary carbon source

- MSM Composition (per liter): NH₄Cl (1.0 g), KH₂PO₄ (0.5 g), K₂HPO₄ (1.5 g), NaCl (1.0 g), MgSO₄·7H₂O (0.2 g), with trace element solution [24] [25]

- Incubate in a shaker at 30°C and 150 rpm for a predetermined period (typically 10-20 days)

Serial Transfer:

- Transfer 2mL of culture to fresh medium with the same pollutant

- Repeat for 3-5 successive transfers to enrich for proficient degraders

- Monitor pollutant concentration at the end of each transfer cycle [25]

Strain Isolation:

- Plate enriched culture on solid media containing the pollutant

- Select single colonies based on morphological differences

- Identify isolates through 16S rRNA gene sequencing using primers 27F and 1492R [24]

Consortium Reconstruction:

- Combine isolated strains in defined proportions

- Verify enhanced degradation capacity compared to individual strains

"Top-Down" Functional Screening Approach

For recalcitrant pollutants where degraders are difficult to isolate, a "top-down" functional screening approach is recommended:

Continuous Enrichment: Expose the native microbial community to the target pollutant (e.g., PFOS) under various conditions, including the addition of auxiliary co-metabolic substrates (methanol, glucose, n-octane) [25]

Community Analysis: Monitor changes in community composition through 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing (e.g., MiSeq High-throughput sequencing) while tracking pollutant concentration reduction [25]

Function Prediction: Use bioinformatics tools (PICRUSt) with databases (KEGG) to predict functional capabilities of the enriched community [25] [20]

Stability Assessment: Determine when the community reaches a relatively stable state by comparing successive domestication phases (e.g., 30-day vs 40-day intervals) [20]

This approach identifies microbial consortia with desired degradation capabilities without requiring isolation of all constituent members, which is particularly valuable for including uncultivable but functionally important microorganisms.

Synergy Quantification Methods

To quantitatively assess synergistic interactions within consortia:

Experimental Design:

- Establish monocultures of each consortium member

- Establish the defined consortium combining all members

- Monitor pollutant degradation and/or biomass production over time

Data Analysis Using Multiplicative Model:

- The expected effect of non-interacting strains follows: Eexpected = 1 - [(1 - EA) × (1 - E_B)]

- Where EA and EB are the proportional effects of individual strains

- Synergy is indicated when Eobserved > Eexpected [23]

Statistical Validation:

- Compare observed vs. expected effects using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA)

- Control for factors influencing synergy detection (control mortality, stressor effect level) [23]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Microbial Consortium Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Media | Mineral Salt Medium (MSM), Lysogeny Broth (LB) | Provides nutritional base for microbial growth; MSM for selective pressure with target pollutants [24] [25] |

| Pollutant Substrates | Sulfaquinoxaline, Pyrene, PFOS-K, Tetradecane, Pristane | Target contaminants for degradation studies; selection pressure for functional consortia [24] [25] [20] |

| Co-metabolic Substrates | Methanol, Glucose, n-Octane | Auxiliary carbon sources to stimulate degradation of recalcitrant pollutants [25] |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | Primers (27F/1492R), DNA extraction kits, PCR components | 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing for community composition analysis [24] |

| Analytical Standards | 2-aminoquinoxaline, Trihydroxybenzene, Internal standards | Quantitative analysis of parent compounds and degradation intermediates via HPLC/LC-MS [24] [25] |

| Surfactants | Tween 20, Tween 80, SDS | Enhance bioavailability of hydrophobic pollutants for improved degradation [18] |

Signaling Pathways in Microbial Consortia

Microbial consortia employ sophisticated community-level strategies to acclimate to organic pollutant stress through co-acclimation mechanisms and synergistic interactions. The division of labor, metabolic cross-feeding, and signal-mediated coordination enable these communities to achieve degradation efficiencies that far surpass the capabilities of individual strains. The experimental frameworks and quantitative models presented in this review provide researchers with robust methodologies for investigating, quantifying, and harnessing these complex microbial interactions.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the molecular basis of interspecies communication, developing engineering frameworks for designing synthetic consortia with predictable functions, and integrating multi-omics approaches to unravel the complex regulatory networks governing consortium behavior. As we deepen our understanding of these community-level strategies, microbial consortia will play an increasingly important role in addressing environmental pollution challenges and advancing sustainable bioremediation technologies.

This technical guide elucidates the mechanism by which plants deploy reactive oxygen species (ROS) as a long-distance signaling molecule to recruit beneficial rhizobacteria for systemic acclimation to organic pollutant stress. Recent research reveals that foliar exposure to various organic pollutants triggers a Ca²⁺-RBOH-ROS signaling module that propagates from leaves to roots, stimulating carbon efflux and root cell wall loosening via nitric oxide (NO) to enrich specific beneficial bacterial genera. This cross-kingdom communication represents a sophisticated plant-initiated remediation strategy that enhances both pollutant degradation and plant growth tolerance, offering promising applications in sustainable agriculture and environmental remediation.

Plants constantly interact with complex microbial communities in their environment, particularly in the rhizosphere, where sophisticated cross-kingdom signaling mechanisms regulate plant-microbe interactions. When faced with environmental stressors such as organic pollutants, plants have evolved the ability to actively recruit beneficial soil microorganisms to mitigate stress and enhance survival [7]. Recent research has uncovered that reactive oxygen species (ROS), traditionally viewed as merely toxic metabolic byproducts, function as critical long-distance signaling molecules in this process [7].

Within the context of bacterial acclimation mechanisms to organic pollutant stress, this whitepaper examines how plants perceive foliar-applied organic pollutants and initiate a systemic signaling cascade that ultimately modifies the rhizosphere microbiome. This signaling results in the selective enrichment of plant-growth promoting bacteria (PGPB) and pollutant-degrading microorganisms, creating a beneficial feedback loop that enhances plant resilience and facilitates pollutant remediation [7] [26]. The mechanistic insights provided herein offer a scientific foundation for developing novel bioremediation strategies and sustainable agricultural practices that harness these natural plant-microbe communication pathways.

Core Signaling Mechanism: The ROS-Mediated Long-Distance Communication Pathway

Initial Perception and Signal Generation

The cross-kingdom signaling pathway initiates when plant leaves directly perceive various organic pollutants, including pesticides (e.g., thiamethoxam, tebuconazole, acetochlor) and industrial contaminants (e.g., phenanthrene, trichlorobiphenyl) [7]. This perception triggers the immediate generation of ROS at the site of exposure, primarily through the activation of Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homolog (RBOH) proteins, which function as NADPH oxidases specialized in ROS production [7]. The ROS generation is amplified and regulated through a Ca²⁺-RBOH-ROS signaling module, where calcium ions (Ca²⁺) bind to EF-hand motifs in RBOH proteins, further activating them for sustained ROS burst [7]. This initial response establishes the foundation for systemic signal propagation throughout the plant.

Long-Distance Signal Propagation

The locally generated ROS initiates a remarkable long-distance signaling wave that travels from the aerial tissues (leaves) to the subterranean root system [7]. This inter-organ communication occurs through a self-propagating mechanism where ROS produced in one cell stimulates calcium flux in adjacent cells, which in turn activates additional RBOH proteins to produce more ROS [7] [27]. This creates a positive feedback loop that enables the signal to traverse considerable distances through plant tissues without significant attenuation. The resulting ROS wave effectively transmits the "stress alert" from the foliar exposure site to the root system, ensuring coordinated whole-plant acclimation responses [7].

Root-Level Signaling and Microbiome Recruitment

Upon reaching the root system, the elevated ROS levels initiate two parallel processes that facilitate microbiome recruitment:

Stimulation of Carbon Efflux: ROS increases the permeability of root cell membranes, enhancing the release of carbon-containing compounds into the rhizosphere [7]. This carbon flux provides nutritional substrates that selectively enrich specific beneficial bacterial genera, particularly Sphingomonas and Lysobacter [7].

Facilitation of Bacterial Colonization: Nitric oxide (NO) functions downstream of ROS to mediate root cell wall loosening, creating favorable conditions for bacterial colonization and establishment within the root microenvironment [7].

The diagram below illustrates the complete signaling pathway from initial leaf perception to rhizobacterial recruitment:

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Data

Rhizosphere Microbiome Restructuring

Experimental studies using Brassica rapa exposed to five different organic pollutants through foliar application demonstrated consistent restructuring of rhizosphere bacterial communities, despite the absence of detectable pollutant residues in roots or soil [7]. The 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing analysis revealed significant changes in microbial composition and diversity:

Table 1: Rhizosphere Bacterial Community Changes Following Foliar Pollutant Exposure

| Parameter | Control Conditions | Pollutant-Exposed Conditions | Statistical Significance | Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Bacterial Genera | 650 genera across all samples | 650 genera across all samples | Not applicable | 16S rRNA sequencing |

| Significantly Changed Genera | Baseline | 138 genera significantly altered | P < 0.05 | LEfSe with Wilcoxon rank-sum test |

| Increased Genera | Baseline | 37-48 genera significantly increased | LDA effect size > |2.5| | LEfSe analysis |

| Decreased Genera | Baseline | 27-39 genera significantly decreased | LDA effect size > |2.5| | LEfSe analysis |

| Bacterial Diversity | Baseline reference | Significantly higher | P < 0.05 | Shannon index |

The analysis identified 19 bacterial genera that were consistently increased across all pollutant treatments, with Sphingomonas and Lysobacter exhibiting the highest average relative abundances among these enriched taxa [7]. This consistent enrichment pattern across diverse pollutant classes suggests a generalized plant response mechanism rather than pollutant-specific adaptation.

Functional Benefits of Enriched Microbiome

To quantify the functional benefits of the restructured microbiome, researchers isolated representative strains (Sphingomonas sp. LSS1 and Lysobacter sp. LSS2) from thiamethoxam-treated rhizosphere soil and evaluated their plant growth-promotion and pollutant degradation capabilities [7]:

Table 2: Functional Benefits of Enriched Rhizobacteria

| Treatment Condition | Plant Biomass Effect | Thiamethoxam Degradation (10 days post-treatment) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Sterile Water) | Baseline reference | Baseline degradation | Reference group |

| Sphingomonas sp. LSS1 | Significantly increased | 25.4% reduction in concentration | P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test) |

| Lysobacter sp. LSS2 | Significantly increased | No significant degradation effect | P > 0.05 (not significant) |

| SynCom (LSS1 + LSS2) | Greatest increase observed | 38.8% reduction in concentration | P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey's test) |

The synthetic microbial community (SynCom) demonstrated superior performance compared to individual strains, highlighting the importance of functional complementarity in microbial consortia [7]. This synergistic effect resulted in 25.2% to 55.1% lower concentrations of thiamethoxam in plants compared to control and single-strain treatments [7].

Root Exudate Modulation

Analysis of root exudates under hydroponic conditions revealed that foliar pollutant exposure significantly altered root metabolic activity and secretion [7]:

- Biomass Increase: Dried root exudate biomass increased 1.14-1.25 times compared to control groups (P < 0.05, Student's t-test) [7]

- Metabolomic Changes: LC-QTOF/MS analysis confirmed significant changes in root exudate metabolic profiles (PCA, PERMANOVA, P < 0.05) [7]

These quantitative findings demonstrate that the ROS-mediated signaling pathway generates measurable changes in root physiology and exudation patterns that ultimately drive the selective enrichment of beneficial rhizobacteria.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Plant Material and Pollutant Exposure

Experimental Organism: Brassica rapa (widely cultivated vegetable species) [7]

Pollutant Treatments:

- Insecticide: Thiamethoxam (Thia)

- Fungicide: Tebuconazole (Teb)

- Herbicide: Acetochlor (Ace)

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon: Phenanthrene (Phen)

- Polychlorinated biphenyl: Trichlorobiphenyl (Trich)

- Control: Water with 0.1% polysorbate-80 [7]

Exposure Methodology:

- Foliar spray application with precise shielding of roots and soil to prevent direct contamination

- Confirmation of no pollutant residues in roots or soil via chemical analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1 [7])

- Duration: 2 weeks for microbiome analysis; 10 days for degradation studies [7]

Microbiome Analysis

Sampling: Rhizosphere soil collection following standardized protocols [7]

DNA Extraction and Sequencing:

- Extraction: Commercial soil DNA extraction kits

- Target Regions: V3-V4 region of bacterial 16S rRNA gene

- Platform: Illumina NovaSeq6000 (or equivalent) [7] [5]

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Sequence processing: QIIME2 or similar pipeline

- Diversity analysis: Shannon index, PCoA, PERMANOVA

- Differential abundance: LEfSe analysis with Wilcoxon rank-sum test (P < 0.05, LDA effect size > |2.5|) [7]

Bacterial Isolation and SynCom Construction

Strain Isolation:

- Selective isolation from pollutant-treated rhizosphere soil

- Identification: 16S rRNA sequencing of isolates Sphingomonas sp. LSS1 and Lysobacter sp. LSS2 [7]

SynCom Assembly:

- Proportional combination of isolated strains

- Standardization: OD₆₀₀ₙ₉ = 0.5 for each strain [7]

Inoculation Protocol:

- Application: 1.0 mL bacterial suspension to roots

- Control: 1.0 mL sterile water

- Incubation: 20 days for growth promotion assessment [7]

Root Exudate Collection and Analysis

Growth System: Hydroponic culture to eliminate soil and microbial contamination [7]

Exudate Collection:

- Duration: 48-hour collection period

- Processing: Filtration, concentration, and lyophilization [7]

Metabolomic Analysis:

- Platform: LC-QTOF/MS

- Statistical analysis: PCA, PERMANOVA (P < 0.05) [7]

The experimental workflow below outlines the key steps in establishing and analyzing this plant-microbe signaling system:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Materials

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Research Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Materials | Brassica rapa seedlings | Model plant system for signaling studies | Standardized plant material for reproducible results [7] |

| Organic Pollutants | Thiamethoxam, Tebuconazole, Acetochlor, Phenanthrene, Trichlorobiphenyl | Elicitors of ROS signaling pathway | Foliar applications to induce systemic signaling [7] |

| Molecular Biology | Soil DNA extraction kits, 16S rRNA primers (338F/806R), PCR reagents | Microbiome composition analysis | DNA extraction and amplification for community profiling [7] [5] |

| Analytical Chemistry | LC-QTOF/MS systems, solvents, analytical standards | Metabolomic profiling of root exudates | Identification and quantification of root exudate compounds [7] |

| Bacterial Culture | Selective media, incubation equipment, cryopreservation solutions | Isolation and maintenance of rhizobacterial strains | Cultivation of specific bacterial isolates for functional tests [7] |

| SynCom Components | Sphingomonas sp. LSS1, Lysobacter sp. LSS2 | Functional complementarity studies | Testing synergistic effects of microbial consortia [7] |

Research Implications and Future Directions

The discovery of ROS-mediated long-distance signaling in plants represents a paradigm shift in understanding how plants actively manage their microbiome in response to environmental stress. Within the broader context of bacterial acclimation mechanisms to organic pollutant stress, these findings illuminate the sophisticated strategies plants employ to recruit external microbial assistance [7].

From an applied perspective, this research offers promising avenues for sustainable agriculture and environmental remediation. The demonstrated efficacy of synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) highlights the potential for designing specialized inoculants to enhance crop resilience in contaminated environments [7] [28]. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms of ROS perception in roots, identifying the specific carbon compounds in root exudates responsible for bacterial enrichment, and exploring the translational potential of these findings in field conditions [28].

The cross-kingdom signaling pathway detailed in this technical guide provides a mechanistic framework for understanding plant-mediated bioremediation and offers novel targets for manipulating plant-microbe interactions to address environmental challenges. As research in this field advances, the strategic application of these insights may lead to breakthrough technologies in sustainable agriculture, environmental restoration, and climate-resilient crop management.

From Lab to Field: Methodologies for Isolating, Characterizing, and Deploying Adaptive Bacteria

In the context of bacterial acclimation mechanisms to organic pollutant stress, culture-based techniques remain foundational for isolating and characterizing functional strains with bioremediation potential. Bacterial communities dynamically shift their interactions in response to environmental stressors, as explained by the Stress Gradient Hypothesis (SGH), which predicts a transition from competitive to facilitative interactions as stress increases [29]. This theoretical framework is critical for understanding how microbial communities acclimate to organic pollutants and how we can isolate strains that not only tolerate but also degrade these compounds. The molecular mechanisms behind this acclimation are sophisticated, involving long-distance signaling pathways that trigger systemic responses [2]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary culture-based methodologies for isolating and evaluating bacterial strains with enhanced organic pollutant stress tolerance, presenting standardized protocols, quantitative data comparisons, and essential resources for researchers in environmental microbiology and bioremediation.

Theoretical Framework: Microbial Community Dynamics Under Stress

The Stress Gradient Hypothesis in Microbial Ecology

The Stress Gradient Hypothesis (SGH) provides a crucial theoretical framework for understanding how bacterial interactions evolve under pollutant-induced stress. Originally developed in plant ecology, this hypothesis has been successfully applied to microbial systems, predicting that interspecific interactions shift from predominantly competitive under low-stress conditions to facilitative under high-stress conditions [29]. In the context of organic pollutant stress, this paradigm explains community-level acclimation mechanisms:

- Low Stress Conditions: Bacterial interactions are primarily competitive, driven by resource acquisition and antimicrobial strategies [29].

- High Stress Conditions: Facilitative interactions become dominant, including detoxification mechanisms that benefit intolerant species and cooperative degradation of complex pollutants [29].

This shift in interaction dynamics has profound implications for designing enrichment strategies, as it suggests that under high pollutant stress, microbial consortia may exhibit enhanced cooperative behaviors that can be harnessed for bioremediation applications.

Molecular Signaling in Plant-Microbe Systems Under Pollutant Stress

Plants and their associated microbiota engage in complex communication under pollutant stress. Recent research has elucidated a sophisticated long-distance signaling pathway that activates microbial recruitment in response to foliar organic pollutant exposure [2].

Figure 1: Long-distance ROS signaling pathway for microbial recruitment in response to organic pollutants

This signaling cascade results in the specific enrichment of beneficial bacterial genera including Sphingomonas and Lysobacter, which have demonstrated capabilities in promoting plant growth and enhancing pollutant degradation [2]. Understanding these signaling mechanisms provides valuable insights for designing selective enrichment strategies that mimic these natural recruitment processes.

Stress Tolerance Assays: Methodologies and Assessment

Quantitative Assessment of Bacterial Tolerance

Stress tolerance assays provide critical quantitative data on bacterial resilience and adaptive capacity under organic pollutant stress. These assays typically measure growth kinetics, survival rates, and degradation efficiency under controlled stress conditions. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from recent studies on bacterial responses to various organic pollutants.

Table 1: Quantitative Assessment of Bacterial Stress Tolerance to Organic Pollutants

| Pollutant Type | Experimental Organism/System | Exposure Conditions | Key Tolerance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | Choy sum endophytic bacteria (Bacillaceae) | 0.2-1 mg/L in axenic system | 9.2-27.7x higher abundance in high-accumulating variety; Enhanced root biomass and antioxidase activities | [30] |

| Phenanthrene + n-octadecane | Enriched pollutant-degrading consortia | Batch culture for 10 transfers | 29.5-95.8% phenanthrene degradation; 87.5-100% n-octadecane degradation | [31] |

| Thiamethoxam (Thia) | Sphingomonas sp. LSS1 & Lysobacter sp. LSS2 | Foliar exposure in Brassica rapa | 25.2-55.1% lower Thia concentration in SynCom-inoculated plants | [2] |

| Multiple organic pollutants | Synthetic Microbial Community (SynCom) | Laboratory degradation assay | 38.8% pollutant reduction by SynCom vs 25.4% by single strains | [2] |

Protocol: Batch Culture Stress Tolerance Assay

The following protocol adapts methodology from microbial succession studies under pollutant stress [31]:

Materials Required:

- Minimal salts medium with defined carbon sources

- Organic pollutant stock solutions (e.g., phenanthrene, n-octadecane)

- Sterile culture vessels

- Inoculum from environmental samples or defined cultures

- Incubation shaker with temperature control

Procedure:

- Preparation of Pollutant Stock Solutions: Dissolve organic pollutants in appropriate solvents (e.g., acetone for PAHs) to create concentrated stock solutions. Filter-sterilize if possible.

- Culture Medium Preparation: Add pollutant stocks to minimal medium to achieve desired test concentrations. For insoluble compounds, use sonication to create stable dispersions.

- Inoculation: Inoculate medium with bacterial cultures or environmental samples at standardized cell density (e.g., OD600 = 0.05).

- Incubation: Incubate with appropriate shaking at optimal temperature for the test organisms. Typical incubation periods range from 48 hours to 7 days.

- Monitoring and Sampling: Collect samples at regular intervals for:

- Optical density measurements (growth)

- Pollutant concentration analysis (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS)

- Community composition analysis (if using consortia)

- Endpoint Analysis: Assess final biomass, pollutant degradation efficiency, and metabolic activity.

Data Interpretation: Calculate specific growth rates, degradation percentages, and half-lives of pollutants. Compare treatment groups to controls without pollutants to determine stress-induced inhibition.

Selective Enrichment Strategies for Functional Strains

Advanced Enrichment Methodologies

Selective enrichment techniques are designed to isolate microbial populations with specific metabolic capabilities or stress tolerance traits. These approaches leverage ecological principles to gradually enrich for desired functional characteristics.

Table 2: Selective Enrichment Strategies for Pollutant-Tolerant Bacteria

| Enrichment Strategy | Target Microbes | Key Components | Success Indicators | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSB Selective Broth | Salmonella spp., E. coli O157:H7, L. monocytogenes | Novel selective broth composition | LOD <10 CFU/25 g; Sensitivity >90% | Multipathogen detection from complex matrices [32] |

| Batch-Enrichment Subculture | Pollutant-degrading consortia | Sequential transfer in pollutant-amended media | Community shift toward degraders; Reduced diversity indices | Isolation of specialist degraders [31] |

| Axenic System with Root Exudates | Seed endophytic bacteria | Sterile system with maleic acid from root exudates | Enrichment of Bacillaceae; Enhanced stress tolerance | Plant-microbe interactions study [30] |

Protocol: Multipathogen Selective Enrichment with MSB Broth

This protocol enables simultaneous enrichment of multiple bacterial pathogens from complex samples, adapted from food safety research with applications in environmental microbiology [32]:

Materials Required:

- MSB (Multipathogen Selective Broth)

- Sample material (soil, sediment, or plant tissue)

- Dilution buffers

- Selective supplements if required

- Incubation equipment

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Aseptically weigh 25 g of sample and homogenize in 225 mL of MSB broth.

- Primary Enrichment: Incubate at appropriate temperature (e.g., 35-37°C) for 18-24 hours with shaking.

- Secondary Enrichment: Transfer 1 mL of primary enrichment to fresh MSB broth and incubate for additional 18-24 hours.

- Monitoring: Observe turbidity development as indicator of microbial growth.

- Subculturing: Plate onto selective agar media for isolation of specific bacterial types.

- Confirmation: Confirm target organisms through biochemical tests, molecular methods, or sequencing.