Nanomechanical Mapping of Biofilms: A Comprehensive Guide to AFM Force Volume Technique for Elasticity Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Force Volume technique for mapping the nanomechanical properties of bacterial biofilms.

Nanomechanical Mapping of Biofilms: A Comprehensive Guide to AFM Force Volume Technique for Elasticity Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Force Volume technique for mapping the nanomechanical properties of bacterial biofilms. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of biofilm mechanics, detailed methodological protocols for Force Volume acquisition and data analysis, and strategies for troubleshooting common experimental challenges. It further validates the technique through comparative analysis with other methods and highlights its critical applications in biomedical research for understanding biofilm resilience, evaluating anti-biofilm agents, and informing the development of novel therapeutic strategies. By integrating the latest advancements, including machine learning and high-speed AFM, this guide serves as a vital resource for quantifying biofilm elasticity to combat antimicrobial resistance.

Understanding Biofilm Biomechanics and the Principles of AFM

The Critical Role of Biofilm Mechanical Properties in Antimicrobial Resistance

Biofilms represent the predominant mode of microbial growth in nature, forming structured communities of microorganisms encased in a self-produced matrix of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) [1] [2]. This matrix, comprising polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (eDNA), provides structural integrity and creates a protective environment for embedded cells [1] [2]. While the biochemical basis of antimicrobial resistance in biofilms has been studied extensively, the contribution of their physical and mechanical properties remains a critical yet underexplored frontier. The mechanical robustness of biofilms, governed by the EPS matrix, contributes significantly to their recalcitrance by limiting antimicrobial penetration and creating heterogeneous microenvironments [1] [3].

The Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) force volume technique has emerged as a powerful tool for quantifying the nanomechanical properties of biofilms under physiologically relevant conditions [4] [5]. This technique enables researchers to create spatial maps of mechanical properties such as elasticity, adhesion, and cohesiveness, providing unprecedented insight into structure-function relationships within biofilm architectures [6] [5]. Understanding how these mechanical properties contribute to antimicrobial resistance is paramount for developing novel therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting biofilm integrity and enhancing treatment efficacy for chronic infections [1] [7].

Biofilm Mechanical Properties: Quantitative Foundations

The mechanical characteristics of biofilms are primarily dictated by their EPS composition and organizational structure. Research has demonstrated that these properties are not uniform but exhibit significant spatial and temporal heterogeneity, which directly influences antimicrobial penetration and efficacy [3] [5].

Key Mechanical Parameters and Their Ranges

Table 1: Quantitative Mechanical Properties of Biofilms Measured by AFM

| Mechanical Parameter | Measurement Range | Significance in Antimicrobial Resistance | Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic Modulus (Stiffness) | 0.1 kPa - 1000 kPa | Determines resistance to deformation; higher stiffness can impede antibiotic penetration [5] [8] | EPS composition, cross-linking, bacterial species [3] [5] |

| Cohesive Energy | 0.10 - 2.05 nJ/μm³ [3] | Higher cohesion increases resistance to mechanical disruption and detachment [3] | Calcium concentration, EPS production, matrix integrity [3] |

| Adhesion Force | 0.1 - 20 nN [5] | Affects attachment to surfaces and other cells; influences biofilm stability [5] | Surface proteins, extracellular appendages, polymer interactions [6] [5] |

| Viscoelastic Properties | Varies widely | Determines time-dependent deformation and recovery; affects biofilm stability under stress [4] [5] | Polymer entanglement, water content, molecular interactions [3] [4] |

Impact of Environmental Factors on Biofilm Mechanics

Table 2: Environmental Modulators of Biofilm Mechanical Properties

| Environmental Factor | Effect on Mechanical Properties | Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Ions (10 mM) | Increases cohesive energy from 0.10 ± 0.07 nJ/μm³ to 1.98 ± 0.34 nJ/μm³ [3] | Enhances matrix integrity, reducing antibiotic penetration [3] [2] |

| Nutrient Availability | Alters EPS production and composition [1] | Modifies matrix density and diffusion barriers [1] |

| Growth Substrate | Affects biofilm architecture and mechanical heterogeneity [6] | Creates variable penetration pathways for antimicrobials [1] [6] |

| Multispecies Composition | Introduces mechanical complexity through interspecies interactions [1] | Enhances overall community resistance through niche specialization [1] [7] |

AFM Force Volume Methodology for Biofilm Elasticity Mapping

The AFM force volume technique provides a comprehensive approach for quantifying the spatial distribution of mechanical properties across biofilm surfaces. This method involves acquiring arrays of force-distance curves at predefined locations, generating detailed maps of nanomechanical properties [5] [8].

Instrumentation and Probe Selection

AFM Cantilevers: For biofilm analysis, soft cantilevers with spring constants of 0.01-0.5 N/m are recommended to prevent sample damage while ensuring sufficient sensitivity [4] [5]. Silicon nitride cantilevers with spherical tip geometries (2-5 μm diameter) are ideal for mechanical characterization as they simplify contact mechanics modeling and minimize sample indentation [4] [5].

Detection System: An infrared laser-based optical detection system with a four-quadrant photodetector enables precise measurement of cantilever deflection. The system must be calibrated for sensitivity and spring constant before measurements using thermal tuning or reference cantilevers [4] [9].

Piezoelectric Scanner: High-precision piezo components capable of sub-nanometer resolution in x, y, and z directions are essential for accurate positioning and force curve acquisition [4] [9].

Sample Preparation Protocol

Biofilm Growth: Grow biofilms on adhesion-promoting substrates (e.g., glass, polystyrene, or membrane filters) under conditions relevant to the research question. For consistent results, standardize growth medium, temperature, and incubation time (typically 24-48 hours) [3] [5].

Immobilization: Proper immobilization is critical for reliable AFM measurements. For single-species biofilms, use porous membranes with pore diameters similar to cell dimensions or chemically functionalized surfaces (e.g., poly-L-lysine coated substrates) that facilitate attachment without altering mechanical properties [5].

Hydration Maintenance: Perform AFM measurements in liquid or controlled humidity environments (>90% relative humidity) to prevent dehydration artifacts. For aqueous measurements, use physiological buffers that maintain biofilm viability and structure [3] [5].

Force Volume Acquisition Parameters

Grid Resolution: Typically 16×16 to 64×64 force curves acquired over the region of interest, balancing spatial resolution with acquisition time [8].

Approach/Retract Velocity: 0.5-2 μm/s to minimize hydrodynamic effects while maintaining measurement efficiency [5] [8].

Force Trigger: 1-10 nN, set to ensure sufficient indentation for mechanical analysis without damaging the biofilm structure [5] [8].

Z-range: Sufficient to capture the full approach and retraction cycle, typically 2-5 μm [8].

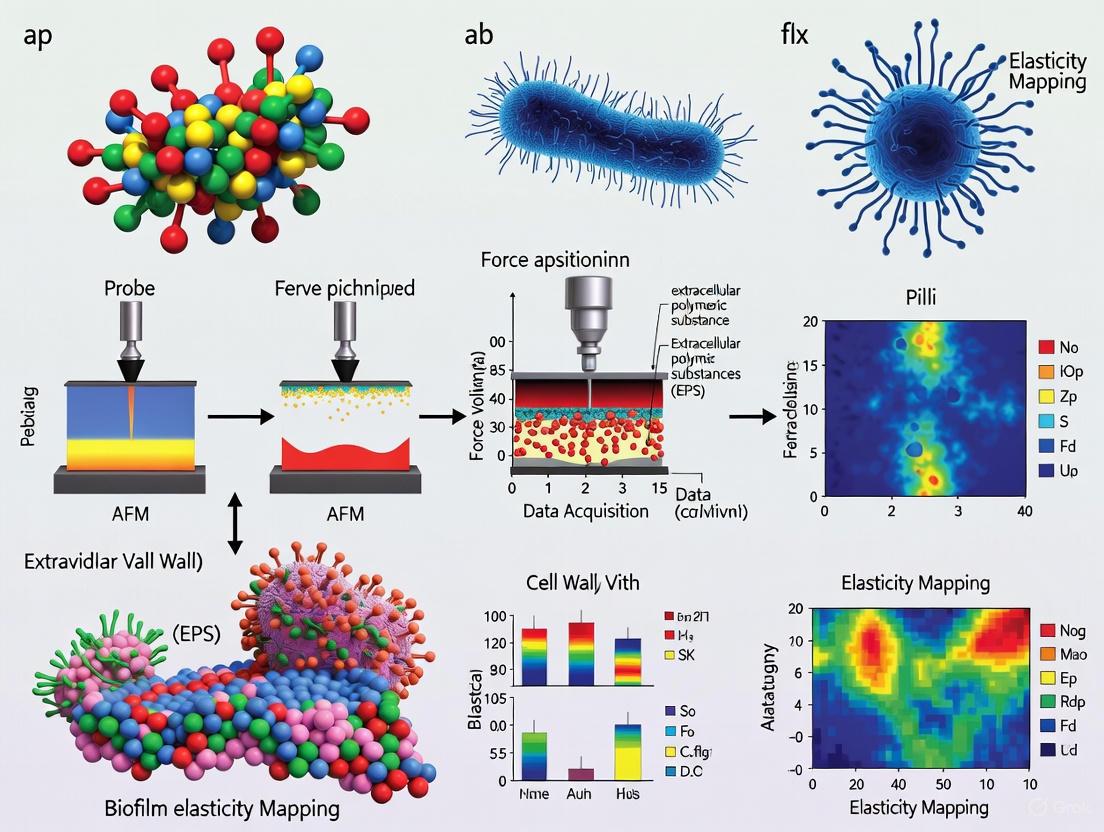

Diagram 1: AFM Force Volume Workflow for Biofilm Elasticity Mapping

Data Processing and Mechanical Analysis Protocols

Force Curve Processing Algorithm

Raw force-distance curves require sophisticated processing to extract meaningful mechanical parameters. The following protocol outlines the essential steps for automated analysis of force volume datasets [8]:

1. Baseline Correction: Subtract the non-contact portion of the approach curve to establish a zero-force baseline, correcting for any laser drift or non-specific interactions [8].

2. Contact Point Detection: Implement robust algorithms to identify the precise point of tip-sample contact, a critical parameter for accurate indentation calculation. Change-point detection methods that identify transitions in slope or curvature have proven most effective for biological samples [8].

3. Indentation Calculation: Compute indentation depth (δ) as the difference between the piezo displacement after contact and the cantilever deflection: δ = (Zp - Zc) - (D - D0), where Zp is piezo position, Zc is contact point, D is deflection, and D0 is baseline deflection [5] [8].

4. Model Fitting: Fit appropriate contact mechanics models to the approach portion of the force curve to extract mechanical parameters. The Hertz model is most commonly applied for biofilm analysis:

[ F = \frac{4}{3} \cdot \frac{E}{1-\nu^2} \cdot \sqrt{R} \cdot \delta^{3/2} ]

Where F is force, E is Young's modulus, ν is Poisson's ratio (typically assumed 0.5 for incompressible biological materials), R is tip radius, and δ is indentation depth [5] [8].

5. Adhesion Analysis: Analyze retraction curves to quantify adhesion forces using Freely Jointed Chain (FJC) or Worm-Like Chain (WLC) models for polymer extension events, particularly when studying EPS components [8].

Spatial Mapping and Heterogeneity Analysis

Following mechanical parameter extraction from individual force curves, generate two-dimensional maps showing the spatial distribution of elasticity, adhesion, and other properties across the biofilm surface [6] [8]. Implement automated segmentation algorithms to identify regions with distinct mechanical signatures, correlating these domains with structural features observed through complementary microscopy techniques [6].

For large-area analysis, employ automated AFM systems with machine learning-assisted image stitching to create comprehensive mechanical maps spanning millimeter scales, enabling correlation between local mechanical properties and global biofilm architecture [6].

Diagram 2: Data Processing Pipeline for Mechanical Analysis

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Mechanobiology

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for AFM Biofilm Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Nitride AFM Probes | Nanomechanical probing of biofilm surfaces [4] [5] | Spherical tip geometry (2-5 μm diameter); spring constant: 0.01-0.5 N/m [4] [5] | Calibrate spring constant before use; ensure tip geometry matches modeling assumptions [4] |

| Poly-L-Lysine Coated Substrata | Enhanced bacterial immobilization for AFM imaging [5] | Molecular weight: 70,000-150,000; concentration: 0.01%-0.1% w/v [5] | Optimize concentration to maintain cell viability and native mechanical properties [5] |

| Defined Growth Media | Controlled biofilm cultivation for reproducible mechanical properties [1] [3] | Chemical composition affects EPS production and matrix mechanics [1] | Standardize carbon sources that influence biofilm architecture (e.g., glucose vs citrate) [1] |

| Calcium Chloride Supplements | Modulation of biofilm cohesion through ionic cross-linking [3] | Concentration range: 1-10 mM for cohesion studies [3] | Higher concentrations (10 mM) significantly increase cohesive energy [3] |

| Enzymatic Matrix Disruption Agents | Selective degradation of EPS components for mechanistic studies [1] | Glycoside hydrolases, DNases, proteases at specific activity units [1] | Use to dissect contribution of specific matrix components to mechanical properties [1] |

| Viability Staining Kits | Correlation of mechanical properties with metabolic activity [1] | LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kits [1] | Combine with AFM to identify persister cell niches based on mechanical signatures [1] |

Applications and Correlation with Antimicrobial Resistance

The mechanical mapping of biofilms provides critical insights into the mechanisms underlying antimicrobial resistance. Several key correlations have emerged from recent research:

Matrix Barrier Function and Antibiotic Penetration

Biofilms with higher elastic moduli and cohesive energies demonstrate significantly reduced antibiotic penetration rates. The dense EPS matrix acts as a diffusional barrier, binding to positively charged aminoglycosides and neutralizing their efficacy through molecular interactions with anionic components like eDNA [1]. Regions of increased stiffness within biofilms correlate with limited antibiotic diffusion and create niches where persister cells can survive antimicrobial challenge [1] [2].

Mechanical Heterogeneity and Treatment Failure

AFM elasticity mapping reveals substantial mechanical heterogeneity within single biofilms, with elastic moduli varying by orders of magnitude across micrometre scales [6] [5]. This mechanical heterogeneity creates differential susceptibility zones within the biofilm, where subpopulations experience varying degrees of antimicrobial exposure. Treatment strategies that fail to account for this mechanical complexity often eliminate only the most accessible cells while leaving resistant subpopulations intact [1] [7].

Targeted Matrix Disruption Strategies

Quantifying the mechanical contribution of specific EPS components enables rational design of matrix-disrupting adjuvants. Enzymatic degradation of matrix polymers using glycoside hydrolases or DNases significantly reduces biofilm cohesion and enhances antibiotic penetration [1] [7]. The efficacy of these treatments can be precisely monitored through changes in mechanical parameters measured by AFM, providing quantitative metrics for therapeutic development [1] [5].

Future Directions and Concluding Remarks

The integration of AFM force volume techniques with complementary analytical methods represents the future of biofilm mechanobiology research. Large-area automated AFM approaches now enable correlation of nanomechanical properties with macroscopic biofilm architecture, while machine learning algorithms facilitate rapid analysis of complex mechanical datasets [6]. The emerging field of CRISPR-nanoparticle hybrid systems offers potential for precisely targeting the genetic determinants of matrix production while simultaneously disrupting mechanical integrity through nanoparticle penetration [10].

Understanding the critical role of biofilm mechanical properties in antimicrobial resistance provides a foundation for developing novel therapeutic strategies that specifically target the physical integrity of biofilms. By combining mechanical mapping with molecular interventions, researchers can design multi-faceted approaches to combat biofilm-associated infections that remain intractable to conventional antibiotics. The protocols and applications outlined in this document provide a roadmap for integrating mechanical characterization into standard biofilm research, advancing both fundamental understanding and therapeutic innovation in this challenging field.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating microbial biofilms, providing unprecedented insights into their structural and mechanical properties. Unlike conventional microscopy techniques, AFM enables researchers to characterize surface topography, nanomechanical properties, and functional responses at the sub-cellular level without extensive sample preparation, and it can even be used under physiological conditions [6]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying biofilms—complex microbial communities held together by self-produced extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that play critical roles in various ecosystems while posing significant challenges in healthcare due to their resilience against antibiotics and disinfectants [6].

The transition from basic topographical imaging to advanced force spectroscopy represents a significant evolution in AFM capabilities for biofilm research. While traditional AFM imaging reveals surface morphology and cellular arrangements, force spectroscopy enables quantitative mapping of mechanical properties such as stiffness, adhesion, and viscoelasticity, which are crucial for understanding biofilm assembly, stability, and resistance mechanisms [6]. This technical advancement is especially relevant for investigating biofilm elasticity patterns, which correlate with functional heterogeneity and antimicrobial tolerance within these complex microbial communities.

Technical Foundations: AFM Operating Principles

Core Imaging and Spectroscopy Modes

AFM operates by scanning a sharp probe across a sample surface while measuring the forces between the probe and the sample, generating nanometer-scale topographical images and quantitative maps of nanomechanical properties [6]. The fundamental components include a microfabricated cantilever with a sharp tip, a piezoelectric scanner that positions the sample with high precision, and a detection system that monitors cantilever deflection. This configuration enables multiple operational modes essential for comprehensive biofilm characterization:

- Contact Mode: The tip maintains constant contact with the surface, providing high-resolution topographical data but potentially inducing sample deformation.

- Tapping Mode: The cantilever oscillates near its resonance frequency, minimizing lateral forces and reducing sample damage during imaging.

- Force Spectroscopy Mode: The tip approaches, contacts, and retracts from the surface at specific locations, generating force-distance curves that quantify mechanical properties and interaction forces.

The integration of these complementary approaches enables correlative analysis of structural features and mechanical properties within biofilm systems, revealing connections between spatial organization and functional heterogeneity at the microscale.

Advanced Property Mapping Capabilities

Beyond basic topography, modern AFM systems offer diverse characterization capabilities particularly relevant to biofilm research. When operated in liquids, AFM preserves the native state of microbial cells and can measure mechanical properties like stiffness, adhesion, and viscoelasticity [6]. These measurements can be extended to map electrical, magnetic, and thermal properties at the nanoscale, while specially equipped systems can perform chemical identification using patented photothermal AFM-based IR spectroscopy (AFM-IR) technology [11]. This multifunctional capability makes AFM particularly valuable for investigating the complex, heterogeneous nature of biofilms, where structural, mechanical, and chemical variations coexist across micron-length scales.

AFM Protocols for Biofilm Elasticity Mapping

Biofilm Preparation and Immobilization

Objective: To prepare reproducible biofilm samples suitable for AFM elasticity mapping while preserving native structural and mechanical properties.

Materials:

- Pantoea sp. YR343 (gram-negative bacterium from poplar rhizosphere) or target biofilm-forming strain [6]

- PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or appropriate substrate [6]

- Appropriate liquid growth medium (e.g., Lysogeny Broth for Pantoea sp.)

- Petri dishes or culture vessels

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for rinsing

Procedure:

- Surface Treatment: Prepare PFOTS-treated glass coverslips to create a hydrophobic surface that promotes bacterial attachment [6].

- Inoculation: Place treated coverslips in petri dishes and inoculate with Pantoea cells suspended in liquid growth medium.

- Biofilm Growth: Incubate at appropriate temperature (e.g., 28-30°C for Pantoea sp.) for selected time periods:

- Sample Harvesting: Gently remove coverslips from culture vessel and rinse with PBS to remove unattached cells.

- AFM Mounting: Securely mount prepared biofilm samples on AFM specimen disks using double-sided tape or appropriate mounting method.

Critical Considerations:

- Maintain hydration during transfer to prevent structural artifacts

- Minimize mechanical disturbance during rinsing to preserve delicate structures

- For live cell imaging, perform AFM in appropriate liquid medium

- For high-resolution imaging, air-drying may be employed as described in the Pantoea study [6]

Force Volume Acquisition for Elasticity Mapping

Objective: To acquire spatially-resolved mechanical property data across biofilm surfaces using force volume techniques.

Materials:

- Atomic Force Microscope with force volume capability

- Appropriate cantilevers (see Table 1)

- Calibration materials (e.g., clean glass substrate for spring constant calibration)

- Liquid cell if performing hydrated measurements

Procedure:

- Cantilever Selection and Calibration:

- Select appropriate cantilever based on required sensitivity and spatial resolution (see Research Reagent Solutions)

- calibrate cantilever spring constant using thermal tune or reference sample method

- Determine optical lever sensitivity by acquiring force curve on rigid reference surface

Experimental Parameter Optimization:

- Set force mapping grid dimensions (typically 16×16 to 64×64 points)

- Define maximum applied force (typically 0.5-5 nN to avoid sample damage)

- Set approach/retract velocity (typically 0.5-2 μm/s)

- Determine trigger threshold for surface detection

Data Acquisition:

- Approach sample surface and engage in imaging mode

- Select representative regions for elasticity mapping

- Initiate force volume acquisition sequence

- Monitor data quality and adjust parameters if necessary

- Acquire multiple maps across different biofilm regions

Data Validation:

- Verify approach and retract curves show minimal hysteresis

- Confirm consistent contact point detection

- Check for tip contamination by comparing approach/retract adhesion

Critical Considerations:

- Maintain constant environmental conditions (temperature, humidity)

- For hydrated biofilms, ensure complete immersion to prevent meniscus effects

- Limit measurement duration to minimize biological changes

- Include control measurements on bare substrate for reference

Data Processing and Analysis

Objective: To extract quantitative elasticity parameters from force volume data and generate spatial property maps.

Processing Workflow:

- Force Curve Preprocessing:

- Flatten baseline regions of force curves

- Correct for instrumental drift and offset

- Align contact points

Mechanical Model Fitting:

- Select appropriate contact mechanics model (e.g., Hertz, Sneddon, Johnson-Kendall-Roberts)

- Fit retract portion of force curves with selected model

- Extract Young's modulus (E) for each spatial location

Spatial Mapping and Statistical Analysis:

- Generate 2D elasticity maps from point-wise modulus values

- Calculate descriptive statistics for different biofilm regions

- Correlate elasticity with topological features from simultaneous height data

Validation Methods:

- Compare results from different contact models

- Verify consistency across multiple sample regions

- Validate against reference materials with known mechanical properties

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for AFM Biofilm Elasticity Studies

| Item | Specifications | Function |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Cantilevers | Silicon nitride, nominal spring constant 0.01-0.6 N/m, resonant frequency 5-70 kHz in liquid | Force sensing; softer cantilevers for delicate biological samples, stiffer for higher resolution |

| Biofilm Substrates | PFOTS-treated glass coverslips, silicon wafers, mica surfaces | Controlled surface properties for reproducible biofilm growth |

| Cell Culture Media | Lysogeny Broth or appropriate defined medium | Support microbial growth and biofilm development |

| Buffer Solutions | Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), Tris-HCl, HEPES | Maintain physiological conditions during liquid AFM measurements |

| Calibration References | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) standards, clean glass slides | Cantilever calibration and mechanical property validation |

| Surface Treatment | PFOTS [(heptadecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl)trichlorosilane] | Creates hydrophobic surfaces that promote bacterial attachment [6] |

Table 2: Key Parameters from AFM Biofilm Studies

| Parameter | Typical Values | Measurement Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Cell Dimensions | Length: ~2 μm, Diameter: ~1 μm, Surface area: ~2 μm² [6] | Baseline structural reference for Pantoea sp. YR343 |

| Flagellar Structures | Height: ~20-50 nm, Extension: tens of micrometers [6] | Appendage involvement in attachment and biofilm assembly |

| Young's Modulus Range | 0.1-100 kPa (highly dependent on biofilm age, species, and hydration) | Mechanical integrity and resistance to external stresses |

| Spatial Resolution | Topography: <1 nm, Force mapping: 10-100 nm (dependent on tip geometry) | Capability to resolve subcellular features and local property variations |

| Scanning Areas | Conventional AFM: <100 μm², Large-area AFM: millimeter-scale [6] | Representative sampling of heterogeneous biofilm architecture |

| Critical Contrast Ratios | Minimum 3:1 for graphical objects, 4.5:1 for text in visualizations [12] | Accessibility compliance for published data representations |

Visualizing AFM Workflows

Biofilm Preparation Protocol

Force Spectroscopy Measurement

Data Analysis Pipeline

Advanced Applications in Biofilm Research

Large-Area AFM and Automated Imaging

Recent advancements in AFM technology have addressed one of the technique's primary limitations: the restricted scanning area that hinders representative sampling of heterogeneous biofilms. Automated large-area AFM approaches now enable high-resolution imaging over millimeter-scale areas, providing comprehensive views of spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology during biofilm development [6]. This innovation is particularly valuable for capturing the inherent complexity of microbial communities, revealing organizational patterns like the distinctive honeycomb arrangement observed in Pantoea sp. YR343 biofilms [6].

The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence has transformed AFM operation and data analysis, with applications in four key areas: sample region selection, scanning process optimization, data analysis, and virtual AFM simulation [6]. ML algorithms enable automated segmentation, cell detection, and classification, efficiently processing the high-volume data generated by large-area scans. These developments facilitate continuous, multi-day experiments without human supervision and enhance the statistical significance of AFM measurements by enabling analysis of thousands of cells across representative biofilm areas [6].

Correlative Microscopy and Multi-modal Integration

The combination of AFM with complementary analytical techniques provides a more comprehensive understanding of biofilm systems. While AFM excels at surface topography and nanomechanical characterization, its integration with optical microscopy, confocal laser scanning microscopy, and spectroscopic methods enables correlative analysis of structural, mechanical, and chemical properties. This multi-modal approach is particularly powerful for investigating structure-function relationships in biofilms, connecting mechanical properties with metabolic activity or compositional variations.

For example, simultaneous AFM and fluorescence imaging can identify specific biofilm components (via fluorescent labels) while mapping their mechanical contributions, and AFM-IR spectroscopy can provide chemical identification of extracellular polymeric substances alongside stiffness measurements. These integrated approaches are advancing our understanding of how localized mechanical properties influence biofilm resilience, nutrient transport, and resistance mechanisms at the micro-scale.

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Experimental Challenges

Successful implementation of AFM force spectroscopy for biofilm elasticity mapping requires addressing several technical challenges:

- Tip Contamination: Biofilm components can adhere to AFM tips, altering their geometry and mechanical properties. Regular tip inspection and cleaning protocols are essential, along with monitoring force curves for signs of contamination.

- Sample Deformation: Excessive loading forces can compress or damage delicate biofilm structures, producing artifactual mechanical data. Progressive force testing should determine the minimum force required for reliable measurements.

- Environmental Stability: Thermal drift and environmental vibrations compromise spatial registration in long-duration experiments. Adequate equilibration time and vibration isolation are critical.

- Hydration Effects: Mechanical properties vary significantly between hydrated and dehydrated biofilms. Controlled liquid environments are essential for physiologically relevant measurements.

Data Interpretation Considerations

Accurate interpretation of AFM elasticity data requires careful consideration of several factors:

- Contact Model Selection: The Hertz model assumes linear elastic, isotropic materials with small deformations—conditions not fully met by viscoelastic, heterogeneous biofilms. Alternative models (Sneddon, JKR) may be more appropriate depending on indentation depth and adhesion characteristics.

- Spatial Heterogeneity: Local variations in EPS composition, cellular density, and hydration create mechanical heterogeneity that should be represented through sufficient spatial sampling.

- Rate-Dependent Effects: Biofilms exhibit viscoelastic responses where apparent stiffness depends on loading rate. Standardized approach velocities enable reproducible comparisons.

- Substrate Effects: Measurements on thin biofilms may include contributions from the underlying substrate. Appropriate biofilm thickness and controlled indentation depths minimize this effect.

The protocols and methodologies presented here provide a foundation for reliable AFM-based elasticity mapping of biofilms, enabling quantitative investigation of the mechanical heterogeneities that underlie biofilm resilience and functional properties.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a powerful scanning probe technique that has revolutionized the characterization of biological samples, providing nanoscale resolution of topographical and mechanical properties under physiological conditions [13]. The Force Volume (FV) technique is an advanced AFM mode that captures the spatial heterogeneity of mechanical properties by collecting an array of force-distance curves across a defined sample area [14] [15]. This method is particularly valuable for studying complex, heterogeneous biological systems such as bacterial biofilms, where mechanical properties vary considerably across different regions and structural components [16] [3].

Unlike single-point force measurements, Force Volume generates a complete mechanical map by performing indentation measurements at regular grid points, creating a "force volume" dataset where each pixel contains a full force-distance curve [14]. This capability is crucial for biofilm research, as it enables researchers to correlate mechanical properties with structural features, developmental stages, and compositional variations within these complex microbial communities [16] [5].

Theoretical Foundations

Basic Principles of Force-Distance Curves

The fundamental measurement in Force Volume AFM is the force-distance curve, which records the interaction forces between the AFM tip and sample surface as a function of piezoelectric actuator displacement [13]. Each force curve contains distinct regions reflecting different interaction regimes:

- Non-contact region: The tip and sample are separated with no significant interaction forces

- Jump-to-contact: Attractive forces may cause the tip to suddenly snap into contact with the surface

- Contact region: Repulsive forces dominate as the tip indents the sample

- Adhesion peak: Upon retraction, adhesive forces may cause the tip to stick to the surface before final separation [5] [13]

The deflection of the cantilever is measured using a laser beam reflected from the cantilever onto a position-sensitive photodetector, allowing precise force quantification with piconewton sensitivity [13].

Contact Mechanics Models

To extract quantitative mechanical properties from force-distance curves, several contact mechanics models can be applied. The most common for biological samples is the Hertz model, which describes the elastic deformation of two perfectly smooth, homogeneous bodies [5] [17]:

For a spherical indenter: [ F = \frac{4}{3}E^*R^{1/2}\delta^{3/2} ]

Where:

- (F) = applied force

- (E^*) = reduced Young's modulus

- (R) = tip radius

- (\delta) = indentation depth

The reduced modulus relates to the sample's Young's modulus ((E)) through: [ \frac{1}{E^*} = \frac{1-\nu{tip}^2}{E{tip}} + \frac{1-\nu{sample}^2}{E{sample}} ]

Where (\nu) is Poisson's ratio, typically assumed to be 0.5 for soft, incompressible biological samples [5] [17].

Table 1: Common Contact Mechanics Models for Biological Samples

| Model | Indenter Geometry | Application | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hertz | Parabolic/Spherical | Homogeneous, linear elastic materials | Assumes small deformations, infinite thickness |

| Sneddon | Conical/Pyramidal | Sharper indenters, larger deformations | Stress concentration at tip |

| Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) | Spherical | Strong adhesive contacts | Complex fitting procedure |

| Derjaguin-Muller-Toporov (DMT) | Spherical | Weak adhesive contacts, stiff materials | May underestimate adhesion |

For biofilms, which often exhibit viscoelastic behavior and significant adhesion, modified approaches such as the Oliver-Pharr method or Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) model may be more appropriate, particularly when substantial adhesive forces are present [5] [17].

Experimental Design and Setup

Instrumentation Requirements

A standard AFM system equipped for Force Volume measurements requires several key components:

- Piezoelectric scanner: Capable of precise XYZ positioning, typically with a Z-range ≥5-7μm for accommodating biofilm topography [3]

- Photodetector: Position-sensitive for measuring cantilever deflection

- Fluid cell: For imaging in physiological conditions

- Environmental control: Temperature and humidity regulation for maintaining biofilm viability [3] [13]

Modern bio-AFMs often integrate with optical microscopy systems, allowing correlation of mechanical properties with fluorescence markers or structural features [13].

Cantilever and Probe Selection

Appropriate cantilever selection is critical for accurate mechanical characterization of soft biological samples like biofilms:

Table 2: Cantilever Selection Guide for Biofilm Characterization

| Parameter | Recommended Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Spring Constant | 0.01-0.5 N/m | Soft enough to detect small forces without damaging samples |

| Tip Geometry | Spherical (2-10μm diameter) or pyramidal | Spherical tips reduce local stress and provide well-defined contact area |

| Tip Material | Silicon nitride | Biocompatible, suitable for liquid imaging |

| Resonance Frequency | 5-30 kHz in liquid | Optimized for operation in fluid environments |

| Cantilever Length | 100-200μm | Provides appropriate sensitivity |

Spherical probes are often preferred for biofilm mechanics as they minimize sample damage and provide a well-defined contact area for modulus calculation [15]. Cantilever spring constants must be calibrated before measurements, typically using thermal tuning or reference cantilever methods [13].

Step-by-Step Force Volume Protocol

Sample Preparation

Biofilm samples require careful preparation to maintain structural integrity and mechanical properties during AFM analysis:

- Substrate selection: Choose appropriate substrates such as glass coverslips, silicone sheets, or membrane filters that promote biofilm adhesion [3] [18]

- Hydration control: Maintain biofilms in hydrated conditions using fluid cells or humidity chambers (≥90% RH) to prevent artifacts from dehydration [3]

- Immobilization: For single-cell analysis within biofilms, consider gentle chemical fixation or mechanical confinement using porous membranes [5]

- Mounting: Secure sample firmly to prevent movement during scanning

System Configuration

- Cantilever installation: Mount selected cantilever and align laser detection system

- Approach: Engage tip with surface using minimal force setpoint to prevent sample damage

- Deflection sensitivity calibration: Perform on a rigid reference sample (e.g., silicon wafer) by measuring slope of force curve in contact region [14]

- Spring constant calibration: Determine using thermal noise method or reference cantilever [15]

Force Volume Acquisition Parameters

Configure scanning parameters to balance resolution, measurement quality, and acquisition time:

Table 3: Typical Force Volume Parameters for Biofilm Characterization

| Parameter | Recommended Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Scan Size | 5-100μm | Dependent on feature size and heterogeneity |

| Force per Line | 16-64 | Determines XY resolution of mechanical map |

| Samples per Line | 128-512 | Affects resolution of height image |

| Number of Samples | 32-128 points/curve | Sets Z-resolution of force curves |

| Ramp Size | 500-2000nm | Must exceed sample roughness and indentation depth |

| Ramp Rate | 0.5-4Hz | Lower rates reduce hydrodynamic effects in fluid |

| Trigger Mode | Relative | Compensates for drift, protects tip and sample |

| Setpoint | Minimal contact force | Typically 0.5-2nN for soft samples |

The total acquisition time for a Force Volume map can be calculated as: [ T_{acquisition} = \frac{(Samples\;per\;line) \times (Force\;per\;line)}{Ramp\;rate} ]

Higher resolution maps with more force curves require significantly longer acquisition times [14].

Data Acquisition Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete Force Volume experimental workflow:

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- Minimize scanning forces: Use the lowest possible setpoint that maintains contact to prevent sample damage [14]

- Reduce hydrodynamic effects: Lower ramp rates in fluid environments to minimize drag forces on the cantilever [14]

- Center Z-position: Ensure piezoelectric actuator is centered in Z-direction to accommodate surface topography [14]

- Check trigger settings: Use relative trigger mode to compensate for drift and protect the tip [14]

- Monitor data quality: Regularly inspect force curves for proper shape and adequate indentation depth

Data Analysis Pipeline

Force Curve Processing

Raw force-distance data requires several processing steps before mechanical properties can be extracted:

- Conversion to force-displacement: Transform raw photodetector voltage and scanner position to true force and tip-sample separation using sensitivity and spring constant values

- Baseline correction: Subtract non-contact portion of approach curve to establish zero force baseline

- Contact point determination: Identify point of initial tip-sample contact using automated algorithms or manual selection

- Indentation calculation: Subtract cantilever deflection from scanner movement to determine sample indentation: ( \delta = (z - z0) - d ), where (z) is scanner position, (z0) is contact point, and (d) is cantilever deflection [13]

Modulus Extraction and Mapping

- Model fitting: Apply appropriate contact mechanics model (e.g., Hertz, Sneddon) to the approach portion of the force curve

- Parameter optimization: Use least-squares fitting to determine Young's modulus that best fits the experimental indentation data

- Map generation: Create spatial maps of Young's modulus by assigning calculated values to corresponding XY positions

- Statistical analysis: Calculate descriptive statistics (mean, median, distribution) for the mapped region to quantify heterogeneity [15]

Handling Biological Heterogeneity

Biofilms exhibit significant spatial and temporal mechanical heterogeneity, requiring specialized analytical approaches:

- Log-normal transformation: Many biological mechanical property distributions follow log-normal rather than normal distributions [15]

- Outlier exclusion: Remove artifacts from dust contamination, surface defects, or invalid measurements

- Regional analysis: Segment maps based on structural features identified from topography or complementary microscopy

- Time-series analysis: For dynamic studies, track mechanical changes at equivalent positions over time

Applications in Biofilm Research

Mapping Biofilm Mechanical Heterogeneity

Force Volume technique has revealed substantial spatial variations in mechanical properties within biofilms. A study measuring cohesive energy in activated sludge biofilms found values ranging from 0.10 ± 0.07 nJ/μm³ at the surface to 2.05 ± 0.62 nJ/μm³ in deeper regions, demonstrating increasing cohesiveness with biofilm depth [3]. Similar heterogeneity has been observed in elastic modulus maps of mixed-culture biofilms, with variations of an order of magnitude across different microenvironments [16].

Investigating Matrix Composition Effects

The Force Volume technique enables correlation of mechanical properties with biofilm composition and environmental factors:

- Calcium effects: Biofilms grown with 10mM calcium showed increased cohesive energy (1.98 ± 0.34 nJ/μm³) compared to controls (0.10 ± 0.07 nJ/μm³) [3]

- EPS contribution: Regions rich in extracellular polymeric substances typically exhibit higher adhesion and different viscoelastic properties [16] [5]

- Cellular vs. matrix regions: Distinct mechanical signatures can differentiate cellular clusters from surrounding matrix material [6]

Monitoring Biofilm Development

Time-dependent Force Volume mapping can track mechanical changes during biofilm maturation:

- Early attachment: Initial surface colonization shows higher elasticity and lower adhesion

- Maturation: Developing biofilms exhibit increased stiffness and cohesiveness as matrix production accumulates

- Dispersion: Mechanical properties shift at onset of dispersal phase, often showing reduced cell-matrix adhesion [16] [18]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Force Volume Experiments

| Item | Specification | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cantilevers | Silicon nitride, spring constant: 0.01-0.5 N/m, spherical tips (2-10μm) | Force sensing and indentation | General biofilm mechanics [15] [13] |

| Calibration Samples | Rigid reference (silicon wafer), soft reference (PDMS gels) | System calibration and validation | Deflection sensitivity, spring constant [13] |

| Biofilm Substrates | Glass coverslips, membrane filters, silicone sheets | Biofilm growth support | Controlled adhesion surfaces [3] [18] |

| Immobilization Aids | Poly-L-lysine, porous membranes, PDMS microstructures | Sample stabilization during imaging | Single-cell analysis within biofilms [5] |

| Fluic Cells | Temperature-controlled, gas-permeable | Physiological environment maintenance | Live biofilm imaging in liquid [3] [13] |

| Culture Media | Chemically defined or complex growth media | Biofilm cultivation and maintenance | Specific nutritional environments [18] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Recent technological advancements are expanding Force Volume capabilities for biofilm research:

- Large-area automated AFM: Combining multiple scans to create millimeter-scale maps while maintaining nanometer resolution [6]

- Machine learning integration: Automated analysis of high-dimensional mechanical data for pattern recognition and classification [6]

- Multimodal correlation: Combining Force Volume with fluorescence microscopy, Raman spectroscopy, or other techniques to correlate mechanics with composition and metabolic activity [18]

- High-speed Force Volume: Improved temporal resolution for capturing dynamic processes in living biofilms [13]

These developments are enabling researchers to bridge the gap between nanoscale mechanical properties and macroscopic biofilm behavior, providing new insights into biofilm resilience, dispersal, and response to antimicrobial agents.

The Force Volume technique represents a powerful approach for quantifying the spatial mechanical heterogeneity of biofilms, offering unique insights into their structure-function relationships and response to environmental challenges. When properly implemented with appropriate controls and analytical methods, it provides invaluable data for understanding biofilm mechanics in biomedical, environmental, and industrial contexts.

The mechanical characterization of biofilms provides critical insights into their behavior, stability, and resistance to external forces. Two parameters are fundamental to understanding biofilm mechanics: the elastic modulus, which quantifies a material's stiffness and its resistance to deformation under stress and adhesion forces, which describe the strength of attachment between the biofilm and a substrate or within the biofilm matrix itself [19]. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool for quantifying these parameters at the nanoscale, enabling researchers to probe mechanical properties under physiological conditions [20] [5]. This application note details standardized protocols for AFM-based measurement of elastic modulus and adhesion forces in biofilms, supporting ongoing research in AFM force volume technique for biofilm elasticity mapping.

Quantitative Biomechanical Data in Biofilm Research

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent biofilm biomechanics research, providing reference values for experimental planning and data interpretation.

Table 1: Experimental Measurements of Biofilm Elastic Modulus

| Biofilm Type / Experimental Condition | Elastic Modulus (Approximate Range) | Measurement Technique | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa (Early biofilm) | Not Quantified | Microbead Force Spectroscopy | [20] |

| P. aeruginosa (Mature biofilm) | Instantaneous & delayed elastic moduli "drastically reduced" with maturation | Microbead Force Spectroscopy (Voigt Model) | [20] |

| Biofilm Streamers (P. aeruginosa PA14) | Differential Young's Modulus increases linearly with external stress | In-situ extensional rheology | [21] |

| General Biofilms | Viscous and elastic components characterized | Nanoindentation (Hertz Model) | [5] |

Table 2: Experimental Measurements of Biofilm Adhesion Forces

| Biofilm Type / Experimental Condition | Adhesion Force / Energy (Approximate Range) | Measurement Technique | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Culture (from activated sludge) | Cohesive Energy: 0.10 ± 0.07 nJ/µm³ to 2.05 ± 0.62 nJ/µm³ | AFM-based abrasion with friction measurement | [3] |

| Mixed Culture (with 10 mM Ca²⁺) | Cohesive Energy: 0.10 ± 0.07 nJ/µm³ to 1.98 ± 0.34 nJ/µm³ | AFM-based abrasion with friction measurement | [3] |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Early biofilm) | Adhesive Pressure: 34 ± 15 Pa | Microbead Force Spectroscopy | [20] |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Mature biofilm) | Adhesive Pressure: 19 ± 7 Pa | Microbead Force Spectroscopy | [20] |

| P. aeruginosa wapR mutant (Early biofilm) | Adhesive Pressure: 332 ± 47 Pa | Microbead Force Spectroscopy | [20] |

| P. aeruginosa wapR mutant (Mature biofilm) | Adhesive Pressure: 80 ± 22 Pa | Microbead Force Spectroscopy | [20] |

| S. aureus (on 58S BAG, 0-1s contact) | Adhesive Force: ~3 nN | AFM Force Spectroscopy | [22] |

| E. coli (on 58S BAG, 0-1s contact) | Adhesive Force: ~6 nN | AFM Force Spectroscopy | [22] |

| Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria (on mica) | Tip-Cell Interaction Force: -3.9 to -4.3 nN | AFM Force-Distance Curves | [23] |

| V. cholerae (Colony biofilm) | Interfacial Adhesive Energy: ~5 mJ/m² | Capillary Peeling Technique | [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for AFM-Based Nanoindentation and Elastic Modulus Measurement

This protocol details the procedure for determining the elastic modulus of a biofilm using AFM nanoindentation, based on the Hertz model of contact mechanics [24] [5].

Principle: The AFM cantilever acts as a soft nanoindenter. Force-distance curves are collected at multiple points on the biofilm surface. The elastic modulus is derived by fitting the retraction curve to a theoretical contact mechanics model, most commonly the Hertz model, which describes the elastic deformation of two homogeneous smooth bodies touching under load [24].

Pre-Experimental Preparations

Biofilm Cultivation:

- Grow biofilms on suitable substrates (e.g., glass coverslips, membrane filters) in relevant growth media under controlled conditions appropriate for the bacterial strain.

- For consistent results, standardize growth time, temperature, and nutrient availability. Note that mechanical properties change with biofilm maturation [20].

Sample Immobilization:

- Chemical Fixation: Securely attach the biofilm-substrate to the AFM sample disk using a double-sided adhesive tape or a thin layer of epoxy. For hydrated measurements, use a liquid cell.

- Hydration Control: For measurements in moist conditions, equilibrate the sample in a humidity chamber (e.g., ~90% relative humidity) for at least one hour prior to measurement to maintain consistent water content [3].

AFM Calibration:

- Cantilever Selection: Use soft, rectangular cantilevers with nominal spring constants of 0.01 - 0.08 N/m for biological samples to avoid excessive deformation [20].

- Spring Constant Calibration: Employ the thermal tune method to determine the exact spring constant (k) of the cantilever for each experiment [20].

- Tip Characterization: Determine the geometry and radius of the AFM tip, as this is a critical parameter in the Hertz model.

Step-by-Step Measurement Procedure

- Instrument Setup: Mount the calibrated cantilever and the immobilized sample in the AFM. Engage the tip in contact mode or force volume mode under the desired environmental condition (air or liquid).

- Topographical Imaging: First, obtain a low-resolution topographic image of the biofilm area of interest at a low applied load (~0 nN) to identify measurement locations [3].

- Force Volume Mapping: Define a grid over the region of interest. The AFM will automatically acquire force-distance curves at each point in the grid. Key parameters include:

- Trigger Point: Set to ensure sufficient indentation depth while avoiding damage to the biofilm or the tip.

- Approach/Retract Speed: A typical range is 0.5 - 1.0 µm/s to minimize viscous effects.

- Data Points: Acquire at least 512 data points per curve for adequate resolution.

- Data Acquisition: Collect a minimum of 50-100 force curves from different locations across multiple biofilm samples to account for spatial heterogeneity.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Curve Pre-processing: Level the baseline of the force curve and correct for the trigger point.

- Hertz Model Fitting: For each force curve, fit the indentation segment of the approach curve to the Hertz model. For a pyramidal tip, the model is often expressed as: ( F = \frac{2 \cdot \tan(\alpha)}{\pi} \cdot \frac{E}{1 - \nu^2} \cdot \delta^2 ) where ( F ) is the applied force, ( \alpha ) is the face angle of the tip, ( E ) is the elastic modulus, ( \nu ) is the Poisson's ratio (typically assumed to be 0.5 for biofilms), and ( \delta ) is the indentation depth [24] [5].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the mean, median, and standard deviation of the elastic modulus values obtained from all valid force curves. Present data as mean ± standard deviation.

Protocol for Quantifying Adhesion Forces via Microbead Force Spectroscopy

This protocol describes a standardized method for quantifying biofilm adhesion forces using Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS), which provides a defined contact geometry and high reproducibility [20].

Principle: A glass microbead attached to a tipless AFM cantilever is used as a probe. The bead is brought into contact with the biofilm surface and then retracted. The adhesion force is determined from the maximum pull-off force observed in the retraction force-distance curve.

Pre-Experimental Preparations

Probe Functionalization:

- Attach a 50 µm diameter glass microbead to a tipless silicon cantilever using a small amount of epoxy glue.

- Alternatively, for single-cell adhesion studies, a single bacterial cell can be attached to the cantilever to create a "cell probe" [5].

Biofilm Sample Preparation:

- Prepare biofilms as described in Section 3.1. For MBFS, a relatively flat and uniform biofilm surface is ideal.

Standardization of Conditions:

- To enable cross-experiment comparison, standardize the following parameters [20]:

- Loading Pressure: The force applied during the contact period.

- Contact Time: The duration the bead remains in contact with the biofilm (typically brief, e.g., 0-1 second [22]).

- Retraction Speed: The speed at which the bead is pulled away from the surface.

- To enable cross-experiment comparison, standardize the following parameters [20]:

Step-by-Step Measurement Procedure

- Instrument Setup: Mount the functionalized cantilever and the biofilm sample in the AFM. Use a closed-loop AFM system for accurate distance control.

- Approach and Contact: Position the bead above a selected location on the biofilm. Approach the surface at a constant velocity (e.g., 1 µm/s) until a predefined loading force or trigger point is reached.

- Dwell Period: Maintain the bead in contact with the biofilm for a standardized contact time (e.g., 250 ms to 1 second) to allow for bond formation [22].

- Retraction and Adhesion Measurement: Retract the cantilever at a constant speed (e.g., 1 µm/s) while recording the cantilever deflection. The adhesion force manifests as a negative peak (a "pull-off" event) in the retraction curve due to the cantilever bending downwards before detachment.

- Data Collection: Repeat steps 2-4 at a minimum of 50-100 different locations on the biofilm sample to obtain statistically significant data.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Force Curve Analysis: For each retraction curve, identify the minimum force value, which corresponds to the maximum adhesion force required to detach the probe from the biofilm.

- Adhesive Pressure Calculation (Optional): If the contact area between the microbead and the biofilm is known or can be estimated, the adhesion force can be normalized to this area to report an adhesive pressure in Pascals (Pa) [20].

- Binding Event Analysis: Analyze the retraction curve for multiple discrete "unbinding" events (sawtooth pattern), which can provide information on the number and strength of individual molecular bonds involved in adhesion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for AFM Biofilm Biomechanics

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tipless Cantilevers | Base for functionalized probes in adhesion studies. | CSC12/Tipless/No Al; used with microbeads for defined contact geometry [20]. |

| Glass Microbeads | Spherical probes for Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS). | ~50 µm diameter; provide quantifiable contact area for adhesion pressure calculation [20]. |

| Polyolefin Membrane | Substrate for growing biofilms in reactor systems. | Used in membrane-aerated biofilm reactors (MABR) for consistent biofilm cultivation [3]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Modifier of biofilm cohesive strength. | Addition of 10 mM Ca²⁺ during cultivation increases biofilm cohesiveness [3]. |

| Extracellular Nucleic Acids | Target for mechanistic studies of matrix mechanics. | DNase I/RNase A; used to degrade eDNA/eRNA to probe their structural role in streamers and biofilms [21]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Stamps | Cell immobilization for stable AFM imaging. | Microstructured stamps immobilize microbial cells without chemical fixation, preserving native properties [5]. |

| Modified Postgate's Medium C | Culture medium for specific bacterial strains. | Used for cultivating Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria (SRB) in adhesion studies [23]. |

The precise quantification of elastic modulus and adhesion forces is paramount for advancing our understanding of biofilm mechanics. The protocols and data summarized in this application note provide a framework for standardized, reproducible AFM measurements. Key findings indicate that biofilm mechanical properties are dynamic, influenced by factors such as maturation time [20], the presence of divalent cations like calcium [3], and the composition of the extracellular matrix, particularly extracellular DNA (eDNA) which can confer stress-hardening behavior [21]. Adhering to these detailed methodologies will enable researchers in drug development and related fields to generate robust, comparable data, ultimately accelerating the development of strategies to control or eradicate biofilms.

Linking EPS Matrix Composition to Macroscopic Mechanical Behavior

Microbial biofilms are complex, structured communities of microorganisms enclosed in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. This matrix, which can account for up to 90% of the biofilm's dry mass, is primarily responsible for the mechanical stability and functional integrity of the biofilm [25]. The EPS is a hydrated gel-like structure comprising a network of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, with a high water content typically ranging from 87% to 99% [26]. Understanding the relationship between the composition of this EPS matrix and the resulting macroscopic mechanical behavior is crucial for both controlling harmful biofilms and harnessing beneficial ones in industrial and medical applications.

The mechanical properties of biofilms represent a critical facet of their functionality, influencing their resistance to environmental stresses, detachment under fluid flow, and persistence against antimicrobial agents [25]. Biofilms exhibit viscoelastic behavior, meaning they combine both solid-like (elastic) and liquid-like (viscous) characteristics, enabling them to dissipate energy from external forces while maintaining structural cohesion [26] [25]. This property is fundamental to how biofilms withstand mechanical perturbations, spread to colonize new surfaces, or strengthen their existing structures. The cohesive strength of a biofilm, largely derived from the EPS matrix, is a primary factor affecting the balance between growth and detachment processes [3].

Advanced techniques like Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) have revolutionized our ability to probe these mechanical properties at the nanoscale, under physiological conditions, and without extensive sample preparation that could alter inherent biofilm characteristics [27] [6]. This application note details how AFM-based force volume techniques can be systematically employed to map biofilm elasticity and establish quantitative correlations between EPS composition and macroscopic mechanical behavior.

Theoretical Foundation: From Polymer Networks to Macroscopic Behavior

The mechanical behavior of the EPS matrix can be conceptually understood through continuum mechanics models developed for polymer networks. For biofilms formed by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains, whose major EPS carbohydrate component is alginate, the matrix can be modeled as a network of worm-like chains (WLCs) connected by transient junctions of specific lifetimes [26]. In this model, individual polysaccharide chains are characterized by their contour length (L), representing their fully extended length, and their persistence length (l_p), which indicates the typical length scale over which directional correlation along the chain is lost [26].

The force-extension relationship for a single WLC can be described by an interpolation formula that accounts for chain stiffness:

[ f(r) \approx \frac{kB\Theta}{lp} \left[ \frac{1}{4}\left(1 - \frac{r}{L}\right)^{-2} - \frac{1}{4} + \frac{r}{L} \right] ]

Where (k_B) is Boltzmann's constant, (\Theta) is the absolute temperature, and (r) is the end-to-end distance of the polymer chain [26]. This single-chain behavior can be upscaled to a three-dimensional network using approaches like the eight-chain model, which considers chains spanning from the center to the vertices of a cube, resulting in a strain energy function that describes the hyperelastic and viscoelastic response of the entire biofilm [26].

The diagram below illustrates the theoretical relationship between EPS composition and macroscopic mechanical properties:

Figure 1: Theoretical framework linking EPS composition to macroscopic mechanical properties through polymer network formation.

Experimental Protocols for AFM-Based Mechanical Characterization

Biofilm Cultivation and Sample Preparation

Protocol: Standardized Biofilm Growth for Mechanical Testing

Inoculum Preparation:

Substrate Coating:

Biofilm Growth:

- Incubate collagen-coated discs in BHI-plaque suspension under anaerobic conditions at 37°C [28] [29].

- Maintain with weekly fresh medium changes for maturity studies (e.g., 1-week vs. 3-week biofilms) [28].

- For defined chemical manipulation, incorporate specific ions (e.g., 10 mM CaCl₂) during cultivation to examine their effect on cohesive strength [3].

Sample Preparation for AFM:

- Gently rinse biofilm samples with 0.85% physiological saline for 1 minute to remove unattached cells [28].

- For hydrated imaging, mount samples in liquid cells with appropriate growth medium or buffer [6].

- For controlled humidity imaging, equilibrate samples in ~90% humidity for 1 hour before AFM analysis [3].

AFM Force Volume Technique for Elasticity Mapping

Protocol: Nanomechanical Mapping via Force Volume AFM

Cantilever Selection and Calibration:

- Select appropriate cantilevers based on biofilm stiffness: use softer cantilevers (spring constant ~0.01-0.1 N/m) for compliant biofilms and stiffer cantilevers (~0.5-1 N/m) for rigid biofilms [27] [3].

- Precisely calibrate the spring constant using thermal tuning or reference cantilever methods [27].

- Determine the optical lever sensitivity by acquiring force curves on a rigid reference sample (e.g., clean silicon wafer) [27].

AFM Operation Modes Selection:

- Utilize contact mode for high-resolution topographical imaging of rigid biofilm regions [27] [30].

- Employ tapping mode for delicate, loosely attached biofilms to minimize lateral forces that could damage the sample [30].

- Implement force volume mode for elasticity mapping: acquire arrays of force-distance curves (typically 16×16 to 128×128) across the biofilm surface [27].

Data Acquisition Parameters:

- Set appropriate loading rates (typically 0.5-2 Hz approach/retract rate) to capture viscoelastic responses [27].

- Apply constant loads in the range of 0.5-10 nN to remain in the linear elastic regime while ensuring sufficient indentation depth [3].

- Set maximum indentation depth to 10-15% of biofilm thickness to avoid substrate effects [27].

Mechanical Property Extraction:

- Fit the approach portion of force curves with appropriate contact mechanics models (e.g., Hertz, Sneddon, or Johnson-Kendall-Roberts models) to derive Young's modulus values [27].

- Calculate adhesion energy from the retraction curve hysteresis [28] [3].

- Generate spatial elasticity maps by assigning Young's modulus values to each force curve location in the array [27].

The experimental workflow for AFM-based mechanical characterization is summarized below:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for AFM-based mechanical characterization of biofilms.

Cohesive Energy Measurement via AFM Abrasion

Protocol: Quantifying Biofilm Cohesive Strength

Baseline Topographical Imaging:

Controlled Abrasion Phase:

Post-Abrasion Imaging:

Cohesive Energy Calculation:

- Subtract consecutive height images to determine the volume of displaced biofilm material [3].

- Calculate frictional energy dissipated during abrasion from friction force data and scan parameters [3].

- Compute cohesive energy as the ratio of frictional energy dissipated to the volume of biofilm displaced (nJ/μm³) [3].

Quantitative Data on EPS-Mechanics Relationships

Maturation-Dependent Mechanical Properties

Table 1: Evolution of EPS and Mechanical Properties During Oral Biofilm Maturation

| Parameter | 1-Week Biofilm (Young) | 3-Week Biofilm (Mature) | Measurement Technique | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live Bacteria Volume | Baseline | Significantly Higher | CLSM with SYTO 9 staining | P < 0.01 [28] |

| EPS Matrix Volume | Baseline | Significantly Higher | CLSM with Alexa Fluor 647-dextran | P < 0.01 [28] |

| Surface Roughness | Higher | Significantly Lower | AFM Topography | P < 0.01 [28] |

| Cell-Surface Adhesion Force | Fairly Constant | Fairly Constant | AFM Force-Distance | Not Significant [28] |

| Cell-Cell Adhesion Force | Lower | Significantly Higher | AFM Force-Distance | P < 0.01 [28] |

Environmental Influence on Mechanical Properties

Table 2: Impact of Environmental Factors on Biofilm Mechanical Properties

| Factor | Effect on Mechanical Properties | Magnitude of Change | Proposed Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Ions (10 mM) | Increased cohesive energy | From 0.10 ± 0.07 to 1.98 ± 0.34 nJ/μm³ | Enhanced ionic cross-linking between polymer chains | [3] |

| Maturation (1 to 3 weeks) | Increased cell-cell adhesion | Significantly more attractive | Enhanced EPS production and cell interconnection | [28] |

| Shear Stress | Altered biofilm structure and exopolysaccharide production | Strain-dependent | Bacterial mechanosensing and response | [25] |

| Antibiotic Treatment | Modified mechanical response | Treatment-dependent | Matrix degradation or cellular lysis | [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Mechanics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyapatite Discs | Mimics tooth/enamel surface for oral biofilms | 0.38-inch diameter, 0.06-inch thickness | Collagen coating enhances bacterial attachment [28] |

| Type I Collagen | Surface coating for improved biofilm adhesion | Bovine dermal, 10 mg/mL in 0.012 N HCl | Creates more uniform biofilm growth surface [28] |

| Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) Broth | Nutrient medium for biofilm growth | Standard formulation | Supports diverse microbial community growth [28] |

| Alexa Fluor 647-dextran | EPS matrix fluorescent labeling | 10 kDa molecular weight | Incorporated during biofilm formation for visualization [28] |

| SYTO 9 green-fluorescent stain | Live bacteria labeling | Nucleic acid stain | Enables viability assessment and volume quantification [28] |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Ionic cross-linking enhancement | 10 mM concentration in medium | Significantly increases cohesive energy [3] |

| Silicon Nitride AFM Cantilevers | Nanomechanical probing | Spring constant: 0.01-1 N/m | Proper spring constant calibration critical [27] [3] |

| Polyolefin Membrane | Biofilm growth substrate | 0.1-μm mean pore diameter, 34% porosity | Used in membrane-aerated biofilm reactors [3] |

Applications in Drug Development and Beyond

The quantitative relationship between EPS composition and mechanical properties has significant implications for pharmaceutical development and therapeutic strategies. Mechanical properties can serve as biomarkers of biofilm-related infection progression and treatment efficacy [25]. When biofilms are treated with antimicrobial agents, changes in their mechanical response provide insights into the compound's mechanism of action—whether it primarily kills bacteria, disrupts matrix cohesion, or both [25]. This approach enables high-throughput screening of anti-biofilm compounds by quantifying mechanical parameters before and after treatment [25].

The viscoelastic character of biofilms plays a crucial role in clinically relevant phenomena such as the formation of streamers—flexible three-dimensional filaments that cause clogging in medical devices [25]. Understanding how EPS composition influences viscoelasticity enables the development of combined chemical-mechanical strategies where chemical treatments reduce biofilm cohesiveness, thereby decreasing the force required for mechanical removal [25]. Furthermore, the ability to measure interaction forces between specific biomolecules using AFM techniques like Molecular Recognition Force Microscopy (MRFM) provides opportunities for investigating ligand-receptor interactions relevant to biofilm formation and stability [27].

Advanced AFM applications now allow for the large-area automated imaging of biofilm communities over millimeter-scale areas, overcoming traditional limitations of small imaging areas and enabling correlation of nanoscale mechanical properties with macroscopic biofilm architecture [6]. When combined with machine learning approaches for image analysis, these techniques provide unprecedented capability to map the spatial heterogeneity of mechanical properties throughout mature biofilm structures [6]. This comprehensive mechanical profiling is essential for developing targeted interventions against harmful biofilms while promoting the stability of beneficial biofilms in industrial and environmental applications.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for AFM Force Volume on Biofilms

Within the broader context of research employing Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) force volume technique for biofilm elasticity mapping, the critical first step is the effective immobilization of hydrated, live biofilms. Successful nanomechanical characterization via AFM force spectroscopy hinges on sample preparation methods that preserve the native structure and mechanical properties of the biofilm. AFM is a powerful tool for generating high-spatial-resolution maps of nanomechanical attributes like elasticity under physiological conditions [31]. However, acquiring meaningful force-distance (f-d) curves using the force volume technique requires biofilms to be securely immobilized without altering their delicate extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix or mechanical integrity [32]. This application note details standardized protocols for preparing and immobilizing hydrated biofilms to ensure reliable and reproducible AFM elasticity measurements.

Surface Selection and Functionalization

The substrate onto which a biofilm is grown is a primary factor controlling its immobilization during AFM analysis. The surface must provide sufficient adhesion to prevent detachment under the force of the AFM tip while being compatible with both biofilm growth and the AFM measurement itself.

Table 1: Common Substrates for Biofilm Immobilization in AFM Studies

| Substrate Material | Functionalization/Treatment | Key Characteristics | Compatibility with AFM Elasticity Mapping |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass [6] | PFOTS (Perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) treatment | Creates a hydrophobic surface; promotes specific cellular orientation and honeycomb pattern formation [6]. | Excellent for high-resolution topographical and mechanical mapping of initial attachment. |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAP) [33] | Fabricated into discs from <75 µm particle size HAP. | Mimics mineralized tooth surfaces; ideal for oral biofilm studies [33]. | Suitable for force-volume imaging under physiological fluid (PBS). |

| Silicon [6] | Various chemical modifications (e.g., PFOTS). | Allows for significant reduction in bacterial density via surface modification [6]. | Ideal for combinatorial studies on how surface properties influence attachment and mechanics. |

| Titanium [34] | Often used as discs in static models. | Relevant for studying biofilms on medical implants. | Compatible with AFM; requires secure mounting in the fluid cell. |

Biofilm Growth and Immobilization Protocols

Static Growth on Functionalized Surfaces

This protocol is ideal for growing biofilms directly on AFM-compatible substrates, ensuring firm attachment from the initial stages of colonization.

Detailed Protocol:

- Surface Preparation: Place sterilized substrates (e.g., PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or HAP discs) horizontally in a multi-well plate [6] [33].

- Inoculation: Inoculate the well with the bacterial strain of interest (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343, Escherichia coli) in an appropriate liquid growth medium [6] [32].

- Incubation: Incubate at the optimal temperature for the strain (e.g., 37°C for many human pathogens) for the desired attachment period. For early attachment studies, this can be as brief as 30 minutes [6].

- Rinsing: After incubation, gently rinse the substrate with a sterile buffer (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline - PBS) to remove non-adherent planktonic cells. This step is critical to leave only the firmly attached cells for AFM analysis [6].

- Hydration Maintenance: Transfer the substrate to the AFM fluid cell and keep it submerged in PBS or growth medium throughout the measurement to maintain hydration [33].

Dynamic Growth and Transfer

For biofilms grown under flow conditions (e.g., in flow cells or bioreactors) that more closely mimic natural environments, a transfer protocol is required.

Detailed Protocol:

- Biofilm Growth: Grow biofilms under dynamic conditions in a flow cell system or constant flow chamber to achieve mature, 3D structures [34].

- Sample Extraction: Carefully extract a section of the colonized surface or a representative fragment of the biofilm.

- Immobilization in a Cell Culture Insert: Place the biofilm sample on a sterile membrane (e.g., polycarbonate) within a cell culture insert. This setup allows for nutrient exchange from below while providing a stable, flat surface for AFM indentation from above.

- Gentle Rinsing: Rinse with buffer to remove loosely attached cells, taking care not to disrupt the biofilm architecture.

- AFM Mounting: Securely mount the entire culture insert into the AFM fluid cell and submerge in buffer for measurement.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points and steps for selecting and executing these protocols:

Chemical Fixation for Structural Preservation

For certain experiments where high-resolution topography is the priority, or where the viability of cells during scanning is not a concern, chemical fixation provides excellent structural preservation.

Detailed Protocol:

- Growth and Rinsing: Grow and rinse the biofilm on the chosen substrate using the static method described in section 3.1.

- Fixation: Immerse the sample in a buffered paraformaldehyde solution (commonly 2-4%) for a defined period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) at room temperature. This crosslinks proteins and stabilizes the structure [35].

- Salt Removal: Rinse the fixed sample with deionized water or a volatile buffer like ammonium acetate to remove crystallizable salts [35].

- Dehydration (Optional): For AFM imaging in air, dehydrate the sample through a graded series of ethanol or acetone [35].

- Drying (Optional): Air-dry the sample in a desiccator or under a gentle stream of inert gas [35].

Note: Fixation and dehydration can significantly alter the native mechanical properties of the biofilm. This protocol is not recommended for studies aiming to measure the true in vivo elasticity of the biofilm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Immobilization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Immobilization Protocol | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS (Perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) [6] | Surface functionalization to create a hydrophobic surface that promotes specific bacterial attachment and orientation. | Used to treat glass coverslips for studying early biofilm assembly patterns [6]. |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAP) Discs [33] | Provides a clinically relevant substrate that mimics tooth enamel for growing oral biofilms. | Serves as the growth substrate for microcosm biofilms in studies of dental plaque mechanics [33]. |

| Paraformaldehyde [35] | Cross-linking fixative agent that preserves the 3D structure of biofilms and individual cells. | Used in a step-by-step preparation protocol for stabilizing cell morphology prior to analysis [35]. |