Nanoparticle-Enhanced CRISPR Delivery: Strategies for Stabilizing Gene Editing in Biofilm Microenvironments

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative strategies to enhance the stability and efficacy of CRISPR constructs within challenging biofilm microenvironments.

Nanoparticle-Enhanced CRISPR Delivery: Strategies for Stabilizing Gene Editing in Biofilm Microenvironments

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative strategies to enhance the stability and efficacy of CRISPR constructs within challenging biofilm microenvironments. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental barriers biofilms pose to conventional gene editing, details advanced nanoparticle-based delivery systems that protect and transport CRISPR cargo, and offers practical optimization and troubleshooting guidance. The content further covers critical validation techniques for assessing editing efficiency and off-target effects, synthesizing key takeaways to outline a clear path for translating these advanced antimicrobial therapies into clinical practice.

Understanding the Battlefield: Why Biofilm Microenvironments Compromise CRISPR Stability and Efficacy

The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix is a self-produced, highly hydrated network that encapsulates biofilm cells, forming a protective "house" or "fortress" [1]. This matrix is not merely a physical scaffold; it is a complex, dynamic, and functionally active component that determines the immediate conditions of life for biofilm microorganisms [1]. The EPS presents a formidable multi-faceted barrier to conventional antimicrobials and, as emerging research shows, to novel therapeutic strategies like CRISPR/Cas9 delivery.

The composition of the EPS is surprisingly diverse. Contrary to common belief, it consists of more than just polysaccharides. The matrix comprises a wide variety of proteins, glycoproteins, glycolipids, and significant amounts of extracellular DNA (e-DNA) [1]. In many environmental biofilms, polysaccharides can even be a minor component [1]. This biochemical complexity creates a dense, negatively charged sieve that severely limits the penetration and efficacy of CRISPR-based therapeutics.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What specific components of the EPS matrix are the primary culprits in hindering CRISPR delivery?

The EPS matrix employs multiple components to create a barrier:

- Physical Sieve: The dense, cross-linked network of polysaccharides and proteins creates a porous structure that physically blocks the diffusion of large CRISPR/Cas9 complexes (which often exceed 10 nm in size) [2].

- Charge Interactions: The abundance of negatively charged polymers, such as alginate in P. aeruginosa biofilms, can electrostatically bind to and sequester positively charged nanocarriers, preventing them from reaching their target cells [1] [2].

- Enzymatic Degradation: The matrix retains extracellular enzymes, including nucleases, which can degrade the guide RNA (gRNA) and the plasmid DNA encoding the CRISPR system before it can enter bacterial cells [1] [3].

- Matrix Trapping: e-DNA, which forms distinct grid-like structures and filamentous networks within the biofilm, can actively bind to CRISPR components, further reducing delivery efficiency [1].

FAQ 2: How does the biofilm microenvironment reduce the stability of CRISPR/Cas9 constructs?

Once inside the biofilm, the CRISPR/Cas9 system faces a hostile microenvironment:

- Altered Metabolic States: Biofilms contain gradients of nutrients, oxygen, and waste products. Subpopulations of bacteria, especially persister cells in the inner layers, enter a dormant, slow-growing state [2] [4]. Since CRISPR delivery often relies on active bacterial processes for cellular uptake and expression, these metabolic differences drastically reduce editing efficiency.

- Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) Hotspot: While biofilms facilitate HGT, allowing the spread of antibiotic resistance genes, this same property can be a hurdle. Delivered CRISPR plasmids may be transferred to non-target species, posing a risk of off-target effects and reducing the concentration available for the intended pathogenic targets [1] [4].

FAQ 3: Are certain types of biofilms more challenging for CRISPR delivery than others?

Yes, the resistance and barrier properties can vary significantly:

- Species-Specific Composition: Biofilms formed by different bacterial species have unique EPS compositions. For instance, P. aeruginosa biofilms may be rich in alginate and e-DNA, while E. coli and S. aureus biofilms rely heavily on curli fibers and proteinaceous components, respectively [1]. This requires a tailored approach to nanoparticle design for different pathogens.

- Environmental vs. Clinical Isolates: The EPS of biofilms from natural environments can be structurally and compositionally distinct from those studied in laboratory models, often being more complex and resistant [1]. Extrapolating results from model organisms like P. aeruginosa to all biofilms is not suitable and requires validation across diverse species [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common CRISPR Delivery Failures in Biofilms

The following table outlines frequent experimental issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem Phenotype | Potential Root Cause | Proposed Solution & Experimental Adjustments |

|---|---|---|

| Low Editing Efficiency | - CRISPR constructs degraded by matrix nucleases.- Nanoparticles trapped in EPS.- Target cells are dormant persisters. | - Encapsulate CRISPR components in nuclease-resistant lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [2].- Use protease-resistant Cas9 variants.- Pre-treat with EDTA to chelate cations and disrupt matrix integrity [1]. |

| Poor Nanoparticle Penetration | - Large nanoparticle (NP) size.- Strong electrostatic adhesion to EPS. | - Optimize NP size <100 nm and use PEGylation to reduce biofouling [2].- Employ enzyme-functionalized NPs (e.g., with DNase I to degrade e-DNA or proteinase K to digest proteins) [2] [3]. |

| Lack of Target Specificity | - Off-target editing in non-pathogenic species.- Conjugative transfer of CRISPR plasmid. | - Utilize phage-derived delivery systems or conjugative plasmids with narrow host ranges [5] [3].- Employ CRISPRi (dCas9) for reversible gene knockdown instead of permanent cleavage. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Species | - Differences in EPS composition and matrix structure. | - Characterize the EPS of your target biofilm (e.g., using lectin staining for polysaccharides, e-DNA quantification) [1].- Customize gRNA to target essential biofilm genes (e.g., pelA, pslG in Pseudomonas; ica operon in Staphylococcus) [4] [3]. |

Quantitative Data: Nanoparticle Performance Against Biofilm Barriers

Research has quantified the efficacy of various nanoparticle systems in overcoming EPS barriers. The data below summarizes key findings from recent studies.

Table: Efficacy of Nanoparticle-Mediated CRISPR Delivery Against Biofilms

| Nanoparticle Type | Target Biofilm | Key Outcome Metric | Result | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomal Cas9 | P. aeruginosa | Reduction in biofilm biomass | >90% reduction in vitro | [2] |

| Gold Nanoparticle-CRISPR | P. aeruginosa | Gene-editing efficiency | 3.5-fold increase vs. non-carrier systems | [2] |

| CRISPR-Engineered Bacteriophage (crPhage) | E. coli | Clinical trial phase (UTI treatment) | Phase 1b trial completed | [5] |

| Cationic Polymer Nanoparticles | Multi-species food biofilm | Log reduction of pathogens | Up to ~3-log target reduction | [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Investigating CRISPR-Biofilm Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Research | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescently Labeled Lectins | To visualize and characterize polysaccharide components in the EPS matrix in situ [1]. | Crucial for understanding the physical barrier before designing delivery systems. |

| DNase I (e.g., Pulmozyme) | To degrade e-DNA, a key structural component in many biofilms (e.g., P. aeruginosa, S. aureus) [1]. | Can be used as a pre-treatment or co-delivered with NPs to enhance penetration. |

| Cation-Chelating Agents (EDTA) | Disrupts ionic cross-linking (e.g., by Ca2+ ions) that provides mechanical stability to the EPS [1]. | Useful for pre-treatment to loosen the matrix structure. |

| Nuclease-Resistant gRNA (chemically modified) | Increases the half-life of gRNA in the nuclease-rich biofilm microenvironment [2] [3]. | Modifications like 2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro improve stability and editing outcomes. |

| dCas9 (CRISPRi/a systems) | Enables temporary gene knockdown (interference) or activation without double-strand breaks [3]. | Redders ethical and safety concerns and allows study of essential genes. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Assessing CRISPR Construct Penetration through EPS

Aim: To visualize and quantify the diffusion of CRISPR-carrying nanoparticles into a mature biofilm.

- Biofilm Growth: Grow a standardized biofilm (e.g., P. aeruginosa or S. aureus) in a flow cell or on a coverslip for 48-72 hours.

- NP Preparation: Synthesize nanoparticles (e.g., ~50 nm gold or polymeric NPs) loaded with a fluorescently labeled, non-functional CRISPR plasmid (e.g., Cy5-dye labeled).

- Application: Apply the fluorescent NPs to the mature biofilm and incubate for a defined period (e.g., 1-4 hours).

- Imaging & Analysis: Use Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) to take Z-stack images through the biofilm depth. Quantify fluorescence intensity as a function of depth using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to generate a penetration profile [2] [4].

Protocol 2: Evaluating gRNA Stability in Biofilm Conditioning

Aim: To determine the degradation kinetics of gRNA when exposed to the biofilm matrix.

- Matrix Extraction: Harvest a mature biofilm via gentle scraping and centrifugation. Filter the supernatant to remove cells, obtaining a cell-free EPS extract [1].

- Incubation Setup: Incubate your gRNA (both naked and nanoparticle-encapsulated) with the EPS extract at 37°C.

- Sampling: Withdraw aliquots at various time points (0, 15, 30, 60, 120 min).

- Analysis: Run samples on an agarose gel to visualize gRNA integrity. Compare the band intensity of full-length gRNA over time to calculate its half-life in the biofilm environment [3].

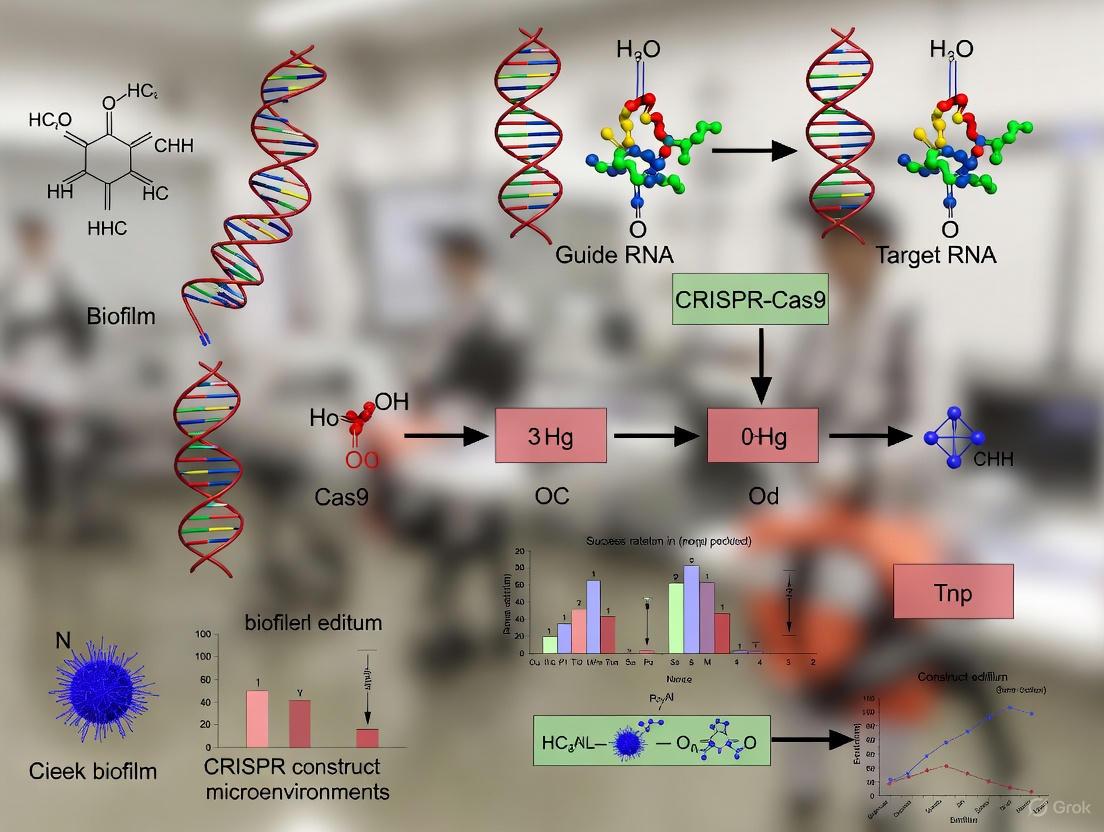

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the multi-layered defense mechanisms of the biofilm EPS matrix against CRISPR-Cas9 delivery systems.

This workflow outlines a systematic experimental approach to develop and validate EPS-penetrating CRISPR delivery systems.

For researchers developing CRISPR-based antimicrobials, the biofilm microenvironment presents a formidable delivery challenge. The very factors that confer protection to bacterial cells—the dense extracellular matrix, physiological heterogeneity, and nutrient gradients—create a "hostile territory" that severely limits the access and activity of CRISPR-Cas systems [2] [4]. This technical support article provides targeted guidance for scientists navigating these obstacles, offering troubleshooting advice, detailed protocols, and reagent solutions to advance your research on improving CRISPR construct stability within biofilms.

# Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary physiological barriers to CRISPR delivery in biofilms? The main barriers stem from the biofilm's structure and the physiological state of its resident cells. The dense extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix physically impedes the penetration of CRISPR constructs [2] [6]. More critically, the heterogeneous microenvironments within biofilms lead to gradients of nutrient availability, oxygen, and waste products [2] [6]. This results in subpopulations of bacteria, particularly those in inner layers, entering a state of reduced metabolic activity or dormancy (persister cells) [2] [4]. Since many CRISPR delivery mechanisms rely on active bacterial processes for uptake and expression, these dormant, slow-growing cells are largely refractory to genetic editing [2].

2. Which nanoparticle properties are most critical for enhancing CRISPR delivery against biofilms? Nanoparticles must be engineered to overcome multiple barriers simultaneously. Key properties include:

- Small size and positive surface charge: To facilitate penetration through the negatively charged EPS matrix and interaction with bacterial cell membranes [2].

- Controlled release capability: To ensure CRISPR payload protection during transit and sustained release within the biofilm [2] [7].

- Intrinsic biofilm-disrupting activity: Some metallic nanoparticles, like gold, can weaken the EPS matrix while serving as delivery vehicles [2].

- Co-delivery capacity: The ability to carry additional agents, such as antibiotics or quorum-sensing inhibitors, for synergistic effects [2] [7].

3. How can I assess and account for metabolic heterogeneity in my biofilm models? Utilize a combination of vital staining and advanced microscopy. Fluorescent dyes that indicate metabolic activity (e.g., CTC for respiratory activity) or membrane integrity can be used in conjunction with confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) to visualize the spatial distribution of active versus dormant cells within the biofilm architecture [2] [6]. Furthermore, designing CRISPR systems that target essential genes or utilize promoters active under low-nutrient conditions can help broaden efficacy across different physiological states [4].

# Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common Experimental Challenges and Proposed Solutions

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low CRISPR editing efficiency in mature biofilms | Poor penetration of CRISPR constructs through EPS High proportion of metabolically inactive persister cells | Utilize nanoparticle carriers (e.g., liposomal, gold NPs) Pre-treat with EPS-disrupting enzymes (e.g., DNase, dispersin B) Target quorum-sensing genes to disrupt biofilm integrity | [2] [4] [7] |

| High variability in results between biofilm replicates | Inconsistent biofilm growth conditions Heterogeneous biofilm architecture | Standardize growth media, flow rates (in flow cells), and inoculation methods Use multiple biofilm models (e.g., static, flow cell) for validation Increase sample size and randomize sampling points | [6] |

| Lack of observed synergistic effect with antibiotics | Incorrect timing of antibiotic administration CRISPR not effectively sensitizing bacteria | Ensure CRISPR system successfully knocks out resistance genes before antibiotic challenge Use nanoparticles designed for co-delivery of CRISPR and antibiotics | [2] [7] |

| Cytotoxicity of nanoparticle delivery system | Material-specific toxicity (e.g., certain cationic polymers) | Optimize nanoparticle composition and surface chemistry Test lower concentrations or switch to more biocompatible materials (e.g., lipid-based NPs) | [2] |

Table 2: Efficacy of Nanoparticle-Enhanced CRISPR Strategies Against Biofilms

| Delivery Platform | Target Bacteria / Biofilm | Key Outcome | Efficiency / Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomal Cas9/gRNA formulation | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Reduction in biofilm biomass | >90% reduction in vitro [2] |

| Gold nanoparticle carriers | Model bacterial systems | Enhancement in gene-editing efficiency | 3.5-fold increase compared to non-carrier systems [2] [7] |

| CRISPR-NP hybrid system + Antibiotic | Antibiotic-resistant biofilm | Synergistic biofilm disruption and bacterial killing | Superior to either treatment alone [2] [7] |

# Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing CRISPR/nanoparticle penetration in biofilms

Objective: To visualize and quantify the distribution and penetration efficiency of nanoparticle-based CRISPR delivery systems within a mature biofilm.

Materials:

- Mature bacterial biofilm (e.g., 48-72 hour culture)

- Fluorescently labeled CRISPR-Cas9/nanoparticle complex

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM)

- Suitable staining dyes (e.g., SYTO for total cells)

Method:

- Biofilm Growth: Grow biofilms under optimized, standardized conditions on a surface compatible with CLSM (e.g., glass-bottom dish) [6].

- Treatment: Apply the fluorescently labeled CRISPR/nanoparticle complex to the mature biofilm and incubate for a predetermined time.

- Staining and Washing: Gently wash the biofilm with buffer to remove non-adherent complexes. Counterstain the biofilm biomass to distinguish bacterial cells.

- Imaging: Use CLSM to capture Z-stack images through the entire biofilm depth.

- Analysis: Analyze image stacks with software (e.g., ImageJ) to determine the fluorescence intensity of the CRISPR signal as a function of biofilm depth. This quantifies penetration and identifies diffusion barriers.

Protocol 2: Evaluating metabolic state-dependent CRISPR efficacy

Objective: To correlate the success of CRISPR-mediated gene editing with the metabolic activity of cells within a biofilm.

Materials:

- Mature bacterial biofilm

- CRISPR-Cas9 system targeting a reporter or resistance gene

- Metabolic activity stain (e.g., 5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride - CTC)

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

- Viability plating media

Method:

- Biofilm Treatment: Treat the biofilm with the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

- Dissociation and Staining: Gently disaggregate the biofilm to create a cell suspension. Stain the cells with CTC, which is reduced to a fluorescent formazan by metabolically active bacteria.

- Cell Sorting: Use FACS to sort the population into high-CTC (metabolically active) and low-CTC (less active/dormant) subpopulations.

- Plating and Analysis: Plate each sorted subpopulation on selective and non-selective media. Compare the survival rates (CFU counts) between the two populations to determine if CRISPR killing efficacy is biased toward metabolically active cells.

# Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: CRISPR-biofilm experiment workflow.

Diagram 2: Biofilm defense mechanisms vs CRISPR.

# Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Biofilm Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Carrier for CRISPR components; enhances stability and cellular uptake. Can be functionalized with targeting ligands. Intrinsic biofilm-disrupting properties. | Spherical, ~20-50 nm diameter; functionalized with cationic polymers for DNA binding [2] [7]. |

| Cationic Liposomes | Lipid-based nanoparticles that encapsulate and protect CRISPR payloads. Fuse with bacterial membranes to deliver content. | Liposomal Cas9/sgRNA formulations; used to achieve >90% biofilm biomass reduction [2]. |

| EPS-Disrupting Enzymes | Pre-treatment to degrade the biofilm matrix and improve nanoparticle penetration. | DNase I (targets eDNA), proteinase K (targets proteins), dispersin B (targets polysaccharides) [6]. |

| Metabolic Activity Probes | To stain and identify metabolically active vs. dormant subpopulations in biofilms for analysis. | CTC (5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride) for respiration; CFDA, SE for esterase activity [6] [4]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes for Labeling | To tag CRISPR components or nanoparticles for tracking and visualization in penetration studies. | Cy3, Cy5, FITC; covalently linked to sgRNA or Cas9 protein. |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors | Co-delivery agent to disrupt biofilm coordination and integrity, sensitizing it to CRISPR attack. | Natural or synthetic molecules that block autoinducer signaling (e.g., furanones) [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is my CRISPR-Cas9 system losing efficiency when targeting bacterial biofilms?

Answer: The biofilm microenvironment is uniquely hostile to biomolecular cargo. The primary causes of efficiency loss are:

- Extracellular Nucleases (DNases/RNases): Secreted by biofilm-resident bacteria and neutrophils to degrade extracellular DNA/RNA, which directly attacks your CRISPR cargo.

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): High levels of ROS within the inflammatory microenvironment of a biofilm can cause oxidative damage to nucleic acids and proteins.

- Entrapment in Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS): The dense EPS matrix can physically sequester cargo, preventing it from reaching target cells and prolonging its exposure to degradative factors.

- Acidic pH: Microenvironments within biofilms can have a lower pH, which can accelerate the hydrolysis of RNA and DNA.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Cargo Degradation

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Performance Indicator to Monitor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid loss of plasmid DNA activity. | Degradation by extracellular DNases. | • Use modified, nuclease-resistant plasmid backbones (e.g., phosphorothioate modifications).• Co-deliver with nuclease inhibitors (e.g., actinonin).• Employ a lipid-based nanocarrier for protection. | % of recovered plasmid DNA remaining intact after biofilm exposure (gel electrophoresis). |

| mRNA cargo fails to express protein. | Degradation by RNases and/or acidic hydrolysis. | • Incorporate chemically modified nucleotides (e.g., N1-methylpseudouridine).• Use optimized 5' cap analogs (e.g., CleanCap) and poly(A) tail stabilization.• Formulate mRNA within LNPs or polymer-based nanoparticles. | mRNA half-life in biofilm-conditioned medium; Protein expression levels via fluorescence (if encoding GFP). |

| RNP complex shows poor gene editing efficiency. | Dissociation of Cas9-gRNA complex or degradation of gRNA. | • Use chemically synthesized, end-modified sgRNA (2'-O-methyl, phosphorothioate).• Pre-complex RNPs with cationic polymers to form stable polyplexes.• Ensure RNP storage buffer is optimized for complex stability. | Gel shift assay to confirm RNP integrity; NGS-based quantification of indel formation efficiency. |

| All cargo types show poor penetration. | Physical entrapment in the EPS matrix. | • Utilize biofilm matrix-degrading enzymes (e.g., DNase I, dispersin B, alginate lyase) as co-treatments.• Employ nanoparticles with a positive surface charge to reduce EPS adhesion.• Use engineered phages for targeted delivery through the matrix. | Confocal microscopy with fluorescently labeled cargo to visualize penetration depth. |

FAQ 2: How can I experimentally quantify the degradation rate of my CRISPR cargo in a biofilm model?

Answer: You need to directly expose your cargo to the biofilm microenvironment and track its integrity over time. Below is a standardized protocol.

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Cargo Half-life in a Biofilm Model

Objective: To determine the stability and half-life of DNA, mRNA, and RNP cargoes when exposed to biofilm-conditioned medium or within a mature biofilm.

Materials:

- Mature biofilm of your target organism (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus).

- Purified CRISPR cargo: plasmid DNA, in vitro transcribed mRNA, pre-complexed RNP.

- Biofilm-conditioned medium (BCM): Sterile-filtered supernatant from a mature biofilm culture.

- Control: Fresh growth medium.

- Quantification tools: Qubit fluorometer, NanoDrop, Bioanalyzer, or RT-qPCR.

- Gel electrophoresis system.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Generate a mature biofilm (e.g., 48-72 hours) in your preferred model (flow cell, microtiter plate). Prepare BCM by centrifuging and filter-sterilizing the supernatant.

- Cargo Exposure: Aliquot your CRISPR cargo (e.g., 1 µg) into:

- Test: BCM.

- Control: Fresh, sterile growth medium.

- Incubate at 37°C with mild agitation.

- Sampling: Withdraw samples at defined time points (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes).

- Analysis:

- DNA/RNA Integrity: Run samples on an agarose gel to visualize smearing versus a sharp band. Use a Bioanalyzer to generate an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) for mRNA.

- Quantitative Recovery: Use Qubit or RT-qPCR to quantify the amount of intact nucleic acid remaining.

- RNP Integrity: Use a native gel shift assay to visualize the intact Cas9-sgRNA complex.

Data Interpretation: Plot the percentage of intact cargo remaining versus time. Fit the data to a first-order decay model to calculate the half-life (t1/2).

Table: Example Quantitative Data from a Cargo Stability Assay

| Cargo Type | Condition | Half-life (t1/2) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA | Fresh Medium | >240 min | Minimal degradation. |

| Plasmid DNA | Biofilm-Conditioned Medium | 45 min | Significant degradation after 60 min. |

| Unmodified mRNA | Fresh Medium | 90 min | Baseline hydrolysis. |

| Unmodified mRNA | Biofilm-Conditioned Medium | <15 min | Rapid, complete degradation. |

| Chemically modified mRNA | Biofilm-Conditioned Medium | 75 min | Improved stability over unmodified. |

| RNP (unmodified sgRNA) | Biofilm-Conditioned Medium | 30 min | Loss of functional complex. |

| RNP (modified sgRNA) | Biofilm-Conditioned Medium | 110 min | Significant stability improvement. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biofilm CRISPR Research |

|---|---|

| Nuclease-Resistant DNA Backbones | Plasmid vectors with phosphorothioate linkages in the backbone to resist degradation by extracellular DNases. |

| Chemically Modified Nucleotides | (e.g., 2'-Fluoro, 2'-O-Methyl, N1-methylpseudouridine). Incorporated into RNA to shield against RNase cleavage and reduce immunogenicity. |

| Cationic Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Formulations that encapsulate and protect nucleic acid cargo (mRNA, DNA), facilitating fusion with bacterial membranes and release inside the cell. |

| Cationic Polymers (e.g., PEI, Chitosan) | Can condense nucleic acids or form co-complexes with RNPs to improve stability, prevent dissociation, and enhance delivery. |

| Biofilm Matrix-Degrading Enzymes | DNase I (degrades eDNA), Dispersin B (degrades PNAG), Alginate Lyase (degrades alginate). Used as co-treatments to disrupt the EPS for improved cargo penetration. |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Scavengers | (e.g., N-acetylcysteine, Thiourea). Can be included in formulations to protect cargo from oxidative damage within the biofilm. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Cargo Degradation & Mitigation Workflow

Biofilm Defense Against CRISPR Cargo

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor CRISPR Editing Efficiency in Mature Biofilms

Q1: Why is my CRISPR-Cas9 system showing high editing efficiency in planktonic cells but very low efficiency in a 48-hour mature biofilm?

A: This is a common issue rooted in the biofilm microenvironment. The primary factors are:

- Reduced Penetration: Plasmid vectors or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes cannot effectively diffuse through the dense, negatively charged extracellular polymeric substance (EPS).

- Altered Cell Physiology: Cells in a biofilm, especially those in deeper, nutrient-deprived layers, have reduced metabolic activity and may not express the necessary machinery for plasmid replication or Cas protein translation.

- Presence of Nucleases: The EPS can contain extracellular nucleases that degrade DNA or RNA guides before they reach the target cells.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Assess Delivery Vector: Switch from plasmid DNA to pre-assembled Cas9 RNP complexes. RNPs are faster-acting and avoid the need for intracellular transcription and translation, which is beneficial for metabolically dormant cells.

- Modify Delivery Method:

- Chemical Permeabilization: Co-administer with EPS-disrupting agents like DNase I (to degrade extracellular DNA in the matrix) or dispersin B (to hydrolyze polysaccharides). See Table 1 for dosage.

- Physical Methods: Consider using electroporation optimized for surface-associated biofilms or microinjection for single-cell analysis within the biofilm structure.

- Verify Target Accessibility: Re-design sgRNAs to target genomic regions that are accessible in the biofilm state. Some genes may be transcriptionally silenced in sessile cells. Perform an RNA-seq comparison to confirm target gene expression.

Q2: My CRISPR-modified biofilm cells rapidly revert to the wild-type genotype after the selective pressure is removed. How can I improve construct stability?

A: This indicates a lack of stable genomic integration or the survival and regrowth of non-edited persister cells.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Editing: Use a combination of assays. Amplify the target region from cells extracted from different biofilm layers (top, middle, bottom) and sequence them individually. Bulk sequencing can miss heterogeneous editing.

- Employ a Double-Selection Strategy:

- Use a CRISPR system that introduces a stable antibiotic resistance marker alongside the gene knockout.

- Alternatively, use a toxin-antidote system (e.g., CRISPRi) where continuous expression of the sgRNA is required to repress a toxic gene.

- Target Essential Genes: For functional studies, design your CRISPR system to target a gene essential for biofilm integrity (e.g., pel or psl in P. aeruginosa). The loss-of-function mutation will be inherently selected against in a biofilm context.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q3: What is the most effective method for delivering CRISPR components into a bacterial biofilm? A: Currently, no single method is perfect. The most promising paradigm is a combinatorial approach. Pre-assembled RNP complexes, delivered with EPS-disrupting enzymes (e.g., DNase I) and a carrier system like lipid-based nanoparticles or engineered bacteriophages, show significantly improved efficacy over traditional plasmids.

Q4: How do I quantify and normalize editing efficiency in a heterogeneous biofilm? A: This is a critical challenge. Do not rely on bulk measurements.

- Spatial Resolution: Section the biofilm using cryosectioning or laser capture microdissection.

- Single-Cell Analysis: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to separate cells based on a reporter (like GFP) coupled to the CRISPR system, then plate or sequence them.

- Normalization: Normalize your editing data (e.g., from qPCR or sequencing) to the total bacterial biomass (via DNA content) or a constitutively expressed housekeeping gene from the same section.

Q5: Are there specific Cas proteins better suited for biofilm applications? A: Yes. Smaller Cas proteins (e.g., Cas12f, CasΦ) are advantageous for delivery via viral vectors. Furthermore, Cas proteins with high activity at lower temperatures (relevant for deeper, nutrient-poor biofilm layers) or those engineered for higher fidelity (e.g., HiFi Cas9) are beneficial for reducing off-target effects in slow-growing cells.

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of CRISPR Delivery Modalities in Biofilm vs. Planktonic Cells

| Delivery Modality | Editing Efficiency (Planktonic) | Editing Efficiency (Biofilm) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation in Biofilm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA (Electroporation) | 70-95% | 5-15% | Stable, long-term expression | Poor diffusion; requires cell division |

| Pre-assembled RNP (Electroporation) | 80-90% | 20-40% | Fast action; no replication needed | Limited by delivery efficiency |

| RNP + DNase I Co-treatment | 85-95% | 45-65% | Disrupts matrix; enhances penetration | Can be cytotoxic at high doses |

| Bacteriophage-Mediated | 60-80%* | 25-50%* | High target specificity | Limited cargo capacity; host range |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | 50-70% | 30-55% | Protects cargo; biocompatible | Optimization required for bacterial use |

*Efficiency is highly dependent on the host range and infectivity of the phage.

Table 2: Impact of Biofilm Age and Matrix Composition on CRISPR-Cas9 Efficacy

| Biofilm Age (Hours) | EPS Thickness (µm) | Metabolic Activity (Relative %) | RNP Delivery Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 15 ± 3 | 100% | 35 ± 8 |

| 48 | 40 ± 7 | 65 ± 10 | 18 ± 5 |

| 72 | 85 ± 12 | 30 ± 8 | 5 ± 2 |

| 96 | 120 ± 15 | 15 ± 5 | <2 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing CRISPR Editing in a Spatial Context within a Biofilm

Objective: To determine the CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency across different layers of a mature biofilm.

Materials:

- Mature bacterial biofilm (e.g., 48-72 hour P. aeruginosa or S. aureus)

- Pre-assembled Cas9-sgRNA RNP complex

- DNase I solution (1 mg/mL in PBS)

- Cryostat

- Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates

- PCR reagents and primers for the target locus

- T7 Endonuclease I assay kit

Methodology:

- Biofilm Treatment: Gently wash the established biofilm with PBS. Apply the Cas9 RNP complex (e.g., 5 µM) with or without co-treatment with DNase I (100 µg/mL) for 1 hour.

- Spatial Sectioning: Embed the entire biofilm in OCT compound and rapidly freeze it. Using a cryostat, serially section the biofilm into 10 µm thick slices representing the top, middle, and bottom layers.

- Cell Recovery & DNA Extraction: Dissolve the OCT compound from each section in PBS, vortex vigorously to disaggregate cells, and pellet them. Extract genomic DNA from each pellet.

- Editing Analysis:

- T7E1 Assay: Amplify the target genomic region from each sample. Hybridize and digest with T7 Endonuclease I, which cleaves mismatched heteroduplex DNA. Analyze fragments on an agarose gel.

- Calculation: Editing efficiency (%) = (1 - (1 / (fraction cleaved))^0.5) * 100, where fraction cleaved = (sum of cleaved band intensities) / (sum of cleaved and uncut band intensities).

Protocol 2: Evaluating Construct Stability Using a Fluorescence-Based Competition Assay

Objective: To track the persistence of CRISPR-edited cells within a mixed-population biofilm over time.

Materials:

- Wild-type strain (WT)

- CRISPR-edited strain, constitutively expressing a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) (EDIT)

- Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM)

- Flow cytometer

Methodology:

- Biofilm Establishment: Inoculate a flow cell or microtiter plate with a 1:1 mixture of WT and EDIT cells. Allow a biofilm to form for 24 hours under standard conditions.

- Long-Term Flow: Continuously feed the biofilm with fresh, non-selective medium for 5-7 days.

- Monitoring: At 24-hour intervals, harvest biofilms and analyze the ratio of GFP-positive (EDIT) to GFP-negative (WT) cells using flow cytometry.

- Imaging: Use CLSM to capture z-stack images of the biofilm at each time point to visualize the spatial distribution and dominance of each population.

- Data Analysis: Plot the percentage of EDIT cells over time. A rapid decline indicates low construct stability or a fitness cost associated with the edit.

Visualizations

Title: CRISPR Delivery Barriers in Biofilm

Title: Spatial Editing Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biofilm CRISPR Research |

|---|---|

| Pre-assembled Cas9 RNP | Bypasses the need for intracellular transcription/translation; crucial for targeting metabolically dormant biofilm cells. |

| DNase I | An enzyme that degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA) in the biofilm matrix, reducing viscosity and improving diffusion of CRISPR components. |

| Dispersin B | A glycoside hydrolase that hydrolyzes poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG), a key polysaccharide in many bacterial biofilms, disrupting the matrix. |

| Cryostat | A device used to cut thin, frozen sections of a biofilm, enabling spatial analysis of editing efficiency from top to bottom. |

| T7 Endonuclease I | An enzyme used in a mismatch detection assay to quantify the frequency of CRISPR-induced indels without the need for deep sequencing. |

| Conjugative Plasmid | A vector capable of transferring DNA from a donor to a recipient cell via conjugation, potentially useful for delivering CRISPR machinery to inner biofilm layers. |

| Synthetic Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Engineered nanocarriers that can encapsulate and protect CRISPR RNPs or DNA, facilitating fusion with bacterial membranes for delivery. |

Advanced Armor: Nanoparticle Engineering for Robust CRISPR Delivery and Stability in Biofilms

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor CRISPR Editing Efficiency in Biofilm Models

- Q: I am observing very low knockout efficiency in my biofilm model when using plasmid DNA. What could be the cause?

- A: Low efficiency with plasmid DNA is frequently due to poor penetration through the dense extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) of the biofilm and the inability to transfert the majority of bacterial cells within the structure. The plasmid may also be degraded by nucleases present in the biofilm microenvironment before it can enter cells.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Quantify Penetration: Use a fluorescently labelled plasmid (e.g., with Cy5) and perform confocal microscopy with z-stacking to visualize and quantify penetration depth into the biofilm.

- Alternative Cargo: Switch to a pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. RNPs are smaller and more stable, often showing superior penetration and immediate activity without the need for transcription/translation.

- Optimize Delivery: Consider using a nanoparticle or lipid-based carrier specifically designed for biofilm penetration to co-deliver with your CRISPR construct.

- Check Cargo Stability: Assess the integrity of your plasmid after exposure to biofilm conditioned medium via gel electrophoresis to check for degradation.

Problem 2: High Off-Target Effects with mRNA Delivery

- Q: My mRNA-based CRISPR system shows high editing efficiency but also significant off-target effects in my biofilm assays. How can I reduce this?

- A: mRNA delivery can lead to prolonged and high levels of Cas protein expression, which is a known factor for increasing off-target activity. The extended presence of the nuclease increases the chance of cleavage at imperfectly matched sites.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Switch from standard Cas9 to a high-fidelity version like eSpCas9(1.1) or SpCas9-HF1, which can be delivered as mRNA.

- Optimize Dosage: Titrate the mRNA concentration to find the lowest dose that provides sufficient on-target editing, thereby minimizing off-target effects.

- Switch to RNP: RNP complexes have a shorter intracellular half-life, which drastically reduces off-target effects while maintaining high on-target efficiency. This is often the most effective solution.

- Analyze Off-Targets: Perform genome-wide off-target analysis (e.g., GUIDE-seq or CIRCLE-seq) specific to your biofilm-grown cells to identify and confirm problematic sites.

Problem 3: Rapid Degradation of Cargo in Biofilm Conditioning Medium

- Q: My nucleic acid cargo (DNA/mRNA) appears to be degraded when incubated with biofilm-conditioned medium, before even reaching the cells. How can I improve stability?

- A: Biofilm microenvironments are rich in nucleases (DNases and RNases) released by cells and other microbes. Standard nucleic acids are highly susceptible.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use Chemically Modified Nucleic Acids: For mRNA, use chemically modified nucleotides (e.g., pseudo-uridine, 5-methylcytidine) to increase stability and reduce immunogenicity. For DNA, consider phosphorothioate backbone modifications.

- Employ Protective Carriers: Formulate your cargo within protective nanoparticles (e.g., lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) or polymeric nanoparticles) that shield it from nucleases until cellular uptake.

- Pre-assembled RNP: The protein component of the RNP complex offers inherent protection to the guide RNA. Furthermore, chemically modified sgRNAs (with 2'-O-methyl, phosphorothioate modifications at the 3' end) are highly resistant to RNase degradation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Which cargo type is generally best for achieving high editing efficiency with low off-target effects in a mature biofilm?

- A: Based on current research, pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes are often superior. They combine rapid activity (no transcription/translation needed), short intracellular lifetime (reducing off-targets), and favorable size/charge characteristics for better penetration compared to plasmid DNA.

Q: Can I use standard transfection reagents developed for planktonic cells for biofilm delivery?

- A: Generally, no. Standard transfection reagents are optimized for single, suspended cells. The EPS matrix of a biofilm can inhibit the interaction between the reagent and the target cells, leading to very low efficiency. You should use reagents or methods specifically validated for biofilms or complex 3D structures.

Q: How do I quantify and compare the penetration depth of different cargos into my biofilm model?

- A: The standard method is to fluorescently label each cargo type (e.g., with different dyes like Cy3, Cy5) and use confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). Acquire z-stack images through the biofilm depth and use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to plot fluorescence intensity versus depth to generate penetration profiles.

Q: Why is RNP considered more stable than mRNA in the biofilm context?

- A: Stability refers to resistance to the biofilm microenvironment. The sgRNA in an RNP is physically protected within the Cas protein scaffold, making it less accessible to RNases. In contrast, free mRNA is rapidly degraded by ubiquitous RNases. Chemically modified sgRNAs within the RNP further enhance this stability.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of CRISPR Cargo Properties for Biofilm Applications

| Property | Plasmid DNA | mRNA | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Size (kDa/nm) | ~3000-5000 kDa / >100 nm | ~300-500 kDa / ~10-15 nm | ~160 kDa / ~10-15 nm |

| Biofilm Penetration Depth | Low (10-20% of biofilm thickness) | Moderate (30-50% of biofilm thickness) | High (50-80% of biofilm thickness) |

| Onset of Action | Slow (24-72 h) | Moderate (12-24 h) | Fast (1-6 h) |

| Duration of Action | Long (days) | Moderate (1-3 days) | Short (< 24 h) |

| Off-Target Effect Risk | High | High | Low |

| Stability in Biofilm Medium | Low (DNase sensitive) | Very Low (RNase sensitive) | High (RNase resistant, esp. with modified sgRNA) |

| Immunogenicity | High (TLR9 activation) | High (TLR7/8 activation) | Low |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Cargo Penetration in a Biofilm using Confocal Microscopy

- Biofilm Growth: Grow a standardized biofilm (e.g., P. aeruginosa or S. aureus) on a glass-bottom dish or a flow cell for 48-72 hours.

- Cargo Labeling: Label your cargos with distinct fluorophores.

- Plasmid DNA: Label with Cy5 using a Label IT nucleic acid labeling kit.

- mRNA: Use commercially purchased Cy3-labeled mRNA or label in-house.

- RNP: Use a fluorescently labeled Cas9 protein (e.g., SNAP-tag) or a Cy5-labeled sgRNA.

- Application: Gently apply a solution containing a standardized concentration (e.g., 500 nM) of the labeled cargo onto the mature biofilm. Incubate for a set time (e.g., 4 hours) under appropriate conditions.

- Washing and Fixation: Gently wash the biofilm with PBS to remove non-internalized cargo. Fix with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15-30 minutes.

- Imaging: Image using a confocal microscope. Collect z-stack images from the top to the bottom of the biofilm at consistent intervals (e.g., 1 µm steps).

- Analysis: Use ImageJ or similar software to measure the mean fluorescence intensity in each z-slice. Normalize the data to the maximum intensity and plot against depth to generate a penetration profile.

Protocol 2: Evaluating CRISPR-Cas Editing Efficiency in a Biofilm

- Biofilm Setup & Treatment: Establish biofilms from a strain containing a reporter gene (e.g., GFP) that can be knocked out. Treat the mature biofilm with your CRISPR cargo (DNA, mRNA, or RNP) complexed with your chosen delivery vehicle.

- Recovery and Dispersal: After treatment (e.g., 24-48 hours), gently scrape the biofilm from the surface and disperse it into single-cell suspension using vigorous vortexing and/or enzymatic treatment with DNase I and dispersin B.

- Analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: For a GFP knockout assay, analyze the cell suspension by flow cytometry. The percentage of GFP-negative cells indicates the editing efficiency.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): For endogenous targets, extract genomic DNA from the dispersed biofilm cells. Amplify the target region by PCR and subject the amplicons to NGS. Analyze the sequences for insertions/deletions (indels) at the target site to calculate precise editing efficiency.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Cargo Penetration & Activity Workflow

Diagram 2: Intracellular Mechanism of Cargo Types

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biofilm CRISPR Delivery

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Increases nuclease resistance and stability of RNP complexes within the biofilm matrix. Crucial for maintaining activity. |

| High-Fidelity Cas Protein | Reduces off-target editing effects, which is critical for accurate genetic analysis in a heterogeneous biofilm population. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | A delivery vehicle that encapsulates nucleic acids (mRNA, DNA) or proteins (RNP), protecting them from degradation and enhancing cellular uptake in biofilms. |

| Biofilm-Disrupting Enzymes (e.g., DNase I, Dispersin B) | Used to disperse biofilms into single-cell suspensions for accurate downstream analysis like flow cytometry or colony counting. |

| Confocal Microscopy Dish | Specialized glass-bottom dishes for growing biofilms and performing high-resolution z-stack imaging to quantify cargo penetration. |

| Fluorescent Labeling Kits (e.g., Cy3, Cy5) | For covalently tagging DNA, RNA, or proteins to enable visualization and tracking of cargo penetration and localization. |

| Synergy Hydrogels | Synthetic hydrogels used to create a standardized, EPS-mimicking environment for initial screening of cargo penetration and stability. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Common LNP Formulation & CRISPR Delivery Issues

Q1: My LNP formulations consistently show low encapsulation efficiency (<70%) for CRISPR ribonucleoproteins (RNPs). What could be the cause and how can I improve this?

A: Low encapsulation efficiency typically stems from suboptimal formulation conditions or RNP compatibility issues.

Primary Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incorrect lipid-to-RNP mass ratio.

- Solution: Titrate the ionizable lipid to RNP ratio. We recommend starting with a range of 10:1 to 50:1 (w/w) and using a microfluidics device for reproducible mixing.

- Cause: Instability of the RNP complex during the acidic buffer exchange step.

- Solution: Ensure the RNP is properly complexed and stabilized. Consider using a citrate buffer at pH 4.0 instead of acetate, and minimize the time the RNP spends in the acidic environment.

- Cause: Inefficient mixing in microfluidics device.

- Solution: Optimize the flow rate ratio (FRR). A higher aqueous-to-organic flow rate ratio (e.g., 3:1) often improves encapsulation for large complexes like RNPs.

Recommended Optimization Protocol:

- Prepare lipid stock in ethanol (e.g., Ionizable Lipid:DSPC:Cholesterol:DMG-PEG 2000 at 50:10:38.5:1.5 mol%).

- Dilute CRISPR RNP in 25 mM citrate buffer, pH 4.0.

- Use a microfluidic device to mix the two phases. Systematically vary the Total Flow Rate (TFR) from 8 to 16 mL/min and the Flow Rate Ratio (FRR, aqueous:organic) from 2:1 to 4:1.

- Dialyze the formed LNPs against 1X PBS, pH 7.4, for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Measure encapsulation efficiency using the Quant-iT RiboGreen assay.

Q2: I am observing high cytotoxicity and low transfection efficiency when treating bacterial biofilms with my CRISPR-LNPs. What factors should I investigate?

A: This is a common challenge in the harsh biofilm microenvironment. The issue likely relates to LNP stability, surface properties, or biofilm penetration.

Investigation Pathway:

- Check LNP Stability: Use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to confirm your LNPs are stable in the specific biofilm culture medium (e.g., LB, TSB). Aggregation can cause non-specific toxicity.

- Modify Surface Charge: Highly cationic surfaces can cause non-specific binding and toxicity. Ensure your formulation uses an ionizable lipid that is neutral at physiological pH to reduce non-specific interactions.

- Functionalize with Targeting Ligands: To enhance penetration and uptake within the biofilm, consider conjugating your LNPs with biofilm-penetrating peptides (e.g., KFF-KFF-KFF) or enzymes that degrade the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS).

Experimental Workflow for Biofilm Transfection:

Title: Biofilm Transfection with CRISPR-LNPs

Q3: My CRISPR-LNPs show poor stability and payload leakage during storage. How can I enhance their long-term stability?

A: Payload leakage is often due to lipid packing defects or chemical degradation.

Stabilization Strategies:

- Lyophilization (Freeze-Drying): This is the gold standard for long-term storage. Include cryoprotectants like sucrose or trehalose (e.g., 10% w/v) in the final buffer before freezing and lyophilization.

- Optimize Lipid Composition: Increase the molar percentage of the structural lipid (e.g., DSPC) to strengthen the LNP bilayer and reduce permeability.

- Storage Conditions: Always store LNPs at 4°C. For lyophilized products, store at -20°C or -80°C. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles of liquid formulations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the critical difference between formulating LNPs for siRNA versus CRISPR RNP delivery? A: The primary difference lies in the payload's size, charge, and stability. CRISPR RNPs are large, multi-subunit protein-nucleic acid complexes, whereas siRNA is a small, double-stranded RNA. This requires optimization of the ionizable lipid for efficient RNP encapsulation, often needing a higher pKa (~6.5-6.8) than for siRNA (~6.2-6.4). Furthermore, the formulation process must be gentle to avoid denaturing the Cas9 protein.

Q2: Which technique is most accurate for measuring the encapsulation efficiency of CRISPR cargo in LNPs? A: The Ribogreen Assay is the most accurate and widely accepted method. It involves measuring the fluorescence of the RNA guide in the RNP complex before and after disruption of the LNPs with a detergent (like Triton X-100). The difference between the total and free signal gives the encapsulated fraction.

Q3: How can I achieve controlled or triggered release of the CRISPR payload from LNPs specifically within a biofilm? A: Controlled release can be engineered by designing LNPs that respond to stimuli unique to the biofilm microenvironment.

- pH-Triggered Release: Use an ionizable lipid with a pKa tuned to become positively charged and disruptive in the slightly acidic regions of a mature biofilm.

- Enzyme-Triggered Release: Incorporate lipids linked to a substrate that is cleaved by biofilm-specific enzymes (e.g., matrix-degrading enzymes like DNase or dispersin B). The cleavage event destabilizes the LNP, releasing the payload.

Controlled Release Mechanisms:

Title: Triggered Release from CRISPR-LNPs

Table 1: Impact of Flow Rate Ratio (FRR) on LNP Characteristics for RNP Encapsulation

| Aqueous:Organic FRR | Average Size (nm) | PDI | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2:1 | 145 | 0.18 | 75 | -2.1 |

| 3:1 | 112 | 0.12 | 88 | -3.5 |

| 4:1 | 98 | 0.09 | 82 | -4.8 |

| 5:1 | 135 | 0.15 | 70 | -5.2 |

Data generated using a fixed lipid composition and TFR of 12 mL/min.

Table 2: Efficacy of Different Ionizable Lipids in CRISPR-Mediated Gene Knockout in a S. aureus Biofilm Model

| Ionizable Lipid | pKa (Theoretical) | Gene Editing Efficiency (%) | Biofilm Cell Viability (% of Control) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid A (DLin-MC3-DMA) | 6.4 | 15 | 85 |

| Lipid B (SM-102) | 6.7 | 45 | 60 |

| Lipid C (Custom) | 6.9 | 65 | 40 |

| LNP-only Control | N/A | 0 | 95 |

Editing efficiency measured by NGS of target locus after 24h treatment. Viability measured by ATP-based assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in CRISPR-LNP Formulation |

|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102) | The key functional lipid that enables encapsulation and endosomal escape. Becomes positively charged in acidic endosomes. |

| Helper Lipid (DSPC) | A structural phospholipid that enhances bilayer stability and promotes fusion with endosomal membranes. |

| Cholesterol | Incorporates into the LNP bilayer to improve stability, rigidity, and fluidity. Aids in cellular uptake. |

| PEG-lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG2000) | Provides a hydrophilic corona that stabilizes LNPs during formation, reduces aggregation, and modulates pharmacokinetics. |

| Microfluidic Device (e.g., NanoAssemblr) | Enables rapid, reproducible, and scalable mixing of lipid and aqueous phases to form uniform, monodisperse LNPs. |

| SYBR Gold / RiboGreen Assay | Fluorescent dyes used to accurately quantify the encapsulation efficiency of the gRNA within the RNP complex. |

| Sucrose/Trehalose | Cryoprotectants used during lyophilization (freeze-drying) to maintain LNP integrity and payload stability for long-term storage. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Gene Editing Efficiency

Q: I am using gold nanoparticles to deliver Cas9 RNP, but my gene editing efficiency is lower than expected. What could be the cause?

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal RNP Loading | Inefficient conjugation of the RNP complex to the nanoparticle surface reduces the functional payload delivered into the cell. | - Ensure proper functionalization of gold nanoparticles with cationic coatings (e.g., cationic arginine) to enhance RNP binding via electrostatic interactions [9].- Characterize loading efficiency using techniques like gel electrophoresis or HPLC to quantify unbound RNP. |

| Poor Endosomal Escape | The nanoparticle is trapped and degraded in the endosome, preventing RNP release into the cytoplasm. | - Co-deliver endosomolytic agents. For example, "CRISPR-Gold" incorporates an endosomal disruption polymer [9].- Optimize the surface chemistry and size of nanoparticles to promote endosomal escape mechanisms [10]. |

| RNP Aggregation | Cas9 protein aggregation can form large, insoluble clusters that are difficult to encapsulate and deliver efficiently, reducing functional editing complexes [10]. | - Use fresh, high-quality Cas9 protein and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.- Include stabilizing agents in your formulation buffers.- Monitor aggregation status via dynamic light scattering (DLS) to ensure nanoparticle size remains within the optimal sub-150 nm range. |

| Inadequate Nuclear Localization | The RNP complex fails to be imported into the nucleus where it can access the genomic DNA. | - Fuse nuclear localization signals (NLS) to the Cas9 protein sequence to actively shuttle the complex through the nuclear pore [11]. |

Problem 2: Nanoparticle Instability in Biofilm Microenvironments

Q: My nanoparticle-RNP complexes aggregate or degrade when introduced to biofilm cultures. How can I improve their stability?

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Specific Interactions with EPS | The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) in biofilms can entrap nanoparticles or foul their surfaces, reducing penetration and delivery efficiency [12]. | - Functionalize nanoparticles with a dense layer of PEG (polyethylene glycol) to create a "stealth" effect, reducing non-specific binding [9].- Use coatings like chitosan, which has inherent biofilm-penetrating and antimicrobial properties [9]. |

| Degradation by Bacterial Nucleases | Nucleases present in the biofilm microenvironment can degrade the sgRNA component of the RNP, rendering it inactive. | - Ensure the RNP is fully complexed and protected within the nanoparticle's core or shell. Pre-formed RNP complexes offer some inherent protection compared to nucleic acid delivery [11].- Utilize chemically synthesized, modified sgRNAs with phosphorothioate bonds or 2'-O-methyl groups to enhance nuclease resistance [13]. |

Problem 3: Off-Target Editing Effects

Q: Despite using RNP delivery to reduce off-target effects, I am still detecting unintended edits. How can nanoparticle design further improve specificity?

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Prolonged Intracellular Activity | Even with transient RNP delivery, extended presence of active Cas9 can increase the chance of off-target cleavage. | - The transient nature of RNP delivery itself is the best mitigation. Using nanoparticles ensures this transient activity [11]. Confirm that your formulation does not inadvertently cause RNP accumulation or aggregation that extends its half-life.- Utilize high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) in your RNP complexes, which are engineered for reduced off-target activity [14]. |

| Inconsistent Cellular Uptake | Heterogeneous delivery across a cell population can lead to variable editing, where some cells are undertreated and others are overtreated. | - Optimize nanoparticle surface charge (zeta potential) and size for uniform and efficient cellular uptake. A slightly positive surface charge often enhances interaction with negatively charged cell membranes [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) particularly popular for RNP delivery?

Gold nanoparticles offer several unique advantages:

- Surface Functionalization: Their surface can be easily and stably modified with a variety of molecules (e.g., thiol-terminated polymers, peptides, DNA) for conjugating RNPs and enhancing stability [9].

- Biocompatibility: They are generally considered biocompatible and exhibit low cytotoxicity [9].

- Proven Efficacy: Systems like cationic arginine gold nanoparticles (ArgNPs) have demonstrated high delivery efficiency (~90%) and significant gene editing efficiency (23–30%) in vitro [9]. Another platform, CRISPR-Gold, showed 40-50% editing efficiency at the protein and mRNA level in vivo for a target gene [9].

Q2: What other inorganic nanoparticles are used for RNP delivery besides gold?

While gold is prominent, other inorganic materials are being explored:

- Zeolite Imidazole Frameworks (ZIFs): These are porous, biodegradable materials that can encapsulate large biomolecules like RNPs and release them in response to specific physiological conditions, such as the acidic pH found in endosomes or some biofilm microenvironments [9].

Q3: How does RNP delivery via nanoparticles compare in efficiency to viral delivery methods?

It's a trade-off between efficiency, safety, and payload capacity. The table below summarizes key differences relevant to biofilm and antimicrobial research:

| Feature | Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV) | Nanoparticle RNP Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Editing Speed | Slow (requires transcription/translation) | Very fast (functional RNP is active immediately) [11] |

| Duration of Activity | Long-term/persistent expression | Short, transient activity [11] |

| Immunogenicity | Can trigger significant immune responses [9] | Generally lower immunogenicity [15] |

| Off-Target Risk | Higher (prolonged Cas9 expression) | Lower (transient activity reduces off-target effects) [15] [11] |

| Payload Capacity | Limited (AAV: ~4.7 kb) [9] | High (can deliver large, pre-assembled RNPs) [15] |

| Targeting Flexibility | Moderate (depends on serotype) | High (surface can be easily modified for targeting) [12] |

| Applicability to Bacteria | Low (viruses infect specific hosts) | High (can be engineered to target bacterial cells in biofilms) [12] |

Q4: For targeting biofilms, what specific bacterial genes should my gRNA target?

When designing CRISPR/Cas9 to combat biofilm-driven antibiotic resistance, target selection is critical. Effective gRNAs can be designed to disrupt:

- Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs): Directly target and disrupt genes like bla (beta-lactamase), mecA (methicillin resistance), or ndm-1 (carbapenem resistance) [12].

- Quorum Sensing (QS) Genes: Disrupt bacterial cell-to-cell communication, which is crucial for biofilm formation and maturation [12].

- Biofilm-Regulating Factors: Target genes involved in the production of the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix, adhesins, or regulators of the biofilm lifecycle [12].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Key Protocol: Formulating Cationic Polymer-Coated Gold Nanoparticles for RNP Delivery

This protocol outlines a common method for creating gold nanoparticles capable of binding and delivering Cas9 RNP complexes.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Chloroauric Acid (HAuCl₄) | Precursor for synthesizing gold nanoparticle cores. |

| Citrate or Borohydride Reducers | Used to reduce gold ions to form colloidal gold nanoparticles. |

| Cationic Polymer (e.g., PEI) | Coats the nanoparticle, providing a positive surface charge to bind negatively charged RNPs. |

| Cas9 Nuclease | The core editing protein. Must be pure and have high activity. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Guides the Cas9 to the target DNA sequence. Modifications enhance stability. |

| Dialysis Membranes or Filters | For purifying and concentrating the final nanoparticle-RNP complex. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Synthesize Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs): Prepare ~15-20 nm AuNPs by reducing HAuCl₄ with sodium citrate. This results in negatively charged citrate-capped AuNPs [9].

- Functionalize with Cationic Coating: Incubate the AuNPs with a cationic polymer, such as polyethylenimine (PEI). The polymer will electrostatically adsorb to the AuNP surface, creating a positively charged layer. Purify the coated particles to remove excess polymer [9].

- Formulate RNP Complex: Pre-complex the Cas9 protein and sgRNA at an optimal molar ratio (e.g., 1:1.2) in a suitable buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form the active ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex [13] [11].

- Load RNP onto Nanoparticles: Mix the cationic AuNPs with the pre-formed RNP complex. The positive charge on the nanoparticles will attract and bind the negatively charged RNP. Incubate for 30-60 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Purify the Complex: Remove unbound RNP and concentrate the final formulation using centrifugal filters or dialysis. This step is crucial for ensuring consistency and maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio in your experiments.

- Characterize the Final Product: Use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to measure the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential. Confirm an increase in size after RNP loading and a zeta potential that is less positive than the coated-but-unloaded AuNPs, indicating successful binding.

Workflow Diagram: RNP Delivery via Inorganic Nanoparticles for Biofilm Targeting

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from studies utilizing inorganic nanoparticles for CRISPR RNP delivery, providing benchmarks for your own experiments.

| Nanoparticle Platform | Cargo Type | Reported Editing Efficiency | Key Application Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cationic Arginine Gold Nanoparticles (ArgNPs) | RNP | ~90% delivery efficiency; 23–30% gene editing efficiency | in vitro editing in human cell lines [9] | |

| CRISPR-Gold | RNP | 40–50% (reduction in target protein/mRNA) | in vivo editing in mouse model [9] | |

| Gold Nanoparticle Hybrids | CRISPR/Cas9 | 3.5-fold increase in editing efficiency vs. non-carrier | Anti-biofilm application against P. aeruginosa [12] |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Encapsulation Efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9 RNP

- Problem: The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of the Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex into your PLGA-PEG nanoparticles is consistently below 40%, leading to poor gene editing outcomes.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Incompatibility between the aqueous RNP solution and the organic solvent (e.g., DCM, ethyl acetate) used in the double emulsion process.

- Solution: Optimize the primary emulsion sonication time and amplitude. A shorter, gentler sonication (e.g., 10-15 seconds at 30% amplitude) can help stabilize the first water-in-oil emulsion before adding to the outer aqueous phase.

- Cause: Insufficient concentration of stabilizer (e.g., PVA) in the outer aqueous phase.

- Solution: Increase the concentration of PVA to 2-3% (w/v) to better stabilize the double emulsion droplets and prevent RNP leakage.

- Cause: The RNP complex is degrading during the emulsion process.

- Solution: Include RNase inhibitors and protease inhibitors in the inner aqueous phase buffer. Perform the entire process on ice or in a cold room.

Issue 2: Ineffective Antibiotic Release in Biofilm Microenvironment

- Problem: The encapsulated antibiotic (e.g., Ciprofloxacin) is not being released effectively at the biofilm site, despite in vitro data showing good release profiles.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: The biofilm's hypoxic and acidic conditions are not sufficient to trigger the release from your pH-sensitive polymer (e.g., Eudragit).

- Solution: Characterize the exact pH of your specific biofilm model. Consider using a polymer with a higher pKa or one that is enzymatically cleaved by biofilm-specific enzymes (e.g., matrix-degrading enzymes).

- Cause: The nanoparticles are failing to penetrate the dense extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) of the biofilm.

- Solution: Functionalize the nanoparticle surface with biofilm-penetrating peptides (e.g., DNase I, dispersin B, or cationic peptides). Refer to the protocol below.

Issue 3: Reduced CRISPR-Mediated Gene Editing in Biofilm Bacteria

- Problem: Even with good encapsulation and cellular uptake, the targeted gene knockout (e.g., of a beta-lactamase gene) is inefficient within the biofilm.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Low metabolic activity of bacteria in the biofilm core reduces the efficiency of homology-directed repair (HDR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).

- Solution: Time the administration of nanoparticles to coincide with a more active growth phase, or pre-treat with a sub-inhibitory concentration of antibiotic to induce a stress response that may increase editing efficiency.

- Cause: The CRISPR-Cas9 construct is unstable or degraded in the biofilm microenvironment before reaching the bacterial cytoplasm.

- Solution: Ensure the RNP is properly complexed with a protective, cationic polymer like polyethyleneimine (PEI) within the nanoparticle core to shield it from nucleases.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the optimal N/P ratio for complexing the anionic RNP with cationic polymers inside the nanoparticle? A1: The optimal N/P (Nitrogen/Phosphate) ratio is critical. For PEI-based complexation, a ratio between 8 and 12 typically provides a good balance between efficient RNP condensation, colloidal stability, and minimal cytotoxicity. We recommend performing a gel retardation assay to confirm complete complexation.

Q2: How do I quantify the synergistic effect between the antibiotic and the CRISPR component? A2: Synergy is best quantified using the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI). Calculate it using the checkerboard assay method outlined in the protocol section. A FICI of ≤0.5 indicates synergy.

Q3: My nanoparticles are aggregating in the bacterial culture media. How can I improve stability? A3: Aggregation is often due to salt-induced instability. Ensure you are using a sufficient concentration of PEG in your polymer (PLGA-PEG) to provide a steric hydration barrier. You can also add a small amount of a non-ionic surfactant (e.g., 0.01% Tween 80) to your suspension buffer.

Q4: Which biofilm model is most appropriate for testing these hybrid systems? A4: For initial screening, the static 96-well plate crystal violet assay is sufficient. For more advanced, physiologically relevant testing, a flow cell system that allows for continuous nutrient supply and waste removal is recommended, as it forms thicker, more robust biofilms.

Table 1: Characterization of Optimized Co-delivery Nanoparticles

| Parameter | Value (Mean ± SD) | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic Diameter | 185.4 ± 4.2 nm | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) |

| Polydispersity Index (PDI) | 0.11 ± 0.03 | DLS |

| Zeta Potential | -12.5 ± 1.8 mV | Laser Doppler Electrophoresis |

| CRISPR RNP EE% | 68.5 ± 3.1% | Fluorescence Spectroscopy (FITC-labeled RNP) |

| Antibiotic (Cipro) EE% | 82.7 ± 2.5% | HPLC-UV |

| Drug Loading (CRISPR) | 4.2 ± 0.3% (w/w) | Calculated from EE% |

| Drug Loading (Antibiotic) | 8.9 ± 0.5% (w/w) | Calculated from EE% |

Table 2: Synergistic Effect Assessment via Checkerboard Assay

| Treatment | MIC (µg/mL) for Planktonic | MIC (µg/mL) for Biofilm | FICI | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin alone | 0.5 | 32.0 | - | - |

| CRISPR-NP alone | 64.0* | 256.0* | - | - |

| Combination (Cipro+CRISPR-NP) | 0.125 | 4.0 | 0.375 | Synergy |

*MIC value for CRISPR-NP represents the nanoparticle concentration required for a 90% reduction in bacterial growth (MIC-90), as it is not directly bactericidal.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles via Double Emulsion (W/O/W)

- Prepare the inner aqueous phase: Dissolve 20 µg of Cas9-sgRNA RNP complex and 1 mg of Ciprofloxacin in 200 µL of nuclease-free water containing 0.1% (v/v) RNase inhibitor.

- Prepare the organic phase: Dissolve 50 mg of PLGA-PEG (50:50, 10kDa PLGA, 2kDa PEG) and 5 mg of cationic polymer (e.g., PEI, 10kDa) in 2 mL of dichloromethane (DCM).

- Form the primary emulsion (W1/O): Add the inner aqueous phase to the organic phase. Sonicate the mixture using a probe sonicator on ice (30% amplitude, 30 seconds pulse on, 10 seconds pulse off).

- Form the secondary emulsion (W1/O/W2): Pour the primary emulsion into 8 mL of a 2% (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution. Sonicate again on ice (30% amplitude, 60 seconds).

- Evaporate solvent: Stir the double emulsion overnight at room temperature to evaporate the organic solvent.

- Collect nanoparticles: Centrifuge the suspension at 20,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Wash the pellet twice with nuclease-free water to remove excess PVA and unencapsulated material.

- Resuspend: Resuspend the final nanoparticle pellet in 1 mL of PBS or a suitable storage buffer. Store at 4°C.

Protocol 2: Checkerboard Assay for Synergy Determination (FICI)

- Prepare antibiotic dilutions: In a 96-well plate, perform a 2-fold serial dilution of the Ciprofloxacin-loaded nanoparticles along the x-axis (e.g., 64 to 0.5 µg/mL).

- Prepare CRISPR-NP dilutions: Perform a 2-fold serial dilution of the CRISPR-only nanoparticles along the y-axis.

- Inoculate with bacteria: Add a standardized bacterial inoculum (~5 x 10^5 CFU/mL) to each well. Include growth and sterility controls.

- Incubate: Incubate the plate at 37°C for 18-24 hours.

- Determine MIC: Determine the MIC for each agent alone and in combination. The MIC is the lowest concentration that prevents visible growth.

- Calculate FICI:

- FIC (Cipro) = MIC of Cipro in combination / MIC of Cipro alone

- FIC (CRISPR) = MIC of CRISPR in combination / MIC of CRISPR alone

- FICI = FIC (Cipro) + FIC (CRISPR)

- Interpret: FICI ≤ 0.5 = Synergy; 0.5 < FICI ≤ 4.0 = No Interaction; FICI > 4.0 = Antagonism.

Visualizations

Experimental Workflow

Nanoparticle Action in Biofilm

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| PLGA-PEG Copolymer | Biodegradable polymer backbone forming the nanoparticle matrix. PEG provides "stealth" properties to reduce opsonization and improve stability. |

| Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | The functional CRISPR complex. Using pre-assembled RNP (rather than plasmid DNA) reduces off-target effects and allows for rapid, transient activity, which is crucial for targeting prokaryotes. |

| Ciprofloxacin HCl | A broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone antibiotic model. It acts on DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Its co-delivery with a CRISPR system targeting a resistance gene (e.g., gyrA mutation) demonstrates synergy. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI), 10kDa | A cationic polymer used to complex and condense the anionic RNP, protecting it from degradation and enhancing its loading into the hydrophobic nanoparticle core. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | A stabilizer and surfactant used in the double emulsion process to control nanoparticle size and prevent coalescence. |

| Biofilm-Penetrating Peptide (e.g., HYL1) | A peptide conjugated to the nanoparticle surface to facilitate diffusion through the dense, negatively charged extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) of the biofilm. |

| Eudragit L100-55 | A pH-sensitive polymer that can be incorporated into the nanoparticle to trigger antibiotic release specifically in the acidic microenvironment of a mature biofilm. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Cargo Size Limitations

Q1: Our AAV packaging efficiency for a CRISPR construct containing SpCas9 and multiple gRNAs is low. What are our primary options for smaller Cas variants?

A1: The primary smaller Cas variants suitable for AAV delivery are listed below. SaCas9 is the most established, while Cas12f systems are the smallest but may have different efficiency profiles.

| Cas Variant | Size (aa) | PAM Requirement | Notes for AAV Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|

| SaCas9 | 1,053 | NNGRRT | Well-characterized; sufficient space for single gRNA and promoter in a single AAV. |

| Nme2Cas9 | 1,082 | NNNNCC | Compact size with simple PAM; offers high fidelity. |

| CjCas9 | 984 | NNNVRYM | One of the smallest Cas9 orthologs; requires a complex PAM. |

| Cas12f (Cas14) | ~400-700 | T-rich | Extremely compact, allowing for complex cargo; lower editing efficiency in mammalian cells may require optimization. |

Q2: After switching to the smaller SaCas9, we observe no editing in our biofilm model. What are the potential causes?

A2:

- Promoter Incompatibility: The SaCas9 gene or its gRNA may be expressed from a promoter that is not functional in your specific bacterial strain within the biofilm. Verify promoter activity.

- gRNA Design: SaCas9 requires its own specific gRNA scaffold, which is different from the SpCas9 scaffold. Ensure you are using the correct sequence.

- PAM Availability: SaCas9 requires a NNGRRT PAM. Re-sequence your target site to confirm the presence of the correct PAM and that no mutations have occurred.

- Delivery Issue: Confirm successful transfection or transduction of the SaCas9 construct into the biofilm cells using a fluorescent marker or antibiotic resistance gene.

- Biofilm Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS): The EPS may hinder vector penetration or sequester the CRISPR machinery. Pre-treat biofilms with EPS-disrupting agents (e.g., DNase I, dispersin B) in a control experiment to test this.

Specificity and Fidelity Issues

Q3: We are concerned about off-target effects with SpCas9 in our chronic biofilm infection model. Which high-fidelity variants should we consider?

A3: High-fidelity variants contain mutations that reduce non-specific interactions with DNA. eSpCas9(1.1) and SpCas9-HF1 are leading choices.

| High-Fidelity Variant | Key Mutations | On-Target Efficiency (Relative to WT SpCas9) | Specificity Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| eSpCas9(1.1) | K848A, K1003A, R1060A | ~70-90% | Significant reduction in off-targets with minimal on-target impact. |

| SpCas9-HF1 | N497A, R661A, Q695A, Q926A | ~60-80% | Dramatically increased specificity, with a potential trade-off in on-target efficiency. |

| evoCas9 | M495V, Y515N, K526E, R661Q | ~50-70% | Evolved for high fidelity; robust performance across diverse targets. |

| HiFi Cas9 | R691A | ~80-95% | Excellent balance of high on-target efficiency and significantly reduced off-target effects. |

Q4: Our high-fidelity Cas9 variant (eSpCas9(1.1) shows significantly reduced on-target editing in biofilm-grown cells compared to planktonic cells. How can we troubleshoot this?

A4:

- Cellular State: Biofilm cells are often metabolically dormant and have altered membrane permeability, which can reduce the uptake and/or activity of CRISPR components. Consider using a constitutive promoter with high activity in slow-growing cells.

- gRNA Efficacy: Design and test 3-5 different gRNAs for the same target. gRNA secondary structure and accessibility can be differentially affected in the biofilm microenvironment.

- Delivery Timing: The efficiency of CRISPR delivery may vary with biofilm maturity. Try transducing/transfecting at different time points (e.g., 4h, 24h post-initiation of biofilm formation).