Nanoparticle-Mediated CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery: A Precision Strike Against Treatment-Resistant Biofilms

The convergence of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology with advanced nanoparticle delivery systems represents a paradigm shift in combating biofilm-associated antimicrobial resistance.

Nanoparticle-Mediated CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery: A Precision Strike Against Treatment-Resistant Biofilms

Abstract

The convergence of CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology with advanced nanoparticle delivery systems represents a paradigm shift in combating biofilm-associated antimicrobial resistance. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational science behind biofilm recalcitrance and the mechanistic synergy of CRISPR-nanoparticle hybrids. It details cutting-edge methodological approaches, including the design of lipid-based, polymeric, and metallic nanocarriers for efficient CRISPR component delivery. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting for optimization—tackling delivery inefficiency, off-target effects, and nanotoxicity—and validates the strategy through comparative analysis with conventional therapies. By synthesizing recent advances and persistent challenges, this review outlines a roadmap for translating these innovative platforms into next-generation, precision antimicrobial therapies.

The Biofilm Challenge and the CRISPR-Nanoparticle Synergy

Biofilms represent a predominant mode of bacterial life, characterized by structured microbial communities encased in a self-produced matrix of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) [1]. This matrix, which can constitute up to 85% of the biofilm volume, is a complex mixture of exopolysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA (eDNA), and lipids that provides critical structural integrity and protection [2] [1]. The transition from free-floating planktonic cells to a biofilm lifestyle confers a survival advantage, allowing bacteria to tolerate antimicrobial agents at concentrations up to 1000 times higher than those required to eliminate their planktonic counterparts [2] [3] [4]. This remarkable resilience makes biofilm-associated infections particularly challenging in clinical settings, contributing significantly to the global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis that causes an estimated 700,000 deaths annually [2] [4].

The architecture of a mature biofilm is not a random aggregation of cells but a highly organized, heterogeneous structure often described as a "fortress" [2] [5]. Advanced imaging techniques reveal a complex topography with microcolonies interspersed with water channels that facilitate nutrient distribution and waste removal [2]. This sophisticated organization creates diverse microenvironments with gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and pH, leading to metabolic heterogeneity among the embedded bacterial cells [2] [6]. Understanding this architectural complexity is fundamental to developing effective strategies, such as nanoparticle-delivered CRISPR-Cas9, to dismantle these microbial strongholds.

The Structural and Functional Organization of Biofilms

Stages of Biofilm Development

Biofilm formation is a dynamic, multi-stage process that transforms individual planktonic cells into a complex, coordinated community:

- Initial Attachment: Planktonic cells reversibly adhere to surfaces (both biotic and abiotic) through weak forces like van der Waals interactions and hydrophobic effects [5]. Surface proteins such as biofilm-associated protein (BAP), SasG, and fibronectin-binding proteins facilitate this initial contact [5].

- Irreversible Attachment: Cells anchor themselves more permanently by producing adhesins and beginning EPS secretion, transitioning from reversible to stable attachment [2] [5].

- Maturation I: Microcolonies form and develop into a three-dimensional structure. The EPS matrix matures, and water channels develop to circulate nutrients and signals [2] [5]. Quorum sensing (QS) mechanisms coordinate population-wide behavior through autoinducer molecules [5].

- Maturation II: The biofilm reaches its peak architectural complexity, with prominent water channels and specialized, metabolically heterogeneous subpopulations of bacteria, including dormant persister cells [2] [6].

- Dispersion: Controlled detachment of individual cells or clusters from the biofilm occurs, allowing bacteria to colonize new surfaces and begin the cycle anew [2] [5].

Composition and Role of the Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS)

The EPS matrix is the defining component of biofilm architecture and its primary defense mechanism. The composition and function of key EPS constituents are detailed below:

Table 1: Key Components of the Biofilm Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) Matrix

| EPS Component | Primary Composition | Functional Role in Biofilm Resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Exopolysaccharides | Alginate, cellulose, poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) | Forms a viscous physical barrier that limits antibiotic penetration and provides mechanical stability [2] [5]. |

| Proteins | Adhesins, amyloids, extracellular enzymes | Strengthens structural integrity and facilitates adhesion to surfaces and other cells [2] [5]. |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | DNA from lysed bacterial cells | Contributes to matrix stability, chelates cationic antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), and facilitates horizontal gene transfer [2] [5]. |

| Lipids & Other Polymers | Surfactants, phospholipids | Modifies surface properties, contributes to hydrophobicity, and can act as a nutrient source [6]. |

Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Biofilms

The protective nature of biofilms arises from a confluence of physical, physiological, and genetic mechanisms that operate simultaneously to defeat antimicrobial challenges.

Physical and Physiological Barriers

The EPS matrix acts as a dual physical barrier, significantly slowing the diffusion of antimicrobial agents into the biofilm's deeper layers while simultaneously binding and neutralizing these molecules, preventing them from reaching their cellular targets [2] [4] [5]. This limited penetration is a cornerstone of biofilm-associated tolerance.

Within the mature biofilm, environmental gradients (e.g., of oxygen and nutrients) create heterogeneous microenvironments [2] [6]. Bacteria in the inner core often enter a slow-growing or dormant state due to nutrient limitation. Since most conventional antibiotics target active cellular processes like cell wall synthesis or protein production, these dormant cells exhibit dramatically increased tolerance [2] [4]. A subpopulation of these, known as persister cells, can survive high-dose antibiotic exposure despite being genetically identical to susceptible cells, often leading to infection recurrence [6].

Genetic and Adaptive Resistance Mechanisms

The close proximity of cells within the biofilm matrix drastically enhances the efficiency of Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT) via conjugation, transformation, or transduction [2] [6]. This turns biofilms into "hotspots" for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes, such as those encoding for beta-lactamase enzymes or efflux pumps, accelerating the development of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens [2] [6].

Furthermore, biofilm communities utilize a sophisticated cell-to-cell communication system called Quorum Sensing (QS). Bacteria release and detect signaling molecules known as autoinducers; when a critical threshold concentration is reached, population-wide changes in gene expression are triggered [5]. QS regulates key biofilm behaviors, including EPS production, virulence factor secretion, and metabolic coordination, making it a master regulator of biofilm maintenance and pathogenicity [7] [5].

Table 2: Primary Mechanisms of Biofilm-Associated Antimicrobial Resistance

| Resistance Mechanism | Description | Impact on Antibiotic Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Diffusion Barrier | EPS matrix binds and reters diffusion of antimicrobials. | Reduces antibiotic concentration reaching inner cells; can require 10-1000x higher doses [2] [4]. |

| Metabolic Heterogeneity | Gradients create zones of slow/dormant bacterial growth. | Antibiotics targeting active processes (e.g., β-lactams) become ineffective against dormant cells [2] [6]. |

| Horizontal Gene Transfer | Facilitates plasmid-borne resistance gene exchange. | Rapidly spreads resistance determinants (e.g., bla, mecA, ndm-1) across the population [2] [6]. |

| Persister Cell Formation | A small subpopulation enters a dormant, tolerant state. | Survives high-dose antibiotic treatment, leading to chronic infection relapse [2] [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Biofilm Analysis

Protocol: Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) for 3D Biofilm Architecture

Purpose: To visualize and quantitatively analyze the three-dimensional structure, biovolume, and spatial organization of live biofilms.

Materials:

- Strain(s): Biofilm-forming bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus)

- Growth Medium: Appropriate broth (e.g., Tryptic Soy Broth, LB Broth)

- Substrate: Sterile glass-bottom culture dishes or specialized coverslips

- Vital Fluorescent Stains: SYTO 9 (for live cell nucleic acids), Propidium Iodide (for dead cell nucleic acids), ConA-TRITC (for polysaccharides)

- Imaging System: Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope with appropriate laser lines and filters

Procedure:

- Biofilm Growth: Inoculate bacteria in culture medium and incubate with glass substrate under static or flow conditions for desired time (e.g., 24-72 hours) to form mature biofilms.

- Staining Preparation: Prepare staining solution in buffer. A common live/dead stain uses a 1:1 mixture of SYTO 9 and Propidium Iodide.

- Staining Protocol: Gently rinse the biofilm to remove non-adherent cells. Apply the staining solution to completely cover the biofilm. Incubate in the dark at room temperature for 15-30 minutes.

- Image Acquisition: Gently rinse the stained biofilm to remove excess dye. Image immediately using CLSM. For SYTO 9, use an argon laser (excitation ~488 nm) and detect emission at 500-550 nm.

- 3D Reconstruction & Analysis: Collect Z-stack images at regular intervals (e.g., 1 µm steps) through the entire biofilm depth. Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with BiofilmQ plugin) to calculate biovolume, thickness, surface area, and roughness coefficient.

Protocol: Microtiter Plate Assay for Anti-biofilm Compound Screening

Purpose: To quantitatively assess the efficacy of novel anti-biofilm agents (e.g., CRISPR-NP formulations) in inhibiting biofilm formation or eradicating pre-formed biofilms.

Materials:

- Strain(s): Biofilm-forming bacteria

- Equipment: 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plate, plate reader (OD600)

- Reagents: Growth broth, PBS, Crystal Violet stain (0.1% w/v), acetic acid (33% v/v)

- Test Formulations: CRISPR-Cas9 nanoparticle complexes, control nanoparticles, free antibiotics

Procedure:

- Biofilm Formation Assay:

- Dilute an overnight bacterial culture in fresh medium to ~1x10^6 CFU/mL.

- Dispense 100 µL per well into the microtiter plate. Include medium-only wells as negative controls.

- Add 100 µL of serially diluted test formulations to treatment wells.

- Incubate statically for 24-48 hours at appropriate temperature.

Biofilm Eradication Assay:

- First, incubate the bacterial inoculum in wells for 24 hours to allow mature biofilms to form.

- Carefully aspirate the planktonic culture and gently wash wells with PBS.

- Add fresh medium containing the test formulations to the pre-formed biofilms.

- Incubate for an additional 24 hours.

Biofilm Quantification (Crystal Violet Staining):

- Aspirate contents of wells and wash gently with PBS to remove non-adherent cells.

- Air-dry the plate for 30-60 minutes.

- Add 125 µL of 0.1% Crystal Violet to each well, stain for 15 minutes.

- Wash plate thoroughly under running tap water to remove excess stain.

- Add 125 µL of 33% acetic acid to solubilize the stain bound to the biofilm.

- Measure the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) using the plate reader.

Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of biofilm inhibition or eradication relative to untreated control wells. Perform statistical analysis on replicate wells (typically n=6-8).

Pathway Visualization: Biofilm Development and Disruption Strategies

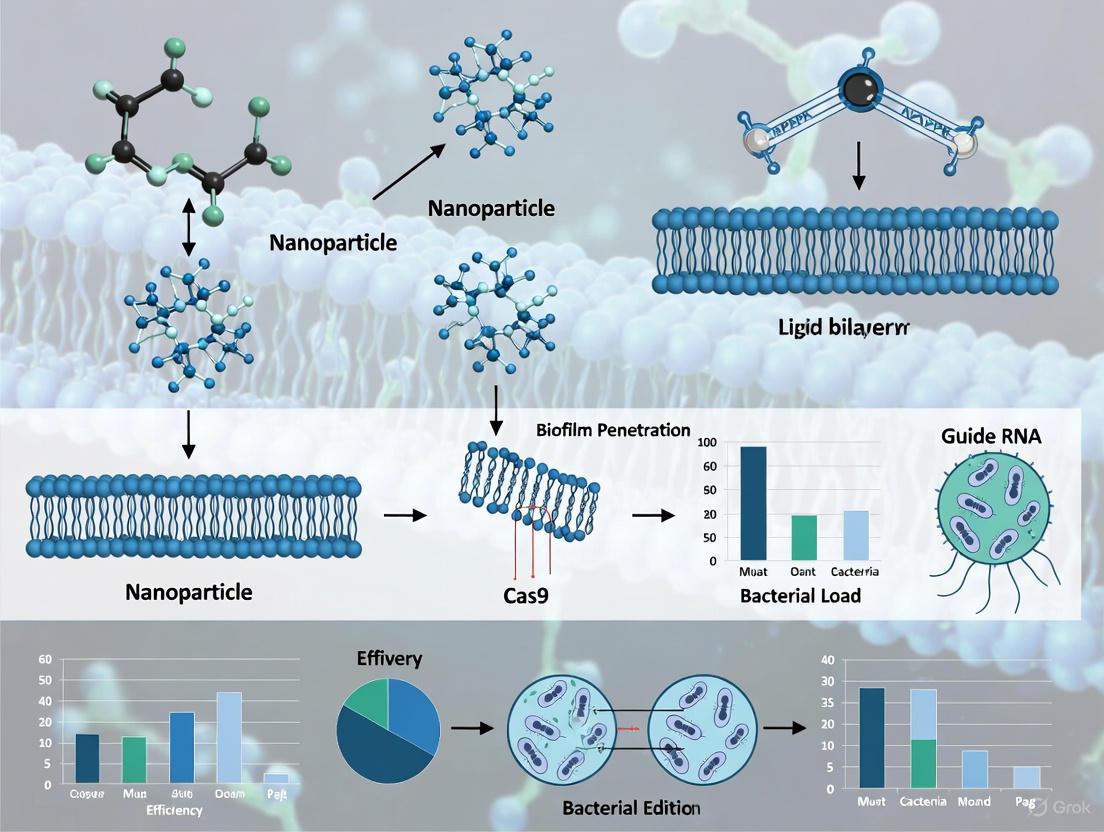

Diagram 1: Biofilm development cycle and NP-CRISPR disruption strategies. The diagram illustrates the staged process of biofilm formation and the key resistance mechanisms that emerge. It also maps how nanoparticle-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 strategies target these specific mechanisms for precise biofilm disruption.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating NP-Delivered CRISPR-Cas9 Anti-biofilm Strategies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid System | Expresses Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA) for targeted gene editing. | Select promoters functional in target species (e.g., P. aeruginosa). gRNA must be designed against specific biofilm genes (e.g., pelA, pslD for EPS, lasI for QS) [2] [7]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Biocompatible nanocarriers for encapsulating and delivering CRISPR payload. | Formulations with cationic lipids enhance complexation with nucleic acids. LNPs have demonstrated >90% reduction in P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass in vitro [2] [8]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Inorganic nanocarriers for CRISPR component delivery. | Facile surface functionalization with thiolated biomolecules. AuNP-CRISPR hybrids show ~3.5x higher editing efficiency than non-carrier systems [2] [8]. |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors (QSIs) | Small molecules (e.g., AHL analogs) or natural compounds (e.g., curcumin) that disrupt bacterial communication. | Used as synergistic agents with CRISPR-NP therapy. Validate efficacy via reporter strain assays (e.g., lasB-gfp) [6] [5]. |

| EPS Degrading Enzymes | Enzymes such as Dispersin B (glycosidase) or DNase I to disrupt the biofilm matrix. | Pre-treatment with enzymes enhances NP penetration into biofilms. Use in combination therapies to weaken the EPS barrier [6]. |

| Metabolic Stains (e.g., CTC, XTT) | To assess bacterial metabolic activity and viability within biofilms post-treatment. | Differentiates between metabolic states; crucial for evaluating effects on dormant persister cells that standard CFU counts may miss [1]. |

| Anti-biofilm Peptides | Synthetic or natural antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that disrupt membranes. | Co-delivery with CRISPR-NPs for a multi-mechanism attack. Select peptides with proven activity against target biofilm species [6]. |

Biofilms are structured communities of microbial cells enclosed in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) and adherent to biotic or abiotic surfaces [9]. This aggregated lifestyle represents the predominant mode of bacterial growth in nature and clinical settings, contributing significantly to the challenge of treating bacterial infections [10]. The transition from free-floating planktonic cells to surface-attached biofilms involves major physiological changes that confer enhanced tolerance to antimicrobial agents and host immune responses [10] [11].

The clinical impact of biofilm-associated infections is substantial, contributing to chronic infections that are notoriously difficult to eradicate [10]. Biofilms are implicated in numerous medical scenarios, including infections of indwelling medical devices (e.g., catheters, prosthetic joints), chronic wounds, cystic fibrosis lung infections, and infective endocarditis [10] [12]. The persistent nature of these infections results in significant morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs, with an estimated nearly $300 billion spent annually globally on managing biofilm-associated wound infections alone [10]. Understanding the mechanisms underlying biofilm-mediated resistance is therefore crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies.

Physical and Structural Barrier Mechanisms

The Extracellular Polymeric Substance Matrix as a Physical Barrier

The extracellular matrix is a defining characteristic of biofilms, constituting over 90% of the biofilm mass and serving as a primary defense mechanism [10] [12]. This complex matrix comprises various biopolymers, including polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (eDNA), which collectively create a formidable physical and chemical barrier to antimicrobial penetration [10] [11].

Table 1: Major Components of Biofilm Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) Matrix and Their Protective Functions

| EPS Component | Chemical Composition | Protective Function in Biofilms |

|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | Poly-N-acetylglucosamine, alginate, cellulose | Structural scaffolding, cation sequestration, barrier formation |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | DNA from lysed cells | Structural integrity, cation chelation, antibiotic binding |

| Proteins | Adhesins, amyloids, enzymes | Structural stability, enzymatic degradation of antimicrobials |

| Lipids | Phospholipids, surfactants | Hydrophobic barriers, surface modification |

The matrix hinders antibiotic penetration through multiple mechanisms. Some antibiotics form complexes with matrix components or are degraded by matrix-associated enzymes, effectively reducing the concentration reaching bacterial cells [10]. Positively charged aminoglycosides, for instance, bind to negatively charged eDNA in the matrix, significantly slowing antibiotic penetration [10]. In chronic infections such as those in the cystic fibrosis lung, eDNA produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa combines with host-derived DNA to form a physical shield that protects the biofilm from tobramycin and host immune cells [10]. Similarly, host neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) can surround ocular P. aeruginosa biofilms, creating an additional barrier that limits antibiotic access while containing bacterial dissemination [10].

Biofilm Lifecycle and Structural Heterogeneity

Biofilm development follows a defined lifecycle comprising distinct stages: initial attachment, irreversible attachment, micro-colony formation, maturation, and dispersion [10] [9]. This progression creates a heterogeneous three-dimensional architecture characterized by microcolonies interspersed with water channels that facilitate nutrient distribution and waste removal [13] [9].

The structural heterogeneity of mature biofilms creates diverse microenvironments with gradients of nutrients, oxygen, pH, and metabolic waste products [13] [11]. This spatial organization significantly influences microbial physiology and contributes to variations in antimicrobial susceptibility within different biofilm regions [13]. Cells in the inner layers often experience nutrient and oxygen limitations, leading to reduced metabolic activity and growth rates that enhance antimicrobial tolerance [11] [9].

Diagram 1: Biofilm Development Lifecycle and Structural Features. The diagram illustrates the sequential stages of biofilm formation and key structural developments that contribute to antimicrobial resistance.

Physiological and Genetic Resistance Mechanisms

Metabolic Heterogeneity and Persister Cell Formation

Within biofilms, bacterial populations exhibit significant metabolic heterogeneity, with subpopulations of cells existing in various physiological states [13] [12]. Persister cells represent a small subset of metabolically dormant bacterial cells that exhibit exceptional tolerance to antimicrobial agents without undergoing genetic resistance mutations [12]. These phenotypic variants can survive high concentrations of antibiotics by reducing their metabolic activity and growth rates, effectively minimizing the corrupting action of bactericidal antibiotics that typically target active cellular processes [12].

The formation of persister cells is controlled by bacterial growth phases and environmental stress factors [12]. While persisters constitute only a small fraction of exponentially growing cells, their proportion increases significantly during stationary phase and in mature biofilms where nutrient limitations induce metabolic dormancy [12]. When antibiotic pressure is removed, these dormant persister cells can resuscitate and repopulate the biofilm, leading to recurrent infections and treatment failures [12].

The molecular mechanisms underlying persistence involve bacterial stress response pathways, particularly those activated by DNA damage [12]. Environmental stressors encountered during infection activate these pathways, upregulating DNA repair functions and facilitating survival under harsh conditions, including antibiotic exposure [12]. This "neither-grow-nor-die" state enables bacterial pathogens to withstand both antimicrobial treatment and host immune responses, contributing significantly to chronic and relapsing infections [12].

Enhanced Horizontal Gene Transfer and Resistance Gene Acquisition

The dense, structured environment of biofilms facilitates efficient exchange of genetic material between bacterial cells through horizontal gene transfer (HGT), accelerating the development and dissemination of antibiotic resistance [10] [11]. The close cell-to-cell contact within the biofilm matrix enhances conjugation efficiency, while the presence of extracellular DNA in the matrix provides a reservoir for natural transformation [10] [12].

Table 2: Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Biofilm Communities

| Resistance Mechanism | Process | Impact on Antibiotic Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Restricted Penetration | Physical barrier of EPS matrix limiting antibiotic diffusion | Reduced antibiotic concentration reaching interior cells |

| Metabolic Dormancy | Reduced growth rate and metabolic activity of persister cells | Decreased efficacy of bactericidal antibiotics |

| Horizontal Gene Transfer | Plasmid exchange and transformation within dense biofilm communities | Dissemination of resistance genes across population |

| Efflux Pump Overexpression | Upregulation of multidrug efflux systems | Active extrusion of antibiotics from bacterial cells |

| Enzymatic Inactivation | Production of antibiotic-modifying enzymes (e.g., β-lactamases) | Direct degradation or modification of antibiotic molecules |

Biofilms not only promote the acquisition of resistance genes but also provide a protective environment for the emergence and selection of resistant mutants [12]. Studies using E. coli biofilms have demonstrated elevated mutation rates in response to antibiotic pressure, with mutations occurring in genes such as sbmA (encoding an inner membrane peptide transporter) and fusA (encoding elongation factor G) following treatment with amikacin [12]. Similarly, in cystic fibrosis patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infections, repeated antibiotic exposure selects for high-persister (hip) mutants with enhanced tolerance phenotypes, demonstrating the direct correlation between persister formation and treatment failure [12].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Biofilm Resistance

Standardized Biofilm Cultivation and Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Standard Workflow for Biofilm Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. The protocol outlines key steps for evaluating anti-biofilm efficacy of novel therapeutic agents.

Protocol 4.1.1: Microtiter Plate Biofilm Formation Assay

Purpose: To establish reproducible in vitro biofilm models for evaluating antimicrobial susceptibility and resistance mechanisms.

Materials:

- Bacterial strains: Relevant clinical isolates or laboratory strains (e.g., P. aeruginosa, S. aureus)

- Growth media: Tryptic soy broth (TSB), Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, or specific media optimized for biofilm formation

- Surfaces: Polystyrene microtiter plates, glass coupons, or relevant biomedical materials

- Staining reagents: Crystal violet (0.1% w/v), safranin, or fluorescent nucleic acid stains (SYTO9)

- Equipment: Microplate reader, confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM), scanning electron microscope (SEM)

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow bacterial cultures to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5) and dilute to approximately 10^6 CFU/mL in appropriate growth medium.

- Surface Conditioning: For medical material testing, precondition surfaces with relevant biological fluids (e.g., plasma, serum) to mimic in vivo conditions [10].

- Biofilm Development: Add 200 μL bacterial suspension per well of 96-well plate. Incubate statically for 24-48 hours at optimal growth temperature (e.g., 37°C for human pathogens).

- Maturation Monitoring: Monitor biofilm development at 4-hour intervals using optical density measurements or microscopy to establish growth kinetics.

- Biofilm Quantification:

- Remove planktonic cells by gently washing wells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Fix biofilms with 99% methanol for 15 minutes.

- Stain with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 minutes.

- Wash excess stain and solubilize bound stain with 33% acetic acid.

- Measure absorbance at 570-600 nm using microplate reader.

- Structural Analysis: For CLSM imaging, stain with LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit according to manufacturer's instructions and visualize using appropriate laser settings.

Quality Control: Include known strong and weak biofilm-forming strains as positive and negative controls. Perform technical replicates (n≥3) and biological replicates (n≥3) for statistical analysis.

Protocol for Evaluating CRISPR-Based Biofilm Disruption

Protocol 4.2.1: Nanoparticle-Mediated CRISPR Delivery Against Biofilms

Purpose: To assess efficacy of CRISPR-Cas9 systems delivered via nanoparticle carriers for targeted disruption of biofilm-related genes.

Materials:

- CRISPR Components: Cas9 nuclease (as plasmid, mRNA, or ribonucleoprotein), guide RNAs targeting biofilm-associated genes (e.g., pelA, pslD, alg8 for polysaccharide synthesis; lasR, rhlR for quorum sensing)

- Nanoparticle Carriers: Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), gold nanoparticles, or polymeric nanoparticles optimized for bacterial delivery

- Biofilm Models: Established 24-48 hour biofilms of target pathogens in appropriate in vitro systems

- Assessment Tools: qPCR for gene expression, confocal microscopy for structural analysis, colony counting for viability assessment

Methodology:

- CRISPR-Nanoparticle Formulation:

- Complex CRISPR-Cas9 components (RNP preferred for immediate activity) with cationic lipid or polymer nanoparticles at optimal N:P ratios.

- Characterize nanoparticle size (target 50-200 nm), zeta potential, and encapsulation efficiency.

- Validate gene editing efficiency in planktonic cultures before biofilm application.

Biofilm Treatment:

- Establish mature biofilms (48-72 hours) in flow cell systems or on relevant substrates.

- Apply CRISPR-nanoparticle formulations at varying concentrations (e.g., 0.1-10 μg/mL CRISPR component).

- Include control treatments: naked CRISPR, nanoparticles alone, and scrambled gRNA complexes.

- For flow cells, maintain constant flow (0.2-0.5 mm/s) during treatment to mimic physiological conditions.

Efficacy Assessment:

- Biomass Quantification: Measure biofilm biomass pre- and post-treatment using crystal violet staining or SYTOX Green nucleic acid staining.

- Viability Analysis: Dissociate biofilms by sonication and plate serial dilutions for CFU enumeration.

- Structural Integrity: Assess biofilm architecture via CLSM and COMSTAT analysis.

- Gene Editing Confirmation: Extract biofilm DNA and perform targeted sequencing to verify specific gene disruption.

- Resistance Gene Elimination: Monitor reduction in antibiotic resistance gene prevalence (e.g., bla, mecA, ndm-1) via qPCR [13].

Optimization Notes:

- Lipid nanoparticle formulations have demonstrated >90% reduction in P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass in vitro when targeting essential biofilm genes [13].

- Gold nanoparticle carriers can enhance editing efficiency up to 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems [13].

- Co-delivery with conventional antibiotics may produce synergistic effects—test combinations with tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, or meropenem based on target pathogen.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biofilm and CRISPR-Cas9 Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilm Matrix Stains | Crystal violet, SYTO9, Calcofluor white, Congo red | Biofilm quantification and visualization | Differential staining of matrix components; compatibility with fixation methods |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | SpCas9, SaCas9, AsCas12a; plasmid, mRNA, or RNP formats | Targeted gene disruption in biofilm-associated genes | RNP format reduces off-target effects; consider PAM requirements for target selection |

| Nanoparticle Delivery Systems | Cationic lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), gold nanoparticles, chitosan nanoparticles | Delivery of CRISPR components through biofilm matrix | Size (50-200 nm) and surface charge critical for penetration; bacterial toxicity screening required |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors | Furanones, ambuic acid, triclosan (research use) | Disruption of cell-to-cell signaling in biofilms | Specificity for pathogen QS systems; potential synergy with antimicrobials |

| Biofilm Dispersal Agents | D-amino acids, dispersin B, DNase I, glycoside hydrolases | Induction of biofilm dispersal for enhanced antimicrobial penetration | Enzyme stability in biofilm environment; potential immune activation in vivo |

| Metabolic Activity Probes | Resazurin, CTC, SYTOX Green, propidium iodide | Assessment of bacterial viability and metabolic status within biofilms | Distinction between bactericidal and bacteriostatic effects; penetration depth limitations |

Integration with Nanoparticle-Delivered CRISPR-Cas9 Therapeutics

The elucidated mechanisms of biofilm-mediated resistance directly inform the development of nanoparticle-delivered CRISPR-Cas9 strategies for biofilm eradication. The physical barrier function of the EPS matrix necessitates nanoparticle carriers capable of effective penetration and distribution throughout the biofilm architecture [13] [9]. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and gold nanoparticles have demonstrated particular promise, achieving significant biofilm biomass reduction (>90% in P. aeruginosa models) and enhanced gene-editing efficiency (3.5-fold improvement compared to non-carrier systems) [13].

The metabolic heterogeneity and persister cell populations within biofilms highlight the importance of targeting essential genes that are required for both active and dormant cell survival [12]. CRISPR-Cas9 systems can be designed to target core cellular processes, resistance genes (e.g., bla, mecA, ndm-1), or biofilm-specific genes (e.g., quorum sensing regulators, matrix biosynthesis genes) to overcome phenotypic tolerance [13] [11]. The programmable specificity of CRISPR systems enables targeted elimination of pathogenic species while preserving commensal microbiota, addressing a significant limitation of broad-spectrum antibiotics [13] [14].

Advanced delivery strategies exploit the biofilm microenvironment for enhanced therapeutic efficacy. Nanoparticles can be engineered with enzyme-responsive coatings that degrade upon encounter with matrix components (e.g., DNase-functionalized particles for eDNA-rich matrices), facilitating deeper penetration [13] [9]. Similarly, quorum-sensing inhibitors can be co-delivered with CRISPR components to disrupt cell-cell communication and sensitize biofilms to conventional antibiotics [11] [9].

The integration of CRISPR-based antimicrobials with nanoparticle delivery systems represents a paradigm shift in addressing biofilm-mediated resistance, moving beyond growth inhibition to targeted genetic disruption of resistance mechanisms and biofilm integrity. As these technologies advance toward clinical application, understanding the fundamental resistance mechanisms outlined in this article will continue to guide the development of effective anti-biofilm strategies.

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) proteins constitute an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes that protects bacteria from foreign genetic elements such as viruses and plasmids [15]. First identified in E. coli in 1987 and later characterized as a bacterial defense mechanism, this system was repurposed into a revolutionary gene-editing tool following key discoveries by Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, who demonstrated that the system could be programmed for precise DNA cleavage [15]. This breakthrough earned them the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and opened unprecedented possibilities for precision genome modification [15].

The significance of CRISPR-Cas9 technology extends across multiple disciplines, including microbiology and therapeutic development. Within the context of combating biofilm-mediated antibiotic resistance, CRISPR-Cas9 offers a novel approach to target specific genetic elements that confer survival advantages to pathogenic bacteria [13] [11]. When integrated with nanoparticle-mediated delivery, this technology presents a promising strategy for overcoming the physical and biological barriers posed by biofilm matrices, potentially revolutionizing treatment approaches for persistent infections [13] [8].

Molecular Mechanisms of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

Core Components and Their Functions

The CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two fundamental components that work in concert to achieve targeted DNA cleavage: the Cas9 nuclease and the guide RNA (gRNA) [13] [15].

Cas9 Nuclease: This enzyme acts as molecular scissors, creating double-strand breaks in DNA at precise locations specified by the gRNA [13]. The Cas9 protein contains multiple domains, including the HNH and RuvC nuclease domains, each responsible for cleaving one DNA strand [15].

Guide RNA (gRNA): This synthetic RNA molecule is a fusion of two natural RNA components: CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA) [15]. The gRNA includes a ~20 nucleotide sequence that is complementary to the target DNA site, directing Cas9 to this specific genomic locus through base-pairing [15].

Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM): This short (2-6 base pair) DNA sequence adjacent to the target site is essential for Cas9 recognition and binding [15]. The PAM sequence varies depending on the bacterial source of the Cas9 protein, with the most commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 requiring a 5'-NGG-3' PAM [15].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these core components and the sequential process of DNA targeting and cleavage:

Functional Mechanism: From Target Recognition to DNA Cleavage

The CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism operates through a sequential process that ensures precise targeting of specific genetic sequences. Initially, the Cas9 nuclease forms a complex with the gRNA, creating a ribonucleoprotein complex that surveys the genome for potential target sites [15]. This surveillance is guided by the gRNA's complementary region, which base-pairs with matching DNA sequences. However, Cas9 only initiates binding when it recognizes a compatible PAM sequence immediately adjacent to the target site [15]. This PAM requirement serves as a safeguard mechanism, preventing unintended cleavage of the bacterial CRISPR locus itself, which lacks these adjacent motifs [15].

Once the Cas9-gRNA complex identifies a target sequence with the appropriate PAM, it undergoes a conformational change that activates its nuclease domains. The HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA, while the RuvC domain cleaves the opposite strand, resulting in a precise double-strand break [15]. This break triggers the cell's natural DNA repair mechanisms—either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR)—which can be harnessed to introduce specific genetic modifications, such as gene knockouts, insertions, or corrections [15].

Quantitative Performance Metrics of CRISPR-Cas9 Systems

The efficacy of CRISPR-Cas9 systems varies depending on delivery method, target organism, and experimental conditions. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies, particularly those relevant to antibacterial applications:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of CRISPR-Cas9 Systems in Antimicrobial Applications

| System Configuration | Target Organism/Application | Efficiency Metrics | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomal Cas9 Formulations | Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm | >90% reduction in biofilm biomass [13] | In vitro culture systems [13] |

| Gold Nanoparticle Carriers | Bacterial gene editing | 3.5× enhancement in editing efficiency compared to non-carrier systems [13] | Laboratory strains [13] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 with Antibiotic Co-delivery | Biofilm-associated infections | Superior biofilm disruption via synergistic effects [13] | In vitro models [8] |

Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

Implementing CRISPR-Cas9 technology requires specific reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential components for establishing CRISPR-Cas9 workflows in a research setting, with particular emphasis on applications against bacterial biofilms:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Target DNA cleavage | Wild-type S. pyogenes Cas9, codon-optimized variants [15] |

| Guide RNA Components | Target recognition and Cas9 guidance | Synthetic crRNA:tracrRNA duplex or single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [15] |

| Nanoparticle Delivery Systems | Enhanced cellular delivery and stability | Liposomal nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles [13] |

| Antibiotic Resistance Genes | Selection of successfully transformed cells | Kanamycin, ampicillin, or other relevant resistance markers [11] |

| Bacterial Biofilm Models | Experimental testing of anti-biofilm efficacy | ESKAPE pathogen biofilms (P. aeruginosa, S. aureus) [9] |

| PAM-compatible Plasmids | Target sequence validation and screening | Vectors containing appropriate PAM sequences (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) [15] |

Application Notes: CRISPR-Cas9 for Biofilm Eradication

Targeting Strategic Genetic Elements in Biofilm-Forming Bacteria

CRISPR-Cas9 can be programmed to disrupt specific genetic targets that are crucial for biofilm formation and maintenance in pathogenic bacteria. The most promising targets include:

Antibiotic Resistance Genes: CRISPR-Cas9 can be designed to precisely cleave and disrupt genes conferring resistance to conventional antibiotics, such as beta-lactamases or vancomycin resistance genes, potentially resensitizing bacteria to existing treatments [13] [11].

Quorum Sensing Pathways: Bacterial cell-to-cell communication systems (quorum sensing) regulate biofilm formation and virulence factor production. Targeting quorum sensing genes (e.g., lasI, rhlI in P. aeruginosa) can disrupt biofilm development without directly killing bacteria, potentially reducing selective pressure for resistance [13].

Biofilm-Specific Regulatory Genes: Genes encoding master regulators of biofilm formation, such as those controlling production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), represent valuable targets for preventing biofilm maturation and stability [11].

The following experimental workflow outlines a standardized protocol for developing and testing CRISPR-Cas9 systems against bacterial biofilms:

Protocol: gRNA Design and Validation for Anti-Biofilm Applications

Objective: Design and validate guide RNAs targeting antibiotic resistance genes in ESKAPE pathogens.

Materials:

- Bacterial genomic DNA or synthetic target sequences

- gRNA design software (e.g., CRISPRscan, Benchling)

- In vitro transcription kit for gRNA production

- Purified Cas9 nuclease

- Target DNA plasmids containing resistance genes

Procedure:

- Target Selection: Identify 20-nucleotide sequences adjacent to PAM sites (5'-NGG-3') within your target gene (e.g., mecA in S. aureus or blaNDM-1 in K. pneumoniae).

- Specificity Screening: Use BLAST analysis to verify target uniqueness and minimize off-target effects.

- gRNA Synthesis: Transcribe gRNAs using T7 RNA polymerase-based in vitro transcription.

- In Vitro Cleavage Assay:

- Set up 20 μL reaction containing: 100 ng target plasmid, 50 nM Cas9 nuclease, 50 nM gRNA, and reaction buffer.

- Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Analyze cleavage efficiency by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Validation: Successful cleavage is confirmed by appearance of expected DNA fragment sizes.

Troubleshooting Note: If cleavage efficiency is low, redesign gRNAs targeting different regions of the same gene, as chromatin accessibility and local DNA structure can impact efficacy.

Protocol: Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 to Biofilms

Objective: Formulate CRISPR-Cas9 components in nanoparticle carriers and evaluate biofilm penetration and editing efficiency.

Materials:

- Cationic liposomes or gold nanoparticles

- Purified Cas9 protein or Cas9 expression plasmid

- Validated gRNA

- Biofilm-forming bacterial strains

- Confocal microscopy supplies for visualization

Procedure:

- Nanoparticle Formulation:

- For liposomal preparations: Mix cationic lipids with CRISPR components at optimal N:P ratio (typically 5:1 to 10:1).

- For gold nanoparticles: Conjugate thiol-modified gRNA to AuNPs, then complex with Cas9 protein.

- Characterize nanoparticle size (target: 50-200 nm) and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering.

Biofilm Treatment:

- Grow 24-48 hour mature biofilms in flow cells or 96-well plates.

- Apply nanoparticle formulations at predetermined concentrations.

- Include appropriate controls (untreated, empty nanoparticles, free CRISPR).

Penetration Assessment:

- Label nanoparticles with fluorescent dyes (e.g., Cy5 for gRNA, FITC for Cas9).

- Monitor biofilm penetration using confocal laser scanning microscopy at 2, 4, 6, and 24 hours post-treatment.

- Generate Z-stack images to visualize depth of penetration.

Efficacy Evaluation:

- Quantify biofilm biomass using crystal violet staining.

- Assess bacterial viability via colony-forming unit counts.

- Analyze target gene modification efficiency through sequencing.

Technical Note: Optimization of nanoparticle surface properties (e.g., PEGylation, targeting ligand conjugation) may enhance biofilm penetration and cellular uptake.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 technology with advanced nanoparticle delivery systems represents a paradigm shift in our approach to combating biofilm-associated infections. By leveraging the fundamental mechanisms of bacterial immunity, researchers can now develop highly specific antimicrobial strategies that target the genetic underpinnings of antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation [13] [8] [11].

While significant progress has been made in demonstrating the efficacy of these systems in vitro, translation to clinical applications requires addressing several challenges. These include optimizing delivery efficiency to biofilm-embedded bacteria, minimizing potential off-target effects, and ensuring long-term safety [15]. Future research directions should focus on developing more sophisticated nanoparticle platforms that can navigate the complex biofilm microenvironment, creating Cas variants with enhanced specificity, and exploring combinatorial approaches that integrate CRISPR with conventional antibiotics for synergistic effects [13].

The protocols and application notes presented herein provide a foundation for researchers exploring CRISPR-Cas9 based approaches within the broader context of nanoparticle-mediated delivery for biofilm eradication. As this field continues to evolve, these fundamental principles will serve as a roadmap for developing next-generation antimicrobial therapies that address the pressing global challenge of antibiotic resistance.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has emerged as a revolutionary tool for precision genome modification, offering targeted disruption of antibiotic resistance genes, quorum sensing pathways, and biofilm-regulating factors within bacterial populations [13]. However, the clinical application of CRISPR-based antibacterials faces significant challenges, particularly in achieving efficient delivery and stability within complex bacterial communities such as biofilms [13]. Biofilms, which are structured communities of microorganisms embedded in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), can exhibit up to 1000-fold greater tolerance to antibiotics compared to their planktonic counterparts [13]. This protective matrix limits the penetration of antimicrobial agents, enhances horizontal gene transfer, and enables bacterial survival in hostile environments, making conventional therapies largely ineffective [13].

The core delivery problem encompasses multiple barriers: the negatively charged EPS matrix repels negatively charged genetic material, extracellular nucleases degrade CRISPR components before cellular uptake, and the varied metabolic states of bacterial cells (including persister cells) further reduce editing efficiency [13] [16]. Overcoming these hurdles requires innovative delivery strategies that can protect the CRISPR payload, facilitate penetration through the biofilm architecture, and ensure efficient intracellular delivery to bacterial cells. Nanoparticles present an innovative solution, serving as effective carriers for CRISPR-Cas9 components while exhibiting intrinsic antibacterial properties [13]. These nanocarriers can enhance CRISPR delivery by improving cellular uptake, increasing target specificity, and ensuring controlled release within biofilm environments [13].

Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery Strategies

Various nanoparticle platforms have been engineered to address the distinct challenges of delivering CRISPR-Cas9 components through biofilm matrices and into bacterial cells. These systems can be broadly categorized based on their composition and properties, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Nanoparticle Platforms for CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Against Biofilms

| Nanoparticle Type | Key Advantages | CRISPR Payload Format | Reported Efficacy | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid-Based Nanoparticles | High biocompatibility, enhanced biofilm penetration [13] | Plasmid DNA, RNP [13] [17] | >90% reduction in P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass [13] | Potential endosomal degradation, variable efficiency across species [17] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Easy surface functionalization, high delivery efficiency [13] [17] | RNP, DNA [17] | 3.5-fold increase in editing efficiency [13] | Potential toxicity at high concentrations [17] |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | Controlled release, high biocompatibility, low cytotoxicity [17] [16] | Plasmid DNA, mRNA, RNP [17] [16] | Effective resensitization to antibiotics [16] | Relatively lower delivery efficiency [17] |

| Hybrid Systems | Synergistic effects, multi-functional capabilities [13] | Various formats with antibiotic co-delivery [13] | Superior biofilm disruption [13] | Complex fabrication and optimization requirements [13] |

The selection of appropriate CRISPR payload format is crucial for editing efficiency. The three primary formats include: (1) DNA plasmid encoding both Cas9 and gRNA; (2) mRNA for Cas9 translation with a separate gRNA; and (3) Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex of preassembled Cas9 protein and gRNA [17] [16]. RNP delivery offers the advantage of rapid activity with reduced off-target effects and no risk of genomic integration, making it particularly suitable for antimicrobial applications where permanent genetic modification is not required [17].

Experimental Protocols for Nanoparticle-Based CRISPR Delivery

Synthesis of CRISPR-Loaded Lipid Nanoparticles

Principle: Cationic lipids self-assemble with negatively charged CRISPR payloads through electrostatic interactions, forming nanoparticles that protect the cargo and facilitate fusion with bacterial membranes [13] [17].

Materials:

- CRISPR payload: RNP complex or plasmid DNA targeting specific antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., bla, mecA, ndm-1) [13]

- Cationic lipids: DOTAP, DOPE, or commercial transfection lipids

- Sterile PBS buffer (pH 7.4)

- Extrusion apparatus with 100-200 nm membranes

- Dialysis tubing (MWCO 100 kDa)

Procedure:

- Prepare lipid film: Dissolve cationic lipid and helper lipid in chloroform at 75:25 molar ratio. Evaporate solvent under nitrogen stream to form thin lipid film.

- Hydrate film: Hydrate lipid film with sterile PBS to a final lipid concentration of 10 mM. Vortex extensively until multilamellar vesicles form.

- Size reduction: Extrude lipid suspension through polycarbonate membranes (100 nm pore size, 11 cycles) to form unilamellar vesicles.

- CRISPR complexation: Mix CRISPR payload (RNP at 1:2 molar ratio of Cas9:gRNA) with preformed liposomes at nitrogen-to-phosphate (N/P) ratio of 10:1. Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Purification: Remove unencapsulated payload by dialysis against PBS for 2 hours or size exclusion chromatography.

- Characterization: Determine particle size (target: 100-150 nm), zeta potential (target: +20 to +30 mV), and encapsulation efficiency using fluorescence-based assays [13].

Quality Control: Verify CRISPR activity using gel retardation assay and in vitro cleavage assay with target DNA plasmid before biofilm studies.

Biofilm Penetration and Gene Editing Assessment

Principle: This protocol evaluates the ability of CRISPR-loaded nanoparticles to penetrate established biofilms and achieve targeted gene editing, measured through reduction in antibiotic resistance and biofilm viability [13].

Materials:

- Biofilm model: Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Escherichia coli biofilm grown in flow cell system or 96-well plates [13] [18]

- Culture media: Tryptic soy broth or LB medium

- CRISPR-nanoparticles: Prepared as in Protocol 3.1, targeting specific resistance genes (e.g., blaNDM-1)

- SYTO 9/propidium iodide live/dead stain

- qPCR equipment and primers for target gene quantification

- Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) system

Procedure:

- Biofilm establishment: Grow biofilms for 48-72 hours in flow cells or 96-well plates with medium replenishment every 24 hours.

- Nanoparticle treatment: Apply CRISPR-nanoparticles at sub-MIC concentrations of corresponding antibiotic. Include appropriate controls:

- Untreated biofilm

- Empty nanoparticles

- Free CRISPR system

- Incubation: Treat biofilms for 4-24 hours at 37°C with gentle agitation if using static models.

- Penetration assessment: For CLSM visualization, label nanoparticles with fluorescent dye (e.g., Cy5) prior to application. Image biofilm z-stacks at 1-2 hour intervals to track penetration kinetics.

- Efficacy assessment:

- Viability assay: Treat with SYTO 9/PI and quantify live/dead ratio using image analysis software.

- Gene editing efficiency: Extract genomic DNA from biofilm cells and perform qPCR to quantify reduction in target resistance gene abundance.

- Phenotypic validation: Measure changes in antibiotic susceptibility by exposing treated biofilms to previously ineffective antibiotics and assessing viability.

- Biomass quantification: Measure total biofilm biomass using crystal violet staining or direct dry weight measurement [13].

Expected Outcomes: Effective formulations should demonstrate >70% reduction in target gene expression, >50% reduction in viable biofilm cells, and significant resensitization to antibiotics (4-256 fold reduction in MIC values) [13] [18].

Quantitative Analysis of Delivery Efficacy

The efficacy of nanoparticle-mediated CRISPR delivery against bacterial biofilms has been quantitatively assessed across multiple studies, with results varying based on the target organism, nanoparticle system, and specific genes being edited.

Table 2: Quantitative Efficacy of CRISPR-Nanoparticle Systems Against Biofilms

| Target Bacteria | Nanoparticle Platform | Target Gene | Editing Efficiency | Biofilm Reduction | Resensitization Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | Liposomal RNP [13] | Quorum sensing genes | Not specified | >90% biomass reduction [13] | Significant improvement in antibiotic susceptibility [13] |

| E. coli | Conjugative plasmid delivery [18] | β-lactamase (bla) | 4.7%-100% [18] | Not specified | Restoration of β-lactam antibiotic efficacy [18] |

| Mixed species | Gold nanoparticle-RNP [13] | Antibiotic resistance genes | 3.5× higher vs. non-carrier [13] | Significant disruption | Synergistic effect with co-delivered antibiotics [13] |

| S. aureus | Polymeric nanoparticles [16] | mecA | Not specified | Not specified | Re-sensitization to methicillin [16] |

The variation in editing efficiency (4.7% to 100%) reflects differences in delivery efficiency, target accessibility, and bacterial uptake mechanisms [18]. Higher efficiency is typically observed when targeting essential resistance genes on plasmids rather than chromosomal genes, and when using RNP formulations with efficient nanoparticle packaging [13] [18].

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

CRISPR-Nanoparticle-Mediated Biofilm Disruption

Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Nanoparticle Biofilm Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Components | SpCas9 protein, sgRNA targeting resistance genes (e.g., blaNDM-1, mecA) [13] [18] | Precision targeting of antibiotic resistance genes | Design sgRNAs with minimal off-target potential; validate efficiency |

| Nanoparticle Materials | Cationic lipids (DOTAP, DC-Chol), PLGA, Gold nanoparticles [13] [17] [16] | CRISPR payload protection and delivery | Optimize N/P ratio for nucleic acid binding; control particle size <200nm |

| Biofilm Assay Reagents | SYTO 9/propidium iodide, crystal violet, Calgary biofilm device [13] | Biofilm growth assessment and viability testing | Standardize growth conditions; include appropriate controls |

| Analytical Tools | Dynamic light scattering, confocal microscopy, qPCR systems [13] | Nanoparticle characterization and efficacy assessment | Monitor nanoparticle stability in biological fluids |

| Bacterial Strains | Reference strains with known resistance mechanisms (e.g., PAO1, MG1655) [13] [18] | Model systems for testing | Include both planktonic and biofilm growth modes |

Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 represents a promising strategy to overcome the fundamental challenge of delivering genome-editing machinery through protective biofilm matrices and into bacterial cells. The integration of nanotechnology with gene editing creates synergistic effects, where nanoparticles not only facilitate efficient CRISPR delivery but can also provide intrinsic antibacterial activity and enable co-delivery of conventional antibiotics [13]. Current research demonstrates that this approach can achieve substantial reduction in biofilm biomass (over 90% in optimized systems) and significantly restore antibiotic efficacy against previously resistant strains [13] [18].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on creating smarter nanoparticle systems with enhanced biofilm-targeting capabilities through surface functionalization with biofilm-penetrating peptides or antibodies specific to bacterial surface antigens [16]. Additionally, the development of stimuli-responsive nanoparticles that release their CRISPR payload in response to unique biofilm microenvironment cues (such as acidic pH, specific enzymes, or low oxygen tension) could further improve specificity and reduce off-target effects [13]. As these delivery systems evolve, nanoparticle-based CRISPR therapies hold immense potential to transform the treatment of persistent biofilm-associated infections and address the growing crisis of antibiotic resistance [13] [18].

Nanoparticles as Intrinsic Anti-biofilm Agents and Advanced Delivery Vectors

Within the strategic framework of developing CRISPR-Cas9 delivery systems for biofilm eradication, nanoparticles (NPs) serve a dual therapeutic function: as intrinsic anti-biofilm agents and as advanced delivery vectors for genetic machinery. Biofilms, which are structured communities of microorganisms encapsulated in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), can exhibit up to 1000-fold greater tolerance to antibiotics compared to their planktonic counterparts [13]. This formidable resistance arises from the EPS matrix acting as a physical barrier, reduced metabolic activity of embedded cells, and enhanced horizontal gene transfer [13] [9]. Nanoparticles counter these mechanisms through their unique physicochemical properties, including their small size, high surface-area-to-volume ratio, and the ability to be engineered with specific surface functionalities [3] [19]. When leveraged to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 components, nanoparticles facilitate precision targeting of bacterial resistance genes, offering a synergistic and next-generation approach to combating biofilm-associated infections [13] [11].

Table 1: Major Classes of Nanoparticles Used as Intrinsic Anti-biofilm Agents

| Nanoparticle Class | Key Materials | Primary Anti-biofilm Mechanisms | Notable Efficacy Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal & Metal Oxide NPs | Silver (Ag), Gold (Au), Zinc Oxide | ROS generation, EPS degradation, membrane disruption [3] [20] | Green-synthesized AgNPs inhibited biofilm formation in enterococcal pathogens by >60% at 18 µg/mL [21] |

| Polymeric NPs | Chitosan, PLGA, Polyester | Electrostatic interaction with EPS, controlled release of antimicrobials [19] [22] | Chitosan NPs used to enhance drug absorption and for targeted delivery [22] |

| Lipid-Based NPs | Liposomes, Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) | Fusion with bacterial membranes, efficient encapsulation of cargo [19] | Liposomal formulations reported to reduce P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro [13] |

| Hybrid & Composite NPs | Metal-Polymer conjugates, Lipid-Polymer hybrids | Multi-mechanistic action combining physical disruption and enhanced drug delivery [3] | CRISPR-gold nanoparticle hybrids showed 3.5x increase in gene-editing efficiency [13] |

Anti-biofilm Mechanisms of Intrinsic Nanoparticle Activity

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation and Physical Disruption

Metal nanoparticles, particularly silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), exert significant intrinsic antibiofilm activity primarily through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [3] [20]. The subsequent oxidative stress damages bacterial cell membranes, proteins, and DNA, leading to cell death [20] [21]. AgNPs also physically interact with the biofilm matrix, disrupting the intermolecular forces that maintain the integrity of the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) and thereby enhancing permeability [21]. The release of silver ions (Ag+) at the nanoparticle-bacteria interface further augments this antibacterial effect [20]. Studies have demonstrated that the surface chemistry and size of NPs are critical for this activity; for instance, ginger-based AgNPs with an average size of 20.2 nm showed superior antibiofilm effects compared to larger, chemically synthesized AgNPs [21].

Quorum Sensing Inhibition and EPS Degradation

Beyond direct killing, nanoparticles can disrupt the social behavior of bacterial communities by inhibiting quorum sensing (QS) [3]. QS is a cell-density-dependent communication system that regulates biofilm formation, virulence factor production, and antibiotic resistance. By interfering with QS signaling molecules, nanoparticles can prevent biofilm maturation and render bacterial cells more vulnerable to antimicrobial agents [3] [21]. Furthermore, certain engineered nanoparticles can actively degrade essential components of the biofilm matrix, such as polysaccharides and extracellular DNA (eDNA), compromising the structural scaffold that protects the embedded cells [3].

Nanoparticles as Delivery Vectors for CRISPR-Cas9

The efficacy of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in combating biofilm-associated antibiotic resistance hinges on its precise delivery into bacterial cells [13] [11]. Nanoparticles are ideally suited to address the critical challenges of protecting the CRISPR machinery from degradation and facilitating its uptake into target bacteria. Lipid-based nanoparticles, for example, can encapsulate the Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA) complexes, shielding them from enzymatic degradation in the extracellular environment [13]. Upon reaching the biofilm, these nanocarriers fuse with bacterial membranes, enabling the intracellular release of the CRISPR components. This delivery strategy has demonstrated remarkable success, with liposomal Cas9 formulations reducing Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro [13].

Similarly, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) can be functionalized with CRISPR-Cas9 components through surface chemistry modifications, creating stable complexes that efficiently enter bacterial cells [13]. The "CRISPR-gold" platform has been shown to enhance gene-editing efficiency by 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier delivery systems [13]. This synergy between nanoparticles and CRISPR-Cas9 creates a powerful combinatorial attack: nanoparticles disrupt the biofilm's physical integrity and simultaneously deliver genetic tools to precisely target and disrupt antibiotic resistance genes, quorum-sensing pathways, or biofilm-regulating factors [13] [11] [23].

Experimental Protocols for Nanoparticle Synthesis and Evaluation

Protocol 1: Green Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs)

Principle: This protocol utilizes plant-derived phytochemicals as reducing and capping agents to synthesize biocompatible AgNPs with potent intrinsic antibiofilm activity [21].

Materials:

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃) solution (2 mM)

- Plant extract (e.g., Cinnamon or Ginger)

- Centrifugal filter devices (e.g., 10 kDa MWCO)

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer

- Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) / Zeta Potential Analyzer

- FT-IR Spectrometer

Procedure:

- Extract Preparation: Finely powder 10 g of dried plant material (e.g., ginger rhizome). Boil in 100 mL deionized water for 10 minutes and filter through a 0.2 µm membrane.

- Reduction Reaction: Add 0.0197 g of the extract to 20 mL of boiling 2 mM AgNO₃ solution under constant stirring.

- Synthesis Monitoring: Maintain the reaction at 80°C for 10-60 minutes. Observe the color change (to yellowish-brown for ginger, dark reddish-brown for cinnamon) indicating NP formation [21].

- Purification: Centrifuge the cooled NP suspension at 20,000 × g for 30 minutes. Wash the pellet with deionized water and re-suspend via sonication.

- Characterization:

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Confirm synthesis by detecting the Surface Plasmon Resonance peak between 400-450 nm [21].

- DLS & Zeta Potential: Measure hydrodynamic diameter, polydispersity index (PDI), and surface charge.

- TEM: Determine the size, morphology, and size distribution of the AgNPs.

- FT-IR: Identify the functional groups from the plant extract responsible for capping and stabilizing the NPs.

Protocol 2: Assessing Anti-biofilm Efficacy In Vitro

Principle: This protocol quantifies the ability of nanoparticles to prevent biofilm formation and disrupt pre-formed biofilms using microtiter plate assays and molecular techniques [20] [21].

Materials:

- 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plates

- Test bacterial strains (e.g., P. aeruginosa, S. aureus)

- Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) or other appropriate growth media

- Crystal Violet (CV) stain (0.1% w/v)

- Acetic acid (33% v/v)

- Microplate reader

- Real-time PCR system

Procedure: A. Biofilm Formation Inhibition Assay:

- Prepare serial dilutions of the nanoparticles in growth media to achieve sub-inhibitory concentrations (e.g., 1/2x, 1/4x, 1/8x MIC).

- Inoculate wells with 100 µL of bacterial suspension (∼10⁶ CFU/mL) and 100 µL of NP solution. Include media-only (sterility control) and bacteria-only (growth control) wells.

- Incubate statically for 24-48 hours at 37°C.

- Carefully remove planktonic cells by washing wells twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Fix the adherent biofilm with 150 µL of 99% methanol for 15 minutes. Air dry.

- Stain with 150 µL of 0.1% CV for 20 minutes. Wash thoroughly to remove unbound dye.

- Elute the bound CV with 150 µL of 33% acetic acid.

- Measure the absorbance of the eluent at 570-595 nm. Calculate % biofilm inhibition relative to the untreated control [21].

B. Disruption of Pre-formed Biofilms:

- Allow biofilms to form in microtiter plates for 24 hours as described above.

- Gently wash the mature biofilms with PBS and add fresh media containing NPs.

- Incubate for an additional 24 hours.

- Quantify the remaining biofilm using the CV staining method described above.

C. Molecular Analysis of Biofilm Genes:

- Extract total RNA from NP-treated and untreated biofilms.

- Synthesize cDNA and perform real-time PCR using primers for key biofilm-related genes (e.g., algD, pelA, pslD in P. aeruginosa; icaA in S. aureus) [20].

- Normalize gene expression levels to a housekeeping gene and calculate fold-changes using the 2^–ΔΔCt method.

Table 2: Quantitative Anti-biofilm Efficacy of Selected Nanoparticles

| Nanoparticle Type | Target Bacteria | Key Metric | Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ginger AgNPs [21] | Biofilm-forming Enterococci | Reduction in pre-formed biofilm | 60.86% reduction (to 39.14% of control) | Concentration: 18 µg/mL |

| Liposomal Cas9 [13] | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Reduction in biofilm biomass | >90% reduction | In vitro |

| CRISPR-Gold Hybrid [13] | Model Bacteria | Gene-editing efficiency | 3.5-fold increase | Compared to non-carrier delivery |

| Cinnamon AgNPs [21] | Biofilm-forming Enterococci | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | Mean MIC: 725.7 µg/mL | Broth microdilution |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nanoparticle Anti-biofilm Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Precursor salt for the synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Typically used as a 1-2 mM aqueous solution for green synthesis [21] |

| C-Phycocyanin (C-Pc) | Stabilizing and capping agent for AgNPs; improves biocompatibility | Functional groups (amino, carboxyl) provide binding sites for silver atoms [20] |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | Cationic polymer for forming polyplexes with nucleic acids (e.g., gRNA) | Aids in cellular uptake and endosomal escape; can be used to functionalize nanoparticles [14] |

| Citrate Reduction Reagents | Classical chemical method for synthesizing Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Trisodium citrate acts as both reducing and stabilizing agent [13] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Core gene-editing machinery | Requires both Cas9 protein and guide RNA (gRNA) targeting specific bacterial resistance genes [13] [11] |

| Crystal Violet (0.1%) | Dye for staining and quantifying bacterial biofilm biomass in microtiter plates [21] | Bound dye is solubilized with acetic acid for absorbance measurement |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Characterizing nanoparticle hydrodynamic size, distribution (PDI), and zeta potential | Critical for quality control of synthesized NPs [20] [21] |

Engineering the Delivery Platform: Nanoparticle Designs and CRISPR Cargo Strategies

The escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance, driven significantly by biofilm-associated infections, necessitates the development of next-generation therapeutic strategies. Biofilms, structured communities of microorganisms embedded in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), exhibit up to 1000-fold greater tolerance to antibiotics compared to their planktonic counterparts [13]. The CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing system has emerged as a revolutionary tool for precision targeting of bacterial vulnerabilities, capable of disrupting antibiotic resistance genes, quorum sensing pathways, and biofilm-regulating factors [13] [8]. However, the clinical translation of CRISPR-Cas9 is critically dependent on safe and efficient delivery systems that can navigate the complex biofilm matrix and facilitate intracellular delivery.

Nanocarriers present an innovative solution to this challenge, serving as versatile vectors for CRISPR-Cas9 components while often exhibiting intrinsic biofilm-disrupting properties [13] [24]. These nanoscale systems enhance CRISPR delivery by protecting genetic payloads from degradation, improving cellular uptake, increasing target specificity, and ensuring controlled release within the biofilm microenvironment [13] [25]. The synergy between CRISPR-Cas9 and nanotechnology has demonstrated remarkable efficacy; for instance, liposomal CRISPR-Cas9 formulations have been shown to reduce Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro, while gold nanoparticle carriers can enhance gene-editing efficiency up to 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems [13] [8]. This application note delineates the primary classes of nanocarriers—lipid-based, polymeric, metallic, and hybrid systems—detailing their compositions, mechanisms, and experimental protocols for application in CRISPR-Cas9 delivery against resilient biofilms.

Classes of Nanocarriers: Composition and Characteristics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nanocarrier Classes for CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery

| Nanocarrier Class | Key Components | CRISPR Format | Encapsulation Efficiency | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid-Based NPs | Ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, PEG-lipids [26] | mRNA/gRNA, RNP, pDNA [26] | High for nucleic acids (>85%) [26] | Low immunogenicity, clinical validation, endosomal escape [24] [26] | Cytotoxicity at high doses, complex formulation for RNP [24] [26] |

| Polymeric NPs | PLGA, chitosan, polyplexes, poly ε-caprolactone (PCL) [24] [25] | pDNA, RNP, mRNA/gRNA [25] | Moderate to High (varies with polymer) [25] | Controlled release, high stability, functionalizable surface [24] [25] | Potential cytotoxicity, batch-to-batch variability [24] |

| Metallic NPs | Gold, Silver [13] [27] | RNP, pDNA [13] [24] | Varies with surface functionalization [24] | Tunable optoelectronic properties, intrinsic antibacterial activity, surface plasmon resonance [13] [27] | Toxicity concerns, potential for oxidative stress [27] |

| Hybrid Systems | Combinations of above (e.g., lipid-polymer, metal-polymer) [13] | All formats [13] | Can be optimized for specific cargo | Synergistic properties, enhanced targeting, multi-functionality [13] | Increased complexity in manufacturing and characterization [13] |

Lipid-Based Nanoparticles (LNPs)

Lipid Nanoparticles represent the most clinically advanced non-viral delivery platform for nucleic acids, gaining prominence during the COVID-19 mRNA vaccine development [26]. Their core structure comprises four key components: ionizable lipids which are cationic at low pH and facilitate endosomal escape; phospholipids which support bilayer formation; cholesterol that enhances stability; and PEG-lipids which reduce protein adsorption and extend circulation half-life [26]. The ionizable lipids are particularly crucial for CRISPR delivery, as their positive charge enables complexation with negatively charged nucleic acids or proteins, and their phase transition in the acidic endosomal environment promotes disruption of the endosomal membrane and payload release into the cytoplasm [26].

LNPs can encapsulate various CRISPR-Cas9 formats, including plasmid DNA (pDNA) encoding Cas9 and guide RNA, Cas9 mRNA combined with guide RNA, and preassembled Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [26]. The RNP format offers the most rapid onset of gene editing as it bypasses transcription and translation steps, though its encapsulation presents technical challenges [24] [26]. Recent advances include Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) LNPs, where the addition of supplemental molecules enables tissue-specific delivery to lungs, spleen, or other organs—a critical capability for targeting biofilms in specific anatomical locations [26].

Polymeric Nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles offer exceptional versatility for CRISPR-Cas9 delivery through tunable chemical properties and controlled release kinetics. These systems can be fabricated from natural polymers like chitosan, which exhibits mucoadhesive properties beneficial for penetrating biofilm matrices, or synthetic polymers such as PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) and PCL (poly ε-caprolactone) that provide predictable degradation profiles [24] [25]. The encapsulation process typically involves self-assembly, nano-precipitation, or double-emulsion methods, with the choice depending on the CRISPR payload format and the desired release kinetics [25].

Polymeric systems excel in protecting CRISPR components from degradation by nucleases and the harsh biofilm microenvironment [25]. Functionalization with targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies) can further enhance their specificity for bacterial surfaces or biofilm components. Studies have demonstrated that antibiotic-loaded polymeric nanoparticles can overcome conventional antibiotic resistance mechanisms by enhancing intracellular delivery and bypassing efflux pumps [25], a principle that extends to CRISPR payload delivery. The modular nature of polymeric nanoparticles facilitates co-delivery of CRISPR components with antibiotics or biofilm-disrupting agents, creating synergistic anti-biofilm strategies [13] [25].

Metallic Nanoparticles

Metallic nanoparticles, particularly gold and silver, offer unique advantages for CRISPR delivery and intrinsic antibacterial activity. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) can be precisely engineered in size and shape, and their surface functionalization with thiol chemistry allows stable conjugation with CRISPR components [13] [24]. Studies have demonstrated that CRISPR-gold nanoparticle hybrids can enhance editing efficiency up to 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems while promoting synergistic action with antibiotics [13]. The high surface-area-to-volume ratio enables high payload capacity, and their tunable optoelectronic properties allow for potential light-controlled activation or thermal disruption of biofilms.

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) exhibit potent intrinsic antimicrobial activity through multiple mechanisms, including membrane disruption, reactive oxygen species generation, and interference with microbial DNA and proteins [27]. When combined with CRISPR systems, this intrinsic activity can provide a dual-action therapeutic approach. However, potential cytotoxicity to mammalian cells remains a concern for metallic nanoparticles, necessitating careful dosage control and surface modification to improve biocompatibility [27].

Hybrid Nanocarriers

Hybrid nanocarriers integrate multiple material classes to overcome individual limitations and create synergistic functionalities. Examples include lipid-polymer hybrids that combine the biocompatibility of lipids with the structural stability of polymers, metal-organic frameworks with high porosity for payload loading, and cell membrane-coated nanoparticles that leverage natural targeting mechanisms [13]. These systems can be engineered to sequentially release multiple payloads—for instance, initial release of biofilm-disrupting agents to penetrate the EPS matrix, followed by targeted delivery of CRISPR components to the exposed bacterial cells [13].

Hybrid platforms enable sophisticated targeting strategies through surface functionalization with antibodies, lectins, or aptamers that recognize specific bacterial surface markers or biofilm components [13]. They can also incorporate environment-responsive elements (e.g., pH-sensitive linkers, enzyme-cleavable coatings) that trigger payload release specifically in the biofilm microenvironment, characterized by acidic pH and elevated enzyme concentrations [13] [25]. The co-delivery capacity of hybrid systems is particularly valuable for biofilm eradication, allowing simultaneous targeting of multiple resistance mechanisms or combining genetic and conventional antimicrobial approaches [13].

Experimental Protocols for Nanocarrier Evaluation

Protocol 1: Formulation and Characterization of CRISPR-Loaded Lipid Nanoparticles

Materials:

- Ionizable lipid (e.g., DLin-MC3-DMA)

- Helper lipids: DSPC, Cholesterol

- PEG-lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG2000)

- CRISPR payload (mRNA, pDNA, or RNP)

- Acidic buffer (e.g., citrate buffer, pH 4.0)

- Ethanol and PBS solutions

- Microfluidic device or tubing setup

Methodology:

- Lipid Solution Preparation: Dissolve ionizable lipid, DSPC, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid in ethanol at molar ratio 50:10:38.5:1.5 to achieve total lipid concentration of 10 mM [26].

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Dilute CRISPR payload in citrate buffer (pH 4.0) at concentration of 0.2 mg/mL for mRNA or 0.5 mg/mL for RNP complexes [26].