Navigating the Sensitivity Limits: A Comprehensive Comparison of Quantification Methods for Low-Biomass Microbiome Research

Accurate quantification in low-biomass microbiome studies is paramount for fields ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental science, yet it presents unique methodological challenges.

Navigating the Sensitivity Limits: A Comprehensive Comparison of Quantification Methods for Low-Biomass Microbiome Research

Abstract

Accurate quantification in low-biomass microbiome studies is paramount for fields ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental science, yet it presents unique methodological challenges. This article provides a systematic comparison of quantification method sensitivity, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles defining low-biomass environments and their inherent challenges, detail the application of established and emerging methodological protocols, offer robust strategies for troubleshooting contamination and optimizing recovery, and present a critical validation framework for comparing method performance. By synthesizing current best practices and evidence-based comparisons, this guide aims to empower scientists in selecting and implementing the most sensitive and reliable quantification approaches for their specific low-biomass applications.

Defining the Low-Biomass Challenge: Why Sensitivity Matters in Microbial Detection

What Constitutes a Low-Biomass Sample? A Spectrum from Host-Associated Tissues to Sterile Environments

Low-biomass samples are characterized by exceptionally low concentrations of microbial cells and their genetic material, posing unique challenges for accurate characterization and quantification. These samples contain minimal microbial DNA that approaches the limits of detection for standard sequencing approaches, making them particularly vulnerable to contamination and technical artifacts [1] [2]. Unlike high-biomass environments like gut or soil, where microbial DNA is abundant, low-biomass samples can be easily overwhelmed by contaminating DNA from reagents, sampling equipment, or laboratory environments, potentially leading to false conclusions [1] [3]. The defining feature of low-biomass environments is the proportional nature of sequence-based data: even minute amounts of contaminating DNA can constitute a significant portion, or even the majority, of the observed microbial signal [2]. This review explores the spectrum of low-biomass environments, the methodological challenges they present, and the advanced quantification strategies required for reliable research in this demanding field.

A Spectrum of Low-Biomass Environments

Low-biomass conditions exist across a diverse range of host-associated tissues and environmental niches. The classification is not binary but rather exists on a continuum, with certain analytical challenges becoming more pronounced as microbial biomass decreases [3].

Host-Associated Low-Biomass Environments

Historically, many internal human tissues were considered sterile, but advanced sequencing technologies have enabled the investigation of potentially resident microbial communities in these challenging environments.

- Respiratory Tract: Including lung tissues, which harbor lower microbial biomass compared to the upper airways [2] [3].

- Reproductive and Fetal Tissues: The placenta, amniotic fluid, and fetal tissues have been subjects of intense debate regarding the existence of a resident microbiome [2] [4].

- Blood and Circulatory System: Blood is now recognized as a low-biomass environment that may contain microbial DNA, even in healthy individuals, challenging the old dogma of sterility [2] [5].

- Internal Organs and Tissues: Healthy brain tissues and certain tumors represent internal sites with very low microbial biomass [2] [3].

- Urinary Tract: Urine, once considered sterile, is now known to host a low-biomass microbiome that can be associated with urological diseases [6].

- Breast Milk: Contains low levels of microbial biomass that are of significant interest for infant health and development [2].

Environmental Low-Biomass Niches

Beyond host-associated environments, numerous natural and built environments also present low-biomass conditions.

- Atmosphere and Air: The air contains low levels of microbial biomass that can be sampled and analyzed [2].

- Treated Drinking Water: Water that has undergone purification processes has significantly reduced microbial load [2].

- Hyper-Arid Soils and Dry Permafrost: Extreme dryness limits microbial life, resulting in low biomass [2].

- Deep Subsurface and Rocks: Environments deep within the earth's crust host limited microbial life [2].

- Hypersaline Brines and Ice Cores: Extreme conditions of salt or temperature restrict microbial growth [2].

- Cleaned Metal Surfaces and Cleanrooms: Built environments designed to minimize microbial presence [2].

Table 1: Categorization of Low-Biomass Environments with Example Sample Types

| Category | Example Environments | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Human Tissues | Lung, Placenta, Blood, Brain, Urine, Breast Milk [2] [3] [6] | High host DNA to microbial DNA ratio; Susceptible to contamination during collection; Often lack resident microbes [1] [5] [4]. |

| Animal & Plant Tissues | Certain animal guts (e.g., caterpillars), Plant seeds [2] | Similar challenges to human tissues; Potential for vertical transmission studies. |

| Extreme Natural Environments | Hyper-arid soils, Deep subsurface, Ice cores, Atmosphere [2] | Physicochemical extremes limit life; Difficult and controlled access required for sampling. |

| Engineered & Built Environments | Treated drinking water, Cleanrooms, Metal surfaces [2] | Biomass reduced by design (purification, sterilization); Monitoring for contamination is key. |

Critical Methodological Challenges and Contamination

The analysis of low-biomass samples is fraught with technical pitfalls that can compromise biological conclusions if not rigorously addressed.

The Pervasive Challenge of Contamination

In low-biomass studies, the signal from the actual sample can be dwarfed by the "noise" introduced from external sources. Major contamination sources include human operators, sampling equipment, laboratory reagents, and kits [2] [3]. Even molecular biology reagents, which are considered pure, often contain trace amounts of microbial DNA that become detectable when the target DNA is minimal [1]. This contamination is not random; it often presents as consistent microbial signatures across samples, which can be mistaken for a true biological signal [3]. The highly publicized debate over the existence of a placental microbiome exemplifies this issue, where subsequent rigorously controlled studies suggested that initial positive findings were likely driven by contamination [3] [4].

Additional Analytical Pitfalls

Beyond general contamination, several other technical challenges require careful consideration:

- Host DNA Misclassification: In metagenomic analyses of human tissues, the vast majority of sequenced DNA (e.g., over 99.99% in some tumor microbiome studies) is of human origin [3]. If not properly accounted for, this host DNA can be misclassified as microbial during bioinformatic analysis, generating noise or even artifactual signals [3].

- Well-to-Well Leakage (Cross-Contamination): Also termed the "splashome," this phenomenon occurs when DNA from one sample leaks into an adjacent well on a processing plate (e.g., a 96-well plate) during laboratory workflows [2] [3]. This can compromise the inferred composition of every sample in a batch and violates the assumptions of many computational decontamination methods [3].

- Batch Effects and Processing Bias: Differences in protocols, personnel, reagent batches, or sequencing runs can introduce technical variation that confounds biological signals [3]. This is exacerbated in low-biomass research where the signal is weak and can be disproportionately affected by technical variables.

Diagram: Contamination in Low-Biomass Research: This diagram illustrates the primary sources of contamination, their potential impacts on data integrity, and key mitigation strategies required for reliable results.

Best Practices for Reliable Low-Biomass Research

Foundational Experimental Design Principles

Optimal study design is paramount for generating credible data from low-biomass samples. The following principles should be implemented:

- Avoid Batch Confounding: A critical step is to ensure that the biological groups of interest (e.g., cases vs. controls) are not processed in separate batches [3]. If all samples from one group are processed together and the other group separately, any batch-specific contamination or technical bias will be perfectly confounded with the biology, generating artifactual signals [3]. Active randomization or balancing tools should be used.

- Implement Comprehensive Process Controls: It is standard practice to include a variety of negative control samples that undergo the entire experimental process alongside the biological samples [2] [3]. These are essential for identifying the contamination background. Recommended controls include:

- Blank Extraction Controls: Tubes containing only the lysis buffer or other reagents used in DNA extraction [3].

- No-Template PCR Controls: Water or buffer used in the amplification step to detect kit reagent contamination [3].

- Sampling Controls: For tissue studies, this may include swabs of the skin near the surgical site or swabs exposed to the air in the operating theatre [2].

- Minimize Contamination During Sampling: Pre-treatment of sampling equipment with DNA-degrading solutions (e.g., bleach, UV-C light) and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) can significantly reduce human-derived contamination [2]. Using single-use, DNA-free collection vessels is ideal [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Biomass Microbiome Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Primary Function | Application Notes & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA/PMAxx) | Viability dye that penetrates cells with compromised membranes, binding their DNA and preventing amplification [7]. | Used to distinguish between intact (potentially viable) and dead cells; requires optimization of concentration and light exposure for different sample matrices [7]. |

| DNA-free Nucleic Acid Removal Agents | Sodium hypochlorite (bleach), hydrogen peroxide, or commercial DNA removal solutions degrade contaminating DNA on surfaces and equipment [2]. | Critical for decontaminating work surfaces and reusable labware; note that sterility (e.g., via autoclaving) does not equate to being DNA-free [2]. |

| MolYsis and Similar Host-DNA Depletion Kits | Selective lysis of human/host cells and degradation of the released host DNA, enriching for microbial DNA [7]. | Improves microbial sequencing depth in samples rich in host cells (e.g., tissue, blood); crucial for detecting low levels of microbial signal [5] [7]. |

| Maxwell RSC and other Automated Extraction Kits | Standardized, automated nucleic acid extraction to minimize cross-contamination and user-induced variability [8]. | Kit-based methods (e.g., QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit) have been shown to provide good reproducibility and sensitivity for low-biomass samples [9]. |

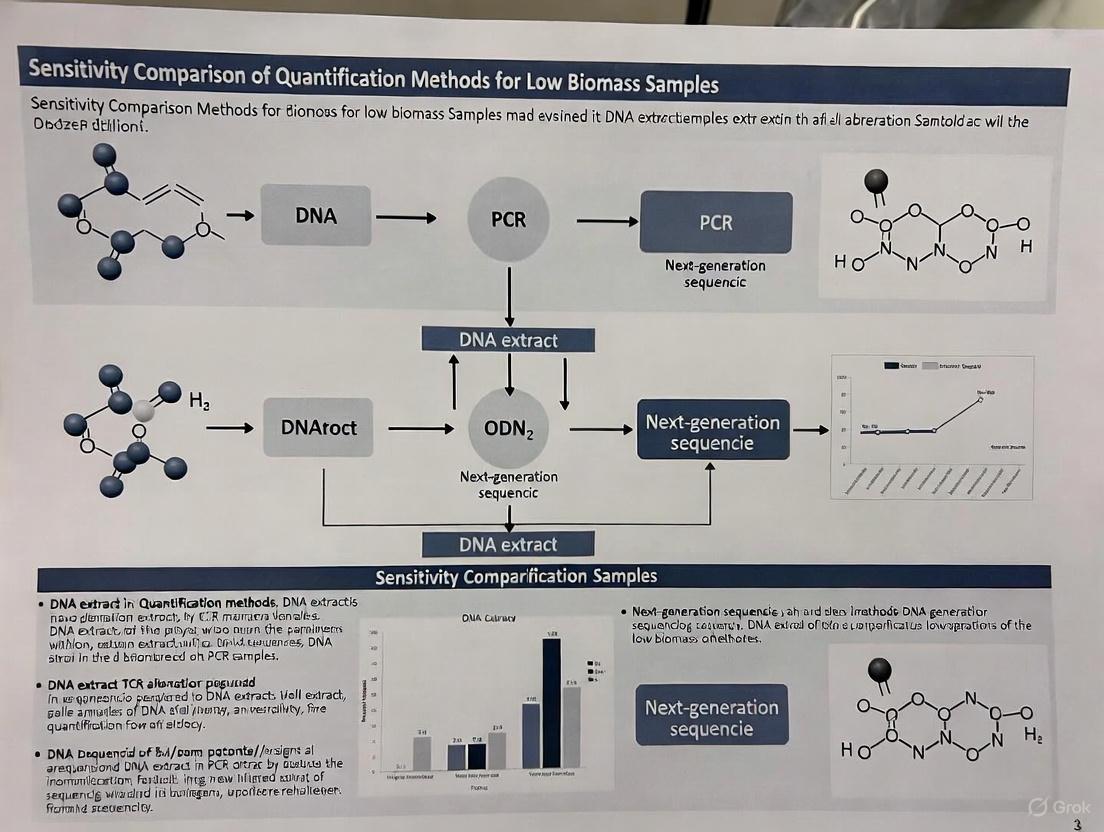

Sensitivity Comparison of Quantification Methodologies

Accurately quantifying microbes in low-biomass environments requires methods that are both sensitive and robust to contamination. The following table compares the primary approaches used in the field.

Table 3: Sensitivity Comparison of Quantification Methods for Low-Biomass Research

| Methodology | Key Principle | Reported Limit of Detection (LOD) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Amplification & sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene to profile bacterial composition [1] [5]. | Not explicitly quantified, but highly susceptible to contamination without controls [1] [3]. | High sensitivity for community profiling; identifies unculturable taxa; optimized for low biomass (e.g., Vaiomer's V3-V4 assay) [1] [5]. | Semi-quantitative (compositional); high contamination risk; limited functional & strain-level data [1] [3]. |

| Shotgun Metagenomics | Random sequencing of all DNA in a sample to reconstruct genomes and functions [1] [3]. | Susceptible to host DNA misclassification; microbial reads can be ~0.01% in tumors [3]. | Strain-level resolution & functional potential assessment (e.g., AMR genes) [1] [9]. | Overwhelmed by host DNA in tissues; requires high sequencing depth; expensive for low-yield samples [3] [5]. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Amplification of a target DNA sequence with fluorescent probes for quantification against a standard curve [9] [8]. | ~10³ to 10⁴ cells/g feces for strain-specific assays; sensitive for low biomass [9]. | Highly sensitive & quantitative; wide dynamic range; cost-effective & fast [9]. | Requires prior knowledge of target; affected by PCR inhibitors; relies on external standards [9] [8]. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Partitions sample into thousands of nano-droplets for absolute quantification without a standard curve [9] [8]. | Similar or slightly better than qPCR; superior for low-abundance targets in complex samples [9] [8]. | Absolute quantification; more resistant to PCR inhibitors; high precision for low-copy targets [9] [8]. | Narrower dynamic range than qPCR; higher cost; more complex workflow [9]. |

| Flow Cytometry (FCM) | Direct counting of individual cells stained with DNA-specific dyes [10]. | High reproducibility (RSD <3%); results in 15 min for water samples [10]. | Rapid, direct cell count; distinguishes live/dead cells; automation potential [10]. | Not for aggregated cells or complex tissues; requires cell suspension; bias in sample prep [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Quantification Methods

Protocol 1: Strain-Specific qPCR for Absolute Quantification (Adapted from [9])

This protocol is designed for the highly accurate and sensitive absolute quantification of specific bacterial strains in complex samples like feces or tissue.

- Primer Design: Identify strain-specific marker genes from whole-genome sequences. Design primers with high specificity and validate in silico against databases.

- DNA Extraction: Use a kit-based DNA isolation method (e.g., modified QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit protocol) for optimal reproducibility and sensitivity. Include a pre-lysis wash step if necessary to remove PCR inhibitors.

- Standard Curve Calibration: Prepare a standard curve using a known quantity of the target strain. Serial dilutions should cover the expected dynamic range (e.g., from 10² to 10⁸ gene copies). The standard can be genomic DNA from a pure culture or a synthesized gene fragment.

- qPCR Setup and Run: Perform reactions in triplicate using a master mix containing a DNA intercalating dye (e.g., SYBR Green) or a specific probe (e.g., TaqMan). Use a thermal cycling protocol optimized for the primer pair.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the absolute quantity of the target in the unknown samples by interpolating from the standard curve. Correct for sample weight/dilution factor to report cells per gram or milliliter.

Protocol 2: Viability Assessment with PMA-treated Metagenomics (Adapted from [7])

This method helps distinguish DNA from cells with intact membranes (potentially viable) from free DNA or DNA in dead cells.

- Sample Preparation: Resuspend the sample pellet (e.g., from milk, water, or washed tissue) in 1 mL of sterile PBS.

- PMA Treatment: Add PMA or PMAxx dye to the sample to a final concentration of 20 μM. Incubate in the dark at room temperature for 5-10 minutes.

- Photoactivation: Place the sample tube on ice and expose to a bright LED light source (e.g., PMA-Lite device) for 15-30 minutes to cross-link the dye to DNA from membrane-compromised cells.

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Proceed with standard DNA extraction (e.g., using MolYsis complete5 kit for samples with high host background). Perform shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the microbial community profile of the PMA-treated sample to an untreated aliquot from the same sample. A significant reduction in certain taxa in the PMA-treated sample indicates they were predominantly non-viable.

Low-biomass samples represent a frontier in microbiome research, spanning from human tissues like placenta and blood to extreme environments like the deep subsurface and cleanrooms. The defining challenge in studying these environments is the profound susceptibility to contamination, which can easily lead to false discoveries. Success in this field hinges on a rigorous, contamination-aware approach that integrates meticulous experimental design—featuring comprehensive controls and deconfounded processing batches—with a thoughtful selection of quantification technologies. While 16S rRNA sequencing and shotgun metagenomics are powerful for discovery, they must be complemented by absolute quantification methods like qPCR and ddPCR, and potentially viability-staining techniques, to provide robust, reproducible, and biologically meaningful data. As methodologies continue to evolve, the principles of caution, validation, and transparency remain the bedrock of reliable low-biomass microbiome science.

Low-biomass microbiome research represents one of the most technically challenging frontiers in microbial ecology and clinical diagnostics. Samples with minimal microbial content—including human tissues like tumors and placenta, environmental samples like cleanrooms and drinking water, and complex matrices like wastewater—present unique obstacles that can compromise data integrity and lead to spurious biological conclusions. The dominance of host DNA, the presence of PCR inhibitors, and the pervasive risk of contamination collectively form a triad of technical challenges that require sophisticated methodological approaches to overcome. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current methods and technologies designed to address these challenges, offering researchers a framework for selecting appropriate protocols based on experimental needs and sample characteristics. By critically examining the performance of various quantification and profiling techniques, we aim to equip scientists with the knowledge needed to navigate the complexities of low-biomass research and generate reliable, reproducible results.

The Contamination Challenge in Low-Biomass Studies

Contamination represents perhaps the most insidious challenge in low-biomass microbiome research. Unlike high-biomass environments where the target microbial signal dominates, low-biomass samples can be overwhelmed by contaminating DNA from reagents, sampling equipment, laboratory environments, and personnel. This problem is particularly acute when working near the limits of detection, where contaminating DNA can constitute a substantial proportion of the final sequencing data and potentially lead to false discoveries.

The research community has recognized that practices suitable for higher-biomass samples may produce misleading results when applied to low microbial biomass samples [2]. Contaminants can be introduced at virtually every stage of the experimental workflow—during sample collection, storage, DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing [2] [3]. A particularly problematic form of contamination is "well-to-well leakage" or "cross-contamination," where DNA from one sample contaminates adjacent samples during plate-based processing [2] [3]. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as the "splashome," can compromise the inferred composition of every sample in a sequencing run and violates the assumptions of most computational decontamination methods [3].

The historical controversy surrounding the purported "placental microbiome" exemplifies the critical importance of proper controls in low-biomass research. Initial claims of a resident placental microbiome were later revealed to be driven largely by contamination, highlighting how methodological artifacts can be misinterpreted as biological signals [3]. Similar debates have emerged regarding microbial communities in human blood, brains, cancerous tumors, and various extreme environments [2].

Table: Types of Contamination in Low-Biomass Studies and Their Sources

| Contamination Type | Primary Sources | Impact on Data |

|---|---|---|

| Reagent contamination | DNA extraction kits, PCR reagents, water | Introduces consistent background "kitome" across samples |

| Human operator contamination | Skin, hair, breath, clothing | Introduces human-associated microbes |

| Cross-contamination (well-to-well leakage) | Adjacent samples in plates | Creates artificial similarity between samples |

| Environmental contamination | Airborne particles, laboratory surfaces | Introduces sporadic, variable contaminants |

| Equipment contamination | Sampling devices, processing tools | Transfers contaminants between samples |

Methodological Comparisons: Quantification and Detection Approaches

The selection of appropriate quantification and detection methods is critical for successful low-biomass research. Different methodologies offer varying levels of sensitivity, precision, and resistance to inhibitors, making them differentially suitable for specific sample types and research questions.

Concentration and Extraction Methods

The initial steps of sample concentration and DNA extraction profoundly influence downstream analyses. In wastewater surveillance, aluminum-based precipitation (AP) has demonstrated superior performance for concentrating antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) compared to filtration-centrifugation (FC) approaches, particularly in treated wastewater samples [8]. The AP method provided higher ARG concentrations than FC, highlighting how selection of concentration methodology can significantly impact detection sensitivity [8].

For sample collection from surfaces, innovative devices like the Squeegee-Aspirator for Large Sampling Area (SALSA) offer advantages over traditional swabbing. The SALSA device achieves approximately 60% recovery efficiency, substantially higher than the typical 10% recovery of swabs, by combining squeegee action and aspiration to bypass cell and DNA adsorption to swab fibers [11]. This improved recovery is particularly valuable for ultra-low-biomass environments like cleanrooms and hospital operating rooms.

DNA extraction methodologies also significantly impact results. Studies comparing silica column-based extraction, bead absorption, and chemical precipitation have found that silica columns provide better extraction yields for low-biomass samples [12]. Additionally, increasing mechanical lysing time and repetition improves representation of bacterial composition, likely by ensuring more efficient lysis of difficult-to-break microbial cells [12].

Quantification and Profiling Technologies

The choice between quantification technologies depends on required sensitivity, resistance to inhibitors, and need for absolute versus relative quantification. Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) has emerged as a powerful alternative to quantitative PCR (qPCR) for detecting low-abundance targets in complex matrices. In wastewater analysis, ddPCR demonstrates greater sensitivity than qPCR, while in biosolids, both methods perform similarly, though ddPCR exhibits weaker detection [8]. The partitioning of samples in ddPCR reduces the impact of inhibitors that often plague complex environmental samples [8].

For comprehensive taxonomic profiling, several sequencing approaches are available. Traditional 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing remains widely used but can be limited by primer bias and taxonomic resolution. Whole metagenome shotgun (WMS) sequencing offers superior resolution but typically requires substantial DNA input (≥50 ng preferred) and is inefficient for samples with high host DNA contamination or severe degradation [13].

The innovative 2bRAD-M method provides an alternative that addresses some limitations of both approaches. This highly reduced strategy sequences only ~1% of the metagenome using Type IIB restriction enzymes to produce iso-length fragments, enabling species-level profiling of bacterial, archaeal, and fungal communities simultaneously [13]. 2bRAD-M can accurately profile samples with merely 1 pg of total DNA, high host DNA contamination (up to 99%), or severely fragmented DNA, making it particularly suitable for challenging low-biomass and degraded samples [13].

Table: Comparison of Quantification and Profiling Methods for Low-Biomass Samples

| Method | Sensitivity Limit | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR | Varies by target | Wide availability, established protocols | Susceptible to inhibitors, requires standard curves | Target-specific quantification in moderate biomass |

| ddPCR | Enhanced over qPCR in complex matrices | Absolute quantification, reduced inhibitor effects | Higher cost, weaker detection in some matrices | Low-abundance targets in inhibitory matrices |

| 16S rRNA Amplicon | ~10^6 bacteria/sample [12] | Cost-effective, PCR amplification enhances sensitivity | Primer bias, limited taxonomic resolution | Community profiling when biomass sufficient |

| Whole Metagenome | ~10^7 microbes/sample [12] | High resolution, functional potential | High DNA input, inefficient with host contamination | Higher biomass samples without host dominance |

| 2bRAD-M | 1 pg total DNA [13] | Species-resolution, works with high host DNA | Limited functional information | All domains, low-biomass, high-host contamination |

Experimental Design and Best Practices

Robust experimental design is paramount for generating reliable data from low-biomass studies. Several key considerations can significantly reduce the impact of contamination and other technical artifacts.

Contamination Controls

The inclusion of comprehensive controls is non-negotiable in low-biomass research. Best practices recommend collecting process controls that represent all potential contamination sources throughout the experimental workflow [2] [3]. These should include:

- Empty collection vessels to control for contaminants in sampling equipment

- Swabs exposed to air in the sampling environment to assess airborne contamination

- Sample preservation solutions to identify contaminants in storage reagents

- Extraction blanks to monitor contaminants introduced during DNA extraction

- Library preparation controls to detect contamination during sequencing library preparation [3]

Multiple controls should be included for each contamination source to accurately quantify the nature and extent of contamination, and these controls must be processed alongside actual samples through all downstream steps [2]. Researchers should note that different manufacturing batches of consumables like swabs may have different contamination profiles, necessitating batch-specific controls [3].

Biomass Considerations

Sample biomass represents a fundamental limitation in low-biomass studies. Research has demonstrated that bacterial densities below 10^6 cells result in loss of sample identity based on cluster analysis, regardless of the protocol used [12]. This threshold represents a critical lower limit for robust and reproducible microbiota analysis using standard 16S rRNA gene sequencing approaches.

The ratio of microbial to host DNA also significantly impacts sequencing efficiency. In fish gill microbiome studies, host DNA can represent three-quarters of total sequencing reads, dramatically reducing the efficiency of microbial community characterization [14]. Similar challenges occur in human tissue studies, where host DNA can constitute over 99.9% of sequenced material [3].

Normalization Strategies

Normalization approaches can significantly improve data quality from low-biomass samples. Quantitative PCR assays for both host material and 16S rRNA genes enable screening of samples prior to costly sequencing and facilitate the production of "equicopy libraries" based on 16S rRNA gene copies [14]. This approach has been shown to significantly increase captured bacterial diversity and provide greater information on the true structure of microbial communities [14].

PCR protocol selection also influences results. Semi-nested PCR protocols have demonstrated better representation of microbiota composition compared to classical PCR approaches, particularly for low-biomass samples [12]. This improved performance comes from enhanced amplification efficiency while maintaining representation of community structure.

Optimized Workflows for Low-Biomass Research

Based on current evidence, successful low-biomass microbiome research requires integrated workflows that address multiple challenges simultaneously. The following diagram illustrates a recommended approach that incorporates best practices for contamination control, sample processing, and data analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful low-biomass research requires careful selection of reagents and materials at each experimental stage. The following table outlines key solutions and their applications:

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Low-Biomass Studies

| Category | Specific Solution | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling | SALSA device [11] | High-efficiency surface sampling (60% recovery) | Bypasses swab adsorption issues |

| Decontamination | Sodium hypochlorite (bleach) [2] | DNA removal from surfaces | More effective than ethanol alone |

| DNA Extraction | Silica column-based kits [12] | High-yield DNA extraction | Superior to bead absorption for low biomass |

| Inhibition Resistance | ddPCR technology [8] | Absolute quantification despite inhibitors | Partitioning reduces inhibitor effects |

| Amplification | Semi-nested PCR [12] | Enhanced sensitivity for low template | Better composition representation |

| Host Depletion | 2bRAD-M [13] | Species-resolution despite host DNA | Works with 99% host contamination |

| Quantification | Dual qPCR assays [14] | Simultaneous host and microbial DNA quant | Enables equicopy normalization |

Low-biomass microbiome research presents formidable challenges that demand rigorous methodological approaches. Host DNA dominance, inhibitors, and contamination collectively represent critical obstacles that can compromise data integrity and lead to erroneous biological conclusions. The comparison of current methodologies reveals that method selection must be tailored to specific sample characteristics and research questions. While no single technology addresses all challenges comprehensively, integrated approaches that combine optimized sampling, appropriate quantification methods, stringent contamination controls, and sophisticated bioinformatic decontamination offer the most promising path forward. As methodological refinements continue to emerge, including techniques like 2bRAD-M and ddPCR, the research community's capacity to reliably investigate low-biomass environments will continue to expand. By adhering to best practices in experimental design and maintaining skepticism toward extraordinary claims, researchers can navigate the technical complexities of low-biomass studies while generating robust, reproducible findings that advance our understanding of microbial life at the limits of detection.

In fields such as microbiology, genomics, and environmental science, researchers increasingly study systems with minimal biological material, known as low-biomass environments. These can range from human tissues and potable water to the upper respiratory tract and certain aquatic interfaces. The fundamental challenge in these studies is reliably distinguishing true biological signals from technical noise introduced during sample collection, processing, and analysis. Technical noise can originate from various sources, including contamination, stochastic molecular losses during amplification, and instrument limitations. This guide provides a comparative analysis of methods and technologies designed to enhance signal detection while mitigating noise in low-biomass research, with a specific focus on sensitivity comparisons.

Experimental Protocols for Low-Biomass Research

Optimized Sample Collection and Processing

Robust sampling methods are critical for maximizing microbial recovery while minimizing contamination and host DNA contamination.

- Protocol for Low-Biomass Microbiome Studies: Contamination must be minimized from sample collection through data analysis. Key steps include:

- Decontamination: Equipment, tools, and vessels should be decontaminated with 80% ethanol to kill organisms, followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., sodium hypochlorite, UV-C light) to remove trace DNA [2].

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Operators should use appropriate PPE, including gloves, goggles, coveralls, and masks, to limit contamination from human sources such as aerosol droplets and skin cells [2].

- Controls: Essential to include field blanks, swabs of sampling surfaces, and aliquots of preservation solutions to identify contaminants introduced during collection and processing [2].

- Gill Microbiome Sampling Protocol: For inhibitor-rich, low-biomass tissues like fish gills, a optimized method involves:

- Filter Swabbing: Using a sterile filter paper pressed against the gill filament to collect mucosal microbes, then resuspending the biomass. This method demonstrated significantly higher 16S rRNA gene recovery and lower host DNA contamination compared to whole-tissue sampling or surfactant washes [14].

- Quantification and Normalization: Employing quantitative PCR (qPCR) to quantify 16S rRNA gene copies prior to library construction. Creating equicopy libraries based on this quantification significantly increases captured diversity and improves community structure analysis [14].

Sample Concentration for Water Analysis

Concentrating samples is often necessary to detect signals in very dilute environments, such as potable water on the International Space Station (ISS).

- ISS Smart Sample Concentrator (iSSC) Protocol: This method processes large water volumes (up to 1 L) efficiently.

- Concentration: The water sample is drawn through a hollow-fiber membrane concentration cell, which captures microbes and particles larger than 0.2 µm.

- Elution: Captured microbes are eluted using a wet foam elution process with a carbonated buffered fluid containing a foaming agent (Tween 20). The process yields a highly concentrated liquid sample (≈450 µL), achieving concentration factors of approximately 2200x [15].

- Analysis: The concentrated sample can be analyzed using both culture-based (CFU) and molecular methods (qPCR) [15].

Computational Noise Filtering

Computational tools are essential for distinguishing noise from signal in sequencing data, especially near the detection limit.

- noisyR Protocol: This comprehensive noise-filtering pipeline assesses technical noise without relying on strong biological assumptions.

- Input: Works with either raw count matrices or alignment data (BAM files).

- Methodology: Quantifies noise based on the correlation of expression profiles across subsets of genes in different samples and across abundance levels. It outputs sample-specific signal/noise thresholds and filtered expression matrices [16].

- Application: Effective for various sequencing assays, including bulk and single-cell RNA-seq, and non-coding RNA studies [16].

- Generative Model for scRNA-seq Noise: A statistical model decomposes total gene expression variance in single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data into biological and technical components.

- Spike-ins: Uses externally spiked-in RNA molecules to model the expected technical noise.

- Modeling: Captures major noise sources, including stochastic transcript dropout during sample preparation and shot noise (counting noise). It allows cell-to-cell variation in capture efficiency [17].

- Output: Estimates the biological variance by subtracting the technical variance from the total observed variance [17].

Sensitivity Comparison of Methods and Technologies

The sensitivity of a method is its ability to detect true biological signals at low levels. The following tables compare the performance of various sampling, concentration, and computational methods based on experimental data from the cited literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Sampling Methods for Low-Biomass Microbiome Analysis

| Method | Target | Key Metric | Performance | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Swab [14] | Fish Gill Microbiome | 16S rRNA Gene Recovery | Significantly higher copies vs. tissue (P=4.793e−05); significantly less host DNA (P=2.78e−07) | Maximizes bacterial signal, minimizes host inhibitor | Requires optimization for specific tissues |

| Surfactant Wash [14] | Fish Gill Microbiome | Host DNA Contamination | Higher host DNA at 1% Tween 20 vs. 0.1% (P=1.41e−4) | Can solubilize mucosal layers | Dose-dependent host cell lysis and DNA release |

| Whole Tissue [14] | Fish Gill Microbiome | Bacterial Diversity (Chao1) | Significantly lower diversity compared to swab | Standard, direct | High host DNA, low bacterial signal and diversity |

Table 2: Performance of Sample Concentration Technologies

| Technology | Sample Type | Concentration Factor | Percent Recovery | Reference/Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iSSC [15] | Potable Water (1L) | ~2,200x | 40-80% (S. paucimobilis, CFU); ~45-50% (C. basilensis, R. pickettii, CFU) | NASA limit: 5x10⁴ CFU/L |

| Traditional Filtration [15] | Potable Water | Not specified | Outperformed by iSSC in Phase II comparison [15] | Lacks automation, slower for large volumes |

Table 3: Computational Noise Filtering Tools

| Tool/Method | Data Type | Methodology | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| noisyR [16] | Bulk & single-cell RNA-seq | Correlation-based noise assessment & filtering | Improves consistency in differential expression calls and gene regulatory network inference |

| Generative Model [17] | scRNA-seq with spike-ins | Decomposes variance using external RNA spike-ins | Accurately attributes only 17.8% of stochastic allelic expression to biological noise; rest is technical |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful low-biomass research relies on specialized reagents and materials to preserve sensitivity and minimize contamination.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Biomass Studies

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Decontamination Solutions | Degrades contaminating DNA on surfaces and equipment. Critical for reducing background noise. | Sodium hypochlorite (bleach), UV-C light, hydrogen peroxide, commercial DNA removal solutions [2] |

| External RNA Control Consortium (ERCC) Spike-ins | Known quantities of exogenous RNA transcripts used to model and quantify technical noise in sequencing data. | Calibrating technical noise in single-cell RNA-sequencing experiments [17] |

| Hollow-Fiber Membrane Filters | Capture microbes from large liquid volumes during concentration; part of the Concentrating Pipette Tip (CPT) design. | Used in the iSSC and CP-150 concentrators for processing water samples up to 1L [15] |

| Wet Foam Elution Fluid | A buffered fluid containing a foaming agent (Tween 20) stored under CO₂ pressure. Enables efficient elution of captured microbes into a small volume. | Critical component of the iSSC and InnovaPrep CP systems for sample concentration [15] |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | Forms a physical barrier to prevent contamination of samples from researchers (e.g., skin cells, aerosols). | Cleanroom suits, gloves, face masks, and goggles during sample collection [2] |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual workflow and decision points for managing technical noise in low-biomass research, from experimental design to data interpretation.

Workflow for Noise Management in Low-Biomass Research. This diagram outlines the critical stages for distinguishing biological signal from technical noise, highlighting the integration of experimental controls and computational analysis throughout the process.

The accurate interpretation of low-biomass research data hinges on a multi-faceted strategy that integrates rigorous experimental design, optimized sample handling, and sophisticated computational noise filtering. No single method is sufficient on its own. As evidenced by the comparative data, choices in sampling technique, concentration technology, and data analysis pipeline profoundly impact the sensitivity and fidelity of the results. By adopting a holistic approach that combines stringent contamination controls, validated concentration protocols, and robust computational tools, researchers can confidently distinguish genuine biological signals from technical artifacts, thereby advancing our understanding of life at its physical limits.

The study of microbiomes in environments where microorganisms are scarce, known as low-biomass microbiomes, represents one of the most methodologically challenging and controversial areas in modern microbial ecology. Research on the placental and tumor microbiomes has been plagued by spurious findings, contamination artifacts, and vigorous scientific debates that have invalidated numerous high-profile studies. The central premise of this comparison guide is that the sensitivity and quantification approach chosen for microbial detection directly determines the validity of research outcomes in these challenging environments. The field has undergone a painful but necessary maturation as researchers recognize that standard methodologies suitable for high-biomass environments like stool yield misleading results when applied to low-biomass samples. This analysis systematically compares the key controversies, methodological limitations, and evolving best practices that have emerged from these parallel research domains, providing researchers with a framework for conducting robust low-biomass microbiome studies.

The Placental Microbiome Controversy

Paradigm Shift: From Sterile Womb to Colonized In Utero Environment

For more than a century, the prenatal environment was considered sterile under healthy conditions. This dogma was dramatically challenged in 2014 when a landmark study utilizing high-throughput sequencing reported a unique placental microbiome in 320 women, with bacterial phyla including Firmicutes, Tenericutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria detected in placental tissues [18]. The study suggested these microbial communities primarily originated from maternal oral microbiota and might seed a fetus's body with microbes before birth, giving rise to the "in utero colonization" hypothesis [4] [18]. This paradigm shift suggested the placenta was not sterile but contained specific, low-abundance microbial communities that differed compositionally from other human body sites.

However, this controversial finding was subsequently challenged by multiple studies that identified fundamental methodological flaws. Comprehensive reanalysis revealed that most signals attributed to placental microbes actually represented laboratory contamination from DNA extraction kits, reagents, and the laboratory environment—collectively known as the "kit-ome" [19]. A particularly rigorous 2019 study of over 500 placental samples found no evidence of a consistent microbial community after implementing stringent controls and contamination tracking. The researchers concluded that the few bacterial DNA sequences detected came either from contaminants or rare pathogenic infections [19].

Expert Consensus and Remaining Questions

Most experts in the field currently favor the "sterile womb" hypothesis, noting that the ability to generate germ-free mammals through Caesarean-section delivery and sterile rearing contradicts the concept of a consistent, transgenerationally transmitted placental microbiome [4]. As one expert noted, "The majority of evidence thus far does not support the presence of a bona fide resident microbial population in utero" [4]. The consensus is that any bacterial DNA detected in well-controlled studies likely represents transient microbial exposure rather than a true colonizing microbiota [4].

Table 1: Key Studies in the Placental Microbiome Debate

| Study Focus | Pro-Microbiome Findings | Contradictory Evidence | Methodological Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aagaard et al. (2014) | Reported distinct placental microbiome composition different from other body sites | Subsequent re-analysis found most signals were contamination | Inadequate controls for kit and reagent contamination; relative abundance profiling only |

| Microbial Origins | Suggested oral, gut, and vaginal microbiota as sources via hematogenous spread | No consistent demonstration of viable microbes from these sources | Unable to distinguish live vs. dead bacteria; potential sample contamination during delivery |

| Functional Potential | Proposed role in shaping fetal immune development | Germ-free mammals develop normally without placental microbes | No consistent metabolic activities demonstrated; low biomass precludes functional analysis |

The Tumor Microbiome Debate

High-Stakes Claims and Methodological Scrutiny

The tumor microbiome controversy mirrors many aspects of the placental microbiome debate but with even higher stakes given the potential implications for cancer diagnosis and treatment. A influential 2020 study analyzing 17,625 samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas claimed that 33 different cancer types hosted unique microbial signatures that could achieve near-perfect accuracy in distinguishing among cancers using machine learning classifiers [20] [21]. These findings suggested that intratumoral microbes could serve as powerful diagnostic biomarkers and potentially influence therapeutic responses.

Subsequent independent re-analysis revealed fundamental flaws in these findings. The claimed microbial signatures resulted from at least two critical methodological errors: (1) contamination in genome databases that led to millions of false-positive bacterial reads (most sequences identified as bacteria were actually human), and (2) data transformation artifacts that created artificial signatures distinguishable by machine learning algorithms [20]. When properly controlled, bacterial read counts were found to be inflated by orders of magnitude—in some cases by factors of 16,000 to 67,000 compared to corrected values [20].

Persistent Challenges in Tumor Microbiome Research

The tumor microbiome field continues to face substantial methodological challenges:

- Low Biomass Limitations: Tumor microbial signals are frequently comparable to or lower than contamination levels introduced during sample processing [21].

- Database Contamination: Microbial genome databases contain mislabeled sequences, including human DNA erroneously classified as bacterial [20].

- Sample Collection Artifacts: Surgical collection procedures inevitably introduce environmental microbes during tissue handling [21].

- Computational Artifacts: The use of machine learning on compositional data can create apparently accurate classifiers that detect technical artifacts rather than biological signals [20].

Despite these challenges, legitimate connections between specific microbes and cancers remain established. Certain pathogens like Helicobacter pylori (stomach cancer), Fusobacterium nucleatum (colorectal cancer), and human papillomavirus (cervical cancer) have validated causal roles in oncogenesis [21] [22].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Microbiome Detection Methods for Low-Biomass Samples

| Methodological Approach | Effective for High-Biomass Samples | Limitations for Low-Biomass Samples | Reported False Positive Rates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing (Relative) | Yes - signal dominates contamination | Contaminating DNA disproportionately affects results; compositionality artifacts | Up to 90% of reported signals in some tumor studies [20] |

| Shotgun Metagenomics (Relative) | Yes - comprehensive taxonomic profiling | Human DNA dominates (>95% of reads); database contamination issues | Millions of false-positive reads per sample due to human sequence misclassification [20] |

| Quantitative Microbiome Profiling (QMP) | Not necessary for abundant communities | Essential for low-biomass; requires internal standards and cell counting | Dramatically reduces false positives; reveals covariates like transit time dominate [23] |

| Microbial Culture | Limited value due to unculturable majority | Essential to confirm viability; but most bacteria unculturable | N/A - but negative culture doesn't prove absence |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Comparisons

Critical Experimental Design Considerations

Research in both placental and tumor microbiomes has converged on essential methodological requirements for low-biomass studies:

Contamination-Aware Sampling Protocols:

- Field Controls: Collection and processing of potential contamination sources (empty collection vessels, swabs exposed to sampling environment, aliquots of preservation solutions) [2]

- Personal Protective Equipment: Use of extensive PPE including gloves, masks, cleansuits to minimize operator-derived contamination [2]

- DNA-Free Materials: Use of pre-treated plasticware/glassware (autoclaved, UV-C sterilized) and DNA removal solutions (bleach, hydrogen peroxide) [2]

Laboratory Processing Controls:

- Extraction Controls: Multiple blank extraction controls processed alongside samples to identify kit and reagent contaminants [2] [19]

- Negative Controls: Paraffin blocks without tissue for FFPE samples; water controls for DNA extraction and amplification [22]

- Positive Controls: Minimal spike-in controls (e.g., Salmonella bongori) to verify detection sensitivity [19]

Computational Correction Methods:

- Contaminant Identification: Use of specialized packages like decontam to identify and remove external contaminants from sequencing data [22]

- Quantitative Normalization: Application of quantitative microbiome profiling instead of relative abundance to avoid compositionality artifacts [23]

- Cross-Validation: Use of multiple DNA extraction kits and sequencing techniques to cross-reference results [19]

Quantitative Profiling Revolution

Recent advances highlight the critical importance of quantitative microbiome profiling (QMP) over relative abundance approaches. A landmark 2024 colorectal cancer study demonstrated that when using QMP with rigorous confounder control, established microbiome cancer targets like Fusobacterium nucleatum showed no significant association with cancer stages after controlling for covariates like transit time, fecal calprotectin, and BMI [23]. This study revealed that these covariates explained more variance than cancer diagnostic groups, fundamentally challenging previous findings based on relative abundance profiling.

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows for Traditional vs. Quantitative Microbiome Profiling (QMP) in Low-Biomass Research. The green elements represent essential additions in the QMP approach that enable reliable low-biomass analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Controls for Low-Biomass Microbiome Studies

| Reagent/Control Type | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Blanks | Identifies reagent-derived contamination | Process empty tubes through identical extraction protocol alongside samples [2] |

| Negative Control Swabs | Detects environmental contamination during collection | Expose swabs to air in sampling environment; swipe sterile surfaces [2] |

| Positive Spike-in Controls | Verifies detection sensitivity and quantitative accuracy | Add known quantities of exotic bacteria (e.g., Salmonella bongori) not expected in samples [19] |

| UV-C Sterilized Reagents | Reduces background contaminant DNA | Treat all solutions and plasticware with UV-C light to degrade contaminating DNA [2] |

| DNA Degradation Solutions | Eliminates trace DNA from equipment | Use sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or commercial DNA removal solutions on surfaces [2] |

| Internal Standard Panels | Enables absolute quantification | Add known counts of synthetic DNA sequences or non-native bacteria to each sample [23] |

The parallel controversies in placental and tumor microbiome research highlight fundamental methodological principles for low-biomass microbial studies. First, relative abundance profiling is inadequate for low-biomass environments and must be replaced with quantitative approaches that enable distinction between true signal and contamination. Second, contamination-aware protocols with extensive controls must be implemented at every stage from sample collection through computational analysis. Third, biological covariates including transit time, inflammation markers, and host physiology often explain more variance than the primary experimental variables and must be rigorously controlled.

The field is moving toward consensus guidelines that emphasize minimum reporting standards for contamination controls, requirement of quantitative absolute abundance data rather than relative proportions, and implementation of rigorous statistical frameworks that properly account for compositionality and confounding factors [2]. These methodological refinements are essential to distinguish true biological signal from technical artifact in the challenging but potentially transformative study of low-biomass microbiomes.

Diagram 2: Evolution of Low-Biomass Microbiome Research Field. The field has progressed through predictable stages from initial discovery through controversy to methodological maturation, with color indicating the reliability stage (red = unreliable, yellow = transitional, green = reliable).

The Researcher's Toolkit: From 16S qPCR to Advanced Sequencing for Low-Biomass Quantification

In the study of microbial communities within low biomass environments—such as dry skin sites, sterile body fluids, or clean manufacturing surfaces—the accurate quantification and identification of microbial constituents present a formidable scientific challenge. Established microbiome analysis workflows, optimized for high microbial biomass samples like stool, often fail to accurately define microbial communities when applied to samples with minimal microbial DNA [24] [25]. The fundamental issue lies in the heightened susceptibility of low biomass samples to technical artifacts, including laboratory contamination, PCR amplification biases, and sequencing errors, which can severely distort the true biological signal [24]. Within this context, Targeted Amplicon Sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene remains a widely used tool due to its cost-effectiveness and database maturity. However, its performance must be critically evaluated against emerging alternatives like metagenomics and specialized quantitative PCR (qPCR) panels to guide researchers in selecting the optimal sensitivity and resolution for their specific low biomass applications. This guide objectively compares these methods, providing supporting experimental data and detailed protocols to maximize reliability from minimal input.

Method Comparison: Sensitivity and Taxonomic Resolution in Low Biomass

Performance Metrics Across Platforms

The selection of an appropriate method hinges on understanding their inherent strengths and limitations in a low biomass context. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of 16S amplicon sequencing against two alternative approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Microbiome Analysis Methods for Low Biomass Samples

| Method | Optimal Biomass Context | Sensitivity to Contamination | Taxonomic Resolution | Quantification Capability | Key Limitations in Low Biomass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | High Biomass | High - requires careful filtering [24] | Genus to Species-level (with full-length) [26] | Relative Abundance (biased by PCR) | Extreme bias toward dominant taxa; underestimates diversity [24] [25] |

| Shallow Metagenomics | Low & High Biomass | Moderate - less prone to amplification bias [24] | Species to Strain-level [24] | Relative Abundance | Higher cost per sample; complex data analysis |

| Species-specific qPCR Panels | Low & High Biomass | Low - enables absolute quantification with internal controls [26] | Species-level (pre-defined targets only) | Absolute Abundance [26] | Targeted nature limits discovery; pre-defined panel required |

Experimental Evidence from Controlled Studies

Direct comparisons in controlled studies reveal critical performance differences. A systematic analysis of skin swabs and mock community dilutions demonstrated that while 16S amplicon sequencing, metagenomics, and qPCR perform comparably on high biomass samples, their results diverge significantly at low microbial loads [24].

In low biomass leg skin samples, both metagenomic sequencing and qPCR revealed concordant, diverse microbial communities, whereas 16S amplicon sequencing exhibited extreme bias toward the most abundant taxon and significantly underrepresented true microbial diversity [24] [25]. This bias was quantified using Simpson's diversity index, which was significantly lower for 16S sequencing compared to both qPCR (P=6.2×10⁻⁵) and metagenomics (P=7.6×10⁻⁵) [24]. Furthermore, the overall composition of samples was more similar between qPCR and metagenomics than between qPCR and 16S sequencing (P=0.043), suggesting that metagenomics more accurately captures bacterial proportions in low biomass samples [24].

For pathogen identification in clinical samples, a study of 101 culture-negative samples found that next-generation sequencing (NGS) of the 16S rRNA gene using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) had a positivity rate of 72%, compared to 59% for Sanger sequencing [27]. ONT also detected more samples with polymicrobial presence (13 vs. 5), highlighting its superior sensitivity in complex, low-biomass diagnostic scenarios [27].

Advanced 16S Protocols for Enhanced Sensitivity

Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing with Micelle PCR

To overcome the limitations of standard 16S protocols, an advanced workflow utilizing full-length 16S gene amplification coupled with micelle PCR (micPCR) and nanopore sequencing has been developed. This protocol reduces time to results to 24 hours and significantly improves species-level resolution [26].

Table 2: Key Reagents for the Full-Length 16S micPCR Workflow

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Protocol Specification |

|---|---|---|

| MagNA Pure 96 DNA Viral NA Kit (Roche) | DNA extraction from clinical samples | Input: 200 µl sample; Elution: 100 µl [26] |

| LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix (NEB) | PCR amplification of long targets | Efficient generation of full-length (~1.5 kb) amplicons [26] |

| Custom 16S V1-V9 Primers | Amplification of full-length 16S rRNA gene | Forward: 5’-TTT CTG TTG GTG CTG ATA TTG CAG RGT TYG ATY MTG GCT CAG-3’Reverse: 5’-ACT TGC CTG TCG CTC TAT CTT CCG GYT ACC TTG TTA CGA CTT-3’ [26] |

| Nanopore Barcodes (SQK-PCB114.24) | Sample multiplexing | Allows pooling of up to 24 samples [26] |

| Oxford Nanopore Flongle Flow Cell | Long-read sequencing | Cost-effective for individual or small batches of samples [26] |

Experimental Protocol:

- DNA Extraction and QC: Extract DNA from 200 µl of sample using the MagNA Pure 96 system, eluting in a 100 µl volume. Quantify total 16S rRNA gene copies using a universal qPCR assay. Dilute extracts if necessary to contain a maximum of 10,000 16S rRNA gene copies/µl to prevent overloading micelles [26].

- Internal Calibrator (IC) Spike-in: Add 1,000 copies of Synechococcus 16S rRNA gene to all DNA extracts, including Negative Extraction Controls (NEC). This enables absolute quantification and background subtraction [26].

- First Round micPCR: Perform emulsion-based PCR with custom full-length 16S primers and LongAmp Taq MasterMix. Cycling conditions: 95°C for 2 min; 25 cycles of (95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, 65°C for 75 s); final extension at 65°C for 10 min [26].

- Amplicon Purification: Purify the resulting micPCR amplicons using AMPure XP beads at a 1:0.6 sample-to-bead ratio [26].

- Second Round Barcoding PCR: Perform a second PCR using nanopore barcodes and LongAmp Taq MasterMix. Use an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles with a touch-down annealing (starting at 50°C and increasing by 0.5°C per cycle for the first 10 cycles to 55°C), and extension at 65°C for 75 s [26].

- Sequencing and Analysis: Pool barcoded libraries and load onto a Flongle Flow Cell for sequencing on a MinION device. Analyze data using the Genome Detective or EPI2ME 16S workflow for taxonomic classification [26].

This micPCR approach compartmentalizes single DNA molecules within micelles, preventing chimera formation and PCR competition, thereby generating more robust and accurate microbiota profiles from limited input material [26].

Wet-Lab and Computational Best Practices for Low Biomass

- Rigorous Contamination Control: Process Negative Extraction Controls (NECs) alongside experimental samples in every batch. Use the internal calibrator in the micPCR protocol to enable absolute quantification and subtract contaminating DNA molecules present in reagents [26].

- Informed Contaminant Filtering: Leverage mock community dilution series to set abundance thresholds for taxa exclusion rather than relying solely on negative controls. This approach retains true low-abundance signal while removing contaminants, as the identity of all non-input species in mock samples is known [24].

- Full-Length Amplicon Advantage: Whenever possible, opt for primers that amplify the full-length 16S rRNA gene (V1-V9 regions). Long-read technologies from PacBio or Oxford Nanopore provide the enhanced discriminative power needed for species-level identification, which is frequently lacking in short-read (e.g., V4-only) approaches [26].

- Bioinformatic Vigilance: For data analysis, de novo assembly followed by BLAST against a curated database has been shown to be superior to OTU clustering or mapping approaches in terms of turnaround time and diagnostic accuracy for bacterial identification from clinical samples [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of a sensitive low-biomass 16S sequencing protocol depends on key reagents and kits. The following table details essential solutions, with an emphasis on those that enhance yield from minimal input.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Biomass 16S Sequencing

| Product Name | Supplier | Critical Function | Low-Biomass Specific Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Amplicon Barcoding Kit 24 V14 | Oxford Nanopore Technologies [29] | Full-length 16S amplification and barcoding | Inclusive primers boost taxa representation; enables multiplexing of 24 low-yield samples. |

| MagPure DNA Micro Kit | Magen [30] | High-efficiency DNA extraction from minimal sample | Optimized for small volumes; improves yield from challenging matrices. |

| LongAmp Hot Start Taq 2X Master Mix | New England Biolabs [26] [29] | Robust amplification of long targets | Efficiently generates full-length (~1.5 kb) 16S amplicons from fragmented, low-concentration DNA. |

| CleanPlex NGS Target Enrichment | Paragon Genomics [31] | Ultra-sensitive amplicon sequencing | Provides direct amplification sensitivity at the single-cell level for minimal input. |

| Quick-16S Full-Length Library Prep Kit | Zymo Research [31] | Rapid library preparation | Streamlines workflow to under 30 minutes hands-on time, reducing handling errors for precious samples. |

| AMPure XP Beads | Beckman Coulter [29] | PCR clean-up and size selection | Highly consistent purification and concentration of low-abundance amplicon libraries. |

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community DNA Standard | Zymo Research [28] | Mock community for QC | Provides a defined, low-biomass standard to validate workflow sensitivity and accuracy. |

No single microbiome analysis method is universally superior; the optimal choice is dictated by the specific research question, sample type, and available resources. The experimental data and protocols presented here provide a roadmap for optimizing 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing for low biomass contexts.

For discovery-driven research in low biomass environments where the microbial constituents are unknown, shallow metagenomics is often the most appropriate tool, providing superior strain-level resolution without amplification bias [24]. When research questions are focused on a pre-defined set of taxa and absolute quantification is critical, species-specific qPCR panels are the gold standard due to their sensitivity and ability to control for contamination [26]. Targeted 16S amplicon sequencing, particularly in its advanced forms using full-length genes and micelle PCR, occupies a vital niche, offering a cost-effective and increasingly accurate solution for broad taxonomic profiling when meticulous contamination controls and optimized protocols are rigorously applied [24] [26] [25].

The analysis of low-biomass microbial communities presents unique methodological challenges for researchers studying environments such as human milk, fish gills, respiratory specimens, and other microbiota-sparse niches. In these contexts, where microbial DNA represents a minor component amid substantial host DNA and potential contaminants, standard 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing approaches face significant limitations due to their compositional nature and susceptibility to contamination artifacts. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) has emerged as an indispensable tool for pre-screening low-biomass samples, providing absolute quantification of 16S rRNA gene copies to determine whether sufficient microbial DNA is present to warrant downstream sequencing analyses. This guide objectively compares the performance of qPCR against alternative quantification methods and provides experimental data supporting its critical role in robust experimental design for low-biomass microbiome research.

Performance Comparison of Quantification Methods

Method Capabilities and Technical Specifications

| Method | Quantification Type | Limit of Detection | Dynamic Range | Cost per Sample | Throughput | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR | Absolute | 10³–10⁴ cells/g feces [9] | 5–6 logs [9] | Low | Medium-high | Pre-screening biomass; Absolute quantification; Broad applications |

| ddPCR | Absolute | Similar to qPCR [9] | Narrower than qPCR [9] | High | Medium | Low-abundance targets; Inhibitor-rich samples |

| 16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing | Relative (Compositional) | Higher than qPCR [9] | Limited [9] | High | High | Community profiling; Diversity analysis |

| Flow Cytometry | Absolute | Varies with biomass | Limited | Medium | High | Cell counting; Viability assessment |

Experimental Data from Comparative Studies

| Study Context | qPCR Performance | Alternative Method | Key Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human fecal samples spiked with L. reuteri | LOD: ~10⁴ cells/g feces; Excellent linearity (R² > 0.98) | ddPCR | qPCR showed comparable sensitivity, wider dynamic range, lower cost | [9] |

| Raclette du Valais PDO cheese microbiota | Reliable quantification of dominant community members | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing | HT-qPCR provided complementary absolute quantification to sequencing data | [32] |

| Fish gill microbiome (low-biomass) | Enabled screening based on 16S rRNA copy number; Improved sequencing success | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing | Quantification prior to library construction improved diversity capture | [14] |

| Human milk microbiome (low-biomass) | Effective despite high host DNA background | Metagenomic sequencing | qPCR reliably characterized milk microbiota where metagenomics struggled | [33] |

Experimental Protocols for qPCR Implementation

DNA Extraction Optimization for Low-Biomass Samples

Effective pre-screening begins with optimized DNA extraction. Comparative studies have evaluated multiple approaches specifically for challenging low-biomass samples:

Kit Performance Comparison: In human milk samples, the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro (PS) kit and MagMAX Total Nucleic Acid Isolation (MX) kit provided consistent 16S rRNA gene sequencing results with low contamination, whereas other tested kits showed greater variability [33]. Similar optimization was demonstrated for nasopharyngeal specimens, where the DSP Virus/Pathom Kit (Kit-QS) better represented hard-to-lyse bacteria compared to the ZymoBIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit (Kit-ZB) [34].

Inhibition Management: Samples should be assessed for PCR inhibitors including hemoglobin, polysaccharides, ethanol, phenol, and SDS, which can flatten efficiency plots and reduce accuracy [35]. Spectrophotometric measurement (A260/A280 ratios >1.8 for DNA) or sample dilution can identify and mitigate inhibition effects.

Standard Preparation: For prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene quantification, circular plasmid standards yield similar gene estimates as linearized standards, simplifying standard preparation without gross overestimation concerns [36].

qPCR Assay Design and Validation

Robust qPCR implementation requires careful assay design and validation:

Reaction Components: Probe-based qPCR (e.g., TaqMan) is recommended over intercalating dye-based approaches due to superior specificity, particularly for low-biomass samples where background signals may be problematic [37]. Typical 50μL reactions contain up to 900nM each forward and reverse primer, up to 300nM probe, 1× master mix, and up to 1000ng sample DNA [37].

Thermal Cycling Parameters: Standard protocols include initial enzyme activation at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30-60 seconds [37].

Validation Parameters: Assays should demonstrate efficiency between 90-110%, with a correlation coefficient (R²) >0.98 across a minimum 5-log dynamic range. Efficiency calculations should be based on the slope of the standard curve (E = -1+10^(-1/slope)) [35].

Pre-Screening Implementation and Threshold Determination

The operational implementation of qPCR pre-screening requires establishing validated thresholds:

Threshold Determination: In fish gill microbiome studies, establishing minimum 16S rRNA gene copy thresholds (e.g., >500 copies/μL) significantly improved downstream sequencing success by excluding samples with insufficient biomass [14]. Similarly, nasopharyngeal specimens with <500 16S rRNA gene copies/μL showed reduced sequencing reproducibility and higher similarity to no-template controls [34].

Multi-stage Screening: For critical applications, a two-stage screening approach is recommended: initial rapid screening with a broad-specificity 16S rRNA gene assay, followed by targeted quantification of specific taxa of interest for samples passing initial quality thresholds.

Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Pre-Screening

| Reagent Category | Specific Products | Function in Pre-Screening | Considerations for Low-Biomass |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy PowerSoil Pro (Qiagen), MagMAX Total Nucleic Acid Isolation (Thermo Fisher) | Maximize microbial DNA yield; Minimize contamination | Select kits with inhibitor removal technology; Validate with low-biomass mock communities |

| qPCR Master Mixes | TaqMan Universal Master Mix II, inhibitor-resistant formulations | Enable robust amplification despite inhibitors | Prioritize mixes tolerant to common inhibitors (hemoglobin, polysaccharides) |

| Quantification Standards | gBlock Gene Fragments, cloned plasmid standards | Absolute quantification reference | Circular plasmids sufficient for prokaryotic 16S rRNA gene quantification [36] |

| Primer/Probe Sets | Broad-range 16S rRNA primers (e.g., 338F/518R), taxon-specific designs | Target amplification for quantification | Validate specificity with in silico analysis and control samples |

Workflow Integration and Decision Pathway

The following workflow illustrates the integration of qPCR pre-screening into low-biomass research:

qPCR-based quantification of 16S rRNA gene copies represents a critical, cost-effective tool for pre-screening low-biomass samples prior to downstream sequencing analyses. The method provides absolute quantification that overcomes the compositional limitations of amplicon sequencing, enables objective quality control thresholds, and significantly improves the reliability and interpretability of low-biomass microbiome studies. While emerging technologies like ddPCR offer advantages for specific applications, qPCR remains the most practical and broadly accessible approach for routine pre-screening implementation. By integrating the experimental protocols and quality control measures outlined in this guide, researchers can dramatically improve the success rate and reproducibility of their low-biomass microbiome research.

Whole Metagenome Sequencing (WMS) has become an indispensable tool for uncovering the taxonomic composition and functional potential of microbial communities. However, its application to samples with high host DNA content or low microbial biomass—such as those from the nasopharynx, skin, or blood—presents significant challenges. In the context of low biomass research, the sensitivity of a method is paramount. This guide objectively compares the performance of various experimental and computational protocols designed to navigate the limitations of high host DNA and stringent input requirements, providing researchers with a framework to select the most appropriate methods for their specific samples.

The Core Challenges in WMS

The primary obstacles in sequencing low-biomass, high-host-content samples are twofold. First, the predominance of host DNA can drastically reduce sequencing efficiency; in samples like nasopharyngeal aspirates, host DNA can constitute over 99% of the total DNA, severely limiting the number of reads available for microbial profiling [38]. Second, standard WMS protocols often require substantial DNA input (typically ≥50 ng), which can be impossible to obtain from low-biomass environments [13]. These factors combine to decrease sensitivity and accuracy, particularly for detecting low-abundance species [39].

Comparative Performance of Solutions

The following table summarizes key solutions and their performance based on controlled experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Strategies for Managing High Host DNA and Low Input in WMS

| Method / Kit Name | Method Type | Reported Performance Data | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolYsis + MasterPure [38] [40] | Host DNA depletion + DNA extraction | • Host DNA reduced from 99% to as low as 15%• 7.6 to 1,725.8-fold increase in bacterial reads [38] | Effective host DNA removal; improved Gram-positive recovery. | Variable performance; requires optimization. |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit [41] | DNA Extraction | • Yields smaller fraction of Homo sapiens reads across body sites [41] | Effective at reducing host reads; good for fungal DNA. | Biases microbial community representation [41]. |

| PowerSoil Pro Kit [41] | DNA Extraction | • Best at approximating expected proportions in mock communities [41] | Accurate taxonomic profiling; minimizes bias. | Performance may vary with sample type. |

| 2bRAD-M [13] | Sequencing Library Prep | • Works with merely 1 pg of total DNA or 99% host contamination• High precision (98.0%) and recall (98.0%) [13] | Ultra-low input; resistant to host DNA and degradation; cost-effective. | Relies on reference genomes; not for novel organism discovery. |

| WMS with GC & Length Normalization [42] | Bioinformatics (Post-sequencing) | • Four-fold reduction in Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) in validation sets [42] | Corrects sequencing biases; improves abundance estimates. | Requires complete microbial genome references. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Host DNA Depletion and DNA Extraction

The following combined protocol, optimized for nasopharyngeal aspirates from premature infants, demonstrates a robust method for handling high-host-content, low-biomass samples [38] [40].

Protocol Name: Mol_MasterPure

Host DNA Depletion Kit: MolYsis Basic5 DNA Extraction Kit: MasterPure Gram Positive DNA Purification Kit

Deviations from Manufacturer’s Protocol: For a 2 ml sample, the volumes of reagents used in the initial steps of the MolYsis protocol were doubled [38].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Host DNA Depletion: The sample is treated with MolYsis Basic5 reagents. The kit employs a proprietary lysis buffer that selectively lyses human cells but not bacterial cells. Following lysis, DNase is added to degrade the released host DNA.

- Microbial Lysis: The remaining microbial cells are pelleted and then lysed using the MasterPure Gram Positive kit, which includes rigorous mechanical and chemical lysis steps to break down tough Gram-positive bacterial cell walls.

- DNA Purification: The microbial DNA is purified according to the MasterPure protocol, which involves protein precipitation and DNA isolation via centrifugation.