Next-Generation Pathogen Detection: Advanced Strategies for Maximizing Assay Sensitivity

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the sensitivity of pathogen detection assays.

Next-Generation Pathogen Detection: Advanced Strategies for Maximizing Assay Sensitivity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the sensitivity of pathogen detection assays. Covering foundational principles to real-world application, it explores cutting-edge CRISPR methodologies, synthetic biology, and liquid biopsy advancements. The content delivers actionable strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, optimizing assay performance, and conducting rigorous clinical validation. By integrating the latest research and comparative analyses, this resource aims to bridge the gap between laboratory innovation and clinically viable, high-sensitivity diagnostic tools.

The Science of Signal and Noise: Core Principles of High-Sensitivity Detection

In the field of molecular diagnostics, a significant sensitivity gap exists between detection methods for nucleic acid biomarkers and those for protein biomarkers. While techniques like PCR can detect nucleic acids at attomolar to femtomolar concentrations, conventional protein detection methods like the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) typically achieve detection limits only in the nanomolar to picomolar range [1]. Bridging this gap is critical for advancing in vitro diagnostics, particularly for infectious diseases where sensitive pathogen detection can dramatically improve early intervention and treatment outcomes [2] [3]. This technical resource center provides methodologies and troubleshooting guides to help researchers implement advanced techniques that enhance detection sensitivity for both classes of biomarkers.

Sensitivity Comparison of Detection Methods

The table below summarizes the typical sensitivity ranges for various biomarker detection techniques, highlighting the performance gap between conventional and advanced methods.

| Detection Method | Biomarker Type | Typical Limit of Detection | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional ELISA [1] | Protein | Nanomolar to Picomolar | General protein biomarker detection |

| Digital PCR [4] | Nucleic Acid | Single Molecule (e.g., 0.1% VAF) | Rare mutation detection, liquid biopsy |

| BEAMing [4] | Nucleic Acid | 0.01% Variant Allele Frequency | Ultra-rare variant quantification |

| Immuno-PCR [5] | Protein | Femtomolar (e.g., 2 fM BSA) | High-sensitivity protein detection |

| NATA-ELISA [1] | Protein | Femtomolar | Early disease diagnosis |

| ActCRISPR-TB [3] | Nucleic Acid | 5 copies/μL | Sensitive pathogen DNA detection |

Enhanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Nucleic Acid-Templated Target Amplification (NATA)-ELISA

This protocol enhances traditional ELISA sensitivity by several hundred-fold through in-situ amplification of the protein biomarker itself, inspired by viral replication mechanisms [1].

- Step 1: Capture Antigen. Coat wells with a capture antibody specific to your target protein biomarker. Incubate with the sample to allow antigen binding.

- Step 2: Bind DNA-Labelled Antibody. Incubate with a biotinylated detection antibody. Subsequently, add a complex of streptavidin and a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) template. This ssDNA encodes the target biomarker (for direct amplification) or a universal reporter protein like Streptococcal protein G with an Avi-tag (for surrogate amplification).

- Step 3: Cell-Free Protein Synthesis. Add a cell-free protein synthesis system to the well. This system will use the tethered DNA template to synthesize new copies of the protein.

- Step 4: Detect Synthesized Protein. The newly synthesized proteins will bind to adjacent, unoccupied capture antibodies on the surface. Detect these bound proteins using a conventional ELISA detection system (e.g., an HRP-streptavidin conjugate for an Avi-tagged surrogate).

Troubleshooting:

- High Background Signal: Ensure thorough washing between steps, particularly after adding the DNA-labelled antibody complex. Optimize the concentration of the cell-free synthesis components.

- Low Signal Amplification: Check the activity of the cell-free protein synthesis system. Verify the integrity and functionality of the DNA template conjugated to the detection antibody.

Protocol 2: One-Pot Asymmetric CRISPR Assay (ActCRISPR)

This protocol describes a sensitive, one-pot nucleic acid detection method, optimized for pathogen DNA, that favors trans-cleavage to improve signal [3].

- Step 1: Assemble Reaction. In a single tube, combine the sample DNA with recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) reagents (500 nM primers, 16.8 nM Mg²⁺) and CRISPR reagents (40 nM Cas12a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) pre-complexed with multiple guide RNAs favoring trans-cleavage, and 600 nM ssDNA reporter).

- Step 2: Isothermal Amplification & Detection. Incubate the reaction at 37-40 °C for 45-60 minutes. The RPA will isothermally amplify the target pathogen DNA. The Cas12a RNP will bind the amplicon and exhibit collateral trans-cleavage of the reporter, generating a fluorescent or lateral flow signal.

- Step 3: Read Results. Measure fluorescence in real-time or at the endpoint. For lateral flow, dip the strip into the reaction mixture and read the visual bands.

Troubleshooting:

- Attenuated or Delayed Signal: This may be due to excessive cis-cleavage (degradation of the amplicon). Titrate the ratios of the multiple gRNAs to further favor trans-cleavage activity. gRNAs targeting non-canonical PAM sites often exhibit this desirable asymmetric activity [3].

- Low Amplification Efficiency: Optimize the concentration of Mg²⁺ and primers in the RPA reaction. Ensure the reaction temperature is maintained consistently within 36-40 °C.

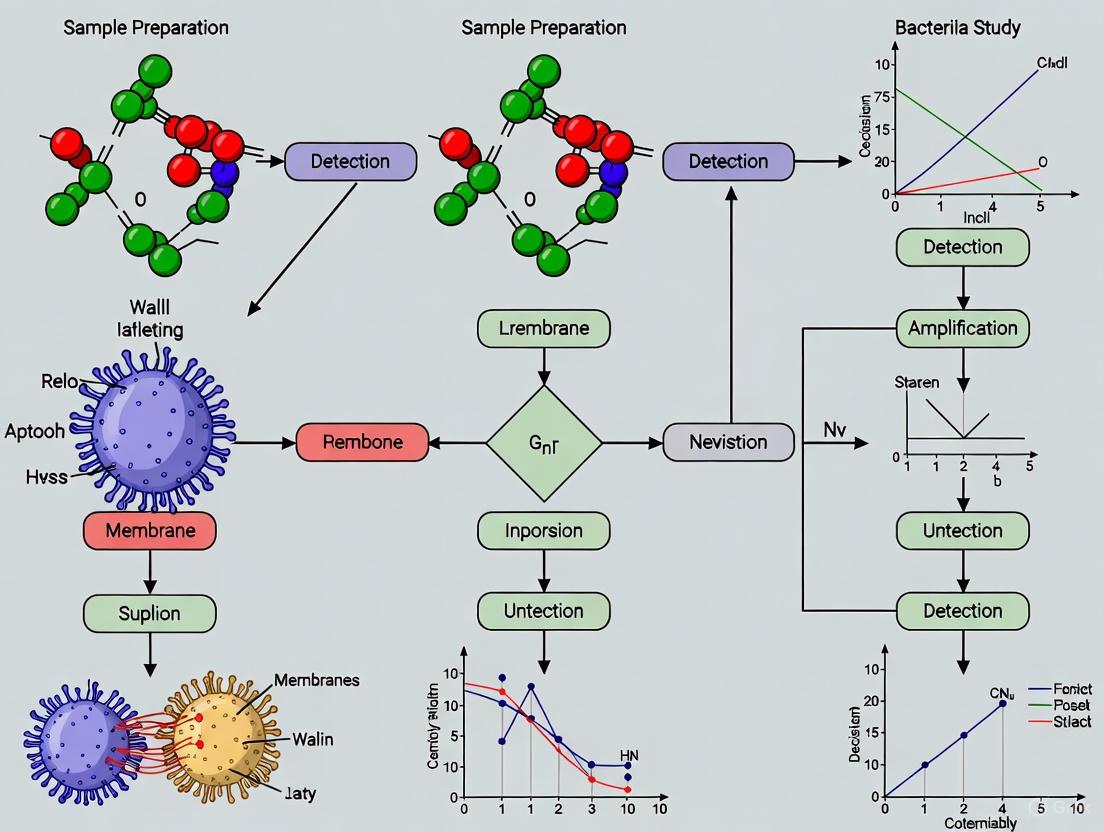

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for the advanced protocols described above.

NATA-ELISA Workflow

One-Pot ActCRISPR Workflow

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

The table below lists key reagents required for implementing the advanced sensitivity-bridging techniques discussed.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis System [1] | An in vitro system for protein production without living cells, enabling target amplification in NATA-ELISA. | NATA-ELISA |

| DNA-Encoded Antibodies [1] | Detection antibodies conjugated to a DNA template that serves as a blueprint for the target protein or a surrogate. | NATA-ELISA, Immuno-PCR |

| Cas12a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) [3] | A CRISPR-associated complex that binds specific DNA sequences and cleaves a reporter molecule upon activation. | ActCRISPR Assay |

| Trans-Cleavage Favouring gRNAs [3] | Guide RNAs designed to minimize cis-cleavage of the amplicon while maintaining high trans-cleavage activity for signal generation. | ActCRISPR Assay |

| Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) Kit [3] | An isothermal nucleic acid amplification kit used for rapid target DNA amplification at constant temperature. | ActCRISPR Assay |

| Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) Reporter [3] | A short ssDNA molecule labeled with a fluorophore/quencher pair; cleavage by Cas12a generates a fluorescent signal. | ActCRISPR Assay |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is there a inherent sensitivity gap between nucleic acid and protein detection methods? The gap primarily exists because of the availability of enzymatic amplification techniques like PCR for nucleic acids, which can exponentially copy a single target molecule. Until recently, no equivalent method existed for proteins, leaving immunoassays like ELISA to rely on signal amplification from a single enzyme molecule [4] [1].

Q2: What are the main advantages of one-pot CRISPR assays over traditional PCR-based methods for nucleic acid detection? One-pot CRISPR assays, like ActCRISPR, integrate target amplification and detection into a single tube. This simplifies the workflow, reduces contamination risk, and can be faster, making it highly suitable for point-of-care or resource-limited settings [3].

Q3: My NATA-ELISA experiment shows high background. What could be the cause? High background in NATA-ELISA is often due to non-specific binding of the DNA-antibody conjugate or uncontrolled protein synthesis. Ensure stringent washing conditions after each binding step and titrate the components of the cell-free expression system to minimize off-target activity [1].

Q4: Can these advanced protein detection methods be multiplexed to detect several biomarkers at once? Yes, methods like NATA-ELISA and Immuno-PCR are inherently suited for multiplexing. By using DNA tags with unique sequences for different antibodies, you can detect multiple targets simultaneously in a single well using a universal detection system, such as a surrogate protein or different PCR amplicons [5] [1].

Q5: How does the use of multiple gRNAs in a CRISPR assay improve sensitivity? Using multiple gRNAs that target different sites on the same amplicon can enhance the overall trans-cleavage activity and signal strength. However, the gRNA combination must be carefully optimized to ensure they do not have strong cis-cleavage activity that would degrade the amplicon and reduce sensitivity [3].

CRISPR-Cas systems have revolutionized biological research and diagnostic applications. Among these, the Class 2 Type V and Type VI systems—featuring the effector proteins Cas12a and Cas13, respectively—exhibit a unique trans-cleavage activity that has been particularly transformative for nucleic acid detection. This activity, triggered upon recognition of a specific target sequence, enables these enzymes to cleave surrounding non-target nucleic acids indiscriminately, providing a powerful signal amplification mechanism. Within the context of improving sensitivity in pathogen detection assays, understanding the distinct properties, troubleshooting common experimental issues, and optimizing the use of Cas12a and Cas13 is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals. This technical support center provides a detailed guide to navigating these powerful systems.

Core System Fundamentals: Cas12a vs. Cas13

What are the fundamental operational differences between Cas12a and Cas13?

Cas12a and Cas13 are both RNA-guided effector proteins from Class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems but target different nucleic acids and possess distinct mechanisms. The table below summarizes their key characteristics, which are crucial for selecting the appropriate system for your application.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Cas12a and Cas13

| Feature | Cas12a (Type V-A) | Cas13 (Type VI) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Target | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) [6] [7] | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) [8] [9] |

| Trans-cleavage Substrate | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) [10] [7] | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) [8] [9] |

| PAM Requirement | Yes (e.g., 5'-TTTV-3') [6] [7] | No PAM; instead, has protospacer flanking site (PFS) preferences [10] |

| Guide RNA | Single crRNA (no tracrRNA needed) [6] [7] | Single crRNA [8] |

| Native Function | Bacterial adaptive immunity against DNA viruses and plasmids [6] | Bacterial adaptive immunity against RNA viruses [8] |

| Key Diagnostic Application | DNA detection (e.g., HPV, SARS-CoV-2 DNA) [10] | RNA detection (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 RNA) [9] [10] |

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism and trans-cleavage activity for each system.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My Cas12a-based detection assay has low sensitivity. What could be wrong?

Low sensitivity often stems from suboptimal Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) recognition, inefficient crRNA design, or inadequate signal amplification. The PAM sequence (typically 5'-TTTV-3' for Cas12a) is absolutely required for initial target DNA recognition and unwinding [6] [7]. If your target DNA lacks a compatible PAM, Cas12a will not bind. Furthermore, ensure your crRNA spacer sequence is specific and has minimal potential for off-target binding. For detecting low-abundance targets, always couple the CRISPR reaction with a pre-amplification step like Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) or Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) [10]. The "HOLMES" and "DETECTR" platforms are examples of Cas12a assays that use pre-amplification to achieve attomolar (aM) sensitivity [9] [10].

FAQ 2: Why is my Cas13 assay producing high background (false positive) signals?

High background in Cas13 assays is frequently caused by reagent contamination or non-specific activation of the Cas13 protein. Cas13's trans-cleavage activity is powerfully activated upon binding its specific RNA target, but it can sometimes be triggered non-specifically. To troubleshoot:

- Meticulous Lab Practice: Use dedicated pre- and post-amplification workspaces and UV irradiation to degrade contaminating nucleic acids.

- Optimize crRNA: Ensure your crRNA does not have significant homology to non-target sequences present in the reaction. A single mismatch may not always prevent activation, but double mismatches, especially at positions 3-5, can significantly reduce it [11].

- Check Reporter Integrity: Degraded or improperly quenched fluorescent reporters can lead to high background. Aliquot and store reporters properly.

FAQ 3: Can I use Cas12a and Cas13 in a single reaction for multiplexed detection?

Yes, the distinct nucleic acid targets (DNA for Cas12a, RNA for Cas13) and trans-cleavage substrates (ssDNA reporter for Cas12a, ssRNA reporter for Cas13) allow for multiplexing in a single pot [10]. This enables the simultaneous detection of a DNA virus and an RNA virus, for example. The key is to use two different reporters—for instance, one ssDNA reporter labeled with a HEX fluorophore and one ssRNA reporter labeled with a FAM fluorophore. Each will be cleaved exclusively by the activated Cas12a or Cas13 system, respectively, allowing for independent signal detection on different channels.

FAQ 4: How does RNA secondary structure affect my Cas13 assay, and how can I mitigate it?

RNA structure can significantly inhibit Cas13 activity by blocking access of the Cas13-crRNA complex to the target protospacer [12]. Structured regions compete with the crRNA for base pairing. A recent study quantitatively explained this through a kinetic strand displacement model, where Cas13 must displace the occluding structure to bind, which can reduce activity by an order of magnitude or more [12]. To mitigate this:

- crRNA Design: Use computational tools to predict secondary structure in your target RNA and design crRNAs that target regions with minimal predicted structure.

- Use Multiple crRNAs: Employing a pool of crRNAs targeting different regions of the same RNA increases the probability that at least one will access an unstructured site, enhancing overall sensitivity [11].

- Assay Conditions: Incubating the reaction at a higher temperature (e.g., 50-55°C for LwaCas13a) can help melt secondary structures, though this must be balanced with enzyme stability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Low Signal in Cas12a/Cas13 Detection Assays

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Signal in Trans-cleavage Assays

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No or Weak Signal | 1. Target concentration below limit of detection.2. Inefficient or failed pre-amplification.3. Suboptimal Mg²⁺ concentration.4. Incorrect PAM (for Cas12a) or problematic PFS (for Cas13).5. crRNA designed against a highly structured region (Cas13). | 1. Include a pre-amplification step (RPA/LAMP/PCR). Validate amplification separately.2. Titrate Mg²⁺, as it is a critical cofactor for both amplification and Cas activity.3. Verify the target sequence contains a valid PAM (e.g., TTTV) [7]. For Cas13, avoid a G base immediately following the protospacer [10].4. Re-design crRNA to target a different, more accessible site. |

| Inconsistent Signal Between Replicates | 1. Pipetting errors with viscous samples or reagents.2. Inefficient mixing of reaction components.3. Fluctuations in isothermal amplification temperature. | 1. Use master mixes for critical reagents to minimize pipetting variability.2. Centrifuge tubes briefly before incubation and vortex thoroughly.3. Use a calibrated heat block or water bath. |

| Signal is Delayed | 1. Low reaction temperature.2. Suboptimal crRNA:target ratio.3. Partially inactive protein or nucleasedamaged reporters. | 1. Ensure the reaction is performed at the optimal temperature for the Cas ortholog (e.g., 37-42°C for LbCas12a).2. Titrate the crRNA concentration.3. Use fresh, high-quality reagents. |

Troubleshooting Specificity Issues: False Positives and Off-Target Effects

Table 3: Troubleshooting Specificity Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| False Positive (No target control is positive) | 1. Amplicon or nucleic acid contamination.2. Non-specific activation of Cas protein.3. Impure oligonucleotide synthesis. | 1. Implement strict physical separation of pre- and post-amplification areas. Use uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) treatment to carryover contamination.2. Include an appropriate negative control crRNA (targeting a non-existent sequence).3. Purify crRNAs and oligos via HPLC or PAGE. |

| Inability to Discriminate Single-Nucleotide Variants (SNPs) | 1. crRNA tolerance to single mismatches.2. Over-amplification leading to high target concentration that saturates the system. | 1. Intentionally design crRNAs with a mismatch at the SNP site or utilize an "occluded" Cas13 design that enhances mismatch discrimination [12].2. Reduce the number of amplification cycles or time and titrate the amplified product volume added to the CRISPR reaction. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: SHERLOCK-like Assay for SARS-CoV-2 RNA Detection using Cas13

This protocol is adapted from the SHERLOCK (Specific High-sensitivity Enzymatic Reporter unLOCKing) platform, which is designed for highly sensitive and specific RNA detection [9] [10].

Principle: Target RNA is first converted to DNA and isothermally amplified. The amplicon is then transcribed back to RNA, which is detected by the Cas13-crRNA complex. Activation of Cas13 upon target binding leads to trans-cleavage of an RNA reporter, generating a fluorescent signal.

Workflow:

Materials & Reagents:

- Purified LwaCas13a or LbuCas13a protein

- Target-specific crRNA: Designed against a conserved region of the SARS-CoV-2 genome (e.g., N-gene or E-gene).

- RT-RPA Kit: For combined reverse transcription and isothermal amplification.

- T7 RNA Polymerase: For in vitro transcription.

- Fluorescent RNA Reporter: A short ssRNA oligonucleotide labeled with a 5' fluorophore (e.g., FAM) and a 3' quencher (e.g., Iowa Black FQ).

- Nuclease-free water and tubes.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation & Amplification:

- In a first reaction tube, set up a 50 µL RT-RPA reaction according to the manufacturer's instructions, using primers designed to amplify a ~100-200 bp region of the SARS-CoV-2 genome. Include a T7 promoter sequence in the forward primer.

- Incubate the RT-RPA reaction at 42°C for 20-30 minutes.

Cas13 Detection Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a master mix for the detection reaction on ice. For a single 20 µL reaction:

- 1 µL Cas13 protein (100-200 nM)

- 1 µL crRNA (100-200 nM)

- 1 µL RNA Reporter (100-200 nM)

- 11.5 µL Nuclease-free water

- 0.5 µL Ribonuclease Inhibitor (optional)

- Aliquot 15 µL of the master mix into a new tube or plate.

- Prepare a master mix for the detection reaction on ice. For a single 20 µL reaction:

Reaction Initiation & Readout:

- Add 5 µL of the completed RT-RPA reaction (or a 1:10 dilution thereof) to the 15 µL detection master mix.

- Mix thoroughly by pipetting and briefly centrifuge.

- Immediately transfer to a real-time PCR instrument or fluorescent plate reader.

- Incubate at 37°C and measure fluorescence every 30 seconds for 10-30 minutes.

- A sharp increase in fluorescence over time indicates a positive detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Detection

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cas12a/Cas13 Effector Protein | The core enzyme that, upon target recognition, performs cis- and trans-cleavage. Common orthologs include LbCas12a and AacCas12b; LwaCas13a and LbuCas13a [9] [13]. |

| crRNA (CRISPR RNA) | A short RNA molecule consisting of a direct repeat (scaffold) that binds the Cas protein and a spacer sequence that guides it to the target nucleic acid. It requires only a single RNA for both Cas12a and Cas13 [6] [8]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter | A quenched oligonucleotide (ssDNA for Cas12a, ssRNA for Cas13) that, when cleaved during trans-cleavage, produces a fluorescent signal. This is the primary detection readout [9] [10]. |

| Isothermal Amplification Kits (RPA/LAMP) | Enzymatic kits for amplifying nucleic acids at a constant temperature, enabling simple instrumentation and coupling with CRISPR detection in one-pot or two-step assays [10]. |

| Microfluidic Chamber Array | A device containing millions of femtoliter-sized chambers used in digital detection methods (e.g., SATORI) to achieve single-molecule sensitivity without target pre-amplification, reducing errors and time [11]. |

| Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) | An enzyme used in pre-amplification steps to prevent carryover contamination by degrading uracil-containing DNA amplicons from previous reactions. |

| Ribonuclease Inhibitor | A protein added to Cas13 reactions to protect the crRNA, target RNA, and RNA reporter from degradation by environmental RNases. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in One-Pot Assay Development

FAQ 1: Why does my one-pot CRISPR assay show delayed or attenuated signal compared to my two-step assay?

Problem: The integrated one-pot assay exhibits slower signal generation and reduced overall signal intensity, limiting detection sensitivity.

Root Cause: This is primarily due to competitive cis-cleavage activity of the Cas protein on the RPA amplicon. In a one-pot reaction, the Cas complex (e.g., Cas12a) binds to the target sequence and can cleave both the amplicon itself (cis-cleavage, which degrades the target) and the fluorescent reporter (trans-cleavage, which generates signal). Excessive cis-cleavage depletes the amplicon before significant amplification can occur, undermining the assay's efficiency [14] [3].

Solutions:

- Utilize guide RNAs (gRNAs) with asymmetric cleavage activity: Select or design gRNAs that favor trans-cleavage over cis-cleavage. These are often gRNAs targeting sequences with non-canonical Protospacer Adjacent Motifs (PAMs). For example, in a tuberculosis assay (ActCRISPR-TB), gRNA-5 demonstrated superior kinetics because its trans-cleavage activity was preserved while its cis-cleavage activity was weakened [14] [3].

- Employ a multi-guide RNA strategy: Combine multiple gRNAs that favor trans-cleavage and target distinct sites on the amplicon. A combination of gRNA-2, -3, and -5 in the ActCRISPR-TB assay achieved a limit of detection (LoD) of 5 copies/μL, which was 20 times more sensitive than using a canonical gRNA (gRNA-0) alone [14] [3].

- Implement thermal regulation: Use Cas proteins with different temperature optima to temporally separate the amplification and detection phases. The TRACE assay uses Cas12b. An initial lower temperature (37°C) favors RPA amplification, while a subsequent temperature shift (to 60°C) maximizes Cas12b detection activity, preventing amplicon degradation during the critical amplification phase [15].

- Use a single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) blocker: To further prevent early Cas activity, an ssRNA complementary to the gRNA spacer region can be added. This blocker binds the gRNA during the amplification phase, inhibiting Cas RNP complex formation and cis-cleavage. It dissociates upon a temperature increase, restoring full Cas activity for detection [15].

FAQ 2: My one-pot assay has high background noise. How can I improve the signal-to-noise ratio?

Problem: The assay produces significant signal even in no-template control samples, leading to potential false positives and difficulty in interpreting weak positive results.

Root Cause: High background can stem from several factors, including non-specific amplification, premature trans-cleavage activity triggered by non-target molecules, or suboptimal reagent concentrations.

Solutions:

- Optimize guide RNA specificity: Carefully design gRNAs to ensure high target specificity and avoid off-target binding. Use bioinformatics tools to check for unique sequences within the target genome and minimize homology with non-target sequences [14] [16].

- Fine-tune Mg²⁺ concentration: Increasing Mg²⁺ concentration can reduce assay signal and background. Systematically titrate Mg²⁺ to find the level that minimizes background without compromising the true positive signal [14] [3].

- Adjust reporter concentration: While a 600 nM reporter concentration was selected in the ActCRISPR-TB assay to minimize background and cost, testing different concentrations can help optimize the signal-to-noise ratio for your specific setup [14] [3].

- Validate gRNAs for primer overlap: Ensure your gRNA sequences do not overlap with the RPA primer sequences, as this can cause template-independent signal generation and high background, as was observed with gRNA-6 in the ActCRISPR-TB study [14] [3].

FAQ 3: How can I adapt my one-pot assay for point-of-care use with lateral flow readout?

Problem: The assay needs to be simplified for use in resource-limited settings without fluorescent readers.

Solution: The core optimized one-pot chemistry is often directly compatible with lateral flow assay (LFA) formats. The ActCRISPR-TB assay demonstrated that transitioning from a fluorescent readout to an LFA format resulted in no loss of analytical or diagnostic sensitivity. This allows for visual detection of results using self-collected samples like tongue swabs, making it suitable for decentralized testing [14] [3]. The TRACE assay was also designed to meet ASSURED criteria (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable), which is a key benchmark for point-of-care tests [15].

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Identifying gRNAs with Favorable Asymmetric Cleavage Activity

This protocol is based on the development of the ActCRISPR-TB assay [14] [3].

- Tile the Target Amplicon: Identify a series of candidate gRNA sequences that tile across your target amplicon sequence (e.g., within the IS6110 element for TB).

- Include Non-Canonical PAMs: deliberately include candidates that bind to sequences with non-canonical PAM sites (not TTTV for Cas12a).

- Analyze Secondary Structures: Use software to predict secondary structures of candidate gRNAs and select those with stable configurations.

- Test Cis- and Trans-Cleavage Activities:

- Incubate each Cas RNP (with its unique gRNA) with a dsDNA substrate (the target).

- Use gel electrophoresis or a similar method to monitor the depletion of the dsDNA substrate over time. This measures cis-cleavage activity.

- In a parallel reaction, include a quenched ssDNA reporter. Monitor the fluorescence increase over time to measure trans-cleavage activity.

- Normalize and Compare: Normalize the cis- and trans-cleavage activities of each gRNA to a canonical gRNA (e.g., gRNA-0). Select gRNAs that exhibit low normalized cis-cleavage activity but high normalized trans-cleavage activity (e.g., gRNA-4, gRNA-5).

- Validate in One-Pot Format: Test the top-performing gRNAs individually in a one-pot RPA-CRISPR reaction to confirm improved reaction kinetics.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Thermally Regulated Asynchronous (TRACE) Assay

This protocol is adapted from the TRACE assay for MPXV detection [15].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a one-pot master mix containing:

- RPA reagents (primers, enzymes).

- Cas12b protein and its specific gRNA.

- A single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) blocker complementary to the gRNA spacer.

- A fluorescent or lateral-flow-compatible poly-T ssDNA reporter.

- The template DNA.

- Thermal Cycling:

- Stage 1 - Amplification: Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 10 minutes. During this phase, RPA amplification proceeds efficiently. The ssRNA blocker binds to the gRNA, significantly inhibiting Cas12b cis-cleavage activity and preventing amplicon degradation.

- Stage 2 - Detection: Immediately transfer the reaction to 60°C for 30 minutes. The higher temperature causes the ssRNA blocker to dissociate from the gRNA, activating the Cas12b RNP complex. The amplified target is now detected via trans-cleavage of the reporter.

- Readout: Measure fluorescence at the endpoint of Stage 2 or apply the reaction to a lateral flow strip for visual interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Optimization

The following table summarizes key reagents and their optimized roles based on the cited research.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for One-Pot Assay Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Rationale | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Canonical gRNAs | Guide RNAs targeting sequences with suboptimal PAMs to reduce cis-cleavage of the amplicon while preserving trans-cleavage for signal generation. | gRNA-5 for IS6110 target, which showed optimal asymmetric activity [14] [3]. |

| Multi-gRNA Cocktails | Using multiple gRNAs targeting different sites on the same amplicon to enhance signal and lower the limit of detection. | A combination of gRNA-2, gRNA-3, and gRNA-5 improved LoD to 5 copies/μL [14] [3]. |

| ssRNA Blockers | Short RNA strands that temporarily inhibit Cas RNP activity during the amplification phase by binding to the gRNA, preventing amplicon degradation. | ssRNA 1-S14 used in the TRACE assay to block Cas12b during the 37°C RPA phase [15]. |

| Cas12b Protein | A Cas protein with a higher temperature optimum (up to 60°C), enabling thermal separation of RPA (37°C) and CRISPR detection (60°C). | Used in the TRACE assay for MPXV to achieve an LoD of 2.5 copies/test [15]. |

| Magnesium (Mg²⁺) | A critical co-factor whose concentration must be optimized; increases can reduce assay signal and background. | An optimal concentration of 16.8 nM was used in the ActCRISPR-TB assay [14] [3]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Strategies

Diagram 1: Core Challenge in One-Pot Assays - Competitive Cleavage

Diagram 2: Multi-gRNA Strategy for Enhanced Sensitivity

Diagram 3: Thermally Programmed Workflow (TRACE Assay)

In the field of molecular diagnostics, particularly in sensitive pathogen detection, two metrics are fundamental for evaluating assay performance: the Limit of Detection (LoD) and Variant Allele Frequency (VAF). The LoD defines the lowest quantity of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from its absence, while the VAF measures the proportion of sequencing reads that carry a specific mutation. Understanding and optimizing these parameters is crucial for developing assays that can detect low-abundance pathogens and their genetic variations, which is a core focus of research aimed at improving diagnostic sensitivity for diseases like tuberculosis. This guide provides a technical framework for troubleshooting common issues related to these key metrics.

Limit of Detection (LoD): Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the Limit of Detection (LoD) and how is it statistically defined?

The Limit of Detection (LoD) is the lowest concentration or quantity of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from a blank sample (one containing no analyte) with a stated confidence level [17] [18]. It is not a fixed value but a statistical concept that balances the risks of false positives and false negatives [17].

- Key Statistical Definitions:

- Limit of Blank (LoB): The highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample are tested. It is calculated as

LoB = mean_blank + 1.645(SD_blank), which establishes a threshold where no more than 5% of blank measurements will exceed it (false positive rate of 5%) [19]. - Limit of Detection (LoD): The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from the LoB. It is calculated using both the LoB and a low-concentration sample:

LoD = LoB + 1.645(SD_low concentration sample)[19]. This formula ensures that a sample at the LoD will be incorrectly classified as a blank less than 5% of the time (false negative rate of 5%) [17] [19].

- Limit of Blank (LoB): The highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample are tested. It is calculated as

The following diagram illustrates the statistical relationship and calculation basis for LoB and LoD.

What is the difference between LoD and Limit of Quantitation (LoQ)?

The Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) is the lowest concentration at which an analyte can not only be reliably detected but also measured with acceptable precision and accuracy [18] [19]. While the LoD is about confirming the presence of an analyte, the LoQ is about reliably measuring its amount. The LoQ is always at a concentration equal to or higher than the LoD [19].

Table: Key Differences between LoB, LoD, and LoQ

| Parameter | Definition | Sample Type Used | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LoB) | Highest apparent concentration expected from a blank sample. | Sample containing no analyte. | Establish the threshold for false positives. |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | Lowest concentration reliably distinguished from the LoB. | Blank sample and sample with low analyte concentration. | Define the lowest concentration for reliable detection. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) | Lowest concentration measured with acceptable precision and accuracy. | Sample with analyte concentration at or above the LoD. | Define the lowest concentration for reliable measurement. |

Variant Allele Frequency (VAF): A Guide for Molecular Pathology

What is Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) and how is it calculated?

In molecular pathology, the Variant Allele Frequency (VAF), also known as variant allele fraction, is the proportion of sequencing reads that carry a specific mutation or variant at a particular genomic location [20]. It is calculated as:

VAF = (Number of mutated sequencing reads) / (Total number of sequencing reads at that locus) [20]

For example, if 6 out of 50 sequencing reads at a specific genomic position show a mutation, the VAF is 12% [20].

How is VAF used to interpret genetic variants?

The VAF is a critical metric for inferring the origin and biological significance of a genetic variant, especially in the context of cancer and liquid biopsies.

- Germline Variants: Heterozygous germline variants are expected to have a VAF of approximately 50%, while homozygous variants have a VAF close to 100% [20].

- Somatic Variants and Mosaicism: VAFs less than 50% but above the assay's detection limit can indicate mosaicism (where a mutation occurs after fertilization and is not present in all cells) or a somatic mutation in a mixed cell population [20].

- Liquid Biopsies and Tumor Heterogeneity: In liquid biopsies, cell-free tumor DNA (ctDNA) is a small fraction of the total cell-free DNA. Consequently, VAFs for tumor-derived variants can be very low (e.g., down to 0.1%), reflecting the tumor's genetic heterogeneity and burden [20]. At these low levels, distinguishing true variants from sequencing errors becomes a major challenge, directly related to the assay's LoD [20].

The diagram below shows how VAF helps infer the origin of a genetic variant.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: Our assay's LoD is higher than desired. What are the main factors that influence LoD and how can we improve it?

A high LoD is often driven by excessive background noise or suboptimal signal generation. Key factors and improvement strategies include:

- Factor 1: Assay Chemistry and Design. The fundamental biochemical reactions can be optimized to favor signal detection.

- Solution: In CRISPR-based assays, using guide RNAs (gRNAs) that favor trans-cleavage activity (which generates the detectable signal) over cis-cleavage activity (which degrades the target amplicon) can significantly improve LoD. One study achieved a 20-fold lower LoD (5 copies/μL) by selecting such gRNAs [3].

- Factor 2: Signal-to-Noise Ratio. A low signal relative to background noise obscures detection.

- Solution: In chromatography, the LoD is often defined as a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 3:1 [17]. Ensure your detection instrument is optimally configured and consider methods to reduce background noise, such as optimizing wash steps or using different reporters.

- Factor 3: Sample Matrix Effects. The sample itself can interfere with the assay.

- Solution: Use a sample for LoD determination that is commutable with real patient specimens to account for matrix effects [19]. Proper sample preparation and purification are critical.

- Factor 4: Reagent Quality and Concentration. Suboptimal reagent conditions can limit reaction efficiency.

- Solution: Systematically optimize concentrations of key reagents like primers, magnesium, and enzymes. For example, in the ActCRISPR-TB assay, optimizing primer and RNP concentrations was a key step in maximizing signal and kinetics [3].

FAQ: We are detecting low VAF variants, but are concerned they might be artifacts. How can we validate them?

Distinguishing true low-VAF variants from technical artifacts is a major challenge in next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Strategy 1: Establish a VAF Cutoff. Set a conservative VAF threshold based on your assay's validated performance. One study of medical exome sequencing found that all clinically relevant single-nucleotide variants had a VAF between 0.33 and 0.63, while 82% of technical artifacts had a VAF below 0.33. Implementing a cutoff of 0.30 for manual review reduced curation time by 20% without missing real variants [21].

- Strategy 2: Use Ultrasensitive NGS Methods. Standard NGS has a high error rate (~0.5% per base), making it unreliable for VAFs below 1% [22]. Employ specialized methods that generate consensus sequences from multiple reads of the original DNA molecule. These include:

- Strategy 3: Independent Validation. Confirm findings using an orthogonal method with a different detection chemistry (e.g., digital PCR) to rule out method-specific artifacts.

FAQ: How do LoD and VAF relate to each other in the context of pathogen detection?

LoD and VAF are interconnected concepts when detecting low levels of pathogen DNA, especially in a background of host DNA.

- The Relationship: The LoD of your assay defines the minimum number of pathogen DNA molecules required for a positive detection. The VAF in this context is the proportion of all DNA molecules (host + pathogen) that are derived from the pathogen. A positive detection requires that the pathogen DNA concentration is above the assay's LoD, which typically means the VAF must be above a certain threshold.

- Practical Implication: In a sample with a high amount of host DNA, the VAF of a pathogen sequence will be very low. To detect it, your assay must have a sufficiently sensitive LoD to find the absolute number of pathogen molecules within that large pool. For example, a CRISPR-TB assay with an LoD of 5 copies/μL was able to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis in patient samples where the pathogen DNA was present at a very low frequency [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their functions in developing sensitive detection assays, as exemplified by the search results.

Table: Key Reagents for Sensitive Pathogen Detection Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Assay | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Cas12a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | CRISPR-associated protein complex that binds target DNA and cleaves a reporter molecule upon recognition. | Core component of the ActCRISPR-TB assay for specific Mtb DNA detection [3]. |

| Asymmetric gRNAs | Guide RNAs engineered to favor trans-cleavage activity over cis-cleavage, improving signal amplification and LoD. | Use of gRNA-5 in ActCRISPR-TB to reduce amplicon degradation and enhance kinetics [3]. |

| Multi-gRNA Cocktails | Using multiple distinct gRNAs targeting the same amplicon to increase signal intensity and improve LoD. | Combining gRNA-2, -3, and -5 in ActCRISPR-TB to achieve an LoD of 5 copies/μL [3]. |

| Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) Reagents | Enzymes and buffers for isothermal nucleic acid amplification, enabling rapid target pre-amplification. | Used for target amplification in the one-pot ActCRISPR-TB assay [3]. |

| Hybrid Capture Probes | Target-specific oligonucleotide probes used to enrich pathogen DNA from a complex sample prior to NGS. | Used in the RP-MT-Capture NGS assay to enrich over 300 respiratory pathogen targets, improving sensitivity [23]. |

| ssDNA Fluorescent Reporter | A single-stranded DNA molecule coupled to a fluorophore/quencher pair; cleavage by Cas12a generates a fluorescent signal. | Reporter molecule used for real-time detection in the CRISPR-based assay [3]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Estimating LoD for a Chromatographic Method

The following protocol, based on established guidelines, provides a robust method for determining the LoD [17] [19].

Preparation:

- Obtain a test sample with a low concentration of the analyte, close to the expected LoD. Ideally, this should be in a real sample matrix.

- Prepare a blank sample (containing no analyte).

Analysis:

- Analyze a minimum of 10 (ideally 20 for verification, 60 for establishment) replicate portions of the blank sample, following the complete analytical procedure.

- Analyze a minimum of 10 (ideally 20 for verification, 60 for establishment) replicate portions of the low-concentration test sample.

Data Conversion:

- Convert the raw instrument signals (e.g., peak height, area) to concentration values using a calibration curve.

Calculation:

- For the blank measurements, calculate the mean (

mean_blank) and standard deviation (SD_blank). - Calculate the Limit of Blank (LoB) as:

LoB = mean_blank + 1.645(SD_blank). - For the low-concentration sample measurements, calculate the standard deviation (

SD_low). - Calculate the Limit of Detection (LoD) as:

LoD = LoB + 1.645(SD_low).

- For the blank measurements, calculate the mean (

Verification (as per EP17 guidelines):

- Analyze several samples with a concentration at the calculated LoD. If more than 5% of the results fall below the LoB, the LoD estimate is too low and should be re-estimated at a slightly higher concentration [19].

Cutting-Edge Workflows: From CRISPR Engineering to Synthetic Biology

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using a multi-guide RNA strategy in Cas12a assays? Using multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) that target distinct sites on the same pathogen's DNA significantly enhances the signal and sensitivity of the assay. This approach increases the chances of Cas12a activation and amplifies the trans-cleavage activity, leading to a stronger detection signal, which is crucial for identifying low-abundance pathogens [3].

FAQ 2: My one-pot Cas12a assay has low sensitivity. Could my gRNA design be the issue? Yes. Traditional gRNAs with strong cis-cleavage activity (cutting the target amplicon) can compete with the trans-cleavage activity (cutting the reporter) that generates your signal. Using gRNAs engineered to have asymmetric cleavage activity—favoring trans-cleavage over cis-cleavage—can prevent amplicon degradation, allowing for greater target accumulation and a stronger signal in one-pot assays [3].

FAQ 3: How do I select gRNAs for a multi-guide RNA assay? Not all gRNA combinations are effective. It is essential to tile the target sequence and empirically test the cis- and trans-cleavage activities of individual gRNA candidates [3]. The table below summarizes performance data for different gRNAs targeting the M. tuberculosis IS6110 element, which can serve as a reference for selection criteria.

Table: Performance Characteristics of Example gRNAs for Cas12a Assays

| gRNA Name | PAM Type | Relative Cis-Cleavage Activity | Relative Trans-Cleavage Activity | Suitability for One-Pot Assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gRNA-0 | Canonical (TTTV) | Very Strong | Very Strong (100%) | Low (high amplicon degradation) |

| gRNA-2 | Non-canonical | Strong | Very Strong (comparable to gRNA-0) | Moderate |

| gRNA-5 | Non-canonical | Weaker than gRNA-0 | Very Strong (comparable to gRNA-0) | High |

| gRNA-4 | Non-canonical | Weak | Moderate (42% of gRNA-0) | High |

| gRNA-1 | Non-canonical | Weak | Low (12% of gRNA-0) | Low |

Source: Adapted from Nature Communications (2025) 16:8257 [3].

FAQ 4: Why are the relative ratios of gRNAs important in a multi-guide setup? The ratio of gRNAs in the reaction mixture is critical because gRNAs with strong cis-cleavage activity can dominate and degrade the amplicon if present in high concentrations, thereby reducing sensitivity. For example, a mixture favoring the asymmetric gRNA-5 over the strong cis-cleaving gRNA-2 (e.g., a 30:10 ratio) enhanced assay kinetics, while a ratio favoring gRNA-2 (10:30) markedly attenuated the signal [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Multi-guide RNA Cas12a Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background noise or false positives | Non-specific activation of Cas12a; gRNA sequence overlap with primers. | Check all gRNA sequences for homology with primer sequences. Exclude gRNAs with any overlap (e.g., >10 nt) with primers [3]. |

| Low signal or false negatives in one-pot assay | Competitive cis-cleavage of amplicon depletes the target; suboptimal reaction conditions. | Use gRNAs with asymmetric cleavage activity (high trans-, low cis-). Systematically optimize Mg2+ concentration, primer concentration, and RNP complex concentration [3]. |

| Poor limit of detection (LoD) | Insufficient signal amplification from a single gRNA. | Implement a multi-gRNA strategy. A combination of gRNA-2, -3, and -5 was shown to achieve a LoD of 5 copies/μL, a 20-fold improvement over a single canonical gRNA [3]. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Unstable crRNA components; suboptimal reassembly kinetics in split systems. | For advanced designs using split crRNA technology, optimize fragment lengths, hybridization stability, and sequence complementarity to improve reassembly efficiency [24]. |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a Multi-guide RNA Cas12a Assay

The following protocol is adapted from the "ActCRISPR-TB" assay for sensitive detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [3].

1. gRNA Design and Selection

- Target Identification: Identify a unique, multi-copy sequence element specific to the target pathogen (e.g., IS6110 for Mtb).

- gRNA Tiling: Tile the target sequence to design several gRNA candidates, including those with non-canonical Protospacer Adjacent Motifs (PAMs).

- In vitro Screening: Express and purify each gRNA candidate. Test them individually in a cleavage assay to quantify their:

- Cis-cleavage activity: Measure the depletion of a dsDNA substrate.

- Trans-cleavage activity: Measure the cleavage of a fluorescent ssDNA reporter.

- Selection: Prioritize gRNAs that exhibit high trans-cleavage activity but low cis-cleavage activity (asymmetric cleavage).

2. Assay Optimization and Validation

- Reaction Setup: Develop a one-pot reaction that integrates recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) and CRISPR detection in a single tube.

- Parameter Optimization:

- Primer Concentration: Test a range (e.g., 100-500 nM).

- Mg2+ Concentration: A critical co-factor; test a range (e.g., 12-20 nM).

- RNP Concentration: Test Cas12a-gRNA complex concentrations (e.g., 20-60 nM).

- Multi-guide Formulation: Combine the top-performing asymmetric gRNAs (e.g., gRNA-5, gRNA-2, gRNA-3) at optimized ratios. Keep the total gRNA concentration constant while varying individual ratios.

- Performance Assessment:

- Limit of Detection (LoD): Determine the lowest copy number of target DNA that can be reliably detected.

- Specificity: Test against a panel of non-target pathogens to confirm specificity.

- Kinetics: Establish the time-to-signal for positive samples.

Visualizing the Multi-guide RNA Cas12a Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the streamlined workflow for a one-pot assay using multiple gRNAs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for Multi-guide RNA Cas12a Pathogen Detection

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric gRNAs | Guide RNAs engineered for high trans-cleavage and low cis-cleavage activity to maximize signal in one-pot assays. | gRNA-5, gRNA-4 from the IS6110 target [3]. |

| Cas12a Nuclease | The effector enzyme that, upon guided recognition of target DNA, cleaves the target and exhibits collateral trans-cleavage. | Can be sourced from various suppliers; LbCas12a and AsCas12a are common variants. |

| Isothermal Amplification Mix | Enables nucleic acid amplification at a constant temperature to boost target copy number before detection. | Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) or LAMP kits [3] [25]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter | A single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide labeled with a fluorophore and quencher; cleavage generates a fluorescent signal. | Often an ssDNA oligo labeled with FAM (fluorophore) and BHQ (quencher) [25]. |

| gRNA Design Tools | Computational tools to design gRNA sequences with high on-target and low off-target potential. | Synthego CRISPR Design Tool, Benchling CRISPR Design Tool [26]. |

| Split Technology Components | For advanced assays: Split crRNA or activator fragments that reassemble only in the presence of the target, enhancing specificity. | Truncated crRNA (tcrRNA) and complementary activator strands [24]. |

A significant challenge in molecular diagnostics, particularly for diseases like Tuberculosis (TB), is achieving clinically relevant sensitivity with streamlined, point-of-care compatible assays. Conventional CRISPR assays often lack the requisite sensitivity for direct clinical utility, primarily due to complex workflows and competitive reactions that limit target accumulation [3] [14]. This case study examines the development of ActCRISPR-TB, an asymmetric cis/trans CRISPR cleavage assay that achieves a remarkable sensitivity of 5 copies/μL within 60 minutes [3]. We will explore the technical foundations of this assay, provide detailed experimental protocols, and establish a technical support framework to assist researchers in implementing and troubleshooting this advanced diagnostic platform.

Core Technology: Principles of the Asymmetric Cis/Trans Cleavage Assay

The Fundamental Problem: Competitive Cis-Cleavage in One-Pot Assays

Traditional one-pot CRISPR assays combine target amplification (e.g., via Recombinase Polymerase Amplification - RPA) and detection in a single reaction vessel. However, they face a critical limitation: the Cas enzyme's cis-cleavage activity (cutting of the target amplicon) competes with the amplification process, reducing overall amplification efficiency and limiting sensitivity [3] [27]. This competition between amplicon production and degradation creates a fundamental sensitivity barrier in one-pot formats.

The ActCRISPR-TB Solution: Engineering Trans-Cleavage Preference

ActCRISPR-TB addresses this limitation through a novel guide RNA (gRNA) engineering strategy that favors trans-cleavage (collateral cleavage of reporter molecules) over cis-cleavage [3]. The key innovation involves using multiple gRNAs targeting sequences with non-consensus protospacer-adjacent motifs (PAMs) that demonstrate asymmetric cleavage activity—maintaining robust trans-cleavage for signal generation while minimizing cis-cleavage that degrades the amplicon target [3]. This balance allows for greater accumulation of amplification products while maintaining strong signal output.

Figure 1: ActCRISPR-TB Workflow Logic - The core innovation utilizes gRNAs with non-canonical PAM binding sites to reduce cis-cleavage (amplicon degradation) while maintaining strong trans-cleavage activity for signal generation, creating a positive feedback loop that enhances sensitivity.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

gRNA Screening and Characterization Protocol

Objective: Identify gRNA candidates with favorable trans- versus cis-cleavage activity ratios.

Procedure:

- Tile the target sequence: Design gRNAs tiling the IS6110 amplicon sequence, focusing on sites with non-canonical PAM sequences [3].

- Analyze secondary structures: Use computational tools (e.g., NUPACK) to evaluate gRNA secondary structure stability [3].

- Measure cleavage activities:

- Calculate normalized activity ratios: Rank gRNAs based on their trans-/cis-cleavage activity ratios [3].

- Exclude non-specific binders: Eliminate gRNAs with sequence overlap to RPA primers to prevent template-independent signal [3].

Critical Note: gRNA-6 was excluded from final development due to a 10-nucleotide sequence overlap with the RPA forward primer, which generated template-independent signal [3].

Optimized One-Pot ActCRISPR-TB Reaction Setup

Reaction Components:

- Primers: 500 nM each (IS6110-targeting RPA primers)

- Magnesium acetate: 16.8 nM

- RNP complex: 40 nM (Cas12a with gRNA-2, -3, and -5 mixture)

- ssDNA reporter: 600 nM (FQ-labeled or biotin/FAM-labeled for lateral flow)

- Template DNA: 5 μL in 50 μL total reaction volume

- RPA basic kit components (as per manufacturer's instructions)

Thermal Conditions:

- Amplification & Detection: 36-40°C for 45-60 minutes [3]

- Reaction Vessel: Single tube with no intermediate steps

gRNA Combination Optimization: The optimal multi-guide RNA combination was determined to be gRNA-2, gRNA-3, and gRNA-5 at specific ratios that maximize signal while minimizing competitive cis-cleavage [3].

Clinical Sample Processing Protocol

Sample Types Validated:

- Respiratory specimens (sputum)

- Pediatric stool samples

- Adult cerebral spinal fluid

- Tongue swabs [3] [28]

DNA Extraction Method:

- Process clinical samples using standard DNA extraction kits

- Elute DNA in nuclease-free water or TE buffer

- Use 5 μL of extracted DNA as template for the ActCRISPR-TB reaction

Readout Methods:

- Real-time fluorescence: Monitor every minute for 60 minutes

- Endpoint detection: Lateral flow strip readout after 45-60 minutes [3]

Performance Data & Validation

Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

Table 1: Analytical Performance of ActCRISPR-TB Across Sample Types

| Parameter | Performance | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection | 5 copies/μL | Synthetic targets [3] |

| Time to Positive | 15 minutes for high bacterial load samples | Clinical sputum samples [3] |

| Assay Specificity | 100% for MTB complex species | Testing against non-tuberculous mycobacteria [3] |

| Optimal Read Time | 45 minutes | Balances speed and sensitivity [3] |

Clinical Validation Performance

Table 2: Clinical Performance of ActCRISPR-TB in 603 Clinical Samples

| Sample Type | Sensitivity | Specificity | Comparative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Respiratory | 93% | Not specified | Comparable to reference molecular diagnostics [3] |

| Pediatric Stool | 83% | Not specified | Superior to sputum-based references [3] |

| Adult CSF | 93% | Not specified | Detected 64% of clinically diagnosed TB meningitis [3] |

| Tongue Swabs | 74% | 100% | Superior to most sensitive reference test (56%) [3] [28] |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ActCRISPR-TB Implementation

| Reagent | Function | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas12a Protein | CRISPR effector enzyme; performs target recognition and cleavage | Use purified LbCas12a; concentration optimized at 40 nM [3] |

| gRNA-2, -3, -5组合 | Guide RNAs targeting IS6110 element; determine cleavage specificity | Critical ratio optimization required; total gRNA concentration 40 nM [3] |

| IS6110 RPA Primers | Amplify target sequence isothermally | 500 nM each primer; asymmetric design may enhance performance [3] |

| ssDNA Reporter | Signal generation via trans-cleavage | 600 nM FQ-labeled or lateral flow-compatible (biotin/FAM) [3] |

| Magnesium Acetate | Cofactor for enzymatic reactions | Critical concentration: 16.8 nM; excess reduces signal [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our ActCRISPR-TB assay shows high background signal even without template. What could be causing this?

A: Background signal typically results from:

- gRNA-primer overlap: Check for sequence complementarity between your gRNA and RPA primers (as encountered with gRNA-6) [3].

- Contaminated reagents: Prepare fresh aliquots of all reagents, particularly the RPA master mix.

- Suboptimal magnesium concentration: Titrate magnesium acetate between 15-20 nM; excess magnesium increases background [3].

- RNP complex precipitation: Ensure Cas12a-gRNA complexes are properly formed and not aggregated.

Q2: We're not achieving the published 5 copies/μL sensitivity. What optimization steps should we take?

A: Sensitivity issues commonly stem from:

- Suboptimal gRNA ratios: Systematically test gRNA-2, -3, and -5 combinations at different ratios while maintaining total gRNA at 40 nM [3].

- Reaction temperature: Ensure consistent temperature between 36-40°C throughout the reaction [3].

- Template quality: Verify DNA extraction efficiency and avoid inhibitors.

- Reaction time extension: Increase incubation time to 60 minutes for very low target concentrations [3].

Q3: How does ActCRISPR-TB maintain sensitivity while using non-canonical PAM sites that typically reduce Cas12a activity?

A: The key innovation is the discovery that trans- and cis-cleavage activities are functionally independent [3]. While non-canonical PAMs typically reduce both activities, specific gRNAs (particularly gRNA-5) demonstrate disproportionate preservation of trans-cleavage while minimizing cis-cleavage. This asymmetric activity profile reduces amplicon degradation while maintaining signal generation capacity [3].

Q4: Can ActCRISPR-TB be adapted for detection of other pathogens?

A: Yes, the core principle of engineering gRNAs that favor trans- versus cis-cleavage is broadly applicable. The researchers note potential for expansion to other pathogens, including emerging threats like COVID-19 and monkeypox [28]. Successful adaptation requires:

- Identification of suitable multi-copy target sequences

- Systematic gRNA tiling and characterization

- Optimization of the guide RNA combinations for the new target

Q5: What are the limitations of using tongue swabs instead of sputum for TB detection?

A: While tongue swabs offer significant practical advantages for screening, particularly in resource-limited settings, they present certain challenges:

- Lower bacterial load: M. tuberculosis DNA levels are typically lower on tongue swabs [28].

- Sampling variability: DNA recovery fluctuates with sampling technique, disease burden, and even daily activities affecting "respiratory material transfer to and depletion from the oral cavity" [28].

- Reduced sensitivity: The assay detected 74% of TB cases versus 93% with respiratory samples [3] [28].

Figure 2: ActCRISPR-TB Troubleshooting Decision Tree - A systematic approach to resolving common experimental challenges when implementing the assay.

ActCRISPR-TB represents a significant advancement in CRISPR diagnostics by fundamentally addressing the cis-/trans-cleavage competition that has limited one-pot assay sensitivity. Through strategic gRNA engineering that creates an asymmetric cleavage profile favoring trans-cleavage, the assay achieves detection limits as low as 5 copies/μL while maintaining a streamlined, single-reaction format [3]. This approach, validated across diverse clinical specimens, demonstrates that careful balancing of the competing reactions in one-pot assays can overcome traditional sensitivity barriers. The technical framework established by ActCRISPR-TB provides a blueprint for developing next-generation molecular diagnostics that combine high sensitivity with practical implementation requirements, particularly valuable for resource-limited settings where TB burden is highest.

Conventional enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) face a significant sensitivity gap compared to nucleic acid-based tests, typically detecting biomarkers in the pico- to nanomolar range while molecular techniques like PCR achieve atto- to femtomolar sensitivity [2] [29]. This limitation is particularly critical for pathogen detection where early diagnosis requires identifying low-abundance proteins. Cell-free synthetic biology has emerged as a transformative approach to bridge this sensitivity gap by integrating programmable nucleic acid and protein synthesis systems into traditional immunoassay workflows [2] [1].

Novel platforms such as expression immunoassays and CRISPR-linked immunoassays (CLISA) leverage cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) to create highly sensitive and modular diagnostic systems [2]. These approaches enable signal amplification through synthetic biology mechanisms, potentially enhancing detection sensitivity by hundreds-fold while maintaining the specificity and accessibility of traditional ELISA [1]. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance for researchers implementing these advanced protein detection methodologies within pathogen detection assays.

★ Key Concepts and FAQs

What are expression immunoassays and how do they enhance detection sensitivity? Expression immunoassays integrate cell-free protein synthesis directly into immunoassay workflows. In these systems, detection antibodies are labeled with DNA sequences encoding reporter proteins or the target biomarkers themselves [1]. When these antibody-DNA conjugates bind to their targets, the associated DNA serves as a template for in situ protein synthesis using CFPS systems, effectively amplifying the detection signal through continuous production of reporter molecules rather than relying on a finite number of enzyme labels [2] [1].

How does CLISA differ from traditional ELISA? CLISA (CRISPR-linked immunoassay) incorporates CRISPR-based nucleic acid detection systems into immunoassay formats. While traditional ELISA uses enzyme-conjugated antibodies for colorimetric detection, CLISA leverages the programmability and amplification capabilities of CRISPR systems to detect DNA tags attached to detection antibodies [2]. This approach combines the specificity of antibody-antigen interactions with the powerful signal amplification of CRISPR systems, potentially achieving detection sensitivities comparable to nucleic acid tests [2].

What are the primary advantages of integrating cell-free systems with immunoassays?

- Enhanced Sensitivity: Cell-free systems enable signal amplification through continuous protein synthesis or nucleic acid amplification, potentially improving detection limits by hundreds-fold [1]

- Modularity: DNA-programmable systems allow rapid adaptation to detect different biomarkers by simply changing the DNA template [2] [1]

- Flexibility: CFPS operates without cell viability constraints, enabling optimization of reaction conditions specific to each assay [30]

- Accessibility: Lyophilized cell-free systems can be distributed and used in resource-limited settings with minimal equipment [31]

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Expression Immunoassay Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Detection Sensitivity

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High background signal | Non-specific binding of detection antibody-DNA conjugates | Optimize blocking conditions using BSA, casein, or synthetic polymers like PEG; Implement nonfouling surface modifications [29] |

| Weak or no signal | Inefficient cell-free protein synthesis; Suboptimal DNA template design | Verify DNA template purity and sequence; Ensure proper T7 promoter and terminator sequences; Add RNase inhibitor to reactions [32] [33] |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Variable washing efficiency; Unequal reagent distribution | Implement microfluidic systems for consistent mixing and washing; Use automated liquid handling systems where available [29] |

| Reduced protein yield in CFPS | Resource depletion in cell-free reactions; Suboptimal conditions | Utilize multiple feeding steps with smaller volumes of feed buffer (e.g., every 45 minutes); Add mild detergents (up to 0.05% Triton-X-100) to improve yields [32] |

Table 2: Addressing Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No protein synthesis | Inactive kit components; Missing T7 RNA polymerase | Minimize freeze-thaw cycles of cell extract; Confirm addition of T7 RNA polymerase to reactions [32] [33] |

| Low protein yield | RNase contamination; Suboptimal DNA template design | Add RNase inhibitor; Verify DNA template contains proper UTR stem loop to stabilize mRNA; Optimize template amount (typically 250 ng for 50 μL reaction) [33] |

| Truncated protein products | Premature termination; Ribosome stalling at rare codons | Reduce incubation temperature to 25-30°C; Check for internal initiation sites; Consider codon optimization for eukaryotic proteins [32] [33] |

| Inactive synthesized proteins | Improper folding; Lack of essential cofactors | Add molecular chaperones to reactions; Include required cofactors in protein synthesis reaction; Extend incubation time at lower temperatures (16°C for up to 24 hours) [32] |

DNA Template Design and Preparation

How should I design DNA templates for expression immunoassays? Effective DNA template design is crucial for successful expression immunoassays. Ensure your template includes:

- Strong promoter sequences (typically T7) for efficient transcription [33]

- Optimal 5' untranslated regions (UTRs) to enhance translational efficiency [33]

- Stem-loop structures or T7 terminators to stabilize mRNA [33]

- Coding sequence for your reporter protein (fluorescent protein, enzyme, etc.)

- Avoidance of complex secondary structures near the translation initiation site [33]

What are the common DNA template preparation mistakes?

- Using DNA purified from agarose gels, which often contains translation inhibitors [32] [33]

- Residual ethanol, salts, or SDS from plasmid preparation protocols [32]

- RNase contamination from commercial mini-prep kits [33]

- Insufficient DNA concentration quantification due to RNA contamination [33]

Always repurify DNA using commercial cleanup kits and verify concentration and purity by both UV spectrophotometry (260/280 ratio ~1.8) and agarose gel electrophoresis [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Nucleic Acid-Templated Target Amplification (NATA)-ELISA

This protocol enables hundreds-fold sensitivity enhancement for protein detection by integrating target amplification into standard ELISA workflows [1].

Materials Required:

- Capture and detection antibodies specific to your target biomarker

- DNA template encoding your target biomarker or a universal surrogate protein (e.g., Streptococcal protein G with Avi-tag)

- Coupling reagents for antibody-DNA conjugation

- Cell-free protein synthesis system (E. coli extract-based or PURExpress)

- Standard ELISA plates and detection reagents

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Coat ELISA plates with capture antibodies using orientation strategies (Protein A/G, biotin-streptavidin) to enhance binding efficiency [29]

- Sample Incubation: Add samples containing target biomarker and incubate to allow antigen capture

- Detection Antibody Binding: Add DNA-conjugated detection antibodies and incubate

- Cell-Free Protein Synthesis: Add CFPS reaction mixture containing:

- Cell extract (E. coli, wheat germ, or rabbit reticulocyte-based)

- Energy regeneration system (ATP, GTP)

- Amino acids mixture

- RNA polymerase (typically T7)

- Nucleotides

- Signal Development: Incubate to allow synthesis of reporter proteins (2-4 hours at 30-37°C)

- Detection: Quantify synthesized reporters using appropriate methods (colorimetric, fluorescent, or luminescent)

Key Optimization Tips:

- Implement multiple feeding steps during CFPS to improve protein yields [32]

- Include RNase inhibitor to protect DNA templates and mRNA transcripts [33]

- For low-abundance targets, extend CFPS incubation time and reduce temperature to 25°C [32]

Protocol 2: CLISA Implementation

This protocol outlines CRISPR-enhanced immunoassay development for ultra-sensitive detection.

Materials Required:

- Antibody-DNA conjugates (detection antibodies linked to specific DNA sequences)

- CRISPR-Cas system (Cas12a, Cas13, or Cas9)

- Reporter nucleic acids (fluorescently quenched DNA or RNA probes)

- Cell-free transcription-translation system

- Standard immunoassay components

Procedure:

- Traditional Immunoassay Steps: Complete capture and detection antibody binding as in standard ELISA

- CRISPR Activation: Release or activate DNA templates bound via detection antibodies

- Nucleic Acid Amplification: Amplify activated DNA templates using PCR or isothermal amplification

- CRISPR Detection: Incubate amplified products with appropriate CRISPR system and reporter probes

- Signal Measurement: Detect cleavage of reporter probes via fluorescence or colorimetric changes

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli-based CFPS systems | Provides transcription/translation machinery for protein synthesis | Cost-effective; high protein yields; suitable for most reporter proteins [34] [35] |

| PURExpress In Vitro Protein Synthesis Kit | Reconstituted purified components for CFPS | Eliminates background E. coli activities; defined system for standardized results [34] |

| T7 RNA Polymerase | Drives transcription from T7 promoters | Essential for systems utilizing T7 promoters; typically used at 1-1.5 μL per 50 μL reaction [32] |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA components from degradation | Critical when using DNA prepared from commercial mini-prep kits [33] |

| MembraneMax Reagent | Enables membrane protein expression in CFPS | Essential for expressing membrane-bound targets; forms lipid bilayers for proper protein folding [32] |

| PURExpress Disulfide Bond Enhancer | Promotes proper disulfide bond formation | Improves activity of proteins requiring disulfide bonds; add 2 μL of each enhancer per 50 μL reaction [33] |

Workflow Visualization

Expression Immunoassay Workflow - This diagram illustrates the key steps in implementing expression immunoassays, highlighting the integration of traditional immunoassay steps with synthetic biology enhancement for superior sensitivity.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The integration of cell-free synthetic biology with immunoassays continues to evolve with emerging applications in pathogen detection. Recent developments include:

Multiplexed Detection Platforms: Leveraging cell-free systems to detect multiple pathogens simultaneously by encoding distinct reporter proteins for different targets [1]. This approach enables comprehensive pathogen screening from single samples.

Point-of-Care Adaptation: Utilizing lyophilized, shelf-stable cell-free systems that can be deployed in resource-limited settings [31] [36]. These systems maintain functionality for months at room temperature and can be activated by just adding water.

CRISPR-Enhanced Specificity: Combining the specificity of CRISPR systems with antibody-based detection to create dual-validation platforms that reduce false positives in pathogen identification [2].

As these technologies mature, researchers can expect increasingly sophisticated tools for sensitive protein detection that bridge the gap between immunoassays and molecular diagnostics, ultimately enhancing early pathogen detection capabilities in both clinical and field settings.

Technical Support Center

Core Mechanism and Principle FAQs

Q1: What is the fundamental principle that enables amplification-free CRISPR detection?

Amplification-free CRISPR diagnostics rely on the trans-cleavage activity of certain Cas proteins. Upon recognizing and binding to its specific target nucleic acid, the Cas protein becomes activated and unleishes non-specific, "collateral" cleavage of surrounding reporter molecules [37] [38]. For example, Cas12a targets DNA and trans-cleaves single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) reporters, while Cas13a targets RNA and trans-cleaves single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) reporters [37] [25]. This cleavage of reporter molecules generates a detectable signal (fluorescent, electrochemical, etc.), allowing for direct pathogen detection without the need for pre-amplification of the target sequence.

Q2: How do "cascade" systems enhance sensitivity without target amplification?

Cascade CRISPR systems improve sensitivity by linking the activities of multiple Cas proteins in a sequential manner, creating a signal amplification effect. One documented system for microRNA detection uses Cas13a and Cas12f in tandem [37] [39]. In this setup, the target miRNA first activates Cas13a. The trans-cleavage activity of Cas13a then produces a product that serves as the activator for a second Cas protein (e.g., Cas12f). This subsequent Cas protein then cleaves its own reporter, leading to a cascading signal boost. This multi-enzyme circuit can achieve femtomolar (fM) sensitivity and single-base resolution without any pre-amplification step [39].

Q3: What is the working principle behind digital droplet CRISPR platforms?

Digital droplet platforms work by partitioning a reaction mixture into thousands of nanoliter- or picoliter-sized reactors [37]. This micro-confinement effect significantly increases the local concentration of the target molecule within positive droplets. Platforms like SATORI (CRISPR-based amplification-free digital RNA detection) combine Cas13 detection with microchamber-array technologies [37]. Each droplet is analyzed individually, allowing for absolute quantification of the target nucleic acid at concentrations as low as 5 fM in just a few minutes, all without amplification [37].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q4: What should I do if my amplification-free assay shows no signal or a weak signal?

- Check Target Concentration: Verify that the target concentration meets or exceeds the limit of detection (LOD) for your specific Cas protein. The activation concentration can be around 100 pM for Cas12 and ~50 pM for Cas13 [37]. If your target is too dilute, consider alternative concentration methods or switching to a more sensitive platform like a digital droplet system.

- Optimize the Reporter System: The design of the reporter molecule is critical. Research indicates that using a stem-loop reporter (e.g., a 7nt stem-loop for Cas12a) can outperform traditional linear reporters, potentially offering a 10-fold increase in sensitivity [40]. Ensure the fluorophore and quencher pair on your reporter are compatible and that the reporter is present at an optimal concentration.

- Select the Right Cas Variant: Not all Cas enzymes are created equal. For Cas12a-based systems, the LbCas12a-Ultra variant has been identified as one of the most sensitive orthologs and can significantly boost detection capability [40].

- Verify crRNA Design: Ensure your crRNA is correctly designed and has stable secondary structures. Using multiple gRNAs targeting different sites on the same target amplicon has been shown to enhance signal production and improve overall assay sensitivity [3].

Q5: How can I address issues with specificity, such as false-positive signals?

- Refine crRNA Specificity: Meticulously design crRNAs to ensure high specificity for the target sequence. Use bioinformatic tools to check for potential off-target binding sites. The location of mismatches is important; those in the seed sequence (8–10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA) are more likely to inhibit cleavage [41].

- Include Rigorous Controls: Always run negative controls (samples without the target) to identify any background signal or non-specific trans-cleavage activity. Use cells transfected with irrelevant plasmids or mock-transfected cells as negative controls to distinguish background from specific cleavage [42].