Optimizing Cas9 Expression for Sustained Biofilm Disruption: Strategies for Next-Generation Antimicrobial Therapy

Biofilm-associated infections represent a major therapeutic challenge due to their high tolerance to conventional antibiotics.

Optimizing Cas9 Expression for Sustained Biofilm Disruption: Strategies for Next-Generation Antimicrobial Therapy

Abstract

Biofilm-associated infections represent a major therapeutic challenge due to their high tolerance to conventional antibiotics. This article explores the strategic optimization of Cas9 expression as a novel approach to achieving sustained inhibition of bacterial biofilms. We first establish the critical relationship between Cas9 dosage, persistence, and efficacy in disrupting biofilm integrity and resistance genes. The review then details advanced methodological approaches, including inducible systems and nanoparticle-mediated delivery, for precise temporal and spatial control of Cas9. Furthermore, we present comprehensive troubleshooting frameworks for overcoming common hurdles in editing efficiency and specificity. Finally, we outline rigorous validation protocols employing T7E1 assays, sequencing, and functional phenotyping to confirm successful biofilm disruption. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a roadmap for translating optimized CRISPR-Cas9 systems into effective clinical interventions against persistent biofilm-mediated infections.

The Biofilm Challenge and Cas9 Mechanism: Establishing the Rationale for Expression Optimization

Biofilm Architecture as a Physical and Physiological Barrier to Treatment

FAQs: Understanding Biofilm Architecture and Resistance

Q1: What are the key structural components of a biofilm that contribute to its resistance? Biofilms are microbial communities enclosed in a self-produced matrix of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS). This matrix is a complex biological barrier composed primarily of water (up to 97%), polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA (eDNA), and lipids [1] [2]. The EPS acts as a physical scaffold, trapping cells and other materials, and is the primary line of defense. It significantly impedes the penetration of antimicrobial agents and protects the embedded cells from the host's immune system and environmental stresses [3] [4] [1].

Q2: Beyond physical barrier, what physiological states do cells within a biofilm exhibit? The biofilm environment induces profound physiological heterogeneity. Key states include:

- Metabolic Gradients: Nutrients and oxygen diffuse poorly, creating gradients from the top to the bottom of the biofilm. This results in zones of rapidly dividing cells on the periphery and slow-growing or dormant "persister" cells in the interior core [5] [6]. Many antibiotics, such as β-lactams, are ineffective against dormant cells.

- Altered Gene Expression: Biofilm cells undergo a phenotypic shift, differentially regulating large suites of genes compared to their free-floating (planktonic) counterparts. This reprogramming enhances stress tolerance and matrix production [3] [7].

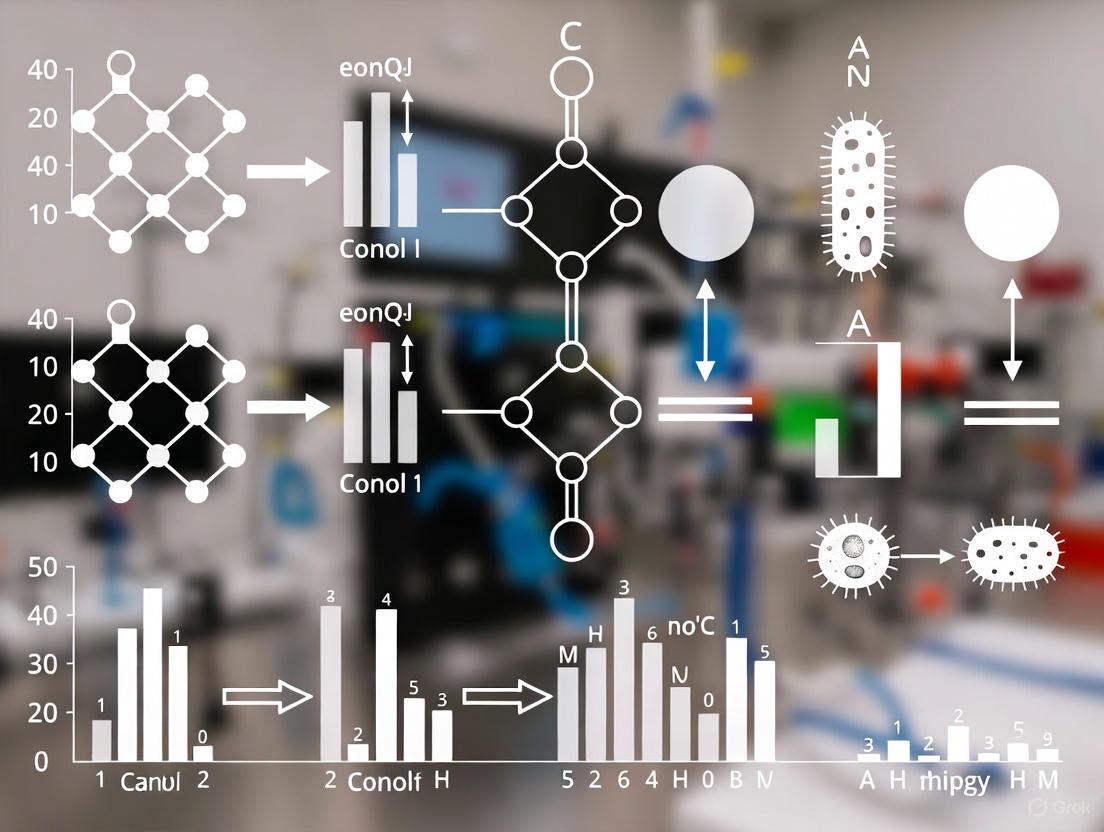

Q3: How does the biofilm lifecycle impact treatment strategies? The biofilm lifecycle is a dynamic process with distinct stages, each presenting different vulnerabilities [7] [4] [1]. The diagram below illustrates the key stages and the corresponding strategic focus for treatment.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent CRISPR-Cas9 Efficacy in Biofilm Eradication This is a common issue stemming from the dual physical and physiological barriers of the biofilm architecture.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Questions | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Delivery | Does your construct fail to penetrate the inner layers of the mature biofilm? | Utilize nanoparticle carriers (e.g., lipid-based, gold nanoparticles). Studies show liposomal Cas9 formulations can reduce P. aeruginosa biofilm by >90%, and gold NPs can enhance editing efficiency 3.5-fold by improving cellular uptake and protecting the payload [6]. |

| Targeting Non-Vulnerable Pathways | Are you targeting genes that are not critical for biofilm integrity or are redundant? | Use CRISPRi (interference) with dCas9 to repress genes for EPS core components (e.g., pel, psl polysaccharides in P. aeruginosa) or quorum-sensing regulators (e.g., lasI, rhlI) instead of lethal cleavage. This disrupts the community without selecting for escape mutants [5] [8]. |

| Ignoring Physiological Heterogeneity | Is your Cas9 expression active enough to target the dormant persister cells? | Optimize Cas9 expression with promoters that remain active under nutrient-limited or stress conditions. Combine CRISPR-Cas9 with a second antimicrobial agent delivered via the same nanoparticle to target both active and dormant populations synergistically [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Anti-Biofilm Strategies

Protocol 1: Quantifying Biofilm Architecture and Viability After Treatment This protocol assesses the physical disruption and biocidal efficacy of a CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutic.

Method:

- Biofilm Growth: Grow biofilms in a flow cell or on a peg lid to allow for 3D development. Standardize the growth medium, temperature, and incubation time.

- Treatment Application: Apply the CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutic (e.g., nanoparticle-encapsulated). Include controls: untreated biofilm, nanoparticle-only, and scrambled gRNA.

- Viability Staining & Imaging: Gently wash to remove non-adherent cells. Stain with a LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit (e.g., SYTO 9 and propidium iodide).

- Image Acquisition: Use Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) to capture Z-stacks of the biofilm.

- Image Analysis: Use software (e.g., ImageJ, COMSTAT) to quantify:

Protocol 2: Assessing CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery and Target Engagement This protocol evaluates the functional delivery and gene-editing efficiency within the biofilm.

Method:

- Construct Design: Clone your Cas9 (or dCas9 for CRISPRi) and sgRNA targeting a specific biofilm-related gene (e.g., a gene for EPS production) into a delivery vector (e.g., a plasmid for bacteriophage or nanoparticle delivery).

- Treatment & Incubation: Apply the construct to a mature biofilm and incubate for a defined period.

- RNA/DNA Extraction & Analysis:

- For DNA-targeting Cas9: Extract genomic DNA and perform T7 Endonuclease I assay or sequencing to detect indels at the target locus.

- For Gene Repression (CRISPRi): Extract total RNA, perform reverse transcription, and use quantitative PCR (qPCR) to measure the downregulation of the target mRNA.

- Functional Confirmation: Correlate genetic knockdown with a phenotypic assay, such as quantifying total carbohydrate content (e.g., with phenol-sulfuric acid method) to confirm reduced EPS production [5] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Investigating Biofilm Resistance and CRISPR-Cas9 Inhibition

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Cell Systems | Culturing biofilms under fluid shear stress, mimicking physiological/industrial conditions. Enables real-time, non-destructive imaging. | Essential for studying mature, architecturally complex biofilms with characteristic mushroom-like structures and water channels [3] [9]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid Kit (with dCas9) | For gene knockout (nuclease-active Cas9) or transcriptional repression (CRISPRi with dCas9) of specific biofilm genes. | Using inducible promoters allows for temporal control over Cas9 expression, which is critical for optimizing efficacy and minimizing toxicity [5] [8]. |

| Nanoparticle Carriers (e.g., Liposomal, Gold) | Enhancing the delivery of CRISPR components through the dense EPS matrix. Protects payload and improves cellular uptake. | Gold nanoparticles have been shown to increase CRISPR editing efficiency by up to 3.5-fold within biofilms compared to non-carrier systems [6]. |

| LIVE/DEAD BacLight Viability Kit | Differentiating between live (membrane-intact) and dead (membrane-compromised) cells in a biofilm via fluorescence microscopy. | A standard for quantifying the bactericidal effect of a treatment. Must be used with CLSM for accurate 3D quantification [1]. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM) | High-resolution, optical sectioning of intact biofilms to visualize 3D architecture, viability, and matrix components. | The primary tool for analyzing biofilm spatial structure and the distribution of different cell states and molecules after treatment [3] [6]. |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | A key structural component of the biofilm matrix; targeted for disruption. | Adding DNase I to treatment regimens can effectively weaken the biofilm structure and enhance the penetration of other antimicrobials [7] [1]. |

Optimizing Cas9 Expression for Sustained Inhibition: A Workflow

Achieving sustained biofilm inhibition requires careful optimization of CRISPR-Cas9 delivery and expression. The following workflow outlines a systematic approach for researchers.

Table: Key Parameters to Monitor for Cas9 Expression Optimization

| Parameter | Measurement Technique | Optimization Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 mRNA Levels | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Find the minimum expression level required for maximal target gene disruption to minimize resource burden on the delivery vehicle and potential cellular toxicity. |

| Target Gene Knockdown/Edition | RT-qPCR (for CRISPRi), Sequencing (for nuclease) | Achieve >70% reduction in target gene expression or high editing efficiency in the biofilm population. |

| Biofilm Biomass Reduction | Confocal Microscopy Analysis (e.g., COMSTAT) | Consistent, significant reduction (e.g., >50-90%) in total biomass in treated versus control biofilms [6]. |

| Penetration Depth | Fluorescently tagged Cas9/sgRNA + CLSM | Ensure the signal is detectable throughout the full thickness of the biofilm, not just the surface layers. |

CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanisms for Targeting Biofilm Integrity and Resistance Genes

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Gene Editing Efficiency in Biofilm-Associated Bacteria

Problem: CRISPR-Cas9 system shows low efficiency in disrupting biofilm-forming or resistance genes in bacterial populations.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Relevant Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient delivery into bacterial cells within the biofilm matrix. | Use nanoparticle carriers (e.g., gold or lipid nanoparticles) to enhance delivery. These can improve cellular uptake and protect CRISPR components from degradation [6]. | Liposomal Cas9 formulations reduced P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass by >90% in vitro [6]. |

| Poor guide RNA (gRNA) design targeting the chosen gene. | Carefully design crRNA target oligos to avoid homology with other genomic regions. Use bioinformatics tools to ensure specificity and minimize off-target effects [10]. | CRISPR–gold nanoparticle hybrids demonstrated a 3.5-fold increase in gene-editing efficiency [6]. |

| Low transfection efficiency in the specific bacterial strain. | Optimize transfection protocols. For difficult strains, consider using Lipofectamine 3000 or 2000 reagent and include antibiotic selection or FAC sorting to enrich for transfected cells [10]. | Successful CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in Acinetobacter baumannii was achieved using a plasmid system with apramycin selection [11]. |

| Target inaccessibility due to chromatin structure or protective biofilm matrix. | Design gRNAs targeting different regions of the gene. Use enzymes or agents that disrupt the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) to improve access [10] [4]. | The heterogeneous biofilm structure and EPS matrix can limit penetration of antimicrobial agents [6] [4]. |

Absence of Cleavage Bands in Validation Assays

Problem: No cleavage band is visible after performing a genomic cleavage detection assay (e.g., T7E1 assay) on transfected bacterial cultures.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Nucleases cannot access or cleave the target sequence. | Redesign the gRNA targeting strategy for a different nearby sequence [10]. |

| Genomic modification level is too low to detect. | Optimize the transfection protocol to increase efficiency. Use the GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit with its control template and primers to verify kit components and protocol [10]. |

| The denaturing and reannealing step in the assay was omitted. | Ensure all steps of the cleavage detection protocol are followed meticulously [10]. |

High Background or Non-Specific Cleavage

Problem: Gel analysis shows high background noise or non-specific cleavage bands, making results difficult to interpret.

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| PCR primers are not optimal for the specific target locus. | Redesign PCR primers to produce a distinct, clear banding pattern for cleaved vs. uncleaved products [10]. |

| Intricate mutations at the target site complicate the banding pattern. | Redesign PCR primers to amplify a different fragment of the target sequence [10]. |

| Too much Detection Enzyme is used or digestion incubation is too long. | Titrate the amount of Detection Enzyme and optimize the incubation time [10]. |

| Plasmid contamination in the sample. | Ensure single clones are picked when culturing the plasmid and avoid using excessive vector DNA in transfection [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms by which CRISPR-Cas9 can target bacterial biofilms?

CRISPR-Cas9 combats biofilms through two primary mechanistic approaches:

- Targeting Resistance Genes: The system can be programmed to introduce double-strand breaks in specific antibiotic resistance genes (e.g.,

bla,mecA,ndm-1), disrupting them and re-sensitizing the bacteria to conventional antibiotics [6] [12]. - Disrupting Biofilm Integrity: gRNAs can be designed to target and knockout genes critical for biofilm formation and maintenance. This includes genes involved in quorum sensing, the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and adhesion factors. For example, a study targeting the

smpBgene in Acinetobacter baumannii via CRISPR/Cas9 resulted in a significant reduction in biofilm formation (p = 0.0079) [11].

Q2: Why is a PAM sequence necessary, and what can I do if my target gene lacks a suitable PAM site?

- Necessity: The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence adjacent to the target site that is essential for the Cas9 nuclease to recognize and bind to the DNA for cleavage [11] [13].

- Solution: If your target locus lacks a suitable PAM sequence for SpCas9 (which requires an NGG PAM), alternative strategies exist. You can use Cas9 proteins from different bacterial species that recognize different PAM sequences. Alternatively, other gene-editing technologies, such as Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), can be employed, as they do not require a PAM sequence [10].

Q3: What are the key advantages of using nanoparticle systems for delivering CRISPR-Cas9 components against biofilms?

Nanoparticles offer several critical advantages for this application, addressing major delivery challenges:

- Enhanced Delivery Efficiency: They facilitate cellular uptake and can increase gene-editing efficiency, as demonstrated by gold nanoparticles which enhanced editing efficiency up to 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems [6].

- Biofilm Penetration: Engineered nanoparticles can penetrate the dense extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix of biofilms, delivering their cargo directly to the embedded bacterial cells [6].

- Protection of Components: They protect the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid DNA, mRNA, or ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) from degradation by nucleases in the environment [6] [13].

- Co-delivery Capability: Nanoparticles can be designed to co-deliver CRISPR components alongside antibiotics or antimicrobial peptides, creating a synergistic therapeutic effect for superior biofilm disruption [6].

Q4: How can I verify that my CRISPR-Cas9 system is successfully cleaving the intended genomic target in bacteria?

The GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit is a common tool for this purpose. This assay uses a specialized enzyme to detect and cleave mismatches in heteroduplex DNA formed after the CRISPR-induced double-strand break is repaired. The cleaved products are then visualized on an agarose gel. If no cleavage band is visible, it is recommended to use the kit's control template and primers to verify all components and procedures, and to optimize transfection efficiency [10].

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout to Assess Role in Biofilm Formation

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully mutated the smpB gene in Acinetobacter baumannii to investigate its role in biofilm formation, motility, and antibiotic susceptibility [11].

1. gRNA Design and Cloning:

- Design: Use a web tool like CHOPCHOP to design a gene-specific sgRNA. The targeting sequence (spacer) for the

smpBgene was: 5'-TTTCGTGTACGTGTAGCTTC-3' [11]. - Synthesis: Synthesize the sgRNA oligonucleotides commercially.

- Phosphorylation and Annealing: Phosphorylate the oligonucleotides with T4 Polynucleotide Kinase. Anneal the phosphorylated products to form a double-stranded DNA fragment.

- Cloning: Clone the annealed oligonucleotide into a suitable CRISPR plasmid (e.g., pBECAb-apr for A. baumannii) using a Golden Gate ligation reaction with enzymes like BsaI-HFv2 and T4 DNA ligase.

- Transformation: Transform the ligation product into competent E. coli DH5α cells via heat shock and plate on LB agar with the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., 50 μg/mL apramycin).

- Verification: Pick transformants and verify successful cloning by colony PCR with specific primers (e.g., Spacer-F' and M13R) and Sanger sequencing [11].

2. Delivery into Target Bacteria:

- Transform the verified plasmid into the competent target bacteria (e.g., A. baumannii) using your established method (e.g., heat shock).

3. Functional Phenotyping Assays:

- Biofilm Quantification: Use crystal violet staining to quantify biofilm biomass. Compare the biofilm formation of the mutant strain to the wild-type strain. Statistical analysis (e.g., unpaired t-test) should show a significant reduction (e.g.,

p = 0.0079) [11]. - Motility Assays: Perform swimming, swarming, and twitching motility assays to assess changes in bacterial movement.

- Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing: Use disk diffusion or broth microdilution methods to evaluate changes in sensitivity to various antibiotics (e.g., increased sensitivity to ceftizoxime, piperacillin/tazobactam, and gentamicin was observed in the

smpBmutant) [11].

Workflow: Utilizing Nanoparticles for Enhanced CRISPR Delivery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for using nanoparticles to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 components to bacterial biofilms, combining strategies from recent research.

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on CRISPR-Nanoparticle systems for anti-biofilm applications.

Table 1: Efficacy Metrics of CRISPR-Nanoparticle Hybrid Systems Against Biofilms

| Nanoparticle Type | Target Bacteria / Gene | Editing Efficiency / Biofilm Reduction | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomal Nanoparticles [6] | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | >90% reduction in biofilm biomass in vitro | Significant disruption of mature biofilm structures. |

| Gold Nanoparticles [6] | Model bacterial systems | 3.5-fold increase in editing efficiency | Enhanced delivery and precision of CRISPR-Cas9 components. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 (No NP) [11] | Acinetobacter baumannii smpB | Significant reduction in biofilm (p=0.0079) | Validated role of specific gene (smpB) in biofilm formation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Biofilm Research

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GeneArt CRISPR Nuclease Vector Kit [10] | Provides a backbone plasmid for cloning your specific gRNA sequence and expressing Cas9. | Creating a customized CRISPR plasmid for targeting a specific biofilm-related gene. |

| GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit [10] | Detects and validates CRISPR-Cas9-induced mutations in the bacterial genome. | Confirming successful cleavage of a target antibiotic resistance gene after transfection. |

| Lipid-Based Nanoparticles (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000) [10] | Enhates the delivery of CRISPR constructs into bacterial cells, especially in difficult-to-transfect strains. | Improving the transfection efficiency of a CRISPR plasmid in a mature biofilm. |

| Golden Gate Assembly Kit (BsaI-HFv2, T4 Ligase) [11] | Facilitates the efficient and directional cloning of gRNA sequences into CRISPR plasmids. | Assembling multiple gRNA expression cassettes for multiplexed gene targeting. |

| T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK) [11] | Phosphorylates synthetic oligonucleotides prior to annealing, which is a critical step for subsequent ligation into a plasmid. | Preparing synthesized ssDNA oligos for gRNA cloning. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is my CRISPR-Cas9 system failing to disrupt biofilm formation despite successful plasmid transformation?

Several factors related to Cas9 expression can cause this issue, even with successful transformation.

- Problem: Inadequate Cas9 expression or activity within bacterial cells.

Background: Biofilm-forming bacteria often have robust defense mechanisms and complex extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that can hinder delivery and function of CRISPR components [14]. The protective biofilm matrix limits penetration of antimicrobial agents and genetic tools [14].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Cas9 Protein Expression: Use Western blot analysis to confirm Cas9 protein is being expressed in your target cells. Low expression may indicate promoter compatibility issues [15].

- Check Delivery Efficiency: Traditional transfection methods may have low efficiency in biofilm-associated bacteria. Consider optimizing your delivery system using nanoparticles, which have demonstrated enhanced cellular uptake. Lipid-based nanoparticles can improve delivery, while gold nanoparticles have shown a 3.5-fold increase in editing efficiency in some systems [14].

- Assess Guide RNA Design: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., CRISPR Design Tool, Benchling) to confirm your sgRNA has high on-target specificity and minimal off-target effects. Test multiple sgRNAs targeting different regions of essential biofilm genes [16] [17].

- Evaluate Biofilm Assay Conditions: Ensure your biofilm disruption assays are conducted over an appropriate timeframe. CRISPR-mediated gene disruption may require multiple bacterial replication cycles to manifest phenotypically.

Prevention Tips:

- Use promoters known to function strongly in your specific bacterial strain.

- Employ high-fidelity Cas9 variants to reduce off-target effects that can cause cellular toxicity and reduce editing efficiency [16].

- Validate system components in planktonic cells before moving to complex biofilm models.

FAQ 2: How can I optimize Cas9 expression levels to maximize gene editing efficiency for biofilm-related targets?

Fine-tuning Cas9 expression is crucial for balancing high editing efficiency with minimal cytotoxicity.

- Problem: Suboptimal Cas9 expression leads to either low editing efficiency or cell toxicity.

Background: Excessive Cas9 can cause significant off-target effects and cellular toxicity, while insufficient levels result in incomplete gene editing [16] [18]. This balance is particularly important when targeting essential biofilm genes like those involved in quorum sensing, EPS production, and adhesion [14] [8].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Utilize Inducible Promoters: Implement inducible expression systems (e.g., tetracycline-, arabinose-, or rhamnose-inducible promoters) to precisely control the timing and level of Cas9 expression. This allows you to induce Cas9 only after successful delivery into biofilm-embedded cells.

- Employ Stable Cas9 Cell Lines: For recurrent studies, develop or procure cell lines that stably express Cas9. These provide more consistent and reproducible expression levels compared to transient transfection, improving experimental reliability [17].

- Modulate Delivery Dosage: If using plasmid or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, perform a dosage titration experiment. Start with lower concentrations and gradually increase to find the optimal balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [16].

- Codon Optimization: Ensure the Cas9 gene is codon-optimized for your specific bacterial host to enhance translation efficiency and protein expression [19].

Prevention Tips:

- Use Cas9 variants with improved specificity (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) to allow for higher expression levels with reduced off-target risks.

- Monitor cell viability and proliferation rates post-transfection as indicators of Cas9-induced toxicity.

- For nanoparticle-assisted delivery, optimize the Cas9:nanoparticle ratio for controlled release [14].

FAQ 3: What are the best methods to quantitatively evaluate Cas9-mediated knockout efficiency in biofilm studies?

Proper validation is essential to confirm successful gene editing before assessing biofilm phenotypes.

- Problem: Inaccurate measurement of gene knockout efficiency leads to misinterpretation of biofilm disruption results.

Background: qPCR is commonly used but has significant limitations for evaluating CRISPR knockout efficiency because it measures mRNA levels rather than functional protein disruption. A gene may be successfully knocked out at the DNA level while residual mRNA persists [15].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Genomic DNA Sequencing: Perform Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing of the target locus to directly identify insertion/deletion (indel) mutations at the DNA level. This provides the most accurate quantification of editing efficiency [15].

- Western Blot Analysis: Detect the presence or absence of the target protein. This is a crucial functional validation step, as successful knockout should eliminate protein expression [15].

- Phenotypic Confirmation: Conduct functional assays specific to your target gene. For example, if targeting a biofilm-related gene, assess changes in adhesion capacity, EPS production, or metabolic activity within the biofilm [11].

- Use T7 Endonuclease I Assay: Deploy this mismatch detection assay as an intermediate validation tool to confirm genome modification before proceeding to more resource-intensive sequencing.

Prevention Tips:

- Always use multiple complementary validation methods (genomic, protein, and functional) for comprehensive assessment.

- Include appropriate controls, including wild-type cells and cells transfected with non-targeting gRNA [16].

- For biofilm studies, correlate gene editing efficiency with quantitative biofilm metrics (e.g., biomass reduction, metabolic activity).

Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Data on Cas9 Delivery Systems for Biofilm Disruption

The table below summarizes performance data for different Cas9 delivery strategies from published research, highlighting the advantage of nanoparticle-based systems for biofilm applications [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Cas9 Delivery Systems for Biofilm Disruption

| Delivery System | Editing Efficiency | Biofilm Reduction | Key Advantages | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomal Nanoparticles | Not specified | >90% (P. aeruginosa, in vitro) | Enhanced cellular uptake, controlled release | Potential stability issues |

| Gold Nanoparticles | 3.5-fold increase vs. non-carrier | Significant synergistic effect with antibiotics | High stability, tunable surface chemistry | Synthesis complexity |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | High in model strains | Enhanced penetration in EPS matrix | Co-delivery of antibiotics/other agents possible | Variable efficiency in different species |

| Viral Vectors | High in susceptible strains | Limited by poor biofilm penetration | High efficiency for planktonic cells | Inefficient penetration through biofilm matrix [14] |

| Electroporation | Variable | Variable | Direct delivery | High cell death, challenging for in vivo use |

Detailed Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Editing in Biofilm-Forming Bacteria

This protocol is adapted from a study on Acinetobacter baumannii that successfully disrupted the smpB gene, resulting in significantly reduced biofilm formation [11].

- Primary Objective: To achieve precise gene knockout in a biofilm-forming bacterial strain and evaluate the subsequent impact on biofilm formation.

Key Materials:

- pBECAb-apr plasmid (or similar Cas9/sgRNA expression vector for your target bacteria)

- Chemically competent E. coli DH5α for plasmid propagation

- Target bacterial strain (e.g., Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC17978)

- Apramycin antibiotic for selection

- T4 Polynucleotide Kinase, T4 DNA Ligase, BsaI-HFv2 restriction enzyme

- Custom sgRNA oligonucleotides

Step-by-Step Workflow:

sgRNA Design and Cloning:

- Design sgRNAs targeting your gene of interest using web tools like CHOPCHOP. For biofilm disruption, consider genes involved in quorum sensing (lasI, rhlI), adhesion, or EPS production [8].

- Synthesize complementary oligonucleotides containing the target spacer sequence with appropriate overhangs for your chosen plasmid (e.g., Spacer-F: 5'-tagtTTTCGTGTACGTGTAGCTTC-3' and Spacer-R: 5'-aaacGAAGCTACACGTACACGAAA-3' for the pBECAb-apr system) [11].

- Phosphorylate and anneal the oligonucleotides using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase.

- Clone the annealed product into the BsaI-digested plasmid vector using a Golden Gate assembly reaction: 25 cycles of 37°C for 3 min and 16°C for 4 min, followed by 50°C for 5 min and 80°C for 10 min [11].

Transformation and Verification:

- Transform the ligation product into competent E. coli DH5α cells via heat shock and plate on selective media (e.g., LB agar with apramycin).

- Screen colonies by direct colony PCR using primers flanking the sgRNA insertion site to confirm successful cloning.

Delivery into Target Bacteria and Selection:

- Isolate the verified plasmid from E. coli.

- Introduce the plasmid into your target biofilm-forming bacterium (e.g., A. baumannii) using its preferred transformation method (e.g., electroporation).

- Plate transformed cells on selective media to isolate positive clones.

Validation of Gene Editing:

Biofilm Phenotyping:

- Grow the wild-type and mutant strains under conditions that promote biofilm formation.

- Quantify biofilm biomass using crystal violet staining assay [11].

- Assess biofilm structure via microscopy (e.g., confocal laser scanning microscopy or scanning electron microscopy).

- Perform functional assays relevant to the disrupted gene (e.g., motility assays if targeting motility-related genes) [11].

Cas9 Expression and Biofilm Disruption Pathway

This diagram illustrates the mechanistic relationship between optimized Cas9 expression and the subsequent molecular events leading to successful biofilm disruption.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Biofilm Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Specifics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Vector | Expresses the Cas9 nuclease in target cells. | Use a vector with a promoter functional in your target bacteria (e.g., a species-specific promoter). Inducible promoters allow for temporal control [11]. |

| sgRNA Cloning Plasmid | Expresses the target-specific guide RNA. | Ensure compatibility with your Cas9 vector. Vectors with different antibiotic resistance markers facilitate co-transformation [11]. |

| Nanoparticle Delivery System | Enhances delivery of CRISPR components into biofilm-embedded cells. | Liposomal (e.g., DharmaFECT) or gold nanoparticles can protect genetic material and improve uptake, crucial for penetrating EPS [14] [17]. |

| Validated sgRNA | Directs Cas9 to the specific DNA target sequence. | Design targeting essential biofilm genes (e.g., smpB in A. baumannii). Use bioinformatics tools to minimize off-target effects [17] [11]. |

| Selection Antibiotics | Selects for successfully transformed bacteria. | Apramycin is used in some systems like pBECAb-apr; choose based on your plasmid's resistance marker [11]. |

| DNA Modifying Enzymes | Facilitates molecular cloning of sgRNA. | T4 Polynucleotide Kinase, T4 DNA Ligase, and restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI-HFv2) for Golden Gate assembly [11]. |

| Biofilm Quantification Kits | Measures the impact of gene editing on biofilm formation. | Crystal violet staining kits for biomass; metabolic activity assays (e.g., resazurin-based); EPS composition analysis kits. |

| Sequencing Primers | Validates successful gene editing at the target locus. | Design primers flanking the CRISPR target site (~200-300bp amplicon) for PCR amplification and subsequent Sanger sequencing [15]. |

FAQs on Optimizing Cas9 Expression for Biofilm Inhibition

Q1: What are the key metrics for defining "sustained inhibition" in biofilm studies? Sustained biofilm inhibition is quantified by measuring the long-term reduction in biofilm biomass and the persistence of this effect after the initial CRISPR-Cas9 treatment. Key metrics include:

- Biomass Reduction: Successful interventions, such as liposomal Cas9 formulations, can reduce biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro [14].

- Bacterial Resensitization: The percentage of bacterial cells within the biofilm that have been resensitized to conventional antibiotics due to the disruption of resistance genes [14].

- Longevity of Effect: The duration for which the inhibitory effect persists, which is directly linked to the prevention of biofilm regrowth. This is influenced by how long the edited genetic effect lasts in the bacterial population [14] [20].

Q2: How does Cas9 expression time affect biofilm inhibition and off-target effects? The duration of Cas9 activity is a critical balancing act. Prolonged expression increases the potential for unintended, off-target edits in the bacterial genome, while transient expression may be insufficient for complete biofilm disruption [21] [13].

- Optimal Window: Strategies should aim for a Cas9 expression window that is long enough to achieve high-efficiency editing of the target biofilm-related genes (e.g., quorum sensing, adhesion, antibiotic resistance genes) but short enough to minimize off-target activity [21].

- Delivery Method is Key: Using delivery methods that result in transient Cas9 presence, such as ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes or mRNA, rather than plasmid DNA, can tightly control the expression window and has been shown to reduce off-target effects [22] [13].

Q3: What are the best delivery strategies to control Cas9 expression for biofilm targeting? The choice of delivery system is paramount for controlling where and for how long Cas9 is active.

- Nanoparticles for Enhanced Delivery: Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and other nanocarriers are highly effective. They protect CRISPR components, enhance penetration through the protective biofilm matrix, and can be engineered for controlled release. For instance, gold nanoparticles have been shown to enhance editing efficiency by up to 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems [14] [23].

- RNP Complexes for Precision: Direct delivery of pre-assembled Cas9 protein and guide RNA as an RNP complex facilitates rapid editing and decay, minimizing the time window for off-target activity. This method is superior to plasmid-based delivery for reducing off-target effects [22].

Q4: How can I troubleshoot low biofilm inhibition efficiency despite high Cas9 expression? If expression is high but inhibition is low, the issue likely lies in the efficiency of the editing process itself or the target chosen.

- Verify sgRNA Efficiency: Always test the cleavage efficiency of your single-guide RNA (sgRNA) in vitro before proceeding to complex biofilm models. Ineffective sgRNAs are a common point of failure [22] [24].

- Assess Delivery Penetration: Confirm that your delivery vector (e.g., LNP) is effectively penetrating the biofilm's extracellular polymeric substance (EPS). The EPS is a major barrier that can trap therapeutics [14] [25].

- Evaluate Editing Outcomes: Use mutation detection kits to sequence the target loci in bacteria extracted from the biofilm. A high percentage of indels at the target site confirms successful editing, guiding you to focus on delivery optimization if results are low [22].

Experimental Protocols for Key Metrics

Protocol 1: Quantifying Sustained Biofilm Inhibition

- Biofilm Formation: Grow a standardized biofilm of your target bacterium (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Escherichia coli) in a suitable system, such as a Calgary biofilm device or on a urinary catheter substrate [26].

- CRISPR-Cas9 Treatment: Apply your CRISPR-Cas9 therapeutic, ideally via a nanoparticle carrier [14].

- Biomass Assessment (Crystal Violet Staining):

- At defined time points post-treatment (e.g., 24h, 48h, 72h, 7 days), stain the biofilm with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes.

- Wash gently to remove unbound dye.

- Dissolve the bound dye in 30% acetic acid.

- Measure the absorbance at 595 nm. A sustained >90% reduction in absorbance compared to the control indicates successful inhibition [14] [26].

- Viability and Resensitization (Colony Forming Units - CFU):

- Harvest biofilm cells by scraping and sonication.

- Plate serial dilutions on agar plates with and without a sub-inhibitory concentration of a relevant antibiotic.

- The reduction in CFU counts on antibiotic-containing plates indicates successful disruption of antibiotic resistance genes and resensitization [14].

Protocol 2: Measuring Cas9 Expression and Editing Kinetics

- Delivery and Sampling: Transfert your biofilm-forming bacteria with your chosen Cas9 delivery system (plasmid, mRNA, or RNP) [22].

- Time-Course Sampling: Collect samples at multiple time points post-transduction (e.g., 6h, 24h, 48h, 96h, and up to 16 days for slow-dividing or persistent cells) [20].

- Assess Editing Efficiency:

- Plot Kinetics: Graph the indel percentage over time. The "optimal expression window" is the period where editing efficiency peaks before plateauing or where off-target effects begin to rise [20].

Protocol 3: Profiling Off-Target Effects

- In Silico Prediction: Use tools like CCTop or Benchling to computationally predict potential off-target sites with sequence homology to your sgRNA [21] [24].

- Biased Detection (Targeted Sequencing):

- Design PCR amplicons for the top ~10-20 predicted off-target sites.

- Perform targeted deep sequencing to quantify indel frequencies at these sites. This is a sensitive and quantitative method [21].

- Unbiased, Genome-Wide Detection:

- For a comprehensive profile, use methods like GUIDE-seq or Digenome-seq. These techniques can identify off-target sites without prior prediction but require more specialized protocols [21].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics from Recent Studies

| Metric | Target System | Reported Value | Delivery Method | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilm Biomass Reduction | P. aeruginosa | >90% reduction | Liposomal Cas9 Formulation | [14] |

| Gene-Editing Efficiency | General | Up to 3.5-fold increase vs. control | Gold Nanoparticle Carrier | [14] |

| Indel Efficiency (Single Gene) | hPSCs | 82% - 93% | Optimized iCas9 RNP System | [24] |

| Protein Knockdown (Ineffective sgRNA Example) | ACE2 in hPSCs | 80% INDELs, 0% Protein Loss | Plasmid DNA | [24] |

| Therapeutic Protein Reduction (in vivo) | hATTR (TTR protein) | ~90% sustained reduction | Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) | [23] |

Table 2: Impact of Cas9 Delivery Method on Key Parameters

| Delivery Method | Typical Expression Window | Off-Target Risk | Ease of Use | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA | Long / Persistent | High | Moderate | Stable cell line generation |

| mRNA | Short / Transient | Medium | Moderate | Transient editing in vitro |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Very Short / Acute | Lowest | Moderate (electroporation) | Precision editing, high specificity [22] |

| Virus-Like Particles (VLP) | Can be tuned | Low | Complex | Hard-to-transfect cells (e.g., neurons) [20] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) | Can be tuned | Low | Complex | In vivo therapeutic delivery [14] [23] |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Biofilm Research

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Consideration in Biofilm Context |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA In Vitro Transcription Kit | Produces high-yield sgRNA for screening. | Test multiple sgRNAs in vitro before committing to complex biofilm experiments [22]. |

| In Vitro Cleavage Assay Kit | Tests sgRNA efficacy before cellular use. | Crucial for confirming guide activity against target biofilm genes like luxS or fimH [22] [26]. |

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | Enables formation of RNP complexes. | Using RNPs with synthetic, chemically modified sgRNAs can enhance stability and editing efficiency in biofilms [22] [24]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery of CRISPR payload. | Excellent for targeting biofilm infections; can be co-loaded with antibiotics for synergistic effect [14] [23]. |

| Mutation Detection Kit | PCR-based detection of indels. | Use to quantify editing efficiency in bacteria harvested and dispersed from a treated biofilm [22]. |

| Long ssDNA Production System | Generates single-stranded DNA repair templates. | Useful for knock-in experiments or precise gene corrections within biofilm bacteria [22]. |

Advanced Systems for Controlled Cas9 Delivery and Expression in Biofilm Environments

Inducible Expression Systems (e.g., Doxycycline-inducible iCas9) for Tunable Control

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for using inducible expression systems to optimize Cas9 expression for sustained biofilm inhibition research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the key advantage of using a drug-inducible CRISPR-Cas9 system over a constitutive one? A drug-inducible system allows for precise temporal control over genetic perturbations. This enables researchers to initiate gene editing at a specific time, which is crucial for studying dynamic processes like biofilm development and for avoiding pleiotropic effects that might arise from early, constitutive gene knockout [27].

Q2: Can I use doxycycline as an inducer in my Tet-On system, and what concentration should I use? Yes, doxycycline is a suitable and often preferred inducer for Tet-On systems due to its longer half-life (48 hours) compared to tetracycline (24 hours). It is recommended to perform a dose-response curve to determine the optimal concentration for your specific experimental setup, as this can minimize off-target effects [28] [29].

Q3: My inducible system shows high background activity (leakiness) without the inducer. How can I address this? Leakiness can be significantly reduced by using a system with optimized regulatory elements. One effective strategy is using a sgRNA expression vector with two Tet operator (2xTetO) sites in the U6 promoter, which has been shown to provide tight control with minimal background activity across various cell lines [27].

Q4: Why is my protein not expressing after induction in the Expi293F inducible system? Several common issues can cause low protein expression:

- Low transfection efficiency: Optimize your transfection protocol.

- Protein degradation or toxicity: The expressed protein may be unstable or toxic to the cells.

- Insufficient induction or incubation time: Ensure the inducer concentration is correct and that the expression culture is not incubated for too long, as viability drops after 7 days [30] [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Gene Editing Efficiency Upon Induction

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal gRNA design | Design gRNAs with high specificity and minimal off-target potential using validated algorithms. Ensure the target sequence is unique within the genome [16] [31]. |

| Inefficient delivery of CRISPR components | Optimize transfection methods (e.g., electroporation, lipofection) for your specific cell type. Using nanoparticles as carriers can enhance delivery efficiency [6] [16]. |

| Low expression of Cas9 or gRNA | Verify that the promoters driving Cas9 and gRNA are active in your cell type. Ensure the use of high-quality, pure plasmid DNA [16] [30]. |

| Insufficient inducer concentration or incubation time | Perform a dose-response curve with the inducer (e.g., doxycycline) to find the optimal concentration. Extend the incubation time post-induction to allow for sufficient editing [28] [29]. |

Problem 2: High Background Editing in the Absence of Inducer (Leakiness)

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal inducible promoter design | Utilize a tightly controlled promoter system. A 2xTetO-U6 promoter has been demonstrated to reduce leakiness to 0-14% across multiple cell lines while maintaining high inducible activity [27]. |

| Cell line-specific effects | Test the inducible system in multiple cell lines. Some cell lines may exhibit higher basal activity, requiring further optimization of repressor protein expression levels [27]. |

| Genomic instability of engineered cells | Use early-passage cells and perform genotyping to ensure the integrity of the stably integrated inducible cassette [29]. |

Problem 3: Cell Toxicity or Low Viability After Transfection/Induction

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| High concentration of CRISPR components | Titrate the amount of transfected Cas9/gRNA plasmids or ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [16]. |

| Cytotoxicity of the transfection reagent | Optimize the ratio of transfection reagent to DNA/RNA. Consider alternative, less toxic delivery methods such as nucleofection or nanoparticle carriers [6] [31]. |

| Off-target effects of Cas9 | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants and design specific gRNAs to minimize off-target cleavage [16]. |

| Side effects of the inducer (e.g., Doxycycline) | Be aware that doxycycline itself can impair mitochondrial function and alter cell proliferation. Use the lowest effective concentration and include appropriate controls (e.g., wild-type cells + doxycycline) to account for these effects [29]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Performance of Inducible Systems

The following table summarizes data from a study that developed and tested multiple drug-inducible CRISPR-Cas9 systems in various cell lines, providing a benchmark for expected performance [27].

| Inducible System Design | Leakiness Score (Background without inducer) | Activity Score (Efficiency with inducer) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1xTetO-U6 promoter | High | 39% - 99% of constitutive system | High background activity, insufficient transcription inhibition. |

| 2xTetO-U6 promoter | 0% - 14% | 39% - 99% of constitutive system | Minimal leakiness, high inducible efficiency. Recommended for tight control. |

| 1xLacO-U6 promoter | 0% - 21% | 10% - 97% of constitutive system | IPTG-inducible, shows dose-dependent control. |

| 2xLacO-U6 promoter | 0% - 21% | 10% - 97% of constitutive system | IPTG-inducible, similar leakiness to 1xLacO. |

Workflow for Implementing a Doxycycline-Inducible iCas9 System

This diagram illustrates the key steps for establishing and using a Doxycycline-inducible iCas9 system for biofilm research.

Mechanism of CRISPRi for Biofilm Gene Knockdown

For biofilm inhibition, a non-cutting approach (CRISPRi) using catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) can be used to repress gene expression. This diagram shows how dCas9-sgRNA blocks transcription of a quorum-sensing gene (e.g., luxS) to inhibit biofilm formation [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| pcDNA6/TR Vector | Stably expresses the Tet Repressor (TetR) protein, required for inducible systems. | Parental cell line must be compatible. Expi293F Inducible cells are pre-engineered with this vector [28]. |

| pcDNA5/TO Expression Vector | Carries the gene of interest (e.g., Cas9) under a tetracycline/doxycycline-inducible promoter [28]. | The gene of interest is cloned into this vector for regulated expression. |

| Doxycycline | Small-molecule inducer. Binds TetR, triggering expression from the inducible promoter [28] [29]. | Has a 48-hour half-life. Perform a dose-response curve (e.g., 0-2 µg/ml) to optimize concentration and minimize cytotoxicity [29] [28]. |

| Lipofectamine 3000/2000 | Lipid-based transfection reagent for delivering plasmids into mammalian cells. | Efficiency is cell-line dependent. Optimize conditions for your specific cell type [31]. |

| Nanoparticles (e.g., Gold, Lipid) | Serve as carriers for CRISPR components, enhancing cellular uptake, stability, and delivery efficiency, especially in biofilm environments [6]. | Can be engineered for targeted delivery and controlled release, and can co-deliver antibiotics for synergistic effects [6]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I / Surveyor Assay | Enzymatic kits used to detect successful genome editing by identifying mismatches in re-annealed PCR products. | Employ robust genotyping methods like these to confirm mutations at the target site [16] [31]. |

| Crystal Violet / XTT Assay | Standard methods to assess biofilm biomass and cellular viability within biofilms, respectively [32]. | Used to quantify the phenotypic outcome of genetic perturbations on biofilm formation and health. |

Nanoparticle Carriers for Enhanced Delivery and Protection of CRISPR Components

FAQs: Nanoparticle Delivery for CRISPR-Cas9

Q1: What are the main advantages of using nanoparticles over viral vectors for delivering CRISPR-Cas9 in biofilm research? Nanoparticles offer several key advantages for CRISPR delivery in antibiofilm applications. Unlike viral vectors, they have a lower risk of eliciting immune responses and causing insertional mutagenesis [33]. Their tunable surface chemistry allows for functionalization to enhance biofilm penetration and target specific bacterial cells [14]. Furthermore, nanoparticles can co-deliver multiple cargo types, including Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP), antibiotics, and quorum-sensing inhibitors, enabling a synergistic attack on biofilm integrity and bacterial viability [14] [34].

Q2: What types of CRISPR cargo can be delivered using nanoparticles, and which is most suitable for reducing off-target effects? Nanoparticles can deliver three primary forms of CRISPR cargo, each with distinct properties, as summarized in the table below.

| Cargo Type | Components | Key Advantages | Considerations for Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | DNA encoding Cas9 and gRNA [35] | Simpler to produce and load into carriers [35] | Prolonged Cas9 expression can increase off-target effects; lower transfection efficiency due to large size [35] [36] |

| Messenger RNA (mRNA) | Cas9 mRNA + separate gRNA [35] | No risk of genomic integration; direct protein translation in cytoplasm [35] | Transient activity reduces off-target risk; high instability requires protective carriers [35] [36] |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Preassembled Cas9 protein + gRNA complex [35] [36] | Fastest editing action; greatly reduced off-target effects due to short activity window [35] [36] | Immediate activity is ideal for targeting rapidly metabolizing biofilm cells; requires delivery of large protein complexes [14] |

For research focused on minimizing off-target effects, such as optimizing sustained Cas9 expression for biofilm inhibition, RNP delivery is often the preferred choice due to its precision and transient activity [36].

Q3: Which nanoparticles have shown the most promise for delivering CRISPR components against biofilms? Recent studies highlight the efficacy of specific nanoparticle types. Liposomal nanoparticles have demonstrated a remarkable ability to reduce Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro when delivering CRISPR-Cas9 [14]. Similarly, gold nanoparticles have been shown to enhance gene-editing efficiency by up to 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems, providing a robust platform for RNP delivery into bacterial cells within the biofilm matrix [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Nanoparticle-based CRISPR Delivery

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency in biofilm models | Inefficient penetration of nanoparticle through biofilm matrix [14] | Functionalize nanoparticles with matrix-degrading enzymes (e.g., Dispersin B, DNase I) to disrupt EPS [34]. |

| Nanoparticle is trapped in endosomes and cannot release cargo [36] | Formulate nanoparticles with endosomolytic lipids (e.g., DOTAP) or polymers to promote endosomal escape [35]. | |

| High off-target editing | Prolonged expression of Cas9 nuclease from pDNA cargo [36] | Switch from pDNA to RNP cargo for more transient and controlled activity [35] [36]. |

| Low nanoparticle stability or aggregation | Unoptimized surface charge or storage conditions [37] | Use PEGylation to improve stability; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles by storing aliquots at -20°C [37]. |

| High cytotoxicity | Cationic lipid/polymer concentration is too high [35] | Optimize the lipid-to-cargo ratio; consider using biodegradable lipid-like nanoparticles (LLNs) to reduce toxicity [35]. |

| No cleavage band detected (in validation assays) | gRNA designed against a poorly accessible genomic region; low transfection efficiency [37] | Redesign gRNAs for different target sites adjacent to a PAM sequence; optimize transfection protocol and use a positive control [37]. |

Essential Workflow: RNP Delivery via Liposomal Nanoparticles for Biofilm Inhibition

This protocol details a methodology for leveraging liposomal nanoparticles to deliver Cas9 RNP for targeted gene editing in biofilm-forming bacteria, a key strategy for sustained biofilm inhibition.

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To inhibit biofilm formation by using LNP-delivered Cas9 RNP to knockout a key quorum-sensing or antibiotic resistance gene.

Materials:

- Cas9 Protein: Purified, recombinant Cas9 nuclease.

- sgRNA: Synthesized and purified sgRNA targeting the gene of interest (e.g., lasI in P. aeruginosa for quorum sensing disruption).

- Lipid Nanoparticles: Composed of ionizable lipids, DSPC, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid [35].

- Biofilm Model: In vitro biofilm cultured in a flow cell or microtiter plate.

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM): For analyzing biofilm architecture and biomass.

Method:

- RNP Complex Formation: Pre-complex the Cas9 protein and sgRNA at a optimal molar ratio (e.g., 1:2) in a suitable buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 10-15 minutes to form the RNP complex [35].

- Nanoparticle Formulation and Loading: Prepare LNPs using a microfluidic mixer. Combine the lipid mixture in ethanol with the aqueous RNP complex solution. The rapid mixing leads to the spontaneous formation of LNPs encapsulating the RNP [35]. Purify the formulated LNP-RNPs via dialysis or tangential flow filtration.

- Biofilm Treatment: Apply the LNP-RNP formulation to a mature (e.g., 48-hour) biofilm model. Include controls: untreated biofilm, biofilm treated with empty LNPs, and scramble sgRNA RNP-LNPs.

- Assessment of Biofilm Inhibition:

- Biomass Quantification: Use crystal violet staining to measure total biofilm biomass after treatment.

- Viability Assessment: Perform colony-forming unit (CFU) counts to determine bacterial viability within the biofilm.

- Structural Analysis: Use CLSM with live/dead staining to visualize the 3D architecture and integrity of the biofilm.

- Validation of Gene Editing:

- Cleavage Assay: Isolve genomic DNA from treated and control biofilms. Use a genomic cleavage detection kit (e.g., T7E1 assay or tracking of indels by decomposition) to confirm targeted DNA modification [37].

- Sequencing: Perform Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing of the PCR-amplified target locus to precisely characterize the induced mutations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Nanoparticle Biofilm Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Characteristics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Cationic Lipids | Core component of LNPs; encapsulates and protects nucleic acid/protein cargo and facilitates endosomal escape [35]. | Biodegradable lipids (e.g., with ester groups or disulfide bonds) can reduce long-term toxicity and improve cargo release [35]. |

| Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | The active gene-editing complex; directly cleaves target DNA sequences. | Preferred for minimal off-target effects and rapid activity. High-purity, endotoxin-free protein is critical for consistent results [35] [36]. |

| Dispersin B / DNase I | Enzyme added to nanoparticle formulation or treatment to degrade polysaccharides (Dispersin B) or eDNA (DNase I) in the biofilm matrix [34]. | Enhances nanoparticle penetration through the protective extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) [14] [34]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer conjugated to nanoparticle surface (PEGylation) to improve stability, reduce nonspecific interactions, and extend circulation time [35]. | Can sometimes hinder cellular uptake; strategies like removable PEG shields can be explored [35]. |

| Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) Molecules | Lipids incorporated into LNP formulations to direct nanoparticles to specific tissues or cell types beyond the liver [36]. | Enables more precise targeting of biofilms in specific infection sites (e.g., lungs, implants) [36]. |

| Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit | Validates the success of CRISPR editing by detecting indels at the target genomic locus after treatment [37]. | Essential for confirming on-target efficiency and correlating it with the observed phenotypic outcome (biofilm inhibition) [37]. |

Promoter Engineering and Vector Design to Maximize Cas9 Production in Target Cells

FAQs: Core Concepts for Maximizing Cas9 Production

Q1: Why is promoter selection critical for achieving high Cas9 production in target cells?

Promoter selection directly determines the strength and specificity of Cas9 expression. Using a promoter that is highly active in your specific cell type ensures robust transcription of the Cas9 gene, leading to higher protein production. For example, the human U6 promoter is commonly used to drive guide RNA expression because it prefers a 'G' at the transcription start site for high expression [38]. Furthermore, selecting a promoter that functions optimally in your target bacterial or human cells is a foundational step in vector design to ensure sufficient Cas9 levels for effective gene editing in biofilm inhibition studies.

Q2: What are the key differences between using plasmid DNA, mRNA, or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) for Cas9 delivery?

The choice of delivery method impacts Cas9 production kinetics, duration of expression, and potential immune responses. The table below summarizes the key characteristics.

| Delivery Method | Mechanism of Cas9 Production | Duration of Expression | Key Advantages | Considerations for Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA | Transcription and translation inside the host cell [38]. | Longer, sustained | Cost-effective; stable for cloning. | Risk of random genomic integration; slower Cas9 onset; can trigger immune sensors. |

| mRNA | Direct translation in the cytoplasm [39]. | Shorter, transient | Rapid protein production; no risk of genomic integration. | Requires protection from degradation (e.g., via capping and tailing); can be immunogenic. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and gRNA is active immediately upon delivery. | Shortest, most transient | Fastest editing action; minimal off-target effects and low immunogenicity [16]. | Requires efficient delivery of large protein complexes; editing is confined to a short window. |

Q3: How can vector design be optimized to enhance the stability and translation efficiency of Cas9 mRNA?

Optimizing the engineering of mRNA is a key strategy to enhance stability and translation efficiency [39]. Critical elements include:

- 5' Capping and 3' Poly-A Tail: These modifications are essential for mRNA stability, nuclear export, and efficient translation initiation.

- Codon Optimization: Modifying the Cas9 gene sequence to use codons that are preferred by the host organism (e.g., humanized Codons for human cells) significantly improves translation efficiency and Cas9 yield [16].

- Regulatory UTRs: Incorporating untranslated regions (UTRs) that enhance mRNA stability and ribosome binding can further boost protein production.

Q4: What strategies can be used to maintain sustained Cas9 expression for long-term biofilm inhibition studies?

For sustained expression, creating stably expressing Cas9 cell lines is the most reliable method. These engineered cell lines provide continuous Cas9 expression, eliminating the variability of transient transfection and ensuring a consistent source of the nuclease for long-duration experiments [17]. Alternatively, for in vivo applications, the use of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) has enabled the possibility of redosing, as they do not trigger the same immune responses as viral vectors, allowing for multiple administrations to maintain therapeutic editing levels [23].

Q5: How does the choice of delivery vector (e.g., LNP, viral vectors) impact Cas9 production in target cells?

The delivery vector determines the efficiency with which CRISPR components enter target cells. Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) have shown high efficacy, particularly for liver-targeted delivery, and allow for redosing [23]. In biofilm research, nanoparticles can serve as effective carriers for CRISPR-Cas9 components, enhancing cellular uptake, protecting the genetic material, and ensuring controlled release within the biofilm environment. For instance, liposomal Cas9 formulations have reduced P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro, and gold nanoparticle carriers have enhanced editing efficiency up to 3.5-fold [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Low Cas9 Editing Efficiency

Low knockout efficiency indicates that the target gene is not being effectively disrupted in a high percentage of cells [17].

- Problem: Inefficient delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components into target cells.

Solution:

- Optimize Transfection Method: Use highly efficient lipid-based transfection reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine, DharmaFECT) or electroporation for hard-to-transfect cell types [17].

- Utilize Advanced Delivery Systems: Employ nanoparticle-based carriers (e.g., lipid, polymeric, or gold nanoparticles) engineered to enhance cellular uptake and protect CRISPR components from degradation [6].

Problem: Suboptimal sgRNA design leading to poor binding to the target DNA.

Solution:

- Use Bioinformatics Tools: Leverage algorithms (e.g., CRISPR Design Tool, Benchling) to design sgRNAs with high predicted on-target activity and minimal off-target effects. These tools assess GC content, secondary structure, and specificity [40] [17].

- Test Multiple sgRNAs: Empirically test 3–5 different sgRNAs against your target gene to identify the most effective one [38] [17].

Problem: Low expression of Cas9 and gRNA from the vector.

- Solution:

- Verify Promoter Suitability: Confirm that the promoter (e.g., U6 for gRNA, CMV or EF1α for Cas9) is functional in your specific cell type.

- Check Vector Quality: Ensure the plasmid DNA is pure, undegraded, and of high concentration [16].

Inconsistent or Mosaic Editing

This occurs when edited and unedited cells coexist within the same population [16].

- Problem: Variable expression of CRISPR components across the cell population due to asynchronous delivery.

- Solution:

Cell Toxicity and Low Viability

Cell death following CRISPR delivery can drastically reduce experimental success.

- Problem: High concentrations of CRISPR-Cas9 components, particularly when delivered via plasmid DNA, can trigger innate immune responses and cause cytotoxicity.

- Solution:

- Titrate Component Concentration: Start with lower doses of CRISPR components and titrate upwards to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [16].

- Switch Delivery Modality: Use RNP complexes, which are less toxic and act rapidly, or mRNA, which avoids the immune sensors triggered by plasmid DNA [39] [16].

Quantitative Data for Protocol Optimization

The following table summarizes key parameters from established protocols to guide your experimental design for high-efficiency Cas9 production and editing.

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters for CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery and Homologous Recombination

| Experimental Parameter | Recommended Specification | Protocol Details & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Homology Arm Length (Plasmid Donor) | ~800 bp [38] | Used for large insertions (>100 bp); co-transfect with Cas9/sgRNA vector. |

| Homology Arm Length (ssODN Donor) | 50–80 bp (per arm) [38] | Used for small changes (<50 bp); total oligo length ~100-150 bp; PAGE-purified. |

| Distance from DSB to Mutation | < 10 bp (ideal), < 100 bp (max) [38] | The double-strand break should be as close as possible to the intended edit. |

| Donor Plasmid Amount (24-well) | ~400 ng [38] | For a ~5 kb donor plasmid co-delivered with Cas9/sgRNA vectors. |

| sgRNA Design | Start with 'G' for U6 promoter [38] | The human U6 promoter has high expression if transcription starts with a 'G'. |

| Liposomal CRISPR-Cas9 Formulation | >90% biofilm biomass reduction [6] | Demonstrated against P. aeruginosa biofilms in vitro. |

| Gold Nanoparticle Carrier | 3.5x editing efficiency increase [6] | Enhanced efficiency compared to non-carrier delivery systems. |

Essential Workflow for Optimizing Cas9 Production

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for troubleshooting and optimizing Cas9 production in your experiments, from design to validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Optimizing Cas9 Production and Delivery

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| U6 Promoter Vectors | Drives high-level expression of gRNA in mammalian cells. | Ensure transcription starts with a 'G' for optimal activity [38]. |

| Strong Constitutive Promoters | Drives robust Cas9 protein expression. | Use promoters like CMV, EF1α, or Cbh that are known to be strong in your target cell type. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery vehicle for in vivo mRNA or RNP delivery. | Excellent for liver targeting; allows for potential redosing [23]. |

| Gold/Polymeric Nanoparticles | Carrier for CRISPR components to enhance biofilm penetration. | Can be functionalized for targeting; provides protection and controlled release [6]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Reduces off-target effects while maintaining on-target activity. | Crucial for therapeutic applications and improving data specificity [16]. |

| Stable Cas9 Cell Lines | Provides consistent, uniform Cas9 expression. | Eliminates variability from transient transfection; ideal for long-term studies [17]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Designs highly specific sgRNAs and predicts off-target sites. | Tools like Benchling or CRISPR Design Tool are essential for preliminary design [40] [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental principle behind Cas9-antibiotic co-delivery?

The co-delivery strategy involves simultaneously administering the CRISPR-Cas9 system and conventional antibiotics to target bacterial infections. Cas9 is programmed to precisely disrupt specific antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., ermB, tetM, mcr-1) or biofilm-related genes within bacterial cells [41] [42] [43]. This targeted gene disruption resensitizes the bacteria to the antibiotic, which then acts as the primary killing agent. The combination achieves a synergistic effect where the antibiotic's efficacy is restored, leading to enhanced bacterial clearance compared to using either agent alone [14].

FAQ 2: Why are co-delivery strategies particularly promising for treating biofilm-associated infections? Biofilms are structured microbial communities encased in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) that can be up to 1000 times more tolerant to antibiotics than free-floating (planktonic) bacteria [14]. The EPS acts as a diffusion barrier, limits antibiotic penetration, and harbors metabolically dormant "persister" cells. Co-delivery strategies address this by using nanoparticles to penetrate the biofilm and deliver Cas9 components that target the genetic basis of this tolerance, thereby breaking down the biofilm's defenses and resensitizing the embedded cells to the co-delivered antibiotic [5] [14].

FAQ 3: What are the most common delivery vehicles for these synergistic systems, and how do I choose? The choice of delivery vehicle depends on the target bacterium and the intended application. The main categories are:

- Biological Vectors: These include engineered plasmids (e.g., pheromone-responsive plasmids in Enterococcus faecalis) [41] and bacteriophages. They offer high specificity and natural infection mechanisms.

- Nanoparticles (NPs): These include lipid-based, polymeric, and metallic (e.g., gold) nanoparticles [14]. They can be engineered for enhanced biofilm penetration, controlled release, and can simultaneously carry multiple therapeutic agents (Cas9 components and antibiotics). They are highly versatile and can protect their cargo from degradation.

- Conjugative Plasmids: These can facilitate the transfer of CRISPR-Cas systems from donor to recipient bacterial cells, effectively spreading the resensitizing machinery through a population [42].

FAQ 4: I am not observing the expected synergistic effect in my biofilm model. What could be wrong? A lack of synergy often points to an issue with delivery efficiency or target selection. Please refer to the "Troubleshooting Guide" below for a detailed, step-by-step diagnostic procedure.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Low Synergistic Efficacy in Biofilm Inhibition

This guide will help you systematically diagnose and resolve issues when the combined application of CRISPR-Cas9 and antibiotics fails to produce the expected synergistic reduction in biofilm biomass or viability.

Step 1: Verify Functional Cas9 Delivery and Expression

Before assessing synergy, confirm that the Cas9 system is successfully entering the bacterial cells and functioning as intended.

1.1. Check Delivery Efficiency:

- Method: Use a plasmid that expresses a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP) upon successful delivery and Cas9 expression. Analyze fluorescence using flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy.

- Expected Outcome: A high percentage of fluorescent cells indicates successful delivery. If efficiency is low (<10%), consider optimizing the delivery vehicle. For nanoparticle-based delivery, you may need to adjust the nanoparticle-to-bacteria ratio or surface functionalization to improve uptake [14].

1.2. Confirm On-Target DNA Cleavage:

- Method: Perform a PCR on the target genomic region (e.g., the

ermBortetMgene) from treated bacteria, followed by gel electrophoresis. Successful Cas9 cleavage will result in DNA repair via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), introducing indels that can be detected as a smear or size shift on the gel, or more precisely by sequencing. - Expected Outcome: A clear wild-type band suggests ineffective Cas9 activity, while a smear or multiple bands indicate successful cleavage and mutagenesis [41].

- Method: Perform a PCR on the target genomic region (e.g., the

Step 2: Assess Antibiotic Susceptibility Restoration

After confirming Cas9 activity, determine if the genetic targeting has successfully resensitized the bacteria to the antibiotic.

- 2.1. Conduct Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assays:

- Protocol:

- Grow the target bacteria (e.g., a strain carrying

mcr-1) and treat with the CRISPR-Cas9 system targeting the resistance gene. - After a suitable incubation period (e.g., 4-6 hours), subculture the bacteria into fresh medium containing a dilution series of the antibiotic (e.g., colistin).

- Incubate for 16-20 hours and determine the MIC by visual inspection of turbidity.

- Grow the target bacteria (e.g., a strain carrying

- Expected Outcome: A significant decrease (e.g., 4 to 8-fold) in the MIC for the Cas9-treated group compared to the untreated control indicates successful resensitization [42] [43]. If the MIC does not change, the guide RNA may be ineffective, or an alternative resistance mechanism may be present.

- Protocol:

Step 3: Optimize Co-delivery Timing and Ratios

Synergy depends on the temporal and quantitative coordination between genetic disruption and antibiotic action.

3.1. Establish a Staggered Delivery Protocol:

- Method: Pre-treat the biofilm with the CRISPR-Cas9 system for 4-6 hours to allow for gene disruption. Then, add the antibiotic and continue the incubation. This staggered approach gives Cas9 time to degrade its target before the antibiotic is applied.

- Expected Outcome: Pre-treatment often yields stronger synergy than simultaneous administration, as it allows for the degradation of resistance determinants before antibiotic challenge [14].

3.2. Titrate Component Ratios:

- Method: If using a nanoparticle that co-encapsulates both Cas9 components and an antibiotic, prepare formulations with different mass ratios of gRNA to antibiotic. Test these formulations in a biofilm viability assay (e.g., using crystal violet staining for biomass or CFU counting for viability).

- Expected Outcome: An optimal ratio will show a significant log reduction in viable counts compared to either component alone or other suboptimal ratios. For example, some liposomal Cas9-antibiotic formulations have been shown to reduce P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro [14].

Quantitative Data on Co-delivery Efficacy

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from published studies on Cas9-antibiotic co-delivery strategies.

Table 1: Efficacy Metrics of Representative Co-delivery Strategies

| Target Bacterium & Resistance Gene | Delivery Vehicle | Antibiotic Used | Key Efficacy Metric | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (mcr-1) [42] | Conjugative Plasmid | Colistin | Plasmid Curing & MIC Reduction | Conjugation efficiency ~10⁻¹; successful resensitization to colistin [42]. |

| P. aeruginosa Biofilm [14] | Liposomal Nanoparticles | Not Specified | Biofilm Biomass Reduction | >90% reduction in biofilm biomass in vitro [14]. |

| E. faecalis (ermB, tetM) [41] | Pheromone-Responsive Plasmid (pPD1) | Erythromycin, Tetracycline | Reduction of Resistant Transconjugants | Significant, sequence-specific reduction of antibiotic-resistant populations in vitro and in murine intestine [41]. |

| General Nanoparticle Delivery [14] | Gold Nanoparticles | Various | Gene-Editing Efficiency | Up to 3.5-fold increase in editing efficiency compared to non-carrier systems [14]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials and their functions for setting up co-delivery experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Co-delivery Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid System | Expresses the Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA(s) inside the target bacterium. | pPD1-derived plasmids for Enterococcus [41]; pMBLcas9 for E. coli [42]. Must include a constitutive promoter for Cas9 expression. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Provides sequence specificity by guiding Cas9 to the target DNA. | Designed to target specific antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., ermB, tetM, mcr-1, blaNDM) [41] [42]. |

| Nanoparticle Carrier | Protects and delivers Cas9 components (and antibiotics) to the target site, enhancing biofilm penetration. | Liposomes, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), or polymer-based NPs. Can be functionalized with targeting ligands [14]. |

| Pheromone-Inducible System | Controls conjugation in Gram-positive bacteria for precise, high-efficiency plasmid delivery. | Used in E. faecalis; responds to recipient-secreted pheromones to trigger conjugation [41]. |

| Inducible dCas9 System (CRISPRi) | Allows for tunable gene knockdown without DNA cleavage, useful for studying essential genes. | IPTG-inducible dCas9 systems (e.g., pLOW-Pspac2-dcas9) enable controlled gene repression for fitness studies [44]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conjugative Delivery of CRISPR-Cas for Plasmid Curing