Optimizing Extraction Methods for Diverse Clinical Samples: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nucleic acid and bioactive compound extraction methodologies tailored for diverse clinical samples.

Optimizing Extraction Methods for Diverse Clinical Samples: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nucleic acid and bioactive compound extraction methodologies tailored for diverse clinical samples. It explores foundational principles, including the critical impact of extraction techniques on yield, purity, and downstream analytical success. The content details specific methodological applications for samples like whole blood, urine, and tissues, addressing common challenges and optimization strategies. A strong emphasis is placed on the comparative evaluation and validation of various methods, including conventional, commercial kit-based, and automated systems. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current trends to guide the selection and refinement of extraction protocols, ultimately enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of molecular diagnostics and biomedical research.

Core Principles and Sample-Specific Challenges in Clinical Extraction

The Critical Impact of Extraction Choice on Downstream Analysis Success

The selection of an appropriate extraction method is a critical first step that fundamentally influences the success and reliability of all subsequent analytical procedures in clinical and pharmaceutical research. Efficient extraction methods are paramount in analytical chemistry, environmental testing, pharmaceuticals, and food science for isolating target compounds from complex mixtures [1]. The choice of technique directly impacts the yield, purity, and integrity of the extracted analytes, thereby determining the accuracy, sensitivity, and reproducibility of downstream analyses. This technical support guide addresses common extraction challenges and provides evidence-based troubleshooting strategies to enhance methodological robustness across diverse clinical sample types.

Core Extraction Principles and Method Selection

Comparison of Major Extraction Techniques

Understanding the fundamental differences between common extraction methods enables researchers to make informed selections based on their specific analytical requirements.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Extraction Methods

| Aspect | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) | Filtration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Selective analyte isolation | Solvent-based partitioning | Particulate removal |

| Selectivity | High | Moderate | Low |

| Solvent Use | Low to moderate | High | None to low |

| Sample Volume | Small to moderate | Large | Small to large |

| Automation Potential | High | Low | Moderate |

| Labor Requirements | Moderate | High | Low |

| Best For | Selective isolation from complex matrices | Large volumes, nonpolar/semi-polar analytes | Removing suspended particulates |

Decision Framework for Extraction Method Selection

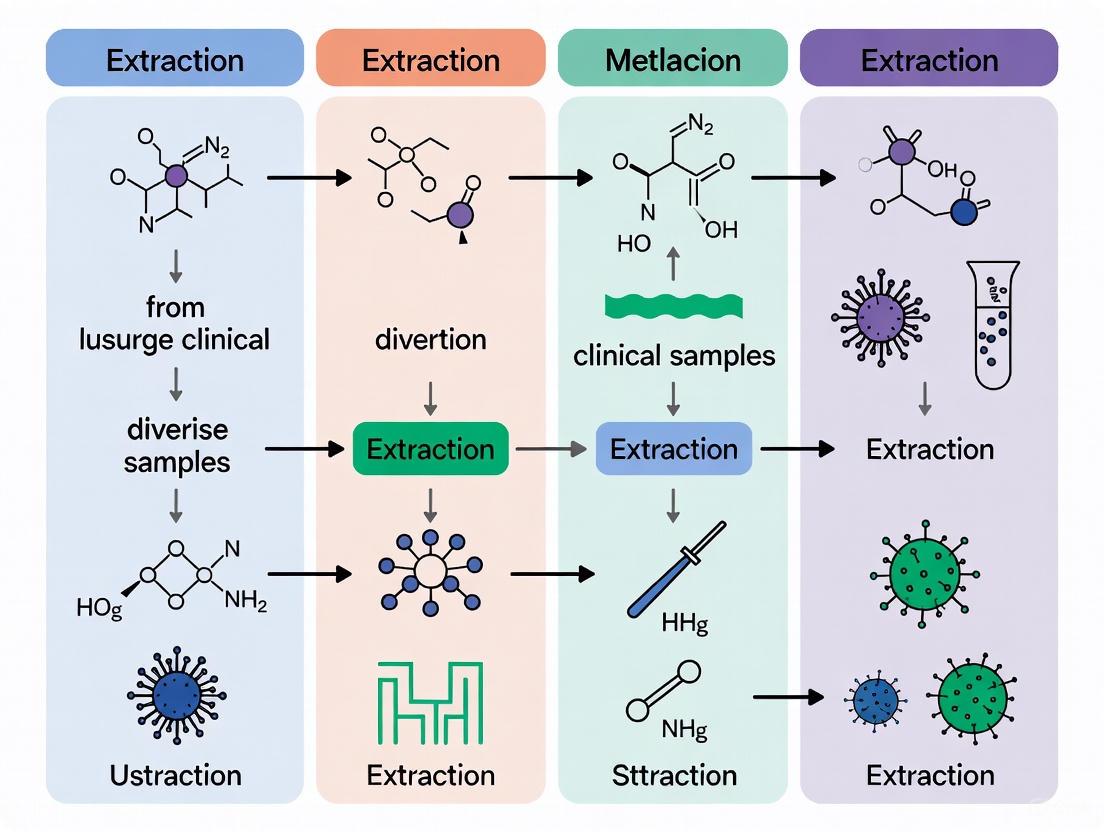

Extraction Method Selection Workflow

Troubleshooting Common Extraction Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my extraction yield vary significantly between sample batches?

- Potential Causes: Inconsistent cell disruption efficiency, variable sample matrix effects, or degradation during storage.

- Solutions:

- Pre-determine and validate cell disruption efficiency thresholds. Studies show that at disruption efficiencies >90%, lipids can be extracted at high yields, whereas at lower efficiencies, considerable amounts of analytes remain inaccessible regardless of solvents used [2].

- Implement strict pre-analytical sample handling protocols, especially for RNA extraction where quick cooling and RNase-free conditions are essential [3].

- Use internal standards to correct for recovery variations.

Q2: How can I minimize degradation of heat-sensitive compounds during extraction?

- Solutions:

- Replace conventional Soxhlet extraction with ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), which utilizes acoustic cavitation at lower temperatures, enabling more efficient recovery of thermolabile phytochemicals [4].

- Consider enzyme-assisted extraction methods that selectively break down cell walls without excessive heat application [4].

- Optimize extraction duration and temperature parameters based on stability studies of your target analytes.

Q3: What strategies can improve DNA recovery from challenging, degraded samples?

- Solutions:

- For highly degraded DNA, implement extraction protocols specifically designed for short fragment recovery, such as the Dabney method, which successfully recovers DNA fragments down to 35 bp [5].

- When possible, increase starting material through parallel processing (e.g., pooling lysates from multiple 50 mg aliquots) to achieve almost linear DNA gain [5].

- Avoid vortexing potentially degraded samples; instead, gently homogenize by slowly turning tubes upside down to preserve DNA integrity [3].

Q4: How can I address ion suppression in LC-MS/MS analysis following extraction?

- Solutions:

- Optimize sample preparation to remove endogenous interferences using techniques like solid-phase extraction (SPE) or protein precipitation [6].

- Employ chromatographic approaches to separate analytes from matrix components, including microflow LC to improve peak resolution [6].

- Implement rigorous selection of precursor and product ions in MRM for maximized signal-to-noise ratios [6].

Method-Specific Protocols and Optimization

Protocol: Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) for Clinical Samples

Applications: Isolating drug metabolites from plasma, preparing urine and serum samples for drug screening, capturing mycotoxins from food matrices [1].

Detailed Methodology:

- Conditioning: Condition the solid phase (cartridge, disk, or plate) with appropriate solvents to prepare the sorbent surface.

- Loading: Load the liquid sample onto the conditioned solid phase.

- Washing: Wash away unwanted impurities and matrix components with optimized wash buffers.

- Elution: Elute the target compounds with an appropriate solvent that ensures high recovery without co-eluting interferents [1].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If recovery is low, reevaluate sorbent selection and conditioning steps, which are critical to success [1].

- For complex biological matrices, consider incorporating additional wash steps or adjusting solvent polarity gradually.

Protocol: Mechanical Cell Disruption for Intracellular Analytes

Applications: Extracting intracellular lipids from oleaginous yeasts, recovering microbial metabolites, preparing tissue homogenates [2].

Detailed Methodology for Yeast Lipid Extraction:

- Cell Disruption: Implement high-pressure homogenization (HPH) or bead milling for efficient disruption. Studies demonstrate HPH achieves 95% cell disruption efficiency for Saitozyma podzolica [2].

- Solvent Extraction: Combine disrupted cell material with ethanol-hexane extraction system (commonly used for algal lipids) for efficient lipid recovery [2].

- Separation: Separate organic phase containing lipids from cellular debris.

Performance Comparison: Table 2: Efficiency of Cell Disruption Methods for Lipid Recovery from Yeasts

| Disruption Method | Cell Disruption Efficiency | Extraction System | Lipid Yield (% cell dry weight) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Pressure Homogenization (HPH) | 95% (S. podzolica) | Ethanol-Hexane | 46.9 ± 4.4% |

| Bead Milling | 74% (A. porosum) | Direct Acidic Transesterification | 27.2 ± 0.5% |

| Ultrasonification | Lower efficiency | Folch Method | 2.7 times lower than HPH + Ethanol-Hexane |

Protocol: Nucleic Acid Extraction from Challenging Samples

Applications: DNA/RNA extraction from forensic samples, ancient bones, clinical biopsies, and environmental samples [5] [3].

Detailed Methodology for Bone DNA Extraction:

- Sample Preparation: Mechanically clean bone surfaces, cut into small pieces, and mill into powder using a ball mill [5].

- Decalcification: Incubate bone powder in lysis buffer (e.g., 0.45 M EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20) with proteinase K at 37-56°C for 1-2 days [5].

- Binding: Combine lysate with binding buffer (5 M guanidine hydrochloride, 40% isopropanol, 0.05% Tween 20) and sodium acetate [5].

- Purification: Transfer solution through silica membrane column, wash with ethanol-based buffer, and elute DNA in low-salt buffer [5].

Performance Optimization:

- For highly degraded samples, the Dabney protocol shows superior recovery of short DNA fragments compared to traditional methods like Loreille [5].

- For better-preserved samples with sufficient tissue, the Loreille protocol provides higher total DNA yield [5].

Advanced Applications and Integration with Downstream Analysis

Enhancing LC-MS/MS Performance Through Optimized Extraction

Problem: Ion suppression reduces analyte signal intensity and compromises quantification accuracy in LC-MS/MS [6].

Integrated Solution Strategy:

- Extraction Optimization: Implement SPE to remove endogenous interferences prior to analysis [6].

- Chromatographic Separation: Employ advanced separation techniques including microflow LC to improve peak resolution and reduce matrix effects [6].

- Instrument Maintenance: Regular cleaning of LC-MS/MS instrumentation interfaces prevents contamination buildup that exacerbates suppression [6].

Extraction for Advanced Sequencing Applications

Problem: Inconsistent nucleic acid quality and purity compromise next-generation sequencing results [3].

Quality Control Measures:

- For RNA extraction intended for transcriptomic studies, ensure quick processing and cooling to preserve mRNA integrity, especially for low-frequency transcripts [3].

- Use talc-free gloves to prevent inhibition of downstream enzymatic reactions including PCR and reverse transcription [3].

- Assess RNA integrity numbers (RIN) prior to library preparation to ensure sequence representation accuracy.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Extraction Methodologies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Membranes/Columns | Nucleic acid binding and purification | Column-based DNA/RNA extraction kits [3] |

| Magnetic Beads | High-throughput nucleic acid purification | Automated DNA extraction for ASFV detection [7] |

| Proteinase K | Enzymatic degradation of proteins | Cell lysis in DNA extraction from challenging samples [5] |

| Guanidine Salts | Chaotropic agent, denatures proteins | Binding buffer in nucleic acid extraction [5] [3] |

| Phenol-Chloroform | Protein denaturation, phase separation | Traditional nucleic acid purification [3] |

| Specialized Sorbents | Selective analyte retention | SPE cartridges for specific compound classes [1] |

The critical impact of extraction choice on downstream analysis success cannot be overstated. Method selection must be guided by sample matrix characteristics, target analyte properties, and the specific requirements of subsequent analytical techniques. Systematic optimization and troubleshooting of extraction protocols significantly enhance data quality, reproducibility, and overall research outcomes. As extraction technologies continue to evolve, particularly through hybrid approaches that combine multiple techniques, researchers can achieve unprecedented levels of sensitivity and specificity in their analytical workflows.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single biggest challenge when analyzing diverse clinical samples? The primary challenge is the sample matrix effect, where components in the sample other than your target analyte interfere with detection and quantification. This includes endogenous compounds like proteins, lipids, salts, and phospholipids that can co-extract with your analytes. These matrix components can suppress or enhance the detector's response to your analyte, leading to inaccurate quantification [8]. The complexity and composition of these interfering materials vary significantly between sample types, such as blood, urine, and tissues, making it difficult to apply a universal sample preparation method [9].

Q2: Why does my method work well with blood but fail when I switch to urine samples? Different biological matrices have unique physical properties and compositions. Blood and its cell-free products (like plasma and serum) contain high levels of proteins and lipids, often requiring robust protein precipitation steps [10]. Urine, while less complex, has a high salt content and can contain metabolites that interfere with analysis. The failure likely stems from your current sample preparation method not effectively removing the specific interferents present in urine. Method optimization for the new matrix is essential, potentially requiring different clean-up techniques such as solid-phase extraction (SPE) or specific enzymatic hydrolysis steps for urine [9].

Q3: How can I improve the detection of low-abundance analytes in complex tissues? Improving detection for low-abundance analytes involves two key strategies:

- Effective Clean-up: Use specialized clean-up procedures to remove the sample matrix. Techniques like solid-phase extraction (SPE) or phospholipid removal products can provide a cleaner sample, concentrating the analyte and removing contaminants that suppress the signal [11] [10].

- Selective Enrichment: For targeted analysis, employ enrichment strategies. Immunoaffinity purification or nanoparticle-based enrichment can selectively isolate your target analytes from the complex tissue background, significantly improving the signal-to-noise ratio [10].

Q4: What is the best DNA extraction method for getting unbiased results from microbial communities in different samples? No single method is universally "best," but the choice significantly impacts your results. Studies comparing kits across different sample matrices (soil, feces, invertebrates) find that the extraction kit can drastically alter microbial diversity estimates and the observed abundance of specific taxa [12]. For instance, the MACHEREY–NAGEL NucleoSpin Soil kit has been associated with the highest alpha diversity estimates in a multi-matrix study. The key is to choose a kit whose lysis efficiency (e.g., use of lysozyme for Gram-positive bacteria) is appropriate for your target organisms and to use the same kit for all samples within a study to ensure comparability [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Recovery or Low Yield

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low DNA yield from microbial samples. | Inefficient cell lysis, especially for organisms with tough cell walls (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, spores). | Incorporate a mechanical lysis step (e.g., bead beating) or use a specialized enzymatic lysis cocktail (e.g., MetaPolyzyme) to improve wall degradation [13] [12]. |

| Low analyte recovery from solid tissues. | Incomplete homogenization or inefficient extraction from the tissue matrix. | Optimize homogenization protocol (e.g., using a bead beater). Ensure the extraction solvent is compatible with the tissue type and analyte. Consider a more vigorous digestion or extraction step [14]. |

| Low recovery of proteinaceous analytes. | Protein aggregation during freeze-thaw cycles or adsorption to vial walls. | Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Use appropriate buffers and vial materials. Add detergents or other stabilizing agents to the buffer if compatible with downstream analysis [8] [10]. |

Matrix Effects & Signal Suppression in LC-MS/MS

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent calibration curves and inaccurate quantification. | Co-eluting matrix components suppressing or enhancing ionization in the mass spectrometer [8]. | 1. Improve Chromatography: Modify the LC method to separate the analyte from the interfering compounds.2. Use Internal Standards: Employ a stable isotope-labeled internal standard (SIL-IS). It co-elutes with the analyte and compensates for ionization suppression [8].3. Enhanced Clean-up: Use a more selective sample preparation method, such as SPE or phospholipid removal products [11]. |

| High background noise and reduced signal-to-noise ratio. | Incomplete removal of phospholipids, salts, or other endogenous compounds during sample prep. | Incorporate a dedicated phospholipid removal step (e.g., using products like Phree) [11]. Ensure proper protein precipitation and washing steps. |

Inaccurate Microbiota Profiles

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Under-representation of Gram-positive bacteria in metagenomic studies. | DNA extraction protocol is ineffective at lysing tough Gram-positive cell walls. | Use a kit that includes a bead-beating step or add a lysozyme incubation to the protocol. Comparative studies show kits with bead beating provide more balanced representation [12]. |

| Excessive DNA fragmentation in long-read sequencing. | Overly harsh lysis methods (e.g., vigorous bead beating) shearing DNA. | For long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., Nanopore), consider gentler enzymatic lysis methods, which have been shown to produce longer DNA fragments and more accurate microbial profiles [13]. |

| Inconsistent results between different sample types in the same study. | Using different DNA extraction kits optimized for specific matrices, introducing technical bias. | Select a single, well-validated DNA extraction kit that provides the most consistent and comprehensive lysis across all sample types in your study, such as the NucleoSpin Soil kit for ecosystem studies [12]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Comparison of DNA Extraction Methods on Different Sample Matrices

A 2024 study directly compared five commercial DNA extraction kits across a range of terrestrial ecosystem samples, providing quantitative data on their performance [12]. The findings are highly relevant for choosing a method in clinical and environmental research.

- Objective: To identify the most suitable DNA extraction kit for microbiota studies across multiple sample matrices.

- Kits Tested: DNeasy Blood & Tissue (QBT), QIAamp DNA Micro (QMC), NucleoSpin Soil (MNS), DNeasy PowerSoil Pro (QPS), and QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini (QST).

- Sample Types: Bulk soil, rhizosphere soil, invertebrate samples, and mammalian feces.

- Key Metrics: DNA concentration, purity (260/280 and 260/230 ratios), extraction efficiency of Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative bacteria (using a mock community), and resulting microbial diversity estimates (alpha and beta diversity).

Table 1: Performance of DNA Extraction Kits Across Different Sample Types [12]

| Kit Name | Key Lysis Feature | Best For (Sample Type) | Gram+/Gram- Lysis Efficiency (Ratio)* | Impact on Alpha Diversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NucleoSpin Soil (MNS) | Bead beating | All sample types (most consistent) | 1.35 ± 0.19 (High) | Highest diversity estimates |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Pro (QPS) | Bead beating | Soil, Feces | 1.31 ± 0.25 (High) | High |

| QIAamp Fast DNA Stool (QST) | Chemical & enzymatic | Mammalian feces | 1.39 ± 0.19 (High) | Variable by sample type |

| QIAamp DNA Micro (QMC) | Optimized for small samples | Invertebrates, low biomass | 1.40 ± 0.15 (High) | Variable by sample type |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue (QBT) | Chemical/Enzymatic (gentle) | Pure cultures, blood | 0.71 ± 0.08 (Low) | Lowest diversity estimates |

Note: A higher ratio indicates more efficient lysis of Gram-positive bacteria. The expected ratio based on the mock community was 0.43. All kits over-represented the Gram-positive bacterium, but QBT was the least efficient.

Protocol: Enzymatic vs. Mechanical Lysis for Long-Read Metagenomic Sequencing

A 2022 study compared lysis methods for pathogen identification in urine samples using nanopore sequencing [13]. The protocol below is adapted from their work.

- Objective: To obtain high-integrity, long-fragment DNA from microbial communities in urine for accurate long-read sequencing.

- Sample: Urine samples from patients with UTIs.

- Methods Compared: Method 1 (Control, no pre-lysis), Method 2 (Mechanical lysis with bead beating), Method 3 (Enzymatic lysis with MetaPolyzyme).

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge urine to pellet microbes. Discard supernatant and resuspend pellet.

- Lysis Step:

- Method 2 (Mechanical): Transfer sample to a tube with glass beads and buffer. Vortex at maximum speed for 10 minutes.

- Method 3 (Enzymatic): Add lytic enzyme solution and MetaPolyzyme to the sample. Incubate at 37°C with shaking for 1 hour.

- DNA Extraction: For all methods, perform DNA extraction from the lysed sample using a standard pathogen kit (e.g., IndiSpin Pathogen Kit).

- Library Prep & Sequencing: Prepare library using a PCR barcoding kit and sequence on a long-read platform (e.g., MinION).

Conclusion: The enzymatic-based method (Method 3) increased the average read length by a median of 2.1-fold and provided fully consistent diagnostic results with clinical culture, outperforming mechanical lysis for this application [13].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Sample Preparation Decision Pathway

This diagram outlines a logical workflow for developing a sample preparation strategy for complex matrices.

Matrix Effect Identification and Mitigation

This diagram illustrates the sources and solutions for matrix effects in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Handling Complex Sample Matrices

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MetaPolyzyme | An enzymatic cocktail for gentle microbial cell wall lysis. Ideal for long-read sequencing as it preserves DNA integrity [13]. | More specific and gentler than mechanical lysis. Increases microbial read length and improves diagnosis accuracy for pathogens. |

| Phospholipid Removal Plates (e.g., Phree) | Selectively removes phospholipids from sample extracts, a major source of ion suppression in LC-MS/MS [11]. | Can be used as a standalone clean-up step or before SPE. Crucial for obtaining clean baselines and accurate quantification. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-IS) | A chemically identical version of the analyte with heavy isotopes (e.g., ¹³C, ²H). Added to correct for analyte loss and matrix effects [8]. | Considered the gold standard for mitigating matrix effects in quantitative mass spectrometry. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | A versatile clean-up and concentration tool. Binds analytes while washing away impurities [9] [10]. | Provides the cleanest samples. Choice of sorbent (C18, ion-exchange, mixed-mode) depends on analyte chemistry. |

| β-Glucuronidase/Sulfatase Enzyme | Hydrolyzes phase II metabolite conjugates (glucuronides and sulfates) in urine and other biofluids to measure total analyte concentration [9]. | Essential for biomonitoring studies of compounds like bisphenols. Incubation time and buffer pH must be optimized. |

| Bead Beating Tubes | Used for mechanical lysis of tough cells (e.g., Gram-positive bacteria, spores) in microbial community DNA studies [12]. | Essential for unbiased representation of all community members. Harsh beating can fragment DNA, which may be undesirable for long-read sequencing. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problem 1: Low DNA/RNA Yield after Lysis

Problem Description: Inadequate recovery of nucleic acids post-lysis, leading to insufficient material for downstream applications like PCR or sequencing.

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Cell Disruption | Lysis method is insufficient for the sample matrix (e.g., using chemical lysis alone for gram-positive bacteria or plant spores). | Implement a combined approach: mechanical homogenization (e.g., bead beating) followed by chemical lysis [15]. |

| Enzymatic Degradation | Endogenous nucleases become active during lysis, degrading the target nucleic acids. | Add chelating agents (e.g., EDTA) to inhibit nuclease activity and perform lysis on ice [15]. |

| Overly Aggressive Mechanical Lysis | Excessive mechanical force shears DNA into small fragments, reducing yield for long-fragment applications. | Optimize homogenization parameters (speed, time) and use specialized bead types to balance disruption with DNA preservation [15]. |

| Inefficient Lysis of Tough Samples | Samples like bone, spores, or certain tissues are inherently resistant to standard lysis protocols. | Use an initial demineralization step (e.g., with EDTA for bone) and powerful mechanical homogenization [15]. |

Common Problem 2: Formation of Emulsions during Liquid-Liquid Extraction

Problem Description: A stable emulsion forms between aqueous and organic phases, preventing clean phase separation and leading to analyte loss.

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Surfactant-like Compounds | Samples high in phospholipids, proteins, or fats (e.g., clinical samples from high-fat diets) act as surfactants [16]. | Gently swirl the separatory funnel instead of shaking it vigorously during mixing to prevent emulsion formation [16]. |

| High Sample Viscosity | Viscous samples can stabilize the interface between the two phases. | Dilute the sample with a matrix-compatible solvent to lower viscosity before extraction [17]. |

| N/A | Emulsion has already formed. | "Salt out" by adding brine to increase the ionic strength of the aqueous layer, disrupting the emulsion [16]. |

| N/A | Emulsion persists. | Centrifuge the mixture or filter through a glass wool plug or phase separation filter paper to isolate the phases [16]. |

Common Problem 3: Poor Reproducibility in Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE)

Problem Description: High variability in analyte recovery between replicate extractions.

| Potential Cause | Explanation | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Flow Rates | Variable flow during sample loading or elution affects binding equilibrium and elution efficiency. | Use a controlled manifold or pump to maintain a consistent, optimal flow rate (typically below 5 mL/min) [17]. |

| Dried-Out Sorbent Bed | The SPE cartridge bed dried out before sample application, reducing retention efficiency. | Re-activate and re-equilibrate the cartridge with solvent before loading the sample to ensure the bed is fully wetted [17]. |

| Overloaded Cartridge | The sample contains more analyte or interferents than the sorbent's binding capacity can handle. | Reduce the sample load amount or switch to an SPE cartridge with a higher capacity [17]. |

| Overly Strong Wash Solvent | The wash solvent is too strong, prematurely eluting a portion of the analyte during the washing step. | Weaken the wash solvent strength and control the flow rate during the wash step (~1-2 mL/min) [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How does the choice of lysis method impact downstream bioactivity analysis?

The lysis method directly determines the integrity, yield, and profile of extracted bioactive compounds. Conventional methods like Soxhlet extraction use prolonged heat, which can degrade heat-sensitive compounds like polyphenols and flavonoids, reducing their bioactivity [4]. Advanced physical methods like Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) use acoustic cavitation at lower temperatures to disrupt cell walls more efficiently, leading to higher yields of intact bioactives and superior antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity in the final extract [4] [18]. The preservation of these compound structures is essential for their pharmacological activity, such as inhibiting pro-inflammatory pathways like NF-κB [4].

FAQ 2: How do I balance effective cell disruption with the preservation of nucleic acid integrity?

Achieving this balance is critical. Excessive mechanical force can cause DNA shearing and fragmentation, making it unsuitable for long-read sequencing [15]. The key is precise control over homogenization parameters. For example, using an instrument like the Bead Ruptor Elite allows researchers to optimize speed, cycle duration, and bead type [15]. Temperature control is also vital, as excessive heat during homogenization can accelerate DNA degradation via hydrolysis and oxidation. Using instruments with cooling functions protects DNA integrity [15]. A combined approach using gentle enzymatic pre-treatment (e.g., lysozyme for bacteria) followed by controlled mechanical homogenization can also maximize yield while minimizing damage.

FAQ 3: What are the key considerations for scaling up a lysis protocol from research to clinical diagnostics?

Scalability requires a focus on robustness, cost, and practicality, especially in low-resource settings. While spin-column and magnetic bead DNA extraction methods yield high purity and are suitable for labs, they can be equipment-intensive [19]. For in-field diagnostics, simpler methods like the Hotshot method may be more practical and cost-effective, despite potentially lower sensitivity [19]. The method must also handle real-world sample variability. For instance, an LLE protocol developed for animal models on controlled diets may fail with human samples due to emulsion formation from high-fat diets; thus, methods must be validated with diverse clinical matrices [16]. Standardization and quality control at each step are essential for transferability.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) for Bioactive Compounds from Plant Material

Application: Efficient extraction of heat-sensitive phytochemicals (e.g., resveratrol, flavonoids) for pharmaceutical or nutraceutical research [4] [18].

- Sample Preparation: Dry and finely grind the plant material (e.g., vine shoots, citrus peels) to increase the surface area for solvent contact [4].

- Solvent Selection: Prepare a hydroalcoholic solvent (e.g., 59% ethanol in water). The polarity of the solvent should be optimized for the target compounds [18].

- Extraction Setup: Mix the plant material with the solvent at a defined liquid-to-solid ratio (e.g., 25:1 mL/g) in a suitable vessel [18].

- Ultrasound Treatment: Place the vessel in an ultrasonic bath or under an ultrasonic probe. Process at a controlled amplitude (e.g., 62%) and temperature (e.g., 55°C) for a set duration (e.g., 6 minutes) [18].

- Separation and Analysis: Separate the supernatant from the plant residue by filtration or centrifugation. The extract can be concentrated and analyzed for its phytochemical content and bioactivity (e.g., antioxidant capacity) [4].

Protocol 2: Optimized DNA Extraction from Challenging Clinical Samples (e.g., Bone, Stool)

Application: Recovering high-quality DNA from difficult-to-lyse samples for metagenomic or forensic analysis [15].

- Demineralization (for calcified samples like bone): Incubate the powdered bone sample in a solution containing EDTA. EDTA chelates calcium, softening the mineral matrix [15].

- Mechanical Homogenization: Transfer the sample to a tube containing specialized beads (e.g., ceramic or stainless steel). Use a bead homogenizer (e.g., Bead Ruptor Elite) with optimized speed and cycle duration settings to physically disrupt the tissue and cells while minimizing heat generation [15].

- Chemical Lysis: Following mechanical disruption, add a lysis buffer containing detergents (e.g., SDS), salt, and a buffering agent to dissolve cellular membranes and release DNA. Include EDTA and/or nuclease inhibitors to protect the released DNA from enzymatic degradation [15].

- DNA Purification: Purify the DNA from the lysate using a standard method like spin-columns or magnetic beads to remove proteins, salts, and other contaminants [19].

- Quality Control: Assess the DNA yield, purity (via spectrophotometry), and integrity (via fragment analysis) to ensure it is suitable for downstream applications like sequencing [15].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Lysis & Extraction | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | A chelating agent that binds metal ions. Used to demineralize tough samples like bone and to inhibit metal-dependent nucleases, protecting DNA/RNA from enzymatic degradation [15]. | High concentrations or carry-over can inhibit downstream PCR [15]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Bio-based, biodegradable solvents considered environmentally friendly. Used as a green alternative to traditional organic solvents for extracting bioactive compounds like resveratrol [18]. | Solvent properties (viscosity, polarity) must be matched to the target analyte and biomass [18]. |

| Ceramic or Stainless Steel Beads | Used in bead homogenization for mechanical cell disruption. Effective for tough samples like bacteria, spores, and fibrous tissues [15]. | Bead size and material must be optimized; overly aggressive beating can cause excessive DNA shearing [15]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease. Used in enzymatic lysis to digest proteins and degrade nucleases, facilitating the release of intact nucleic acids [15]. | Requires incubation at an optimal temperature (often 55-65°C) for a specific duration to be effective. |

| Methanol, Ethanol, Water | Polar solvents used in solvent-based extraction. Effective for extracting hydrophilic bioactive compounds like polyphenols, flavonoids, and glycosides from plant materials [4]. | Solvent polarity should be matched to the target compound's hydrophilicity/lipophilicity for optimal yield [4]. |

The efficacy of natural product extraction from clinical and research samples is paramount in drug development. The process is a critical bridge between raw biological material and the identification of novel therapeutic compounds. The yield and purity of the resulting extracts are not arbitrary; they are directly controlled by a set of key operational parameters. Solvent selection, pH, temperature, and extraction duration form the cornerstone of an efficient extraction protocol. Optimizing these factors is essential to maximize the recovery of target bioactive compounds while minimizing co-extraction of impurities, ensuring the integrity of downstream analyses and accelerating the drug discovery pipeline. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and methodologies to address common challenges in extraction workflows.

Parameter Optimization Tables

The following tables summarize the quantitative impact of key parameters on extraction yield and quality, serving as a reference for initial experimental design.

Table 1: Optimization of Extraction Solvents for Different Compound Classes

| Compound Class | Recommended Solvents (in order of efficiency) | Typical Yield Range | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Phenolic Content (TPC) | Methanol > Acetone > Ethanol > Water [20] | 2.9 - 9.7 mg GAE/g DW [20] | Methanol is generally most efficient, but optimal solvent depends on plant material. [20] |

| Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) | Ethanol > Methanol > Acetone > Water [20] | 0.9 - 5.9 mg QE/g DW [20] | For seed extracts, ethanol was superior for both TPC and TFC. [20] |

| Total Tannin Content (TTC) | Acetone > Methanol > Ethanol > Water [20] | 1.5 - 4.3 mg TA/g DW [20] | Aqueous acetone is particularly effective for higher molecular weight flavonoids. [20] |

| Cinnamaldehyde (Volatile) | Freeze-Pressure Extraction > Vacuum Extraction > Heat Reflux [21] | 348.53 - 370.20 µg/g [21] | Novel FE technology significantly increased yield of volatile compounds compared to traditional methods. [21] |

Table 2: Effect of Temperature and Time on Yield and Quality

| Extraction Method / Material | Temperature Effect | Time Effect | Quality Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw Press Hemp Seed Oil [22] | Yield increased with temperature up to 100°C (21.82% yield). | N/A (Continuous process) | Higher temperatures (>100°C) increased peroxide value (indicates oxidation) and degraded chlorophyll. [22] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE), Inonotus hispidus [23] | Controlled via ice bath (40-50°C) to prevent thermodegradation. [23] | Optimized at 20 minutes. [23] | Shorter, controlled-time UAE preserved antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds. [23] |

| Maceration, Chokeberry Fruit [24] | Room Temperature | Long extraction time (several hours to days). [24] | Simple but low efficiency; suitable for thermolabile compounds. [24] |

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

FAQ 1: My extraction yield is low, even though I am using a recommended solvent. What could be the issue?

- Problem: Low extraction yield.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Cell Wall Disruption. The solvent cannot access intracellular compounds.

- Solution: Incorporate a mechanical pre-treatment or use an advanced extraction technique. Physical pretreatment like freeze-pressure puffing (FE) creates larger pores and expands the surface area of the plant matrix, facilitating more effective compound release [21]. Alternatively, Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) uses acoustic cavitation to disrupt cell walls, significantly improving efficiency over simple maceration [23].

- Cause 2: Incorrect Particle Size.

- Solution: Optimize the particle size of your raw material. Generally, a finer particle size enhances solvent penetration and solute diffusion. However, too fine a powder can lead to excessive absorption of the solute and difficult filtration [24].

- Cause 3: Solvent-to-Solid Ratio is Too Low.

- Solution: Increase the volume of solvent relative to the solid material. A greater solvent-to-solid ratio generally increases the extraction yield by driving the concentration gradient, though an excessively high ratio is wasteful and requires longer concentration times [24].

- Cause 1: Inadequate Cell Wall Disruption. The solvent cannot access intracellular compounds.

FAQ 2: My extract shows signs of compound degradation or unwanted transformation. How can I prevent this?

- Problem: Degradation of heat-sensitive or labile bioactive compounds.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Excessive Extraction Temperature.

- Solution: Lower the extraction temperature and avoid prolonged heating. For thermolabile compounds like flavonoids and polyphenols, modern techniques like UAE and MAE can achieve high efficiency at lower temperatures or in shorter times [25]. The novel Freeze-Pressure regulated Extraction (FE) operates at low temperatures, effectively preserving volatile and heat-sensitive compounds like cinnamaldehyde [21].

- Cause 2: Overly Long Extraction Duration.

- Solution: Optimize and shorten the extraction time. For example, in UAE, 20 minutes can be sufficient to maximize phenolic yield and antioxidant activity, avoiding the long durations of maceration that might promote degradation [23]. The equilibrium of the solute is reached in a certain time, and increasing time beyond this point will not improve yield and may harm quality [24].

- Cause 3: Unsuitable pH.

- Solution: The stability of many bioactive compounds is pH-dependent. For instance, during the decoction of Danggui Buxue Tang, the hydrolysis of flavonoid glycosides was strongly affected by pH [24]. Buffering the extraction solvent to a pH that stabilizes your target compound may be necessary.

- Cause 1: Excessive Extraction Temperature.

FAQ 3: How can I improve the selectivity of my extraction to target a specific compound class and reduce impurities?

- Problem: Poor extract purity and selectivity.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Solvent Polarity Does Not Match Target Compound.

- Solution: Apply the "like dissolves like" principle. Use solvents with a polarity value near to the polarity of your target solute [24]. For example, polar solvents (e.g., ethanol, water) favor hydrophilic compounds (e.g., flavonoids, tannins), while non-polar solvents (e.g., hexane) are better for lipophilic bioactives (e.g., terpenoids, carotenoids) [25].

- Cause 2: Co-extraction of Polysaccharides and Proteins.

- Solution: Consider Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE). Enzymes can selectively break down plant cell walls (cellulase, pectinase) or unwanted macromolecules, facilitating the release of intracellular compounds while minimizing co-extraction of impurities, thereby increasing the purity and bioavailability of the target compounds [25].

- Cause 1: Solvent Polarity Does Not Match Target Compound.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) for Phenolic Compounds

This protocol is adapted from a study optimizing phenolic extraction from Inonotus hispidus mushroom, demonstrating a modern, efficient approach [23].

Objective: To maximize the yield of total phenolic content (TPC) and antioxidant activity from a biological sample using UAE.

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Hielscher ultrasonic processor (or equivalent) with a sonotrode [23].

- Centrifuge capable of 4500× g and 4°C operation [23].

- Solvents: 40% (v/v) analytical-grade ethanol in ultrapure water [23].

- Chemicals: Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, gallic acid, DPPH, Trolox, TPTZ for antioxidant assays (Sigma-Aldrich) [23].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cut the raw biological material into small pieces, dry at 40°C, and grind to a fine powder. Ensure consistent particle size for reproducibility [23].

- Weighing: Accurately weigh 1.0 g of the dried powder into a suitable extraction vessel [23].

- Solvent Addition: Add the extraction solvent (40% ethanol) at a pre-optimized solvent-to-solid ratio of 75 mL/g [23].

- Sonication: Immerse the sonotrode and operate the ultrasonic processor in a pulsed mode (e.g., 5 s on, 5 s off) for a total extraction time of 20 minutes. Place the sample in an ice bath to maintain the temperature between 40-50°C and prevent thermodegradation of phenolic compounds [23].

- Separation: After sonication, centrifuge the mixture at 4500× g for 20 minutes at 4°C to separate the solid residue from the liquid extract [23].

- Filtration: Filter the supernatant (liquid extract) using Whatman No. 4 filter paper or a similar grade [23].

- Analysis and Storage: The filtrate is the final extract. Analyze immediately for TPC and antioxidant activity (DPPH, FRAP) or store at -20°C until analysis [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol and Ethanol | Polar solvents for extracting hydrophilic compounds like phenolics and flavonoids. [24] [25] | Universal solvents in phytochemical investigation; methanol often yields highest TPC. [24] [20] |

| Acetone (Aqueous) | Effective for a broad range of polyphenols, especially higher molecular weight flavonoids. [20] | Superior to alcohol for extracting tannins from leaves. [20] |

| Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent | Used in spectrophotometric assay to quantify total phenolic content (TPC). [23] | Determining the total phenolic yield in an optimized UAE extract. [23] |

| DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) | A stable free radical used to measure the free radical scavenging (antioxidant) capacity of an extract. [23] | Evaluating the antioxidant activity of the extracted compounds in a standardized assay. [23] |

| Hispidin Standard | Pure compound used as an external standard for HPLC quantification. [23] | Identifying and quantifying the main polyphenol in Inonotus hispidus extracts via HPLC. [23] |

| Enzyme Cocktails (e.g., Cellulase, Pectinase) | Selectively hydrolyze plant cell wall components to improve compound release and yield. [25] | Enzyme-assisted extraction to enhance the yield of intracellular compounds from tough plant matrices. [25] |

Advanced Hybrid Workflow for Temperature-Sensitive Compounds

For challenging extractions involving highly volatile or thermolabile compounds, a hybrid approach combining physical pretreatment with mild extraction is superior.

Workflow: Freeze-Pressure Regulated Extraction (FE)

Description: This novel FE technique begins with a deep freeze (-50°C) to lock the sample structure. A subsequent sublimation/puffing step at low temperature and pressure (-25°C, 0 MPa) physically disrupts the cell walls, creating larger pores and an expanded surface area without using heat. This is followed by a vacuum extraction at a lower boiling point (80°C) to prevent degradation. This workflow has been proven to increase the yield of volatile compounds like cinnamaldehyde while better preserving the pharmacological activity of the extract compared to traditional heat reflux extraction [21].

A Practical Guide to Extraction Techniques for Specific Clinical Matrices

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for conventional extraction methods within clinical research. The following questions and answers address common issues to ensure experimental reproducibility and integrity.

Soxhlet Extraction

Q: My Soxhlet extraction yield is lower than expected. What could be the cause?

- A: Low yields can result from several factors. First, ensure the solute's solubility in your chosen solvent; polar solvents like methanol are better for hydrophilic compounds, while non-polar solvents like hexane suit lipophilic compounds [24]. Second, check that your sample is ground to a fine, uniform particle size to maximize surface area for solvent penetration, but avoid excessive fineness that can lead to poor solvent flow or clogging [24]. Finally, verify the extraction time; while Soxhlet is a continuous process, it requires a long extraction time to complete multiple cycles, and terminating the process too early will reduce yield [24].

Q: I am concerned about the degradation of heat-sensitive compounds during Soxhlet extraction. How can this be mitigated?

- A: This is a known limitation of conventional Soxhlet extraction, as it involves prolonged heating at the solvent's boiling point [4]. For thermolabile compounds like certain flavonoids and polyphenols, consider alternative methods such as maceration or modern techniques like Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), which can achieve similar yields at lower temperatures [24]. If Soxhlet is necessary, using a solvent with a lower boiling point can reduce thermal stress.

Maceration

Q: The extraction efficiency of my maceration process is inconsistent. How can I improve it?

- A: To improve maceration efficiency and consistency, optimize these key parameters [24]:

- Solvent Selection: Use a solvent with a polarity value near that of your target solute. Ethanol and methanol are universal solvents for phytochemical investigation.

- Particle Size: Reduce the solid raw material to a fine particle size (e.g., 0.75 mm has been used effectively) to enhance solvent penetration and solute diffusion.

- Solvent-to-Solid Ratio: Increase the ratio (e.g., 1:20 has been shown effective) to improve yield, but avoid excessive ratios that require long concentration times.

- Duration: Ensure the maceration lasts long enough to reach equilibrium between the solute inside and outside the solid material.

Q: Is maceration suitable for extracting all types of bioactive compounds from clinical samples?

- A: No, the suitability depends on the compound's stability and polarity. Maceration is a simple, effective method for phenolic compounds and works well for thermolabile components as it typically occurs at room temperature [24]. However, studies have shown it can have the lowest extraction efficiency for certain flavonoids compared to methods like microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) or ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) [24]. It is less efficient for compounds tightly bound within the matrix.

Phenol-Chloroform Extraction

Q: I see a thick, fuzzy interphase after centrifugation. How can I recover my nucleic acids without contamination?

- A: A thick interphase, often containing denatured proteins or DNA-protein complexes, can trap your target nucleic acids. To minimize this, ensure proteins are adequately denatured before extraction, for example, with SDS [26]. A highly effective solution is to use Phase Lock Gel, a proprietary gel that forms a physical barrier between the organic and aqueous phases during centrifugation, preventing the interphase from forming and allowing for clean recovery of the aqueous phase [26]. Gently mixing the phases without vortexing when isolating very large DNA can also reduce interphase material.

Q: I recovered no DNA after a phenol-chloroform extraction. What is the most likely mistake?

- A: The most common error is using acidic phenol (for RNA purification) instead of neutral/alkaline-buffered phenol (for DNA purification) [26]. At acidic pH, DNA denatures and partitions into the organic phase, leading to no recovery from the aqueous phase. Always verify the pH of your phenol. You can test it by diluting 1 ml of phenol with 9 ml of 45% methanol and measuring with a standard pH meter [26].

Q: My phenol solution has a pink discoloration. Is it still safe to use?

- A: No. A pink or brown color indicates oxidation of the phenol, which can produce compounds that cause nicking of DNA and degradation of RNA [26]. You should discard this phenol and use a fresh, non-oxidized batch. Most commercial phenol solutions include an antioxidant to prevent this, and they should be stored as recommended, protected from light.

Q: How do I effectively remove phenol contamination from my final aqueous nucleic acid sample?

- A: Perform a follow-up extraction with chloroform [26]. After the initial phenol or phenol-chloroform extraction, mix the recovered aqueous phase with a volume of pure chloroform. The phenol has a higher affinity for chloroform and will partition out of the aqueous phase. This step is crucial because residual phenol in your sample can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions.

The table below summarizes key operational parameters for the conventional extraction methods, based on the literature [24].

Table: Quantitative Comparison of Conventional Extraction Methods

| Method | Typical Solvents | Temperature | Pressure | Time | Volume of Solvent | Key Applications in Clinical Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soxhlet Extraction | Organic solvents (e.g., hexane, ethanol) | Under heat (at solvent's boiling point) | Atmospheric | Long | Moderate | Continuous extraction of lipids, phytochemicals from solid samples. |

| Maceration | Water, aqueous and non-aqueous solvents (e.g., ethanol, methanol) | Room Temperature | Atmospheric | Long (days) | Large | Extraction of thermolabile compounds, phenolic compounds, herbal extracts. |

| Phenol-Chloroform | Buffer-saturated phenol, chloroform, isoamyl alcohol | Room Temperature | Atmospheric | Moderate (minutes/hours) | Moderate | Isolation of pure, protein-free nucleic acids (DNA, RNA) from clinical samples. |

Experimental Workflow for Phenol-Chloroform Nucleic Acid Extraction

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for isolating nucleic acids using phenol-chloroform.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential reagents for the phenol-chloroform extraction protocol.

Table: Essential Reagents for Phenol-Chloroform Extraction

| Reagent | Function / Critical Property |

|---|---|

| Buffer-Saturated Phenol (Alkaline, pH ~7-8) | Denatures and solubilizes proteins; pH is critical for DNA partitioning into the aqueous phase. Acidic phenol is for RNA extraction. [26] |

| Chloroform | Enhances organic phase density to prevent inversion and assists in protein denaturation. Also used in a final step to remove residual phenol from the aqueous phase. [26] |

| Isoamyl Alcohol | Optional anti-foaming agent in the phenol-chloroform mixture. [26] |

| Phase Lock Gel | Proprietary inert gel that forms a barrier during centrifugation, eliminating the problematic interphase and improving nucleic acid recovery and purity. [26] |

| Proteinase K | Proteolytic enzyme used in pre-digestion to break down proteins and reduce interphase material. [26] |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Denaturant used to unfold proteins before extraction, making them more accessible for removal by the organic phase. [26] |

The efficacy of research on diverse clinical samples is fundamentally rooted in the initial sample preparation and extraction phase. Conventional extraction methods, often characterized by prolonged processing times, high solvent consumption, and significant thermal degradation, present a major bottleneck in drug development and scientific discovery. This technical support article details three advanced extraction techniques—Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE), Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE), and Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE)—that have emerged as powerful, efficient, and sustainable alternatives. Framed within the context of a broader thesis on extraction methods for diverse clinical samples, this guide provides troubleshooting support and detailed protocols to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals optimize their experimental workflows, enhance yield and bioactivity, and overcome common technical challenges.

Core Principles and Methodologies

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE)

Principle: UAE operates on the principle of acoustic cavitation. Ultrasonic waves passed through a solvent medium create cycles of compression and rarefaction, leading to the formation, growth, and violent collapse of microscopic bubbles. This collapse generates localized extremes of temperature and pressure, which disrupt cell walls, enhance solvent penetration, and accelerate the mass transfer of target compounds from the sample matrix into the solvent [27].

Detailed Protocol for Phenolic Compounds from Tamus communis Fruits:

- Sample Preparation: Plant material should be dried and ground to a homogeneous powder (e.g., 150-200 µm particle size) to maximize surface area.

- Solvent Selection: A hydroalcoholic mixture (e.g., 50-70% ethanol in water) is often optimal for phenolic compounds due to its ability to dissolve both polar and non-polar metabolites [28].

- Equipment Setup: Use an ultrasonic bath or an ultrasonic probe (sonotrode). Probe systems generally deliver higher energy density.

- Extraction Parameters:

- Solid-to-Solvent Ratio: 1:20 to 1:50 (g/mL) [27] [28].

- Ultrasonic Frequency: Typically 20-40 kHz.

- Temperature: Maintain between 40-60°C to prevent degradation of thermolabile compounds while improving extraction efficiency.

- Time: Extraction is typically rapid, often completed within 10-50 minutes [28].

- Work-up: The mixture is filtered to remove particulate matter. The filtrate is then concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator at a controlled temperature (e.g., 40°C). The dried extract can be stored at -20°C for further analysis.

Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE)

Principle: MAE utilizes electromagnetic radiation to heat the solvent and sample matrix directly. Microwaves cause dipole rotation and ionic conduction, leading to rapid and volumetric heating. This internal heating builds pressure within plant cells, rupturing them and efficiently releasing the bioactive compounds into the solvent [29].

Detailed Protocol for Phytochemicals from Piper betle L. Leaves:

- Sample Preparation: Dry leaves at 40°C, grind, and sieve to a consistent particle size (e.g., 150 µm) [29].

- Solvent Selection: Ethanol (95% v/v) is an effective green solvent for a wide range of phytochemicals [29].

- Equipment Setup: A closed-vessel microwave extraction system is recommended for elevated temperature extractions.

- Optimized Parameters (as per Response Surface Methodology):

- Microwave Power: 239.6 W

- Extraction Time: 1.58 minutes

- Solid-to-Solvent Ratio: 1:22 g/mL [29]

- Work-up: After irradiation, the vessel is cooled, and the extract is filtered. The solvent is removed via rotary evaporation to obtain a concentrated extract.

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE)

Principle: SFE uses a fluid above its critical temperature and pressure, where it exhibits unique properties: gas-like diffusivity and viscosity, combined with liquid-like density. This results in superior penetration into the sample matrix and high solvating power. Supercritical CO₂ (SC-CO₂) is the most widely used solvent due to its low critical point (31.1°C, 73.8 bar), non-toxicity, and inertness [30] [31].

Detailed Protocol for Tannin Recovery from Biomass:

- Sample Preparation: The biomass should be dried and ground to increase surface area. Moisture content can be optimized, as some studies report improved efficiency with certain moisture levels [30].

- Solvent System: Pure SC-CO₂ is suitable for non-polar compounds. For more polar molecules like tannins, a co-solvent (modifier) such as ethanol or methanol (e.g., 5-15%) is added to the system to increase polarity and improve yield [31].

- Equipment Setup: A typical SFE system consists of a CO₂ pump, a co-solvent pump, an extraction vessel housed in an oven, and a back-pressure regulator to separate the extract from the CO₂.

- Critical Parameters:

- Pressure: A key parameter affecting solvent density and solvating power. Often operated between 100-400 bar.

- Temperature: Affects both solute volatility and solvent density. Optimized based on the target compound.

- CO₂ Flow Rate: Influences the contact time and extraction kinetics.

- Work-up: The extract is collected in a separator where the pressure is reduced, causing CO₂ to revert to gas and leave the purified extract behind. The CO₂ can be recycled [30].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses specific, common issues encountered during experiments with these advanced extraction techniques.

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) FAQs

Q1: Our UAE extracts show low yield despite extended sonication time. What could be the cause?

- A: This is often due to inefficient cavitation. Check the following:

- Solvent Viscosity: Highly viscous solvents impede cavitation. Try diluting your solvent or choosing one with lower viscosity.

- Probe vs. Bath: An ultrasonic probe is more powerful than a bath for difficult matrices. Ensure the probe is properly immersed to prevent foaming.

- Temperature Control: Inadequate cooling can lead to solvent evaporation and degradation. Use a jacketed vessel with a circulator to maintain optimal temperature [27].

Q2: We observe degradation of our target thermolabile compounds during UAE. How can this be mitigated?

- A: To protect thermolabile compounds:

- Pulse Mode: Operate the ultrasonic unit in pulse mode (e.g., 5 seconds on, 5 seconds off) to allow for heat dissipation.

- Cooling: Actively cool the extraction vessel in an ice-water bath.

- Reduce Power: Lower the amplitude of the ultrasound while potentially increasing the extraction time slightly [32].

Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) FAQs

Q1: Our MAE results are inconsistent between runs. How can we improve reproducibility?

- A: Inconsistency typically stems from non-uniform sample preparation or loading.

- Particle Size: Ensure the sample is ground to a very consistent and fine particle size.

- Loading: Do not overload the vessel. Ensure the solvent fully covers the sample and the mixture is homogeneous before sealing.

- Stirring: If your system has magnetic stirring, use it to ensure even distribution of microwave energy [29].

Q2: Is it safe to use organic solvents in a closed-vessel MAE system?

- A: Closed-vessel systems are designed for safe operation with organic solvents under pressure. However, always:

- Refer to the manufacturer's manual for solvent-specific pressure and temperature limits.

- Do not exceed the vessel's rated capacity.

- Ensure vessels are properly sealed and regularly inspected for wear and tear. Using green solvents like ethanol or D-limonene can reduce safety risks [33].

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) FAQs

Q1: We are getting low recovery of polar compounds using pure SC-CO₂. What are our options?

- A: Pure SC-CO₂ is non-polar and best for lipophilic compounds. To extract polar compounds:

- Use a Co-solvent: Add a polar modifier like ethanol (5-20%) to the CO₂ stream. This dramatically increases the solubility of polar molecules such as tannins and polyphenols [31].

- Optimize Parameters: Systematically increase pressure and temperature to enhance solvating power, but be mindful of potential co-extraction of unwanted compounds.

Q2: The extractor vessel frequently clogs during SFE of plant materials. How can we prevent this?

- A: Clogging is often caused by fine particles or high moisture content.

- Sample Preparation: Avoid over-grinding the sample into very fine powders.

- Use Inert Packing: Mix the sample with an inert dispersant like glass beads or coarse sand to improve flow dynamics and prevent channeling.

- Pre-dry: Ensure the sample is adequately dried before loading, unless the protocol specifically requires moisture [30].

Comparative Data and Workflow Visualization

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for the three techniques, illustrating their efficiency and application scope.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced Extraction Techniques

| Extraction Technique | Reported Yield/Content Increase | Key Advantages | Optimal For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound (UAE) | Total phenols from Tamus communis: 243.94 mg CA g⁻¹ (UAE) vs 80.43 mg CA g⁻¹ (conventional) [27] | Rapid, lower temperature, reduced solvent use, simple equipment | Fragile plant tissues, thermolabile compounds, phenolic compounds [27] [28] |

| Microwave (MAE) | Extract yield from Piper betle L.: 8.92% under optimized MAE [29] | Extremely fast, volumetric heating, high efficiency | Polar compounds, internal glandular structures (e.g., trichomes in cannabis) [29] [33] |

| Supercritical Fluid (SFE) | High-purity tannin fractions with tailored solubility profiles [31] | Solvent-free (with CO₂), highly selective, preserves functional activity | Lipids, essential oils, selective fractionation of polar compounds with modifiers [30] [31] |

Experimental Workflow and Logical Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making pathway and experimental workflow for selecting and applying these advanced extraction techniques.

Diagram 1: Decision Workflow for Extraction Technique Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for successful implementation of the featured extraction techniques.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase Enzyme | Breaks down cellulose in plant cell walls, synergizing with UAE to release polyphenols and other intracellular compounds [28]. | Use in UAE for tough matrices; optimize dosage (e.g., 2.5%) and pH (e.g., 5.6) for maximum efficiency. |

| Food-Grade Ethanol | A versatile, green solvent for UAE and MAE, effective for a wide range of polar bioactive compounds. Also used as a co-solvent in SFE [29] [28]. | Preferred concentration is 50-95% (v/v). It is GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe), renewable, and biodegradable. |

| D-Limonene | A green, non-polar solvent derived from citrus peels, used as a safe alternative to hexane in MAE for extracting lipophilic compounds like cannabinoids [33]. | Exhibits inherent anti-cancer properties, which may synergize with the extracted bioactive compounds. |

| Supercritical CO₂ | The primary solvent for SFE. It is inert, non-toxic, and leaves no residue, making it ideal for producing high-purity, solvent-free extracts [30] [31]. | Requires specialized equipment. Its solvating power is tunable with pressure and temperature. |

| Ethanol (as SFE Modifier) | Added to SC-CO₂ to increase the solubility of mid- to high-polarity molecules, such as tannins and certain polyphenols [31]. | Typically used at 5-15% of the total solvent flow rate. Ensures the final extract remains free of harsh chemical solvents. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Silica Column Chromatography Troubleshooting

Q: My column separation is poor, and compounds are co-eluting. What could be the issue?

Poor separation in silica column chromatography can stem from several sources. First, an incorrect flow rate can cause band widening or tailing; the flow should be adjusted so it's not too fast or too slow [34]. Second, an overmassed column, where too much sample has been loaded, will exceed the capacity of the silica and lead to poor resolution [34]. Finally, if the selected solvent system lacks the appropriate polarity to resolve the compounds, they will not separate effectively. Running a TLC analysis beforehand can help determine the correct solvent system [34].

Q: The flow rate in my column has become extremely slow. How can I fix this?

A very slow flow rate is frequently caused by a clogged frit at the bottom of the column, often due to fine silica particles or debris from the sample [34]. Another common cause is the silica gel becoming too densely packed, either from initial packing or from the settling process during running. In this case, the column may need to be repacked [34].

Q: I see air bubbles or cracks in the silica bed. Is this a problem?

Yes, air bubbles or cracks can create channels within the column, disrupting the uniform flow of solvent and leading to band deformation and poor separation [34]. To prevent this, ensure the column is packed uniformly without air bubbles and that the silica bed never runs dry during the packing or running process. Always keep the solvent level well above the top of the silica [34].

Q: My compound is not stable on silica. What are my options?

If you suspect your compound is decomposing on silica (which can be tested using a 2D TLC method), you should consider alternative stationary phases like alumina [34]. Alternatively, you could postpone purification and proceed to the next synthetic step if feasible, or switch to a different purification technique altogether, such as crystallization or distillation [34].

Table 1: Common Silica Column Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Separation/Co-elution | Incorrect flow rate, overmassed column, unsuitable solvent system [34] | Adjust flow to optimal rate; reduce sample load; optimize solvent polarity via TLC [34] |

| Very Slow Flow Rate | Clogged inlet/outlet frit, too finely packed silica [34] | Repack the column; check and clean frits [34] |

| Bands Deformed/Tailing | Air bubbles or channels in silica bed [34] | Ensure column is packed uniformly and does not run dry [34] |

| Compound Decomposition | Compound reacts with or is unstable on silica [34] | Use alternative stationary phase (e.g., alumina) or purification method (e.g., crystallization) [34] |

Magnetic Bead Protocol Troubleshooting

Q: The yield from my magnetic bead extraction is low. How can I improve it?

Low yield can be attributed to several factors. The binding efficiency is critical; ensure the bead type and surface chemistry are appropriate for your target molecule (e.g., silica-coated for DNA, carboxylated for broader applications) and that the parking area (space each binding group occupies) is optimized [35] [36]. The bead concentration must be sufficient to capture all target molecules without wasting resources [35]. Finally, incomplete elution can leave your product on the beads, so ensure the elution buffer is appropriate and that you are using a sufficient volume with adequate incubation time [36].

Q: My beads are clumping together (aggregating). Why is this happening, and how do I stop it?

Aggregation is a common challenge that can reduce binding efficiency and assay accuracy. It can be caused by the surface charge and magnetic properties of the beads [35]. To minimize aggregation, ensure the beads are well-suspended by mixing the solution thoroughly but gently before and during use. Using bead suspensions designed for minimal sedimentation can also help maintain an even distribution [35].

Q: I am getting inconsistent results between different runs and users. How can I standardize my protocol?

Inconsistency often arises from poorly defined separation steps. The magnetic response—how quickly and evenly beads move toward the magnet—is a key parameter [37]. Standardizing the separation time and the position of the tube in the magnetic rack is crucial for reproducible results. For scaling up, it is essential to characterize and validate the magnetic separation process thoroughly, as conditions that work for small volumes may not directly translate to larger batches [37].

Q: What is the difference between monodispersed and polydispersed beads, and which should I use?

Monodispersed beads are uniform in size, which leads to more predictable and consistent behavior, making them ideal for diagnostic work and other assays where reproducibility is paramount [35]. Polydispersed beads vary in size and may offer a broader functional range, which can be beneficial for certain specific assays [35]. For most applications where consistency is key, such as high-throughput screening, monodispersed beads are recommended.

Table 2: Optimization Parameters for Magnetic Beads

| Parameter | Impact on Performance | Optimization Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Bead Size | Affects surface area, binding capacity, and separation speed [35]. | 1-3 µm beads offer a good balance for most applications; smaller beads for imaging/drug delivery [35]. |

| Bead Concentration | Directly affects yield and cost; too low reduces yield, too high causes waste [35]. | Find the minimum concentration that gives consistent, high yields [35]. |

| Surface Coating | Determines which molecules bind and the efficiency of elution [36]. | Silica coating for nucleic acids; carboxyl coating for broader applications and easier elution [36]. |

| Magnetic Response | Impacts the speed and reliability of separations [35]. | Use beads with a fast magnetic response for even and quick separations, especially in complex assays [35]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Dry-Loading a Sample onto a Silica Column

This method is preferred when your compound has poor solubility in the intended column solvent system [34].

- Dissolve: Completely dissolve your sample in a suitable solvent (e.g., DCM) in a round-bottomed flask [34].

- Add Silica: Add dry silica gel to the solution (approximately 10–20 times the mass of your sample) [34].

- Suspend: Gently swirl or stir to suspend all the silica within the solution [34].

- Evaporate: Use a rotary evaporator to gently remove all solvent until the silica is dry and free-flowing. If the mixture remains oily, add more silica and repeat the evaporation [34].

- Load Column: Carefully add solvent to your prepared column so the level is 2–3 cm above the silica. Slowly pour the dry, sample-saturated silica into the column, ensuring it settles evenly and the solvent level never drops below the silica surface [34].

- Run Column: Proceed with running the column as usual [34].

Protocol: High-Throughput Nucleic Acid Purification Using Magnetic Beads (BOMB Method)

This open-platform method is cost-effective and scalable for 96-well plates [36].

- Bind: Mix the nucleic acid-containing sample (e.g., PCR reaction, lysate) with a well-resuspended magnetic bead solution. Incubate to allow binding. The binding capacity depends on the bead surface area and chemistry [35] [36].

- Immobilize: Place the tube or plate on a magnetic rack until the solution clears, indicating all beads are captured.

- Wash: Carefully remove and discard the supernatant. With the tube still on the magnet, add wash buffer (often ethanol-based) to the beads. Gently mix if needed to fully wash the pellet, then remove the wash buffer completely. Repeat as required [36].

- Dry: Briefly air-dry the bead pellet (e.g., 5-10 minutes) to evaporate residual ethanol, which can inhibit downstream reactions. Do not over-dry.

- Elute: Remove the tube from the magnet. Resuspend the beads in an elution buffer (e.g., TE buffer or nuclease-free water). Incubate to allow the nucleic acids to dissociate from the beads.

- Recover: Place the tube back on the magnetic rack. Once the solution is clear, transfer the supernatant, which now contains your purified nucleic acids, to a new tube [36].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Extraction Protocols

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Silica Gel (Various pore sizes) | Stationary phase for column chromatography; separates compounds based on polarity [34]. |

| Alumina | Alternative stationary phase for compounds unstable on silica [34]. |

| Silica-Coated Magnetic Beads | Magnetic particles for reversible nucleic acid binding; ideal for DNA/RNA purification [36]. |

| Carboxyl-Coated Magnetic Beads | Versatile magnetic particles with negative charge; used for broad applications including protein isolation [36]. |

| Magnetic Separation Rack | Device to immobilize magnetic beads during wash and elution steps for tube or plate formats [36]. |

| TLC Plates | Used for analytical separation to monitor reactions and determine optimal column solvent systems [34]. |

| USER Enzyme (UDG + EndoVIII) | Enzyme mixture used in ancient DNA research to remove uracil residues caused by cytosine deamination, reducing DNA damage patterns [38]. |

| MinElute Spin Columns | Silica columns designed to retain shorter DNA fragments (as low as 70 bp), improving yield for degraded samples [38]. |

Automated and High-Throughput Platforms for Scalable Processing

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common HTS and Automation Issues

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality & reproducibility | High variability between plates or users; inability to reproduce others' work; high false positive/negative rates [39]. | Manual processes subject to inter- and intra-user variability; lack of standardized protocols; undetected human error [39]. | Implement automated liquid handlers with in-process verification (e.g., DropDetection technology); use checklists and flowcharts for standardized procedures [40] [39]. | Establish and validate robust SOPs; utilize automation to minimize manual intervention; perform regular assay quality control (e.g., Z-factor monitoring) [41]. |

| System Integration & Operation | Unexpected machine faults; communication bottlenecks between instruments; costly downtime [40] [41]. | Failure of legacy equipment to integrate with modern systems; lack of vendor-agnostic workflow; scheduling complexity of interconnected modules [41]. | Start troubleshooting from a known good state (e.g., reboot, home position); perform root cause analysis (RCA); ensure robust preventative maintenance protocols [40]. | Invest in middleware or protocol converters for seamless integration; create detailed maintenance schedules; train staff on system monitoring and validation [41]. |

| Liquid Handling & Precision | Inconsistent results across well plates; low Z-factor scores; inaccuracies at low volumes [41]. | Improperly calibrated liquid handlers; pipettor variance; sub-microliter dispensing errors [39] [41]. | Verify that correct liquid volumes are dispensed using integrated detection technology; substitute components to isolate the faulty module; re-calibrate equipment [40] [39]. | Regularly service and calibrate liquid handling systems; adopt non-contact dispensers for high precision at low volumes; implement miniaturization where appropriate [39] [41]. |

| Sample & Reagent Integrity | Unusual smells (e.g., burning rubber, hot metal); visible leaks or wear; failed assay performance [40]. | Worn tooling; expired or degraded reagents; overheating or misaligned components [40]. | Use sensory checks (sight, sound, smell) to identify problem areas; review maintenance logs for replacement part schedules; replace consumables [40]. | Adhere to recommended maintenance instructions (lubrication, belt tensioning); track reagent lot numbers and expiration dates; monitor machine sounds and temperatures during normal operation [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Platform Questions

What are the primary benefits of automating a high-throughput screening (HTS) workflow? Automation significantly enhances data quality and reproducibility by standardizing workflows and reducing human error and variability [39]. It increases throughput and efficiency, allowing for the screening of large compound libraries at multiple concentrations [39]. Furthermore, automation enables miniaturization, reducing reagent consumption and overall costs by up to 90%, while also streamlining data management for faster insights [39].