Optimizing Nutrient Concentrations for Oligotrophic Bacteria: Advanced Cultivation Strategies for Pharmaceutical Research

Oligotrophic bacteria, adapted to low-nutrient environments, pose significant challenges for cultivation and detection in pharmaceutical quality control and drug development.

Optimizing Nutrient Concentrations for Oligotrophic Bacteria: Advanced Cultivation Strategies for Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

Oligotrophic bacteria, adapted to low-nutrient environments, pose significant challenges for cultivation and detection in pharmaceutical quality control and drug development. This article synthesizes foundational knowledge and advanced methodologies to address these challenges. We explore the distinct physiology and survival strategies of oligotrophs, detail innovative cultivation techniques like dilution-to-extinction and the use of oligotrophic media, and provide frameworks for troubleshooting common growth issues. Furthermore, we evaluate validation strategies, including metagenomic analysis and comparative physiology, to confirm strain purity and function. This guide is tailored for researchers and scientists seeking to reliably recover, grow, and study these fastidious organisms to mitigate contamination risks and harness their potential in biotechnological applications.

Understanding the Oligotrophic Niche: Physiology, Challenges, and Pharmaceutical Relevance

FAQs: Understanding Fundamental Concepts

1. What is the fundamental difference between an oligotroph and a copiotroph?

Oligotrophs and copiotrophs represent two distinct life strategies for survival in contrasting nutrient environments [1].

- Oligotrophs are organisms that thrive in environments with very low levels of nutrients. They are characterized by slow growth, low rates of metabolism, and generally low population density [2].

- Copiotrophs, in contrast, are found in nutrient-rich environments and exhibit a "feast-or-famine" lifestyle, rapidly consuming available nutrients and then struggling when those nutrients are depleted [3].

2. Why is cultivating oligotrophic bacteria particularly challenging in a laboratory setting?

Cultivating oligotrophs is difficult because many are adapted to chronic starvation conditions and can be sensitive to the nutrient-rich media standard for copiotrophs [4]. When transferred to rich media, the sudden influx of nutrients can overwhelm their metabolism, potentially causing oxidative damage or other physiological harm. Furthermore, oligotrophs often grow very slowly, with long lag phases, and may not form visible colonies for extended periods [4] [5].

3. What are some key physiological and genomic adaptations of oligotrophs?

Oligotrophs possess several key adaptations for survival in low-nutrient conditions:

- High-Affinity Transport Systems: They have efficient, high-affinity transport systems to scavenge nutrients from dilute solutions [4].

- Genomic Efficiency: They typically have smaller genomes and fewer ribosomal RNA operons compared to copiotrophs, which contributes to their slower growth [3].

- Morphological Adaptations: Many have a high surface-to-volume ratio (e.g., small cell volume, prosthecate cells) to maximize nutrient uptake [4] [2].

4. How do interactions with heterotrophic bacteria differ between oligotrophic and eutrophic (copiotrophic) cyanobacteria under stress?

Research on Synechococcus ecotypes shows these interactions differ significantly. Under concurrent warming and iron limitation, oligotrophic co-cultures often form tighter, more mutually beneficial relationships with their bacterial partners, involving exchanges of carbon substrates for nutrients like iron. In contrast, eutrophic (copiotrophic) co-cultures experience intensified competition and opportunistic exploitation by dominant bacteria under the same stresses [6].

5. Can oligotrophic bacteria be used in applied industrial settings?

Yes. Oligotrophic bacteria, often called "oligophiles" in this context, are valuable as bioindicators. Their counts can far exceed standard plate counts, making them superior tools for environmental monitoring in ultra-clean environments like aseptic pharmaceutical production units, where they provide a more sensitive measure of contamination control [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Optimizing Oligotroph Cultivation

Problem 1: No Growth in Primary Culture

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessively rich medium | Check literature for habitats of your isolate. | Use dilute, oligotrophic media (e.g., Ravan medium with 50-100 mg/L total carbon) [5]. |

| Insufficient incubation time | Check plates microscopically for microcolonies. | Extend incubation time significantly (weeks to a month) and incubate at a lower temperature (e.g., 20-22°C) [5]. |

| Inadequate aeration | Observe if culture is static. | Use shaking incubators (150-250 rpm) and ensure culture vessels are loosely covered to allow gas exchange [7] [8]. |

Problem 2: Culture Growth is Unreliable or Stops After Transfer

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient shock | Compare growth in serial transfers on low-nutrient media. | Avoid sudden transfers to rich media. Acclimate cultures by gradually increasing nutrient concentrations over several transfers [4]. |

| Accumulation of toxic waste products | Measure pH and observe cell death in stationary phase. | Use larger culture volumes and dilute frequently, or use semi-continuous culture methods to maintain cells in exponential phase [6]. |

Problem 3: Unable to Replicate a Published Co-culture Experiment

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unaccounted for ecotype-specific interactions | Verify the exact strain and its origin (oligotrophic vs. eutrophic). | Ensure you are using the correct ecotype, as interactions are not universal. Oligotrophic strains (e.g., clade II) and coastal strains (e.g., clade CB5) behave differently [6]. |

| Incorrect stressor application | Calibrate equipment and measure actual Fe concentrations. | Precisely control and document stressor levels (e.g., Fe concentration at 2 nM for limitation) and temperature, as interactive effects are critical [6]. |

Quantitative Comparison: Oligotrophs vs. Copiotrophs

Table 1: Key characteristics differentiating oligotrophic and copiotrophic bacteria.

| Characteristic | Oligotrophs | Copiotrophs |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred Nutrient Environment | Low nutrient concentrations (e.g., <1-5 mg organic C/L) [4] | High nutrient concentrations (up to 100x higher than oligotrophs) [3] |

| Maximum Growth Rate | Slow | High [3] |

| Growth Strategy | Efficient, steady-state | "Feast-and-famine," rapid response to pulses [3] |

| Carbon Use Efficiency | Higher (more carbon directed to biomass) [3] | Lower (more carbon used for energy/maintenance) [3] |

| rRNA Operon Copy Number | Low (e.g., 1) [3] | High (e.g., up to 15) [3] |

| Motility & Chemotaxis | Often less motile [6] | Typically highly motile and chemotactic [3] |

| Cell Size | Often smaller (high surface-to-volume ratio) [4] [2] | Larger [3] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolating Oligotrophic Bacteria from Environmental Samples

This protocol is adapted from methods used to monitor cleanrooms and isolate bacteria from aquatic environments [5].

1. Materials:

- Ravan Medium (or other dilute nutrient medium) [5]

- Sterile swabs or sampling filters

- Incubator (capable of 20-22°C)

2. Procedure: a. Sample Collection: Collect water or surface samples using sterile techniques. For surfaces, use a moistened sterile swab. b. Inoculation: Streak the sample onto plates of Ravan medium. Alternatively, for liquid samples, spread a small volume onto the agar surface. c. Incubation: Incubate plates at 20-22°C for at least 21-28 days [5]. d. Observation: Check for growth weekly. Use a stereomicroscope to identify microscopic colonies that may not be visible to the naked eye [5].

Protocol 2: Testing Co-culture Responses to Concurrent Stressors

This protocol is based on research investigating Synechococcus-bacteria interactions under warming and iron limitation [6].

1. Materials:

- Sterile Aquil medium made with trace metal clean artificial seawater [6]

- Oligotrophic and eutrophic Synechococcus strains with associated bacterial communities

- Shaking incubators at controlled temperatures (e.g., 20°C, 24°C, 27°C)

- Chelex-treated nutrients to control iron levels

2. Procedure: a. Medium Preparation: Prepare Aquil medium with low iron (2 nM, LFe) and high iron (250 nM, HFe) concentrations. Purify macronutrient stocks with Chelex 100 resin to remove contaminating metals [6]. b. Culture Setup: Inoculate triplicate cultures of each Synechococcus-bacteria co-culture into the LFe and HFe media. c. Application of Stressors: Incubate cultures at different temperatures (e.g., 20°C, 24°C, 27°C) under a 12:12 light/dark cycle [6]. d. Maintenance: Maintain cultures in mid-exponential phase for at least 12 generations using semi-continuous dilution with pre-conditioned medium every other day [6]. e. Analysis: Harvest cells for downstream 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, metagenomic, and metatranscriptomic analyses to assess community and metabolic changes [6].

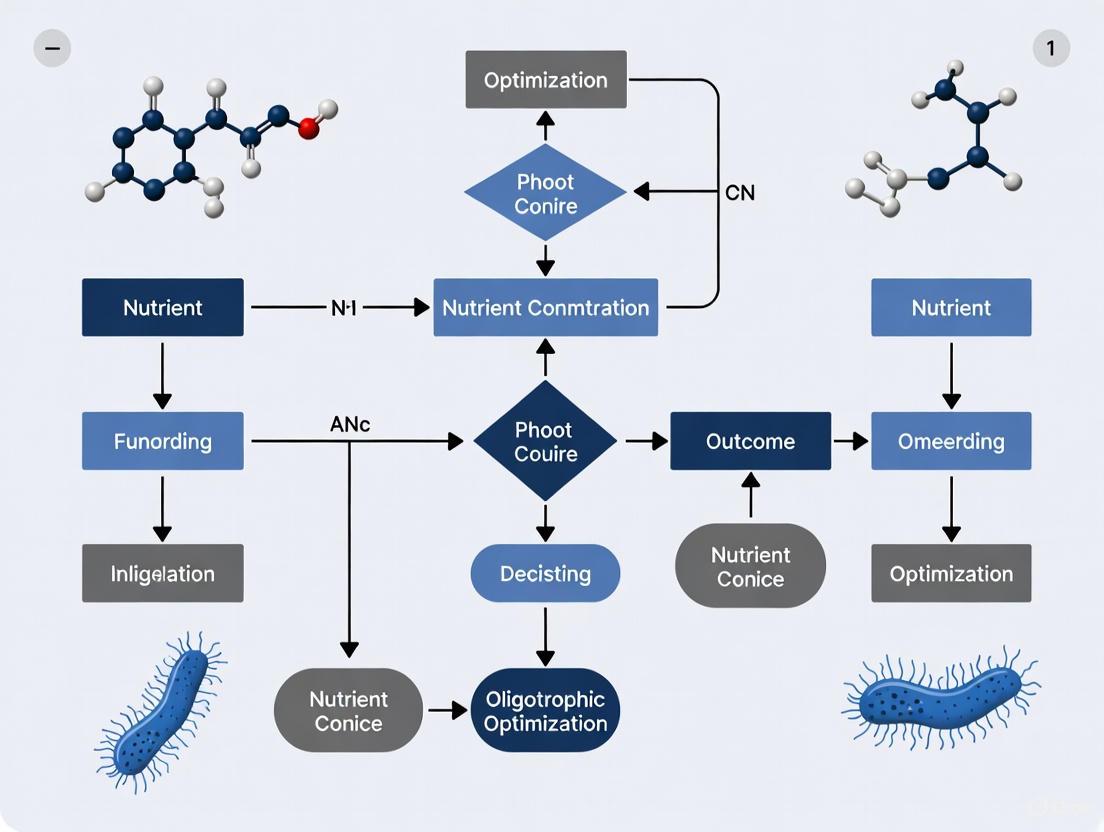

Conceptual Diagrams

Life Strategy Activation

Oligotroph Isolation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials for oligotroph growth research.

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ravan Medium | A defined, dilute nutrient medium for cultivating oligophilic bacteria [5]. | Contains only 50 mg/L total organic carbon. Ideal for primary isolation and counting oligotrophs. |

| Chelex 100 Resin | Chelating resin used to remove trace metals from culture media [6]. | Critical for precise iron limitation studies in trace metal clean media. |

| Aquil Medium | Artificial seawater medium for marine microbial culture [6]. | The basis for creating defined nutrient conditions for marine oligotrophs and copiotrophs. |

| Soybean Casein Digest Agar (SCDA) | A conventional, nutrient-rich medium [5]. | Serves as a control to compare against oligotrophic media; supports copiotrophs. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the "Great Plate Count Anomaly" and why does it matter for my research? The "Great Plate Count Anomaly" describes the large discrepancy—often by several orders of magnitude—between the number of bacterial cells visible under a microscope and the number that can actually be grown and counted on standard agar plates [9] [10]. This anomaly matters because it means the vast majority of environmental bacteria, particularly those with oligotrophic lifestyles (adapted to low-nutrient conditions), are missed by traditional cultivation methods. This creates a significant bias in your research, potentially causing you to overlook key microbial players in drug discovery, environmental processes, or community interactions [9] [11].

Q2: What are the fundamental differences between oligotrophic and copiotrophic bacteria? Oligotrophic and copiotrophic bacteria have distinct physiological strategies, primarily in their growth kinetics and substrate affinity. The table below summarizes their key differences:

| Characteristic | Oligotrophic Bacteria | Copiotrophic Bacteria |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate | Slow-growing [9] [11] | Fast-growing [9] |

| Nutrient Adaptation | Thrive in low-nutrient environments [9] | Thrive in nutrient-rich environments [9] |

| Substrate Affinity | High substrate affinity and utilization efficiency [9] | Lower substrate affinity, higher Michaelis-Menten kinetics [9] |

| Laboratory Behavior | Often outcompeted by copiotrophs in rich media; form the "uncultivated majority" [11] | Readily grow on standard, nutrient-rich lab media [9] |

Q3: Besides nutrient concentration, what other factors might prevent my target oligotroph from growing? Your target bacterium might be in a dormant state. It's crucial to consider that many microorganisms exist in dormant states such as sporulation, a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, or as persistent cells, waiting for specific environmental cues to resuscitate and grow [9]. Other factors include:

- Lack of Essential Growth Factors: Some bacteria require specific vitamins, signaling molecules, or co-factors not present in your medium [9] [11].

- Symbiotic Dependencies: The bacterium might rely on other microbes to detoxify metabolites or supply essential nutrients, making pure culture challenging [11].

- Oxygen Sensitivity: If your target is a strict anaerobe, it will be killed or inhibited by oxygen during sample handling or cultivation [12] [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Cultivating Oligotrophic Bacteria

Problem: No growth or very slow growth on standard laboratory media.

Potential Cause 1: Media toxicity from excessive nutrient levels.

- Solution: Employ extreme nutrient dilution.

- Protocol: Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

- Prepare Dilute Media: Create a defined, low-nutrient medium. A successful example for freshwater oligotrophs is the "med2" or "med3" medium, containing carbohydrates and organic acids in the range of ~1 mg DOC per liter to mimic natural conditions [11]. Filter-sterilize (0.2 µm) instead of autoclaving to prevent chemical modification of delicate components [11].

- Dilute Inoculum: Perform a high-throughput dilution of your environmental sample in a 96-deep-well plate, aiming for a statistical distribution of one cell or less per well [11].

- Incubate: Incubate for extended periods (6-8 weeks or more) at a temperature relevant to the sample's origin [11].

- Screen for Growth: Monitor for turbidity or use flow cytometry to detect slow, low-level growth [11].

- Protocol: Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

Potential Cause 2: The cells are in a dormant or VBNC state.

- Solution: Incorporate resuscitation strategies.

- Protocol: Sample Pre-incubation

- Pre-incubate the sample in a nutrient-free buffer (e.g., filter-sterilized water from the original habitat) for several hours before attempting cultivation. This allows cells to recover from shock and activate metabolic processes without the pressure of rapid division [9].

- Consider "Scout Theory": This theory proposes that in a dormant population, a few cells stochastically activate to "scout" the environment. If conditions are favorable, they can signal the rest of the population to resuscitate. Mimicking these natural signals in your medium could be key [10].

- Protocol: Sample Pre-incubation

Potential Cause 3: Lack of essential micronutrients or growth factors.

- Solution: Systematically amend media with key compounds.

- Protocol: Vitamin and Catalase Supplementation

- Amend your dilute base medium with a cocktail of B vitamins (e.g., Biotin, B12) at nanomolar concentrations [11].

- Adding a low concentration of catalase can help detoxify reactive oxygen species and has been used successfully in media for methylotrophs and other oligotrophs [11].

- Test the addition of known bacterial signaling molecules like homoserine lactones at very low concentrations.

- Protocol: Vitamin and Catalase Supplementation

Problem: Contamination by fast-growing copiotrophs overruns my cultures.

Potential Cause: The cultivation conditions favor rapid growers.

- Solution: Use physical separation and media that favor slow-growers.

- Protocol: High-Throughput Dilution

- As described in the "Dilution-to-Extinction" protocol, statistically diluting the sample to a single cell per well physically separates oligotrophs from fast-growing competitors, preventing them from being overrun [11].

- Avoid Rich Substrates: Do not use tryptic soy broth (TSB), Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, or other high-nutrient media for initial isolation, as they strongly select for copiotrophs [9] [10].

- Protocol: High-Throughput Dilution

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core methodological shift required to successfully isolate oligotrophic bacteria, moving from traditional failed approaches to modern, successful strategies.

Experimental Media & Reagent Solutions

The table below provides a comparison between traditional media formulations that often fail and modern, successful alternatives for cultivating oligotrophic bacteria.

| Reagent/Medium Type | Traditional Formulation (Prone to Failure) | Optimized Formulation for Oligotrophs | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Carbon Source | High-dose Glucose (e.g., 10 g/L) | Mixed Carbon (e.g., Pyruvate, Acetate, Glucose) at ~1-10 mg/L total DOC [11] | Provides energy and carbon building blocks without inducing metabolic shock or favoring fast growers. |

| Nutrient Broth | High Concentration (e.g., 8 g/L Peptone) | Extreme Dilution (e.g., 0.01% Peptone) or Omission [10] | Source of nitrogen, amino acids, and minerals. High concentrations are toxic to oligotrophs; dilution is key. |

| Vitamins & Cofactors | Often omitted | B-Vitamin Cocktail (B12, Biotin, etc.) [11] | Essential for many oligotrophs with auxotrophies; required in minute quantities for core metabolism. |

| Detoxifying Agents | Often omitted | Catalase [11], Resazurin (as redox indicator) [13] | Catalase degrades harmful H₂O₂. Resazurin indicates redox potential (pink=oxidized/high O₂, clear=reduced/low O₂). |

| Solidifying Agent | Standard Agar | Gellan Gum (Phytagel) or low-gelling Agarose | Creates a clearer, potentially less inhibitory gel matrix that is more suitable for delicate oligotrophs. |

| Reducing Agents | Not used for aerobes | Cysteine-HCl, Sodium Sulfide [13] | Binds trace oxygen in media, creating a micro-oxide environment essential for strict anaerobes and beneficial for some microaerophiles. |

FAQ: Understanding Oligotrophic Bacteria

What are the defining physiological traits of oligotrophic bacteria? Oligotrophic bacteria are specialized for survival in nutrient-poor environments. Their key traits include high substrate affinity to scavenge limited nutrients, reduced maximum growth rates as a trade-off for this high affinity, and genome streamlining, which involves small genome size and reduced genomic redundancy to minimize metabolic cost [14] [15]. This combination defines their life history as k-strategists, which compete effectively in stable, low-nutrient conditions, in contrast to copiotrophic r-strategists that thrive in nutrient-rich but variable environments [15].

Why do my oligotrophic cultures fail to grow in standard laboratory media? Standard laboratory media are often designed for copiotrophic bacteria and contain nutrient concentrations that are toxic to many obligate oligotrophs [14]. Their metabolic systems are optimized for scarcity, and a sudden nutrient upshift can cause fatal metabolic imbalances [14]. Furthermore, streamlined oligotrophs may have lost the regulatory genes needed to respond to rapid environmental change, making them difficult to culture using conventional methods [15].

How can I accurately measure the slow growth rates of oligotrophic bacteria? Accurately measuring the slow growth of oligotrophs requires specific techniques. Optical Density (OD600) measurements must be performed with care, as slow growth can lead to low cell densities that are near the detection limit [8]. It is crucial to construct a standard calibration curve to convert OD readings to cell density for your specific strain [8]. For more precise, in-situ measurements without culturing, Quantitative Stable Isotope Probing (qSIP) with 18O–H2O or 13C-labeled substrates can be used to directly measure the growth rates of specific taxa within a mixed microbial community [16].

Troubleshooting Guide for Oligotroph Research

Problem: No or Low Growth in Liquid Culture

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Excessively high nutrient concentration [14] | Dilute standard media (e.g., 100-fold diluted nutrient broth) [17] or use custom low-nutrient media. |

| Toxic nutrient shock [14] | Avoid sudden exposure to rich nutrients; use a gradual, step-up approach for nutrient acclimation. |

| Incorrect temperature [8] | Lower the incubation temperature (e.g., to 30°C or room temperature) to reduce metabolic stress and mitigate potential toxicity [18]. |

| Insufficient incubation time [8] | Extend incubation time significantly (e.g., days or weeks), as doubling times can exceed 5 hours [14]. |

Problem: Inconsistent or Unreliable OD600 Measurements

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Low cell density (common with slow growers) [8] | Concentrate cells via centrifugation or use a culture vessel with a long pathlength for measurement. |

| Cells settling during measurement [8] | Mix the sample thoroughly immediately before measurement to ensure a uniform suspension. |

| "OD-transparent" cells [8] | Use alternative methods like cell counting with a hemocytometer or flow cytometry. |

| Lack of a strain-specific calibration curve [8] | Construct a standard curve of OD600 vs. cells/mL (CFU) for your specific bacterial strain. |

Problem: Contamination by Fast-Growing Bacteria

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Overgrowth by copiotrophs in standard media [16] | Use low-nutrient selective media that favor slow-growing oligotrophs and inhibit copiotrophs. |

| Insufficient purity checks | Include sterile media controls and regularly check cultures for contaminants using microscopy and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol: Measuring Growth Kinetics and Nutrient Affinity

Objective: To determine the relationship between nutrient concentration and growth rate for an oligotrophic bacterium, specifically estimating the half-saturation constant (KM).

Methodology:

- Media Preparation: Prepare a series of liquid media with the target nutrient (e.g., glucose, succinate) across a wide concentration gradient, from nanomolar to micromolar ranges [19].

- Inoculation: Inoculate each media replicate with a small, standardized inoculum of the target oligotroph.

- Incubation: Incubate under optimal conditions (temperature, shaking) for an extended period, monitoring growth.

- Growth Monitoring: Measure culture density (OD600) regularly. For greater precision with low densities, use direct cell counting or qSIP [16].

- Data Analysis: Fit the growth rate data at each nutrient concentration to a Michaelis-Menten model to calculate the maximal growth rate (μmax) and the half-saturation constant (KM), a key measure of substrate affinity [19].

Quantitative Data on Oligotrophic Traits

Table 1: Characteristic Comparison of Bacterial Life History Strategies

| Trait | Oligotrophs (e.g., SAR11) | Copiotrophs (e.g., Vibrios) |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Size | Streamlined; 1.28–1.46 Mb [15] | Larger, more complex genomes [15] |

| Cell Volume | Small (< 0.1 μm³) [14] | Larger (> 1.0 μm³) [14] |

| Doubling Time | Slow (> 5 hours) [14] | Fast (< 1 hour) [14] |

| Primary Transport Systems | ABC transporters with binding proteins [14] | Phosphotransferase systems (PTS) [14] |

| Nutrient Affinity (KM) | Very high (can reach nanomolar range) [14] | Lower (micromolar to millimolar range) [14] |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Microbial Growth Models under Nutrient Limitation

| Parameter | Description | Relationship with Initial Nutrient Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Maximal Nutrient Uptake Rate (V) | The theoretical maximum rate at which a cell can take up a nutrient [19]. | Decreasing function of initial nutrient concentration [19]. |

| Half-Saturation Constant (K) | The nutrient concentration at which the growth/uptake rate is half of V [14]. | For ABC transporters, it is a function of binding protein abundance, not a fixed constant [14]. |

| Biomass Yield (Y) | The amount of biomass produced per unit of nutrient consumed [19]. | Decreasing function of initial nutrient concentration [19]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Oligotrophic Bacteria Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Diluted Nutrient Broth | A low-nutrient medium used to isolate and cultivate oligotrophic bacteria without causing nutrient shock [17]. |

| 18O–H2O (97 atom %) | A stable isotope used in Quantitative Stable Isotope Probing (qSIP) to measure in-situ growth rates of microbial taxa by tracking isotope incorporation into DNA [16]. |

| 13C-labeled substrates (e.g., glucose, succinate) | A stable isotope used in qSIP to trace nutrient assimilation and link growth to the metabolism of specific carbon sources [16]. |

| CsCl Solution | Used in isopycnic centrifugation to separate nucleic acids by density during the qSIP protocol [16]. |

| SOC Medium | A nutrient-rich recovery medium used after bacterial transformation or other stressful procedures to allow for cell repair and initial growth before plating on selective media [18]. |

Diagrams of Key Concepts

Oligotroph vs. Copiotroph Nutrient Uptake

Oligotroph Research Workflow

FAQs: Understanding and Controlling Oligotrophs in Water Systems

What are oligotrophic bacteria and why are they a problem in high-purity water systems?

Oligotrophic bacteria are microorganisms adapted to survive in environments with extremely low nutrient levels, often less than part-per-billion quantities of organic and inorganic molecules [20]. In pharmaceutical water systems, these bacteria pose a significant challenge because they can proliferate in ultrapure water (UPW) and purified water, where they form biofilms on piping, tanks, and other surfaces [20] [21].

Key problematic genera commonly found in these systems include Ralstonia pickettii, Bradyrhizobium sp., Pseudomonas saccharophilia, and Stenotrophomonas strains [20]. These bacteria can compromise product quality and patient safety, particularly in sterile products where even a single bacterial cell or its cellular degradation products can be detrimental [20] [22].

Based on troubleshooting principles, contamination typically originates from three main sources [23]:

- Inadequate Restart Procedures: Contamination can occur when a system is taken out of service, drained, and exposed to the environment without a robust sanitization plan before restart.

- Feed Water Changes & Excursions: The feed water entering the system is not sterile and contains various bacterial species that continuously challenge the system.

- Personnel and Housekeeping: External contamination introduced through human error or poor practices during system operation or maintenance.

My water system has a persistent microbial count despite regular disinfection. What is the most likely cause?

The most probable cause is the formation of biofilm within the distribution pipeline [24]. Biofilm acts as a protected reservoir for microbes, allowing them to persist and be released into the water even after routine decontamination [24]. Biofilms are communities of bacteria encased in an extracellular polysaccharide matrix, which can adhere to surfaces and provide resistance to disinfection [20]. Troubleshooting such an issue should involve a thorough system assessment to identify design deficiencies, such as dead legs where biofilm can form, and implementation of an enhanced disinfection protocol [24].

Are standard culture methods reliable for monitoring bacterial levels in ultrapure water?

No, conventional culture-based methods significantly underestimate the actual level of bacterial presence [20] [21]. Studies have shown that epifluorescence microscopy (using stains like DAPI and CTC) can detect 10 to 100 times more bacterial cells than plate counts [20]. A large proportion (50-90%) of bacteria in UPW are in a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state [20] [21]. R2A agar is the recommended medium for culturing oligotrophs, as it yields statistically greater numbers of bacteria compared to richer media like Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) [25]. Advanced techniques like flow cytometry (FCM) are showing promise for rapid and accurate total cell counts, including VBNC communities [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Microbial Excursions

Systematic Investigation Approach

When investigating a microbial excursion, apply the principle of Occam's Razor: the simplest explanation is usually the correct one [23]. In a validated system that has been functioning effectively, the cause is likely not a fundamental design flaw but a more recent, straightforward issue.

| Investigation Stage | Key Actions | Reference Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Root Cause Analysis | Inspect distribution pipelines for biofilm; analyze system design for dead legs; review recent system shutdowns and restarts. | Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) can be installed for real-time biofilm monitoring [24]. |

| 2. System Assessment | Evaluate the performance and integrity of key components like Reverse Osmosis (RO) membranes and ultraviolet (UV) sterilizers. | RO membrane integrity tests can identify compromised membranes allowing organic contaminants to pass [24]. |

| 3. Corrective Actions | Implement enhanced disinfection (e.g., thermal sterilization at 80°C for 4 hours); replace damaged components; modify system to reduce dead legs. | Periodic chemical cleaning and thermal sterilization of distribution pipelines [24]. |

| 4. Personnel Training | Retrain personnel on proper disinfection procedures, biofilm prevention strategies, and good manufacturing practices (cGMP). | SOP training, retraining, and practicing "cGMP behavior" are paramount [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for Oligotroph Research

Protocol 1: Culturing and Enumerating Oligotrophs from Water Samples

This protocol is adapted from methods used to investigate bacterial populations in ultrapure water systems [20].

1. Sample Collection:

- Clean the sample port exterior with 70% ethanol.

- Allow water to flow at 50 ml/min for 3 minutes before collecting sample.

- Collect water samples into sterile containers.

- For epifluorescence microscopy or PCR, concentrate cells by filtering a large volume of water (e.g., 10 liters) through a 0.2-μm pore size polycarbonate membrane.

2. Enumeration via Epifluorescence Microscopy:

- Staining: Use staining solutions prepared in UPW. Use DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to determine the total number of bacterial cells and CTC (cyanotolyl tetrazolium chloride) to determine the number of respiring cells [20].

- Analysis: Examine stained membranes under an epifluorescence microscope. Count a minimum of 20 microscope fields. The DAPI count minus the CTC count gives the number of non-respiring cells.

3. Enumeration via Culture-Based Methods:

- Medium: Use R2A agar, which is designed for injured heterotrophic and oligotrophic bacteria and is recommended for testing UPW quality [20] [25].

- Incubation: Incubate plates at appropriate temperatures (e.g., 25-30°C) for extended periods (e.g., 5-7 days) to recover slow-growing oligotrophs.

Protocol 2: DNA-Based Detection and Identification

1. DNA Extraction:

- Concentrate bacterial cells from water by centrifugation.

- Resuspend cells in Tris-EDTA-sucrose buffer and incubate with lysozyme.

- Add SDS to lyse cells, then extract DNA with phenol and phenol-chloroform.

- Precipitate DNA with ethanol and resuspend in buffer [20].

2. 16S rRNA Gene Amplification (PCR):

- Primers: Use universal primers to amplify the 16S rRNA gene for general diversity studies. For specific detection, use designed primers (e.g., for R. pickettii or Bradyrhizobium sp.) [20].

- PCR Mix: 25 μl volume containing deoxynucleoside triphosphates, primers, DNA, and Taq+ DNA polymerase.

- Temperature Profile: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min [20].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key materials used in the study of oligotrophs in water systems.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| R2A Agar | A low-nutrient medium recommended for the enumeration of injured heterotrophic and oligotrophic bacteria from water systems. It yields higher and more accurate bacterial counts than richer media [25]. |

| Polycarbonate Membrane Filter (0.2-μm pore size) | Used to concentrate bacterial cells from large volumes of water for subsequent analysis via microscopy, culture, or molecular methods [20]. |

| DAPI Stain | A fluorescent stain that binds to DNA, used in epifluorescence microscopy to determine the total bacterial cell count (including living and dead cells) [20]. |

| CTC Stain | A fluorescent stain used to detect respiring bacterial cells via epifluorescence microscopy. It helps determine the proportion of metabolically active cells in a sample [20]. |

| Universal 16S rRNA Primers | oligonucleotide primers that target conserved regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, allowing for PCR amplification and subsequent sequencing to identify bacterial species present in a sample [20]. |

Visualizing the Contamination Control Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for troubleshooting microbial contamination in a water system, integrating the principles and methods discussed.

Table 1: Efficacy of Water Purification Components in Bacterial Removal

Data adapted from a study comparing bacterial removal rates using different culture media [25].

| Process Component | Reduction using TSA Medium | Reduction using R2A Medium |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Osmosis Unit | 97.4% | 98.4% |

| Ion Exchange Bed | 31.3% | 78.4% |

| Ultraviolet Sterilizer | 72.8% | 35.8% |

| In-line 0.2-μm Filter | +60.7% (Increase) | +15.7% (Increase) |

Table 2: Biostability of Pipe Materials in Ultrapure Water Systems

Data from a 2025 study assessing the purity and biofilm formation potential of different piping materials [21].

| Pipe Material | TOC Migration (mg/L) | Biomass Formation Potential (cells/cm²) | Susceptibility to Ralstonia Biofilm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) | 0.08 | ~5 × 10⁵ | Lower |

| Chlorinated Polyvinyl Chloride (CPVC) | Higher than PVDF | Higher than PVDF | Significant |

| Stainless Steel (SUS) | Data Not Explicit | Data Not Explicit | Significant |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Cultivation Challenges and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Oligotrophic Bacteria Cultivation

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| No growth in primary culture | Media nutrient concentration too high, causing toxicity | Use diluted, oligotrophic-specific media (e.g., Ravan medium); reduce carbon sources to 1-10 mg L⁻¹ [26] [5]. | [26] [5] |

| Lack of essential growth factors or co-factors | Supplement media with soil or environmental extracts from the sample's original habitat [26]. | [26] | |

| Only fast-growing copiotrophs appear | Incubation time too short | Extend incubation time for weeks or months; monitor for microcolonies microscopically [26] [5]. | [26] [5] |

| Standard rich media (e.g., SCDA, LB) used | Use low-nutrient media (e.g., R2A); avoid common rich media [26] [4]. | [26] [4] | |

| Inconsistent growth between replicates | Cells in a dormant or VBNC state | Apply resuscitation techniques; use signal compounds from symbiotic bacteria [26]. | [26] |

| Uncontrolled physicochemical conditions | Mimic natural habitat conditions (temperature, pH); test multiple conditions simultaneously [26]. | [26] |

Optimizing Cultivation Conditions

Table 2: Media and Condition Optimization for Oligotrophic Lineages

| Factor | Standard Lab Practice | Optimized for Oligotrophs | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Source Concentration | High (g L⁻¹): e.g., Tryptone at ~10,000 mg L⁻¹ [27] | Low (mg L⁻¹): e.g., Tryptone at 0.5 mg L⁻¹; total organic carbon at 5 mg L⁻¹ or less [4] [27] | Prevents substrate toxicity and oxidative stress; mimics natural oligotrophic conditions [4]. |

| Media Type | Rich, complex media (e.g., LB, SCDA, TSA) [27] [5] | Dilute, low-nutrient media (e.g., R2A, Ravan medium, soil extract media) [26] [4] [5] | Selects for bacteria adapted to nutrient scarcity; inhibits copiotroph overgrowth [26] [4]. |

| Incubation Time | Short (2-7 days) [5] | Extended (weeks to months) [26] [5] | Allows for slow growth rates and microcolony development [26]. |

| Physical State of Media | Primarily solid agar plates [26] | Combination of liquid and gelled media; use of gellan gum as agar alternative [26] | Some oligotrophs are sensitive to agar; liquid cultures can simulate planktonic states [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly are "oligotrophic" bacteria, and why are they so difficult to culture in industrial settings?

Oligotrophic bacteria are microorganisms specifically adapted to environments with very low nutrient concentrations (e.g., organic carbon at 1-10 mg L⁻¹) [4] [27]. Their difficulty in cultivation stems from two main categories of "uncultivability":

- Yet-to-be-cultivated cells: These bacteria have the potential to grow, but the appropriate laboratory conditions (media, temperature, symbionts) have not yet been identified [26].

- Non-dividing cells (Dormant/VBNC state): These cells are alive but in a non-replicating state, often requiring the removal of inhibitors or addition of specific resuscitation factors to initiate growth [26].

In industrial cleanrooms, these bacteria often outnumber conventional bacteria by up to two orders of magnitude but fail to grow on standard monitoring media like Soybean Casein Digest Agar (SCDA) [5].

Q2: What are the key physiological adaptations of oligotrophic bacteria that I must consider when designing media?

Oligotrophs possess unique physiological traits for survival in low-nutrient environments, which must be mirrored in cultivation protocols:

- High-affinity transport systems: They possess exceptionally efficient nutrient-scavenging systems to pull substrates from dilute solutions. Sudden exposure to high nutrients can overwhelm these systems, leading to lethal oxidative stress or protoplast dehydration [4].

- Cell morphology: Many are ultramicrobacteria with very low cell volume, or have filamentous or prosthecate (appendage-bearing) forms to maximize surface-to-volume ratio for nutrient uptake [4].

- Metabolic flexibility: They employ strategies like mixed-substrate utilization and dynamic metabolic shifts to efficiently use scant resources [27].

Q3: Can you provide a specific, detailed protocol for isolating oligotrophic bacteria from an industrial water system sample?

Protocol: Enrichment and Isolation of Oligotrophic Bacteria from Industrial Water

Objective: To cultivate oligotrophic bacteria from a water sample using a dilution-to-extinction technique in a defined, low-nutrient medium.

Materials:

- Ravan Medium (Dilute) [5]: Glucose (5 mg), Peptone (5 mg), Sodium acetate (5 mg), Sodium citrate (5 mg), Yeast extract (5 mg), Sodium pyruvate (2 mg), Agarose (1 g), Distilled water (to 100 ml), pH 7.0 ± 0.2.

- Soil Extract Medium [26]: Collect soil from a relevant environment, autoclave it with deionized water, filter sterilize the supernatant, and add a small volume (e.g., 1-5% v/v) to a basal salts solution.

- Sterile filtration unit (0.22 µm)

- 96-well microtiter plates

Method:

- Sample Collection: Aseptically collect water sample. Process within 2 hours or store at 4°C for no more than 24 hours.

- Sample Pre-treatment: Filter a large volume (e.g., 1L) of water through a 0.22 µm filter to concentrate cells. Resuspend the filter-bound cells in a small volume (e.g., 10 mL) of sterile, particle-free water from the same source.

- Media Preparation: Prepare both Ravan medium and Soil Extract Medium. Sterilize by autoclaving. For solid media, add the gelling agent.

- Dilution-to-Extinction: Serially dilute the resuspended sample (10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁸) in the liquid versions of both media. Dispense 100 µL of each dilution into the wells of a 96-well plate. Seal the plate to prevent evaporation. This step aims to inoculate wells with a single cell, reducing competition.

- Incubation: Incubate the plates at the temperature characteristic of the sampling environment (e.g., 20-22°C) for 4 to 8 weeks. Do not agitate.

- Monitoring: Check for turbidity or cell growth microscopically every 7-14 days.

- Sub-culturing: Once growth is observed in the highest dilutions, use a sterile pipette to transfer an aliquot to fresh liquid and solid media of the same type. This helps to purify the culture and confirm growth.

- Purification: Streak positive cultures on the corresponding solid medium to isolate single colonies. Be prepared for colonies to be microscopic.

Q4: How can I better monitor oligotrophic contaminants in my aseptic production facility?

Standard environmental monitoring using rich media like SCDA fails to detect the majority of oligotrophic bacteria. To effectively monitor them:

- Use Oligotrophic Media: Incorporate dilute, low-nutrient media such as Ravan medium alongside SCDA during routine settle plate, surface swab, and active air sampling [5].

- Extend Incubation Time and Temperature: Incubate oligotrophic media plates at 20-22°C for at least 28 days, as these organisms grow slower and prefer cooler temperatures than typical contaminants [5].

- Microscopic Colony Counting: A significant proportion of colonies on oligotrophic media are microscopic. Perform colony counts using a stereoscopic microscope (e.g., with a 4x objective) to avoid false negatives [5].

Q5: Are there any co-culture or symbiotic approaches that can help cultivate the most stubborn uncultivated taxa?

Yes, many yet-to-be-cultivated oligotrophs rely on metabolic interactions with other microbes. Strategies to leverage this include:

- Providing Helper Strains: Co-culture the target sample with known helper bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli or a Bacillus species) that can be separated by a membrane. The helper strain may provide essential growth factors like siderophores, vitamins, or signaling molecules [26].

- Using Conditioned Media: Culture helper strains first, filter-sterilize the spent medium, and use this "conditioned medium" to supplement the growth medium for the target oligotrophs. This provides necessary factors without direct competition [26].

- Studying Natural Consortia: As seen in oligotrophic Synechococcus-bacteria systems, tight metabolic interdependence exists. Isolating and studying these stable consortia before moving to axenic culture can be a successful path [6].

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Oligotrophic Bacteria Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Nutrient Media | Base for cultivation and isolation, mimicking natural oligotrophic conditions. | R2A Agar [26] [5], Ravan Medium [5], Soil Extract Agar [26]. |

| Environmental Extract | Provides unknown but essential growth factors from the original habitat. | Soil, sediment, or water from sampling site; filter-sterilized and used as medium supplement [26]. |

| Gellan Gum | Agar alternative for gelling media; less inhibitory for some sensitive oligotrophs. | Used at low concentration (e.g., 0.5-1.0%) to prepare solid media [26]. |

| Sterile Filtration Devices | For sterilizing heat-sensitive solutions and concentrating large volume water samples. | 0.22 µm pore size membrane filters [5]. |

| Microtiter Plates | For high-throughput cultivation via dilution-to-extinction and co-culture assays. | 96-well plates, sealed to prevent evaporation during long incubation [26]. |

| Signal Compounds | To resuscitate dormant cells or induce growth initiation in VBNC states. | Acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) or other quorum-sensing molecules [26]. |

| Chelex 100 Resin | To remove trace metal contaminants from media for studies on metal limitation. | Used to purify macronutrient solutions [6]. |

Advanced Cultivation and Detection Techniques for Reliable Oligotroph Recovery

Cultivating oligotrophic bacteria—microorganisms adapted to life in nutrient-poor environments—presents unique challenges for researchers in pharmaceutical development and environmental microbiology. Traditional rich media (e.g., standard Tryptic Soy Broth) often fail to support the growth of these organisms, leading to the "great plate count anomaly" where only a tiny fraction of microbial diversity can be cultured in the laboratory [28]. Media optimization addresses this problem by creating defined, low-nutrient formulations that closely mimic the natural conditions of oligotrophic habitats, enabling the study of previously unculturable microorganisms with potential significance for drug discovery and ecosystem research.

The fundamental principle behind this approach recognizes that organisms like the Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC), SAR11 clade, and various desert soil bacteria have evolved specialized metabolic strategies for survival in low-nutrient conditions [29] [14] [30]. When exposed to conventional laboratory media containing nutrient concentrations thousands of times higher than their native environments, these organisms may experience metabolic shock or be outcompeted by fast-growing copiotrophs. By systematically reducing nutrient levels and carefully selecting components, researchers can dramatically improve the recovery and growth of oligotrophic bacteria for scientific study.

Scientific Basis & Mechanisms

Microbial Transport Strategies in Oligotrophs

Oligotrophic bacteria employ distinct molecular mechanisms for nutrient uptake that differ fundamentally from those used by copiotrophs in nutrient-rich environments. Understanding these mechanisms provides the scientific foundation for designing effective low-nutrient media.

ABC Transport Systems vs. Phosphotransferase Systems (PTS) Prototypical oligotrophs predominantly rely on ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, which utilize binding proteins to scavenge scarce nutrients with high affinity [14]. In contrast, copiotrophs typically employ phosphotransferase systems (PTS) that are efficient in high-nutrient conditions but ineffective at low substrate concentrations. The ABC transport mechanism allows oligotrophs to achieve half-saturation concentrations over a thousand-fold lower than their binding protein's dissociation constant, but this comes with a trade-off: maintaining high abundances of slowly diffusing binding proteins requires large periplasms and precludes high growth rates [14]. This explains why oligotrophs grow slowly but dominate in nutrient-poor environments.

Carbon Concentrating Mechanisms (CCMs) In extremely low-carbon environments such as oceans, many oligotrophic microorganisms have evolved carbon concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) to enhance CO2 fixation [27]. These biological strategies actively accumulate cellular CO2, enabling metabolic processes that require higher concentrations than are available in the external environment. Similar concentrating strategies exist for other limited nutrients, including nitrogen and sulfate.

Table: Key Differences Between Oligotrophs and Copiotrophs

| Characteristic | Oligotrophs | Copiotrophs |

|---|---|---|

| Preferred nutrient level | Low (oligotrophic) | High (copiotrophic) |

| Primary transport system | ABC transporters | Phosphotransferase systems (PTS) |

| Nutrient affinity | High | Low to moderate |

| Growth rate | Slow | Fast |

| Periplasm size | Large | Small |

| Metabolic strategy | Efficient scavenging, conservation | Rapid uptake, utilization |

Environmental Adaptation and Nutrient Thresholds

Microorganisms from extremely low-nutrient environments like deserts or deep oceans exhibit specific adaptations that must be considered in media design. Research on Taklimakan Desert soils, which contain total organic carbon content generally less than 3.5 g/kg, demonstrates that microorganisms living long-term in nutrient-poor conditions often cannot withstand the pressure of high-nutrient environments [30]. The carbon content of common laboratory media (e.g., ~7.6 g/L for LB medium) far exceeds what these organisms encounter naturally.

Kuznetsov et al. defined oligotrophic bacteria as those capable of growth on media with a carbon content of 1–15 mg/L [30]. For context, dissolved organic carbon concentrations in groundwater, drinking water, and surface waters typically range from 0.5 to 5 mg/L, with assimilable organic carbon (AOC) present at just 10–100 μg/L [27]. Individual sugars or amino acids in these environments may not exceed a few μg/L [27]. These values provide critical reference points for formulating appropriate media concentrations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I simply use standard laboratory media like LB or TSB for oligotrophic bacteria?

Standard laboratory media such as LB (containing ~7.6 g/L carbon) and TSB create conditions that are metabolically incompatible with oligotrophic bacteria [30]. Organisms from low-nutrient environments (e.g., desert soils with <3.5 g/kg organic carbon) experience nutrient shock when exposed to these rich media. Furthermore, fast-growing copiotrophs that may be present in mixed samples will rapidly outcompete slow-growing oligotrophs in nutrient-rich conditions. Research shows that oligotrophic media with 1/10 or 1/100 strength of standard formulations yield significantly better recovery of these organisms [29] [28].

Q2: What nutrient concentration ranges are appropriate for oligotrophic media?

The optimal concentration range depends on your target organisms and their native environment. For general oligotrophic bacteria, Kuznetsov's definition of 1–15 mg/L carbon content provides a useful starting point [30]. In practice, successful media formulations include:

- Dilutions of standard media: 1/10 to 1/100 strength TSB or R2A [29] [28]

- Defined oligotrophic media: Carbon content not exceeding 50 mg/L for desert isolates [30]

- Seawater-based media: Using filtered natural seawater with minimal additions [28]

Q3: How long should I incubate cultures of oligotrophic bacteria?

Oligotrophic bacteria typically grow much slower than conventional laboratory strains. While copiotrophs may form visible colonies in 24-48 hours, oligotrophs often require extended incubation periods—from several days to several weeks [30]. Research indicates that visible colony formation for some slow-growing microorganisms may take up to 5 weeks [30]. Patience is essential, and plates should be monitored regularly for several weeks before discarding.

Q4: What are the most common problems when first attempting to culture oligotrophs?

The most frequent issues researchers encounter include:

- Overgrowth by contaminants: Even small numbers of fast-growing bacteria or fungi can overwhelm oligotrophic cultures.

- Incorrect nutrient levels: Media that is too rich inhibits growth; media that is too sparse provides insufficient nutrients.

- Inadequate incubation time: Discarding cultures too early before slow-growing colonies appear.

- Inoculum size too large: High cell densities can introduce excessive nutrients or create microenvironments that favor copiotrophs.

Q5: How can I determine if my low-nutrient media is working effectively?

Success can be evaluated through several indicators:

- Increased diversity of isolates compared to rich media

- Recovery of known oligotrophic taxa (e.g., SAR11, Sphingopyxis, certain Burkholderia species)

- Isolation of novel species not previously cultured

- Higher culturability percentages compared to standard methods

In quantitative terms, researchers have reported up to 14% culturability of coastal seawater samples using extinction culturing in low-nutrient media, compared to 0.01-0.1% with standard plating techniques [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: No Growth in Low-Nutrient Media

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Nutrient concentration too low for any microbial growth.

- Solution: Prepare a gradient of media with different nutrient levels (e.g., full strength, 1/10, 1/100, 1/1000) to identify the optimal concentration for your specific samples.

Cause: Incubation time insufficient.

- Solution: Extend incubation time to at least 3-8 weeks, regularly examining plates for microcolonies [30].

Cause: Inoculum size too small.

- Solution: Use extinction culturing methods with statistical dilution series rather than extreme dilution [28].

Cause: Essential co-factors or minerals missing from defined media.

- Solution: Add trace elements, vitamins, or small amounts of soil/water extracts from the native environment.

Problem: Overgrowth by Fast-Moving Organisms

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Contamination by motile, fast-growing bacteria.

- Solution: Incorporate low concentrations of inhibitors specific to common contaminants (if targeting specific groups), or use filtration to remove motile organisms.

Cause: Inoculum contains residual high-nutrient particles.

- Solution: Pre-wash or pre-filter samples to remove particulate matter that might create nutrient hotspots.

Cause: Cross-contamination during incubation.

- Solution: Ensure proper physical separation between plates and confirm sterility of humidification systems.

Problem: Only Known Species Grow, No Novel Isolates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Media still too nutrient-rich, favoring generalists.

- Solution: Further reduce nutrient concentrations or use diffusion chambers with environmental membranes.

Cause: Oxygen tension or atmospheric conditions not optimal.

- Solution: Experiment with different oxygen concentrations (microaerophilic conditions) or add CO2.

Cause: Missing specific signaling molecules or growth factors.

- Solution: Incorporate spent media from environmental samples or use co-culture approaches.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Extinction Culturing for Oligotrophic Bacteria

This protocol adapts high-throughput culturing (HTC) methods for isolating oligotrophic bacteria from water samples [28].

Materials:

- Environmental sample (water, soil suspension)

- Filtration apparatus with 0.2μm membranes

- Sterile oligotrophic media (filtered environmental water or diluted R2A/TSB)

- 48-well non-tissue culture treated plates

- DAPI stain and fluorescence microscopy equipment

- PCR reagents for 16S rRNA amplification and sequencing

Procedure:

- Collect environmental sample using sterile techniques.

- Filter sample through 0.2μm membrane to remove particulates while retaining bacteria.

- Prepare oligotrophic media: either use filtered, autoclaved environmental water with bicarbonate restoration, or create diluted standard media (e.g., 1/10 R2A or 1/10 TSB) [28].

- Perform serial dilutions of the sample to achieve a theoretical concentration of 1-10 cells per ml.

- Dispense 1ml aliquots into 48-well plates.

- Incubate in the dark at environmental temperature (e.g., 16°C for marine samples) for extended periods (3-8 weeks).

- Screen for growth using sensitive detection methods such as DAPI staining and fluorescence microscopy.

- Subculture positive wells and identify isolates via 16S rRNA sequencing.

Protocol: Gradient Media Preparation for Desert Soil Isolates

This protocol describes the preparation of nutrient gradient media for cultivating oligotrophic bacteria from desert soils [30].

Materials:

- Soil sample from arid environment

- Standard media powders (LB, R2A, Gao's No. 1)

- Distilled water

- Trace salt mother liquor (1g/1000mL each of ferrous sulfate, zinc sulfate, and manganese chloride)

- pH meter and adjustment solutions

- Petri dishes

Procedure:

- Prepare basal media according to standard recipes (LB, R2A, or Gao's No. 1).

- Add 1000μL trace salt mother liquor to each 1000mL of media.

- Adjust pH to match environmental conditions (e.g., pH 8.5 for desert soils).

- Prepare dilution series:

- Eutrophic: 1/2, 1/5, 1/10, 1/15 strength

- Mesotrophic: 1/20, 1/30 strength (LB) or 1/2, 1/5 strength (R2A)

- Oligotrophic: 1/50, 1/100 strength and lower

- Pour plates and allow to solidify.

- Prepare soil suspensions by suspending 1g soil in 10mL sterile water.

- Spread 50-100μL of soil suspension (or appropriate dilutions) onto plates.

- Incubate at environmental temperature for up to 8 weeks, regularly monitoring for colony formation.

Table: Media Formulations for Oligotrophic Bacteria Isolation

| Media Type | Composition | Carbon Content | Target Organisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/10 TSB | 0.3g TSB powder per 100mL water | ~0.3 g/L | Burkholderia cepacia complex, Stenotrophomonas | [29] |

| Seawater-based | Filtered, autoclaved seawater with bicarbonate restoration | ~0.1 g/L | SAR11, marine oligotrophs | [28] |

| Diluted R2A | 1/10 to 1/100 strength R2A | 0.1-0.5 g/L | Diverse oligotrophs from various environments | [30] [28] |

| Desert oligotrophic | LB diluted to 1/50-1/100 strength | <0.05 g/L | Taklimakan Desert isolates | [30] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Oligotrophic Media Preparation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Media | Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), Reasoner's 2A Agar (R2A), Gao's No. 1 | Base for diluted media formulations | Dilute to 1/10 to 1/100 strength for oligotrophic work [29] [30] |

| Trace Elements | Ferrous sulfate, Zinc sulfate, Manganese chloride | Provide essential micronutrients | Add as mother liquor (1g/L each) at 1mL/L final concentration [30] |

| Gelling Agents | Purified agar, Agarose | Solidify media while minimizing nutrient introduction | Use purified forms to avoid introducing organic nutrients |

| Water Sources | Filtered environmental water, Milli-Q water | Base for defined media | Environmental water preserves native ion composition [28] |

| Carbon Sources | Sodium pyruvate, Acetate, Succinate | Defined carbon supplements | Use at micromolar concentrations for defined media |

| pH Buffers | HEPES, MOPS, Phosphate buffers | Maintain pH stability in dilute media | Choose buffers compatible with low nutrient conditions |

Advanced Techniques & Future Directions

Machine Learning for Media Optimization

Recent advances apply machine learning to predict optimal media compositions for specific microorganisms. By analyzing 16S rRNA sequences and known growth characteristics across 2,369 media types, researchers have developed classification models that can predict with 76-99.3% accuracy whether a bacterium will grow in a particular medium [31]. This approach, implemented in tools like MediaMatch, uses the XGBoost algorithm with 3-mer frequencies from 16S rRNA sequences as features to make predictions [31]. As these databases grow, this methodology promises to significantly reduce the trial-and-error aspect of media optimization.

High-Throughput Culturing (HTC) Methods

High-throughput methods enable the screening of thousands of culture attempts simultaneously. The core HTC approach involves [28]:

- Using microtiter plates to culture cells in small volumes (200μL-1mL) of low-nutrient media

- Creating cell arrays for efficient screening of plates for growth

- Applying detection methods sensitive enough to identify cultures with densities as low as 1.3×10^3 cells/mL

- Automating identification processes through 16S rRNA analysis

This methodology has demonstrated 14-fold to 1,400-fold higher culturability compared to traditional techniques for marine bacterioplankton [28].

Synthetic Community and Co-culture Approaches

Many oligotrophic bacteria depend on metabolic interactions with other community members. Co-cultivation with helper strains can enhance growth through beneficial interactions [32]. Similarly, adding spent culture media from established cultures can provide growth stimulants that are difficult to identify and include in defined formulations [32]. These approaches recognize that pure culture isolation may require initial cultivation in synthetic communities followed by gradual simplification.

High-throughput dilution-to-extinction cultivation is a powerful methodological framework designed to overcome a fundamental challenge in microbiology: the isolation of a diverse range of microorganisms, particularly slow-growing and oligotrophic bacteria, from complex environmental samples. This approach involves creating a series of high dilutions of a microbial sample in liquid growth medium, which are then dispensed into multi-well plates. At the appropriate dilution factor, many wells receive either zero or one microbial cell, enabling the growth of axenic cultures from single cells and preventing overgrowth by fast-growing species [33] [34].

The power of this technique lies in its ability to systematically recover microbial taxa that are often overlooked by traditional agar-plating methods. By optimizing nutrient concentrations to match the requirements of oligotrophic bacteria—organisms adapted to low-nutrient environments—researchers can significantly expand the range of cultivable diversity [34]. This protocol has proven particularly valuable for isolating plant-associated microbiota [34], marine bacteria [35], and other environmental microbes that have remained unculturable using conventional methods.

When integrated with next-generation sequencing and automated liquid handling systems, dilution-to-extinction becomes a high-throughput platform for building comprehensive microbial culture collections. These collections are essential for synthetic community design, functional screening, and advancing our understanding of microbial ecology [35].

Core Concepts and Scientific Principles

Oligotrophic vs. Copiotrophic Lifestyles

Microorganisms exhibit distinct metabolic strategies along a spectrum defined by nutrient availability. Understanding this dichotomy is fundamental to optimizing dilution-to-extinction cultivation.

Oligotrophs are adapted to chronically low-nutrient environments (e.g., open ocean, drinking water systems) and possess several distinguishing characteristics:

- Slow growth rates with doubling times often exceeding 5 hours [14]

- Small cell sizes (typically < 0.1 μm³) and streamlined genomes [14]

- High-affinity nutrient uptake systems, primarily ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters with periplasmic binding proteins [14]

- Non-motile lifestyles in prototypical forms like SAR11 [14]

Copiotrophs dominate nutrient-rich environments (e.g., nutrient pulses, root exudates) and display contrasting features:

- Rapid growth rates with doubling times under one hour during nutrient availability [14]

- Larger cell volumes (often > 1 μm³) [14]

- Diverse transport systems including numerous phosphotransferase systems (PTS) for sugar uptake [14]

- Motility adaptations to locate and colonize nutrient-rich patches [14]

The dilution-to-extinction method creates conditions that favor oligotrophs by minimizing competition from fast-growing copiotrophs through physical separation in high-dilution wells [33] [34].

Mechanistic Basis of High-Affinity Nutrient Uptake

Oligotrophs achieve remarkable nutrient scavenging capabilities through specialized transport mechanisms. The ABC transporter systems employed by oligotrophs differ fundamentally from the PTS systems common in copiotrophs [14].

Table: Comparison of Microbial Nutrient Transport Strategies

| Feature | ABC Transporters (Oligotrophs) | PTS Systems (Copiotrophs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Users | SAR11, sphingomonads | Vibrios, enteric bacteria |

| Energy Source | ATP hydrolysis | Phosphoenolpyruvate |

| Key Components | Periplasmic binding protein + transmembrane unit | Enzyme II complex |

| Affinity Tuning | Depends on binding protein abundance | Intrinsic transporter property |

| Half-Saturation Constant | Can reach nanomolar range | Typically micromolar or higher |

| Metabolic Cost | Higher due to ATP hydrolysis and protein synthesis | Lower per transport event |

| Growth Rate Trade-off | High affinity precludes fast growth | Optimized for rapid nutrient conversion |

The kinetic model of ABC transport reveals that the specific affinity is proportional to binding protein abundance when the binding protein to transport unit ratio is sufficiently high [14]. This allows oligotrophs to achieve half-saturation concentrations over a thousand-fold smaller than their binding proteins' dissociation constants. However, this high-affinity strategy requires substantial proteomic investment and large periplasms to accommodate abundant binding proteins, which diffusional constraints ultimately limit growth rates [14].

Diagram: Microbial Lifestyle Dichotomy and Cultivation Implications - This diagram illustrates the fundamental relationships between environmental nutrient conditions, microbial transport systems, and growth strategies that inform dilution-to-extinction cultivation design.

Complete Experimental Protocols

High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation from Field-Grown Crops

This protocol has been optimized for isolating root-associated bacteria from field-grown plants such as corn (Zea mays) and peas (Pisum sativum) [33] [35].

Sample Preparation and Dilution Series

- Sample Collection: Collect root samples with intact rhizosphere soil. Transport on ice and process within 24 hours [35].

- Root Slurry Preparation: Remove loosely associated microbes with sequential PBS washes. Cut and grind plant tissues into a slurry using sterile mortar and pestle [35].

- Serial Dilution: Perform threefold serial dilutions of the root slurry in dilute nutrient medium (e.g., 10% Tryptic Soy Broth). Begin with an initial 2000× dilution and extend to 486,000× final dilution [35].

- Plate Inoculation: Dispense 100-200 μL of each dilution into sterile 96-well plates. Include negative controls (sterile medium only) on each plate [33].

Incubation and Growth Monitoring

- Incubation Conditions: Seal plates with gas-permeable membranes or Parafilm to prevent evaporation. Incubate at room temperature (22-25°C) for 12 days [35].

- Growth Assessment: Monitor well turbidity visually or using plate readers at 3-day intervals. Ideal plates show 18-55% of wells with growth [35].

- Culture Preservation: Transfer aliquots from positive wells to new plates for identification. Add sterile glycerol to remaining culture (40% final concentration) and store at -80°C [35].

Two-Step Barcoded PCR and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

This identification protocol enables high-throughput taxonomic characterization of bacterial isolates [35].

DNA Extraction and Primary PCR

Alkaline Lysis DNA Extraction:

- Transfer 5-10 μL of bacterial culture to PCR plates

- Add 10-20 μL of alkaline lysis buffer (25 mM NaOH, 0.2 mM Na2-EDTA)

- Incubate at 95°C for 30 minutes, then neutralize with 10-20 μL Tris-HCl (40 mM, pH 7.5) [35]

Primary PCR Amplification:

- Use barcoded primers targeting V4 region of 16S rRNA gene (V4515F and V4805R)

- Each well receives unique forward (column-specific) and reverse (row-specific) barcode combination

- Reaction setup: 2× KAPA HotStart ReadyMix, 0.5 μM each primer, 2 μL DNA template

- Cycling: 95°C for 3 min; 26 cycles of [95°C for 30s, 55°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s]; 72°C for 5 min [35]

Pooling, Secondary PCR and Sequencing

- PCR Product Pooling: Combine 5 μL from each of the 96 wells. Purify using magnetic beads (e.g., Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS) [35].

- Secondary PCR: Amplify 2 μL purified product with Nextera primers for Illumina sequencing (9 cycles using same conditions as primary PCR) [35].

- Library Preparation: Purify PCR products, quantify using PicoGreen assay, pool in equimolar amounts, and sequence on Illumina MiSeq platform [35].

Diagram: High-Throughput Cultivation and Identification Workflow - This diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow from sample processing through bacterial identification.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Technical Issues and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| No bacterial growth in wells after incubation [33] | Over-dilution of bacterial suspension; unsuitable growth medium; metabolic dormancy | Reduce dilution factor; increase starting inoculum; extend incubation time; test alternative media | Conduct pilot dilution series; include medium controls with known cultivable strains |

| Excessive growth in all wells, including high dilutions [33] | Bacterial concentration too high; contamination with fast-growing species | Prepare more diluted suspension before plating; implement stricter aseptic technique | Verify sterility of media and diluents; use fresh dilution tubes for each step |

| Cross-contamination between wells [33] | Splashing during pipetting; aerosol contamination; poorly sealed plates | Use slow, controlled pipetting; centrifuge plates before opening; ensure proper sealing | Use barrier pipette tips; work in laminar flow hood; seal plate edges thoroughly with Parafilm |

| Drying of medium in border wells [33] | Evaporation due to inadequate sealing; prolonged incubation | Replenish with sterile water; tighten plate sealing; reduce incubation time if possible | Use plates with evaporation rings; add extra sealing tape to edges; maintain consistent humidity |

| DNA degradation after extraction [33] | Overheating during alkaline lysis; nuclease contamination | Ensure incubation at 95°C does not exceed 30 minutes; use nuclease-free reagents | Aliquot lysis reagents to minimize freeze-thaw cycles; include DNA quality controls |

| No visible PCR product on gel electrophoresis [33] | PCR inhibitors from microbiome; insufficient template; primer degradation | Dilute DNA template 1:10; purify DNA using cleanup kit; verify primer quality | Include PCR positive controls; test primer aliquots before use; optimize template concentration |

| Unexpected bands or smearing in gel electrophoresis [33] | Non-specific amplification; primer-dimer formation; contaminated reagents | Increase annealing temperature; optimize primer concentration; use fresh polymerase | Perform gradient PCR for annealing optimization; prepare fresh reaction mixes |

| Negative control shows amplification [33] | Contamination in PCR reagents; amplicon carryover | Use fresh reagents and nuclease-free water; work in dedicated PCR workspace | Set up reactions in UV-treated hood; use separate areas for pre- and post-PCR |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the ideal percentage of wells with growth for maximizing isolate diversity? A: Plates with 18-55% of wells showing growth typically provide the best balance between maximizing diversity and minimizing multiple strains per well. Plates with >80% growth indicate insufficient dilution, while <10% suggests over-dilution [35].

Q: How does dilution-to-extinction compare with traditional agar plating for isolating diverse microbiota? A: The methods are complementary. Studies on oak microbiota found only 12% of ASVs were detected by both methods, with each approach capturing distinct fractions of the microbial community. Combining both methods significantly increases taxonomic richness of culture collections [34].

Q: What are the key limitations of dilution-to-extinction cultivation? A: Major limitations include: (1) restriction to liquid-medium adapted microbes, (2) aerobic bias unless modified, (3) potential underrepresentation of slow-growing and fastidious bacteria, (4) disruption of microbial interactions essential for some species, and (5) selective bias introduced by the growth medium [33].

Q: Why might oligotrophic bacteria fail to grow even in dilute nutrient media? A: Oligotrophs may require specific nutrient ratios or growth factors not present in standard media. Some may depend on metabolic byproducts from other microbes (syntrophy). Testing ultra-dilute media (e.g., 0.1X concentration) and incorporating site-specific amendments (e.g., plant extracts) can improve recovery [34].

Q: How can I optimize nutrient concentrations for specific oligotrophic target organisms? A: Employ high-throughput screening systems like PhotoBiobox [36] or automated nutrient screening [37] to test multiple nutrient concentrations simultaneously. Box-Behnken experimental designs can efficiently optimize multiple nutrients across a broad statistical space with reduced experimental runs [37].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) | Base nutrient medium for bacterial growth | Use at 10% concentration for oligotrophs; full strength for copiotrophs [33] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Sample washing and dilution buffer | Maintains osmotic balance; prevents cell lysis during processing [34] |

| Glycerol | Cryopreservation agent | 40% final concentration for -80°C storage; ensures culture viability [35] |

| Magnesium Chloride Hexahydrate | Enzyme cofactor in lysis buffer | Component of alkaline lysis buffer (25 mM NaOH, 0.2 mM Na2-EDTA) [33] |

| KAPA HotStart Polymerase | High-fidelity PCR amplification | Reduced non-specific amplification in 16S rRNA gene sequencing [35] |

| Mag-Bind TotalPure NGS Beads | PCR product purification | Magnetic bead-based clean-up before sequencing; size selection capability [33] |

| Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay | DNA quantification for library pooling | Fluorometric measurement for accurate equimolar pooling [33] |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Sequencing library preparation | Illumina-compatible library construction with dual indexing [35] |

| Gas-Permeable Sealing Membranes | Plate sealing during incubation | Prevents evaporation while allowing gas exchange [36] |

| 96-Well PCR Plates | High-throughput molecular work | Compatibility with thermal cyclers and liquid handling systems [33] |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Nutrient Optimization Strategies for Oligotrophs

Successful cultivation of oligotrophic bacteria requires careful consideration of nutrient composition and concentration. Several advanced approaches can enhance recovery:

High-Throughput Nutrient Screening: Automated systems like PhotoBiobox enable efficient testing of multiple carbon sources, temperatures, and nutrient concentrations [36]. For microalgae, a two-step screening process first identifies suitable organic substrates, then optimizes concentration and temperature conditions [36].

Box-Behnken Experimental Designs: These incomplete factorial designs compress the statistical search space dramatically. For example, optimizing 10 elements at 3 concentrations would require 59,049 full factorial conditions, but a Box-Behnken design can reduce this to 180 trials while still identifying main effects and pairwise interactions [37].

Chemical Environment Modeling: Consider the bioavailability of each element, which depends on factors such as solubility, chemical speciation, pH, ionic strength, and interaction with other elements. Nutrient deficiencies limit growth, but excess nutrients can cause toxicity, precipitation, or wastage through opportunistic uptake [37].

Integrating Cultivation with Culture-Independent Methods

Dilution-to-extinction cultivation should be viewed as complementary to, rather than competitive with, culture-independent approaches:

Capturing Rare Taxa: Isolation-based approaches can detect microorganisms not detected by culture-independent analysis, particularly enriching low-abundant taxa that may be functionally important but numerically rare in community profiling [34].

Validation of Metagenomic Predictions: Cultured isolates provide definitive validation of metabolic capabilities predicted from metagenome-assembled genomes and enable functional testing of hypotheses generated from sequencing data [35].

Synthetic Community Design: Isolated strains serve as building blocks for reduced-complexity synthetic communities (SynComs), enabling mechanistic studies of microbial interactions and community assembly [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is full-strength Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) often unsuitable for cultivating oligotrophic bacteria?

Full-strength TSB, a nutrient-rich medium, is designed for fast-growing copiotrophic bacteria. Its use for oligotrophs often leads to poor recovery because of fundamental physiological trade-offs. Oligotrophs are specialized for survival in low-nutrient conditions and possess transport systems optimized for high-affinity nutrient uptake at the expense of rapid growth [14] [38]. When exposed to high nutrient concentrations, several issues can occur:

- Metabolic Imbalance: The sudden influx of nutrients can overwhelm the oligotroph's metabolic capacity, leading to toxic byproduct accumulation or oxidative stress [14].