Overcoming the Barrier: Strategies for Efficient CRISPR Delivery in EPS-Rich Matrices

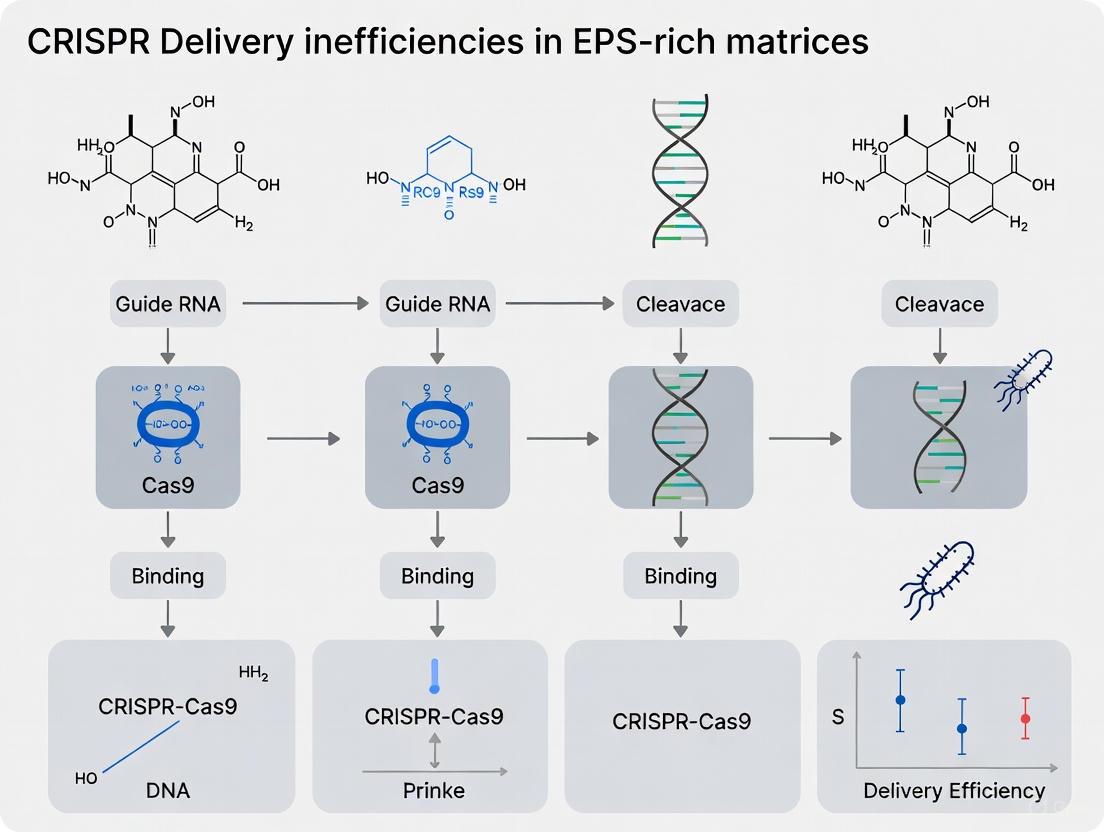

The therapeutic application of CRISPR-Cas9 technology is significantly hampered by inefficient delivery, particularly within extracellular polymeric substance (EPS)-rich matrices like bacterial biofilms and certain tumor microenvironments.

Overcoming the Barrier: Strategies for Efficient CRISPR Delivery in EPS-Rich Matrices

Abstract

The therapeutic application of CRISPR-Cas9 technology is significantly hampered by inefficient delivery, particularly within extracellular polymeric substance (EPS)-rich matrices like bacterial biofilms and certain tumor microenvironments. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the fundamental challenges posed by EPS, reviewing innovative delivery platforms from viral vectors to nanoparticles, and offering practical optimization strategies. We further synthesize methods for validating delivery efficiency and editing success, presenting a consolidated framework to advance the translation of CRISPR-based therapies against resilient, matrix-protected cellular communities.

The EPS Barrier: Understanding the Fundamental Challenges to CRISPR Delivery

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guide

This support center is designed for researchers tackling the challenge of CRISPR-Cas9 delivery within EPS-rich matrices, a common barrier in biofilm and tumor microenvironment research. The FAQs below address specific, high-priority experimental issues.

FAQ 1: Why is my CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency so low in EPS-rich environments like bacterial biofilms?

The Challenge: EPS matrices act as a formidable physical and chemical barrier. The extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), including exopolysaccharides, proteins, and extracellular DNA (eDNA), significantly hinder the diffusion and uptake of CRISPR-Cas9 delivery vectors [1] [2].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Characterize the EPS Barrier:

- Action: Quantify the major components of your specific EPS-rich matrix (e.g., uronic acid content for polysaccharides, eDNA concentration). High uronic acid and eDNA content are known to chelate particles and increase viscosity [1].

- Rationale: Understanding the specific composition allows for a targeted disruption strategy.

Pre-treat to Perturb the EPS Matrix:

- Action: Implement a mild pre-treatment step to disrupt the matrix without killing the cells. Consider using enzymes like:

- DNase I: Degrades eDNA, a key structural component [2].

- Dispersin B: Hydrolyzes polysaccharides in some biofilms.

- Protocol Note: Treat the biofilm with a suitable concentration of enzyme (e.g., 10-100 µg/mL DNase I in PBS) for 1-2 hours at 37°C prior to delivering the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Always include a no-enzyme control to confirm the effect is due to matrix disruption.

- Action: Implement a mild pre-treatment step to disrupt the matrix without killing the cells. Consider using enzymes like:

Switch to a Smaller Delivery Vehicle:

- Action: If using viral vectors (e.g., AAV), which can be filtered by the EPS mesh, consider switching to physically compact ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes of Cas9 protein and sgRNA [3].

- Rationale: Pre-assembled RNP complexes are significantly smaller than plasmids and can diffuse more readily through the matrix, often resulting in higher editing efficiency and reduced off-target effects [3].

FAQ 2: How can I accurately measure the penetration efficiency of my CRISPR delivery system into a 3D biofilm?

The Challenge: Visualizing and quantifying the distribution of CRISPR carriers within a dense, three-dimensional structure is non-trivial.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use a Fluorescent Proxy:

- Action: Label your delivery vehicle (e.g., lipid nanoparticles with a fluorescent dye, or use a fluorescently tagged Cas9 protein) with a stable, bright fluorophore (e.g., Cy5, ATTO 647N).

- Employ Confocal Microscopy and Quantitative Analysis:

- Action: Acquire z-stack images of the biofilm using a confocal laser scanning microscope. Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ/Fiji) to create a depth-intensity profile.

- Protocol Note:

- Embed and cryosection the biofilm if needed for higher resolution imaging.

- Measure the fluorescence intensity at various depths (e.g., every 10 µm) from the surface inward.

- Calculate the Penetration Efficiency as the percentage of fluorescence intensity retained at a target depth (e.g., 50 µm) compared to the surface intensity. A significant drop in intensity indicates poor penetration.

FAQ 3: What are the best strategies to increase HDR-mediated knock-in efficiency for precise gene editing in these challenging systems?

The Challenge: The non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway dominates in most somatic cells, leading to stochastic indels rather than precise knock-in, and this can be exacerbated in slow-growing or stressed cells within EPS matrices [4].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Synchronize the Cell Cycle:

- Action: For in vitro models, synchronize your cells at the S/G2 phase of the cell cycle, where the HDR machinery is most active [4].

- Protocol Note: Use chemical agents like thymidine or nocodazole for synchronization before delivering the CRISPR-Cas9 system and the donor DNA template.

Utilize HDR-Enhancing Reagents:

- Action: Supplement your culture medium with small molecule enhancers of HDR.

- Rationale: Compounds like RS-1 (an RAD51 stimulator) or L755507 can increase HDR efficiency by several-fold. A recommended starting concentration is 5-10 µM for RS-1, added during or shortly after CRISPR delivery [4].

Optimize the Donor Template Design:

- Action: For best results, use single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) with homology arms of 35-90 nt for point mutations, or double-stranded DNA templates with ~800 nt homology arms for larger insertions. Incorporating the silent CRISPR-resistant (SCR) mutations into the donor template can prevent re-cleavage after successful HDR [4].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative information from the literature to aid in experimental planning and comparison.

Table 1: Key Components and Functions of a Model Bacterial Biofilm (P. aeruginosa)

| Component | Approximate Percentage (%) | Primary Function in EPS Matrix |

|---|---|---|

| Exopolysaccharides | 1 - 2 | Maintains structural integrity and stability of the biofilm [2] |

| Proteins & Enzymes | < 1 - 2 | Provides surface colonization and structural stability [2] |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | < 1 - 2 | Promotes biofilm formation and protects against host immune responses [2] |

| Water | Up to 97 | Hydrates the biofilm, preventing desiccation [2] |

Table 2: Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Strategies

| Delivery Method | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Best Suited for EPS-Rich Environments? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNA | Simple to use, stable long-term expression [3] | Large size, difficult to diffuse; requires nuclear entry [3] | No |

| Cas9 mRNA + sgRNA | Reduced immune response vs. plasmid; no nuclear entry needed [3] | Lower stability; requires cytoplasmic translation [3] | Possibly |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Smallest size; fastest action; lowest off-target effects [3] | Technically more complex to deliver; transient activity [3] | Yes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials and their specific functions for conducting CRISPR-Cas9 experiments in EPS-rich contexts.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Work in EPS-Rich Matrices

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| DNase I | An enzyme that degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA), a critical scaffold component in many biofilms. Used to pre-treat matrices to enhance carrier penetration [2]. |

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | The core component for forming pre-assembled RNP complexes. Using the protein directly avoids the need for transcription/translation, speeding up editing and facilitating delivery [3]. |

| RS-1 | A small-molecule agonist of the RAD51 protein. It stimulates the Homology Directed Repair (HDR) pathway, thereby increasing the efficiency of precise knock-in edits [4]. |

| Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX | A commercially available lipid nanoparticle transfection reagent specifically optimized for the delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 RNP complexes into a wide range of cell types. |

| Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) | A short, sequence-specific motif (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) adjacent to the target DNA site that is essential for Cas9 recognition and binding [3]. |

Experimental Workflows & Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams, created using DOT language, illustrate key experimental workflows and molecular relationships relevant to this field.

CRISPR HDR Enhancement Workflow

CRISPR-Cas9 Molecular Mechanism

EPS Barrier to Delivery

The Composition and Physicochemical Properties of EPS that Hinder Drug Delivery

This technical support guide addresses the significant challenge that Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) pose to the efficient delivery of therapeutic agents, with a specific focus on advancing CRISPR-based technologies. The EPS matrix, a complex biobarrier surrounding microbial communities and present in various biological systems, severely limits treatment efficacy for conditions ranging from bacterial biofilms to certain human diseases. This document provides researchers and drug development professionals with targeted troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to overcome these delivery obstacles.

Understanding the EPS Barrier

What is the EPS and why is it a major hurdle for drug delivery?

Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) are a self-produced, hydrated polymeric network that forms a protective matrix around microbial cells [5]. This matrix is a primary reason for the inherent resistance of biofilm-associated infections to conventional antimicrobial therapies [5]. Its complex composition and structure create a formidable physical and chemical barrier that hinders the penetration of therapeutic molecules, including CRISPR/Cas systems.

FAQ: What are the key components of EPS and how do they specifically hinder drug delivery?

The following table summarizes the primary components of the EPS and their specific roles in hindering drug delivery.

Table 1: Key EPS Components and Their Roles in Hindering Drug Delivery

| EPS Component | Primary Function in Hindrance | Impact on Delivery Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | Forms a dense physical hydrogel matrix; acts as a molecular sieve [5]. | Limits diffusion based on size and charge; filters large complexes like CRISPR/Cas RNPs [6]. |

| Proteins | Contributes to structural integrity and adhesion; can bind nonspecifically to delivery vectors [6]. | Causes sequestration of therapeutics; depletes the dose before it reaches target cells. |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Provides structural scaffold and contributes to negative charge of the matrix [5]. | Traps cationic delivery vectors via electrostatic interactions; increases viscosity. |

| Lipids & Other Polymers | Influences hydrophobicity and surface properties of the matrix [6]. | Creates a partition barrier for hydrophobic/hydrophilic drugs; reduces permeability. |

Quantitative Data on Delivery Challenges and Nano-Solutions

FAQ: Is there quantitative evidence showing how much EPS reduces efficacy?

Yes, studies demonstrate that biofilms can exhibit up to 1000-fold greater tolerance to antibiotics compared to free-floating (planktonic) cells, largely due to the barrier function of the EPS [5]. This underscores the critical need for delivery systems that can effectively penetrate this barrier.

FAQ: How can nanoparticle properties be optimized to overcome EPS barriers?

The design of nanoparticles (NPs) is critical for enhancing penetration through the EPS matrix. Key physicochemical properties can be tuned to improve performance, as shown in the table below.

Table 2: Optimizing Nanoparticle Properties for EPS Penetration

| Nanoparticle Property | Optimization Strategy | Effect on EPS Penetration |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Maintain small hydrodynamic diameter (typically < 100 nm). | Facilitates diffusion through the porous EPS network [7]. |

| Surface Charge | Use a neutral or slightly negative surface charge (e.g., via PEGylation). | Reduces non-specific binding to negatively charged eDNA and polysaccharides in the EPS [7]. |

| Surface Functionality | Graft with enzymes (e.g., DNase, dispersin B) or biofilm-disrupting peptides. | Actively degrades specific EPS components (e.g., eDNA), creating paths for diffusion [6]. |

| Hydrophobicity | Balance to ensure compatibility with the EPS microenvironment. | Prevents unwanted aggregation within the matrix and aids in crossing lipid-rich domains. |

Recent advances show that lipid-based nanoparticles with optimized cholesterol density can significantly improve mRNA uptake and endosomal escape, which is crucial for delivering CRISPR components [8]. Furthermore, liposomal Cas9 formulations have been shown to reduce Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro, while CRISPR-gold nanoparticle hybrids demonstrated a 3.5-fold increase in gene-editing efficiency compared to non-carrier systems [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

Problem: Low CRISPR editing efficiency in EPS-rich environments.

- Potential Cause 1: The CRISPR cargo (RNP, plasmid) is too large and/or is being sequestered by the EPS matrix.

- Solution: Consider using smaller Cas orthologs (e.g., Cas12f) and deliver as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex to avoid the need for transcription/translation steps required by viral delivery [9]. Utilize nanoparticle carriers like polymeric PLGA or lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) designed for enhanced penetration [7] [8].

- Potential Cause 2: The delivery vehicle aggregates within the EPS, failing to reach target cells.

- Potential Cause 3: The guide RNA (gRNA) is degraded before reaching the target site.

Problem: Inconsistent results when testing anti-biofilm formulations.

- Potential Cause: Use of oversimplified or non-standardized in vitro biofilm models that do not replicate the EPS complexity of natural biofilms.

- Solution: Employ established, mature biofilm models (e.g., flow-cell systems, colony biofilms) that allow for full EPS development. Characterize the EPS composition (e.g., via carbohydrate and protein assays, CLSM with EPS-binding dyes) of your specific model to better correlate with delivery outcomes [5].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their functions for developing and testing delivery systems against EPS barriers.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for EPS and Delivery Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | A biodegradable polymer for creating nanoparticles that can encapsulate CRISPR components and cross biological barriers like the BBB, relevant for EPS-rich niches [7]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Versatile carriers for mRNA and sgRNA; cholesterol content can be tuned to optimize cellular uptake and endosomal escape in target cells like dendritic cells [8]. |

| Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) | Natural, biocompatible delivery vectors with low immunogenicity; can be engineered for targeted delivery of CRISPR machinery [7] [10]. |

| DNase I | Enzyme used to degrade eDNA within the EPS, reducing matrix integrity and viscosity to enhance nanoparticle penetration [6]. |

| Concanavalin A (ConA) & Other Lectins | Fluorescently labeled lectins used in Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) to visualize and quantify polysaccharide distribution in biofilms [5]. |

| SYTO Stains | Cell-permeant nucleic acid stains used in conjunction with CLSM to quantify bacterial cell biomass and spatial distribution within the EPS matrix [5]. |

Standard Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Nanoparticle Penetration through EPS

This protocol outlines a standard method for visually assessing the penetration efficiency of a nanoparticle formulation through a pre-formed biofilm.

Title: Protocol for Visualizing Nanoparticle Penetration in a Biofilm using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

Objective: To quantify the distribution and penetration depth of a fluorescently labeled nanoparticle delivery vehicle within an EPS-rich biofilm.

Workflow Diagram:

Materials:

- Bacterial strain of interest.

- Relevant growth medium.

- Sterile glass-bottom dishes or coverslips.

- Fluorescently labeled nanoparticle formulation (e.g., labeled with Cy5, FITC).

- SYTO stain (e.g., SYTO 9 for live cells).

- Optional: Lectin probes (e.g., ConA-TRITC for polysaccharides).

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope.

Procedure:

- Biofilm Growth: Grow a mature biofilm (e.g., for 48-72 hours) on a sterile glass substrate under appropriate conditions.

- NP Incubation: Gently introduce the fluorescent nanoparticle suspension to the biofilm and incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 2-4 hours).

- Washing: Carefully wash the biofilm with a buffer (e.g., PBS) to remove any nanoparticles that have not associated with or penetrated the biofilm.

- Staining: Stain the biofilm components. A common approach is to use SYTO 9 to stain all bacterial cells, providing a reference structure.

- Imaging: Acquire Z-stack images (optical sections from the top to the bottom of the biofilm) using a CLSM. Use appropriate laser lines and filters to avoid cross-talk between fluorescent signals.

- Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Imaris) to:

- Measure the penetration depth of the nanoparticle signal relative to the total biofilm thickness.

- Analyze the co-localization of the nanoparticle signal with bacterial cells to infer delivery to targets.

Visualizing the EPS Barrier and Strategic Solutions

The following diagram synthesizes the primary challenges posed by the EPS and the corresponding strategic solutions discussed in this guide.

Diagram Title: EPS Barrier Mechanisms and Strategic Solutions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary barriers that hinder CRISPR cargo delivery within EPS-rich matrices, and how can they be overcome? The main barriers in EPS-rich matrices like bacterial biofilms are limited diffusion, nuclease degradation, and inefficient cellular uptake. The dense, anionic extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) physically blocks nanoparticle penetration, while nucleases in the environment can degrade CRISPR components before they reach target cells [11]. Overcoming these requires engineered delivery vehicles; nanoparticles, particularly lipid-based and metallic ones, can be designed to shield CRISPR machinery and enhance diffusion through these protective layers [11] [9]. Co-delivery strategies that combine CRISPR with biofilm-disrupting agents can also synergistically improve access to bacterial cells [11].

FAQ 2: My CRISPR editing efficiency is low in biofilm-forming bacteria. Is this due to poor cargo delivery, and how can I confirm this? Yes, low editing efficiency is frequently a delivery problem in biofilms. The protective biofilm matrix can reduce antibiotic efficacy by up to 1000-fold compared to planktonic cells, and it similarly impedes CRISPR cargo delivery [11]. To confirm, you can use a CRISPR system with a fluorescent reporter; low fluorescence in target cells indicates poor delivery. Furthermore, you can employ the GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit to verify if cleavage is occurring on the endogenous genomic locus, which helps distinguish between delivery failure and functional failure of the CRISPR system itself [12].

FAQ 3: How can I protect CRISPR ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) from degradation during delivery? Encapsulating RNPs within nanoparticles offers significant protection. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and gold nanoparticles form a physical barrier that shields the cargo from nucleases in the extracellular environment [11] [13] [9]. A recently developed strategy uses Lipid Nanoparticle Spherical Nucleic Acids (LNP-SNAs), where a dense shell of DNA further protects the CRISPR core and enhances stability [14]. Using RNP complexes instead of plasmid DNA also minimizes the time the component is exposed to and vulnerable to nucleases, as they are active immediately upon delivery [9].

FAQ 4: Which delivery systems are most effective for improving cellular uptake of CRISPR cargo in difficult-to-transfect cells? Viral vectors, like adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), are efficient but raise safety concerns regarding immunogenicity and insertional mutagenesis [13] [9] [15]. Among non-viral methods, spherical nucleic acids (SNAs) have demonstrated entry into cells up to three times more effectively than standard lipid nanoparticles and with less toxicity [14]. Gold nanoparticles and other inorganic carriers also show enhanced cellular uptake due to their tunable surface chemistry and ability to be functionalized with cell-penetrating peptides [11] [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Limited Diffusion Through EPS-Rich Biofilms

Symptom: CRISPR cargo fails to penetrate biofilm mass, resulting in low or no gene editing in target bacterial cells.

Reason & Solution:

| Reason | Solution | Experimental Evidence / Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Barrier from EPS Matrix: The dense matrix of polysaccharides, proteins, and eDNA in biofilms acts as a molecular sieve, physically blocking the passage of CRISPR cargo [11]. | Use Nanoparticle Carriers: Engineer nanoparticles small enough to navigate the biofilm mesh. Functionalize their surface with positive charges or biofilm-degrading enzymes (e.g., DNase, dispersin B) to disrupt the matrix and improve penetration [11]. | Protocol: Liposomal Cas9 Formulation for Biofilm Penetration1. Formulate liposomes encapsulating Cas9-gRNA RNP complexes.2. Coat liposomes with a cationic polymer (e.g., chitosan) to facilitate interaction with the anionic EPS.3. Apply the formulation to a mature biofilm (e.g., P. aeruginosa) in vitro and incubate.4. Assess penetration via confocal microscopy using fluorescently tagged liposomes.5. Quantify efficacy by measuring biofilm biomass reduction; liposomal Cas9 has been shown to reduce biomass by over 90% [11]. |

| Lack of Targeting: Cargo does not actively navigate to bacterial cells within the biofilm. | Functionalize with Targeting Ligands: Conjugate nanoparticles with ligands, such as antibodies or peptides, that specifically bind to surface markers on the target bacterial species [11]. | Protocol: Assessing Diffusion with Fluorescent Reporters1. Prepare control (free cargo) and experimental (nanoparticle-loaded) samples, both tagged with a fluorescent dye.2. Apply samples to the surface of a mature biofilm grown in a flow cell or similar system.3. Over time, capture Z-stack images of the biofilm using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM).4. Analyze fluorescence intensity at different biofilm depths to create a penetration profile and compare the two groups. |

Problem 2: Nuclease Degradation of CRISPR Components

Symptom: Guide RNA or Cas9 mRNA is degraded before reaching the target cell, leading to a loss of editing function.

Reason & Solution:

| Reason | Solution | Experimental Evidence / Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Vulnerability of Nucleic Acids: Naked guide RNA and DNA are rapidly degraded by nucleases present in the extracellular environment or within cellular endosomes [9]. | Use Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes: Directly deliver pre-assembled complexes of Cas9 protein and gRNA. This avoids the need for transcription and translation, reducing the window of vulnerability [9]. | Protocol: Validating RNP Stability Against Nucleases1. Incubate purified RNP complexes (Cas9 + gRNA) with a serum-containing medium or a defined nuclease solution.2. At set time points, run samples on a gel to check for gRNA degradation.3. Compare with plasmid DNA or in vitro transcribed mRNA under the same conditions.4. Test functional stability by transferring the treated RNPs into cells and measuring cleavage activity with a Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit [12]. |

| Insufficient Cargo Protection: The delivery vehicle does not adequately shield its contents. | Select Protective Nanocarriers: Use nanoparticles known for high encapsulation efficiency and stability, such as gold nanoparticles or polymer-based NPs, which form a protective shell around the CRISPR machinery [11] [9]. | Protocol: Gold Nanoparticle RNP Delivery1. Synthesize or purchase gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) functionalized for RNP binding.2. Conjugate pre-assembled RNPs to the AuNPs via covalent or affinity binding.3. Treat target cells and measure gene-editing efficiency. Studies show AuNP carriers can enhance editing efficiency up to 3.5-fold compared to non-carrier systems [11]. |

Problem 3: Inefficient Cellular Uptake

Symptom: CRISPR cargo accumulates outside cells but does not enter, resulting in no editing.

Reason & Solution:

| Reason | Solution | Experimental Evidence / Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Internalization by Target Cells: Standard delivery vehicles like LNPs often get trapped in endosomal compartments and are degraded before releasing their cargo into the cytoplasm [14]. | Utilize Advanced Nanostructures: Employ Spherical Nucleic Acids (LNPs-SNAs). The dense, spherical DNA shell on these particles interacts with cell surface receptors, promoting rapid and efficient uptake and facilitating endosomal escape [14]. | Protocol: Testing Uptake with LNP-SNAs1. Synthesize LNP-SNAs with a core containing CRISPR RNP and a shell of dense, oriented DNA strands.2. Treat various cell types (e.g., primary cells, stem cells) with LNP-SNAs and standard LNPs, both carrying a fluorescent reporter.3. Analyze by flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy to quantify the percentage of positive cells and mean fluorescence intensity. LNP-SNAs have shown a 3x improvement in cell entry and a 3x boost in editing efficiency [14]. |

| Low Transfection Efficiency: The method used is not optimal for the specific cell type. | Optimize Transfection and Enrich Transfected Cells: For difficult cell lines, optimize the transfection protocol using high-performance reagents (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000). To enrich for successfully transfected cells, introduce antibiotic resistance genes with the CRISPR cargo and apply selection pressure, or use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) if a fluorescent reporter is co-delivered [12]. | Protocol: Enriching Edited Cells via Antibiotic Selection1. Co-transfect your CRISPR construct (e.g., plasmid expressing Cas9 and gRNA) with a separate plasmid carrying an antibiotic resistance gene (e.g., puromycin).2. 24-48 hours post-transfection, add the appropriate antibiotic to the culture medium.3. Maintain selection for 3-7 days, replacing the medium with fresh antibiotic as needed.4. After selection, assay the surviving cell population for editing efficiency, which will be significantly enriched [12]. |

Table 1: Efficacy of Selected Nanoparticle Systems for Overcoming CRISPR Delivery Hurdles

| Delivery System | Target Challenge | Key Metric | Performance Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liposomal Cas9 Formulation | Limited Diffusion (Biofilm) | Biofilm Biomass Reduction | >90% reduction in P. aeruginosa biofilm in vitro [11] | |

| CRISPR-Gold Nanoparticle Hybrids | Cellular Uptake & Degradation | Gene-Editing Efficiency | 3.5-fold increase compared to non-carrier systems [11] | |

| Lipid Nanoparticle SNAs (LNP-SNAs) | Cellular Uptake & Endosomal Escape | Cell Internalization & Editing | 3x more effective cell entry & 3x higher editing efficiency; >60% improvement in precise HDR repair [14] | |

| Nanoparticle & Antibiotic Co-delivery | Limited Diffusion & Efficacy | Synergistic Antibacterial Effect | Superior biofilm disruption and synergistic antibacterial effects [11] |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Addressing CRISPR Delivery Challenges

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Kits | Formulate and encapsulate CRISPR RNPs or nucleic acids for improved delivery and protection. | Shields cargo from nucleases; can be tailored for specific cell targeting [11] [14]. |

| GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit | Detect and validate successful CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage at the target genomic locus. | Confirms whether delivery was successful and the CRISPR system is functionally active in cells [12]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Serve as a non-viral carrier for conjugated CRISPR RNP complexes. | Enhances editing efficiency and stability; proven 3.5x increase in some studies [11]. |

| Spherical Nucleic Acids (LNPs-SNAs) | Advanced nanostructure for high-efficiency delivery of full CRISPR machinery. | Promotes superior cellular uptake and endosomal escape; boosts editing efficiency threefold [14]. |

| PureLink PCR Purification Kit | Purify DNA templates and PCR products for high-quality sequencing or downstream applications. | Ensures clean, concentrated DNA for accurate analysis and cloning steps [12]. |

Biofilm-associated infections represent a critical frontier in the challenge of CRISPR-Cas9 delivery. The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix of biofilms creates a formidable physical and chemical barrier that significantly reduces the efficacy of conventional delivery systems [5]. This dense matrix, composed of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA, limits the penetration of antimicrobial agents and genetic tools by altering bacterial metabolism and creating diffusion barriers [16] [5]. For researchers developing CRISPR-based antimicrobials, understanding and overcoming these delivery inefficiencies is paramount for successful gene editing in biofilm-forming pathogens.

The inherent resistance mechanisms of biofilms can render CRISPR therapies ineffective if delivery systems cannot penetrate the EPS matrix and reach their intracellular targets. This case study examines the specific delivery challenges within EPS-rich environments and provides practical troubleshooting guidance for researchers working to advance CRISPR-based anti-biofilm strategies.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Biofilm Delivery Challenges

Q1: Why does my CRISPR-Cas9 system show significantly reduced efficiency against biofilm-forming bacteria compared to planktonic cultures?

The reduced efficiency stems from multiple biofilm-specific barriers:

- EPS Matrix Blockade: The dense extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix physically impedes nanoparticle diffusion. Studies demonstrate that conventional lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) show 60-80% reduced penetration in mature Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms compared to free diffusion in liquid culture [5].

- Altered Bacterial Metabolism: Bacteria in biofilms often enter a metabolically dormant state, reducing cellular uptake mechanisms and rendering them less susceptible to genetic manipulation [5].

- Enzymatic Degradation: The biofilm microenvironment contains nucleases and proteases that can degrade CRISPR components before they reach target cells [9] [5].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Quantify biofilm maturity: Use crystal violet staining or confocal microscopy to characterize biofilm density before CRISPR delivery experiments.

- Pre-treat with matrix-disrupting enzymes: Consider combining CRISPR delivery with DNase I (targeting eDNA) or dispersin B (targeting polysaccharides) to enhance penetration [5].

- Switch to smaller Cas variants: Utilize compact Cas12f (~2.5x smaller than SpCas9) to overcome size exclusion limitations [17] [18].

Q2: Which delivery vector shows highest efficacy for CRISPR delivery through EPS matrices?

Recent comparative studies indicate nanoparticle-based systems outperform viral vectors for biofilm penetration due to tunable surface properties and protection against degradation [9] [5].

Table: Delivery System Efficacy in Biofilm Models

| Delivery System | Editing Efficiency in Biofilms | Key Advantages | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles | 3.5x higher than non-carrier systems [5] | Surface-functionalization capability, photothermal properties | Potential cytotoxicity at high concentrations |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | 90% biofilm biomass reduction with liposomal Cas9 [5] | High payload capacity, biocompatibility | Endosomal entrapment can reduce efficiency |

| Adeno-associated Viruses (AAV) | <15% in dense biofilms [9] | High infectivity in planktonic cells | Size exclusion by EPS matrix, immunogenicity concerns |

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | 40-60% target gene knockout [9] | Sustained release profile, tunable degradation | Variable loading efficiency |

Recommended Protocol: Gold Nanoparticle-Mediated RNP Delivery

- Synthesize or purchase 20-40nm gold nanoparticles functionalized with polyethylenimine (PEI).

- Complex with pre-assembled Cas12a RNP (4:1 nanoparticle:RNP ratio) for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Add 1mM EDTA to the biofilm culture to weaken matrix integrity prior to nanoparticle addition.

- Apply nanoparticle-RNP complexes at 50μg/mL final concentration.

- Utilize laser irradiation (670nm, 0.5W/cm², 5min) for photothermal release if using functionalized gold nanoparticles [5].

Q3: How can I validate successful CRISPR delivery and gene editing within biofilm structures?

Standard validation methods for planktonic cultures often fail in biofilms due to spatial heterogeneity and limited sampling efficiency.

Validation Workflow:

- Spatial analysis via FISH-CRISPR: Combine fluorescence in situ hybridization with Cas9-targeted sequencing to visualize editing events within different biofilm regions [5].

- Resistance gene monitoring: Track the loss of antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., bla, mecA) as evidence of successful editing using qPCR of biofilm homogenates.

- Confocal microscopy with reporter systems: Engineer target bacteria with GFP reporters under control of targeted promoters; successful editing eliminates fluorescence [5].

Q4: What strategies can enhance nanoparticle penetration through EPS matrices?

Surface functionalization is key to improving penetration:

- Matrix-binding peptides: Conjugate nanoparticles with EPS-binding peptides (e.g., γ9WGγ9 from Staphylococcus aureus) to facilitate matrix penetration [5].

- Enzyme conjugation: Covalently link matrix-degrading enzymes (e.g., alginate lyase for P. aeruginosa) to nanoparticle surfaces.

- Charge modulation: Use slightly cationic nanoparticles (+5 to +15mV zeta potential) to overcome anionic EPS components without excessive biofilm binding [9] [5].

Optimization Protocol:

- Characterize EPS composition of your specific biofilm model via FTIR or chemical analysis.

- Functionalize nanoparticles with targeted matrix-binding or degrading molecules.

- Test penetration using fluorescently labeled nanoparticles and confocal z-stack imaging.

- Measure editing efficiency at various biofilm depths via microdissection and PCR.

Q5: How do I differentiate between delivery failure and CRISPR machinery failure in biofilm experiments?

Use this diagnostic flowchart to isolate the failure point:

Diagnostic Experiments:

- Planktonic control: Test your CRISPR system on planktonic cells of the same bacterial strain.

- Penetration assay: Use fluorescently labeled nanoparticles or dextrans of similar size to your delivery system.

- Component stability: Recover delivery vehicles from biofilm exposure and analyze CRISPR component integrity via gel electrophoresis.

- Bacterial viability post-treatment: Ensure bacteria remain viable after nanoparticle treatment to distinguish between delivery failure and bactericidal effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Delivery in Biofilm Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism | Biofilm-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compact Cas Proteins | SaCas9, Cas12f (Cas14), Cas12j | Smaller size enables better diffusion through EPS matrix | Cas12f (~400aa) shows 3.2x improved penetration vs SpCas9 (~1368aa) [17] [18] |

| RNP Complexes | Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease, custom guide RNA | Pre-formed protein-RNA complexes for immediate activity | 60% faster editing kinetics vs plasmid delivery; reduced off-target effects in heterogeneous biofilm environments [17] |

| Penetration-Enhanced Nanoparticles | Au-PEI NPs, Chitosan-Zn NPs, Lipid-PEG NPs | Tunable surface chemistry for matrix penetration | Au-PEI NPs show 3.5x higher editing efficiency in P. aeruginosa biofilms vs standard lipoplexes [5] |

| Matrix Disruption Agents | DNase I, Alginate lyase, Dispersin B | Degrades specific EPS components to create penetration channels | DNase I pre-treatment increases nanoparticle penetration by 45% in S. epidermidis biofilms [5] |

| Electroporation Enhancers | IDT Alt-R Cas9 Electroporation Enhancer | Carrier molecules that improve RNP delivery during electroporation | Specifically designed for hard-to-transfect cells; not for in vivo use [17] |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors | Furanones, AHL analogs | Disrupts bacterial communication to reduce EPS production | Can increase CRISPR accessibility by 30% when combined with nanoparticle delivery [5] |

Advanced Experimental Protocol: CRISPR-Nanoparticle Hybrid System for Biofilm Editing

This integrated protocol combines optimized delivery with validation methods specifically for biofilm models.

Materials:

- Pre-assembled Cas12a RNP complex (Alt-R CRISPR-Cas12a system)

- 20nm gold nanoparticles functionalized with PEI and alginate lyase

- Mature 72-hour biofilm of target bacteria

- Confocal microscopy dishes with glass bottoms

- SYTO 9 and propidium iodide for viability staining

Procedure:

- Biofilm Preparation: Grow biofilms for 72 hours under conditions optimal for your bacterial species. Characterize density via crystal violet staining or confocal microscopy.

Nanoparticle-RNP Complex Formation:

Biofilm Treatment:

Penetration Validation:

Editing Efficiency Assessment:

Expected Results:

- 40-60% editing efficiency in upper biofilm layers (0-20μm depth)

- 15-30% editing efficiency in middle layers (20-40μm depth)

- <10% editing efficiency in deepest layers (>40μm depth)

- 3.5x higher efficiency versus non-vectored RNP delivery [5]

The dense, heterogeneous nature of biofilm matrices presents unique delivery challenges that require specialized approaches beyond standard CRISPR protocols. Successful gene editing in biofilms depends on integrating multiple strategies: selecting appropriately sized CRISPR machinery, utilizing penetration-enhanced nanoparticles, and combining delivery with matrix-disruption techniques. The troubleshooting framework and experimental protocols provided here offer researchers a systematic approach to overcome these barriers and advance CRISPR-based applications against biofilm-associated infections.

As the field progresses, continued innovation in nanoparticle design and biofilm biology will further enhance our ability to precisely edit bacterial genomes within these complex communities, opening new avenues for combating persistent infections and antibiotic resistance.

Navigating the Maze: Delivery Platforms for EPS-Penetrating CRISPR Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary challenges of using rAAV for CRISPR delivery in EPS-rich environments like bacterial biofilms?

EPS-rich matrices, such as those found in bacterial biofilms, present significant barriers to rAAV transduction. The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) creates a physical barrier that can limit the penetration and diffusion of viral vectors, reducing their ability to reach target cells. Furthermore, the biofilm environment can neutralize vectors and reduce transduction efficiency. Combining rAAV with nanoparticle (NP) technology is an emerging strategy to overcome this, as NPs can enhance cellular uptake and protect the genetic cargo. One study noted that liposomal Cas9 formulations reduced P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro, and CRISPR–gold nanoparticle hybrids demonstrated a 3.5-fold increase in gene-editing efficiency [5].

Q2: Which rAAV serotypes are most effective for transducing different cell types in the pulmonary system, a common site of biofilm-related infections?

The tropism of AAV serotypes varies significantly across different cell types in the lung. The table below summarizes the transduction efficiency of various serotypes in specific pulmonary epithelial cells, based on a 2024 study in mice [19].

| Target Cell Type in Lung | Highly Efficient AAV Serotypes |

|---|---|

| Airway Epithelium | AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.S |

| Club Cells | AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2 |

| Ciliated Cells | AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV-PHP.B |

| Alveolar Type I (AT1) Cells | AAV8, AAVrh10 |

| Alveolar Type II (AT2) Cells | AAV1, AAV5, AAV6, AAV6.2, AAV9, AAVie |

| Endothelial Cells | AAV1, AAV5, AAVie, AAV-PHP.B, AAV-PHP.eB, AAV-PHP.S |

Q3: How can I engineer the AAV capsid to improve its tropism for my specific cell type of interest?

Capsid engineering is a powerful method to enhance AAV tropism and evade immune responses. The main strategies are summarized in the diagram below, which outlines the workflow from goal identification to functional validation [20] [21].

Q4: What is a standard protocol for producing and purifying high-titer rAAV for in vivo experiments?

Below is a detailed protocol for helper-free rAAV production and purification, adapted from common laboratory practices [22] [23].

Step 1: Transfection of HEK293 Cells

- Cells: Use highly transfectable HEK 293T cells (e.g., AAVpro 293T Cell Line or HEK 293T/17 from ATCC).

- Plasmids: Co-transfect the cells with three plasmids using PEI or a similar transfection reagent:

- Rep/Cap Plasmid: Provides AAV replication and capsid proteins for the desired serotype.

- Helper Plasmid: Provides essential adenoviral genes (E1, E2a, E4, VA RNA) for AAV replication.

- rAAV Vector Plasmid: Contains your gene of interest flanked by AAV2 ITRs.

- Ratio: A common DNA mass ratio is 1:4:2 (Vector:Rep/Cap:Helper) [22].

Step 2: Harvest and Lysis

- 48-72 hours post-transfection, harvest both the cells and the culture media.

- Pellet the cells and resuspend them in a lysis buffer (e.g., AAVpro Extraction Solution). Perform freeze-thaw cycles or use a detergent-based lysis to release the viral particles.

Step 3: Purification

- Purify the viral vectors from the crude lysate. Avoid prolonged ultracentrifugation by using a commercial purification kit (e.g., AAVpro Purification Kit for all serotypes).

- Process: The kit typically uses affinity chromatography and can complete purification in approximately 4 hours.

- Yield: Standard yields range from 1x10^10 to 2.5x10^12 vector genomes (vg) per preparation, depending on scale [23].

Step 4: Titration and Quality Control

- Titration: Determine the viral titer (vg/mL) using quantitative PCR (qPCR) with primers targeting the AAV2 ITR region, which is common across serotypes when using AAV2 ITR-based vectors.

- Purity: Confirm purity by SDS-PAGE, which should show three major bands corresponding to the capsid proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3 [23].

Q5: What is a typical dosage for administering rAAV to mice intravenously?

Dosage depends on the target tissue, desired transduction level, and the specific AAV capsid. For systemic delivery in adult mice (6-8 weeks old), common doses are:

- AAV-PHP.eB: 1 × 10^11 to 5 × 10^11 vg per mouse [22].

- AAV-PHP.S: 3 × 10^11 to 1 × 10^12 vg per mouse [22]. For general animal experiments, a dose between 10^11 and 10^12 vg per animal is typical, but the optimal dose should be determined empirically for your specific application [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| HEK 293T Cells | A standard cell line used for high-titer rAAV production due to high transfection efficiency and constitutive expression of SV40 large T antigen [23]. |

| Helper-Free System | A plasmid system that provides adenoviral helper functions without the need for a live helper virus, improving safety and simplifying production [23]. |

| AAVpro Purification Kit | Enables fast (~4 hours) purification of AAV particles from any serotype without requiring ultracentrifugation [23]. |

| AAV Serotypes (e.g., PHP.B, PHP.eB) | Engineered capsids with enhanced central nervous system (CNS) tropism in specific mouse strains, though their efficacy depends on the host expressing the Ly6a receptor [22]. |

| AAV2 ITR-specific qPCR Titration Kit | Allows for accurate quantification of viral genome titer for any AAV serotype, as long as the vector genome is flanked by AAV2 ITRs [23]. |

| Selective Organ Targeting (SORT) LNPs | Engineered lipid nanoparticles that can be used as an alternative or complementary delivery vehicle to target specific tissues like the lung, spleen, and liver [24]. |

Advanced Concepts: Receptor-Mediated Tropism

The cellular entry of different AAV serotypes is governed by their interaction with specific cell surface receptors. Understanding these relationships is key to selecting or engineering the right vector. The following diagram illustrates the primary and co-receptors for several well-characterized serotypes [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use non-viral nanocarriers for CRISPR delivery in EPS-rich research instead of viral vectors? Viral vectors, while efficient, present significant challenges for clinical translation, including immunogenicity, limited cargo capacity, and the risk of insertional mutagenesis [25] [26]. These issues are compounded in complex experimental environments. Non-viral nanocarriers offer a safer and more flexible alternative. They exhibit lower immunogenicity, can be produced at a larger scale, and their surface properties can be chemically modified to enhance penetration through physical barriers like Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) matrices [5] [27]. For instance, one study demonstrated that liposomal Cas9 formulations reduced P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro [5].

Q2: What are the key advantages of the Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) format for CRISPR delivery? Delivering the pre-assembled Cas9 protein and guide RNA as a Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex provides several critical advantages for both general use and specific applications in EPS-rich environments:

- Rapid Activity: The RNP is immediately active upon delivery, bypassing the need for transcription and translation. This leads to a shortened editing window, minimizing off-target effects and accelerating the experimental timeline [28] [26].

- Reduced Immunogenicity and Cytotoxicity: Unlike plasmid DNA, RNP delivery avoids the risk of genomic integration and triggers a lower immune response, which is crucial for sensitive in vivo applications [24] [29].

- Enhanced Precision: The transient nature of RNP activity is associated with higher editing precision and fewer off-target effects [28].

Q3: How can I improve the stability and editing efficiency of my CRISPR-nanocarrier formulations? Optimizing stability and efficiency involves strategic choices in both the CRISPR machinery and the nanocarrier composition:

- Use Thermostable Cas9 Variants: Employing engineered, thermostable Cas9 proteins, such as iGeoCas9, can significantly boost editing efficiency. These variants demonstrate superior stability and have shown >100-fold higher genome editing in cells and organs compared to their native forms, making them more resilient during the nanocarrier formulation process [29].

- Chemical Modification of Guides: Incorporating chemical modifications (e.g., 2’-O-methyl-3’-phosphonoacetate) into the guide RNA can protect it from nuclease degradation, enhancing its stability and overall editing efficiency [28].

- Surface Functionalization: Modifying the surface of nanocarriers with targeting ligands or tuning their charge can improve their interaction with and penetration into specific EPS-rich targets [5] [27].

Q4: What are the primary barriers that hinder efficient non-viral CRISPR delivery? Non-viral delivery must overcome multiple extracellular and intracellular barriers to be successful:

- Extracellular Barriers: These include nucleases and proteases in physiological fluids that can degrade the CRISPR cargo, as well as the physical obstruction of dense EPS or biofilm matrices that limit nanoparticle penetration [25] [5].

- Intracellular Barriers: Once internalized, nanocarriers are typically trapped in endosomes. To be functional, the CRISPR cargo must escape the endosome before degradation in the lysosome and then be transported into the cell nucleus [24] [28]. Gold nanoparticles, for example, leverage their surface charge to promote endosomal escape [30].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common experimental problems encountered when using non-viral nanocarriers for CRISPR delivery.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Editing Efficiency | 1. Inefficient cellular uptake2. Poor endosomal escape3. RNP/protein degradation4. Inefficient nuclear entry | 1. Confirm nanocarrier surface charge (zeta potential); use cationic lipids/polymers to promote cell binding [28] [27].2. Formulate LNPs with ionizable or pH-sensitive lipids (e.g., DOPE) to enhance endosomal disruption [28] [29].3. Use thermostable Cas9 variants (e.g., iGeoCas9) and chemically modified guide RNAs to improve cargo stability [29] [28]. |

| High Cytotoxicity | 1. Cytotoxic transfection reagents2. Persistent Cas9 expression3. Cationic nanocarrier toxicity | 1. Switch to RNP delivery for transient activity and reduced cell stress [26] [29].2. Optimize the nanoparticle-to-cell ratio; reduce the concentration of cationic lipids/polymers [27].3. Use biodegradable lipid materials, such as ester-based lipids, to improve biocompatibility [28] [26]. |

| Poor Penetration in EPS/ Biofilm Models | 1. Large nanocarrier size2. Non-specific binding to matrix3. Lack of targeting | 1. Optimize formulation to produce smaller nanoparticles (<100 nm) for better diffusion [5].2. Incorporate PEGylation (e.g., DMG-PEG2000) to create a stealth coating and reduce non-specific adhesion [28] [26].3. Functionalize nanocarrier surface with targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies) specific to biofilm components [5] [27]. |

| Low Nanocarrier Cargo Loading | 1. Incorrect N/P ratio (for nucleic acids)2. Unstable complex formation3. Cargo size too large | 1. For plasmid DNA/mRNA, systematically adjust the ratio of amine groups (N) in the carrier to phosphate groups (P) in the nucleic acid [27].2. For RNP loading, leverage charge interactions; gold nanoparticles can be engineered with specific surface chemistry to bind RNPs stably [30] [26]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for different non-viral nanocarriers as reported in recent literature, providing a benchmark for your own experimental systems.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Non-Viral Nanocarriers for CRISPR Delivery

| Nanocarrier Type | CRISPR Cargo Format | Target / Model System | Reported Efficiency | Key Findings / Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | iGeoCas9 RNP | Mouse Lung (SFTPC gene) | ~19% editing in vivo [29] | Uses biodegradable, cationic lipids for efficient RNP delivery to non-liver tissues. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Cas9 mRNA & sgRNA | Mouse Liver (PCSK9 gene) | ~60% editing in vivo [26] | Employs amino-ester-derived lipid-like nanomaterials (e.g., FTT lipids) [26]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Cpf1 RNP | Human Blood Stem Cells (CCR5 gene) | 10-20% editing in vitro [30] | Spherical gold nanoparticles facilitate endosomal escape via charge interaction; showed high viability. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Cas9 RNP | HEK293-GFP Reporter Cells | ~70% GFP knockout in vitro [26] | Formulated with bioreducible lipid-like materials for enhanced cytoplasmic release. |

| CRISPR-Gold (AuNP) | Cas9 RNP | Mouse Brain (mGluR5 gene) | 40-50% reduction in protein/mRNA [26] | Cationic arginine gold nanoparticles (ArgNPs) enable efficient RNP delivery in vivo. |

| Liposomal Formulations | Cas9 RNP | P. aeruginosa Biofilm (in vitro) | >90% reduction in biofilm biomass [5] | Liposomes enhance penetration of the biofilm EPS matrix and delivery of antimicrobial CRISPR cargo. |

Experimental Workflow & Protocol

The diagram below illustrates a generalized workflow for developing and testing a nanoparticle-based CRISPR delivery system for challenging EPS-rich environments.

Detailed Protocol: Formulating and Testing Gold Nanoparticles for RNP Delivery

This protocol is adapted from studies demonstrating successful RNP delivery using gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) to edit blood stem cells [30] [26].

Objective: To synthesize, characterize, and functionally validate gold nanoparticles as carriers for CRISPR RNP delivery.

Materials:

- Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄)

- Reducing agent (e.g., sodium citrate)

- Custom synthetic guide RNA (sgRNA) with optional chemical modifications

- Purified Cas9 protein (or alternative nuclease like Cpf1)

- Cell culture reagents and target cell line (e.g., HEK293, primary stem cells)

- Transfection medium (e.g., serum-free Opti-MEM)

- Gel electrophoresis apparatus for validation

Methodology:

- Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs):

- Prepare gold ions by suspending chloroauric acid in deionized water.

- Reduce the gold ions using a citrate reduction method to form spherical AuNPs of a defined size (e.g., ~15-30 nm). The size can be controlled by the citrate-to-gold ratio [30].

Formation of RNP Complex:

- Pre-complex the purified Cas9 protein with the sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:1.2 (Cas9:sgRNA) in a suitable buffer. Incubate at 37°C for 10-15 minutes to form the active RNP complex.

Loading RNP onto AuNPs:

- Mix the pre-formed RNP complex with the synthesized AuNPs.

- The loading relies on electrostatic interactions and surface chemistry. The surface charge of the AuNPs is engineered to be positive to attract the negatively charged phosphate backbone of the RNP. Researchers may make "small molecular modifications to prevent the different parts from repelling one another" [30].

- Incubate the mixture for 30-60 minutes at room temperature to allow stable complex formation.

Characterization of AuNP-RNP Complexes:

- Size and Zeta Potential: Use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index (PDI) of the complexes. Measure the zeta potential to confirm a surface charge that promotes cellular uptake.

- Loading Efficiency: Analyze the complexes using gel shift assays or quantify unbound RNP via spectrophotometry to determine loading efficiency [26].

Functional Validation in Cell Culture:

- Seed target cells in a 24-well or 48-well plate so they are 60-80% confluent at the time of transfection.

- Wash cells with PBS and replace medium with serum-free transfection medium.

- Add the formulated AuNP-RNP complexes to the cells. A typical RNP dose may range from 1-10 µg per well, which must be optimized.

- Incubate for 4-6 hours, then replace the transfection medium with complete growth medium.

- Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection and analyze editing efficiency using T7 Endonuclease I assay, TIDE analysis, or next-generation sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nanoparticle-Mediated CRISPR Delivery

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | Core component of LNPs; enables encapsulation and endosomal escape via protonation at acidic pH. | DLin-MC3-DMA, LP01, SM-102 [28] [26] [29] |

| Helper Lipids | Stabilizes the LNP structure and promotes fusion with endosomal membranes. | Cholesterol, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) [28] [26] |

| PEGylated Lipids | Provides a "stealth" coating to reduce non-specific binding, improve stability, and prevent aggregation. | DMG-PEG2000, C16-PEG2000-ceramide [28] [26] |

| Cationic Polymers | Condenses nucleic acid cargo (plasmid, mRNA) via electrostatic interactions for polyplex formation. | Polyethylenimine (PEI), Chitosan [24] [26] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Inorganic core for assembling RNP complexes; facilitates endosomal escape. | Citrate-capped AuNPs, Cationic arginine AuNPs (ArgNPs) [30] [26] |

| Thermostable Cas9 | Engineered nuclease with enhanced stability, improving RNP resilience during formulation and delivery. | iGeoCas9 (evolved variant) [29] |

| Chemically Modified gRNA | Enhances stability against nucleases and can improve editing efficiency and reduce off-target effects. | 2’-O-methyl-3’-phosphonoacetate (MS) modified crRNA [28] |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Electroporation for CRISPR Delivery

FAQ 1: My electroporation experiment is yielding low CRISPR editing efficiency. What are the key parameters I should optimize?

Low editing efficiency is a common challenge. To address this, you should systematically optimize several key electroporation parameters. The table below summarizes critical parameters and their optimization strategies.

Table 1: Key Electroporation Parameters for CRISPR Efficiency

| Parameter | Impact on Efficiency | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse Amplitude/Voltage | Determines the electric field strength for membrane permeabilization; too low is ineffective, too high causes cytotoxicity [31]. | Titrate voltage to find the balance between effective editing and cell viability [31]. |

| Pulse Duration & Number | Affects the extent and duration of membrane permeability [32]. | Use a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach to screen combinations of phase duration and pulse number [32]. |

| Cargo Form | Influences onset of activity, duration, and off-target effects [24]. | Use Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for immediate activity and reduced off-target effects compared to plasmid DNA [24]. |

| Cell Health & Type | Primary and sensitive cells may require gentler protocols [32]. | Use high-density microelectrode arrays (MEAs) for gentler, more targeted electroporation on adherent cells [32]. |

FAQ 2: I am working with bacterial biofilms, which have a protective EPS matrix. How can I improve electroporation efficacy in these EPS-rich environments?

The EPS matrix significantly hinders macromolecule penetration. A promising strategy is to combine electroporation with nanoparticle carriers.

- Synergistic Action: Nanoparticles, such as gold or lipid nanoparticles, can be loaded with CRISPR-Cas9 components (like RNPs) and act as carriers [5]. The electric pulses help these nanocarriers penetrate the protective biofilm matrix and facilitate uptake by bacterial cells [5].

- Enhanced Efficacy: One study demonstrated that liposomal Cas9 formulations reduced Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm biomass by over 90% in vitro [5]. Furthermore, CRISPR-gold nanoparticle hybrids showed a 3.5-fold increase in gene-editing efficiency compared to non-carrier systems [5].

FAQ 3: I observe high cell death after electroporation. How can I reduce cytotoxicity?

Cell toxicity is often a consequence of harsh electroporation conditions.

- Mitigate Electrical Stress: Optimize electrical parameters by starting with lower voltages or fewer pulses and titrating upwards [31]. Using a Cas9 protein with a nuclear localization signal can enhance targeting efficiency, potentially allowing for lower, less toxic doses [31].

- Gentle Technologies: Planar microelectrode arrays (MEAs) with subcellular-sized electrodes can achieve high efficiency with reduced toxicity by affecting only a limited patch of the cell membrane [32].

- Constant Power Delivery: Recent research indicates that applying constant power pulsed electric fields (cpPEFs), instead of constant voltage, can achieve more consistent and predictable electroporation outcomes, potentially reducing unwanted cell death caused by variations in sample conductivity [33].

FAQ 4: How can I ensure consistent electroporation results when my samples have variable conductivity (e.g., different growth media or tissue types)?

Sample conductivity is a key variable that affects the electric field distribution and, thus, the outcome.

- Adopt Constant Power Pulsed Electric Fields (cpPEFs): Traditional constant-voltage electroporation is highly sensitive to conductivity variations. A 2025 study demonstrated that the threshold for electroporation is a power-density-driven phenomenon [33]. By applying pulses at a constant power level, researchers achieved consistent reversible and irreversible electroporation areas despite significant variations in extracellular conductivity [33]. This method better predicted treatment efficacy in vivo compared to using voltage or current alone [33].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Optimizing mRNA Transfection via High-Definition Electroporation (HD-EP)

This protocol is adapted from a study achieving 98% transfection efficiency in primary fibroblasts using a CMOS HD-EP chip [32].

1. Chip Preparation:

- Utilize a CMOS HD-EP chip comprising clusters of thousands of individually addressable microelectrodes (e.g., 5 μm or 8 μm in diameter) [32].

- Seed cells directly onto the chip surface and allow them to adhere and grow to the desired confluency [32].

2. Design of Experiments (DoE) Screening:

- To efficiently find optimal conditions, vary multiple parameters simultaneously in a highly parallelized screening experiment on the chip. The tested parameters included [32]:

- Electrode size

- Pulse amplitude (V)

- Phase duration (ms)

- Interval between pulses (ms)

- Number of pulses

3. Electroporation and Analysis:

- Apply different pre-defined pulse train conditions to different electrode clusters on the same chip [32].

- Transfert with an mCherry-encoding mRNA and incubate cells post-electroporation [32].

- Quantify transfection efficiency by measuring mCherry fluorescence, for example, via fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry [32].

- Fit a multiple linear regression model to the efficiency data to estimate the effect of each parameter and extract optimal conditions [32].

Protocol: Combining Nanoparticles with Electroporation for Biofilm Editing

This methodology outlines the use of nanoparticle-CRISPR complexes for targeting biofilm-associated bacteria [5].

1. Prepare CRISPR-Nanoparticle Complexes:

- Complex Formation: Formulate CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) with guide RNA (gRNA) targeting specific bacterial resistance or virulence genes [5].

- Encapsulation/Conjugation: Encapsulate the RNPs within or conjugate them to nanoparticles. Studies have used:

2. Biofilm Treatment:

- Grow mature biofilms of the target bacterium (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) in vitro [5].

- Apply the CRISPR-nanoparticle complexes to the biofilm [5].

- Subject the biofilm to optimized electroporation pulses. The pulses enhance the penetration of the nanoparticles through the EPS matrix and promote cellular uptake [5].

3. Assessment of Biofilm Disruption:

- Biomass Quantification: Measure the reduction in biofilm biomass using crystal violet staining or confocal microscopy [5]. (e.g., >90% reduction with liposomal Cas9 [5]).

- Editing Efficiency: Assess the disruption of target genes using genotyping assays (e.g., T7 endonuclease I assay, sequencing) [31].

- Viability Assessment: Use cell viability assays to confirm the loss of bacterial survival due to successful gene editing [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Electroporation-based CRISPR Delivery

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR RNP Complex | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and guide RNA. The preferred cargo for its immediate activity and reduced off-target effects [24]. | Design gRNA for high specificity to minimize off-target editing [31]. |

| Electroporator with Parameter Control | Device capable of delivering square-wave pulse trains with adjustable voltage, duration, and pulse number. | For advanced applications, systems capable of constant power delivery (cpPEF) can improve consistency [33]. |

| Electroporation Cuvettes / MEA Chips | Cuvettes with fixed electrodes for cell suspensions; Microelectrode Arrays for adherent cells. | High-density MEAs enable spatially resolved, high-efficiency transfection of adherent cells with low toxicity [32]. |

| Nanoparticle Carriers (e.g., Gold, Liposomal) | Acts as a protective carrier for CRISPR components, enhancing stability and delivery, especially in complex environments like biofilms [5]. | Gold nanoparticles can boost editing efficiency by over 3-fold in biofilm models [5]. |

| Cell Viability Assay Kits | To quantify cytotoxicity post-electroporation (e.g., MTT, Calcein AM). | Essential for titrating parameters to balance high efficiency with acceptable cell survival [31]. |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

CRISPR Electroporation Optimization Workflow

Strategy for Biofilm CRISPR Delivery

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center provides targeted solutions for researchers encountering challenges while using Virus-Like Particle (VLP) and SORT molecule hybrid systems to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 through EPS-rich matrices, such as bacterial biofilms.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using VLPs for CRISPR delivery in EPS-rich environments?

VLPs offer a unique combination of high transduction efficiency, similar to viral vectors, and transient CRISPR component expression, which minimizes off-target effects and cell toxicity [34]. Their biosynthetic nature helps avoid the inflammation sometimes associated with synthetic nanoparticles, and their surface can be reprogrammed for specific cell tropism, enabling targeted delivery within complex microbial communities [35].

Q2: My VLP-SORT system shows low gene editing efficiency in the target biofilm population. What could be wrong?

Low editing efficiency can stem from several factors. First, the EPS matrix can create a significant physical barrier to diffusion. Second, the CRISPR-cargo packaging efficiency into your VLPs might be suboptimal. Third, the SORT molecule functionalization on the VLP surface may not be effectively overcoming the EPS barrier. Ensure you are using high-titer VLP preparations and confirm the successful conjugation and functionality of SORT molecules. The table below summarizes common issues and initial checks.

Table: Quick Diagnostics for Low Editing Efficiency

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Initial Diagnostic Check |

|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency | EPS barrier impedes delivery | Measure VLP penetration fluorescence assay |

| Low editing efficiency | Poor cargo packaging in VLPs | Quantify p24 & Cas9 via Western Blot [35] |

| Low editing efficiency | Inactive SORT molecules | Validate conjugation efficiency & activity |

| High cell toxicity | VLP or SORT component concentration too high | Perform a dose-response titration experiment |

Q3: How can I minimize off-target effects when using this hybrid delivery system?

The key advantage of VLPs is their ability to deliver pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP). RNP has a short intracellular lifespan, drastically reducing the time window for off-target cleavage [35]. Furthermore, using high-fidelity Cas9 variants and carefully designing specific gRNAs with minimal predicted off-target sites are critical steps [31].

Q4: Are there specific immune response concerns with repeated VLP administration?

Yes, immune responses can be a concern. Studies show that while VLP-based RNP delivery elicits a significantly lower anti-Cas9 antibody response compared to lentiviral vectors that express Cas9 long-term, there can still be a noticeable immune reaction against the viral capsid components (e.g., p24) [35]. The use of different serotypes or engineering the VLP surface may be necessary for repeated dosing.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent VLP Production Yields

- Potential Cause 1: Suboptimal transfection efficiency of packaging plasmids.

- Solution: Use high-quality plasmid DNA and a robust transfection reagent. Validate transfection efficiency with a GFP-reporting plasmid.

- Potential Cause 2: Instability of the packaged cargo (e.g., mRNA, RNP).

- Solution: Incorporate cargo-stabilizing elements into your design. For RNPs, ensure the MS2-MCP system is correctly implemented for efficient Cas9 protein packaging [35] [34].

Problem: Failure in Targeted Delivery to Cells within an EPS-rich Biofilm

- Potential Cause: The native VLP tropism is unsuited for the target bacterial species, and the EPS matrix is sequestering or blocking the particles.

- Solution: Re-pseudotype the VLPs with envelopes that favor your target cell type [35]. Functionally couple SORT molecules to the VLP surface that are known to interact with or degrade specific EPS components to enhance penetration [36].

Problem: High Cytotoxicity Observed Post-Treatment

- Potential Cause 1: The concentration of VLPs or SORT molecules is too high.

- Solution: Perform a careful titration of both components to find a balance between delivery efficiency and cell viability [31].

- Potential Cause 2: Cytotoxicity from long-term, high-level expression of Cas9 nuclease.

- Solution: Switch to a VLP system that delivers pre-assembled RNP instead of Cas9-encoding DNA or mRNA. RNP delivery leads to rapid editing and clearance of the nuclease, minimizing persistent expression and associated toxicity [35].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Production of CRISPR RNP-Loaded VLPs

This protocol is adapted from recent studies for generating VLPs that package the Cas9 RNP complex [35].

Key Reagents:

- Plasmid encoding Gag protein (e.g., from lentivirus)

- Plasmid encoding MS2 coat protein fused to Gag

- Plasmid for VSV-G envelope protein

- Plasmid expressing Cas9 protein

- Plasmid expressing gRNA with incorporated MS2 stem loops

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Seed HEK-293T cells in appropriate culture vessels to reach 70-80% confluency at the time of transfection.

- Plasmid Transfection: Co-transfect the cells with the following plasmid combination using a standard calcium phosphate or PEI-based method:

- Gag-Pol plasmid (with D64V integrase mutation for safety)

- VSV-G envelope plasmid

- MS2-fused Gag plasmid

- Cas9 expression plasmid

- gRNA-MS2 stem loop plasmid

- VLP Harvest: 48-72 hours post-transfection, collect the cell culture supernatant.

- VLP Purification: Concentrate the VLPs from the supernatant by ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion at 100,000 × g for 2 hours.

- Quality Control: Resuspend the VLP pellet in PBS or a suitable buffer. Quantify the yield using a p24 ELISA kit and verify the presence of packaged Cas9 protein via Western blotting.

Protocol 2: Functionalizing VLPs with SORT Molecules for Enhanced Biofilm Penetration

This protocol outlines a strategy to conjugate SORT molecules (e.g., EPS-degrading enzymes) to the VLP surface.

Key Reagents:

- Purified VLPs

- SORT molecule (e.g., a specific glycoside hydrolase)

- Biotinylation reagent (e.g., NHS-PEG4-Biotin)

- Streptavidin (if using a biotin-streptavidin bridge)

- Cross-linker (e.g., SMPH)

Methodology:

- VLP Surface Activation: Gently mix the purified VLPs with a mild biotinylation reagent to label surface proteins. Remove excess biotin using a desalting column.

- SORT Molecule Preparation: If necessary, engineer or modify the SORT molecule to include a functional group (e.g., an amine) reactive with your chosen cross-linker.

- Conjugation: Incubate the biotinylated VLPs with streptavidin, followed by incubation with the biotinylated SORT molecule. Alternatively, use a heterobifunctional cross-linker like SMPH to directly link amine groups on the VLP surface to the SORT molecule.

- Purification: Purify the conjugated VLPs from unbound SORT molecules via size-exclusion chromatography or a second round of ultracentrifugation.

- Validation: Confirm successful conjugation using techniques like ELISA (to detect the SORT molecule) and a functional assay to verify that the SORT molecule retains its EPS-modifying activity post-conjugation.

System Workflow and Signaling Pathways

VLP-SORT System Workflow for Biofilm Editing

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for VLP-SORT-CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the System | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Lentiviral Gag-Pol Plasmid | Provides structural and enzymatic backbone for VLP assembly. | Use an integrase-deficient version (D64V) for enhanced safety [35]. |

| MS2 Coat Protein & Stem Loops | Facilitates specific packaging of Cas9 RNP into VLPs via RNA-protein interaction [35]. | Ensure stem loops are inserted at positions that do not interfere with gRNA function. |

| VSV-G Envelope Plasmid | Provides broad tropism pseudotype for initial VLP entry. | Can be replaced with other envelopes for specific targeting. |

| SORT Molecules | Enhances penetration through the EPS matrix and can aid in specific targeting. | Selection is critical (e.g., EPS-degrading enzymes, targeting peptides) [36]. |

| Cas9 Protein & gRNA | The core gene-editing machinery delivered as a pre-assembled RNP. | Using high-fidelity Cas9 variants and highly specific gRNAs reduces off-target effects [31]. |

| Ultracentrifugation Equipment | Essential for purifying and concentrating VLP preparations from cell culture media. | Maintain cold temperatures to preserve VLP integrity. |

For researchers aiming to combat persistent biofilms, the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix presents a formidable delivery barrier for CRISPR-based antimicrobials. This protective microbial environment, rich in polysaccharides, proteins, and DNA, significantly impedes the transport of therapeutic cargoes, leading to inconsistent editing outcomes and experimental failure [6]. Selecting the optimal cargo format—plasmid DNA (pDNA), messenger RNA (mRNA), or ribonucleoprotein (RNP)—is therefore not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of success. This guide provides a structured, troubleshooting-focused overview of these three primary cargo systems to help you navigate the complexities of CRISPR delivery within EPS-rich contexts, enabling more precise and efficient genome editing in your biofilm research.

Cargo Format Comparison: Mechanisms and Workflows

The journey of each cargo type from cellular entry to functional gene editing follows a distinct pathway, which directly impacts its performance in dense EPS matrices. The following diagram illustrates the key mechanisms and intracellular workflows for the three main CRISPR cargo formats.

Comparative Performance Data and Selection Table

Understanding the quantitative and qualitative performance of each cargo format is essential for experimental design. The table below summarizes key characteristics, supported by data from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of CRISPR Cargo Formats

| Parameter | Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | mRNA | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Onset of Activity | Slow (24-48h); requires transcription and translation [37] | Moderate (4-8h); requires only translation [38] [37] | Fastest (<2-4h); immediately active [24] [37] |

| Editing Efficiency | Variable; can be high but risk of off-targets [38] | High; lower off-targets than pDNA [38] [37] | Highest reported; superior specificity and efficiency [37] |

| Duration of Activity | Prolonged (days-weeks); risk of immune response and off-target effects [38] | Short (1-3 days); transient expression reduces off-target risk [38] | Shortest (~24h); most transient, minimizing off-target effects [24] |

| Stability in EPS/Delivery | High inherent stability; but large size hinders diffusion [6] | Low inherent stability; requires protection (e.g., LNPs) [39] [40] | Moderate stability; pre-assembled complex is more compact [37] |

| Immunogenicity Risk | High; can trigger innate immune sensors [38] | Moderate; immunogenicity can be engineered [39] [38] | Lowest; avoids nucleic acid-based immune activation [37] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity of construction and low cost [37] | No risk of genomic integration; faster than pDNA [39] [38] | Highest precision, immediate activity, and low off-targets [24] [37] |