Persister Cell Resuscitation: Mechanisms, Methods, and Therapeutic Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of bacterial persister cell resuscitation, a critical process underlying chronic and relapsing infections.

Persister Cell Resuscitation: Mechanisms, Methods, and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of bacterial persister cell resuscitation, a critical process underlying chronic and relapsing infections. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge on the triggers and molecular mechanisms that awaken dormant persisters. The content delves into cutting-edge single-cell and omics methodologies for studying resuscitation, addresses common challenges in experimental workflows, and offers a comparative evaluation of current models and validation techniques. By integrating these four core intents, this review aims to equip the scientific community with the insights needed to develop novel anti-persister strategies and overcome the clinical challenge of treatment-recalcitrant infections.

The Awakening Switch: Core Principles and Molecular Triggers of Persister Resuscitation

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How can I definitively confirm that the cells I am studying are in the VBNC state and not simply dead?

Answer: Confirming the VBNC state requires a multi-parameter approach, as no single assay is sufficient. You must demonstrate three key criteria simultaneously:

- Loss of Culturability: The cells must not form colonies on routine laboratory media that normally support their growth. This is confirmed when the colony-forming unit (CFU) count drops to zero.

- Maintenance of Viability: The cells must show signs of life through measures of metabolic activity or membrane integrity.

- Capacity for Resuscitation: The cells must be able to return to a culturable state when provided with specific, non-standard conditions (e.g., incubation in a resuscitation medium, passage through a host model) [1].

Troubleshooting Tip: A common error is misinterpreting a low CFU count for the VBNC state. Always combine plate counts with a direct viability method, such as live/dead staining. If all cells stain as "dead" (membrane-compromised), they are likely not VBNC. True VBNC cells will have intact membranes and often exhibit low-level metabolic activity [2] [3].

FAQ 2: My persister cell assays show high variability. What could be the cause?

Answer: Persister cell levels are highly sensitive to growth phase and environmental conditions.

- Growth Phase: The physiological state of the culture (exponential vs. stationary phase) dramatically influences persister frequency. Standardize the optical density and growth conditions precisely for all experiments.

- Antibiotic Killing Kinetics: Ensure you are performing a time-kill curve assay. A hallmark of persistence is a biphasic killing pattern, where the population is rapidly killed initially, followed by a plateau where the killing rate drastically decreases. This plateau represents the persister subpopulation [4] [5].

- Antibiotic Concentration and Type: Use a bactericidal antibiotic at a concentration significantly above the MIC (e.g., 5-100x MIC). Be aware that different antibiotics (e.g., ceftazidime vs. ciprofloxacin) can select for different persister subpopulations based on their mechanism of action [4].

FAQ 3: What is the most reliable method to distinguish between a persister cell and a VBNC cell in my sample?

Answer: The definitive test is the resuscitation assay following antibiotic removal.

- For Persisters: Wash the antibiotic away and resuspend the cells in fresh nutrient broth. Persister cells will typically resume growth and form colonies on solid media within hours to a day.

- For VBNC Cells: After washing, you will not see growth on standard media immediately. Instead, you must apply a specific resuscitation stimulus (e.g., incubation in a nutrient-poor medium, temperature shift, or addition of specific nutrients) and wait for a longer period (e.g., 24 hours) before culturable cells reappear [2] [1].

The following table summarizes the core differences to guide your experimental design.

| Feature | Persister Cells | VBNC Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Culturability | Retained on standard media [1] | Lost on standard media (CFU=0) [1] |

| Induction | Stochastic or by specific stresses (e.g., antibiotics) [6] [4] | Moderate, long-term stresses (e.g., starvation, temperature) [1] |

| Resuscitation | Rapid upon stress removal [1] | Requires specific resuscitation conditions [1] |

| Key Diagnostic | Biphasic killing in time-kill curves [4] | Resuscitation from a non-culturable state [2] |

Table 1: Experimental Evidence of Antibiotic-Induced Persister and VBNC States

This table summarizes quantitative data from key studies demonstrating how different antibiotics induce dormancy in bacterial populations.

| Bacterial Species | Stress Condition | Cell Survival Fraction (Log CFU/mL) | Phenotype Observed | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAO1) | Ceftazidime (5x MIC, 24h) | ~9.0 | High persister cell count | [4] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAO1) | Ciprofloxacin (5x MIC, 24h) | ~6.0 | Lower persister cell count | [4] |

| Vibrio vulnificus & E. coli | Ampicillin → Resuscitation | Increased count after 24h resuscitation | Presence of VBNC cells in persister isolation experiments | [2] |

| E. coli | Ofloxacin (60x MIC, 5-7h) | Surviving subpopulation | Drug-induced persisters from metabolically active cells | [7] |

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Differentiating Bacterial States

This table compares the primary techniques used to assess the viability and physiological state of bacterial cells.

| Method | What It Measures | Application to Persisters/VBNC | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate Count (Culture) | Culturability | Gold standard for detecting persisters; confirms non-culturability of VBNC cells [3] | Simple, inexpensive | Cannot detect VBNC cells [3] |

| Live/Dead Staining (e.g., BacLight) | Membrane Integrity | Identifies viable (membrane-intact) cells within a non-culturable population [2] [3] | Distinguishes live from dead cells | Does not confirm resuscitability |

| Redox Sensor Green (RSG) | Metabolic/Redox Activity | Detects low-level metabolic activity in dormant cells [4] | Probes metabolic state, not just membranes | Signal may be low or heterogeneous |

| Microfluidics & Single-Cell Imaging | Single-cell growth and division | Tracks history and fate of individual persister cells [7] | Unprecedented resolution of cell heterogeneity | Technically complex and specialized |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation and Quantification of Persister Cells

Principle: Persisters are isolated by exposing a bacterial population to a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic, which kills the majority of the population. The surviving, antibiotic-tolerant cells are persisters [4] [5].

Method:

- Culture Preparation: Grow the bacterial strain of interest to the mid-exponential growth phase (e.g., OD610 ~0.2-0.3) in a suitable broth.

- Antibiotic Exposure: Treat the culture with a bactericidal antibiotic at a high multiple of the MIC (e.g., 5-100x MIC). Incubate for a defined period (typically 4-6 hours) under standard growth conditions with aeration.

- Wash and Removal: After incubation, wash the cells at least twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or saline solution to remove the antibiotic thoroughly.

- Viability Assessment: Resuspend the cell pellet in fresh medium. Perform serial dilutions and plate on non-selective agar plates to determine the number of surviving culturable cells (CFU/mL). This quantifies the persister population [2] [4].

Principle: VBNC cells are induced by prolonged exposure to a sub-lethal environmental stress. Their viability is confirmed by metabolic assays, and resuscitation is triggered by removing the stress and providing specific stimulating conditions [2] [1].

Method: A. Induction:

- Stress Application: Take a log-phase culture, wash to remove nutrients, and resuspend in a minimal, non-growth-supporting medium (e.g., 1/2 artificial seawater for vibrios, 0.85% NaCl for E. coli).

- Incubation: Incubate the culture under inducing conditions (e.g., 4°C for several days or weeks). Monitor culturability daily by plating.

- Confirmation: The VBNC state is achieved when the CFU count drops below the detection limit (<10 CFU/mL) while viability is maintained, as confirmed by live/dead staining [2].

B. Resuscitation:

- Stimulus: Once the VBNC state is confirmed, transfer the cells to a resuscitation medium. This could be a nutrient-rich broth diluted with the induction medium or a specific medium supplemented with host factors (e.g., serum).

- Incubation: Incubate under permissive conditions (e.g., a higher temperature like 20-37°C) for up to 24-48 hours.

- Confirmation: After resuscitation, plate the cells on standard agar to confirm the return of culturability. A significant increase in CFU count compared to the non-resuscitated control confirms successful resuscitation [2].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

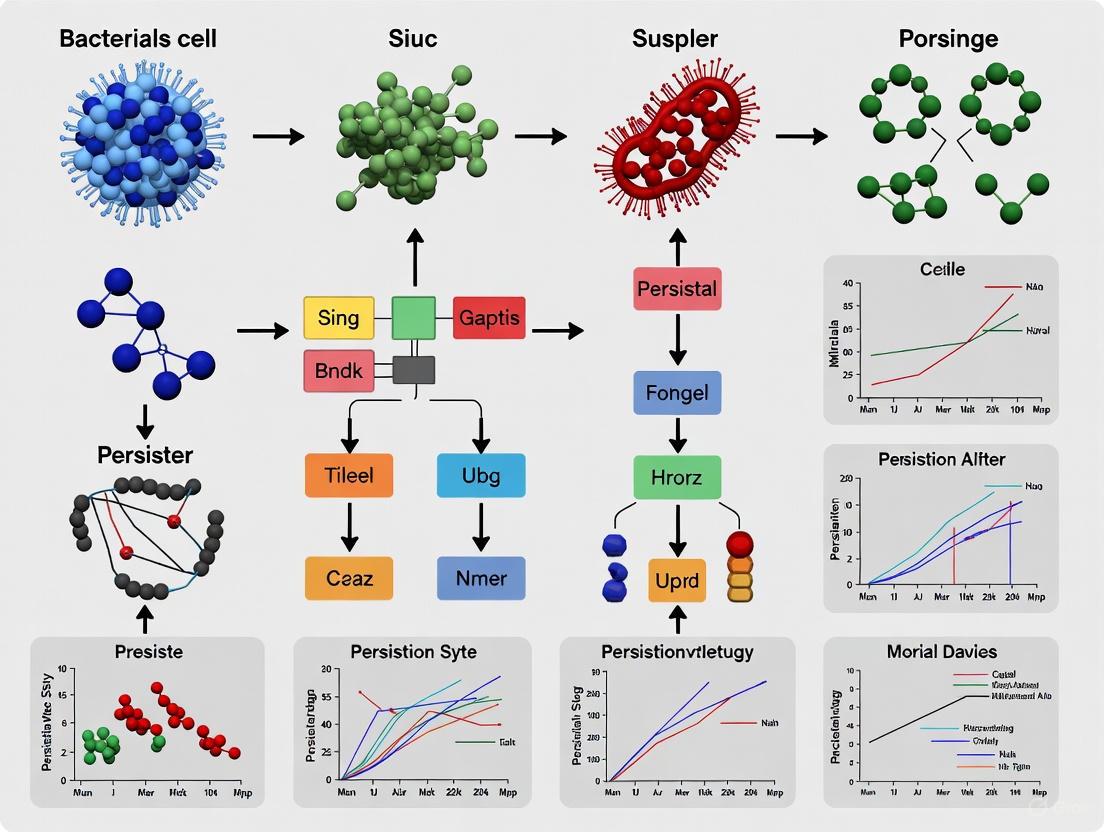

The formation of persister and VBNC cells is regulated by interconnected molecular pathways that respond to environmental stress. The diagram below illustrates the key mechanisms.

Diagram 1: Molecular Pathways Leading to Bacterial Dormancy. This diagram illustrates how environmental stress triggers core cellular responses—the Stringent Response, Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) System activation, and the SOS Response—that converge to induce a dormant state. The depth of this dormancy may influence whether a cell enters a readily revivable Persister state or requires specific signals to resuscitate from the VBNC state [6] [5] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Dormant Bacteria

This table lists key reagents and their applications in experiments focused on persister and VBNC cells.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| BacLight Live/Dead Viability Kit | Differentiates cells with intact (live) vs. compromised (dead) membranes using SYTO 9 and propidium iodide stains [2] [3]. | Confirming viability of non-culturable populations. |

| Redox Sensor Green (RSG) | Fluorescent dye used to detect metabolic and redox activity in cells, helping identify dormant but metabolically active persisters [4]. | Flow cytometry or microscopy to probe metabolic state. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | DNA-binding dye that penetrates only membrane-compromised cells; used with qPCR to selectively amplify DNA from viable cells (PMA-qPCR) [1]. | Quantifying viable pathogens in a sample without culture. |

| Ruthenium-based Oxygen Sensor (RTDP) | Oxygen-quenching fluorophore used in metabolic monitoring to detect oxygen consumption by viable bacteria in microfluidic devices [8]. | Real-time monitoring of bacterial growth and drug efficacy. |

| Toxin-Antitoxin Mutant Strains | Genetically modified strains (e.g., ΔhipA, Δ10TA) used to elucidate the functional role of specific TA modules in persistence [6] [4]. | Mechanistic studies on persister formation. |

| Microfluidic Devices | Platforms for single-cell analysis and long-term imaging, allowing tracking of individual cell fates before, during, and after antibiotic treatment [7]. | Studying heterogeneity and resuscitation of persisters. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my persister cells fail to resuscitate after antibiotic removal and transfer to fresh media? The most common cause is the failure to completely remove the antibiotic or other stressors during washing steps. Even trace amounts can prevent resuscitation. Ensure thorough washing, for example, via membrane filtration and resuspension in fresh, pre-warmed medium at least three times [9]. Furthermore, the history of the pre-culture significantly impacts resuscitation potential; cells from long-term stationary phase cultures may have entered a deeper dormant state or a Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) state, which has different resuscitation requirements [9].

Q2: My persister cell counts are highly variable between replicate experiments. How can I improve consistency? Persister formation is inherently heterogeneous, but consistency can be improved by strictly standardizing pre-culture conditions. The length of the stationary phase, precise optical density at the time of antibiotic treatment, and the specific growth medium all dramatically influence persister levels [9] [10]. For example, extended stationary phase incubation increases the proportion of VBNC cells, which do not resuscitate on standard media, leading to variable colony-forming unit (CFU) counts [9].

Q3: Are persister cells truly dormant, or can they be metabolically active before resuscitating? The classical view is that persisters are dormant. However, recent single-cell studies reveal a more complex picture. When sampled from exponential phase, a significant fraction of cells that survive antibiotic treatment were actually growing before drug exposure [10]. The metabolic state of persisters is a continuum, ranging from deep dormancy to slow metabolism, and this state can change with environmental conditions [11].

Q4: What is the difference between a persister cell and a VBNC cell, and how can I distinguish them in my assays? Both are non-growing, antibiotic-tolerant phenotypes. The key distinguishing feature is that persisters can resuscitate in standard culture media after antibiotic removal, whereas VBNC cells cannot under the same conditions [9]. Persistence is often considered a transitional state that can lead to the VBNC state. In your assays, use methods that can differentiate them, such as flow cytometry with a fluorescent protein dilution method to monitor cell division, or parallel plating on standard media versus media supplemented with resuscitation factors like catalase [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No colony growth on plates after washing and plating. | Incomplete antibiotic removal. | Increase number of washing steps; use membrane filtration for more effective antibiotic removal; validate wash efficacy with a bioassay or HPLC. |

| Cells have entered a VBNC state. | Supplement resuscitation media with antioxidants (e.g., catalase) or use spent media from growing cultures [9]. | |

| Insufficient nutrient availability in the resuscitation media. | Use rich, fresh media (e.g., LB); ensure proper aeration for aerobic organisms. | |

| Colonies appear only after extended, unpredictable delays. | Stochastic resuscitation model assumed, but dynamics may be different. | Note that recent evidence suggests resuscitation can be exponential and accelerated over time, not purely stochastic. Ensure adequate incubation time and monitor plates for up to a week [12]. |

Issue: Inconsistent Persister Levels in Pre-Cultures

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in persister counts between biological replicates. | Inconsistent pre-culture growth history. | Standardize inoculum size, growth time, and shaking speed. Use cultures grown to the same optical density (OD) from a fresh, overnight pre-culture. |

| Biofilm formation in culture flasks. | Use baffled flasks to improve aeration and minimize biofilm; sub-culture from the well-mixed suspension. | |

| A sudden drop in persister frequency. | Contamination. | Check for contamination by streaking on selective media and checking colony morphology. |

| Genetic drift in strain. | Re-streak from a frozen, master stock culture stored at -80°C. |

Table 1: Key Resuscitation Parameters from Single-Cell Studies

| Parameter | Value / Observation | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resuscitation Initiation | Within 1 hour post-antibiotic removal. | E. coli persisters after ampicillin treatment in fresh LB broth. | [9] |

| Doubling Time Post-Resuscitation | ~23-24 minutes. | First divisions of resuscitating E. coli persisters. This matches the doubling time of normal, untreated cells. | [9] |

| Resuscitation Dynamics Model | Exponential, not stochastic. The resuscitation rate accelerates over time. | E. coli and Salmonella enterica persisters after ampicillin treatment. | [12] |

| Impact of Treatment Duration | Longer antibiotic exposure increases cellular damage in persister progeny. | Treatment with β-lactams and quinolones leads to damaged resuscitated cells. | [12] |

| Key Controlling Parameter | Antibiotic concentration during treatment; efflux activity during resuscitation. | Efflux was identified as a critical factor for successful resuscitation after ampicillin treatment. | [12] |

Table 2: Impact of Pre-Culture Conditions on Persister States and Resuscitation

| Pre-Culture Condition | Effect on Persister Population | Implication for Resuscitation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term Stationary Phase | Higher proportion of "shallow" persisters with a greater likelihood of resuscitation. | More reliable and synchronous resuscitation in fresh media. | |

| Long-term Stationary Phase | Increased sub-population of VBNC cells and "deep" persisters. | Lower and more variable CFU counts after antibiotic treatment; may require specific resuscitation signals. | [11] [9] |

| Exponential Phase | Persisters can originate from both growing and non-growing sub-populations. | Resuscitation dynamics are highly heterogeneous, with some cells showing L-form-like growth or filamentation. | [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Adapted from BMC Microbiology [9]

Objective: To monitor persister resuscitation at the single-cell level and simultaneously quantify persister, VBNC, and dead cell subpopulations.

Key Reagents:

- Strain: E. coli with a chromosomally integrated, IPTG-inducible fluorescent protein (e.g., mCherry).

- Antibiotics: Ampicillin (or other β-lactam).

- Media: LB broth and LB agar plates.

- Equipment: Flow cytometer with cell-sorting capability, microcentrifuge, membrane filtration unit.

Methodology:

- Pre-culture and Fluorescence Induction: Grow the reporter strain overnight in LB with IPTG to induce strong fluorescent protein expression.

- Antibiotic Treatment: Dilute the pre-culture in fresh media (with IPTG) and grow to mid-exponential phase. Treat with a lethal dose of ampicillin (e.g., 200 µg/mL) for 3 hours to lyse all antibiotic-sensitive cells.

- Washing and Resuspension: Pellet the cells, wash thoroughly 3x with fresh LB (no IPTG, no antibiotic) to remove all traces of IPTG and the drug. Resuspend in fresh, pre-warmed LB.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze the cells immediately using a flow cytometer. Monitor forward scatter (FSC) and fluorescence over time.

- Resuscitating Persisters: Cells that show a decrease in fluorescence over time due to dilution of the pre-formed fluorescent protein as they divide.

- VBNC Cells: Cells that retain high, constant fluorescence because they are not dividing.

- Validation: Plate samples on LB agar at various time points to correlate fluorescence dilution with CFU counts.

Adapted from MSB [12]

Objective: To track the resuscitation dynamics and cell fates of individual persister cells.

Key Reagents:

- Strain: E. coli constitutively expressing a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP).

- Antibiotics: Ampicillin, Ciprofloxacin.

- Media: LB broth.

- Equipment: Time-lapse fluorescence microscope, agarose pads, microfluidic device (e.g., membrane-covered microchamber array).

Methodology:

- Persister Generation: Grow culture to stationary phase. Add to fresh media and treat with a high dose of ampicillin for 3+ hours until >99% of cells are killed.

- Cell Immobilization: Wash cells thoroughly to remove antibiotics. Concentrate and immobilize them on an agarose pad or load into a microfluidic device.

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Place the sample on a temperature-controlled stage and acquire images every 30 minutes for 12-24 hours.

- Data Analysis:

- Resuscitation Time (tʀ): Record the time of the first cell division for each persister.

- Doubling Time (δ): Calculate the doubling time of the persister progeny.

- Cell Fate Tracking: Observe for morphological changes (e.g., filamentation, L-form-like growth) and the phenomenon of "persister partitioning," where a damaged mother cell divides to produce one healthy and one defective daughter cell [12].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Persister Resuscitation Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Reporter Strains | Enabling single-cell tracking and monitoring of cell division via protein dilution. | E. coli with IPTG-inducible mCherry [9]; E. coli constitutively expressing GFP [12]. |

| Microfluidic Devices | For long-term, single-cell time-lapse microscopy under controlled conditions. | Membrane-covered microchamber array (MCMA) [10]; other commercial or custom-made cell-trapping devices. |

| β-Lactam Antibiotics | For persister generation and enrichment, as they lyse growing but not dormant cells. | Ampicillin (common, requires thorough washing) [9] [12]. Piperacillin (less stable, may require less washing). |

| Metabolic Inhibitors | To manipulate cellular energy levels and study the role of metabolism in persistence. | Arsenate (uncouples oxidative phosphorylation) [9]. Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) (protonophore). |

| Efflux Pump Inhibitors | To investigate the role of efflux in the resuscitation process. | Phe-Arg β-naphthylamide (PAβN); Carbonyl cyanide-m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) [12]. |

| Antioxidants / Catalase | As supplements to resuscitation media to aid recovery of cells under oxidative stress, potentially reviving VBNC cells. | Used in media for VBNC resuscitation studies [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How can I confirm that my bacterial population has entered a persistent state?

A successful persistence model should show a clear subpopulation that survives a high dose of a conventional antibiotic (e.g., bactericidal concentration 10-100x MIC) while remaining genetically identical to the parent strain. Key indicators include:

- Growth Arrest: A significant reduction in growth rate, observable via optical density or colony-forming unit (CFU) counts.

- Metabolic Downshift: Measurable reduction in ATP levels, membrane potential, or anabolic activity [13] [14].

- Tolerance, Not Resistance: Upon re-culturing in fresh media, the surviving cells should regain sensitivity to the same antibiotic [11].

FAQ 2: What are the primary metabolic characteristics of persister cells I should measure?

Your experimental focus should be on central carbon and energy metabolism. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from metabolic studies on E. coli persisters.

Table 1: Key Metabolic Features of Bacterial Persister Cells

| Metabolic Parameter | Observation in Persister Cells | Experimental Method | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Metabolic Rate | Substantially reduced compared to normal cells. | Stable Isotope Labeling (13C-Glucose, 13C-Acetate) with LC-MS/GC-MS | [13] [14] |

| Central Carbon Pathway Flux | Delayed labeling dynamics in glycolysis, PPP, and TCA cycle. | 13C-Glucose tracing | [13] [14] |

| Protein Synthesis Rate | Generalized, uniform slowdown. | Proteinogenic amino acid profiling via 13C labeling | [13] [14] |

| Energy Charge | Lower ATP levels and diminished proton motive force. | ATP assays, membrane potential-sensitive dyes | [15] [16] |

FAQ 3: My resuscitating agent isn't sensitizing persisters to antibiotics. What could be wrong?

This is a common hurdle. Consider the following:

- Verify Metabolic Activation: Ensure your agent truly increases metabolic activity. Use a bioluminescent reporter (e.g., JE2-lux strain) or measure ATP levels to confirm a shift from dormancy before adding antibiotics [15].

- Check Antibiotic Penetration: For intracellular persister models, confirm your antibiotic can penetrate the host cell membrane. Use rifampicin as a positive control, as it penetrates mammalian cells, unlike vancomycin [15].

- Timing and Dosage: The adjuvant may need to be administered before or concurrently with the antibiotic. Perform a time-kill curve assay to optimize the sequence and concentration [15].

FAQ 4: Why are my isolated ribosomes from nutrient-starved cells not binding tRNA/mRNA?

This is an expected characteristic of hibernating ribosomes. Under prolonged glucose depletion, ribosomes enter a protected, inactive state.

- Confirmed Phenomenon: Cryo-EM structures reveal that ribosomes from glucose-depleted yeast are intact but devoid of tRNA and mRNA [17].

- Structural Change: A conformational change in the ribosomal RNA helix H69 can occur, which physically blocks the tRNA binding site in the peptidyl transferase center and disrupts inter-subunit bridge B2a, preventing translation initiation [17].

- Experimental Validation: Perform polysome profiling. Hibernating ribosomes will appear as an accumulation of 80S monosomes and a loss of polysome fractions [17].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Inducing and Isating Persister Cells via Chemical Treatment

This protocol is adapted for generating E. coli persisters using the protonophore CCCP [14].

- Principle: CCCP dissipates the proton motive force, depleting ATP and inducing a dormant, persister-like state reversibly.

- Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: E. coli BW25113

- Culture Medium: M9 minimal medium supplemented with 2 g/L glucose.

- Inducing Agent: Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) stock solution (e.g., 10 mg/mL in DMSO).

- Centrifuge, microcentrifuge tubes, shaking incubator.

- Procedure:

- Grow an overnight culture of E. coli in M9 medium at 37°C with shaking (200 rpm).

- Sub-culture into fresh M9 medium to an OD600 of 0.05.

- Incubate until the culture reaches mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5).

- Add CCCP to a final concentration of 100 µg/mL.

- Incubate for 15 minutes at 37°C with shaking.

- Collect cells by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 3 min, room temperature).

- Wash the cell pellet three times with M9 medium (no carbon source) to remove CCCP completely.

- The resulting cell pellet is enriched for persisters and can be used immediately in downstream assays (e.g., metabolic tracing, antibiotic killing) [14].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening for Metabolic Resuscitation Adjuvants

This protocol outlines a cell-based screen to identify host-directed compounds that resuscitate intracellular S. aureus persisters [15].

- Principle: A bioluminescent reporter strain (JE2-lux) whose light output depends on cellular energy (ATP, NAD(P)H) is used to probe intracellular bacterial metabolic activity.

- Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Bioluminescent MRSA strain JE2-lux.

- Host Cells: Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) or relevant mammalian cell line.

- Assay Plates: 384-well plates, tissue culture-treated.

- Detection Instrument: Plate reader capable of measuring bioluminescence and a fluorescence/absorbance-based cell viability dye.

- Compound Library: A collection of drug-like molecules.

- Procedure:

- Infect macrophages with the JE2-lux strain at a suitable MOI (e.g., 10:1).

- Treat with gentamicin (typically 50 µg/mL) for 1-2 hours to kill extracellular bacteria.

- Wash cells to remove gentamicin and dispense infected macrophages into 384-well plates.

- Add compounds from the library to respective wells. Include controls: DMSO (vehicle), rifampicin (metabolic inhibition control).

- Incubate for 4 hours.

- Measure bioluminescence (bacterial metabolic activity) and a cell viability signal (host cytotoxicity) using the plate reader.

- Hit Selection: Primary hits are compounds that increase bioluminescence >1.5-fold over the vehicle control without reducing host cell viability [15].

- Secondary Screening: Confirm hits in a time-kill assay with a relevant antibiotic (e.g., rifampicin, moxifloxacin) to demonstrate enhanced killing of intracellular persisters.

Key Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Host-Directed Metabolic Resuscitation Pathway

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Persister Metabolic Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Persister Metabolism and Ribosome Biology

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Detail / Example |

|---|---|---|

| CCCP (Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone) | Chemical inducer of bacterial persistence by dissipating the proton motive force and depleting ATP. | Used at 100 µg/mL for 15 min to induce E. coli persisters reversibly [14]. |

| Stable Isotope Tracers (13C-Glucose, 13C-Acetate) | To measure metabolic flux in central carbon pathways (glycolysis, TCA cycle) in persister cells. | Tracer incorporation into metabolic intermediates and proteinogenic amino acids is measured via LC-MS/GC-MS [13] [14]. |

| Bioluminescent Reporter Strain (e.g., JE2-lux) | Real-time, non-invasive probing of intracellular bacterial metabolic activity and energy status. | Lux activity requires ATP and reducing equivalents (NAD(P)H, FMNH2), coupling light output to metabolism [15]. |

| KL1 (Host-Directed Compound) | A lead compound that resuscitates intracellular persisters by modulating the host immune response. | Suppresses host macrophage ROS/RNS production, alleviating a key inducer of bacterial metabolic shutdown [15]. |

| Ribosome Hibernation Analysis | Polysome profiling to assess the translational status of ribosomes (active polysomes vs. inactive monosomes). | Accumulation of 80S monosomes and loss of polysomes indicate translation shutdown and ribosome hibernation [17]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | High-resolution structural analysis of ribosomal conformational states during hibernation. | Can reveal changes like H69 rRNA rotation that prevent tRNA binding and disrupt translation initiation [17]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my persister cell enrichment not working, and how can I improve it?

Issue: Low yield of persister cells after enrichment protocols.

Answer: A low yield of persisters is often due to incomplete metabolic arrest or unintended resuscitation during handling. The key is to ensure full dormancy and avoid introducing nutrients.

- Confirm Stressor Efficacy: Verify that the concentration of your inducer (e.g., rifampicin, CCCP) is sufficient and the treatment duration is appropriate. For E. coli and P. aeruginosa, pretreatment with rifampicin (inhibits transcription), tetracycline (inhibits translation), or CCCP (uncouples oxidative phosphorylation) can convert nearly all exponential-phase cells into persisters, increasing persistence by up to 10,000-fold [18]. Always include a positive control.

- Minimize Resuscitation During Washing: Persister cells can resuscitate immediately upon exposure to fresh nutrients [18]. During the washing steps after antibiotic treatment, use a minimal buffer or spent medium instead of fresh, nutrient-rich medium to prevent accidental reactivation.

- Validate Dormancy: Use a metabolic dye like Redox Sensor Green to confirm low metabolic activity in the enriched population via flow cytometry [18].

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between (p)ppGpp-mediated persistence and Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) system-mediated persistence?

Issue: Uncertainty in identifying the primary molecular pathway responsible for persister formation in my experimental system.

Answer: While historically linked, current evidence suggests (p)ppGpp plays a more central and general role, while the involvement of specific TA modules under physiological conditions is less clear.

- Genetic Knockouts: Generate deletion mutants for key synthetases. A ΔrelA ΔspoT double mutant in E. coli is completely devoid of (p)ppGpp and should show a sharp decrease in persister formation upon amino acid starvation [19] [20]. In contrast, deletion of up to 10 or 12 type II TA systems in E. coli and Salmonella enterica has been shown to have no significant effect on persistence [18].

- Single-Cell Reporter Assays: Use fluorescent reporters to correlate persistence events with molecular activity. An RpoS-mCherry fusion can serve as a proxy for (p)ppGpp activity [19]. However, note that one study found no direct correlation between single-cell (p)ppGpp levels and antibiotic tolerance, suggesting the transcriptional response may be more critical than the alarmone level itself [19].

- Key Differentiator: The model that polyphosphate activates Lon protease to degrade antitoxins in a (p)ppGpp-dependent manner has been retracted and disputed by subsequent studies [18]. Therefore, a lack of persistence in a (p)ppGpp-deficient mutant, but persistence in a TA module deletion mutant, strongly implicates the stringent response.

FAQ 3: My bacterial cultures are not resuscitating consistently. What factors can affect Rpf efficiency?

Issue: Inconsistent or low resuscitation rates of dormant cells using Recombinant Rpf proteins.

Answer: Rpf efficacy is highly dependent on the physiological state of the dormant cells and the enzymatic activity of the Rpf protein.

- Confirm Rpf Activity and Concentration: Rpf is active at picomolar concentrations [21]. Use a positive control, such as dormant Micrococcus luteus, to verify the activity of your Rpf stock. Ensure your Rpf is properly stored and not degraded.

- Match Rpf to the Bacterial Species: The structure of peptidoglycan varies between Gram-positive and Gram-negative species, affecting which bonds Rpf can cleave [21]. The Rpf from M. luteus is most effective against other high G+C Gram-positive bacteria like mycobacteria. For other species, you may need an Rpf analogue (e.g., YeaZ in some Gram-negative bacteria) [21].

- Consider the Dormancy State: The "depth" of dormancy affects resuscitation. Cells in a deeper dormant state (e.g., VBNC) may require a longer exposure to Rpf or a combination of multiple resuscitation factors [11] [21]. Ensure other resuscitation conditions (temperature, minimal medium) are optimal.

Table 1: Key Molecular Initiators in Bacterial Persistence and Resuscitation

| Initiator | Full Name | Primary Role | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| (p)ppGpp | Guanosine pentaphosphate / tetraphosphate ("Magic Spot") | Central alarmone of the Stringent Response; induces a multidrug-tolerant, dormant state [18] [20]. | - A 16-fold increase in ppGpp levels upon valyl-tRNA synthetase inhibition led to a >1000-fold increase in persister formation [19]. - (p)ppGpp accumulation reprograms transcription, inhibits DNA primase and GTPases, and reduces ribosome synthesis [18] [20]. |

| Rpf | Resuscitation-Promoting Factor | Bacterial cytokine with peptidoglycan hydrolase activity; reactivates cells from dormancy [22] [21]. | - Picomolar concentrations of Rpf can increase the viable count of dormant M. luteus by >100-fold [21]. - In M. tuberculosis, the five Rpf genes (rpfA-E) are differentially expressed under various stresses (acid, hypoxia, nutrient starvation) to facilitate reactivation [22]. |

| cAMP | Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate | Secondary messenger; core regulator of catabolite repression and some stress responses. | Information from the provided search results was insufficient to populate this cell with specific findings related to persistence. Further research is required. |

Table 2: Common Methods for Persister Enrichment and Their Validation

| Method | Mechanism of Action | Reported Increase in Persistence | Key Validation Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin/Tetracycline/CCCP Pre-treatment | Stops transcription, translation, or ATP production, forcing cells into a dormant state [18]. | Up to 10,000-fold in E. coli and P. aeruginosa [18]. | Multi-drug tolerance, dormancy via metabolic dyes, immediate resuscitation with nutrients, no change in MIC [18]. |

| Amino Acid Starvation (e.g., valSts) | Induces (p)ppGpp synthesis via RelA in response to uncharged tRNA [19]. | 3 to 4 orders of magnitude in E. coli [19]. | RelA-dependence, stochastic persister formation, RpoS reporter induction [19]. |

| Toxin Overexpression (e.g., MqsR) | Induces growth arrest by cleaving mRNA or other essential cellular targets [18]. | Up to 14,000-fold for E. coli [18]. | Dependence on toxin catalytic activity, growth arrest, and antibiotic tolerance. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Inducing and Quantifying (p)ppGpp-Dependent Persisters via Amino Acid Starvation

This protocol uses a temperature-sensitive valyl-tRNA synthetase mutant (valSts) to trigger (p)ppGpp accumulation and persister formation in a controlled manner [19].

Key Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: E. coli MG1655 with valSts mutation (e.g., strain SEM3147).

- Antibiotics: Ampicillin sodium salt (or other cell-wall active antibiotic for killing).

- Equipment: Water bath or incubator for precise temperature control, plate reader or colony counter.

Methodology:

- Growth and Induction: Grow the valSts strain overnight at a fully permissive temperature (e.g., 30°C). Dilute the culture in fresh, pre-warmed medium and grow to mid-exponential phase at 30°C. Shift the culture to a semi-permissive temperature (e.g., 36.6°C) to partially inactivate ValS and induce amino acid starvation. Incubate for 60-90 minutes.

- Antibiotic Challenge: Take a sample of the induced culture and challenge it with a high concentration of ampicillin (e.g., 100 µg/mL, >10x MIC) for a defined period (e.g., 3-5 hours) to kill non-persister cells.

- Quantification of Persisters: After antibiotic treatment, wash the cells 2-3 times in sterile PBS or minimal buffer to remove the antibiotic. Serially dilute and spot the cells onto LB agar plates. Incubate the plates at the permissive temperature (30°C) for 24-48 hours to allow surviving persisters to resuscitate and form colonies. Count the Colony Forming Units (CFU) to determine the number of persisters.

- Control Strains: Always include control strains in parallel: the wild-type MG1655 and a ΔrelAvalSts double mutant. The latter should show a significant reduction in persister formation, confirming RelA/(p)ppGpp dependence [19].

Protocol 2: Assessing Persister Cell Recovery Kinetics

This protocol outlines steps to study the resuscitation of persister cells after antibiotic removal at the single-cell level [23].

Key Materials:

- Bacterial Culture: A purified population of persister cells.

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer for bulk growth measurement, Flow cytometer with capability for metabolic staining (e.g., Redox Sensor Green).

- Reagents: Appropriate culture medium, metabolic dyes.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Obtain persister cells using a time-kill assay with a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic. Ensure >99.9% killing of the initial population. Thoroughly wash the cells to remove the antibiotic.

- Bulk Recovery Kinetics: Resuspend the persister cells in fresh, pre-warmed medium. Immediately transfer the suspension to a cuvette and place it in a spectrophotometer. Monitor the optical density (OD600) continuously with shaking. The lag time before resumption of growth is a key parameter of persister recovery.

- Single-Cell Physiological States: In parallel, take samples at regular time points (e.g., every 30-60 minutes) during the recovery phase. Stain these samples with a metabolic dye like Redox Sensor Green and analyze them via flow cytometry. This allows you to track the heterogeneity in metabolic activity as the population transitions from dormancy to active growth [23].

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Pathway from Stress to Persistence and Resuscitation

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Persister Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Molecular Initiators of Persistence

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Use Case | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| valSts E. coli Strain | Temperature-sensitive valyl-tRNA synthetase; induces (p)ppGpp synthesis at restrictive temperatures [19]. | Controlled, RelA-dependent induction of persister cells via amino acid starvation. | Requires precise temperature control. A ΔrelAvalSts double mutant is a critical control. |

| RpoS-mCherry Reporter | Fluorescent reporter for (p)ppGpp activity and the general stress response [19]. | Monitoring stringent response activation at the single-cell level in relation to persistence events. | Correlation with (p)ppGpp levels may not be perfect; it reports on the downstream transcriptional response. |

| Recombinant Rpf Protein | Peptidoglycan hydrolase that cleaves bonds in the cell wall to stimulate resuscitation [22] [21]. | Reactivating dormant (including VBNC) cells in culture to study resuscitation mechanisms. | Activity is species-specific due to peptidoglycan structural variation. Use picomolar concentrations. |

| QUEEN-7µ ATP Sensor | Genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor for intracellular ATP concentration [19]. | Correlating ATP levels with persister formation and resuscitation at single-cell resolution. | Allows monitoring of metabolic state without disrupting cells. |

| Metabolic Dyes (e.g., Redox Sensor Green) | Fluorescent dyes that report on metabolic (redox) activity. | Differentiating and isolating dormant (low metabolism) cells from active cells via flow cytometry [18]. | Useful for validating enrichment protocols and analyzing population heterogeneity during recovery. |

| Membrane-Active Compounds (e.g., CD437, CD1530) | Disrupts membrane integrity and proton motive force (PMF) [24]. | Used in combination with conventional antibiotics to sensitize persister cells by enhancing drug uptake. | Shows synergistic killing when combined with aminoglycosides against MRSA persisters [24]. |

Advanced Workflows: Single-Cell and Omics Techniques for Monitoring Resuscitation Dynamics

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the key advantage of using flow cytometry over CFU counting for studying bacterial persister resuscitation?

Flow cytometry provides single-cell resolution, allowing you to detect heterogeneous subpopulations and transient physiological states that are invisible to conventional Colony Forming Unit (CFU) counts. While CFU counts only detect cells capable of replication on a plate, flow cytometry can identify viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells and dormant subpopulations through metabolic markers and membrane integrity assays. This high-resolution is critical, as studies have shown that cells can regain metabolic activity and resuscitate even when conventional culture methods indicate complete inactivation [25] [26].

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between true resuscitation and non-specific staining during a persister recovery time-course?

To reliably distinguish resuscitation, employ a multi-parameter staining panel. Combine a membrane integrity dye (like PI) with a marker for metabolic activity (like CFDA or a redox-sensitive dye). A resuscitating cell will transition from PI-positive/CFDA-low to PI-negative/CFDA-high. Always include controls: an unstained sample to set autofluorescence baselines, a killed population (e.g., disinfectant-treated) as a dead cell control, and a healthy, growing culture as a live cell control. The use of a metabolic activity dye was key in a study on Mycobacterium bovis BCG to confirm the sublethal effect of a disinfectant and subsequent resuscitation [26].

FAQ 3: My flow cytometry data shows a high background in the negative cell populations. What could be the cause and how can I resolve it?

High background in negative populations is often caused by non-specific antibody binding or the presence of dead cells. You can address this by:

- Blocking Fc Receptors: Use Bovine Serum Albumin, Fc receptor blocking reagents, or normal serum from the same host as your antibodies prior to staining [27].

- Gating Out Dead Cells: Use a viability dye such as Propidium Iodide (PI) or 7-AAD to identify and gate out dead cells during live cell surface staining. For fixed cells, use fixable viability dyes [27].

- Optimizing Washes: Perform additional wash steps between antibody incubations to remove unbound antibody [27].

FAQ 4: What are the critical steps in sample preparation to ensure accurate tracking of persister cell recovery?

The key is to preserve the physiological state of the cells at the moment of sampling.

- Gentle Handling: Avoid bubbles, vigorous vortexing, and excessive centrifugation to prevent mechanical stress and cell damage [28].

- Rapid Fixation (if required): If you need to pause an experiment for batch analysis, add fixative immediately after sampling. Cross-linking fixatives like 4% formaldehyde are recommended to inhibit enzymatic activity and preserve cell structures [27].

- Consistent Timing: For time-course experiments, process each sample at the same interval after collection to ensure comparability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Weak or No Fluorescence Signal

| Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Inadequate fixation/permeabilization | For intracellular targets, ensure you use the appropriate fixation and permeabilization method. For cytosolic antigens, mild detergents like saponin may suffice, while nuclear antigens may require harsher detergents like Triton X-100 [27] [28]. |

| Suboptimal antibody concentration | Titrate your antibodies to determine the optimal concentration. Over-dilution can lead to weak signals, while over-concentration can cause high background [27]. |

| Instrument laser/PMT settings | Verify that the flow cytometer's laser wavelength and photomultiplier tube (PMT) settings are correctly configured for the fluorochromes you are using [27]. |

| Low expression of the target | Pair a low-density target with the brightest possible fluorochrome (e.g., PE) to maximize detection sensitivity [27]. |

Problem: Unclear Separation Between Live, Dead, and Resuscitating Populations

| Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Reliance on a single dye | Use a multi-parametric viability stain. The LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit, for example, uses SYTO9 and PI to differentiate cells with intact membranes (green), damaged membranes (red), and those with intermediate states [25]. |

| Incorrect gating strategy | Use a forward scatter (FSC) vs. side scatter (SSC) plot to gate on your primary bacterial population. Then, use fluorescence plots from single-stained controls to set the boundaries for positive and negative populations accurately. |

| Cell aggregation | Pass your cell suspension through a narrow-gauge needle or filter it through a cell strainer before running it on the cytometer to ensure a single-cell suspension and avoid doublet artifacts. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents used in flow cytometry protocols for studying bacterial persistence and resuscitation.

| Item | Function/Application in Persister Research |

|---|---|

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | A membrane-impermeant DNA dye that only enters cells with compromised membranes, labeling dead cells. It is a standard for assessing membrane integrity [25] [27]. |

| SYTO9 | A cell-permeant green fluorescent nucleic acid stain that labels all cells in a population. Used in combination with PI for viability assessment [25]. |

| Fixable Viability Dyes | Amine-reactive dyes that covalently bind to proteins in dead cells before fixation. They allow for the exclusion of dead cells during subsequent intracellular staining procedures [27] [28]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Buffer | Used to block Fc receptors on immune cells (e.g., in PBMCs co-cultured with bacteria) to prevent non-specific antibody binding and reduce background signal [27]. |

| Paraformaldehyde (PFA) | A cross-linking fixative used to preserve cell structure and immobilize intracellular components at a specific time point, crucial for time-course experiments [27] [28]. |

| Permeabilization Detergents | Agents like Saponin (mild) or Triton X-100 (harsh) are used to permeabilize cell membranes after fixation, allowing antibodies to access intracellular targets for staining [27] [28]. |

Experimental Workflow & Data Analysis

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to assess persister recovery and is ideal for tracking resuscitation in real-time [23].

- Persister Generation: Treat a mid-logarithmic phase bacterial culture with a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., a fluoroquinolone or aminoglycoside) for a defined period (e.g., 3-5 hours).

- Wash-Out: Pellet the cells by centrifugation and wash twice with fresh, pre-warmed medium to remove the antibiotic thoroughly.

- Resuscitation and Staining: Resuspend the cell pellet in fresh medium to initiate resuscitation. At regular intervals (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120, 240 minutes), withdraw aliquots and immediately incubate them with your chosen fluorescent dye panel (e.g., SYTO9 and PI).

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Analyze the stained samples on a flow cytometer. For each time point, collect at least 10,000 events. Use FSC vs. SSC to gate on the bacterial population.

- Data Interpretation: Plot the fluorescence data over time. A successful resuscitation will show a population shift from a primarily PI-positive state (dead) to a SYTO9-positive/PI-negative state (live) as cells repair their membranes and resume activity.

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a typical experiment for tracking persister cell resuscitation.

This diagram maps the physiological transitions of a bacterial cell during the resuscitation process, as determined by flow cytometry parameters.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our 13C-labeling data from persister cell cultures shows very low enrichment, making flux estimation unreliable. What could be the cause? Low isotopic enrichment is a common challenge when working with dormant cells. Potential causes and solutions include:

- Low Metabolic Activity: Persister cells exhibit drastically reduced metabolic rates. Ensure you are using a sufficiently high density of persister cells (e.g., OD600 of 5 as used in successful protocols) to obtain measurable signals [14].

- Insufficient Labeling Time: The metabolic slowdown means label incorporation is delayed. Extend the labeling time course and include early time points (e.g., 20 seconds, 5 minutes) to capture slow labeling dynamics, not just endpoint measurements [14].

- Tracer Choice: If using acetate as a carbon source, be aware that persister cells show a more substantial metabolic shutdown compared to glucose. Substrate inhibition and high ATP demands for acetate activation can further reduce metabolic activity. Using 13C-glucose may yield better results [14].

Q2: How can we differentiate metabolic fluxes between different species in a mixed microbial community? Traditional 13C-MFA using amino acid labeling patterns cannot distinguish between species in a community. A promising solution is a peptide-based 13C-MFA method. This approach leverages high-throughput proteomics to:

- Identify the origin of a peptide, linking it to a specific species in the community.

- Use the peptide's labeling pattern to infer intracellular fluxes for that specific organism, as the peptide labeling is derived from its constituent amino acids [29]. This method allows for the simultaneous quantification of species-specific metabolic fluxes and metabolite exchange within a community.

Q3: What software tools are available for 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis, and which is best for beginners? Several software tools are available, ranging from those requiring expert knowledge to more user-friendly options.

| Software Tool | Key Features | Best For | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| INCA / Metran | User-friendly; preferred for quantitative flux maps in mammalian and microbial cells. | Cancer biologists and researchers without extensive coding/math backgrounds. | [30] |

| BiGGR | An R/Bioconductor package; integrates with gene expression data and metabolic databases. | R users who want to combine flux analysis with other 'omics' data. | [31] [32] |

| WUflux | An open-source solution for steady-state flux calculations. | Researchers needing a free, dedicated platform for flux calculations. | [33] |

Q4: The fluxes in our persister cell cultures do not seem to be at a metabolic steady state. Can we still perform 13C-MFA? Yes. Standard 13C-MFA often assumes both metabolic and isotopic steady state. However, persister cell resuscitation is a dynamic process. In such cases, Isotopically Non-Stationary 13C-MFA (INST-MFA) is the appropriate method. INST-MFA does not require the system to be at an isotopic steady state and uses early time-point labeling data to estimate fluxes, making it ideal for studying dynamic processes like resuscitation [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent or Implausible Flux Results

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Flux Resolution | Limited labeling data for upper metabolism (PPP, glycolysis). | Incorporate labeling measurements of glycogen and RNA. The glucose and ribose moieties provide direct information on G6P and R5P pools, greatly improving flux observability in pentose phosphate and glycolytic pathways [35]. |

| High Uncertainty in Flux Estimates | The flux solution is underdetermined; many flux distributions fit the data equally well. | Use ensemble modeling (e.g., via BiGGR) to sample the space of possible flux solutions. This quantifies uncertainty and provides confidence intervals for each estimated flux [32]. |

| Violation of Steady-State Assumption | The cell culture is not in a metabolic steady state during the labeling experiment. | * Ensure constant growth and nutrient conditions before starting the tracer experiment.* If studying a dynamic process like resuscitation, switch to INST-MFA [34]. |

Issue: Challenges in Sample Preparation and Measurement

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Abundance of Metabolites | Rapid quenching and efficient extraction are critical, especially for low-concentration intracellular metabolites. | * Rapid Quenching: Use a cold methanol-water solution and liquid nitrogen to stop metabolic activity within seconds [14].* Efficient Extraction: Use an 80:20 methanol-water extraction solution at -20°C [14]. |

| Difficulty Measuring PPP Intermediates | Low concentrations of metabolites like erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P) make direct measurement hard. | Rely on proteinogenic amino acids as proxies. For example, phenylalanine labeling provides information on E4P and PEP pools. For mammalian cells that don't synthesize phenylalanine, use labeling of lower glycolytic intermediates like 3PG [35] [30]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: 13C-Labeling of Bacterial Persister Cells

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating the metabolic state of E. coli persister cells induced by CCCP [14].

1. Persister Cell Induction and Preparation

- Culture: Grow E. coli BW25113 in M9 minimal medium with 2 g/L glucose.

- Induction: At mid-exponential phase (OD600 ~0.5), expose cells to 100 µg/mL of CCCP for 15 minutes at 37°C with shaking.

- Washing: Collect cells by centrifugation and wash three times with M9 medium without a carbon source to remove CCCP and residual metabolites.

2. Tracer Experiment

- Resuspension: Concentrate control and persister cells to a high density (OD600 of 5) in 10 mL of M9 medium.

- Labeling: Initiate the experiment by adding 2 g/L of a 13C-labeled tracer (e.g., 1,2-13C2 glucose or 2-13C sodium acetate).

- Time Course: Incubate at 37°C and collect samples at specific timepoints (e.g., 0, 20 s, 5 min, 30 min, 2 h) to capture labeling dynamics.

- Quenching: For each timepoint, immediately cool samples in liquid nitrogen to stop metabolic activity.

3. Sample Processing for LC-MS/MS Analysis

- Metabolite Extraction:

- Lyophilize the quenched cell pellet.

- Add 0.5 mL of 80:20 methanol-water extraction solution and incubate at -20°C for 1 hour.

- Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 0°C.

- Filter the supernatant through a 0.2 µm filter for LC-MS analysis of free metabolites.

- Proteinogenic Amino Acid Analysis:

- Hydrolyze the remaining cell pellet with 6 N HCl at 100°C for 18 hours.

- Derivatize the hydrolyzed amino acids using the TBDMS method for GC-MS analysis [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and software for conducting 13C-MFA in persister cell studies.

| Category | Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inducers | Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) | A protonophore used to induce a reversible state of persistence by disrupting the membrane potential and ATP synthesis, without permanent damage [14]. |

| Isotopic Tracers | 1,2-13C2 Glucose; 2-13C Sodium Acetate | Essential substrates for tracing carbon fate. Glucose is a core substrate; acetate can reveal distinct metabolic shutdowns in persisters [14]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS (Q-Exactive system) & GC-MS | Used to measure the 13C-labeling patterns of free metabolic intermediates (via LC-MS) and proteinogenic amino acids (via GC-MS after derivatization) [14]. |

| Analytical Columns | Agilent InfinityLab Poroshell 120 HILIC-Z | A hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) column effective for separating polar metabolites for LC-MS analysis [14]. |

| Flux Analysis Software | INCA, Metran, WUflux, BiGGR | Software tools that use labeling data and external rates to compute quantitative intracellular flux maps [34] [33] [30]. |

Data Inputs and External Rate Calculations for 13C-MFA

Successful flux analysis requires precise measurement of external rates, which constrain the possible intracellular flux distributions [30].

| Parameter | Measurement Method | Calculation Formula | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate (μ) | Tracking cell number (Nx) over time. | μ = (ln Nx,t2 - ln Nx,t1) / ΔtDoubling time: t_d = ln(2) / μ | For persister resuscitation, monitor the lag phase and the onset of growth. |

| Nutrient Uptake / Product Secretion Rates (r_i) | Measuring metabolite concentration (Ci) in the media over time. | For growing cells:r_i = 1000 · μ · V · ΔCi / ΔNxUnits: nmol/10^6 cells/h | Correct glutamine uptake rates for spontaneous degradation in the media [30]. |

Data Analysis Pathway for 13C-MFA

Transcriptomic and Proteomic Profiling of Awakening Persisters

Bacterial persister cells represent a transient, non-growing (or slow-growing) subpopulation within an isogenic culture that exhibits remarkable tolerance to high concentrations of bactericidal antibiotics. These cells are not genetically resistant but rather exist in a phenotypic state of dormancy that enables survival during antibiotic exposure. Upon removal of the antibiotic stress, a subpopulation of these persister cells can resuscitate and resume normal growth, leading to relapse of infections. This resuscitation process represents a critical phase in the persister life cycle and understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying awakening is fundamental to developing novel therapeutic strategies against chronic and recurrent bacterial infections. The following technical support guide addresses key methodological considerations and frequent challenges encountered when investigating the transcriptomic and proteomic profiles of persister cells during this crucial awakening phase, providing a structured troubleshooting framework for researchers in the field.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Persister Resuscitation Studies

| Problem Area | Specific Challenge | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persister Isolation | Low persister yields after antibiotic treatment | Incorrect antibiotic concentration or exposure time; Insufficient initial population heterogeneity | - Determine Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) first; Use 10-100x MIC [36].- Use stationary-phase cultures or stress pre-treatment (e.g., CSP pheromone in S. mutans) to induce persistence [36]. |

| Contamination with viable non-persisters | Incomplete killing of non-persister cells | - Include viability staining (e.g., propidium iodide) with colony counts [6].- Validate with time-kill curves extending beyond 24 hours [11]. | |

| Transcriptomic Profiling | Low RNA yield/quality from persisters | Extremely low transcriptional activity in deep persisters; RNA degradation | - Use single-cell RNA-seq techniques (e.g., PETRI-seq) designed for low-biomass samples [37].- Implement rigorous RNA integrity assessment (RIN > 7.0) [36]. |

| High background noise in data | Residual ribosomal RNA dominates limited transcript pool | - Employ Cas9-driven ribosomal RNA depletion in protocol [37].- Apply downsampling bioinformatic normalization to equalize mRNA counts per cell [37]. | |

| Proteomic Analysis | Insufficient protein material for LC-MS/MS | Low protein synthesis in dormant persisters | - Use pulsed-SILAC labeling to identify de novo protein synthesis during recovery [38] [39].- Scale up persister cell isolation volumes to milligram quantities. |

| Resuscitation Triggering | Inconsistent awakening kinetics between replicates | Stochastic nature of resuscitation; Inadequate trigger consistency | - Standardize resuscitation media (e.g., using L-glutamic acid for V. splendidus) [40] [41].- Monitor single-cell resuscitation dynamically using microscopy [40]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What defines a "persister cell" in the context of resuscitation studies, and how does it differ from antibiotic-resistant cells or VBNC cells?

Persisters are genetically drug-susceptible phenotypic variants that survive antibiotic exposure by entering a transient, non-growing state. Unlike resistant cells, persisters do not have a higher Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and the phenotype is not heritable. Upon antibiotic removal, a subpopulation can resuscitate. In contrast, Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) cells typically require specific, complex resuscitation signals and may represent a deeper state of dormancy, though the boundaries between these states can be fluid [11] [42].

Q2: My transcriptomic data shows persisters have very low overall mRNA content. How can I be sure that the transcriptional signals I detect are biologically relevant and not just noise?

This low mRNA content is a genuine characteristic of the dormant state. To ensure robustness:

- Technical Replication: Perform multiple independent persister isolations and sequencing runs to distinguish consistent signals from stochastic noise [37].

- Spike-in Controls: Use external RNA controls to normalize for technical variation.

- Validation: Confirm key findings via orthogonal methods, such as transcriptional fusions to validate promoter activity or qRT-PCR on selected genes [37].

- Statistical Rigor: Apply stringent false discovery rate corrections in differential expression analysis.

Q3: What are the key proteomic changes I should focus on when studying the initial hours of persister resuscitation?

Proteomic studies indicate that the early resuscitation phase involves a coordinated upregulation of specific functional protein categories. Key changes to monitor include:

- Metabolic Reactivation: Proteins involved in central carbon metabolism (e.g., amino acid metabolism like arginine, L-glutamic acid utilization) [40] [41].

- Cellular Repair: Proteins for cell envelope and peptidoglycan biosynthesis [40] [41].

- Stress Detoxification: Antioxidant proteins like alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpF) [38] [39].

- Ribosome Assembly: While ribosomes may be downregulated initially, factors for ribosome preservation and resuscitation are critical [40] [6].

Q4: Are persister cells truly metabolically dormant, or is there activity I should account for in my experimental design?

Emerging evidence challenges the traditional view of complete metabolic inactivity. While persisters are non-growing, they can maintain a basal level of metabolism and can even actively respond to their environment. Studies show that persister cells can:

- Undergo new RNA synthesis during antibiotic exposure, indicating active transcription [42].

- Synthesize specific proteins in response to stress, such as those involved in protection against ampicillin-induced damage [38]. This residual metabolic activity means researchers should consider the potential for active gene regulation during the persistence phase itself, not just during resuscitation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Transcriptomic and Proteomic Profiling

This protocol is designed for isolating stress-induced persisters for subsequent transcriptomic analysis, using the CSP pheromone system in S. mutans as a model for triggered persistence.

Culture Preparation:

- Grow the bacterial strain (e.g., S. mutans UA159) overnight in an appropriate rich medium (e.g., THYE).

- Dilute the overnight culture 1:100 in 200 mL of fresh pre-warmed medium.

- Induce persistence by adding the trigger (e.g., 50 ng/mL CSP pheromone). Incubate for 2 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

Antibiotic Selection:

- Treat the culture with a lethal dose of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., 20 µg/mL ofloxacin, 10x MIC) for 22 hours to kill all non-persister cells.

- Critical: Determine the MIC for your strain and antibiotic beforehand. Use concentrations significantly above the MIC (10-100x).

Persister Collection and Washing:

- Centrifuge the antibiotic-treated culture to pellet cells.

- Wash the pellet thoroughly with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at least twice to completely remove the antibiotic.

- Resuspend the final pellet (containing the persister population) in a suitable buffer for RNA extraction.

RNA Extraction and Quality Control:

- Use a commercial kit designed for bacterial RNA extraction (e.g., RiboPure-Bacteria Kit).

- Treat the extracted RNA with DNase (e.g., RQ1 DNase) to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Assess RNA quality using an instrument such as an Agilent Bioanalyzer. Proceed only with samples having an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) of 7.0 or higher.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Use a ribosomal RNA depletion kit (e.g., Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus) to enrich for mRNA.

- Prepare sequencing libraries and sequence on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq for 75 bp paired-end reads).

This protocol outlines the steps for a label-free quantitative proteomics approach to characterize the proteome of persister cells during the recovery phase.

Generation and Isolation of Persisters:

- Generate a high-persister strain or use wild-type strains under persistence-inducing conditions (e.g., stationary phase, toxin overexpression).

- Treat the culture with a high concentration of antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin) for a defined period to eliminate growing cells.

- Wash the surviving persisters with PBS to remove the antibiotic.

Initiation of Resuscitation and Sample Collection:

- Resuspend the persister pellet in fresh, pre-warmed recovery medium.

- Incubate under optimal growth conditions to allow resuscitation.

- Collect samples at critical time points during recovery (e.g., T=0h, T=1h, T=3h) by centrifugation. Snap-freeze cell pellets in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C.

Protein Extraction and Digestion:

- Lyse the frozen cell pellets using a strong denaturant (e.g., urea or SDS) in combination with physical disruption (e.g., bead beating or sonication).

- Reduce and alkylate cysteine residues.

- Digest the protein extract into peptides using a sequence-grade protease, typically trypsin.

LC-MS/MS Analysis and Data Processing:

- Analyze the digested peptides by Liquid Chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Acquire data in a data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode.

- Identify and quantify proteins by searching the MS/MS spectra against a protein database for the organism using specialized software (e.g., MaxQuant).

- Perform statistical analysis to identify proteins with significantly altered abundance across the different recovery time points.

The following diagrams illustrate the core experimental workflow for profiling awakening persisters and the key molecular pathways active during their resuscitation.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for profiling awakening persisters.

Diagram 2: Key pathways activated during persister resuscitation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Persister Resuscitation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Specific Example(s) | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Induction Compounds | CSP Pheromone (for S. mutans) [36], L-Glutamic Acid (for V. splendidus) [40] [41] | Used to trigger or induce the formation of persister cells in a population prior to antibiotic selection. |

| Bactericidal Antibiotics | Ofloxacin [36], Ampicillin [37] [38], Ciprofloxacin [37] | Applied at high concentrations (10-100x MIC) to selectively kill non-persister cells, thereby isolating the tolerant persister subpopulation. |

| RNA Stabilization & Extraction Kits | RNAwiz, RiboPure-Bacteria Purification Kit [36] | Critical for preserving the often low-abundance and labile RNA transcriptome of persister cells immediately upon lysis. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero Plus [36] | Used during RNA-seq library preparation to remove abundant ribosomal RNA, thereby enriching for mRNA and improving sequencing depth of the transcriptome. |

| Proteomic Buffers & Enzymes | Urea/SDS Lysis Buffers, Trypsin [38] [39] | For the efficient extraction, denaturation, and digestion of proteins from persister cells into peptides suitable for LC-MS/MS analysis. |

| Stable Isotope Labels (SILAC) | Heavy Isotope-labeled Amino Acids (Lysine, Arginine) [38] [39] | Enables pulsed-SILAC proteomics to track and quantify de novo protein synthesis during the resuscitation process, distinguishing it from pre-existing proteins. |

Standardized Protocols for Enriching, Isolating, and Resuscitating Persisters In Vitro

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: Why is my persister enrichment low after antibiotic treatment? A low persister yield often stems from an incorrectly determined Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) or an insufficient antibiotic treatment duration. The persister fraction only becomes apparent after the majority of susceptible cells have been killed.

- Solution:

- Confirm the MIC: Re-conduct a susceptibility test to ensure the antibiotic concentration is appropriate. A common practice is to use a concentration of at least 10 times the MIC to eliminate all non-persister cells [43].

- Perform a Time-Kill Assay: Establish a biphasic killing curve. The persister plateau is reached when the number of viable cells stabilizes over time despite continued antibiotic exposure. The duration to reach this plateau must be determined for each strain and antibiotic combination [43] [11].

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between persisters and viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells during resuscitation? This is a common challenge as both cell types appear alive with standard viability stains but do not immediately form colonies. The key difference is that persisters can resuscitate in standard culture media upon antibiotic removal, while VBNC cells typically cannot [9].

- Solution: Use a protein dilution method with flow cytometry.

- Induce expression of a stable fluorescent protein (e.g., mCherry) in your culture.

- Treat the cells with ampicillin, which lyses growing cells but leaves non-growing persisters and VBNC cells intact and fluorescent.

- After washing away the antibiotic, monitor the culture in fresh media without the inducer.

- Persisters will dilute the fluorescent protein as they divide, showing a decrease in fluorescence. VBNC cells will retain high fluorescence as they do not divide [9].

FAQ 3: My persister cells are not resuscitating consistently. What could be the cause? Inconsistent resuscitation can be due to the metabolic state of the persisters or the composition of the recovery medium.

- Solution:

- Optimize the Carbon Source: Research shows that persister cells have a reduced metabolic state, and their ability to resuscitate is highly dependent on the available carbon source. For example, E. coli persisters resuscitate more readily on glucose than on acetate [44] [13].

- Standardize Pre-culture Conditions: The length of the stationary phase in the pre-culture can affect the physiological state of persisters. Ensure consistent and documented pre-culture conditions [9].

- Confirm Recovery Time: Flow-cytometry data indicates that ampicillin persisters of E. coli can begin resuscitation within 1 hour after transfer to fresh media, with a doubling time similar to normal cells (~23 minutes) [9].

FAQ 4: Are there non-antibiotic-based methods to isolate persisters? Yes, traditional methods rely on antibiotics, which can themselves induce a stress response. Alternative protocols can reduce this potential bias.

- Solution: A lytic protocol using a combination of alkaline and enzymatic lysis (e.g., a commercial miniprep lysis solution and lysozyme) can rapidly kill normally growing cells based on their physiological state, leaving persister cells intact. This method is faster (under 45 minutes) and allows for the differentiation between Type I (stationary phase) and Type II (spontaneously generated during growth) persisters [45].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Time-Kill Curve

This is a foundational protocol for any persister study, as detailed in [43].

Method:

- Susceptibility Test (MIC):

- Prepare a two-fold dilution series of the antibiotic in a 96-well plate.

- Inoculate each well with a standardized bacterial inoculum (approx. 5x10^5 CFU/mL).

- Incubate for 16-20 hours.

- The MIC is the lowest antibiotic concentration that completely inhibits growth, determined by measuring OD595 and comparing it to a positive control [43].

- Time-Kill Assay:

- Expose a bacterial culture to a lethal dose of antibiotic (e.g., 10x MIC).

- Take 1 mL aliquots at regular time intervals (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 6, 24 hours).

- Serially dilute each aliquot and plate on non-selective agar to determine Colony Forming Units (CFU).

- Plot log(CFU/mL) over time. The point where the curve stabilizes indicates the "persister plateau" [43] [11].

Protocol 2: Isolating and Resuscitating Persisters for Downstream Analysis

This protocol combines established antibiotic treatment with monitoring techniques.

Method:

- Persister Isolation:

- Treat a mid-exponential or stationary-phase culture with a lethal antibiotic concentration (e.g., 100 µg/mL ampicillin for E. coli) for a duration determined from the time-kill curve (e.g., 3 hours) [43] [9].

- Centrifuge the sample to sediment the cells and wash the pellet twice with fresh medium or phosphate-buffered saline to remove the antibiotic thoroughly.

- Resuscitation and Monitoring:

- Resuspend the pellet in fresh, pre-warmed culture medium.

- To monitor resuscitation, you can:

- Measure CFU: Plate samples at regular intervals to track the recovery of cultivable cells.

- Use Flow Cytometry: Employ the protein-dilution method described in FAQ 2 to track the division of individual persister cells in real-time [9].

The workflow for isolating and monitoring persister cells is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents and their functions in persister cell research.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Persister Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Amikacin / Ofloxacin | Antibiotics used for persister enrichment via time-kill assays. | Mode of action is important. Amikacin (aminoglycoside) is often used for E. coli. Determine the specific MIC for your strain [43]. |

| Carbon Sources (e.g., 13C-Glucose, 13C-Acetate) | To study the metabolic state of persisters and their substrate preferences during resuscitation using isotopic tracing [44] [13]. | Persister metabolism is carbon-source-dependent. Glucose often supports better resuscitation than acetate [44]. |

| Carbonyl Cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) | A chemical inducer of persister formation. It dissipates the proton motive force, leading to dormancy [44] [13]. | Useful for generating a synchronized persister population without using antibiotics, reducing potential stress-response biases [44]. |