Probing Biofilm Dynamics in Liquid: How Physiological AFM is Revolutionizing Antimicrobial Research

This article explores the transformative role of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) performed under physiological, fluid conditions in advancing biofilm research.

Probing Biofilm Dynamics in Liquid: How Physiological AFM is Revolutionizing Antimicrobial Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) performed under physiological, fluid conditions in advancing biofilm research. Biofilms, structured microbial communities responsible for up to 80% of human microbial infections and a major contributor to antimicrobial resistance, present a significant challenge in healthcare and drug development. Traditional imaging techniques often fail to capture their native structure and real-time functionality. This review details how fluid-phase AFM provides unprecedented, nanoscale insights into biofilm architecture, mechanical properties, and the efficacy of anti-biofilm agents in conditions that mimic the human body. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content covers foundational principles, methodological applications for evaluating novel therapies, troubleshooting for experimental fidelity, and validation against established techniques, ultimately outlining a path for accelerating the discovery of much-needed anti-biofilm strategies.

Understanding the Biofilm Challenge: Why Physiological Imaging is Non-Negotiable

Biofilms are structured microbial communities encased in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix, which confer significant resistance to antimicrobial treatments and environmental stresses. This resilience is a primary contributor to persistent infections and treatment failures in clinical settings. The architecture of resistance in biofilms is a multi-faceted phenomenon, primarily governed by three interconnected pillars: the physical and chemical barrier provided by the EPS matrix, the presence of dormant persister cells, and the physiological heterogeneity that arises from nutrient and oxygen gradients within the biofilm structure. Understanding this architecture requires advanced analytical techniques capable of operating under physiologically relevant conditions. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) in fluids has emerged as a powerful tool for dissecting these mechanisms, providing unprecedented nanoscale resolution of biofilm topology, mechanics, and cellular responses in their native, hydrated state. This Application Note details how AFM under physiological conditions can be leveraged to quantitatively probe the structural and functional basis of biofilm resistance, providing researchers with robust protocols for high-resolution analysis.

Application Notes: Probing the Pillars of Resistance with AFM

The EPS Matrix: A Structural and Functional Barrier

The EPS matrix is a complex amalgam of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids that forms the foundational scaffold of a biofilm. It functions as a mechanical shield, a diffusion modifier, and a platform for intercellular communication. AFM enables direct investigation of the EPS's nanomechanical properties and its role in biofilm cohesion and protection.

- Topographical Mapping: AFM in liquid can resolve the dense, heterogeneous topology of the EPS matrix, revealing its organization around bacterial cells. This allows for the visualization of pores, channels, and structural variations that influence diffusion and confer protection [1].

- Nanomechanical Characterization: By operating in force-volume mode, AFM can quantify the elasticity (Young's modulus) and adhesion of the EPS matrix. Stiffer, more cohesive matrices are often correlated with enhanced resistance to mechanical disruption and antibiotic penetration [1].

- Practical Implication: Measurements have shown that the physical properties of the EPS can create a diffusion barrier, reducing the penetration of antimicrobial agents and contributing to tolerance at the community level.

Persister Cells: The Dormant Reservoir

Persister cells are a small, phenotypically variant subpopulation of metabolically dormant cells that exhibit exceptional tolerance to high doses of bactericidal antibiotics. They are not genetically mutant but are responsible for the recalcitrance of chronic infections and biofilm-related relapses.

- Morphological and Mechanical Profiling: AFM can detect and characterize persister cells within a population based on their distinct physical properties. Studies on E. coli persisters have revealed critical phenotypic adaptations, summarized in Table 1 [2].

- Single-Cell Analysis: The capability of AFM to probe single cells allows for the direct comparison of persisters against their susceptible counterparts, linking morphological changes like cell shrinkage to the dormant state and reduced antibiotic uptake [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Changes in E. coli Persister Cell Properties in Response to Ampicillin (20x MIC)

| Property | Strain A5 (vs. Untreated) | Strain A9 (vs. Untreated) | Proposed Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Surface Area | 1.3-fold Decrease | 1.4-fold Decrease | Reduced surface for antibiotic interaction; dormancy |

| RMS Roughness | 1.2-fold Increase | 1.6-fold Increase | Altered surface topography, potentially affecting molecule adhesion |

| Adhesion Force | 3.4-fold Increase | 4.4-fold Increase | Enhanced cell-surface or cell-cell attachment |

| Elasticity (Stiffness) | 3.3-fold Increase | 4.5-fold Increase | Increased membrane rigidity and reduced permeability |

| Surface Biopolymer Thickness | 1.2-fold Decrease | 1.6-fold Decrease | Collapsed surface polymers minimizing interaction with antibiotics |

Physiological Heterogeneity: Gradients and Microenvironments

Biofilms are not homogeneous entities. Gradients of nutrients, oxygen, and waste products create a mosaic of microenvironments, leading to heterogeneous metabolic activity and varied bacterial responses to antibiotics. Cells in the nutrient-depleted, anaerobic core of a biofilm often display reduced metabolic activity, directly contributing to antibiotic tolerance.

- Spatial Mapping: Large-area automated AFM, combined with machine learning for image stitching, can correlate topographical features with local mechanical properties across millimeter-scale areas, revealing the spatial distribution of heterogeneous microenvironments [1].

- Linking Structure to Function: This approach allows researchers to link specific structural features (e.g., cluster density, honeycomb patterns) to functional heterogeneity, visualizing how the biofilm architecture supports the formation of metabolic gradients [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AFM for Nanomechanical Profiling of Biofilms under Physiological Conditions

This protocol describes the procedure for preparing and analyzing biofilms to quantify the mechanical properties of the EPS matrix and individual cells, including persisters.

I. Sample Preparation

- Substrate Selection: Use PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or relevant medical polymer surfaces (e.g., polyethylene, polyurethane) to facilitate bacterial attachment [1] [3].

- Biofilm Growth: Inoculate the substrate with the bacterial strain of interest (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343, E. coli) in an appropriate growth medium. Incubate for a defined period (e.g., 30 minutes for early attachment studies; 6-48 hours for mature biofilms) under optimal conditions [1].

- Sample Rinsing and Hydration: Gently rinse the sample with a sterile physiological buffer (e.g., PBS, 10mM HEPES) to remove non-adherent cells. Critical: Do not let the sample dry. Immediately mount the sample in the AFM liquid cell, ensuring it remains fully hydrated in the chosen buffer to maintain physiological conditions [1].

II. AFM Imaging and Force Spectroscopy

- Probe Selection: Use sharp silicon nitride tips (nominal spring constant ~0.1 N/m) for high-resolution imaging in soft tapping mode. For force spectroscopy, use tips with a well-defined geometry (e.g., spherical tips) and calibrate their spring constant prior to measurement.

- Data Acquisition:

- Topographical Imaging: Acquire images in tapping mode in fluid to minimize sample damage. For large-area analysis, employ an automated rastering and stitching algorithm [1].

- Force Volume Mapping: Acquire a grid of force-distance curves over the region of interest (e.g., on the EPS matrix, on a single cell, and on a dormant-looking cell). Collect a minimum of 32x32 curves per map.

- Single-Cell Mechanics: Position the AFM tip over the center of a selected cell and acquire multiple force-distance curves to ensure data reproducibility.

III. Data Analysis

- Topographical Analysis: Use machine learning-based segmentation to automatically identify and count cells, and calculate parameters like surface coverage (confluency) and roughness [1].

- Elasticity Calculation: Fit the retraction portion of the force-distance curves to the Hertzian contact model (for spherical tips) to derive the Young's modulus (Elasticity) for each point of measurement.

- Adhesion Force: Extract the maximum adhesion force from the force-distance curve's retraction signature.

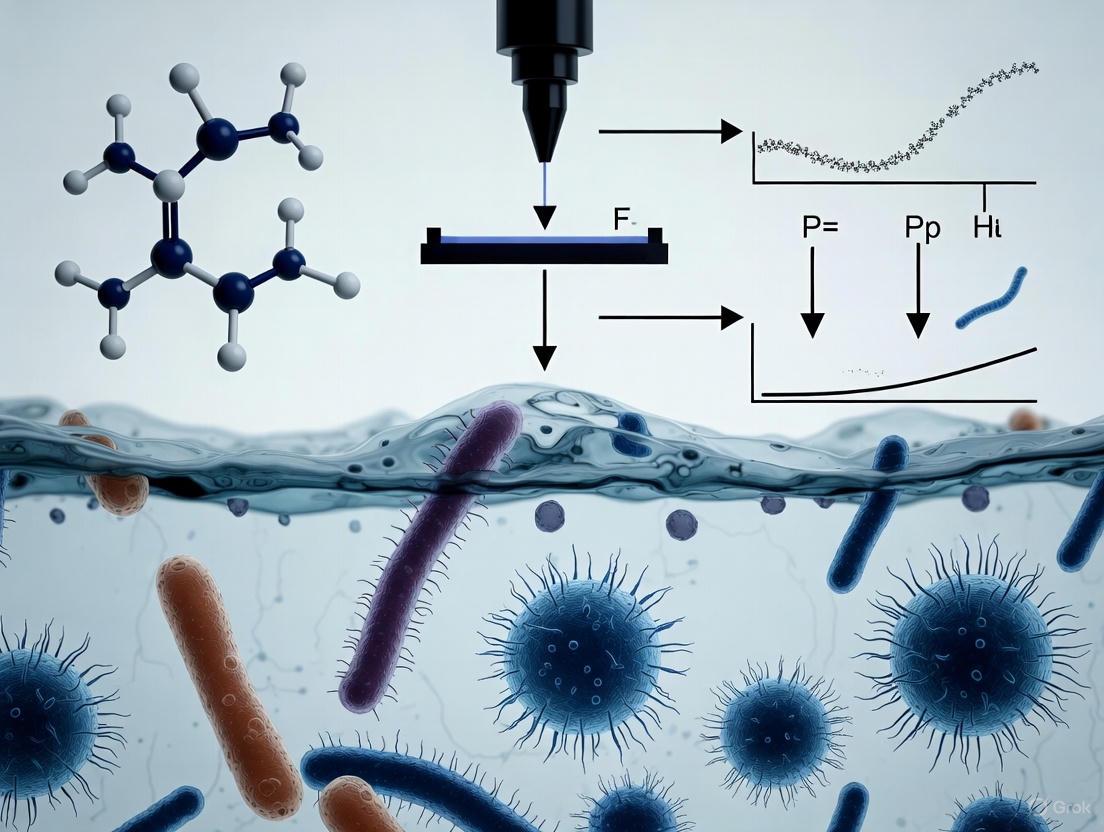

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps of this protocol:

Protocol 2: Correlative Analysis of Persister Cells

This protocol outlines a method for isolating and physically characterizing persister cells following antibiotic treatment.

I. Persister Cell Isolation

- Culture and Treatment: Grow the bacterial strain to mid-log phase. Treat the culture with a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., 20x MIC of ampicillin) for an extended period (e.g., 25 hours) [2].

- Confirmation of Persistence: Determine the survival rate via colony-forming unit (CFU) counts. A biphasic kill curve with a surviving subpopulation confirms persister formation [2] [4].

- Washing: Gently wash the antibiotic-treated culture to remove the drug and debris, resuspending the pellet in a suitable physiological buffer.

II. Correlative Microscopy and AFM

- Fluorescence Staining: Use a LIVE/DEAD viability stain (e.g., SYTO 9 and propidium iodide). Persisters will be stained as live (green) despite antibiotic exposure.

- Identification and Correlation: Use fluorescence microscopy to locate clusters of viable cells. Correlate this location with the AFM stage for subsequent nanomechanical analysis [4].

- AFM Characterization: Follow the AFM procedures in Protocol 1 to perform force spectroscopy on the identified persister cells and non-persister cells for comparative analysis of their mechanical properties (refer to Table 1).

Signaling Pathways in Biofilm Resistance

A key signaling molecule governing the transition from planktonic life to the biofilm state and the emergence of persistence is cyclic di-guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP). High intracellular levels of c-di-GMP promote biofilm formation by upregulating the production of EPS matrix components and adhesins. Furthermore, the c-di-GMP network interacts with cellular stress response pathways that can induce a dormant, persistent state. Recent studies on natural compounds like flavonoids (e.g., fisetin) have shown that they can target and inhibit diguanylate cyclases (DGCs), the enzymes that synthesize c-di-GMP, thereby disrupting biofilm formation and its associated resistance [5]. The following diagram illustrates this central pathway and a potential intervention point.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for AFM-Based Biofilm Resistance Research

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Substrates | To control initial bacterial attachment and study surface-biofilm interactions. | PFOTS-treated glass; Medical-grade polyethylene/polyurethane [1] [3]. |

| Physiological Buffers | To maintain native conditions for AFM imaging and force spectroscopy in liquid. | 10mM HEPES (pH 7.4); Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) [1]. |

| AFM Probes | For high-resolution imaging and nanomechanical property quantification. | Sharp silicon nitride tips for imaging; spherical colloidal probes for force spectroscopy. |

| Viability Stains | To correlate cell viability (e.g., persisters) with nanomechanical properties. | LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kits (SYTO 9/PI) [4]. |

| c-di-GMP Pathway Modulators | To experimentally manipulate biofilm formation and dissect resistance mechanisms. | Fisetin, a flavonoid that inhibits diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) [5]. |

| Machine Learning Software | For automated analysis of large-area AFM data (cell detection, classification, stitching). | Custom algorithms for image segmentation and feature extraction [1]. |

Biofilms are structured communities of bacterial cells enclosed in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix that pose a significant challenge in medical, industrial, and environmental contexts due to their remarkable resistance to antimicrobial agents [6]. Understanding biofilm assembly, structure, and function is paramount for developing effective control strategies across healthcare sectors, yet researchers face significant methodological limitations when relying on classical characterization techniques. While methods such as crystal violet staining, colony forming unit (CFU) counts, and static electron microscopy have formed the historical backbone of biofilm analysis, they present critical constraints in resolution, quantification, and physiological relevance that hinder comprehensive understanding [7] [8]. These limitations become particularly problematic when investigating the dynamic, three-dimensional architecture of biofilms under conditions that mimic their natural environments. The advent of atomic force microscopy (AFM) operated in fluid under physiological conditions represents a transformative approach that bypasses these constraints, enabling nanoscale investigation of biofilm formation, structure, and response to therapeutic interventions with minimal sample disturbance [1] [9]. This application note delineates the specific limitations of classical biofilm assessment methods and illustrates how fluid-phase AFM addresses these challenges while providing detailed protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Limitations of Classical Biofilm Assessment Methods

Classical methods for biofilm quantification provide limited and often misleading information about biofilm viability, composition, and structure. The crystal violet assay, while cost-effective and compatible with high-throughput screening, measures total biomass without distinguishing between viable cells, dead cells, and the extracellular matrix components [6]. This limitation becomes particularly problematic when assessing antimicrobial efficacy, as demonstrated in studies where polysaccharide-degrading enzymes caused apparent increases in crystal violet staining despite actual biofilm disruption—a false positive resulting from increased availability of dye-binding sites [7]. Similarly, CFU enumeration, which quantifies viable and culturable bacteria, fails to account for the metabolically dormant "persister" cells within biofilms that remain viable but non-culturable under standard laboratory conditions [6]. This methodological gap can lead to significant underestimation of biofilm survival after antimicrobial treatment. The static nature of these measurements also obscures the dynamic processes central to biofilm development and resilience.

Table 1: Limitations of Classical Biofilm Quantification Methods

| Method | Primary Measurement | Key Limitations | Impact on Data Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Violet Staining | Total biomass (cells + EPS) [6] | Cannot distinguish live/dead cells; EPS degradation may falsely increase signal [7] | Overestimation of biofilm viability after treatment; false positives |

| CFU Enumeration | Viable, culturable bacteria [8] [6] | Misses viable but non-culturable cells; requires biofilm disruption; sampling variability [6] | Underestimation of true viable cell count; incomplete efficacy assessment |

| Congo Red Agar | Extracellular polysaccharide production [6] | Semi-quantitative; media-dependent; no viability or structural data [6] | Qualitative assessment only; limited application for therapeutic screening |

Structural and Dynamic Analysis Constraints of Static Imaging

Static imaging techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and conventional light microscopy, fail to capture the dynamic structural changes and functional adaptations of living biofilms. SEM provides high-resolution surface images of biofilms but requires extensive sample preparation involving fixation, dehydration, and conductive coating—processes that introduce artifacts and distort the native biofilm architecture [10] [6]. While valuable for examining surface details, these methods eliminate the possibility of observing real-time biofilm development or response to environmental stimuli. Light microscopy techniques, including standard fluorescence microscopy, offer live imaging capabilities but suffer from limited resolution and penetration depth, making them unsuitable for analyzing the three-dimensional complexity of mature biofilms [6]. This resolution gap becomes particularly critical when investigating finer biofilm features such as initial attachment mechanisms, flagellar interactions, and EPS matrix organization, which occur at the nanoscale [1]. The following table compares the capabilities and constraints of various biofilm imaging modalities:

Table 2: Comparison of Biofilm Imaging Techniques

| Technique | Resolution | Sample Preparation | Live Imaging Capability | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light Microscopy | ~200 nm [6] | Minimal (for live cells) [8] | Yes [8] | Limited resolution; poor penetration in thick biofilms [6] |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | <10 nm [10] | Extensive (fixation, dehydration, coating) [10] [6] | No | Artifacts from preparation; no physiological conditions [10] |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) | ~200 nm [10] | Fluorescent staining often required [10] | Yes | Limited by dye penetration; photobleaching; lower resolution than AFM [1] |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) in Fluid | <5 nm [1] [9] | Minimal (can image in physiological buffer) [1] [9] | Yes | Limited scan area in conventional systems; specialized equipment required [1] |

Advanced Protocols: Atomic Force Microscopy in Physiological Conditions

Atomic force microscopy operated in fluid under physiological conditions addresses the fundamental limitations of classical techniques by enabling nanoscale resolution imaging of biofilms in their native, hydrated state. This methodology preserves the delicate structures of both bacterial cells and the surrounding EPS matrix while allowing for real-time observation of dynamic processes. The following section provides detailed protocols for assessing biofilms using AFM in physiological conditions, with particular emphasis on the novel large-area AFM approach and force spectroscopy measurements that directly quantify biofilm adhesion properties—capabilities absent in classical methods.

Protocol: Large-Area AFM Imaging of Biofilm Formation Under Physiological Conditions

The limited scan range of conventional AFM (<100 µm) has historically restricted its ability to link nanoscale features to the functional macroscale organization of biofilms [1]. The recently developed automated large-area AFM approach overcomes this constraint by capturing high-resolution images over millimeter-scale areas, providing unprecedented insights into spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology during biofilm development [1].

Experimental Workflow:

Materials and Reagents:

- Bacterial Strains: Pantoea sp. YR343 (gram-negative, motile, biofilm-forming) or relevant clinical isolates [1]

- Growth Medium: Appropriate nutrient broth (e.g., Tryptic Soy Broth for Pantoea sp.) [1]

- Substrates: PFOTS-treated glass coverslips or silicon substrates (for controlled hydrophobicity) [1]

- Imaging Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) or specific growth medium without indicators [1] [9]

- AFM System: Atomic force microscope with large-area piezo scanner, liquid cell, and appropriate cantilevers (e.g., MikroMasch HQ:NSC14/Al BS) [1] [11]

Procedure:

- Biofilm Growth: Inoculate petri dishes containing sterile substrate coverslips with bacterial culture diluted to appropriate density (e.g., 0.5 McFarland standard). Incubate at optimal growth temperature for selected time points (e.g., 30 minutes for initial attachment studies, 6-8 hours for microcolony formation) [1].

- Sample Preparation: Gently remove coverslips from growth medium and rinse with imaging buffer to remove non-adherent cells while preserving the native biofilm structure. Avoid dehydration or fixation steps that would alter biofilm morphology.

- AFM Mounting: Secure the prepared sample in the AFM liquid cell and add appropriate imaging buffer to completely submerge the biofilm. Ensure no air bubbles are trapped between the cantilever and sample surface.

- Imaging Parameters: Engage the cantilever in fluid tapping mode to minimize lateral forces. Set appropriate scan parameters (typically 1-2 Hz scan rate, 512-1024 points per line). Implement automated large-area scanning through predefined tile patterns with minimal overlap (5-10%) [1].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire sequential images across the millimeter-scale area. Maintain temperature control if studying temperature-dependent phenomena.

- Image Processing: Use machine learning-assisted stitching algorithms to seamlessly combine individual image tiles into a comprehensive large-area map [1]. Implement automated segmentation and classification to identify cellular features, orientation, and spatial distribution patterns.

Key Applications:

- Visualization of preferred cellular orientation and honeycomb patterning in early biofilm formation [1]

- Mapping of flagellar interactions and their role in surface attachment and cellular coordination [1]

- Correlation of nanoscale surface properties with spatial heterogeneity in bacterial adhesion [1] [11]

Protocol: Quantitative Adhesion Force Measurements Using FluidFM Technology

Traditional single-cell force spectroscopy provides limited representation of realistic biofilm conditions where bacteria exist in communities encased in EPS [9]. FluidFM technology combines AFM with microfluidics to directly measure adhesion forces between entire biofilms and surfaces, offering more clinically relevant data for anti-biofouling therapeutic development.

Experimental Workflow:

Materials and Reagents:

- FluidFM System: Atomic force microscope with FluidFM capability, microfluidic cantilevers with apertures (8-12 µm), and pressure controller [9]

- Biofilm Carriers: COOH-functionalized polystyrene beads (10-15 µm diameter) optimized for bacterial growth [9]

- Bacterial Strains: Relevant biofilm-forming strains (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa for medical applications) [9]

- Surface Modifications: Vanillin-coated polyethersulfone membranes or other anti-biofouling surfaces for therapeutic testing [9]

- Measurement Buffer: Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or specific physiological fluid relevant to application [9]

Procedure:

- Biofilm Growth on Beads: Incubate COOH-functionalized polystyrene beads with bacterial suspension in growth medium for 3 hours to establish initial biofilms. Use controlled shaking to ensure even biofilm development on bead surfaces [9].

- Cantilever Preparation: Clean microfluidic cantilevers according to manufacturer specifications. Fill cantilever and tubing with appropriate measurement buffer, ensuring no air bubbles remain in the system.

- Bead Aspiration: Apply negative pressure through the FluidFM system to aspirate a single biofilm-coated bead onto the cantilever aperture. Verify secure attachment through optical microscopy.

- Force Spectroscopy Measurements: Approach the biofilm-bearing cantilever to the test surface at a controlled rate (typically 0.5-1 µm/s). Upon contact, apply a defined contact force (0.5-2 nN) for a set dwell time (0.5-2 seconds) to simulate attachment conditions. Retract the cantilever at the same rate while recording the force-distance curve.

- Data Collection: Collect a minimum of 50-100 force curves across different locations on each surface type to ensure statistical significance. Include control measurements with unmodified surfaces for baseline comparison.

- Analysis Parameters: Quantify maximum adhesion force, adhesion work (area under the retraction curve), and the number of adhesion events from each force curve. Compare results between modified and control surfaces to evaluate anti-biofouling efficacy.

Key Applications:

- Direct quantification of biofilm adhesion reduction by anti-biofouling surface modifications (e.g., vanillin-coated membranes showed significant adhesion force reduction) [9]

- Comparison of biofilm vs. single-cell adhesion behavior, highlighting the contribution of EPS matrix to attachment strength [9]

- Evaluation of therapeutic candidates for their ability to disrupt biofilm-surface interactions under physiologically relevant conditions [9]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing advanced AFM-based biofilm characterization methods, with specific emphasis on maintaining physiological conditions throughout analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AFM Biofilm Studies Under Physiological Conditions

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-Treated Glass Substrates | Controlled hydrophobicity for studying attachment dynamics [1] | Enables investigation of surface property effects on initial bacterial adhesion |

| COOH-Functionalized Polystyrene Beads | Biofilm carriers for FluidFM adhesion measurements [9] | Optimal for bacterial growth and biofilm formation; compatible with microfluidic aspiration |

| Physiological Buffers (PBS, etc.) | Maintain hydrated, native state during AFM imaging [1] [9] | Preserves biofilm structure and function; prevents dehydration artifacts |

| Specialized AFM Cantilevers | Nanoscale force sensing and imaging in liquid [1] [11] | Silicon tips with pyramidal geometry; appropriate spring constants (0.1-0.5 N/m) for biofilms |

| Vanillin Coating Solutions | Anti-biofouling surface modification for therapeutic testing [9] | 3 g/L in PBS; quorum sensing inhibitor that reduces EPS production |

Classical biofilm assessment techniques including crystal violet staining, CFU enumeration, and static imaging methods present fundamental limitations in resolution, quantification accuracy, and physiological relevance that constrain research progress and therapeutic development. Atomic force microscopy operated in fluid under physiological conditions directly addresses these constraints by enabling nanoscale resolution imaging of hydrated, living biofilms without requiring destructive sample preparation. The protocols detailed herein for large-area AFM imaging and quantitative adhesion force measurements provide researchers with robust methodologies to investigate biofilm structure, dynamics, and therapeutic responses under conditions that closely mimic native environments. By adopting these advanced AFM approaches, researchers and drug development professionals can overcome the critical gaps inherent in classical techniques and accelerate the development of effective anti-biofilm strategies.

In biofilm research, the environmental context is not merely a background variable but a fundamental determinant of microbial structure and function. Biofilms, defined as assemblages of microbial cells irreversibly associated with a surface and enclosed in a matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), develop phenotypes that are critically distinct from their free-floating, planktonic counterparts [12] [13]. These phenotypic shifts are not intrinsic properties of the microbes alone; they are emergent traits dictated by the complex interplay between the microbial community and its surrounding fluid environment. Studying biofilms outside their physiological, fluid contexts—such as in dried or air-imaged states—fails to capture the true nature of their architecture, mechanics, and resistance profiles.

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) operated in fluid under physiological conditions presents a powerful solution to this challenge. It allows for the high-resolution investigation of biofilms in a state that closely mimics their natural and clinical habitats [1] [14]. This application note details the rationale, protocols, and key applications for employing AFM in fluid to elucidate how fluid environments dictate biofilm structure and function, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for physiologically relevant analysis.

Key Concepts: Biofilm Properties Shaped by Fluid Environments

The formation of a biofilm is a developmental process initiated by the attachment of planktonic cells to a surface, a process heavily influenced by the properties of the aqueous medium, substratum effects, and hydrodynamic conditions [12]. An established biofilm is a hydrogel, a complex three-dimensional ecosystem characterized by gradients of nutrients, oxygen, and metabolic waste products [15] [13]. These gradients, established and maintained within the fluid milieu, lead to heterogeneous zones of cellular activity and are a primary reason for the increased tolerance of biofilms to antimicrobial agents [15].

The following table summarizes core biofilm properties that are directly shaped by their fluid environment and can be probed by AFM.

Table 1: Biofilm Properties Dictated by the Fluid Environment

| Property | Description | Impact of Physiological Fluid Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| EPS Matrix Structure | A hydrated network of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and DNA that forms the biofilm scaffold [13]. | Hydration state dictates matrix viscoelasticity, porosity, and stability. Dehydration for imaging collapses this native structure [14]. |

| Cellular Phenotype | The physiological state of cells within the biofilm differs from planktonic cells due to differential gene regulation [12]. | Fluid conditions maintain the phenotypic state, including the presence of persister cells, which contribute to antibiotic tolerance [15]. |

| Mechanical Stability | The viscoelastic behavior of the biofilm, which confers resistance to physical shear forces [14]. | Mechanical properties like elasticity and viscosity are intrinsic to the hydrated state. Measurements in air are not physiologically relevant. |

| Nutrient & Signaling Gradients | The differential distribution of molecules from the biofilm exterior to interior, creating heterogeneous microenvironments [15]. | Fluid flow is essential for establishing and maintaining these gradients, which influence metabolic activity and cellular differentiation. |

| Adhesion Strength | The force with which the biofilm adheres to a substratum or constituent cells cohere to each other [14]. | Adhesive forces are mediated by the hydrated EPS and are sensitive to ionic strength and pH of the surrounding fluid [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for AFM in Fluid

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation for AFM Analysis of Biofilms in Liquid

Objective: To grow and prepare biofilm samples for AFM analysis while preserving their native structure under physiological fluid conditions.

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343 [1] or Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 [14].

- Growth Medium: Appropriate sterile broth (e.g., Trypticase Soy Broth for P. aeruginosa [14]).

- Substrata: PFOTS-treated glass coverslips [1], pristine glass, or other relevant surfaces (e.g., silicone-based materials).

- AFM Liquid Cell: A sealed fluid cell compatible with the AFM instrument.

Methodology:

- Surface Conditioning (Optional): If studying attachment on conditioned surfaces, expose the sterile substratum to the relevant fluid (e.g., simulated sputum medium SCFM2 for cystic fibrosis models [16]) for a defined period to form a conditioning film [12].

- Biofilm Growth: Inoculate a petri dish containing the chosen substratum with a bacterial suspension in growth medium. For early attachment studies, use a brief incubation period (~30 minutes to 2 hours). For mature biofilms, incubate for 6-24 hours or longer [1].

- Sample Mounting: Carefully remove the substratum with the attached biofilm from the growth medium.

- Gentle Rinsing: Immerse the sample gently in a buffered solution (e.g., PBS or a defined minimal medium) to remove non-adherent planktonic cells. Critical Step: Avoid dehydration or air-drying.

- AFM Fluid Cell Assembly: Place the hydrated sample onto the AFM sample stage. Assemble the liquid cell and fill it with the appropriate buffered solution to fully submerge the biofilm during imaging and force spectroscopy.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Adhesion and Viscoelasticity Measurements via MBFS

Objective: To absolutely quantify the adhesive and viscoelastic properties of a bacterial biofilm under native conditions using Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) [14].

Materials:

- AFM Instrument: MFP-3D or equivalent closed-loop AFM system.

- AFM Probes: Rectangular tipless silicon cantilevers (e.g., Mikromasch CSC12/Tipless).

- Microbeads: 50 µm diameter glass beads.

- Calibration Materials: Required for the thermal tuning method of cantilever spring constant calibration.

Methodology:

- Probe Functionalization: Attach a sterile 50 µm glass bead to the end of a tipless cantilever using a suitable epoxy.

- Biofilm-Coated Probe: Incubate the bead-probe in a concentrated suspension of the bacterial strain (e.g., OD600 of 2.0 for P. aeruginosa) to coat it with a layer of biofilm cells.

- System Calibration: Calibrate the cantilever's spring constant using the thermal tuning method [14].

- Standardized Force Measurements:

- Approach: Bring the biofilm-coated bead into contact with a clean glass surface in the liquid cell.

- Contact: Apply a predefined loading force (e.g., 500 pN) and maintain contact for a set "hold" time (e.g., 1-2 seconds).

- Retraction: Retract the probe at a constant speed while recording the force vs. distance curve.

- Data Analysis:

- Adhesion Pressure: Calculate from the maximum adhesive force during retraction, divided by the contact area between the bead and surface [14].

- Viscoelastic Parameters: Fit the indentation-versus-time data from the "hold" period to a viscoelastic model (e.g., the Voigt Standard Linear Solid model) to extract parameters such as the instantaneous elastic modulus (E₀), delayed elastic modulus (E₁), and viscosity (η) [14].

Table 2: Standardized MBFS Conditions for Reproducible Quantitation

| Parameter | Standardized Condition | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Loading Force | 500 pN | Ensures sufficient contact without damaging cells. |

| Contact Time | 1-2 seconds | Allows for molecular rearrangements and bond formation. |

| Retraction Speed | 1 µm/s | Balances measurement stability and detection of short-lived interactions. |

| Liquid Environment | Buffered Solution (e.g., PBS) | Maintains physiological ionic strength and pH. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for AFM-based Biofilm Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS-Treated Glass | Hydrophobic substratum for studying initial bacterial attachment [1]. | Alters surface energy, promoting specific attachment patterns. |

| Synthetic Cystic Fibrosis Sputum Medium (SCFM2) | Physiologically relevant growth medium for clinical isolate studies [16]. | Induces formation of suspended aggregates with high mechanical resilience. |

| Tipless AFM Cantilevers | Base probes for functionalization with microbeads or cells for force spectroscopy [14]. | Enables customized probe geometry for quantifiable contact areas. |

| Glass Microbeads (50 µm) | Spherical probes for Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) [14]. | Provides a defined contact area for absolute quantitation of adhesion pressure. |

| Closed-Loop AFM System | Instrumentation for accurate force and position measurement without drift [14]. | Critical for reliable long-term experiments and precise indentation measurements. |

Data Presentation & Analysis

AFM in fluid generates rich, quantitative data on the structural and mechanical properties of biofilms. The following table compiles key findings from recent studies, highlighting the quantitative differences observable under physiologically relevant conditions.

Table 4: Quantitative AFM Data on Biofilm Properties under Physiological Conditions

| Biofilm System | Measured Property | Quantitative Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Early Biofilm) | Adhesive Pressure [14] | 34 ± 15 Pa | Provides a baseline for the strength of initial surface attachment. |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Mature Biofilm) | Adhesive Pressure [14] | 19 ± 7 Pa | Suggests adhesive properties evolve during biofilm maturation. |

| P. aeruginosa wapR Mutant (Early Biofilm) | Adhesive Pressure [14] | 332 ± 47 Pa | Demonstrates that genetic alterations (LPS deficiency) drastically increase adhesion. |

| P. aeruginosa wapR Mutant (Mature Biofilm) | Adhesive Pressure [14] | 80 ± 22 Pa | Highlights that genetic background and maturation stage interact to determine physical properties. |

| P. aeruginosa Aggregates in SCFM2 | Mechanical Resilience | Increased resistance to deformation vs. planktonic cells [16]. | Shows that environmental cues alone can enhance mechanical robustness, independent of mature matrix. |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | Cellular Dimensions | ~2 µm length, ~1 µm diameter [1] | High-resolution AFM allows for precise morphological characterization of surface-attached cells. |

| Pantoea sp. YR343 | Flagellar Dimensions | ~20-50 nm height [1] | Visualizes subcellular structures critical for attachment and motility, which are obscured in non-fluid imaging. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Experimental AFM Workflow for Biofilm Analysis

Diagram 2: How Fluid Environments Dictate Biofilm Phenotype

Atomic Force Microscopy of Biofilms—Imaging, Interactions, and Mechanics

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has proven itself to be a powerful and diverse tool for the study of microbial systems on both single and multicellular scales, including complex biofilms [17]. This chapter will review how AFM and its derivatives have been used to unravel the nanoscale forces governing the structure and behavior of biofilms, thus providing unique insight into the control of microbial populations within clinical and industrial environments [17]. Diversification of AFM-based technologies has allowed for the creation of a truly multiparametric platform, enabling the interrogation of all aspects of microbial systems [17]. Advances in traditional AFM operation have allowed, for the first time, insight into the topographical landscape of both microbial cells and spores, which, when combined with high-speed AFM's ability to resolve the structure of surface macromolecules, have provided, with unparalleled detail, visualization of this complex environmental interface [17]. The application of AFM force spectroscopies has enabled the analysis of many microbial nanomechanical properties including macromolecule folding pathways, receptor ligand binding events, microbial adhesion forces, biofilm mechanical properties, and antimicrobial/antibiofilm affectivities [17]. Thus, AFM has offered an outstanding glimpse into the biofilm, how its inhabitants create and use this complex adaptive interface, and perhaps most importantly what can be done to control this [17].

Biofilms remain a primary concern in industrial and clinical fields [17]. The tendency of planktonic cells to form these structures in moist environments and the resulting increase in resistance to antimicrobials, in combination with an increasing frequency of innate antimicrobial resistance, demonstrates the continued need for novel biofilm control strategies and innovative methods to unravel the fundamental properties of biofilms [17]. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has proven to be a useful addition to the microscopy family providing imaging and force measurement capabilities that can interrogate the nanoscale properties of surfaces [17]. Indeed, AFM has been used with great success to provide novel insight into the structure of biofilms and the interplay of interaction forces and mechanical properties that govern the behavior of biofilms and their response to chemical and physical attack as part of control strategies [17]. AFM can be used to study whole biofilms or the influence of their component parts, from bacterial surface proteins to extracellular polysaccharides (EPSs) and individual cells [17].

AFM Basic Principles

AFM was first developed as part of the family of scanning probe microscopies in 1986 [17]. It was very quickly applied to the imaging of biological materials, including DNA, bacteria, viruses, and mammalian cells [17]. The components of an atomic force microscope are shown in Figure 1. A very small, sharp tip held at the free end of a cantilever systematically scans a surface of interest to generate a topographical image [17]. The tip is held in intimate contact with the surface, and its apex has a radius of curvature in the range of nanometers, which sets the image resolution [17]. As the tip is systematically scanned across the surface, it encounters surface forces that cause the cantilever to be deflected [17]. The deflection of the cantilever is monitored by the displacement of a reflected laser beam and used to create a topographical image [17]. In contact mode, the forces of the bent cantilever keep the tip in intimate contact with the surface [17].

When imaging a soft sample such as a bacterial cell surface or biofilm, the tapping mode or intermittent contact mode is used [17]. The intermittent contact of this imaging mode reduces the degree of friction or drag on a sample compared with imaging in contact mode [17]. To achieve the intermittent contact, a vibrating cantilever technique is used, and the changes in the vibrational parameters are monitored as the cantilever scans the surface [17]. In response to changes in topography, the piezo-scanner moves up and down to maintain a constant vibration of the cantilever, and the feedback signal is used to produce the image data set [17]. A further advantage of this imaging mode is that measurement of the phase angle between the free oscillation at the end of the cantilever and the imposed driving vibration provides a map of phase angle across a surface; this data, referred to as phase imaging, is captured simultaneously as the standard topographical data [17]. This phase angle is often used to qualitatively distinguish between materials on the surfaces of heterogeneous samples as the phase angle change is a function of the mechanical properties of the surface and the area of contact between the AFM tip and the surface [17].

The advantages of tapping mode have meant that this is the most frequently used method when imaging soft biological samples [17]. The authors have found tapping mode in combination with phase imaging extremely useful in identifying structures on the cells and within biofilm [17]. Figure 2 presents AFM tapping mode images of a range of microbial biofilms [17]. When imaging biofilms, the mechanical robustness of a biofilm should be considered; it is simpler to image model biofilms with minimum components, which have been grown on adhesion-promoting substrates, compared to biofilms that have been sampled from natural or industrial settings that consist of multiple components [17]. As AFM imaging is a technique that relies on surface contact, the imaging of a hydrated diffuse biofilm is very difficult without fixation methods [17].

The AFM can measure the forces of interactions between surfaces, which have obvious implications in the study of biofilms [17]. AFM has been added to the group of instruments that can be used to study microbial interactions involved in biofilm formation [17]. Such instruments include flow chambers, micropipette aspiration, and centrifugation devices [17]. However, AFM has the advantage of allowing the imaging and identification of points of interest on a surface prior to the measurement of the forces of interaction [17]. AFM also allows the direct measurement of forces as opposed to techniques that estimate force from the application of shear to a cell population [17]. In addition, surface forces are measured over very small contact areas, minimizing contamination problems [17]. To generate a force–distance curve, the deflection of the cantilever is recorded as a function of tip‐to‐sample separation, as the piezo‐scanner of the AFM brings the sample and tip together [17]. The deflection of the cantilever is converted to a value of force using Hooke's law [17]. Force–distance curves are characteristic of the system under study [17]. For biofilms, they have features that reflect the chemical and physical properties of the surfaces that are interacting, including the substrate, the cells, EPS, and the AFM probe [17]. Figure 3 shows a typical force measurement between an AFM cell probe (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and a biofilm surface [17].

Operating the AFM as a nanoindenter allows the measurement of microbial cell and biofilm mechanical properties, which include elastic moduli and turgor pressure [17]. Figure 4 shows how the indentation depth is measured by comparison between force curves measured at a reference hard surface and at the softer sample surface [17]. The indentation depth can then be plotted as a function of applied force and compared with a theoretical framework to quantify sample mechanical properties [17]. The most commonly used theoretical framework is based on the Hertz model, which describes the elastic deformation of two perfectly homogeneous smooth bodies touching under load [17]. The geometry of the system is assumed to consist of an indenter with a parabolic shape and a sample that is of much greater thickness than the indentation depth [17]. The Hertz model that describes force on the cantilever ( F ) as a function of indentation ( \delta ) is given by [17]:

[ F = \frac{4}{3} \frac{E}{1 - \nu^2} \sqrt{R} \delta^{3/2} ]

where the tip is approximated with the radius ( R ), and ( E ) and ( \nu ) are the elastic modulus and Poisson's ratio of the sample, respectively [17].

Imaging

Examination of microbial systems in native, aqueous environments is central to the validity of the data collected [17]. However, AFM imaging in such environments is often difficult due to a number of factors [17]. For instance, microbial cells are often attached to the surface via week Lifshitz‐Van der Waals forces, and as a result are easily disrupted by the scanning of an AFM cantilever, resulting in the destruction of the sample [17]. Additionally, microbial cells are often motile with some recent papers suggesting that motility may even be the largest governing factor in the physiological imaging of microbes [17]. Consequently, immobilization of microbial cells prior to analysis has become imperative to the application of AFM in the imaging of microbial systems [17].

Cell Immobilization for Single‐Cell Analysis

Immobilization of microbial cells has often proven to be the most problematic step in the imaging of microbial samples under aqueous conditions [17]. The immobilization must be secure enough to withstand the lateral forces exerted by the tip during scanning, but benign enough to not force physiochemical, physiological, or nanomechanical changes in the sample [17]. As a result, a number of different techniques have arisen; these protocols can be broadly divided into two categories: mechanical, whereby microbial cells are physically trapped within a porous media, and chemical, whereby chemical treatment of the substrate is used to facilitate binding [17].

Initial studies into the use of mechanical protocols to immobilize microbes utilized agar or membranes with pore diameters similar to the cell diameter of the organism to be captured [17]. Later work expanded upon this through the use of more complex or functionalized surfaces such as lithographically patterned silica [17]. Though, while mechanical entrapment offers immobilization secure enough to alleviate the destructive scanning of the cantilever, the immobilization is sporadic and unpredictable, reducing the reproducibility of the results [17]. Recent work by Formosa et al. developed a protocol in which selective tuning of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps were used to immobilize spherical microorganisms of various sizes [17]. The protocol requires the creation of a glass and chromium blank that holds the microstructure, from which the pattern is transferred to a silicon wafer by deep reactive ion etching [17]. The dimensions of the silicon master can be varied with the group reporting dimensions of 1.5–6 µm wide, a pitch of 0.5 µm, and a depth of 1–4 µm, accommodating a variety of target cell sizes [17]. A PDMS stamp is then cast from the silicon wafer master and cells deposited through the use of convective and capillary forces [17]. Further work by the group has shown this immobilization technique to be an effective way to immobilize spherical cells, in this case Staphylococcus aureus, for AFM analysis [17].

A number of chemical fixation methods for the immobilization of microbial cells have been used, including, poly‐l‐lysine, trimethoxysilyl‐propyl‐diethylenetriamine, mica, and carboxyl [17].

Advanced AFM Techniques for Biofilm Research

Large Area Automated AFM

While AFM provides detailed structural and mechanical insights in biology and cell research, its impact on biofilm research has been surprisingly limited [1]. Conventional image analysis methods allow for the measurement of individual cell dimensions, but automated techniques are crucial for efficiently characterizing bacterial biofilms, which can contain up to 1012 cells per gram [1]. AFM's small imaging area (<100 µm), restricted by piezoelectric actuator constraints, limits its capacity to study large, millimeter-scale biofilm structures [1]. This scale mismatch makes it difficult to capture the full spatial complexity of biofilms and raises questions about the representativeness of the collected data [1]. Furthermore, the slow scanning process and labor-intensive operation require specialized operators, hindering the capture of dynamic structural changes over extended time and length scales [1]. Developing automated large-area AFM methods and integrating AFM with other multimodal techniques will significantly advance biofilm research by enabling comprehensive analysis of these complex microbial communities [1].

Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are transforming AFM by enhancing data acquisition, control, and analysis [1]. ML applications in AFM fall into four key areas: sample region selection, scanning process optimization, data analysis, and virtual AFM simulation [1]. AI-driven models optimize scanning site selection, reducing human intervention and accelerating acquisition [1]. ML can be further used to improve scanning by refining tip–sample interactions, correcting distortions, reducing the time by sparse scanning approaches, and automating probe conditioning for more precise imaging [1]. AI frameworks have also enabled autonomous operation of scanning AFM and direct control of through large language models, not by replacing human operators but by automating routine tasks, optimizing decision-making processes, and enhancing scientific discovery through human–ML collaboration and enabling allowing continuous even multiday experiments without human supervision [1]. In data analysis of AFM, ML, and AL tools are enabling automated segmentation, classification, and defect detection in AFM images, aiding in cancer cell identification and molecular structure prediction [1]. These advancements significantly enhance AFM's efficiency, accuracy, and automation, particularly in biological research and nanomaterials characterization [1].

In this work, we address the challenges of biofilm imaging by AFM through the development of an automated large-area AFM which is capable of analyzing microbial communities over extended surface areas with minimal user intervention [1]. By automating the scanning process, we overcome many limitations of traditional AFMs, including small imaging areas, and enable imaging of the inherent millimeter-sized communities [1]. We evaluate image stitching algorithms for performance with minimal matching features between images [1]. Limited overlap between scans maximizes acquisition speed, producing seamless, high-resolution images that capture the spatial complexity of surface attachment [1]. To manage the high-volume, information-rich data, we implement machine learning-based image segmentation and analysis methods [1]. These tools assist in automating the extraction of important parameters, such as cell count, confluency, cell shape, and orientation, and facilitate efficient and quantitative analysis of microbial community characteristics over extensive areas [1]. We demonstrate the applicability and effectiveness of our methods by imaging the initial surface attachment of Pantoea sp. YR343 [1]. Additionally, we apply large-area AFM to gradient-structured surfaces, allowing us to study how varying surface properties influence attachment dynamics and community structure in a combinatorial approach [1]. By integrating these advancements, our work enhances the capabilities of AFM for biofilm research, enabling comprehensive structural and mechanical characterization of biofilms at scales relevant to their natural environments [1].

High-Resolution AFM Imaging of Microbial Systems

In a study focusing on Pantoea sp. YR343, a gram-negative bacterium isolated from the poplar rhizosphere, surface-attached cells observed after a brief incubation (~30 min) were typically around 2 µm in length and 1 µm in diameter, corresponding to a surface area of ~2 μm², aligning with previous findings [1]. AFM imaging provided structural details not achievable with optical microscopy or other methods, enabling visualization of flagellar structures around the cells, measuring ~20–50 nm in height and extending tens of micrometers across the surface [1]. Some appendages appeared to originate from individual cells, while others seemed to adhere to the surface, possibly from detached cells [1]. The identification of these structures as flagella was confirmed using a flagella-deficient control strain, which showed no similar appendages under AFM [1].

In cells allowed to propagate on the surface for a period of 6–8 h formed clusters with characteristic honeycomb-like gaps [1]. AFM's high-resolution capability allowed clear visualization of individual cells and flagella [1]. In Pantoea sp. YR343, AFM revealed flagellar structures bridging gaps during early cell attachment and development [1]. These detailed visualizations are critical, as appendages like flagella are essential for biofilm development, surface attachment, and motility [1]. Without high-resolution imaging, such structural intricacies would be impossible to observe [1].

AFM as a Surface Mapping Tool in Microorganisms Resistant Toward Antimicrobials

The worldwide emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in pathogenic microorganisms, including bacteria and viruses due to a plethora of reasons, such as genetic mutation and indiscriminate use of antimicrobials, is a major challenge faced by the healthcare sector today [18]. One of the issues at hand is to effectively screen and isolate resistant strains from sensitive ones [18]. Utilizing the distinct nanomechanical properties (e.g., elasticity, intracellular turgor pressure, and Young's modulus) of microbes can be an intriguing way to achieve this; while atomic force microscopy (AFM), with or without modification of the tips, presents an effective way to investigate such biophysical properties of microbial surfaces or an entire microbial cell [18]. Additionally, advanced AFM instruments, apart from being compatible with aqueous environments—as often is the case for biological samples—can measure the adhesive forces acting between AFM tips/cantilevers (conjugated to bacterium/virion, substrates, and molecules) and target cells/surfaces to develop informative force-distance curves [18]. Moreover, such force spectroscopies provide an idea of the nature of intercellular interactions (e.g., receptor-ligand) or propensity of microbes to aggregate into densely packed layers, that is, the formation of biofilms—a property of resistant strains (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) [18]. This mini-review will revisit the use of single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) and single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) that are emerging as powerful additions to the arsenal of researchers in the struggle against resistant microbes, identify their strengths and weakness and, finally, prioritize some future directions for research [18].

Biofilm Cohesiveness Measurement Using a Novel Atomic Force Microscopy Method

Biofilms can be undesirable, as in those covering medical implants, and beneficial, such as when they are used for waste treatment [19]. Because cohesive strength is a primary factor affecting the balance between growth and detachment, its quantification is essential in understanding, predicting, and modeling biofilm development [19]. In this study, we developed a novel atomic force microscopy (AFM) method for reproducibly measuring, in situ, the cohesive energy levels of moist 1-day biofilms [19]. The biofilm was grown from an undefined mixed culture taken from activated sludge [19]. The volume of biofilm displaced and the corresponding frictional energy dissipated were determined as a function of biofilm depth, resulting in the calculation of the cohesive energy [19]. Our results showed that cohesive energy increased with biofilm depth, from 0.10 ± 0.07 nJ/μm³ to 2.05 ± 0.62 nJ/μm³ [19]. This observation was reproducible, with four different biofilms showing the same behavior [19]. Cohesive energy also increased from 0.10 ± 0.07 nJ/μm³ to 1.98 ± 0.34 nJ/μm³ when calcium (10 mM) was added to the reactor during biofilm cultivation [19]. These results agree with previous reports on calcium increasing the cohesiveness of biofilms [19]. This AFM-based technique can be performed with available off-the-shelf instrumentation [19]. It could therefore be widely used to examine biofilm cohesion under a variety of conditions [19].

It is essential to understand biofilm stability to both encourage biofilm maintenance in some applications, such as waste treatment, and effectively remove undesired biofilm in others, as in biofilms covering medical implants [19]. Biofilm detachment is one of the critical factors that balance growth and plays a role in the development of biofilm spatial heterogeneity [19]. While factors responsible for biofilm growth are well studied, those controlling the detachment process are not clearly understood [19]. As a consequence, a good understanding of the relationships between operating conditions and biofilm cohesion is lacking [19]. The cohesive strength of the biofilm is influenced by extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and specific compounds, such as calcium, which fill the space between microbial cells and bind cells together [19]. Understanding the cohesive interactions in the biofilm matrix under a variety of conditions could lead to the design of new strategies for controlling biofilm development based on disrupting or protecting the matrix holding the biofilm together [19].

Because cohesive strength is a primary factor affecting biofilm sloughing, its quantification is essential in understanding detachment [19]. A few methods based on the use of custom devices have been proposed to investigate biofilm cohesive strength [19]. Poppele and Hozalski measured the tensile strength levels of biofilms from activated sludge by using a micromechanical device based on the deflection of a glass micropipette separating a microbial aggregate held by suction [19]. Körstgens et al. used a uniaxial compression measurement device to determine the yield strength levels and the apparent moduli of elasticity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms [19]. Ohashi and Harada used rotation and collision devices and found that the shear strength levels of denitrifying biofilms were higher than the tensile strength levels by 2 orders of magnitude [19]. In addition, Ohashi et al., by assuming that a biofilm behaves as an elastic material, found a correlation between the elastic coefficient and tensile strength [19]. Not surprisingly, data reported on biofilm strength measured under different types of deformation using custom devices are different and inherently difficult to compare [19].

In the past few years, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been used to image film morphologies and probe surface properties, such as ligand and receptor interactions and viscoelasticity [19]. AFM provides three-dimensional images of a surface ultrastructure with molecular or near-molecular resolution under physiological conditions and with minimal sample preparation [19]. Benoit et al. attached a single microbial cell to an AFM cantilever and measured cell-cell interactions at a molecular level [19]. Emerson and Camesano investigated pathogenic microbial adhesion to biomaterials by measuring the local interaction forces between an immobilized cell and both biomaterial and biofilm surfaces [19]. Cell surface hydrophobicity and charge have also been investigated using chemically functionalized AFM probes [19]. All of these studies and measurements provide important information on single-cell properties; nevertheless, they do not provide information on the properties of whole biofilms [19].

Because of the difficulties associated with working with biofilms, particularly their softness and gelatinous nature, most biofilms imaged by AFM have been dried first [19]. Drying is expected to significantly change the strength and overall character of a biofilm; therefore, measurements made on dry biofilm must be interpreted and applied carefully [19]. A few AFM studies have investigated biofilm properties, such as interaction and attachment to surfaces under aqueous conditions [19]. Yet, there is a real need to expand this work to study additional properties of whole biofilms under aqueous conditions [19].

AFM also has been extensively employed to image and gauge the frictional properties of organic and polymeric surfaces [19]. The frictional response is well known to have a large contribution from the viscous character of the material being imaged [19]. Some investigators have examined response functions by characterizing friction and/or wear under repeated scanning with variable loads, providing information on the viscoelastic and viscoplastic properties of a material [19].

To our knowledge, concomitant friction and wear processes on biofilms, important for understanding shear-induced detachment, have not been investigated [19]. In this paper, we develop an AFM method for reproducibly measuring, in situ, frictional-energy dissipation on moist biofilms during abrasion via a raster-scanned tip under an elevated load [19]. Also, we quantify the volume of detached biofilm via before/after topographic image comparisons [19]. We use this methodology to reproducibly determine the cohesion, or cohesive energy level, of a volume of moist biofilm (nJ/μm³) [19]. Besides reproducibility and simplicity, this method also has the nanoscale level capability of being able to measure in situ cell/EPS and EPS/EPS interactions within a well-defined volume of biofilm [19].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: AFM-Measured Nanomechanical Properties of Biofilm Components

| Biofilm Component | Elastic Modulus (MPa) | Adhesion Force (nN) | Cohesive Energy (nJ/μm³) | Key Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young Biofilm (1-day) | N/A | N/A | 0.10 ± 0.07 to 2.05 ± 0.62 | Depth-dependent measurement in moist conditions [19] |

| Biofilm with Calcium | N/A | N/A | 0.10 ± 0.07 to 1.98 ± 0.34 | With 10 mM CaCl₂ addition [19] |

| Microbial Cells | Variable by species | 0.1 - 10 | N/A | Measured via single-cell force spectroscopy [18] |

| EPS Matrix | 0.1 - 100 | 5 - 50 | N/A | Highly dependent on composition and hydration [17] |

Table 2: AFM Imaging Parameters for Biofilm Characterization

| Imaging Mode | Resolution | Optimal Conditions | Applications in Biofilm Research | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact Mode | 1-10 nm | Hard, dry samples | High-resolution topology mapping | High lateral forces can damage soft samples [17] |

| Tapping Mode | 1-10 nm | Soft, hydrated samples | Imaging live cells and delicate biofilm structures | Reduced scanning speed [17] |

| Force Spectroscopy | Molecular level | Physiological conditions | Adhesion forces, receptor-ligand interactions, nanomechanics | Point-by-point measurement [17] [18] |

| Large Area Automated AFM | Subcellular level | Machine learning integration | Millimeter-scale biofilm organization | Requires advanced instrumentation [1] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Biofilm Preparation and AFM Imaging in Physiological Conditions

Materials Required:

- Membrane-aerated biofilm reactor

- Activated sludge inoculum

- Polyolefin flat sheet membrane (0.1-μm mean pore diameter)

- AFM with humidity control chamber (e.g., PicoSPM)

- V-shaped cantilevers with pyramidal Si₃N₄ tips (spring constant 0.58 N/m)

Procedure:

- Inoculate a 10-liter completely mixed reactor with activated sludge containing diverse bacterial community [19]

- Maintain bulk reactor conditions at 147 ± 37 mg/liter chemical oxygen demand and 28 ± 8 mg/liter ammonia nitrogen [19]

- Submerge membrane test modules in reactor for 1-day biofilm growth [19]

- Remove membrane modules and cut 1 × 1 cm pieces with attached biofilm [19]

- Equilibrate samples in saturated NaCl solution (∼90% humidity) for 1 hour [19]

- Mount samples in AFM humidity chamber controlled at 90% humidity [19]

- Collect non-perturbative topographic images at low applied load (∼0 nN) [19]

- For abrasion studies: zoom into 2.5 × 2.5-μm subregion and abrade under repeated raster scanning at elevated load (40 nN) [19]

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy for Antimicrobial Resistance Studies

Materials Required:

- Functionalized AFM cantilevers

- Microbial cell cultures (sensitive and resistant strains)

- Appropriate growth media

- AFM with force spectroscopy capability

- Cell immobilization substrates (e.g., PDMS stamps, poly-l-lysine coated surfaces)

Procedure:

- Immobilize microbial cells using mechanical entrapment or chemical fixation methods [17]

- Functionalize AFM cantilevers with appropriate ligands or cells [18]

- Approach cantilever to surface at controlled velocity (0.5-1 μm/s)

- Record force-distance curves at multiple locations

- Analyze adhesion forces, rupture events, and mechanical properties

- Compare nanomechanical signatures between sensitive and resistant strains [18]

- Perform statistical analysis on multiple cells (typically n > 50)

Protocol 3: Large Area Automated AFM with Machine Learning Integration

Materials Required:

- Automated AFM system with large scan range

- Machine learning software for image analysis

- Biofilm samples on appropriate substrates

- Computational resources for data processing

Procedure:

- Grow biofilms on selected surfaces (e.g., PFOTS-treated glass) [1]

- Implement automated scanning protocol with minimal overlap between images [1]

- Use ML algorithms for seamless image stitching [1]

- Apply automated segmentation for cell detection and classification [1]

- Extract parameters: cell count, confluency, cell shape, and orientation [1]

- Analyze spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology over millimeter-scale areas [1]

Visualization Diagrams

Diagram 1: AFM Workflow for Biofilm Mechanical Characterization

Diagram 2: Biofilm Resistance Mechanisms Accessible by AFM

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AFM Biofilm Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Stamps | Cell immobilization | Customizable pore sizes (1.5-6 µm) for mechanical entrapment [17] |

| Poly-l-lysine Coated Surfaces | Chemical immobilization | Provides charged surface for cell attachment [17] |

| Functionalized AFM Cantilevers | Force spectroscopy | Tips modified with specific ligands or cells [18] |

| Si₃N₄ Tips (Pyramidal) | Standard imaging | 0.58 N/m spring constant for biofilm studies [19] |

| Calcium Chloride (10 mM) | Cohesion modulation | Increases biofilm cohesive energy [19] |

| PFOTS-treated Glass | Adhesion substrates | Promotes bacterial attachment for early biofilm studies [1] |

| Humidity Control System | Environmental control | Maintains 90% humidity for hydrated biofilm measurement [19] |

AFM has proven itself to be a powerful and diverse tool for the study of microbial systems on both single and multicellular scales including complex biofilms [17]. This chapter has reviewed how AFM and its derivatives have been used to unravel the nanoscale forces governing the structure and behavior of biofilms, thus providing unique insight into the control of microbial populations within clinical and industrial environments [17]. Diversification of AFM-based technologies has allowed for the creation of a truly multiparametric platform, enabling the interrogation of all aspects of microbial systems [17]. Advances in traditional AFM operation have allowed, for the first time, insight into the topographical landscape of both microbial cells and spores, which, when combined with high-speed AFM's ability to resolve the structure of surface macromolecules, have provided, with unparalleled detail, visualization of this complex environmental interface [17]. The application of AFM force spectroscopies has enabled the analysis of many microbial nanomechanical properties including macromolecule folding pathways, receptor ligand binding events, microbial adhesion forces, biofilm mechanical properties, and antimicrobial/antibiofilm affectivities [17]. Thus, AFM has offered an outstanding glimpse into the biofilm, how its inhabitants create and use this complex adaptive interface, and perhaps most importantly what can be done to control this [17]. The continued development of automated large-area AFM approaches combined with machine learning analysis promises to further enhance our understanding of biofilm organization and resistance mechanisms at scales relevant to their natural environments [1].

A Practical Guide to Fluid AFM: From Setup to Anti-Biofilm Agent Evaluation

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) enables the high-resolution structural and functional characterization of biofilms under native, physiological conditions, a capability critical for understanding their development, resilience, and response to treatments [1]. Performing these investigations in a liquid environment is paramount to maintaining biofilm viability, minimizing disruptive surface forces on delicate samples, and generating biologically relevant data [20] [21]. The configuration of the AFM liquid cell—encompassing the probe, imaging media, and environmental controls—is a foundational step that directly determines the success of the experiment. This application note provides detailed protocols for configuring the liquid cell for AFM-based biofilm research, framed within the context of advanced studies investigating biofilm assembly and nanomechanical properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues the key materials required for preparing and conducting AFM experiments on biofilms in liquid.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AFM Biofilm Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Probes | High-resolution imaging and force spectroscopy in liquid. | Small cantilevers (e.g., USC-F1.5-k0.6) for high-frequency measurements; PPP-CONTPt for mechanical mapping [22] [21]. |

| Fluid Cantilever Holder | Enables laser reflection and scanner protection in liquid. | BioScope Resolve Fluid Holder; Electrochemical Cell (ECCell) for specialized setups [20] [21]. |

| Substrates | Surface for biofilm growth and adhesion during AFM. | PFOTS-treated glass; indium-tin-oxide (ITO)-coated glass for superior cell adhesion in liquid [1] [21]. |

| Culture Media | Provides physiological conditions for hydrated, living biofilms. | Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS); specific liquid growth medium tailored to the bacterial strain (e.g., for Pantoea sp.) [1] [9]. |

| Biofilm Samples | Model systems for investigation. | Pantoea sp. YR343; Rhodococcus wratislaviensis; biofilms grown on functionalized beads [1] [9] [21]. |

Quantitative Configuration Parameters for AFM Liquid Cells

Optimal AFM performance in liquid is achieved by carefully balancing a set of quantitative parameters. The following table summarizes critical settings for different experimental modalities.

Table 2: Quantitative AFM Configuration Parameters for Biofilm Research in Liquid

| Parameter | Typical Range/Specification | Experimental Context & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Cantilever Stiffness | 0.1 - 0.6 N/m | Softer cantilevers (≈0.3 N/m) are used for high-resolution imaging and force spectroscopy on soft biological samples to minimize sample damage [21] [23]. |

| Imaging Force | < 1 nN | A low setpoint force is critical for non-destructive imaging, preserving native biofilm structure and avoiding cell displacement [21]. |

| Indentation Speed | 17 - 175 mN/s | Used in force mapping modes (e.g., Quantitative Imaging) to derive nanomechanical properties from approach curves [21]. |

| Shear Amplitude | < 7 nm | Applied in nanorheology measurements to probe local viscoelasticity without disrupting the biofilm matrix [22]. |

| Shear Frequency | 1 kHz - 50 kHz | Higher frequencies (e.g., 50 kHz) are necessary to measure the viscous response of fluid membranes and biofilm components [22]. |

| Temperature Control | 24.0 ± 0.2 °C | Precise temperature regulation is essential for maintaining biofilm viability and consistency in nanomechanical measurements [22] [21]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key AFM Biofilm Investigations

Protocol: Large-Area AFM Imaging of Early Biofilm Assembly

This protocol, adapted from Millan-Solsona et al., is designed to capture the spatial heterogeneity of nascent biofilms over millimeter scales [1].

1. Substrate Preparation: - Clean glass coverslips via oxygen plasma or UV-ozone treatment. - Functionalize the coverslips with PFOTS (Perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane) to create a hydrophobic surface that promotes specific bacterial adhesion. - Sterilize the PFOTS-treated coverslips under UV light for 30 minutes before use.

2. Biofilm Growth and Sample Loading: - Inoculate a petri dish containing the prepared coverslips with a liquid culture of the target bacterium (e.g., Pantoea sp. YR343). - Incubate for the desired initial attachment period (e.g., 30 minutes). - Gently rinse the coverslip with sterile buffer to remove non-adherent planktonic cells. - For fixed-timepoint imaging, air-dry the sample briefly before mounting. For live imaging, keep the sample hydrated. - Mount the coverslip onto the AFM metal sample puck using a small amount of double-sided adhesive. - Carefully place the puck onto the AFM scanner.

3. Liquid Cell Assembly and Probe Selection: - Install the fluid cantilever holder onto the AFM head. - Select a sharp, non-contact silicon nitride cantilever with a nominal spring constant of ~0.3 N/m. - Load the cantilever into the holder and align the laser spot to the cantilever's end. - Pipette an appropriate physiological buffer or culture medium into the liquid cell, ensuring the cantilever and sample are fully immersed without introducing air bubbles.

4. Automated Large-Area Scanning: - Engage the AFM in a gentle imaging mode (e.g., AC mode in liquid or Quantitative Imaging mode). - Define a large-area grid (up to millimeter-scale) through the AFM software. - Initiate the automated scanning sequence. The system will acquire multiple contiguous high-resolution images. - Use integrated machine learning algorithms for seamless stitching of individual tiles and subsequent automated cell detection, classification, and morphological analysis [1].

Protocol: Nanomechanical Mapping of Living Biofilms in Liquid

This protocol details the procedure for generating spatially resolved maps of the mechanical properties of a biofilm in its native state [21] [23].

1. Sample Preparation without Immobilization: - Use ITO-coated glass substrates to promote strong, natural bacterial adhesion without chemical fixation or mechanical entrapment [21]. - Pipette a volume of bacterial culture in its exponential growth phase directly onto the ITO substrate. - Allow the cells to settle and adhere for a predetermined time (e.g., 10-30 minutes) within the AFM liquid cell.

2. AFM Setup for Force Mapping: - Install the fluid cell and select a cantilever suitable for force spectroscopy (e.g., PPP-CONTPt, k ≈ 0.3 N/m). - Align the laser and calibrate the cantilever's sensitivity in liquid. - Determine the cantilever's spring constant using the thermal tune method.