Probing Biofilm Nanomechanics with Atomic Force Microscopy: From Fundamental Principles to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of how Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is revolutionizing the quantification of biofilm nanomechanical properties.

Probing Biofilm Nanomechanics with Atomic Force Microscopy: From Fundamental Principles to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of how Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is revolutionizing the quantification of biofilm nanomechanical properties. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles of AFM operation for measuring elasticity, adhesion, and cohesion in biofilms. The content explores cutting-edge methodological advances, including automated large-area scanning, single-cell and biofilm-scale force spectroscopy, and correlative microscopy. It also addresses key challenges in sample preparation, data interpretation, and optimization through AI integration. By comparing AFM with traditional biofilm characterization techniques and highlighting its unique quantitative advantages, this review serves as an essential resource for developing innovative anti-biofilm strategies and therapeutic interventions.

Fundamental Principles: How AFM Quantifies Biofilm Nanomechanics

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) is a powerful scanning probe technique capable of achieving nanometer-scale resolution. Beyond high-resolution imaging, a key strength of AFM is force spectroscopy, which measures interaction forces between the AFM probe and a sample. In biofilm research, this technique is invaluable for quantifying the nanomechanical properties that govern biofilm behavior, such as their adhesion, elasticity, and viscoelasticity [1] [2] [3].

In a typical force spectroscopy experiment, a sharp probe attached to a flexible cantilever is brought into contact with the sample and then retracted. The cantilever's deflection is recorded as a function of the probe's position, generating a force-distance curve. This curve contains a wealth of information about the mechanical and adhesive interactions at the probe-sample interface [3] [4]. The interpretation of these curves is foundational to the data presented in this application note.

Key Applications in Biofilm Research

AFM force spectroscopy can be applied to study biofilms at multiple scales, from the single-molecule to the community level. Key applications include:

- Single-Cell and Single-Molecule Analysis: Probing the mechanical properties of individual bacterial cells, unfolding surface proteins, and measuring the binding strength of individual adhesion molecules [2] [4].

- Quantification of Cell-Surface and Cell-Cell Adhesion: Measuring the forces that govern the initial attachment of bacteria to surfaces (a critical first step in biofilm formation) and the cohesion between cells within the biofilm matrix [5] [2].

- Mapping of Biofilm Viscoelasticity: Characterizing the time-dependent mechanical response of the biofilm, which determines its structural integrity, resistance to stresses, and dispersal mechanisms [5] [6].

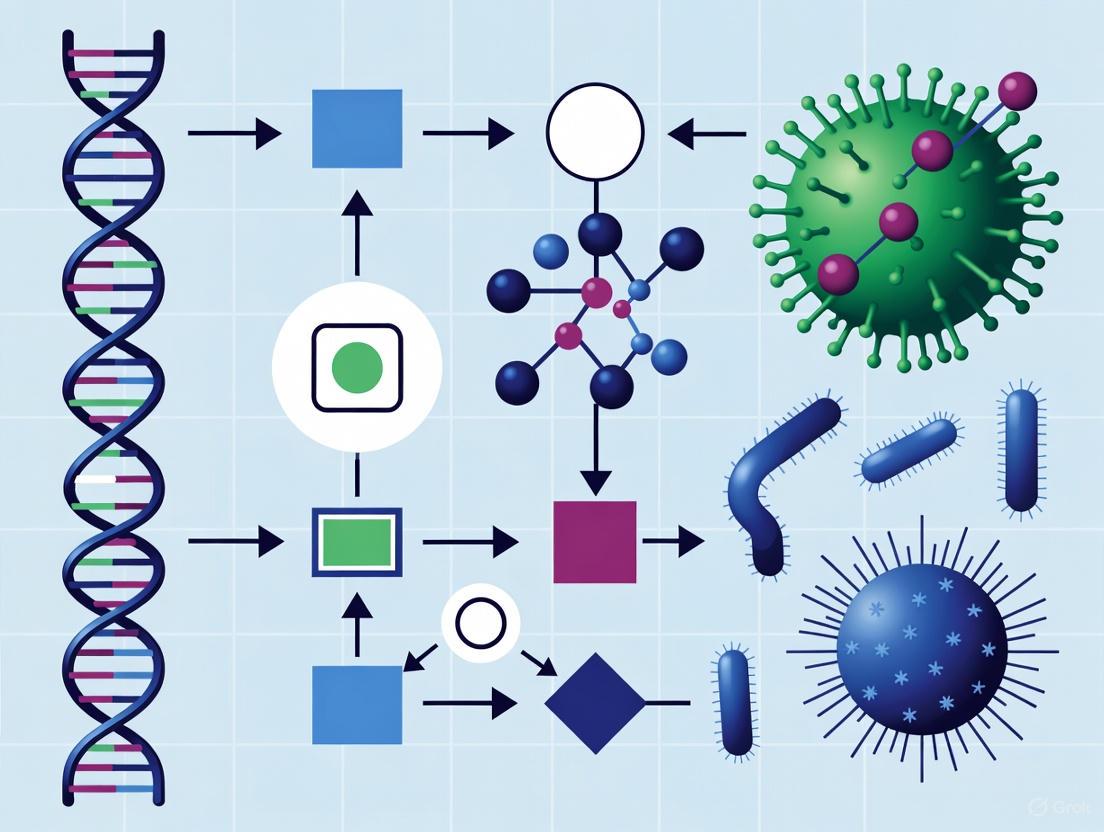

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for an AFM force spectroscopy experiment on a biofilm, from probe preparation to data acquisition.

Quantitative Mechanical Properties of Biofilms

AFM force spectroscopy provides absolute quantitation of key biofilm properties. The data in the table below, derived from a study on Pseudomonas aeruginosa, exemplifies how this technique can distinguish the mechanical properties of different bacterial strains and biofilm maturation stages [5].

Table 1: Adhesive and Viscoelastic Properties of P. aeruginosa Biofilms

| Biofilm Sample | Adhesive Pressure (Pa) | Instantaneous Elastic Modulus (Pa) | Delayed Elastic Modulus (Pa) | Viscosity (Pa·s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1 (Early) | 34 ± 15 | |||

| PAO1 (Mature) | 19 ± 7 | |||

| wapR mutant (Early) | 332 ± 47 | |||

| wapR mutant (Mature) | 80 ± 22 | |||

| Key Finding | LPS deficiency (wapR) significantly increases early biofilm adhesion. | LPS deficiency and biofilm maturation drastically reduce elastic moduli. | Maturation decreases viscosity. |

Note: Data acquired using Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) with a Voigt Standard Linear Solid model for viscoelasticity. wapR is a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) mutant strain. Standard deviations shown [5].

The combination of AFM with other techniques creates a powerful multi-scale analysis framework. For instance, correlating AFM-derived mechanical properties with mesoscale structural information from Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) reveals how biofilm structure and mechanical function are interrelated [7].

Table 2: Multi-Scale Correlation of Sucrose, Structure, and Mechanics in Oral Biofilms

| Sucrose Concentration | Biofilm Age | OCT Mesoscale Feature | Young's Modulus (Elasticity) | Cantilever Adhesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (0.1% w/v) | 3 & 5 Days | Regions of low EPS density | Higher | Lower |

| High (5% w/v) | 3 & 5 Days | Regions of high EPS density | Lower | Higher |

| Key Finding | High sucrose increases EPS production. | Increased EPS content directly reduces stiffness and increases adhesion. | Age increases bacterial proliferation, reducing adhesive contact. |

Note: EPS = Extracellular Polymeric Substances. Young's modulus and adhesion were measured using AFM with borosilicate sphere-modified cantilevers [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) for Adhesion and Viscoelasticity

This protocol describes a standardized method for quantifying the adhesive and viscoelastic properties of bacterial biofilms using a spherical probe [5].

1. Probe Preparation: * Cantilever Selection: Use rectangular tipless silicon cantilevers (e.g., Mikromasch CSC12/Tipless). * Spring Constant Calibration: Calibrate the cantilever's spring constant in fluid using the thermal noise method [5] [4]. * Microbead Attachment: Attach a clean, 50 µm diameter glass bead to the cantilever using a UV-curing resin.

2. Biofilm Sample Preparation: * Strain and Growth: Grow the bacterial strain of interest (e.g., P. aeruginosa PAO1) to the desired growth phase. * Cell Harvesting: Harvest cells by centrifugation, wash twice in deionized water, and resuspend to a standardized optical density (e.g., OD600 = 2.0). * Biofilm Coating: Coat the glass bead probe by immersing it in the concentrated cell suspension for a defined period to form an early biofilm layer.

3. Force Spectroscopy Measurement: * Instrument Setup: Perform measurements with a closed-loop AFM system submerged in liquid. * Standardized Conditions: To enable cross-experiment comparison, use standardized parameters for loading force, surface contact time, and retraction speed. * Data Acquisition: Approach the biofilm-coated bead to a clean glass substrate in the fluid cell. Record force-distance curves during approach, contact (hold), and retraction cycles. Collect hundreds of curves at different locations for statistical robustness.

4. Data Analysis: * Adhesion Pressure: Calculate the adhesive pressure from the maximum pull-off force in the retraction curve, divided by the contact area between the bead and substrate [5]. * Viscoelastic Modeling: Fit the creep response data (indentation vs. time during the hold period) to a viscoelastic model (e.g., Voigt Standard Linear Solid model) to extract the instantaneous elastic modulus, delayed elastic modulus, and viscosity [5].

Protocol: Immobilization of Bacterial Cells for Single-Cell Analysis

Secure immobilization is critical for high-resolution AFM imaging and force measurement on single cells. The following methods are commonly employed [2].

Mechanical Entrapment: * Porous Membranes: Use microfiltration membranes with pore sizes similar to the cell diameter to physically trap bacteria. * PDMS Micro-Wells: Use soft lithography to create polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps with microwells (e.g., 1.5–6 µm wide, 1–4 µm deep) designed to trap individual cells via convective and capillary forces [2].

Chemical Fixation: * Adhesive Coatings: Functionalize glass or mica substrates with cell-adhesive compounds such as poly-L-lysine or gelatin. * Cationic Enhancement: Improve attachment by adding divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) to the immobilization buffer. * Covalent Binding: Use cross-linkers like glutaraldehyde for firm fixation, noting that this may affect cell viability and nanomechanical properties.

The data acquisition and analysis workflow for processing force-distance curves is detailed below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AFM Biofilm Mechanics

| Item | Function and Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Cantilevers | Transducer for force measurement; choice depends on experiment. | Tipless Cantilevers: For bead attachment (e.g., Mikromasch CSC12). Sharp Tips: For high-resolution imaging and single-cell indentation. |

| Functionalized Probes | To measure specific interactions or defined contact geometry. | Microbead Probes: 10-50 µm spheres for well-defined contact area [5] [7]. Cell-Probes: A single bacterium attached to a tipless cantilever to probe cell-surface interactions [2]. |

| Bacterial Strains | Model organisms for biofilm research. | Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1: Common gram-negative model bacterium [5]. Escherichia coli MG1655: Common gram-negative model for genetic studies [6]. |

| Immobilization Substrates | To securely hold biofilm or cells for measurement. | Functionalized Glass/Mica: Treated with poly-L-lysine or other adhesives. Porous Membranes/PDMS stamps: For mechanical entrapment of cells [2]. |

| Growth Media | To cultivate and maintain biofilms under defined conditions. | Nutrient-Rich/Poor Media: To study the effect of nutrients on biofilm mechanics (e.g., BHI-based vs. artificial saliva media) [7]. |

Advanced Techniques and Future Outlook

The field of AFM biofilm nanomechanics is rapidly advancing. Key developments include:

- Large-Area Automated AFM: Traditional AFM scan sizes are limited. New automated systems can now perform high-resolution imaging and force mapping over millimeter-scale areas, capturing the inherent heterogeneity of biofilms and linking cellular features to community-scale organization [8].

- Machine Learning Integration: AI and machine learning are being applied to automate image stitching, cell detection, classification, and the analysis of large force spectroscopy datasets, significantly enhancing throughput and objectivity [8].

- Magnetic Tweezers Microrheology: This complementary technique involves infiltrating magnetic microparticles into a growing biofilm. Using magnetic tweezers to apply force and track particle displacement allows for the 3D mapping of local viscoelastic properties within an intact, living biofilm [6].

- Correlative Microscopy: Combining AFM with other techniques like Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) or confocal laser scanning microscopy provides a multi-scale view, correlating nanomechanical properties with mesoscale biofilm architecture and composition [7].

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a pivotal tool for quantifying the nanomechanical properties of bacterial biofilms, providing critical insights into their structural integrity and functional behavior. By operating in force spectroscopy mode, AFM enables in situ measurement of key mechanical parameters—elasticity, adhesion, and cohesion—that govern biofilm development and stability. These properties are not merely descriptive; they fundamentally influence how biofilms respond to mechanical stress, antibiotic treatments, and immune system attacks. The nanomechanical characterization of biofilms reveals how bacterial cells and their extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) interact to form complex, resilient structures on both biotic and abiotic surfaces.

Understanding these nanomechanical properties provides a biophysical foundation for developing strategies to combat biofilm-associated infections, particularly on indwelling medical devices where biofilms pose significant clinical challenges [9]. The measurement of cellular spring constants and adhesive forces between the AFM tip and biofilm components offers a window into the molecular interactions that underpin biofilm assembly and robustness. Furthermore, the mechanical properties of living cells, including their stiffness and glycocalyx integrity, have direct implications for physiological and pathological processes, such as endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease [10]. This application note details standardized protocols for quantifying these essential nanomechanical properties, enabling researchers to obtain consistent, reproducible data that can advance both basic science and therapeutic development.

Quantitative Data on Biofilm Nanomechanics

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from AFM nanomechanics studies on bacterial biofilms and cellular systems, providing reference values for elasticity and adhesion measurements.

Table 1: Bacterial Cellular Spring Constants Measured by AFM [11]

| Bacterial Strain Type | Spring Constant (N/m) | Standard Error | Significant Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive Cells | 0.41 | ± 0.01 | Generally higher elasticity |

| Gram-negative Cells | 0.16 | ± 0.01 | Generally lower elasticity |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (Wild Type) | Variable with capsule | - | Affected by fimbriae presence [9] |

Table 2: Adhesive Properties in Bacterial Biofilms [11]

| Cell Type | Adhesive Force Components | Distance Components | Number of Adhesion Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative Cells | Multiple | Longest (up to >1 μm) | Variable |

| Gram-positive Cells | Multiple | Shortest | Variable |

| Chemical Fixation (NHS, EDC) | Perturbed | Perturbed | Altered |

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for AFM Biofilm Nanomechanics [11] [10] [9]

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Heparinase | Enzymatic removal of glycocalyx | Quantifying glycocalyx height and mechanical properties [10] |

| Jasplakinolide | Polymerization of actin mesh | Investigating cortical cytoskeleton stiffness [10] |

| Cytochalasin D | Depolymerization of actin | Investigating cortical cytoskeleton softening [10] |

| Silicon Nitride AFM Tip | Nanomechanical probing | Standard tip for force curve acquisition |

| NHS & EDC | Chemical fixation agents | Study of fixation effects on cell mechanics (note: perturbs native properties) [11] |

| HUVECs (Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells) | Gold standard cell model | Ex vivo studies of endothelial nanomechanics [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Measuring Cellular Elasticity (Spring Constant)

Principle: The cellular spring constant is determined from the slope of the extension portion of AFM force-distance curves, reflecting the cell's resistance to deformation [11].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grow bacterial biofilms (e.g., Klebsiella pneumoniae wild type and mutants) or relevant cell lines on sterile glass substrates for at least 3-4 days to ensure proper glycocalyx development [10]. Maintain in appropriate physiological buffer (e.g., PBS at optimal pH and salt content) during measurement.

- AFM Setup: Mount a standard silicon nitride AFM tip. For living cell measurements, use a spherical tip (e.g., 1μm diameter) and apply very low loading forces (~0.5 nanonewtons) to prevent damage to vulnerable structures like the glycocalyx [10].

- Data Acquisition: Approach the AFM tip to the cell surface until contact is established. Perform a series of tip extension and retraction cycles at multiple locations across the sample surface. The extension curve (indentation) provides the data for elasticity calculation.

- Data Analysis: Model the extending portion of the force curve. The slope of the linear region corresponds to the spring constant. For bacterial cells, typical values range from 0.16 N/m for Gram-negative cells to 0.41 N/m for Gram-positive cells [11]. Analyze the nonlinear regime of the extension curve to gain insights into surface biomolecules, noting that bacterial strains with longer surface lipopolysaccharides often exhibit larger nonlinear regions [11].

Protocol for Quantifying Adhesive Forces

Principle: Adhesive interactions are quantified from the retraction portion of force-distance cycles, measuring the force required to separate the AFM tip from the sample surface [11].

Procedure:

- Sample and AFM Setup: Follow the sample preparation and AFM setup steps described in the elasticity protocol (Section 3.1).

- Force Curve Collection: Execute multiple approach-retract cycles at different locations. Focus on the retraction curve, which will show adhesion "pull-off" events.

- Adhesion Analysis: Quantify the adhesive forces from the retraction curve. Analyze these forces in terms of their magnitude, the distance over which they occur (distance components), and the frequency (number of adhesion events). Gram-negative cells often exhibit adhesion events with the longest distance components, sometimes exceeding 1 micrometer, whereas Gram-positive cells typically show much shorter-range adhesion [11].

Protocol for Assessing Glycocalyx and Cortical Mechanics in Endothelial Cells

Principle: This specialized protocol uses enzymatic treatment and cytoskeletal manipulation to dissect the mechanical contributions of the glycocalyx and the underlying cortical cytoskeleton [10].

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Use freshly isolated HUVECs or similar endothelial cells cultured for at least three to four days to allow for proper glycocalyx recovery and maturation [10].

- Experimental Manipulation:

- Glycocalyx Removal: Treat cells with heparinase to enzymatically remove the glycocalyx, enabling quantification of its specific height and mechanical properties [10].

- Cytoskeleton Modulation: Use jasplakinolide to polymerize the cortical actin mesh (increasing stiffness) or cytochalasin D to depolymerize it (decreasing stiffness) [10].

- AFM Measurement: Perform AFM indentation measurements with a soft, spherical probe and low loading force as described in Section 3.1.

- Curve Analysis: Analyze the resulting complex force curves, which will feature several slopes. The initial indentation region (first few nanometers) corresponds to the glycocalyx, while deeper indentation probes the plasma membrane and the underlying cortical cytoskeleton. This analysis can take weeks to complete thoroughly [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following toolkit is essential for conducting AFM-based nanomechanics research on biofilms and cells.

- Gwyddion Software: A free, open-source modular program for SPM (Scanning Probe Microscopy) data visualization and analysis. It supports a vast array of SPM data formats and provides numerous data processing functions, including statistical characterization, leveling, data correction, and filtering. Its active development and support for multiple operating systems (GNU/Linux, Windows, Mac OS X) make it an invaluable tool for the analysis of AFM height fields and force data [12].

- Bruker BioAFM Systems: Modern, user-friendly AFM instruments that are suitable for measuring the mechanical properties of living cells in a physiological environment. These systems enable researchers to observe online how a living cell reacts when substances are applied [10].

- Standardized HUVECs (Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells): Sourced from hospitals and freshly isolated, these cells serve as a gold standard model for studying endothelial nanomechanics, especially in projects involving patient serum incubation to diagnose endothelial dysfunction [10].

- CRISPR-Cas Systems: Used for knocking out specific channels in cells to study their role in nanomechanical properties, enabling precise genetic manipulation to establish structure-function relationships [10].

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for AFM-based nanomechanics.

AFM Nanomechanics Workflow

The relationship between cortical stiffness and glycocalyx integrity is a key pathway in cellular nanomechanics, as shown in the following diagram.

Cytoskeleton-Glycocalyx Pathway

Force-Distance Curve Analysis and Mathematical Models (Hertz, JKR, DMT)

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) has established itself as a pivotal technique in the field of biofilm nanomechanics research, enabling the quantitative assessment of mechanical properties at the nanoscale. By analyzing force-distance curves, researchers can probe the viscoelastic behavior of biofilms, which is crucial for understanding their development, stability, and response to antimicrobial agents [13]. This application note details the protocols for obtaining and analyzing force-distance curves using contact mechanics models—Hertz, Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR), and Derjaguin-Müller-Toporov (DMT)—within the specific context of biofilm characterization. The integration of rheology and AFM provides comprehensive insights into biofilm structure-function relationships, informing the development of effective control strategies in food, healthcare, and environmental industries [13]. The following sections provide a structured guide to the mathematical models, experimental protocols, and data analysis procedures essential for advanced biofilm nanomechanics research.

Theoretical Models in Contact Mechanics

The analysis of force-distance curves relies on contact mechanics models to extract quantitative mechanical properties such as elastic modulus. The choice of model depends on the specific sample properties, particularly the adhesive forces between the tip and the sample.

Table 1: Key Contact Mechanics Models for AFM Force-Distance Curve Analysis

| Model | Governing Equation | Applicable Scenarios | Adhesion Handling | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hertz | ( F = \frac{4}{3} E_{tot} \sqrt{R} \delta^{3/2} ) [14] | Rigid indenters, negligible adhesion, small tips and stiff samples [14] | Neglects adhesion forces | ( E_{tot} ): Effective elastic modulus, ( R ): Tip radius, ( \delta ): Indentation |

| JKR | ( F = \frac{4}{3} E{tot} \sqrt{R \delta^3} - \sqrt{8 \pi W E{tot} \sqrt{R \delta^3}} ) [14] | Large tips, soft samples with strong adhesion (e.g., hydrogels, many biofilms) [14] | Accounts for adhesion inside the contact area | ( W ): Work of adhesion |

| DMT | ( F = \frac{4}{3} E_{tot} \sqrt{R} \delta^{3/2} - 2 \pi R W ) [15] [14] | Small tips, stiff samples with low adhesion in air [14] | Accounts for adhesion outside the contact area | ( W ): Work of adhesion |

The effective elastic modulus ((E{tot})) is calculated from the Young's modulus (E) and Poisson's ratio (ν) of both the sample (s) and the tip (t) as shown in the equation below [14]: [ \frac{1}{E{tot}} = \frac{3}{4} \left( \frac{1 - \nus^2}{Es} + \frac{1 - \nut^2}{Et} \right) ] For a perfectly rigid indenter, the equation simplifies to ( E{tot} = \frac{4}{3} \frac{Es}{1-\nu_s^2} ) [14].

Experimental Protocols

Cantilever and Tip Preparation

Principle: Accurate calibration of the cantilever's spring constant and deflection sensitivity is fundamental for converting raw photodetector signals into quantitative force values [14].

Procedure:

- Spring Constant Calibration: Use the thermal tune method. Record the power spectral density of the cantilever's free oscillation driven by thermal noise. Apply the equipartition theorem, which states that the mean square deflection is related to the thermal energy, to calculate the spring constant ((k_c)) [14]. Apply necessary corrections for higher oscillation modes if required [14].

- Deflection Sensitivity Calibration: Engage the cantilever on an infinitely hard, non-deformable surface (e.g., clean silicon wafer or sapphire). Acquire a force curve and measure the slope of the contact region in volts. This slope (volts/meter) is the deflection sensitivity, which converts voltage from the photodetector to cantilever deflection in meters [14].

- Tip Characterization: Image the tip apex using electron microscopy (e.g., SEM) before and after experiments to determine the exact tip radius of curvature (R) and to check for wear or contamination that could affect data [14].

Biofilm Sample Preparation

Principle: Reproducible and relevant biofilm growth is critical for obtaining meaningful nanomechanical data. Biofilms must be grown on substrates suitable for AFM analysis.

Procedure:

- Substrate Selection: Use sterile, flat substrates such as glass coverslips, polished silicon wafers, or stainless steel coupons.

- Inoculation: Inoculate the substrate with the bacterial strain of interest (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) in an appropriate growth medium.

- Biofilm Growth: Incubate under controlled conditions (temperature, humidity, time) specific to the organism to allow for biofilm formation. For flow conditions, use a microfluidic platform to mimic natural environments [13].

- Washing: Gently rinse the biofilm with a sterile buffer (e.g., PBS) to remove non-adherent planktonic cells before AFM measurement. Ensure the biofilm remains hydrated at all times.

Force-Volume Imaging and Data Acquisition

Principle: Acquiring force-distance curves on a regular grid (Force-Volume mapping) allows for the spatial mapping of mechanical properties across the biofilm surface [15].

Procedure:

- Mounting: Mount the prepared biofilm sample in the AFM liquid cell and immerse in the appropriate buffer solution.

- Engagement: Engage the calibrated cantilever above the biofilm surface.

- Grid Definition: Define a rectangular grid over the region of interest (e.g., 32x32 or 64x64 points).

- Curve Acquisition: At each pixel, command the piezoelectric actuator to extend (approach) and retract, recording the cantilever deflection (δc) as a function of piezo displacement (Zp). This generates a force-distance curve at every point [15] [14]. Use a sufficient force trigger to ensure contact and a suitable retraction distance to capture adhesion events.

Data Pre-processing and Segmentation

Principle: Raw force-distance data must be processed and segmented to isolate the approach and retract parts for accurate analysis [15].

Procedure:

- Conversion to Real Force-Distance: Convert the independent variable from piezo displacement (Zp) to real probe-sample distance (S) using the relationship ( S = Zp - δc ) to account for cantilever deflection [15] [14].

- Background Subtraction: Use modules like Remove Polynomial Background or Remove Sine Background to subtract unwanted background from the non-contact part of the curve [15].

- Segmentation: Identify and mark the approach (indentation) and retract (withdrawal) segments of each curve. This can be done automatically by the instrument software or manually using segmentation tools (e.g., the "Cut to Segments" module in Gwyddion) [15]. Proper segmentation is critical for subsequent nanomechanical fitting.

Nanomechanical Fitting and Analysis

Principle: Apply the appropriate contact model (Hertz, JKR, or DMT) to the contact portion of the retract curve to extract quantitative mechanical properties.

Procedure:

- Model Selection: Select the contact model based on sample properties:

- Use Hertz for biofilms with negligible adhesion.

- Use JKR for very soft, adhesive biofilms.

- Use DMT for stiffer biofilms with weak, long-range adhesion [14].

- Parameter Input: Enter known parameters including tip radius (R), Poisson's ratio for the sample (νs; often assumed to be 0.5 for hydrated, incompressible biofilms), and cantilever stiffness (kc).

- Automated Fitting: Use a nanomechanical analysis module (e.g., Nanomechanical Fit in Gwyddion) to automatically fit the selected model to the data in every pixel of the force-volume map [15].

- Output Generation: The module will output spatial maps of results, which typically include:

- DMT Modulus: The effective Young's modulus.

- Adhesion Force: The minimum force on the retract curve, indicating pull-off force.

- Deformation: The length of the repulsive part of the approach curve.

- Dissipation Work: The area between the approach and retract curves, representing energy loss [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for AFM-based Biofilm Nanomechanics

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Triangular Si₃N₄ Cantilevers | Low spring constant (e.g., 0.06-0.5 N/m) for sensitive force measurement on soft samples without causing damage [14]. | Nominal spring constant should be verified via thermal calibration [14]. |

| Standard Substrates | Glass coverslips, silicon wafers, stainless steel coupons. Provide a smooth, flat surface for reproducible biofilm growth [13]. | Surface chemistry and roughness can influence initial bacterial attachment and biofilm structure [13]. |

| Growth Media & Buffers | Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB), Luria-Bertani (LB) Broth, Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS). For culturing biofilms and maintaining hydration during AFM imaging. | The specific nutrient composition influences the production of Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) and thus the biofilm's mechanical properties [13]. |

| Microfluidic Flow Cells | Devices that allow for controlled nutrient flow and shear stress during biofilm growth, mimicking in vivo conditions [13]. | Essential for studying the impact of environmental factors on biofilm development and mechanics [13]. |

| Calibration Gratings | Samples with known topography (e.g., TGZ1, TGXY02). Used for verifying the AFM scanner's lateral and vertical calibration. | Regular calibration ensures dimensional accuracy in force-volume maps. |

| Software Tools | Gwyddion, AtomicJ, Nanoscope Analysis, SPIP. Open-source and commercial software for processing, analyzing, and modeling force-distance curves. | Gwyddion offers specific modules for force curve background removal, segmentation, and nanomechanical fitting [15]. |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The application of AFM force-distance curve analysis in biofilm research provides critical insights for designing intervention strategies. It is extensively used for antimicrobial effectiveness testing by quantifying changes in biofilm mechanical properties after treatment [13]. Furthermore, this technique is pivotal in the design of biofilm control strategies, such as evaluating the efficacy of surface coatings or enzymes aimed at disrupting biofilm integrity [13]. The monitoring of biofilm contamination across industrial settings (e.g., food processing lines) is another key application, where AFM can detect subtle changes in mechanical properties that precede visible biofilm formation [13].

Emerging trends point towards the integration of AFM with artificial intelligence. A notable development is a new cyber-physical system using AI-based sensing and physics-aware neural networks to model probe-sample interactions and automate AFM navigation and control. This aims to overcome the current limitation of AFM, which relies on constant human monitoring, thereby expanding its use in biochemical and biomedical sciences [16].

Probing Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) Mechanics

The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix is the fundamental architectural component of microbial biofilms, determining their physicochemical properties and structural integrity. Comprising a complex mixture of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, EPS establishes the three-dimensional framework that encompasses microbial cells and mediates their interactions with the environment [17]. Understanding the nanomechanical properties of EPS—including adhesion, stiffness, and elasticity—is crucial for elucidating biofilm stability, resistance mechanisms, and potential therapeutic targets for biofilm-associated infections.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has emerged as a powerful tool for quantifying the mechanical properties of EPS under physiologically relevant conditions. As a member of the scanning probe microscopy family, AFM operates by sensing surface interactions through a sharp tip mounted on a flexible cantilever, enabling both high-resolution imaging and force measurement capabilities at the nanoscale [1] [2]. This dual capability allows researchers to correlate topographic features with specific mechanical properties, providing unique insights into the structure-function relationships within the EPS matrix that are inaccessible through other analytical techniques.

AFM Fundamentals for EPS Characterization

Operational Principles

AFM measures forces between a sharp probe and the sample surface based on Hooke's law, where cantilever deflection is proportional to the applied force. The core components include a cantilever with a nanoscale tip, a piezoelectric scanner for precise positioning, a laser source, and a photodetector to monitor cantilever motion [1] [2]. For EPS studies, AFM can be configured in multiple operational modes:

- Contact Mode: The tip maintains continuous contact with the sample surface, providing topographic information but potentially inducing sample deformation through lateral forces.

- Tapping Mode: The cantilever oscillates at or near its resonance frequency, making intermittent contact to minimize shear forces and reduce sample damage—particularly advantageous for soft, hydrated EPS samples [2].

- Force Mapping: Multiple force-distance curves are collected across a grid of points, generating spatial maps of mechanical properties alongside topography [18].

Key Mechanical Parameters for EPS

AFM enables the quantification of several critical mechanical properties of EPS:

- Adhesion Force: The attractive force between the AFM tip and EPS components upon retraction, influenced by polymer composition and surface chemistry [19].

- Elastic Modulus: A measure of material stiffness typically derived from indentation experiments using contact mechanics models (e.g., Hertz, Sneddon) [2].

- Deformation: The degree of sample indentation under applied load, reflecting EPS viscoelasticity and structural compliance [2].

Experimental Protocols for EPS Mechanics

Sample Preparation

Proper immobilization of biofilm specimens is essential for reliable AFM analysis. Methods must secure samples against scanning forces while preserving native structure and mechanical properties.

Table 1: Sample Immobilization Methods for AFM Analysis of Biofilms

| Method Type | Specific Approach | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical | Porous membranes (polycarbonate filters) | Retention of hydrated biofilms | May create uneven surfaces |

| Mechanical | PDMS microstructured stamps | Spherical microorganisms | Controlled orientation and positioning [2] |

| Chemical | Poly-L-lysine coated surfaces | General biofilm adhesion | Potential cytotoxicity with prolonged exposure |

| Chemical | Cation-mediated adhesion (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) | EPS-rich biofilms | Enhanced viability preservation [2] |

| Chemical | Glutaraldehyde fixation | Structural preservation | Alters native mechanical properties |

Recommended Protocol: Cation-Mediated Immobilization

- Grow biofilms on fresh agar plates (1.5% w/v) for 24-48 hours under optimal conditions.

- Prepare adhesion-promoting solution containing 10 mM MgCl₂ and 5 mM CaCl₂ in deionized water.

- Apply 100 μL of bacterial suspension (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5) to freshly cleaved mica surfaces.

- After 15 minutes incubation at room temperature, gently rinse with cation solution to remove non-adherent cells.

- Maintain sample hydration in appropriate buffer throughout AFM analysis [2].

AFM Force Spectroscopy

Force spectroscopy enables direct measurement of interaction forces between the AFM tip and EPS components with piconewton sensitivity.

Protocol: Single-Point Force Measurements

- Cantilever Selection: Use silicon nitride cantilevers with spring constants of 0.01-0.1 N/m for soft EPS materials. Calibrate spring constants using thermal tuning methods.

- Approach Parameters: Set approach/retraction velocity to 0.5-1 μm/s with maximum applied force of 0.5-2 nN to minimize sample deformation.

- Data Acquisition: Collect force-distance curves at 512-1024 points per curve with trigger threshold of 1-5 nN.

- Adhesion Analysis: Measure pull-off forces during retraction phase to quantify adhesion between tip and EPS [19] [2].

Protocol: Force Volume Imaging

- Grid Configuration: Define 16×16 to 64×64 measurement grid over region of interest (typically 5×5 μm to 10×10 μm).

- Parameter Consistency: Maintain constant approach velocity and trigger threshold across all measurement points.

- Data Processing: Convert force curves to adhesion and elasticity maps using appropriate contact mechanics models [18].

Nanoindentation for Elastic Modulus

Nanoindentation measures the mechanical resistance of EPS to localized deformation, providing quantitative stiffness data.

Protocol: EPS Elasticity Measurement

- Reference Measurement: Record force curves on rigid reference surface (e.g., clean glass) to define zero indentation point.

- Sample Measurement: Collect force curves on EPS matrix at multiple locations (minimum n=100).

- Data Analysis: Fit approach curves with Hertz model for parabolic tips:

(F = \frac{4}{3} \frac{E}{1-\nu^2} \sqrt{R} \delta^{3/2})

where F is applied force, E is Young's modulus, ν is Poisson's ratio (typically 0.5 for biological samples), R is tip radius, and δ is indentation depth [2].

- Statistical Analysis: Report modulus values as mean ± standard deviation from multiple measurements.

Quantitative Mechanical Properties of EPS

AFM studies have revealed substantial variation in EPS mechanical properties across different bacterial species and environmental conditions.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Mechanical Properties of Bacterial EPS

| Bacterial Species | Measurement Technique | Adhesion Force | Elastic Modulus | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans | Force mapping on pyrite | Not quantified | Heterogeneous distribution | Real living conditions; biofilm vs. planktonic cells [18] |

| Escherichia coli TG1 | Single-cell force spectroscopy on goethite | 97 ± 34 pN (initial)-3.0 ± 0.4 nN (maximum) | Not quantified | Deionized water; 4s contact time [19] |

| Model EPS components | Nanoindentation | Varies by composition | 0.0065 - 2.65 GPa (range for synthetic EPS) | Controlled laboratory conditions [20] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AFM-Based EPS Mechanics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immobilization Substrates | Freshly cleaved mica, Silicon wafers, Polycarbonate filters | Provides flat, uniform surface for biofilm growth and AFM scanning | Surface chemistry affects initial adhesion |

| Adhesion Promoters | Poly-L-lysine, MgCl₂, CaCl₂ | Enhances biofilm attachment to substrates | Cation concentration influences EPS properties |

| Cantilevers | Silicon nitride tips, CSC38 probes (Micromash) | Measures force interactions with EPS | Spring constant calibration critical for quantitation |

| Buffers | Tris-HCl, Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) | Maintains physiological conditions during measurement | Ionic strength affects electrostatic interactions |

| Enzymatic Reagents | Proteases (Savinase, Subtilisin A), Alpha-amylase | Selective degradation of EPS components for mechanistic studies | Enzyme specificity determines EPS target [17] |

| Calibration Standards | Polystyrene beads, Clean glass slides | Verifies instrument performance and tip geometry | Required for quantitative comparisons |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Force Curve Analysis

Interpretation of force-distance curves provides insights into EPS physical properties and interaction mechanisms:

- Approach Phase: Repulsive forces indicate EPS compression, while attractive jumps suggest polymer rearrangement or binding events.

- Contact Region: Slope reflects sample stiffness and elastic modulus.

- Retraction Phase: Adhesion events manifest as negative deflection forces, with multiple unbinding events indicating polymer extensibility [19] [2].

Mapping EPS Heterogeneity

Force mapping reveals spatial variations in mechanical properties within the EPS matrix. Studies on Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans demonstrated heterogeneous accumulation of "slimy and soft EPS" in biofilms on pyrite surfaces, with distinct mechanical properties compared to planktonic cells [18]. This heterogeneity has significant implications for biofilm stability and function.

Correlative Microscopy

Combining AFM with complementary techniques enhances EPS characterization:

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Identifies chemical composition corresponding to mechanical properties (proteins: 1500-1800 cm⁻¹, polysaccharides: 900-1250 cm⁻¹) [17].

- CLSM: Correlates mechanical properties with three-dimensional biofilm structure.

- Electron Microscopy: Provides high-resolution structural context for AFM mechanical data.

Application Notes for Drug Development

The mechanical properties of EPS have significant implications for antimicrobial and antibiofilm drug development:

- Penetration Barriers: EPS elasticity and adhesion create physical barriers that limit antibiotic diffusion into biofilms.

- Mechanical Disruption: Enzymatic treatments targeting specific EPS components (e.g., proteases, amylases) alter matrix mechanics and enhance antimicrobial efficacy [17].

- Synergistic Strategies: Combining EPS-disrupting agents with conventional antibiotics demonstrates improved efficacy against resistant biofilms.

Application Protocol: Evaluating Anti-EPS Compounds

- Grow standardized biofilms in 96-well plates for 24-48 hours.

- Treat with test compounds (enzymes, chelators, antimicrobials) for 4-24 hours.

- Assess mechanical changes via AFM nanoindentation (stiffness) and force spectroscopy (adhesion).

- Correlate mechanical changes with biofilm viability (resazurin assay) and structure (CLSM).

- Identify compounds that disrupt EPS mechanics while enhancing antimicrobial activity.

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Common Experimental Challenges

- Sample Deformation: Excessive imaging forces can compress hydrated EPS, altering measurements. Solution: Use tapping mode with minimal setpoints and validate with force volume.

- Tip Contamination: EPS adhesion to AFM tips causes measurement drift. Solution: Regular cleaning and validation using reference samples.

- Environmental Control: Temperature and humidity fluctuations affect piezoelectric calibration and thermal drift. Solution: Implement environmental isolation and equilibration periods.

Data Validation Methods

- Multiple Tips: Confirm findings with different tip geometries and spring constants.

- Reference Materials: Validate measurements against known standards (polystyrene beads).

- Independent Replicates: Perform experiments across multiple biofilm cultures and growth conditions.

- Comparative Techniques: Correlate AFM data with bulk rheology or other mechanical tests when possible.

AFM-based analysis of EPS mechanics provides crucial insights into biofilm organization, stability, and resistance mechanisms. The protocols outlined herein enable researchers to quantitatively characterize adhesion, elasticity, and mechanical heterogeneity within the EPS matrix under physiologically relevant conditions. As the field advances, correlating these mechanical properties with specific molecular components will facilitate the development of targeted strategies for biofilm control in clinical and industrial settings. The integration of AFM with complementary analytical techniques promises a more comprehensive understanding of structure-function relationships in these complex microbial communities.

Linking Nanomechanical Properties to Biofilm Function and Resilience

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has evolved into a powerful tool for quantifying the nanomechanical properties of biological samples, including living microbial cells and biofilms, under physiological conditions [21] [10]. Biofilms are complex, three-dimensional microbial communities encased in extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and their resilience is a major challenge in healthcare, food industry, and environmental contexts [22] [23] [13]. The mechanical properties of biofilms—such as their viscoelasticity, adhesion strength, and cell cortex stiffness—are critical determinants of their structural integrity, resistance to mechanical and chemical stresses, and overall function [5] [13]. This application note details protocols and analytical frameworks for linking these nanomechanical properties to biofilm function and resilience, providing researchers with methodologies to advance antimicrobial strategies and diagnostic tools.

Key Nanomechanical Properties and Their Functional Significance

The table below summarizes the primary nanomechanical properties that can be probed by AFM and their roles in biofilm physiology.

Table 1: Key Nanomechanical Properties of Biofilms and Their Functional Significance

| Nanomechanical Property | AFM Measurement Technique | Biological Function | Influence on Biofilm Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesive Strength | Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS), Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) [5] [21] | Initial cell attachment to surfaces [5] [24] | Determines resistance to detachment by fluid shear and cleaning forces [5] [13] |

| Viscoelasticity | Force Curve-Based Nanoindentation, Creep Compliance Testing [5] [13] | Maintains structural integrity, controls dispersion [5] | Enhances tolerance to mechanical deformation and modulates antimicrobial penetration [5] [13] |

| Cell Stiffness (Cortical & Whole-Cell) | Nanoindentation with sharp or spherical tips [21] [10] | Indicator of cellular health, metabolic state, and response to environmental stress [10] | Stiffer cells correlate with inflammatory diseases and increased arterial stiffness; softer cells are associated with healthy function [10] |

| Surface Roughness & Morphology | High-Resolution Topographical Imaging [22] [21] | Spatial organization, cell-cell interactions, and microcolony formation [22] | Heterogeneous architecture creates protective niches and gradients that enhance antimicrobial tolerance [22] [23] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Large-Area, High-Resolution Topographical Imaging of Early Biofilms

This protocol is designed to capture the spatial heterogeneity and cellular morphology during the early stages of biofilm formation [22].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Surface Treatment: Use glass coverslips treated with PFOTS (1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorooctyltriethoxysilane) or other relevant coatings to create a hydrophobic surface that promotes specific bacterial adhesion [22].

- Bacterial Strain and Inoculation: Employ Pantoea sp. YR343 or other model organisms (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Inoculate a petri dish containing the treated coverslips with bacteria in liquid growth medium [22].

- Immobilization: For rod-shaped bacteria, use mechanical trapping in porous membranes or electrostatic immobilization on poly-L-lysine-coated substrates to prevent displacement by the AFM tip [21].

- Rinsing and Drying: After a selected incubation period (~30 minutes for initial attachment), remove the coverslip, gently rinse with deionized water to remove unattached cells, and air-dry before imaging [22].

2. AFM Imaging:

- Instrumentation: Use an AFM system capable of large-area automated scanning.

- Scanning Parameters: Operate in tapping mode in air to minimize lateral forces. Use a silicon cantilever with a resonant frequency of approximately 300 kHz and a spring constant of ~40 N/m.

- Automated Large-Area Imaging: Implement a software-controlled stage to capture multiple contiguous high-resolution images (e.g., 50x50 µm) over a millimeter-scale area. Ensure minimal overlap (e.g., 5-10%) between individual scans for efficient stitching [22].

- Data Processing: Apply machine learning-based algorithms to seamlessly stitch individual images and correct for drift and distortions. Use segmentation and classification tools to automatically identify cells, flagella, and quantify parameters like cell count, confluency, and orientation [22].

Protocol: Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) for Adhesion and Viscoelasticity

This protocol provides a standardized method for the absolute quantitation of biofilm adhesion and viscoelastic properties under native conditions [5].

1. Probe and Sample Preparation:

- Cantilever Functionalization: Use rectangular tipless silicon cantilevers (e.g., Mikromasch CSC12/Tipless). Calibrate the spring constant of each cantilever using the thermal method [5].

- Microbead Attachment: Attach a 50 µm diameter glass bead to the tipless cantilever using a small amount of epoxy glue.

- Biofilm Coating: Grow a biofilm directly on the glass bead by incubating it in a concentrated bacterial suspension (e.g., P. aeruginosa PAO1 adjusted to OD600 of 2.0) for a defined period to create "early" (e.g., 24h) or "mature" (e.g., 72h) biofilms [5].

- Substrate: A clean glass surface is used as the interaction substrate.

2. Force Spectroscopy Measurements:

- Standardized Conditions: Conduct measurements in a liquid cell. Standardize the following parameters to enable cross-experiment comparison:

- Loading Pressure: Adjust the trigger force to achieve a defined constant load.

- Contact Time: Hold the bead in contact with the substrate for a fixed duration (e.g., 1 second).

- Retraction Speed: Use a consistent retraction speed (e.g., 1 µm/s) [5].

- Data Collection: Collect a large number of force-distance curves (e.g., 100-500) from different locations on the biofilm-coated bead.

3. Data Analysis:

- Adhesion Quantitation: Calculate the adhesive pressure (Pa) from the retraction curve by dividing the maximum adhesive force by the contact area (calculated using the Hertz model for a sphere) [5].

- Viscoelasticity Quantitation: Fit the creep response data (indentation vs. time during the hold period) to a Voigt Standard Linear Solid model. This yields quantitative parameters including the Instantaneous Elastic Modulus (E₀), Delayed Elastic Modulus (E₁), and Apparent Viscosity (η) [5].

Protocol: Nanomechanical Mapping of Living Cells in Physiological Conditions

This protocol is for measuring the stiffness of the glycocalyx and cortical cell cortex of living endothelial cells, a method directly applicable to microbial cells [10].

1. Cell Preparation:

- Cell Model: Use HUVECs (Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells) freshly isolated or microbial cells like Staphylococcus aureus.

- Immobilization: For cells, use a method that preserves viability, such as a PDMS stamp array or a microfluidic device with V-shaped traps [21].

- Physiological Conditions: Perform all measurements in an appropriate nutrient medium at 37°C to maintain cell viability.

2. Nanoindentation with a Spherical Probe:

- Probe Selection: Use a cantilever with a 1 µm spherical tip to minimize sample damage.

- Force Volume Imaging: Acquire a grid of force curves over the cell surface. Apply a very low loading force (e.g., 0.5 nN) to probe the delicate glycocalyx structure without causing damage [10].

- Enzymatic Control: To quantify the specific contribution of the glycocalyx, repeat measurements after incubating cells with an enzyme like heparinase to enzymatically remove this layer [10].

3. Data Analysis:

- Segmented Analysis: Analyze the force-indentation curves in segments. The initial shallow slope corresponds to the compression of the glycocalyx, while the subsequent steeper slope reports on the stiffness of the cortical cytoskeleton underneath the plasma membrane [10].

- Elastic Modulus Calculation: Fit the appropriate segments of the curve to the Hertz contact model to extract the apparent Young's Modulus (kPa) for the different cellular compartments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AFM Biofilm Nanomechanics

| Item Name | Function/Application | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| PFOTS (Silane) | Surface treatment to create hydrophobic, low-energy surfaces. | Allows for controlled study of how surface properties influence initial bacterial attachment and biofilm assembly [22]. |

| Poly-L-Lysine | Coating substrate to create positively charged surfaces for electrostatic cell immobilization. | Provides a simple and effective method for immobilizing negatively charged microbial cells for high-resolution imaging [21]. |

| Heparinase | Enzyme that specifically degrades heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the glycocalyx. | Serves as a critical tool for functional studies to dissect the mechanical role of the glycocalyx versus the cell cortex [10]. |

| Tipless Cantilevers (CSC12) | Base cantilever for custom probe creation, e.g., for microbead attachment. | Enables the use of Microbead Force Spectroscopy (MBFS) for quantifiable contact area and reproducible adhesion/viscoelasticity measurements [5]. |

| 50 µm Glass Microbeads | Spherical probes for MBFS. | Provide a defined geometry (sphere) for quantitative force measurements and a flexible platform for growing biofilm coatings [5]. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Stamps | Micro-fabricated stamps for creating arrays of physically trapped living cells. | Enables statistically relevant AFM measurements on multiple cells without chemical denaturation, preserving native state [21]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Biofilm Nanomechanics

The following diagram outlines the core experimental pathway for connecting AFM-based measurements to biofilm function and resilience.

Signaling Pathway Linking Cortical Stiffness to Glycocalyx Integrity

This diagram illustrates the hypothesized molecular pathway connecting inflammatory signals to endothelial dysfunction, a key concept in biofilm-associated pathogenesis.

Data Integration and Interpretation

The quantitative data obtained from the above protocols must be integrated to build a comprehensive model of biofilm resilience. For instance, correlating increased cortical cell stiffness (from Protocol 3.3) with enhanced bulk biofilm viscoelasticity (from Protocol 3.2) and specific spatial organization (from Protocol 3.1) provides a multi-scale understanding of how cellular-level changes manifest in community-level properties. This integrated approach is vital for developing targeted interventions, such as designing surface coatings that reduce adhesion or discovering compounds that disrupt the mechanical integrity of the biofilm matrix without promoting antibiotic resistance.

Advanced AFM Methodologies for Biofilm Analysis

Single-Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS) for Initial Adhesion Studies

Single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) has emerged as a powerful biophysical technique that enables the quantitative measurement of cell adhesion forces at the single-cell level under near-physiological conditions [25]. This method, typically implemented using atomic force microscopy (AFM), provides unrivaled spatial and temporal control for studying the initial adhesion events between living cells and various substrates, which is a critical process in biofilm formation, tissue engineering, and host-pathogen interactions [26] [27]. Unlike traditional population-based adhesion assays that yield averaged data, SCFS allows researchers to quantify the adhesion forces, energetics, and kinetics of individual cells, thereby revealing cell-to-cell variability that might be masked in ensemble measurements [28] [25]. The capability to probe adhesion at the single-cell level has proven particularly valuable in microbial research, where understanding the initial attachment of bacteria to surfaces is fundamental to combating biofilm-associated infections and developing novel antifouling strategies [28] [29]. As antimicrobial resistance continues to challenge healthcare systems worldwide, SCFS provides a sophisticated analytical platform for investigating how microbial surface properties and adhesive behaviors contribute to virulence and resistance mechanisms [29].

Principles and Applications of SCFS

Fundamental Principles of SCFS

SCFS operates on the principle of directly measuring the interaction forces between a single cell immobilized on an AFM cantilever and a target substrate. The fundamental mechanics are governed by Hooke's law (F = k × d), where the force (F) is calculated from the cantilever's spring constant (k) and its vertical deflection (d) [29]. During a typical SCFS experiment, the cell-functionalized cantilever approaches the substrate, makes contact for a defined period to allow adhesion formation, and then retracts while recording the force required to detach the cell [25]. The resulting force-distance curves provide rich information about the adhesion strength, including the maximum detachment force, the work of detachment (calculated as the area under the retraction curve), and the nature of the binding events, such as the presence of specific receptor-ligand interactions or the formation of membrane tethers [28] [29]. Advanced implementations like the fluidic force microscope (FluidFM) combine traditional AFM with microfluidic pressure control and hollow cantilevers, significantly improving throughput and reliability by enabling precise immobilization and release of individual cells without chemical fixation [28].

Key Applications in Biofilm and Antimicrobial Research

SCFS has become an indispensable tool in biofilm mechanics and antimicrobial research, particularly for investigating the initial adhesion events that precede biofilm formation. Recent research has utilized SCFS to study the interaction between Escherichia coli and antifouling surfaces, revealing that coatings such as the tripeptide DOPA-Phe(4F)-Phe(4F)-OMe and poly(ethylene glycol) polymer-brush can significantly reduce bacterial adhesion forces compared to bare glass surfaces [28]. By employing mutant strains deficient in specific adhesive appendages, researchers have been able to decipher the distinct mechanisms by which bacteria adhere to different surfaces, demonstrating that E. coli utilizes separate molecular mechanisms for initial attachment to different antifouling coatings [28]. Beyond microbial studies, SCFS has been widely applied to investigate mammalian cell adhesion in various contexts, including renal tubular injury [30], fibroblast adhesion to microstructured titanium implants [31], and the mechanobiology of circulating tumor cells [32]. The technique's versatility allows for the quantification of both specific receptor-ligand interactions and nonspecific cell adhesion, providing comprehensive insights into the biophysical determinants of cellular attachment in health and disease.

SCFS Experimental Protocol for Microbial Adhesion Studies

Sample Preparation and Surface Functionalization

Proper sample preparation is crucial for obtaining reliable SCFS data. For studying microbial adhesion to antifouling surfaces, substrates must be carefully prepared and characterized before adhesion measurements. The protocol for creating antifouling surfaces involves coating clean glass coverslips with either the tripeptide DOPA-Phe(4F)-Phe(4F)-OMe or poly(L-lysine) grafted with poly(ethylene glycol) (PLL-g-PEG) [28]. Surface characterization through water contact angle measurements and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy should be performed to verify successful coating deposition. The AFP surface typically shows increased hydrophobicity, while PLL-g-PEG coatings demonstrate moderate increases in contact angle compared to bare glass [28]. For mammalian cell studies, surfaces may be functionalized with extracellular matrix proteins like collagen or fibronectin using covalent immobilization techniques to create well-defined adhesion substrates [27]. All surfaces should be sterilized before cell adhesion experiments, and for biological relevance, they may be pre-incubated with serum-containing media to allow adsorption of extracellular matrix proteins that mimic in vivo conditions [31].

Cell Probe Preparation and Immobilization

The preparation of single-cell probes requires careful attention to maintain cell viability and function throughout the experiment. For bacterial studies, cultures should be grown under appropriate conditions to express the adhesion factors of interest. For example, when studying E. coli adhesion, bacteria should be cultivated under conditions that promote the expression of type-1 fimbriae and curli amyloid fibers, which are known to mediate attachment to surfaces [28]. The FluidFM platform has significantly improved the cell immobilization process by using hollow cantilevers connected to a pressure controller. A single cell is immobilized by positioning the cantilever above the cell, approaching while applying negative pressure (approximately -300 to -600 mbar) to aspirate and secure the cell onto the tip aperture [28]. The successful immobilization should be verified microscopically, often using fluorescence staining techniques such as SYTO 9 to confirm the presence and viability of the captured cell [28]. For traditional AFM systems without microfluidic capabilities, cells may be immobilized using chemical fixatives or biocompatible adhesives like concanavalin A or poly-DOPA, though these methods may potentially affect cell function and should be carefully validated [29].

Force Spectroscopy Measurements and Data Acquisition

Once a single-cell probe is prepared, force spectroscopy measurements are conducted by programming the AFM to perform approach-contact-retract cycles at multiple locations on the substrate surface. The typical parameters for bacterial adhesion studies include an approach force of 100-500 pN, contact times ranging from 0.1 to 60 seconds, and retraction speeds of 1-10 μm/s [28] [33]. Each measurement should include a sufficient dwell time (typically 0.1-2 seconds) when the cell is in contact with the surface to allow adhesion formation [28]. For each experimental condition, a minimum of 50-100 force curves should be collected from at least 3-5 different cells to account for cell-to-cell variability [28] [33]. It is essential to include control measurements using bare cantilevers without cells to subtract any nonspecific interactions between the tip and substrate. All experiments should be conducted in physiological buffer solutions at controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C for human pathogens) to maintain relevant biological conditions [33]. When studying the adhesion kinetics, the contact time can be systematically varied to determine the time dependence of adhesion strength, which often follows exponential kinetics as described by C₁[1 - exp(-C₂·t)] [31].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The analysis of SCFS data involves processing force-distance curves to extract quantitative parameters that describe the adhesion properties. Key parameters include the maximum adhesion force (the highest force recorded during retraction), the work of detachment (calculated as the area under the retraction curve), and the rupture length (the distance at which final detachment occurs) [28]. For bacterial adhesion studies on antifouling surfaces, typical maximum adhesion forces for E. coli to bare glass are approximately 910 ± 30 pN, while significantly reduced forces of 160 ± 20 pN and 10 ± 2 pN are observed for AFP and PLL-g-PEG coatings, respectively [28]. The detachment work follows similar trends, with values of 660 ± 30 eV for glass, 46 ± 7 eV for AFP, and 3 ± 1 eV for PLL-g-PEG [28]. Advanced analysis may include assessing the presence of multiple rupture events or force plateaus, which often indicate the sequential breaking of individual bonds or the extraction of membrane tethers [28]. Statistical analysis should account for the inherent heterogeneity in cell populations, and results are typically presented as mean ± standard error with significance testing between conditions using appropriate statistical tests such as Student's t-test or ANOVA [28] [33].

Quantitative Data Presentation

Adhesion Force Measurements on Different Surfaces

Table 1: Comparison of E. coli adhesion forces on different surfaces measured by SCFS

| Surface Type | Maximum Adhesion Force (pN) | Detachment Work (eV) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bare Glass | 910 ± 30 | 660 ± 30 | Multiple detachment events, force plateaus indicating membrane tethering and pili extension |

| AFP Coating | 160 ± 20 | 46 ± 7 | Significant reduction in adhesion events, minimal force plateaus |

| PLL-g-PEG | 10 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | Majority of curves show no detectable adhesion, near-complete antifouling |

Data obtained from [28]

Technical Specifications for SCFS Experiments

Table 2: Typical parameters for SCFS experiments in microbial adhesion studies

| Parameter | Typical Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Approach Force | 100-500 pN | Higher forces may activate mechanosensitive responses |

| Contact Time | 0.1-60 seconds | Varies based on adhesion kinetics of interest |

| Retraction Speed | 1-10 μm/s | Affects measured detachment forces |

| Number of Curves | 50-100 per condition | Required for statistical significance |

| Number of Cells | 3-5 per condition | Accounts for cell-to-cell variability |

| Temperature | 37°C (for human pathogens) | Maintains physiological relevance |

| Immobilization Pressure | -300 to -600 mbar | For FluidFM systems only |

Visualization of SCFS Workflow and Mechanisms

Experimental Workflow Diagram

Figure 1: SCFS Experimental Workflow. The diagram illustrates the sequential steps in a typical SCFS experiment using FluidFM technology, from cell immobilization through force measurement and data analysis.

Bacterial Adhesion Mechanisms on Antifouling Surfaces

Figure 2: Mechanisms of Bacterial Adhesion to Different Surfaces. The diagram illustrates how E. coli utilizes different adhesive appendages to interact with various surfaces, resulting in distinct adhesion force profiles.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for SCFS experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| AFM Platform | Core instrumentation for force measurements | Nanowizard II (JPK), FluidFM systems |

| Cantilevers | Force sensors for adhesion measurements | Hollow cantilevers (FluidFM), tipless cantilevers for cell attachment |

| Cell Lines | Model organisms for adhesion studies | E. coli ATCC 25922 (wild-type), mutant strains deficient in fimbriae or curli expression |

| Antifouling Coatings | Surface modifications to prevent adhesion | DOPA-Phe(4F)-Phe(4F)-OMe (AFP), PLL-g-PEG |

| Immobilization Reagents | Cell attachment to cantilevers | Poly-L-lysine, concanavalin A, polydopamine (for traditional AFM) |

| Surface Materials | Substrates for adhesion measurements | Glass coverslips, titanium microstructures, functionalized gold surfaces |

| Characterization Tools | Surface property verification | Contact angle goniometers, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

Information compiled from multiple sources [28] [29] [31]

Novel FluidFM Technology for Biofilm-Scale Adhesion Measurements

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has long been a cornerstone technique in biofilm nanomechanics research, enabling the quantification of adhesion forces at piconewton resolution. However, conventional single-cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) approaches face a significant limitation: they probe interactions only between individual planktonic cells and surfaces, which fails to represent realistic conditions where bacteria predominantly exist in structured biofilm communities. The introduction of Fluidic Force Microscopy (FluidFM) technology addresses this methodological gap by combining AFM with microfluidics, allowing researchers to measure adhesion forces at the biofilm scale for the first time. This Application Note details protocols for implementing FluidFM in biofilm mechanics research, providing researchers with robust methodologies to obtain more physiologically relevant adhesion data.

FluidFM technology integrates a hollow microchannel cantilever connected to a pressure controller, functioning as a force-controlled nanopipette. This system enables reversible immobilization of biological samples—from single cells to biofilm-coated beads—through applied underpressure [34] [35]. Unlike chemical fixation methods that can alter surface properties, FluidFM provides physical immobilization without chemical modification, preserving native biofilm characteristics during adhesion measurements [36] [37].

FluidFM technology centers on microchanneled cantilevers with nanoscale apertures, merging the spatial precision of atomic force microscopy with the fluidic capabilities of a nanopipette. The core system consists of three integrated components:

Hollow FluidFM Cantilevers: These specialized probes feature a microfluidic channel running through the cantilever to an aperture at its tip. Available in several configurations, these cantilevers are selected based on specific experimental requirements (Table 1).

Pressure Control System: A precision pump generates controlled over- or under-pressure within the fluidic channel, enabling aspiration or dispensing of femtoliter volumes.

AFM Platform with Optical Integration: A conventional atomic force microscope equipped with FluidFM compatibility, integrated with an inverted optical microscope for real-time visualization and precise positioning of probes relative to samples [34] [35].

Table 1: FluidFM Probe Types and Their Applications in Biofilm Research

| Probe Type | Aperture Size | Tip Characteristics | Primary Applications in Biofilm Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micropipette | 2, 4, or 8 µm | Tipless | Reversible immobilization of single cells and biofilm-coated beads for adhesion measurements [35]. |

| Nanopipette | 300 nm | Tip apex aperture | Localized dispensing of anti-biofouling agents; single-bacterium adhesion studies [34] [35]. |

| Nanosyringe | 300 nm | Sharp apex, side aperture | Penetration of biofilm matrix for injection/extraction; intra-biofilm delivery of compounds [34] [35]. |

The operational principle involves filling the hollow cantilever with fluid and connecting it to the pressure controller. By applying relative underpressure, researchers can reversibly immobilize individual cells or biofilm-coated microbeads on the cantilever aperture for force spectroscopy experiments. This physical immobilization method demonstrates particular advantage for studying bacterial strains that prove difficult to immobilize using chemical adhesives like polydopamine or poly-L-lysine [36] [37].

Application Protocol: Biofilm-Scale Adhesion Force Measurement

This protocol details the novel methodology for measuring adhesion forces between intact biofilms and surfaces using FluidFM technology, as recently demonstrated in studies evaluating anti-biofouling filtration membranes [38] [39].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for FluidFM Biofilm Adhesion Experiments

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| FluidFM System | Compatible AFM with FluidFM add-on, pressure controller, inverted optical microscope | Core instrumentation for force measurements and sample manipulation [34]. |

| FluidFM Cantilevers | Hollow micropipettes (2-8 µm aperture) | Aspiration of biofilm-coated beads and adhesion force detection [35]. |

| Polystyrene Beads | COOH-functionalized, 1 µm diameter (e.g., Polybead Microspheres) | Biofilm growth substrate and probe for force spectroscopy [38]. |

| Bacterial Strains | Gram-negative Pseudomonas aeruginosa (or other relevant strains) | Model organism for biofilm formation [39]. |

| Growth Media | Appropriate liquid medium for selected bacterial strain (e.g., LB for E. coli) | Biofilm cultivation and maintenance. |

| Membrane Surfaces | Polyethersulfone (PES) filtration membranes, vanillin-modified | Substrates for adhesion force quantification [38]. |

| Buffer Solution | 0.9% NaCl solution or phosphate buffered saline (PBS) | Measurement fluid environment. |

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for FluidFM biofilm-scale adhesion measurements:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for FluidFM biofilm adhesion measurement

Step-by-Step Procedure

Biofilm-Coated Bead Preparation

Bead Functionalization: Incubate 1 µm COOH-functionalized polystyrene beads with bacterial suspension of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in appropriate growth medium. COOH-functionalized surfaces have demonstrated superior bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation compared to other surface chemistries [38].

Biofilm Growth: Allow biofilms to develop on bead surfaces for 3 hours at optimal growth temperature (e.g., 37°C for P. aeruginosa). This timeframe has been shown to produce consistent biofilm coverage suitable for adhesion measurements [38].

FluidFM System Setup

Cantilever Preparation: Select a hollow FluidFM micropipette with 4-8 µm aperture. Fill the cantilever reservoir with appropriate fluid (glycerol or measurement buffer) using a micropipette. Connect the probe to the pressure controller system.

System Calibration: Calibrate the cantilever using the contact-based thermal noise method in measurement buffer (0.9% NaCl solution). Record the spring constant, typically ranging between 0.28-0.52 N/m for bacterial adhesion studies [36].

Bead Immobilization and Measurement

Bead Aspiration: Place a droplet of the biofilm-bead suspension on a glass slide. Position the FluidFM cantilever above a single biofilm-coated bead using optical microscopy guidance. Apply -800 mbar relative underpressure to aspirate and immobilize the bead on the cantilever aperture [36] [37].

Pressure Adjustment: Reduce immobilization pressure to lower values (-50 to -200 mbar) for subsequent adhesion measurements to maintain secure bead attachment while minimizing experimental artifacts [36].

Transfer to Sample Surface: Navigate the immobilized biofilm-bead probe to the target surface (e.g., vanillin-modified PES membrane) in measurement buffer.

Force Spectroscopy Measurements

Parameter Setup: Configure force spectroscopy parameters established for biofilm-scale measurements:

Data Collection: Execute approach-retract cycles at multiple surface locations (minimum 3 different beads, 25-50 force curves per bead). Include control measurements with unmodified surfaces for comparison.

Data Analysis

Curve Validation: Discard force-distance curves that are incomplete, show unstable baselines, or lack distinguishable adhesion peaks.

Adhesion Quantification: Calculate the maximum adhesion force from the retraction curve, defined as the largest force relative to the baseline. Determine adhesion work by integrating the area under the retraction curve.

Statistical Analysis: Compare adhesion forces and adhesion work between experimental and control surfaces using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-test for normally distributed data).

Key Experimental Parameters and Optimization

Successful implementation of FluidFM biofilm adhesion measurements requires careful optimization of key parameters to ensure data quality and physiological relevance:

Table 3: Optimized Measurement Parameters for FluidFM Biofilm Adhesion Studies

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Impact on Measurements | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setpoint | 2-5 nN | Higher setpoints increase contact force, potentially influencing adhesion values. | Use the minimum setpoint that establishes reliable contact [36]. |

| Z-Speed | 2-5 µm/s | Affects loading rate and measured adhesion forces; higher speeds may increase observed adhesion. | Maintain consistent speed within experiments for comparability [36]. |

| Z-Length | 0.5-2 µm | Must be sufficient to achieve complete separation after adhesion events. | Ensure full retraction to baseline; increase if adhesion events are truncated [37]. |

| Pause Time | 0-2 s | Longer pause times may increase adhesion through longer contact duration. | Standardize pause time across comparative experiments [37]. |

| Immobilization Pressure | -50 to -200 mbar | Maintains bead attachment during measurements without excessive force. | Reduce from initial -800 mbar aspiration pressure for measurements [36]. |

Representative Data and Expected Outcomes

Application of this protocol to evaluate anti-biofouling membrane surfaces typically yields the following outcomes:

Adhesion Force Reduction: Vanillin-modified PES membranes demonstrate significantly reduced adhesion forces (40-60% decrease) compared to unmodified membranes [38] [39].

Binding Event Frequency: Modified surfaces typically show fewer adhesion events in force-distance curves, indicating reduced binding affinity [38].

Adhesion Work: The total work of adhesion decreases substantially on anti-biofouling surfaces, reflecting easier biofilm detachment [38].