qPCR vs. ddPCR for Absolute Bacterial Quantification: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for the absolute quantification of bacteria in complex samples.

qPCR vs. ddPCR for Absolute Bacterial Quantification: A Strategic Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for the absolute quantification of bacteria in complex samples. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological workflows, and optimization strategies. Drawing on recent comparative studies, including applications in microbiome research and clinical trial analysis, the content delivers evidence-based guidance for selecting the optimal technology based on sensitivity, precision, cost, and throughput requirements for accurate bacterial load assessment.

Understanding qPCR and ddPCR: Core Principles for Bacterial Quantification

The advent of quantitative PCR (qPCR) marked a revolutionary shift in molecular biology, transforming polymerase chain reaction from a qualitative tool to a powerful quantitative technique. This evolution has fundamentally accelerated discovery in biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and microbiology. More recently, the emergence of digital PCR (dPCR) represents another paradigm shift, offering absolute quantification of nucleic acids without requiring standard curves. Within bacterial quantification research—particularly for absolute quantification of specific species or strains in complex matrices like the gut microbiome, environmental samples, or clinical specimens—the choice between qPCR and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) has significant implications for data accuracy, sensitivity, and translational impact. This guide objectively compares the performance of these technologies, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers in their experimental design.

Technological Fundamentals: From Quantitative to Digital PCR

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

qPCR, also known as real-time PCR, enables the monitoring of DNA amplification as it occurs through the detection of fluorescent signals. The core principle relies on the Quantification Cycle (Cq), the point at which fluorescence crosses a threshold above background. The Cq value is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid. Quantification requires constructing a standard curve from samples with known concentrations, allowing the interpolation of unknown samples [1] [2]. While this approach is robust, it is relative by nature, and its accuracy depends entirely on the quality and accuracy of the standard curve.

Digital PCR (dPCR)

dPCR takes a fundamentally different approach to quantification. The reaction mixture is partitioned into thousands to millions of individual nanoliter-scale reactions. According to Poisson statistics, some partitions will contain zero target molecules, while others will contain one or more. Following end-point PCR amplification, partitions are analyzed as positive or negative for fluorescence [3] [1]. The absolute concentration of the target in the original sample is then calculated directly from the ratio of positive to total partitions, without the need for a standard curve [4] [5]. This core difference underpins the key advantages of dPCR for absolute quantification.

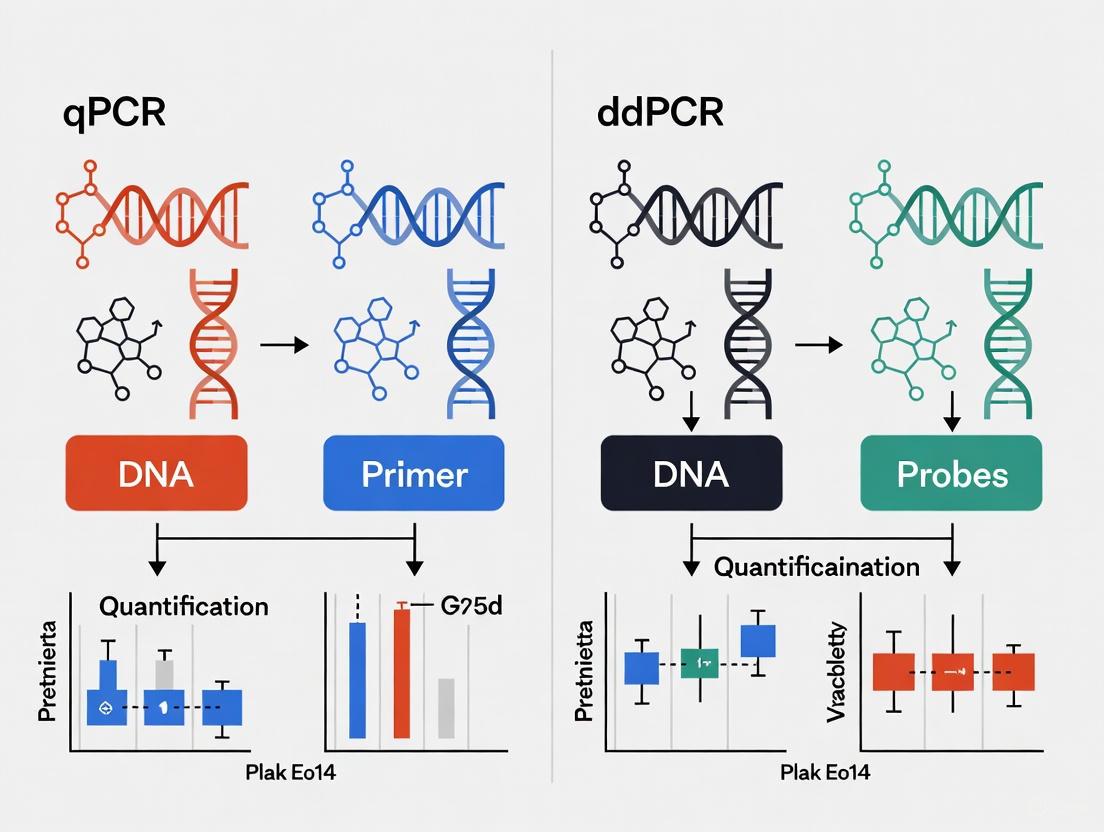

Visualizing the Core Workflows

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between qPCR and ddPCR workflows.

Performance Comparison for Bacterial Quantification

Extensive studies have directly compared qPCR and ddPCR for quantifying bacterial targets across various sample types, from clinical isolates to complex microbiome samples. The data reveal a nuanced picture where each technology excels in different scenarios.

Table 1: Technical and Operational Comparison of qPCR and ddPCR

| Feature | qPCR | ddPCR | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Principle | Relative (via Cq & standard curve) | Absolute (via Poisson statistics of partitions) | [6] [1] [5] |

| Precision | Good (++), requires replicates for high precision | Excellent (+++), higher resolution & lower CV | [1] [5] |

| Sensitivity (LOD) | ~103 - 104 cells/g feces | Often 10-100x higher than qPCR; ~103 cells/g feces | [7] [5] [8] |

| Dynamic Range | Wider (≥ 5 logs) | Limited by number of partitions | [1] [5] |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | Moderate | High; partitioning dilutes inhibitors | [3] [5] |

| Throughput & Speed | High throughput, faster run time | Lower throughput, involves partitioning step | [7] [1] |

| Multiplexing Capability | + | +++ | [1] |

| Cost Consideration | Lower instrument cost, requires standards | Higher instrument cost, no standard curves | [7] [1] |

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Bacterial Detection Studies

| Pathogen / Sample Type | qPCR Performance | ddPCR Performance | Key Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limosilactobacillus reuteri(Spiked fecal samples) | LOD: ~10⁴ cells/gGood reproducibility | Slightly better reproducibilityComparable LOD & linearity | qPCR is advantageous due to wider dynamic range, lower cost, and speed. | [7] |

| Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri(Plant pathogen) | Broader dynamic range | Significantly higher sensitivityLower CV, especially at low concentrations | ddPCR more robust for diagnosis; higher resilience to inhibitors. | [5] |

| Listeria monocytogenes,Francisella tularensis, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis(Water suspensions) | Over-/under-estimated bacterial load vs. dPCR (<0.5 Log10) | Accurate quantification vs. cultural methods | dPCR quantified the same amount of bacteria as cultural methods for L. monocytogenes. | [6] |

| Staphylococcus aureus(Skin-derived DNA, low biomass) | Lower detection efficiency in low-DNA yield samples | High sensitivity and precise quantification in unstable samples | ddPCR is promising for specific microbe detection in challenging samples. | [8] |

| Prokaryotes in Stool(16S rRNA gene quantification) | Reliable quantification | Reliable quantification | Both qPCR and ddPCR are valid for absolute 16S rRNA quantification in stool. | [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Bacterial Quantification

The following methodologies are adapted from key studies that successfully implemented qPCR and ddPCR for absolute bacterial quantification.

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for designing strain-specific assays and quantifying bacteria in complex fecal samples.

1. Strain-Specific Primer Design:

- Starting Point: Obtain complete genome sequences for the target bacterial strain and closely related strains.

- Identification of Unique Markers: Use comparative genomics software to identify genes unique to the target strain.

- Primer Design: Design primers with a melting temperature (Tm) of ~60°C, length of 18-22 bp, and GC content of 40-60%. Verify specificity in silico using BLAST against genomic databases.

2. Bacterial Culture and Sample Spiking:

- Grow the target strain (e.g., L. reuteri) in appropriate broth to the late exponential phase.

- Harvest cells and resuspend in PBS. Determine cell density by quantitative plating on agar plates.

- Spike known quantities of bacteria (e.g., serial dilutions from 10⁷ to 10³ cells/g) into L. reuteri-negative human fecal samples for standard curve generation.

3. DNA Extraction:

- Use a kit-based DNA isolation method (e.g., QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit) for optimal yield and purity from ~0.1 g of spiked fecal sample. Include a washing step with ice-cold PBS to reduce PCR inhibitors.

4. qPCR Setup and Execution:

- Reaction Mix: 2x TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, forward and reverse primers (300 nM each), TaqMan probe (150 nM), and template DNA.

- Cycling Conditions: 50°C for 2 min; 95°C for 10 min; 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min.

- Quantification: Include a standard curve of genomic DNA with known concentration (log dilutions) in each run. Convert Cq values to absolute cell counts using the standard curve and genome size.

This protocol outlines the transfer of an established qPCR assay to a ddPCR format for absolute quantification.

1. Assay Transfer:

- Use the same primers and probe from a validated qPCR assay. This ensures specificity and facilitates direct comparison between the two technologies.

2. ddPCR Reaction Assembly:

- Reaction Mix: Combine 10 μL of 2x ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP), primers and probe at the same concentrations as in qPCR, and 5 μL of template DNA. Adjust with nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 μL.

3. Droplet Generation:

- Load the 20 μL reaction mix and 70 μL of droplet generation oil into a DG8 cartridge.

- Place the cartridge in the droplet generator. This instrument partitions the sample into ~20,000 nanoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets.

4. PCR Amplification:

- Carefully transfer the emulsion of droplets to a 96-well PCR plate.

- Seal the plate and run on a thermal cycler with the following profile: 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 1 min (use a slow ramp rate of 2°C/sec); and a final 98°C hold for 10 min for enzyme deactivation.

5. Droplet Reading and Analysis:

- Place the PCR plate in the droplet reader, which aspirates droplets from each well.

- The reader counts the total number of droplets and identifies positive (fluorescent) and negative (non-fluorescent) droplets using a binary threshold.

- The concentration (copies/μL) is calculated automatically by the instrument's software based on Poisson statistics: ( \lambda = -\ln(1 - p) ), where ( p ) is the fraction of positive droplets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR-Based Bacterial Quantification

| Item | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Kit-based DNA Isolation Kits | Efficiently extract high-purity DNA while removing PCR inhibitors from complex samples like feces, soil, or tissue. | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit for human fecal samples [7]. |

| TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix | A ready-to-use mix containing Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer. Essential for robust and reproducible qPCR/ddPCR. | Used in both qPCR and ddPCR protocols for detecting L. reuteri and X. citri [7] [5]. |

| ddPCR Supermix for Probes | A specialized master mix formulated for the generation of stable droplets and efficient amplification in droplet-based dPCR. | Bio-Rad's ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP) is used in standard ddPCR workflows [5]. |

| Strain-Specific Primers & Probes | Oligonucleotides designed to bind to unique genomic regions of a target bacterial strain, enabling specific detection and quantification. | Primers for L. reuteri 17938 or S. aureus greA gene for specific identification in a mixed microbial background [7] [8]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | A critical reagent for preparing reaction mixes, ensuring no enzymatic degradation of primers, probes, or template DNA. | Used in all PCR reaction setups to achieve precise volume and avoid contamination. |

| Droplet Generation Oil | An oil formulation used to create the water-in-oil emulsion necessary for partitioning the sample in ddPCR. | Bio-Rad's Droplet Generation Oil for QX200/QX100 systems [3]. |

Application Contexts: Choosing the Right Tool

The choice between qPCR and ddPCR is not one of superiority but of appropriateness for the specific research question and context.

Choose qPCR when:

- Your project involves screening a large number of samples where high throughput and speed are critical [7] [1].

- The target bacterial concentration is expected to be high and within a wide dynamic range.

- The budget is a primary constraint, and instrument cost is a significant factor [1].

- Well-characterized and reliable standard curves are available.

Choose ddPCR when:

- Absolute quantification without standard curves is required for cross-laboratory reproducibility [6] [5].

- Detecting and quantifying low-abundance targets (e.g., rare pathogens or specific strains in a dense microbiome) is the goal [1] [8].

- The sample contains PCR inhibitors that often plague complex matrices like soil, feces, or clinical specimens [3] [5].

- The application requires high precision for detecting small fold-changes, such as in copy number variation or rare mutation detection [1].

The evolution from qPCR to dPCR technology has provided the scientific community with a more diverse and powerful toolkit for absolute bacterial quantification. While qPCR remains the workhorse for high-throughput, relative quantification, ddPCR has carved out a critical niche where absolute precision, sensitivity, and resilience to inhibitors are paramount. The experimental data clearly show that for applications like quantifying specific bacterial strains in complex environments (e.g., the gut microbiome), tracking low-abundance pathogens in clinical samples, or requiring high inter-laboratory reproducibility, ddPCR offers significant advantages. However, for broader dynamic range and higher throughput at a lower cost, qPCR remains highly effective. The decision, therefore, rests on a careful consideration of the specific research objectives, sample type, and operational constraints. As both technologies continue to advance, their complementary strengths will undoubtedly continue to drive innovation in microbial research and diagnostic development.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) is a cornerstone technique in molecular biology, enabling researchers to quantify specific DNA sequences in real-time during amplification. For many applications in bacterial quantification, researchers employ relative quantification, a method that determines the amount of a target gene relative to a reference sample or control gene. This approach is particularly valuable when studying gene expression changes or microbial population shifts under different experimental conditions. Unlike absolute quantification, which calculates the exact copy number of a target sequence, relative quantification expresses results as fold-changes, making it ideal for comparative studies where the question is "how much more or less of this target exists in my treated sample compared to my control?" The foundation of this method lies in properly constructing and utilizing a standard curve, which serves as the benchmark for determining relative quantities across samples.

The Principle of Relative Quantification

Relative quantification in qPCR measures changes in gene expression or DNA target quantity relative to an appropriate reference point. This reference can be either a calibrator sample (such as an untreated control) or a stable endogenous control gene (often called a housekeeping gene) that maintains constant expression across different experimental conditions. The core principle involves comparing the quantification cycle (Cq) values of your target gene to those of the reference gene to normalize for variations in sample concentration and loading errors.

There are two primary calculation methods for relative quantification. The standard curve method involves creating dilution series of a reference sample to generate a curve that relates Cq values to relative quantities. For all experimental samples, you determine the target quantity from this standard curve and then divide by the target quantity of the calibrator, expressing all quantities as an n-fold difference relative to this calibrator. The comparative Cq method (2^(-ΔΔCq)) uses a mathematical approach to calculate fold-changes without a standard curve, but requires the amplification efficiencies of the target and reference genes to be approximately equal and close to 100%.

A significant advantage of relative quantification is that because the sample quantity is divided by the calibrator quantity, the measurement units cancel out, meaning any stock DNA or RNA containing the appropriate target can be used to prepare standards, provided their relative dilutions are known [10].

The Role of the Standard Curve

The standard curve is fundamental to relative quantification in qPCR, serving as the reference point for determining quantities in unknown samples. This curve is created by performing qPCR on a series of dilutions from a known reference sample, typically spanning several orders of magnitude (e.g., 10-fold serial dilutions). The Cq values obtained from these dilutions are plotted against the logarithm of their relative concentrations to generate a linear standard curve.

Creating and Validating a Standard Curve

To create a standard curve for relative quantification, researchers typically use a five-point serial dilution of a sample of known concentration, such as purified genomic DNA or input DNA from your experimental system. Each dilution is amplified in at least three replicates to ensure statistical reliability. The resulting Cq values are plotted against the logarithmic values of the known relative concentrations (e.g., dilution factors of 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125) to generate the standard curve [11].

The efficiency (E) of the qPCR reaction is critically important and is calculated from the standard curve using the formula: Efficiency (E) = 10^(-1/slope) % Efficiency = (E-1) × 100 For a properly optimized reaction, the efficiency should fall between 95% and 105% [11]. Efficiency outside this range may indicate issues with primer design, reaction inhibitors, or suboptimal reaction conditions that require troubleshooting.

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for relative quantification using the standard curve method:

Key Experimental Protocols

Standard Curve Establishment Protocol

Reference Sample Preparation: Select an appropriate reference sample containing your target sequence. This could be a pooled sample from your experiment, purified DNA, or a synthetic oligonucleotide. For gene expression studies using RNA, first reverse transcribe to cDNA using a high-efficiency reverse transcription kit [11].

Serial Dilution Series: Create a minimum of five serial dilutions (typically 1:5 or 1:10 dilutions) of your reference sample in the same buffer as your unknown samples. Use low-binding tubes and precise pipetting techniques to ensure accuracy, as dilution errors significantly impact standard curve reliability [10].

qPCR Setup: Run all standard dilutions and unknown samples on the same qPCR plate to eliminate inter-plate variability. Include at least three technical replicates for each standard point and unknown sample. Use a reaction volume appropriate for your system (typically 10-25 µL) containing your master mix, primers, and optionally, probes for specific detection [11].

Data Collection and Analysis: Run the qPCR program with appropriate cycling conditions for your assay. After completion, review amplification curves to ensure they exhibit characteristic exponential amplification phases. The qPCR instrumentation software will typically automatically calculate Cq values and generate the standard curve [11].

Efficiency Calculation and Troubleshooting

To calculate efficiency from your standard curve:

- Obtain the slope value from the linear regression of your standard curve plot.

- Apply the formula: Efficiency = 10^(-1/slope)

- Convert to percentage: % Efficiency = (Efficiency - 1) × 100

If your efficiency falls outside the ideal 95-105% range, consider these troubleshooting steps:

- Verify primer design: Ensure amplicon size is between 65-150 bases and primers are specific without forming dimers.

- Check template quality: Assess for contamination from phenol, salts, or ethanol in template DNA.

- Optimize reagent concentrations: Adjust primer concentrations and ensure fresh reagents are used.

- Validate instrument settings: Confirm appropriate baseline and threshold settings in your qPCR instrument software [11].

qPCR vs. ddPCR: A Comparative Analysis for Bacterial Quantification

While qPCR with relative quantification serves many research needs effectively, Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) has emerged as a complementary technology with distinct advantages for certain applications, particularly in absolute quantification of bacterial targets. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics based on comparative studies:

Table 1: Comparison of qPCR and ddPCR Performance Characteristics for Bacterial Quantification

| Parameter | qPCR with Relative Quantification | ddPCR | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Approach | Relative to standard curve or reference gene | Absolute counting without standard curves | ddPCR eliminates need for reference standards [10] |

| Dynamic Range | Broad dynamic range [5] | Limited at high target concentrations (>10⁶ CFU/mL) [12] | qPCR better for high-abundance bacterial targets |

| Sensitivity | Good sensitivity (LOD ~10⁴ cells/g feces) [7] | Excellent sensitivity (10-fold lower LOD than qPCR) [12] | ddPCR superior for rare targets and low-biomass samples |

| Precision & Reproducibility | Good reproducibility with proper optimization [7] | Superior precision, especially for low targets [13] [5] | ddPCR provides smaller coefficients of variation [5] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Susceptible to PCR inhibitors in samples [14] [7] | High tolerance to inhibitors [13] [14] | ddPCR better for complex samples (stool, soil, food) [14] |

| Throughput & Cost | Faster, cheaper, established protocols [7] | Higher cost, complicated processes [13] | qPCR more accessible for high-throughput screens |

| Reference Gene Requirement | Requires stable reference genes for normalization | No reference genes needed [15] | ddPCR avoids reference gene stability issues |

Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors

A significant advantage of ddPCR for environmental and complex samples is its superior tolerance to PCR inhibitors. Studies demonstrate that ddPCR exhibits greater resistance to common inhibitors like SDS and heparin, with more than a half-log increase in half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) values compared to qPCR. This enhanced tolerance occurs because reaction partitioning in ddPCR mitigates the impact of inhibitors—while inhibitors may delay amplification in affected droplets, they don't prevent target detection as in qPCR, where inhibitors affect the entire reaction [14].

Data Reproducibility and Precision

For low-abundance targets (typically with Cq ≥ 29), ddPCR typically produces more precise and reproducible data. In microbial quantification studies, ddPCR has demonstrated significantly smaller coefficients of variation compared to qPCR, especially at low target concentrations. This precision advantage makes ddPCR particularly valuable when quantifying rare targets or detecting small fold-changes (≤2-fold) in bacterial populations [16].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful relative quantification in qPCR requires specific reagents and materials optimized for reproducible results:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for qPCR Relative Quantification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SYBR Green or TaqMan Probes | Detection of amplified DNA | SYBR Green is more economical; TaqMan offers greater specificity [11] |

| High-Efficiency Master Mix | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, buffer | Use commercial master mixes for consistent results [11] |

| Low-Binding Tubes and Tips | Sample preparation and dilution | Minimizes nucleic acid loss during serial dilutions [10] |

| Stable Reference Genes | Normalization of qPCR data | Must be validated for consistent expression under experimental conditions [15] |

| Quality Controlled Primers | Target-specific amplification | Validate efficiency (95-105%), specificity, and absence of primer-dimers [11] |

| Standard Curve Reference Material | Quantification benchmark | Use purified genomic DNA, synthetic oligonucleotides, or pooled sample [11] |

Relative quantification using standard curves remains a powerful, accessible method for qPCR-based bacterial quantification, particularly when comparing gene expression or microbial abundance across experimental conditions. Its established protocols, broad dynamic range, and lower cost make it ideal for many research scenarios, especially those involving high-throughput analysis or well-characterized sample types with minimal inhibitors.

However, as the comparative data shows, ddPCR offers compelling advantages for specific applications in bacterial research, particularly when absolute quantification is required, when working with inhibitor-prone samples, or when detecting rare targets near the limit of detection. The choice between these technologies should be guided by specific research needs, considering factors like required precision, sample type, target abundance, and available resources.

For researchers committed to qPCR with relative quantification, rigorous attention to experimental details—including standard curve validation, efficiency verification, and reference gene selection—remains essential for generating reliable, reproducible data that advances our understanding of microbial systems.

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) represents a transformative approach in molecular biology, enabling absolute quantification of nucleic acids without reliance on standard curves. This guide explores the fundamental partitioning mechanism of ddPCR technology and objectively compares its performance to traditional quantitative PCR (qPCR) for bacterial quantification in research applications. Through examination of experimental data across multiple studies, we demonstrate how ddPCR's unique architecture provides enhanced sensitivity, precision, and tolerance to inhibitors—critical advantages for researchers and drug development professionals working with complex biological samples. The analysis is framed within the broader methodological consideration of qPCR versus ddPCR, with particular emphasis on applications in microbial detection and quantification.

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) revolutionizes nucleic acid quantification through a fundamental departure from traditional real-time PCR methodologies. Rather than measuring amplification kinetics, ddPCR employs sample partitioning to achieve absolute quantification without standard curves. The core innovation lies in dividing each PCR reaction into thousands of nanoliter-sized water-in-oil emulsion droplets, effectively creating individual microreactors where amplification occurs independently [17]. This partitioning converts continuous concentration measurements into discrete, countable events, enabling direct quantification through Poisson statistics.

The absolute quantification capability of ddPCR addresses a critical limitation of qPCR, which provides only relative measurements against reference standards. In qPCR, quantification depends on comparing the quantification cycle (Cq) of unknown samples to a standard curve, introducing potential variability from calibration errors and amplification efficiency differences [18]. In contrast, ddPCR's digital nature allows direct counting of target molecules, providing results in copies per microliter without external calibrators [17] [15]. This fundamental difference in approach makes ddPCR particularly valuable for applications requiring high precision across multiple laboratories or longitudinal studies where consistent quantification is essential.

The partitioning process underlying ddPCR technology follows a structured workflow that transforms a bulk PCR reaction into digitally analyzable data, providing the foundation for its superior quantification capabilities in complex research scenarios.

Fundamental ddPCR Partitioning Mechanism

Core Process Description

The ddPCR workflow begins with sample partitioning, where the reaction mixture containing template DNA, primers, probes, and PCR reagents is divided into approximately 20,000 nanoliter-sized droplets [17]. This partitioning occurs through microfluidic technology that generates uniform water-in-oil emulsion droplets, with each droplet functioning as an independent PCR reactor [17]. The random distribution of target DNA molecules follows Poisson distribution, ensuring that most droplets contain either zero or one target molecule, with progressively fewer droplets containing multiple copies [17].

Following partitioning, endpoint PCR amplification is performed on all droplets simultaneously. Unlike qPCR, which monitors fluorescence in real-time during the exponential phase, ddPCR continues amplification to completion, resulting in a binary fluorescence outcome for each droplet [17]. Droplets containing at least one target molecule generate strong positive fluorescence, while those without target remain negative [18]. This binary readout is inherently more resistant to amplification efficiency variations that often complicate qPCR quantification.

The final analytical phase involves droplet reading and statistical analysis. Each droplet is processed through a flow cytometer-like detector that categorizes it as positive or negative based on fluorescence thresholds [17]. The concentration of target nucleic acid is then calculated using Poisson statistics to account for the probability of multiple targets occupying single droplets, yielding absolute quantification in copies per microliter without reference to standards [17] [18]. This fundamental architecture provides the foundation for ddPCR's enhanced performance characteristics in bacterial quantification applications.

Performance Comparison: ddPCR vs. qPCR

Quantitative Comparison Table

Table 1: Direct performance comparison between ddPCR and qPCR for bacterial quantification

| Performance Metric | ddPCR Advantages | qPCR Advantages | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Absolute quantification without standard curves [17] | Relative quantification requiring standard curves [18] | Fundamental methodological difference |

| Detection Sensitivity | Limit of detection (LOD) of ~10³ cells/g feces for L. reuteri [19] | LOD of ~10⁴ cells/g feces for L. reuteri [19] | Spiked human fecal samples with strain-specific primers [19] |

| Dynamic Range | 1-100,000 copies per 20µl reaction [15] | Wider dynamic range than ddPCR [19] | Manufacturer specifications and experimental validation |

| Inhibition Resistance | High tolerance due to sample partitioning [17] [18] | Susceptible to PCR inhibitors in complex matrices [7] | Testing with spiked fecal samples and plant tissues [7] [18] |

| Precision | Lower coefficient of variation (CV), especially at low concentrations [18] | Higher CV compared to ddPCR [18] | Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri quantification in plant samples [18] |

| Cost and Throughput | ~3× more expensive and 6.5h processing time [20] | Lower cost and faster (2.5h processing time) [20] | Direct comparison for Lactobacillus reuteri quantification [20] |

| Reproducibility | Better reproducibility with some DNA extraction methods [20] | Comparable reproducibility with optimized DNA extraction [19] | Multi-operator, multi-instrument validation |

Comparative Performance Analysis

The experimental data reveal a complex performance landscape where each technology excels in different applications. For low-abundance targets, ddPCR demonstrates clear advantages, with studies reporting significantly lower limits of detection compared to qPCR. In one comprehensive analysis of Limosilactobacillus reuteri quantification in human fecal samples, ddPCR achieved a detection limit of approximately 10³ cells/g feces, while qPCR reached only 10⁴ cells/g feces using the same samples and DNA extraction methods [19]. This enhanced sensitivity makes ddPCR particularly valuable for detecting rare targets or quantifying minimal residual disease in clinical applications [17].

In terms of precision and reproducibility, ddPCR exhibits superior performance, especially at low target concentrations. A study quantifying Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri, the causative agent of citrus bacterial canker, found that ddPCR had a significantly lower coefficient of variation compared to qPCR, particularly at target concentrations near the detection limit [18]. This precision advantage stems from ddPCR's digital nature and resistance to amplification efficiency variations that affect qPCR quantification [18]. However, this precision comes with trade-offs in dynamic range, as qPCR typically offers a broader measurable concentration range without sample dilution [19].

For complex sample matrices, ddPCR's partitioning architecture provides notable advantages in inhibitor resistance. When quantifying bacterial pathogens in spiked fecal samples, ddPCR demonstrated greater resilience to PCR inhibitors present in complex biological samples [17] [7]. The partitioning process effectively dilutes inhibitors across thousands of droplets, minimizing their impact in individual reactions [17]. This tolerance to inhibitors can reduce the need for extensive sample purification, potentially simplifying workflows for challenging sample types commonly encountered in environmental and gut microbiome research [7].

Experimental Protocols for Bacterial Quantification

Strain-Specific Primer Design and Validation

The development of strain-specific PCR assays for bacterial quantification requires systematic primer design and validation. Based on optimized protocols from recent studies, the workflow begins with whole-genome comparisons between target and non-target strains to identify unique genomic regions [19] [7]. These specific sequences are then used to design primers and probes with stringent specificity requirements. For Limosilactobacillus reuteri strain quantification, researchers developed a step-by-step protocol that includes in silico specificity verification against database sequences, followed by empirical testing against closely related strains to confirm absence of cross-reactivity [19].

Following primer design, experimental validation proceeds through several critical phases. First, primer specificity is confirmed using pure cultures of target and non-target strains to ensure amplification only occurs with the intended target [19]. Next, standard curves are generated for qPCR applications using serial dilutions of target DNA with known concentration [7]. For ddPCR, optimal template concentrations are determined to maintain the recommended 1-100,000 copies per 20µl reaction range [15]. Finally, the complete system is validated using spiked samples, where known quantities of target bacteria are added to negative sample matrices (e.g., sterile stool or buffer) to determine recovery efficiency, limit of detection, and limit of quantification [19] [7].

DNA Extraction Method Comparison

The selection of DNA extraction methodology significantly impacts quantification accuracy for both ddPCR and qPCR. Comparative studies have evaluated multiple extraction approaches, including phenol-chloroform (PC) methods, QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (QK), and protocol Q (PQ) for bacterial quantification from fecal samples [7] [20]. These investigations revealed that kit-based methods (QK and PQ) generally produce DNA with higher purity and better quantification results compared to PC extraction, despite PC yielding higher DNA concentrations [20]. The PQ method specifically demonstrated superior recovery of Lactobacillus reuteri cells from feces, resulting in improved detection limits and linearity for both qPCR and ddPCR [20].

The interaction between DNA extraction method and PCR technology further influences overall performance. While ddPCR generally showed better reproducibility with QK and PC extraction methods, its performance with PQ extraction was comparable to qPCR [20]. This finding highlights the importance of considering the entire workflow—from sample preparation through final quantification—when designing bacterial quantification experiments. For complex matrices like fecal samples, the combination of PQ DNA extraction with qPCR quantification was identified as the optimal balance of performance, cost, and throughput for L. reuteri detection [20]. However, for applications requiring maximum sensitivity and inhibitor tolerance, PQ extraction with ddPCR may be preferable despite higher costs.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for ddPCR-based bacterial quantification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Strain-Specific Primers/Probes | Target-specific amplification | L. reuteri strain discrimination in fecal samples [19] |

| DNA Extraction Kits (PQ method) | High-purity DNA isolation from complex samples | Optimal recovery from fecal samples [7] |

| Droplet Generation Oil | Creation of water-in-oil emulsion for partitioning | Essential for ddPCR workflow [17] |

| Supermix for Probes | PCR reaction mixture with optimized chemistry | Compatible with droplet formation and endpoint detection [18] |

| Quantitative Standards | Reference materials for qPCR standard curves | Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri quantification [18] |

| Inhibition Resistance Additives | Enhance PCR efficiency in complex matrices | Improved detection in inhibitory samples [17] |

The partioning technology underlying Droplet Digital PCR represents a significant advancement in absolute quantification for bacterial detection and quantification. By dividing samples into thousands of individual reactions, ddPCR achieves unparalleled precision and sensitivity, particularly for low-abundance targets in complex matrices. The experimental data demonstrate clear performance advantages for ddPCR in applications requiring detection of rare targets, working with inhibitory samples, or achieving high precision without reference standards.

However, the choice between ddPCR and qPCR remains context-dependent. While ddPCR offers superior technical performance in several metrics, qPCR maintains advantages in throughput, cost, and dynamic range. Researchers must balance these factors against their specific application requirements, sample type, and resource constraints. For bacterial quantification in research and drug development, ddPCR provides a powerful tool when maximum sensitivity and absolute quantification are paramount, while qPCR remains a robust, cost-effective solution for higher-abundance targets. Understanding the fundamental partitioning mechanism and practical performance characteristics of both technologies enables researchers to make informed methodological selections for their specific bacterial quantification needs.

In the field of molecular biology, accurate quantification of nucleic acids is fundamental to many research and diagnostic applications. Two principal methodologies have emerged for this purpose: the quantification cycle (Cq) value approach used in quantitative PCR (qPCR) and the direct counting approach utilized in droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). While both techniques rely on the polymerase chain reaction to amplify target DNA sequences, their fundamental principles for quantification differ significantly. The Cq method provides a relative measure based on the kinetics of amplification, whereas direct counting offers absolute quantification through physical partitioning and binary detection. Understanding the distinctions between these approaches is critical for researchers, particularly in applications requiring precise nucleic acid quantification, such as microbial load assessment in microbiome studies, viral load determination, and validation of genome editing efficiencies. This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and practical applications of these two dominant quantification paradigms.

Fundamental Principles and Definitions

Cq Value Approach in qPCR

The quantification cycle (Cq) value, also known as cycle threshold (Ct), is defined as the PCR cycle number at which a sample's amplification curve intersects a fluorescence threshold set above background levels but within the exponential amplification phase [21] [22]. This value is inversely correlated with the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid—lower Cq values indicate higher initial target concentrations, while higher Cq values suggest lower target amounts [21]. The relationship between Cq and target concentration is described by the equation:

Cq = log(Nq) - log(N₀) / log(E)

Where Nq represents the quantity of amplicons at the threshold, N₀ is the initial target copy number, and E is the PCR efficiency [22]. This calculation demonstrates that Cq values are not direct measurements of quantity but rather relative positions on an amplification curve that must be interpreted through mathematical models and comparison to standards.

Direct Counting Approach in ddPCR

Direct counting in ddPCR represents a fundamentally different approach to nucleic acid quantification. This method partitions a PCR reaction into thousands to millions of nanoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets, effectively creating numerous individual reaction chambers [5]. After endpoint PCR amplification, each droplet is analyzed separately to determine whether it contains at least one copy of the target sequence (positive) or no target (negative) [23] [5]. The absolute concentration of the target nucleic acid in the original sample is then calculated using Poisson statistics based on the ratio of positive to negative droplets, without requiring calibration curves [5]. The fundamental calculation follows:

λ = -ln(1 - p)

Where λ represents the average number of target molecules per droplet and p is the fraction of positive droplets [5]. This direct counting approach provides absolute quantification by literally counting individual molecules through binary endpoint detection.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Key Metric Comparisons

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Cq-Based Quantification (qPCR) vs. Direct Counting (ddPCR)

| Performance Metric | Cq Value Approach (qPCR) | Direct Counting (ddPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Type | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (no standard curve needed) |

| Dynamic Range | Broader [5] | More limited [5] |

| Sensitivity | Lower detection limit ~10²-10³ copies/reaction | Higher sensitivity, can detect single copies [5] |

| Precision | Good for medium-high targets, higher CV at low concentrations [5] | Excellent precision, especially at low target concentrations [5] |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | Moderate, Cq values can be significantly affected [5] | High, due to endpoint detection and partitioning [5] |

| Reproducibility | Good between replicates, but inter-lab variation common [22] | Excellent reproducibility between labs and instruments |

| Cost and Throughput | Lower cost per sample, higher throughput [7] | Higher cost per sample, medium throughput [7] |

Table 2: Applications-Based Method Selection Guide

| Application Scenario | Recommended Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High-throughput screening | qPCR | Faster and more cost-effective for large sample numbers [7] |

| Low-abundance target detection | ddPCR | Superior sensitivity and precision at low concentrations [5] |

| Absolute quantification needs | ddPCR | No standard curve required, direct absolute measurement [24] |

| Gene expression analysis | qPCR | Established workflows, good for fold-change calculations |

| Complex sample matrices | ddPCR | Better resistance to PCR inhibitors [5] |

| Viral load detection | Both (context-dependent) | qPCR for routine monitoring, ddPCR for low viral loads |

Experimental Evidence from Comparative Studies

Recent comparative studies provide robust experimental data supporting these performance characteristics. In microbiome research, a 2024 systematic comparison found that while ddPCR showed slightly better reproducibility, qPCR demonstrated comparable sensitivity and linearity (R² > 0.98) with kit-based DNA isolation methods [7]. The limit of detection for both methods was approximately 10⁴ cells/gram of feces for quantifying Limosilactobacillus reuteri strains, though optimized qPCR protocols could achieve detection limits of around 10³ cells/gram [7].

A definitive comparison study focusing on plant pathogen detection (Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri) demonstrated that while qPCR had a broader dynamic range, ddPCR exhibited significantly higher sensitivity [5]. The ddPCR assay showed lower coefficients of variation, especially at low target concentrations, and demonstrated superior tolerance to PCR inhibitors commonly found in complex sample matrices [5]. The direct counting approach of ddPCR also eliminated issues related to calibration curve variations between laboratories, a known limitation of Cq-based quantification [5].

For bacterial quantification in human gut microbiome samples, both methods can effectively quantify 16S rRNA genes to determine prokaryotic concentration in stool samples, with the final output expressed as 16S rRNA copies per wet or dry gram of stool [24]. The selection between methods depends on the specific application requirements, with qPCR being cheaper and faster, while ddPCR provides superior absolute quantification without standard curves [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

qPCR Protocol for Bacterial Quantification

Protocol 1: Cq-Based Absolute Quantification of Prokaryotes in Stool Samples [24]

Sample Preparation:

- Measure stool sample moisture content by weighing before and after lyophilization.

- Homogenize stool samples in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to create a uniform suspension.

DNA Extraction:

- Use kit-based DNA isolation methods (e.g., QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit) for consistent results.

- Include appropriate controls to monitor extraction efficiency and potential contamination.

- Quantify DNA purity spectrophotometrically.

qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Prepare reaction mix containing: 2.5 μL PCR buffer (10×), 1.5 μL MgCl₂ (25 mM), 0.25 μL dNTPs (10 mM), 0.5 μL each forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 0.5 μL SYBR Green I, 0.25 μL Taq DNA polymerase, and template DNA.

- Use the following universal 16S rRNA gene primers:

- Forward: 5'-TCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT-3'

- Reverse: 5'-GGACTACCAGGGTATCTAATCCTGTT-3'

qPCR Amplification:

- Run on real-time PCR instrument with the following conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40 cycles of: 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 60 seconds

- Include standard curve with known copy numbers of target sequence.

- Run on real-time PCR instrument with the following conditions:

Data Analysis:

- Determine Cq values for each sample using instrument software.

- Calculate absolute target concentration by comparing sample Cq values to the standard curve.

- Normalize results to stool weight (copies/gram) accounting for moisture content.

ddPCR Protocol for Direct Counting

Protocol 2: Direct Counting Absolute Quantification of Bacterial Strains [7] [5]

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- Follow identical sample preparation and DNA extraction as in Protocol 1 to ensure comparable results.

Droplet Generation:

- Prepare PCR reaction mix containing: 1× ddPCR supermix, 900 nM primers, 250 nM probe, and template DNA.

- Load sample into droplet generator cartridge along with droplet generation oil.

- Generate approximately 20,000 nanoliter-sized droplets per sample.

PCR Amplification:

- Transfer droplets to 96-well PCR plate and seal.

- Perform amplification on thermal cycler with the following conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40 cycles of: 94°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 60 seconds

- Enzyme deactivation: 98°C for 10 minutes

- Include no-template controls to confirm absence of contamination.

Droplet Reading and Analysis:

- Place plate in droplet reader which measures fluorescence in each droplet individually.

- Set appropriate threshold to distinguish positive and negative droplets.

- Use Poisson statistics to calculate absolute concentration of target DNA in the original sample:

- Concentration (copies/μL) = -ln(1 - p) / V

- Where p = fraction of positive droplets, V = volume of each droplet

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nucleic Acid Quantification

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SYBR Green dye | Binds double-stranded DNA, enables fluorescence detection | Cost-effective for qPCR; compatible with most real-time instruments [25] |

| Sequence-specific probes (e.g., TaqMan) | Provide target-specific fluorescence through FRET | Increase qPCR specificity; require separate design and validation [25] |

| Droplet generation oil | Creates water-in-oil emulsion for partitioning | Essential for ddPCR; formulation affects droplet stability [5] |

| Digital PCR supermix | Optimized reaction mixture for partitioning | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers optimized for ddPCR [5] |

| Standard curve templates | Enables relative quantification in qPCR | Must be accurately quantified; plasmid DNA or synthetic oligos [22] |

| DNA extraction kits | Isolate nucleic acids from complex samples | Critical for both methods; choice affects yield and purity [7] |

| Passive reference dyes (e.g., ROX) | Normalize for well-to-well variations | Important for qPCR with non-uniform thermal conditions [21] |

| Microdroplet readers | Analyze individual droplets in ddPCR | Specialized equipment for endpoint fluorescence detection [5] |

Critical Considerations for Method Selection

Impact of PCR Efficiency on Quantification Accuracy

PCR amplification efficiency significantly impacts the reliability of Cq-based quantification but has minimal effect on direct counting approaches. The Cq value depends on PCR efficiency as shown in the fundamental equation Cq = log(Nq) - log(N₀) / log(E) [22]. Even small variations in efficiency (e.g., 90% vs 100%) can lead to substantial errors in calculated concentrations when using Cq values [22]. In contrast, direct counting with ddPCR is largely unaffected by PCR efficiency variations because it uses endpoint detection rather than amplification kinetics [5]. This makes direct counting particularly advantageous when amplifying difficult targets or working with samples containing PCR inhibitors.

Dynamic Range and Detection Limits

While direct counting methods generally offer superior sensitivity for low-abundance targets, Cq-based quantification typically provides a broader dynamic range [5]. The practical detection limit for qPCR is approximately 10-100 copies per reaction, while ddPCR can reliably detect single copies [5]. However, at high target concentrations, ddPCR suffers from saturation effects when too many droplets contain multiple targets, limiting its upper quantification range [23]. In such cases, sample dilution is required for accurate ddPCR quantification, while qPCR can handle higher concentrations without modification.

Practical Implementation Factors

For routine laboratory applications, Cq-based qPCR maintains advantages in throughput, cost-effectiveness, and established workflows [7]. The direct counting approach requires specialized instrumentation and more expensive reagents, making it less accessible for some laboratories [7]. However, for applications demanding absolute quantification across multiple laboratories or longitudinal studies, direct counting provides superior reproducibility without the need for harmonized standard curves [5]. The resistance of ddPCR to PCR inhibitors also makes it preferable for analyzing complex sample matrices like soil, feces, or clinical specimens [5].

Both Cq value quantification and direct counting represent powerful approaches for nucleic acid quantification with complementary strengths and limitations. The Cq-based approach using qPCR offers broader dynamic range, higher throughput, and lower per-sample costs, making it ideal for routine quantification where relative comparisons are sufficient and sample quality is consistent. Conversely, direct counting via ddPCR provides absolute quantification without standard curves, superior sensitivity and precision at low target concentrations, and greater resilience to PCR inhibitors—advantages that are particularly valuable for clinical diagnostics, rare target detection, and analyzing complex samples. The selection between these methodologies should be guided by specific application requirements, sample characteristics, and available resources rather than presuming universal superiority of either approach. As molecular quantification needs continue to evolve in research and diagnostic contexts, understanding these fundamental differences in quantification approach ensures appropriate method selection for generating reliable, reproducible results.

The Critical Role of DNA Extraction and Sample Preparation

Within the rapidly advancing field of microbiome research, the debate between quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for the absolute quantification of bacteria often focuses on the performance of the amplification chemistry itself. However, a factor of equal, if not greater, importance lies in the initial stages of sample processing: DNA extraction and sample preparation. The choice of how microbial DNA is isolated from complex matrices like fecal or environmental samples critically influences the accuracy, sensitivity, and reproducibility of any downstream molecular quantification [7] [20]. This guide objectively compares qPCR and ddPCR performance within the context of a broader thesis on absolute bacterial quantification, highlighting how DNA extraction protocols directly determine the success of the analytical method. We summarize experimental data and provide detailed methodologies to guide researchers in selecting and optimizing their sample preparation workflows.

qPCR vs. ddPCR: A Performance Comparison Shaped by Sample Preparation

The fundamental difference between the two techniques lies in their approach to quantification. qPCR is a sample-interdependent method that estimates the initial concentration of a target DNA by comparing the quantification cycle (Cq) of a sample to an external standard curve [18]. In contrast, ddPCR is a sample-independent method that partitions a reaction into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets, counts the positive and negative droplets after end-point amplification, and uses Poisson statistics to provide an absolute count of target DNA molecules without the need for a standard curve [18].

This core difference dictates how each technology responds to challenges originating from sample preparation, particularly the presence of PCR inhibitors. The following table summarizes key performance differences, with data drawn from direct comparative studies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of qPCR and ddPCR for bacterial quantification, influenced by DNA extraction and sample quality.

| Performance Metric | qPCR | ddPCR | Context from Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Basis | Relative to a standard curve [18] | Absolute count via Poisson statistics [18] | The need for a reliable standard curve in qPCR introduces an additional variable affected by sample purity. |

| Dynamic Range | Broader [7] [18] | More restricted [7] | One study noted qPCR's wider dynamic range as an advantage [7]. |

| Sensitivity (LOD/LOQ) | Slightly higher limit of detection [20] | Lower limit of quantification [20] | For L. reuteri in feces, ddPCR showed a lower LOQ [20]. In plant pathogen detection, ddPCR also showed significantly higher sensitivity [18]. |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | Susceptible; relies on amplification efficiency [26] [18] | Highly tolerant; less affected by inhibitors [13] [18] | ddPCR's partitioning dilutes inhibitors, making it more robust for complex samples like soil or feces [13]. Consistent contamination (e.g., from reverse transcriptase) can severely skew qPCR Cq values but has minimal impact on ddPCR quantification [26]. |

| Reproducibility | Good with high-quality DNA [7] | Excellent, especially for low-abundance targets [7] [13] | A study on L. reuteri found ddPCR had slightly better reproducibility with some DNA extraction methods [7]. Another study reported ddPCR had smaller coefficients of variation [13]. |

| Cost & Speed | Lower cost per reaction; faster (e.g., 2.5 hrs) [20] | Higher cost per reaction; more time-consuming (e.g., 6.5 hrs) [20] | The combination of being cheaper and faster was noted as a key advantage for qPCR [7] [20]. |

Impact of DNA Extraction Methods on Quantification Accuracy

The methodology used to isolate DNA from a sample is a critical pre-analytical variable. Different extraction techniques vary in their efficiency at lysing bacterial cells, their ability to remove co-extracted PCR inhibitors (such as humic acids in soil or bilirubin in feces), and the final purity and yield of the DNA [7].

A systematic comparison using human fecal samples spiked with a known quantity of Limosilactobacillus reuteri demonstrated that the choice of DNA extraction method directly impacts the apparent abundance measured by both qPCR and ddPCR [7] [20]. The study compared a phenol-chloroform-based method (PC), a commercial kit-based method (QK), and an optimized kit-based method (PQ) [7].

Table 2: Impact of DNA extraction method on the quantification of L. reuteri in human fecal samples [7] [20].

| Extraction Method | DNA Yield & Purity | Bacterial Cell Recovery | Linearity (R²) with qPCR/ddPCR | Limit of Detection (LOD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenol-Chloroform (PC) | Highest concentration, but lower purity [20] | Lower recovery of bacterial cells [7] | Lower linearity compared to kit methods [20] | ~4.86 Log10 CFU/g (qPCR) [20] |

| Kit-Based Method (QK) | Acceptable quantity and high quality [20] | Good recovery [7] | High linearity (R² > 0.98) [7] | ~3.95 Log10 CFU/g (qPCR) [20] |

| Optimized Kit-Based (PQ) | Good quantity and high quality [20] | The most substantial proportion of cells recovered [20] | High linearity (R² > 0.98) [7] | ~4.11 Log10 CFU/g (qPCR) [20] |

The data shows that while the PC method yielded a high concentration of DNA, the lower purity likely resulted in poorer cell recovery and a higher (worse) limit of detection. The kit-based methods, particularly the optimized PQ protocol, provided a superior balance of high-quality DNA and efficient cell recovery, leading to more sensitive and accurate quantification [7] [20]. This underscores that a high DNA concentration does not necessarily equate to a representationally accurate sample for microbial quantification.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for DNA Extraction and PCR

To ensure reproducible and high-quality results, adherence to validated protocols is essential. Below are detailed methodologies for DNA extraction and PCR setup as cited in the comparative literature.

DNA Extraction from Fecal Samples Using an Optimized Kit-Based Method (PQ)

This protocol is adapted from an optimized kit-based method (protocol Q) described for the absolute quantification of bacterial strains in human fecal samples [7].

Sample Pre-treatment:

- Weigh and Homogenize: Weigh 1 gram of stool sample and dilute it tenfold in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Wash Cells: Vortex the mixture vigorously. Take 1 mL of the homogenate (equivalent to 0.1 g of raw sample) and centrifuge at 8000 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C.

- Repeat Washing: Discard the supernatant and wash the cell pellet three times with ice-cold PBS buffer to remove soluble PCR inhibitors.

Lysis and DNA Isolation: The subsequent steps follow the protocol Q as previously described [7] [9], which is designed to maximize cell lysis and DNA recovery while maintaining purity. The precise steps involve:

- Resuspend Pellet: Resuspend the final washed cell pellet in a specialized lysis buffer.

- Enzymatic Lysis: Incubate the suspension with lysozyme and proteinase K to degrade the bacterial cell wall and associated proteins.

- Bind DNA: Use a commercial silica-membrane column to bind the DNA from the lysate.

- Wash Contaminants: Wash the bound DNA with provided buffers to remove salts, proteins, and other impurities thoroughly.

- Elute DNA: Elute the pure DNA in a low-EDTA Tris buffer or nuclease-free water.

Quality Control:

- Assess the purity of the isolated DNA spectrophotometrically by measuring the A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios. High-quality DNA should have an A260/A280 ratio of ~1.8 and an A260/A230 ratio greater than 2.0 [7].

Strain-Specific qPCR Assay Setup

This protocol outlines the steps for setting up a strain-specific qPCR assay based on a study that designed assays for L. reuteri strains [7].

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare Master Mix: For a 20 µL reaction, combine the following components:

- 10 µL of a 2x qPCR master mix (containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and MgCl₂).

- Forward and reverse strain-specific primers (final concentration typically 200-500 nM each).

- Fluorescently labeled probe (e.g., TaqMan) or DNA intercalating dye (e.g., SYBR Green).

- Nuclease-free water.

- Add Template DNA: Add 2-5 µL of extracted DNA template.

- Include Controls: Run each plate with a standard curve of known target concentration (e.g., serial dilutions of gBlock or plasmid containing the target sequence), no-template controls (NTC), and positive controls.

Amplification Conditions:

- Thermocycling: Perform amplification in a real-time PCR thermocycler using the following typical conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes.

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30-60 seconds (acquire fluorescence signal at this step).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the absolute quantity of the target in the sample by interpolating the Cq values against the standard curve.

Strain-Specific ddPCR Assay Setup

The ddPCR reaction mixture is similar to qPCR but is partitioned into droplets, and data is acquired at the end-point [18].

Reaction Setup and Partitioning:

- Prepare Master Mix: Prepare a PCR reaction mix similar to the qPCR assay, though the choice of fluorescent chemistry (probe-based is common) and optimal primer/probe concentrations may require re-optimization for the ddPCR platform.

- Generate Droplets: Load the reaction mixture into a droplet generator, which partitions each sample into 20,000 nanoliter-sized oil-emulsion droplets.

Amplification and Reading:

- PCR Amplification: Transfer the droplets to a 96-well plate and perform PCR amplification on a conventional thermal cycler to end-point. A standard two-step thermocycling protocol is used (e.g., 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 60 sec).

- Read Droplets: After amplification, transfer the plate to a droplet reader. The reader flows the droplets single file past a fluorescent detector, which classifies each droplet as positive or negative based on its fluorescence amplitude.

Data Analysis:

- Absolute Quantification: The concentration of the target DNA (in copies/µL) is calculated directly from the fraction of positive droplets using Poisson statistics, without the need for a standard curve [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials critical for successful DNA extraction and PCR-based bacterial quantification.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for DNA extraction and PCR quantification.

| Item | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer (with Lysozyme & Proteinase K) | Breaks down bacterial cell walls and degrades proteins to release DNA [7]. | Essential for efficient Gram-positive bacterial lysis in fecal samples [7]. |

| Silica-Membrane DNA Binding Columns | Selectively binds DNA in the presence of chaotropic salts, allowing impurities to be washed away [7]. | Used in kit-based DNA extraction methods (QK, PQ) for high-purity DNA isolation [7]. |

| Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl Alcohol | Organic solvent used to separate DNA from proteins and lipids in the sample [7]. | Used in traditional phenol-chloroform (PC) extraction protocols [7]. |

| Strain-Specific Primers & Probes | Oligonucleotides designed to uniquely amplify a target sequence from a specific bacterial strain [7] [18]. | Critical for the specific detection and quantification of a probiotic strain (e.g., L. reuteri DSM 17938) against a background of a complex microbiota [7]. |

| Digital PCR Supermix | A specialized PCR mix optimized for droplet formation and stability during ddPCR [18]. | Required for robust droplet generation and clear fluorescence separation in ddPCR assays [18]. |

| Quantitative PCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing Taq polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and optimized buffers for efficient amplification in qPCR. | The core reagent for any qPCR assay, with choice of chemistry (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan) [27]. |

Workflow Visualization: From Sample to Quantification Result

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points in the sample preparation and analysis pipeline, highlighting how the quality of DNA extraction dictates the optimal path to reliable quantification.

The choice between qPCR and ddPCR for absolute bacterial quantification is not made in isolation; it is profoundly influenced by the upstream processes of DNA extraction and sample preparation. While ddPCR offers clear advantages in tolerance to PCR inhibitors and precision for low-abundance targets, its higher cost and longer turnaround time are non-trivial considerations [7] [20]. Conversely, qPCR is a robust, cost-effective, and rapid technology, but its accuracy is highly dependent on the purity of the starting DNA template [7] [26].

The experimental data demonstrates that the use of optimized, kit-based DNA extraction methods can produce DNA of sufficient quality to make qPCR performance nearly comparable to ddPCR for many applications [7]. Therefore, the critical role of DNA extraction is to serve as the foundation upon which a reliable quantification assay is built. Researchers must view their workflow as an integrated system: investing in a validated, high-quality DNA extraction protocol can mitigate the limitations of qPCR or, alternatively, ensure that the superior technical performance of ddPCR is fully realized. A rigorous, methodical approach to sample preparation is the true differentiator in generating publication-quality data in the field of absolute bacterial quantification.

Implementing qPCR and ddPCR Protocols for Bacterial Detection and Quantification

Designing Strain-Specific Primers and Probes for Target Bacteria

In the evolving landscape of microbial research, the ability to accurately detect and quantify specific bacterial strains has become paramount across diverse fields including clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety. While species-level identification provides valuable information, many critical biological functions—such as virulence, antibiotic resistance, and biocontrol properties—are strain-specific attributes [28] [7]. The design of precise genetic markers for strain differentiation thus represents a fundamental challenge in molecular microbiology, with implications for diagnosing pathogens, tracking probiotic interventions, and monitoring microbial biocontrol agents in agricultural and environmental settings.

The emergence of digital PCR technologies has revolutionized absolute quantification approaches, creating a new paradigm for microbial detection and quantification. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison between quantitative PCR (qPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) methodologies within the context of strain-specific bacterial detection, empowering researchers to select the optimal approach based on their specific application requirements, sample type, and precision needs.

Fundamental Principles: qPCR vs. ddPCR

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Technology

Quantitative PCR, also known as real-time PCR, is a well-established molecular technique that enables both detection and quantification of specific nucleic acid sequences. This method relies on monitoring amplification in real-time through fluorescent signals that increase proportionally to the amount of amplified product. The quantification cycle (Cq), at which the fluorescence crosses a threshold, is used to estimate the initial template concentration by comparison with standard curves generated from known concentrations [18]. While qPCR provides excellent dynamic range and relatively quick results, its quantification is considered relative rather than absolute because it depends on external calibrators and assumes consistent amplification efficiency across samples [29].

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) Technology

Droplet digital PCR represents a fundamental shift in quantification approach by providing absolute nucleic acid quantification without the need for standard curves. The core innovation involves partitioning a single PCR reaction into thousands of nanoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets, effectively creating individual microreactions. Following end-point PCR amplification, each droplet is analyzed as either positive (containing at least one target molecule) or negative (containing no target). The absolute concentration of target DNA in the original sample is then calculated using Poisson statistics based on the ratio of positive to negative droplets [30] [29]. This partitioning approach also enhances resistance to PCR inhibitors, as inhibitors are similarly distributed across droplets rather than affecting the entire reaction [18].

Figure 1: ddPCR Workflow for Absolute Quantification

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data Analysis

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Multiple studies have systematically compared the sensitivity and detection limits of qPCR and ddPCR across various sample types and bacterial targets. The results consistently demonstrate ddPCR's superior sensitivity for low-abundance targets, while qPCR maintains advantages in dynamic range.

Table 1: Sensitivity Comparison Between qPCR and ddPCR

| Sample Type | Target Bacteria | qPCR LOD | ddPCR LOD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental samples | Mixed bacteria & fungi | Higher | Significantly lower | [13] |

| Human fecal samples | Limosilactobacillus reuteri | ~104 cells/g | Comparable sensitivity | [7] |

| Citrus samples | Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri | Higher | 6-fold more sensitive | [18] |

| Artificial mouse feces | Shigella spp. | 10 CFU/reaction | 1 CFU/reaction | [31] |

| Spiked fecal samples | L. reuteri PB-W1 & DSM 20016 T | ~103 cells/g | Similar detection limit | [7] |

In a direct comparison for detecting Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri, the causative agent of citrus bacterial canker, ddPCR demonstrated approximately 6-fold higher sensitivity compared to qPCR [18]. Similarly, when detecting Shigella species in artificial mouse feces, ddPCR showed 10-fold higher sensitivity than qPCR, with detection limits of 1 CFU/reaction versus 10 CFU/reaction, respectively [31].

Precision, Accuracy, and Resistance to Inhibitors

The partitioning technology underlying ddPCR provides inherent advantages in precision, particularly at low target concentrations, and greater resistance to PCR inhibitors common in complex sample matrices.

Table 2: Precision and Accuracy Comparison

| Parameter | qPCR Performance | ddPCR Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Good, but relies on standard curves | Excellent, absolute quantification without standards | Mock communities with known concentrations [13] |

| Precision at low concentrations | Higher CV (coefficient of variation) | Significantly lower CV | Detection of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri [18] |

| Inhibitor resistance | Susceptible to PCR inhibitors | High resistance; inhibitors affect only subset of droplets | Environmental samples with complex matrices [13] [18] |

| Reproducibility | Good with optimized assays | Excellent, with smaller coefficients of variation | Human fecal samples [7] |

In environmental samples containing both bacteria and fungi, ddPCR quantification results were "significantly closer to expected values (p < .05), and had smaller coefficients of variations (p < .05) than qPCR," indicating superior accuracy and repeatability [13]. The study also noted that ddPCR "had better precision, repeatability, sensitivity, and stability in bacterial and fungal quantitation than qPCR" across multiple habitat types [13].

Workflow Comparison: From Primer Design to Quantification

Strain-Specific Marker Identification and Primer Design

The initial phase of developing strain-specific detection assays involves identifying unique genetic regions and designing appropriate primers and probes. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) data has dramatically improved this process by enabling comprehensive genomic comparisons.

Figure 2: Workflow for Strain-Specific Primer Design

A robust workflow for strain-specific primer design begins with whole genome sequencing of the target strain and relevant reference strains [28]. Specific strain sequences are identified through bioinformatic comparisons, followed by careful primer and probe design targeting these unique regions. In silico verification through BLAST analysis against public databases ensures specificity before empirical testing [28]. This approach has been successfully applied to diverse bacterial genera, yielding "thousands of candidate markers" for strain-specific detection [28].

For Pseudomonas aeruginosa detection, researchers compared 816 publicly available genome sequences to identify a conserved and specific gene encoding a hypothetical protein (WP_003109295.1), then designed primers demonstrating "high level of sensitivity and specificity for P. aeruginosa among various Pseudomonas species" [32].

Sample Processing and Nucleic Acid Extraction

Proper sample processing and DNA extraction are critical steps that significantly impact quantification accuracy, particularly for complex sample matrices like feces, soil, or food products.

Table 3: Sample Processing Methods for Different Matrices

| Sample Type | Recommended Processing Method | Key Considerations | Application Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human fecal samples | Kit-based methods (QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit) | Better reproducibility compared to phenol-chloroform | [7] |

| Plant tissue | Soaking in PBS + centrifugation | Efficient recovery of pathogen cells from surface | [18] |

| Wastewater | Concentration + DNA extraction | Enables detection of antibiotic resistance genes | [33] |

| Seawater | Tangential flow filtration + DNase treatment | Concentrates viral particles for pelagiphage detection | [30] |

For human gut microbiome studies, systematic comparison of DNA extraction methods revealed that "kit-based DNA isolation methods" provided the best balance of sensitivity and reproducibility for absolute quantification of bacterial strains in fecal samples [7]. In plant disease diagnosis, a simple soaking and washing protocol effectively isolated Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri cells from citrus tissue according to the Chinese National Standard for diagnosis [18].

Quantification Workflows: qPCR vs. ddPCR

The operational workflows for qPCR and ddPCR share similarities but have distinct differences that influence their application in research settings.

Figure 3: Comparative Workflows of qPCR and ddPCR

The ddPCR workflow incorporates droplet generation as a crucial additional step that enables absolute quantification through binary counting of positive and negative reactions rather than continuous fluorescence monitoring [29]. This fundamental difference eliminates the need for standard curves and provides different advantages depending on the application context.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Strain-Specific Bacterial Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Strain-specific primers & probes | Target recognition and amplification | Hydrolysis probes for Xanthomonas citri [18]; ipaH9.8 gene primers for Shigella [31] |

| DNA extraction kits | Nucleic acid purification from complex matrices | QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit for fecal samples [7]; QIAamp Ultrasense Virus Kit for viral concentrates [30] |

| ddPCR supermix | Reaction mixture for droplet generation | EvaGreen or probe-based ddPCR assays [29] |

| Droplet generator & reader | Instrumentation for droplet creation and analysis | Bio-Rad ddPCR systems [29] |

| Standard reference materials | Quantification standards for qPCR | Linearized plasmid DNA [18]; cloned target sequences [32] |

Application-Oriented Selection Guidelines

Recommended Applications for ddPCR

Digital PCR technology excels in specific scenarios where its unique advantages provide significant experimental benefits:

Low-abundance targets: When detecting rare strains or targets near the detection limit, ddPCR's enhanced sensitivity provides superior performance [18] [31].

Inhibitor-rich samples: For complex sample matrices like soil, feces, or food that contain PCR inhibitors, ddPCR's partitioning provides inherent resistance [13] [18].

Absolute quantification requirements: When exact copy number determination is essential without reference standards [7] [9].