Selective Inhibition Agents: Precision Tools for Target Microbe Isolation and Antimicrobial Development

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the use of selective inhibition agents for the precise isolation of target microbes.

Selective Inhibition Agents: Precision Tools for Target Microbe Isolation and Antimicrobial Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the use of selective inhibition agents for the precise isolation of target microbes. It covers the foundational principles of selective action, from target-specific antibiotics to novel microbial metabolites, and details the methodological pipeline from screening to validation. The content addresses key challenges in the field, including economic barriers and resistance co-selection, and offers comparative analyses of agent efficacy. By synthesizing current research and emerging strategies, this review aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to advance precision microbiology and combat the escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance.

The Principles and Promise of Selective Inhibition: From Broad-Spectrum to Precision Antimicrobials

In antimicrobial research and therapeutic development, "selective inhibition" describes strategies designed to target a specific biological process, virulence factor, or a narrow range of microbial species, while minimizing impact on non-targets. This approach contrasts with broader-spectrum strategies that exert a wider, less discriminatory effect.

The following table outlines the core characteristics of these two strategies:

| Feature | Narrow-Spectrum / Selective Strategy | Broad-Spectrum Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Disable a specific function (e.g., virulence, biofilm formation) or target a specific pathogen [1] [2]. | Kill or inhibit a wide range of bacteria, typically both Gram-positive and Gram-negative [3]. |

| Mechanism of Action | Targets virulence factors (e.g., Type III Secretion Systems), biofilm matrix components, or specific enzymatic pathways [1] [2]. | Often targets essential, conserved cellular structures like the cell wall or ribosomes [3]. |

| Spectrum of Activity | Limited and precise [4]. | Wide range [3]. |

| Impact on Microbiota | Minimal disruption, as commensals are largely spared. | Significant disruption, which can lead to dysbiosis. |

| Pressure for Resistance | Theoretically lower, as it does not directly threaten bacterial survival [1]. | Higher, due to direct lethal pressure on a broad range of bacteria [1]. |

| Ideal Use Case | Targeted anti-virulence therapy, biofilm disruption, and isolating specific microbes. | Empiric therapy for severe infections when the pathogen is unknown [4] [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Selective Inhibition

Protocol: Assessing Selective Inhibition of a Bacterial Virulence System

This protocol is adapted from studies on inhibiting the Type III Secretion System (T3SS) in Yersinia enterocolitica [1].

- Objective: To evaluate the effect of a candidate compound (e.g., Cinnamtannin B1) on the expression and secretion of virulence factors without affecting bacterial growth.

- Materials:

- Bacterial strain: e.g., Yersinia enterocolitica KT0004 (for phospholipase activity assay) [1].

- Candidate inhibitor compound.

- Culture media: TYE medium (for flagellar T3SS), Ysp medium (high salt, for Ysa T3SS), Yop medium (37°C, low calcium, for Ysc T3SS) [1].

- Centrifuge and cold trichloroacetic acid (for protein precipitation).

- SDS-PAGE equipment and Western blot reagents for specific effector proteins (e.g., YopH, YopO).

- Method:

- Culture and Treatment: Grow bacteria in the appropriate secretion media in the presence or absence of the inhibitor compound.

- Separate Fractions: Centrifuge cultures to separate the bacterial cell pellet from the culture supernatant (which contains secreted proteins).

- Precipitate Secreted Proteins: Treat the supernatant with cold trichloroacetic acid to precipitate secreted proteins [1].

- Analysis:

- Analyze both cell pellets and precipitated supernatant proteins via SDS-PAGE.

- Perform Western blotting to quantify specific effector proteins (e.g., YopH, YopO) in both fractions.

- Compare band intensity between treated and untreated samples to determine inhibition of secretion.

- Viability Control: Perform viable cell counts (CFU/mL) or measure culture optical density (Abs600) to ensure the compound does not affect bacterial growth [1].

Protocol: Evaluating Inhibition of Biofilm Amyloid Matrix

This protocol is based on research investigating the inhibition of curli fibers in E. coli biofilms [2].

- Objective: To determine if a compound selectively inhibits the production of functional amyloid fibers (curli) in a biofilm.

- Materials:

- Bacterial strain: e.g., E. coli W3110 (produces curli as primary ECM).

- Candidate inhibitor (e.g., Bacillaene).

- Salt-free LB agar.

- Amyloid-binding dyes: Congo Red (CR) and Thioflavine S (TS).

- Macrocolony biofilm setup.

- Method:

- Macrocolony Assay: Inoculate the bacterium on CR-containing agar in the presence of the inhibitor, or set up a pairwise interaction with a putative inhibitor-producing strain (e.g., Bacillus subtilis) [2].

- Visual Assessment: After incubation, observe macrocolony morphology and red staining (from CR) as a direct readout for curli production. Inhibition is indicated by loss of typical morphology and lack of CR staining [2].

- Microscopic Validation:

- Prepare cross-sections of the biofilm.

- Stain with the fluorescent dye Thioflavine S (TS).

- Visualize under a fluorescence microscope. A dense network of TS-stained fibers around cells indicates normal curli production, while a lack of fluorescence or a dispersed, unstructured appearance indicates successful inhibition [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in Selective Inhibition Research |

|---|---|

| Cinnamtannin B1 | A natural compound used to selectively inhibit the expression and secretion of specific effector proteins (YopH, YopO) in the Ysc T3SS of Yersinia enterocolitica without broad bactericidal activity [1]. |

| Bacillaene | A microbial metabolite that acts as a bifunctional inhibitor, exhibiting antibiotic activity at high concentrations and selectively inhibiting the assembly of curli amyloid fibers in E. coli biofilms at lower concentrations [2]. |

| Specialized Culture Media (Yop, Ysp) | Defined media that create specific environmental conditions (e.g., 37°C, low calcium) to induce the expression and function of target systems like the T3SS, enabling the study of their selective inhibition [1]. |

| Amyloid-Binding Dyes (Congo Red, Thioflavine S) | Vital tools for visualizing and quantifying the extracellular amyloid matrix of biofilms. A reduction in dye binding is a key indicator of successful anti-curli inhibition [2]. |

| PF-06446846 (PF846) | A drug-like compound that selectively inhibits eukaryotic translation termination by stalling the ribosome, demonstrating the application of selective inhibition in modulating host cell processes [5]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My candidate compound shows excellent selective inhibition in vitro, but it is ineffective in a cell culture infection model. What could be the reason?

A: This is a common translational challenge. Consider the following:

- Cellular Toxicity: Test the compound on the host cell line alone to rule out general cytotoxicity.

- Serum Binding: The compound may bind to serum proteins in the culture medium, reducing its effective concentration.

- Poor Cellular Uptake: The compound might not efficiently enter the host cells where the pathogen resides. Review the compound's chemical properties (e.g., logP, molecular weight) to predict permeability.

- Metabolic Instability: Host or bacterial enzymes may be degrading or modifying the compound. Investigate the compound's stability in conditioned media or cell lysates.

A: If bacterial viability is unaffected, the issue likely lies in the induction or detection of the T3SS.

- Confirm T3SS Induction: Double-check that the culture conditions (temperature, calcium concentration, pH) are correct for strong induction of the T3SS in your specific bacterial strain [1].

- Positive Control: Include a known T3SS inhibitor (if available) or a mutant strain deficient in T3SS to confirm that your assay conditions can detect a reduction in secretion.

- Secretion Efficiency: Ensure the centrifugation speed and time are sufficient to completely clear the bacterial cells from the supernatant. Contamination of the supernatant with lysed cells will give false positive signals.

- Detection Sensitivity: Optimize the concentration of trichloroacetic acid for protein precipitation and consider using Western blotting instead of Coomassie-stained gels for higher sensitivity and specificity for your target effectors [1].

Q3: When testing a compound for selective biofilm inhibition, I see a reduction in matrix but also a reduction in bacterial growth. How can I determine if the anti-biofilm activity is selective?

A: To dissect these effects, perform a dose-response experiment.

- Dose-Response Curves: Test a range of concentrations of your compound.

- Dual-Readout Assay: At each concentration, measure both bacterial growth (e.g., OD600 or CFU/mL) and a biofilm-specific metric (e.g., crystal violet staining for total biomass, CR/TS staining for curli).

- Determine Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs): Identify the minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) and the minimum growth inhibitory concentration (MGIC). A compound with selective anti-biofilm activity will have an MBIC that is significantly lower than its MGIC [2]. This indicates that the matrix is disrupted at concentrations that do not affect planktonic growth.

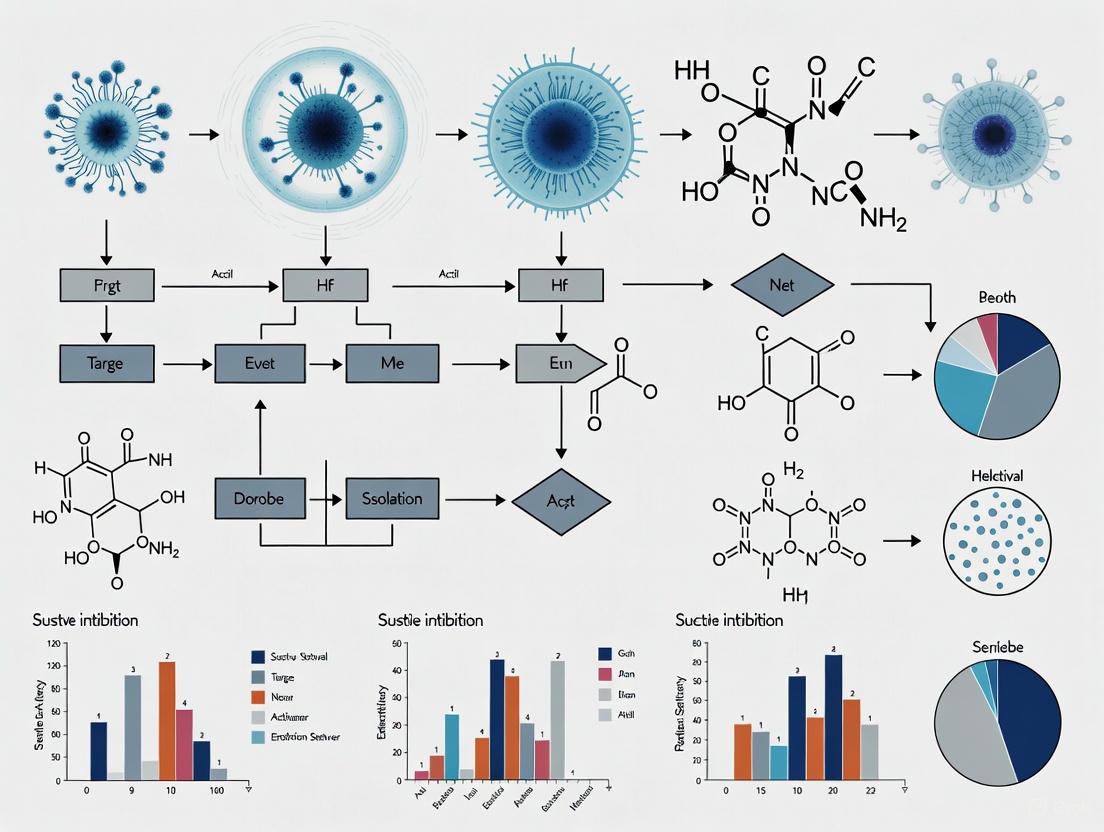

Visualizing the Strategic Concepts

The following diagram illustrates the core strategic differences between narrow-spectrum and broad-spectrum inhibition approaches.

The escalating global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis underscores the urgent need for antibiotics with novel mechanisms of action. Inhibitors targeting bacterial enoyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) reductases, particularly FabI, represent a promising class of antibacterial agents. These enzymes catalyze an essential, rate-limiting step in the bacterial fatty acid synthesis (FAS-II) pathway, which is fundamentally distinct from the mammalian FAS-I system. This structural and mechanistic divergence enables the development of inhibitors that selectively disrupt bacterial cell membrane integrity without harming host cells, making FabI a valuable target for selective inhibition and target microbe isolation research [6] [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges in FabI Research

1. Issue: Lack of Inhibitory Activity in Whole-Cell Assays Despite Strong Enzymatic Inhibition

- Potential Cause: Poor cellular penetration of the compound, often due to molecular properties incompatible with bacterial membrane transporters [8].

- Solution: Evaluate the compound against a panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. Gram-negative bacteria possess an outer membrane that can significantly limit uptake. Consider synthesizing analogs guided by rules for accumulation in Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., as applied in the development of fabimycin from Debio-1452) [8].

2. Issue: Inconsistent Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Values

- Potential Cause: Inoculum size effect or improper culture medium preparation.

- Solution: Standardize the bacterial inoculum to ensure it is within the range of 1-5 x 10^5 CFU/mL for broth microdilution methods. Use freshly prepared Mueller-Hinton broth according to CLSI guidelines, as variations in cation concentration can affect results [6] [9].

3. Issue: Inability to Confirm FabI as the Primary Cellular Target

- Potential Cause: Off-target effects or the presence of alternative enoyl reductase isozymes (e.g., FabK, FabV) that compensate for FabI inhibition [7].

- Solution: Perform genetic knockout studies. For instance, in P. aeruginosa, which expresses FabV, a FabV knock-out can restore sensitivity to FabI inhibitors like triclosan [8]. Additionally, establish a correlation between the inhibitor's Ki (enzyme inhibition constant) and its MIC value; a strong linear correlation suggests FabI is the primary target [7].

4. Issue: High Compound Toxicity in Eukaryotic Cell Lines

- Potential Cause: Lack of selective toxicity, potentially due to inhibition of mitochondrial function, as mammalian mitochondria share a prokaryotic ancestry [10].

- Solution: Conduct cytotoxicity assays on mammalian cell lines (e.g., HEK-293, HepG2) early in the development pipeline. Counter-screen against mammalian fatty acid synthase (FAS-I) to confirm selectivity for the bacterial FAS-II pathway [7] [10].

5. Issue: Rapid Development of Bacterial Resistance

- Potential Cause: Single-point mutations in the fabI gene that alter the inhibitor's binding site [7].

- Solution: Combine FabI inhibitors with other antibiotics having different mechanisms of action. This approach reduces the selective pressure for resistant mutants. Monitor for mutations in the FabI catalytic triad (Tyrosine, Lysine, Serine) through serial passage experiments [11] [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes FabI an attractive target for selective antimicrobial therapy? FabI is a key enzyme in the bacterial FAS-II pathway, which is essential for producing the lipids needed for bacterial cell membranes and, in Gram-negative bacteria, lipopolysaccharides. This pathway is absent in humans, who use the structurally different FAS-I system. Furthermore, FabI catalysis is a rate-determining step, meaning its inhibition severely disrupts the entire pathway, leading to bacterial cell death [6] [7].

Q2: Are there bacterial species inherently resistant to FabI inhibitors, and why? Yes, some species possess alternative enoyl-ACP reductase isozymes. For example, Streptococcus and Enterococcus express FabK, which is structurally and mechanistically distinct from FabI and resistant to typical FabI inhibitors like triclosan. Pseudomonas aeruginosa expresses FabV alongside FabI, contributing to its intrinsic resistance to many FabI inhibitors [8] [7].

Q3: How can I validate the binding mode of a novel FabI inhibitor? The most definitive method is X-ray crystallography of a ternary complex involving the target FabI enzyme, the NAD+ or NADH cofactor, and your inhibitor. This reveals atomic-level interactions, such as π-stacking with the nicotinamide ring of NAD+, hydrogen bonding with the catalytic tyrosine (e.g., Y159 in N. gonorrhoeae), and van der Waals contacts [12] [7]. Molecular dynamics simulations (e.g., 100 ns MD runs followed by MM-GBSA calculations) can further estimate binding stability and energies [6].

Q4: What are the critical steps for assessing the in vivo efficacy of a FabI inhibitor? After confirming in vitro potency and pharmacokinetic properties, use a relevant animal infection model. For instance, a murine vaginal gonorrhea model demonstrated the in vivo efficacy of Debio 1453 against multidrug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae [12] [13]. Key steps include infecting the animal, treating with the compound, and monitoring bacterial load reduction over time compared to controls.

Q5: What are the best practices for performing an enzymatic FabI inhibition assay? Use a spectrophotometric assay that monitors the decrease in absorbance of NADH at 340 nm. The reaction mixture typically contains Tris buffer (pH 8.0), NADH, the FabI enzyme, and a substrate like crotonoyl-CoA. Initiate the reaction with the substrate, and measure the initial velocity of NADH oxidation. Pre-incubate the enzyme with the inhibitor to detect time-dependent inhibition. Calculate IC₅₀ values from dose-response curves [8] [7].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The broth microdilution method is the standard for determining MIC [6].

- Preparation: Prepare Mueller-Hinton broth in 96-well plates. For fastidious organisms, supplement with lysed horse blood or other growth factors.

- Compound Dilution: Serially dilute the test compound in a logarithmic or two-fold manner across the plate.

- Inoculation: Standardize the bacterial suspension to 0.5 McFarland standard, then dilute to achieve a final inoculum of ~5 × 10⁵ CFU/mL in each well.

- Incubation & Reading: Incubate the plate at 35±2°C for 16-20 hours. The MIC is the lowest concentration of the compound that completely inhibits visible growth.

Protocol 2: Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation for FabI Inhibitors

This protocol is used to understand the binding mode and stability of inhibitors [6].

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of FabI (e.g., from PDB). Remove water molecules, add hydrogen atoms, and assign protonation states.

- Ligand Preparation: Draw the 3D structure of your inhibitor and minimize its energy using molecular mechanics.

- Docking: Perform molecular docking into the FabI active site (e.g., using MOE, AutoDock Vina) to generate potential binding poses.

- Simulation: Subject the best docking pose to molecular dynamics simulation (e.g., 100 ns using GROMACS/AMBER) in a solvated system to assess complex stability.

- Energy Calculation: Use MM-GBSA or MM-PBSA methods to calculate the binding free energy.

Quantitative Data on Promising FabI Inhibitors

The following table summarizes experimental data for key FabI inhibitors from recent literature, providing a benchmark for researchers.

Table 1: Comparative Activity of Selected FabI Inhibitors

| Compound Name / ID | Chemical Class | Target Enzyme | MIC Range (μg/mL) | Key Bacterial Strains | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RK10 [6] | Diphenylmethane | saFabI | 1.32 - 47.64 | S. aureus, B. subtilis, E. coli | Broad-spectrum activity; superior to lead MN02. |

| Debio 1453 [12] [13] | Pyrido-enamide | NgFabI | 0.008 - 0.125 | Multidrug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae | Sub-nanomolar enzyme inhibitor (IC₅₀ 0.6 nM); efficacious in vivo. |

| Compound 1 [7] | Benzimidazole | FtuFabI | N/A | F. tularensis | Novel binding mode distinct from triclosan; IC₅₀ 0.3 μM. |

| Nilofabicin (CG400549) [8] | 2-Pyridone | SaFabI | N/A | MRSA | Completed Phase 2 clinical trials for skin infections. |

| Fabimyrin [8] | Pyrido-enamide | FabI | N/A | Broad-spectrum (Gram-negative) | Derivative of Debio-1452 engineered for Gram-negative accumulation. |

| Triclosan [6] [7] | Diphenyl ether | FabI | 0.13 - 64.00 | S. aureus, E. coli | Prototypical FabI inhibitor; widely studied but clinical use limited. |

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for Key FabI Experimental Workflows

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Key Details / Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant FabI Enzyme | In vitro enzymatic inhibition assays. | Can be expressed in E. coli with an N-terminal His-tag for purification via nickel-chelated chromatography [7]. |

| NADH / NAD+ | Essential cofactor for FabI enzymatic activity. | Used in spectrophotometric assays; NADH oxidation monitored at 340 nm [7]. |

| Crotonoyl-CoA | Model substrate for FabI enzymatic assays. | The enoyl substrate that is reduced in the FabI-catalyzed reaction [7]. |

| Triclosan | Control compound for FabI inhibition studies. | A well-characterized, reversible FabI inhibitor; useful for validating new assay systems [6] [7]. |

| Mueller-Hinton Broth | Standard medium for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (MIC). | Must be prepared consistently to avoid cation concentration variations that affect results [6] [9]. |

Visualizing Mechanisms and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental processes discussed in this guide.

FabI Inhibition Mechanism

FabI Inhibitor Development Workflow

The modern antibiotic development pipeline is in a state of crisis, characterized by a critical void in novel drug discovery and an accelerating global spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This section addresses the most frequent high-level questions from researchers entering the field.

FAQ 1: Why is there so little investment in developing new antibiotics, despite a clear clinical need? The primary barrier is economic. Antibiotics are victim of a unique market failure where the financial return on investment (ROI) is fundamentally misaligned with their societal value.

- Short Treatment Duration: Unlike medications for chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes), antibiotics are typically prescribed for short courses (days or weeks), severely limiting revenue potential compared to drugs taken for life [14].

- High Development Cost, Low Revenue: The mean cost to develop a systemic anti-infective is estimated at $1.3 billion, matching other drug classes. However, a new antibiotic typically generates only $15-50 million in annual US sales, far less than the estimated $300 million per year needed for sustainability [15].

- Stewardship vs. Sales: Effective new antibiotics are deliberately held in reserve and used as a last resort to slow resistance. This necessary "stewardship" practice directly conflicts with traditional pharmaceutical sales models that rely on volume [15].

FAQ 2: What is the "discovery void," and how long has it lasted? The "discovery void" or "innovation gap" refers to the period since the last truly novel antibiotic class was discovered. Analysis shows there have been no successful discoveries of novel antibacterial classes since 1987. The few new classes approved since 2000 (e.g., oxazolidinones, lipopeptides) were first discovered or patented decades earlier [14] [16]. The pipeline is now dominated by analogues of existing classes, which offers only a temporary solution due to cross-resistance [14].

Table 1: Global Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

| Metric | Statistic | Source & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Global deaths associated with AMR (2021) | 4.71 million annually | [14] |

| Projected AMR-associated deaths by 2050 | 10 million annually | [14] |

| Laboratory-confirmed infections resistant to antibiotics (2023) | 1 in 6 (global average) | WHO GLASS report (2025) [17] [18] |

| Resistant infections in S.-E. Asia & E. Mediterranean | 1 in 3 | WHO GLASS report (2025) [18] |

| E. coli resistant to 1st-line antibiotics (3rd-gen cephalosporins) | >40% | [17] |

| K. pneumoniae resistant to 1st-line antibiotics (3rd-gen cephalosporins) | >55% | [17] |

Technical Troubleshooting: Selective Inhibition & Isolation

This section provides practical guidance for common experimental challenges in developing selective inhibition agents, particularly for isolating and targeting Gram-negative pathogens.

FAQ 3: My candidate inhibitor shows great in vitro binding but fails to kill or inhibit Gram-negative bacteria in culture. What are the most likely causes? This is a classic problem in antibacterial discovery. The most probable causes relate to the formidable barriers presented by the Gram-negative bacterial cell.

- Cause A: Impermeable Outer Membrane. The lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-rich outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria is a highly effective permeability barrier, blocking many hydrophobic and large compounds.

- Troubleshooting: Perform an accumulation assay. Compare intracellular concentration of your compound in a standard Gram-negative strain (e.g., E. coli) versus a strain with defined permeability mutations (e.g., lpxC mutants with impaired LPS biosynthesis). A significant increase in accumulation in the mutant strain confirms a permeability issue [16].

- Cause B: Efflux Pumps. Bacteria express multi-drug efflux pumps (e.g., AcrAB-TolC in E. coli) that actively export a wide range of compounds out of the cell.

- Troubleshooting: Repeat the MIC assay in the presence of a sub-inhibitory concentration of an efflux pump inhibitor (e.g., Phe-Arg β-naphthylamide, PABN). A significant drop (e.g., 4-fold or greater) in the MIC of your compound in the presence of the inhibitor indicates it is an efflux pump substrate [16].

FAQ 4: How can I selectively inhibit a specific bacterial target, like a biofilm matrix component, without broadly killing the organism? This approach, known as "anti-virulence" or "anti-biofilm" strategy, aims to disarm the pathogen without imposing strong selective pressure for resistance. A prime example is the inhibition of curli amyloid fibers in E. coli biofilms.

- Background: Curli fibers are a primary ECM component in many E. coli biofilms. Their synthesis involves a highly regulated pathway, offering multiple targets for selective inhibition [2].

- Experimental Protocol: Screening for Curli Inhibitors using Macrocolony Biofilms

- Strain and Media: Use E. coli K-12 strain W3110, which produces curli as its primary ECM. Use salt-free LB agar, optimal for curli production, supplemented with the amyloid-binding dye Congo Red (CR) at 20-40 µg/mL.

- Test Compound Application: Spot your candidate compound (e.g., purified metabolite, synthetic molecule) at a sub-inhibitory concentration (determined by prior MIC assay) onto the agar near the intended inoculation point.

- Inoculation and Growth: Inoculate the center of the plate with E. coli and incubate statically at 28-30°C for 3-5 days to allow macrocolony biofilm development.

- Analysis of Inhibition:

- Positive Result (Inhibition): A zone of altered morphology and lack of red CR staining around the compound spot indicates successful inhibition of curli production.

- Negative Result (No Inhibition): The biofilm will display a characteristic wrinkled, concentric ring morphology with intense, uniform red staining.

- Control: Always include a solvent-only control spot [2].

Diagram 1: Screening workflow for curli inhibitors.

Advanced Methodologies & Reagent Solutions

For researchers moving from screening to mechanistic studies, this section details specific protocols and essential reagents.

Experimental Protocol: Verifying Direct Inhibition of Curli Fiber Assembly In Vitro This protocol follows up on a positive result from the macrocolony screen to determine if the compound directly blocks the polymerization of the core curli subunits (CsgA and CsgB) [2].

- Purify Curli Subunits: Express and purify recombinant CsgA and/or CsgB protein from E. coli using His-tag affinity chromatography.

- Prepare Reaction Mixtures:

- Test: Purified CsgA (e.g., 5 µM) + candidate inhibitor at various concentrations.

- Positive Control: Purified CsgA alone.

- Negative Control: Buffer only.

- Induce Polymerization: Incubate all reaction mixtures at 37°C for 16-24 hours to allow for amyloid fiber formation.

- Quantify Amyloid Formation:

- Thioflavin T (ThT) Assay: Add ThT dye to each reaction. ThT fluorescence (excitation ~440 nm, emission ~485 nm) increases upon binding to amyloid fibrils. A significant reduction in fluorescence in the test sample compared to the positive control indicates direct inhibition of fiber assembly.

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Visualize aliquots from each reaction with TEM. The positive control should show abundant fibrils, while the effective test sample will show few or no fibrils.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Selective Inhibition Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Congo Red (CR) | Amyloid dye for visual detection of curli fibers in bacterial colonies or on filters. | CR binding is a qualitative, not quantitative, measure of curli production [2]. |

| Thioflavin T (ThT) / Thioflavin S (TS) | Fluorescent dyes used to quantify (ThT in vitro) or visualize (TS in situ) amyloid fibrils. | ThT fluorescence is directly proportional to amyloid content in solution [2]. |

| Bacillaene | A microbial metabolite serving as a proof-of-concept bifunctional inhibitor;它具有 bacteriostatic and anti-curli activity. | Demonstrates the potential for compounds that combine antibiotic and anti-virulence properties [2]. |

| Phe-Arg β-naphthylamide (PABN) | An efflux pump inhibitor used to troubleshoot compound accumulation in Gram-negative bacteria. | Can be toxic at high concentrations; use sub-inhibitory levels in checkerboard MIC assays [16]. |

| Salt-Free LB Agar | Culture medium optimized to induce robust curli production in E. coli for screening purposes. | Standard LB contains salt (NaCl), which can suppress curli expression [2]. |

Diagram 2: Curli biogenesis pathway and inhibition point.

Path Forward & Incentive Structures

FAQ 5: What innovative economic models are being proposed to fix the broken antibiotic market? Recognizing that traditional market forces are insufficient, global health bodies and industry alliances are proposing "pull" incentives to reward successful innovation.

- Lump-Sum Market Entry Rewards: Governments or a consortium of payers would offer a substantial, one-time monetary prize (e.g., $1-3 billion) to a company that successfully develops and licenses a priority antibiotic. This de-links the company's revenue from the volume of drug sold, allowing for responsible stewardship while ensuring a positive ROI [15].

- Subscription Models: Similar to Netflix, a government health system could pay an annual subscription fee to a company for access to a new antibiotic, regardless of how much is used in a given year. This model is already being piloted in the UK and Sweden [14] [15].

- Transferable Exclusivity Vouchers: A company that develops a priority antibiotic could receive a voucher granting an additional year of market exclusivity for any other drug in its portfolio, which could be worth billions. This voucher could also be sold to another company [15].

The quest for novel selective agents is pivotal in microbiology for isolating and studying specific microbes, a cornerstone of drug development and microbiological research. The human gut, a complex ecosystem teeming with microorganisms, produces a diverse array of metabolites that play crucial roles in microbial interference and communication. These gut-derived metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), bile acids, polyamines, and tryptophan derivatives, function as natural selective agents by modulating the microbial environment [19] [20]. They inhibit the growth of competing species, shape community structure, and maintain ecological balance, offering a rich repository of compounds for targeted microbial isolation and inhibition. Understanding the mechanisms of these endogenous metabolites provides a framework for developing sophisticated strategies to isolate target microbes, manipulating microbial communities to favor or suppress specific members, and discovering new therapeutic avenues. This technical support document synthesizes current knowledge on these microbial interactions, providing troubleshooting guidance and practical methodologies for researchers in the field.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary classes of gut-derived metabolites that can act as selective agents? The gut microbiota produces several key classes of metabolites with demonstrated selective, inhibitory potential [19] [20]:

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Acetate, propionate, and butyrate, produced from dietary fiber fermentation.

- Bile Acids: Primary bile acids (e.g., cholic acid) metabolized by gut bacteria into secondary bile acids (e.g., deoxycholic acid, lithocholic acid).

- Tryptophan Derivatives: Metabolites like indole-3-propionic acid and other indole derivatives produced from dietary tryptophan.

- Polyamines: Spermidine, spermine, and putrescine, derived from dietary protein and microbial synthesis.

FAQ 2: How do microbial metabolites achieve selective inhibition? Selective inhibition is achieved through multiple mechanisms [19] [20]:

- Receptor-Mediated Signaling: Metabolites bind to specific receptors on host or microbial cells (e.g., GPR41, GPR43, FXR, AhR), triggering signaling cascades that alter the microenvironment and make it less hospitable for certain microbes.

- Epigenetic Modulation: Metabolites like butyrate inhibit histone deacetylases (HDAC), influencing host gene expression related to inflammation and immune cell differentiation, which indirectly shapes the microbial community.

- Metabolic Interference: Some metabolites can disrupt essential metabolic pathways in susceptible microbes or alter local pH.

- Membrane Integrity: Certain metabolites, particularly secondary bile acids, can damage bacterial cell membranes.

FAQ 3: Why is my targeted inhibition of a pathogen using a metabolite not working? Several factors could be at play:

- Insufficient Concentration: The metabolite concentration may be below the effective inhibitory threshold. Troubleshooting:

- Perform a dose-response curve to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC).

- Ensure stability of the metabolite in your culture medium; some compounds may degrade.

- Microbial Resistance: The target pathogen may possess efflux pumps, degrading enzymes, or genetic mutations that confer resistance. Troubleshooting:

- Check for known resistance mechanisms in the literature.

- Consider using a combination of metabolites to overcome resistance.

- Incorrect Environmental Conditions: Factors like pH, oxygen levels, and the presence of other nutrients can affect metabolite activity. Troubleshooting:

- Mimic the natural gut environment as closely as possible (e.g., anaerobic conditions, appropriate pH).

- Review the growth requirements of both the target microbe and the producer microbes.

FAQ 4: How can I model complex gut microbiome interactions in vitro? To accurately study these interactions, complex models are required:

- Co-culture Systems: Culturing the target microbe with one or more producer strains.

- Simulated Gut Reactors: Using sophisticated bioreactors that simulate the human gut's physiological conditions, including pH gradients, nutrient delivery, and microbial retention times.

- Microbial Interaction Networking: Analyze your data to map out potential stimulatory and inhibitory relationships between the species in your consortium.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Metabolite Production in a Microbial Co-culture

- Potential Cause 1: Variability in the growth of the metabolite-producing strain.

- Solution: Standardize the inoculum preparation and growth conditions. Use spectrophotometry to ensure consistent starting optical density (OD). Monitor the growth of the producer strain separately to confirm its viability and metabolic activity.

- Potential Cause 2: Depletion of the necessary dietary precursor (e.g., fiber for SCFAs, tryptophan for indoles).

- Solution: Supplement the culture medium with an excess of the required precursor. Take regular samples to measure precursor concentration over time.

- Potential Cause 3: Metabolite degradation by other members of the microbial community.

- Solution: Profile the metabolite concentration throughout the experiment using techniques like Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS). This will help identify if the metabolite is being produced but then rapidly consumed or broken down.

Problem: Failure to Transmit a Phenotype via Fecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT) in a Gnotobiotic Mouse Model

- Potential Cause 1: Incomplete or unsuccessful microbial engraftment in the recipient.

- Solution: Verify engraftment by 16S rRNA sequencing of fecal samples from donors and recipients pre- and post-FMT. Ensure recipients are properly germ-free before the procedure.

- Potential Cause 2: Host factors (e.g., genotype, diet, age) are overriding the microbial influence.

- Solution: Tightly control the host environment, including using inbred mouse strains and providing a standardized diet. The study by [21] successfully used C57BL/6NTac mice and controlled conditions to demonstrate transmission of locomotion behavior.

- Potential Cause 3: The phenotype is dependent on a specific microbial consortium that is not being transferred intact.

- Solution: Consider using a defined microbial community (synthetic consortium) instead of a complex fecal slurry to reduce variability and identify key effector strains, as the enrichment of Lactobacillus was key to transmitting the behavior in the aforementioned study [21].

Quantitative Data on Key Microbial Metabolites

Table 1: Key Immunomodulatory Gut Microbial Metabolites and Their Functions [19] [20].

| Metabolite Class | Examples | Primary Microbial Producers | Key Receptors/Pathways | Immunomodulatory Role & Selective Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) | Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate | Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Clostridium clusters | GPR41, GPR43, GPR109A, HDAC inhibition | Promote Treg differentiation; inhibit HDAC; modulate cytokine production; can suppress specific pathogens by lowering pH. |

| Secondary Bile Acids (BAs) | Deoxycholic Acid (DCA), Lithocholic Acid (LCA) | Bacteroides, Clostridium, Eubacterium, Lactobacillus | FXR, TGR5 (GPBAR1) | Regulate Th17/Treg balance; DCA can negatively impact CD8+ T cell function [19]; exhibit direct antimicrobial activity against susceptible bacteria. |

| Tryptophan Derivatives | Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), Indole, Indolealdehyde | Clostridium sporogenes, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus | Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) | Enhance mucosal defense via IL-22; regulate Th17/Treg balance; induce apoptosis in Th1/Th17 cells [19]. |

| Polyamines | Spermidine, Spermine, Putrescine | Wide range, including Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides | Influences autophagy, mitochondrial function | Essential for T cell differentiation; promote Treg and suppress Th17 responses [19]. |

Table 2: Concentration Ranges and Experimental Considerations for Microbial Metabolites.

| Metabolite | Typical Colonic Concentration | Reported Experimental Doses (In Vitro/Vivo) | Stability & Handling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate | 20-70 mM [20] | 0.1 - 5 mM (cell culture) [19] | Sodium salt is stable. Store at room temperature. Soluble in water. |

| Propionate | 20-70 mM [20] | 0.1 - 5 mM (cell culture) [19] | Sodium salt is stable. Store at room temperature. Soluble in water. |

| Deoxycholic Acid (DCA) | Varies with diet | 50 - 500 µM (cell culture) [19] | Light-sensitive. Store at -20°C. Soluble in DMSO or ethanol. |

| Indole-3-propionic acid | µM range | 10 - 100 µM (cell culture) [20] | Store at -20°C. Soluble in DMSO. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Selective Inhibition Using Microbial Metabolites in Vitro

Objective: To determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of a gut microbial metabolite (e.g., a secondary bile acid) against a target bacterial pathogen.

Materials:

- Test Compound: e.g., Deoxycholic acid (DCA) sodium salt.

- Target Microbe: e.g., Clostridium difficile or other pathogen of interest.

- Growth Medium: Appropriate broth medium (e.g., BHI, YCFA).

- Equipment: Anaerobic chamber, 96-well flat-bottom plates, multichannel pipettes, spectrophotometer (plate reader).

Methodology:

- Preparation of Metabolite Stock Solution: Prepare a high-concentration stock solution of DCA in sterile water or DMSO. Filter sterilize (0.2 µm filter). If using DMSO, ensure the final concentration in the assay is ≤1% (v/v).

- Broth Microdilution in 96-well Plate:

- Dispense 100 µL of growth medium into all wells of a 96-well plate.

- Add 100 µL of the metabolite stock solution to the first well (e.g., well A1). Mix thoroughly. This is the first serial two-fold dilution.

- Serially dilute the metabolite across the plate by transferring 100 µL from well to well, resulting in a dilution series (e.g., from 1000 µM to ~2 µM). Discard 100 µL from the last well.

- Prepare a growth control well (medium + inoculum, no metabolite) and a sterility control well (medium only).

- Inoculation:

- Prepare a standardized inoculum of the target microbe in log-phase growth (e.g., 0.5 McFarland standard, ~1-5 x 10^8 CFU/mL).

- Dilute the inoculum in fresh medium to achieve a final concentration of ~5 x 10^5 CFU/mL in each well.

- Add 100 µL of the diluted inoculum to all test and growth control wells. Add 100 µL of sterile medium to the sterility control well. The final volume in each well is 200 µL.

- Incubation and Measurement:

- Seal the plate with a breathable membrane or lid and incubate under appropriate conditions (temperature, anaerobic) for 16-24 hours.

- Measure the optical density (OD) at 600 nm using a plate reader.

- Data Analysis:

- The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of the metabolite that completely inhibits visible growth (OD ~= OD of sterility control).

Protocol: Phenotype Transfer via Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

Objective: To transfer a microbiome-driven phenotype (e.g., reduced locomotion) to germ-free recipient mice, as described in [21].

Materials:

- Donor Mice: Mice exhibiting the desired phenotype (e.g., low activity).

- Recipient Mice: Age-matched, male germ-free mice (e.g., C57BL/6NTac strain).

- Equipment: Anaerobic workstation, homogenizer, cages with autoclaved bedding and food, behavioral tracking system (e.g., open field, automated cage system).

Methodology:

- Donor Fecal Sample Collection: Fresh fecal pellets are collected from donor mice directly into pre-reduced, sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) within an anaerobic chamber to preserve obligate anaerobes.

- Inoculum Preparation: Fecal material is homogenized in PBS (e.g., 1 pellet per 1 mL). The slurry is filtered through a sterile mesh to remove large particles. The inoculum should be prepared fresh and used immediately.

- Recipient Inoculation: Germ-free recipient mice are orally gavaged with a defined volume (e.g., 200 µL) of the fecal slurry. Control recipients receive slurry from control donors (e.g., high-activity or random selection).

- Phenotype Monitoring:

- House recipients in sterile, flexible film isolators or positive pressure ventilated cages to maintain sterility post-inoculation.

- Allow for stable microbial engraftment (typically 2-3 weeks).

- Assess the target phenotype (e.g., distance traveled, total activity) using standardized behavioral assays. The study in [21] measured "distance traveled" after 24 hours in an automated cage system at 5-6 weeks of age.

- Confirmation of Engraftment: Collect fecal samples from recipients pre- and post-FMT. Perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing to confirm that the donor microbial community has successfully colonized the recipients.

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram: Immunomodulatory Mechanisms of SCFAs

Diagram: Workflow for One-Sided Host-Microbiome Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Microbial Metabolites.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Germ-Free Mice | In vivo model to study causality of microbiome and metabolite effects without confounding microbial influences. | C57BL/6NTac strain used in phenotype transfer studies [21]. |

| Anaerobic Chamber | Provides an oxygen-free environment for handling obligate anaerobic gut bacteria and preparing fecal inocula to maintain microbial viability. | Essential for culturing many SCFA-producing bacteria like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. |

| Targeted Mass Spectrometry | Quantifying specific metabolite concentrations in complex samples like fecal content, serum, or culture media. | LC-MS/MS for precise measurement of SCFAs, bile acids, and tryptophan metabolites. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | Profiling microbial community composition to assess engraftment after FMT or changes due to metabolite treatment. | Standard method for confirming microbiome changes in animal models [21]. |

| G-Protein Coupled Receptor Assays | Mechanistic studies to validate direct binding and activation of host pathways by metabolites. | Cell-based assays for GPR41, GPR43, TGR5, etc. |

| Engineered Probiotics | Tool for delivering specific metabolites in situ. Bacteria engineered to overproduce a metabolite of interest. | e.g., Lactobacillus engineered to produce indole derivatives [20]. |

| Photoimmuno-Antimicrobial Conjugates | A novel targeted antimicrobial strategy using antibody-IR700 conjugates and near-infrared light to selectively eliminate pathogens [22]. | Effective against bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens, including drug-resistant strains, without disrupting commensals. |

A Practical Pipeline: Screening, Cultivation, and Application of Selective Agents

The relentless emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) presents a formidable global challenge, making the discovery of novel antimicrobial agents more critical than ever [23]. Screening methodologies form the backbone of this discovery process, providing crucial insights into the effectiveness and mechanisms of action of potential antimicrobial compounds [23]. These assays have evolved from simple, traditional techniques to sophisticated, high-throughput technologies.

Traditional agar-based methods, such as disk-diffusion and well-diffusion, are valued for their simplicity and low cost, providing a preliminary assessment of antimicrobial activity [23] [24]. In contrast, modern techniques like flow cytometry and bioluminescence assays offer higher sensitivity, reproducibility, and deeper insights into the impact of antimicrobials on cellular integrity and specific cellular functions [23]. The choice of screening method is pivotal, as it must align with the research goals, whether for initial broad screening or detailed mechanistic studies, to efficiently identify promising antimicrobial candidates in the fight against infectious diseases [23].

This technical support center is designed within the context of research on selective inhibition agents for target microbe isolation. It provides detailed troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and protocols to address the specific experimental challenges faced by researchers and drug development professionals utilizing these technologies.

Key Methodologies and Comparative Analysis

The following table summarizes the core principles, advantages, and limitations of the primary antimicrobial screening methodologies in use today.

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agar Diffusion (Disk/Well) [23] [24] | Measurement of microbial growth inhibition zones around a compound source on agar. | Simple, low-cost, ability to test many compounds/microbes. | Qualitative/semi-quantitative, cannot distinguish bactericidal vs. bacteriostatic effects. |

| Broth Dilution [23] | Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) via compound serial dilution in liquid media. | Provides quantitative MIC data. | Time-consuming, labor-intensive. |

| Time-Kill Kinetics [23] | Evaluation of the rate and extent of microbial killing over time. | Distinguishes bactericidal from bacteriostatic activity. | Complex protocol, requires multiple time-point sampling. |

| Flow Cytometry [23] | Multi-parameter analysis of single cells using light scattering and fluorescence. | Rapid, provides insights into mechanism of action on cellular integrity. | Higher cost, complex data analysis, requires expertise. |

| Bioluminescence [23] [25] [26] | Quantification of microbial viability or specific enzyme activity via light emission. | Highly sensitive, rapid, amenable to high-throughput screening (HTS). | Sensitivity to interfering compounds, requires specialized reagents. |

Advanced and Emerging Screening Technologies

Beyond the common methods, the field is rapidly advancing with technologies that offer greater depth of information or screening efficiency.

- Bioluminescence Inhibition Assays: These assays utilize bioluminescent proteins, such as aequorin or NanoLuc luciferase, as both recognition and signal-generating elements [25] [26] [27]. The core principle is that the binding of an inhibitory compound to the photoprotein can cause a dose-dependent decrease in bioluminescence, which can be quantified to detect the inhibitor [25]. This provides a rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective method for screening compounds that target specific microbial pathways [25].

- AI-Enhanced Screening: Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are now being deployed to accelerate antimicrobial discovery. These technologies can process large datasets to predict interactions between active compounds and microbial targets, and to design novel antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) with desired properties, significantly streamlining the initial discovery pipeline [28].

- Impedance Analysis & Bioautography: Other advanced techniques include impedance analysis, which measures electrical changes in media to monitor microbial growth, and bioautography, which couples thin-layer chromatography (TLC) with a biological activity assay to locate active compounds in a complex mixture [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Flow Cytometry Troubleshooting

Flow cytometry is a powerful tool for assessing antimicrobial mechanisms, but it can be prone to specific technical issues.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | • Low target expression.• Inadequate fixation/permeabilization.• Dim fluorochrome paired with low-density target.• Incorrect laser/PMT settings. | • Optimize treatment for target induction.• Follow standardized fixation/permeabilization protocols (e.g., ice-cold methanol added drop-wise while vortexing) [29].• Use brightest fluorochrome (e.g., PE) for lowest density targets [29].• Verify instrument settings match fluorochrome specs. |

| High Background/Non-specific Staining | • Fc receptor binding on immune cells.• Too much antibody.• Presence of dead cells.• High autofluorescence. | • Block with BSA, Fc receptor blockers, or normal serum [30] [29].• Titrate antibodies to optimal concentration.• Use viability dye to gate out dead cells.• Use red-shifted fluorochromes (e.g., APC) or brighter dyes in autofluorescent channels [29]. |

| Poor Cell Cycle Resolution | • High flow rate on cytometer.• Insufficient staining with DNA dye. | • Run samples at the lowest flow rate setting [29].• Resuspend cell pellet directly in PI/RNase solution and incubate sufficiently [29]. |

Bioluminescence Assay Troubleshooting

Bioluminescence assays are highly sensitive but can be affected by reagent stability and environmental factors.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal Intensity | • Luciferase enzyme inhibition or degradation.• Substrate depletion or instability.• Incorrect cation cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺). | • Ensure purified enzyme is active and stored correctly.• Use fresh, recommended substrates (e.g., D-luciferin, coelenterazine) [27].• Include necessary cofactors in reaction buffer (e.g., ATP/Mg²⁺ for firefly luciferase) [27]. |

| High Background Luminescence | • Contamination with luciferase-expressing microbes.• Auto-luminescence of test compounds.• Substrate contamination. | • Use aseptic technique.• Run control wells with compound alone (no enzyme) to check for interference.• Use high-purity substrates. |

| Inconsistent Results | • Inconsistent reagent dispensing.• Temperature fluctuations during reading.• Tandem dye degradation. | • Use automated dispensers for reagents.• Allow plate to equilibrate to instrument temperature.• Include tandem stabilizer in staining and storage buffers [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use agar diffusion versus broth dilution methods? A1: Use agar diffusion for initial, low-cost qualitative screening of a large number of compounds or microbial isolates to quickly identify those with inhibitory activity [23] [24]. Opt for broth dilution when you need a quantitative result, specifically the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), which is crucial for determining the potency of a promising compound [23].

Q2: How can flow cytometry provide information on the mechanism of antimicrobial action? A2: Flow cytometry can distinguish between different mechanisms of action by using fluorescent probes. For example, probes that assess membrane integrity (e.g., propidium iodide), metabolic activity, or mitochondrial membrane potential can be used simultaneously. The resulting multi-parameter data can indicate whether a compound is causing membrane disruption, metabolic shutdown, or apoptosis, providing a deeper understanding than growth inhibition alone [23].

Q3: What are the key advantages of bioluminescence-based screening assays? A3: The primary advantages are sensitivity, speed, and adaptability to high-throughput screening (HTS). These assays often have a wide dynamic range with very low background, allowing for the detection of subtle changes in viability or specific enzymatic activity [23] [26]. Reactions are typically rapid, and the format is easily miniaturized for automated screening of large compound libraries [25].

Q4: My flow cytometry data shows high background in the negative control. What steps should I take? A4: High background is often caused by non-specific antibody binding. First, ensure you are blocking your cells with an appropriate reagent like BSA, normal serum, or a commercial Fc receptor block, especially for immune cells [30] [29]. Second, titrate your antibodies to use the optimal concentration. Third, incorporate a viability dye to gate out dead cells, which often bind antibodies non-specifically. Finally, perform additional wash steps to remove unbound antibody [29].

Q5: Can AI truly accelerate the discovery of new antimicrobials? A5: Yes, AI and machine learning are proving to be transformative. They can rapidly analyze vast chemical and genomic datasets to predict new antimicrobial peptides, optimize existing compound structures, and identify potential targets [28]. This computational pre-screening narrows down the candidate pool, making the subsequent experimental validation in the lab far more efficient and targeted [28].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Principle: To evaluate the antimicrobial activity of a compound by measuring the zone of growth inhibition around a disk impregnated with the test substance.

Materials:

- Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) plates (or other appropriate media)

- Sterile filter paper discs (6 mm diameter)

- Standardized microbial inoculum (e.g., 0.5 McFarland standard)

- Test antimicrobial compound and appropriate controls (e.g., solvent, known antibiotic)

Procedure:

- Prepare a standardized bacterial suspension (e.g., equivalent to 0.5 McFarland standard, ~1.5 x 10⁸ CFU/mL).

- Evenly swab the entire surface of the MHA plate with the bacterial inoculum.

- Aseptically place the sterile paper discs onto the inoculated agar surface.

- Apply a defined volume (typically 10-20 µL) of the test compound onto separate discs. Include positive and negative control discs.

- Allow the discs to dry and then incubate the plates at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 37°C for most human pathogens) for 16-24 hours.

- Measure the diameter of the zones of inhibition (including the disc) in millimeters.

Principle: To detect specific surface markers on cells while minimizing non-specific antibody binding through a optimized blocking step.

Materials:

- Cells of interest (e.g., mammalian immune cells)

- FACS buffer (e.g., PBS with 1-2% FBS)

- Blocking solution (e.g., containing rat serum, mouse serum, and tandem stabilizer) [30]

- Fluorescently-conjugated antibodies

- V-bottom 96-well plates

- Centrifuge and flow cytometer

Procedure:

- Prepare Cells: Dispense cells into a V-bottom 96-well plate. Centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 minutes and remove supernatant.

- Block: Resuspend the cell pellet in 20 µL of blocking solution. Incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark [30].

- Stain: Prepare a surface staining master mix in FACS buffer containing the fluorescent antibodies and Brilliant Stain Buffer (if using polymer dyes). Add 100 µL of this mix directly to the cells without washing away the blocking solution. Mix by pipetting.

- Incubate: Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

- Wash: Add 120 µL of FACS buffer, centrifuge, and discard supernatant. Repeat this wash step with 200 µL of FACS buffer.

- Resuspend and Acquire: Resuspend the final cell pellet in FACS buffer and acquire data on a flow cytometer.

Principle: To detect inhibitors of a specific bioluminescent protein (e.g., aequorin) by measuring a dose-dependent decrease in light emission.

Materials:

- Purified bioluminescent protein (e.g., Aequorin)

- Required cofactors (e.g., Ca²⁺ for aequorin) and substrate (e.g., coelenterazine)

- Test compounds in a concentration series

- White, opaque multi-well plates

- Luminometer

Procedure:

- Reconstitute Protein: Activate purified aequorin by incubating with coelenterazine to form the functional holo-protein.

- Dispense Reagents: In a white 96-well plate, mix a fixed concentration of the test compound with a constant amount of the functional aequorin.

- Initiate Reaction: Trigger the bioluminescence reaction by injecting a solution containing calcium ions.

- Measure Luminescence: Immediately measure the peak luminescence or integrated light output over a short period (seconds) using a luminometer.

- Analyze Data: Plot the relative light units (RLU) against the compound concentration. A decrease in RLU compared to the no-inhibitor control indicates inhibition.

Workflow Visualization

Agar Diffusion Assay Workflow

Bioluminescence Inhibition Assay Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents essential for successfully conducting the featured modern screening methodologies.

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Brilliant Stain Buffer [30] | Prevents dye-dye interactions between conjugated antibodies in polychromatic flow cytometry. | Critical for panels using SIRIGEN "Brilliant" or "Super Bright" polymer dyes to ensure accurate signal detection [30]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent [30] [29] | Reduces non-specific antibody binding to Fc receptors on immune cells (e.g., monocytes). | Significantly lowers background staining in flow cytometry. Can be normal serum or commercial blocking reagents. |

| Tandem Stabilizer [30] | Prevents the breakdown of tandem fluorophores, which can cause erroneous signal detection. | Should be included in staining buffers and sample storage buffers for flow cytometry to maintain signal integrity. |

| Coelenterazine [25] [27] | Substrate for coelenterazine-dependent bioluminescent systems (e.g., Aequorin, Gaussia, NanoLuc). | Light-sensitive and can be unstable; requires proper storage and handling. Different analogs offer varying emission properties and permeability. |

| D-Luciferin [27] | Substrate for D-luciferin-dependent luciferases (e.g., Firefly, Click Beetle). | Requires ATP and Mg²⁺ as cofactors. Used in assays for viability, metabolism, and reporter gene expression. |

| Viability Dye (e.g., PI, 7-AAD) [29] | Distinguishes live from dead cells based on membrane integrity. | Essential for gating out dead cells in flow cytometry to reduce non-specific background and improve data quality. |

| Aminoluciferin (AML) Conjugates [26] | Acts as a dark substrate for luciferase; light is emitted upon cleavage. | Used in protease activity assays (e.g., DUB-Glo). Conjugation to full-length proteins (e.g., Ub-AML) increases specificity versus short peptide substrates. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor or No Growth of Target Fastidious Anaerobe

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Oxygen Exposure | Use specialized anaerobic transport systems (e.g., Anaerobic Transport Medium) for specimen collection; never use swabs, opt for tissue biopsies or aspirates [31]. |

| Improper Storage of Media | Store dehydrated media in a cool, dry environment; heat and moisture can degrade nutrients. Store prepared plates in conditions that maintain product quality [32]. |

| Suboptimal Growth Conditions | Ensure the use of a rich, specialized base medium like Fastidious Anaerobe Agar (FAA). Provide appropriate temperature and atmospheric conditions for the specific anaerobe [33] [34]. |

| Incorrect Incubation Parameters | For anaerobic growth, use an anaerobic indicator and validate incubator temperatures routinely. Incubate plates in stacks of four or less to ensure rapid, even warming [35]. |

Problem: Contaminated Cultures or Overgrowth of Competing Flora

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Faulty Media Sterilization | Follow stated sterilization directions precisely; use autoclaves, not microwaves, to prevent nutrient destruction or toxin development [32]. |

| Use of Expired Media | Never use expired collection media or agars; components like reducing agents and selective agents degrade, leading to false results [31]. |

| Leaking Specimen Container | Ensure transport containers (e.g., Lukens traps) are securely closed with sterile transport caps, not tubing, to prevent leaks and contamination [31]. |

| Insufficient Selective Agents | Confirm that selective additives (e.g., antibiotics) are added correctly—after sterilization if heat-labile—and at the proper concentration [32] [36]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the recommended medium and method for culturing a broad spectrum of anaerobic bacteria from fecal samples? A1: Fastidious Anaerobe Agar (FAA-HB) is highly recommended. A 2025 study demonstrated that FAA-HB exhibited excellent culture performance for thirty-six anaerobic species from fecal samples, with most EUCAST candidate-species showing confluent growth within 16-20 hours. It also performed well for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) [33] [34].

Q2: Why is my target microbe growing poorly on selective media but well on non-selective media? A2: This is expected behavior. Selective media contain inhibitors (like crystal violet, bile salts, or antibiotics) that create a stressful environment to suppress competing flora. While they allow the target to grow, it will not be as luxuriantly as on a nutrient-rich, non-selective medium. There is no requirement for a specific percent recovery on selective versus non-selective agar [35].

Q3: How should I handle and transport samples for anaerobic culture? A3: Proper handling is critical.

- Collection: Use aspirates or tissue biopsies; swabs are not appropriate [31].

- Transport: Place the specimen in an Anaerobic Transport Medium (ATM), which is designed to exclude oxygen [31].

- Transport Conditions: Keep specimens at room temperature during transport; oxygen diffuses more easily into cold liquid medium. Deliver to the lab within 3 hours [31].

Q4: What are some best practices for preparing culture media to ensure optimal growth? A4:

- Storage: Protect dehydrated media from extreme temperatures and moisture, which can destroy nutrients [32].

- Preparation: Use trained staff and the correct labware (e.g., a flask of appropriate size) for accurate measuring and mixing [32].

- Sterilization: Follow manufacturer directions for autoclaving to avoid damaging heat-sensitive components [32].

- Additives: Add supplements like antibiotics after sterilization if they are heat-labile [32].

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Culture Media Performance for Fastidious Anaerobes

Objective: To assess the growth promotion properties of a selective or enriched medium (e.g., Fastidious Anaerobe Agar) for specific fastidious anaerobic bacteria.

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Use a standardized inoculum to deliver 10-100 Colony Forming Units (CFU) per plate [35]. Confirm the viable count of the inoculum by parallel plating on a non-selective agar like Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) [35].

- Plating: Inoculate the test batch of the selective/enriched medium and a previous, approved batch of the same medium for comparison. Use the spread plate or pour plate method.

- Incubation:

- Analysis: After incubation, count the colonies on each plate. The growth on the new batch of media should be "comparable" to the previous batch. The USP states that the strict "factor of two" rule does not necessarily apply to selective media [35].

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Fastidious Anaerobe Agar (FAA-HB) | A highly effective solid medium supporting the rapid growth (16-20 hours) of a wide spectrum of anaerobic bacteria from clinical and environmental samples [33] [34]. |

| Anaerobic Transport Medium (ATM) | A specialized collection medium designed to exclude oxygen and preserve the viability of fastidious anaerobic bacteria during specimen transport from clinic to lab [31]. |

| Selective Media (e.g., MacConkey Agar) | Contains inhibitors (e.g., crystal violet, bile salts) that suppress the growth of Gram-positive bacteria, thereby selecting for specific Gram-negative organisms [36]. |

| Differential Media (e.g., Blood Agar) | Allows differentiation of microorganisms based on their biochemical reactions, such as hemolysis patterns on blood agar or color changes on EMB agar from fermentation [36]. |

| EZ-Accu Shot / EZ-CFU | Commercially prepared, standardized microbial inoculants that deliver a precise CFU range (e.g., 10-100 CFU), saving hands-on time and improving Growth Promotion Test reproducibility [35]. |

This technical support center addresses key challenges in developing antibiotics that selectively target pathogens while preserving the beneficial gut microbiome. This approach is critical for treating infections without causing dysbiosis—an imbalance in gut microbiota linked to secondary infections and other long-term health issues [37]. Below, you will find troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed protocols to support your research on selective inhibition agents.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are pathogen-selective antibiotics and why are they important?

Answer: Pathogen-selective antibiotics are designed to target and kill specific pathogenic bacteria without harming commensal (beneficial) gut bacteria. Traditional broad-spectrum antibiotics disrupt the gut microbiome, leading to dysbiosis. This can result in secondary infections like Clostridioides difficile, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and other long-term health problems [37]. Selective antibiotics aim to maximize treatment efficacy while minimizing these collateral detrimental effects on the host's microbiome.

FAQ 2: My bacterial cultures are being contaminated by fast-growing organisms likeE. coliafter sample collection. How can I prevent this?

Answer: The overgrowth of organisms like E. coli is a classic sign of inadequate sample preservation. To prevent this bias:

- Preserve Immediately: Do not delay sample stabilization. Even short delays can allow fast-growing species to bloom and consume others, severely skewing the microbial community data [38].

- Use Chemical Preservatives: Relying on freezing alone can be insufficient, as freeze-thaw cycles lyse cells (especially Gram-negative ones) and reactivate degradative enzymes upon thawing. Use room-temperature chemical preservatives (e.g., DNA/RNA Shield) that instantly inactivate nucleases and stop all biological activity at the point of collection [38].

- Avoid Freeze-Thaw Cycles: If you must freeze samples, ensure it is at -80°C and avoid repeated thawing, as damage is cumulative and selectively affects more fragile microbes [38].

FAQ 3: I am working with a Gram-negative pathogen. Why is my experimental compound failing to lyse the cells for analysis?

Answer: Gram-negative bacteria can be difficult to lyse due to their complex cell envelope.

- Modify the Growth Medium: Bacteria grown in rich media (high glucose) are particularly resistant to lysis. Try reducing the glucose concentration in your culture medium [39].

- Use Enhancing Agents: For efficient lysis of Gram-negative bacteria, add lysozyme to your lysis reagent. For some over-expressed proteins, this may not be needed, but it is generally recommended [39].

- Pre-treatment: Freezing the bacterial cells before extraction can also make them more susceptible to lysis [39].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: In Vitro Assessment of Selective Antibacterial Activity

This protocol outlines how to evaluate a compound's ability to selectively target a pathogen while sparing commensal bacteria.

- 1. Culturing: Grow your target pathogen (e.g., a multidrug-resistant Gram-negative strain) and selected commensal bacteria (e.g., Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron) in appropriate media and conditions [40].

- 2. Compound Exposure: Treat the cultures with your experimental compound at a range of concentrations. Include controls (vehicle-only) for both pathogen and commensals.

- 3. Viability Assessment: After a set incubation period, determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for both the pathogen and the commensal strains. Use methods like broth microdilution or plating for colony-forming unit (CFU) counts [40].

- 4. Selectivity Calculation: A selective compound will show a significantly lower MIC against the pathogen compared to the commensal strains. The selectivity index can be calculated as (MICcommensal / MICpathogen).

Protocol 2: Evaluating Microbiome Sparing in a Mouse Model

This in vivo protocol tests the impact of an antibiotic on the gut microbiome.

- 1. Animal Grouping: House mice in controlled conditions and divide them into groups: one treated with your selective antibiotic, one with a broad-spectrum antibiotic (positive control), and one with a vehicle (negative control) [40].

- 2. Dosing: Administer the compounds to the mice orally or via injection for a set duration.

- 3. Fecal Sample Collection: Collect fecal samples at baseline, during treatment, and post-treatment. Crucially, preserve samples immediately in a stabilizing solution like DNA/RNA Shield to prevent microbial community shifts after collection [38].

- 4. Microbiome Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from the preserved samples and perform 16S rRNA gene sequencing or shotgun metagenomics to analyze the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota [40].

- 5. Pathogen Challenge (Optional): To demonstrate functional protection, challenge the mice with a pathogen like Clostridioides difficile after the antibiotic course and monitor for infection [40].

Quantitative Data on Microbiota-Sparing Antibacterial Agents

The table below summarizes key experimental data for emerging selective antibacterial agents, demonstrating their potential to spare the gut microbiome.

Table 1: Overview of Microbiota-Sparing Antibacterial Agents [37]

| Antibacterial Agent | Target / Mechanism of Action | Selectivity Towards Pathogen | Gut Microbiota Sparing Property | Clinical Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lolamicin | Lipoprotein transport system (LolCDE) | >130 multidrug-resistant clinical Gram-negative isolates [40] | Spared gut microbiome in mice; prevented secondary C. difficile infection [40] | Preclinical |

| Hygromycin A | Pathogen-specific BmpD transporter | Borrelia burgdorferi | Caused only mild microbiota changes, promoted beneficial bacteria [37] | Phase 1 |

| Ridinilazole | Binds DNA minor groove; interferes with cell division | Clostridium difficile | Minimal disruption, preserved key microbiota for bile acid metabolism [37] | Phase 3 |

| Cadazolid | pH-dependent cellular uptake | Clostridium difficile | Spared Gram-negative anaerobes like Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron [37] | Discontinued after Phase 3 |

| Ribaxamase | β-Lactamase enzyme degrades antibiotics in GI tract | N/A (protects microbiome from antibiotics) | Safeguarded gut microbiota from ceftriaxone-induced damage [37] | Phase 1b/2a |

Mechanisms and Targets for Selective Antibiotics

The table below lists validated and emerging bacterial targets for developing novel antibacterial agents.

Table 2: Promising Targets for Novel Antibacterial Agents [41]

| Target Category | Specific Target | Rationale for Selectivity |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Wall & Membrane | Lipoprotein Transport (LolCDE) | Essential for viability of Gram-negative bacteria; low sequence homology in commensals like Bacteroides allows for selective targeting [40]. |

| Cell Wall & Membrane | Peptidoglycan Biosynthesis | Preferred target as mammalian cells lack a peptidoglycan wall structure [41]. |

| Protein Synthesis | Methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MetRS) | Differences in bacterial vs. human enzyme structures can be exploited for selective inhibition [37]. |

| DNA Replication | DNA Polymerase IIIC | A bacterial-specific enzyme, making it an ideal target for selective antibiotics [37]. |

| Metabolic Pathways | Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR) | Can be targeted with adjuvants (e.g., thymine) to create pathogen-selective inhibition [37]. |

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

Lolamicin Selective Inhibition Mechanism

Microbiome-Sparing Drug Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Selective Agent and Microbiome Research

| Item | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Shield or similar | Chemical preservative that instantly stabilizes nucleic acids in samples (e.g., feces) at room temperature. | Inactivates nucleases and prevents microbial growth; crucial for preserving an accurate snapshot of the microbiome at collection [38]. |

| Glycerol (15-20% v/v) | Cryoprotectant for long-term storage of bacterial and fungal strains at -80°C. | Glycerol stocks are considered good indefinitely if freeze-thaw cycles are avoided [39]. |

| Selective Antibacterial Agents (e.g., Lolamicin) | Tool compounds for validating selective inhibition in vitro and in vivo. | Key for proof-of-concept studies demonstrating microbiome sparing [40]. |

| Lysozyme | Enzyme used to break down the peptidoglycan layer of bacterial cell walls, aiding in lysis. | Essential for efficient extraction from Gram-positive bacteria; often improves lysis of Gram-negative strains as well [39]. |

| B-PER Reagent or similar | Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent for lysing bacterial cells to isolate proteins or nucleic acids. | More efficient for Gram-negative bacteria but can be used for some Gram-positives, especially with lysozyme addition [39]. |

This technical support guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers using metagenomics to identify Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs), particularly within the context of developing selective inhibition agents for target microbe isolation. The content addresses common computational and experimental challenges in profiling microbial communities for bioactive compound discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the advantage of a taxonomy-guided approach for BGC identification over direct read-mapping methods?

A taxonomy-guided approach, as implemented in tools like TaxiBGC, first identifies the microbial species present in a metagenome before predicting BGCs. This method significantly improves predictive performance. In benchmarks, this approach achieved a mean positive predictive value (PPV) score of 0.80, compared to 0.41 for methods that directly map sequencing reads onto BGC genes. The F1 score, a measure of overall accuracy, was also higher (0.56 vs. 0.49) [42]. This strategy reduces false positives and allows researchers to trace BGCs back to their likely taxonomic origins.

Q2: My metagenomic assembly is not reconstructing BGCs effectively. What strategies can improve this?

Poor BGC reconstruction often stems from suboptimal assembly. The choice of assembler and parameters is critical:

- Assembler Selection: For single-sample projects,

metaSPAdesproduces contigs of superior fidelity, albeit at greater computational cost. For multiple samples,MEGAHIToffers faster co-assembly [43]. - Parameter Optimization: K-mer length exerts a determinant effect on assembly. Use tools like

KmerGenieto infer the optimal k-mer value for your dataset [43]. - Performance Metrics: A key indicator of successful assembly is the N50 value and the read-mapping rate. One study reported that an optimized assembly pipeline tripled the N50 value and achieved a read-mapping rate of 55.8%, a four-fold enhancement over conventional methods [43].

Q3: How can I isolate rare Actinomycetes from complex environmental samples for BGC discovery?

Isolating rare Actinomycetes requires selective techniques to suppress fast-growing bacteria:

- Sample Pretreatment: Subject environmental samples (e.g., soil, cave sediments) to harsh chemical, heat, or drought conditions. Actinomycete spores are highly resistant, allowing them to germinate under conditions that suppress other bacteria [44].