Shotgun Metagenomics vs. 16S rRNA Sequencing: A Strategic Guide for Microbial Community Profiling in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics for microbial community profiling, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Shotgun Metagenomics vs. 16S rRNA Sequencing: A Strategic Guide for Microbial Community Profiling in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics for microbial community profiling, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of each method, delves into their specific applications and methodological considerations, and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimizing study designs. By synthesizing evidence from recent comparative studies, it presents a clear framework for method selection based on project goals, sample type, budget, and desired analytical outcomes, ultimately aiming to enhance the robustness and discovery potential of microbiome research in biomedical contexts.

Core Principles: Understanding 16S rRNA and Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

What is 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing? Targeting Hypervariable Regions for Bacterial Census

16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing is a cornerstone amplicon-based sequencing method used to identify and classify bacterial and archaeal populations within complex biological samples [1] [2]. This technique leverages the genetic properties of the 16S rRNA gene, a universal and highly informative molecular marker. The gene, approximately 1500 base pairs long, contains a unique structure of nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9) interspersed between conserved regions [1] [2]. The conserved areas allow for universal amplification across a wide spectrum of prokaryotes, while the variable regions provide the sequence diversity necessary for phylogenetic classification and differentiation between species [1]. As such, 16S rRNA sequencing serves as a powerful bacterial census tool, enabling researchers to decipher the composition of microbial communities without the need for cultivation.

The Principle and Utility of Hypervariable Regions

The power of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for taking a bacterial census hinges on the specific function of the hypervariable regions. While the entire gene is used for phylogenetic studies, high-throughput sequencing platforms often target specific variable regions due to read length limitations [3]. Different hypervariable regions possess distinct resolving powers for taxonomic identification, which can vary depending on the sample type and bacterial species present [4].

Table 1: Characteristics of 16S rRNA Hypervariable Regions

| Hypervariable Region | Key Characteristics and Taxonomic Utility |

|---|---|

| V1-V2 | Shown to have high resolving power for identifying respiratory bacterial taxa; effective for discriminating Streptococcus sp. and Staphylococcus species [4]. |

| V3-V4 | One of the most commonly targeted regions; provides a balance of information and amplicon length compatible with Illumina MiSeq [5]. |

| V4 | Highly conserved with ribosome functionality; a frequent single-target region for diversity studies [4]. |

| V5-V7 | Exhibits compositional similarity to V3-V4 in community analyses [4]. |

| V7-V9 | Often shows lower alpha diversity and richness compared to other region combinations [4]. |

No single hypervariable region can perfectly resolve all bacterial taxa, which has led to the common practice of sequencing multiple regions in tandem [6]. A study comparing combinations of regions in respiratory samples found that the V1-V2 combination exhibited the highest sensitivity and specificity for accurate taxonomic identification [4]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that integrating data from multiple hypervariable regions using statistical models, such as generalized linear models, enhances the statistical evaluation of differences in community structure and relatedness among sample groups [6].

For the highest level of taxonomic resolution, full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing is superior. Advances in long-read sequencing technologies, like Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) circular consensus sequencing (CCS), enable the sequencing and error-correction of the entire ~1.5 kb gene. This approach overcomes the limitations of short-read sequencing, providing species-level classification with high accuracy [3].

16S rRNA Sequencing vs. Shotgun Metagenomics

Within the context of microbial community profiling, 16S rRNA sequencing is a fundamental alternative to shotgun metagenomics. The choice between these two methods depends heavily on the research question, as each has distinct strengths and limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of 16S rRNA Sequencing and Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

| Feature | 16S/ITS Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Target | Amplifies specific 16S rRNA (bacteria/archaea) or ITS (fungi) gene regions [7] [8] | Sequences all genomic DNA in a sample randomly [7] [8] |

| Taxonomy Resolution | Genus- to species-level (with full-length 16S or DADA2) [8] [3] | Species- to strain-level [8] |

| Cross-Domain Coverage | No (domain-specific) [8] | Yes (bacteria, fungi, viruses, etc.) [8] |

| Functional Profiling | Limited to prediction (e.g., PICRUSt), not direct assessment [8] | Yes, direct identification of microbial genes and pathways [7] [8] |

| False Positive Risk | Low (with modern error-correction like DADA2) [8] | High (due to database dependencies and shared sequences) [8] |

| Host DNA Interference | Minimal impact [8] | Significant problem; may require host DNA depletion [8] |

| DNA Input | Very low (as low as 10 gene copies) [8] | Higher (typically ≥1 ng) [8] |

| Cost per Sample | Lower [8] | Higher [8] |

A prospective clinical comparison demonstrated that shotgun metagenomics had a significantly better performance for bacterial detection at the species level compared to Sanger sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene in culture-negative samples [9]. However, the analysis of mock microbial communities has shown that 16S rRNA sequencing with error-correction algorithms like DADA2 can achieve high accuracy with no false positives, whereas shotgun metagenomics is more susceptible to false positives if reference databases are incomplete [8].

Experimental Protocol for a Typical 16S rRNA Sequencing Study

The following workflow outlines the standard methodology for a 16S rRNA gene sequencing study, from sample collection to data analysis.

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for a 16S rRNA gene sequencing study.

Detailed Methodologies

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Microbial samples are collected from the environment of interest (e.g., soil, water, human gut via swab or biopsy). The samples are then processed to isolate total genomic DNA. This step often involves physical and chemical lysis of cells, followed by purification to remove contaminants that could inhibit downstream reactions [1] [5]. Including mock microbial community controls is strongly recommended to determine the efficacy of DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing [5].

PCR Amplification and Library Construction: The isolated DNA is used as a template to amplify the 16S rRNA gene via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Primers are designed to bind to conserved regions flanking one or more hypervariable regions (e.g., V3-V4, V1-V2). The choice of primers is critical, as it can influence which bacterial taxa are preferentially amplified [7]. The PCR products are then prepared for sequencing by attaching platform-specific adapters and sample barcodes (multiplexing indices) to allow for pooling of multiple samples in a single sequencing run [1] [2].

Sequencing: The constructed libraries are sequenced using high-throughput platforms. The most common is the Illumina MiSeq system, which is well-suited for paired-end sequencing of amplicons targeting regions like V3-V4 [2]. For full-length 16S sequencing, long-read technologies like Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) are employed. PacBio's circular consensus sequencing (CCS) allows for multiple passes of a single molecule, generating highly accurate long reads (~1.5 kb) that encompass all nine hypervariable regions [3].

Bioinformatic Analysis: The raw sequencing data is processed using specialized pipelines to determine taxonomic composition. A standard tool is QIIME2 (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2) [5]. Key steps include:

- Demultiplexing: Assigning sequences to their sample of origin based on barcodes.

- Denoising & Quality Filtering: Removing low-quality sequences and correcting errors using algorithms like DADA2 or Deblur. This process resolves exact Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), which differentiate sequences that vary by even a single base pair, providing higher resolution than older Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) clustering methods [5] [4].

- Taxonomic Assignment: ASVs are compared to reference databases (e.g., Greengenes, SILVA, HOMD) to assign taxonomic identities from phylum to species level [5].

Statistical and Ecological Analysis: The final output, a table of ASVs and their abundances across samples, is analyzed statistically. Common analyses include:

- Alpha Diversity: Metrics like the Shannon index summarize the within-sample diversity, combining species richness and evenness [5].

- Beta Diversity: Metrics like Bray-Curtis dissimilarity quantify the differences in microbial community composition between sample groups [5]. Visualization via ordination plots (e.g., NMDS) helps identify patterns.

- Differential Abundance: Statistical models, such as the Linear Decomposition Model (LDM), are used to identify specific taxa that are significantly more or less abundant between experimental groups while controlling for multiple hypotheses testing [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for 16S rRNA Sequencing Experiments

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Mock Microbial Community | A defined mix of microbial strains from a commercial source (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS). Serves as a critical positive control to evaluate the accuracy of the entire workflow, from DNA extraction to taxonomic classification [5] [4]. |

| Primers Targeting Hypervariable Regions | Specific oligonucleotide pairs (e.g., for V3-V4, V1-V2) used in PCR to amplify the 16S rRNA gene from the sample DNA. The choice of primer pair directly impacts which bacteria are detected [7] [4]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | An enzyme used for PCR amplification that has low error rates, ensuring accurate replication of the 16S rRNA gene sequences prior to sequencing. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | A commercial kit that provides the necessary reagents for fragmenting (if needed), indexing, and preparing the amplified DNA for sequencing on a specific platform (e.g., Illumina, PacBio) [2]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines (QIIME2, MOTHUR) | Open-source software packages that provide a comprehensive set of tools for processing raw sequencing data, performing quality control, denoising, taxonomic assignment, and basic statistical analysis [1] [5]. |

| 16S Reference Databases (SILVA, Greengenes) | Curated databases of high-quality 16S rRNA gene sequences from known bacteria. These are essential for assigning taxonomic labels to the unknown sequences obtained from the sample [5]. |

16S rRNA gene sequencing, centered on the analysis of hypervariable regions, remains an indispensable and powerful method for conducting a bacterial census in diverse environments. Its cost-effectiveness, sensitivity, and well-established protocols make it ideal for large-scale studies focused on answering "who is there?" in a microbial community. The choice of which hypervariable region(s) to target is critical and should be informed by the specific ecological niche under investigation. While shotgun metagenomics offers a broader functional potential and higher taxonomic resolution in some cases, 16S sequencing provides a robust, accessible, and highly accurate approach for taxonomic profiling, particularly when leveraging full-length sequencing and modern error-correction bioinformatics.

In the field of microbial community analysis, researchers primarily rely on two powerful sequencing approaches: 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing. While 16S sequencing has been a workhorse for phylogenetic studies for decades, shotgun metagenomics represents a paradigm shift towards comprehensive, unbiased genomic analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and applications in diagnostic and research settings.

What is Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing?

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing is a next-generation sequencing approach that involves randomly fragmenting all genomic DNA in a sample into small pieces, sequencing these fragments, and then computationally reconstructing the sequences to identify microorganisms and their functional genes [10] [7]. Unlike targeted methods, it sequences all genetic material without prejudice, allowing researchers to comprehensively sample all genes from all organisms present in a complex sample [10] [11].

This method enables microbiologists to evaluate bacterial diversity and detect microbial abundance across various environments, while also providing a means to study unculturable microorganisms that are otherwise difficult or impossible to analyze [10]. By capturing the entire genetic content of a microbial community, shotgun metagenomics offers unprecedented insights into community biodiversity and function.

Head-to-Head Comparison: Shotgun Metagenomics vs. 16S rRNA Sequencing

The table below summarizes the core differences between shotgun metagenomics and 16S rRNA sequencing based on current literature and experimental data:

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Shotgun Metagenomic and 16S rRNA Sequencing

| Parameter | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing | 16S rRNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Approach | Random fragmentation and sequencing of all genomic DNA [7] [12] | Targeted amplification of hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene [13] [7] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Species to strain level [8] | Genus to species level [9] [8] |

| Microbial Domains Covered | Bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms [7] [12] | Primarily bacteria and archaea only [7] [12] |

| Functional Profiling Capability | Yes - can identify metabolic pathways and antibiotic resistance genes [9] [8] | Limited - requires inference tools like PICRUSt [8] |

| Detection of Polymicrobial Infections | Excellent - can identify multiple pathogens simultaneously [9] | Limited - poorly adapted for more than one bacterial species per primer pair [9] |

| Quantitative Accuracy | Semi-quantitative with better abundance measurements [9] [14] | Less reliable due to amplification biases and varying 16S copy numbers [14] [15] |

| Species Identification Rate | 46.3% (significantly higher at species level) [9] | 38.8% (lower at species level) [9] |

| Cost per Sample | ~$200 (standard), ~$120 (shallow) [8] | ~$80 [8] |

| DNA Input Requirement | 1 ng minimum [8] | As low as 10 copies of 16S rRNA gene [8] |

| Host DNA Interference | Significant issue, may require depletion strategies [8] | Minimal impact due to targeted amplification [8] |

| Computational Demands | High - requires extensive processing power [7] [11] | Moderate - established, streamlined pipelines [13] |

Experimental Evidence and Performance Data

Recent clinical studies have directly compared the diagnostic performance of these methodologies. A 2022 prospective study comparing both methods on 67 clinical samples found that shotgun metagenomics identified a bacterial etiology in 46.3% of cases compared to 38.8% with Sanger 16S [9]. This difference was particularly notable at the species level, where shotgun metagenomics significantly outperformed 16S sequencing (28/67 vs. 13/67 cases) [9].

For taxonomic classification, shotgun metagenomics has demonstrated superior resolution. A freshwater microbiome study found that while 16S rRNA gene sequencing captured broad shifts in community diversity over time, metagenomic data identified 1.5 times as many phyla and approximately 10 times as many genera compared to 16S amplicon sequencing [15].

Methodologies and Technical Protocols

Shotgun Metagenomics Workflow

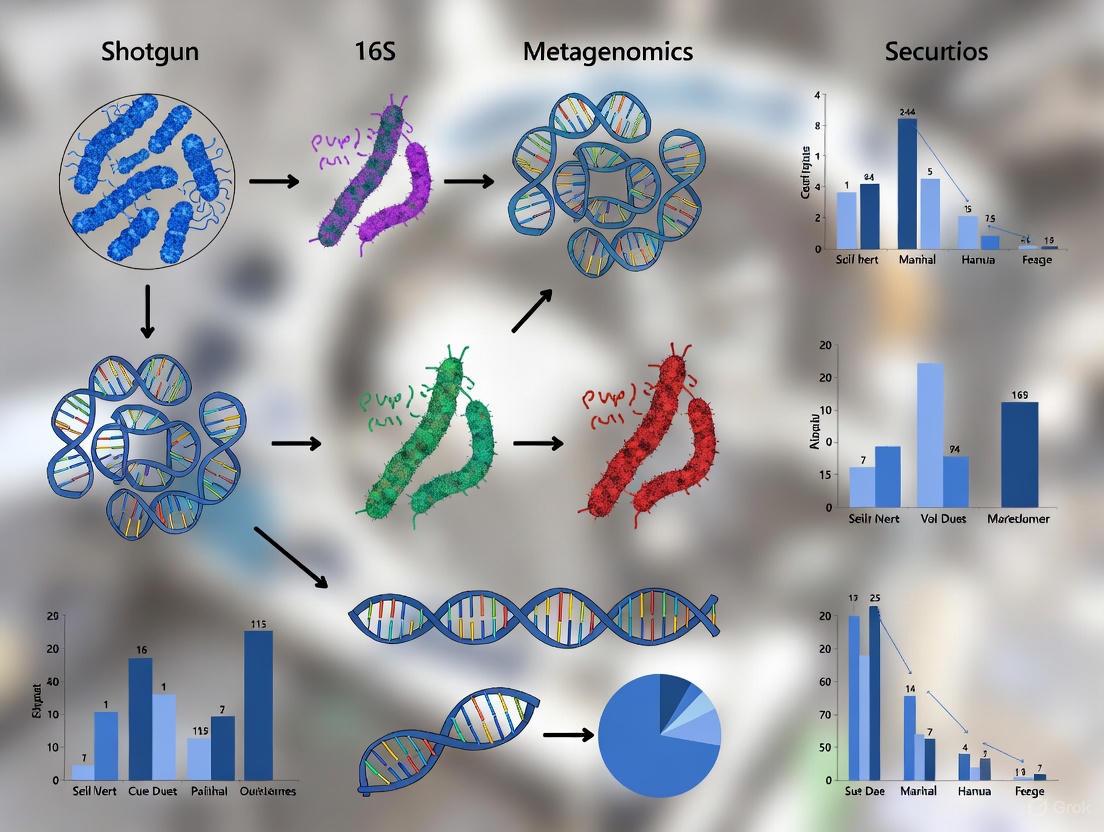

Figure 1: Shotgun metagenomics workflow from sample to analysis.

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction: The process begins with sample collection from various environments or biological reservoirs. DNA is extracted using commercial kits such as MoBIO DNA Extraction Kit, Qiagen DNA Microbiome Kit, or Epicentre Metagenomic DNA Isolation Kits [14]. For host-associated samples, physical fractionation or selective lysis may be employed to minimize host DNA contamination [14].

Library Preparation: For samples with sufficient DNA material (250-500 ng), amplification-free library preparation methods are recommended to avoid PCR biases. Commonly used kits include Bioo Scientific NEXTflex PCR-Free DNA Sequencing Kit, Illumina TruSeq PCR-Free Library Preparation Kit, or Kapa Hyper Prep Kit [14]. For low-input samples, PCR amplification is necessary but can introduce quantitative biases.

Sequencing Platforms: Illumina platforms (MiSeq, HiSeq, NovaSeq) are widely used for shotgun metagenomics, providing 2x150 bp to 2x300 bp read lengths with high sequencing depth [13] [14]. Long-read technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore can improve assembly statistics but come with higher error rates and costs [14]. Hybrid approaches combining Illumina and PacBio reads are increasingly used for improved assembly quality [14].

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control: Raw reads are trimmed and filtered using tools like Trimmomatic or FastQC

- Host DNA Removal: Alignment to host genome and removal of matching reads

- Assembly: De novo assembly using tools such as MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes

- Taxonomic Classification: Marker-based (MetaPhlAn) or alignment-based (Kraken2) methods [8]

- Functional Annotation: Comparison to databases like KEGG, SEED, or EggNOG [14]

16S rRNA Sequencing Workflow

Figure 2: 16S rRNA gene sequencing workflow with targeted amplification.

Targeted Amplification: 16S sequencing uses PCR to amplify specific hypervariable regions (V1-V9) of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. The selection of variable regions (e.g., V3-V4, V4, V6-V8) impacts taxonomic resolution and requires careful primer selection [7].

Limitations: This approach suffers from PCR amplification biases, primer specificity issues, and varying copy numbers of the 16S gene between taxa, which affects quantitative accuracy [9] [14]. It also has limited resolution for certain bacterial genera like Staphylococci and Enterococci [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Metagenomic Studies

| Product Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | MoBIO DNA Extraction Kit, Qiagen DNA Microbiome Kit, Epicentre Metagenomic DNA Isolation Kit [14] | High-quality nucleic acid extraction from complex samples while preserving microbial diversity |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina TruSeq PCR-Free Library Prep, Bioo Scientific NEXTflex PCR-Free Kit, Kapa Hyper Prep Kit [14] | Preparation of sequencing libraries without amplification bias |

| Host DNA Depletion Kits | HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit [8] | Reduction of host DNA contamination in host-associated samples |

| Automated Extraction Systems | QIAcube (Qiagen), Maxwell RSC (Promega), KingFisher (Thermo Fisher) [13] | Walk-away DNA extraction for high-throughput laboratories |

| Taxonomic Profiling Tools | Kraken2, MetaPhlAn, mOTU [8] | Bioinformatics tools for taxonomic classification of sequencing data |

| Functional Databases | KEGG, SEED, MetaCyc, EggNOG, Pfam [14] | Reference databases for functional annotation of metagenomic sequences |

Advantages and Limitations in Clinical Diagnostics

Shotgun Metagenomics Strengths

Shotgun metagenomics provides comprehensive pathogen detection beyond bacteria to include fungi, viruses, and parasites [7] [12]. It enables functional characterization of microbial communities, including identification of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors, which is impossible with 16S sequencing alone [9]. The method also offers superior detection of polymicrobial infections and better discrimination at the species level for challenging taxonomic groups [9].

Shotgun Metagenomics Limitations

The technology remains cost-prohibitive for many laboratories, approximately 2-3 times more expensive than 16S sequencing [8]. It generates massive datasets that require substantial computational resources and bioinformatics expertise [11]. Results are highly dependent on reference databases, which remain incomplete for many non-human microbiomes [8]. The approach is also vulnerable to host DNA contamination, particularly in low-microbial-biomass samples [8].

16S Sequencing Strengths

16S sequencing remains significantly more cost-effective, making it accessible for larger-scale studies [8]. It has well-established protocols and bioinformatics pipelines that are accessible to laboratories with limited computational resources [13]. The method is less affected by host DNA contamination due to targeted amplification [8]. Extensive reference databases provide good coverage for diverse environments beyond human-associated microbiomes [8].

Future Perspectives

As sequencing costs continue to decline and computational methods improve, shotgun metagenomics is poised to become more accessible for routine diagnostic use [9]. The development of shallow shotgun sequencing approaches provides a middle ground, offering higher discriminatory power than 16S sequencing at lower cost than deep shotgun sequencing [10] [8].

Automation of both wet-lab and computational workflows will further bridge the implementation gap, particularly in middle-income countries where infrastructure limitations currently present significant challenges [13]. The integration of long-read technologies promises to overcome current limitations in assembly quality, potentially enabling complete genomic reconstruction of unculturable microorganisms directly from complex samples [14].

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing represents a powerful, comprehensive approach for microbial community analysis that surpasses the limitations of targeted 16S rRNA gene sequencing. While 16S sequencing remains valuable for phylogenetic studies and large-scale biodiversity surveys, shotgun metagenomics offers superior taxonomic resolution, functional insights, and detection of diverse microorganisms across all domains of life.

The choice between these technologies should be guided by research objectives, budget constraints, and computational resources. For clinical diagnostics where comprehensive pathogen detection and functional characterization are critical, shotgun metagenomics demonstrates clear advantages despite its higher complexity and cost. As the field continues to evolve, shotgun metagenomics is increasingly positioned to become the gold standard for unbiased microbial community profiling in both research and diagnostic settings.

In the field of microbial community profiling, the choice of library preparation method fundamentally shapes the scope and resolution of research findings. Two principal workflows have emerged: PCR amplification of specific marker genes, such as in 16S rRNA sequencing, and random fragmentation of genomic DNA, as utilized in shotgun metagenomic sequencing. The decision between these methods carries significant implications for taxonomic resolution, functional insight, and technical reproducibility. This guide objectively compares these core methodologies, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal approach for their specific research questions within microbial ecology and therapeutic development.

Methodological Comparison and Workflow

PCR Amplification Workflow (16S rRNA Sequencing)

The PCR amplification workflow centers on targeted amplification of conserved genomic regions to profile microbial communities. In 16S rRNA sequencing, this involves amplifying the 16S ribosomal RNA gene, which contains conserved regions for phylogenetic analysis and variable regions for differentiating species [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Acquisition and DNA Extraction: Specimens are collected from environmental or biological sources (e.g., gut, soil, water). Microbial DNA is extracted, ensuring the preservation of bacterial DNA integrity [7].

- Targeted PCR Amplification: The 16S rRNA gene undergoes amplification using primers specific to conserved regions that flank variable regions (e.g., V3-V4, V4, V6-V8). The choice of primers is critical, as it can influence preferential amplification of certain bacterial taxa [7].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The amplified 16S rRNA genes are prepared for sequencing on platforms like Illumina MiSeq. A typical PCR reaction includes [16]:

- Template DNA: 1–1000 ng (approximately 10^4 to 10^7 molecules).

- Primers: 20–50 pmol of each primer, designed to be 15–30 bases long with 40–60% G-C content and a melting temperature (Tm) between 52–58 °C.

- PCR Mixture: Includes DNA polymerase (e.g., 0.5 to 2.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase), dNTPs (200 μM of each nucleotide), and a reaction buffer, often with MgCl₂ (1.5 mM final concentration, unless included in the buffer) [16].

- Thermal Cycling: Typically 25–35 cycles of denaturation (e.g., 95°C), primer annealing (temperature determined by primer Tm), and extension (e.g., 72°C) [17].

- Data Analysis: Sequences are processed by removing low-quality reads and trimming adapters. High-quality sequences are grouped into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) based on sequence homology and compared against microbial genomic databases for taxonomic classification [7].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for library preparation via PCR Amplification:

Random Fragmentation Workflow (Shotgun Metagenomics)

In contrast, the shotgun metagenomic sequencing workflow employs random fragmentation of the total genomic DNA extracted from a sample, enabling a comprehensive view of all genetic material present [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Acquisition and DNA Extraction: Similar to the start of the 16S workflow, this step aims to isolate total DNA from all microorganisms (bacteria, archaea, viruses, fungi) without bias [18].

- Random DNA Fragmentation: The extracted high molecular weight DNA is physically or enzymatically broken into small, random fragments. Common methods include [19] [20]:

- Nebulization: Forces DNA through a small hole using compressed gas, producing a heterogeneous mix of fragments with 3′-/5′-overhangs or blunt ends.

- Sonication: Subjects DNA to ultrasonic waves, using gaseous cavitations to shear molecules.

- Enzymatic Fragmentation: Uses a mix of enzymes (e.g., NEBNext dsDNA Fragmentase) to randomly generate nicks and cuts in dsDNA, producing fragments of 100–800 bp.

- Library Preparation: Fragmented DNA undergoes end-repair, adapter ligation, and is often PCR-amplified to enrich for fragments with adapters on both ends [19] [21]. Note: Amplification-free protocols exist to reduce artifacts, particularly for challenging sequences like short tandem repeats [22].

- Sequencing and Assembly: All fragments are sequenced using high-throughput platforms. The resulting reads can be assembled into partial or complete microbial genomes (Metagenome-Assembled Genomes, MAGs) or aligned directly to reference databases [7].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for library preparation via Random Fragmentation:

Performance and Data Comparison

A systematic, multicenter evaluation highlights the distinct performance characteristics and data outputs of these two methods [18].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Method Performance

| Feature | PCR Amplification (16S rRNA Sequencing) | Random Fragmentation (Shotgun Metagenomics) |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Scope | Bacteria and Archaea only [7] | All domains: Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi [7] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Typically genus-level, sometimes species-level [7] | Species-level and strain-level possible [18] [7] |

| Functional Insight | Limited to inference from taxonomy | Direct profiling of microbial genes and metabolic pathways [7] |

| Quantification Accuracy | Subject to primer bias and amplification artifacts [18] [7] | More quantitative, though can be affected by genome size and DNA extraction [18] |

| Sensitivity to Low-Abundance Taxa | Lower; can miss rare species due to amplification bias | Higher; better at detecting low-abundance bacteria (e.g., B. bifidum) [18] |

| Inter-laboratory Reproducibility | Higher variability; 46.2% of labs reported significant correlations with expected mock community composition [18] | Better reproducibility; 82.6% of labs reported significant correlations with expected results [18] |

| Cost and Throughput | Generally lower cost per sample; high-throughput [7] | Higher cost per sample due to greater sequencing depth required [7] |

Impact of Technical Variations

The multicenter assessment revealed that methodological choices introduce significant variability. For 16S sequencing, the choice of DNA extraction method, PCR amplified regions, and bioinformatics tools were identified as important factors causing inter-laboratory deviations in observed microbial abundances [18]. For example, reported abundances for specific taxa like Bacteroides spp. varied from 0.3% to 53.5% across different laboratories [18]. Shotgun metagenomics is also susceptible to biases from DNA extraction and bioinformatics analysis, though it demonstrated superior reproducibility in the multicenter study [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Library Preparation

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primers (16S) | Target and amplify hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene [7]. | Selection of variable region (e.g., V3-V4, V4) is critical and can introduce bias [7]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that catalyzes the template-dependent synthesis of DNA during PCR [16]. | Thermostable; requires optimization of concentration and MgCl₂ levels for specific templates [16]. |

| Nebulization / Sonication Systems | Physical shearing of DNA into random fragments for shotgun sequencing [19] [20]. | Produces a heterogeneous mix of fragment sizes; requires optimization of time/pressure [19]. |

| Enzymatic Fragmentation Kits | Enzyme-based random digestion of DNA into fragments of defined size ranges [19] [20]. | Highly consistent between preparations; may slightly increase indel errors in raw reads compared to physical methods [19] [20]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers | Random barcodes added to each DNA fragment prior to amplification [21]. | Allows bioinformatic distinction between PCR duplicates and natural read duplicates, improving quantification accuracy [21]. |

The choice between PCR amplification and random fragmentation is not a matter of which method is universally superior, but which is optimal for a specific research context.

- PCR Amplification (16S rRNA Sequencing) is a powerful, cost-effective tool for high-throughput surveys of bacterial and archaeal composition, ideal for large-scale studies where broad taxonomic profiling is the primary goal and budget is a constraint.

- Random Fragmentation (Shotgun Metagenomics) provides a comprehensive view of the entire microbiome, delivering superior taxonomic resolution, functional insights, and reproducibility, which is crucial for hypothesis-driven research, therapeutic development, and when studying non-bacterial community members.

Researchers must weigh the trade-offs between resolution, breadth, cost, and technical robustness. As microbiome research advances towards functional understanding and diagnostic application, shotgun metagenomics is increasingly becoming the gold standard, though 16S sequencing remains a highly valuable tool for defined applications.

The analysis of microbial communities has been revolutionized by culture-independent, next-generation sequencing techniques. The two predominant strategies, marker-gene analysis (e.g., 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing) and whole-genome shotgun metagenomics, offer distinct approaches and insights [23]. Marker-gene analysis provides a cost-effective census of community membership, primarily for bacteria and archaea, by sequencing a single, phylogenetically informative gene. In contrast, shotgun metagenomics sequences all the DNA in a sample, enabling a higher-resolution taxonomic profile and direct access to the functional potential of the entire community, including viruses, fungi, and eukaryotes [24] [25]. The choice between these methods, and the subsequent selection of bioinformatics pipelines, fundamentally shapes the biological questions a researcher can address. This guide objectively compares these approaches, framed within the broader thesis of microbial community profiling, and provides supporting experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Analytical Units: OTUs vs. ASVs in Marker-Gene Analysis

In 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing, the initial data processing involves grouping sequences into analytical units. For years, the standard was the Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU).

Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs)

OTUs are clusters of sequences, typically defined by a 97% similarity threshold, intended to approximate species-level groupings [26]. This method groups sequences based on this arbitrary cutoff, which can smooth over sequencing errors but also results in a loss of resolution by potentially merging closely related yet distinct organisms [26].

Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs)

Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) represent a higher-resolution alternative, distinguishing sequence variants at a single-nucleotide level [27]. Generated by error-correcting algorithms like DADA2 and Deblur, ASVs are exact, reproducible sequences that avoid arbitrary clustering thresholds [27] [26]. This provides finer taxonomic discrimination and improved reproducibility across studies, though it can be computationally more intensive [26].

Table 1: Comparison of OTU and ASV Approaches in 16S rRNA Analysis.

| Feature | OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit) | ASV (Amplicon Sequence Variant) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Cluster of sequences based on a similarity threshold (e.g., 97%) | Exact, error-corrected sequence without clustering |

| Resolution | Lower (cluster-level) | High (single-nucleotide) |

| Error Handling | Errors can be absorbed into clusters during sequencing | Uses probabilistic models (e.g., DADA2) to correct errors |

| Reproducibility | May vary between studies and clustering parameters | Highly reproducible across studies |

| Computational Demand | Less computationally intensive | More computationally demanding |

| Primary Advantage | Error tolerance and computational simplicity | High resolution and reproducibility |

Shotgun Metagenomics: A Whole-Genome Approach

Shotgun metagenomics bypasses the amplification of a single gene, instead subjecting all community DNA to random fragmentation and high-throughput sequencing [23]. This approach provides two critical advantages: it avoids the primer bias inherent in 16S amplicon sequencing and provides direct access to the vast repertoire of functional genes within a microbiome [24] [23].

The analysis of shotgun data involves two primary strategies. In reference-based taxonomy profiling, tools like Kraken2 and MetaPhlAn2 align millions of sequenced reads to comprehensive genomic databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) for taxonomic assignment [23]. The resolution and accuracy of this method are directly tied to the quality and diversity of the reference database [23]. Alternatively, de novo assembly reconstructs longer contiguous sequences (contigs) from short reads, which can then be binned into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs). This is powerful for discovering novel species but can be challenging with highly complex communities or genetically similar members [23].

Direct Comparative Analysis: Performance and Experimental Data

Numerous studies have directly compared the taxonomic outcomes of 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics on the same samples, revealing consistent patterns and important distinctions.

Taxonomic Depth and Detection Power

A key finding across multiple studies is that shotgun metagenomics consistently identifies a larger number of species compared to 16S amplicon sequencing [28] [29]. Research on the chicken gut microbiome demonstrated that 16S sequencing detects only a portion of the community revealed by shotgun sequencing, with the latter having more power to identify less abundant, yet biologically meaningful, taxa [28]. A study on human gut microbiomes similarly concluded that shotgun sequencing allows for a much deeper characterization of microbiome complexity [29].

Resolution at Finer Taxonomic Levels

The difference between the two methods becomes more pronounced at finer taxonomic resolutions. A 2023 comparative study on migratory seagulls found that while consistent patterns could be identified by both methods, the results varied significantly as taxonomic levels refined from phylum to species [24]. The largest differences in relative abundance were observed at the species level, where metagenomic sequencing proved more suitable for discovering and detecting specific pathogenic bacteria, such as Escherichia albertii and Salmonella enterica [24]. Pearson correlation analysis in this study confirmed that the correlation coefficient between the two methods gradually decreased with the refinement of taxonomic levels [24].

Table 2: Summary of Key Comparative Studies.

| Study Model | Key Finding: Shotgun Metagenomics | Key Finding: 16S rDNA Sequencing | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migratory Seagulls (Gut) | Identified unique pathogenic species (e.g., S. enterica); higher resolution at species level. | Identified unique taxa like Escherichia-Shigella; correlation with shotgun data decreased at finer taxonomic levels. | [24] |

| Chicken Gut | Revealed a broader community; detected less abundant genera that were biologically meaningful and discriminated experimental conditions. | Detected only part of the community; limited power for less abundant taxa. | [28] |

| Human Gut | Allowed deeper characterization, identifying a larger number of species per sample. | Identified fewer species compared to shotgun sequencing. | [29] |

Functional Insights

A major limitation of 16S amplicon sequencing is its inability to directly profile community function. To address this, bioinformatics tools like PIPHILLIN and PICRUSt2 predict metagenomic functional content from 16S data by leveraging annotated genome databases [30]. A 2020 evaluation showed that PIPHILLIN predictions from DADA2-corrected ASVs strongly correlated with actual shotgun metagenomic data and could identify differentially abundant functional features with high accuracy, even outperforming PICRUSt2 in some metrics [30]. However, these predictions remain inferences of potential function, whereas shotgun sequencing directly characterizes the genes and pathways present [23] [25].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

16S rDNA Amplicon Sequencing Workflow

The standard workflow for 16S sequencing begins with genomic DNA extraction from a sample (e.g., stool). Specific hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene (e.g., V3-V4) are then amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using universal primers [24] [25]. These amplicons are purified, and sequencing adapters/barcodes are added in a second PCR step before being pooled and sequenced on a platform such as the Illumina NovaSeq [24]. The resulting data is processed through a pipeline like QIIME 2 or DADA2, which performs quality filtering, denoising (generating ASVs), and chimaera removal [27]. The final ASV table is used for taxonomic classification against a reference database and subsequent diversity analyses [27].

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing Workflow

For shotgun metagenomics, the total genomic DNA is extracted and then randomly fragmented, typically by sonication, to a size of 350 bp [24]. These fragments are end-repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to Illumina adapters to create a sequencing library without target-specific amplification [24]. The libraries are sequenced on a platform like the Illumina NovaSeq using a paired-end strategy. The bioinformatics workflow involves rigorous quality control and filtering of adapters and low-quality reads using tools like FASTP [24]. Clean reads can then be assembled into contigs using assemblers like MEGAHIT for gene prediction and functional annotation, or they can be directly aligned to reference databases for taxonomic profiling [24].

Figure 1: Comparative workflows for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomics, highlighting key methodological and analytical stages.

Successful microbial community profiling relies on a suite of trusted reagents, software, and databases.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Community Profiling.

| Category | Item/Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Fecal Sample Total Genomic DNA Extraction Kits (e.g., Tiangen) | Standardized isolation of high-quality microbial DNA from complex samples. [24] |

| NEB Next DNA Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from fragmented DNA for shotgun metagenomics. [24] | |

| KAPA HiFi Hot Start Kit | High-fidelity PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene for amplicon sequencing. [24] | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | QIIME 2, DADA2, Deblur | Processing of 16S data: quality control, denoising, and generation of ASV tables. [27] [26] |

| MEGAHIT, MetaGeneMark | De novo assembly of shotgun metagenomic reads and prediction of genes. [24] | |

| MetaPhlAn2, Kraken2 | Taxonomic profiling of shotgun metagenomic sequencing reads. [23] | |

| PIPHILLIN, PICRUSt2 | Prediction of metagenomic functional potential from 16S rRNA amplicon data. [30] | |

| Reference Databases | SILVA, Greengenes | Curated databases of 16S/18S rRNA sequences for taxonomic classification. [27] [23] |

| KEGG, BioCyc | Databases of metabolic pathways and genomic information for functional annotation. [30] | |

| Sequencing Standards | ATCC NGS Standards | Well-characterized reference materials to control for bias and optimize metagenomic workflows. [31] |

The choice between marker-gene and whole-genome analysis is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the research question and resources [26] [25]. 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing remains a powerful, cost-effective method for large-scale epidemiological studies, time-series analyses, and investigations focused primarily on bacterial community composition and dynamics [23]. The move towards ASVs has further strengthened this approach by providing higher resolution and reproducibility [27] [26].

Conversely, shotgun metagenomics is indispensable for studies requiring the highest taxonomic resolution, the discovery of novel organisms, or direct insight into the functional capacity of the microbiome [24] [28] [23]. As sequencing costs continue to decline, shotgun metagenomics is becoming more accessible and is increasingly the preferred method for comprehensive microbiome characterization, particularly in clinical and therapeutic discovery settings where strain-level identification and functional pathways are critical [29] [25].

Future directions in the field point towards the integration of long-read sequencing to improve assembly, the routine combination of multi-omics data (metatranscriptomics, metabolomics), and the development of more efficient algorithms to handle the ever-increasing scale and complexity of microbiome data [27] [23]. For now, a clear understanding of the comparative strengths, limitations, and data generated by OTU/ASV and shotgun metagenomic pipelines is fundamental to robust experimental design and valid biological interpretation in microbial ecology and drug development.

Strategic Application: Choosing the Right Tool for Your Research Question

In the field of microbial ecology, accurately determining the identity and abundance of microorganisms within a complex community is a fundamental objective. The choice of sequencing methodology profoundly impacts the resolution of taxonomic classification, potentially influencing subsequent biological interpretations. This guide provides an objective comparison of two predominant techniques—16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing—focusing on their capabilities for genus-level, species-level, and strain-level identification. The performance of these platforms is evaluated within the context of a broader thesis on microbial community profiling, underscoring that method selection is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with specific research goals, sample types, and resource constraints. [32] [33]

Technical Foundations and Workflows

16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing

This method targets the 16S ribosomal RNA gene, a genetic marker universally present in bacteria and archaea. The gene contains a combination of highly conserved regions, which serve as priming sites for PCR amplification, and nine hypervariable regions (V1-V9), which provide the phylogenetic signal for taxonomic discrimination. [32] The typical workflow involves:

- DNA Extraction: Isolating total genomic DNA from a sample.

- PCR Amplification: Using primers specific to one or more of the hypervariable regions (e.g., V4 or V3-V4).

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Tagging amplicons with sample-specific barcodes, pooling libraries, and performing high-throughput sequencing. [13] [8] The resulting sequences are processed through a bioinformatics pipeline that involves trimming, error-correction (using tools like DADA2), and comparison to curated 16S reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) to generate a taxonomic profile. [8] [34]

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

In contrast, shotgun metagenomics does not target a specific gene but sequences all genomic DNA present in a sample fragment in a non-targeted manner. [32] [8] The workflow consists of:

- DNA Extraction & Fragmentation: Random shearing of all DNA, including microbial, host, and viral.

- Library Preparation: Adding adapters to the fragmented DNA without prior amplification of a specific marker gene.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Generating tens of millions of short reads from the entire metagenome. [8] Bioinformatic analysis is more complex and can follow multiple strategies, including:

- Reference-based taxonomy profiling: Classifying reads against comprehensive whole-genome databases (e.g., RefSeq) using k-mer based classifiers like Kraken2 or alignment tools. [35]

- Marker-gene analysis: Identifying phylogenetic marker genes from the shotgun data with tools like MetaPhlAn. [35]

- Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs): Assembling short reads into longer contigs and binning them to reconstruct draft genomes of uncultured organisms. [35]

The following diagram illustrates the core logical and procedural differences between these two foundational workflows.

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables synthesize key experimental findings and technical specifications from controlled studies and benchmarking reports, providing a quantitative basis for comparing the two methods.

Table 1: Comparative taxonomic resolution and coverage of 16S amplicon and shotgun metagenomic sequencing. [32] [8] [33]

| Performance Metric | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus (potentially species); influenced by targeted regions. [32] | Species and possibly strains/single nucleotide variants. [32] [8] |

| Typical Genus-Level Agreement | High concordance with shotgun data at genus level. [33] | High concordance with 16S data at genus level. [33] |

| Species-Level Identification | ~87.5% for some species; limited by gene variability. [13] | High accuracy and specificity; enabled by whole-genome data. [36] |

| Strain-Level & SNV Identification | Not possible. | Possible with sufficient sequencing depth. [32] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea. [32] | All domains: Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, and Eukaryotes. [32] [8] |

| Risk of False Positives | Low risk with modern error-correction (e.g., DADA2). [8] | High risk if reference database is incomplete; can misassign reads to closely-related genomes. [8] |

| Sensitivity to Host DNA | Minimal impact; PCR targets microbial 16S gene. [32] | Highly sensitive; host DNA can dominate sequencing output, requiring depletion strategies. [32] [8] |

Table 2: Practical considerations for platform selection, based on experimental data and community standards. [32] [8] [37]

| Practical Consideration | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum DNA Input | Very low (femtograms or ~10 copies of 16S gene). [8] | Higher input required (typically ≥1 ng). [8] |

| Recommended Sample Type | All sample types, including low-biomass environments. [8] | Best for human microbiome samples (e.g., feces, saliva) with low host DNA; environmental samples require careful consideration. [8] |

| Cost per Sample (Relative) | ~$80 (Low cost). [8] | ~$200 (Standard) to ~$120 (Shallow). [8] |

| Bioinformatics Complexity | Beginner to intermediate. [32] | Intermediate to advanced. [32] |

| Functional Insights | Limited to prediction from taxonomy (e.g., PICRUSt). [8] | Direct measurement of functional genes and metabolic pathways. [32] [8] |

| Optimal Sequencing Depth | A few thousand reads per sample. [33] | 500,000 (shallow) to 10+ million reads per sample for MAGs. [33] [37] |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To objectively evaluate the performance claims in Tables 1 and 2, researchers often employ controlled experiments using mock microbial communities. The following protocol outlines a standard approach for a comparative study.

Mock Community Construction and Sequencing

- Mock Community Standards: Utilize commercially available, defined mock communities comprising known abundances of bacterial species (e.g., ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard). These provide a ground truth for validating taxonomic classification accuracy and abundance estimation. [8] [35]

- Sample Preparation: Spike the mock community into a sterile matrix relevant to the study (e.g., saline for human samples, sterile soil for environmental samples) to account for potential background interference. [36]

- DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from multiple replicates of the mock community sample using a standardized kit or protocol. This helps control for biases introduced during cell lysis and DNA purification. [35]

- Parallel Library Preparation: For each replicate, split the extracted DNA to prepare both 16S (targeting the V4 region) and shotgun metagenomic sequencing libraries. This direct comparison ensures observed differences are due to the sequencing method and not sample heterogeneity. [36] [33]

- Sequencing: Sequence all libraries on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq or NovaSeq) to a standard depth (e.g., 50,000 reads per sample for 16S and 5 million reads per sample for shotgun). [35]

Bioinformatics and Data Analysis

- 16S Data Processing: Process raw 16S reads through a pipeline like QIIME2 or DADA2 to perform quality filtering, denoising, chimera removal, and amplicon sequence variant (ASV) calling. Assign taxonomy using a reference database (e.g., SILVA). [34] [33]

- Shotgun Data Processing: Analyze shotgun reads using multiple publicly available pipelines to assess robustness. Recommended pipelines include:

- bioBakery4: A suite that includes the MetaPhlAn4 classifier, which uses marker genes and metagenome-assembled genomes for classification. A 2024 benchmarking study found it performed well across multiple accuracy metrics. [35]

- Kraken2/Woltka: K-mer based classifiers that offer high sensitivity. JAMS and WGSA2 pipelines, which use Kraken2, were shown to have among the highest sensitivities. [35]

- Accuracy Assessment: Compare the taxonomic profiles generated by each pipeline to the known composition of the mock community. Key metrics include:

- Sensitivity: The proportion of expected taxa that were correctly identified.

- False Positive Relative Abundance: The proportion of total reads incorrectly assigned to non-constituent taxa.

- Aitchison Distance: A compositionally aware metric that measures the overall difference between the predicted and expected abundance profiles. [35]

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table details key reagents, controls, and software solutions essential for conducting robust experiments in microbial taxonomic profiling.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and tools for microbial community sequencing. [8] [35] [38]

| Item | Function/Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mock Microbial Community | Ground truth control for benchmarking pipeline accuracy and quantifying technical bias. | ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard; ATCC Mock Microbial Communities. [8] [35] |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction System | Standardizes DNA extraction, reduces hands-on time, and minimizes cross-contamination; critical for high-throughput studies. | QIAcube (Qiagen), KingFisher (Thermo Fisher), Maxwell RSC (Promega). [13] |

| Host DNA Depletion Kit | Enriches microbial DNA in samples with high host content (e.g., tissue, blood) for more efficient shotgun metagenomic sequencing. | HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit. [8] |

| 16S rRNA Reference Database | Curated database of 16S sequences used for taxonomic assignment of amplicon data. | SILVA, Greengenes, RDP. [35] [33] |

| Whole-Genome Reference Database | Comprehensive collection of microbial genomes used for classifying shotgun metagenomic reads. | RefSeq, Web of Life (WoL), GTDB. [35] [33] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Software suites for end-to-end analysis of sequencing data, from raw reads to taxonomic and functional profiles. | bioBakery (MetaPhlAn4), JAMS, WGSA2, QIIME2 (for 16S). [35] |

The choice between 16S amplicon and shotgun metagenomic sequencing for taxonomic profiling is a strategic decision dictated by the research question. 16S sequencing is a powerful, cost-effective tool for achieving high-resolution genus-level classification and assessing community diversity across large numbers of samples, particularly when budgets are constrained or sample DNA is limited. [32] [33] Conversely, shotgun metagenomics is indispensable when the research demands species- or strain-level discrimination, comprehensive coverage of all microbial domains, or direct access to the functional potential of the community. [32] [36] Emerging "shallow shotgun" approaches and ongoing benchmarking efforts are making the deeper insights of shotgun sequencing more accessible. [8] [33] [37] Ultimately, a hybrid approach—using 16S for broad-scale surveys and shotgun for deep-dive investigation of key samples—can be a highly effective strategy to maximize scientific return. [32]

Understanding the metabolic capabilities of a microbial community is fundamental to unraveling its role in human health, disease, and ecosystem functioning. In microbial ecology, this process, known as functional profiling, can be approached through two distinct methodologies: one that infers metabolic potential from marker genes and another that directly measures it from the entire genomic content. The choice between these approaches typically hinges on the selection of sequencing technology—16S rRNA gene sequencing for inference and shotgun metagenomic sequencing for direct measurement [8] [7]. Inference-based methods leverage extensive databases and phylogenetic models to predict the functional repertoire of a community based on its taxonomic composition identified from the 16S gene [39]. In contrast, direct measurement via shotgun sequencing captures sequences from all genomic DNA in a sample, allowing for a comprehensive identification of microbial genes and pathways without the need for prediction [40] [7]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two paradigms, focusing on their performance, underlying protocols, and appropriate application within microbial research and drug development.

Performance and Technical Comparison

The performance of inference-based and direct measurement methods varies significantly in terms of resolution, accuracy, and scope. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Comparison of Functional Profiling Methods

| Feature | Inference-Based (e.g., from 16S data) | Direct Measurement (Shotgun Metagenomics) |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Data | 16S rRNA gene sequencing data [8] | Whole-genome shotgun sequencing data [40] [7] |

| Functional Resolution | Prediction of gene families & pathways (e.g., KEGG Orthologs) [39] | Direct identification of gene families & pathways [40] [7] |

| Taxonomic Scope | Bacteria and Archaea only [8] | Bacteria, Archaea, Viruses, Fungi, and other Eukaryotes [41] [7] |

| Sensitivity to Health-Related Changes | Limited sensitivity for subtle, health-related functional changes [39] | High sensitivity to delineate functional changes in health and disease [39] [40] |

| Quantitative Accuracy (Bray-Curtis Dissimilarity) | Lower accuracy compared to shotgun data (e.g., ~67% for pure translated search) [40] | Higher accuracy (e.g., ~89% for tiered search with HUMAnN2) [40] |

| Key Limiting Factors | Quality of reference genomes, annotation, and 16S copy number variation [39] | Depth of sequencing and comprehensiveness of reference databases [8] [7] |

| Cost per Sample (Estimated) | ~$80 [8] | ~$120 (Shallow) to ~$200 (Standard) [8] |

A critical benchmark study that employed matched 16S and metagenomic datasets found that inference tools lack the necessary sensitivity to reliably delineate health-related functional changes in conditions like type 2 diabetes and colorectal cancer [39]. Furthermore, while correlation between inferred and metagenome-derived gene abundances can be high, this metric can be misleading, as high correlations persist even when sample labels are permuted [39].

For shotgun data, tools like HUMAnN2 implement a tiered search strategy that aligns reads to a sample-specific database of pangenomes before performing translated search on unclassified reads. This method has been shown to produce gene family profiles with 89% overall accuracy, compared to 67% for a pure translated search strategy, and does so approximately three times faster [40].

Experimental Protocols for Functional Profiling

Protocol for Inference-Based Functional Profiling

This protocol outlines the process of predicting metabolic pathways from 16S rRNA gene sequencing data using a tool like PICRUSt2.

- Step 1: Input Data Preparation. The process begins with the output of a 16S rRNA analysis pipeline: a table of Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and their associated representative sequences [7].

- Step 2: Phylogenetic Placement. The representative sequences are placed within a reference phylogeny containing genomes with known functional annotations [39].

- Step 3: Hidden State Prediction. An algorithm predicts the gene family content (e.g., KEGG Orthologs) of each ASV/OTU based on the annotated genomes of its phylogenetic neighbors [39].

- Step 4: Metagenome Inference. The predicted gene families for each ASV/OTU are multiplied by their observed abundance in the sample to generate a community-wide metagenome table [39].

- Step 5: Pathway Reconstruction. The abundances of enzyme-coding gene families are used to infer the abundance and completeness of metabolic pathways (e.g., MetaCyc pathways) [39] [40].

- Step 6: Copy Number Normalization (Optional). Some analyses may include a normalization step using databases like rrnDB to account for variation in 16S rRNA gene copy numbers among taxa, which can confound abundance estimates [39].

Protocol for Direct Functional Profiling

This protocol describes the standard workflow for directly quantifying metabolic pathways from shotgun metagenomic data using the HUMAnN2 software as an example [40].

- Step 1: Quality Control & Host Filtering. Raw sequencing reads are quality-trimmed and filtered to remove adapter sequences and host-derived DNA, which can dominate samples from body sites [8] [7].

- Step 2: Taxonomic Profiling. A tool like MetaPhlAn2 is used to rapidly identify the microbial species present in the community and their relative abundances [40].

- Step 3: Tiered Gene Family Search.

- Tier A (Pangenome Mapping): HUMAnN2 builds a sample-specific database from the pangenomes of the species identified in Step 2. All sample reads are aligned to this database using nucleotide-level mapping for fast and accurate assignment [40].

- Tier B (Translated Search): Reads not assigned in Tier A are subjected to translated search against a comprehensive protein database (e.g., UniRef90) to capture functions from novel or uncharacterized organisms [40].

- Step 4: Gene Family & Pathway Quantification. Mapped reads are used to quantify the abundance of gene families. These are then used to reconstruct the abundance of metabolic pathways, reporting the coverage (percentage of pathway steps detected) and abundance [40].

- Step 5: Stratified Output. A key feature of HUMAnN2 is that it stratifies the abundance of gene families and pathways by the contributing species, providing resolution into which organisms are responsible for which functions [40].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the logical steps involved in the two primary functional profiling workflows.

Inference-Based Functional Profiling from 16S Data

Direct Functional Profiling from Shotgun Data

Successful functional profiling, regardless of the chosen method, relies on a foundation of well-characterized reagents, standards, and databases.

Table 2: Key Resources for Functional Profiling Experiments

| Resource | Function in Profiling | Type |

|---|---|---|

| ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard | Validates entire workflow (wet lab and bioinformatics) and controls for false positives/negatives [8]. | Physical Standard |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit | Depletes host DNA from samples to increase microbial sequencing depth in host-associated studies [8]. | Wet-lab Reagent |

| KEGG & MetaCyc Databases | Provide reference metabolic pathways and associated enzymes for functional annotation [39] [42]. | Bioinformatics Database |

| rrnDB Database | Provides accurate 16S rRNA gene copy number information for normalization in inference-based methods [39]. | Bioinformatics Database |

| BioCyc/EcoCyc | Offers highly detailed, organism-specific metabolic reconstructions for model validation and interpretation [42]. | Bioinformatics Database |

| ModelSEED | Enables automated draft reconstruction and simulation of genome-scale metabolic models from annotated genomes [42]. | Bioinformatics Tool |

| METABOLIC | A high-throughput software for profiling functional traits, metabolism, and biogeochemistry in microbial genomes [43]. | Bioinformatics Tool |

Microbial communities are complex ecosystems composed of organisms spanning all domains of life, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, protists, and viruses, all of which interact with each other and their host environment [44]. Traditional microbial ecology often focused narrowly on bacterial components, but contemporary research emphasizes the critical importance of cross-domain interactions for understanding community structure, function, and impact on human health and ecosystems [44] [45]. The choice of analytical methodology significantly influences which members of these communities are detected and characterized, potentially biasing biological interpretations.

This guide objectively compares two fundamental approaches for microbial community profiling: 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing. The former primarily targets bacteria and archaea, while the latter enables a more comprehensive survey of all domains. We frame this comparison within the broader thesis that understanding complex microbial ecosystems requires methodologies capable of capturing their true taxonomic and functional diversity.

Methodological Foundations

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

16S rRNA gene sequencing is an amplicon-based method that leverages the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to target and sequence specific variable regions (e.g., V3-V4, V4) of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene, which is present in all bacteria and archaea [7] [8]. The workflow involves several key stages:

- Sample Collection & DNA Extraction: Samples are acquired from various environments (e.g., gut, soil, water), and DNA is extracted while preserving the integrity of microbial DNA [7].

- PCR Amplification: The 16S rRNA gene region is amplified using primers designed for conserved regions that flank the variable regions, which provide phylogenetic and taxonomic information [7] [8].

- Sequencing: The amplified genes are sequenced using high-throughput platforms like Illumina MiSeq [7].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequences are processed through pipelines that remove low-quality reads, correct errors, and group sequences into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) for taxonomic classification against reference databases [7] [8].

This method is highly sensitive and cost-effective for profiling bacterial and archaeal communities but does not provide information on other microbial domains like fungi or viruses, nor does it directly reveal functional genetic potential [7] [8].

Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing takes a comprehensive, untargeted approach by fragmenting all genomic DNA in a sample into many small pieces, sequencing them randomly, and then using bioinformatics to reconstruct the sequences and identify the organisms and genes present [7] [8]. The standard workflow includes:

- Sample Collection & DNA Extraction: Similar to 16S sequencing, but requires sufficient and high-quality DNA input [7].

- Random Fragmentation & Library Preparation: DNA is randomly sheared into fragments, and adapters are ligated to create sequencing libraries without target-specific amplification [8].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: All DNA fragments are sequenced, generating a vast collection of short reads from the entire metagenome [7].

- Bioinformatic Reconstruction & Profiling: Reads are quality-filtered and can be either directly aligned to reference databases of microbial genomes or marker genes, or assembled into longer contigs and even full genomes to identify species, strains, and functional genes across all domains of life [7] [8].

This method provides a holistic view of the microbiome, enabling simultaneous profiling of bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms, along with insights into the community's functional potential [7] [8].

Visual Comparison of Method Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between these two sequencing approaches, from sample preparation to data output.

Performance Comparison: Capabilities and Limitations

The choice between 16S and shotgun sequencing involves significant trade-offs. The table below summarizes their core performance characteristics based on current methodologies.

Table 1: Comparative performance of 16S rRNA and shotgun metagenomic sequencing

| Feature | 16S/ITS Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria/Archaea Coverage | High [8] | Limited by reference databases [8] |

| Fungal Coverage | Requires separate ITS sequencing [7] [8] | Yes [8] |

| Viral Coverage | No | Yes [8] |

| Cross-Domain Coverage | No (Domain-specific) [8] | Yes [8] |

| Taxonomy Resolution | Genus-to-Species (Strain-level challenging) [8] [46] | Species-to-Strain [8] [46] |

| Functional Profiling | Indirect prediction via databases (e.g., PICRUSt) [8] | Direct assessment of metabolic pathways & genes [7] [8] |

| False Positive Risk | Low risk with error-correction (e.g., DADA2) [8] | High risk from incomplete reference databases [8] |

| Host DNA Interference | Minimal (targeted amplification) [8] | Significant; may require depletion strategies [8] |

| Minimum DNA Input | Low (as low as 10 gene copies) [8] | Higher (typically ≥1 ng) [8] |

| Cost per Sample | ~$80 [8] | ~$200 (Standard), ~$120 (Shallow) [8] |

Key Differentiators in Performance

Cross-Domain Analysis: A principal advantage of shotgun metagenomics is its ability to simultaneously profile all domains—bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses—from a single, untargeted sequencing run [8]. This is crucial for studying cross-domain interactions, where relationships between different types of microorganisms (e.g., fungi and bacteria) are central to the ecosystem's function [44] [45]. In contrast, 16S sequencing is restricted to bacteria and archaea, while detecting fungi requires a separate, targeted ITS sequencing workflow, and viruses are missed entirely [7] [8].

Taxonomic Resolution and Strain-Level Discrimination: Shotgun metagenomics can achieve species- and strain-level resolution because it accesses the entire genome, allowing for the detection of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and gene presence/absence variations [46]. This is critical as strain-level differences can define an organism's functional role, such as distinguishing pathogenic from probiotic E. coli [46]. While 16S sequencing with advanced error-correction algorithms (e.g., DADA2) can reach species-level for many organisms, its resolution is fundamentally limited by the information within the ~1500 bp 16S gene, making strain-level differentiation generally infeasible [8] [46].

Functional Potential vs. Functional Profiling: Shotgun sequencing enables functional profiling by identifying microbial genes present in the community, allowing for the reconstruction of metabolic pathways and prediction of community functions like antibiotic resistance or nutrient cycling [7] [8]. 16S sequencing data can only be used for functional inference via computational tools like PICRUSt, which predict function based on phylogeny, a less direct and accurate approach [8].

Experimental Data and Validation

Supporting Experimental Evidence

Comparative studies provide empirical support for the performance differences outlined above. Key findings include:

Clinical Diagnostic Performance: A 2022 prospective clinical study compared shotgun metagenomics (SMg) to Sanger 16S sequencing (the single-read predecessor to NGS 16S) in 67 clinical samples where cultures were negative. SMg identified a bacterial etiology in 46.3% (31/67) of cases, outperforming Sanger 16S, which identified an etiology in 38.8% (26/67) of cases. The difference was more pronounced at the species level, with SMg identifying significantly more species (28/67) compared to Sanger 16S (13/67) [9].

Revealing Cross-Domain Interactions: Research on mangrove sediments demonstrated the power of a multi-amplicon approach (16S for prokaryotes, ITS for fungi) to reveal ecological roles. This study showed that fungi acted as keystone taxa across all sediment depths, maintaining microbial network topology through cross-domain interactions with bacteria and archaea, even in deep anoxic layers [45]. This critical ecological insight would be missed by a bacteria-centric 16S analysis alone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key research reagents and solutions for microbial community profiling

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit | DNA extraction from complex environmental and clinical samples; efficiently lyses microbial cells and removes PCR inhibitors. | Used in standardized protocols for soil and sediment microbiome studies [45]. |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries from fragmented genomic DNA for shotgun metagenomics on Illumina platforms. | Enables tagmentation-based library construction for high-throughput sequencing [9]. |

| UMD-SelectNA Kit | A semi-automated, CE-IVD marked kit for selective isolation of microbial DNA and subsequent 16S rDNA PCR and Sanger sequencing. | Used in clinical diagnostic studies for targeted bacterial identification [9]. |

| Primers 515F/806R | Amplify the V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA gene for amplicon sequencing. | Standard primer pair for prokaryotic diversity studies [45]. |

| Primers fITS7/ITS4 | Amplify the ITS2 region of the fungal rRNA gene for fungal community profiling (mycobiome). | Essential for complementary fungal analysis when paired with 16S data [45]. |

Choosing the Right Method: A Strategic Guide

The following decision tree synthesizes the comparative data into a practical framework for selecting the appropriate sequencing method based on project goals, sample type, and budget.

The choice between 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomics is fundamental to the scope and resolution of a microbiome study. 16S sequencing remains a powerful, cost-effective tool for focused, large-scale surveys of bacterial and archaeal diversity, especially when budget and sample numbers are high [8]. Shotgun metagenomics, however, is unequivocally superior for comprehensive, cross-domain microbial analysis, providing a holistic view of the community by capturing bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses simultaneously, while also enabling high-resolution strain discrimination and direct functional profiling [44] [8] [46].

The emerging scientific consensus underscores that microbial communities function as integrated networks involving complex interactions across domains [44] [45]. Therefore, while 16S sequencing has its place, research aimed at a truly holistic understanding of microbiome structure, function, and cross-kingdom dynamics should leverage the power of shotgun metagenomic sequencing where resources allow.

For researchers designing microbial community profiling studies, the choice between 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing involves critical trade-offs between budget, data depth, and project scope. While 16S sequencing offers a cost-effective solution for high-throughput bacterial composition analysis, shotgun metagenomics provides superior taxonomic resolution and functional insights at a higher price point. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies to inform experimental design decisions.

Microbial community profiling has been revolutionized by next-generation sequencing technologies, with 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing emerging as the two predominant approaches [47]. The 16S method employs a targeted strategy, using PCR to amplify specific hypervariable regions (V1-V9) of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene, which is found in all Bacteria and Archaea [47] [8]. This amplified DNA is then sequenced, and the resulting data is analyzed using bioinformatics pipelines (QIIME, MOTHUR) to identify and profile the bacteria and archaea present in samples [47]. In contrast, shotgun metagenomic sequencing takes an untargeted approach by randomly fragmenting all DNA in a sample into small pieces, sequencing these fragments, and then using bioinformatics to reconstruct the taxonomic and functional composition [47] [12]. This comprehensive method can identify bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms simultaneously while also providing data on microbial functional potential through gene content analysis [47] [8].

Technical and Financial Comparison

The choice between these methodologies has significant implications for experimental design, data output, and budget allocation. The table below provides a detailed comparison of key technical and financial considerations:

| Factor | 16S rRNA Sequencing | Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per Sample | ~$50-$134 [47] [48] | Standard: ~$150-$535 [47] [48]Shallow: ~$120-$359 [47] [48] [8] |

| Taxonomic Resolution | Genus level (sometimes species) [47] [8] | Species level (sometimes strains) [47] [8] |

| Taxonomic Coverage | Bacteria and Archaea only [47] [12] | All domains: Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, Viruses [47] [12] |

| Functional Profiling | No (only predicted) [47] [8] | Yes (direct assessment of genes) [47] [8] |

| Bioinformatics Requirements | Beginner to intermediate [47] | Intermediate to advanced [47] |

| Sensitivity to Host DNA | Low [47] | High (requires mitigation strategies) [47] [8] |

| Minimum DNA Input | As low as 10 copies of 16S gene [8] | 1 ng minimum [8] |

| Recommended Sample Types | All sample types [8] | Human microbiome samples (especially feces) [8] |

| Throughput Capability | High (lower cost enables more replicates) [47] | Lower (higher cost limits replicate number) [47] |