Single-Cell Techniques for Bacterial Persisters: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Breakthroughs

Bacterial persisters, a subpopulation of dormant, antibiotic-tolerant cells, are a major cause of recurrent and chronic infections, posing a significant challenge in clinical settings.

Single-Cell Techniques for Bacterial Persisters: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Breakthroughs

Abstract

Bacterial persisters, a subpopulation of dormant, antibiotic-tolerant cells, are a major cause of recurrent and chronic infections, posing a significant challenge in clinical settings. This article provides a comprehensive overview of how advanced single-cell technologies are revolutionizing the study of these elusive cells. We explore the foundational biology of persisters and their distinction from resistant bacteria, detail cutting-edge methodological approaches including microfluidics, fluorescent biosensors, and single-cell RNA sequencing, and discuss optimization strategies to overcome technical hurdles. By comparing and validating insights gained from these techniques, we highlight their collective power in uncovering the molecular mechanisms of persistence. This synthesis aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to leverage single-cell analysis for developing novel anti-persister therapies and improving infectious disease treatment outcomes.

Understanding the Persister Phenotype: Why Single-Cell Analysis is Essential

The failure of antibiotic therapy often stems not from conventional genetic resistance, but from the remarkable ability of a subpopulation of bacterial cells to enter a transient, dormant state. Within the context of single-cell bacterial research, it is crucial to distinguish between three key survival phenotypes: antibiotic resistance, antibiotic tolerance, and the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state. Antibiotic resistance is typically defined by heritable genetic changes that enable bacteria to grow in the presence of an antibiotic, quantified by the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [1]. In contrast, antibiotic tolerance and persistence are non-heritable, phenotypic traits that allow bacteria to survive prolonged exposure to lethal antibiotic concentrations without growing [2] [3]. The VBNC state represents a condition where cells are viable and metabolically active but cannot form colonies on routine media that would normally support their growth, and are capable of returning to a culturable state under favorable conditions [2] [4]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on single-cell techniques, provides researchers with clear definitions, quantitative distinctions, and detailed protocols essential for studying these elusive bacterial subpopulations.

Defining the Phenotypes: Resistance, Tolerance, Persistence, and the VBNC State

The following table summarizes the core characteristics that differentiate these key survival strategies.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Bacterial Survival Phenotypes

| Feature | Antibiotic Resistance | Antibiotic Tolerance/Persistence | VBNC State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heritability | Heritable (genetic) | Non-heritable (phenotypic) | Non-heritable (phenotypic) |

| Growth on Media | Grows in drug presence | Cannot grow during drug exposure, but culturable after | Non-culturable on routine media |

| Primary Metric | Increased MIC [1] | Increased MDK (Minimum Duration of Killing) [1] | Loss of culturability, maintained viability [2] |

| Mechanism | Target modification, efflux pumps, enzyme inactivation | Dormancy, slowed metabolism, toxin-antitoxin systems [5] [3] | Profound metabolic shutdown, morphological changes [6] [4] |

| Population | Entire population | A small subpopulation (persisters) or entire population (tolerance) [2] [3] | Can be a large fraction or entire population [2] |

| Resuscitation | Not applicable | Resumes growth upon antibiotic removal | Can resuscitate under specific environmental cues [6] [4] |

The Relationship Between Persisters and VBNC Cells

A critical concept emerging from recent research is that these dormant states are not entirely distinct but may exist on a continuum of dormancy [2]. In this model, VBNC cells are in a deeper state of dormancy compared to persister cells. While both are dormant and exhibit low metabolic activity, the defining difference lies in culturability: persister cells can resume growth on standard laboratory media once the antibiotic is removed, whereas VBNC cells require specific resuscitation conditions to regain culturability [2] [4]. Some researchers have even suggested that "persisters" and "VBNC" cells may be variants of the same phenomenon [4]. The following diagram illustrates this continuum and the environmental triggers that drive bacterial populations between these states.

Quantitative Distinctions and Key Research Metrics

For researchers, quantifying these phenotypes is paramount. The table below outlines the essential experimental parameters and their interpretations.

Table 2: Core Experimental Metrics for Differentiating Survival Phenotypes

| Experimental Metric | Definition & Measurement | Interpretation and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | The lowest antibiotic concentration that prevents visible growth [1]. | A raised MIC indicates antibiotic resistance. Tolerant/persister and VBNC populations do not typically show a change in MIC. |

| Minimum Duration for Killing (MDK) | The time required to kill 99% of the bacterial population at a high antibiotic concentration (>>MIC) [1]. | An increased MDK is the hallmark of tolerance. The biphasic killing curve, with a subpopulation surviving longer, defines persistence [2] [7]. |

| Culturability vs. Viability | Culturability is measured by colony-forming units (CFU). Viability is assessed via methods like PMA-qPCR (see Protocol 2) or fluorescence-based viability kits [8]. | A population with high viability but low or zero culturability is indicative of the VBNC state [2] [8]. |

| Resuscitation Window | The time period during which VBNC cells can revert to a culturable state upon receiving a specific stimulus (e.g., temperature upshift, nutrient addition) [6]. | A defined resuscitation window confirms the VBNC state, distinguishing it from cell death. The window can be extended by certain metabolites like lactate [6]. |

Essential Single-Cell Protocols for Persister and VBNC Research

Protocol 1: Assessing Single-Cell Persister Recovery Kinetics

This protocol, adapted from Wilmaerts et al., details the steps to isolate and study the recovery of persister cells at the single-cell level, which is crucial for understanding the heterogeneity within the persister subpopulation [7].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- LB Medium: Standard lysogeny broth for culturing E. coli.

- Antibiotic Stock Solution: e.g., Amikacin at 10 mg/mL in milli-Q water, filter-sterilized. The specific antibiotic and concentration must be optimized for the bacterial strain.

- 10 mM MgSO₄ Solution: Used for optical density adjustments without promoting bacterial growth.

Procedure:

- Determine MIC: Perform a broth microdilution susceptibility test to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for the antibiotic and bacterial strain being used [7].

- Time-Kill Assay: Treat a stationary-phase culture with a high concentration of antibiotic (e.g., 10x MIC) for a duration determined to reach the "persister plateau," where the killing rate slows significantly. Sample at intervals to monitor the decline in CFU/mL [7].

- Persister Isolation: After antibiotic treatment, wash the cells by centrifugation to remove the antibiotic. Resuspend the cell pellet in fresh, pre-warmed medium.

- Single-Cell Recovery and Monitoring: Serially dilute the persister suspension to a concentration that yields individual cells. Using spectrophotometry or, ideally, single-cell techniques like time-lapse microscopy, monitor the lag time and growth resumption of individual persister cells to quantify heterogeneity in recovery kinetics [7].

Protocol 2: Detection and Quantification of VBNC Cells using PMA-qPCR

This protocol is essential for studying VBNC cells, as it differentiates them from both culturable and dead cells. It is based on methods used for Campylobacter jejuni but can be adapted for other species [8].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Propidium Monoazide (PMA): A DNA-intercalating dye that selectively enters membrane-compromised dead cells. Upon photoactivation, it forms covalent bonds with DNA, inhibiting its amplification in PCR.

- Specific Primers: e.g., primers targeting the rpoB gene for C. jejuni [8].

- DNA Extraction Kit: e.g., Presto Mini gDNA Bacteria Kit.

Procedure:

- Induce VBNC State: Subject a bacterial culture to a specific stressor (e.g., 7% NaCl for osmotic stress, low temperature) until CFU counts on solid media drop to zero.

- PMA Treatment: Add an optimized concentration of PMA (e.g., 20 µM) to the sample and incubate in the dark. Then, expose the sample to a high-intensity halogen light source to photoactivate the dye.

- DNA Extraction and qPCR: Extract genomic DNA from the PMA-treated sample. Perform qPCR with species-specific primers.

- Quantification: The qPCR signal from the PMA-treated, non-culturable sample represents the VBNC population, as PMA has suppressed the signal from dead cells with compromised membranes. The number of culturable cells (CFU/mL) is subtracted from the total viable count (from PMA-qPCR) to estimate the VBNC cell count [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Persister and VBNC Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) | Differentiates viable cells (with intact membranes) from dead cells (with compromised membranes) in molecular assays like qPCR [8]. |

| Viability Stains (e.g., LIVE/DEAD BacLight) | Used in conjunction with flow cytometry or microscopy to visually assess cell membrane integrity and viability at the single-cell level. |

| Specific Resuscitation Signals (e.g., Lactate) | Used to trigger the resuscitation of VBNC cells back to a culturable state. For example, lactate extends the resuscitation window for Vibrio parahaemolyticus [6]. |

| 96-well Microtiter Plates | Standard platform for high-throughput assays, including MIC determinations and growth curve analyses [7]. |

| Filters for Antibiotic Sterilization | 0.22 µm filters for preparing sterile antibiotic stock solutions to avoid contamination [7]. |

The precise distinction between antibiotic resistance, tolerance, persistence, and the VBNC state is fundamental for advancing research into chronic and recurrent bacterial infections. The definitions, quantitative metrics, and single-cell protocols detailed in this application note provide a framework for researchers to accurately identify and characterize these phenotypes. Moving forward, leveraging these tools will be critical for elucidating the molecular mechanisms driving dormancy and for developing novel therapeutic strategies that effectively target all dormant bacterial subpopulations.

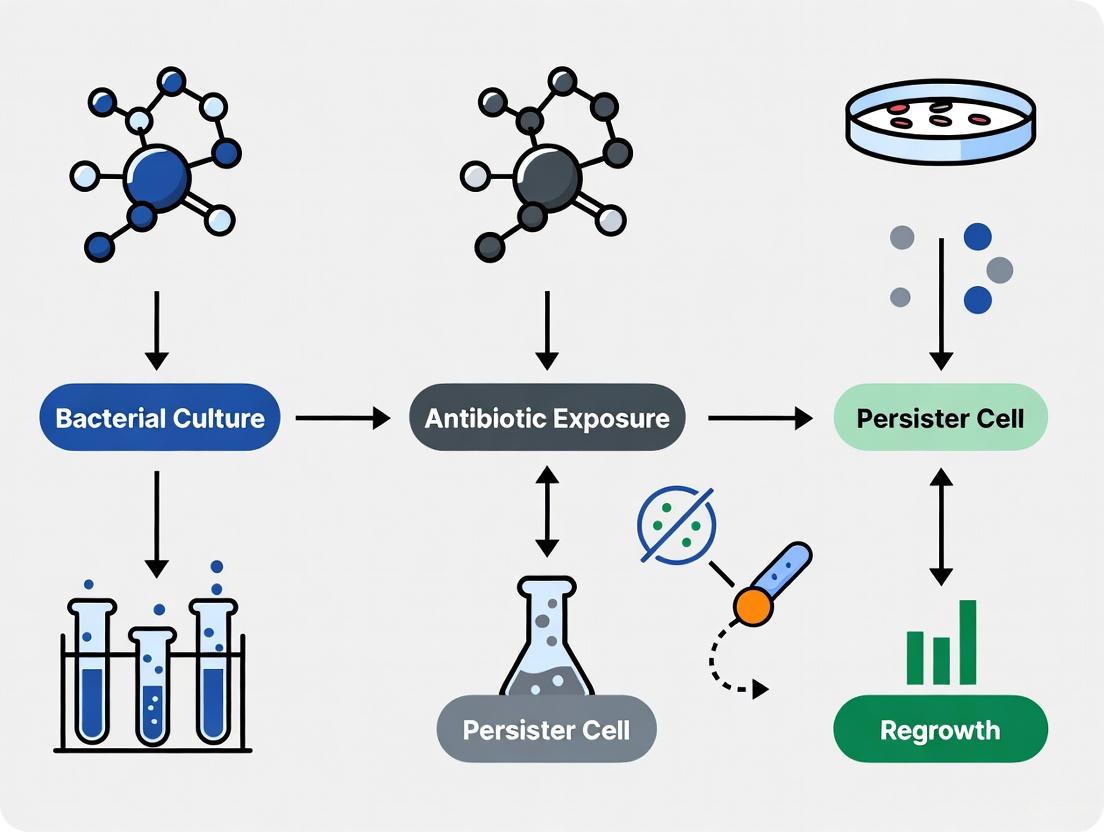

Bacterial persisters represent a non-genetic, phenotypic variant of a bacterial population that exhibits exceptional tolerance to high doses of conventional antibiotics and can regrow once antibiotic pressure is removed [9]. These cells are not antibiotic-resistant, as demonstrated by their unchanged Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) compared to normal cells, but they survive treatment by entering a transient, slow-growing or non-growing dormant state [3] [9]. This phenomenon is a significant clinical concern because persisters are implicated in the recalcitrance of chronic and recurrent infections, leading to treatment failures and prolonged therapeutic courses [10] [11]. They are considered a major culprit behind relapsing infections such as tuberculosis, recurrent urinary tract infections, cystic fibrosis-associated lung infections, and infections linked to biofilms on medical implants [3] [10]. Understanding and targeting persisters is therefore a critical frontier in the fight against persistent bacterial infections. This application note details the core concepts, quantitative profiles, and advanced single-cell methodologies essential for researching this challenging subpopulation of bacteria.

Quantitative Profiling of Bacterial Persisters

A comprehensive understanding of bacterial persistence requires a grasp of its quantitative aspects across different bacterial species, antibiotics, and growth conditions. The following tables consolidate key data from scientific surveys to provide a reference for experimental design and interpretation.

Table 1: Bacterial Pathogens Known to Form Persisters in Clinical Contexts

| Bacterial Species | Associated Disease(s) | Primary Tools for Persister Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Tuberculosis | CFU, Single-Cell Raman Spectroscopy (SCRS), Transcriptomics [9] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Cystic fibrosis lung infections, chronic suppurative otitis media | Colony-Forming Unit (CFU) [9] [11] |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Osteomyelitis, endocarditis, infections of indwelling devices | CFU, Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS), Signature-Tagged Mutagenesis (STM) [9] |

| Escherichia coli | Recurrent urinary tract infections, sepsis | CFU, FACS, Imaging Flow Cytometry (IFC), Microfluidic Culture, Microscopy [9] |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | Lyme disease | CFU, Microscopy [9] |

| Salmonella enterica | Acute gastroenteritis, systemic infections | CFU [9] |

| Candida albicans | Oral, gastrointestinal, and vaginal infections; Septicemia | CFU [9] [11] |

Table 2: Survey of Persister Levels and Influencing Factors

| Factor Category | Observation | Quantitative Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Class | Persistence levels vary significantly by mechanism of action. Membrane-active antibiotics typically yield the fewest persisters [12]. | The median percentage of surviving cells can span five orders of magnitude, from as low as 7 × 10⁻⁴% in P. putida to 100% in E. faecium under certain conditions [12]. |

| Growth Phase | Persister fractions are generally lower in exponentially growing cells and higher in stationary-phase cultures and biofilms [12] [11]. | In E. coli, the proportion of persisters is low during the log phase and increases significantly in the stationary and death phases [11]. |

| Strain Variation | Different strains of the same species can exhibit vastly different persister fractions, and this is often antibiotic-specific [13]. | An E. coli strain may show a high persister fraction with one antibiotic but a low fraction with another, even if the two drugs have similar modes of action [13]. |

| Gram Staining | Persistence is generally observed to be more common in Gram-positive bacteria compared to Gram-negatives [12]. | This observation is based on a broad survey across multiple species and antibiotic treatments [12]. |

Experimental Protocols for Persister Research

Protocol 1: Isolation and Analysis of Persisters via Flow Cytometry and Fluorescent Protein Dilution

This protocol leverages flow cytometry to distinguish and quantify persister, Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC), and dead cell subpopulations following beta-lactam antibiotic treatment [14].

1. Principle: Ampicillin, a beta-lactam antibiotic, primarily kills growing cells by inhibiting cell wall synthesis. Non-growing persister and VBNC cells survive this treatment intact. By pre-loading cells with a fluorescent protein and monitoring its dilution upon resumption of growth, one can track the resuscitation of persisters at the single-cell level [14].

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| E. coli strain with IPTG-inducible fluorescent protein (e.g., mCherry) cassette | Enables tracking of cell division through dilution of the fluorescent protein in daughter cells. |

| Ampicillin | Beta-lactam antibiotic used to lyse growing, sensitive cells and enrich for persisters. |

| IPTG (Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside) | Inducer for the expression of the fluorescent protein. |

| Luria-Bertani (LB) Broth/Agar | Standard culture medium for growing E. coli. |

| Flow Cytometer | Instrument for quantifying and characterizing fluorescent cell populations at high throughput. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) or similar viability stain | Optional; stains dead cells with compromised membranes, providing an additional viability parameter. |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Fluorescent Protein Induction. Inoculate an overnight culture of the reporter strain in LB medium with the appropriate inducer (e.g., IPTG) to ensure high fluorescent protein expression in all cells [14].

- Step 2: Experimental Culture and Antibiotic Treatment. Dilute the overnight culture in fresh, pre-warmed LB medium (with IPTG) and grow to mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ ~0.25). Treat the culture with a lethal dose of ampicillin (e.g., 100 µg/mL) for a sufficient time (e.g., 3 hours) to achieve a biphasic kill curve, ensuring the death of non-persister cells [14].

- Step 3: Wash and Resuscitation. Pellet the cells, wash thoroughly with fresh LB medium to remove the antibiotic and IPTG, and resuspend in fresh LB broth. This step removes the antibiotic pressure and allows persisters to resuscitate.

- Step 4: Flow Cytometry Analysis. Monitor the cells over time using a flow cytometer. Measure forward scatter (FSC, indicative of cell size) and fluorescence intensity.

- Resuscitating Persisters: Cells that begin to divide will dilute their fluorescent protein, showing a decrease in fluorescence intensity over time. Their FSC may also increase due to cell elongation.

- VBNC Cells: These intact, live cells will retain high fluorescence as they do not divide.

- Dead Cells/Debris: Will typically exhibit low FSC and fluorescence [14].

- Step 5: Data Analysis. Calculate the initial number of resuscitating persisters and their doubling time based on the decay of fluorescence and cell count data from the flow cytometer [14].

Figure 1: Flowchart of the flow cytometry-based persister resuscitation protocol.

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Dynamics of Persisters Using Microfluidics

This protocol utilizes microfluidic devices to track the pre- and post-antibiotic exposure history of individual persister cells, providing unparalleled insight into their heterogeneous behaviors [15].

1. Principle: A microfluidic device with a membrane-covered microchamber array (MCMA) traps single cells and small microcolonies, allowing for continuous, high-resolution microscopy. The device permits rapid medium exchange, enabling researchers to observe the same cells before, during, and after antibiotic challenge, directly linking a cell's prior state to its survival outcome [15].

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Microfluidic Device (e.g., MCMA) | Platform for long-term, single-cell imaging under controlled and dynamically changing conditions. |

| Wild-type or Fluorescent Reporter Bacterial Strains | For observation; reporter strains can reveal physiological states (e.g., stress response). |

| Lethal Concentrations of Antibiotics | e.g., Ampicillin (200 µg/mL) or Ciprofloxacin (1 µg/mL) for E. coli MG1655. |

| Controlled Environment Microscope | System for maintaining temperature and conducting time-lapse imaging. |

| Cell Culture Media | Rich (e.g., LB) and/or defined minimal media for growing cells in the device. |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Device Priming and Cell Loading. Prime the microfluidic device with the appropriate growth medium. Load a diluted bacterial culture (from either exponential or stationary phase) into the device, allowing cells to be trapped in the microchambers [15].

- Step 2: Pre-Treatment Imaging. With fresh medium flowing, image the trapped cells for several hours to establish a baseline growth history for each cell. Track parameters like division time, cell size, and morphology.

- Step 3: Antibiotic Exposure. Switch the medium flow to one containing a lethal concentration of antibiotic. Continue time-lapse imaging for the duration of the treatment (e.g., 3-8 hours). Observe the lysis of sensitive cells and the behavior of surviving cells.

- Step 4: Post-Antibiotic Recovery. Switch the flow back to fresh, drug-free medium. Continue imaging for an extended period (e.g., 24-48 hours) to monitor for regrowth (resuscitation) of any surviving persister cells.

- Step 5: Lineage Tracking and Phenotype Classification. Analyze the image data to reconstruct the lineage of every persister cell that regrew. Correlate their post-antibiotic behavior (e.g., continuous growth, growth arrest, filamentation, L-form like morphology) with their pre-antibiotic growth state (growing or non-growing) [15].

Figure 2: Workflow for analyzing persister dynamics using microfluidic single-cell analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table consolidates essential reagents and tools for advanced persister research, as featured in the protocols and literature.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Persister Studies

| Category | Item | Specific Function in Persister Research |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Analysis Platforms | Microfluidic Devices (e.g., MCMA) | Enables long-term, high-resolution tracking of individual cell lineages before, during, and after antibiotic stress [15]. |

| Flow Cytometer | High-throughput quantification and sorting of cell subpopulations based on size, granularity, and fluorescence [9] [14]. | |

| Critical Reagents | Beta-lactam Antibiotics (e.g., Ampicillin) | Used to enrich for persisters by selectively lysing growing, cell wall-synthesizing cells [14]. |

| Fluorescent Protein Reporter Systems (e.g., mCherry, GFP) | Visualize cell growth, division, and physiological states via protein expression and dilution [14] [15]. | |

| Metabolic Inhibitors (e.g., Arsenate) | Used to manipulate cellular ATP levels and study the relationship between metabolism and persistence [14]. | |

| Detection & Viability Tools | Colony-Forming Unit (CFU) Assays | The gold standard for quantifying culturable, resuscitating persister cells [9]. |

| Viability Stains (e.g., Propidium Iodide) | Distinguishes cells with compromised membranes (dead) from those with intact membranes (live) [14]. | |

| Single-Cell Raman Spectroscopy (SCRS) | Provides a label-free biochemical fingerprint of individual cells, useful for identifying dormant states [9]. |

Phenotypic heterogeneity is a fundamental survival strategy in which genetically identical bacterial cells within a clonal population exhibit diverse physiological states. This bet-hedging strategy ensures that a subset of cells, known as persisters, can survive transient environmental stresses such as antibiotic exposure, even though the entire population remains genetically susceptible [16] [17]. These persister cells are typically characterized by a transient, low-metabolism, or dormant state that reduces the efficacy of conventional antibiotics which predominantly target active cellular processes [3] [18]. The clinical significance of persisters is profound, as they underlie the challenges in treating chronic and recurrent infections, including tuberculosis, urinary tract infections, and biofilm-associated infections [3] [17]. Understanding and investigating phenotypic heterogeneity is therefore critical for developing more effective therapeutic strategies against persistent bacterial infections.

This Application Note provides a structured framework for studying bacterial phenotypic heterogeneity and persistence, with a specific focus on single-cell analytical techniques. We summarize current methodologies, provide detailed protocols for key experiments, and outline the essential reagents and tools required for a comprehensive research workflow in this field.

Core Concepts and Classifications

Phenotypic heterogeneity manifests in distinct types of persister cells, primarily classified based on their formation mechanisms. Table 1 summarizes the defining characteristics of the three established types of bacterial persisters.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Bacterial Persister Cells

| Persister Type | Formation Trigger | Metabolic/Growth State | Key Regulatory Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (Triggered) | Environmental stress; Stationary phase [3] [18] | Pre-existing, non-growing [3] [18] | Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) systems, RpoS [3] [19] |

| Type II (Stochastic) | Spontaneous, stochastic process [3] [18] | Slow-growing throughout population lifecycle [3] [18] | (p)ppGpp alarmone, TA systems [3] [20] |

| Type III (Specialized) | Specific antibiotic-induced stress signals [18] | Not necessarily slow-growing; mechanism-specific [18] | e.g., low catalase-peroxidase (for isoniazid persistence) [18] |

The formation and survival of these persister subpopulations are governed by a complex interplay of molecular mechanisms. The stress alarmone ppGpp emerges as a central regulator, integrating various stress signals to induce a multidrug-tolerant state [20]. Its action is often mediated through Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) modules, which function as downstream effectors. In these systems, the toxin component (e.g., MqsR) can disrupt essential processes like translation by cleaving mRNA, promoting dormancy [19] [20]. The general stress response sigma factor RpoS also plays a critical role, with studies showing that suppression of the RpoS-mediated stress response can dramatically increase persistence [19]. Furthermore, other pathways including quorum sensing, drug efflux pumps, and the SOS response to DNA damage contribute to the formation of the persistent state [3] [18]. The following diagram illustrates the relationships between these key mechanisms and their convergence on the persister cell state.

Single-Cell Technologies for Phenotypic Heterogeneity Analysis

Population-averaged measurements often mask rare persister subpopulations. Single-cell technologies are therefore indispensable for dissecting phenotypic heterogeneity. The following table compares the key quantitative applications of major single-cell techniques used in persister research.

Table 2: Single-Cell Technologies for Analyzing Phenotypic Heterogeneity and Persistence

| Technology | Key Measurable Parameters (Quantitative Data) | Typical Persister Frequency Detected | Key Advantages / Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Cytometry | Fluorescence intensity (gene expression), cell size, complexity [17] | N/A | High-throughput analysis and sorting of rare cell populations [16] [17] |

| Microfluidics | Single-cell growth rates, lag time, resuscitation dynamics, real-time gene expression [16] [17] | N/A | Long-term, temporal monitoring of individual cells under controlled conditions [16] |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq) | Global transcriptomes of individual bacteria; 1,000+ transcripts per cell under optimal conditions [21] | N/A | Unbiased discovery of transcriptional states and subpopulations without prior genetic engineering [21] |

| Fluorescent Reporters & Biosensors | Relative mRNA/protein abundance, intracellular ATP levels, metabolite concentrations (e.g., c-di-GMP) [17] | N/A | Dynamic, live-cell imaging of metabolic activity and gene expression heterogeneity [17] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Intracellular biochemical composition at the single-cell level [16] | N/A | Label-free analysis of metabolic state and antimicrobial response [16] |

| Microcolony-seq | Inherited transcriptomic profiles from single progenitor cells [22] | N/A | Links initial single-cell state to downstream phenotypic inheritance and fitness [22] |

Application Note: Tracking Stochastic Persistence with Microfluidics and Fluorescent Reporters

Objective: To investigate the formation and resuscitation of stochastic (Type II) persister cells at the single-cell level.

Background: Type II persisters arise spontaneously in growing cultures without an external trigger. This protocol uses a microfluidic platform to trap and monitor individual cells, coupled with a fluorescent growth reporter to distinguish dormant from active cells.

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Genetically tractable strain of interest (e.g., E. coli).

- Growth Medium: Appropriate liquid and solid media.

- Microfluidic System: Commercially available cell-asay chip or custom-designed PDMS device.

- Fluorescent Reporter: Plasmid or chromosomal fusion of a constitutive promoter to a stable fluorescent protein (e.g., P~const~-GFP).

- Antibiotic: Cidal antibiotic of choice (e.g., ampicillin or ofloxacin).

- Imaging System: Inverted microscope with an environmental chamber (maintained at 37°C), high-resolution camera, and time-lapse capability.

Protocol:

- Strain Preparation: Transform the bacterial strain with the P~const~-GFP reporter construct. Grow an overnight culture in the appropriate medium.

- Chip Priming and Loading: Dilute the overnight culture 1:100 in fresh medium and grow to mid-exponential phase (OD~600~ ≈ 0.3-0.5). Follow the manufacturer's instructions to prime the microfluidic chip with medium. Load the bacterial culture into the chip, allowing cells to be trapped in the growth chambers.

- Pre-Treatment Imaging: Continuously perfuse the chip with fresh, pre-warmed medium. Initiate time-lapse imaging, capturing phase-contrast and fluorescence images of the trapped cells every 15-30 minutes for 2-3 hours to establish baseline growth and fluorescence.

- Antibiotic Treatment: Switch the perfusion medium to one containing the antibiotic at the desired concentration (e.g., 5-10x MIC). Continue time-lapse imaging for the duration of the treatment (e.g., 4-8 hours).

- Post-Treatment Recovery: Switch the perfusion back to fresh, antibiotic-free medium. Continue time-lapse imaging for 12-24 hours to monitor for cell resuscitation and regrowth.

- Data Analysis:

- Growth Rate: Use phase-contrast images to calculate the elongation rate of individual cells before antibiotic treatment.

- Persistence Identification: A cell is classified as a persister if it maintains membrane integrity (does not lyse) during antibiotic exposure but ceases to elongate. Fluorescence intensity should remain stable, indicating a halt in protein synthesis.

- Resuscitation: Identify persister cells that resume elongation and division in the recovery phase. Quantify the lag time (time from antibiotic removal to first division) for each resuscitated persister.

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The ppGpp-Mediated Persistence Pathway

The ppGpp pathway is a central hub regulating the bacterial persistence response. The following diagram details the key molecular players and their interactions leading to the formation of a persistent, multidrug-tolerant cell.

Workflow for Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing of Bacterial Persisters

Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables unbiased transcriptomic profiling of individual bacteria, revealing the heterogeneity within a population. The workflow below outlines the major steps from cell preparation to data analysis, specifically tailored for the challenging task of capturing rare persister cells.

Detailed Protocol Steps:

- Culture & Antibiotic Treatment: Grow the bacterial culture to the desired phase. Treat with a cidal antibiotic at an appropriate concentration (e.g., 5-10x MIC) for a defined period to enrich for, but not exclusively isolate, persisters. Include a viability stain (e.g., propidium iodide) if sorting will be used.

- Single-Cell Isolation: Critically, standard bacterial scRNA-seq requires sorting single cells into multi-well plates containing lysis buffer [21]. Commercial droplet-based systems (e.g., 10x Genomics) are optimized for larger eukaryotic cells and may not be suitable for most bacteria. Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) can be used to sort cells based on specific markers or viability stains.

- Cell Lysis & mRNA Capture: Lyse sorted cells in a buffer containing detergents. For poly(A)-independent transcriptome capture, use random hexamers instead of oligo-d(T) primers during reverse transcription to avoid bias against non-polyadenylated bacterial mRNAs [21].

- cDNA Synthesis & Library Prep: Perform reverse transcription to generate cDNA. Amplify the cDNA using a method like Smart-seq2 for high sensitivity [21]. Prepare sequencing libraries with unique barcodes for each cell to enable multiplexing.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence the libraries on an Illumina platform to a sufficient depth to detect low-abundance transcripts characteristic of dormant cells.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process raw sequencing data (quality control, adapter trimming). Map reads to the reference genome. Generate a gene expression matrix (genes x cells). Perform downstream analyses: clustering, differential expression, and trajectory inference to identify persister subpopulations and their transcriptional signatures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Studying Phenotypic Heterogeneity

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Protein Reporters | Visualizing gene expression heterogeneity and protein localization in live cells [17] | P~const~-GFP for growth reporting; multi-reporter constructs for simultaneous tracking of multiple genes [17] |

| Metabolic Biosensors | Quantifying metabolic activity and metabolite levels at single-cell resolution [17] | "QUEEN" biosensor for intracellular ATP levels; riboswitch-based biosensors for c-di-GMP [17] |

| Viability and Staining Probes | Differentiating live/dead cells and assessing cellular components [17] | SYTOX Green for nucleic acid staining in dead cells; HADA for probing peptidoglycan synthesis [17] |

| Microfluidic Devices | Long-term, high-resolution imaging and manipulation of single cells in controlled environments [16] [17] | Commercial cell-asay chips or custom PDMS devices for antibiotic exposure and recovery studies |

| scRNA-seq Kits & Reagents | Profiling the global transcriptome of individual bacterial cells [21] | Protocols must be adapted for bacteria, typically using poly(A)-independent methods with random hexamers [21] |

| Toxin Expression Plasmids | Inducing persistence mechanisms in a controlled manner for functional studies [19] | Plasmids for inducible expression of toxins like MqsR to study their role in dormancy [19] |

The study of phenotypic heterogeneity and bacterial persistence has been revolutionized by single-cell technologies that move beyond population-level averages to reveal the behavior of rare but critically important cell states. As detailed in this application note, techniques ranging from microfluidics and advanced fluorescence microscopy to single-cell RNA-sequencing provide the necessary resolution to dissect the formation, maintenance, and resuscitation of persister cells. A comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms—centered on ppGpp, TA systems, and other stress response pathways—combined with these powerful analytical tools is paving the way for novel therapeutic strategies designed to eradicate persistent infections. The protocols and resources outlined herein provide a foundational framework for researchers embarking on this challenging yet vital area of microbiological research.

Single-cell analysis has revolutionized our understanding of bacterial persistence, revealing extraordinary heterogeneity in how individual bacterial cells survive antibiotic exposure. This application note details the core biological pathways governing persister formation—toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems, the (p)ppGpp alarmone, and the stringent response—within the context of modern single-cell research. We provide experimental protocols and quantitative frameworks that leverage cutting-edge single-cell techniques to dissect these pathways, enabling researchers to move beyond bulk population studies and uncover the molecular basis of phenotypic heterogeneity in bacterial populations.

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in Persister Pathways

| Parameter | Experimental System | Measured Value | Biological Impact | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTP Persister Threshold | B. subtilis with fluorescent GTP reporter | Rapid growth-dormancy switch when GTP drops below critical threshold | Single-cell persister formation | [23] [24] |

| Persister Frequency (Wild-type) | B. subtilis exposed to vancomycin | ~0.1% of population | Basal persistence level in exponentially growing cells | [23] |

| Triggered Persister Frequency | B. subtilis under starvation conditions | ~50% of population (500-fold increase) | Maximum induced persistence | [23] |

| TA System Impact on Survival | L. pneumophila ΔgndRX under genotoxic stress | Shift to viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state | Non-canonical TA function promoting survival | [25] |

| Bioenergetic Stress Persistence Enhancement | E. coli with constitutive ATP hydrolysis (pF1) + ciprofloxacin | Significant increase in persister fractions | Link between energy stress and persistence | [26] |

| Alarmone Synthetase Contribution | B. subtilis Rel/Sas mutants | Rel essential for triggered persistence; Rel+SasB for spontaneous | Specialization of alarmone production pathways | [23] |

Table 2: Single-Cell Experimental Observations of Persister Dynamics

| Observation | Experimental System | Methodology | Key Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-exposure Growth States | E. coli + ampicillin or ciprofloxacin | Microfluidics + single-cell tracking | Most persisters were growing before antibiotic treatment | [27] |

| Heterogeneous Survival Dynamics | E. coli at single-cell level | High-throughput time-lapse imaging | Multiple survival modes: L-form-like growth, responsive arrest, filamentation | [27] |

| Metabolic Heterogeneity in Macrophages | L. pneumophila in human macrophages | BATLI software backtracking | Early mitochondrial changes (Δψm, mROS) predict bacterial replication | [28] |

| Replication Inefficiency | L. pneumophila in hMDMs | Automated confocal microscopy + single-cell analysis | Only 17±8% of infected macrophages supported bacterial replication | [28] |

| Contact-Dependent Survival | L. pneumophila wild-type and ΔgndRX co-culture | Inter-strain co-culture assays | Wild-type cells confer enhanced survival to ΔgndRX in contact-dependent manner | [25] |

Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Alarmone-GTP Persistence Switch

Diagram 2: Stringent Response Network Integration

Diagram 3: Single-Cell Analysis Workflow

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Single-Cell Persistence Analysis Using Microfluidics

Application: Tracking persister cell histories and heterogeneous survival dynamics at single-cell resolution [27]

Materials:

- Bacterial strain: Wild-type E. coli or other target pathogen

- Growth medium: Appropriate rich and defined media

- Antibiotics: Ampicillin (100 µg/mL), ciprofloxacin (varies by MIC)

- Microfluidic device: CellASIC ONIX or similar perfusion system

- Imaging system: Phase-contrast and fluorescence microscope with environmental control

- Analysis software: Custom tracking algorithms or commercial packages

Procedure:

- Culture preparation: Grow bacterial culture to mid-exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 0.3-0.5) in appropriate medium.

- Device loading: Dilute culture to ~10⁶ cells/mL and load into microfluidic device according to manufacturer's protocol.

- Antibiotic treatment: Initiate perfusion with medium containing lethal antibiotic concentration (typically 5-10× MIC).

- Time-lapse imaging: Acquire images every 10-30 minutes for 24-48 hours using phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy.

- Cell tracking: Use automated tracking software to follow individual cells and lineages throughout experiment.

- Outcome classification: Categorize cells based on survival dynamics:

- Continuous growth and fission (L-form-like)

- Responsive growth arrest

- Post-exposure filamentation

- Cell death and lysis

- Backtracking analysis: Reconstruct pre-treatment history of persister cells to identify precursor states.

Applications: This protocol enables researchers to distinguish between different modes of persistence based on single-cell histories and pre-exposure growth states, revealing that most persisters derive from growing cells rather than dormant subpopulations.

Protocol 2: GTP Level Monitoring During Persister Formation

Application: Visualizing the alarmone-GTP switch in single cells using fluorescent reporters [23] [24]

Materials:

- Bacterial strain: B. subtilis expressing fluorescent GTP reporter

- Growth medium: Appropriate defined medium

- Antibiotics: Vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, kanamycin at determined MICs

- Starvation triggers: SHX (500 µM) for amino acid starvation, other nutrient limitations

- Imaging system: Spinning-disk confocal or high-throughput microscope

- Analysis software: BATLI or similar backtracking analysis tool [28]

Procedure:

- Strain validation: Confirm GTP reporter functionality and calibration using known GTP modulators.

- Experimental setup: Grow reporter strain to early exponential phase in defined medium.

- Stress application:

- Spontaneous persistence: Dilute and grow in fresh medium without additional stress

- Triggered persistence: Add SHX (500 µM) or allow growth into stationary phase

- Antibiotic-induced: Sub-MIC antibiotic exposure

- Time-lapse imaging: Monitor GTP fluorescence and cell growth at 5-15 minute intervals.

- Threshold determination: Identify critical GTP threshold value correlating with persistence commitment.

- Single-cell analysis: Track individual cells and correlate GTP dynamics with survival outcomes.

- Validation: Confirm persistence through antibiotic challenge and regrowth assays.

Applications: This protocol enables direct visualization of the critical GTP threshold that triggers persister formation, demonstrating that all three persistence pathways (spontaneous, triggered, antibiotic-induced) converge on this common alarmone-GTP switch mechanism.

Protocol 3: Host-Pathogen Single-Cell Analysis Using BATLI

Application: Predicting bacterial replication outcomes in infected macrophages through backtracking analysis [28]

Materials:

- Host cells: Human monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDMs)

- Bacterial strain: L. pneumophila expressing constitutive GFP

- Dyes: Hoechst (nuclear stain), Cell Tracker Blue (cytoplasmic stain), mitochondrial probes (TMRM for Δψm, MitoSOX for mROS)

- Equipment: High-throughput confocal microscope, 384-well microplates

- Software: BATLI (Backtracking Analysis of Time-Lapse Images)

Procedure:

- Macrophage preparation: Differentiate hMDMs in 384-well microplates for 5-7 days.

- Infection: Infect macrophages with GFP-expressing L. pneumophila at MOI 10.

- Staining: Load mitochondrial probes and live-cell tracking dyes before infection.

- Time-lapse imaging: Acquire images hourly for 18 hours post-infection.

- Single-cell segmentation: Use BATLI to identify and track individual infected macrophages.

- Parameter quantification: Measure bacterial area (GFP fluorescence), mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm), and mitochondrial ROS production (mROS) for each cell.

- Backtracking analysis: Categorize cells based on infection outcome (bacterial replication vs. restriction) and reconstruct metabolic parameter histories.

- Predictive modeling: Train machine learning models using early timepoint data to predict later replication outcomes.

Applications: This protocol enables identification of early metabolic predictors of bacterial replication success in host cells, achieving 83% accuracy in predicting L. pneumophila replication outcomes by 5 hours post-infection based on mitochondrial parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Single-Cell Persistence Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Reporters | Fluorescent GTP biosensors, constitutive GFP/RFP | Visualizing metabolic states and bacterial localization in single cells | [23] [28] |

| Metabolic Probes | TMRM (Δψm), MitoSOX (mROS), Cell Tracker dyes | Monitoring mitochondrial function and metabolic activity in host and bacterial cells | [28] |

| Stress Inducers | DL-serine hydroxamate (SHX), arsenate, CCCP | Inducing stringent response and bioenergetic stress in controlled manner | [23] [29] |

| Single-Cell Platforms | Microfluidic devices, 384-well microplates | Maintaining individual cell tracking and high-throughput experimentation | [28] [27] |

| Analysis Software | BATLI, custom tracking algorithms | Backtracking analysis and outcome prediction from time-lapse data | [28] |

| TA System Tools | Pan-TA deletion strains, inducible toxin expression | Dissecting specific TA system functions in persistence | [25] [3] |

Technical Notes and Applications

Interpretation of Single-Cell Data

Single-cell analysis consistently reveals that persistence is not merely a binary dormant state but encompasses a continuum of metabolic states and survival strategies. Researchers should expect significant heterogeneity even within genetically identical populations, with multiple distinct pathways leading to antibiotic survival. The alarmone-GTP switch represents a convergent mechanism that can be triggered through different upstream signaling events.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Low persister frequencies: Use appropriate stress conditions (starvation, sub-MIC antibiotics) to increase persister yields for single-cell analysis

- Cell tracking challenges: Optimize dye concentrations and imaging intervals to balance phototoxicity with temporal resolution

- Reporter functionality: Validate metabolic reporters under control conditions before persistence experiments

- Macrophage heterogeneity: Use primary macrophages rather than cell lines and account for donor-to-donor variability

Applications in Drug Discovery

These protocols enable identification of novel anti-persister targets, including:

- Alarmone synthetase inhibitors [30]

- Metabolic reprogramming approaches to reverse persistence [31]

- Combination therapies that target both growing and persistent subpopulations

- Host-directed therapies that modulate metabolic interactions [28]

The integration of single-cell analysis with molecular pathway dissection provides unprecedented resolution for understanding and combating bacterial persistence, offering new opportunities for therapeutic intervention against chronic and recurrent infections.

Historical Context and Evolution of Persister Research

Bacterial persisters represent a fascinating and clinically significant subpopulation of cells that survive antibiotic treatment without genetically acquired resistance. These dormant phenotypic variants are a major contributor to recurrent and chronic infections, posing a substantial challenge in clinical settings [3] [32]. This Application Note traces the evolution of persister research from its initial discovery to contemporary single-cell analytical approaches, providing researchers with both historical context and practical methodologies for investigating this complex phenomenon. The content is framed within a broader thesis on single-cell techniques, highlighting how technological advances have progressively unveiled the mechanisms underlying bacterial persistence.

Within isogenic bacterial populations, persisters constitute a small fraction (typically 0.001–1%) that transiently exhibits multidrug tolerance through metabolic dormancy or reduced growth rates rather than genetic resistance mechanisms [33] [3]. This transient, non-heritable nature has made persisters particularly challenging to study, requiring sophisticated approaches capable of capturing rare physiological states within heterogeneous populations.

Historical Timeline of Key Discoveries

Table 1: Major Milestones in Persister Research

| Year | Key Discovery | Researcher(s) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | Initial observation of bacterial survival after penicillin exposure | Gladys Hobby | First documentation of phenotypic tolerance to antibiotics [3] |

| 1944 | Naming of "persisters" and description of their characteristics | Joseph Bigger | Formal conceptualization of the persister phenotype and proposal for intermittent treatment [3] [34] |

| 1970s | Description of "antibiotic tolerance" in pneumococcal mutants | Alexandre Tomasz | Distinction between different forms of bacterial survival under antibiotic pressure [3] |

| 1983 | Identification of first high-persistence (hip) mutant in E. coli | Harris Moyed | Genetic evidence for persistence mechanisms via hipA gene discovery [3] |

| 2000 | Link between persistence and biofilm infections | Kim Lewis | Established clinical relevance to chronic infections [3] |

| 2004–Present | Single-cell technologies and molecular mechanisms | Multiple groups | Elucidation of persister formation mechanisms and heterogeneity [33] [15] [35] |

The historical journey of persister research reveals a pattern of initial discovery, prolonged neglect, and renewed interest driven by technological advances. The phenomenon was first observed in 1942 when Gladys Hobby discovered that penicillin killed approximately 99% of bacterial cells, leaving 1% survivors [3]. This finding was systematically investigated by Joseph Bigger in 1944, who coined the term "persisters" and recognized their clinical significance, even proposing an intermittent treatment strategy that foreshadowed modern therapeutic approaches [3].

Despite these astute observations, persister research remained relatively dormant for several decades, overshadowed by the excitement surrounding new antibiotic discovery and the more immediately pressing issue of genetic resistance [36]. The field experienced a renaissance beginning in the 1980s with Moyed's identification of the first high-persistence (hip) mutant in E. coli, providing crucial evidence that persistence had a genetic component and could be systematically studied [3]. The clinical relevance of persisters became unequivocally established when Kim Lewis demonstrated their connection to biofilm-associated chronic infections in 2000, explaining why these infections often relapse after antibiotic therapy [3] [32].

Evolution of Methodological Approaches

From Population-Level to Single-Cell Analysis

Early persister research relied predominantly on population-level assays such as biphasic killing curves, which revealed the presence of persisters through a characteristic pattern of rapid initial killing followed by a plateau phase representing the surviving subpopulation [3] [37]. While these approaches confirmed the existence of persistence, they offered limited insight into the underlying heterogeneity or mechanisms.

The advent of single-cell technologies has revolutionized the field by enabling researchers to investigate rare persister cells within complex populations. Key methodological transitions include:

- Microscopy and Microfluidics: Advanced imaging platforms combined with microfluidic devices allow continuous observation of individual bacterial cells before, during, and after antibiotic exposure [15]. The membrane-covered microchamber array (MCMA) device, for instance, enables researchers to monitor over one million individual cells simultaneously under controlled conditions [15].

- Flow Cytometry: This approach facilitates high-throughput analysis and sorting of persister cells based on physiological parameters such as membrane potential, metabolic activity, or reporter gene expression [33].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): Cutting-edge transcriptomic techniques like PETRI-seq have enabled comprehensive profiling of persister cell states, revealing that diverse persister types converge toward a transcriptional state characterized by translational deficiency [35].

Key Single-Cell Techniques and Applications

Table 2: Single-Cell Methodologies for Persister Research

| Technique | Key Features | Applications in Persistence Research | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microfluidics | Long-term imaging of individual cells under controlled environments; membrane-covered microchambers for medium exchange | Tracking persister cell histories; heterogeneous survival dynamics; correlation between pre-exposure growth and persistence [15] | |

| Flow Cytometry | High-throughput multiparameter analysis; cell sorting based on physiological markers | Isolation of persister subpopulations; analysis of metabolic heterogeneity; quantification of persistence frequency [33] [38] | |

| Fluorescent Biosensors | Gene expression reporters; protein-FP fusions; FRET-based physiological sensors | Monitoring transcriptional and translational heterogeneity; quantifying metabolic activity; stress response pathways [33] | |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Comprehensive transcriptome profiling of individual cells; identification of rare cell states | Defining persister-specific transcriptional signatures; identifying key regulatory pathways [35] | |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Label-free analysis of biochemical composition; monitoring metabolic activity | Identification of physiological states associated with persistence; non-invasive tracking of dormancy depth [33] |

Contemporary Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Single-Cell Persister Dynamics Using Microfluidics

This protocol adapts methodologies from [15] for investigating persister cell histories at single-cell resolution.

Materials and Equipment

- Strain: E. coli MG1655 (or relevant bacterial species)

- Microfluidic Device: Membrane-covered microchamber array (MCMA)

- Culture Media: Appropriate broth medium (e.g., LB, M9 minimal medium)

- Antibiotics: Ampicillin (200 µg/mL), ciprofloxacin (1 µg/mL) or target antibiotic

- Imaging System: Time-lapse fluorescence microscope with environmental control

- Analysis Software: Image analysis platform (e.g., ImageJ, Matlab) for single-cell tracking

Procedure

- Device Preparation: Fabricate MCMA device with 0.8-µm deep microchambers on glass coverslip; coat with cellulose semipermeable membrane via biotin-streptavidin bonding [15].

- Cell Loading: Introduce mid-exponential phase bacterial culture (OD600 ≈ 0.3-0.5) into microchambers at appropriate dilution to achieve 1-10 cells per chamber.

- Pre-treatment Monitoring: Flow fresh medium through device and record baseline growth for 2-3 hours at appropriate temperature (e.g., 37°C for E. coli) with images captured at 5-10 minute intervals.

- Antibiotic Treatment: Switch medium to antibiotic-containing solution (e.g., 200 µg/mL ampicillin, 12.5×MIC) for defined treatment period (typically 3-8 hours).

- Post-treatment Recovery: Replace with fresh antibiotic-free medium and monitor for regrowth for 12-24 hours.

- Image Analysis: Track individual cell lineages using automated tracking software; classify survival dynamics based on morphological changes and division events.

Key Parameters and Data Analysis

- Quantification of Survival Dynamics: Categorize persister behaviors as (1) continuous growth with L-form-like morphology, (2) responsive growth arrest, or (3) post-exposure filamentation [15].

- Correlation Analysis: Link pre-exposure growth characteristics (division time, cell size) to survival probability.

- Persistence Frequency Calculation: Determine as percentage of cells surviving antibiotic treatment capable of resuming growth.

Protocol: Persister Recovery Kinetics via Spectrophotometry and Flow Cytometry

This protocol, adapted from [38], enables quantification of persister resuscitation dynamics and physiological states.

Materials

- Bacterial Strains: Target organism with appropriate genetic background

- Antibiotics: Bactericidal antibiotics relevant to study

- Culture Media: Appropriate broth medium

- Flow Cytometer: Equipped with 488-nm laser and appropriate filter sets

- Viability Stains: SYTOX Green, membrane potential-sensitive dyes (e.g., DiOC2(3))

- Microplate Reader: For high-throughput spectrophotometric measurements

Procedure

Persister Isolation:

- Grow bacterial culture to desired phase (exponential, stationary)

- Treat with lethal antibiotic concentration (5-10×MIC) for predetermined time

- Wash cells to remove antibiotic using centrifugation or filtration

- Confirm persister isolation by plating and CFU enumeration

Recovery Kinetics Monitoring:

- Resuspend persister cells in fresh pre-warmed medium

- Distribute into 96-well plates for spectrophotometric reading

- Monitor OD600 at regular intervals (every 15-30 minutes) for 12-24 hours

- Include controls (untreated cells, medium only)

Single-Cell Physiological Analysis:

- Sample recovering culture at designated timepoints (0, 2, 4, 8 hours)

- Stain with viability indicators (SYTOX Green) and metabolic dyes

- Analyze by flow cytometry with appropriate gating strategies

- Correlate physiological states with resuscitating capability

Data Interpretation

- Lag Time Determination: Calculate duration from antibiotic removal to resumption of growth

- Heterogeneity Assessment: Identify distinct subpopulations based on physiological parameters

- Correlation Analysis: Link resuscitation kinetics with pre-treatment conditions or genetic background

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Single-Cell Analysis Workflow for Persister Research

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for single-cell analysis of bacterial persisters, integrating multiple technological approaches.

Molecular Mechanisms of Persister Formation

Diagram 2: Molecular pathways and cellular responses involved in persister cell formation, highlighting key regulatory mechanisms.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Persister Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Reporters | GFP, mCherry, CFP transcriptional fusions; RpoS-mCherry | Monitoring gene expression heterogeneity; stress response pathways; promoter activity in single cells [33] [15] | |

| Viability and Metabolic Probes | SYTOX Green, Hoechst 33342, DiOC2(3), ATP biosensors (QUEEN, iATPSnFR) | Distinguishing live/dead cells; DNA content analysis; membrane potential; metabolic activity monitoring [33] | |

| Biosensors | FRET-based sensors; riboswitch-based biosensors (e.g., c-di-GMP); O-propargyl-puromycin (OPP) | Quantifying intracellular metabolites; second messenger dynamics; protein synthesis rates [33] | |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPRi libraries; transposon mutant collections; fluorescent protein fusion libraries | Genome-wide functional screens; targeted gene knockdown; protein localization studies [35] | |

| Specialized Growth Media | Defined minimal media; nutrient-limited conditions; stress-inducing supplements | Controlling growth rates; inducing persistence; mimicking host environments [15] [35] |

The historical evolution of persister research demonstrates a remarkable trajectory from phenomenological observation to mechanistic understanding at single-cell resolution. Early population-level studies correctly identified the existence and clinical significance of persisters but lacked the tools to probe their underlying heterogeneity. Contemporary single-cell technologies have revealed that persistence is not a unitary phenomenon but encompasses diverse survival strategies influenced by antibiotic class, growth history, and stochastic cellular processes [15] [35].

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: First, the integration of multi-omics approaches at single-cell resolution will further elucidate the molecular networks controlling persister formation and resuscitation. Second, the development of more sophisticated microfluidic platforms that better mimic host environments will enhance the clinical relevance of experimental findings. Finally, the translation of basic mechanistic insights into therapeutic strategies that specifically target persister cells holds promise for addressing the persistent challenge of chronic and recurrent infections.

The methodologies and protocols outlined in this Application Note provide researchers with practical tools for investigating bacterial persistence using state-of-the-art single-cell approaches, contributing to the ongoing effort to understand and ultimately overcome this significant clinical problem.

The Single-Cell Toolbox: Techniques for Isolating, Observing, and Profiling Persisters

The relentless challenge of antibiotic persistence, a phenomenon where a small, dormant sub-population of bacteria survives antibiotic treatment, represents a significant hurdle in treating recurrent infections. Unlike genetic resistance, persistence is a transient, phenotypic state, making it difficult to detect and eradicate [39] [33]. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of bacterial persistence requires tools that can dissect cellular processes at the single-cell level, as these rare persister cells are often masked in population-averaged studies. Fluorescent biosensors and reporters have emerged as indispensable instruments in this endeavor, providing real-time, dynamic insights into the gene expression, metabolic activity, and signaling events that define the persister state. This Application Notes and Protocols document details the use of these powerful tools, framing them within the context of a broader thesis on single-cell techniques for analyzing bacterial persisters. It is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the methodologies to illuminate the hidden heterogeneity within bacterial populations and accelerate the development of anti-persister therapies.

Technical Specifications of Key Biosensors and Reporters

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of several advanced biosensors and reporters pivotal for single-cell persister research.

Table 1: Key Fluorescent Biosensors and Reporters for Single-Cell Analysis

| Biosensor/Reporter Name | Detection Target | Technology/Design | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Application in Persister Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QUEEN-2m [40] | ATP concentration | Single fluorescent protein (cpEGFP) fused to bacterial ATP-binding protein; ratiometric. | ( K_d ) ~2 mM (at 25°C); Dynamic range ~3.0; Insensitive to growth rate changes. | Quantifying absolute ATP levels to assess metabolic dormancy and heterogeneity in persister cells. |

| FRET-based Pyruvate Sensor [41] | Pyruvate concentration | FRET pair (CFP/YFP) flanking pyruvate-binding domain of PdhR. | ( EC_{50} ) ~400 µM (in permeabilized cells); Responds within seconds to metabolic shifts. | Monitoring rapid fluctuations in central metabolism and glycolytic oscillations upon perturbation. |

| RGB-S Reporter [42] | Multimodal stress response (RpoS, SOS, RpoH) | Three orthogonal fluorescent proteins (RFP, GFP, BFP) under control of distinct stress promoters. | Reports on physiological stress (RFP), genotoxicity (GFP), and cytotoxicity (BFP) simultaneously. | Identifying heterogeneous stress responses in biofilms and characterizing multimodal effects of anti-persister compounds. |

| Riboswitch-based TPP Biosensor [43] | Thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP) metabolism | thiC riboswitch aptamer domain controlling GFP expression. | Detects TPP concentrations as low as 50-100 nM; ~2-fold dynamic range in regulation. | Interrogating metabolic pathway activity and nutrient status at a single-cell level. |

Application Notes & Detailed Protocols

Protocol 1: Single-Cell ATP Quantification in Bacterial Persisters using QUEEN-2m

Background: Persister cells are characterized by a marked reduction in metabolic activity. Direct measurement of intracellular ATP concentration is a critical metric for assessing this metabolic dormancy. The QUEEN-2m biosensor is ideal for this purpose due to its ratiometric nature, insensitivity to bacterial growth rate, and affinity suitable for physiological ATP ranges [40].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: E. coli expressing QUEEN-2m biosensor from an appropriate plasmid vector.

- Growth Medium: Suitable defined medium (e.g., M9 minimal medium) with a carbon source.

- Antibiotic: For selection of the biosensor plasmid.

- Inducer: If the biosensor is under inducible control.

- Imaging Equipment: Epifluorescence or confocal microscope equipped with:

- Excitation filters: 400/10 nm and 480/20 nm.

- Emission filter: 510/20 nm.

- 40x or higher magnification oil-immersion objective.

- Microfluidic Flow Cell or Live-Cell Imaging Chamber: For environmental control during time-lapse imaging.

- Image Analysis Software: e.g., ImageJ/FIJI with ratiometric analysis plugins.

Procedure:

- Culture Preparation: Grow the sensor strain to the desired growth phase (e.g., mid-exponential or stationary phase, where persister levels are higher [39]) in the appropriate medium with antibiotic selection.

- Sample Loading: For continuous observation, immobilize cells in a microfluidic flow chamber pre-warmed to 37°C. Alternatively, prepare an agarose pad for fixed-endpoint imaging.

- Antibiotic Challenge (Optional): To isolate and study persisters, perfuse the chamber with medium containing a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., ampicillin or ciprofloxacin) for a defined period. Wash with fresh medium to remove the antibiotic before imaging survivors.

- Ratiometric Image Acquisition:

- Acquire two images for each field of view and time point: one with 400 nm excitation and one with 480 nm excitation, both using the 510 nm emission filter.

- Set acquisition parameters (exposure time, gain) to avoid pixel saturation and keep them constant throughout the experiment.

- Collect time-lapse data at regular intervals (e.g., every 5-10 minutes) to monitor dynamic changes.

- Image and Data Analysis:

- Background Subtraction: Subtract the background fluorescence from both the 400ex and 480ex image stacks.

- Ratio Calculation: Create a ratio image (R = Intensity({400ex}) / Intensity({480ex})) for each time point.

- Single-Cell Quantification: Define regions of interest (ROIs) around individual cells and extract the mean ratio value (R) for each cell over time.

- ATP Calibration: To convert ratio values to absolute ATP concentrations, perform an in vivo calibration using cells with known ATP levels (e.g., by titrating with metabolic inhibitors like KCN as described in [40]).

Troubleshooting:

- Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Ensure the biosensor is expressed at sufficient levels. Use a stronger promoter or increase inducer concentration.

- Cell Photobleaching: Minimize light exposure by using lower excitation intensity or longer intervals between time points.

- Inconsistent Ratios: Verify that the microscope light source and filters are stable. Use control cells expressing a non-ratiometric fluorescent protein to check for illumination artifacts.

Protocol 2: Profiling Multimodal Stress Responses in Biofilms using the RGB-S Reporter

Background: Biofilms are a major reservoir for persisters, and cells within a biofilm experience heterogeneous microenvironments, leading to varied stress responses. The RGB-S reporter allows simultaneous monitoring of three major stress regulons (RpoS, SOS, RpoH) in live cells, providing a high-content readout of a cell's physiological state [42].

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: E. coli harboring the RGB-S reporter plasmid (PosmY::mRFP1, PsulA::GFPmut3b, PgrpE::mTagBFP2) [42].

- Growth Medium: LB or defined medium.

- Antibiotic: Kanamycin for plasmid selection.

- Stressors: Compounds of interest (e.g., glyphosate for RpoS, nalidixic acid for SOS, 2-propanol for RpoH).

- Imaging Equipment: Confocal microscope capable of sequential imaging with laser lines and filters for RFP (ex: 561 nm, em: 570-620 nm), GFP (ex: 488 nm, em: 500-550 nm), and BFP (ex: 405 nm, em: 430-470 nm).

- Flow Cytometer (Optional): For high-throughput single-cell analysis.

Procedure:

- Biofilm Cultivation: Grow the RGB-S reporter strain in a flow cell or on a coverslip in a drip-flow reactor to form a mature biofilm (e.g., 3-5 days).

- Stressor Exposure: Expose the biofilm to the stressor of interest by perfusing with medium containing the compound at the desired concentration.

- Time-Lapse Confocal Imaging:

- Image the biofilm at multiple locations and time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4 hours post-exposure).

- Use sequential scanning mode to avoid cross-talk between the three fluorescent channels.

- Acquire Z-stacks to capture the three-dimensional structure of the biofilm.

- Image Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Apply a mild background subtraction to each channel.

- Segmentation: Use automated or semi-automated cell segmentation tools (e.g., in Ilastik or CellProfiler) to identify individual bacterial cells within the biofilm.

- Intensity Extraction: For each segmented cell, measure the mean fluorescence intensity in the RFP, GFP, and BFP channels.

- Data Visualization and Interpretation:

- Create scatter plots (e.g., RFP vs. GFP) to visualize subpopulations with different stress response signatures.

- Overlay fluorescence data on the biofilm structure to correlate stress response with spatial location (e.g., interior vs. periphery).

Troubleshooting:

- Spectral Cross-Talk: Optimize sequential scanning settings and verify that signal in one channel is not detected in another using control samples with single fluorophores.

- Weak BFP Signal: BFP maturation can be sensitive. Ensure the microscope detectors are optimized for the blue spectrum, and consider using a more photostable BFP variant if needed.

- Plasmid Loss: Maintain antibiotic selection throughout the experiment to ensure plasmid retention, especially in long-term biofilm cultures [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Fluorescent Biosensor Experiments

| Item/Category | Function/Description | Example Product/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors | Core reagents for detecting specific metabolites or signaling events in live cells. | QUEEN series (ATP) [40]; FRET-based pyruvate sensor [41]; RGB-S reporter plasmid [42]. |

| Microfluidic Cultivation Devices | Provides precise control over the cellular microenvironment, enabling long-term imaging and antibiotic perturbation. | Commercial flow cells (e.g., CellASIC ONIX2); lab-made PDMS devices. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Media & Supplements | Maintains cell viability and function during microscopy, without inducing autofluorescence. | Phenol-red free imaging media; buffering agents (e.g., HEPES). |

| High-Sensitivity Cameras | Essential for detecting low-light fluorescence signals from single cells, especially dim or small bacterial cells. | Electron-Multiplying CCD (EMCCD) or scientific CMOS (sCMOS) cameras. |

| Metafluor/ImageJ FIJI Software | Industry-standard and open-source software for ratiometric image analysis, cell segmentation, and fluorescence quantification. | Molecular Devices MetaFluor; NIH ImageJ/FIJI. |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Single-Cell Analysis Workflow for Bacterial Persisters

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for using fluorescent biosensors to investigate bacterial persisters, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Key Signaling Pathways in Bacterial Persistence

Bacterial persistence is regulated by an interconnected network of signaling pathways that respond to metabolic and environmental stress. The following diagram summarizes the core pathways involving toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems, alarmones, and second messengers, as revealed by biosensor studies [39] [33] [42].

Bacterial persisters are a transient, phenotypically variant subpopulation within an isogenic culture that exhibit remarkable tolerance to high doses of conventional antibiotics without acquiring heritable genetic resistance [3] [37]. These metabolically dormant or slow-growing cells are now recognized as a primary cause of chronic and recurrent infections, posing a significant challenge in clinical settings [44] [3]. Unlike resistant bacteria, persisters do not exhibit an elevated Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and resume normal growth once antibiotic pressure is removed, leading to disease relapse [37].

The study of persister cells has been historically challenging due to their low frequency (typically 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻³) in bacterial populations and their non-genetic, transient nature [15] [45]. Traditional bulk-culture methods lack the resolution to isolate or observe these rare cells, limiting our understanding of their formation and survival mechanisms [46]. The emergence of microfluidic technologies coupled with high-resolution live-cell imaging has revolutionized this field by enabling real-time tracking of individual bacterial cells before, during, and after antibiotic exposure [15] [47] [46]. This application note details standardized protocols for using microfluidic devices to dissect the heterogeneous dynamics of bacterial persisters at single-cell resolution, providing researchers with robust methodologies to advance both fundamental knowledge and therapeutic development.

Background and Significance

The Persister Phenotype: Definitions and Clinical Relevance

Persister cells were first identified by Joseph Bigger in 1944 when he observed that penicillin failed to sterilize a Staphylococcus culture [3] [37]. These cells exhibit biphasic killing kinetics in time-kill assays, characterized by an initial rapid decline in viable cells followed by a much slower death rate of the persistent subpopulation [37]. This phenomenon is distinct from antibiotic resistance, as persisters survive antibiotic treatment through passive mechanisms primarily linked to reduced metabolic activity and growth arrest, rather than active defense mechanisms [3].

Clinically, persisters are implicated in a wide range of persistent infections including tuberculosis, recurrent urinary tract infections, Lyme disease, and biofilm-associated infections on medical implants [3]. Their presence necessitates prolonged antibiotic therapies, which in turn contributes to the development of genetic resistance [37]. Eradicating persisters remains a formidable challenge in infectious disease management, as most conventional antibiotics target actively growing cells.

The Power of Single-Cell Analysis

Population-level studies mask the significant heterogeneity in individual cell responses to antibiotic stress [46]. Microfluidic platforms overcome this limitation by enabling:

- Long-term tracking of single-cell lineages across multiple generations

- Precise control of microenvironmental conditions and antibiotic gradients

- High-throughput observation of rare persister cells among millions of susceptible cells

- Real-time monitoring of morphological and physiological changes during stress adaptation

Recent studies utilizing microfluidics have challenged the classical dogma that persisters are exclusively dormant cells generated before antibiotic exposure. Observations of over one million individual Escherichia coli cells revealed that many persisters were actively growing before treatment with ampicillin or ciprofloxacin, and exhibited diverse survival strategies including continuous growth with L-form-like morphologies, responsive growth arrest, or post-exposure filamentation [15] [45].

Experimental Protocols

Microfluidic Device Fabrication: The MCMA Platform

The Membrane-Covered Microchamber Array (MCMA) device has been successfully implemented for persister studies in E. coli and can be adapted for other bacterial species [15] [45].

Materials and Equipment

- Photomasks: High-resolution CAD files printed on polymer slides

- Silicon wafers: 4-inch diameter

- Photoresist: SU-8 2002 and SU-8 2025

- PDMS: Polydimethylsiloxane base and curing agent

- Semipermeable membrane: Cellulose membrane functionalized with biotin

- Glass coverslips: No. 1.5 thickness for high-resolution imaging

- Spin coater

- UV exposure system

- Plasma cleaner

- Soft bake and hard bake ovens

Fabrication Procedure

Wafer Preparation: Clean a 4-inch silicon wafer with 100% isopropanol and bake at 120°C for 15 minutes to dehydrate [48].

Photolithography for Microchambers:

- Apply SU-8 2002 photoresist (3 mL) to the wafer using a spin coater at 400 rpm for 30 seconds to achieve a 3-μm layer [48].

- Soft bake at 95°C for 2 minutes [48].

- Expose through the microchamber photomask with 100 mJ/cm² UV at 365 nm [48].

- Perform post-exposure bake at 95°C for 2 minutes [48].

- Develop in SU-8 developer for 15-30 seconds, rinse with isopropanol, and dry with compressed air [48].

- Hard bake at 150°C for 15 minutes [48].

Photolithography for Flow Channels:

- Apply SU-8 2025 photoresist (3 mL) at 2,500 rpm for 30 seconds to achieve a 40-μm layer [48].