Substrate Control as an Anti-Persister Strategy: Disrupting Metabolic Dormancy to Combat Chronic Infections

This article explores the critical role of substrate availability in the formation and survival of bacterial persister cells, a major cause of chronic and relapsing infections.

Substrate Control as an Anti-Persister Strategy: Disrupting Metabolic Dormancy to Combat Chronic Infections

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of substrate availability in the formation and survival of bacterial persister cells, a major cause of chronic and relapsing infections. We synthesize foundational research and recent advances demonstrating that nutrient limitation is a key environmental trigger driving phenotypic switching to the dormant, antibiotic-tolerant persister state. The content details methodological approaches for quantifying substrate-dependent persister dynamics, including computational modeling and stable isotope tracing. It further examines practical strategies for optimizing substrate environments to prevent persister formation and enhance the efficacy of conventional antibiotics. By integrating foundational knowledge with application-focused and comparative analyses, this resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for developing novel therapeutic interventions that target the metabolic vulnerabilities of persistent pathogens.

The Metabolic Basis of Bacterial Persistence: How Nutrient Cues Drive Dormancy

Fundamental Concepts: Persistence, Tolerance, and Resistance

What is the fundamental difference between a persister cell and a genetically resistant bacterium?

The core distinction lies in the heritability and mechanism of survival. Persister cells are a sub-population of genetically normal, drug-susceptible bacteria that survive antibiotic treatment by entering a transient, dormant state. Their offspring are fully susceptible once the antibiotic is removed. In contrast, genetically resistant bacteria possess inherited genetic mutations that allow them to grow in the presence of the antibiotic, and their offspring inherit this resistance [1] [2] [3].

The table below summarizes the key differentiating characteristics.

Table 1: Key Characteristics Differentiating Antibiotic Resistance, Tolerance, and Persistence

| Characteristic | Genetic Resistance | Tolerance (General) | Persistence (A Subset of Tolerance) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Inherited ability to grow in the presence of an antibiotic. | Ability to survive a transient exposure to a bactericidal antibiotic without growing. | A phenotypic variant within an isogenic population that survives antibiotic treatment by entering a dormant state. |

| Underlying Mechanism | Genetic mutations (e.g., drug target modification, efflux pumps, enzyme inactivation). | Slower overall death rate of the entire population, often linked to slow growth. | Non-growing or slow-growing dormancy of a small subpopulation. |

| Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | Increased | Unchanged | Unchanged |

| Killing Kinetics | Can grow at antibiotic concentrations above the MIC of susceptible cells. | The entire population dies slower than a susceptible population. | Biphasic killing curve: rapid killing of most cells, followed by a subpopulation (persisters) that dies very slowly. |

| Heritability | Stable and heritable across generations. | Can be a heritable trait of the entire strain or a non-heritable, transient phenotype. | Transient and non-heritable; the progeny of persisters are as susceptible as the original population. |

| Percentage in Population | Can be 100% of the population. | 100% of the population exhibits the trait. | Typically a very small fraction (e.g., 0.001% - 1%) [4] [3]. |

What is the relationship between antibiotic tolerance and persister cells?

The terms are often used interchangeably but have a specific relationship. Tolerance describes the general phenomenon of surviving an antibiotic treatment without growing. Persistence is a specific form of tolerance that refers to the small, dormant subpopulation responsible for the biphasic killing pattern observed in an otherwise susceptible culture [3]. All persisters are tolerant, but not all tolerance is due to persistence (e.g., an entire population could be tolerant due to slow growth in stationary phase).

Core Molecular Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

What are the primary molecular mechanisms driving persister cell formation?

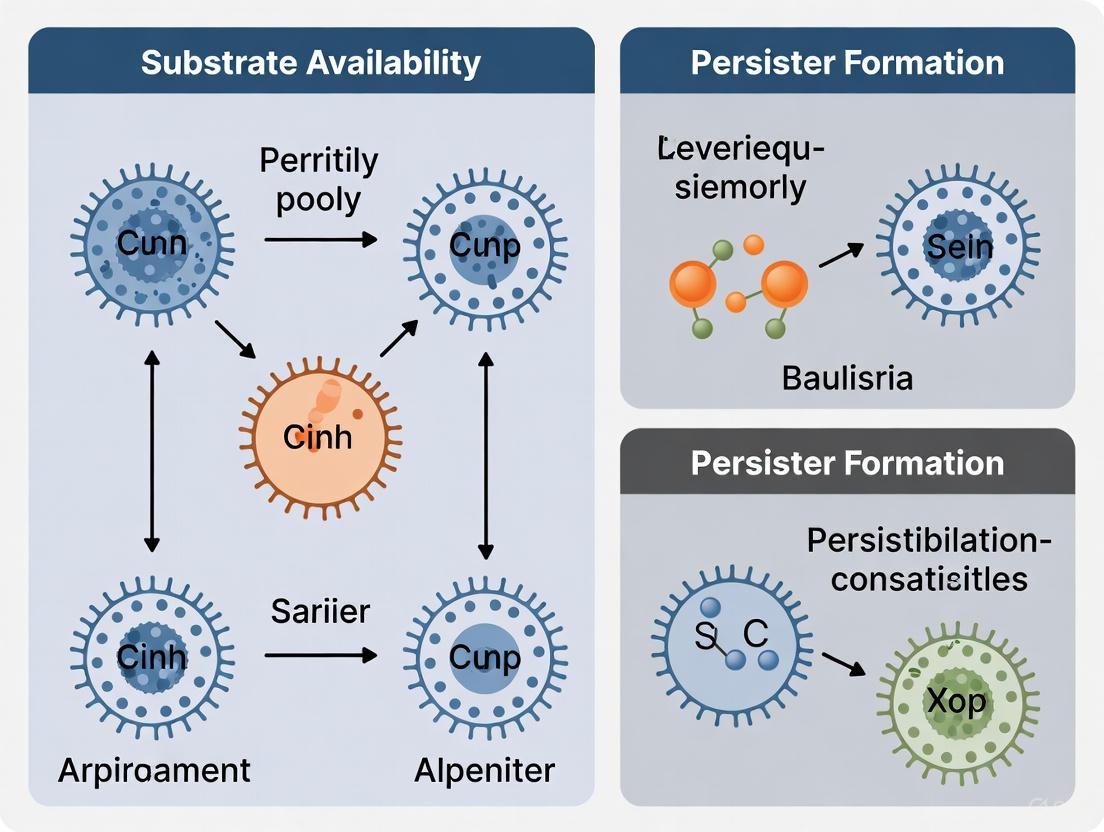

Persister formation is not governed by a single mechanism but by a network of interconnected biological processes that lead to cellular dormancy. The major pathways are illustrated below and detailed thereafter.

Diagram 1: Key pathways to persister formation.

A. Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Modules

TA systems are genetic loci encoding a stable "toxin" and an unstable "antitoxin." Under stress, the antitoxin is degraded, allowing the toxin to act on targets such as translation or membrane potential, inducing growth arrest [2] [3]. For example, in E. coli, the HipA toxin phosphorylates a tRNA synthetase, leading to a halt in protein synthesis and promoting persistence [1] [3].

B. The Stringent Response and (p)ppGpp

Nutrient starvation triggers the stringent response, mediated by the alarmone (p)ppGpp. This signaling molecule acts as a global regulator that dramatically reprograms cellular metabolism, shutting down energy-intensive processes like ribosome synthesis and promoting a dormancy-like state [2].

C. Biofilms

Biofilms are structured communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix. The biofilm environment creates gradients of nutrients and oxygen, leading to heterogeneous metabolic states. Bacteria in the inner, nutrient-poor regions of a biofilm often enter a dormant state, making biofilms a major reservoir for persister cells [5] [2]. It is estimated that over 65% of all infections are associated with biofilms [5].

D. The SOS Response

Antibiotics that cause DNA damage (e.g., fluoroquinolones) can induce the SOS response, a coordinated DNA repair system. This response can also lead to cell cycle arrest and promote the formation of persister cells [5] [2].

What is a standard experimental workflow for isolating and studying persister cells?

The most common method for quantifying persisters is the biphasic killing assay, which leverages their defining characteristic of antibiotic tolerance followed by regrowth upon drug removal. The workflow is as follows [6] [3].

Diagram 2: Workflow for a persister killing assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Models

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Model Systems for Persister Studies

| Reagent / Model | Function / Rationale | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Persister (Hip) Mutants | Genetically engineered or selected strains that produce a higher frequency of persisters, facilitating their study. | E. coli hipA7 mutants are widely used to study Type II (stochastic) persistence and to screen for anti-persister compounds [1] [7]. |

| Biphasic Killing Assay | The gold-standard method for detecting and quantifying persister cells based on their unique killing kinetics [6]. | Used to demonstrate the tolerance of a bacterial subpopulation to high doses of ciprofloxacin or ampicillin. |

| Stationary Phase Cultures | An enrichment method for Type I (triggered) persisters, which are more abundant in the stationary phase [4]. | Isolating persisters from an overnight culture without the need for genetic mutants. |

| In Vitro Biofilm Models | Systems (e.g., flow cells, microtiter plates) to study persisters in a clinically relevant, biofilm-associated context. | Testing the efficacy of antimicrobial agents against P. aeruginosa biofilms grown on a catheter-like substrate [5]. |

| Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) | A clinically relevant model for studying chronic and recurrent infections linked to persisters. | Evaluating drug penetration and killing of persisters within bladder cells or biofilms [7]. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ 1: During the killing assay, my entire population dies and I see no persister "tail." What could be wrong?

- Problem: Incorrect antibiotic choice or concentration.

- Solution: Ensure you are using a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, β-lactams) at a concentration significantly above the MIC (e.g., 10x to 100x MIC). Bacteriostatic antibiotics will not produce a biphasic killing curve. Verify the MIC for your specific strain and growth conditions [6].

- Problem: Cell density is too low.

- Solution: The persister fraction is very small. Start with a sufficiently dense culture (e.g., >10^8 CFU/mL) to ensure a detectable number of persisters remain after antibiotic treatment.

- Problem: Antibiotic degradation or instability.

- Solution: Prepare fresh antibiotic solutions and confirm stability under your experimental conditions (e.g., temperature, pH).

- Problem: Stochastic nature of persistence.

- Solution: This is a known challenge. Type II persisters form spontaneously, leading to inherent variability. Increase the number of biological replicates (e.g., n ≥ 5) to achieve statistical power. Use tightly controlled and consistent growth conditions (media, temperature, shaking speed, growth phase) for all experiments [4].

- Problem: Inconsistent preparation of "stationary phase" cultures.

- Solution: Precisely define the stationary phase by growth time and optical density (OD). Using cultures that are too old may enter the death phase and skew results.

FAQ 3: How can I distinguish between a true persister and a resistant mutant?

- Problem: Uncertainty in interpreting surviving colonies.

- Solution: Perform a re-challenge experiment. Isolate colonies that survive the initial antibiotic treatment. Re-grow them in fresh, drug-free medium, and then subject the new culture to the same antibiotic. A population derived from true persisters will show the same biphasic killing pattern as the original culture. A population derived from a resistant mutant will grow in the presence of the antibiotic or show a monophasic killing curve with a much higher MIC [3].

Connecting to Your Thesis: Optimizing Substrate Availability to Prevent Persister Formation

The research context of optimizing substrate availability is directly targeted at a core mechanism of persistence. The following diagram and table outline the logical framework and potential experimental approaches for this research.

Diagram 3: Substrate availability impacts persistence.

Table 3: Experimental Approaches to Link Substrate Availability and Persistence

| Research Question | Experimental Strategy | Expected Outcome & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Does specific nutrient limitation (e.g., carbon, nitrogen) increase persister levels? | Grow cultures in defined media with and without specific nutrient limitations. Perform biphasic killing assays. | Expected: Limitation of a key nutrient increases the persister fraction. Interpretation: Specific substrate starvation induces a protective dormancy response. |

| Can supplementing a specific metabolite "awaken" persisters and re-sensitize them to antibiotics? | Isolate persisters via antibiotic treatment, then re-suspend them in fresh media containing the metabolite of interest plus a second antibiotic. | Expected: Metabolite supplementation (e.g., sugars, amino acids) enhances killing by the second antibiotic. Interpretation: The metabolite reactivates metabolism, corrupting antibiotic targets. This is the basis for "anti-persister" strategies [8]. |

| Does optimized substrate availability prevent the induction of high-persister (Hip) mutants? | Passage wild-type strains in nutrient-rich vs. nutrient-limited media under intermittent antibiotic pressure. Monitor the emergence of Hip mutants. | Expected: Hip mutants are selected for more readily in nutrient-limited environments. Interpretation: Substrate optimization reduces the selective advantage of the persister phenotype. |

Substrate Limitation as a Primary Trigger for Persister Formation

FAQs: Understanding the Core Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental link between substrate limitation and persister cell formation? Substrate limitation, particularly the depletion of a primary carbon source, acts as an environmental stress signal that triggers a subset of bacterial cells to enter a dormant, persistent state. This state is characterized by drastically reduced metabolic activity and growth arrest, which allows these cells to survive exposure to bactericidal antibiotics that typically target active cellular processes. The transition is mediated by sophisticated stress response pathways within the cell [9] [10].

Q2: How does substrate limitation-induced persistence differ from antibiotic resistance? Unlike genetic antibiotic resistance, persistence is a reversible, phenotypic tolerance. Persister cells do not possess genetic mutations that make antibiotics ineffective. Instead, their dormant state makes them less vulnerable because antibiotics often corrupt active cellular functions like cell wall synthesis or protein translation. Once the stressful condition (e.g., substrate limitation) passes and growth resumes, the new population remains genetically susceptible to the same antibiotics [1] [11].

Q3: What are the key molecular mechanisms connecting nutrient stress to the persister state? The primary pathway involves:

- The Stringent Response: Upon substrate exhaustion, uncharged tRNAs accumulate, activating the RelA enzyme to produce the alarmone (p)ppGpp [11] [12] [9].

- Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) Systems: High levels of (p)ppGpp can stimulate Lon protease to degrade labile antitoxins, freeing toxins (often mRNA-degrading enzymes) that further inhibit growth and promote dormancy. Key systems include HipBA, MqsR/MqsA, and TisB/IstR-1 [11] [9].

- Ribosome Hibernation: (p)ppGpp also promotes the production of factors like RMF and HPF, which inactivate ribosomes, halting protein synthesis and cementing the dormant state [9].

Q4: In a biofilm, where are substrate-limited persisters most likely to form? In biofilms, substrate gradients are naturally established. Substrate concentration decreases from the biofilm-bulk fluid interface toward the substratum. Consequently, substrate-limited persisters are predominantly located in the inner depths of the biofilm, where nutrient access is most restricted, rather than at the well-nourished surface [13] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Persister Yields in Batch Cultures

Problem: Difficulty obtaining reproducible subpopulations of persister cells between experiments. Solution:

- Precisely Control Growth Phase: The proportion of persisters increases as a culture transitions from exponential to stationary phase. Use the culture's optical density (OD) and substrate concentration monitoring to standardize the harvesting point [11].

- Define Substrate Limitation: Instead of using vague "stationary phase" cultures, directly measure and define the trigger point. For example, in a glucose-limited experiment, confirm glucose exhaustion with a glucose assay kit. This provides a consistent and measurable trigger for persister formation [12].

- Standardize Inoculum Age: The age of the inoculum can significantly affect persister levels. Always use an inoculum of the same physiological age and growth history to improve reproducibility [11].

Challenge 2: Differentiating Between Slow Growth and True Dormancy

Problem: Determining if cells are genuine, non-growing persisters or merely slow-growers. Solution:

- Employ Fluorescent Reporter Systems: Use a stable fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) under the control of a ribosomal promoter. Genuine persisters will exhibit dim or absent fluorescence due to halted ribosome activity and protein synthesis. These cells can be isolated and quantified using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [11] [9].

- Conduct Kill Curve Assays: Treat the population with a high concentration of a bactericidal antibiotic. A biphasic killing curve—a rapid initial drop (death of susceptible cells) followed by a stable, flat plateau (indicating non-killing of persisters)—is a hallmark of a persister subpopulation [14].

Challenge 3: Accounting for Environmental Factors in Biofilm Persistence

Problem: Biofilm persister dynamics are complex and influenced by multiple, fluctuating factors. Solution:

- Utilize Computational Modeling: Implement Individual-Based Models (IBMs) to simulate biofilm growth and persister formation. These models can account for spatial heterogeneity in substrate concentration and help distinguish between different persister formation strategies (e.g., stochastic vs. substrate-dependent) [14] [13].

- Measure Local Microenvironments: If technically feasible, use microsensors to directly measure substrate (e.g., oxygen, glucose) gradients within the biofilm. This provides empirical data to correlate with observed persister locations [10].

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from computational and experimental studies on substrate limitation and persistence.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Substrate Limitation and Persister Dynamics

| Parameter | Experimental System | Key Finding | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biofilm Killing Time | Mathematical model of a 300μm biofilm | Time for 6-log reduction increased from 13 hours (8 mg/L substrate) to 66 hours (1 mg/L substrate). | [10] |

| Persister Location | Computational model (IBM) | Substrate-dependent persisters form primarily in the inner, nutrient-deprived regions of the biofilm. | [13] |

| Metabolic State | E. coli with ribosomal GFP promoter | Persister cells showed dim fluorescence, confirming downregulation of ribosomal activity and translation. | [9] |

| Switching Strategy Impact | Computational model comparing strategies | Substrate-dependent switching allowed high persister formation rates (a_max) without penalizing overall biofilm growth. | [13] [15] |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Inducing Persisters via Carbon Source Transition

This protocol is based on the discovery that carbon source transitions are a potent trigger for fluoroquinolone persister formation in E. coli [12].

- Grow cultures to mid-exponential phase in a rich medium containing a readily usable carbon source (e.g., 0.2% glucose).

- Trigger substrate limitation by harvesting cells via centrifugation and resuspending them in a minimal medium with a poor carbon source or by allowing them to naturally exhaust the primary carbon source. Monitor growth and carbon concentration to confirm the transition point.

- Incubate the substrate-limited culture for a defined period (e.g., 1-2 hours) to allow the persistence state to establish.

- Treat with antibiotic (e.g., a fluoroquinolone like ofloxacin) at a high concentration (e.g., 10x MIC) for a set duration.

- Quantify persisters by washing the antibiotic-treated culture to remove the drug, serially diluting it, and plating on fresh rich medium to count the Colony Forming Units (CFUs) of surviving cells that can regrow.

Protocol 2: Computational Modeling of Substrate-Dependent Persistence

This methodology uses agent-based modeling to study persister dynamics in biofilms [14] [13].

- Define the virtual environment: Create a 2D grid representing a surface, with a bulk liquid above it from which a growth-limiting substrate diffuses.

- Initialize bacterial agents: Place a small number of susceptible bacterial cells randomly on the surface.

- Set growth rules: Model bacterial growth using Monod kinetics, where the local growth rate of a cell is determined by the local substrate concentration.

- Implement phenotypic switching rules:

- Substrate-dependent switching: A susceptible cell switches to a persister state with a probability that increases as the local substrate concentration decreases. A persister cell switches back to susceptible when local substrate is abundant.

- Introduce antibiotic: Simulate the diffusion of an antibiotic into the biofilm and define differential killing rates for susceptible (high death rate) and persister (low or zero death rate) cells.

- Run simulations and analyze: Output data on biofilm size, persister number and location over time, and population recovery after antibiotic removal.

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Molecular Signaling Pathway from Substrate Limitation to Persistence

Experimental Workflow for Substrate-Limitation Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Studying Substrate-Limited Persistence

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Bioreactors | Systems for precise control and monitoring of growth parameters (pH, dissolved O₂, substrate feed). | Maintaining defined, steady-state substrate concentrations to study persistence triggers. |

| Microsensors (e.g., O₂, Glucose) | Needle-type sensors for measuring microscale gradients within biofilms. | Mapping substrate concentration profiles in a biofilm to correlate with persister locations. |

| Fluorescent Protein Reporters (e.g., GFP) | Genes encoding fluorescent proteins under control of specific promoters. | Constructing reporter strains where fluorescence intensity indicates ribosomal activity or growth rate (e.g., ribosomal promoter). |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Instrument that sorts cells based on fluorescence and other light-scattering properties. | Isolating subpopulations of dim/non-fluorescent cells (potential persisters) from a larger population for downstream analysis. |

| LON Protease Inhibitors | Chemical compounds that specifically inhibit the activity of LON protease. | Experimentally blocking the TA system activation pathway to confirm its role in substrate-limited persistence. |

| Computational Modeling Software (e.g., NetLogo) | Platforms for creating agent-based models to simulate complex biological systems. | Building in silico models of biofilms to test hypotheses about substrate-dependent persister formation and treatment strategies. |

Carbon Source Utilization and Metabolic Shutdown in Dormant Cells

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental metabolic characteristic of dormant cells, such as bacterial persisters or dormant cancer cells? Dormant cells are characterized by a profound metabolic slowdown and a transition into a non-replicating, quiescent state. They enter a low-energy, non-growing state that makes them tolerant to conventional antibiotics and therapies, which typically target actively metabolizing and dividing cells. This state is a survival strategy under stress. The metabolic shutdown involves a general reduction in anabolic processes, including protein synthesis and ATP consumption [16] [17].

Q2: How does carbon source availability influence the formation and awakening of dormant persister cells? Carbon source availability is a critical environmental cue. Nutrient limitation, including starvation for carbon, is a key trigger that induces cells to enter the dormant persister state [17]. Conversely, the presence of readily available carbon sources can stimulate awakening. The addition of sugars and glycolysis intermediates like mannitol, glucose, fructose, and pyruvate has been shown to rapidly resuscitate persister cells, making them susceptible again to traditional antibiotics [16].

Q3: Are there specific metabolic pathways that are upregulated in dormant cells? While overall metabolism is low, certain pathways are adaptively maintained or upregulated. In some dormant cancer cells, studies suggest a dependency on fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to generate energy in a low-proliferation state [18]. This represents a shift away from the aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) often seen in proliferating cancer cells. In bacteria, stress response pathways linked to the production of alarmones like (p)ppGpp are involved in initiating persistence [19] [17].

Q4: What are the key signaling pathways that regulate the metabolic shift into dormancy? The balance between specific signaling pathways dictates the dormant state. A well-established regulator is the p38/ERK signaling balance. High activity of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in conjunction with low activity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) promotes cell cycle arrest and the maintenance of dormancy in cancer cells [20] [21]. In bacteria, the DosR regulon and SigH factor are involved in coordinating the transcriptional response to stress and inducing a dormant state in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [19].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Metabolic and Dormancy Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low persister cell yield in a population. | Insufficient or inappropriate stressor (e.g., antibiotic concentration too high, killing all cells; stress duration too short). | Optimize the inducer: Titrate the concentration and duration of the antibiotic or other stressor (e.g., nutrient starvation) to achieve a sub-population of survivors [16]. |

| Inconsistent awakening of dormant cells upon carbon source addition. | Carbon source is not readily utilizable; cells are in a deeply dormant state. | Use a mix of glycolytic intermediates (e.g., pyruvate, glucose) to provide multiple entry points into metabolism. Confirm the carbon source is suitable for the specific strain or cell type being studied [16]. |

| High background proliferation in label-retention assays (e.g., CFSE, PKH26). | Dye concentration too low; chase period insufficient; proliferating cells not adequately distinguished. | Increase dye concentration during initial labeling and extend the "chase" period to dilute the label in proliferating cells. Use flow cytometry gates to strictly separate bright (dormant) from dim (proliferated) populations [21]. |

| Failure to eradicate persisters with a candidate anti-persister compound. | Compound requires active metabolism for uptake or activity; compound is ineffective. | Consider combination therapy: Pair the compound with a metabolic activator (e.g., a carbon source) to "wake up" persisters, or use a membrane-active compound that works independently of metabolism [16] [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Dormancy Assays

Protocol 1: Generating and Isulating Bacterial Persister Cells via Antibiotic Selection

Principle: This method uses a high dose of a bactericidal antibiotic to kill the majority of the growing population, leaving behind tolerant persister cells.

Materials:

- Late-exponential or stationary phase bacterial culture (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus)

- Appropriate bactericidal antibiotic (e.g., Ciprofloxacin, Ampicillin)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or fresh medium

- Centrifuge

Procedure:

- Grow the bacterial culture to the desired phase (late-exponential phase often yields a higher persister frequency).

- Treat the culture with a high concentration of antibiotic (typically 10-100x the MIC) for a defined period (e.g., 3-5 hours).

- After incubation, pellet the cells by centrifugation.

- Wash the cell pellet twice with PBS or fresh medium to remove the antibiotic thoroughly.

- Resuspend the pellet in fresh medium. This surviving population is enriched for persister cells and can be used for downstream awakening or killing assays [16].

Protocol 2: Identifying Dormant Cancer Cells Using Label-Retention (CFSE Staining)

Principle: Proliferating cells dilute a fluorescent dye with each division, while dormant, non-dividing cells retain the label, allowing for their identification and isolation.

Materials:

- Cancer cell line of interest (in vitro or from a primary tumor)

- Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dye

- Cell culture medium and standard reagents

- Flow cytometer

Procedure:

- Harvest and wash the cells in PBS.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in pre-warmed PBS containing a low micromolar concentration of CFSE (e.g., 1-5 µM). Incubate for 15-20 minutes at 37°C.

- Quench the staining reaction by adding at least 5 volumes of complete culture medium and incubate for another 10 minutes.

- Wash the cells thoroughly to remove all free dye. This is the "pulse" step.

- Plate the labeled cells and culture for several days to weeks (the "chase" period). Allow proliferating cells to dilute the CFSE.

- Analyze the cells by flow cytometry. The population of cells that remains highly fluorescent (CFSE-high) represents the dormant, slow-cycling, or quiescent cells [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Dormancy and Metabolism Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| CFSE, PKH26, DiD Lipophilic Dyes | Fluorescent cell labels for tracking cell division and identifying dormant, label-retaining cells in vitro and in vivo [21]. |

| Cis-2-decenoic acid | A fatty acid signaling molecule that can induce the awakening of bacterial persister cells (e.g., in P. aeruginosa), sensitizing them to antibiotics [16]. |

| Mitomycin C | A DNA-cross-linking agent that can kill dormant persister cells independently of their metabolic state, effective against both planktonic and biofilm-derived persisters [16]. |

| ADEP4 | An acyldepsipeptide that activates the ClpP protease, leading to uncontrolled protein degradation and death of dormant bacteria, even without metabolic activity [16] [17]. |

| Pyrazinamide (PZA) | A frontline anti-tuberculosis drug; its active form, pyrazinoic acid, disrupts membrane energetics and targets PanD, showing efficacy against dormant M. tuberculosis [17]. |

| 3D Spheroid Culture Systems | In vitro models that better recapitulate the tumor microenvironment, including gradients of nutrients and oxygen, which are useful for studying cancer cell dormancy and quiescence [22]. |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Dormancy Induction Signaling Pathway

Dormancy Experiment Workflow

Linking Central Metabolism, the TCA Cycle, and Antibiotic Tolerance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental link between bacterial metabolism and antibiotic tolerance? Antibiotic tolerance is strongly associated with a low metabolic state in bacteria. Most clinically used antibiotics are effective against metabolically active cells but fail to kill dormant or slow-growing bacteria. Reduced metabolism, particularly through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, decreases cellular processes that antibiotics typically target, enabling survival during treatment [23] [24].

2. How does the TCA cycle directly influence antibiotic efficacy? The TCA cycle is a central hub of bacterial metabolism. Its activity is directly linked to cellular respiration and generation of proton motive force (PMF), which is required for the uptake of certain antibiotics like aminoglycosides. Retarded TCA cycle activity, for instance by metabolites like glyoxylate, decreases PMF and drug internalization, leading to tolerance [23].

3. What is the difference between antibiotic resistance and tolerance? Antibiotic resistance is the ability of bacteria to grow at high concentrations of an antibiotic, typically mediated by genetic mutations. Antibiotic tolerance refers to the ability of genetically susceptible bacteria to survive transient antibiotic exposure without growing, often through phenotypic changes like metabolic dormancy. They have unaltered Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values but survive treatment that kills their non-tolerant counterparts [23] [1].

4. Why are biofilms hotspots for antibiotic tolerance? Biofilms create heterogeneous microenvironments. Nutrient gradients within the biofilm structure lead to zones of slow growth or metabolic dormancy, particularly in deeper layers. This, combined with physical barriers from the extracellular matrix, protects bacterial cells from antibiotic killing and promotes the formation of persister cells [25] [26].

5. Can modulating substrate availability prevent tolerance? Yes, research indicates that exogenous metabolites can reactivate bacterial metabolism and re-sensitize tolerant cells. For example, providing specific amino acids, TCA cycle intermediates, or nucleotides can stimulate metabolic activity, making bacteria susceptible again to antibiotic killing [23].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Persister Cell Yields in Stationary Phase Cultures

- Potential Cause: Uncontrolled or undefined growth conditions leading to variable metabolic states.

- Solution: Standardize the growth conditions meticulously.

- Use a defined growth medium instead of complex broths like LB to ensure reproducible nutrient availability.

- Precisely control the incubation time for the stationary phase. The duration of nutrient starvation significantly impacts the proportion of type I (triggered) persisters.

- Monitor culture density (OD600) over time to establish a consistent harvest point [4] [24].

Problem: Failed Re-sensitization of Tolerant Cells with Metabolic Stimulants

- Potential Cause 1: The stimulant does not effectively reactivate the core metabolic pathways targeted by the antibiotic.

- Solution 1: Systematically test different classes of metabolites. Refer to Table 1 for metabolite selection and ensure they are used at physiological concentrations that do not independently inhibit growth [23].

- Potential Cause 2: The antibiotic's mechanism is not sufficiently dependent on bacterial metabolism.

- Solution 2: Characterize the metabolic dependence of your antibiotic. Use a control WDM antibiotic like mitomycin C to confirm that your tolerant population can be killed. Optimize your strategy based on the antibiotic class [27].

Problem: Poor Antibiotic Penetration in Biofilm Assays

- Potential Cause: The dense, charged extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix of the biofilm is binding or hindering the diffusion of the antibiotic.

- Solution:

- For biofilms known to have a high eDNA content (e.g., P. aeruginosa), consider adding low, non-bacteriolytic concentrations of DNase I to the treatment medium to degrade the matrix and improve penetration.

- Validate penetration issues by comparing killing efficacy with and without matrix-disrupting agents [25] [26] [28].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Evaluating the Role of Specific Metabolites in Re-sensitizing Tolerant Cells

Objective: To test if exogenous TCA cycle metabolites can reverse antibiotic tolerance.

- Induce Tolerance: Grow bacteria to stationary phase or under nutrient limitation (e.g., carbon source exhaustion) to generate a population with a high frequency of tolerant cells.

- Prepare Metabolites: Prepare sterile solutions of key metabolites (e.g., succinate, α-ketoglutarate, malate) in the appropriate buffer or minimal medium. Filter sterilize.

- Co-incubation: Incubate the tolerant cell population with a range of metabolite concentrations (e.g., 0.1-10 mM) in the presence of a bactericidal antibiotic. Include controls with metabolite alone and antibiotic alone.

- Viability Assessment: Perform time-kill assays. Take samples at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 24 hours, serially dilute, and plate for colony-forming unit (CFU) counts.

- Analysis: Compare the killing curves. A significant increase in killing rate in the presence of the metabolite indicates successful re-sensitization [23] [12].

Protocol 2: Assessing Metabolic Dependence of an Antibiotic

Objective: To classify an antibiotic as Strongly (SDM) or Weakly Dependent on Metabolism (WDM).

- Generate Metabolically Dormant Cells: Create a model tolerant population. This can be achieved by using a known ΔnhaA E. coli mutant, which has downregulated metabolism, or by harvesting cells from deep, nutrient-starved zones of a biofilm [27].

- Antibiotic Exposure: Treat the dormant population and a control, log-phase (metabolically active) population with the antibiotic of interest at a clinically relevant concentration (e.g., 10x MIC).

- Quantify Survival: After a set time (e.g., 6 hours), determine the survival rate via CFU counts.

- Classification: An antibiotic that kills dormant cells as effectively as active cells is classified as WDM (e.g., mitomycin C). An antibiotic that shows significantly reduced killing of dormant cells is classified as SDM (e.g., ampicillin) [27].

Quantitative Data on Metabolic Interventions

Table 1: Effect of Exogenous Metabolites on Antibiotic Tolerance

| Metabolite Class | Specific Example | Experimental Model | Effect on Tolerance | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCA Cycle Intermediates | Succinate, α-ketoglutarate | P. aeruginosa | Re-sensitization to tobramycin | Increased TCA cycle activity, elevated PMF, enhanced drug uptake [23] |

| TCA Cycle Modulator | Glyoxylate | P. aeruginosa | Induced tolerance to tobramycin | Retarded TCA cycle activity, decreased cellular respiration and PMF [23] |

| Amino Acids | Various | E. coli | Re-sensitization to fluoroquinolones | Activation of central metabolism, exit from dormancy [23] |

| Nucleotides | - | E. coli | Re-sensitization to fluoroquinolones | Activation of central metabolism, exit from dormancy [23] |

Table 2: Comparison of Antibiotics with Different Metabolic Dependencies

| Antibiotic | Metabolic Dependence | Efficacy Against Tolerant ΔnhaA E. coli | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Strong (SDM) | Low ( >1000-fold reduced killing) | Beta-lactam; fails against dormant populations [27] |

| Ciprofloxacin | Strong (SDM) | Low | Fluoroquinolone; fails against dormant populations [27] |

| Gentamicin | Weak (WDM) | High | Aminoglycoside; retains activity, but uptake requires PMF* [27] [23] |

| Mitomycin C | Weak (WDM) | High | Cytotoxic; cross-links DNA independently of metabolism [27] |

| Halicin | Weak (WDM) | High | Novel antibiotic; mechanism distinct from metabolic state [27] |

*Note: Gentamicin is classified as WDM in the cited study but is known to require PMF for uptake, highlighting context-dependent efficacy.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Metabolic Path to Antibiotic Tolerance

Strategies to Combat Tolerance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Metabolism and Tolerance

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Minimal Media | Provides controlled nutrient availability to precisely manipulate metabolic states and avoid undefined components in complex broths. | Studying the effect of specific carbon sources on TCA cycle activity and tolerance induction [23]. |

| TCA Cycle Metabolites (e.g., Succinate, α-Ketoglutarate) | Used as exogenous supplements to test if reactivation of specific metabolic pathways can reverse antibiotic tolerance. | Re-sensitizing dormant P. aeruginosa to aminoglycoside antibiotics [23]. |

| Keio Collection Knockout Mutants (e.g., ΔnhaA E. coli) | Pre-made gene deletion mutants to study the role of specific genes in metabolic regulation and tolerance without needing to construct mutants. | Validating the role of the nhaA gene in metabolic suppression and SDM antibiotic tolerance [27]. |

| Weakly Metabolism-Dependent Antibiotics (e.g., Mitomycin C) | Serve as positive controls in experiments to confirm that a bacterial population is susceptible to killing when metabolic dormancy is bypassed. | Differentiating between general cell death failure and metabolism-specific tolerance [27]. |

| DNase I | An enzyme that degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA), a key component of the biofilm matrix for some species. | Improving antibiotic penetration in biofilm assays for species like P. aeruginosa [25] [26]. |

| ATP Assay Kits | Quantify intracellular ATP levels as a direct, quantitative measure of a bacterial cell's metabolic activity and energy status. | Correlating the metabolic state (high vs. low ATP) of populations with their level of antibiotic tolerance [27]. |

Understanding the Persister Continuum: Frequently Asked Questions

What is the "Persister Continuum" hypothesis? The Persister Continuum hypothesis proposes that bacterial persisters exist in a spectrum of dormancy depths, rather than as a single, uniform state. This continuum ranges from "shallow" persisters, which are slow-growing and can resuscitate quickly, to "deep" persisters, which are metabolically dormant and resemble viable but non-culturable (VBNC) cells [29] [1]. The depth of dormancy influences how long a cell takes to resuscitate and its tolerance level to antibiotics.

How does substrate availability influence a cell's position on this continuum? Substrate availability is a primary environmental trigger that determines a cell's metabolic state and thus its position on the persister continuum. Nutrient-rich conditions typically promote active growth, while nutrient limitation or starvation pushes cells into deeper dormancy states [1] [4]. Optimizing substrate availability in experimental cultures is therefore critical for controlling the depth of dormancy and preventing the formation of deeply persistent subpopulations that are extremely difficult to eradicate.

What are the key differences between Type I, II, and III persisters in the context of this continuum? Within the continuum, persisters are often categorized based on their formation mechanisms, which correlate with different dormancy depths [4]:

- Type I (Triggered): Form in response to environmental stress (e.g., nutrient starvation) and are often deeply dormant.

- Type II (Stochastic): Arise spontaneously during exponential growth due to random fluctuations and are typically shallow persisters.

- Type III (Specialized): Induced by specific antibiotic-induced stress signals and may not be deeply dormant prior to exposure.

Why is it critical to distinguish between shallow and deep persisters in experimental outcomes? Distinguishing between shallow and deep persisters is essential because they respond differently to treatments and have varying resuscitation times [1]. An experimental treatment might effectively eliminate shallow persisters but fail against deep persisters, leading to a false positive result. Understanding the composition of the persister population in your model is key to developing effective anti-persister therapies.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent Persister Frequencies in Replicate Cultures

- Potential Cause: Stochastic formation of persisters and uncontrolled, minor fluctuations in the growth medium or substrate concentration.

- Solution:

- Standardize Inoculum: Always use cells from the same growth phase. The stationary phase is associated with a higher frequency of Type I persisters [4].

- Control Substrate: Use well-defined, fresh media for all experiments. Pre-condition cells in consistent nutrient environments to synchronize their metabolic states.

- Increase Biological Replicates: Due to the inherent stochasticity of persistence, a minimum of 3-5 biological replicates is recommended for reliable data.

Problem: Failure to Eradicate Persisters with Conventional Antibiotics

- Potential Cause: The persister population is dominated by deeply dormant cells that are not susceptible to antibiotics targeting active cellular processes.

- Solution:

- Profile Dormancy Depth: Use ATP assays or membrane potential dyes (e.g., DISC3(5)) to assess the metabolic activity of your persister population [7].

- Employ Anti-Persister Agents: Consider compounds that target dormant cells, such as membrane-disrupting agents [17] or compounds like ADEP4 which force uncontrolled protein degradation [17].

- Combine with Wake-Up Strategies: Use a "kick and kill" approach by first adding a metabolite like pyruvate or an appropriate carbon source to resuscitate shallow persisters, then applying a conventional antibiotic [7].

Problem: Inability to Resuscitate Surviving Cells After Antibiotic Treatment

- Potential Cause: The surviving cells may have entered a deep dormancy state, such as the VBNC state, from which they cannot be cultured on standard media [29].

- Solution:

- Extend Recovery Time: Allow for longer recovery periods in fresh, nutrient-rich media.

- Use of Resuscitation Promoters: Supplement recovery media with known resuscitation factors, such as sodium pyruvate or catalase, to counteract accumulated reactive oxygen species.

- Alternative Detection: Use viability staining (e.g., LIVE/DEAD BacLight) coupled with microscopy to confirm the presence of VBNC cells that are viable but not culturable [29].

Quantitative Data on Persister Survival

The table below summarizes key quantitative data on persister survival under different antibiotic treatments, which is essential for benchmarking your experimental results.

Table 1: Quantifying Persister Survival Under Antibiotic Exposure

| Bacterial Strain | Antibiotic & Concentration | Treatment Duration | Survival Frequency | Key Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli MG1655 (WT) [30] | Ampicillin (200 µg/mL, 12.5x MIC) | 3-5 hours | Multiphasic decay curve | Cells from exponential phase; most persisters were growing before treatment. |

| E. coli MG1655 (WT) [30] | Ciprofloxacin (1 µg/mL, 32x MIC) | 3-5 hours | Multiphasic decay curve | Cells from exponential phase; all identified persisters were growing before treatment. |

| E. coli HM22 (high-persistence) [7] | Eravacycline (100 µg/mL) | Not Specified | 99.9% killing | Treatment during "wake-up" phase; effective due to compound accumulation in persisters. |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis [29] | Various | Standard treatment | Up to 1% of population | Persisters are primary cause of refractory tuberculosis, found in granulomas. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation and Enumeration of Persisters via Antibiotic Killing Curves

This is a foundational method for quantifying persisters in a population [29] [30].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Antibiotic Stock Solutions: Prepare high-concentration stocks (e.g., 10-100 mg/mL) of bactericidal antibiotics like ampicillin or ciprofloxacin in appropriate solvents. Filter sterilize and store at -20°C.

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) or M9 Minimal Salts: For washing and diluting cells to remove nutrients and stop growth during antibiotic exposure.

- Neutralizing Agent: Sodium polyanethol sulfonate (SPS) or specific β-lactamase can be added to the plating media to neutralize antibiotic carryover during viability plating.

Methodology:

- Grow culture to the desired growth phase (exponential or stationary).

- Treat with a lethal dose of antibiotic (typically 10-100x MIC). Maintain a control without antibiotic.

- Incubate under optimal growth conditions with aeration for 3-24 hours.

- At designated time points, remove aliquots, wash twice with PBS to remove the antibiotic, and perform serial dilutions.

- Plate dilutions on fresh, antibiotic-free agar plates.

- Incubate plates and count colony-forming units (CFUs) after 24-48 hours.

- Plot the killing curve as log(CFU/mL) versus time. A biphasic curve, with an initial rapid kill followed by a slower second phase, indicates the presence of persisters.

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Analysis of Persister Dormancy Depth Using a Microfluidic Device

This advanced protocol allows for tracking the pre-history and fate of individual persister cells [30].

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Microfluidic Device: Such as a Membrane-Covered Microchamber Array (MCMA). The membrane allows for rapid medium exchange while trapping cells for imaging.

- Time-Lapse Microscopy Setup: An inverted microscope with a high-precision stage, camera, and environmental chamber (to maintain 37°C and CO₂).

- Fluorescent Stains: Membrane potential-sensitive dyes (e.g., DISC3(5)) or fluorescent protein reporters for stress genes (e.g., rpoS) can be used to correlate physiology with persistence.

Methodology:

- Load cells into the microchambers of the device.

- Perfuse with fresh growth medium and monitor single-cell growth and division to establish pre-treatment histories.

- Switch perfusion to medium containing a lethal antibiotic (e.g., 200 µg/mL ampicillin).

- Image continuously throughout the antibiotic treatment period (e.g., 5-10 hours).

- Switch back to fresh, antibiotic-free medium to monitor for resuscitation and regrowth.

- Analyze lineage data to correlate pre-antibiotic growth status (growing vs. non-growing) with survival outcomes, identifying different persister phenotypes.

Visualizing Key Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: The Persister Continuum and Fates

This diagram illustrates the metabolic states of cells along the persister continuum and their potential fates following antibiotic treatment and subsequent removal.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Profiling the Continuum

This diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental strategy to profile a bacterial population across the persister continuum, from culture to data analysis.

Quantifying and Modeling Substrate-Dependent Persister Dynamics

Stable Isotope Tracing (13C-Glucose/Acetate) to Map Metabolic Flux

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is stable isotope tracing particularly useful for studying metabolic perturbations that lead to bacterial persister formation? Stable isotope tracing allows for the direct measurement of metabolic flux, which is the dynamic flow of metabolites through metabolic pathways. In the context of persister formation—a state of metabolic dormancy and antibiotic tolerance—this technique can identify specific bottlenecks or rerouting in central carbon metabolism that occur as cells enter dormancy. Unlike static "snapshot" measurements (e.g., metabolite concentrations), flux analysis can reveal whether a change in metabolite level is due to increased production or decreased consumption, providing mechanistic insight into the metabolic state of pre-persisters and persisters that is crucial for designing strategies to optimize substrate availability and prevent persistence [31] [32].

Q2: What is the critical difference between metabolic steady state and isotopic steady state, and why does it matter for my persister study? These are two distinct concepts that are both critical for experimental design and data interpretation.

- Metabolic Steady State: This means that intracellular metabolite levels and metabolic fluxes are constant over time [31]. In practice, many systems are studied at a pseudo-steady state, where changes are minimal during the experiment.

- Isotopic Steady State: This is achieved when the enrichment of the heavy isotope (e.g., 13C) in a metabolite pool no longer changes over time [31]. For studies on persister formation, it is crucial to first establish that your system is at a metabolic (pseudo-)steady state before introducing the isotope tracer. This ensures that any measured labeling patterns reflect the fluxes of the metabolic state you intend to study. The time to reach isotopic steady state varies; glycolytic intermediates may reach it in minutes, while TCA cycle intermediates can take hours [31].

Q3: My mass spectrometry data shows labeling in metabolites, but the patterns are difficult to interpret. What is the most common oversight when processing this raw data? The most common oversight is a failure to properly correct the raw mass isotopologue distribution (MID) data for the presence of naturally occurring heavy isotopes [31] [33]. Elements like carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen have heavy but stable isotopes (e.g., 13C, 18O, 15N) that occur at low natural abundance. These atoms contribute to the mass signal, making it seem like your tracer has labeled a metabolite when it has not. This must be corrected computationally using algorithms in tools like PolyMID-Correct, IsoCor, or AccuCor to obtain the true MID resulting only from your administered tracer [33].

Q4: How can I use 13C-acetate to probe specific metabolic functions relevant to bacterial energy metabolism and persistence? 13C-acetate is a powerful tracer for studying the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and lipid synthesis. Upon uptake, acetate is converted to acetyl-CoA, which directly enters the TCA cycle. The labeling pattern from 13C-acetate (e.g., [1,2-13C]acetate or [U-13C]acetate) in TCA intermediates like citrate and α-ketoglutarate provides a direct readout of TCA cycle activity [34] [35]. Since persister cells often exhibit downregulated TCA cycle and energy metabolism, a reduction in 13C-incorporation from acetate into these intermediates is a key indicator of a shift toward metabolic dormancy. Furthermore, 13C-acetate is efficiently incorporated into fatty acids, allowing you to monitor the flux into membrane lipid biosynthesis, which may be altered in dormant cells [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor or Unpredictable Isotopic Enrichment

This problem manifests as low or inconsistent incorporation of the 13C label into your target metabolites.

Table: Troubleshooting Poor Isotopic Enrichment

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low label incorporation in all downstream metabolites | Tracer concentration is too low; cells are using unlabeled carbon sources. | - Determine the minimum tracer concentration required to achieve >90% enrichment in the initial metabolic node (e.g., Glucose 6-P for [U-13C]glucose) [37].- Use defined media and ensure the tracer is the principal carbon source for the pathway under investigation. |

| Enrichment is highly variable between replicates | System is not at a metabolic steady state; cell growth is inconsistent. | - Use controlled bioreactors (e.g., chemostats) or ensure cells are harvested during mid-exponential growth phase for pseudo-steady state [31] [37].- Monitor growth rate (OD600) and key extracellular rates (e.g., glucose consumption, lactate production) to confirm steady-state conditions. |

| Specific metabolites fail to label | Presence of large, unlabeled intracellular or extracellular pools diluting the tracer. | - For amino acids, this is a common issue due to exchange with media pools. Use dialyzed serum and label-free media formulations where possible [31].- Allow sufficient time for the label to reach isotopic steady state in the target pathway. |

Inconsistent or Noisy Flux Results

This issue arises when technical or biological variability leads to flux estimates with large confidence intervals.

Table: Troubleshooting Inconsistent Flux Results

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High measurement error in Mass Isotopologue Distributions (MIDs) | Inadequate analytical sensitivity; ion suppression in MS; poor chromatographic separation. | - Use chemical derivatization (e.g., for GC-MS) to improve sensitivity and separation [31].- Optimize LC-MS methods (e.g., HILIC for polar metabolites) to reduce ion suppression [34] [36].- Use multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) or parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) on triple-quadrupole or Q-Exactive instruments for higher sensitivity of target metabolites [34]. |

| Model fails to fit the data | Underdetermined system; metabolic network model is incorrect or incomplete. | - Use complementary tracers (e.g., [1,2-13C]glucose and [U-13C]glutamine) to provide more labeling constraints for the model [34] [37].- Incorporate external flux measurements (nutrient uptake, secretion rates, growth rate) as additional constraints to reduce the solution space [37]. |

| Large confidence intervals for estimated fluxes | The chosen tracer does not provide good resolution for the pathway of interest. | - For the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP), [1,2-13C]glucose provides better flux resolution than [U-13C]glucose because it generates distinct labeling patterns for glycolysis vs. PPP-derived lactate [34].- Select a tracer (or combination) based on a simulation of the expected labeling patterns for your hypothesized flux changes. |

Key Pathway Diagrams and Workflows

13C-Glucose Tracing Workflow

13C-Glucose and Acetate Metabolic Pathways

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for Stable Isotope Tracing Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 13C-Labeled Tracers ([U-13C]Glucose, [1,2-13C]Glucose, 13C-Acetate) | The core reagents used to trace carbon atoms through metabolic pathways. | - Purity and isotopic enrichment (>99%) are critical [33].- Select tracer based on pathway: [U-13C]glucose for general tracing; [1,2-13C]glucose for resolving PPP vs. glycolysis [34]. |

| Defined Culture Media | To control the availability of nutrients and ensure the tracer is the principal carbon source. | - Must be free of unlabeled compounds that could dilute the tracer (e.g., use dialyzed serum) [31] [37].- Allows for precise calculation of extracellular fluxes. |

| Mass Spectrometer | The primary instrument for measuring mass isotopologue distributions (MIDs). | - LC-MS (HILIC/RP) or GC-MS are standard [34] [36].- High-resolution instruments (Orbitrap, TOF) are preferred for untargeted work; triple-quadrupole for sensitive targeted assays [34] [36]. |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvents (e.g., Methanol, Acetonitrile) | To rapidly quench metabolism and extract intracellular metabolites from bacterial cells. | - Use cold (-20°C to -40°C) solvent for rapid quenching to preserve in vivo metabolic state [34].- Protocol should be optimized for bacterial cell wall lysis. |

| Data Correction Software (e.g., PolyMID-Correct, IsoCor) | Computationally removes the effect of naturally occurring heavy isotopes from raw MID data. | Essential for accurate data interpretation. Correction requires the exact chemical formula of the measured metabolite (or its derivative) [31] [33]. |

| Flux Analysis Software (e.g., INCA, Metran) | Integrated software platforms for performing 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA). | - Uses corrected MIDs and extracellular fluxes to calculate intracellular reaction rates [37].- Requires a defined metabolic network model of your organism. |

Agent-Based and Mathematical Models of Nutrient Gradients in Biofilms

This technical support center addresses the critical challenge of nutrient gradient control in biofilm research, a fundamental aspect for investigators aiming to optimize substrate availability to prevent persister cell formation. Bacterial persisters—dormant, transiently antibiotic-tolerant phenotypic variants—are a primary cause of chronic and relapsing infections [1] [4]. Their formation and survival are intrinsically linked to the heterogeneous microenvironment within biofilms, which is largely governed by the interplay between bacterial metabolism and the diffusion of nutrients and substrates [38] [39].

Agent-Based Models (ABMs) and other mathematical frameworks are indispensable tools for unraveling this complexity. These models treat each bacterial cell as an individual agent with defined properties and rules, allowing researchers to observe how large-scale community structures, such as nutrient gradients and sub-populations of persister cells, emerge from individual cellular behaviors [40] [41]. This technical resource provides troubleshooting guides, standardized protocols, and key reagent information to support the application of these models in your research, with the ultimate goal of designing interventions that disrupt the conditions leading to persistence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs essential computational and biological components frequently used in the development and validation of biofilm models concerning nutrient gradients and persistence.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools in Biofilm Modeling

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Nutrient Gradients & Persistence |

|---|---|---|---|

| iDynoMiCS [40] | Software Platform | An open-source agent-based modeling framework for simulating microbial systems. | Used to explore mechanisms like detachment and the role of cell aggregates in biofilm structure under nutrient limitation [40]. |

| NetLogo [14] | Software Platform | A programmable modeling environment for simulating natural and social phenomena, widely used for ABMs. | Enables the development of custom ABMs to test periodic antibiotic dosing regimens and their effect on persisters in structured biofilms [14]. |

| Spherocylindrical Particles [38] | Computational Cell Representation | A 3D geometric model (cylinder with hemispherical ends) used in Individual-based Models (IbM) to represent bacterial cells. | Allows for more realistic modeling of structural features in biofilms, coupling cell growth to local nutrient concentration [38]. |

| Monod Equation [38] [14] | Mathematical Kinetic Model | Describes the dependence of microbial growth rate on the local concentration of a limiting nutrient. | A fundamental equation implemented in ABMs to simulate how nutrient gradients lead to heterogeneous growth and dormancy within a biofilm [38] [14]. |

| Tet Operon Reporter [39] | Fluorescent Reporter System | A two-color plasmid (e.g., PR-GFP, PA-mCherry) reporting the expression and intracellular accumulation of tetracycline resistance genes. | Used in microfluidic studies to correlate spatial nutrient gradients with heterogeneous gene expression of antibiotic resistance mechanisms [39]. |

| Microfluidic Biofilm Trap [39] | Experimental Device | Creates confined, diffusion-limited environments for growing spatially extended microcolonies with defined nutrient gradients. | Provides experimental validation for models by allowing real-time observation of colony dynamics in response to controlled nutrient and antibiotic gradients [39]. |

Core Concepts & Signaling Pathways

Understanding the mechanistic link between nutrient availability and cellular dormancy is key. The following diagram synthesizes the primary signaling pathways that integrate environmental nutrient status with the regulatory networks leading to persister cell formation, as explored in both experimental and modeling studies.

Figure 1: Integrated Signaling Pathways in Nutrient-Linked Persister Formation. This diagram illustrates how nutrient limitation acts as a key environmental stressor, triggering intracellular signaling cascades that can lead to growth arrest and the formation of phenotypically heterogeneous persister cells.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Implementing a 3D Individual-Based Model (IbM) for Biofilm Nutrient Gradients

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a three-dimensional Individual-based Model to simulate the emergence of nutrient gradients and their effect on bacterial subpopulations, based on established methodologies [38] [42].

1. Model Initialization and Computational Domain Setup

- Define a three-dimensional computational space with a flat, impermeable substrate at the bottom (z=0).

- Set initial conditions by placing a small number of bacterial agents (e.g., 27 cells) randomly on the substrate surface to mimic initial adhesion [14].

- Overlay the domain with an aqueous solution representing the bulk liquid, which contains a defined initial concentration of the growth-limiting nutrient (e.g., carbon source) and oxygen [38] [42].

2. Agent (Bacterial Cell) Properties and Rules

- Represent each bacterial cell as a spherocylinder (a cylinder with hemispherical ends) with defined initial dimensions (e.g., aspect ratio L₀* = 2.6 for Pseudomonas putida) [38].

- Program agent growth using the Monod Kinetic Model. The growth rate of each cell is calculated as:

dmi/dt = mi * μmax * [C/(C + Ks)]wheremiis cell mass,μmaxis the maximal specific growth rate,Cis the local nutrient concentration, andKsis the half-saturation constant [14] [42]. - Implement cell division: when an agent's mass doubles, it divides into two daughter cells of equal or slightly randomized mass (e.g., 40%-60% split) [14].

3. Nutrient Diffusion and Consumption Dynamics

- Simulate the spatial and temporal distribution of nutrients by solving the reaction-diffusion equation:

∂C/∂t = Dₙ * ∇²C - ΣμᵢwhereDₙis the nutrient's diffusion coefficient,∇²is the Laplacian operator (modeling diffusion), andΣμᵢis the sum of nutrient uptake by all cells in a given volume [38]. - Calculate individual nutrient uptake

μᵢfor each cell also via a Monod-type function relative to its local environment [38].

4. Implementation of Dormancy and Persistence Logic

- Introduce rules for transitions to a dormant state based on testable hypotheses. Common implementations include:

- Nutrient-Dependent: A cell switches to a dormant state if the local nutrient concentration

Cfalls below a critical threshold (e.g.,C < C_crit) [42]. - Stochastic: Each active cell has a low, fixed probability per time step of switching to a persister state, independent of the environment [42].

- Time-Dependent: Cells that have been growth-arrested due to local conditions for a prolonged duration transition to dormancy [42].

- Nutrient-Dependent: A cell switches to a dormant state if the local nutrient concentration

5. Simulation Execution and Data Collection

- Run the simulation with a finite difference numerical scheme, using a time step sufficiently small to ensure stability.

- At defined intervals, collect quantitative data on: biofilm biovolume and thickness, spatial distribution of nutrient concentrations, and the number and location of dormant vs. active cells.

Protocol: Experimental Validation Using Microfluidic Cultivation

This protocol describes the use of a microfluidic device to cultivate biofilms with controlled nutrient gradients, enabling direct observation and validation of model predictions [39].

1. Device Fabrication and Preparation

- Fabricate a microfluidic device featuring one or more cultivation traps (e.g., 170 μm deep, 100 μm wide) connected to nutrient supply channels using standard soft lithography techniques with Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [39].

- Bond the PDMS device to a glass coverslip to create sealed channels. Sterilize the device before use, typically by autoclaving or flushing with ethanol.

2. Bacterial Strain and Inoculation

- Use a relevant bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli). For studies on resistance dynamics, employ a strain carrying a fluorescent reporter system for a gene of interest (e.g., TetA-mCherry for tetracycline resistance) [39].

- Dilute an overnight culture to a low optical density and inject it into the device's main channel, allowing cells to settle into the traps by gravity or flow.

3. Establishing Steady-State Nutrient Gradients

- Continuously perfuse the supply channels with fresh growth medium at a controlled, low flow rate. This creates a diffusion-limited environment where nutrients are consumed as they penetrate the trap, generating a stable gradient from the open edge to the interior [39].

- Allow the colony to grow for 24-48 hours until it fills the trap and reaches a steady state, characterized by a clear boundary between fast-growing cells near the nutrient source and slow-growing or dormant cells in the interior.

4. Real-Time Monitoring and Perturbation

- Place the device on a temperature-controlled stage of an inverted fluorescence/phase-contrast microscope.

- Monitor cell growth, morphology, and fluorescence reporter expression in real time using time-lapse microscopy.

- To test model predictions or treatment efficacy, rapidly switch the inlet tubing to medium containing an antimicrobial agent or a different nutrient composition. The device design allows for swift changes in the bulk condition [39].

5. Image and Data Analysis

- Use Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) algorithms on time-lapse images to quantify cellular displacement and calculate local growth rates throughout the colony [39].

- Quantify fluorescence intensity to map the spatial expression patterns of resistance or stress genes in response to the nutrient gradient and any applied perturbations.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: Our ABM simulations consistently predict uniform, homogenous biofilms without the expected nutrient gradients and stratified dormant regions. What could be wrong?

- Check Nutrient Consumption Parameters: The most common cause is an imbalance between nutrient diffusion and consumption. Verify that your maximum nutrient uptake rate (

μ_maxorq_max) is sufficiently high relative to the diffusion coefficient (Dₙ). If uptake is too slow, nutrients will not be depleted in the biofilm interior. Consult literature for realistic parameter values [38]. - Verify Diffusion Coefficient: Ensure the diffusion coefficient used for the biofilm interior is significantly lower than that in the bulk liquid to account for the hindrance caused by the extracellular polymeric matrix [38].

- Increase Biofilm Size: The gradients may not have space to develop if the simulation domain or time is too small. Allow the biofilm to grow thicker, as stratification is more apparent in larger colonies [38].

Q2: When we apply an antibiotic in our model, it clears the biofilm too effectively and does not match experimental observations of persister survival. How can we improve the model?

- Implement Persister-Specific Killing Rates: Model susceptible and persister cells as having different death rates upon antibiotic exposure. Persister death rates should be several orders of magnitude lower [14].

- Review Persister Induction Logic: The rules for forming persisters might be insufficient. Ensure you are modeling the correct type (e.g., type I vs. type II) and that the switching rates (to and from persistence) are calibrated to experimental data [1] [42]. Incorporating both stochastic and nutrient-dependent switching can enhance realism [14] [42].

- Confirm Antibiotic Diffusion/Penetration: If the antibiotic does not fully penetrate the biofilm, it will not reach all cells. Model antibiotic diffusion and potential binding/degradation to create sanctuaries where persisters can survive [40].

Q3: In our microfluidic experiments, we do not observe a clear nutrient gradient or distinct growth zones in the trap. What are potential causes?

- Check for Flow Rate Issues: If the flow rate is too high, it can flush away the gradient and create a well-mixed environment. Conversely, if it's too low, waste products may accumulate and confound results. Optimize the flow rate to be low enough to be diffusion-limited but high enough to prevent waste accumulation [39].

- Verify Trap Geometry and Cell Density: The trap might be too shallow or wide to establish a strong gradient. Ensure the cell density is high enough to consume nutrients significantly as they diffuse inward [39].

- Confirm Nutrient Concentration: The initial nutrient concentration in the medium might be too high, preventing depletion. Consider using a more minimal or nutrient-limited medium.

Q4: What are the key quantitative parameters we need to extract from the literature to parameterize a realistic ABM of nutrient gradients? The following table summarizes critical parameters and their typical roles in model behavior.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters for ABM of Biofilm Nutrient Gradients

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Impact on Model | Exemplary Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max. Specific Growth Rate | μ_max |

Maximum rate of cell mass increase. | Controls speed of biofilm development and nutrient consumption. | Monod Kinetics [14] |

| Half-Saturation Constant | K_s |

Nutrient conc. at half μ_max. |

Determines sensitivity of growth to low nutrient levels. | Monod Kinetics [14] |

| Nutrient Diffusion Coefficient | D_n |

Measure of nutrient mobility in biofilm. | Lower values lead to steeper gradients and larger dormant zones. | [38] |

| Max. Nutrient Uptake Rate | q_max |

Maximum rate of nutrient consumption per cell. | High rates promote faster nutrient depletion and stratification. | [38] [42] |

| Critical Nutrient Threshold | C_crit |

Nutrient level below which dormancy is triggered. | Directly sets the location and size of the dormant region. | Hypothesis-driven [42] |

| Stochastic Persister Switch Rate | P_switch |

Probability of a cell becoming a persister per unit time. | Governs the baseline level of persistence in active regions. | [14] [42] |

Advanced Analysis: Optimizing Anti-Persister Strategies

The ultimate goal of modeling is to inform effective strategies. A key application is optimizing treatment schedules. The following diagram outlines the workflow for using an ABM to design and test a periodic antibiotic dosing regimen aimed at eradicating persisters by exploiting their "reawakening" phase.

Figure 2: Workflow for ABM-Guided Optimization of Periodic Dosing. This logic flow depicts how agent-based models can be iteratively used to design treatment schedules that capitalize on the dynamic nature of persister cells, potentially reducing the total antibiotic dose required for eradication [14].

Research demonstrates that this approach can be highly effective. One ABM study found that by carefully tuning the timing of periodic antibiotic doses to align with the dynamics of persister resuscitation, the total dose required for effective treatment could be reduced by nearly 77% compared to continuous treatment, without compromising efficacy [14]. This highlights the powerful predictive potential of integrating realistic nutrient-gradient and persistence models into therapeutic planning.

Measuring Environment-Dependent Switching Rates Between Cell States

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between bacterial persister cells and antibiotic-resistant bacteria? Persister cells are phenotypic variants of genetically drug-susceptible bacteria that survive antibiotic exposure by entering a transient, dormant state. They are characterized by tolerance, not resistance. Unlike resistant bacteria, which have a higher minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), persisters do not grow in the presence of the drug but remain susceptible to it once the antibiotic is removed and they resume growth [5] [1]. This tolerance is often linked to slowed metabolism, a state which can be influenced by environmental factors like substrate availability [5].

FAQ 2: How do environmental stresses like substrate limitation trigger the formation of persister cells? Substrate limitation and other environmental stresses (e.g., nutrient starvation, acidic pH) activate key bacterial stress response pathways. A central mechanism is the stringent response, where nutrient scarcity leads to the accumulation of (p)ppGpp. This alarmone triggers a dramatic slowdown of cellular metabolism and growth, facilitating the transition to a dormant, persister state. This state protects bacteria because most antibiotics target active cellular processes [5] [1].

FAQ 3: What are the main types of persisters, and how do they relate to my experiments? Persisters exist on a continuum, but two primary categories are often described [1]:

- Type I Persisters: Form in response to a specific external environmental trigger, such as entering the stationary phase due to nutrient exhaustion. They are typically pre-formed before antibiotic exposure.

- Type II Persisters: Form spontaneously during balanced growth without an external trigger. These are often slow-growing or non-growing cells within an otherwise active population. Your experimental setup (e.g., batch culture growth phase, continuous culture parameters) will influence which type you predominantly study.

FAQ 4: Why is measuring cell state switching rates to and from the persister state critical for my research? Quantifying switching rates is essential for:

- Understanding Persistence Dynamics: It moves research from a static snapshot (persister frequency) to a dynamic understanding of how quickly cells enter and exit the dormant state.

- Predicting Treatment Outcomes: The rate of switching back to an active state can determine the likelihood of infection relapse after antibiotic therapy is stopped.

- Identifying Therapeutic Targets: Interventions aimed at reducing the rate of entry into persistence or increasing the rate of exit could make infections more susceptible to conventional antibiotics.

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Persister Cell Yields in Stationary Phase Cultures

Problem: The proportion of persister cells isolated from stationary-phase cultures is consistently lower than expected, making downstream analysis difficult.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inconsistent Culture Conditions.

- Solution: Standardize the growth medium, temperature, and shaking speed. Precisely define the "stationary phase" by optical density (OD) and duration to ensure reproducibility between experiments.

- Cause 2: Ineffective Antibiotic Selection.

- Solution: Verify the concentration and stability of the bactericidal antibiotic used for selection. Use a concentration that is 10x the MIC and confirm its activity. Ensure exposure time is sufficient to kill all growing cells but not so long as to start killing persisters.

- Cause 3: Suboptimal Growth Phase Harvesting.

- Solution: The proportion of persisters increases from mid-log to a peak in the stationary phase [5]. Perform a time-course experiment to determine the optimal harvesting point for your specific bacterial strain.