The Biofilm Barrier: Decoding Matrix Composition and Its Role in Antibiotic Treatment Failure

Biofilms, structured communities of microbes encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix, represent a primary driver of antibiotic treatment failure in chronic infections.

The Biofilm Barrier: Decoding Matrix Composition and Its Role in Antibiotic Treatment Failure

Abstract

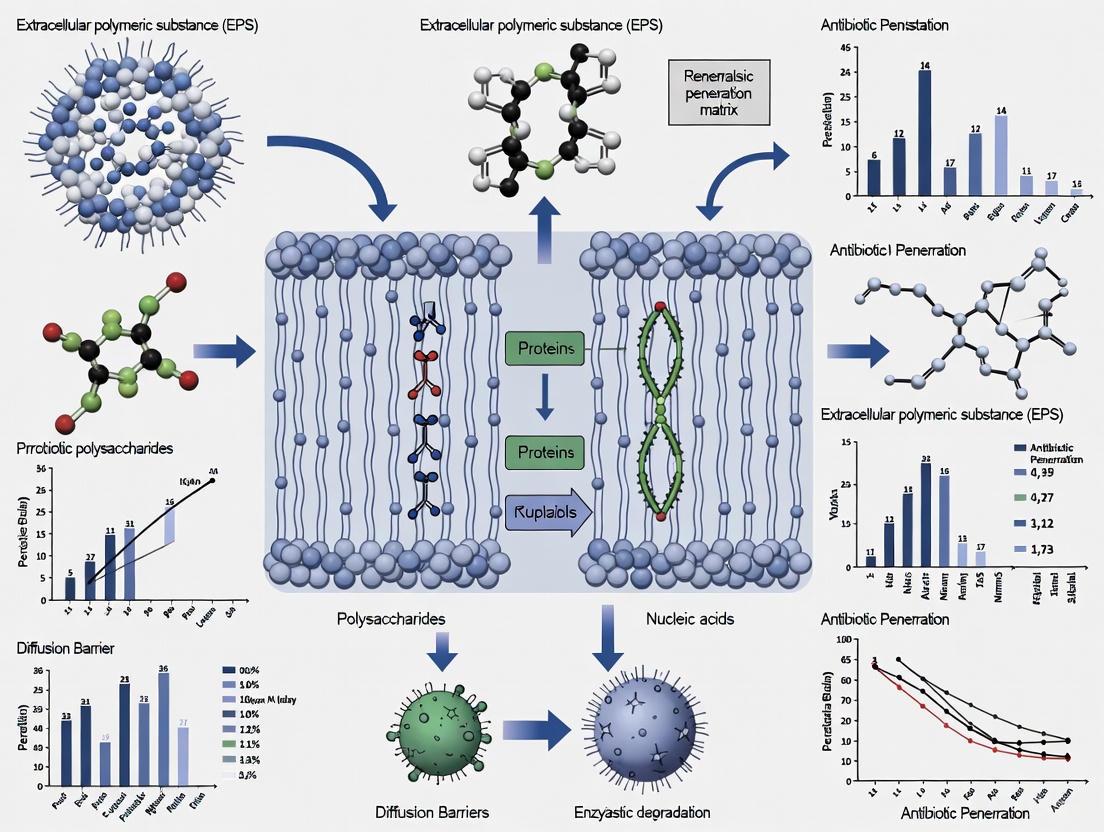

Biofilms, structured communities of microbes encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix, represent a primary driver of antibiotic treatment failure in chronic infections. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the intricate relationship between biofilm matrix composition and impaired antibiotic penetration. We first deconstruct the foundational architecture of the biofilm matrix, detailing its key components—exopolysaccharides, proteins, eDNA, and lipids—and their collective role in creating a physical and functional barrier. The review then transitions to methodological approaches for studying antibiotic diffusion and efficacy, followed by an critical examination of the multifaceted resistance mechanisms, including hindered diffusion, enzymatic inactivation, and metabolic heterogeneity. Finally, we evaluate and compare emerging therapeutic strategies, from matrix-degrading enzymes and nanoparticle-based delivery systems to quorum-sensing inhibitors and combinatorial therapies, offering a validated perspective on the future of anti-biofilm drug development.

Deconstructing the Fortress: An Architectural Guide to the Biofilm Matrix

Core Components of the Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS)

The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) is a complex, self-produced matrix that encompasses microbial cells within a biofilm, serving as the primary architectural and functional component of this aggregated community [1] [2]. This organic polymer matrix of microbial origin is critical for establishing and maintaining the biofilm structure, conferring stability, cohesion, and viscoelasticity to the entire system [1]. The EPS matrix represents a key element in the biofilm's defensive strategy, creating a protected microenvironment that significantly contributes to intrinsic resistance against antimicrobial agents [2]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of EPS core components, their physicochemical properties, and their collective role in hindering antibiotic penetration, all within the context of advancing biofilm matrix composition and antibiotic resistance research.

Core Biochemical Composition of EPS

EPS are organic polymers comprised of a diverse array of biopolymers that interact to form a protective hydrogel matrix. The composition is highly dynamic, varying based on microbial species, environmental conditions, and growth phase [2] [3].

Table 1: Primary Constituents of Microbial EPS

| Component | Relative Abundance | Key Functional Groups | Major Functional Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | Often dominant (variable) | Hydroxyl, Carboxyl, Uronic acids | Structural integrity, hydration, adhesion [3] [4] |

| Proteins | 15%-75% (can be dominant) | Amino, Carboxyl, Sulfhydryl | Structural support, enzymatic activity, adhesion [5] [3] |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | 1%-10% (variable) | Phosphate (negative charge) | Polymer entanglement, cation exchange, genetic info [1] [2] |

| Lipids | Variable (often minor) | Alkyl chains | Hydrophobicity, surface attachment [1] [3] |

| Humic-like Substances | Variable in environmental biofilms | Phenolic, Quinoid | Redox activity, metal binding [6] |

Polysaccharides

Exopolysaccharides form the sugar-based backbone of many EPS matrices, consisting of monosaccharides (e.g., glucose, galactose, mannose) and non-carbohydrate substituents including acetate, pyruvate, and succinate [3]. These polymers can be linear or branched and are frequently anionic due to the presence of uronic acids (e.g., glucuronic acid) or ketal-linked pyruvates, contributing to their cation-exchange capacity and gel-forming properties [3] [4]. Notable examples include alginate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) in Staphylococcus epidermidis, and cellulose in Acetobacter xylinum [2] [3].

Proteins

The proteinaceous component of EPS includes structural proteins and extracellular enzymes (exoenzymes) [3]. Structural proteins often contain repetitive sequences and facilitate surface adhesion and cell-to-cell interactions [2]. Exoenzymes such as proteases, glycosidases, and phosphatases remain active within the matrix, performing critical functions in nutrient acquisition by breaking down complex organic molecules into assimilable subunits [5] [3]. These enzymes also contribute to biofilm remodeling and detachment [1].

Extracellular DNA (eDNA)

eDNA is released into the matrix through cell lysis and active secretion [2]. It functions as a structural cross-linking agent, particularly in biofilms of species like Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [2]. The negatively charged phosphate groups of eDNA engage in electrostatic interactions with other EPS components and cationic antimicrobials, such as aminoglycosides, effectively trapping them and reducing their penetration [2].

Other Components

Lipids, though typically a minor component, can increase matrix hydrophobicity, influencing surface attachment and resistance to hydrophobic antibiotics [1] [3]. Humic-like substances, prevalent in environmental biofilms, contribute to the matrix's electron-transfer capabilities and can bind various contaminants [6].

Quantitative Analysis of EPS Composition

The relative proportions of EPS constituents vary significantly across microbial species and environmental conditions. Technical quantification is essential for understanding structure-function relationships.

Table 2: Quantitative EPS Composition from Selected Systems

| Biological System / Condition | Proteins (%) | Polysaccharides (%) | eDNA/Lipids/Other | Protein/Polysaccharide Ratio | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Microbial EPS | 15-75 | 15-75 | 1-10% eDNA, variable lipids | Highly variable (0.2-5.0) | [5] [3] [7] |

| Anammox Granular Biofilm | ~60-75 (of total organic matter) | ~25-40 (of total organic matter) | Not specified | ~1.5 - 3.0 | [6] |

| Fusarium culmorum (Pathogen) | Variable | High total sugar, rich in mannose | Phenolic components | Variable, strain-dependent | [4] |

| E. coli (Lab Culture) | ~10% (by dry weight) | ~30% (by dry weight) | Not specified | ~0.33 | [8] |

Factors Influencing Composition

EPS composition is not static but responds dynamically to environmental cues. Stress conditions such as nutrient limitation, presence of toxins (e.g., antibiotics, heavy metals), and osmotic stress can trigger significant shifts in EPS production and composition [5] [4]. For instance, the protein/polysaccharide ratio can indicate the physiological state of the biofilm, with a decrease potentially signaling preferential polysaccharide production [1].

Functional Properties and Role in Antibiotic Resistance

The EPS matrix acts as a multifaceted barrier against antimicrobial agents, employing several mechanisms that collectively contribute to the remarkable tolerance of biofilms to antibiotic treatments [2] [9].

Physical Barrier and Retarded Diffusion

The dense, highly hydrated network of EPS creates a physical diffusion barrier that significantly slows the penetration of antimicrobial molecules into the deeper layers of the biofilm [2] [9]. This retarded diffusion is influenced by factors such as biofilm thickness, matrix porosity, and the physicochemical properties of the antibiotic itself [9]. Positively charged aminoglycosides, for example, are particularly susceptible to binding with negatively charged polymers like eDNA and alginate within the matrix, leading to their sequestration before reaching cellular targets [2].

Chemical Interactions and Sequestration

EPS components provide abundant functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl, amine, phosphoryl) that serve as binding sites for antibiotics [5]. The primary mechanisms of antibiotic adsorption onto EPS include electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and surface complexation [5]. Proteins in EPS often exhibit a higher binding strength and capacity for antibiotics like tetracycline and sulfamethazine compared to humic-like organics, playing a predominant role in this sequestration process [5].

Physiological and Metabolic Heterogeneity

As antibiotics penetrate the biofilm, they encounter gradients of nutrients, oxygen, and waste products, leading to zones of varying metabolic activity [9]. Cells in the deep, nutrient-depleted layers of the biofilm often enter a slow-growing or dormant state, making them less susceptible to antibiotics that target active cellular processes [9]. These conditions promote the formation of persister cells—dormant variants that exhibit high tolerance to antibiotics and can repopulate the biofilm after treatment cessation [9].

Analytical Methods for EPS Characterization

A combination of destructive and non-destructive analytical techniques is employed to elucidate the composition, structure, and function of EPS.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy is a powerful, non-destructive technique that provides information about the chemical content and relative proportions of different EPS constituents based on their functional groups' absorption of infrared radiation [1].

- Experimental Protocol: Biofilm samples can be analyzed in situ under hydrated conditions using Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) mode, which probes approximately the first 2 µm of the surface layer. Alternatively, dried mature biofilms can be analyzed to reduce the confounding effect of water [1].

- Spectral Interpretation: Key spectral windows include:

- 2800–3000 cm⁻¹: C-H stretching vibrations, primarily from lipids.

- 1500–1800 cm⁻¹: Amide I (C=O) and Amide II (N-H) bands from proteins.

- 900–1250 cm⁻¹: C-O, C-O-C stretching, and P=O stretching from polysaccharides and nucleic acids [1].

- Data Analysis: Monitoring the evolution of band intensity ratios (e.g., Amide II/Polysaccharide) over time can reveal shifts in biofilm composition, such as preferential polysaccharide production (ratio decrease) or protein accumulation (ratio increase) [1].

EPS Extraction and Quantitative Analysis

To determine the absolute abundance of EPS components, physical and/or chemical extraction methods are required, followed by quantitative assays.

- Extraction Protocol: A common method involves low-speed centrifugation (e.g., 3000 × g for 10 min) to separate cells from the bulk liquid. The harvested cells are washed and resuspended in a suitable buffer (e.g., ultrapure water or NaCl). EPS are then separated from the cells via sonication (e.g., 2.7 W/cm², 40 Hz, 10 min at 4°C) followed by high-speed centrifugation (e.g., 10,600 × g for 20 min) [8]. The supernatant containing the EPS is filtered (0.45 µm) to remove any remaining cells.

- Quantification of Components:

- Proteins: Commonly measured using the Lowry or Bradford assays, with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

- Polysaccharides: Often quantified by the phenol-sulfuric acid method, with glucose or other relevant sugars as standards.

- eDNA: Can be quantified using fluorescent dyes like PicoGreen after purification [6].

- Advanced Qualitative Techniques:

- Three-Dimensional Excitation-Emission Matrix (3D-EEM) Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Identifies and characterizes fluorescent organic compounds like specific protein motifs (tryptophan/tyrosine) and humic-like substances [6].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Provides information about the apparent molecular weight distribution of EPS polymers [6].

- Hydrophobicity Measurement: Determined by contact angle measurement or hydrophobic interaction chromatography [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Methods for EPS Research

| Reagent / Method | Function in EPS Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cation Exchange Resin | Extracts EPS from microbial aggregates by disrupting ionic bonds. | Minimizes cell lysis compared to chemical methods [6]. |

| Sonication Bath | Physically shears EPS from cell surfaces during extraction. | Power and duration must be optimized to avoid cell disruption [8]. |

| ATR/FT-IR Spectroscopy | Provides in-situ, non-destructive analysis of biofilm chemical composition. | Germanium crystals are common Internal Reflection Elements (IRE) [1]. |

| Fluorescence Spectrophotometer | Used for 3D-EEM to characterize protein and humic components. | Can identify specific fluorophores based on excitation/emission pairs [6]. |

| Hydrolytic Enzymes (e.g., Proteases, DNases, Amylases) | Selectively degrades specific EPS components to study their functional role. | Used to test biofilm destabilization and component involvement in integrity [1]. |

| Propidium Iodide | Fluorescent dye used to assess cell membrane permeability and viability. | Can be used to correlate EPS removal with increased cell permeability [8]. |

The extracellular polymeric substance is a sophisticated biological construct whose core components—polysaccharides, proteins, eDNA, and lipids—operate in concert to form a dynamic and protective matrix. The quantitative and qualitative characterization of these components reveals a system engineered for resilience, directly contributing to the challenge of treating biofilm-associated infections through mechanisms of physical blockage, chemical interaction, and induction of microbial physiological heterogeneity. A deep understanding of EPS composition and function, enabled by the detailed methodologies outlined herein, is paramount for the future development of targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at disrupting this critical barrier and overcoming antibiotic resistance in biofilms.

Spatial Organization and the 3D Structural Scaffold

The spatial organization and three-dimensional structural scaffold of biofilms represent a fundamental pillar of microbial life, underpinning the remarkable resilience of these communities to antimicrobial agents. Within the context of biofilm matrix composition and antibiotic penetration resistance research, understanding this sophisticated architecture is paramount. The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix forms a complex, heterogeneous scaffold that not only provides structural integrity but also creates formidable physical and chemical barriers to antibiotic penetration [10]. This organized ecosystem, characterized by gradients of nutrients, oxygen, and metabolic activity, enables microbial populations to survive concentrations of antimicrobials that would readily eliminate their planktonic counterparts [11]. The 3D organization of biofilms thus presents a critical challenge in clinical and industrial settings, driving the urgent need for advanced analytical techniques to decipher its intricacies and overcome the therapeutic failures associated with biofilm-mediated resistance.

Matrix Composition: The Building Blocks of the Biofilm Scaffold

The biofilm scaffold is an amalgamation of microbial cells and self-produced extracellular substances, creating a heterogeneous structure with significant architectural complexity. Biofilms are primarily composed of microbial cells (10-25%) embedded within an EPS matrix (75-90%) that is predominantly water (up to 97%) [10]. This EPS forms a protective scaffold that holds the biofilm together through various intermolecular forces, including van der Waals interactions, electrostatic forces, and hydrogen bonding [10].

Table 1: Key Components of the Biofilm Extracellular Polymeric Substance Matrix

| Component | Percentage | Primary Functions | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | 1-2% | Structural backbone, adhesion, cohesion, protection | Pel, Psl, alginate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa; cellulose, glucans [10] |

| Proteins | <1-2% | Matrix stabilization, enzymatic activity, surface colonization | Cell surface adhesins, proteases, glycosyl hydrolases, disulfide-isomerases [10] |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | <1-2% | Structural cohesion, horizontal gene transfer, antibiotic chelation | DNA from lysed cells, contributes to antimicrobial resistance [11] [10] |

| Lipids | Variable | Hydrophobicity, barrier functions | Influence biofilm hydrophobicity and permeability [11] |

| Inorganic Ions | Variable | Matrix cross-linking, mineralization | Calcium, magnesium facilitate component cross-linking [11] |

The compositional profile of the EPS is not static but dynamically adapts to environmental conditions. For instance, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, three exopolysaccharides—Pel, Psl, and alginate—play distinct yet complementary roles in maintaining biofilm architecture and conferring resistance properties [10]. Similarly, extracellular proteins contribute to structural integrity through interactions with polysaccharides and nucleic acids, while some specialized proteins facilitate matrix degradation and dispersal when environmental conditions favor biofilm dissemination [10].

Methodologies for Spatial Analysis of Biofilm Architecture

Advanced Imaging and Computational Analysis

Deciphering the spatial organization of biofilms requires sophisticated imaging technologies coupled with powerful computational tools. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) has proven invaluable for visualizing the 3D architecture of biofilms without disrupting their native structure, revealing multiple layers with distinct ecological niches occupied by different bacterial species [11]. This spatial heterogeneity creates microenvironments with varying nutrient gradients, oxygen levels, and metabolic activities that fundamentally influence biofilm function and pathogenicity [11].

For comprehensive quantitative analysis, BiofilmQ software provides an advanced image cytometry platform specifically designed for 3D microbial communities [12]. This tool enables automated high-throughput quantification of numerous biofilm-internal and whole-biofilm properties, including:

- Structural parameters: Volume, mean thickness, surface area, roughness coefficient, and surface-to-volume ratio

- Spatially resolved properties: Gradient analyses of fluorescent reporters, distance to biofilm outer surface or substratum

- Correlation metrics: Species cluster sizes and separation distances in multispecies biofilms using 3D correlation functions [12]

The software employs cube-based image cytometry, dissecting the biofilm biovolume into a cubical grid with user-defined dimensions, enabling 3D spatially resolved quantification even in images where single-cell segmentation is not possible [12]. For higher resolution images, users can import custom-segmented biofilm images, including those generated by convolutional neural networks like U-Net, which offer improved segmentation accuracy for specific biofilm morphologies [12].

Accessible Staining and Visualization Techniques

While advanced microscopy offers unparalleled resolution, practical constraints often necessitate simpler methodologies for routine biofilm analysis. The dual-staining protocol using Maneval's stain and Congo red provides a cost-effective alternative for visualizing and differentiating microbial biofilms with basic laboratory equipment [13]. This method effectively distinguishes bacterial cells (magenta-red) from the biofilm matrix (blue) in a single stain, with the complete process requiring only 30-45 minutes [13].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Biofilm Spatial Analysis

| Method | Key Applications | Technical Requirements | Output Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| BiofilmQ Software Analysis | High-throughput 3D quantification of biofilm architecture | Fluorescence images, standard computer | 49+ structural, textural, and fluorescence properties; population analysis; temporal tracking [12] |

| Dual Staining with Maneval's Stain | Differentiation of bacterial cells vs. matrix; capsule visualization | Light microscope, basic stains | Color differentiation: blue matrix vs. magenta-red cells; identification of halo formation indicating capsules [13] |

| Microtiter Plate Biofilm Assay | Semiquantitative assessment of adherent biomass | 96-well plates, crystal violet, plate reader | Optical density measurements of stained biofilms; high-throughput capability [14] |

| Colony-Based Biofilm System | Monitoring cell death in antimicrobial treatments | Agar plates, viability stains | Viability counts; antimicrobial efficacy assessment [14] |

The technical workflow for the dual-staining method begins with biofilm growth on glass slides submerged in diluted culture broth for 3 days at 37°C, followed by gentle rinsing, fixation with 4% formaldehyde, and sequential staining with Congo red and Maneval's stain [13]. This approach allows researchers to identify distinct stages of biofilm development—from early cobweb-like structures through intermediate clustered stages to mature honeycomb-like architectures with well-defined channels [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biofilm Spatial Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| BiofilmQ Software | 3D image cytometry and analysis of microbial communities | Quantitative analysis of spatially resolved structural parameters; available at https://drescherlab.org/data/biofilmQ [12] |

| Maneval's Stain | Differential staining of bacterial cells and matrix | Composition: 0.05 g fuchsin, 3.0 g ferric chloride, 5 mL acetic acid, 3.9 mL phenol, 95 mL distilled water [13] |

| Congo Red Stain | Polysaccharide matrix staining | 1% solution in distilled water; interacts with hydrophobic regions of polysaccharides through hydrogen bonds [13] |

| Crystal Violet | Biomass staining for microtiter plate assays | 0.1% solution in water; stains adherent cells for semiquantitative assessment [14] |

| 96-Well Microtiter Plates | High-throughput biofilm cultivation | Non-tissue culture treated plates (e.g., Becton Dickinson #353911) for static biofilm assays [14] |

| Solvents for Dye Elution | Solubilization of stained biofilms for quantification | 30% acetic acid, 95% ethanol, or 100% DMSO; choice is organism-dependent [14] |

Architectural Dynamics and Functional Consequences

The spatial organization of biofilms is not merely structural but fundamentally functional, creating heterogeneous microenvironments that drive microbial behavior and therapeutic resistance. The 3D architecture typically features water channels separating microcolonies, enabling nutrient circulation and waste removal [10]. This organization often follows a stratification pattern where early colonizers such as Streptococcus spp. consume oxygen, creating anaerobic niches that support pathogenic obligate anaerobes implicated in periodontal disease [11].

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in the development of this complex spatial architecture:

This developmental process culminates in a mature biofilm that may acquire "mushroom" or "tower" shaped structures where microorganisms arrange themselves according to aero-tolerance and metabolic rates [10]. The resulting spatial heterogeneity creates diffusion barriers that significantly impede antibiotic penetration, while the varied metabolic states of cells in different regions reduce antimicrobial susceptibility [11] [10]. Additionally, the EPS components can directly bind and neutralize certain antimicrobial compounds, further enhancing the protective function of the biofilm scaffold [10].

The spatial organization and 3D structural scaffold of biofilms represent a sophisticated adaptation that continues to challenge conventional antimicrobial strategies. As research progresses, the integration of advanced imaging technologies with computational analytics like BiofilmQ promises to unravel the complex architecture-function relationships that underpin biofilm resilience [12]. Emerging therapeutic approaches are increasingly targeting the structural integrity of biofilms through enzymatic matrix degradation, quorum sensing inhibition, and disruption of spatial organization mechanisms [10] [15]. The continuing refinement of accessible methodologies, such as the dual-staining technique using Maneval's stain, will enable broader screening capabilities across diverse laboratory settings [13]. Ultimately, overcoming the barrier presented by biofilm spatial organization will require multidisciplinary approaches that bridge microscopy, materials science, microbiology, and computational analytics to develop effective interventions against these recalcitrant microbial communities.

In the ongoing battle against antimicrobial resistance (AMR), bacterial biofilms represent a formidable challenge, contributing significantly to persistent infections and treatment failures. A biofilm is a complex, surface-associated microbial community encased in a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) [16]. This structured consortium is not merely a collection of cells but a dynamic, organized ecosystem that demonstrates a distinct lifecycle. Comprehending this lifecycle—from initial attachment to final dispersion—is paramount for developing effective interventions against biofilm-associated infections, particularly those involving multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) [16]. This review delineates the biofilm lifecycle within the critical context of matrix composition and its role in impeding antibiotic penetration, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Biofilm Lifecycle: A Stage-by-Stage Analysis

The formation of a biofilm is a multifaceted process involving physical, chemical, and biological elements. It typically unfolds in several sequential, yet overlapping, stages [16] [2].

Initial Reversible Attachment

The lifecycle commences with the adhesion of free-living (planktonic) microorganisms to a conditioned surface [16] [2]. This initial attachment is mediated by weak, reversible interactions such as van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions [16]. The nature of the surface plays a critical role; for instance, rough surfaces tend to promote better microbial adhesion compared to smooth ones [16]. Bacteria may employ structures like pili for a more passive attachment or engage active mechanisms requiring prolonged surface contact [16]. Notably, traditional models of single-cell attachment are now complemented by understanding that seeding often begins with clumps of cells or aggregates that detach from existing biofilms, which are inherently more resilient to stress [2].

Irreversible Attachment and Microcolony Formation

Following initial attachment, the connection to the surface becomes permanent. The reversibly attached cells utilize environmental nutrients to grow, divide, and begin secreting the sticky, three-dimensional EPS matrix, primarily composed of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (eDNA) [16] [2]. This matrix facilitates irreversible attachment and anchors the cells together [16]. A key molecular regulator in this transition is the secondary messenger cyclic diguanylate monophosphate (c-di-GMP). High intracellular levels of c-di-GMP, controlled by the balance of diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and phosphodiesterases (PDEs), promote a sessile lifestyle by reducing motility and encouraging matrix production [2]. This stage leads to the formation of distinct microcolonies [16] [2].

Maturation

During maturation, microcolonies expand and develop into a mature biofilm with a complex, heterogeneous architecture [16] [2]. The EPS matrix can constitute over 90% of the biofilm's biomass, creating a structured environment with gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and pH [2]. These gradients generate diverse microniches, leading to metabolic heterogeneity among the embedded cells [2]. The biofilm community engages in sophisticated coordination through quorum sensing (QS), a cell-to-cell communication system where bacteria detect population density via signaling molecules like acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs) in Gram-negative bacteria [2] [11]. QS regulates collective behaviors, including virulence expression and further matrix synthesis [11]. The resulting structure, often characterized by mushroom-shaped towers or other architectures depending on the species and environment, is highly resistant to external threats [2].

Dispersion

The final stage of the lifecycle is dispersion, where cells actively detach from the biofilm to colonize new substrates [2]. This complex process can be initiated in response to environmental cues such as nutrient starvation or the presence of antimicrobials [2]. Mechanisms of dispersal include:

- Seeding (Central Hollowing): An active process where large quantities of cells or micro-colonies are promptly released, forming hollow cavities within the biofilm [2].

- Erosion and Sloughing: Passive processes where smaller fragments erode over time or substantial fragments detach abruptly due to external forces like shear flow [2]. Dispersal is a critical event for bacterial survival and propagation, completing the lifecycle and allowing it to begin anew in a different location.

Table 1: Key Stages of the Biofilm Lifecycle and Their Characteristics

| Lifecycle Stage | Key Processes | Physiological Regulators | Structural Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Attachment | Reversible adhesion via weak forces (van der Waals, electrostatic) | Surface properties (roughness, hydrophobicity) | Formation of a preconditioned layer; presence of pioneer cells or aggregates [16] [2] |

| Irreversible Attachment | EPS secretion, transition from planktonic to sessile growth | Increased intracellular c-di-GMP levels [2] | Stable anchorage to surface; formation of a protective matrix [16] |

| Maturation | Microcolony development, 3D architectural formation, metabolic heterogeneity | Quorum Sensing (e.g., AHLs, AI-2) [11] | Complex, heterogeneous structures (e.g., mushroom-shaped); established nutrient/gradient niches [2] |

| Dispersion | Active (seeding) or passive (erosion, sloughing) detachment | Environmental stress (e.g., nutrient depletion) [2] | Release of planktonic cells or aggregates for new colonization; hollowing of biofilm structure [2] |

Quantitative Analysis of Biofilm Composition and Dynamics

Understanding the temporal evolution of biofilm matrix components is crucial for targeting its structural integrity. Advanced techniques like solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) enable non-destructive, quantitative tracking of compositional changes.

A time-resolved ssNMR study of Bacillus subtilis biofilms over a 5-day period revealed distinct phases of development and degradation [17]. The mature biofilm, established within 48 hours, underwent significant degradation in the subsequent 72 hours. The steepest decline in proteins preceded that of exopolysaccharides, likely reflecting their distinct spatial distribution and functional roles within the matrix [17]. Furthermore, different sugar units within the exopolysaccharides displayed clustered temporal patterns, suggesting the presence of distinct polysaccharide types with varying stability or turnover rates [17]. A sharp rise in aliphatic carbon signals on day 4 was also noted, probably corresponding to a surge in biosurfactant production, potentially linked to the dispersal phase [17].

Table 2: Time-Resolved Compositional Changes in Bacillus subtilis Biofilm Matrix (ssNMR Data) [17]

| Time Point | Key Compositional and Dynamic Events | Interpretation and Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1-2 | Establishment of mature biofilm structure; distinct dynamic regimes (90% mobile, 10% rigid phases) | Initial matrix assembly creates a heterogeneous environment with components of varying molecular mobility [17] |

| Day 3-5 | Initiation of degradation phase; steepest decline of proteins precedes exopolysaccharide loss | Proteins may be more accessible to degradation or located in vulnerable regions of the matrix, impacting structural stability [17] |

| Throughout | Clustered temporal patterns of exopolysaccharide sugar units | Suggests presence of structurally and functionally distinct polysaccharide types within the EPS [17] |

| Day 4 | Sharp increase in aliphatic carbon signals | Likely reflects increased production of biosurfactants, molecules often associated with biofilm dispersal [17] |

Mechanisms of Biofilm-Associated Antibiotic Resistance

The biofilm matrix and the altered physiology of its resident cells create multiple, synergistic barriers to antibiotic efficacy, contributing to profound tolerance and resistance [16] [2].

- Physical Barrier and Charge-Based Sequestration: The dense EPS matrix acts as a diffusion barrier, physically impeding the penetration of antimicrobial agents [2]. Some antibiotics are rendered ineffective by forming complexes with matrix components or being broken down by enzymes within the matrix [2]. Positively charged antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides, can bind to negatively charged biopolymers like eDNA in the matrix, significantly slowing their penetration and reducing the effective concentration that reaches the cells [2].

- Metabolic Heterogeneity and Persister Cells: The spatial heterogeneity of biofilms results in gradients of nutrient availability, oxygen, and waste products [2]. This creates zones of slow bacterial growth or metabolic dormancy. Since many conventional antibiotics target active cellular processes (e.g., cell wall synthesis, protein production), these dormant or slow-growing cells are inherently tolerant [2] [18]. A subpopulation of these, known as persister cells, can survive high doses of antibiotics without genetic mutation and repopulate the biofilm once treatment ceases [18].

- Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): The dense, structured environment of a biofilm, facilitated by components like eDNA, provides an ideal platform for the efficient exchange of genetic material between cells through conjugation, transformation, and transduction [18]. This makes biofilms hotspots for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes, accelerating the development of multidrug-resistant strains [18].

Advanced Methodologies for Biofilm Research

Image Cytometry with BiofilmQ

For the quantification and visualization of biofilm-internal properties in three-dimensional space and time, BiofilmQ serves as a comprehensive image cytometry software tool [12]. It is designed for automated, high-throughput analysis of 3D fluorescence images from a wide variety of microbial communities [12].

Protocol: 3D Image Analysis Using BiofilmQ

- Image Acquisition & Segmentation: Acquire 3D fluorescence images (e.g., via CLSM). BiofilmQ requires identification of the biofilm's biovolume. This can be achieved using:

- Automatic segmentation (e.g., Otsu, Ridler-Calvard algorithms).

- Semi-manual thresholding with visual feedback.

- Import of pre-segmented images from other tools (e.g., U-Net convolutional neural networks) [12].

- Image Cytometry: If single-cell segmentation is not feasible, BiofilmQ dissects the biofilm biovolume into a cubical grid. Each cube is treated as a pseudo-object for analysis [12].

- Parameter Quantification: For each cube (or custom-segmented object), BiofilmQ calculates numerous cytometric properties (e.g., fluorescence intensity, distance to biofilm surface, local biomass density). It also computes hundreds of global parameters for the whole biofilm (e.g., volume, mean thickness, surface area, roughness) [12].

- Data Analysis and Gating: Analogous to flow cytometry, apply gates/filters to the cube-based data to analyze specific subpopulations (e.g., cells in the core vs. shell of the biofilm) [12] [19].

- Data Visualization: Use the visualization tab to create publication-quality figures, including histograms, 2D/4D scatter plots, kymographs, and 3D heatmaps [19].

Quantitative Measurement of Biofilm Activity

Planar O₂ Optodes provide a non-destructive method for quantifying biological activity and spatial heterogeneity in biofilms. This technique is particularly useful in studying biofouling in membrane filtration systems but is applicable to other substrates [20].

Protocol: Measuring O₂ Consumption Rates with Planar Optodes

- Setup Integration: Integrate a planar O₂ optode—a transparent foil coated with an O₂-sensitive luminescent dye—into the experimental system (e.g., a membrane fouling simulator or flow cell) [20].

- Image Acquisition: Use a luminescence lifetime imaging system to capture high-resolution, two-dimensional maps of O₂ distribution across the optode surface over time [20].

- Rate Calculation: Quantify the O₂ consumption rate by monitoring the temporal decline of O₂ concentration in the system after briefly stopping the flow, or by analyzing the steady-state O₂ gradients that form within the biofilm [20].

- Data Correlation: Correlate the spatial maps of O₂ concentration and consumption rates with concurrent measurements, such as pressure drop increases and flow distribution images, to link biofilm activity directly to its functional impact [20].

Experimental Design for CLSM Time-Lapse Imaging

When designing CLSM time-lapse experiments to study early biofilm formation or antimicrobial treatment effects, careful consideration of variability is key [21].

Protocol: Optimizing CLSM Experimental Design

- Pilot Study: Conduct initial pilot experiments to quantify the inherent variability in the system. Key factors include bacterial growth phase (lag vs. exponential) and the efficacy of the antimicrobial treatment being studied [21].

- Determine Variance Components: Analyze pilot data to determine the variability arising from:

- Independent experiments (biological replicates).

- Different fields of view (FOV) within one experiment.

- Temporal resolution (frame capture rate) [21].

- Power Analysis: Use the variance components from the pilot study in an experimental design assessment tool (e.g., a custom spreadsheet) to predict the statistical power of different experimental designs [21].

- Final Design: Choose a design that balances statistical confidence with practical constraints, specifying:

- The number of independent experiments.

- The number of FOVs per experiment.

- The optimal frame capture rate per hour to avoid phototoxicity and data overload while capturing critical dynamics [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biofilm Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function/Application | Key Characteristics and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| BiofilmQ Software [12] | 3D image cytometry, analysis, and visualization of biofilm internal properties and global parameters. | Handles images from micro- to macro-colonies; requires prior biofilm biovolume segmentation; includes batch processing and data gating. |

| Planar O₂ Optodes [20] | Non-destructive, spatially resolved measurement of O₂ concentration and consumption rates as a proxy for metabolic activity. | Provides both structural and quantitative activity data; can be correlated with other imaging techniques like MRI. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM) [21] | Non-invasive, real-time 3D imaging of hydrated, intact biofilms. | Enables visualization of spatial organization, gene expression localization (with reporters), and biocide action over time. |

| Solid-State NMR (ssNMR) [17] | Non-destructive, quantitative in-situ characterization of biofilm composition and molecular dynamics. | Provides detailed information on abundance and mobility of specific matrix components (e.g., proteins, polysaccharides) over time. |

| 13C-labeled Glycerol [17] | Isotopic labeling of carbon sources for tracking metabolic incorporation into biofilm components via ssNMR. | Allows for precise quantitative analysis of the temporal production and degradation of specific matrix molecules. |

| Membrane Fouling Simulator (MFS) [20] | Laboratory-scale system for controlled studies of biofilm formation (biofouling) under conditions mimicking industrial settings. | Allows for simultaneous monitoring of operational parameters (e.g., pressure drop) and biofilm activity (e.g., via optodes). |

The dynamic biofilm lifecycle, from attachment to dispersion, is a highly regulated process that culminates in a resilient, structured community. This resilience is fundamentally rooted in the biofilm's EPS matrix, which acts as a primary barrier to antibiotic penetration and fosters an environment conducive to physiological tolerance and genetic resistance. Tackling the challenge of biofilm-associated infections, particularly in the context of multidrug resistance, requires a multifaceted approach. Promising strategies include enzymatic matrix disruption (e.g., Dispersin B, DNase I), quorum sensing inhibition, phage-antibiotic synergistic therapies, and nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery [18]. Overcoming this challenge demands a deep understanding of biofilm biology, supported by advanced quantitative techniques like those detailed in this review, to inform the development of next-generation anti-biofilm therapeutics.

The escalating global health crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is profoundly driven by the ability of bacterial pathogens to form biofilms. These complex, matrix-encased communities are a hallmark of chronic and recurrent infections, providing resident bacteria with formidable protection against antibiotics and host immune defenses [2] [16]. The ESKAPE pathogens—an acronym for Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species—exemplify this challenge, as they represent the leading causes of nosocomial infections that effectively "escape" the action of conventional antimicrobial therapies [22] [23]. The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix is the central architectural component of biofilms, acting as a physical and functional barrier that limits antibiotic penetration, inactivates antimicrobial molecules, and fosters a heterogeneous microbial physiology conducive to tolerance [2] [24]. Among the ESKAPE pathogens, P. aeruginosa has emerged as a paradigmatic model organism for biofilm research due to its extensively studied and versatile matrix machinery, sophisticated regulatory networks, and its role as a primary agent in chronic lung infections, particularly in cystic fibrosis patients, and in wounds and medical device-related infections [24] [23]. This whitepaper delineates the key matrix producers within the ESKAPE cohort, utilizes P. aeruginosa as a model to elucidate the fundamental principles of biofilm-mediated resistance, and synthesizes contemporary experimental methodologies and emerging therapeutic strategies aimed at mitigating the biofilm barrier to antibiotic penetration.

Comparative Analysis of Biofilm Formation and Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens

The ESKAPE pathogens demonstrate significant variability in their propensity to form biofilms, the composition of their extracellular matrices, and their associated antimicrobial resistance profiles. A recent comparative analysis of clinical isolates provides critical quantitative insights into these differences, underscoring the unique threat posed by each member [22].

Table 1: Comparative Biofilm Formation and Key Resistance Traits in ESKAPE Pathogens

| Pathogen | Gram Stain | Prevalence of Biofilm Formers | Strong Biofilm Producers | Key Resistance Traits | Notable Resistance Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. faecium | Positive | High | Moderate | High-level MDR (90%), Vancomycin Resistance | vanB |

| S. aureus | Positive | High | Moderate | Methicillin Resistance (MRSA - 46.7%) | mecA |

| K. pneumoniae | Negative | High | High | Carbapenem Resistance (45.71%), Colistin Resistance (42.86%), ESBL | NDM, OXA-48-like |

| A. baumannii | Negative | High | High | Carbapenem Resistance (74.29%), MDR | OXA-type carbapenemases |

| P. aeruginosa | Negative | High | Moderate | Carbapenem Resistance (Lower than A. baumannii & K. pneumoniae), Intrinsic MDR | AmpC, Metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) |

The data reveals that biofilm formation is a ubiquitous capability among ESKAPE pathogens, with a significant majority (88.5%) of clinical isolates forming biofilms, and 15.8% characterized as strong producers [22]. A particularly noteworthy finding is the correlation between biofilm formation and resistance to critical antibiotic classes, including carbapenems, cephalosporins, and piperacillin/tazobactam, suggesting a synergistic role of biofilms in disseminating and entrenching resistance [22]. The high rates of multi-drug resistance (MDR), especially in E. faecium (90%) and A. baumannii, coupled with significant carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative members, highlight the therapeutic dead ends often encountered when treating biofilm-associated infections [22].

3Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A Model for Biofilm Matrix Complexity and Antibiotic Recalcitrance

P. aeruginosa serves as an archetype for understanding biofilm biology due to its genetic tractability and the well-defined composition of its matrix, which primarily consists of the exopolysaccharides Psl, Pel, and alginate, extracellular DNA (eDNA), and proteins [25] [24] [26]. The matrix is not a mere physical barrier; it is a dynamic functional compartment that actively contributes to tolerance and resistance through multiple mechanisms.

Key Exopolysaccharides and Matrix Proteins

- Psl (Polysaccharide Synthesis Locus): A mannose-, rhamnose-, and glucose-rich polysaccharide that provides structural scaffolding for the biofilm. Psl plays a critical role in cell-surface and cell-cell adhesion during initial biofilm development [26]. Recent research has identified that the lectin LecB binds specifically to the branched mannose residues of Psl, stabilizing the biofilm matrix and enhancing cell and EPS retention [26].

- Pel (Polysaccharide Encapsulation Locus): A positively charged, N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc)- and N-acetyl galactosamine (GalNAc)-rich polysaccharide that interacts with eDNA, contributing to matrix integrity and resistance to aminoglycosides [2] [26].

- Alginate: A hallmark of mucoid P. aeruginosa variants common in chronic cystic fibrosis lung infections. Alginate forms a viscous capsule that inhibits phagocytosis and scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS), providing protection against both antibiotics and the host immune response [25] [24].

- LecB: This soluble lectin, while involved in host attachment, is also a bona fide matrix component. Its interaction with Psl represents a protein-carbohydrate interaction that is crucial for maintaining the structural stability of the biofilm [26].

- Extracellular DNA (eDNA): A universal matrix component that contributes to biofilm integrity and chelates cationic antibiotics like aminoglycosides and colistin, significantly reducing their effective concentration within the biofilm [2] [24].

Mechanisms of Antibiotic Tolerance and Resistance in Biofilms

The biofilm mode of growth confers tolerance through a multifaceted interplay of physical, physiological, and adaptive mechanisms, with P. aeruginosa exhibiting a particularly broad arsenal [24].

Diagram: Mechanisms of Biofilm-Mediated Antibiotic Resistance in P. aeruginosa

The diagram above summarizes the core mechanisms, which include:

- Physical Restriction and Inactivation: The EPS matrix acts as a diffusion barrier, slowing antibiotic penetration. Furthermore, ionic interactions between matrix components (e.g., anionic eDNA and alginate) and cationic antibiotics (e.g., tobramycin, colistin) lead to sequestration and neutralization [2] [24]. Enzymes like AmpC β-lactamase can be concentrated in the matrix, inactivating β-lactam antibiotics before they reach their cellular targets [24].

- Physiological Heterogeneity: Gradients of nutrients and oxygen within the biofilm create zones of metabolically inactive or slow-growing bacteria. Since many antibiotics target active cellular processes, these dormant cells exhibit profound tolerance and can act as "persisters," capable of re-populating the biofilm after antibiotic treatment ceases [2] [24].

- Biofilm-Specific Adaptive Responses: The biofilm lifestyle triggers the expression of specific genes. The transcriptional regulator BrlR upregulates efflux pumps (e.g., MexAB-OprM, MexEF-OprN), directly contributing to multidrug resistance [24]. The gene ndvB, involved in the synthesis of periplasmic glucans, is also upregulated in biofilms and can sequester antibiotics like aminoglycosides, preventing them from reaching their targets [24].

Experimental Methods for Analyzing Biofilm Matrix and Antibiotic Penetration

A robust methodological framework is essential for dissecting biofilm matrix composition and evaluating the efficacy of antimicrobial agents. The following section details key protocols cited in contemporary literature.

Microtiter Plate Biofilm Formation Assay

This standard method quantifies total biofilm biomass and is ideal for high-throughput screening [22].

- Procedure:

- Inoculation: Dilute an overnight bacterial culture to ~1×10^6 CFU/mL in fresh, appropriate medium. Dispense 200 µL per well into a sterile 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plate. Include negative control wells with medium only.

- Incubation: Incubate the plate statically for 24-48 hours at the optimal growth temperature for the organism (e.g., 37°C for pathogens).

- Washing: Carefully remove the planktonic culture by inverting and flicking the plate. Gently wash the adhered biofilm twice with 200-300 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove non-adherent cells.

- Fixation and Staining: Fix the biofilm with 200 µL of 99% methanol for 15 minutes. Empty the plate and allow it to air dry. Subsequently, stain the biofilm with 200 µL of 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet solution for 5-15 minutes.

- Destaining and Quantification: Rinse the plate thoroughly under running tap water to remove excess stain. After air drying, add 200 µL of 33% glacial acetic acid or 95% ethanol to destain and solubilize the crystal violet. Transfer 125 µL of the solubilized dye to a new microtiter plate.

- Measurement: Measure the optical density (OD) at 570-600 nm using a microplate reader. The OD is proportional to the biofilm biomass attached to the well surface.

Modified Carbapenem Inactivation Method (mCIM and eCIM) for Carbapenemase Detection

This phenotypic assay is critical for identifying carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative isolates, a key resistance trait in ESKAPE pathogens like K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii [22].

- Principle: The test organism is incubated with a meropenem disk. If the organism produces a carbapenemase, the enzyme will inactivate the meropenem. This is detected by a reduction in the zone of inhibition of an indicator strain.

- mCIM Procedure:

- Preparation: Create a 1-µL loop of the test organism from an overnight agar plate and emulsify it thoroughly in 2 mL of tryptic soy broth (TSB).

- Incubation with Antibiotic: Add a 10-µg meropenem disk to the broth. Incubate the suspension at 35°C ± 2°C for 4 hours ± 15 minutes.

- Testing Inactivation: After incubation, remove the meropenem disk and place it on a Mueller-Hinton agar plate that has been inoculated with a 0.5 McFarland standard of a susceptible E. coli indicator strain (e.g., ATCC 25922).

- Interpretation: Incubate the plate for 18-24 hours at 35°C. A zone diameter of ≤15 mm (or 6-15 mm with a clump of colonies within the zone) indicates a positive result for carbapenemase production. A zone diameter of ≥19 mm indicates a negative result.

- eCIM Procedure: The eCIM test is performed in parallel. EDTA, an inhibitor of Metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs), is added to a separate broth suspension of the test organism. An increase in the zone diameter of ≥5 mm for the eCIM test compared to the mCIM test confirms the production of an MBL [22].

PCR for Detection of Biofilm-Associated and Resistance Genes

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a fundamental molecular technique for identifying the genetic determinants of biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance [22].

- Protocol for Screening Biofilm-Forming Genes:

- DNA Extraction: Purify genomic DNA from bacterial cultures using a commercial kit or standard enzymatic (lysozyme) and chemical (SDS) lysis followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation.

- PCR Reaction Setup: Prepare a 25-µL reaction mixture containing:

- 1X PCR buffer (with MgCl₂)

- 200 µM of each dNTP

- 0.2-0.5 µM of each forward and reverse primer (designed for target genes, e.g., pslA, pelA, algD for P. aeruginosa; icaA and icaD for S. aureus)

- 1.0-1.5 U of thermostable DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase)

- 50-100 ng of template DNA

- Thermal Cycling: Amplify the target DNA in a thermal cycler using a standard program:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Amplification (30-35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: 55-65°C (primer-specific) for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of amplicon length.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes.

- Analysis: Analyze the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5-2.0% gel), stain with ethidium bromide or a safer alternative, and visualize under UV light to confirm the presence of an amplicon of the expected size.

Emerging Strategies to Overcome Biofilm-Mediated Resistance

The profound resistance of biofilms to conventional antibiotics has necessitated the development of novel therapeutic approaches that target the biofilm structure itself.

Diagram: Emerging Anti-Biofilm Therapeutic Strategies

A highly promising strategy involves the disruption of the biofilm matrix to release resident bacteria, which subsequently enter a transient state of heightened antibiotic susceptibility. A groundbreaking approach utilizes antibodies targeting DNABII proteins (HU and IHF), which serve as structural linchpins in the biofilm matrix by binding to and stabilizing eDNA [27]. Incubation of biofilms with these antibodies causes a rapid collapse of the matrix structure, releasing "newly released" (NRel) bacteria. These NRel bacteria exhibit significantly increased sensitivity to killing by traditional antibiotics—even at sub-MIC concentrations—that were ineffective against the biofilm-embedded population [27]. This combinatorial strategy of a biofilm-disrupting agent (e.g., a humanized monoclonal antibody like HuTipMab) co-delivered with a standard antibiotic represents a paradigm shift in treating chronic, biofilm-mediated infections [27].

Other emerging strategies include the use of glycoside hydrolases to degrade polysaccharide matrix components, quorum sensing inhibitors to disrupt bacterial communication, and lectin inhibitors (e.g., glycomimetics that block LecB-Psl interactions) to destabilize the biofilm architecture [26] [16] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Biofilm and Antibiotic Resistance Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Violet | A basic dye that binds to negatively charged surface molecules and polysaccharides in the biofilm matrix. | Staining and semi-quantification of total biofilm biomass in microtiter plate assays [22]. |

| Meropenem Disks | A carbapenem antibiotic. Serves as the substrate for detecting carbapenemase enzyme activity. | Used as the key reagent in the mCIM and eCIM tests for phenotypic detection of carbapenemase production [22]. |

| Anti-DNABII Antibodies | Monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies that target the DNABII proteins (HU/IHF). Function as a biofilm-disrupting agent. | Experimental disruption of biofilms from diverse bacterial genera to induce NRel bacteria for subsequent antibiotic killing studies [27]. |

| PCR Primers (e.g., for psl, pel, mecA, vanB) | Short, single-stranded DNA fragments designed to flank a specific gene sequence. Enable targeted amplification for genetic screening. | Detection of biofilm-forming genes (e.g., pslA) or antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., mecA for MRSA) in bacterial isolates via conventional or quantitative PCR [22]. |

| LecB-FITC (Fluorescein Isothiocyanate) | Fluorescently labeled lectin that binds specifically to mannose and fucose residues. | Visualization and quantification of LecB binding to its polysaccharide ligand Psl in the biofilm matrix using fluorophore-linked lectin assays (FLLA) [26]. |

| Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) | A rich, general-purpose nutrient medium that supports the growth of a wide variety of fastidious and non-fastidious organisms. | Standard liquid medium for growing planktonic cultures and for promoting robust biofilm formation in in vitro assays [22]. |

The ESKAPE pathogens, with Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a preeminent model, demonstrate that the biofilm matrix is a central organizer of antimicrobial recalcitrance. The synergistic interplay of physical barrier function, physiological heterogeneity, and biofilm-specific adaptive responses creates a formidable defense system that renders traditional monotherapies largely ineffective. The quantitative data and mechanistic insights consolidated in this whitepaper underscore the critical need to shift the therapeutic paradigm from simply killing bacteria to disrupting their communal architecture. The experimental methodologies detailed herein provide a foundational toolkit for ongoing research, while the emergence of innovative strategies, particularly matrix-disrupting agents like anti-DNABII antibodies used in combination with antibiotics, offers a promising path forward. Future research must continue to decode the intricate biology of biofilm matrices, validate these novel combinatorial approaches in clinical settings, and accelerate the development of next-generation therapeutics capable of penetrating and dismantling these bastions of bacterial resistance.

The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix of biofilms has traditionally been viewed as a physical barrier that restricts antibiotic penetration. However, emerging research reveals that matrix components serve sophisticated functional roles that extend far beyond structural support. The biofilm matrix represents a dynamic, functionally active compartment that actively contributes to antimicrobial resistance through molecular interactions, enzymatic degradation, and physiological regulation of embedded microbial communities [16] [2]. This paradigm shift in understanding matrix functionality is critical for developing effective strategies against biofilm-associated infections, which account for approximately 65% of all microbial infections and demonstrate up to 1000-fold greater antibiotic tolerance compared to their planktonic counterparts [28].

The matrix is composed of a complex mixture of polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA (eDNA), lipids, and other biopolymers that vary depending on microbial species and environmental conditions [2]. Rather than serving merely as a passive scaffold, these components form a chemically active interface that modulates antibiotic penetration, inactivates antimicrobial agents, facilitates intercellular communication, and promotes genetic exchange. This review synthesizes current understanding of the functional roles of matrix components, with particular emphasis on mechanisms that contribute to antibiotic penetration resistance, to inform the development of next-generation anti-biofilm therapeutics.

Multifunctional Roles of Major Matrix Components

Extracellular DNA (eDNA): A Polyfunctional Virulence Factor

eDNA serves critical functions beyond structural integrity, including cation chelation, antibiotic binding, and facilitation of horizontal gene transfer. The phosphodiester backbone of eDNA confers a net negative charge that enables electrostatic interactions with cationic antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and aminoglycoside antibiotics [2]. Studies demonstrate that eDNA can bind tobramycin, significantly reducing its effective concentration within deeper biofilm regions [2]. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms, eDNA works synergistically with host-derived DNA in cystic fibrosis lungs to create a physical shield that protects bacterial communities from both antibiotics and immune cells [2].

Table 1: Functional Roles of eDNA in Biofilm Matrix

| Function | Mechanism | Impact on Resistance | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Binding | Electrostatic interactions with cationic antibiotics | Reduced antibiotic penetration & efficacy | Fluorescence quenching assays show tobramycin-eDNA complex formation [2] |

| Cation Chelation | Binding of Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ ions | Activation of cationic antimicrobial peptide resistance pathways | Induces pmr operon in P. aeruginosa, increasing lipid A modification [2] |

| Genetic Material | Horizontal gene transfer substrate | Dissemination of resistance genes | Transformation efficiency increases 10-1000x in biofilms vs. planktonic cells [18] |

| Neutrophil Protection | Physical barrier formation | Protection from neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) | NET-associated host DNA complements bacterial eDNA shielding [2] |

Exopolysaccharides: Architecturally Active Polymers

Exopolysaccharides constitute the volumetric majority of most biofilm matrices and serve multiple functional roles beyond scaffolding. These polymers create a highly hydrated environment that restricts antibiotic diffusion through molecular sieving and binding interactions. Specifically, the negatively charged groups on alginate (in P. aeruginosa) and poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) in staphylococcal biofilms can bind positively charged aminoglycosides, effectively sequestering them before they reach cellular targets [16] [28]. The viscous polysaccharide network also establishes chemical gradients that generate heterogeneous metabolic activity, contributing to persister cell formation and phenotypic tolerance [18].

Matrix Proteins: Enzymatic Defense Systems

Biofilm matrices contain diverse protein components that actively contribute to resistance mechanisms. Enzymatic resistance factors such as β-lactamases can be retained within the matrix, creating a front-line defense system that inactivates antibiotics before they penetrate to cellular targets [29]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms, for instance, release β-lactamases into the matrix that hydrolyze penicillins and cephalosporins, with catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) reaching up to 10⁶ M⁻¹s⁻¹ for enzymes like TEM-52 and CTX-M-15 [29]. Other matrix proteins function as structural elements that bind eDNA and polysaccharides, while some actively modify the matrix environment to maintain conditions favorable for bacterial survival.

Advanced Experimental Approaches for Investigating Matrix Functionality

Methodologies for Assessing Antibiotic-Matrix Interactions

Understanding the functional roles of matrix components requires sophisticated experimental approaches that quantify interactions between antibiotics and specific matrix constituents:

Fluorescent Probe Binding Assays: This technique utilizes fluorescence-labeled antibiotics or matrix components to quantify binding interactions. When tobramycin conjugated with FITC binds to eDNA, fluorescence quenching occurs, allowing calculation of binding constants through Stern-Volmer analysis [2]. The protocol involves: (1) preparing biofilm matrix extracts or purified matrix components; (2) adding serial dilutions of fluorescently-labeled antibiotics; (3) measuring fluorescence intensity changes using a plate reader; (4) calculating binding constants from quenching curves.

Diffusion Chamber Systems: These systems measure antibiotic penetration rates through intact biofilms using a two-compartment model separated by a biofilm-grown membrane. The methodology includes: (1) growing biofilms on permeable membranes; (2) placing membrane between antibiotic-containing and antibiotic-free chambers; (3) sampling from the antibiotic-free chamber at timed intervals; (4) quantifying antibiotic concentration via HPLC or bioassay; (5) calculating diffusion coefficients using Fick's law [28].

Enzymatic Activity Assays in Biofilm Supernatants: These assays detect and quantify antibiotic-degrading enzymes within the matrix environment. The protocol involves: (1) collecting biofilm supernatants and concentrated matrix extracts; (2) incubating with specific antibiotic substrates; (3) measuring substrate degradation via spectrophotometry or HPLC; (4) determining enzyme kinetics (Km, Vmax) under conditions mimicking the biofilm microenvironment [29].

Genetic Approaches for Elucidating Matrix Function

Genetic techniques enable researchers to dissect the contribution of specific matrix components to antibiotic resistance:

Targeted Gene Knockout with CRISPR-Cas9: This approach creates isogenic mutants lacking specific matrix components to assess their functional contributions. The methodology includes: (1) designing gRNAs targeting genes of interest (e.g., pelA, pslG, algD for polysaccharide synthesis); (2) preparing CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes; (3) delivering complexes via conjugation or electroporation; (4) verifying gene deletion via PCR and sequencing; (5) comparing antibiotic susceptibility between mutant and wild-type biofilms using minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC) assays [30].

Gene Expression Profiling in Biofilm Subregions: Spatial mapping of gene expression within biofilms reveals compartmentalized functional specialization. The protocol involves: (1) growing biofilms under controlled conditions; (2) cryosectioning or laser capture microdissection to isolate specific biofilm regions; (3) RNA extraction and reverse transcription; (4) quantifying expression of matrix-related genes via qRT-PCR or RNA-seq; (5) correlating expression patterns with functional properties of different biofilm zones [2].

Diagram 1: Multifunctional roles of eDNA in antibiotic resistance. The diagram illustrates how extracellular DNA (eDNA) contributes to resistance through charge-based antibiotic binding, horizontal gene transfer, cation chelation triggering adaptive responses, and quorum sensing activation in biofilms.

Quantitative Analysis of Matrix-Mediated Resistance Mechanisms

Table 2: Antibiotic Penetration Parameters Through Biofilm Matrix Components

| Antibiotic Class | Specific Antibiotic | Matrix Component | Reduction in Effective Concentration | Primary Mechanism | Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycosides | Tobramycin | eDNA | 60-80% | Charge-based sequestration | P. aeruginosa flow cell biofilm [2] |

| β-lactams | Ampicillin | β-lactamase in matrix | 90-95% | Enzymatic degradation | S. aureus biofilm model [29] |

| Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin | Alginate polysaccharide | 40-60% | Diffusion limitation | P. aeruginosa alginate beads [28] |

| Glycopeptides | Vancomycin | PNAG polysaccharide | 50-70% | Molecular sieving | S. epidermidis biofilm [16] |

| Antimicrobial Peptides | Colistin | eDNA & polysaccharides | 70-90% | Charge neutralization | A. baumannii wound biofilm [29] |

The data presented in Table 2 demonstrates that different matrix components selectively impact various antibiotic classes through distinct mechanisms. The reduction in effective concentration represents the percentage decrease in antibiotic concentration reaching cellular targets compared to the applied external concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Matrix Studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Biofilm Matrix Functions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Functional Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix-Degrading Enzymes | DNase I, Dispersin B, Alginate lyase | Selective degradation of specific matrix components (eDNA, PNAG, alginate) | Purity and activity validation; control for cellular toxicity [18] |

| Fluorescent Probes | FITC-labeled antibiotics, ConA, SYTO dyes | Visualization of antibiotic penetration and matrix architecture | Photostability; minimal perturbation of native structure [2] |

| Quorum Sensing Inhibitors | Synthetic AHL analogs, RNAIII-inhibiting peptides | Disruption of cell-to-cell communication and matrix regulation | Species-specificity; potential off-target effects [18] |

| Genomic Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, Transposon mutagenesis kits | Targeted manipulation of matrix biosynthesis genes | Delivery efficiency; pleiotropic effects assessment [30] |

| Nanoparticle Systems | Gold, silver, zinc oxide nanoparticles | Penetration enhancement; antimicrobial activity assessment | Size-controlled synthesis; biocompatibility testing [30] |

Signaling Pathways Regulating Matrix Production and Function

Matrix production is dynamically regulated through complex signaling networks that respond to environmental cues and population density. Understanding these regulatory pathways is essential for developing strategies to manipulate matrix composition and function.

Diagram 2: Regulatory pathways controlling biofilm matrix production. The diagram illustrates how quorum sensing (via autoinducers) and second messenger systems (like c-di-GMP) integrate population density and environmental stress signals to regulate matrix gene expression, creating a feedback loop that enhances antibiotic tolerance.

Quorum sensing (QS) systems represent the master regulatory circuitry controlling matrix production in response to population density. Gram-negative bacteria typically employ acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL) systems, while Gram-positive species use autoinducing peptide (AIP) signals [18]. These systems function through a cascade beginning with: (1) autoinducer synthesis and accumulation in the extracellular environment; (2) receptor binding at threshold concentrations; (3) activation of transcriptional regulators; (4) expression of matrix biosynthesis operons; and (5) increased production of polysaccharides, proteins, and eDNA release mechanisms.

The second messenger cyclic diguanylate monophosphate (c-di-GMP) serves as a central integrator of environmental signals for matrix regulation. High intracellular c-di-GMP levels promote matrix production and biofilm formation through allosteric activation of effector proteins that control the expression of matrix components [2]. The c-di-GMP network interfaces with QS systems to fine-tune matrix production in response to diverse environmental inputs, including nutrient availability, oxygen tension, and sub-inhibitory antibiotic concentrations.

The biofilm matrix represents a sophisticated functional compartment that actively contributes to antibiotic resistance through multiple mechanisms beyond mere physical obstruction. The integrated functions of eDNA, exopolysaccharides, and matrix proteins create a dynamic microenvironment that modulates antibiotic penetration, inactivates antimicrobial agents, facilitates genetic exchange, and regulates microbial physiology. Understanding these multifunctional roles is essential for developing effective strategies to combat biofilm-associated infections.

Future research directions should focus on spatial mapping of matrix component distribution and function within different biofilm regions, elucidating how matrix composition adapts in response to antimicrobial pressure, and developing targeted matrix-disrupting agents that can enhance conventional antibiotic efficacy. The integration of advanced techniques such as CRISPR-based editing with nanoparticle delivery systems holds particular promise for precisely manipulating matrix functions and overcoming treatment-resistant infections [30]. As our understanding of matrix functionality continues to evolve, so too will our ability to design innovative therapeutic approaches that address the multifactorial nature of biofilm-mediated resistance.

Tools of the Trade: Methodologies for Quantifying Penetration and Resistance

Biofilms are structured microbial communities encased in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix that confers significant protection against antimicrobial agents [16] [2]. This matrix, composed of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, creates a diffusion barrier that restricts antibiotic penetration and establishes heterogeneous microenvironments within the biofilm structure [18]. The inherent resistance of biofilms to conventional antibiotics represents a critical challenge in clinical settings, particularly for medical implant-associated infections and chronic conditions such as cystic fibrosis [2] [31].

Reaction-diffusion mathematical frameworks provide powerful tools for quantifying and predicting the complex spatiotemporal dynamics of antibiotic transport and efficacy within biofilms. These models bridge the gap between empirical observations and predictive understanding by explicitly coupling the physical process of antibiotic diffusion with biochemical reactions, including bacterial consumption, inactivation, and phenotypic adaptation [32] [31]. By simulating how antibiotics penetrate the biofilm matrix and interact with bacterial populations under varying conditions, these models offer invaluable insights for designing more effective treatment strategies against biofilm-associated infections.

Theoretical Foundations of Reaction-Diffusion in Biofilms

Core Principles and Governing Equations

Reaction-diffusion models conceptualize biofilms as porous structures where antimicrobial compounds move via molecular diffusion while simultaneously undergoing biochemical interactions. The fundamental governing equation for antibiotic transport within a biofilm can be expressed as:

∂C/∂t = ∇ · (D∇C) - R(C,S) - μC

Where C represents antibiotic concentration, D is the effective diffusion coefficient through the biofilm matrix, R(C,S) describes the reaction term accounting for antibiotic consumption or inactivation, and μ represents first-order degradation rate [32] [31]. The diffusion coefficient D is typically reduced within biofilms compared to aqueous environments due to the obstructive presence of EPS matrix components, with reported values ranging from 30% to 70% of their values in water [31].

The reaction term R(C,S) often follows Michaelis-Menten or Monod kinetics, reflecting concentration-dependent antibiotic uptake or inactivation by bacterial cells:

R(C,S) = Rmax · (C/(Ks + C)) · (S/(K_s + S))

Where Rmax represents the maximum consumption rate, Ks is the half-saturation constant, and S denotes nutrient concentration [32]. This formulation captures the nonlinear relationship between antibiotic concentration and bacterial consumption, which is particularly important for modeling concentration-dependent antibiotics like aminoglycosides.

Integration with Bacterial Population Dynamics

Advanced reaction-diffusion frameworks couple antibiotic transport with bacterial population dynamics, accounting for metabolic heterogeneity and phenotypic transitions within biofilms. A continuum approach typically models proliferative bacteria (Bp), persister cells (Bq), dead cells (B_d), and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) through a system of partial differential equations:

∂Bp/∂t = ∇ · (DB ∇Bp) + μmax · (S/(KS + S)) · (C/(KC + C)) · Bp - kswitch C · Bp + krevert · B_q

∂Bq/∂t = ∇ · (DB ∇Bq) + kswitch C · Bp - krevert · B_q

∂EPS/∂t = ∇ · (DEPS ∇EPS) + kEPS · μmax · (S/(KS + S)) · Bp - kdegrad · EPS

Where DB and DEPS represent diffusion coefficients for biomass and EPS respectively, μmax is the maximum growth rate, kswitch and krevert are phenotypic switching rates, and kEPS is the EPS production rate [31]. This formulation enables the model to capture the emergence of nutrient-limited persister cells that exhibit elevated antibiotic tolerance, a key mechanism of biofilm resilience.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Biofilm Reaction-Diffusion Models

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Units | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Diffusion Coefficient | D | 0.3-0.7 × D_water | cm²/s | Matrix restriction on molecular mobility |

| Maximum Growth Rate | μ_max | 0.1-0.8 | h⁻¹ | Bacterial division under ideal conditions |

| Half-Saturation Constant | K_S | 0.01-0.5 | mg/L | Nutrient affinity and utilization efficiency |

| Antibiotic Consumption Rate | R_max | 0.01-1.0 | mg/L·h | Metabolic uptake/inactivation capacity |

| Phenotypic Switching Rate | k_switch | 0.001-0.1 | h⁻¹ | Transition to dormant persister state |

| EPS Production Rate | k_EPS | 0.05-0.3 | - | Matrix synthesis per biomass growth |

Computational Implementation and Methodologies

Numerical Solution Approaches

Solving coupled reaction-diffusion equations for biofilm systems requires specialized numerical methods due to the moving boundary problem presented by biofilm growth and the stiffness introduced by multiple timescales. The finite-difference method (FDM) provides a straightforward approach for one-dimensional simulations, discretizing the spatial domain into uniform grids and approximating derivatives using difference quotients [32]. For more complex geometries, finite-element (FEM) or finite-volume methods (FVM) offer greater flexibility in handling irregular boundaries and heterogeneous material properties [31].

A typical implementation workflow includes:

- Spatial discretization of the computational domain