The Biofilm Matrix: Decoding the Diffusion Barrier and Its Role in Antibiotic Treatment Failure

Biofilms represent a fundamental mode of bacterial life that confers a remarkable level of protection against antimicrobial agents.

The Biofilm Matrix: Decoding the Diffusion Barrier and Its Role in Antibiotic Treatment Failure

Abstract

Biofilms represent a fundamental mode of bacterial life that confers a remarkable level of protection against antimicrobial agents. This review synthesizes current research on the biofilm matrix, focusing on its role as a critical diffusion barrier that contributes significantly to antibiotic treatment failure. We explore the structural and compositional complexity of the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), detailing how components like polysaccharides, extracellular DNA, and proteins physically impede antibiotic penetration and sequester drug molecules. For researchers and drug development professionals, this article provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanisms behind this intrinsic resistance, evaluates advanced models for studying antibiotic penetration, and surveys innovative therapeutic strategies designed to disrupt or bypass the matrix barrier. By integrating foundational knowledge with emerging methodologies and validation techniques, this review aims to guide the development of next-generation anti-biofilm therapies.

Deconstructing the Fortress: An In-Depth Look at Biofilm Matrix Composition and Structure

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the defining hallmarks of a mature biofilm that confer antibiotic resistance? A mature biofilm is not merely surface-attached bacteria; it is a structured, three-dimensional community. The key hallmark is the self-produced Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) matrix, a complex mixture of polysaccharides, proteins, extracellular DNA (eDNA), and lipids that acts as a primary diffusion barrier and physical shield [1] [2]. Other critical features include:

- Metabolic Heterogeneity: The formation of nutrient and oxygen gradients from the top to the bottom layers of the biofilm creates zones of slow-growing or dormant persister cells, which are highly tolerant to antibiotics [3] [4].

- Upregulated Defense Mechanisms: Biofilms exhibit increased activity of efflux pumps and other stress responses, further limiting the efficacy of antimicrobial agents [4].

Q2: My in vitro biofilm model does not recapitulate the antibiotic tolerance seen in clinical isolates. What could be wrong? This common issue often stems from using oversimplified biofilm models. Static models, like microtiter plate assays, are useful for high-throughput screening but often fail to produce the complex 3D architecture and physiological heterogeneity of in vivo biofilms [5]. To better mimic clinical scenarios:

- Switch to Dynamic Models: Implement flow cell systems or bioreactors (e.g., Constant Depth Film Fermenters) that provide constant nutrient flow and shear stress, promoting the development of mature, structured biofilms with enhanced tolerance [5].

- Consider Non-Surface-Attached Aggregates: Be aware that many chronic infections (e.g., in cystic fibrosis lungs) feature non-surface-associated bacterial aggregates that share the resistant phenotype of classic biofilms. Your model should account for this lifestyle [6] [7].

Q3: Beyond the EPS, what are the key molecular mechanisms driving biofilm-specific antibiotic resistance? The EPS barrier is just one component of a multi-layered resistance strategy. Key molecular mechanisms include:

- Nutrient Gradient-Induced Persistence: As mentioned, nutrient depletion in the biofilm core induces a dormant state in subpopulations of cells, making them insensitive to antibiotics that target active cellular processes [4].

- Altered Microenvironment: Factors like hypoxia and low pH within the biofilm can alter bacterial metabolism and directly reduce the activity of some antibiotics [4].

- Efflux Pump Activity: Specific efflux pumps are upregulated in biofilms, actively extruding antibiotics from the cells [4].

- Presence of Extracellular DNA (eDNA): eDNA within the matrix can directly bind to and inactivate certain classes of antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Biofilm Formation in Static Assays

- Problem: High variability in biofilm biomass between experimental replicates.

- Solution:

- Standardize Inoculum Preparation: Ensure planktonic cultures are grown to the same optical density and physiological state for every experiment.

- Surface Pre-conditioning: Coat your substrate (e.g., plastic, glass, hydroxyapatite) with a relevant conditioning film (e.g., saliva for oral models, serum for implant models) to standardize the initial attachment surface [5].

- Control Environmental Factors: Maintain strict consistency in incubation time, temperature, and humidity, as minor fluctuations can significantly impact attachment.

Challenge 2: Poor Penetration of Antimicrobials into the Biofilm

- Problem: An antibiotic is effective against planktonic cells but shows markedly reduced efficacy against the biofilm.

- Solution:

- Verify Penetration: Use fluorescently labeled antibiotics combined with confocal microscopy to visually confirm whether the drug is penetrating to the base of the biofilm [5].

- Combine with Matrix-Disrupting Agents: Co-administer the antibiotic with agents that target the EPS. For example, use DNase I to degrade eDNA or dispersin B to target polysaccharides, which can increase antimicrobial penetration [1] [7].

- Increase Contact Time/Concentration: Recognize that the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for biofilms can be 100-800 times greater than for planktonic cells. Perform dose-response curves to determine the true minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC) [7] [4].

Challenge 3: Difficulty in Distinguishing Between Live and Dead Cells in a Mature Biofilm

- Problem: Standard viability stains (e.g., SYTO9/PI) give ambiguous results in thick, dense biofilms.

- Solution:

- Use Metabolic Probes: Employ fluorescent probes that measure metabolic activity (e.g., CTC, resazurin) in combination with cell impermeant stains to better differentiate viable but non-culturable (VBNC) and dormant cells from dead cells.

- Employ Advanced Microscopy: Utilize time-lapse fluorescence microscopy or fluorescent probes that track cell fate in real-time to observe the heterogeneous physiological states within the biofilm [8] [5].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Dynamic Biofilm Cultivation in a Flow Cell System

Purpose: To grow mature, architecturally complex biofilms under controlled hydrodynamic conditions for diffusion and resistance studies [5].

Materials:

- Sterile flow cell chambers (e.g., Stovall or Ibidi style)

- Peristaltic pump and silicone tubing

- Media reservoir and waste bottle

- Syringe bubble trap

- Appropriate bacterial growth medium

- Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM)

Method:

- Assembly and Sterilization: Connect the entire flow system (reservoir → pump → bubble trap → flow cell → waste) and sterilize by autoclaving or flushing with 70% ethanol.

- Inoculation: Dilute an overnight bacterial culture to the desired OD. Stop the flow and inject the bacterial suspension into the flow cell channel. Allow the cells to attach statically for 1-2 hours.

- Initiate Flow: Start the peristaltic pump at a low, constant rate (e.g., 0.2 mL/min) to remove non-adherent cells and provide fresh medium.

- Maturation: Allow the biofilm to develop under flow for 24-72 hours, depending on the species and desired maturity.

- Analysis: Stop the flow and introduce fluorescent dyes (e.g., for live/dead staining, matrix components) or labeled antibiotics. Image the biofilm architecture in 3D using CLSM [5].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Antimicrobial Penetration via Confocal Microscopy

Purpose: To visualize and quantify the diffusion coefficient and penetration profile of an antimicrobial agent through the biofilm matrix [4].

Materials:

- Mature biofilm grown in a flow cell or on a coverslip

- Fluorescently labeled antibiotic (e.g., vancomycin-fluorophore conjugate)

- Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM)

- Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Imaris)

Method:

- Preparation: Grow a mature, thick biofilm using a dynamic or static method.

- Antibiotic Exposure: Introduce a solution of the fluorescently labeled antibiotic to the biofilm and start a timer.

- Time-Lapse Imaging: Immediately begin capturing Z-stack images of the biofilm at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds) at the same XY location.

- Data Analysis:

- Use software to measure the fluorescence intensity from the top to the bottom of the biofilm over time.

- Plot the fluorescence intensity versus depth for each time point.

- Calculate the effective diffusion coefficient (D_eff) for the antibiotic within the biofilm matrix by fitting the concentration profiles to Fick's laws of diffusion.

The Biofilm Lifecycle: A Visual Guide

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of biofilm development, integrating both classic and contemporary models.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The table below lists essential reagents and their specific functions in biofilm research related to matrix and diffusion barrier studies.

| Research Reagent | Primary Function in Biofilm Research |

|---|---|

| DNase I | Degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA) in the matrix; used to disrupt biofilm integrity and enhance antibiotic penetration [1]. |

| Dispersin B | An enzyme that hydrolyzes the polysaccharide poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG), a key matrix component in many staphylococcal and E. coli biofilms [7]. |

| Fluorescent Conjugates (e.g., WGA, ConA) | Lectins that bind to specific polysaccharides in the EPS, allowing for visualization and quantification of matrix components via microscopy [5]. |

| SYTO 9 / Propidium Iodide (PI) | A common live/dead viability stain. SYTO9 labels all cells, while PI penetrates only membrane-compromised cells [5]. |

| Resazurin (AlamarBlue) | A metabolic dye used to quantify the metabolic activity of cells within a biofilm, which can differ from sheer biomass [5]. |

| Crystal Violet | A simple stain that binds to biomass; used for basic, high-throughput quantification of total biofilm formation in microtiter plate assays [5]. |

| RNAIII-Inhibiting Peptide (RIP) | A quorum-sensing inhibitor that blocks biofilm formation in Staphylococci by interfering with cell-cell communication [1]. |

Quantitative Data on Biofilm Antibiotic Resistance

This table summarizes key quantitative data points that highlight the enhanced antibiotic resistance of biofilms compared to their planktonic counterparts.

| Parameter | Planktonic Cells | Biofilm Cells | Context / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Tolerance (MIC) | 1x (Baseline) | 100 - 800x higher [4] | MIC for biofilms can be hundreds of times greater than for planktonic cells of the same species. |

| Relative Resistance | 1x (Baseline) | Up to 1000x more resistant [1] [7] | Biofilms can be up to 1000 times more resistant to antibiotics than planktonic cells. |

| Percentage of Chronic Infections | - | ~80% [9] [3] | An estimated 65-80% of all chronic human microbial infections are associated with biofilms. |

| Matrix Composition (EPS) | - | >90% of dry mass [4] | The extracellular matrix constitutes the vast majority of a biofilm's dry mass. |

Core Signaling Pathways in Biofilm Development

The diagram below outlines the key signaling pathways that regulate the transition from planktonic growth to a mature biofilm, a critical process for understanding resistance development.

Core Components of the Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS)

Core Components of the EPS Matrix

The Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) matrix is a complex, dynamic mixture of biopolymers that constitutes the fundamental architectural element of microbial biofilms, forming a protective "house" for embedded cells [10]. This matrix is not a single substance but a sophisticated composite material that determines the physicochemical properties of the biofilm, including its porosity, density, charge, and mechanical stability [10]. The EPS accounts for 50% to 90% of the total organic matter in a biofilm, creating a three-dimensional, highly hydrated scaffold that encompasses microbial cells and mediates their interactions with the environment [11] [12].

The following table summarizes the primary chemical classes and their key characteristics found within the EPS:

| Component Class | Key Characteristics | Primary Functions in EPS Matrix |

|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharides | Heteropolymers or homopolymers; often polyanionic due to uronic acids or organic substituents like pyruvate or succinate [13] [14] [11]. | Provides structural integrity, mechanical stability, and cohesion; acts as a scaffold, facilitates adhesion, and retains water [14] [15]. |

| Proteins | Includes both structural proteins and extracellular enzymes (exoenzymes) [14] [12]. | Structural proteins stabilize architecture and provide cohesion; enzymes degrade matrix components and external nutrients [14] [15]. |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | Double-stranded DNA derived from genomic DNA, often organized in distinct patterns or filaments [14] [10]. | Provides structural support and stability; facilitates cell-to-cell connectivity and exchange of genetic information [14] [10]. |

| Lipids | Includes surfactants and other amphiphilic molecules [13]. | Contributes to surface activity, hydrophobicity, and interaction at interfaces [10]. |

| Other Components | Humic substances, minerals (e.g., CaCO₃) from biomineralization [11] [10]. | Minerals provide structural integrity; humic substances contribute to sorptive properties [11] [10]. |

The Role of EPS in Antibiotic Resistance: A Troubleshooting FAQ

This section addresses common research challenges and questions regarding the EPS matrix's role as a diffusion barrier, a key focus in antibiotic resistance research.

FAQ 1: Why do my minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays show such high resistance in biofilm-grown bacteria compared to planktonic cultures?

Issue: Standard MIC protocols developed for planktonic cells drastically underestimate the antibiotic concentration required to eradicate biofilms.

Explanation: The EPS matrix contributes to antibiotic resistance through multiple, synergistic mechanisms that are not active in planktonic cells.

- Physical Diffusion Barrier: The dense, anionic network of EPS components (e.g., polysaccharides, proteins) physically hinders the penetration of antibiotic molecules into the deeper layers of the biofilm. The diffusion of antibiotics is often slow and incomplete, leading to their inactivation by extracellular enzymes trapped within the matrix before they reach all target cells [14] [4].

- Chemical Binding and Inactivation: Functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, amine, hydroxyl) on EPS biopolymers can chemically interact with and sequester antibiotics. Studies show that EPS can bind antibiotics like tetracyclines, quinolones, and sulfonamides, forming stable complexes and reducing the bioavailable concentration [16]. The binding follows pseudo-second-order kinetics and the Freundlich isotherm model, indicating complex multilayer adsorption [16].

- Altered Microenvironment: The consumption of nutrients and oxygen by peripheral cells in a biofilm creates gradients, leading to nutrient depletion and slow growth in the inner layers. These dormant or "persister" cells are metabolically less active and thus less susceptible to many antibiotics that target active cellular processes [14] [4].

Troubleshooting Tip: When evaluating anti-biofilm agents, do not rely on planktonic MIC values. Instead, establish a Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC) using assays like the Calgary Biofilm Device or similar biofilm-specific models [4].

FAQ 2: My enzymatic disruption of EPS is inconsistent across bacterial species. How can I optimize this protocol?

Issue: The efficacy of EPS-degrading enzymes (e.g., proteases, DNases, amylases) varies significantly between biofilms of different species and strains.

Explanation: The relative abundance and structural role of specific EPS components (proteins, eDNA, polysaccharides) differ greatly among bacterial species. For instance:

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms are highly dependent on eDNA and certain polysaccharides (e.g., Psl, Pel) for structural integrity [13] [15] [10]. They are often susceptible to DNase treatment.

- Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis biofilms rely heavily on proteinaceous components and poly-β(1-6)-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) polysaccharide [13] [15]. They are more effectively disrupted by proteases (e.g., Savinase, Subtilisin A) or the PNAG-degrading enzyme dispersin B [13].

- Escherichia coli biofilms may be stabilized by curli fibers (amyloid proteins) and cellulose [15] [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: The table below outlines targeted enzymatic strategies based on the primary EPS composition.

| Target EPS Component | Recommended Enzymes | Example Application & Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Proteases (e.g., Serratiopeptidase, Savinase, Subtilisin A) [13]. | Savinase reduced sessile biomass of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus by ≥70%; Serratiopeptidase enhanced ofloxacin activity against sessile cells [13]. |

| Polysaccharides | Amylases, Dispersin B (targets PNAG) [13]. | α-Amylase detached S. aureus biofilms in a concentration- and time-dependent manner [13]. |

| Extracellular DNA (eDNA) | DNase I [14]. | Effective against biofilms where eDNA is a major structural scaffold (e.g., P. aeruginosa) [14] [10]. |

Optimization Protocol:

- Characterize the EPS: Begin with a basic compositional analysis of your target biofilm using colorimetric assays (e.g., Lowry for protein, Phenol-Sulfuric acid for polysaccharide) or more advanced techniques like FT-IR spectroscopy [13] [12].

- Screen Enzymes: Perform a screen using a panel of enzymes targeting different EPS components. Use a standard biofilm biomass assay (e.g., crystal violet) or viability assay (e.g., resazurin) to quantify disruption.

- Combine Therapies: Consider enzyme-antibiotic combination therapy. Enzymatic disruption of the matrix can enhance antibiotic penetration, potentially lowering the required MBEC [13] [14].

FAQ 3: How can I accurately visualize the spatial distribution and composition of EPS in my biofilm models?

Issue: Standard plating and microscopy methods fail to reveal the complex three-dimensional architecture and heterogeneous composition of the EPS matrix.

Explanation: The EPS matrix is spatially heterogeneous, with components distributed in non-homogeneous patterns [13] [12]. Understanding this architecture is crucial for investigating diffusion barriers and microenvironments.

Experimental Workflow for EPS Visualization:

Recommended Techniques:

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM): This is the gold standard for in-situ, non-destructive analysis of biofilms [12]. It allows for the optical sectioning of thick biofilms and reconstruction of their 3D architecture.

- Fluorescent Labeling:

- Spectroscopic Techniques:

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy: Provides information on the overall chemical content (proteins, polysaccharides, lipids) and their relative proportions in the biofilm matrix without the need for extensive processing [13]. Specific absorption bands correspond to functional groups in different EPS classes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents for EPS Analysis

The following table lists essential materials and reagents used in the experimental methods cited for studying EPS composition and function.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application in EPS Research |

|---|---|

| Savinase (Serine Protease) | Degrades protein components within the EPS matrix; used to study protein function and disrupt biofilm integrity [13]. |

| DNase I | Hydrolyzes extracellular DNA (eDNA); used to investigate the structural role of eDNA in biofilms and as a dispersal agent [14]. |

| Dispersin B | Specifically hydrolyzes poly-β(1-6)-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG), a key polysaccharide in staphylococcal biofilms [14] [15]. |

| Fluorescently Labeled Lectins (e.g., Con A) | Bind to specific carbohydrate residues in EPS polysaccharides; used for visualization and spatial mapping via CLSM [12] [10]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | Used to prepare competent bacterial cells for genetic transformation studies; also relevant as a divalent cation that can cross-link EPS components, influencing matrix stability [17]. |

| SYTO / Propidium Iodide Stains | Nucleic acid-binding fluorescent dyes used to label and visualize extracellular DNA (eDNA) within the biofilm matrix [10] [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions for Researchers

FAQ 1: What are the primary components of the biofilm matrix responsible for impeding antibiotic penetration? The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix is a complex, heterogeneous structure that constitutes 75-90% of the biofilm's biomass [18]. The key components involved in antibiotic sequestration are:

- Exopolysaccharides: Such as Pel, Psl, and alginate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These act as a molecular glue and can form complexes with antibiotics [18] [19].

- Extracellular DNA (eDNA): The negatively charged backbone of eDNA can bind and sequester positively charged antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides [20] [19].

- Proteins: Include secreted enzymes, cell surface adhesins, and protein subunits of cell appendages which contribute to matrix stability and can entrap antibiotics [18].

FAQ 2: How does the biofilm matrix cause a reduction in effective antibiotic concentration? The reduction is not solely due to slow diffusion. Specific binding and inactivation events occur at the biofilm surface, creating a steep concentration gradient. Key mechanisms include:

- Binding and Inactivation: Antibiotics like aminoglycosides bind to negatively charged eDNA, effectively neutralizing them [19].

- Enzymatic Degradation: Enzymes within the matrix, such as β-lactamases, can deactivate susceptible antibiotics faster than they can diffuse into the biofilm's deeper layers [20] [21].

- Neutralization by Host Components: In chronic infections, host-derived DNA from neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) can integrate into the matrix, forming a physical shield that further reduces antibiotic efficacy [19].

FAQ 3: What is the quantitative impact of biofilm-mediated resistance? Bacteria within a biofilm can exhibit a 10 to 1,000-fold increase in antibiotic resistance compared to their planktonic counterparts [20]. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Biofilm-Mediated Resistance

| Observation | Quantitative Finding | Context / Pathogen | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | 10 - 1,000 fold | General biofilm-mediated resistance | [20] |

| Resistance Development in Biofilm vs. Planktonic | 100% susceptible (planktonic) vs. ~75% resistant (biofilm) | Staphylococcus epidermidis treated with Vancomycin | [20] |

| Biofilm Producer Prevalence | 88.5% of isolates | Clinical ESKAPE pathogens (n=165) | [22] |

| Strong Biofilm Producers | 15.8% of isolates | Clinical ESKAPE pathogens (n=165) | [22] |

| Matrix Composition - Microbial Cells | 10-25% of biofilm volume | General biofilm architecture | [18] |

| Matrix Composition - EPS | 75-90% of biofilm volume | General biofilm architecture | [18] |

FAQ 4: My standard antibiotic treatments are failing against a suspected biofilm infection. What experimental approaches can I use to confirm the matrix is the cause? You should employ a combination of methods to directly test the barrier function of the matrix.

- Assay Antibiotic Penetration: Use fluorescently labeled antibiotics (e.g., vancomycin) in conjunction with Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) to visualize and quantify the diffusion profile through the biofilm.

- Enzymatic Matrix Disruption: Treat biofilms with matrix-degrading enzymes like DNase I (targets eDNA), dispersin B (targets polysaccharides), or alginate lyase (targets alginate). A significant increase in antibiotic susceptibility post-treatment strongly implicates the matrix in the resistance phenotype [18] [21].

- Check for Persister Cells: After enzymatic disruption, plate the dispersed cells on antibiotic-containing media. If the cells remain viable but do not grow, it suggests the presence of dormant persister cells, which are a separate resistance mechanism [20] [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent results in biofilm antibiotic susceptibility assays. Solution: This is often due to variability in biofilm growth and methodology.

- Standardize Biofilm Growth: Ensure consistent inoculum size, growth medium, surface material, and incubation time. Use a validated model like the Calgary biofilm device or a continuous-flow reactor for more reproducible biofilms.

- Quantify Biofilm Mass: Prior to antibiotic exposure, normalize your experiments by measuring the biofilm biomass (e.g., via crystal violet staining) or determining the number of viable cells.

- Include Proper Controls: Always include a planktonic cell control and a biofilm viability control (no antibiotic) in every experiment.

Problem: An antibiotic that is effective in planktonic kill curves shows no efficacy against the same strain in a biofilm. Solution: This is a classic sign of biofilm-specific tolerance. Your troubleshooting should focus on the mechanisms outlined in FAQ 2.

- Test for Binding: Pre-incubate the antibiotic with purified matrix components (e.g., eDNA, alginate) and assess the reduction in antimicrobial activity against planktonic cells.

- Check for Penetration: Perform the fluorescent antibiotic penetration assay described above. The issue may be failure to reach the minimum bactericidal concentration at the core of the biofilm.

- Investigate Physiological State: Use staining (e.g., with LIVE/DEAD BacLight or a metabolic dye like CTC) to determine if the inner layers of the biofilm contain a high proportion of dormant, non-growing cells that are inherently tolerant [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the Role of eDNA in Aminoglycoside Sequestration

Purpose: To determine if extracellular DNA (eDNA) in the biofilm matrix is responsible for binding and neutralizing tobramycin.

Reagents:

- Biofilm-forming bacterial strain (e.g., P. aeruginosa)

- Tobramycin sulfate

- DNase I (RNase-free)

- Cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth (CAMHB)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates

Method:

- Grow Biofilms: In a 96-well plate, incubate the standardized bacterial inoculum in CAMHB for 24-48 hours at 37°C to form mature biofilms.

- Wash Biofilms: Gently wash the biofilms twice with PBS to remove non-adherent cells.

- Experimental Groups:

- Group A (Test): Add CAMHB containing tobramycin (at desired concentration) and DNase I (100 µg/mL).

- Group B (Control): Add CAMHB containing tobramycin at the same concentration.

- Group C (Viability Control): Add CAMHB only.

- Incubate: Incubate the plate for an additional 18-24 hours at 37°C.

- Quantify Viability: Carefully aspirate the media, wash the biofilms, and disrupt them by sonication or scraping. Serially dilute and plate the suspensions on agar to determine the Colony Forming Units (CFU)/mL.

- Analysis: A statistically significant reduction in CFU/mL in Group A (DNase-treated) compared to Group B (antibiotic only) confirms that eDNA contributes to tobramycin resistance.

Protocol 2: Visualizing Antibiotic Penetration via Confocal Microscopy

Purpose: To directly observe and quantify the diffusion barrier of the biofilm matrix against a fluorescently labeled antibiotic.

Reagents:

- Biofilm strain

- BODIPY FL Vancomycin (or other fluorescent antibiotic conjugate)

- Flow cell reactor or glass-bottom dish

- Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM)

Method:

- Grow Biofilms: Grow a mature biofilm in a flow cell or on a glass-bottom dish under relevant conditions.

- Stain Biofilm Structure (Optional): Introduce a non-inhibitory nucleic acid stain (e.g., SYTO 61) to label all bacterial cells, providing structural context.

- Introduce Fluorescent Antibiotic: Stop the flow and introduce a solution of BODIPY FL Vancomycin in PBS at a physiologically relevant concentration.

- Image Time-Lapse: Immediately begin acquiring Z-stack images at regular intervals (e.g., every 5-10 minutes) using CLSM. Use separate laser channels for the antibiotic (green) and the cell stain (red).

- Analyze Data: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to plot the fluorescence intensity of the antibiotic signal across the biofilm depth over time. A shallow penetration gradient indicates a strong diffusion barrier.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying the Matrix Diffusion Barrier

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| DNase I | Degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA) in the matrix. | Testing eDNA's role in sequestering aminoglycosides or other cationic antimicrobials [19] [21]. |

| Dispersin B | Glycosyl hydrolase that degrades poly-N-acetylglucosamine (PNAG) polysaccharide. | Disrupting biofilms of staphylococcal species and other pathogens that utilize PNAG [18]. |

| Alginate Lyase | Breaks down alginate, a key polysaccharide in P. aeruginosa biofilms. | Enhancing antibiotic penetration in mucoid P. aeruginosa infections, such as in cystic fibrosis [21]. |

| Fluorescently Labeled Antibiotics (e.g., BODIPY-Vancomycin) | Visualizing and quantifying antibiotic penetration and binding in live biofilms. | Directly measuring the diffusion coefficient and penetration depth of an antibiotic using CLSM [19]. |

| Modified Carbapenem Inactivation Method (mCIM/eCIM) reagents | Detecting carbapenemase and metallo-β-lactamase production. | Determining if enzymatic degradation within the matrix contributes to β-lactam antibiotic failure [22]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

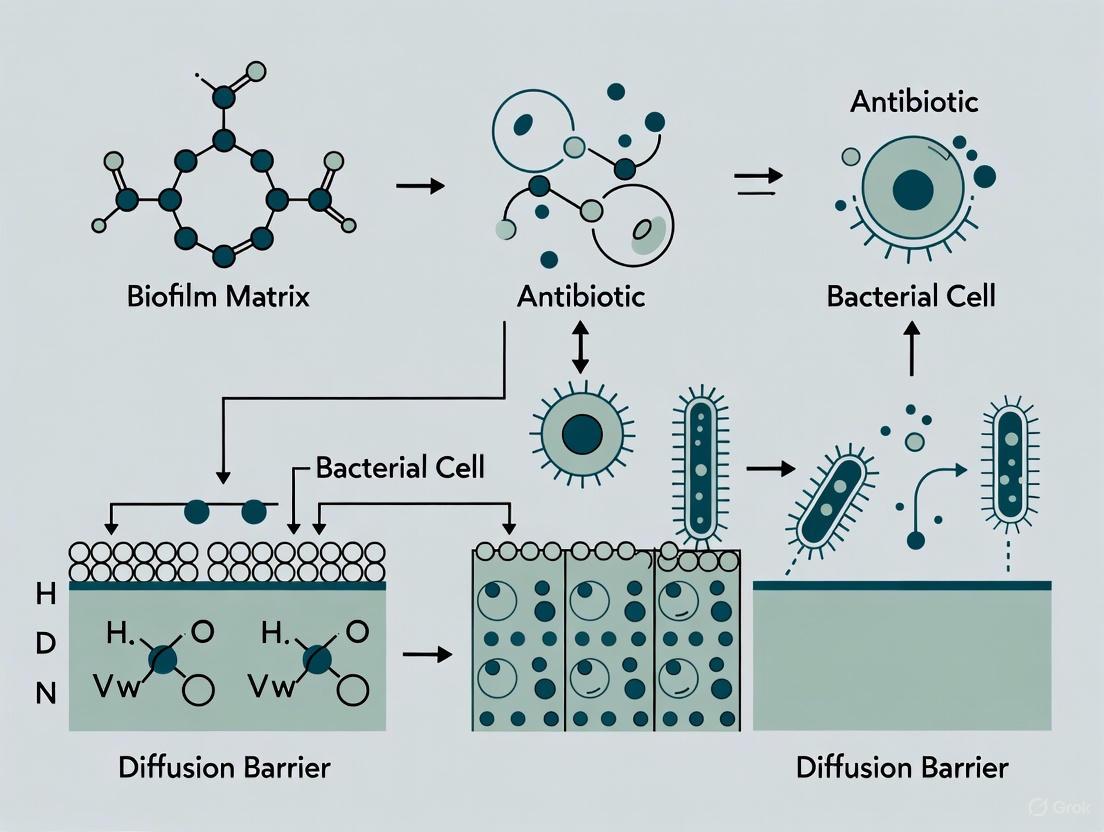

Diagram 1: Antibiotic Penetration Barrier in Biofilm

Diagram Title: Mechanisms of Antibiotic Failure in Biofilm Matrix

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Matrix Barrier Analysis

Diagram Title: Workflow to Test Matrix Role in Resistance

FAQ: Understanding Biofilm Physiology and Resistance

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the key physiological states found within a single biofilm and how do they impact antibiotic efficacy? Biofilms are not homogeneous; they contain subpopulations of bacteria in distinct physiological states. A key gradient exists from the biofilm periphery to its core: cells on the outer layers are often metabolically active, while those in the inner core can enter a slow-growing or dormant state due to nutrient and oxygen gradients [1] [3]. This is critical because many conventional antibiotics, such as β-lactams, require active cell growth to be effective. Consequently, these dormant "persister" cells can survive antibiotic treatment and lead to recurrent infections [7] [23].

How does the biofilm matrix act as a diffusion barrier against antimicrobials? The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix is a primary contributor to resistance. It can hinder antibiotic penetration through two main mechanisms: binding and neutralization, and restricted diffusion. Positively charged antibiotics like aminoglycosides can bind to negatively charged components in the matrix, such as extracellular DNA (eDNA), preventing them from reaching their cellular targets [23]. The dense, gel-like physical structure of the EPS can also simply slow down the diffusion of antimicrobial molecules, creating a protective physical barrier for the encapsulated cells [1] [7].

What is the role of fluid shear during growth in determining biofilm architecture and subsequent treatment resistance? The hydrodynamic conditions under which a biofilm grows fundamentally shape its physical characteristics. Biofilms grown under high fluid shear (e.g., in flow cells or on medical device surfaces) tend to be thinner, denser, and stiffer, with a higher protein-to-polysaccharide ratio in their matrix. In contrast, biofilms grown under low fluid shear are often thicker, more porous, and more compliant [24]. These physical properties directly influence treatment success; stiffer, high-shear biofilms can require more intense adjuvant therapies (like low-frequency ultrasound) for effective antibiotic penetration compared to their low-shear counterparts [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge: Inconsistent antibiotic susceptibility results in biofilm assays.

- Potential Cause: Variations in biofilm cultivation methods (e.g., static vs. flow conditions) leading to differences in biofilm maturity, thickness, and structure.

- Solution: Standardize growth conditions, including growth medium, incubation time, and hydrodynamic environment. Use assays like Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) to characterize biofilm architecture before treatment [24]. Report key parameters like shear stress during growth.

Challenge: Failure to eradicate biofilms in a model system despite using high antibiotic concentrations.

- Potential Cause: The presence of nutrient/gradient-induced persister cells and limited antibiotic diffusion.

- Solution: Consider combination therapies. Incorporate anti-biofilm agents that disrupt the matrix (e.g., DNase to degrade eDNA, or glycoside hydrolases to break down polysaccharides) to enhance antibiotic penetration [1] [23]. Alternatively, use low-frequency ultrasound (LFU) as a physical method to increase biofilm permeability and antibiotic diffusivity [24].

Challenge: Difficulty in visualizing and quantifying metabolic heterogeneity within a biofilm.

- Potential Cause: Reliance on endpoint, bulk measurement techniques that average out local differences.

- Solution: Employ spatially resolved techniques. Use confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) with fluorescent probes for metabolic activity (e.g., CTC for respiration, GFP reporters for stress) in combination with stains for live/dead cells. This allows for the correlation of metabolic activity with spatial location inside the biofilm [23].

Quantitative Data on Biofilm Heterogeneity and Resistance

Table 1: Impact of Growth Shear Conditions on Biofilm Physical Properties (P. aeruginosa model)

| Physical Property | Low-Shear Biofilm | High-Shear Biofilm | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Thickness | 52 ± 20 µm | 29 ± 8 µm | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| Relative Roughness | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| Matrix Protein/Polysaccharide Ratio | 0.39 ± 0.20 | 1.15 ± 0.55 | Biochemical Assay |

| Creep Compliance (Inner Region) | 5570 ± 101 Pa⁻¹ | 31 ± 1 Pa⁻¹ | Microrheology |

| Dominant Mechanical Behavior | Viscous (α = 0.91) | Elastic (α = 0.17) | Microrheology Power Law Exponent |

Table 2: Comparative Resistance and Tolerance Mechanisms in Biofilms vs. Planktonic Cells

| Characteristic | Planktonic Cells | Biofilm Communities | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inherent Resistance Level | Baseline | Up to 1000x higher [1] [7] | Standard MIC tests are inadequate. |

| Primary Resistance Mechanisms | Genetic acquired resistance | Physical barrier, physiological heterogeneity, persister cells [3] [23] | Requires multi-target therapeutic strategies. |

| Contribution of Matrix | None | Critical (binding, enzymatic degradation of antibiotics) [1] [23] | Matrix-disrupting agents are essential. |

| Effect of Fluid Shear on Treatment | Minimal | Major; determines structure and stiffness, affecting adjuvant efficacy [24] | Growth conditions must be reported. |

Core Experimental Protocols for Studying Biofilm Gradients

Protocol: Measuring Antibiotic Penetration and Binding in the Biofilm Matrix

- Preparation: Grow a mature biofilm (e.g., 48-72h for P. aeruginosa) under defined shear conditions in a flow cell or on coupons.

- Fluorescent Tagging: Label the antibiotic of interest with a fluorescent tag (e.g., fluorescently tagged vancomycin). Ensure the tag does not significantly alter the antibiotic's activity.

- Perfusion and Imaging: Perfuse the tagged antibiotic over the biofilm for a set time. Use Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) to capture time-lapse Z-stack images.

- Analysis: Quantify the fluorescence intensity profile from the top to the bottom of the biofilm. A steep gradient indicates poor penetration. Co-localization studies with matrix component stains (e.g., for eDNA or polysaccharides) can identify binding sites [23].

Protocol: Profiling Metabolic Gradients Using Fluorescent Reporters

- Strain Engineering: Use a bacterial strain harboring a fluorescent reporter plasmid (e.g., GFP) under the control of a promoter induced by metabolic stress (e.g., a starvation promoter) or low oxygen.

- Biofilm Growth: Grow the biofilm in a transparent flow cell or on a coverslip suitable for microscopy.

- Staining and Imaging: At maturity, counter-stain with a viability dye (e.g., propidium iodide). Image using CLSM.

- Data Quantification: Analyze the spatial distribution of the fluorescence signal. Higher GFP intensity in the biofilm core indicates a steeper metabolic gradient and identifies regions of dormant cells [23].

Visualization of Key Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Biofilm development leading to heterogeneity.

Diagram 2: How matrix barriers and cell physiology cause resistance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Equipment for Biofilm Microenvironment Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Flow Cell Systems | Provides controlled hydrodynamic conditions (shear) for biofilm growth. | Culturing biofilms with defined, reproducible architectures (low vs. high shear) [24]. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (CLSM) | Non-destructive, high-resolution 3D imaging of live biofilms. | Visualizing spatial distribution of metabolic activity, pH, or oxygen gradients using fluorescent probes [23]. |

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | Label-free, real-time imaging of biofilm topography and structure. | Measuring biofilm thickness, roughness, and structural changes in response to treatments [24]. |

| DNase I | Enzyme that degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA) in the matrix. | Disrupting the biofilm matrix to study eDNA's role in antibiotic binding and to enhance antimicrobial efficacy [1] [23]. |

| Tobramycin | Aminoglycoside antibiotic commonly used in biofilm research. | A model positively charged antibiotic for studying matrix binding and penetration limitations [24] [23]. |

| Low-Frequency Ultrasound (LFU) Setup | Physical adjuvant therapy to enhance biofilm permeability. | Increasing antibiotic diffusivity within the biofilm structure in combination therapy studies [24]. |

| Fluorescent Viability/Stress Probes | Chemical dyes to report on cell physiological status. | Differentiating live/dead cells and identifying subpopulations of metabolically dormant persister cells within biofilms [23]. |

ESKAPE Pathogens and Notorious Biofilm-Formers in Clinical Settings

Quantitative Profiling of ESKAPE Pathogen Resistance and Biofilm Formation

Table 1: Antimicrobial Resistance and Biofilm Formation in Clinical ESKAPE Isolates [22]

| Pathogen | Multi-Drug Resistance (MDR) Rate | Key Resistance Markers | Strong Biofilm Formers | Notable Resistance Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus faecium | 90% | vanB gene (20% VRE) | Data not specified | High resistance to fluoroquinolopes (86.67%) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 10% | mecA gene (46.7% MRSA) | Data not specified | Retained sensitivity to linezolid, SXT, gentamicin |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Elevated | Carbapenemase (34.3%) | High | Carbapenem (45.71%), Colistin (42.86%) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Elevated | Carbapenemase | High | Carbapenem (74.29%) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Relatively Lower | Carbapenemase | Moderate | Lower resistance compared to other Gram-negative pathogens |

Key Findings: A 2025 study of 165 clinical isolates revealed that 88.5% of ESKAPE pathogens form biofilms, with 15.8% being strong producers [22]. A significant correlation was observed between biofilm formation and resistance to carbapenems, cephalosporins, and piperacillin/tazobactam, suggesting biofilms play a key role in disseminating resistance to these antibiotics [22].

Essential Experimental Protocols for Biofilm Research

Function: This standard method quantifies total biofilm biomass and classifies isolates as weak, moderate, or strong biofilm producers.

Detailed Protocol:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow bacteria overnight in a suitable broth (e.g., Tryptic Soy Broth). Dilute the culture to approximately 1 x 10^6 CFU/mL in fresh, sterile broth.

- Biofilm Growth: Dispense 200 µL of the diluted inoculum into the wells of a sterile, flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plate. Include negative control wells containing sterile broth only. Seal the plate with a lid and incubate under static conditions for 24-48 hours at the optimal temperature for the test organism (e.g., 37°C for human pathogens).

- Biofilm Staining:

- Carefully remove the planktonic cells by inverting the plate and gently tapping.

- Wash the adhered biofilms twice with 200 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, to remove loosely attached cells.

- Air-dry the plate for 10-15 minutes.

- Fix the biofilms by adding 200 µL of 99% methanol to each well for 15 minutes.

- Empty the plate and allow it to dry completely.

- Stain the fixed biofilms with 200 µL of 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet solution for 5-15 minutes.

- Destaining and Quantification:

- Gently rinse the plate under running tap water to remove excess stain until the runoff is clear.

- Air-dry the plate.

- Add 200 µL of 33% (v/v) glacial acetic acid or 95% ethanol to each well to solubilize the crystal violet bound to the biofilm. Shake the plate for 10-20 minutes.

- Transfer 125 µL of the solubilized dye from each well to a new microtiter plate.

- Measure the optical density (OD) at 570-595 nm using a microplate reader.

Data Interpretation: The OD of the negative control is subtracted from the OD of test wells. Isolates are classified based on the calculated OD (ODc) as follows: Non-biofilm producer: OD ≤ ODc; Weak: ODc < OD ≤ 2xODc; Moderate: 2xODc < OD ≤ 4xODc; Strong: 4xODc < OD.

Function: Confirms the genetic potential of isolates for biofilm formation by screening for specific genes encoding surface adhesins and matrix components.

Detailed Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Purify genomic DNA from fresh bacterial cultures using a commercial extraction kit or a standard boiling method.

- PCR Master Mix Preparation: For a 25 µL reaction, combine the following components on ice:

- 12.5 µL of 2X PCR Master Mix (containing Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and reaction buffers)

- 1 µL each of forward and reverse primer (10 µM stock)

- 2 µL of template DNA

- 8.5 µL of Nuclease-Free Water

- Thermal Cycling: Program a thermal cycler with the following steps:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes

- 30-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: Primer-specific temperature for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of amplicon

- Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes

- Hold: 4°C ∞

- Amplicon Detection: Analyze the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5-2% gel) stained with GelRed, alongside a DNA molecular weight ladder, and visualize under UV light.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Biofilm Researchers

FAQ 1: The crystal violet assay shows high variability between replicates. What could be the cause and how can I improve consistency?

Answer: High variability often stems from technical inconsistencies. To improve reproducibility:

- Ensure Homogeneous Inoculum: Vortex the bacterial suspension thoroughly before aliquoting into the plate wells.

- Minimize Edge Effects: Use only the inner 60 wells of the 96-well plate. Fill the perimeter wells with sterile water or PBS to maintain uniform humidity and temperature during incubation.

- Standardize Washing: Use a multichannel pipette for consistent washing pressure and angle across all wells. Use the same volume of PBS for each wash step.

- Validate with Controls: Always include positive and negative controls. Ensure your assay can distinguish between known strong and weak biofilm-forming strains [25].

FAQ 2: My anti-biofilm compound is effective in the microtiter plate assay but fails in a more complex biofilm model. Why might this be happening?

Answer: This is a common translational challenge. Microtiter plate assays are excellent for screening but represent a simplified environment.

- Matrix Penetration Barrier: The EPS matrix in mature, complex biofilms can trap or neutralize compounds, preventing them from reaching all cells [1] [26]. Test your compound's efficacy against mature biofilms (e.g., 72-96 hours old) and consider using assays with continuous flow, which better model in vivo biofilm structures.

- Persister Cells: Biofilms contain metabolically dormant persister cells that are highly tolerant to antibiotics [1]. A viability assay (e.g., ATP measurement or colony counts) may show better efficacy than a biomass assay (crystal violet). Combine your compound with an agent that disrupts the matrix (e.g., DNase I, Dispersin B) to enhance penetration [27].

- Physiological Differences: Biofilm physiology differs from planktonic cells. Re-evaluate the compound's Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC), which is often 10-1000 times higher than the MIC for planktonic cells [1].

FAQ 3: How can I conclusively prove that a newly identified gene is involved in biofilm formation?

Answer: Beyond correlation (e.g., PCR screening), functional validation is required.

- Create a Knockout Mutant: Use gene editing tools (e.g., CRISPR-Cas) to create an isogenic mutant strain lacking the gene of interest.

- Conduct a Complementation Test: Re-introduce a functional copy of the gene on a plasmid into the mutant strain. A true biofilm-related gene will show reduced biofilm formation in the mutant, and the phenotype will be restored to wild-type levels in the complemented strain.

- Perform Phenotypic Characterization: Compare the mutant and wild-type strains using multiple, relevant biofilm assays (e.g., microtiter plate, microscopy of biofilms on relevant surfaces, colonization in a flow cell). This demonstrates that the effect is not assay-specific [25].

Research Workflow: From Resistance Profiling to Biofilm Dispersal

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for investigating and targeting biofilm-mediated resistance in ESKAPE pathogens.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents for ESKAPE Biofilm Research [22] [1] [26]

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Violet (0.1%) | Stains total biofilm biomass for quantification. | Used in standard microtiter plate assays; measures adhered cells and matrix but does not indicate viability [25]. |

| Calgary Biofilm Device | Grows multiple, uniform biofilms for high-throughput susceptibility testing. | Used for determining Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC). |

| DNase I | Degrades extracellular DNA (eDNA) in the biofilm matrix. | Used to study matrix composition and as a potential dispersal agent; can increase antibiotic efficacy [1] [27]. |

| Dispersin B | Hydrolyses polysaccharide (PNAG) in the biofilm matrix. | A specific glycoside hydrolase; shows >70% biofilm reduction in some models [27]. |

| PCR Reagents | Detects biofilm-forming and antibiotic resistance genes. | Primers for genes like mecA (MRSA), vanB (VRE), and species-specific adhesins are essential [22]. |

| Probiotic Strains (e.g., Lactobacillus spp.) | Source of natural anti-biofilm and antimicrobial compounds. | Caprine gut-derived isolates show growth inhibition and anti-biofilm effects against ESKAPE pathogens [28]. |

Tools of the Trade: Advanced Models and Techniques for Analyzing Matrix Barrier Function

In Vitro and In Silico Models for Studying Antibiotic Penetration Kinetics

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

FAQ: Why do my in silico predictions not match in vitro biofilm antibiotic efficacy results?

- Problem: Computational models predict effective antibiotic concentrations, but in vitro biofilm assays show persistent bacterial survival.

- Solution: This discrepancy often arises because standard molecular docking doesn't account for the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) penetration barrier. Implement multi-scale modeling that couples:

- Verification: Correlate in silico penetration times with in vitro time-kill curve data, where a bacteriostatic effect (inhibition of growth without killing) in vitro may indicate failed penetration predicted in silico [31].

FAQ: How can I model antibiotic combinations with different half-lives in a dynamic in vitro system?

- Problem: Simulating realistic human pharmacokinetics for drug combinations where each antibiotic has a different elimination rate.

- Solution: Use a multi-compartment in vitro model with independent pump systems.

- Protocol Note: Calibrate pump flow rates based on the known half-lives (t½) of each drug to accurately mimic human serum concentration-time profiles [33].

FAQ: What causes the "Eagle Effect" in time-kill studies with biofilms, and how is it resolved?

- Problem: Paradoxically reduced bactericidal activity at high antibiotic concentrations in time-kill assays.

- Solution: This effect is often related to pH shifts, osmolarity changes, or induction of toxin-antitoxin systems in a high-density biofilm.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Monitor pH: Ensure the growth medium does not become acidic at high bacterial densities.

- Confirm Inoculum Size: Use a standardized, pre-grown biofilm inoculum rather than planktonic overnight culture.

- Extend Time Course: Take frequent measurements (e.g., every 2-4 hours) over 24-48 hours to capture the full dynamic of bacterial killing and potential regrowth [31].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Model Validation and Quality Control

FAQ: How do I validate the structure of a homology-modeled protein target for in silico docking?

- Problem: The target bacterial protein (e.g., a quorum-sensing protein) has no experimentally resolved crystal structure, requiring homology modeling, which introduces uncertainty.

- Solution: Employ a multi-step validation protocol before docking studies:

- Ramachandran Plot Analysis: Use servers like MolProbity to assess the stereochemical quality of the modeled protein. >90% of residues should be in the most favored regions [29].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) of the Apo-Protein: Run a 100-ns simulation of the "naked" protein (without ligand). A stable root mean square deviation (RMSD) after equilibration indicates a folded, stable structure [29].

- Check C-Score: If using I-TASSER for modeling, a higher C-score (e.g., >0) indicates a more reliable model [29].

Quantitative Data for Experimental Design

Key Parameters for In Vitro PK/PD Models

Table 1: Critical Parameters for Designing Dynamic In Vitro Kinetic Models

| Parameter | Description | Consideration for Biofilms | Typical Value/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Rate | Rate of medium renewal in the system. | Slow flow mimics static biofilms (e.g., on implants); fast flow mimics shear stress conditions. | Adjusted to simulate human antibiotic half-life (e.g., for Gentamicin, t½ ~2 hrs) [32] [33]. |

| Inoculum Preparation | Method for growing the initial biofilm. | Use mature biofilms (e.g., 48-72h old) rather than planktonic cells to reflect in vivo resistance. | Pre-grow biofilm on coupons or pegs for 48 hours [34]. |

| Half-life Simulation | Simulating the exponential decline of antibiotic concentration in vivo. | Achieved by controlling the dilution rate via the hose pump. | Flow rate (K) = ln(2) / simulated t½ [33]. |

| Sampling Frequency | Intervals for collecting samples to determine bacterial counts and antibiotic concentration. | Frequent sampling is needed to capture the dynamic kill/regrowth kinetics in biofilms. | At fixed intervals (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8, 24h) [32] [31]. |

| Synergy Analysis | Method to determine if a drug combination is synergistic. | For kinetic models, the relative reduction in bacterial count by the combination vs. individual components is calculated over time [32]. | Analogous to FIC indices from checkerboard assays [32]. |

Key Metrics for PD Analysis

Table 2: Essential Pharmacodynamic (PD) Metrics and Their Interpretation

| Metric | Definition | Significance in Biofilm Research | Methodological Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) | The lowest antibiotic concentration that inhibits visible growth. | Often much higher for biofilm-derived cells than for planktonic cells, indicating tolerance. | Determined via broth microdilution using standardized inoculum [35] [31]. |

| Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC) | The lowest concentration that eradicates a pre-formed biofilm. | A more clinically relevant measure for biofilm-associated infections. | Assessed using peg-lid assays (e.g., Calgary Biofilm Device) after exposing mature biofilms to antibiotics [34]. |

| Time-Kill Curve | A dynamic profile of changes in viable bacterial count over time at a fixed antibiotic concentration. | Reveals the rate and extent of bactericidal activity and can detect regrowth of resistant subpopulations in biofilms. | Samples are plated for viable counts at multiple time points (e.g., 0-24h) [31]. |

| Post-Antibiotic Effect (PAE) | The persistent suppression of bacterial growth after brief antibiotic exposure. | Can be prolonged in biofilms, influencing dosing interval design. | Determined by comparing growth recovery of exposed vs. unexposed bacteria after antibiotic removal [31]. |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Dynamic In Vitro Kinetic Model for Antibiotic Combinations

Purpose: To simulate the in vivo concentration-time profiles of two antibiotics with different half-lives and assess their combined activity against a biofilm [32] [33].

Materials:

- Bioreactor vessel with magnetic stirrer.

- Two or more programmable hose pumps.

- Sterile nutrient broth reservoir.

- Antibiotic stock solutions.

- Waste collection vessel.

- Biofilm-coated coupons (e.g., titanium for implant studies).

Method:

- Setup: Place the pre-grown biofilm coupon into the bioreactor vessel.

- Priming: Fill the system with nutrient broth. Start the primary pump to continuously add fresh broth and remove an equal volume of waste, establishing a baseline equilibrium.

- Dosing: Inject a bolus of both antibiotics into the central chamber to achieve the target starting concentrations (e.g., peak serum levels).

- Kinetic Simulation:

- The primary pump simulates the systemic clearance shared by both drugs.

- Activate the secondary pump to continuously add a solution of the longer-half-life antibiotic, compensating for its slower elimination that cannot be mimicked by the primary pump alone [32].

- Sampling: Aseptically collect samples from the central chamber at predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours).

- Analysis:

- Viable Counts: Serially dilute samples, plate on agar, and incubate to determine CFU/mL.

- Antibiotic Assay: Use HPLC or bioassay to verify antibiotic concentrations over time.

Protocol: Integrated In Silico Workflow for Predicting Antibiotic-Biofilm Interaction

Purpose: To computationally predict the binding affinity and stability of an antibiotic or anti-virulence agent with a quorum-sensing protein target and infer its impact on biofilm formation [29].

Method:

- Target Identification & Preparation: Select a key protein involved in biofilm regulation (e.g., LuxS). If an experimental structure is unavailable, perform homology modeling using I-TASSER and validate with Ramachandran plots [29].

- Ligand Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the antibiotic/compound from PubChem. Energy-minimize it using software like UCSF Chimera [29].

- Molecular Docking: Perform docking simulations to predict the binding pose and affinity (e.g., binding energy ΔG). Use AutoDock Vina or similar tools.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation:

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in a triclinic box using water models (e.g., TIP3P).

- Use a force field (e.g., CHARMM36). Energy minimize the system.

- Equilibrate first under NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and then NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensembles.

- Run a production MD simulation for a sufficient time (e.g., 100-300 ns) to study stability [29] [36].

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate key parameters to assess complex stability:

- RMSD: Backbone root mean square deviation to measure overall stability.

- RMSF: Root mean square fluctuation to identify flexible regions.

- Rg: Radius of gyration to measure compactness.

- H-Bonds: Number of consistent hydrogen bonds between ligand and protein [29].

- Binding Energy Calculation: Use Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MMPBSA) method to calculate the final free energy of binding from the MD trajectory [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Antibiotic Penetration Studies

| Category | Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software & Databases | I-TASSER | Protein structure prediction and function annotation via homology modeling. | Used for building models of quorum-sensing proteins when crystal structures are unavailable [29]. |

| GROMACS | A versatile package for performing MD simulations, energy minimization, and trajectory analysis. | Open-source software suitable for simulating antibiotic-protein interactions in a solvated environment [29]. | |

| PubChem | A database of chemical molecules and their activities. Source for 3D structures of antibiotics and bioactive compounds. | Provides .sdf files for ligands like coumaric acid, which can be energy-minimized for docking [29]. | |

| SWISS ADME | A web tool to compute ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) parameters and drug-likeness. | Predicts physicochemical properties (e.g., LogP, TPSA) of novel compounds early in the research pipeline [29]. | |

| In Vitro Models | Hollow Fiber Infection Model (HFIM) | An advanced in vitro system that more closely simulates human in vivo PK parameters for antibiotic studies over extended periods. | Allows for prolonged study of antibiotic effects on biofilms under dynamic concentration profiles [31]. |

| Calgary Biofilm Device | A high-throughput platform for growing multiple equivalent biofilms and assessing MBEC. | Essential for standardizing biofilm susceptibility testing [34]. | |

| Computational Resources | CHARMM Force Fields | A set of force fields for simulating biomolecular systems, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. | Commonly used (e.g., CHARMM36) in MD simulations for biomolecular studies [29]. |

| UCSF Chimera | An extensible molecular modeling system for interactive visualization and analysis. | Used for ligand preparation, visualization of docking results, and trajectory analysis [29]. |

Imaging and Analytical Techniques to Visualize Drug Distribution in Biofilms

FAQs: Core Concepts and Techniques

1. Why is visualizing drug distribution in biofilms critical for antibiotic resistance research?

Biofilms are communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. This matrix acts as a critical diffusion barrier, trapping and slowing the penetration of antimicrobial agents [7] [20]. Bacteria within a biofilm can exhibit a 10 to 1,000-fold increase in antibiotic resistance compared to their free-floating (planktonic) counterparts [20]. Visualizing how drugs distribute and penetrate this matrix is essential to understand the mechanisms of biofilm-specific tolerance and to develop more effective treatments that can eradicate these persistent infections [37].

2. What are the key challenges in imaging drug distribution within biofilms?

The primary challenges stem from the biofilm's complex physical and chemical nature:

- Structural Complexity: The EPS matrix is a highly hydrated, heterogeneous mixture of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA (eDNA), which can hinder the penetration and detection of drugs [37].

- Sensitivity and Resolution: Techniques must be sensitive enough to detect often low concentrations of a drug amidst a dense biological background and provide sufficient spatial resolution to show distribution within the biofilm's 3D structure [37] [38].

- Chemical Specificity: The method must reliably distinguish the drug signal from the myriad of molecules present in the biofilm matrix [38].

3. Which molecular imaging techniques are best suited for studying drug distribution in biofilms?

No single technique provides a complete picture; a correlative approach is often most powerful. The table below summarizes the primary techniques and their applications.

Table 1: Molecular Imaging Techniques for Biofilm Drug Distribution Studies

| Technique | Key Principle | Information Gained on Drug Distribution | Spatial Resolution | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) [37] [38] | Maps the spatial distribution of ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio. | Direct, label-free detection and mapping of the drug molecule and its metabolites. | ~1-100 µm (technique-dependent) | High chemical specificity; can detect unknown compounds. | Requires specialized equipment and expertise; can be semi-destructive. |

| Raman Spectroscopy [39] [38] | Measures inelastic scattering of light to provide a molecular "fingerprint." | Provides information on the overall biochemical composition and can track drug presence and interaction. | ~0.5-1 µm | Label-free; can be used for live, hydrated biofilms. | Weak signal can be overwhelmed by background; requires complex data analysis. |

| Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) [37] | Uses fluorescent labels and laser scanning to create optical sections. | Indirect visualization via fluorescently tagged antibiotics or dyes. | ~0.2-0.5 µm | Excellent for 3D visualization of structure and co-localization. | Requires fluorescent labeling, which may alter drug properties. |

4. Can machine learning assist in predicting antibiotic susceptibility in biofilms?

Yes. Conventional antibiotic susceptibility tests (ASTs) often fail with biofilms because they use planktonic bacteria. Recent research uses machine learning models trained on data from various analytical techniques to predict biofilm-specific susceptibility. For example:

- Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has been used to predict the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of tobramycin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms with 97.83% accuracy (within one dilution) [39].

- Multi-excitation Raman Spectroscopy (MX-Raman) has shown high performance in predicting the biofilm prevention concentration (BPC), achieving 80.43% accuracy [39]. These approaches represent a significant shift toward more predictive, biofilm-aware ASTs.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Correlative Optical Spectroscopy and Mass Spectrometry Imaging

This protocol is adapted from a methodology designed for correlative imaging of drug distribution in skin tissues, which is directly applicable to biofilm sections [38].

Experimental Goal: To precisely overlay high-resolution structural information from optical spectroscopy with highly sensitive chemical mapping from mass spectrometry on the same biofilm sample.

Detailed Protocol:

Sample Preparation:

- Grow biofilms on an appropriate substrate (e.g., medical-grade material, porous membrane).

- Apply the drug of interest under desired conditions (e.g., specific concentration, time).

- Snap-freeze the biofilm and embed it in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound.

- Section the biofilm into thin slices (5-20 µm) using a cryostat and mount them on a compatible microscope slide.

Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) Microscopy:

- Setup: Use a water immersion objective lens (e.g., 40x magnification) with a short working distance air condenser lens.

- Imaging: Place the mounted sample on the stage. Set laser power to a level that provides a good signal-to-noise ratio without damaging the tissue.

- Acquire a mosaic image of the entire section. Then, select a Region of Interest (ROI) and acquire high-resolution images (e.g., 512x512 pixels) at key wavenumbers:

- 2,850 cm⁻¹: Corresponds to CH₂ stretching, visualizing lipids and general biomass.

- 1,666 cm⁻¹: Corresponds to amide I, visualizing proteins [38].

Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS):

- Sample Transfer: Immediately transfer the same sample from the SRS microscope to the ToF-SIMS setup.

- Acquisition Parameters:

- Set ion polarity (e.g., negative ion mode for many drugs).

- Use a duty cycle of 100 ms and a mass range of 0-900 m/z.

- For the ROI, set a field of view (e.g., 0.5 x 0.5 mm) with a resolution of 256 x 256 pixels.

- Use an electron flood gun for charge compensation [38].

Data Analysis and Image Registration:

- Data Extraction: Use specialized software (e.g., SurfaceLab 7.1 for ToF-SIMS) to extract mass spectra and ion images.

- Registration: Reduce both the SRS and ToF-SIMS images to three dimensions using algorithms like Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF). Visualize them as RGB channels.

- Use a software tool (e.g., MATLAB's

cpselect) to select matching features between the two images. Perform image transformation to align the ToF-SIMS data (fixed image) with the optical SRS data (moving image) [38]. - Overlay: Once registered, overlay the datasets by assigning the respective images to RGB channels to create a correlative map showing drug location within the biofilm structure.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Correlative Imaging

| Item | Function / Application in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cryostat | For sectioning frozen biofilm samples into thin, consistent slices for imaging. |

| Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) Compound | An embedding medium that supports the biofilm structure during freezing and sectioning. |

| Water Immersion Objective Lens | Provides high-resolution imaging for SRS microscopy with minimal aberration. |

| Software (e.g., SurfaceLab, MATLAB) | For data acquisition, mass spectrum calibration, and advanced image processing/registration. |

Troubleshooting Common Issues:

- Problem: Poor Signal-to-Noise in SRS Imaging.

- Cause: Laser power may be too low, or the biofilm may be too thick or heterogeneous.

- Solution: Optimize laser power settings. Ensure sections are of uniform thickness. Increase line averaging during acquisition, though this will increase scan time.

- Problem: Charging Effects in ToF-SIMS.

- Cause: The biofilm sample is not sufficiently conductive, leading to a buildup of charge from the primary ion beam.

- Solution: Ensure the electron flood gun is correctly calibrated and operating. Apply a thin, conductive coating (if compatible with the analysis) or use lower primary ion currents [38].

- Problem: Poor Image Registration/Alignment.

- Cause: Lack of distinct, matching features between the SRS and ToF-SIMS images, or significant sample deformation between analyses.

- Solution: Use fiducial markers on the sample slide prior to analysis. Ensure the sample is transferred carefully and analyzed promptly after SRS imaging to minimize degradation or drift.

Guide 2: Addressing Biofilm Detection and Variability in Drug Response

Experimental Goal: To reliably detect and quantify biofilm formation, which is a prerequisite for meaningful drug distribution studies, and to account for heterogeneity in biofilm populations.

Detailed Protocol: Tissue Culture Plate Method (TCPM) - The Gold Standard [40]

- Biofilm Growth:

- Inoculate a loopful of test bacteria into 10 mL of trypticase soy broth supplemented with 1% glucose.

- Incubate for 24 hours.

- Biofilm Formation in Microplate:

- Dispense 180 µL of sterile trypticase soy broth into wells of a sterile 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene plate.

- Add 20 µL of the bacterial suspension to each well (1:10 dilution).

- Cover the plate and incubate at 37°C for 24 hours.

- Biofilm Staining and Quantification:

- Gently shake the plate and discard the contents to remove planktonic cells.

- Wash each well 3-4 times with sterile distilled water to remove non-adherent cells.

- Fix the adhered biofilm with 200 µL of 2% sodium acetate for 30 minutes.

- Wash the wells again.

- Stain the biofilm with 200 µL of 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes.

- Wash the plate thoroughly and let it dry inverted.

- Elute the bound dye with 200 µL of 95% ethanol or acetic acid.

- Measure the optical density (OD) of the eluted dye at 570-595 nm using a microplate reader [40].

Troubleshooting Common Issues:

- Problem: High Variability in Biofilm Formation Between Replicates.

- Cause: Inconsistent inoculation density, uneven temperature in the incubator, or plate edge effects.

- Solution: Standardize the initial bacterial suspension to a specific OD (e.g., 0.5 McFarland). Use a plate sealer to prevent evaporation and place the plate in the center of a well-calibrated incubator. Include control wells with broth only to subtract background.

- Problem: Drug Response Does Not Correlate with Planktonic AST Results.

- Cause: This is expected. Biofilms possess distinct tolerance mechanisms, including persister cells (dormant, tolerant cells) and altered microenvironments (e.g., low oxygen, acidic pH) that are not present in standard ASTs [7] [20].

- Solution: Use biofilm-specific susceptibility metrics like the Biofilm Prevention Concentration (BPC), defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that prevents at least 90% of biofilm growth compared to the control [39]. Incorporate techniques like IMC or Raman spectroscopy that measure the metabolic response of the biofilm community [39].

Visualizing Workflows and Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate a general experimental workflow for correlative imaging and a key signaling pathway that influences biofilm properties relevant to drug penetration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is measuring biofilm thickness critical in antimicrobial resistance research? Biofilm thickness is not just a structural metric; it is a direct determinant of treatment efficacy. Thicker biofilms can create significant physical and physiological barriers that reduce antibiotic penetration and foster heterogeneous microenvironments. This can lead to up to a 1000-fold increase in antibiotic resistance compared to planktonic cells [41]. Furthermore, an optimal thickness is context-dependent; for instance, in bioelectrochemical systems, a maximum current density was observed at a thickness of 100–150 µm, beyond which mass transfer limitations occur [42]. Accurate thickness measurement is therefore essential for understanding and overcoming treatment failures.

FAQ 2: My antibiotic diffusion assays are inconsistent. What key factors should I control? Inconsistent results often stem from unaccounted for variability in biofilm biology and experimental conditions. Key factors to control include:

- Biofilm Architecture: Biofilms are inherently heterogeneous. Ensure you sample multiple locations or use techniques that provide spatial averages (e.g., OCT) [43] [44].

- Sorption and Reaction: The antibiotic may not just diffuse; it can be bound (sorbed) or degraded (e.g., via enzymatic reaction) by the biofilm matrix [45]. These processes must be characterized for your specific antibiotic-biofilm pair.

- Nutrient and Growth Conditions: These drastically affect biofilm matrix composition, density, and thereby diffusion resistance [41]. Standardize growth media and incubation times.

FAQ 3: What are the primary techniques for non-invasive biofilm thickness monitoring, and how do I choose? The choice of technique depends on your required resolution, whether you need in-situ or ex-situ measurement, and your access to equipment. The following table summarizes key technologies:

Table 1: Non-Invasive Biofilm Thickness Measurement Techniques

| Technique | Typical Resolution | Key Principle | Primary Application Context | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) [43] [44] [42] | ~1 µm | Interferometry with near-infrared light to capture 2D/3D cross-sectional images. | Lab-scale; in-situ monitoring of biofilm development on transparent surfaces. | Advantages: Non-invasive, real-time, provides structural detail.Limitations: Often requires manual analysis; limited penetration of dense biofilms. |

| Ultrasound-based Sensors [46] | ±5 µm | Measures the time-of-flight of an ultrasonic pulse reflected from the biofilm-metal interface. | Industrial water systems; real-time, in-situ monitoring. | Advantages: Robust, suitable for opaque systems, direct thickness reading.Limitations: Lower resolution than OCT. |

| Heat-Transfer Based Sensors [42] | N/A (measures fouling factor) | Measures the reduction in heat transfer across a fouled surface. | Industrial systems (e.g., cooling towers, bioelectrochemical systems). | Advantages: In-situ, real-time, correlates with operational efficiency.Limitations: Does not directly measure thickness; requires calibration. |

FAQ 4: How can I quantify biofilm density and its effect on diffusion? Directly measuring the density of a hydrated biofilm is challenging. A common and effective proxy is to use Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) in combination with other methods [44]. The workflow is:

- Use OCT to measure the biofilm thickness and total biovolume.

- Use a parallel method to quantify the total number of cells (e.g., via Colony Forming Units - CFU) or total biomass (e.g., protein content).

- Calculate an areal density (e.g., CFU per unit area) or volumetric density (e.g., CFU per unit volume of biofilm). In a study on MRSA biofilms, this combined approach (OCT + bioluminescence) was necessary to accurately predict the viable bacterial load from the bioluminescent signal, as density affects metabolic readouts [44].

FAQ 5: What are the emerging technologies for biofilm parameter analysis?

- Machine Learning/AI: Deep learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), can now predict biofilm thickness directly from simple surface images, potentially bypassing the need for complex OCT systems [43].

- Large-Area Automated AFM: This technique overcomes the traditional limitation of small scan areas, enabling high-resolution (nanometer-scale) topological and mechanical characterization over millimeter-scale areas, revealing details like flagellar interactions and single-cell orientation within biofilms [47].

- Molecular Analysis: Monitoring Quorum Sensing (QS)-related mRNA (e.g., lasI gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa) in effluent water shows promise as a non-invasive proxy for detecting biofilm dispersion in systems like drinking water distribution networks [48].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide for Penetration Failure in Diffusion Assays

Problem: Antibiotics are failing to penetrate the biofilm, leading to treatment resistance.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Biofilm Diffusion Barriers

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| No antibiotic detected in biofilm core. | Catalytic degradation: e.g., β-lactamases rapidly inactivating the antibiotic [45]. | - Measure antibiotic concentration in biofilm supernatant vs. core.- Test for presence of specific enzymes (e.g., with nitrocefin for β-lactamase). | - Use enzyme-stable antibiotics or combine with enzyme inhibitors.- Increase antibiotic concentration (if toxicity allows). |

| Antibiotic penetrates slowly but is not degraded. | Reversible sorption: Antibiotic molecules binding to components of the Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) [45] [41]. | - Conduct sorption isotherm experiments with isolated EPS components. | - Use antibiotics with low binding affinity to common EPS components (e.g., DNA, polysaccharides).- Incorporate EPS-disrupting agents (e.g., DNase, dispersin B). |