The VBNC State: Unlocking the Mechanisms of Extreme Antibiotic Tolerance in Dormant Bacteria

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) state, a critical survival mechanism in bacteria characterized by a complete loss of culturability on standard media coupled...

The VBNC State: Unlocking the Mechanisms of Extreme Antibiotic Tolerance in Dormant Bacteria

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the Viable But Non-Culturable (VBNC) state, a critical survival mechanism in bacteria characterized by a complete loss of culturability on standard media coupled with significantly enhanced tolerance to antimicrobials. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental physiological and molecular hallmarks that differentiate VBNC cells from their culturable counterparts, with a focus on mechanisms driving multi-antibiotic tolerance. The content details advanced methodological approaches for inducing, detecting, and quantifying VBNC cells, overcoming the limitations of conventional culture-based assays. We further investigate the molecular underpinnings of this robust tolerance, including toxin-antitoxin systems, metabolic downregulation, and stress response pathways, while contrasting the VBNC state with persister cells and genetic antibiotic resistance. The synthesis of current knowledge highlights the VBNC state as a major contributor to recurrent infections and antibiotic treatment failure, urging the development of novel therapeutic strategies that target this dormant bacterial population.

VBNC State Fundamentals: Defining a Stealth Survival Strategy and Its Public Health Threat

The viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state represents a unique survival strategy employed by numerous bacterial species when confronted with adverse environmental conditions. Cells in the VBNC state undergo a dramatic physiological transformation, losing the ability to form colonies on conventional growth media while maintaining metabolic activity and viability. This review comprehensively examines the VBNC state, with particular emphasis on its profound implications for antibiotic susceptibility and public health. We systematically compare the antibiotic tolerance of VBNC cells against their culturable counterparts, present detailed experimental protocols for VBNC induction and detection, and analyze the molecular mechanisms underlying this dormant state. The findings synthesized herein reveal that VBNC cells exhibit significantly enhanced tolerance to antimicrobial agents, presenting substantial challenges for clinical treatment, food safety, and public health surveillance.

The VBNC State: A Survival Paradox

Definition and Historical Context

The viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state is defined as a dormant condition in which bacteria are alive and metabolically active but cannot form colonies on standard laboratory media that normally support their growth [1] [2]. This state was first explicitly described in 1982 by Xu et al., who observed that marine Vibrio species maintained viability despite losing culturability under certain conditions [2]. The VBNC state represents a distinct survival strategy, different from sporulation or stationary-phase dormancy, employed primarily by non-spore-forming bacteria to withstand potentially lethal environmental stresses [2] [3].

Induction Conditions and Characteristics

Bacteria enter the VBNC state in response to various environmental stresses, including but not limited to:

- Nutrient starvation [1] [2]

- Temperature extremes (both high and low) [1] [2]

- Osmotic stress [1] [2]

- Oxygen availability fluctuations [2]

- Chlorination and other disinfectant treatments [4]

- Exposure to antibiotics [3]

- Extreme pH levels [2]

The transition to the VBNC state is accompanied by significant physiological and morphological changes. Cells typically undergo reductive division, resulting in smaller, rounded morphology [1]. They demonstrate reduced nutrient transport, lower rates of respiration, decreased synthesis of macromolecules, and significantly reduced metabolic activity [1] [2]. Despite these reductions in metabolic processes, VBNC cells maintain cellular integrity, possess high ATP levels, exhibit membrane potential, and retain their plasmids [2]. Perhaps most significantly from a public health perspective, many pathogens retain virulence potential while in the VBNC state and can resuscitate when environmental conditions become favorable [1] [2].

Detection Methodologies: Beyond Conventional Culturing

Limitations of Culture-Based Methods

Conventional culture-based detection methods, including standard plate counts, fail to detect VBNC cells, leading to false-negative results in clinical, food safety, and environmental monitoring contexts [5] [2] [3]. This limitation poses significant public health risks, as VBNC pathogens may remain undetected in water supplies, food products, and clinical specimens [2]. The inability of culture-based methods to detect VBNC cells has been implicated in several disease outbreaks where standard testing failed to identify pathogens [2].

Advanced Detection Techniques

To address the limitations of culture-based methods, researchers have developed various molecular and technological approaches for VBNC cell detection:

Table 1: Advanced Methods for VBNC Cell Detection

| Method | Principle | Target Organisms | Sensitivity | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMA/ddPCR | Propidium monoazide dye penetration inhibition + digital PCR | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Absolute quantification without standard curve | Clinical samples, fecal specimens [6] |

| vqPCR | Viable quantitative PCR with DNA intercalating dyes | Vibrio parahaemolyticus, V. cholerae | 20 fg DNA (3.5 cells) for V. parahaemolyticus | Retail seafood safety testing [5] |

| AI-Enabled Hyperspectral Microscopy | Spectral profile analysis via deep learning | E. coli K-12 | 97.1% classification accuracy | Rapid food safety screening [7] |

| Flow Cytometry with Viability Staining | Membrane integrity assessment via fluorescent dyes | Various bacteria | Varies by dye and instrument | Environmental monitoring [1] [8] |

| Transcriptomic Analysis (RNA-seq) | Global gene expression profiling | E. coli, Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Gene-level expression changes | Mechanism studies [9] [4] |

Detailed Protocol: PMA-ddPCR for VBNC Quantification

The PMA-ddPCR method represents one of the most advanced approaches for absolute quantification of VBNC cells without requiring a standard curve [6]:

Reagents and Equipment:

- Propidium monoazide (PMA) stock solution (e.g., Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA)

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit, Promega)

- ddPCR system with droplet generator and reader

- Halogen light source (650W)

- Species-specific primers for single-copy genes

Procedure:

- PMA Treatment Optimization:

- Test PMA concentrations ranging from 5 μM to 200 μM

- Incubate samples with PMA in the dark for 5-30 minutes at room temperature

- Expose to halogen light source (20cm distance) for 15 minutes with samples on ice

- Determine optimal PMA concentration and incubation time that effectively suppress DNA amplification from dead cells

DNA Extraction:

- Extract genomic DNA from 200 μL cell suspensions using purification kit

- Elute DNA in appropriate preservation solution

- Store at 4°C if processing immediately or at -20°C for long-term storage

Droplet Digital PCR:

- Prepare reaction mixture with template DNA, ddPCR supermix, and primers targeting at least three single-copy genes (e.g., KP, rpoB, adhE for K. pneumoniae)

- Generate droplets using droplet generator

- Perform PCR amplification with optimized thermal cycling conditions

- Read droplets using droplet reader

- Analyze data using Poisson statistics to obtain absolute copy numbers without standard curves

Validation:

- Compare results with culture-based methods for culturable cells

- Confirm VBNC state by absence of growth on appropriate media

- Use fluorescence microscopy with live/dead staining as correlative method

Genetic Regulation of the VBNC State

The transition into the VBNC state involves complex genetic regulation. Transcriptomic analyses of VBNC cells have revealed significant alterations in gene expression patterns. In E. coli, genes related to fimbrial-like adhesin protein, putative periplasmic pilin chaperone, transcriptional regulation, antibiotic resistance, and stress response are significantly regulated in the VBNC state [4]. Similarly, proteomic studies of Vibrio parahaemolyticus have identified 429 differentially expressed proteins during resuscitation compared to VBNC cells, with 330 up-regulated and 99 down-regulated proteins [9].

Type II toxin-antitoxin (TAS) systems play a crucial role in the genetic control of VBNC formation [3]. These systems typically contain two genes encoding a stable toxin and an unstable antitoxin. Under stress conditions, antitoxins are degraded by cellular proteases, releasing toxins that cause a sharp decrease in translation, replication, and cell growth, thereby inducing the VBNC state [3]. Additional global regulators, including rpoS and oxyR, also contribute to this complex regulatory network [3].

Signaling Pathways in VBNC State Transitions

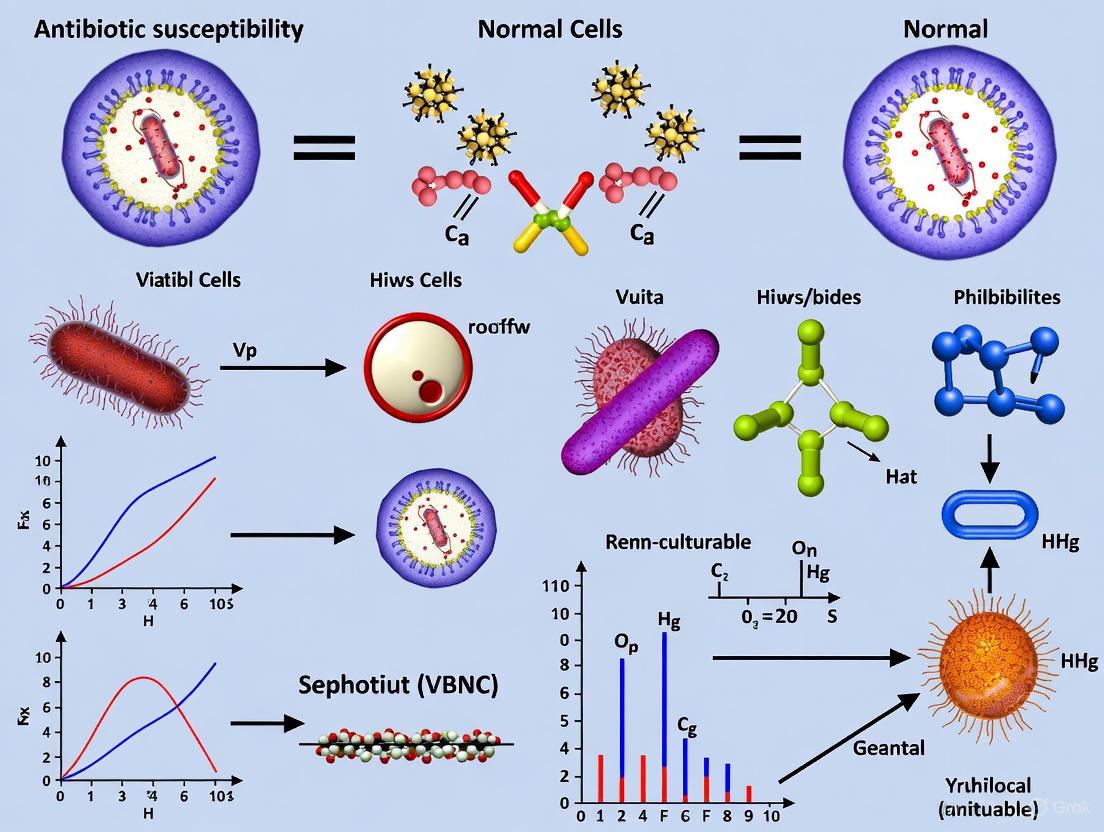

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways involved in VBNC induction and resuscitation:

Antibiotic Susceptibility: VBNC vs Normal Cells

Comparative Antibiotic Tolerance Profiles

The antibiotic tolerance of VBNC cells represents one of the most significant characteristics of this physiological state. Multiple studies have demonstrated that VBNC cells exhibit dramatically enhanced tolerance to diverse classes of antibiotics compared to their culturable counterparts.

Table 2: Comparative Antibiotic Susceptibility of VBNC vs Normal Cells

| Bacterial Species | Induction Method | Antibiotic Challenge | Normal Cell Response | VBNC Cell Response | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli [4] | Low-level chlorination (0.5 mg/L) | Ampicillin (200 μg/mL), Ofloxacin (5 μg/mL) | Susceptible at standard MIC | Tolerant (~128× MIC Amp, ~64× MIC Ofx) | Reduced metabolic activity, membrane modifications, stress response gene activation |

| Vibrio vulnificus [3] | Low temperature storage | Multiple antibiotic classes | Susceptible at standard MIC | Highly tolerant to various antibiotics | Toxin-antitoxin system mediated dormancy, general stress response |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae [6] | Artificial seawater at 4°C | Ciprofloxacin (3-18 μg/mL) | Inhibited growth | Maintained resuscitation capability after antibiotic removal | Reduced membrane permeability, metabolic shutdown |

| Multiple species [3] | Various environmental stresses | Broad-spectrum antibiotics | Growth inhibition | Significantly enhanced tolerance | Phenotypic plasticity without genetic changes |

Molecular Basis of Antibiotic Tolerance in VBNC Cells

The extraordinary antibiotic tolerance of VBNC cells stems from multiple interconnected physiological and molecular adaptations:

Metabolic Downregulation: The significantly reduced metabolic activity in VBNC cells decreases the efficacy of many antibiotics that target active cellular processes [3]. Since most antibacterial agents require some degree of metabolic activity for their mechanisms of action, the dormant state of VBNC cells provides inherent protection.

Membrane Modifications: VBNC cells undergo substantial changes in their cell envelope, including increased cross-linking in peptidoglycan, modifications to membrane fatty acid composition, and alterations in outer membrane protein profiles [2] [4]. These changes reduce membrane permeability, limiting antibiotic penetration into the cell.

Stress Response Activation: Transcriptomic analyses have revealed that VBNC cells upregulate various stress response genes, including those encoding chaperones, oxidative stress defense proteins, and DNA repair enzymes [4]. This enhanced stress response capability contributes to the increased antibiotic tolerance.

Toxin-Antitoxin System Mediated Dormancy: The activation of type II toxin-antitoxin systems leads to the specific inhibition of essential cellular processes, including translation and replication [3]. This regulated dormancy directly counteracts the mechanisms of many bacteriostatic and bactericidal antibiotics.

Research Reagent Solutions for VBNC Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VBNC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in VBNC Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Stains | LIVE/DEAD BacLight kit, SYTO 9/propidium iodide | Differentiate viable/damaged cells based on membrane integrity | Combine with microscopy or flow cytometry; cannot confirm culturability [10] [8] |

| DNA Binding Dyes | Propidium monoazide (PMA), Ethidium monoazide (EMA) | Selective amplification from viable cells with intact membranes | PMA preferred over EMA due to lower cytotoxicity to viable cells [5] [6] |

| Growth Media | Tryptic Soy Broth/Agar with modifications | Culturability assessment and resuscitation studies | May require additives (catalase, pyruvate) to reduce H₂O₂ stress [9] [3] |

| Induction Chemicals | Lutensol A03 with ammonium carbonate, Hydrogen peroxide, Peracetic acid | Controlled VBNC state induction | Lutensol/ammonium carbonate enables rapid induction (1 hour) for V. parahaemolyticus and V. cholerae [5] |

| Molecular Biology Kits | DNA/RNA extraction kits, Proteomic preparation kits | Downstream molecular analyses | Critical for transcriptomic and proteomic studies of VBNC mechanisms [9] [4] |

| PCR Reagents | qPCR/ddPCR master mixes, Species-specific primers | Detection and quantification of VBNC cells | Target single-copy genes; ddPCR enables absolute quantification without standard curves [6] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The VBNC state represents a significant challenge in clinical microbiology, food safety, and public health. The dramatically enhanced antibiotic tolerance of VBNC cells, combined with their ability to evade detection by conventional culture-based methods, creates a perfect storm for persistent infections and undetected contamination. The molecular mechanisms underlying VBNC formation—including toxin-antitoxin system activation, global transcriptomic reprogramming, and membrane modifications—provide insights into potential strategies for combating this dormant state.

Future research should focus on developing therapeutic approaches that specifically target VBNC cells, potentially by interfering with resuscitation signals or exploiting unique vulnerabilities of the dormant state. Additionally, the integration of advanced detection methods like PMA-ddPCR and AI-enabled hyperspectral microscopy into routine screening protocols could significantly improve our ability to identify VBNC pathogens in clinical, food, and environmental samples.

The systematic comparison of antibiotic susceptibility between VBNC and normal cells presented in this review underscores the critical need to consider phenotypic heterogeneity and dormancy states when designing antibiotic treatment regimens and public health interventions. As our understanding of the VBNC state continues to evolve, so too must our approaches to detecting and combating these elusive bacterial populations.

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state represents a critical survival strategy adopted by numerous bacterial species when confronted with adverse environmental conditions [11]. In this dormant state, bacteria lose the ability to form colonies on routine culture media—the gold standard of microbiological detection—while maintaining metabolic activity and cellular integrity [3] [12]. This phenomenon presents substantial challenges for clinical diagnostics, public health protection, and food safety, as VBNC cells evade conventional detection methods yet retain virulence potential and can resuscitate when conditions improve [11] [13].

The significance of the VBNC state extends beyond microbial ecology to direct clinical implications, particularly regarding antibiotic susceptibility profiles. Research has demonstrated that bacterial pathogens in the VBNC state exhibit markedly increased tolerance to antimicrobial treatments, including antibiotics to which their culturable counterparts remain susceptible [3] [12] [14]. This review systematically examines the environmental factors and clinical interventions that induce the VBNC state, compares the antibiotic susceptibility of VBNC cells versus their normal counterparts, and explores the molecular mechanisms underlying this altered phenotype, providing researchers with essential methodological frameworks for investigating this clinically relevant bacterial adaptation.

VBNC State Inducers and Experimental Conditions

Bacteria enter the VBNC state through diverse induction pathways, which can be broadly categorized into environmental stresses and clinical interventions. The table below summarizes key inducers, experimental parameters, and representative bacterial species documented to enter the VBNC state under these conditions.

Table 1: Key Inducers of the VBNC State and Experimental Conditions

| Inducer Category | Specific Inducer | Experimental Conditions | Representative Bacteria | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Stresses | Low Temperature | 4°C in artificial seawater or sterile water | Vibrio vulnificus, E. coli O157:H7 | [11] [12] |

| Nutrient Starvation | Dilute media or sterile water | E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae | [11] | |

| Osmotic Stress | 7% NaCl solution | Campylobacter jejuni | [15] | |

| Unfavorable pH | Acidic or alkaline conditions | Staphylococcus aureus | [11] | |

| Clinical/Disinfection Interventions | Chlorine | 10 mg/L free chlorine, 1 min exposure | Listeria monocytogenes | [13] |

| Sub-lethal Photocatalysis | TiO2 nanotubes, 365 nm LED lamp | Antibiotic-resistant E. coli | [16] | |

| UV Radiation | Varying doses and exposure times | E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [11] | |

| Antibiotics | Lethal doses of various antibiotic classes | Multiple species | [12] |

The induction of the VBNC state is not limited to a few species but has been documented in over 100 bacterial species to date, including significant human pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, Legionella pneumophila, Listeria monocytogenes, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis [11]. The timeline for induction varies significantly, from rapid induction (less than 48 hours for C. jejuni under osmotic stress) to more gradual transitions (days or weeks for starvation at low temperatures) [11] [15].

Antibiotic Susceptibility: VBNC vs Normal Cells

A critical aspect of the VBNC state with profound clinical implications is the dramatic alteration in bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobial agents. The table below compares the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of VBNC cells with their normal, culturable counterparts, highlighting the increased tolerance observed in the VBNC state.

Table 2: Antibiotic Susceptibility Profile Comparison Between Normal and VBNC Bacterial Cells

| Characteristic | Normal (Culturable) Cells | VBNC Cells | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Antibiotic Susceptibility | Susceptible to lethal doses | Highly tolerant to lethal doses | Biphasic killing curves; sustained viability post-treatment [12] |

| Underlying Mechanism | Genetic resistance (where present) | Phenotypic tolerance (non-heritable) | Non-genetic basis; reverts upon resuscitation [3] [12] |

| Metabolic Activity | Active metabolism and growth | Greatly reduced metabolic activity | Reduced translation, replication, and cell growth [3] [14] |

| Culturability Post-Exposure | Killed by effective antibiotics | Remain non-culturable but viable | Retain membrane integrity and viability [12] |

| Resuscitated Cells | N/A | Show higher antibiotic resistance than wild-type | Resuscitated E. coli showed increased antibiotic resistance [16] |

The antibiotic tolerance observed in VBNC cells is primarily attributed to their dormant state and dramatically reduced metabolic activity [3]. Since many antibiotics target active cellular processes such as cell wall synthesis, protein production, and DNA replication, the near-complete cessation of these processes in VBNC cells renders these antimicrobials ineffective [12] [14]. This tolerance is phenotypic and transient rather than resulting from genetic mutations, distinguishing it from conventional antibiotic resistance [12].

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The transition into and maintenance of the VBNC state is governed by sophisticated molecular mechanisms that regulate bacterial physiology in response to stress. The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathways and molecular events involved in VBNC state induction and the consequent antibiotic tolerance.

Diagram 1: Molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways in VBNC state induction and antibiotic tolerance. The diagram illustrates how environmental stresses and clinical interventions trigger specific molecular events leading to VBNC state entry and associated antibiotic tolerance.

The molecular events depicted in the diagram include several key processes:

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Accumulation: Multiple stresses induce oxidative damage, triggering defense responses that contribute to dormancy [16]. Repair of oxidative damage, coupled with changes in energy allocation centered around intracellular ATP levels, serves as a driving force for subsequent resuscitation [16].

Toxin-Antitoxin (TA) System Activation: Under stress conditions, unstable antitoxins are degraded, freeing toxins that inhibit essential cellular processes including translation, replication, and cell growth [3] [14]. These systems are genetically programmed modules that respond to environmental cues by dramatically slowing bacterial metabolism [14].

Metabolic Downregulation: The combined action of ROS accumulation and TA system activation leads to dramatic reduction in metabolic activity, which directly contributes to antibiotic tolerance by reducing the cellular targets of antimicrobial agents [3] [12].

The molecular control of the VBNC state shares significant overlap with mechanisms governing bacterial persistence, suggesting these phenomena exist on a continuum of bacterial dormancy rather than representing entirely distinct states [12] [14].

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Accurate detection and quantification of VBNC cells presents significant methodological challenges, as these cells cannot be cultured using conventional techniques. The table below summarizes key methodologies employed in VBNC research, along with their principles, experimental workflows, and applications.

Table 3: Methodologies for VBNC Cell Detection and Quantification

| Method Category | Specific Method | Principle | Experimental Protocol | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Staining | LIVE/DEAD BacLight | Membrane integrity detection using SYTO9/PI | Stain application, incubation, microscopy/flow cytometry | Differentiation of live/dead cells; can overestimate VBNC in complex matrices [11] [13] |

| Molecular Methods | PMA-qPCR | PMA dye penetrates dead cells; inhibits DNA amplification | PMA treatment (20 μM), photoactivation, DNA extraction, qPCR | Specific detection of viable cells; quantification of VBNC cells [13] [15] |

| Molecular Methods | EMA/PMAxx-qPCR | Combined dye approach for enhanced discrimination | EMA (10 μM) + PMAxx (75 μM), 40°C for 40 min, light activation | Improved VBNC detection in complex water matrices [13] |

| Advanced Molecular | ddPCR with PMA | Absolute quantification without standard curve | Oil-enveloped bacterial cells, PMA treatment, droplet digital PCR | Highly accurate VBNC quantification; Vibrio cholerae detection [17] |

| Functional Assays | DVC (Direct Viable Count) | Cell elongation in presence of antibiotics | Nalidixic acid + nutrients, incubation, microscopy | Detection of viable cells based on growth potential [11] |

The experimental workflow for investigating VBNC state induction and antibiotic susceptibility typically follows a logical sequence of steps, as illustrated in the diagram below.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for VBNC state induction and antibiotic susceptibility profiling. The diagram outlines the key phases in investigating VBNC cells, from initial induction through antibiotic exposure to resuscitation profiling.

Critical considerations for VBNC research methodologies include:

Method Validation: No single method perfectly detects VBNC cells in all contexts. Flow cytometry, for instance, while often recommended, may overestimate dead cells in complex matrices like process wash water [13].

Matrix Effects: The composition of the sample matrix significantly influences method performance. The combination of EMA and PMAxx dyes has shown particular effectiveness in complex water matrices with high organic matter content [13].

Culture-Based Confirmation: Despite their limitations, culture methods remain essential for confirming non-culturability and demonstrating resuscitation potential.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Research into the VBNC state requires specialized reagents and methodologies to accurately detect, quantify, and characterize these dormant cells. The table below outlines essential research reagents and their specific applications in VBNC studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for VBNC Cell Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Reagent | Function/Application | Example Usage | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Dyes | PMA (Propidium Monoazide) | Penetrates compromised membranes; inhibits DNA amplification from dead cells | PMA-qPCR for viable cell quantification (20 μM) | Requires photoactivation; concentration must be optimized [13] [15] |

| Viability Dyes | PMAxx | Enhanced version of PMA with improved dead cell DNA binding | Combined with EMA for complex matrices | More effective than PMA alone in certain applications [13] |

| Viability Dyes | EMA (Ethidium Monoazide) | DNA intercalating dye; penetrates via efflux pumps | EMA/PMAxx combination (10 μM EMA) | Can penetrate some viable cells; use with caution [13] |

| Viability Dyes | SYTO9/PI (LIVE/DEAD BacLight) | Dual staining for membrane integrity | Fluorescence microscopy/flow cytometry | Can overestimate VBNC in complex samples [11] [13] |

| Molecular Biology | qPCR Reagents | Detection and quantification of bacterial DNA | Species-specific gene amplification | Cannot differentiate viable/dead cells without viability dyes [15] |

| Molecular Biology | ddPCR Reagents | Absolute quantification without standard curves | VBNC cell enumeration with PMA | Higher accuracy than qPCR; no standard curve needed [17] |

| Induction Agents | TiO2 Nanotubes | Photocatalytic induction of VBNC state | Sub-lethal photocatalysis stress | Controlled induction for mechanistic studies [16] |

| Culture Media | Resuscitation Media | Nutrient-rich media for VBNC cell recovery | Testing resuscitation potential | Composition varies by bacterial species [11] |

The selection of appropriate reagents depends heavily on the specific research objectives and the bacterial species under investigation. For instance, PMA-qPCR has been successfully optimized for VBNC Campylobacter jejuni detection with a limit of detection of 2.43 log CFU/mL in pure culture and 3.12 log CFU/g in spiked chicken breasts [15]. Similarly, ddPCR with PMA treatment has shown enhanced sensitivity for absolute quantification of VBNC Vibrio cholerae cells without requiring DNA extraction [17].

The VBNC state represents a sophisticated bacterial survival strategy with far-reaching implications for clinical medicine, public health, and food safety. Through systematic investigation of VBNC inducers—from environmental stresses to clinical interventions—researchers have uncovered profound alterations in antibiotic susceptibility profiles that complicate treatment and eradication protocols. The experimental methodologies and research reagents detailed in this review provide essential tools for advancing our understanding of this complex phenomenon.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise molecular switches that control entry into and exit from the VBNC state, developing standardized detection methods applicable across diverse clinical and environmental samples, and identifying therapeutic approaches that either prevent VBNC state induction or effectively target dormant bacterial populations. As evidence accumulates regarding the increased antibiotic resistance of resuscitated VBNC cells [16] [18], addressing the challenge posed by this dormant state becomes increasingly urgent for effective antimicrobial stewardship and public health protection.

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state is a unique survival strategy adopted by many bacteria in response to adverse environmental conditions [19]. When bacteria enter this state, they lose the ability to form colonies on routine culture media—the standard method for detecting viability—while maintaining metabolic activity and cellular integrity [20]. This phenomenon has profound implications for public health, food safety, and clinical medicine, as VBNC pathogens cannot be detected by conventional methods but may retain virulence and resuscitate under favorable conditions [19] [20]. Within the context of antibiotic susceptibility research, understanding the fundamental hallmarks of VBNC cells is crucial, as these dormant cells exhibit dramatically increased tolerance to antimicrobial treatments compared to their normal, culturable counterparts [3] [4]. This guide systematically compares the morphological, physiological, and metabolic characteristics of VBNC cells against normal bacterial cells, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for investigating this elusive bacterial state.

Defining the VBNC State

The VBNC state represents a distinct survival state fundamentally different from both normal cellular activity and cell death. First described in 1982 for Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae [20], the VBNC condition is now recognized in numerous human bacterial pathogens [19] [21]. While VBNC cells are unable to proliferate on conventional media that typically support their growth, they maintain viability markers including membrane integrity, metabolic activity, gene expression, and the potential for resuscitation [20]. This state is typically induced by various environmental stresses such as nutrient starvation, temperature extremes, improper osmotic pressure, oxygen concentrations, and exposure to disinfectants or antibiotics [3] [20].

It is important to distinguish VBNC cells from other non-growing states. Unlike persister cells, which are also dormant and antibiotic-tolerant but represent a phenotypic variant within a growing population, VBNC cells encompass the entire population under specific conditions and exhibit a more comprehensive shutdown of growth functions [20]. Additionally, while dead cells have compromised membranes and no metabolic activity, VBNC cells maintain membrane integrity and continue limited metabolic functions [20]. The entry into the VBNC state is not a degenerative process but rather an adaptive strategy that enables long-term survival under unfavorable conditions, with the ability to resuscitate when conditions improve [19] [20].

Morphological and Structural Hallmarks

Cell Size and Shape Transformations

VBNC cells undergo significant morphological changes that distinguish them from their culturable counterparts. The most consistent alteration is a reduction in cell size, leading to an increased surface area to volume ratio, which is thought to minimize energy requirements for maintenance [20]. For example, Campylobacter jejuni transitions from its characteristic spiral shape in the exponential phase to a coccoid form in the VBNC state [20]. Similarly, Vibrio cholerae and Burkholderia pseudomallei change from rods during exponential growth to cocci in the VBNC state [20].

Quantitative analysis reveals substantial changes in cellular dimensions. Studies on Campylobacter jejuni demonstrated a notable increase in cell volume during the VBNC state, with average cell volumes measuring 1.73 μL/mg protein for culturable forms compared to 10.96 μL/mg protein after 30 days of incubation in microcosm water [21]. This dramatic size change represents a more than six-fold increase in volume, reflecting fundamental structural reorganization.

Table 1: Morphological Changes in VBNC Cells Compared to Normal Cells

| Bacterial Species | Normal Cell Morphology | VBNC Cell Morphology | Documented Size Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campylobacter jejuni | Spiral rods | Coccoid | Volume increase from 1.73 to 10.96 μL/mg protein [21] |

| Vibrio cholerae | Rod-shaped | Coccoid | Cell dwarfing commonly observed [20] |

| Escherichia coli | Rod-shaped | Smaller rods/spheres | No remarkable size change under chlorination [4] |

| Salmonella enterica | Rod-shaped | Spherical | Shape change from rod to sphere [22] |

Cell Wall and Membrane Modifications

The structural components of VBNC cells undergo significant modifications that contribute to their enhanced resilience. Changes in the outer membrane proteome have been documented in several species, with these alterations being highly dependent on the specific conditions used to induce the VBNC state [20]. In E. coli, differential expression of three outer membrane proteins (Omp)—antigen 43 β-subunit, TolC, and OmpT—was observed in cells exposed to nutrient-limited conditions, with the most dramatic changes (106 modulated proteins) occurring in cells exposed to natural seawater and light [20].

Fatty acid composition also undergoes marked changes during VBNC transition. Vibrio vulnificus shows significant increases in the percentage of unsaturated fatty acids and fatty acids with less than 16 carbons when entering the VBNC state, with notable changes in the percentages of hexadecanoic, hexadecenoic, and octadecanoic acids [20]. Additionally, enhanced peptidoglycan cross-linking has been observed in VBNC cells of Enterococcus faecalis, potentially contributing to increased resistance to environmental stresses [20].

These structural modifications have functional consequences. E. coli O157:H7 induced into the VBNC state by L-malic acid at low temperature showed maintained basic function of the cell membrane despite reduced cell size and respiratory activity [22]. Meanwhile, chlorination-induced VBNC E. coli displayed increased membrane permeability while maintaining cellular integrity [4].

Physiological and Metabolic Alterations

Metabolic Activity and Energy Conservation

VBNC cells exhibit a pronounced downshift in metabolic activity as a central survival strategy. While they maintain detectable metabolic functions, the overall metabolic rate is significantly reduced compared to normal cells [20]. This metabolic reconfiguration serves to conserve energy and enhance survival under adverse conditions. However, the degree of metabolic reduction varies depending on the inducing stressor, as demonstrated by studies using different detection methods. When assessed using 5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride combined with flow cytometry (CTC-FCM), the respiratory activity of UV-induced VBNC bacteria showed minimal variation unless exposed to very high UV doses (200 mJ/cm²) [23]. In contrast, when measured by D₂O-labeled Raman spectroscopy—which assesses overall metabolic activity through microbial deuterium incorporation—a clear dose-response relationship was observed, with higher UV doses resulting in progressively lower metabolic activity [23].

The adenylate energy charge (AEC), a key indicator of cellular energy status, undergoes dramatic changes in VBNC cells. In Campylobacter jejuni, the AEC drops significantly from normal levels to between 0.66 and 0.26 after just one day of incubation in microcosm water [21]. After 30 days, AMP becomes the only detectable nucleotide in these cells, indicating a severely compromised energy state [21]. This reduction in energy charge reflects the transition to a maintenance-only metabolic mode.

Table 2: Metabolic and Physiological Parameters in VBNC vs Normal Cells

| Parameter | Normal Cells | VBNC Cells | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenylate Energy Charge | High (typically >0.8) | Low (0.66-0.26) to only AMP detectable [21] | HPLC measurement of ATP, ADP, AMP |

| Respiratory Activity | High | Reduced but detectable [23] [22] | CTC-FCM |

| Overall Metabolic Activity | High | Significantly reduced, heterogeneous [23] | D₂O-labeled Raman Spectroscopy |

| Membrane Potential | High | Significantly lower [21] | Fluorometric assays |

| Internal pH Maintenance | Normal (0.6-0.9 pH unit difference) | Progressive decrease [21] | Internal pH probes |

Gene Expression and Protein Synthesis

VBNC cells undergo comprehensive reprogramming of gene expression that underlies their physiological adaptations. Transcriptomic analyses reveal significant alterations in expression patterns across multiple functional categories. In Vibrio cholerae, 58 genes related to regulatory functions, cellular processes, energy metabolism, transport, and binding were induced by more than 5-fold in the VBNC state [20]. Conversely, another study reported reduced expression of 16S rRNA and mRNA levels of tuf, rpoS, and relA genes, which are responsible for protein synthesis and stress responses [20].

The expression of specific outer membrane proteins shows marked changes during VBNC transition. In E. coli, ompW expression is significantly induced in VBNC cells [20]. This protein may play a role in stress adaptation, though its exact function in the VBNC state requires further elucidation. Additionally, ribosomal activity is substantially reduced in VBNC cells, with decreased expression levels of ribosome-associated proteins including ribosomal-associated inhibitor (RaiA), 40S ribosomal subunit (S6), and bacterioferritin comigratory protein (Bcp) compared to normal cells [19].

Proteomic profiles of VBNC cells reflect their metabolic reorientation. Food isolates of E. coli O157 in the VBNC state showed decreased levels of oxidation-responsive factors (AhpCF and AceF) but exhibited a distinct increase in outer-membrane protein W (OmpW) levels [19]. Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the VBNC state up-regulates proteins associated with transcription, translation, ATP synthase, gluconeogenesis-related metabolism, and antioxidants [19]. This selective preservation of certain metabolic pathways while downregulating others appears to be a conserved feature of the VBNC state.

Homeostasis and Membrane Functions

The maintenance of cellular homeostasis is fundamentally altered in VBNC cells. Ion gradient maintenance is significantly compromised, with VBNC cells of Campylobacter jejuni showing substantially reduced internal potassium content compared to culturable forms [21]. The membrane potential is also significantly lower in the VBNC state, further indicating disruption of normal energy-transducing functions [21].

The ability to regulate internal pH is markedly impaired in VBNC cells. While culturable Campylobacter jejuni cells maintain a difference of 0.6 to 0.9 pH units between internal and external pH values, this difference decreases progressively with incubation time in microcosm water in VBNC cells [21]. This failure of pH homeostasis reflects the compromised energy status and reduced membrane function in VBNC cells.

Despite these alterations, VBNC cells maintain membrane integrity, which distinguishes them from dead cells. Studies using viability stains based on membrane integrity, such as the LIVE/DEAD BacLight assay, confirm that VBNC cells maintain an intact membrane that excludes certain dyes [20] [4]. However, increased membrane permeability has been documented in some VBNC cells induced by specific stressors, such as chlorination in E. coli [4].

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Detection and Enumeration Techniques

Accurate detection of VBNC cells requires specialized methodologies that bypass the limitations of conventional culture-based approaches. The most widely used techniques combine viability indicators with direct microscopic or flow cytometric enumeration.

The CTC-DAPI staining method allows simultaneous assessment of respiratory activity and total cell count. In this protocol, 5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride (CTC) is used as an indicator of respiratory activity—respiring cells reduce CTC to insoluble, fluorescent formazan crystals [21]. DAPI (4',6-diamino-2-phenylindole) stains all cells fluorescent blue by binding to DNA [21]. The specific protocol involves:

- Incubating samples with CTC (final concentration 2-5 mM) for 60-90 minutes at appropriate temperature

- Fixing with neutral-buffered formalin (final concentration 2%) for 15 minutes

- Staining with DAPI (final concentration 1-5 μg/mL) for 5-10 minutes

- Filtering through black polycarbonate membranes (0.2 μm pore size)

- Enumeration using epifluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry [21]

D₂O-labeled Raman spectroscopy provides an alternative approach for assessing metabolic activity at both population and single-cell levels. The experimental workflow consists of:

- Incubating bacterial cells in deuterium oxide (D₂O)-supplemented medium (typically 20-30% D₂O)

- Allowing incorporation of deuterium into newly synthesized biomolecules for 6-24 hours

- Fixing cells with paraformaldehyde (2-4%) for stability

- depositing cells on aluminum-coated slides for analysis

- Measuring Raman spectra with a confocal Raman microscope

- Calculating the CD/(CD+CH) ratio from the C-D (2040-2300 cm⁻¹) and C-H (2800-3100 cm⁻¹) bands as an index of metabolic activity [23]

Standardized protocols for inducing and resuscitating VBNC states are essential for experimental reproducibility across studies.

Microcosm water induction provides a controlled environment for VBNC formation:

- Grow bacterial cultures to late exponential or stationary phase

- Harvest cells by gentle centrifugation (3000 × g, 10 minutes)

- Wash twice in sterile water or saline to remove residual nutrients

- Resuspend in filter-sterilized (0.2 μm pore size) natural water or simulated oligotrophic medium at pH 6.0-7.0

- Incubate at induction temperature (typically 4°C for mesophilic pathogens) with gentle shaking (100 rpm)

- Monitor culturability by plate counts and viability by direct methods over 15-30 days [21]

Chemical induction methods include:

- Chlorine induction: Expose cells to 0.5 mg/L chlorine for 6 hours at room temperature [4]

- L-malic acid induction: Treat cells with 0.12-0.25 mM L-malic acid at 4°C for extended periods [22]

- Sub-lethal photocatalysis: Expose cell suspensions to TiO₂ nanotubes illuminated with 365 nm LED lamp (100 mW/cm²) for 1-10 hours [16]

Resuscitation protocols typically involve:

- Transferring VBNC cells to nutrient-rich media such as Brain Heart Infusion or LB broth

- Incubating at optimal growth temperatures

- Monitoring culturability restoration over 24-48 hours [16] [4]

- For challenging strains, adding resuscitation-promoting factors (Rpfs) or using host systems like embryonated eggs [19] [20]

Diagram 1: VBNC State Transitions and Assessment Methods. This workflow illustrates the induction of the VBNC state by environmental stressors, the key methods for detection, and the potential for resuscitation under favorable conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VBNC Cell Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Stains | CTC, DAPI, SYTO 9, PI | Differentiate viable cells based on membrane integrity and metabolic activity | Direct viable counts, respiratory activity assessment [21] [23] |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | PCR/qPCR reagents, RNA-seq kits | Detect gene expression and virulence genes in VBNC cells | Transcriptomic analysis, virulence gene detection [19] [4] |

| Metabolic Labels | Deuterium oxide (D₂O) | Track metabolic activity through deuterium incorporation | Raman spectroscopy metabolic assessment [23] |

| Induction Media | Microcosm water, oligotrophic buffers | Simulate natural stressful conditions for VBNC induction | Controlled VBNC state formation [21] [22] |

| Resuscitation Promoters | Rpf proteins, nutrient broths, host cell systems | Reactivate VBNC cells to culturable state | Resuscitation studies, virulence assessment [19] [16] |

| Antibiotics | Ampicillin, ofloxacin, other antimicrobials | Assess antibiotic tolerance of VBNC cells | Antibiotic susceptibility testing [3] [4] |

Implications for Antimicrobial Susceptibility

The morphological, physiological, and metabolic shifts in VBNC cells have profound implications for their antibiotic susceptibility profiles. VBNC cells exhibit dramatically increased tolerance to a wide range of antimicrobial agents compared to their normal, culturable counterparts [3]. This enhanced tolerance presents significant challenges for clinical treatment and public health interventions.

The mechanisms underlying this tolerance are multifaceted. The greatly reduced metabolic activity and downregulated cellular processes in VBNC cells decrease the efficacy of many antibiotics that target active cellular functions [3]. Additionally, structural changes such as increased peptidoglycan cross-linking and membrane modifications may reduce permeability to antimicrobial agents [20]. Research has demonstrated that E. coli in the VBNC state can persist in the presence of extremely high antibiotic concentrations—up to 200 μg/mL ampicillin and 5 μg/mL ofloxacin (approximately 128× and 64× the MIC, respectively) [4]. Similarly, Vibrio vulnificus in the VBNC state exhibits enhanced tolerance to heat, oxidative stress, osmotic stress, pH fluctuations, ethanol, antibiotics, and heavy metals [20].

This antibiotic tolerance has direct clinical relevance. After resuscitating from the VBNC state, E. coli cells showed higher antibiotic resistance than wild-type cells [16]. The persistence of VBNC pathogens in clinical settings may contribute to recurrent infections and treatment failures, particularly in biofilm-associated infections where dormant cells are protected from antimicrobial therapies [24]. Understanding the unique hallmarks of VBNC cells is therefore essential for developing strategies to combat these persistent bacterial populations.

The viable but nonculturable (VBNC) state is a dormant survival strategy adopted by numerous bacterial species when confronted with environmental stress [25]. Cells in this state are characterized by a loss of culturability on routine laboratory media, while maintaining metabolic activity and pathogenic potential [12] [20]. The resuscitation of these dormant cells back to an active, culturable state represents a significant public health threat, contributing to recurrent infections, foodborne illness outbreaks, and antimicrobial treatment failures [26] [25]. This phenomenon is of particular concern within the context of antibiotic resistance, as research indicates that resuscitated VBNC cells can exhibit enhanced antibiotic resistance compared to their pre-dormant counterparts [16] [18]. Understanding the mechanisms governing this transition is therefore critical for developing novel therapeutic strategies to control persistent and chronic infections. This guide objectively compares the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of VBNC and normal cells, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies from current research.

VBNC State vs. Antibiotic Persistence: A Critical Distinction

While both the VBNC state and antibiotic persistence represent dormant, stress-tolerant phenotypes, they are distinct physiological states. It is essential to differentiate them, particularly in experimental design and data interpretation.

Table: Distinguishing VBNC Cells from Antibiotic Persisters

| Characteristic | VBNC State | Antibiotic Persisters |

|---|---|---|

| Culturability | Complete loss on standard media [25] | Retained, population exhibits biphasic killing [12] |

| Induction Stress | Wider range of moderate, long-term stresses (starvation, temperature, disinfection) [25] | Often specific stresses, notably antibiotics [12] |

| Metabolic Activity | Low but measurable [25] [20] | Low, can be below detection limit [12] |

| Resuscitation Trigger | Requires specific stimuli (e.g., nutrient addition, stress removal, Rpf) [26] [25] | Often resumes growth upon antibiotic removal [12] |

| Population Dynamics | Entire population becomes nonculturable [16] | A small, tolerant subpopulation within a larger susceptible one [12] |

The relationship between these states is sometimes described as a dormancy continuum, where active cells may first transition into persisters, which can then enter the deeper dormancy of the VBNC state under prolonged stress [12] [27].

Quantitative Comparison of Antibiotic Susceptibility

Experimental data consistently demonstrates that VBNC cells possess a significantly higher tolerance to antibiotics and other chemical stresses compared to their culturable, normal-state cells. The following table synthesizes key findings from recent studies.

Table: Experimental Comparison of Stress Resistance in VBNC vs. Normal Cells

| Bacterial Species | Inducing Stress | Key Experimental Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (ARB & ASB) | Sub-lethal photocatalysis | Resuscitated cells showed higher antibiotic resistance than wild-type cells. | [16] [18] |

| Vibrio vulnificus | Multiple | VBNC cells exhibited higher resistance to heat, low pH, ethanol, antibiotics, heavy metals, and oxidative/osmotic stress than exponential-phase cells. | [20] |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Starvation/Oligotrophy | VBNC cells showed increased tolerance to antibiotics including ampicillin and vancomycin. | [20] |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Not Specified | VBNC cells demonstrated greater tolerance to chlorine and antibiotics. | [20] |

| E. coli O157:H7 | Copper | VBNC state induced by copper could be reversed by chelating agents, demonstrating tolerance during dormancy. | [26] |

The intrinsic tolerance of VBNC cells is attributed to their drastically reduced metabolic activity, which renders many bactericidal antibiotics that target active cellular processes ineffective [12] [20]. Furthermore, structural changes like increased peptidoglycan cross-linking can enhance physical robustness [20].

To provide a reproducible methodology for researchers, the following workflow details a protocol adapted from a key study on antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) [16] [18].

Key Experimental Steps and Notes

- Bacterial Strains and VBNC Induction: The protocol utilizes both antibiotic-resistant (ARB) and antibiotic-susceptible bacteria (ASB) E. coli strains. VBNC state is induced via sub-lethal photocatalysis using a TiO₂ nanotube system under LED light (365 nm) for 1-10 hours. The "sub-lethal" condition is critical, as it causes damage without immediate cell death, triggering the dormancy response [16].

- Confirmation of VBNC State: A definitive confirmation requires demonstrating zero culturable cells (CFU/mL = 0) on agar plates that normally support growth, coupled with positive signals from viability assays (e.g., LIVE/DEAD staining showing membrane integrity) [25]. A decrease in cell length is a common morphological indicator [16] [20].

- Resuscitation and Analysis: Resuscitation is initiated by removing the inductive stress, typically by transferring cells to a nutrient-rich medium like LB broth, and incubating at an optimal growth temperature (e.g., 37°C for E. coli) for 5-20 days. The recovery of culturability is monitored by plate counts. Analysis of resuscitated cells should include antibiotic resistance profiling to compare with pre-dormancy levels, often showing increased resistance [16] [18]. Molecular techniques like qPCR can be used to assess the repair of oxidative damage, a key driver of resuscitation [16].

The resuscitation of VBNC cells is not a simple reversal of the entry process but an active biological event driven by specific molecular pathways. The current research highlights several key mechanisms.

The primary drivers for resuscitation include the repair of oxidative damage and changes in energy allocation, with intracellular ATP and metabolic activity being the major force [16] [26]. This process requires de novo synthesis of proteins and cell wall components, as inhibitors like chloramphenicol and penicillin can block resuscitation [26]. In some species, specific signaling molecules like Resuscitation Promoting Factors (Rpfs) or autoinducers are involved, suggesting a regulated process [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues key reagents and their applications for studying the VBNC state and resuscitation.

Table: Essential Reagents for VBNC State Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|

| TiO₂ Nanotubes | A catalyst for inducing VBNC state via sub-lethal photocatalysis. | Used with LED light to generate oxidative stress, inducing VBNC state in E. coli [16]. |

| LIVE/DEAD Staining Kits (e.g., with SYBR Green/PI) | Differentiating viable cells (with intact membranes) from dead cells. | Confirming viability of nonculturable cells during VBNC state confirmation [25] [20]. |

| ATP Assay Kits | Quantifying intracellular ATP levels as a direct measure of metabolic activity. | Demonstrating that VBNC cells maintain high ATP levels, a key criterion and driver for resuscitation [16] [20]. |

| Resuscitation Promoting Factors (Rpfs) | Bacterial cytokine-like proteins that stimulate resuscitation from dormancy. | Added to resuscitation medium to promote the recovery of VBNC cells in certain species [26]. |

| Sodium Pyruvate / Catalase | Peroxidase supplements that degrade residual hydrogen peroxide in media. | Used to exclude the possibility that regrowth is from H₂O₂-sensitive culturable cells, thereby confirming true resuscitation [26]. |

| Specific Antibiotics (e.g., Ampicillin) | Selective agents to inhibit the growth of any remaining culturable cells. | Added to resuscitation medium to ensure that observed growth originates from VBNC cells, not a few residual culturable cells [26]. |

| qPCR Reagents | Quantifying gene expression changes during induction and resuscitation. | Analyzing expression of genes related to oxidative damage repair, stress response, and virulence [16] [18]. |

The phenomenon of bacterial resuscitation from the VBNC state presents a formidable challenge in clinical and environmental microbiology. The experimental data clearly demonstrates that this is not a regrowth artifact but a genuine return from a deep state of dormancy, often resulting in cells with enhanced resistance traits [16] [18]. The molecular mechanisms, while not fully elucidated, involve active repair processes and metabolic rewiring [16] [26]. For researchers and drug development professionals, acknowledging this survival strategy is paramount. Future therapeutic development must move beyond targeting actively growing cells and consider strategies to either prevent entry into the VBNC state, permanently eradicate dormant cells, or interfere with the resuscitation machinery itself. Standardized methodologies, as outlined in this guide, are essential for generating reproducible and comparable data to advance our understanding and overcome this hidden reservoir of bacterial persistence and antibiotic resistance.

Beyond Plate Counts: Advanced Methodologies for VBNC Cell Detection and Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiling

Standard antimicrobial efficacy testing, reliant on culture-based methods, operates with a significant blind spot: the inability to detect bacteria in the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state. This dormant survival strategy is induced by various environmental stresses, including sub-lethal antibiotic exposure, disinfectants, and food processing conditions. VBNC cells maintain metabolic activity and virulence potential while losing cultivability on routine media, leading to a critical underestimation of microbial risk and therapeutic failure. This guide compares the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of VBNC cells to their normal, culturable counterparts, synthesizing experimental data to highlight the limitations of conventional testing and the advanced methodologies required to evaluate the true efficacy of antimicrobial interventions.

The VBNC State: A Survival Strategy Beyond Culturability

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state is a survival mechanism employed by numerous bacterial species in response to adverse environmental conditions. Cells in this state are defined by their loss of cultivability on media that normally support their growth, while maintaining viability, metabolic activity, and the potential to resuscitate when conditions become favorable [25]. This state can be induced by a wide array of stresses common in clinical, industrial, and natural environments, including nutrient starvation, temperature shifts, osmotic challenges, and exposure to sub-lethal concentrations of biocides and antibiotics [12] [25].

Critically, the VBNC state is fundamentally different from bacterial persistence. While both represent non-growing phenotypes, persister cells remain culturable and their phenotype is typically reversible upon removal of the antibiotic. In contrast, VBNC cells are non-culturable and require specific resuscitation signals to return to a growth-capable state [12] [25]. The formation of VBNC cells is now recognized as a nearly universal strategy across bacterial species, posing a significant challenge to public health by contributing to recurrent infections and the undetected spread of antibiotic resistance [12].

Comparative Susceptibility: VBNC vs. Normal Cells

The following tables summarize experimental data from key studies, demonstrating the markedly increased tolerance of VBNC cells to antimicrobials compared to their culturable counterparts.

Table 1: Antibiotic Tolerance of VBNC E. coli Induced by Different Stressors

| Inducing Stressor | Antibiotic Challenge | Response of Culturable (Normal) Cells | Response of VBNC Cells | Experimental Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Level Chlorination (0.5 mg/L) | Ampicillin (200 µg/mL); Ofloxacin (5 µg/mL) | Susceptible (Standard MIC) | High tolerance to ~128x and ~64x MIC, respectively | [4] |

| Sub-Lethal Photocatalysis | Not Specified | Susceptible (Standard MIC) | Resuscitated cells showed higher antibiotic resistance than wild-type | [28] |

| General VBNC State Induction | Various Antibiotics | Susceptible (Standard MIC) | Exhibit drastically increased tolerance and persistence | [3] [12] |

Table 2: Antimicrobial Tolerance of VBNC Pathogens Beyond E. coli

| Bacterial Species | VBNC Inducing Condition | Antimicrobial Challenge | Key Finding on VBNC Tolerance | Experimental Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vibrio vulnificus | Starvation, Cold | Heat, Oxidative Stress, Osmotic Stress, Antibiotics, Heavy Metals | Protected against a variety of potentially lethal environmental challenges | [4] |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Acid, Cold, Osmotic (Poultry Processing) | Carvacrol, Diallyl Sulfide, Al₂O₃ Nanoparticles | High level of persistence to plant-based antimicrobials; only high conc. of Al₂O₃ NPs achieved >1 log reduction | [29] |

| Various (E. coli, E. faecalis, V. vulnificus) | Multiple | Various Antibiotics | Greater resistance to antibiotics compared to culturable counterparts | [29] |

Methodologies for Investigating VBNC Susceptibility

Conventional antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) relies on culture-based methods like broth microdilution and disk diffusion, which measure growth inhibition. These methods are intrinsically incapable of detecting VBNC cells, leading to a complete oversight of this resistant subpopulation [3]. Researchers must therefore employ a combination of viability markers and molecular techniques to assess the antimicrobial effects on VBNC states.

Key Experimental Protocols

1. Induction of the VBNC State:

- Stressor Application: Expose a mid-logarithmic phase bacterial culture to a sub-lethal stressor. Common inducers include:

- Monitoring Induction: Monitor the culture daily using plate counts. The VBNC state is considered induced when the colony-forming unit (CFU) count drops to zero on appropriate solid media, while viability is confirmed via methods below [25].

2. Viability Staining and Flow Cytometry:

- Procedure: Stain the bacterial suspension with fluorescent dyes. A common combination is SYTO 9 (green, stains all cells) and propidium iodide (PI) (red, penetrates only cells with damaged membranes).

- Analysis: Analyze using flow cytometry. VBNC cells are characterized as SYTO 9 positive / PI negative, indicating an intact membrane and viability despite non-culturability [4] [13]. This method can be hampered by complex matrices like process wash water, which may cause overestimation of dead cells [13].

3. Viability Quantitative PCR (v-qPCR):

- Principle: This method uses photoreactive dyes like propidium monoazide (PMAxx) or ethidium monoazide (EMA) that penetrate membrane-compromised (dead) cells and bind covalently to DNA, inhibiting its amplification in PCR.

- Protocol:

- Treat the sample with a optimized combination of dyes (e.g., 10 µM EMA and 75 µM PMAxx).

- Incubate in the dark (e.g., 40°C for 40 min).

- Expose to a high-intensity light source for 15 minutes to photo-activate the dyes.

- Extract DNA and perform qPCR.

- Output: The quantified DNA originates only from cells with intact membranes (viable and VBNC cells), allowing their distinction from free DNA and dead cells [13]. This method has been successfully validated in industrial settings.

4. Time-Kill Assay for VBNC Cells:

- Procedure: This is a key method for evaluating the activity of antimicrobials against non-growing VBNC cells [29].

- Expose a confirmed VBNC population to the antimicrobial agent over a set time.

- At intervals, sample and neutralize the antimicrobial.

- Use v-qPCR or flow cytometry (not plate counts) to quantify the remaining viable cell count.

- Analysis: Plot the log reduction of viable cells over time to determine the bactericidal activity of the antimicrobial against the VBNC population [29].

Visualizing the VBNC Investigation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for inducing, confirming, and challenging the VBNC state, highlighting the parallel tracks of conventional and VBNC-aware methodologies.

Diagram 1: Workflow for VBNC State Investigation and Antimicrobial Challenge.

Molecular Mechanisms of VBNC Tolerance

The elevated antimicrobial tolerance of VBNC cells is not primarily due to acquired genetic resistance mutations. Instead, it is a consequence of their dormant physiology and specific molecular adaptations.

- Reduced Metabolic Activity: The dramatic downshift in metabolic processes and cell division means that VBNC cells are not actively engaging with many cellular targets of antibiotics (e.g., cell wall synthesis, protein synthesis) [3] [12].

- Cellular Damage Repair: Resuscitation from the VBNC state is driven by the repair of stress-induced damage, such as oxidative lesions. Intracellular ATP levels and metabolic activity are critical forces powering this resuscitation, highlighting a key survival mechanism [28].

- Transcriptional Reprogramming: Transcriptomic analyses reveal that VBNC cells undergo significant gene expression changes. This includes upregulation of genes related to stress responses, transcriptional regulation, and antibiotic resistance, which collectively render the cells more tolerant to adverse conditions [4].

- Toxin-Antitoxin Systems: Type II toxin-antitoxin (TAS) systems are genetic modules that contribute to dormancy. Under stress, unstable antitoxins are degraded, allowing stable toxins to inhibit essential cellular processes like translation and replication, thereby inducing a dormant, highly tolerant state [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Equipment for VBNC and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in VBNC Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| PMAxx / EMA Dyes | Viability dyes for v-qPCR; selectively inhibit DNA amplification from dead cells. | Differentiation between viable (VBNC) and dead cells in a sample [13]. |

| SYTO 9 / Propidium Iodide (PI) | Fluorescent nucleic acid stains for cell viability analysis via microscopy/flow cytometry. | Determining membrane integrity; VBNC cells are SYTO 9+/PI- [4]. |

| Chlorine (Sodium Hypochlorite) | Chemical stressor for inducing the VBNC state at low concentrations (e.g., 0.5 mg/L). | Mimicking disinfection conditions in water distribution systems [4]. |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) System | For quantifying gene expression and viable cell load via v-qPCR. | Quantifying total and viable bacterial populations and expressing virulence/antibiotic resistance genes [28] [4]. |

| Flow Cytometer | Multiparameter analysis of cell physiology and viability at the single-cell level. | Rapid quantification of subpopulations (culturable, VBNC, dead) based on staining [13]. |

| TiO2 Nanotubes & LED Lamp | System for applying sub-lethal photocatalytic stress. | Inducing VBNC state via oxidative stress in a controlled manner [28]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | High-resolution imaging of cell morphology and surface damage. | Observing physical changes and membrane damage in VBNC cells [28] [4]. |

The evidence is clear: standard, culture-based antimicrobial efficacy testing provides an incomplete and often misleading picture by failing to account for the VBNC state. This blind spot has profound implications, from the overestimation of disinfection efficacy in water and food processing to the misunderstanding of chronic and recurrent infections in clinical settings. The elevated and multi-faceted tolerance of VBNC cells to antimicrobials underscores the necessity for the scientific community to adopt more sophisticated, culture-independent tools. Integrating viability-PCR, flow cytometry, and transcriptomic analyses into routine assessment protocols is no longer a niche pursuit but a critical step towards accurately evaluating antimicrobial interventions and developing strategies to counter this resilient survival mechanism.

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state represents a dormant, low-metabolic condition that numerous bacterial pathogens adopt to survive environmental stresses, including sublethal antibiotic exposure. Cells in the VBNC state maintain membrane integrity and metabolic activity but fail to grow on conventional culture media, the gold standard for viability assessment in clinical microbiology [30] [31]. This creates a critical blind spot in therapeutic development, as standard antibiotic susceptibility tests that rely on culturability may falsely classify dormant VBNC populations as susceptible, overlooking a significant reservoir of persistent bacteria with potential resuscitation capacity. Research indicates that VBNC cells can retain virulence and resuscitate under favorable conditions, posing a substantial risk for recurrent infections and treatment failure [32] [31]. Consequently, methodologies capable of detecting and quantifying these elusive populations are essential for advancing our understanding of true antibiotic efficacy and developing strategies to eradicate persistent bacterial reservoirs.

Flow cytometry combined with viability staining has emerged as a powerful tool to dissect bacterial heterogeneity at the single-cell level, simultaneously discriminating live, dead, and VBNC populations within a sample. This guide compares the performance of key staining approaches and flow cytometric methods against traditional techniques, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to integrate these powerful tools into antimicrobial susceptibility research.

Comparative Analysis of Viability Assessment Methods

Performance Metrics of Key Technologies

The following table summarizes the core principles, advantages, and limitations of the primary methods used for bacterial viability assessment, highlighting their distinct capabilities regarding VBNC detection.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Differentiating Live, Dead, and VBNC Bacterial Cells

| Method | Principle | Detects VBNC? | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plate Culture (CFU) [30] | Bacterial proliferation on solid media | No | Regulatory gold standard; simple; provides isolates for further study | Time-consuming (1-7 days); misses VBNC cells |

| Live/Dead Staining + Flow Cytometry [33] [31] | Membrane integrity using nucleic acid dyes (e.g., SYTO9/PI) | Yes | Rapid (<1 hour); high-throughput; single-cell data; distinguishes viable (including VBNC) from dead | Cannot assess culturability directly; requires specialized instrument |

| Viability PCR (v-PCR) [34] [32] | Dyes (PMA/EMA) penetrate compromised membranes and inhibit DNA amplification | Yes | Specific detection of viable cells (with intact membranes); fast; sensitive | Complex sample matrix can interfere; may not detect all VBNC cells |

| Metabolic Activity Assays [30] | Uptake and enzymatic conversion of fluorogenic substrates (e.g., FDA, CFDA) | Yes | Measures metabolic activity, a key viability marker | Signal can be low in dormant VBNC cells; sensitive to pH |

| Flow Cytometry-Cell Sorting + qPCR [32] | Cell sorting based on viability staining followed by species-specific qPCR | Yes | Quantifies specific VBNC pathogens in complex samples | Technically complex and expensive; multi-step protocol |

Quantitative Data: Flow Cytometry vs. Culture-Based Enumeration

Discrepancies between flow cytometry and plate counts provide direct evidence of the VBNC population. The following table compiles experimental data from recent studies highlighting the superior detection capability of flow cytometry.

Table 2: Experimental Recovery of Viable Bacteria: Flow Cytometry (FC) vs. Plate Count (PC)

| Bacterial Species / Sample Type | Treatment / Condition | Viable Count (FC) | Culturable Count (PC) | Inferred VBNC Population | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Listeria monocytogenes (Process Wash Water) | Chlorine (10 mg/L) | Maintained at ~105 AFU/ml* | Reduced to 0 CFU/ml | ~105 cells/ml | [34] |

| Multi-species Probiotic Blends | Various storage stresses | 101.8% of input viable cells recovered | 81.4% of input viable cells recovered | 20.4% of total population | [33] |

| Escherichia coli (Plasma-Activated Water) | Plasma exposure | <1 log reduction | ~7 log reduction | Significant proportion entered VBNC | [35] |

| Legionella pneumophila (Water Systems) | Environmental stress & disinfection | Detectable via FCM-qPCR | Not detectable by culture | Present and potentially infectious | [32] |

*AFU: Active Fluorescent Units, a viability metric from flow cytometry.

Core Staining Mechanisms and Experimental Protocols

Mechanism of Dual Staining for Flow Cytometry

The most common approach for viability assessment uses a combination of membrane-permeant and membrane-impermeant fluorescent nucleic acid stains. The workflow and decision process for this method is outlined below.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and their functions for performing viability staining and flow cytometry.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Viability Staining and Flow Cytometry

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Features | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live/Dead BacLight Kit [35] [31] | Differential staining based on membrane integrity | Contains SYTO9 and PI; works for a broad spectrum of bacteria | Enumeration of VBNC Listeria monocytogenes after chlorine treatment [31] |

| Fixable Viability Dyes (FVD) [36] | Covalently labels dead cells with compromised membranes | Dyes are cross-linked to proteins; compatible with fixation/permeabilization | Complex protocols involving intracellular staining or sample archiving |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) [36] [33] | Impermeant stain to identify dead cells | Red fluorescence; must be present in buffer during acquisition | Standard live/dead staining in combination with a green permeant dye like SYTO24 [33] |

| PMA/EMA Dyes [34] [32] | Selective DNA labeling for viability PCR (v-PCR) | Penetrate dead cells; bind DNA upon photoactivation to inhibit PCR | Detecting VBNC Legionella in complex water samples when combined with qPCR [32] |

| SYTO 9 / SYTO 24 Dyes [33] [31] | Permeant stain to label all cells | Green fluorescence; can be displaced by PI in dead cells | Standard live/dead staining in combination with PI [33] [31] |

Standard Protocol: Viability Staining for Flow Cytometry

This protocol is adapted from the ISO 19344|IDF 232 standard for microbial enumeration and is suitable for most bacteria [33].

Materials:

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), azide- and protein-free

- Flow cytometry staining buffer

- Fluorescent dyes: SYTO 24 (or SYTO 9) and Propidium Iodide (PI)

- Flow cytometer with a 488 nm blue laser

Experimental Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a single-cell suspension and wash cells twice in azide-free PBS.

- Cell Concentration: Resuspend the cell pellet at a concentration of 1–5 × 10^7 cells/mL in PBS or maximum recovery diluent.

- Staining: Add 100 μL of cell suspension to a mixture of 880 μL diluent and 10 μL of each fluorescent dye (e.g., 0.1 mM SYTO 24 and 0.2 mM PI).

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture for 15 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis: Vortex the sample and analyze immediately on the flow cytometer. Use the following settings as a starting point:

- Fluidics: Medium flow rate (∼35 μL/min)

- Threshold: Set on Forward Scatter (FSC-H > 2500) and Green Fluorescence (SYTO24-H > 1000) to exclude background noise.

- Detection: Collect green fluorescence (FL-1 detector, ~530 nm) for SYTO 24 and red fluorescence (FL-3 detector, >670 nm) for PI.

Data Interpretation:

- Viable cells (AFUs): Green fluorescence only (SYTO 24 positive).

- Non-viable cells (n-AFUs): Red fluorescence (PI positive). Note that cells stained with both dyes are also considered non-viable.

- VBNC Population Calculation: The VBNC population is inferred by subtracting the culturable count (CFU/mL) from the viable count obtained by flow cytometry (AFU/mL) [33].

Advanced Applications and Integrated Workflows

Flow Cytometry-Cell Sorting and qPCR for Specific VBNC Pathogen Detection

For complex samples like water or sputum, a combination of flow cytometry and molecular methods is required to quantify specific VBNC pathogens. The "Viability-based Flow Cytometry-Cell Sorting and qPCR" (VFC+qPCR) assay is a powerful solution [32].

Workflow:

- Viability Staining & Sorting: Environmental samples are stained with a viability dye (e.g., SYTO9). The flow cytometer is then used to sort the viable (green fluorescent) cell population.

- DNA Extraction and qPCR: DNA is extracted from the sorted viable cells and subjected to a species-specific qPCR assay (e.g., targeting Legionella pneumophila).

- Quantification: The genomic load of the viable, non-culturable pathogen is quantified from the standard qPCR curve.

Significance: This method confirmed that standard culture pre-treatment procedures (acid/heat shock) can themselves induce a VBNC state in a portion of the population, leading to significant underestimation of the risk posed by pathogens like Legionella [32].

Investigating Antibiotic Susceptibility in VBNC Cells

Integrating viability staining with antibiotic exposure studies allows researchers to track the population dynamics of live, dead, and VBNC cells in response to therapeutic agents.

Experimental Framework:

- Expose bacterial cultures to a range of antibiotic concentrations and contact times.

- At various time points, aliquot samples for parallel analysis:

- Flow Cytometry: Analyze with viability stains to determine the proportion of live, VBNC, and dead cells.

- Plate Counting: Determine the culturable fraction.

- Correlate the data to identify antibiotic concentrations that eliminate culturability but leave a persistent VBNC population.

- Further investigate the VBNC population sorted by flow cytometry for their potential to resuscitate and for transcriptomic or proteomic profiles that underpin their tolerance.

This integrated approach moves beyond the simple "susceptible" or "resistant" dichotomy and is crucial for understanding the role of VBNC cells in chronic and recurrent infections, ultimately guiding the development of more effective anti-persister therapies.